Kathryn Mockler's Blog, page 15

March 7, 2025

I have found a couple of valuable resources which I’ve collected below.

We’re inundated with Substack “how-to” posts which can be annoying.

But along the way I have found a couple of valuable resources which I’ve collected below.

Really Good Business IdeasHow to Add a Table of Contents to Your Substack Articles (And Why You Should)Read more6 days ago · 78 likes · 19 comments · Casandra Campbell

Really Good Business IdeasHow to Add a Table of Contents to Your Substack Articles (And Why You Should)Read more6 days ago · 78 likes · 19 comments · Casandra Campbell Substack Writers at Work with Sarah FayHow to Write or Revamp Your Substack About Page to Draw SubscribersThe magic of writing and revising your Substack About page…Read more24 days ago · 87 likes · 140 comments · Sarah Fay

Substack Writers at Work with Sarah FayHow to Write or Revamp Your Substack About Page to Draw SubscribersThe magic of writing and revising your Substack About page…Read more24 days ago · 87 likes · 140 comments · Sarah FayHave you come across a good or helpful resource?

Share below in the comments.

March 6, 2025

Junction Reads, Wild Prose Readings, Mary Turfah, Deborah Dundas interviews Omar El Akkad, Remembering Canadian artist Kelly Mark, fiction by Amber Nuyens, Hannah Black, David Lynch & more!

Send My Love to Anyone is a newsletter on all things writing where Kathryn Mockler writes about the writing process and other troubles and invites guests to share their work.

Send My Love to Anyone supports small and independent presses and writing that intersects human rights, collective liberation, anti-oppression, and the climate crisis.

Send My Love to Anyone is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support this project, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Learn more about Send My Love to Anyone

What’s in Gatherings Issue 44My NewsMy video Do You Know What’s Great adapted from a story in my short fiction collection Anecdotes will be screening online at the Reel Poetry International Festival.

Screening: Wednesday, April 2, 2025 at 1:00 - 1:30 p.m. CST and 7:00-7:30 p.m. CST

Kirby News

Kirby NewsKirby will be having the grand good fortune to read in support of Jessica Hiemstra's new book Book Root (Goose Lane Editions) along with fellow poet Shannon Bramer at the palace of poetry, The Printed Word, Dundas, ON, March 20th 7pm.

Kirby, will be live on April 17 at 7:00pm (EST) chatting with from Junction Reads!

Events

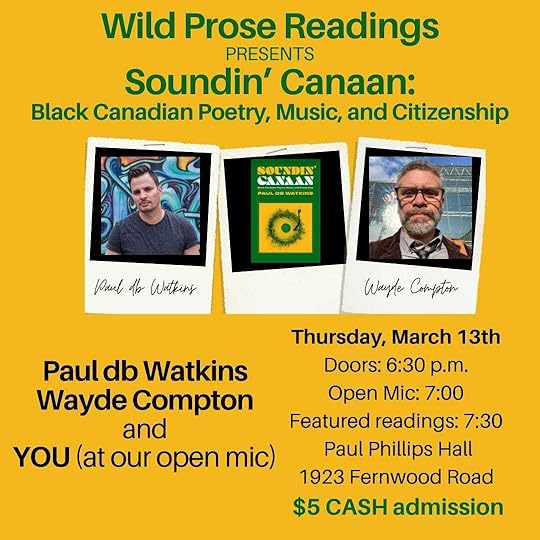

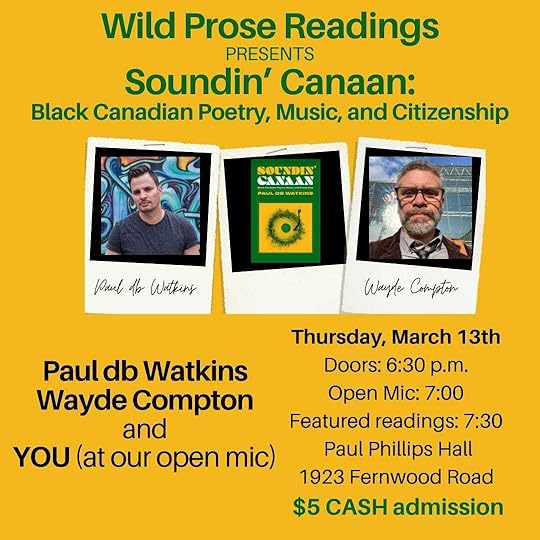

Events’ Wild Prose Readings Presents Soundin’ Canaan: Black Canadian Poetry, Music, and Citizenship with Paul db Watkins and Wayde Compton on March 13, 2025

What I’m Reading

What I’m ReadingRecognition and alienation in the work of Isabella Hammad by Mary Turfah in Bookforum

AS NEWS BROKE that a ceasefire agreement—tenuous, immediately delayed by Israel—had been signed, celebrations filled Gaza’s streets. People allowed themselves to take in this victory: the naked force of the entire West had failed, for over a year, to break their will. When news of the ceasefire reached me, via phone notification, I started crying. But where I’d anticipated feeling some sense of closure, I felt instead like I was finally allowing myself to look through a door that I’d left open. During the acute phase of the genocide, there were questions many of us hadn’t allowed ourselves to ask. Among the heaviest: What will happen to these children? A small boy with dark circles under his eyes was asked recently what he would do on the first day of the ceasefire. “I want to go to [see] my mom,” he answered. “My mom died—I want to visit her grave and read al-fatiha [a prayer] for her.”

Remembering Canadian artist Kelly Mark, the 'working-class conceptualist' by Dave Dyment

It's rare that an artist's work can be summarized in a few words, and rarer still when that artist is prolific in a wide variety of media. Toronto artist Kelly Mark produced sculptures, drawings, photographs, audio, video, performance, text work, tattoos, mail art and multiples, about a myriad of subject matter.

I'm not sure who originated the term "working-class conceptualist" to describe her and her practice, but it was apt enough to follow her throughout her career, and astute enough to withstand scrutiny.

I always understood it to refer to the fact that the work is smart without being smug, funny without being trite, and completely absent of pretence or academic trappings. She brilliantly conflated the repetition of the minimalist and process-based work championed by the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design — where she studied — with the repetitive tasks of so much manual labour.

