Nancy Bilyeau's Blog, page 21

July 7, 2015

Who Was the Real Mother Shipton?

In the spring of 1881, families across England deserted their homes, too distraught to sleep in their beds. They slept in fields or prayed in churches and chapels for God to spare their lives in the apocalypse that was foretold: "The world to an end shall come; in eighteen hundred and eighty one."

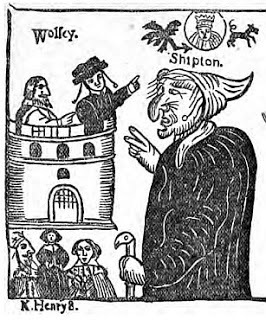

The author of their terror was Mother Shipton, also known as Ursula Shipton, a woman whose prophecies had been circulating through England and beyond for centuries. The first famous man whose life she prophesied was Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the minister to Henry VIII until 1530. In often cryptic verse, the crone-like seer predicted wars, rebellions and all matter of natural disasters. After London burned in 1666, Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary: "Mother Shipton's word is out." Her prophecies were published in one form or another over 20 times between 1641 and 1700. In the 1800s, her predictions grew even more terrifying: The end-of-the-world was foretold in a book published in 1862. Its other prophetic verse included: "A carriage without a horse shall go; Disaster fill the world with woe; In water iron then shall float; As easy as a wooden boat."

The author of their terror was Mother Shipton, also known as Ursula Shipton, a woman whose prophecies had been circulating through England and beyond for centuries. The first famous man whose life she prophesied was Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the minister to Henry VIII until 1530. In often cryptic verse, the crone-like seer predicted wars, rebellions and all matter of natural disasters. After London burned in 1666, Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary: "Mother Shipton's word is out." Her prophecies were published in one form or another over 20 times between 1641 and 1700. In the 1800s, her predictions grew even more terrifying: The end-of-the-world was foretold in a book published in 1862. Its other prophetic verse included: "A carriage without a horse shall go; Disaster fill the world with woe; In water iron then shall float; As easy as a wooden boat."The world did not end in 1881. People began sleeping in their beds once more. It was not the first time that fear of a Mother Shipton prediction convulsed a nation and it would not be the last.

Today there is considerable skepticism that a voluble prophetess named Mother Shipton ever existed. Many of her written predictions are, after all, confirmed forgeries, created to sell greater numbers of chapbooks and almanacs. Her 1684 "biographer" spun spooky details of her birth and existence; the 1881 end-of-the-world prophecy was debunked when the Victorian editor Charles Hindley publicly confessed to concocting the verses himself.

Entrance to Shipton CaveNonetheless, belief in Mother Shipton persisted. Today a thriving tourist attraction called Mother Shipton's Cave, at Knaresborough, North Yorkshire, features the cave where she was born and the petrifying well where objects can turn to stone. There's also a shop selling mugs, tea towels, thimbles, and wishing-well water in dark pink, ruby red and kelly green.

Entrance to Shipton CaveNonetheless, belief in Mother Shipton persisted. Today a thriving tourist attraction called Mother Shipton's Cave, at Knaresborough, North Yorkshire, features the cave where she was born and the petrifying well where objects can turn to stone. There's also a shop selling mugs, tea towels, thimbles, and wishing-well water in dark pink, ruby red and kelly green.But just because Mother Shipton has become the label on kelly- green wishing-well water does not mean that she has no basis in fact. Like Robin Hood or King Arthur, it's believed that if we were able to trace the myth-making back to the very beginning, a living, breathing person could be identified

There are no written references to Mother Shipton in the 1500s. That name does not appear in print until 1641. But a mention of a "witch of York" in a chilling letter written by King Henry VIII himself could be the elusive source of the legend.

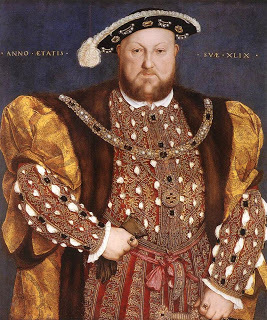

There are no written references to Mother Shipton in the 1500s. That name does not appear in print until 1641. But a mention of a "witch of York" in a chilling letter written by King Henry VIII himself could be the elusive source of the legend.The context of the letter is critical. It was written to Thomas Howard, duke of Norfolk, while the duke was in the middle of a clean-up operation following the Northern rebellion against the king known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. Thousands of commoners and a fair number of nobles rose up against the reforms in religion forced on the country by Henry VIII. The rebels were particularly aggrieved by the fresh taxes and the closing of the monasteries, which in the poorer regions of the North were needed sources of food, shelter, and medical care. The Duke of Norfolk had easily defeated this 1537 outbreak, which followed the main rebellion of 1536, and he was now imprisoning and then executing people without trial, imposing martial law. He wrote his king that he hanged more than 70.

A watercolor of the rebellion showing, somewhat inaccurately, that the army was led by priests and monksHenry VIII dictated the following letter to Norfolk in response:

A watercolor of the rebellion showing, somewhat inaccurately, that the army was led by priests and monksHenry VIII dictated the following letter to Norfolk in response:“We shall not forget your services, and are glad to hear also from sundry of our servants how you advance the truth, declaring the usurpation of the bishop of Rome… We approve of your proceedings in the displaying of our banner, which being now spread, till it is closed again the course of our laws must give place to martial law; and before you close it up again, you must cause such dreadful execution upon a good number of inhabitants, hanging them on trees, quartering them, and setting their heads and quarters in every town, as shall be a fearful warning, whereby shall ensue the preservation of a great multitude... You shall send up to us the traitors Bigod, the friar of Knareborough, Leche, if he may be taken, the vicar of Penrith and Towneley, late chancellor to the bishop of Carlise, who has been a great promoter of these rebellions, the witch of York and one Dr. Pykering, a canon. You are to see to the lands and goods of such as shall now be attainted, that we may have them in safety, to be given, if we be so disposed, to those who have truly served us..."

"The witch of York"...could this be a contemporary reference to a woman who not only caused enough trouble to incite the wrath of Henry VIII but also transformed into Mother Shipton? Her legend grew and grew in the 1600s, in published almanacs: Ursula was born in a cave in 1488, the child of an orphan servant girl and an unknown father--perhaps Lucifer himself. She was singularly ugly, called "Devils Bastard" and "Hag-face." Nonetheless, Ursula married a builder named Toby Shipton and lived quietly with him, never prosecuted for witchcraft though regularly uttering prophecy. "Her stature," wrote her biographer, "was larger than common, her body crooked, her face frightful; but her understanding extraordinary." How much of this describes the same "witch of York" cited by Henry VIII is unknown.

Cardinal Thomas WolseyThe fact that Mother Shipton's first known prediction concerned the fate of Cardinal Wolsey is significant. According to Wolsey's gentleman usher and later biographer, George Cavendish, Wolsey, near the end of his life, was disturbed by a prophecy heard. Cavendish wrote: " 'There is a saying, quoth he, 'that When this cow rideth the bull, then priest beware thy skull." According to Tudor-court interpretation, the cow was Anne Boleyn, who in her holding sway over Henry VIII and convincing him to divorce his queen to marry her, triggered the break with the Catholic Church. Mother Shipton was not attributed to this prophecy by Cavendish. But in the future, her soothsaying would intertwine with Wolsey's fate.

Cardinal Thomas WolseyThe fact that Mother Shipton's first known prediction concerned the fate of Cardinal Wolsey is significant. According to Wolsey's gentleman usher and later biographer, George Cavendish, Wolsey, near the end of his life, was disturbed by a prophecy heard. Cavendish wrote: " 'There is a saying, quoth he, 'that When this cow rideth the bull, then priest beware thy skull." According to Tudor-court interpretation, the cow was Anne Boleyn, who in her holding sway over Henry VIII and convincing him to divorce his queen to marry her, triggered the break with the Catholic Church. Mother Shipton was not attributed to this prophecy by Cavendish. But in the future, her soothsaying would intertwine with Wolsey's fate.Belief in prophecy ran through every level of Tudor society. It reached a fever pitch during the dangerous 1530s, when queens and courtiers were beheaded, monasteries fell, and rebels were hanged from trees across the North of England.

