Daniel M. Bensen's Blog, page 55

December 18, 2017

Beta-readers for The Sultan’s Enchanter?

Friends, arkadashli, and arkadaşlar! My historical fantasy-romance-alternate-history is done…again!

Three years ago, my agent told me to rewrite the first three chapters and send it back to her. Three years later, I have somewhat done so! If you’ve read earlier versions of The Sultan’s Enchanter (under its old name “Charming Lies”), you might recognize a lot. But I think I’ve tightened the characters and highlighted their desires and problems. At least, I think I did. That’s what I need help with.

I also need help with:

Turkish language

Ottoman music

Ottoman art, poetry, cuisine, dance, etc.

Ottoman history

Bulgarian history

Islam

Programming

If you know more about those things than I do (i.e. more than what reading wikipedia gets you), send me a message and I’ll send you the novel. Or send me a message if you just want to tell me how to improve the story. I’m sending this thing to everyone!

If you’re curious but don’t want to commit, here’s the first chapter.

December 14, 2017

What if Oliver Cromwell didn’t get malaria?

…and lived to age 80, giving him 20 extra years to play proto-Napoleon in the British isles?

France gets its act together to fund oppressed Catholics, especially in Scotland and Ireland, who declare independence in the chaos following Cromwell’s death. In the Recusant War of 1678-1684, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Lancashire, and Maryland colony declare independence, with Scotland and Ireland successful, Wales and Lancashire brutally re-conquered, and Maryland re-conquered, then “liberated” by French colonists and their Native allies.

By 1700, French Acadia includes Maryland, Delaware, *Pennsylvania, and much of *New York state, and by 1800, Anglophone America is confined to Labrador and the Tidewater South, independent by default after the collapse of Cromwellian England and the proclamation of the 2nd English Republic. There’s also a big English-speaking population in New Amsterdam, whose relationship with Acadia is something like Singapore with Malaysia.

As the Republic of Acadia experiments with Enlightenment ideals and grows in power, the English Partnership (England, Labradore, Virginia, the Appalachian Empire, Jamaica, and a few scattered outposts on the Hudson Bay, the Caribbean, the African west coast, and the Indian east coast ) are known mostly for their persecution of religious minorities, and slave trade.

With the takeoff of the industrial revolution in the Netherlands and Acadia (including N’Ampster), England emerges as an ethno-nationalist military dictatorship (but at least they finally banned slavery). Modernization starts late but moves quickly, building a navy that, after some heady victories against the rusty French and Spanish colonial forces in Africa, tries to swallow the continent. Before the downsides to this plan become obvious, England, Appalachia, and Germany cook up a crazy scheme to take over the world, and invade all their neighbors simultaneously, setting off a world war. There’s also ethnic cleansing of Catholics and horrific psychological experiments on Quakers because why not?

Foreign occupation and annexation is why not. England gets split between France and Scotland, Appalachia by Acadia and Mexico, and English Africa, India, and Brazil evaporate (most of them ended up *communist). As Acadia, France, and Spain explode with prosperity and grapple with *communist India, English-speaking countries focus on commerce and technology.

When it reunifies in the 1980s, the Anglosphere is a surprisingly sensible economic and cultural union built along Scandinavian lines. Church attendance is way down, all the best electronic gadgetry (and porn) comes from England, and Appalachians are well known as sober businessmen-and-women working very hard to convince everyone they’re not racist any more. The Quakers got their own city-state!

Done with The Sultan’s Enchanter!

(which is what I’m calling Charming Lies now)

(and it’s just the latest round of edits that I’m done with but it’s still a big milestone, damn it! Including breaks I’ve been working on this thing for over four years!)

204 pages, 75,000 words, first line: “The ropes around his wrists and ankles pulled tight.”

While listening to: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=INl6c...