Deborah Dundas interviews Omar El Akkad in The Toronto Star

Omar El Akkad: Because I think courage is contagious, and I think there are many battlefields in which the state or the institution or ... institutional power hold immense advantage, the arena of violence being one. But there are ones in which human beings in solidarity with one another hold immense advantages, ones that the state or the institution cannot mimic: joy, love, compassion.

spoke with 20 people in Gaza after the ceasefire

Mohammed R MhawishSnapshots: I spoke with 20 people in Gaza after the ceasefire. My heart broke 20 timesIn the weeks following the ceasefire, I spoke with twenty people in Gaza—mothers, fathers, children, and grandparents—to hear about their first moments, days, and weeks after the bombs stopped. Their stories are not just about survival. They are about loss: of homes, of loved ones, of dreams, of the rhythms of everyday life…Read morea month ago · 352 likes · 37 comments · Mohammed R. Mhawish

Mohammed R MhawishSnapshots: I spoke with 20 people in Gaza after the ceasefire. My heart broke 20 timesIn the weeks following the ceasefire, I spoke with twenty people in Gaza—mothers, fathers, children, and grandparents—to hear about their first moments, days, and weeks after the bombs stopped. Their stories are not just about survival. They are about loss: of homes, of loved ones, of dreams, of the rhythms of everyday life…Read morea month ago · 352 likes · 37 comments · Mohammed R. MhawishA reading list to process the state of the world from

Mother, Loosen My TongueA reading list to process the state of the world“We are never as steeped in history as when we pretend not to be, but if we stop pretending we may gain in understanding what we lose in false innocence. Naiveté is often an excuse for those who exercise power. For those upon whom that power is exercised, naiveté is always a mistake…Read more2 months ago · 982 likes · 18 comments · Huda Hassan

Mother, Loosen My TongueA reading list to process the state of the world“We are never as steeped in history as when we pretend not to be, but if we stop pretending we may gain in understanding what we lose in false innocence. Naiveté is often an excuse for those who exercise power. For those upon whom that power is exercised, naiveté is always a mistake…Read more2 months ago · 982 likes · 18 comments · Huda HassanI just discovered an food and culture magazine and incorporates culture and politics.

At Vittles, we think about food as economy, class, inheritance, and political agency, rather than just a dish on a table. We publish essays about all aspects of food culture, from deep dives to polemics, from personal essays to reported journalism, as well as restaurant recommendations, recipes, and reviews.

Vittles Starving PalestineGood morning and welcome to Vittles. In today’s newsletter, Manal Shqair writes about how Israel’s colonial systems of land-grabbing, industrial agriculture and surveillance affect nomadic-pastoralist communities in Masafer Yatta in southern Palestine…Read morea month ago · 119 likes · 6 comments

Vittles Starving PalestineGood morning and welcome to Vittles. In today’s newsletter, Manal Shqair writes about how Israel’s colonial systems of land-grabbing, industrial agriculture and surveillance affect nomadic-pastoralist communities in Masafer Yatta in southern Palestine…Read morea month ago · 119 likes · 6 commentsBeware the man whose handwriting sways like a reed in the wind Anne Carson in the London Review of Books

This is an essay about hands and handwriting. I think of handwriting as a way to organise thought into shapes. I like shapes. I like organising them. But because of recent neurological changes in my brain I find shapes fall apart on me. My responsibility to forms can’t be gracefully fulfilled. Nonetheless, I offer the following in the hope it does not strike you as dishevelled or depressing.

Come as You Are: Remembering Joe Brainard in letters to friends, lovers, and fans by Andrew Chan in Bookforum

EVEN A CURSORY GLANCE at the life of Joe Brainard reveals him to have been something of a genius of friendship. Since the artist and writer died of AIDS-induced pneumonia in 1994 at the age of fifty-three, his legacy has been steadfastly tended to by a band of his contemporaries, who jump at the chance to rhapsodize at length not just about the man’s achievements but also his gentleness and unpretentiousness. Foremost among these evangelists is the poet Ron Padgett, whose close bond with Brainard began when the two were high school classmates in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in the 1950s. In the past two decades, Padgett has published the unabashedly affectionate memoir Joe, edited an authoritative anthology of Brainard’s writing, and served as the narrator of a short film about his friend, directed by the documentarian Matt Wolf. It’s easy to understand the urge to advocate for Brainard’s place in history. A staunchly idiosyncratic devotee of small-scale work, he was well-reviewed during his lifetime without ever becoming a brand name in the art world, partly due to his lack of skill and interest in the business side of his profession. One imagines that, by posthumously shepherding him into the spotlight, his friends are trying to reconcile a long-held desire to see him succeed with their respect for his humility.

offers advice on how to write while deeply distracted.

SubMakkHow to Write While Deeply Distracted I’m not saying I’m concentrating well right now—that would be psychotic. But I’m never focusing well, and over a lifetime of first masking and then, more recently, dealing with ADHD head-on, I’ve developed enough coping strategies that I can actually get stuff done. Including writing…Read more25 days ago · 218 likes · 18 comments · Rebecca Makkai

SubMakkHow to Write While Deeply Distracted I’m not saying I’m concentrating well right now—that would be psychotic. But I’m never focusing well, and over a lifetime of first masking and then, more recently, dealing with ADHD head-on, I’ve developed enough coping strategies that I can actually get stuff done. Including writing…Read more25 days ago · 218 likes · 18 comments · Rebecca Makkai“Deer Crossing ” by Amber Nuyens in Moss

When the couple drowned after running their car into the lake just after graduation, Jamie’s dad told her that if she ever ended up in the water like that, the first thing to do was to roll down her window. This was the second piece of driving advice from her dad she remembered. The first was that if an animal jumped in front of her on the road, she should accelerate so that the animal might fly over the car instead of going through her windshield. This would also probably kill it instantly and she wouldn’t leave it suffering or have to put it down herself. Don’t swerve, he told her. You’ll hit a tree or drive into oncoming traffic and then everyone but the animal is dead.

interviews in

Women WritingFeatured Writer: Sonal Champsee Welcome to Women Writing…Read more7 days ago · 12 likes · 4 comments · Liisa Kovala

Women WritingFeatured Writer: Sonal Champsee Welcome to Women Writing…Read more7 days ago · 12 likes · 4 comments · Liisa Kovalaon How to Sell a Story

Writing for People Who Hate WritingHow to Sell a StoryThe world is full of journalism schools and writing advice, but there’s surprisingly little formal guidance out there about how to get your non-fiction articles published. That’s a surprise. At many outlets where I’ve worked, about half of the stories were assigned by editors to staff or freelance contributors, while the other half were proposed by writ…Read more5 days ago · 4 likes · 2 comments · Jessica Johnson

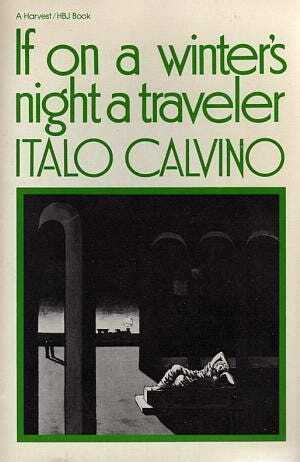

Writing for People Who Hate WritingHow to Sell a StoryThe world is full of journalism schools and writing advice, but there’s surprisingly little formal guidance out there about how to get your non-fiction articles published. That’s a surprise. At many outlets where I’ve worked, about half of the stories were assigned by editors to staff or freelance contributors, while the other half were proposed by writ…Read more5 days ago · 4 likes · 2 comments · Jessica JohnsonI’m also reading If on a winter’s night a traveler by Italo Calvino and enjoying it immensely—not just for its innovative structure but really blown away by Calvino’s gift for description. This book is all hook!