Many prophecies were used for political purposes. Uprisers against Henry VII said they were following the ancient sages. The rebels of the Pilgrimage of Grace cried that Henry VIII was the ancient 'Mouldwarp,' a monster ruler foretold by Merlin who would be "cast down." Anthony Babington, who conspired to assassinate Elizabeth I, carried a prediction of Merlin's sayings. One popular prophecy during Elizabeth's time was "When HEMPE is soon, England's done." HEMPE was thought to stand for Henry-Edward-Mary-Philip-Elizabeth. Madeleine Dodds in Political Prophecies in the Reign of Henry VIII wrote: "Political prophecies tended to be invoked at a time of crisis, usually to demonstrate that some drastic change, either desired or already accomplished, had been foreseen by the sages of the past."

In the 1700 and 1800s, Mother Shipton's prophecies broadened to cataclysmic disasters, amazing inventions, and, of course, the end of the world. Stripped of politics, they were more potent than ever. Perhaps they filled a deep craving within to feel that everything happens by some design, even if it is drawn by an ancient mystic, sage or witch. We are all of us fulfilling an obscure and coded destiny.

It's a craving that we still see around us today. It just might be part of being human.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Published on July 07, 2015 03:30

July 4, 2015

The Truth About Torture and the Tower of London

By Nancy Bilyeau

On a March night in 1534, a man and woman hurried past a row of cottages on the outer grounds of the Tower of London. They had almost reached the gateway to Tower Hill and, not far beyond it, the city of London, when a group of yeomen warders on night watch appeared in their path, holding lanterns.

In response the young couple turned toward each other, in what seemed a lover’s embrace. But something about the man caught the attention of Yeoman Warder Charles Gore. He held his lantern higher and within seconds recognized the pair. The man was a fellow yeoman warder, John Bawd, and the woman was Alice Tankerville, a condemned thief and prisoner.

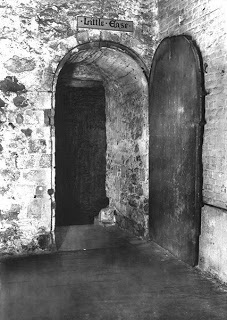

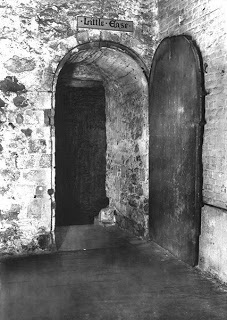

So ended the Tower’s first known escape attempt by a woman. But Alice’s accomplice and admirer, the guard John Bawd, was destined to enter the Tower record books too, and for the grimmest of reasons—he is the first known occupant of a peculiar torture cell used during the reigns of the Tudors and early Stuarts. The windowless cell measured 1.2m (4 square feet) and bore the faintly prim name of Little Ease. The prisoner within it could not stand nor sit nor lie down but crouched over, in increasing agony, until freed from the suffocating, dark space.

Torture and the Tower of London have long had an uneasy relationship. The echoes of those screams are part of the walled fortress’s allure, along with the X marks the spot of Queen Anne Boleyn’s and the Lady Jane Grey’s decapitations and tales of the travails of inmates Ralegh, Cranmer, Fisher and More. Today’s visitors see for themselves, in well-curated exhibits, the replicas of the rack and other devices fashioned for pain. Tower publications are emphatic: Torture took place during a brief span in its near 1,000-year history. Which is true. But it happened, and with an intensity that cannot be denied.

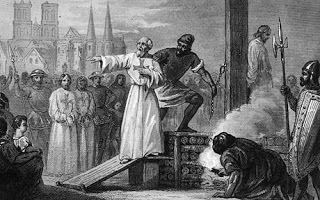

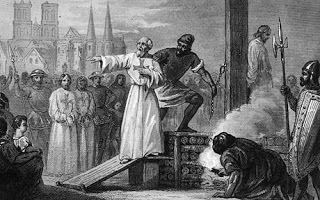

In 1215 England outlawed torture through the passage of Magna Carta, except by royal warrant. The first king to authorize it, reluctantly, was Edward II. He submitted to intense pressure from the Pope to follow the lead of the king of France and demolish the Order of the Knights Templar, part of a tradition begun during the Crusades. King Philip IV of France, jealous of the Templars’ wealth and power, charged them with heresy, obscene rituals, idolatry and other offenses. The French knights denied all, and were duly tortured. Some who broke down and “confessed” were released; all who denied wrongdoing were burned at the stake.

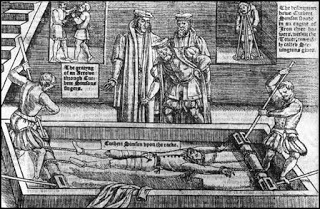

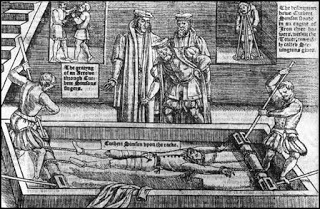

Once Edward II had ordered imprisonment of members of the English chapter, French monks arrived in London bearing their instruments of torture. In 1311 the Knights Templar “were questioned and examined in the presence of notaries while suffering under the torments of the rack” within the Tower of London as well as prisons of Aldgate, Ludgate, Newgate and Bishopgate, according to The History of the Knights Templar, the Temple Church, and the Temple, by Charles G. Addison. And so the Tower—principally a royal residence, military stronghold, armory, and menagerie up until that time—was baptized in torture.

Did the instruments remain after the Knights Templars were crushed, to be used on other prisoners? We cannot be certain, although there is no record of it. The next mention of a rack within the Tower is a startling one—an unsavory nobleman made Constable of the Tower pushed for one to be installed. John Holland, third duke of Exeter, arranged for a rack to be brought into the Tower. It is not known if men were stretched upon it or if it was merely used to frighten. In any case, this rack is known to history as the Duke of Exeter’s Daughter.

It was in the 16th century that prisoners were unquestionably tortured in the Tower of London. The royal family rarely used the fortress on the Thames as a residence; more and more, its stone buildings contained prisoners. And while the Tudor monarchs seem glittering successes to us now, in their own time they were beset by insecurities: rebellions, conspiracies and other threats both domestic and foreign. There was a willingness at the top of the government to override the law to obtain certain ends. This created a perfect storm for torture.

“It was during the time of the Tudors that the use of torture reached its height,” wrote historian L.A. Parry in his 1933 book The History of Torture in England. “Under Henry VIII it was frequently employed; it was only used in a small number of cases in the reigns of Edward VI and of Mary. It was whilst Elizabeth sat on the throne that it was made use of more than in any other period of history.”

Yeoman Warder John Bawd admitted he had planned the escape of Alice Tankerville “for the love and affection he bore her.” Unmoved, the Lieutenant of the Tower ordered Bawd into Little Ease, where he crouched, in growing agony. The lovers were condemned to horrible deaths for trying to escape. According to a letter in the State Papers of Lord Lisle, written on March 28, Alice Tankerville was “hanged in chains at low water mark upon the Thames on Tuesday. John Bawd is in Little Ease cell in the Tower and is to be racked and hanged.”

Today no one knows exactly where Little Ease was located. One theory: within the nooks and crannies of the White Tower. Another: in the basement of the old Flint Tower. No visitor sees it today; it was torn down or walled up long ago. Besides Little Ease, the most-used torture devices were the rack, manacles, and a horrific creation called the Scavenger’s Daughter. For many prisoners, solitary confinement, repeated interrogation, and the threat of physical pain were enough to make them tell their tormentors anything they wanted to know.

Often the victims ended up in the Tower for religious reasons. Anne Askew was tortured and killed for her Protestant beliefs; Edmund Campion for his Catholic ones. But the crimes varied. “The majority of the prisoners were charged with high treason, but murder, robbery, embezzling the Queen’s plate, and failure to carry out proclamations against state players were among the offenses,” wrote Parry. The monarch did not need to sign off on torture requests, although sometime he or she did. Elizabeth I personally directed that torture be used on the members of the Babington Conspiracy, a group that plotted to depose her and replace her with Mary Queen of Scots. But usually these initiatives went through the Privy Council or tapped the powers of the Star Chamber. It is believed that in some cases, permission was never sought at all.

Over and over, names pop up in state papers of those confined to Little Ease: “On 3 May 1555: Stephen Happes, for his lewd behavior and obstinacy, committed this day to the Tower to remain in Little Ease for two or three days till he may be further examined.”