December 7, 2017

The Peoples of the Saharan Seas

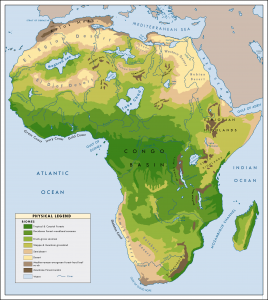

Just like Cody of AlternateHistoryHub, I was blown away by Sean McNight‘s map of the “Seas of the Sahara.” Sean’s map is about a future geoengineering project, and Cody’s scenario begins 7,000 years ago, but mine goes back further.

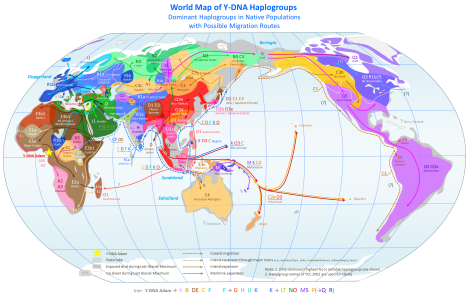

Say hello to Y-DNA Adam, humanity’s oldest common male ancestor!*

Two of Adam’s descendants went east and south to produce the Nilotic (A3) and Khoisan (A2, A3) haplogroups respectively, but a third went north to produce A1a. Had the Sahara been greener, this population might have grown.

In Our Timeline, a mutation occured either in central or west Africa, producing the Pygmy/Hadza people (B2). Similar Y-chromosomes show up in the southwestern Sahara as B1. So there’s our next population.

Mutations C, D, and E occurred on the way to the Horn of Africa. C and D went on to colonize the rest of the world, but carriers of E hapolgroup went north up the Nile Valley (producing the E3b1 NE African/Mediterranean and Cushitic people) and west across the north coast of Africa and the E3b2 Berbers), west to begin the Dogon (E1a) and Niger-Congo (E3a) people, and south in the more recent Bantu migration (E3a).

And don’t forget the mutation in Anatolia that produced the Semitic (J1) population, which colonized Arabia, Egypt, and parts of Northern Africa. Nor the R1b mutation in the Caucasus present in Western European and Chadic people. In This Timeline, they’re even hungrier for a piece of Africa, as are the southern Italians (J2), the I2a people now found in the Balkans and Sardinia, and even haplogroup G, once common in southern Europe but now found mostly in the Caucuses.

The result is an Africa (even) more diverse than the one in Out Timeline.

The El Eglab Desert in northwestern Africa is still inhabited by people something like Berbers (they speak an Afro-Asiatic language, but with an unexpected number of click phonemes). The desert people have have settled cousins living as merchant-princes around the Maghreb Sea, however, and they’re all in fear of subjugation by the only vaguely Berber Tamarasett Empire on the west coast.

The Choti Sea is especially diverse: a mix of Berbers, Semites, and a bunch of tall, grumpy Cyclopeans (they have two eyes, but they like building big stone temples).

The area around Lake Fezzan has its own merchant-princes (rather more prosperous than the ones around the Maghreb Sea), with ties to great civilizations of Italy, Greece, the Levant, (an oddly Indo-European) Egypt, and Chad. This has unfortunately meant a lot of slaving, with the diminutive hunter-gatherers of the deep savanna most often taken. The slave takers (mostly drawn from the people living around the the Sahabi and Rabiana rivers) speak an ergo-absolutive language and are pretty odd ducks, themselves.

Lake Chad is the pond of the Chadean Empire, where people speak their very own language family, and extend their power all the way from the Atlantic to the Ethiopian Highlands (home of a chain of Afro-Asiatic city-states that just WILL not stay conquered!)

Things get sketchy further south. Horses die in the Congo Basin, and while Chadian ships have passed through the Cape of Good Hope, they didn’t find much worth pillaging. Every now and then, when the state of the Horn of Africa are particularly troublesome, the Chadians (or even more rarely, one of those upstart Tamanrasettians) will find it profitable to hack some trading posts out of the jungle and sail “the Southern Route.” Generally, though, the Ethiopians are happy enough to mediate trade between Chad, the Swahili Coast, and distant India and China.