“The world is falling apart and trying to lure me into it’s disintegration.”

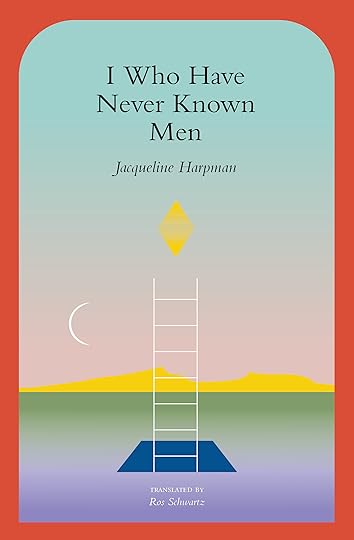

Just finished I Who Have Never Known Men by Jacqueline Harpman. This book seems to be making the rounds again. I kept hearing about it and then finally it came up in my library app.

This is an eerie and relevant book.

“Perhaps you never have time when you are alone? You only acquire it by watching it go by in others, and since all the women have died, it only affects the scrawny plants growing between the stones and producing, occasionally, just enough flowers to make a single seed which will fall a little way off—not far because the wind is never strong—where it may or may not germinate. The alternation of day and night is merely a physical phenomenon, time is a question of being human and, frankly, how could I consider myself a human being, I who have only known thirty-nine people and all of them women? I think that time must have something to do with the duration of pregnancies, the growth of children, all those things that I haven’t experienced. If someone spoke to me, there would be time, the beginning and end of what they said to me, the moment when I answered, their response. The briefest conversation creates time. Perhaps I have tried to create time through writing these pages. I begin, I fill them with words, I pile them up, and I still don’t exist because nobody is reading them. I am writing them for some unknown reader who will probably never come—I am not even sure that humanity has survived that mysterious event that governed my life. But if that person comes, they will read them and I will have a time in their mind. They will have my thoughts in them. The reader and I thus mingled will constitute something living, that will not be me, because I will be dead, and will not be that person as they were before reading, because my story, added to their mind, will then become part of their thinking. I will only be truly dead if nobody ever comes, if the centuries, then the millennia go by for so long that this planet, which I no longer believe is Earth, no longer exists. As long as the sheets of paper covered in my handwriting lie on this table, I can become a reality in someone’s mind. Then everything will be obliterated, the suns will burn out and I will disappear like the universe.”

I blurbed A Song for Wildcats by Caitlyn Galway and will be doing an interview with her soon. This is an outstanding story collection. Highly recommend.

What I’m WatchingThey Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969)This is a deeply strange and disturbing film. Jane Fonda’s acting is incredible. Relevant story for these terrible times. This is a movie for those who like their bleak very bleak.

Jeffrey Sachs: “The US is leading us closer to nuclear war.”

A terrifying interview. Where we are now was planted many many years ago.

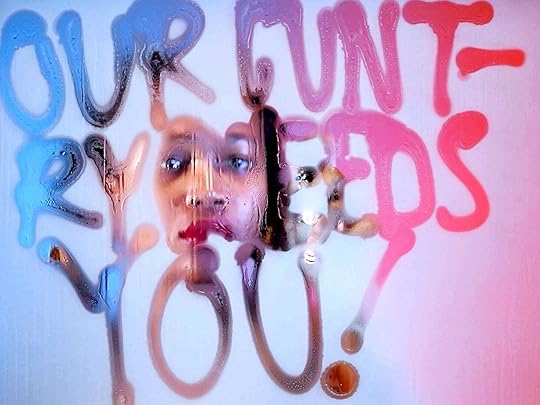

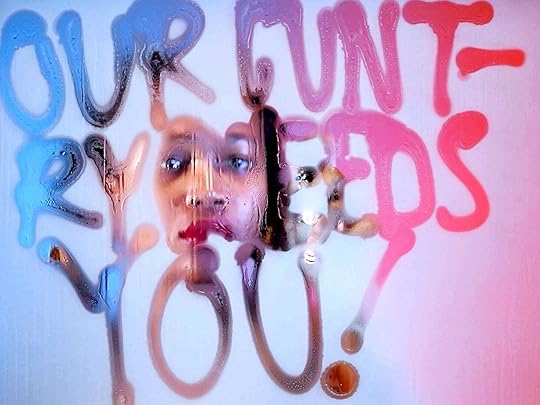

2 into 1 by Gillian WearingMy Cuntry Tis of Thee (2018) by Marilyn Minter HD Digital Video, 09:45 minutesWriting and Making, Writing as Making - Hannah BlackMy Bodies by Hannah BlackSaute ma ville (1968) by Chantal Ackerman

HD Digital Video, 09:45 minutesWriting and Making, Writing as Making - Hannah BlackMy Bodies by Hannah BlackSaute ma ville (1968) by Chantal AckermanFrom Criterion

For My Aching BackFrom the Archives

Directed by Chantal Akerman • 1968 • Belgium

Made when the director was just eighteen, Chantal Akerman’s debut film is a blistering first expression of what would become one of her major themes: women’s confinement in and rebellion against the domestic sphere. Akerman plays a young woman who, alone in her kitchen, enacts a savaging of traditional domestic rituals that leads to a literally explosive climax.

Gatherings | March 2025

Send My Love to Anyone supports small and independent presses and author’s whose writing intersects human rights, collective liberation, anti-oppression, and the climate crisis.

SMLTA pays for original unpublished writing.

Consider signing up for a paid subscription to support this project!

What’s in Gatherings Issue 44My NewsMy video Do You Know What’s Great adapted from a story in my short fiction collection Anecdotes will be screening online at the Reel Poetry International Festival.