After the death of Elizabeth and succession of James I came the most famous prisoner of them all to be held in Little Ease, Guy Fawkes. Charged with plotting to blow up the king and Parliament, Fawkes was subjected to both manacles and rack to obtain his confession and the names of his fellow conspirators. After he had told his questioners everything they asked, Fawkes was still shackled hand and foot in Little Ease and left there for a number of days.

And after that final burst of savagery, Little Ease was no more. A House of Commons committee reported the same year as Fawkes’ execution that the room was “disused.” In 1640, during the reign of Charles I, torture was abolished forever; there would be no more forcing prisoners to crouch for days in dark airless rooms, no more rack or hanging from chains.

And so, mercifully, closed one of the darkest chapters in England’s history.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Tapestry completes the trilogyNancy Bilyeau’s historical thriller trilogy, published in 10 countries, is set in the reign of Henry VIII. The Crown was placed on the shortlist of the Crime Writers' Association's Ellis Peters Historical Dagger Award for 2012. The Chalice won the award for Best Historical Mystery from RT Reviewers in 2013. The Tapestry was published in March 2015. To learn more, go to www.nancybilyeau.com

The Tapestry completes the trilogyNancy Bilyeau’s historical thriller trilogy, published in 10 countries, is set in the reign of Henry VIII. The Crown was placed on the shortlist of the Crime Writers' Association's Ellis Peters Historical Dagger Award for 2012. The Chalice won the award for Best Historical Mystery from RT Reviewers in 2013. The Tapestry was published in March 2015. To learn more, go to www.nancybilyeau.com

On a March night in 1534, a man and woman hurried past a row of cottages on the outer grounds of the Tower of London. They had almost reached the gateway to Tower Hill and, not far beyond it, the city of London, when a group of yeomen warders on night watch appeared in their path, holding lanterns.

In response the young couple turned toward each other, in what seemed a lover’s embrace. But something about the man caught the attention of Yeoman Warder Charles Gore. He held his lantern higher and within seconds recognized the pair. The man was a fellow yeoman warder, John Bawd, and the woman was Alice Tankerville, a condemned thief and prisoner.

So ended the Tower’s first known escape attempt by a woman. But Alice’s accomplice and admirer, the guard John Bawd, was destined to enter the Tower record books too, and for the grimmest of reasons—he is the first known occupant of a peculiar torture cell used during the reigns of the Tudors and early Stuarts. The windowless cell measured 1.2m (4 square feet) and bore the faintly prim name of Little Ease. The prisoner within it could not stand nor sit nor lie down but crouched over, in increasing agony, until freed from the suffocating, dark space.

Torture and the Tower of London have long had an uneasy relationship. The echoes of those screams are part of the walled fortress’s allure, along with the X marks the spot of Queen Anne Boleyn’s and the Lady Jane Grey’s decapitations and tales of the travails of inmates Ralegh, Cranmer, Fisher and More. Today’s visitors see for themselves, in well-curated exhibits, the replicas of the rack and other devices fashioned for pain. Tower publications are emphatic: Torture took place during a brief span in its near 1,000-year history. Which is true. But it happened, and with an intensity that cannot be denied.

In 1215 England outlawed torture through the passage of Magna Carta, except by royal warrant. The first king to authorize it, reluctantly, was Edward II. He submitted to intense pressure from the Pope to follow the lead of the king of France and demolish the Order of the Knights Templar, part of a tradition begun during the Crusades. King Philip IV of France, jealous of the Templars’ wealth and power, charged them with heresy, obscene rituals, idolatry and other offenses. The French knights denied all, and were duly tortured. Some who broke down and “confessed” were released; all who denied wrongdoing were burned at the stake.

Once Edward II had ordered imprisonment of members of the English chapter, French monks arrived in London bearing their instruments of torture. In 1311 the Knights Templar “were questioned and examined in the presence of notaries while suffering under the torments of the rack” within the Tower of London as well as prisons of Aldgate, Ludgate, Newgate and Bishopgate, according to The History of the Knights Templar, the Temple Church, and the Temple, by Charles G. Addison. And so the Tower—principally a royal residence, military stronghold, armory, and menagerie up until that time—was baptized in torture.

Did the instruments remain after the Knights Templars were crushed, to be used on other prisoners? We cannot be certain, although there is no record of it. The next mention of a rack within the Tower is a startling one—an unsavory nobleman made Constable of the Tower pushed for one to be installed. John Holland, third duke of Exeter, arranged for a rack to be brought into the Tower. It is not known if men were stretched upon it or if it was merely used to frighten. In any case, this rack is known to history as the Duke of Exeter’s Daughter.

It was in the 16th century that prisoners were unquestionably tortured in the Tower of London. The royal family rarely used the fortress on the Thames as a residence; more and more, its stone buildings contained prisoners. And while the Tudor monarchs seem glittering successes to us now, in their own time they were beset by insecurities: rebellions, conspiracies and other threats both domestic and foreign. There was a willingness at the top of the government to override the law to obtain certain ends. This created a perfect storm for torture.

“It was during the time of the Tudors that the use of torture reached its height,” wrote historian L.A. Parry in his 1933 book The History of Torture in England. “Under Henry VIII it was frequently employed; it was only used in a small number of cases in the reigns of Edward VI and of Mary. It was whilst Elizabeth sat on the throne that it was made use of more than in any other period of history.”

Yeoman Warder John Bawd admitted he had planned the escape of Alice Tankerville “for the love and affection he bore her.” Unmoved, the Lieutenant of the Tower ordered Bawd into Little Ease, where he crouched, in growing agony. The lovers were condemned to horrible deaths for trying to escape. According to a letter in the State Papers of Lord Lisle, written on March 28, Alice Tankerville was “hanged in chains at low water mark upon the Thames on Tuesday. John Bawd is in Little Ease cell in the Tower and is to be racked and hanged.”

Today no one knows exactly where Little Ease was located. One theory: within the nooks and crannies of the White Tower. Another: in the basement of the old Flint Tower. No visitor sees it today; it was torn down or walled up long ago. Besides Little Ease, the most-used torture devices were the rack, manacles, and a horrific creation called the Scavenger’s Daughter. For many prisoners, solitary confinement, repeated interrogation, and the threat of physical pain were enough to make them tell their tormentors anything they wanted to know.

Often the victims ended up in the Tower for religious reasons. Anne Askew was tortured and killed for her Protestant beliefs; Edmund Campion for his Catholic ones. But the crimes varied. “The majority of the prisoners were charged with high treason, but murder, robbery, embezzling the Queen’s plate, and failure to carry out proclamations against state players were among the offenses,” wrote Parry. The monarch did not need to sign off on torture requests, although sometime he or she did. Elizabeth I personally directed that torture be used on the members of the Babington Conspiracy, a group that plotted to depose her and replace her with Mary Queen of Scots. But usually these initiatives went through the Privy Council or tapped the powers of the Star Chamber. It is believed that in some cases, permission was never sought at all.

Over and over, names pop up in state papers of those confined to Little Ease: “On 3 May 1555: Stephen Happes, for his lewd behavior and obstinacy, committed this day to the Tower to remain in Little Ease for two or three days till he may be further examined.”

“10 January 1591: Richard Topcliffe is to take part in an examination in the Tower of George Beesley, seminary priest, and Robert Humberson, his companion. And if you shall see good cause by their obstinate refusal to declare the truth of such things as shall be laid to their charge in Her Majesty’s behalf, then shall you by authority hereof commit them to the prison called Little Ease or to such other ordinary place of punishment as hath been accustomed to be used in those cases, and to certify proceedings from time to time.”

After the death of Elizabeth and succession of James I came the most famous prisoner of them all to be held in Little Ease, Guy Fawkes. Charged with plotting to blow up the king and Parliament, Fawkes was subjected to both manacles and rack to obtain his confession and the names of his fellow conspirators. After he had told his questioners everything they asked, Fawkes was still shackled hand and foot in Little Ease and left there for a number of days.

And after that final burst of savagery, Little Ease was no more. A House of Commons committee reported the same year as Fawkes’ execution that the room was “disused.” In 1640, during the reign of Charles I, torture was abolished forever; there would be no more forcing prisoners to crouch for days in dark airless rooms, no more rack or hanging from chains.