Oh, and some of the villages in the Tabernas Desert in Spain speak a language filled with clicks…

*I could have picked Mitochondrial Eve or some other metric of relatedness for the various ancient human migrations, but this map was the first one I found.

The People of the Saharan Seas

Just like Cody of AlternateHistoryHub, I was blown away by Sean McNight‘s map of the “Seas of the Sahara.” Sean’s map is about a future geoengineering project, and Cody’s scenario begins 7,000 years ago, but mine goes back further.

Say hello to Y-DNA Adam, humanity’s oldest common male ancestor!*

Two of Adam’s descendants went east and south to produce the Nilotic (A3) and Khoisan (A2, A3) haplogroups respectively, but a third went north to produce A1a. Had the Sahara been greener, this population might have grown.

In Our Timeline, a mutation occured either in central or west Africa, producing the Pygmy/Hadza people (B2). Similar Y-chromosomes show up in the southwestern Sahara as B1. So there’s our next population.

Mutations C, D, and E occurred on the way to the Horn of Africa. C and D went on to colonize the rest of the world, but carriers of E hapolgroup went north up the Nile Valley (producing the E3b1 NE African/Mediterranean and Cushitic people) and west across the north coast of Africa and the E3b2 Berbers), west to begin the Dogon (E1a) and Niger-Congo (E3a) people, and south in the more recent Bantu migration (E3a).

And don’t forget the mutation in Anatolia that produced the Semitic (J1) population, which colonized Arabia, Egypt, and parts of Northern Africa. Nor the R1b mutation in the Caucasus present in Western European and Chadic people. In This Timeline, they’re even hungrier for a piece of Africa, as are the southern Italians (J2), the I2a people now found in the Balkans and Sardinia, and even haplogroup G, once common in southern Europe but now found mostly in the Caucuses.

The result is an Africa (even) more diverse than the one in Out Timeline.

The El Eglab Desert in northwestern Africa is still inhabited by people something like Berbers (they speak an Afro-Asiatic language, but with an unexpected number of click phonemes). The desert people have have settled cousins living as merchant-princes around the Maghreb Sea, however, and they’re all in fear of subjugation by the only vaguely Berber Tamarasett Empire on the west coast.

The Choti Sea is especially diverse: a mix of Berbers, Semites, and a bunch of tall, grumpy Cyclopeans (they have two eyes, but they like building big stone temples).

The area around Lake Fezzan has its own merchant-princes (rather more prosperous than the ones around the Maghreb Sea), with ties to great civilizations of Italy, Greece, the Levant, (an oddly Indo-European) Egypt, and Chad. This has unfortunately meant a lot of slaving, with the diminutive hunter-gatherers of the deep savanna most often taken. The slave takers (mostly drawn from the people living around the the Sahabi and Rabiana rivers) speak an ergo-absolutive language and are pretty odd ducks, themselves.

Lake Chad is the pond of the Chadean Empire, where people speak their very own language family, and extend their power all the way from the Atlantic to the Ethiopian Highlands (home of a chain of Afro-Asiatic city-states that just WILL not stay conquered!)

Things get sketchy further south. Horses die in the Congo Basin, and while Chadian ships have passed through the Cape of Good Hope, they didn’t find much worth pillaging. Every now and then, when the state of the Horn of Africa are particularly troublesome, the Chadians (or even more rarely, one of those upstart Tamanrasettians) will find it profitable to hack some trading posts out of the jungle and sail “the Southern Route.” Generally, though, the Ethiopians are happy enough to mediate trade between Chad, the Swahili Coast, and distant India and China.

Oh, and some of the villages in the Tabernas Desert in Spain speak a language filled with clicks…

*I could have picked Mitochondrial Eve or some other metric of relatedness for the various ancient human migrations, but this map was the first one I found.