Screening: Wednesday, April 2, 2025 at 1:00 - 1:30 p.m. CST and 7:00-7:30 p.m. CST

Kirby News

Kirby NewsKirby will be having the grand good fortune to read in support of Jessica Hiemstra's new book Book Root (Goose Lane Editions) along with fellow poet Shannon Bramer at the palace of poetry, The Printed Word, Dundas, ON, March 20th 7pm.

Kirby, will be live on April 17 at 7:00pm (EST) chatting with from Junction Reads!

Events

Events’ Wild Prose Readings Presents Soundin’ Canaan: Black Canadian Poetry, Music, and Citizenship with Paul db Watkins and Wayde Compton on March 13, 2025

What I’m Reading

What I’m ReadingRemembering Canadian artist Kelly Mark, the 'working-class conceptualist' by Dave Dyment

It's rare that an artist's work can be summarized in a few words, and rarer still when that artist is prolific in a wide variety of media. Toronto artist Kelly Mark produced sculptures, drawings, photographs, audio, video, performance, text work, tattoos, mail art and multiples, about a myriad of subject matter.

I'm not sure who originated the term "working-class conceptualist" to describe her and her practice, but it was apt enough to follow her throughout her career, and astute enough to withstand scrutiny.

I always understood it to refer to the fact that the work is smart without being smug, funny without being trite, and completely absent of pretence or academic trappings. She brilliantly conflated the repetition of the minimalist and process-based work championed by the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design — where she studied — with the repetitive tasks of so much manual labour.

Deborah Dundas interviews Omar El Akkad in The Toronto Star

Omar El Akkad: Because I think courage is contagious, and I think there are many battlefields in which the state or the institution or ... institutional power hold immense advantage, the arena of violence being one. But there are ones in which human beings in solidarity with one another hold immense advantages, ones that the state or the institution cannot mimic: joy, love, compassion.

spoke with 20 people in Gaza after the ceasefire

Mohammed R MhawishSnapshots: I spoke with 20 people in Gaza after the ceasefire. My heart broke 20 timesIn the weeks following the ceasefire, I spoke with twenty people in Gaza—mothers, fathers, children, and grandparents—to hear about their first moments, days, and weeks after the bombs stopped. Their stories are not just about survival. They are about loss: of homes, of loved ones, of dreams, of the rhythms of everyday life…Read morea month ago · 352 likes · 37 comments · Mohammed R. Mhawish

Mohammed R MhawishSnapshots: I spoke with 20 people in Gaza after the ceasefire. My heart broke 20 timesIn the weeks following the ceasefire, I spoke with twenty people in Gaza—mothers, fathers, children, and grandparents—to hear about their first moments, days, and weeks after the bombs stopped. Their stories are not just about survival. They are about loss: of homes, of loved ones, of dreams, of the rhythms of everyday life…Read morea month ago · 352 likes · 37 comments · Mohammed R. MhawishA reading list to process the state of the world from

Mother, Loosen My TongueA reading list to process the state of the world“We are never as steeped in history as when we pretend not to be, but if we stop pretending we may gain in understanding what we lose in false innocence. Naiveté is often an excuse for those who exercise power. For those upon whom that power is exercised, naiveté is always a mistake…Read morea month ago · 982 likes · 18 comments · Huda Hassan

Mother, Loosen My TongueA reading list to process the state of the world“We are never as steeped in history as when we pretend not to be, but if we stop pretending we may gain in understanding what we lose in false innocence. Naiveté is often an excuse for those who exercise power. For those upon whom that power is exercised, naiveté is always a mistake…Read morea month ago · 982 likes · 18 comments · Huda Hassanoffers advice on how to write while deeply distracted.

SubMakkHow to Write While Deeply Distracted I’m not saying I’m concentrating well right now—that would be psychotic. But I’m never focusing well, and over a lifetime of first masking and then, more recently, dealing with ADHD head-on, I’ve developed enough coping strategies that I can actually get stuff done. Including writing…Read more22 days ago · 218 likes · 18 comments · Rebecca Makkai

SubMakkHow to Write While Deeply Distracted I’m not saying I’m concentrating well right now—that would be psychotic. But I’m never focusing well, and over a lifetime of first masking and then, more recently, dealing with ADHD head-on, I’ve developed enough coping strategies that I can actually get stuff done. Including writing…Read more22 days ago · 218 likes · 18 comments · Rebecca Makkai“Deer Crossing ” by Amber Nuyens in Moss

When the couple drowned after running their car into the lake just after graduation, Jamie’s dad told her that if she ever ended up in the water like that, the first thing to do was to roll down her window. This was the second piece of driving advice from her dad she remembered. The first was that if an animal jumped in front of her on the road, she should accelerate so that the animal might fly over the car instead of going through her windshield. This would also probably kill it instantly and she wouldn’t leave it suffering or have to put it down herself. Don’t swerve, he told her. You’ll hit a tree or drive into oncoming traffic and then everyone but the animal is dead.

interviews in

Women WritingFeatured Writer: Sonal Champsee Welcome to Women Writing…Read more3 days ago · 12 likes · 4 comments · Liisa Kovala

Women WritingFeatured Writer: Sonal Champsee Welcome to Women Writing…Read more3 days ago · 12 likes · 4 comments · Liisa Kovalaon How to Sell a Story

Writing for People Who Hate WritingHow to Sell a StoryThe world is full of journalism schools and writing advice, but there’s surprisingly little formal guidance out there about how to get your non-fiction articles published. That’s a surprise. At many outlets where I’ve worked, about half of the stories were assigned by editors to staff or freelance contributors, while the other half were proposed by writ…Read more19 hours ago · 4 likes · 2 comments · Jessica Johnson

Writing for People Who Hate WritingHow to Sell a StoryThe world is full of journalism schools and writing advice, but there’s surprisingly little formal guidance out there about how to get your non-fiction articles published. That’s a surprise. At many outlets where I’ve worked, about half of the stories were assigned by editors to staff or freelance contributors, while the other half were proposed by writ…Read more19 hours ago · 4 likes · 2 comments · Jessica JohnsonI’m also reading If on a winter’s night a traveler by Italo Calvino and enjoying it immensely—not just for its innovative structure but really blown away by Calvino’s gift for description. This book is all hook!

“The world is falling apart and trying to lure me into it’s disintegration.”

Just finished I Who Have Never Known Men by Jacqueline Harpman. This book seems to be making the rounds again. I kept hearing about it and then finally it came up in my library app.

This is an eerie and relevant book.