And so, mercifully, closed one of the darkest chapters in England’s history.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Tapestry completes the trilogyNancy Bilyeau’s historical thriller trilogy, published in 10 countries, is set in the reign of Henry VIII. The Crown was placed on the shortlist of the Crime Writers' Association's Ellis Peters Historical Dagger Award for 2012. The Chalice won the award for Best Historical Mystery from RT Reviewers in 2013. The Tapestry was published in March 2015. To learn more, go to www.nancybilyeau.com

The Tapestry completes the trilogyNancy Bilyeau’s historical thriller trilogy, published in 10 countries, is set in the reign of Henry VIII. The Crown was placed on the shortlist of the Crime Writers' Association's Ellis Peters Historical Dagger Award for 2012. The Chalice won the award for Best Historical Mystery from RT Reviewers in 2013. The Tapestry was published in March 2015. To learn more, go to www.nancybilyeau.com

Published on July 04, 2015 18:15

Seven Surprising Facts About Anne of Cleves

by Nancy Bilyeau

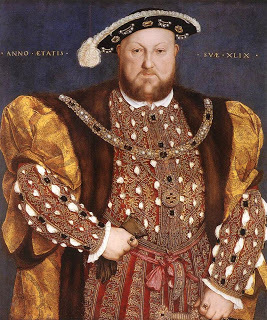

Everyone thinks they know the story of the fourth wife of Henry VIII. She was the German princess whom he married for diplomatic reasons, but when the 48-year-old widower first set eyes on his 24-year-old bride-to-be, he was repulsed.

With great reluctance, Henry went through with the wedding – saying darkly, “I am not well handled”—but after six months he’d managed to get an annulment and the unconsummated marriage was no more. Although Anne had behaved impeccably as queen, she accepted her new status as “sister” and lived a quiet, comfortable existence in England until 1557, when she became the last of the wives of King Henry VIII to die.

And so Anne of Cleves has either been treated as a punchline in the serio-comic saga of Henry VIII’s wives or someone who was smart enough to agree to a divorce, trading in an obese tyrant for a rich settlement. But the life of Anne of Cleves is more complex than the stereotypes would have you believe.

And so Anne of Cleves has either been treated as a punchline in the serio-comic saga of Henry VIII’s wives or someone who was smart enough to agree to a divorce, trading in an obese tyrant for a rich settlement. But the life of Anne of Cleves is more complex than the stereotypes would have you believe.

1.) Anne’s father was a Renaissance thinker. The assumption is that Anne grew up in a backward German duchy, too awkward and ignorant to impress a monarch who’d once moved a kingdom for the sophisticated charms of Anne Boleyn. But her father, Duke John, was a patron of Erasmus, the Dutch Renaissance scholar.

1.) Anne’s father was a Renaissance thinker. The assumption is that Anne grew up in a backward German duchy, too awkward and ignorant to impress a monarch who’d once moved a kingdom for the sophisticated charms of Anne Boleyn. But her father, Duke John, was a patron of Erasmus, the Dutch Renaissance scholar.

The Cleves court was liberal and fair, with low taxes for its citizens. And the duke made great efforts to steer a calm course through the religious uproar engulfing Germany in the 1520s and 1530s, earning the name John the Peaceful. He died in 1538, so his must have been the greatest influence on Anne, rather than her more bellicose brother, William. In Germany, highborn ladies were not expected to sing or play musical instruments, but Anne would have been exposed to the moderate, thoughtful political ideals espoused by William the Peaceful.

2.) Anne was born a Catholic and died a Catholic. Her mother, Princess Maria of Julich-Berg, had traditional religious values and brought up her daughters as Catholics, no matter what Martin Luther said. Their brother, Duke William, was an avowed Protestant, and the family seems to have moved in that direction when he succeeded to his father’s title.

Anne was accommodating when it came to religion. She did not hesitate to follow the lead of her husband Henry VIII, who was head of the Church of England. But in 1553, when her step-daughter Mary took the throne, she asked that Anne become a Catholic. Anne agreed. When she was dying, she requested that she have “the suffrages of the holy church according to the Catholic faith.”

Duke William

Duke William

Jeanne D'Albret

Jeanne D'Albret

3.) Her brother had a marriage that wasn’t consummated either.

Duke William was not as interested in peace as his father. What he wanted more than anything else was to add Guelders to Cleves—but the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V had other ideas. William took the bold step of a French marriage so that France would support him should it come to war.

His bride was Jeanne D’Albret, the daughter of Marguerite of Angouleme and niece of King Francis. The “high-spirited” Jeanne was only 12 and did not want to marry William. She was whipped by her family and physically carried to the altar by the Constable of France. But when Charles V took hold of Guelders, France did nothing to help William of Cleves. The four-year-old marriage was annulled—it had never been consummated. Her next husband was Antoine de Bourbon, whom she loved. Their son would one day become Henry IV, king of France.

Holbein's portrait of Amelia of Cleves.4.) Hans Holbein painted her accurately. The question of Anne’s appearance continues to baffle modern minds. In portraits she looks attractive, certainly prettier than Jane Seymour. A French ambassador who saw her in Cleves said she was “of middling beauty and of very assured and resolute countenance.”

Holbein's portrait of Amelia of Cleves.4.) Hans Holbein painted her accurately. The question of Anne’s appearance continues to baffle modern minds. In portraits she looks attractive, certainly prettier than Jane Seymour. A French ambassador who saw her in Cleves said she was “of middling beauty and of very assured and resolute countenance.”

It is still unclear how hard Thomas Cromwell pushed for this marriage, but certainly he was not stupid enough to trick his volatile king into wedding someone hideous. The famous Hans Holbein was told to paint truthful portraits of Anne and her sister Amelia. After looking at them, Henry VIII chose Anne. Later the king blamed people for overpraising her beauty but he did not blame or punish Holbein. The portrait captures her true appearance. While we don't find her repulsive, Henry did.

5.) Henry VIII never called her a “Flanders Mare.” The English king’s attitude toward his fourth wife was very unusual for a 16th century monarch. Royal marriages sealed diplomatic alliances, and queens were expected to be pious and gracious, not sexy.

5.) Henry VIII never called her a “Flanders Mare.” The English king’s attitude toward his fourth wife was very unusual for a 16th century monarch. Royal marriages sealed diplomatic alliances, and queens were expected to be pious and gracious, not sexy.

Henry wanted more than anything to send Anne home and not marry her, which would have devastated the young woman. He was only prevented from such cruelty by the (temporary) need for this foreign alliance. But while he fumed to his councilors and friends, he did not publicly ridicule her appearance. The report that Henry VIII cried loudly that she was a “Flanders mare” is not based on contemporary documents.

6.) Anne of Cleves wanted to remarry Henry VIII. After the king’s fifth wife, young Catherine Howard, was divorced and then executed for adultery, Anne wanted to be queen again. Her brother, William of Cleves, asked his ambassador to pursue her reinstatement. But Henry said no. When he took a sixth wife, the widow Catherine Parr, Anne felt humiliated and received medical treatment for melancholy. Her name came up as a possible wife for various men, including Thomas Seymour, but nothing came of it. She never remarried or left England.

7.) Anne of Cleves is the only one of Henry’s wives to be buried in Westminster Abbey. Henry himself is buried at Windsor with favorite wife Jane Seymour, but Anne is interred in the same structure as Edward the Confessor and most of the Plantagenet, Tudor and Stuart rulers. In her will she remembered all of her servants, and bequeathed her best jewels to the stepdaughters she loved, Mary and Elizabeth.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Nancy Bilyeau is the author of the historical thrillers The Crown and The Chalice, set in Tudor England, published in nine countries. The Chalice won the award for Best Historical Mystery of 2013 at the RT Awards. Anne of Cleves is a character in The Chalice and the third book in the trilogy, The Tapestry, which was published March 2015. To learn more, go to www.nancybilyeau.com

Nancy Bilyeau is the author of the historical thrillers The Crown and The Chalice, set in Tudor England, published in nine countries. The Chalice won the award for Best Historical Mystery of 2013 at the RT Awards. Anne of Cleves is a character in The Chalice and the third book in the trilogy, The Tapestry, which was published March 2015. To learn more, go to www.nancybilyeau.com

Everyone thinks they know the story of the fourth wife of Henry VIII. She was the German princess whom he married for diplomatic reasons, but when the 48-year-old widower first set eyes on his 24-year-old bride-to-be, he was repulsed.