November 28, 2017

The Thitherlands

Japanese is great! Today I was talking with my teacher about the word yo (世). In general, it means “world” as in yo no naka ni wa iro-iro na ningen ga histyou da (世の中にはいろいろな人間が必要だ, or “in this world, you need different sorts of people”*)

But then we got to the subject of ano yo (あの世), the afterlife, the world of the dead, literally “that world over there,” as opposed to kono yo (この世), the world of the living, literally, “this world.” Kono is something closer to you than the speaker (i.e. “this”), while ano is something far away from both the speaker and the listener (i.e. “that there,” or “yon”), but there’s another Japanese spacial deictic word — sono — for things closer to the listener than the speaker (i.e. “that”). Being the good student that I am, I asked if there was a sono yo (その世), which ought to mean “that world.” At first my teacher was like “I don’t think so” then she suddenly nodded! Hai! Sono yo wa yuurei no sekai da ne? (その世は幽霊の世界だね) Yes! ‘That world’ is the world of ghosts.

So we got the world of the living (“The Hitherlands” one might say?), the afterlife or world of the dead (“The Yonderlands”), and a world between the two, close enough to touch but separate from us: the realm of ghosts. The Thitherlands.

I’d read the hell out of that fantasy trilogy, wouldn’t you?

*literally: “in the world, various people are necessary.” Gloss: “world ‘s middle in subject1 color-color ‘s human(s) subject2 necessary is.”

November 23, 2017

Fantasy Spelling

Today I’m thinking about spelling rules. English spelling rules are nasty, and experts like (with good reason) we shouldn’t try to mimic them in our constructed languages. Instead, we should use the general international spelling rules (a as in father, i as in ferarri, etc.) as default. No silent letters, no googly things over the vowels.

I agree, general international spelling rules should be the default. But if I left it there, I wouldn’t have much of a blog, would I?

Consider this: to ignore gnarly spelling is to ignore an avenue of worldbuilding. Allow me to demonstrate with the Niwyouwid, the language of the Niwyow people.

/jə aɪ gə’daɪje tə’juda waŋ’vjaɪjde ʃə ‘ʃnoʊkɪr tʃjuz jə tʃaw’juwa ʃə naɪk əˈzjuva dʒɪʒ tʃə pə ˈkeɪsɪpa ‘vaɪjəza:/

If I was an (anglophone) anthropologist stumbling on a pre-literate people or a rabid spelling reformer, I could transliterate that as, “Ye ai gedaiye-teyuda, wangvyaiyde she shnoukir-chyuz ye chawyuwa she naik-ezyuva jij che pe keisipa-vaiyeza.”

But any Niwyow person who saw that would have a conniption! How dare you erase our 1500 years of literary tradition! Spell the sentence properly, damn you! It’s, “Xo i gudiae taxudo, uhàngwxayde sho shñokir chuza xo t’ddhoxuo sho nyax azzuwo dhidh tho pu xasipo wixazzà.”

Now would you look at that nightmare? Saints preserve us, it’s got apostrophes, googly things over vowels, AND googly things over consonants!

But as Niwyow scholars will point out, these spellings all say important things about their history and culture.

I’ll let one of them take it from here.

Hi! I’m Wixazznyar, a second-year student of Niwyowid Philology at the Sayreu University. Call me Wixa! (it’s pronounced “WHY-ya”).

You probably have a lot of questions about that sentence Dan quoted. But don’t worry, Niwyowid isn’t actually that hard! Let’s start at the beginning.

Xo (pronounced “yuh”) = And. The letter X represents the Old Niwyouwid voiced velar fricative (/ɣ/ as in German damalige. English doesn’t have it. Sorry!!) Followed by an E or I, this consonant became “y” (IPA /j/). It is now used to indicate the “y” sound at the beginning or middle of a syllable.

I (“ai”) = He. A borrowing from the Pu Nichafawa, who invaded our country about a thousand years ago. I probably have some Nichafa blood in me!