“Perhaps you never have time when you are alone? You only acquire it by watching it go by in others, and since all the women have died, it only affects the scrawny plants growing between the stones and producing, occasionally, just enough flowers to make a single seed which will fall a little way off—not far because the wind is never strong—where it may or may not germinate. The alternation of day and night is merely a physical phenomenon, time is a question of being human and, frankly, how could I consider myself a human being, I who have only known thirty-nine people and all of them women? I think that time must have something to do with the duration of pregnancies, the growth of children, all those things that I haven’t experienced. If someone spoke to me, there would be time, the beginning and end of what they said to me, the moment when I answered, their response. The briefest conversation creates time. Perhaps I have tried to create time through writing these pages. I begin, I fill them with words, I pile them up, and I still don’t exist because nobody is reading them. I am writing them for some unknown reader who will probably never come—I am not even sure that humanity has survived that mysterious event that governed my life. But if that person comes, they will read them and I will have a time in their mind. They will have my thoughts in them. The reader and I thus mingled will constitute something living, that will not be me, because I will be dead, and will not be that person as they were before reading, because my story, added to their mind, will then become part of their thinking. I will only be truly dead if nobody ever comes, if the centuries, then the millennia go by for so long that this planet, which I no longer believe is Earth, no longer exists. As long as the sheets of paper covered in my handwriting lie on this table, I can become a reality in someone’s mind. Then everything will be obliterated, the suns will burn out and I will disappear like the universe.”

I blurbed A Song for Wildcats by Caitlyn Galway and will be doing an interview with her soon. This is an outstanding story collection. Highly recommend.

What I’m WatchingThey Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969)This is a deeply strange and disturbing film. Jane Fonda’s acting is incredible. Relevant story for these terrible times. This is a movie for those who like their bleak very bleak.

Jeffrey Sachs: “The US is leading us closer to nuclear war.”

A terrifying interview. Where we are now was planted many many years ago.

2 into 1 by Gillian WearingMy Cuntry Tis of Thee (2018) by Marilyn Minter HD Digital Video, 09:45 minutesWriting and Making, Writing as Making - Hannah BlackMy Bodies by Hannah BlackSaute ma ville (1968) by Chantal Ackerman

HD Digital Video, 09:45 minutesWriting and Making, Writing as Making - Hannah BlackMy Bodies by Hannah BlackSaute ma ville (1968) by Chantal AckermanFrom Criterion

For My Aching BackFrom the Archives

Directed by Chantal Akerman • 1968 • Belgium

Made when the director was just eighteen, Chantal Akerman’s debut film is a blistering first expression of what would become one of her major themes: women’s confinement in and rebellion against the domestic sphere. Akerman plays a young woman who, alone in her kitchen, enacts a savaging of traditional domestic rituals that leads to a literally explosive climax.

March 2, 2025

I am writing this because I want you to understand my world, the world I live in, and the world I live alongside.

It is a secure place, both in the sense that it is indestructible and in the sense that it is safe for the most vulnerable.

– Rowan Williams

One day, as I was starting to write this book, I was leaving the church where I work when an angry woman stopped me, after throwing a bag of garbage into the encampment in our yard, and told me that a person had started sleeping in her yard, and that I needed to tell her how she could find out who it was and make him go away. I suggested that she ask the person himself who he was.

She stared at me as if I had suggested that she fly to the moon for information, and exclaimed, ‘But he takes drugs!’

‘You can still ask him who he is,’ I said.

And she stormed away up the street.

I tell this story not primarily to illustrate how I have come to be seen as responsible for all homeless people within about an eight-block radius of the church, although that is, for some reason, true. I tell it because there is a great gulf fixed, and very few people are willing to cross it. People who have not lived in the world of which encampments are part are afraid, and they are angry. And they cannot imagine that there is a way to cross that line, to speak to a homeless person as a fellow human being, without somehow themselves being harmed, being damaged, being touched by a world they would rather deny. A kinder, more well-intentioned, neighbour once told me he didn’t want to introduce himself to encampment residents, because if they knew he lived nearby, they might knock on his door all the time asking for help. It seems like a reasonable fear, and it is hard to explain that unhoused people have such deep and well-founded apprehensions about the housed world that, even when they are living against the wall of the church, and even when they know we are an institution that is here to support them, it is almost always my job to go out the door and identify need.

I am writing this because I want you to understand my world, the world I live in, and the world I live alongside. I have been an Anglican priest since 2012; I have been the priest at St. Stephen-in-the-Fields, in Kensington Market in Toronto, since 2013. We have had, I guess somewhat famously, an encampment in our churchyard since about the spring of 2022, although there was no single clear point when it began, and it is tied up with events and choices going back for years, and is perhaps ultimately the responsibility of the poet and theologian Rowan Williams, who was once the Archbishop of Canterbury. I am writing this because I want you to understand that this is a world of real people, who struggle and are kind, who are often special and beautiful in ways that most of our society cannot and does not try to understand. I want you to understand that I have felt safer here than in most other places, hard as it has sometimes been.

It is a different world, and why I am easy with this world is hard to pin down. Because it is honest, and most people are not honest. Because I have waged my own lifelong battles with depression, anxiety, OCD, probably undiagnosed autism, and because I was viciously bullied through my whole school career and took on board the clear message that the normal world didn’t want me, and I decided fairly early on that I didn’t want them either. Because my parents taught drama and creative writing in the prisons, and there were social dynamics I met as a child that most middle-class people learn in training workshops as adults, if they learn them at all. Because at one point in my twenties, I looked at a man panhandling at Bloor and Bathurst, and thought that I needed to take completely seriously the proposition that he was Jesus. Because my autistic daughter has spent most of her twenty-eight years being expelled from program after program. Because I don’t dress very well, and my hair isn’t very good, and I look more like I belong in the world of the encampment than in the world of the others. Because people on the street, exhausting as they can often be, have also been kind to me, and to my daughter, more consistently than almost anyone else. Because there are reasons I probably don’t even know.

And I am writing this because I do not have much optimism about what is coming in our society, in our world. We are standing at the edge of catastrophic climate breakdown and the fall of a long empire, and all the collateral damage which the fall of an empire brings. Nothing stable is going to last; and the only way that we, the small and the ordinary, might survive in any decent way is if we learn to take care of each other, to do it deeply and consistently and in ways that will change how we think and how we live. This is one story, flawed and incomplete, of people who have been trying to look after each other in very hard times, and some of the ways in which we have been changed.

And I am writing this because if you want to know who someone is, you can ask them.