With great reluctance, Henry went through with the wedding – saying darkly, “I am not well handled”—but after six months he’d managed to get an annulment and the unconsummated marriage was no more. Although Anne had behaved impeccably as queen, she accepted her new status as “sister” and lived a quiet, comfortable existence in England until 1557, when she became the last of the wives of King Henry VIII to die.

And so Anne of Cleves has either been treated as a punchline in the serio-comic saga of Henry VIII’s wives or someone who was smart enough to agree to a divorce, trading in an obese tyrant for a rich settlement. But the life of Anne of Cleves is more complex than the stereotypes would have you believe.

And so Anne of Cleves has either been treated as a punchline in the serio-comic saga of Henry VIII’s wives or someone who was smart enough to agree to a divorce, trading in an obese tyrant for a rich settlement. But the life of Anne of Cleves is more complex than the stereotypes would have you believe. 1.) Anne’s father was a Renaissance thinker. The assumption is that Anne grew up in a backward German duchy, too awkward and ignorant to impress a monarch who’d once moved a kingdom for the sophisticated charms of Anne Boleyn. But her father, Duke John, was a patron of Erasmus, the Dutch Renaissance scholar.

1.) Anne’s father was a Renaissance thinker. The assumption is that Anne grew up in a backward German duchy, too awkward and ignorant to impress a monarch who’d once moved a kingdom for the sophisticated charms of Anne Boleyn. But her father, Duke John, was a patron of Erasmus, the Dutch Renaissance scholar. The Cleves court was liberal and fair, with low taxes for its citizens. And the duke made great efforts to steer a calm course through the religious uproar engulfing Germany in the 1520s and 1530s, earning the name John the Peaceful. He died in 1538, so his must have been the greatest influence on Anne, rather than her more bellicose brother, William. In Germany, highborn ladies were not expected to sing or play musical instruments, but Anne would have been exposed to the moderate, thoughtful political ideals espoused by William the Peaceful.

2.) Anne was born a Catholic and died a Catholic. Her mother, Princess Maria of Julich-Berg, had traditional religious values and brought up her daughters as Catholics, no matter what Martin Luther said. Their brother, Duke William, was an avowed Protestant, and the family seems to have moved in that direction when he succeeded to his father’s title.

Anne was accommodating when it came to religion. She did not hesitate to follow the lead of her husband Henry VIII, who was head of the Church of England. But in 1553, when her step-daughter Mary took the throne, she asked that Anne become a Catholic. Anne agreed. When she was dying, she requested that she have “the suffrages of the holy church according to the Catholic faith.”

Duke William

Duke William

Jeanne D'Albret

Jeanne D'Albret3.) Her brother had a marriage that wasn’t consummated either.

Duke William was not as interested in peace as his father. What he wanted more than anything else was to add Guelders to Cleves—but the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V had other ideas. William took the bold step of a French marriage so that France would support him should it come to war.

His bride was Jeanne D’Albret, the daughter of Marguerite of Angouleme and niece of King Francis. The “high-spirited” Jeanne was only 12 and did not want to marry William. She was whipped by her family and physically carried to the altar by the Constable of France. But when Charles V took hold of Guelders, France did nothing to help William of Cleves. The four-year-old marriage was annulled—it had never been consummated. Her next husband was Antoine de Bourbon, whom she loved. Their son would one day become Henry IV, king of France.

Holbein's portrait of Amelia of Cleves.4.) Hans Holbein painted her accurately. The question of Anne’s appearance continues to baffle modern minds. In portraits she looks attractive, certainly prettier than Jane Seymour. A French ambassador who saw her in Cleves said she was “of middling beauty and of very assured and resolute countenance.”

Holbein's portrait of Amelia of Cleves.4.) Hans Holbein painted her accurately. The question of Anne’s appearance continues to baffle modern minds. In portraits she looks attractive, certainly prettier than Jane Seymour. A French ambassador who saw her in Cleves said she was “of middling beauty and of very assured and resolute countenance.”It is still unclear how hard Thomas Cromwell pushed for this marriage, but certainly he was not stupid enough to trick his volatile king into wedding someone hideous. The famous Hans Holbein was told to paint truthful portraits of Anne and her sister Amelia. After looking at them, Henry VIII chose Anne. Later the king blamed people for overpraising her beauty but he did not blame or punish Holbein. The portrait captures her true appearance. While we don't find her repulsive, Henry did.

5.) Henry VIII never called her a “Flanders Mare.” The English king’s attitude toward his fourth wife was very unusual for a 16th century monarch. Royal marriages sealed diplomatic alliances, and queens were expected to be pious and gracious, not sexy.

5.) Henry VIII never called her a “Flanders Mare.” The English king’s attitude toward his fourth wife was very unusual for a 16th century monarch. Royal marriages sealed diplomatic alliances, and queens were expected to be pious and gracious, not sexy.Henry wanted more than anything to send Anne home and not marry her, which would have devastated the young woman. He was only prevented from such cruelty by the (temporary) need for this foreign alliance. But while he fumed to his councilors and friends, he did not publicly ridicule her appearance. The report that Henry VIII cried loudly that she was a “Flanders mare” is not based on contemporary documents.

6.) Anne of Cleves wanted to remarry Henry VIII. After the king’s fifth wife, young Catherine Howard, was divorced and then executed for adultery, Anne wanted to be queen again. Her brother, William of Cleves, asked his ambassador to pursue her reinstatement. But Henry said no. When he took a sixth wife, the widow Catherine Parr, Anne felt humiliated and received medical treatment for melancholy. Her name came up as a possible wife for various men, including Thomas Seymour, but nothing came of it. She never remarried or left England.

7.) Anne of Cleves is the only one of Henry’s wives to be buried in Westminster Abbey. Henry himself is buried at Windsor with favorite wife Jane Seymour, but Anne is interred in the same structure as Edward the Confessor and most of the Plantagenet, Tudor and Stuart rulers. In her will she remembered all of her servants, and bequeathed her best jewels to the stepdaughters she loved, Mary and Elizabeth.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Nancy Bilyeau is the author of the historical thrillers The Crown and The Chalice, set in Tudor England, published in nine countries. The Chalice won the award for Best Historical Mystery of 2013 at the RT Awards. Anne of Cleves is a character in The Chalice and the third book in the trilogy, The Tapestry, which was published March 2015. To learn more, go to www.nancybilyeau.com

Nancy Bilyeau is the author of the historical thrillers The Crown and The Chalice, set in Tudor England, published in nine countries. The Chalice won the award for Best Historical Mystery of 2013 at the RT Awards. Anne of Cleves is a character in The Chalice and the third book in the trilogy, The Tapestry, which was published March 2015. To learn more, go to www.nancybilyeau.com

Published on July 04, 2015 13:05

July 3, 2015

An Interview With Alison Weir

By Nancy Bilyeau

I am thrilled to share my interview with not only one of the most successful historians writing today but also a personal hero: Alison Weir. My first Alison Weir book was The Princes in the Tower. It was fascinating--both provocative and convincing. Alison's books are history made compulsively readable; the research is extensive and yet it never, ever dulls the narrative.

One of my favorite aspects of Alison's writing is her shrewd, perceptive and yet deliciously stinging assessment of the major players in English history. I will treat you to her description of queen-to-be Elizabeth Wydville in The Wars of the Roses:

"Elizabeth had once been one of Queen Margaret's ladies, which firmly placed her in the wrong camp to start with. She was of medium height, with a good figure, and she was beautiful, having long gilt-blonde hair and an alluring smile. Edward was oblivious to the fact that she was also calculating, ambitious, devious, greedy, ruthless and arrogant."

Alison Weir has written extensively about Tudor and Plantagenet England, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Elizabeth I. When she published The Lady in the Tower in 2009, covering the arrest, trial and execution of Anne Boleyn, I wondered what new perspective she-- or anyone--could possibly bring to this thoroughly written about queen. I had my answer when I came to the last page of the book, moved to tears as I realized as never before how completely abandoned Anne was after her husband rejected her and how difficult it must have been to rally her strength and courage.

Beginning with the the bestseller Innocent Traitor, Alison also writes historical fiction. Her new book is A Dangerous Inheritance: A Novel of Tudor Rivals and the Secret of the Tower. It is the story of two women of history: Kate Plantagenet, illegitimate daughter of Richard III, and Katherine Grey, younger sister of Lady Jane Grey, who was herself imprisoned in the Tower after a secret marriage during the reign of her cousin, Elizabeth I. Not only does the novel bring these women to life with poignant detail but it connects them in surprising--and suspenseful-- ways.