Gudiae taxudo (“guh-DAI-yuh tu-YOO-duh”)= was standing, there somebody stood. The Classic Dathu gudia connotes bravery, nobility, standing against adversity. As well as a certain elegance of prose, if I do say so myself. uwu

Uhàngwxayde (“wong-VYAIY-deh”) = holding, X-in-hand. What a lovely word! The –wxay- in the middle is from Old Niwyouwid, and present in many other verbs that concern keeping or cherishing things. The addition of uhàng (from Iñàngi Kwàchey, which is not so different from the Kwàchey they still speak on the Continent) makes it clear this verb has to do with keeping things in your hands (I think the modern Kwàchey is wang?). Uhàngwxay is actually a word, and, yeah, it did once mean “hold,” but now it means “lose.” Like if hold back, you’re gonna lose? Putting in –d (from Classic Dathu) makes it clear that we mean “hold” and not “lose.” I suppose if I did something like that in English it would be “manu-keep-ize.” (lol did I get it right?)

Sho (“shuh”) = his. A nice Old Niwyouwid word.

Shñokir chuza (SHNOW-ker chyooz) = that sort of streamlined hat with ear-warmers? You’ve seen them. And this is an interesting one! Everyone associates the shñokir chuza, with Niwyow fashion, but neither of these words is native! Chuza is another Kwàchey word, also spelled chuza (but pronounced totallty differently: “SHOO-zuh” or smoething) and shñokir is actually from shuÑañtaf shñokir kutep (“SHNYO-keer KOO-tep”), or “helmet.” How exotic!

T’ddhoxuo (“chaw-YOO-wah”)=turned, jerked around. That t’ at the front is important! It’s a perfective marker, indicating that the action happened suddenly and then stopped happening (plain old dhoxuo means “somebody was turning there” or “somebody was in the process of turning when…”).

Nyax azzuwo (“naik uh-ZYOO-vah”)=wet with tears. Yes, not just any kind of wet. “Wet with rain” would be xeoa shxouo, “wet with blood,” nyar azzuwo, not to mention many other possibilities lol!

Dhidh (“jeej”)=face. Another Kwàchey borrowing. The Old Niwyow word for face af’n, has become avn. Don’t call anyone an avn, please! It’s a very rude word! owo

Tho (“chuh”)=to, into, toward. Why do you even have all those prepositions in English? One is enough!

Pu (“puh”)=the. Same as in “Pu Nichafawa,” who you should remember invaded us back in the first millenium. Their name means “the soldiers” in their language. Same pu!

Xasipo wixazzà (“KAY-sip-uh VAI-yuh-zah”)=wind. Careful with this one. Dathu xasipo means “wind” in the technical sense, like what meteorologists study. But take it away, and you get Wixazzà, which means “God!” Wow! The key is that -à at the end, which means “great X” or “holy X,” the same as in Kwàchey (for example Niwyouwid dhidh+à=dhidhà, “an earl” or Kwàchey jija+à=jijà, “a baron”). Take away that “augmentative suffix” and you get wixaz, which did mean “wind” at one point, but now means something more like “serendipity.” Like when something unexpected and good happens to you. So, if you want to talk about moving air, you have to say the whole thing: xasipo wixazzà. (BTW: don’t use xasipo in normal conversation. Some people are religious and this offends them.)

I hope you enjoyed my lesson! Let me know if you have any questions about wonderful Niwyouwid!!

Once again, this nonsense all came from Vulgar.

November 22, 2017

The History of Niwyowid

proto-Niwyowid (PNV)

Xe eisi yi zuha vei yi xe yi skyay avan eyii tyi exi. /ɣe eˈihi dzi ˈzɯha ˈvei dzi ɣe dzi skjaj ˈavan eˈjii ci ˈeɣi/ “And stood his hat holding he and his wet face turned to the wind”

Proto-Niwyowid speakers invaded their current homeland about 1,500 years ago, where they encountered and mostly displaced the native Fujilu. Although the proto-Niwyow people didn’t import much vocabulary from Fujilu (aside from place-names), their sentence structure was massively influenced by the Fujilu substrate. PNV also went through an intense phonological simplification, becoming Old Niwyowid, or N’fyouf.