Thanks for reading Send My Love to Anyone! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Maggie Helwig (she/they) is a white settler in Tkaronto/Toronto, and is the author of fifteen books and chapbooks, most recently Girls Fall Down (Coach House, 2008), which was shortlisted for the Toronto Book Award, and was chosen as the One Book Toronto in 2012. Helwig is a long-time social justice activist, and also an Anglican priest, and has been the rector of the Church of St Stephen-in-the-Fields since 2013. Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published

Encampment: Resistance, Grace, and an Unhoused Community

by Maggie HelwigCoach House Books, 2025Support Send My Love to Anyone

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published

Encampment: Resistance, Grace, and an Unhoused Community

by Maggie HelwigCoach House Books, 2025Support Send My Love to AnyoneSupport Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

February 28, 2025

Introduce yourself in the comments and tell us what you’re working on or share something you’ve recently published.

Hello SMLTA Community!

I’m starting a space on Send My Love to Anyone where paid subscribers can share links to their work, boost each other’s notes, posts, and books, offer writing and publishing tips, share calls and opportunities, and support and encourage each other.

I’ve been wanting to add a new perk for awhile. As writers we need space to share and support each other especially now that social media is becoming more and more fragmented.

In recent months, I’ve had some good experiences on Substack meeting new literary writers and seeing how powerful uplifting and sharing each other’s work can be.

This is a place to share and receive support on your news, to share your notes that you want more traction on, to ask question and offer tips and advice.

Please introduce yourself in the comments and tell us what you’re working on or share something you’ve recently published.

So I’m thinking about literary citizenship and its vicissitudes; that is, how paying dues is both necessary and fraught.

Maybe you’re like me; for decades I have remembered to pay my literary dues. To read, to review, to mentor, to teach, to praise the work of others with a glad heart, all while writing, re-writing, learning and unlearning bad habits, fostering better habits, thinking well and less well, and generally not worrying about making an impact on the literary scene because any opinion that an impact has been made is always the decision of other people. Like many of us, while waiting for eyes on my work, I just due it.

And I’m not always – let me extend that to not often – read.

So I’m thinking about literary citizenship and its vicissitudes; that is, how paying dues is both necessary and fraught. I’m also thinking about genre fluidity, and how all these energies work together.

*

At literary events, after I have read my work aloud and talked about writing, I usually move through the crowd searching for a breath of air or a snack. This is when people stop me and say something like this: “That was great! I’ve never heard of you or your book!” The first times this happened, I thought nothing of it. Of course I was obscure – I was just starting. But after four, five, six books, such exclamations began to get old. It’s a curious moment, in which I know someone is expressing their excitement to have “discovered” me but what a backhand. I appreciate it when someone sticks to the first comment and swallows the second before it leaves their mouth. I know, I know: no one knows me.

That last is an overstatement, of course; people know me, and someone’s reading me right now. (Hello!) And though admitting to a small readership is taboo, I’m tired of pretending.

There are all kinds of essays about writing I could cite that would, and have, wagged their proverbial fingers at me as they say that we don’t write in order to be read, but all of those essays are written by writers who I read, defeating the purpose of Milosz or Heaney or Ruefle arguing for their own obscurity amid their international fame, which I know is not rock-star fame, but still, ironic.

A book should be an axe for the frozen sea within us, wrote Kafka. But he also told Max Brod to destroy all his manuscripts after he died, which Brod did not do, which is why I can quote Kafka today on loneliness and isolation and literature and why you probably recognize that quotation. If Kafka continued to be as unknown as he was the week he died, then no one would be quoting him on his obscurity, his loneliness, his inner ice.

I could write about literary isolation, but if I did, how would you find it?

*

Maybe it’s because I don’t write fiction.

I also take long breaks from reading fiction, and I often think I’m breaking up with it. I have large and bruised doubts about what it is supposed to do: not the good doubts, the kind that make my thoughts shoot off into the stratosphere. This is doubt that spreads like fog through my brain, seeps under doorways, makes me wonder if there’s smoke in the house.

But then I read some poetry or nonfiction – or even better, some hybrid forms – and the fog lifts, gets sucked back outside, whiffles under the door and backs away down the block, and I stand for a long time in that watery and transformative space between poetry and essay, using poetry to draw out what is hard about an essay, and using the essay to find different congruencies of the lyric moment, to strengthen, to beautify, to shout, to nudge.

It’s rising on its banks, that riverine surge between poetry and essay. For years I wrote essays about poetry – let me be clear, other people’s excellent poetry – and I liked doing that except the more I sat by the river, the less time I had to wade into that moving water, to feel it eddy around my ankles and shins as I step in and step out of the current, sometimes cold, sometimes muddy, often happy.

Same river, many chances. Time passes and life allows me or she does not; the river has sometimes been dammed and often diverted.

Poessay or essem: stones in the river, sometimes slippery, sometimes secure, places for my feet in the cooling waters. I always have hot feet and the centre of a path of running water (creek, stream, river) is my best place on the planet.

The river altered by a foot’s insertion into its wide and capacious current is a Heraclitean proposition that I can’t ignore, though I know that it’s most often Plato quoted on Heraclitus, and not Heraclitus himself. I’m no scholar of Greek, but that one-philosopher-removed business seems like a big foot in a river. In Canada, all kinds of bigger things disrupt rivers: hydro dams and sewage and violence. But droughts and floods are as nothing to the river, despite the human cost. No one should take history lightly, but we might wear our search for presentness with grace and compassion, like it is a scarf to warm us and not a boulder we push uphill. As Haudenosaunee scholar Richard Monture says in his book of the same name, “we share our matters”.

To share my matters, and ask after the matters of others, I come back to my river practice, back to hybridity and the shape of unreadness in a long arc of isolation, practice, and community.

*

I know writers who write bestsellers. I sit next to them at events. There is always a moment – at a bookstore or festival – when my signing line finishes. Ten or twelve folks chat with me and get their books signed and sometimes walk away with my card so they can email me something later, and the line for the other author remains long and serpentine: readers holding stacks of books in their arms, willing to wait and wait.

I can’t say envy doesn’t enter into it – of course it does – but whenever I see this, envy isn’t my primary feeling. Mostly I feel a bit stupid for all the times I thought, “It’s okay – I am just paying my dues. My Big Book is coming.”

But the Big Book is not coming. And I’m starting to think that this is okay.

The idea of literati is a literatease.

This truth swims towards me, brushing its iridescent sides against my cold, wet, river-loving feet.