Without further ado...Alison Weir.

Nancy Bilyeau: After I finished A Dangerous Inheritance, I felt disturbed by how lost in their dangerous times these two women were. Was that one of your goals in writing the book, to illuminate how less-well-known women of that age could come to tragedy?

Alison Weir: Yes, it was. I am always interested in retrieving women's histories, and I wanted to show how the constaints of noble birth, royal blood and gender could impact on young girls.

NB: Did you become intrigued by Katherine Grey while researching Lady Jane Grey for your novel and decide then to tell her story as well? And how different she was from her sister!

AW: I became intrigued years ago when I read Two Tudor Portraits by Hester W. Chapman. I wrote Katherine's story in Elizabeth the Queen, but not in any great depth, but I knew enough of it to know that it was a very dramatic tale--and a tragic one. She was very different from Lady Jane Grey; she was beautiful where Jane was plain, placid where Jane was feisty; she was no bluestocking or formidably learned, as Jane was, and in some ways she comes across as lacking in common sense and forethought, but one cannot but feel sympathy for her.

NB: What do you think of the current theory that Frances Brandon was not as abusive to her daughter Jane Grey as historically assumed? Frances was a complex figure in your novel.

AW: I don't buy it! We have Jane's own testimony and other evidence. A historian friend, Nicola Tallis, is writing a biography of Frances, and she believes the traditional view is the correct one--although maybe Henry Grey was even more unpleasant!

NB: Elizabeth I is known to have disliked Katherine Grey and refused to name her heir even before the scandalous marriage and pregnancy. Do you think the dislike was at all justified and would Katherine Grey have made a good queen of England in the 16th century?

AW: Katherine's own behavior--her failure to convert back to the Protestant faith and her flirtations with Spain--was not conducive to Elizabeth thinking kindly of her, but Elizabeth was pretty paranoid about anyone with a claim to the succession, so Katherine was damned from the start. She was pretty and she was younger than the Queen--red flags to a bull!--and she acted very rashly in marrying Edward Seymour. It undermined Elizabeth's policy, threatened her throne, and must have been galling to a queen who rejected marriage for political--and probably psychological--reasons. Katherine did not have what it took to be a queen, neither the brains nor the resolve. She lived in a fantasy world. I can understand why Elizabeth was harsh with her--and in many ways I think it was justified.

NB: How much is known about Richard III's daughter, Kate Plantagenet? Was it more challenging or more interesting to develop her character and plot, since there is less documentation of her life than Katherine Grey's?

AW: Yes, she is mentioned in only four documents--a gift to any novelist, as her life is a blank canvas. But I knew the context of it, as I've studied Richard III's reign over many years. I had to rely on a lot of detective work, inference and probability.

NB: Why did you decide to tell their stories in one book, and not write a book on each of them?

AW: The idea for the book evolved gradually. It was originally going to be based on the premise that Perkin Warbeck really was Richard, Duke of York, but I couldn't make that work, given the source material and the flimsy premise on which he based his claim. I liked the idea of a mystery with a supernatural theme, possibly a timeslip. I wanted to find a new way in which to explore the fate of the Princes in the Tower, and I needed a love story to replace that of Perkin Warbeck and Katherine Gordon. I also wanted to write a sequel to Innocent Traitor. It occurred to me too that writing about Richard III from the point of view of the daughter who loved him would be a novel approach. Eventually, all these ideas came together--and after many nights spent lying awake wondering how to meld them!

NB: The character and actions of Richard III loom large in this book. He fascinates, if not obsesses, people of that time. And couldn't it be argued, with the archaeological dig in Leicester, that he fascinates us today? Why is that?

AW: People love a mystery, and they also love conspiracy theories. Yes, Richard fascinates--and many become obsessed, which concerns me. As a historian, I feel I must be objective and not emotionally involved. There is a lot of compelling circumstantial evidence that Richard had the Princes murdered and he was a ruthless operator. If there was convincing evidence to counteract that, I would go with it. But nothing I have read has changed my view.

NB: Your view of Henry VII and Margaret Beaufort was not positive in the novel. Have you always thought of them in this way or did research for the book form newer evaluations?

AW: Some see Henry VII as a Machiavellian ruler; it's trendy nowadays to view Margaret Beaufort as sinister. Historically, I take a different view, but this was fiction, and they are seen from the point of view of Richard's daughter, so naturally she would find them menacing.

-------------------------------------

Thank you, Alison Weir, for agreeing to this interview, and for more information, go to http://alisonweir.org.uk/

This interview originally ran on the site A Bloody Good Read in November 2012.

Published on July 03, 2015 18:39

June 27, 2015

Love of Art in Fiction

I'm pleased to share my article in the series Love of Art in Historical Fiction. Stephanie Renee dos Santos interviewed me on my love of art, which traces back to my father, who was a watercolor landscape artist:

"The Tapestry by Nancy Bilyeau is the golden star of this Tudor mystery trilogy, featuring novice nun Joanna Stafford and her difficulties and adventures through the tumultuous reign of King Henry the VIII. This novel to the best of my knowledge explores for the first time ever the arts of Tudor England in historical fiction. I reveled in learning about “arras”, the formal term for Flemish tapestry work of the sixteenth century and the fact that England was in possession of one of the world’s greatest collections of them. Bilyeau takes us inside King Henry the VIII’s court and into his royal artist studio under the helm of German artist Hans Holbein the Younger who produced numerous paintings for the king like the little painting “The Dance of Death” featuring a floating skeleton visiting a ruler, for no one, not even a king escapes death’s clutches. Full of secret plots and twisted motives this mystery weaves a story that keeps you wondering until the end. You’ll be surprised, dismayed, and consumed by the tale that unfolds and enjoy learning about the art and artists of this time.Sketch, paint, catalog…throw the loom shuttle and try to please the tastes and temper of King Henry the VIII or else…"

To read the interview, go here.

Published on June 27, 2015 12:13

June 7, 2015

I Am Not a Historian

I AM NOT A HISTORIAN

There. I said it.

I’m still alive. J

More and more, it appears that historical novelists are positioning themselves as historians. Readers demand accuracy in their fiction set in the past—authors certified in history can supply it.

Philippa Gregory’s website begins with this statement: “Philippa Gregory was an established historian and writer when she discovered her interest in the Tudor period and wrote the novel The Other Boleyn Girl which was made into a TV drama and a major film.”

I’ve seen other websites and interviews and book jackets in which the novelists either proudly proclaim it or weave the word into their background: “historian.” It’s become something of a magical word, and not just because it was the title of one of my favorite books: Elizabeth Kostova’s The Historian. (That book mixed digging for obscure historical facts in quiet libraries with…Dracula!)

I’ve never made this claim for myself because I believe I lack the necessary credentials…don’t I?

Let’s take a look at the description in Merriam Webster: 1. “a student or writer of history; especially: one who produces a scholarly synthesis. 2.: a writer of compiler of a chronicle.”

Another definition: “historian: an expert in or student of history, especially that of a particular period, geographical region, or social phenomenon.”

OK. I studied history for my bachelor’s degree at the University of Michigan. After I “broke the curve” of a test given in the early 20th century American history class taught by Professor Sidney Fine, himself a nationally known historian and a Guggenheim Fellow, Professor Fine invited me to his Ann Arbor house. He offered me lemonade and we drank it on his elegant wooden porch as he suggested that I pursue a master’s degree in history. I realize now that this was it: the secret handshake, the door opening to the chamber in which dwelled historians.

But I didn’t pass through the door. I was eager to launch myself on the world of work, not remain at the university, pursuing another degree. (I know: Nuts!)

Without advanced degrees in history, one cannot claim to be a historian. At least, that’s what I’ve always assumed. If you read those definitions above one more time, they don’t specify any sort of degree. Still, I shy away from putting this word on my website, bio, book jacket or facebook page. Just doesn’t seem right.

Here’s the experience I do offer readers of my work

Journalist—at newspapers and then at magazines, I learned on the job how to assess facts, assimilate information and structure a story. I’ve always had an image in my mind of being trained by a historian—a distinguished older man, bearded of course (looking like Professor Fine!), leans over a student at work on the thick table, chiding, “No! Can’t you tell that those are discredited documents? What am I going to do with you??” But I do seek accuracy and practice skepticism. In my years in media, if I made a mistake it did more than earn the disfavor of the bearded professor. It could lead to a printed correction and maybe the boot!