Xeo shou ouha fe shou suha xeo xeou shou shay af’n tyou xou. /jeo ʃow ouh fe: ʃow sjɯh jeo jou ʃow ʃæj ævn tʃou jou/ “And he stood holding his hat and turned his wet face to the wind.”

And then the Vikings invade. Uh, I mean the …(rolls dice)… Pu Nichafawa…who spoke Old Tyihanyanyu (OTN). They didn’t do much to change N’vyouf sentence structure, but they added in a lot of vocabulary (including some pronouns and even definite articles) and re-introduced some phonetic diversity, which gets worn down in its turn by some new shifts. Late Old Niwyowid (ONV) or N’vyouf,

Xo i tautou feyieh sho shusi xo xouou sho asufou af’n tyo pu f’gith /jo i ta’uto: fejie: ʃo ˈʃusi jo jo’uwo: ʃo aˈzuvo: ‘avin tʃo pu viˈgiθ/ “And he stood holding his hat and turned his wet face to the wind.”

We see in Late Old Niwyowid the emergence of regular past forms (-ou) and participles (-ey) on verbs, as well as a tendency to accent nouns on their first syllable and nouns on their second (causing dipthongization to distinguish second syllables from tense/mood suffixes). Note new words i (from OTN hi meaning “he,” now distinct from sho or “his”), tautou (“stood” from OTN tatau inflected like an ONV past tense verb), shusi (“hat”, from OTN zhusi, replacing sih (PNV suha, which now means “cloak”), asufou (“wet with tears”, from OTN hasuva “soaked in bodily fluids”, as opposed to ONV shayouou which now means “wet with water/alcohol/etc.”), pu (“the”), f’gith (“wind” from OTN zhagi-vugidha or “god-stream”).

The next invaders were the Iñàngi, speakers of Iñàngi Kwàchey (IKW). The Iñàngi had a long tradition of legalism and literacy, which meant that their words had standard spellings. By the time Niwyouwid emerged from its 200-year unrecorded “dark age,” it had standard spellings too, beginning the Middle Niwyouwid (MNV) period.

Xo i tauudo uhàng-wxixe sho chuza xo taddhouo sho azzuwo dhidha tho pu wixazzà /ja i tə’wudo waŋ’vjije ʃa ʃuz ja tədʒow’uwo ʃa əˈzuvo ‘dʒiʒ tʃa pu ‘vijəza/ “And he stood holding his hat and turned his wet face to the wind.”

In addition internal phonological processes (reduction of unstressed vowels to ə or nothing, intervocalic voicing, the emergence of voiced fricatives as distinct phonemes), we see the emergence of the perfective past, formed from tadd- (from the same root as tauud, “stand”) prefixed to the verb xouo (“was/were turning”) to form taddhxouo (“turned”).

The Iñàngi introduced high-sounding particles to attach to native words, including the adjective marker –de (KW -ite) as in Niwyouwide (modern spelling “Niwyouwid”), and the augmentative –à as in wixazzà (“wind,” still worshiped according to Nichafa tradition). Some native words have been pejorated, such as avn (ONV af’n, “face”) which now means “a lazy or useless person” (In MNV, “face” is dhidha, from IKW jicho, “forehead”). Other KW words have become part of compounds, such as uhàng-wxixe literally “hand-holding” (from uhàng IKW “palm of hand” and feyi ONV “to hold,” now found only in compounds).

Borrowings from IKW have usually retained their spelling, and some native spellings have been altered to reflect the preferences of KW-speaking scribes (w=/v/, dh=/dʒ/, th=/tʃ/, and sometimes ch=/ʃ/, as is the case with chuza, which was borrowed into KW and back into NV). Other MNV spelling conventions are the result of native developments (double consonants indicate preceding shwas, x=/j-/, y=/-j/).

Modern Niwyouwid /’naɪvjəvɪd/ (NV)

Xo i gudiae taxudo uhàngwxayde sho shñokir chuza xo t’ddhoxuo sho nyax azzuwo dhidh tho pu xasipo wixazzà /jə aɪ gə’daɪje tə’juda waŋ’vjaɪjde ʃə ‘ʃnoʊkɪr tʃjuz jə tʃaw’juwa ʃə naɪk əˈzjuva dʒɪʒ tʃə pə ˈkeɪsɪpa ‘vaɪjəza:/ and he stood holding his hat and turned his wet face to the wind.

Modern Niwyowid is separated from Middle Niwyowid by the Enlightenment and Colonial periods, when Niwyow scholars reached back into classical languages (e.g. Dathu) and the languages of newly contacted peoples (e.g. Delta Ñañ) for new concepts. Spelling is now very standard, and loan-words retain their original spellings (though not pronunciations). Shñokir chuza, the most fashionable style of hat, is based upon the shuÑañtaf shñokir kutep, or “little military hat.”

Semantic drift has continued, as with taxud, which now means “stay, remain,” uhàngwxa (now, ironically, “lose”), and wixazzà (MNV “wind”), which now means “potential or unforeseen benefits.” “Stand in a place, be erect” is gudiae taxudo (from Dathu gudia, “upright,” pronounced /ˈgɯdia/). “Keep something in hands” is uhàngwxayd (with the addition of Dathu –d verbal suffix). “Outdoor movement of air” is distinguished as xasipo wixazzà (from Dathu xasipo, “wind,” pronounced /ˈxahipo/). The nyax in nyax azzuwo is also from Dathu (“tears” pronounced /ɲax/).

I owe a lot to vulgar, the conlang-generator.

And tune in on Friday for the funner version of all these technical notes.

November 20, 2017

Five Star Reviews: The Book of Joy

I made a promise to myself a while back to write a review for every book I enjoyed unreservedly all the way to the end.

I made a promise to myself a while back to write a review for every book I enjoyed unreservedly all the way to the end.

But what does “the end” mean? What happens when I use the book to put myself to sleep, then have to go back and listen again to parts I missed because I was asleep? (it was an audiobook)

What happens when I have to go back and read the last part of the book again, because I didn’t get everything I needed to the first time? Not to mention the fact that I will probably keep referring back to this book (especially that last section) for the rest of my life? At some point, I just have to write the damn review. So here goes.

When I was in the hospital in October, I spent a lot of effort staying sane.

While I might not have been…entirely successful in this endeavor, a lot of the progress I did make came from The Book of Joy.

The Book of Joy is a series of conversations, interviews, and anecdotes shared by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Tenzin Gyatso the Dalai Lama, and author Douglas Abrams. The book’s purpose is to teach people how to maintain joy. And it works.

Archbishop Tutu and the Dalai Lama go through the negative emotions one by one (anger, sadness, etc.) talk about where they come from, and tell us what to do about them. For example, the Dalai Lama relates an anecdote about a car mechanic who bumps his head on the corner of the car he’s working on. The pain angers the mechanic so much that he smashes his head into the car again. In the same way, some (maybe even most?) of the anguish we feel in our lives is self-inflicted. That’s a good thing. That means that at least some of our anguish can be under our control.

I won’t go into more detail than that — I’ll make a hash of it. Suffice to say that the Book of Joy is full of funny, wise, practical advice. Its authors are friends, and rib each other mercilessly (“We must accept both our own flaws, and those of others. For example, I can’t speak English well, and your nose is too long.”) They relate stories that would be fascinating simply as history, but imbue them with lessons that not only entertain and educate, but also also improve readers.

Listening to this audiobook was like medicine for me, and I plan to apply the lessons it taught me for the rest of my life.

November 16, 2017

The Scifi Rock Opera

I wrote this on the bus

We came from a distant society

To question your culture’s moralety

You’ve got forty days to revise all your mores

Or you‘ll become slaves to our empathy!

Oh ohhhh! Tremble with fear

We tell them, but they do not want to hear

Oh ohhh! Hopeless are we

Where can be the hero to set us free?