Markus Gärtner's Blog, page 16

May 1, 2013

Where are the German testers?

On the bottom of James Bach’s recommendations of people there is a small paragraph:

That One German Guy

Germany has no excuse. There are TONS of smart people there. How is it only one intellectual software tester has emerged from the ISTQB-addled masses to demand my respect with his work? My theory is that Germany has a more command-and-control culture, which perhaps disparages independent thought of the kind required to achieve excellence in testing. This pains me, because I am descended from Germans and I would love to visit and teach there.

Anyway, the one German guy who shines in my community is Markus Gaertner. I’ll do a write-up on him, shortly.

Yeah, it’s about me. From time to time I am asked by James and other people in our community where the German testers actually are. Here are some folks I am in touch with, that have raised my attention, and I think will need some attention from the wider community. There is not only one guy testing in Germany, seriously.

Meike Mertsch

Meike Mertsch is not only my colleague, but upon joining James’ tutorial at the Swiss Testing Day last year, James got in contact with me over skype along with these lines:

I have met Meike. Now I know two testers in Germany.

Meike is more a developer-tester, but I think she has some potential. I work with her partially as a colleague, partially as a mentor.

Alexander Simic

For quite some time I have been in touch with Alexander. He is working with James as a testing coach, and besides Meike and myself was the third participants at last year’s GATE peer workshop. Alexander is working in Freiburg, eager to meet other like-minded folks.

Maik Nogens

Maik and I started this thing called GATE a while ago. Last year, he couldn’t make the date, though. That does not mean that we are not in touch with each other. In fact, he’s right now co-organizing the Software Testing user group in Hamburg.

Tobias Geyer

Oh, yeah, Tobias is the guy that made me aware of the Software Testing user group in Hamburg at the Agile Testing Days 2010. Since then some things have changed, but I think highly about Tobias, and I think he started a great community in Hamburg there. It’s a bit of a pity that Hamburg seems to be the only user community in Germany I am aware of.

Ursula Beiersdorf

Ursula Beiersdorf right now co-organizes local testing events in Hamburg, Germany together with Maik. I think she is doing a great job in networking and getting testers together.

Stephan Kämper

In 2009 I sat in the same tutorial at a conference as Stephan Kämper. Over the years, I came to value our exchanges on testing, and the greater community.

Andreas Simon

Andreas Simon is the guy that went to the very first Belgium Testing Days on his own budget to attend the Testing Dojos that I facilitated there. We had quite some fun together. Over the past two years, we came to co-organize the local Software Craftsmanship user group in Münster-Osnabrück-Bielefeld, he also organizes Coding Dojos and Code’n'Cake meet-ups in Münster as well.

More

I think there are more. For example there was this guy, Ender Ekinci, who dived deeply into the problems with Parkcalc, and found a way to produce even higher parking costs.

There also is Moritz Schoenberg who I don’t know in person (yet). I became aware of him since he won the uTest award for the tester of the year in a row. I hope to get in touch with him at the next official GATE workshop.

Oh, and of course there is Christian Baumann who attended the first GATE workshop in Hamburg in 2011. He’s been on my radar before that. That usually means I had the impression he is worthwhile to follow.

A final disclaimer: I think I might have forgotten some more people I work with in user groups, and other communities. If you miss your name on this list, drop me a line, and I will check whether to do a follow-up with your name included as well.

Last, but not least, this should be a starting point for you, German testers, to get in touch with us. I think we can excel beyond the state of our craft that we are currently working in. But we need to network better for this to happen.

April 28, 2013

Debugging Communication

Here is a thing I learned from J.B. Rainsberger at XP 2012 in May 2012. I used it in the past months quite extensively for debugging communication based upon the Satir Communication model. While doing some research for this blog entry, I discovered that some others have also written about the topic. I especially liked Dale Emery’s Untangling Communication which seems to go a bit deeper than my understanding of the topic. Anyways, here’s my write-up which might give a different perspective.

The Satir Communication model

Family therapist Virginia Satir developed model about communication. Jerry Weinberg wrote quite extensively about it in several books. However, the first time I really understood the model, was in the context of debugging communications.

Let’s dive into the model, first. There are four phases when a a human receives any form of communication: intake, meaning, significance, and response. Let’s dive deeper into them.

Intake

During information intake we humans take in the message the other person communicating with us is trying to give us. We take in the words the other person says, we take in the body language, we also subconsciously notice things the person is sending to us. For a web blog this mostly consists of reading what is there.

Needless to say that the amount of communication we may intake depends largely on the communication channel used. For face-to-face communication the amount of information that I can notice is much wider than for example for text chat exchanges on the internet, or asynchronous written communication like email or twitter.

We’ll take a discrete look on the things that may go wrong in a few.

Meaning

After taking in the message as it was said we start to interpret the message based on our previous experiences with the person we are interacting with. That might mean that we come up with the worst possible interpretation, for example when we deal with an identified patient, that is someone we mostly see as the troublemaker. That might also mean that we come up with the most positive interpretation for a person that we love or feel close to.

We form interpretations based on our previous experiences with the sender, or based on our skills on intake. We combine the intake of the message together with our previous knowledge of the situation, the environment, and our previous experience in similar situations like this.

Significance

Taking our intake and our interpretations into account, we form significance to the message. Significance is based upon upon our feelings about the situation, how we experienced similar situations in the past, and the good or bad interpretations that we came up with. But also the surroundings of our family life might lead to different significance assignments for the message we received.

Response

Last, but not least, we decide whether or not to respond, and what an appropriate response will look like. We base our responses based on the information we took in, the meaning we formed from it, and the significance to the message that we attached to it. For example, in a particularly stressed situation in your family, you will respond differently as when everything is alright at home.

When things go wrong

But what happens when things go wrong? And how does the model help there? In order to debug communications, I go through the phases in order to check where something went wrong and to correct the situation from there. So, let’s go through the phases to see where communication might go awry, and what we might be able to do to resolve the problem early.

Intake

When something goes wrong during intake, we understand different things. For example when I write the word “integration test”, there are at least two different meanings I am aware – that’s why I usually try to avoid that term. Other such terms are for example to my experience “quality”, “testing”, and “agile”.

When something goes wrong during information intake, we end up with a misunderstanding. That means that the sender of the message had a different understanding of the term than the receiver, and we end up with something called ‘shallow agreement’ if we don’t find out about our misunderstanding before agreeing together on something.

In order to check for misunderstanding in our communication I try to ask clarifying questions. For examples when I am asked to create better quality, I ask for more specific details about the term “quality”. When someone asks me for “best practices”, I ask for a definition of that. I think that is also the reason why we allow clarifying questions in LAWST-style peer conferences.

Meaning

Weinberg’s famous Rule of Three Interpretation origins from this phase. To cite Quality Software Management Volume 2 – First-order measurements on page 90:

If I can’t think of at least three different interpretations of what I received, I haven’t thought enough about what it might mean.

That means that at times I might end up with a different interpretation than the sender has. If we are not on the same page regarding our understanding of the words, it is also clear that it’s more probably that we end up with different interpretations regarding the situation.

When dealing with misinterpretations, that is we attach different interpretations to the communication than the sender tried to send to us, we need to explore the situation a bit deeper. How come the sender came to the interpretation? What other intake of the situation did he come up with? Most of the time I find out there are other contributing factors that I was not aware of so far. By asking the Data Question I at times explore the interpretation:

What did you see or hear (or feel) that led you that conclusion?

(Gerald M. Weinberg, More Secrets of Consulting, Dorset House, page 114)

Significance

In regards to significance, I need to go a bit deeper. I need to explore feelings of the sender. For me to understand the significance the sender attaches to a particular situation or communication, I need to ask for previous experiences. I don’t have that many experiences with dealing with those situations. Most of the time this highly touches our inner beliefs. To be honest, I have not found many ways to change those other by providing different experiences.

I haven’t been in too many situations where communication went wrong in the response part. That’s why I don’t dive deeper into it here.

Last, but not least, I usually find myself already in better communication with the first two parts, as most of our communication seems to go awry there.

April 25, 2013

The Wandering Book

Recently I restarted the Wandering Book. The Wandering Book is a tiny book passed on from Craftsman to Craftsman, fromCmmunity to Community intended to collect the Zeitgeist of Software Craftsmanship. I deliberately decided to start passing this to the German Softwerkskammer user grups. The idea is to collect the different notions, sort of a guest book of all the local events happening all over Germany.

Since the first book seems lost, I decided to put a disclaimer in it at the beginning. Here is the initial entry I made.

More than four years ago, Enrique Comba-Riepenhausen stated something called The Wandering Book. It was a tiny book like this one and a website where you could sign up for it. Once I realised what it was, I signed up immediately. Since I need longer sometimes, I was at position 54 or something in Enrique’s list. Then in late 2010 I received the book finally.

I made my entry in it, shared pictures of it on my blog and forwarded it to the next adress as instructed.

I never saw The Wandering Book again.

Neither physically, nor virtually. Things changed, so now the web archive of the original book is ever gone. All Zeitgeist from these early days of the Software Craftsmanship movement – seems – lost.

A few weeks ago I decided to restart this. Thus I called out for the German communities, and we decided to pass this around in the local events.

So if you find this precious book and you don’t know what to do with it, it’s probably lost – again.

Please find the next local Software Craftsmanship community and pass this on to them. The History of Software Development will thank you.

April 1, 2013

Ukrainian Testing Dojo Number 3

Andrii Dzynia sent me this report from the third Ukrainian Testing Dojo. This is the English language report for this Russian original. I still think they are doing awesome stuff over there in the Ucraine.

Testing Dojo Ukraine #3 has taken place last week.

Some of the participants were there third time already. Means they like it and want more

The goal of the event was to test Android application – CxRate. One of the founders of the application Alex Filatov visited us to present this app and help guys with questions and potential issues.

We spent first session for touring over the app to understand it’s purpose and features. All the participants were working in small groups that helped then to collaborate better.

When 25 minutes passed we started our first Debrief. Using PROOF mnemonic (Past, Results, Obstacles, Outlooks, Feelings) each team gave short feedback about stuff they did and which areas left to be tested.

One of the team prepared Functional Map that we shared on the screen for all audience.

Seconds session was much more intensive. Next 25 minutes testers was strongly focused on bug-hunting process to find as much bugs as possible. Alex(app developer) helped a lot with all the questions that occurred from the guys.

After next 25 minutes and one more Debrief I’ve made small presentation to the testers/reporters about mnemonic for mobile testing called “I sliced up fun” by John Kohl. It gave more ideas that can be tested in the app.

Third session was the latest and was focused mostly on preparing useful and readable report. Each team sent their report to the developer with the bugs list and suggestions. Alex said they have to postpone the release for two week to fix all those issues. But the product definitely will be higher quality it was before!

At the end we did small feedback session to talk about Testing Dojo in general. Participants gave many interesting suggestions and ideas how it can be improved.

Stay tuned with Testing Dojo Ukraine!

March 20, 2013

Automated vs. exploratory – we got it wrong!

There is a misconception floating around that Agile Testing is mostly about automated checking. On the other way the whole testing community fights since decades about the value of test automation vs. the value of exploratory testing. I find these two different extreme position unhelpful to do any constructive testing. Most recently I ended up with a model that explains the underlying dynamics quite well, to testers, to programmers, and to their managers. Here’s the model.

Reasons to repeat a test

There are several reasons why you would want to repeat a test. In my consulting work I have met teams that hardly could remember anything about their work from two weeks ago. With the ever more complex systems that we deal with, automated tests can help us remember about our current thought process today, so that we won’t forget them once we revisit our code.

In his book, Tacit and Explicit Knowledge, Harry Collins explains that a transformation of a message can yield knowledge transfer. Automated tests are a way to transform our current understand about the software system in a way that we can utilize tomorrow to remember it. The transformation of our current understanding about the software system in terms of an automated then becomes a pointer to the past.

This pointer comes in two flavors. First, TDD practitioners often talk about test-driven design. Automated unit tests are a by-product of that work. When using TDD automated tests then become a way to foster our design understanding in an executable manner. Automated unit tests put constraints on our understanding of the underlying technology. They help us get from the chaos technological incompetence to a complex or even complicated understanding about the system we have to deal with.

On the other hand, automated end-to-end tests help us reach a better understanding of the underlying business domain for our code. Using a specification workshop can help us discover the right amount of domain knowledge to get started with. We might also find out while implementation that understanding that there is yet more to discover in this regard. When we automate our domain understanding, we are probably working on the level of an end-to-.end tests from a business user perspective. Therefore we codify also the view of the business problem that we are trying to solve. After all, Acceptance Test-driven Development, Domain-driven Design, and Behavior-driven Development are all part of understanding the business context, and the very business problem that we would like to solve with our software product. Automated tests derived from either of these approaches helps us remember our domain understanding tomorrow.

Overall, this explains the struggles between TDD, ATDD, and BDD together with DDD. You can use any of these techniques to explore the technology or the domain. They have their advantages at times when you don’t understand the underlying technology or the underlying business domain. They help you tackle one or another, at times even both. In the end, whether automated or scripted, we foster an understanding about our software with a repeated test.

Reasons to explore

With all this automation in place there is really no reason why we would need to explore, right? Sorry, that’s obviously wrong. There are certain things that we know, and we can make this knowledge explicit for tomorrow. But there is also stuff that we don’t know. And this comes in two different flavors:

Conscious Ignorance is all the stuff we are aware that we don’t know it. Any risks that might become real on a project are examples of conscious ignorance. Since we are aware of these, we can come up with mitigation strategies to tackle them.

Unconscious Ignorance on the other hand is all the stuff that we don’t know that we don’t know it. Dan North referred to this as second-order ignorance. These are all the risks that we drives down our projects, since we couldn’t come up with mitigation strategies.

Exploratory Testing really is about tackling with the these two ignorances. We want to use manual exploratory tests to check whether we any risks became real, and we should install our mitigation strategies now. Automated tests then might become one mitigation strategy for a particular risk, but also exploratory testing is one in this regard.

On the other hand, all the stuff that were not aware of that could become a problem, can be explored with manual tests. We would like to find out serious stuff that can become more than a burden on our development effort tomorrow, so that we can learn more about the problems and mitigation strategies for it. Exploratory Testing helps us to discover the stuff that we are not aware of, yet. In the end, if we were aware of them, we could have written an automated check for that, right?

While automated tests focus on codifying knowledge we have today, exploratory testing helps us discover and understand stuff we might need tomorrow. This is crucial, since the stuff we were unaware of might become an obstacle in tomorrow’s work. After we learned about things we didn’t know, we can make a more conscious decision whether to dive deeper, and automate that stuff, or whether to ignore this new information for the time being. Exploratory Testing then really is about learning new things, our conscious and unconscious ignorance about the project we are dealing with.

Are we dealing with the right problem?

In the past year, I learned about polarity management. In essence when struggling between opposite sides we should rather wonder whether we are solving the right problem. Manual exploratory testing and automated testing are two such polarities. Applying thoughts from polarity management, I wonder whether we solve the right problem with answering the question about manual or automated testing with an extreme position.

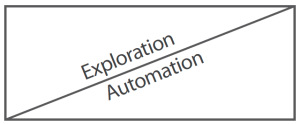

Automated tests help us remember our current knowledge about the technology and the domain of our software. Exploratory Testing helps us make us aware of our ignorance in certain regards, our underlying assumptions. Rather than asking ourselves whether we should strive for automated our manual testing, we should rather ask ourselves, how much automated testing can we sacrifice to enable us to learn about new things about our product, and how much knowledge we will need tomorrow. Of course, the latter piece is also part of our unconscious ignorance. Really, it’s about finding the right balance between learning things we are unaware of yet, and foster understanding we have today. So, how much learning can you skip to get that knowledge codified? How much codified knowledge can you skip to tackle more risks? The answer to these questions surely deserves some contextual thought.

March 3, 2013

My journey with Jerry Weinberg

I came across this blog entry earlier this week. While I also can resonate with most of the books that Soronthar read from Jerry, I felt like to tell my own story with Jerry’s books. Among my colleagues I am most well-known to cite a lot from Jerry’s work – mostly that is because I took the effort to type-copy the references to his meaningful laws on my computer, so that I can pull out Rudy’s Rutabaga Rule from the Secrets of Consulting quite easily:

Once you eliminate your number one problem, number two gets a promotion. (The Secrets of Consulting, page 15)

But that’s not where my story with Jerry started. Here’s the full story.

One word of disclaimer: I know a lot of people that are not comfortable reading Jerry’s books. To most of them I have a lot of respect. And I think it’s ok, if you can’t read his books. I am just going to share, what I learned, and what sticks even years later.

The first piece I read from Jerry was in Project Retrospectives. Yeah, he didn’t write the book, Norm Kerth did. But Jerry wrote the foreword. Back then, I was not aware that he wrote that foreword. I also know that Norm Kerth has been a student of Jerry, and was probably heavily influenced by him.

The first complete book was Becoming a Technical Leader – An Organic Problem-Solving Approach. The stuff that sticked mostly from that were the Motivation – Organization – Innovation pillars for leadership, and his three obstacles to innovation, and how to overcome them. To make a long story short, you can only innovate if you happen to learn from your failures, look what others are doing, and combine two great things with each other. For the third piece, I think I ended up doing that a lot of times.

Back then, Matt Heusser made me aware that Jerry had written a book on testing: Perfect Software… and other illusions about testing – together with James Bach. Jerry explains the Satir Interaction model in the book, and describes the dilemma of the Composition and Decomposition Fallacy in Software Testing. There are many more lessons in there, but these two sticked the most with me over the course of the past three years.