Working as a reporter also made me rather…assertive. When I was frustrated with my research on The Crown, trying to find elusive details about being confined in the 1530s in the Tower of London, I decided to go to the source. I used the “contact” email on the website for the Tower and didn’t stop bothering them until they referred me to someone with access to documents. I’ve since worked my way through two curatorial interns. One emailed me a PDF of Edward Seymour’s diet sheet while he was imprisoned, another pulled together every contemporary fact about the beheading on Tower Hill of Thomas Cromwell. (Don’t let anyone tell you he died at Tyburn!)

History lover—I did like my study of history at the University of Michigan. But since I was 11 years old I have loved reading on my own about centuries past, primarily stories set in Europe and, of course, Tudor England. I pored over every biography I could find on Catherine of Aragon, Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn, Mary I and Elizabeth I. The historical fiction that first captured my heart was written by Norah Lofts, Jean Plaidy, Mary Stewart and Anya Seton. Later on, I devoured Mary Renault, Robert Graves, Margaret George, Bernard Cornwell, C.W. Gortner, Kate Quinn, Patricia Bracewell and Mary Sharratt.

Storyteller – As a writer of narrative nonfiction for 20 years, I learned a great deal from my editors on clarity, pacing and the need for the right descriptive detail. I’ve tried to pass these lessons on to the writers I edit too. I also wrote three screenplays before beginning The Crown, and learned from teachers such as screenwriter Max Adams how to write visually and describe characters with the right evocative phrase.

I always wonder what other historical novelists feel about the “historian” question. For this blog post, I decided to ask a few. (Remember, I am assertive J )

Erika Robuck, author of fantastic historical fiction like Hemingway’s Girl and The House of Hawthorne, says, “"I think an historian is an expert in a time period or culture, and holds a degree to support that level of expertise. I am an enthusiast, not an historian.”

Eva Stachniak, who has written two of my favorite historical novels, The Winter Palace and Empress of the Night, says, “As a writer of historical novels, I have to know my history, in and out, understand it on many levels, political, social, cultural. I have to be able to imagine how everyday life was lived at the time when my novel is set. For my two Catherine the Great novels, I studied the life of the Russian court, not just its politics, but also its everyday routines. I researched spies and spying, dressmaking, bookbinding, medical procedures and the ins and outs of 18th century renovations. Does it make me a historian? I am not convinced. But it makes me a student of history. It makes me re-imagine the exiting research in a creative way. However, even if I make no claims to being a historian, I claim my passion for history and my ability to make it seem alive for my readers.”

My friend Sophie Perinot, author of Sister Queens and Medicis Daughter: A Novel of Marguerite de Valois (pub date: December 2015), has thought about this question even more than I have. She had some fascinating things to say:

“I am not a historian, despite having a BA in history--at least when I have my novelist hat on--because my work isn’t driven by history, or entirely limited by it.

“I've had to give serious thought to the line between what I call "H"istory (academic history) and history as portrayed by novelists. I've discussed the subject in a pair of lectures given to university history students during their unit on the uses of undergraduate history degrees after graduation. And I think most historical novelists grapple with the "who is a historian" question because Historical Fiction is undeniably a pop culture way that people today consume history, and those of us who write it are keenly aware that lots of fans blur the line between NON-FICTION HISTORY and the FICTIONALIZED HISTORY OF HISTORICAL NOVELS.

“Let me start by saying that I have a background in history having graduated with a BA in that subject—but I don’t write BIG “H” history, nor, in my opinion does any other writer in my genre. Professors write BIG H academic history ( I have a sister who is a professor of history so I have tremendous respect for academic historians)

“Why do I say this? Well first and foremost a novelist's work is not driven by the overt goal of educating readers on a particular period or by presenting an overview of a historical issue or time. The historical novelist's work is driven by considerations of plot and theme—by the desire to tell a universal story that is set in the past but transcends it.

“So, I am not a historian, at least when I have my novelist hat on, because my work isn’t driven by history, or entirely limited by it. BUT if I write first rate historical fiction – and I’d like to think I do – then in telling my story I want to be true to historical facts as we know them. Good historical novelists use the same sorts of resources that students of history would use to write an academic paper—JSTOR, scholarly journal articles, primary sources, and secondary sources (biographies, prior histories).”

I hope that when you read my historical thrillers, or the fiction by Erika Robuck, Eva Stachniak or Sophie Perinot, you’ll relish not just the story but the awareness that we take our history very seriously—even if we don’t call ourselves historians.

Of that, I think, even Professor Fine would approve.

There. I said it.

I’m still alive. J

More and more, it appears that historical novelists are positioning themselves as historians. Readers demand accuracy in their fiction set in the past—authors certified in history can supply it.

Philippa Gregory’s website begins with this statement: “Philippa Gregory was an established historian and writer when she discovered her interest in the Tudor period and wrote the novel The Other Boleyn Girl which was made into a TV drama and a major film.”

I’ve seen other websites and interviews and book jackets in which the novelists either proudly proclaim it or weave the word into their background: “historian.” It’s become something of a magical word, and not just because it was the title of one of my favorite books: Elizabeth Kostova’s The Historian. (That book mixed digging for obscure historical facts in quiet libraries with…Dracula!)

I’ve never made this claim for myself because I believe I lack the necessary credentials…don’t I?

Let’s take a look at the description in Merriam Webster: 1. “a student or writer of history; especially: one who produces a scholarly synthesis. 2.: a writer of compiler of a chronicle.”

Another definition: “historian: an expert in or student of history, especially that of a particular period, geographical region, or social phenomenon.”

OK. I studied history for my bachelor’s degree at the University of Michigan. After I “broke the curve” of a test given in the early 20th century American history class taught by Professor Sidney Fine, himself a nationally known historian and a Guggenheim Fellow, Professor Fine invited me to his Ann Arbor house. He offered me lemonade and we drank it on his elegant wooden porch as he suggested that I pursue a master’s degree in history. I realize now that this was it: the secret handshake, the door opening to the chamber in which dwelled historians.

But I didn’t pass through the door. I was eager to launch myself on the world of work, not remain at the university, pursuing another degree. (I know: Nuts!)

Without advanced degrees in history, one cannot claim to be a historian. At least, that’s what I’ve always assumed. If you read those definitions above one more time, they don’t specify any sort of degree. Still, I shy away from putting this word on my website, bio, book jacket or facebook page. Just doesn’t seem right.

Here’s the experience I do offer readers of my work

Journalist—at newspapers and then at magazines, I learned on the job how to assess facts, assimilate information and structure a story. I’ve always had an image in my mind of being trained by a historian—a distinguished older man, bearded of course (looking like Professor Fine!), leans over a student at work on the thick table, chiding, “No! Can’t you tell that those are discredited documents? What am I going to do with you??” But I do seek accuracy and practice skepticism. In my years in media, if I made a mistake it did more than earn the disfavor of the bearded professor. It could lead to a printed correction and maybe the boot!

Working as a reporter also made me rather…assertive. When I was frustrated with my research on The Crown, trying to find elusive details about being confined in the 1530s in the Tower of London, I decided to go to the source. I used the “contact” email on the website for the Tower and didn’t stop bothering them until they referred me to someone with access to documents. I’ve since worked my way through two curatorial interns. One emailed me a PDF of Edward Seymour’s diet sheet while he was imprisoned, another pulled together every contemporary fact about the beheading on Tower Hill of Thomas Cromwell. (Don’t let anyone tell you he died at Tyburn!)

History lover—I did like my study of history at the University of Michigan. But since I was 11 years old I have loved reading on my own about centuries past, primarily stories set in Europe and, of course, Tudor England. I pored over every biography I could find on Catherine of Aragon, Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn, Mary I and Elizabeth I. The historical fiction that first captured my heart was written by Norah Lofts, Jean Plaidy, Mary Stewart and Anya Seton. Later on, I devoured Mary Renault, Robert Graves, Margaret George, Bernard Cornwell, C.W. Gortner, Kate Quinn, Patricia Bracewell and Mary Sharratt.

Storyteller – As a writer of narrative nonfiction for 20 years, I learned a great deal from my editors on clarity, pacing and the need for the right descriptive detail. I’ve tried to pass these lessons on to the writers I edit too. I also wrote three screenplays before beginning The Crown, and learned from teachers such as screenwriter Max Adams how to write visually and describe characters with the right evocative phrase.

I always wonder what other historical novelists feel about the “historian” question. For this blog post, I decided to ask a few. (Remember, I am assertive J )

Erika Robuck, author of fantastic historical fiction like Hemingway’s Girl and The House of Hawthorne, says, “"I think an historian is an expert in a time period or culture, and holds a degree to support that level of expertise. I am an enthusiast, not an historian.”

Eva Stachniak, who has written two of my favorite historical novels, The Winter Palace and Empress of the Night, says, “As a writer of historical novels, I have to know my history, in and out, understand it on many levels, political, social, cultural. I have to be able to imagine how everyday life was lived at the time when my novel is set. For my two Catherine the Great novels, I studied the life of the Russian court, not just its politics, but also its everyday routines. I researched spies and spying, dressmaking, bookbinding, medical procedures and the ins and outs of 18th century renovations. Does it make me a historian? I am not convinced. But it makes me a student of history. It makes me re-imagine the exiting research in a creative way. However, even if I make no claims to being a historian, I claim my passion for history and my ability to make it seem alive for my readers.”

My friend Sophie Perinot, author of Sister Queens and Medicis Daughter: A Novel of Marguerite de Valois (pub date: December 2015), has thought about this question even more than I have. She had some fascinating things to say:

“I am not a historian, despite having a BA in history--at least when I have my novelist hat on--because my work isn’t driven by history, or entirely limited by it.

“I've had to give serious thought to the line between what I call "H"istory (academic history) and history as portrayed by novelists. I've discussed the subject in a pair of lectures given to university history students during their unit on the uses of undergraduate history degrees after graduation. And I think most historical novelists grapple with the "who is a historian" question because Historical Fiction is undeniably a pop culture way that people today consume history, and those of us who write it are keenly aware that lots of fans blur the line between NON-FICTION HISTORY and the FICTIONALIZED HISTORY OF HISTORICAL NOVELS.

“Let me start by saying that I have a background in history having graduated with a BA in that subject—but I don’t write BIG “H” history, nor, in my opinion does any other writer in my genre. Professors write BIG H academic history ( I have a sister who is a professor of history so I have tremendous respect for academic historians)

“Why do I say this? Well first and foremost a novelist's work is not driven by the overt goal of educating readers on a particular period or by presenting an overview of a historical issue or time. The historical novelist's work is driven by considerations of plot and theme—by the desire to tell a universal story that is set in the past but transcends it.

“So, I am not a historian, at least when I have my novelist hat on, because my work isn’t driven by history, or entirely limited by it. BUT if I write first rate historical fiction – and I’d like to think I do – then in telling my story I want to be true to historical facts as we know them. Good historical novelists use the same sorts of resources that students of history would use to write an academic paper—JSTOR, scholarly journal articles, primary sources, and secondary sources (biographies, prior histories).”

I hope that when you read my historical thrillers, or the fiction by Erika Robuck, Eva Stachniak or Sophie Perinot, you’ll relish not just the story but the awareness that we take our history very seriously—even if we don’t call ourselves historians.

Of that, I think, even Professor Fine would approve.

Published on June 07, 2015 08:48

June 2, 2015

A Book Review on Catholicmom.com

I'm very pleased that Sister Margaret Kerry, who I "met" on twitter, reviewed my novels on Catholicmom.com. What higher honor could there be--that a real-life nun reviews books revolving around a fictional nun?

Here's what she says:

"After I read The Crown (which won the Best Historical Mystery Award in 2013) I watched the PBS television series Wolf Hall. I’m glad I did. With the first of Nancy Bilyeau’s acclaimed books as a Catholic guide, along with Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons, I was able to sort out the myopic elements in Wolf Hall. Catholicism in Wolf Hall is seen through the eyes of Thomas Cromwell. He is infamous for beginning the destruction of monasteries and religious communities in England. Henry VIII got needed loot for England’s coffers; Cromwell was able to forward his agenda for a more Protestant England. The Crown , first in a series by Bilyeau, is an inside view of this time of historic upheaval though the eyes of a Dominican novice. She wears a medal of Thomas á Becket and knows of Thomas More’s allegiance to the Church, “I die the good King’s servant, but God’s first.” This quote, one of my favorites, was left out ofWolf Hall..."

Sister Margaret has been a Daughter of St. Paul for 40 years. She proclaims the gospel in all sorts of ways, writing books and conducting workshops on media literacy. She's great on Twitter!

To read her full review, go to http://catholicmom.com/2015/05/29/historical-mystery-series-remedies-wolf-halls-revisionist-history/

Here's what she says:

"After I read The Crown (which won the Best Historical Mystery Award in 2013) I watched the PBS television series Wolf Hall. I’m glad I did. With the first of Nancy Bilyeau’s acclaimed books as a Catholic guide, along with Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons, I was able to sort out the myopic elements in Wolf Hall. Catholicism in Wolf Hall is seen through the eyes of Thomas Cromwell. He is infamous for beginning the destruction of monasteries and religious communities in England. Henry VIII got needed loot for England’s coffers; Cromwell was able to forward his agenda for a more Protestant England. The Crown , first in a series by Bilyeau, is an inside view of this time of historic upheaval though the eyes of a Dominican novice. She wears a medal of Thomas á Becket and knows of Thomas More’s allegiance to the Church, “I die the good King’s servant, but God’s first.” This quote, one of my favorites, was left out ofWolf Hall..."

Sister Margaret has been a Daughter of St. Paul for 40 years. She proclaims the gospel in all sorts of ways, writing books and conducting workshops on media literacy. She's great on Twitter!

To read her full review, go to http://catholicmom.com/2015/05/29/historical-mystery-series-remedies-wolf-halls-revisionist-history/

Published on June 02, 2015 14:34

June 1, 2015

June 'Romantic Times' Reviews 'THE TAPESTRY'

I was thrilled to receive the RT Reviews Award for Best Historical Mystery for THE CHALICE last year. Obviously, RT Reviews is aces with me!

I'm pleased to share the June issue's review of THE TAPESTRY:

To read the full review, go here.

I'm pleased to share the June issue's review of THE TAPESTRY:

"This final book in the Joanna Stafford series brings more mystery, danger and intrigue in Tudor England. Readers familiar with the story of Henry VIII and his many wives will recognize some of the events. However, Bilyeau gives us more. She provides historical detail of conditions in England and Europe and treats us to lesser-known possibilities and motives for the tragic events that unfold. Bilyeau creates a fascinating framework for this story of a popular historical period..."

To read the full review, go here.

Published on June 01, 2015 14:42

May 17, 2015

Four Stars From the 'British Weekly'

Very excited to share that The Tapestry received four stars from the publication The British Weekly.

"Bilyeau is masterful in creating details that move the narrative story forward and in creating real dilemmas for Joanna Stafford in this book. Bilyeau’s words transport the reader back to the English court at a time when you had to be careful what you said or risk losing your head. The author Bilyeau tries to strike a balance between the politics the King Henry VIII’s court and Joanna’s personal life. For the third book, you don’t have to read the first two books in the series, but it makes more sense if you do...."

To read the rest, go here.

"Bilyeau is masterful in creating details that move the narrative story forward and in creating real dilemmas for Joanna Stafford in this book. Bilyeau’s words transport the reader back to the English court at a time when you had to be careful what you said or risk losing your head. The author Bilyeau tries to strike a balance between the politics the King Henry VIII’s court and Joanna’s personal life. For the third book, you don’t have to read the first two books in the series, but it makes more sense if you do...."

To read the rest, go here.

Published on May 17, 2015 06:25

May 10, 2015

Recap of Wolf Hall, Episode 6 "Master of Phantoms"

What’s easy to miss in Wolf Hall is that, during his lifetime, Thomas Cromwell was feared. In the television series, based on Hilary Mantel’s two novels, Cromwell has shown himself, up until Episode 6, as both intelligent and cunning, with an easy familiarity with corruption. He has been a crook as well as a lawyer; he knows how to outsmart people. Still, he loves his family, he supports religious reform, he likes to cuddle kittens. This man is a Machiavellian with a heart of gold.

To read the rest on medievalists.net, go here.

Published on May 10, 2015 20:31