*

We seem to be giving up on defining the prose-poem and postcard story against each other, or maybe it’s only that no one’s talking about it around me any longer, and if that’s so, thank you for taking that rut-making exchange elsewhere. I was never going to get in harness and pull your car out of that snowbank.

I love genre and teach it all the time, mainly so that genre-defiers (like me, like you) can know enough about genre to defy, blend, smush, suture, spindle, and fold like they’re made of it.

Poessay sounds like poésie, but they are not the same. Essem sounds like a sneeze.

Those poessays, those essems, are lyric and ludic, rhetorical in scope but not in shape; they rehearse undoing so that they can traffic in narrative but spin it fine as fishing line. This is not news, but in my isolation and obscurity, I stand in the river, feeling my leg hair waving in the current, let my wet knees and icy feet dictate the next moments.

*

A handful of bad years seemed as though they might have the force to build a wall between me and the flow of words to which I have had an unlimited springy access since I learned to read. Even with the patriarchy and my poor education followed by my good education and the life-long task of telling the difference between them, my chosen misdirections and not meeting a writing role model until I was in my thirties, encountering instead full-on way-too-proud-of-it misogyny and classism and violence, I wrote and wrote and wrote and wrote. It was the thing I couldn’t lose.

That writing wasn’t always good, and it wasn’t always published.

It’s important to admit to being wrong or having half-baked ideas sometimes, because vulnerability to misapprehension or the occasional persuasion of bad people is very human. It’s a relief to recall long periods of time when I didn’t write for readers because I couldn’t picture any. For many years, it was just me and the words.

I chafe against admonishments that we shouldn’t write with the hope, or desire, of being read. Those admonishments will not bring eyes to your page in any case. I have done my time as unread as any teenage diarist, as any memoirist with a story but no method, as any emo-angsty poet, and I can tell you that the philosophy of the unread is not to give up your desire; it’s to re-direct it. Please yourself.

If writing to please the self is masturbation, then writing to please others is either sacrificial selflessness or egotism, and I don’t think I’m interested enough to parse the shapes of these.

In the classroom and the literary world, I am (like everyone else) routinely vulnerable to all kinds of bullshit, human and computer-generated. But I’m also subject to plenty of good, and there’s no ignoring the correlative between low expectations and high satisfaction.

I wade over to a different part of the river. The hem of my dress is now pleasingly waterlogged and will slap, limp but propulsive, against my legs on the walk home.

I gave a reading a few years ago at a small bookstore and an even smaller audience showed up. Since I wasn’t from that city and the store was laissez-faire about advertising – meaning that they did none – I felt sanguine about the headcount. That tiny audience in that barely advertised event in that cold-shoulder bookstore turned out to be the best, because all of us scheduled to read that night undid our writerly personae and read our favourite poems – the strange ones, the long ones, the ones that didn’t fit our books’ arcs or advertising copy or the set we usually did. I let myself listen the way I couldn’t have or wouldn’t have if the venue had been bigger. When I was my turn, I read five of the least sympathetic poems in my book, ones I couldn’t fully explain and didn’t try to: poems that needed extreme listening. I saw a smile the size of a city block spread across one of the listener’s faces. This was my final event of six months of promotion, during which I had read in bookstores and pubs, large theatres and university classrooms, hotel meeting rooms and cafes, and I felt like finally, finally, I could hear myself.

Please yourself.

I’m no longer a young writer who plans what she wears to readings, whom men and women hit on sometimes nicely and sometimes aggressively. I pretty much show up in jeans and a sweater with my middle-aged hips and belly and exactly no one macks on me.

That is not regret; it is puzzlement, for I have grown more and more interesting. I would mack on me.

*

Instead of “No man steps into the same river twice, for it is not the same river and he is not the same man,” I prefer this Heraclitean river statement, which I gleaned from The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and can’t stop thinking about: “Into the same rivers we step and do not step, we are and are not.”

Poessayists know it’s true. We swear by our tranquil feet.

Tanis MacDonald (she/her) is the author of Straggle: Adventures in Walking While Female as well as six other books of poetry and nonfiction. She is twice the winner of the Open Seasons Award: once in 2021 for her essay of female friendship and music fandom, and again in 2025 for her forthcoming essay on adoption and ancestry. She has been longlisted for the CBC Poetry Prize and took an honourable mention in the Pavlick Poetry Prize in 2021. Tanis was raised in Treaty One territory and now lives as a grateful guest on Haldimand Treaty land, near the Grand River in southwestern Ontario, where she teaches in the Department of English and Film Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University. Her next book, Tall, Grass, Girl, is forthcoming with Book*hug Press. Little Qualicum River in B.C. | Photo credit: John RoscoeSupport Send My Love to Anyone

Little Qualicum River in B.C. | Photo credit: John RoscoeSupport Send My Love to AnyoneSupport Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

February 20, 2025

Poets, put your books in the hands of your neighbours' children!

Poets, put your books in the hands of neighbourhood children!

The first poetry book I ever owned was Upstairs Over the Ice Cream (Ergo, 1979) by Marianne Micros. I was ten-years-old, and she gave me my very own copy. She is not only a poet who happened to live on the street where I grew up in London, Ontario, but also she is the mother of my best friend Eleni Kapetanios. Eleni and I often tagged along with her to poetry readings at the London Public Library or at the Home County Folk Festival or at the parties she and her husband, Tim Struthers, hosted in London, Ontario in the early 1980s.

Upstairs Over the Ice Cream is a raw and moving portrait of Micros’ childhood growing up in Cuba, New York, the granddaughter of Greek immigrants who owned an ice cream factory. She vividly depicts her life in this small American town in the 1950s and the tragedy of her father and grandfather dying in the same summer. She writes, “ i wish i could think about trivia / stop being angry stop smelling death in every flower.”

Amidst the grief there’s humour—her grandmother upstairs feeding birds from the window while watching “a man in the yard below / defecate in the flower bushes” or Micros pulling a prank on one of the factory workers by locking him in a freezer. The man was so scared he crawled onto the conveyor belt. She writes:

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published good thing it wasn’t moving he would have been part of the next batch the flavour of the month mixed worker and that ain’t strawberryMicros includes a four-page found poem of her grandmother’s scrapbook which is composed of newspaper clippings:

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published Hitler’s list of countries to be conquered — Greece is next to last Hitler and Mussolini arm in arm HOW TO MAKE AN ATTRACTIVE WAR-BRIDE HOME OUT OF A DISMAL RENTED ROOM easy rice pudding 3,000 GATHER TO VIEW GIRL’S WEEPING STATUE — granddaughter graduates from Sweet Briar College, 1965She observes the harsh realities of the women in her family who after the death of their husbands and sons are “alone” and “unclassifiable” and how their choices even before these deaths were limited.