Immediately after that I had to get through the Quality Software Management series. Starting with Quality Software Management Volume 1 – Systems Thinking my journey in systems thinking started. With his diagrams of effect, I was easily made aware of certain systemic effects in the world I lived in back then. Of course, the fundamental definition of quality still sticks with me from page 7:

Quality is value to some person.

I followed up with Quality Software Management Volume 2 – First-order measurement. Here I learned the problems with replacement measures like lines of code, or estimated story points, or bug counts. In the second volume Jerry also introduced the Satir Interaction model, and I firstly became attracted to the Rule of Three interpretations:

If I can’t think of at least three different interpretations of what I received, I haven’t thought enough about what it might mean.

In Quality Software Management Volume 3 – Congruent Action I learned about Satir’s concept of congruency, and what might trouble me if the words I spoke and my actions did not match each other.

Quality Software Management Volume 4 – Anticipating Change finally helped me understand the MBTI model, and the different forces a change agent will face. Together with the Satir Change model, I learned a lot about human psychology in the software business.

Back then, I was about to start my job at it-agile GmbH. That’s why I started diving into The Secrets of Consulting and directly followed by More Secrets of Consulting. These two books helped me see a lot of stuff that I am still digesting years later. Not only about pricing, and finding a job as a consultant, but also about attitudes when it comes to dealing with a potential and not-so-potential client.

After that I took a deeper look into Are your lights on? – How to figure out what the problem really is, co-written with Don Gause. The two authors give broad examples of problems which could have been solved in another way, but finally were solved more cleverly. This is an essential lesson to some of the developers out there, that try to solve any problem by writing a program – sometimes to the extent to write a program that writes programs. The story in particular that influenced the title of the book still sticks with me.

Then I went on to Amplifying your Effectiveness which is in essence a collection of essays from various authors for the first AYE conference. The final one was last year, and I never got to attend it. Still, I learned a lot from all the hosts from the first AYE conference – on psychology, leadership, and what their role in software development is.

An Introduction to General Systems Thinking was an interesting read, but not so much sticked with me over the years. The whole book boils down to “thinking in General systems is a fruitless effort” – at least for me. It was interesting though to dive into the various stories Jerry told along the line.

At the time I was writing ATDD by example on my own, I dived deeper into requirements gathering. Exploring Requirements – Quality before design is a must-read in this regard. This is not only the origin of the famous story about the Swedish Army dictum, but also a source of so many insights on what requirements gathering is all about, and what it is not about.

After that, I dived into Weinberg on Writing – The Fieldstone method. Besides providing me a few tricks on my own writing, I also learned about the fieldstone method, and that a writer can only become better by writing. I still have to find a way to organize all my stuff well enough. One of these days I am going to fiddle a way to use fieldstones more effectively. So far, I have not been able to do so.

Directly after attending PSL in May 2011, I brought home a two more books from Jerry which I wasn’t able to get in Germany before that. Rethinking Systems Analysis and Design was one of these two – the other I still need to read. Together with Exploring Requirements I finally grasped what requirements gathering, design, and implementation tried to eventually achieve in the earlier days of programming. There are traces left in our industry, and it seems we finally got our head around these topics.

Not a book by Jerry, himself, but for his 75th birthday, The Gift of Time was next on my journey. A lot of people describe their very own journeys with Jerry over the course of the years. A lot of it is about that PSL experience, and what you can learn there – not so much what in particular, but what the different participants took away for them.

Made aware by The Gift of Time, I had the chance to get a copy of Computer Programming Fundamentals – together with Mr. Leeds. This is the first book to mention software testing (written in 1958), and it held a lot of other interesting insights that still hold – half a century later. My favorite quote from that book is

One of the more dangerous occupational hazards in computing is the habit of working out a set of diagrams, formulas, and figures until some impressive statement like “twice as efficient” emerges.

In this regard the past fifty years didn’t change anything.

In the past year, I was able to read more about the background for the problem-solving leadership course in Jerry’s currently being written series on Experiential Learning. Together with the 4Cs from Training from the Back of the Room I found all of these lessons a fruitful combination for learners. Since then nearly no class has passed without me trying out different things from either of these sources.

Finally, just today I finished a piece which stood on my bookshelf unread far too long. The Psychology of Computer Programming was a great read, and I still digest most of the information. Although most of the lessons on psychology there might seem dated, it turns out not so much has changed in the programmers and the program managers. The only thing that has changed, maybe, is the name of the methods we use nowadays. From that perspective it’s a bit sad to see that not so much has changed in about half a decade in our industry.

That’s what I read so far. The only tragic thing about all these books is probably that the only book I have left to read from Jerry is The Handbook of Walkthroughs, Inspections, and Technical Reviews. From skimming the pages it seems to be more of a guide and FAQ. With the other 50 books on my unread shelf, I don’t know when I will start this one. Oh, and if you happen to know a good book from Jerry not in this list, I am open for recommendations.

What’s your story with Jerry’s books?

February 26, 2013

Conferencers anonymous

I have a confession to make: I am addicted. In this blog entry I would like to warn you about it, so you don’t go the same route down as I did. Don’t follow me on that path, even if the temptation looks promising and convincing.

You don’t have a clue what I am talking about? I talking about conferences. I am addicted to them. In this blog entry I would like to foster my coming-out, and provide the things that make me addicted. Don’t fool yourself that you won’t become addicted. Stay away from conferences! Don’t go there!

You will feel and be smarter

This is the hardest one. Since you are among so many clever people, you will become infected with cleverism. Sure, that means that you will easily grasp stuff, and feel overwhelmed. However, when you get back to your workplace, you will feel stupid, and feel the urgency to leave for the next conference as fast as possible.

All those clever ideas from the conferences usually last about one week for me. That means, one week after the conference, all those thought exchanges and coffee-(or rather beer-)break discussions will be gone. None of the ideas actually will make sense any more. This my become frustrating to the extent that you may want to leave for the next conference immediately again.

The only way to break this feedback loop is to not go in first place. Stay home, stop your illusion that you will learn stuff at that place. It will be gone long before you can put stuff into practice.

You will meet a bunch of new folks

Yeah, there are lots of folks going to conferences these days. The bigger problem is that you will be robbed any illusions about the personality of all the folks you just know through twitter, facebook, and the like. Sure, you will learn a lot of folks from face-to-face. But also imagine how many people you will have to remember just after the conference.

When you are like me, you will easily forget names. That means the next time you run into that person you will have a hard time remembering the context of that face, and where you have met the first time. Was it virtually? Which online conversations did you have together? Which conference did you meet the first time again? What is your common background?

Also, your contact lists on stuff like xing or linkedin will explode that way. Just imagine all those gazillion folks at conferences who will add you to the latest fad in social media. So, you will also go down the drain to maintain multiple profiles at the same time. And keeping in touch with all those folks will soon become a nightmare. So, don’t go there to start with.

You will get lots of ideas

This is a side-effect of feeling more clever. The bigger problem usually is that you can’t put all those ideas into practice once you get back to your unclever working place. That sometimes means you will leave the company and head for greener pastures. But you can’t change jobs just because you went to a conference, can you?

At least, probably you shouldn’t. Another problem with all those ideas is, that the best ones usually come up after a bunch of booze in the bar in the night. That means that you will hardly remember one of two of them, once your alcohol level gets set back to a reasonable degree. That’s too bad since all those ideas will be lost, and you will feel bad about wasting so much of your time.

Don’t become addicted like me!

Don’t visit conferences like Let’s Test, TestBash, CAST, XP, Agile, Agile Testing Days, only to name a few. Stay away from them. You will become addicted. The only way out is to stay home, and read the hashtag stream from all those places. You can still dream that you miss a lot, but better keep that dream. The other way leads to suffering.

Stay away from those cool conferences.

February 24, 2013

Software delivery is fundamentally broken?

A while ago, Elisabeth Hendrickson wrote a piece on endings and beginning. There was one sentence striking out to me:

I believe that the traditional software QA model is fundamentally and irretrievably broken.

I think there is something fundamentally broken in the way we are used to build and ship product. Triggered by Elisabeth I had an eye on stuff while starting to read The Psychology of Computer Programming only recently – yeah, I didn’t read all of Jerry’s books so far. Shame on me. These are my early raw thoughts on what might be broken.

To be honest, The Psychology of Computer Programming is more than 40 years old right now. So, what could you learn from a book that old? There is much in it, since it deals with the topic of psychology – a topic still that is still getting too few focus these days.

There, in chapter 4 on the Programming Group, I found a particular discussion about a topic which has been given few thoughts earlier these days. The effect is called Cognitive dissonance. What’s that? To cite wikipedia

Cognitive dissonance theory explains human behavior by positing that people have a bias to seek consonance between their expectations and reality.

That means that cognitive dissonance will make you biased towards believing whatever you want to believe. If you want to believe that the new car you bought was cheap, you will reject news about the price being lowered two weeks later.

What has cognitive dissonance to do with programming? Cognitive dissonance is the most often cited reason for claims for independent testing teams. IF the tester is part of the development team that created the product, then he will be biased to confirm the product is working.

Now, this is what the theory explains. Empirical data from agile teams with testers among them however, might point to a different conclusion. Sure, there are teams which would be better off with independent testers – probably off-shore in some other timezone across the planet. But that’s not my point.

Imagine, that at some point in the history of software delivery, we have been led astray by cognitive dissonance to form independent test teams. From that point on, the whole QA movement set off, leading to more and separation of testers and the remaining folks. At times, it seems like a whole caste of testers was created, which are less worth than those precious architects, designers, and programmers.

Recently, teams that overcame this second-class citizen testership since then have shown to be more productive with fewer errors. At least this makes me wonder how the world of software development today in the 21st century would look like, if we had found ways to overcome cognitive dissonance 50 years ago.

Sure, testers now-a-days have their role to play in software development. But what if this was just an evolution that moved us in the wrong direction? Think about it. How would software development today look, if programmers learned satisficing testing in the university, if they did pair testing of each others’ code – I saw a medical company doing that. Their first tester became that team’s ScrumMaster. And they are doing well.

I think it’s time to shake some of the foundational beliefs that we carry with us for decades now. Our ways to deal with cognitive dissonance and the call for independent testers is one of these foundations that I would like to challenge.

February 3, 2013

Software Testing is not a commodity!

Stick in software testing long enough, and you will see enough ideas come and go to be able to sort out the ones that look promising to work, and the ones that you just hope will go away soon enough so that no manager will pay any of her attention to it. There have been quite a few in the history of software testing, and from my experience the worst things started to happen every time when someone tried to replace a skilled tester with some piece of automation – whether that particular automation was a tool-based approach or some sort of scripted testing approach. A while ago, Jerry Weinberg described the problem in the following way:

When managers don’t understand the work, they tend to reward the appearance of work. (long hours, piles of paper, …)

The tragic thing is when this also holds true for the art of discovering the information about how usable a given piece of software is.

Why do we test software?

If we were able to write software right the first time, there would be clearly no need to test it. Unfortunately us humans are way from perfect. Take for example the book I wrote mostly through 2011. 200 pages, lots of reviewing, production planning, and stuff happening in the end. And still, while reviewing the German translation, I spotted a problem in the book – clearly visible at face value. I had spend at least 2 weeks after work to go through the book once more, and get everything right. Yet, I failed to see this obvious problem.

The problem lies in our second-order ignorance: the things we don’t know that we don’t know them. These are the things of good hope, and prayers that it will work. Murphy’s Law also has a role to play here.

The very act of software testing then becomes to find out as much information about our unawareness as possible. This includes not only exercising the product, but also finding out new things about the product. Skilled testers learn more about the product and the product domain and the development team over the course of the whole product lifecycle.

Why do we repeat tests?

But how come we focus on regressions to often in our industry? It has to do with first-order ignorance. A regression problem is a bug that gets introduced a second time, although it already had been fixed in the meantime. Since we were already fully aware of the problem, the bug is no longer something that we don’t that we don’t know it. It has become something that we know now, but we don’t know whether we will know it still tomorrow. That’s why we introduce a regression check for tomorrow, so that it will remind us about the problem that we tried to avoid at this time.

Read that sentence again. Yes, it’s speculation. We speculate that we might break the software tomorrow again. With this speculation comes a whole lot of costs. We have opportunity costs for doing the test, for automating it, and with every run, we have the opportunity cost of analyzing the result (if we have to).

We wouldn’t need this if we were able to realize that a regression bug introduced in our software is an opportunity to learn what is not working in our current process that caused that bug to re-occur. Every regression bug discovered should be an invitation to start a root cause analysis and fix the underlying problem rather than deal with the symptoms.

That said, when you end up a lot of regression tests, and do not find a better way to deal with the situation than to demand more tests, you lack to realize that you should be doing something else. Or as Einstein famously once said

Trade-Offs

So, testing on the one hand is learning and providing information. But what about the human side of software development? Right, us humans are inconsistent creatures of habit as I learned from Alistair Cockburn. That means if we focus on the mere discovery of information, we are probably going to miss those opportunities to see where we were inconsistent and introduced a regression problem. If we focus on regression problems only, then we will suffer from inattentional blindness.

As I learned through Polarity Management, if you find yourself struggle from one point to another, you are likely solving the wrong problem. In this case, we should strive to find a trade-off between enough learning on one hand, and enough awareness of regression problems on the other hand.

What has all of this to do with software testing being a commodity? Software Testing is not a commodity in the sense that you can try to scale and maximize the efficiency on your project. You will have to deal with stuff that you learn in the meantime, and you will also have to deal with different things where your software development process is broken. The act of management, and the act of test management for the same reasons should therefore strive to find the right trade-off between exploration and regression prevention for their particular project context.

January 31, 2013

The Three Ages in Testing

On my way back from the Agile Practitioners Conference 2013 in Tel Aviv, Isreal I digest lots of information and bar discussion content. After attending Dan North‘s tutorial on Tuesday, I have six sheets of paper on notes with me, that will probably fill my writing buffer for the next half year. Time to get started. Here I connect Dan’s model of the Three Ages to Software Testing.

What are the Three Ages? The Three Ages describe a model of growth for a product. The three different ages in short are Explore, Stabilize, and Commoditize. In these three different ages, you have different gaps to fill.

Explore

In the first, Explore, you focus on learning and discovery. In a software product sense, you start to learn about the problem that your customer has, ie. by interviewing him, by running minimal viable products, or by working in his context. At this point you want to find out as much as possible to make sure that you understand the problem well enough to do something about it, to solve it. Here you optimize for discovery.

In software testing you do the same thing in different ways. When doing Exploratory Testing, you are learning a lot. According to Wikipedia Exploratory Testing can

concisely [be] described as simultaneous learning, test design and test execution.

After executing one test, you can take the outcome of that test, to inform your next step. That might be to dive deeper into the system, to find out more about that possible bug you just observed, or to continue with your current mission.

And there is more. When doing session-based test management, you can use a touring approach to learn as much about a product as possible in a given time-box, to plan out more sessions to dive deeper. Here, you do the same exploration and learning loop on a broader level. You explore the application to inform the next step, that is to plan your test strategy for the next couple of sessions.

The same holds true for backlog grooming meetings that many teams nowadays seem to do. Here you try to explore the technical and business constraints. Why is this relevant for testing? This is relevant for testing that particular piece of software later, as you are able to consider different constraints for all the variables that you can find. Variables in short are anything that you can vary in a product or product domain. There are technical limitations like the amount of bits stored internally that you may vary, and there are business and domain constraints that you might want to explore. The specification workshop and the backlog grooming meeting is the place to find out more about these.

Stabilize

In the stabilization age you aim for repeatability. So far, your learning has proven that you can do it – once. Now is the time to prove a repeatable success with your product. Arguing from the Lean Startup model, you have analyzed the problems your customers are having, and now you start to evaluate whether your product solves the problem for your customer.

With regards to software testing, at this point I would consider the parts that I want to automate to free myself time to learn more about the product later. Usually, I aim for a trade-off between learning and repetition – fully aware of my second-order ignorance: the things I don’t know that I don’t know them. The stuff that I know, I can automate – but only to be able to learn more about the things I don’t know. This is where test automation is more useful than using my spare brain cells at boring repetitious stuff.

Commoditize

In the third age, you try to make your product a commodity. You have reached the point to scale your customer base, and should be able to constantly grow. In the Lean Startup sense, you have developed your customer base, and can now aim for the big market. You have proven that your product solves the business problem. Now is the time to scale, and make your business model more efficient to fit the target market.

Unfortunately I see a lot of software testing projects failing to realize that they need to make their test automation more efficient. In the model, they fail to understand the need to make automated tests as fast as possible – and to refactor existing automation code structures to be flexible in the near future.

The model in action

In retrospect I realized that I had used the underlying thought-process a few years back. One of my colleagues and I were called into a project which was half a year late. There were three weeks left, and no automated tests. My colleague and I sat together and identified different test charters, and different tests to run in the short timeframe.

For the first week we started with completely manual tests. That was hard, as the test setup times were quite long. Our goal here though was to learn more about the new business domain which we didn’t know at that time. By re-testing the bugfixes, we were able to conduct that learning. We were tackling with the first age.

At the end of the first week, I became impatient. We were doing the same tests over and over again. On that Friday we sat together, and identified what to automate first. We had reached the point where we learned enough, and it became time to enter the stabilization age. We lay out a plan to tackle the different use cases and come up with automation for all the bits. We focused on repeatability of those tests. Two weeks later, we were done with that, and had been able to support the on-going UAT in that time.

After that, the project continued, and we were able to enter the third age as well. We started to make the automated tests more convenient. We started to make the whole flow more efficient, cleaned up the test automation code, and updated the commonly used library that we had grown over time. This is the third age in Dan North’s model.

To me, the Three Ages appear to be a useful model to understand where you currently are, and what your current focus probably should be.