As a young woman her grandmother was taken from her small Greek village and “shipped off to America” to be married to a man she hardly knew. Her mother told her how she had to “show her bloody nightgown / after her wedding night / live with her in-laws have babies …”

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published she knew that a woman’s life is filled with babies and miscarriages babies and miscarriages following each other in quick succession and you have to mop up after yourselfMicros wants something different, and she gets it by going to college and travelling.

In the last poem, she is a college student visiting Sekea, her grandparents’ village in Greece. This is a village without electricity, where chickens roam free, and the people travel by donkey. Despite her initial shock, Micros soon becomes accustomed to life in Sekea where she is under the loving care of her extended relatives—her blind great-grandmother, her great aunts, uncles, and cousins. She learns songs and dances on the beach with a “bearded priest”. A man on a donkey proposes to her.

While she cherishes her time in Sekea, she’s also glad to return to the ice cream factory and her grandmother in Cuba, New York, whom she imagines standing in her “white kitchen cooking / with her electric frying pan” so she can tell her that she “has seen Sekea”.

Upstairs Over the Ice Cream is an intense journey through profound childhood loss, culminating in a discovery of family and self. This is a stunning collection of poems written with sharp, harrowing, and, at times, amusing observations.

I’m so grateful to Marianne Micros for giving me such a rich introduction to poetry with this book and allowing me to tag along to those poetry readings which let me see a world that I didn’t know at the time—would one day be my own.

Upstairs Over the Ice Cream can be purchased from Red Kite Press.

Marianne Micros's debut short story collection Eye was shortlisted for the 2019 Danuta Gleed Literary Award and for the 2019 Governor General's Award for English-language fiction. She is a retired professor of English at the University of Guelph, where she taught Renaissance literature, Scottish literature, folktales, and creative writing. She lives in Guelph, Ontario. Excerpt from Upstairs Over the Ice CreamText within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedthe undertakerhas cold, clammy handsas he greets you at the doorand leads you insidehe smileswith such sympathythis is his salonand he makes his guestscomfortablehe hangs up your coatand says: don’t forgetto sign the guest bookbefore you leaveand you breathea sigh of reliefhe’s going to let youget away this timehe even gives youa gifta ballpoint penwith the name of his establishmentprinted boldly on ithe hopesyou will come backsomedayPrinted with permission of the author.Support Send My Love to Anyone

Excerpt from Upstairs Over the Ice CreamText within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedthe undertakerhas cold, clammy handsas he greets you at the doorand leads you insidehe smileswith such sympathythis is his salonand he makes his guestscomfortablehe hangs up your coatand says: don’t forgetto sign the guest bookbefore you leaveand you breathea sigh of reliefhe’s going to let youget away this timehe even gives youa gifta ballpoint penwith the name of his establishmentprinted boldly on ithe hopesyou will come backsomedayPrinted with permission of the author.Support Send My Love to AnyoneSupport Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

A Song for Wildcats by Caitlyn Galway

“The horses watched as the cab passed, their black-smoke manes blowing over the bright swells of their eyes, their legs like brittle stems of clay. It was late October 1933, and the drought had swept its indiscriminate scythe across the once sun-honeyed fields.” —from “Wisps” in A Song for Wildcats by Caitlin Galway

I got to read an ARC of A Song for Wildcats.

The above quote is just one example of Caitlin Galway’s striking prose and fresh and original smile in these stories. Her characters are brilliant and larger than life but her steady hand with narrative and description is something to behold.

Here’s the blurb I wrote for the book:

A Song for Wildcats is a remarkable collection of five stories that move seamlessly through historical time periods and settings with a touch of the surreal.

Whether it’s ghosts in Northern Ireland during The Troubles or doppelgangers in 1980s Las Vegas, Caitlin Galway’s striking and elegant prose transports you into the rich inner worlds of her raw but fiery characters.

These urgent stories of desire, secrets, unconditional love, resistance, and survival are intimate, dreamlike, and profoundly affecting.

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published

A Song for Wildcats

by Caitlin GalwayDundurn Press, 2025

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published

A Song for Wildcats

by Caitlin GalwayDundurn Press, 2025

An arresting, vividly imaginative collection of stories capturing the complexity of intimacy and the depths of the unravelling mind.

Infatuation and violence grow between two girls in the enchanting wilderness of postwar Australia as they spin disturbing fantasies to escape their families. Two young men in the midst of the 1968 French student revolts navigate — and at times resist — the philosophical and emotional nature of love. An orphaned boy and his estranged aunt are thrown together on a quiet peninsula at the height of the Troubles in Ireland, where their deeply rooted fear attracts the attention of shape-shifting phantoms of war.

The five long-form stories in A Song for Wildcats are uncanny portraits of grief and resilience and are imbued with unique beauty, insight, and resonance from one of the country's most exciting authors.

Support Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

In my little life / I hope to hold /

some wonder

Thanks for reading Send My Love to Anyone! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Kevin Spenst has authored sixteen chapbooks plus an upcoming one with Anstruther Press, and four full-length books of poetry including the latest, A Bouquet Brought Back from Space (Anvil Press). He’s an organizer for the Dead Poets Reading Series, writes for subTerrain magazine, occasionally co-hosts Wax Poetic on Vancouver Co-op Radio, and teaches poetry at SFU’s The Writer’s Studio in Vancouver on unceded Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh territory.“Some Force at the Centre of Our Silence” and “A Prayer to the Dissenter” from A Bouquet Brought Back from Space (Anvil Press, 2024). Published with permission of Anvil Press. Copyright © 2025 Kevin Spenst Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published

A Bouquet Brought Back from Space

by Kevin SpenstAnvil Press, 2024

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published

A Bouquet Brought Back from Space

by Kevin SpenstAnvil Press, 2024In a secularized society, what kind of faith in our collective powers and imaginations can be patch-worked together, and what might be the role of angels? Through multiple locales, languages, and spiritualities, A Bouquet Brought Back from Space both subverts and sublimates traditions of religious poetry, love poetry, and song.

Playful in form and formed full of play, this fourth book of poetry by Kevin Spenst explores loss, love and faith through the palindrome, Madlib, Fibonacci, found poem, prose poem, sonnet and various strains of free verse. Spenst meditates on mental health, poetic friendships and influences, and the possibility of there being an angel assigned to the Mennonites at the beginning of their global journey.

These poems sing, cry, and soothe.

Support Send My Love to AnyoneSupport Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA