Nancy Bilyeau's Blog, page 19

February 22, 2016

Guest Post: The Lusitania Cover Up

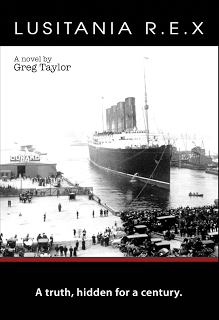

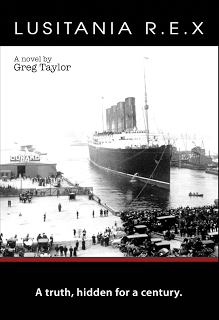

I'm pleased to welcome Greg Taylor to my blog today, to share with us the secrets of the Lusitania. Greg's book won the M.M. Bennetts Award for Historical Fiction last year.

The Lusitania Cover UpNearly 100 years after the sinking of the RMS Lusitania the truth came out

On May 1st 2015, the British government archives at Kew released declassified documents. What documents are kept secret? Those which are dangerous or embarrassing to the government. In the case of documents related to RMS Lusitania released on May 1st2014, both are true.

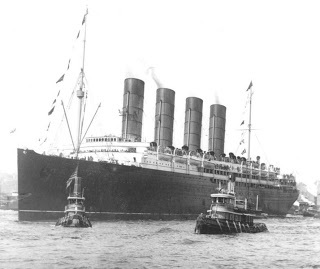

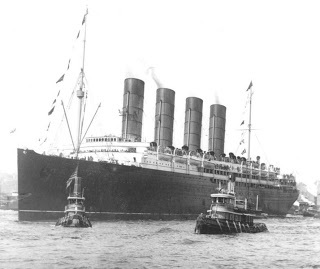

The sinking of the Lusitania was the 9/11 of its day. On May 7th 1915, the 31,550-ton Cunard Liner was en route to Liverpool from New York with 1,959 souls aboard when a German U-Boat torpedoed her just 11 miles off the coast of Ireland.

Everyone is familiar with the tale of the Titanic but what about the Lusitania?

She was launched into the River Clyde to the strains of “Rule Britannia” on June 7 1906, the largest moveable object ever created by man. On the Lusitania rested the hopes of the Empire and Cunard Lines that Britain would reclaim from the German liners the Blue Riband for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic, which she did on her third Atlantic crossing with a speed of 23.99 knots.

In 1915, the Lusitania was the fastest most luxurious ship making the transatlantic run. When she sailed from New York on May 1st 1915, the New York Times and other papers carried a warning from the German Embassy. Everyone ignored it - confident the fastest ship in the world could outrun any German submarine that might dare to threaten a passenger liner travelling from a neutral country.

The U20 spotted the Lusitania on the 7th of May, the last day of her crossing. The submarine nearly lost her due to the liner’s superior speed but a last minute change of direction gave the U20 an excellent shot. After being hit by a single torpedo, the Lusitania sank in eighteen minutes at a list so severe that only eight of the forty-two lifeboats were launched. Due to the thirty-degree list, the lifeboats on the port side smashed into the decks below, while those on the starboard side hung eight feet from the doomed ship.

Kapitänleutnant Schwieger, who ordered the torpedo strike, was shocked when he saw through his periscope a second, much larger explosion. He refused to permit his crew to look at the drowning passengers of the Lusitania.

To this day, experts continue to debate the cause of the second explosion that sealed the Lusitania’s fate after the torpedo struck. Imperial Germany immediately claimed the ship was loaded with explosives destined for the front.

During the official inquiry into the sinking of the Lusitania, the Admiralty manipulated testimony so that Lord Mersey reached an erroneous conclusion that multiple torpedoes struck the ship. The Admiralty knew Kapitänleutnant Schwieger had fired only a single torpedo but it was important to blame only Imperial Germany since the Admiralty had withdrawn the Lusitania’s escort ship. It was also known that First Sea Lord Winston Churchill had remarked that the loss of an ocean liner such as the Lusitania might help bring American into the war on the side of Britain.

What was in the documents released at Kew on the 99thanniversary of the sinking?

Under the 30 Year Rule, the British National Archive released internal memoranda between the Commonwealth Department and Ministry of War that showed that in 1982 the Government was concerned that divers to the Lusitania wreck were at risk because the wreck contained explosives. One of the memos went so far as to say that this disclosure might “blow up on us all”. The British government was worried about ramifications for British-American relations because the discovery of explosives on the wreck would imply the Lusitania had been a legitimate target.

A new book, Lusitania R.E.X, weaves fiction around the known facts to create a plausible explanation of some of the mysteries surrounding the sinking. The story is centred on one of the wealthiest men in the world, Alfred Vanderbilt, who lost his life after giving his lifebelt to a woman passenger. This historical fiction is replete with spies, secret societies and superweapons, as well as millionaires, monarchs and martyrs. In the book, Alfred and his fellow members of Skull and Bones, a Yale secret society that in 1911 included the President of the United States, the Secretary of War and the Secretary of the Treasury, have taken a secret cargo aboard the ship. The story unfolds on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean in settings that range from gilded palaces and the Lusitania to the blood-soaked trenches of Ypres.

To learn more, go to:

Amazon: http://mybook.to/greglusitania

Website: http://www.lusitaniarex.com/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/GregTaylor_LUSI

The Lusitania Cover UpNearly 100 years after the sinking of the RMS Lusitania the truth came out

On May 1st 2015, the British government archives at Kew released declassified documents. What documents are kept secret? Those which are dangerous or embarrassing to the government. In the case of documents related to RMS Lusitania released on May 1st2014, both are true.

The sinking of the Lusitania was the 9/11 of its day. On May 7th 1915, the 31,550-ton Cunard Liner was en route to Liverpool from New York with 1,959 souls aboard when a German U-Boat torpedoed her just 11 miles off the coast of Ireland.

Everyone is familiar with the tale of the Titanic but what about the Lusitania?

She was launched into the River Clyde to the strains of “Rule Britannia” on June 7 1906, the largest moveable object ever created by man. On the Lusitania rested the hopes of the Empire and Cunard Lines that Britain would reclaim from the German liners the Blue Riband for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic, which she did on her third Atlantic crossing with a speed of 23.99 knots.

In 1915, the Lusitania was the fastest most luxurious ship making the transatlantic run. When she sailed from New York on May 1st 1915, the New York Times and other papers carried a warning from the German Embassy. Everyone ignored it - confident the fastest ship in the world could outrun any German submarine that might dare to threaten a passenger liner travelling from a neutral country.

The U20 spotted the Lusitania on the 7th of May, the last day of her crossing. The submarine nearly lost her due to the liner’s superior speed but a last minute change of direction gave the U20 an excellent shot. After being hit by a single torpedo, the Lusitania sank in eighteen minutes at a list so severe that only eight of the forty-two lifeboats were launched. Due to the thirty-degree list, the lifeboats on the port side smashed into the decks below, while those on the starboard side hung eight feet from the doomed ship.

Kapitänleutnant Schwieger, who ordered the torpedo strike, was shocked when he saw through his periscope a second, much larger explosion. He refused to permit his crew to look at the drowning passengers of the Lusitania.

To this day, experts continue to debate the cause of the second explosion that sealed the Lusitania’s fate after the torpedo struck. Imperial Germany immediately claimed the ship was loaded with explosives destined for the front.

During the official inquiry into the sinking of the Lusitania, the Admiralty manipulated testimony so that Lord Mersey reached an erroneous conclusion that multiple torpedoes struck the ship. The Admiralty knew Kapitänleutnant Schwieger had fired only a single torpedo but it was important to blame only Imperial Germany since the Admiralty had withdrawn the Lusitania’s escort ship. It was also known that First Sea Lord Winston Churchill had remarked that the loss of an ocean liner such as the Lusitania might help bring American into the war on the side of Britain.

What was in the documents released at Kew on the 99thanniversary of the sinking?

Under the 30 Year Rule, the British National Archive released internal memoranda between the Commonwealth Department and Ministry of War that showed that in 1982 the Government was concerned that divers to the Lusitania wreck were at risk because the wreck contained explosives. One of the memos went so far as to say that this disclosure might “blow up on us all”. The British government was worried about ramifications for British-American relations because the discovery of explosives on the wreck would imply the Lusitania had been a legitimate target.

A new book, Lusitania R.E.X, weaves fiction around the known facts to create a plausible explanation of some of the mysteries surrounding the sinking. The story is centred on one of the wealthiest men in the world, Alfred Vanderbilt, who lost his life after giving his lifebelt to a woman passenger. This historical fiction is replete with spies, secret societies and superweapons, as well as millionaires, monarchs and martyrs. In the book, Alfred and his fellow members of Skull and Bones, a Yale secret society that in 1911 included the President of the United States, the Secretary of War and the Secretary of the Treasury, have taken a secret cargo aboard the ship. The story unfolds on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean in settings that range from gilded palaces and the Lusitania to the blood-soaked trenches of Ypres.

To learn more, go to:

Amazon: http://mybook.to/greglusitania

Website: http://www.lusitaniarex.com/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/GregTaylor_LUSI

Published on February 22, 2016 04:12

February 14, 2016

Valentine's Day, Third Century Style

By Nancy Bilyeau

Believe me, I would like to be able to deliver a sweet and touching historical anecdote. I tried. I really did. But you don't find hearts and flowers when you get to the beginning of the story of Valentine. You find martyrdom, imprisonment, plague, and death by clubbing. It's hard to conceive of anything less romantic than death by clubbing.

The Catholic Church distanced itself from St. Valentine's Day a while ago, and not because of any sort of distaste for chocolate hearts or hand-holding. The evidence that there really was a person who committed acts worthy of sainthood is fragmentary. Valentine is one of the "saints whose cult is larger than themselves, so to speak," according to Richard McBrien's Lives of the Saints. In 1969, the Pope quietly dropped Valentine's Day from the official calendar of saints' days.

The Catholic Church distanced itself from St. Valentine's Day a while ago, and not because of any sort of distaste for chocolate hearts or hand-holding. The evidence that there really was a person who committed acts worthy of sainthood is fragmentary. Valentine is one of the "saints whose cult is larger than themselves, so to speak," according to Richard McBrien's Lives of the Saints. In 1969, the Pope quietly dropped Valentine's Day from the official calendar of saints' days.

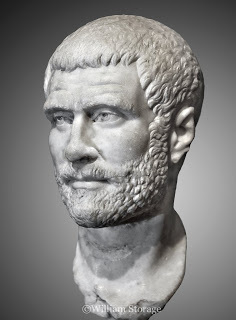

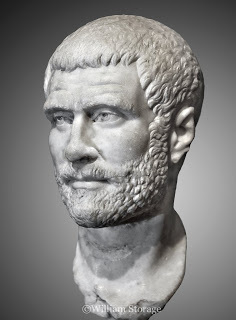

The consensus seems to be that Valentine is based on a Christian priest of that name who lived in Rome when the official religion was still pagan, during the reign of Claudius Gothicus, from 268 to 270 AD.

This was not a proud time in the history of the empire. Rome did not decline steadily from the glorious reigns of Julius and Augustus Ceasar to the crumbling under Honorius in 423 AD. There were peaks and valleys. This was a valley. Emperors rapidly succeeded each other through assassination in the mid-Third Century. There was death by poison, death by strangulation, death by hanging, death by being dragged naked from the back of a chariot through the streets. The year 238 AD saw six different emperors.

Claudius Gothicus, the Ceasar who would, legend has it, confront Valentine, was born a peasant in what is now Bosnia and rose rapidly through the ranks of the army. He was popular with the soldiers, a very tall man who liked to fight. His specialty was knocking out the teeth of an opponent, including, once, an opponent's horse. He played a key role in the assassination plot that eliminated Emperor Gallenius in Milan. The Rome that Claudius took charge of was near-bankrupt, with rebel populations causing lots of trouble in German and France in the West, and Syria in the East. Claudius desperately needed more soldiers in the Army, and he tried to officially discourage men from marrying.

As the story goes, Claudius heard that the priest Valentine was busy marrying young Christian couples. Marriage was frowned on, Christianity forbidden. Valentine was arrested, unsurprisingly. Pressure was put on the priest to abandon his faith; he refused. The emperor decided to visit Valentine in prison. During this meeting, instead of being meek and obliging, Valentine tried to convert Cladius to Christianity. Disgusted, the emperor ordered his execution. Valentine was clubbed to death and then beheaded.

Three centuries later, long after Claudius died of the plague, a pope declared February 14th Valentine's day. One theory is that the Catholic leaders really wanted to banish the mid-February fertility celebration of Lupercalia. (What happened during Lupercalia? Let your imagination run wild and you still haven't come close.) Naming the day in honor of the martyred Valentine seems a wee random today. Nonetheless, the new holiday stuck, and in medieval times, all sorts of romantic stories were told.

Did any of these sweet tales have anything to do with the Third Century Valentine? Only one, that the night before the rebellious priest was to be executed, he wrote a letter to the daughter of his jailer, and signed it "Your Valentine."

The first Valentine's Day card was born.

Believe me, I would like to be able to deliver a sweet and touching historical anecdote. I tried. I really did. But you don't find hearts and flowers when you get to the beginning of the story of Valentine. You find martyrdom, imprisonment, plague, and death by clubbing. It's hard to conceive of anything less romantic than death by clubbing.

The Catholic Church distanced itself from St. Valentine's Day a while ago, and not because of any sort of distaste for chocolate hearts or hand-holding. The evidence that there really was a person who committed acts worthy of sainthood is fragmentary. Valentine is one of the "saints whose cult is larger than themselves, so to speak," according to Richard McBrien's Lives of the Saints. In 1969, the Pope quietly dropped Valentine's Day from the official calendar of saints' days.

The Catholic Church distanced itself from St. Valentine's Day a while ago, and not because of any sort of distaste for chocolate hearts or hand-holding. The evidence that there really was a person who committed acts worthy of sainthood is fragmentary. Valentine is one of the "saints whose cult is larger than themselves, so to speak," according to Richard McBrien's Lives of the Saints. In 1969, the Pope quietly dropped Valentine's Day from the official calendar of saints' days.The consensus seems to be that Valentine is based on a Christian priest of that name who lived in Rome when the official religion was still pagan, during the reign of Claudius Gothicus, from 268 to 270 AD.

This was not a proud time in the history of the empire. Rome did not decline steadily from the glorious reigns of Julius and Augustus Ceasar to the crumbling under Honorius in 423 AD. There were peaks and valleys. This was a valley. Emperors rapidly succeeded each other through assassination in the mid-Third Century. There was death by poison, death by strangulation, death by hanging, death by being dragged naked from the back of a chariot through the streets. The year 238 AD saw six different emperors.

Claudius Gothicus, the Ceasar who would, legend has it, confront Valentine, was born a peasant in what is now Bosnia and rose rapidly through the ranks of the army. He was popular with the soldiers, a very tall man who liked to fight. His specialty was knocking out the teeth of an opponent, including, once, an opponent's horse. He played a key role in the assassination plot that eliminated Emperor Gallenius in Milan. The Rome that Claudius took charge of was near-bankrupt, with rebel populations causing lots of trouble in German and France in the West, and Syria in the East. Claudius desperately needed more soldiers in the Army, and he tried to officially discourage men from marrying.

As the story goes, Claudius heard that the priest Valentine was busy marrying young Christian couples. Marriage was frowned on, Christianity forbidden. Valentine was arrested, unsurprisingly. Pressure was put on the priest to abandon his faith; he refused. The emperor decided to visit Valentine in prison. During this meeting, instead of being meek and obliging, Valentine tried to convert Cladius to Christianity. Disgusted, the emperor ordered his execution. Valentine was clubbed to death and then beheaded.

Three centuries later, long after Claudius died of the plague, a pope declared February 14th Valentine's day. One theory is that the Catholic leaders really wanted to banish the mid-February fertility celebration of Lupercalia. (What happened during Lupercalia? Let your imagination run wild and you still haven't come close.) Naming the day in honor of the martyred Valentine seems a wee random today. Nonetheless, the new holiday stuck, and in medieval times, all sorts of romantic stories were told.

Did any of these sweet tales have anything to do with the Third Century Valentine? Only one, that the night before the rebellious priest was to be executed, he wrote a letter to the daughter of his jailer, and signed it "Your Valentine."

The first Valentine's Day card was born.

Published on February 14, 2016 06:15

February 13, 2016

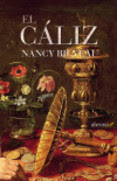

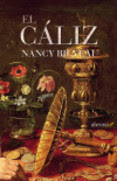

Celebrating the Trilogy's Publication in Spain

I was ecstatic when, after years of effort, a Spanish publisher was found for my Joanna Stafford novels. My main character is half-Spanish, after all. :) It sets her apart in Tudor England, makes her special. Joanna's mother, a Castile-born maid of honor who came to England with Catherine of Aragon, appears in The Crown. And in The Tapestry, the Holy Roman Emperor himself, Charles V, ruler of Spain, enters the plot, along with a few of his Inquisitors.

The publisher, Siruela, is an excellent one. Their chosen title is El Caliz, which is close to the English of "the cup." The catalog page is here.

I'm always intrigued by the covers designed in other countries. This one is, I think, quite interesting.

The Spanish edition of The Chalice, now on sale.

The publisher, Siruela, is an excellent one. Their chosen title is El Caliz, which is close to the English of "the cup." The catalog page is here.

I'm always intrigued by the covers designed in other countries. This one is, I think, quite interesting.

The Spanish edition of The Chalice, now on sale.

Published on February 13, 2016 06:42

January 14, 2016

Nicholas Carew: The Fatal Friendship of Henry VIII

Those who study the Tudor era are often astounded by how Henry VIII could spurn, exile or kill his wives, sometimes without much evidence of a conscience. But it was just as dangerous to be the king's friend.

Sir Nicholas Carew was placed in the household of Prince Henry at age six. They were close friends for almost forty years, sharing a passion for jousting. Carew was knighted by 1517, made a Knight of the Garter, and held the important post of Master of Horse. He was a member of the Privy Council and served as a trusted diplomat. His beautiful wife, Elizabeth, was rumored to be the king's mistress before Nicholas married her. Henry VIII had given her some jewelry, including diamonds and pearls.

Although related to Anne Boleyn, Nicholas Carew had sympathy for Katherine of Aragon and was fond of Princess Mary. Carew was a key member of the faction that worked with Thomas Cromwell to turn the king against Anne and replace her with Jane Seymour in 1536.

In 1538 several of the king's relatives on his mother's Yorkist side were accused of plotting against the king. The evidence was very weak; nonetheless, Henry Courtenay, marquis of Exeter, and Henry Pole, Lord Montagu, were arrested and executed. (Pole's mother, the countess of Salisbury, was beheaded in 1541. His young son disappeared in the Tower, never to be seen again. Courtenay's son was imprisoned until the reign of Queen Mary.)

Carew was disturbed by the arrests in the "Exeter Conspiracy" and the methods Cromwell used to destroy these men he'd known nearly as long as Henry VIII. He said, "I marvel greatly that the indictment against the lord marquis was so secretly handled and for what purpose, for the like was never seen." Around the same time Henry VIII and Carew quarreled over something, and Carew told his old friend "an answer true rather than discreet."

On this "evidence," Carew was arrested. On Jan. 14, 1539, he was indicted, and on March 3rd he was taken to Tower Hill for execution, as had been Henry Courtenay and Henry Pole before him.

In his speech to the crowd, "he made a goodly confession, both of his folly and his superstitious faith." And with that, the king's oldest friend was killed.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Exeter Conspiracy is central to the story in my second novel, The Chalice.

Published on January 14, 2016 11:26

January 7, 2016

The Death of Katherine of Aragon

The first wife of Henry VIII, born a Spanish princess, married to him for more than 20 years, died this day in 1536. She was far from the court, in pain, abandoned except for those friends and servants brave enough to console her, without family by her side. The king had forbidden their daughter Mary from seeing her for years. The king himself rejoiced at her death, with his second wife, Anne Boleyn. There were many lessons in his treatment of Katherine, ones that most of his subsequent five wives chose to ignore.

She is buried at Peterborough Abbey, now Peterborough Cathedral. Her husband would not give her a queen's funeral. She was buried as the widow of his long-dead brother, Arthur Tudor.

The Peterborough Cathedral community embraces their role as the caretaker of the proud queen. This year there will be a festival throughout the month celebrating her, with services and lectures. Dr. James Foyle will give a talk on Friday January 29th on "The Forgotten Origins of the Tudor Rose." To learn more, go here.

Katherine is a character in my book The Crown, and plays a central, mentoring role in the life of my protagonist, Joanna Stafford.

A young and beautiful princess

A young and beautiful princess

She is buried at Peterborough Abbey, now Peterborough Cathedral. Her husband would not give her a queen's funeral. She was buried as the widow of his long-dead brother, Arthur Tudor.

The Peterborough Cathedral community embraces their role as the caretaker of the proud queen. This year there will be a festival throughout the month celebrating her, with services and lectures. Dr. James Foyle will give a talk on Friday January 29th on "The Forgotten Origins of the Tudor Rose." To learn more, go here.

Katherine is a character in my book The Crown, and plays a central, mentoring role in the life of my protagonist, Joanna Stafford.

A young and beautiful princess

A young and beautiful princess

Published on January 07, 2016 07:01

January 3, 2016

My Interview With Ian Rankin

I write novels.

I'm also a magazine editor and nonfiction writer. As the editor in chief of The Big Thrill, the online magazine of International Thriller Writers, I edit stories on the suspense-fiction genre and interviews, LOTS of interviews. A few of them I write myself, such as Sue Grafton in October.

This month I am proud to share my story on Ian Rankin, whose crime-fiction novels capture modern-day Scotland (they call it tartan noir!) with intricate stories. I'm struck by his complex views on morality, and during our hour-long conversation, I learned that he is someone who thinks about the reality of evil. He may not have obsessed over Thomas Aquinas' writings, as I did when writing The Crown, but man's capacity for darkness is on his mind a great deal

His new novel, Even Dogs in the Wild, "is about having to pay for past sins," he told me.

To read the interview, go here.

I'm also a magazine editor and nonfiction writer. As the editor in chief of The Big Thrill, the online magazine of International Thriller Writers, I edit stories on the suspense-fiction genre and interviews, LOTS of interviews. A few of them I write myself, such as Sue Grafton in October.

This month I am proud to share my story on Ian Rankin, whose crime-fiction novels capture modern-day Scotland (they call it tartan noir!) with intricate stories. I'm struck by his complex views on morality, and during our hour-long conversation, I learned that he is someone who thinks about the reality of evil. He may not have obsessed over Thomas Aquinas' writings, as I did when writing The Crown, but man's capacity for darkness is on his mind a great deal

His new novel, Even Dogs in the Wild, "is about having to pay for past sins," he told me.

To read the interview, go here.

Published on January 03, 2016 11:50

December 14, 2015

Was Prince Eddy Jack the Ripper?

On November 9, 1888, the body of Mary Kelly was found in her rented room off Dorset Street on London's East End by a landlord assistant sent to collect overdue rent. Mary, a young prostitute, was brutally slain--most agree, by Jack the Ripper.

The identity of this depraved murderer was never been solved, although many, many people have tried.

Along the way, some startling suspect names emerge. One is Prince Albert Victor, duke of Clarence and grandson to Queen Victoria.

Read my blog post on English Historical Fiction Authors to discover the strange baseless origin of this myth.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

The identity of this depraved murderer was never been solved, although many, many people have tried.

Along the way, some startling suspect names emerge. One is Prince Albert Victor, duke of Clarence and grandson to Queen Victoria.

Read my blog post on English Historical Fiction Authors to discover the strange baseless origin of this myth.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Published on December 14, 2015 09:28

December 13, 2015

When January 1st Wasn't the First of the Year

By Nancy Bilyeau

In a couple of weeks it will be the first day of 2016. Time to hang your freshly bought calendars and write a new year on your checks. But strange as it may seem, January 1st did not always signal the beginning of a new calendar year. Until 1752, the two were separate things in England and its colonies. Until that point, people began each calendar year on March 25, which was Annunciation Day—or Lady Day. This was the day the Angel Gabriel appeared to the Virgin Mary to deliver the news that she had conceived and would give birth to Jesus in nine months. It took an 18th century act of Parliament for England to officially begin each new calendar year on January 1st. The centuries of discrepancy cause lots of headaches for historians and genealogists. There’s no question that it’s strange, not least because England lagged behind much of the rest of Western Europe. Why did this Protestant nation cling to Annunciation Day—by its very definition a day revolving around the Virgin—as the time to change the calendar when most Catholic countries had already shifted to January 1st in the 16th century or 17th century?

It took an 18th century act of Parliament for England to officially begin each new calendar year on January 1st. The centuries of discrepancy cause lots of headaches for historians and genealogists. There’s no question that it’s strange, not least because England lagged behind much of the rest of Western Europe. Why did this Protestant nation cling to Annunciation Day—by its very definition a day revolving around the Virgin—as the time to change the calendar when most Catholic countries had already shifted to January 1st in the 16th century or 17th century?

The reason for the January 1st controversy has a lot to do with England’s refusal to take orders from a pope after Henry VIII’s break from Rome in the 1530s. It was Pope Gregory XIII who replaced Julius Caesar’s calendar, devised in 45 BC, with a new one in 1582—and it’s the Gregorian calendar we all use today. Reform was unquestionably needed. There were too many days in the year; the equinoxes were out of whack; the Julian calendar had strayed 10 days from the solar calendar. Among other things, the pope’s new calendar established that each calendar year begin on January 1st. Once it was issued, Italy, Spain and Portugal instantly adopted the Gregorian calendar, followed by France and the other Catholic countries of Europe. But England, Germany and the Netherlands refused. So for centuries, there were two calendars in Western Europe.

The first step to understanding this furor is to realize that Pope Gregory XIII was not simply someone who cared about calendars. Born in Bologna as Ugo Buoncompagno, he was a transitional pope. Certainly not as venal and corrupt as the Borgias a century earlier, he was a gifted teacher and administrative talent who nonetheless had an illegitimate son before marrying and really liked to spend money.

Once he became Gregory XIII, he spent huge sums on not only Catholic colleges but also displays such as the Gregorian Chapel in St. Peter’s. To pay for all this, he resorted to papal confiscation. Most relevant to our story, he supported the overthrow of Henry VIII’s Protestant daughter, Elizabeth I.

Gregory’s predecessor, Pope Pius V, had already excommunicated Elizabeth and declared her a usurper in 1570. During his papal office, Gregory put intense pressure on the Spanish king, Philip II, to invade and dethrone England’s queen. Gregory personally financed an armed force of 800 men to land in Ireland to join a Catholic rebellion against Elizabeth (it fizzled). Moreover, a Jesuit led the papal commission to devise the Gregorian calendar—and the Jesuits were the religious order specifically created to fight the Protestant Reformation. This all fueled Elizabethan England’s refusal to accept anything that originated in the Vatican. The fierce clashes between Catholic and Protestant in the 16th century are the tumultuous background of my historical thrillers. The heroine of my novels, The Crown, The Chalice, and The Tapestry, is a novice in the Dominican Order at Dartford Priory, outside London. But it’s not just the Christian splintering in early modern Europe that fascinates me. I also love studying what came long before the Renaissance. On a recent October, as Halloween approached, I researched the roots of the holiday’s celebration in Tudor England and made some discoveries. I learned that the roots of Halloween reach back to the Dark Ages Celtic festival of Samhain (“summer’s end”), when people lit bonfires and put on costumes to scare away the spirits of the unfriendly dead. All-Hallows-Even, which was shortened to “Halloween” in the 16th century, was a complex blend of Celtic and Catholic customs. After all, the holiday was the run-up to All Saints’ Day on November 1st, an occasion to venerate all the Catholic martyrs. Not surprisingly, the Protestant Reformers took a dim view of Halloween, but its popularity was so great that they were unable to stamp it out. My blog post on Halloween (http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com/2011/10/truth-about-halloween-and-tudor-england.html) stirred up so much attention that it made me want to keep reading about the distant and complex roots of what we celebrate today. I began thinking about the origins of Christmas and New Year’s Day the morning of December 20th of last year, when I stood outside my apartment building with my son, waiting for his school bus to arrive. Although it was 7:15 a.m., dawn had barely broken; the Christmas lights that the superintendent had strung over the bushes glowed yellow in the purplish-gray light. A hazy fullness hung in the air—and it seemed to carry a strange potency. Almost like something magical. I had no idea as I stood there that what I sensed would connect to January 1st and the fascinating furor over when to begin the calendar year.

I snapped a photo and posted it on my Facebook page, along with sharing a description of the strange feeling all around me. A high school friend, D.K. Carlson, offered an explanation: “The solstice is almost here.” It made me shiver to think it was the power of the winter solstice that touched me that morning: the approach of the shortest day of the year, the moment when the earth is in a point of its orbit farthest away from the sun. I find it very interesting that Julius Caesar established December 25th as the date of the winter solstice. It was—you guessed it—Pope Gregory XIII who made the adjustment to December 21st. Long before the time of Julius Caesar, man honored the solstice. Bronze Age archaeologists have uncovered symbols and signs that reveal awareness of the shortest day of the year. The monuments of Stonehenge and Newgrange in Ireland are believed to have solstice alignments. In 2000 BC, people may have gathered at Stonehenge in mid-December to pray for the sun to return again, the source of all life.

Again and again, in many societies and religions, the solstice has great meaning. For the Druids, it was Alban Arthuan, the Light of Winter. As part of the celebration, priests cut the mistletoe that grew on winter oaks and blessed it. Germanic pagans launched the tradition of burning the Yule log and decorating a home with clippings of evergreen trees. In Rome, not surprisingly, the celebrations became more debauched. Saturnalia, which took place in mid-December, ran the gamut from heavy drinking to gambling to reversing society norms, with masters waiting on slaves. Lighting candles was very important. So was the tradition of children going house to house, offering small gifts, such as wrapped fruit, in exchange for other tokens. Saturnalia was so popular that not even the Fall of Rome could kill it. It morphed into the Feast of Fools, celebrated from the Fifth Century until the Renaissance in much of Western Europe on January 1st. The servants became the masters, with a lower-echelon “Lord of Misrule” chosen to preside over all drunken festivities beginning in late December and concluding on the first of January. Not surprisingly, the early Catholic Church did not look kindly on the parties--stimulated by the winter solstice--that marked January 1st. The church leaders didn’t want something as important as beginning a new year to take place on that same day. In 567 AD, a Council of Tours decreed that the first of January was abolished and the blameless Annunciation Day was chosen. It took a while for this to be accepted, but by medieval times, people in England looked on March 25th as the beginning of the year. And this tradition stuck through the Plantagenets, the Tudors, the Stuarts, and into the time of the Hanoverians.

Until finally, in 1752, in the reign of George II, England—and its colonies in the Americas—made the change, and January 1st was officially deemed the beginning of the year.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In a couple of weeks it will be the first day of 2016. Time to hang your freshly bought calendars and write a new year on your checks. But strange as it may seem, January 1st did not always signal the beginning of a new calendar year. Until 1752, the two were separate things in England and its colonies. Until that point, people began each calendar year on March 25, which was Annunciation Day—or Lady Day. This was the day the Angel Gabriel appeared to the Virgin Mary to deliver the news that she had conceived and would give birth to Jesus in nine months.

It took an 18th century act of Parliament for England to officially begin each new calendar year on January 1st. The centuries of discrepancy cause lots of headaches for historians and genealogists. There’s no question that it’s strange, not least because England lagged behind much of the rest of Western Europe. Why did this Protestant nation cling to Annunciation Day—by its very definition a day revolving around the Virgin—as the time to change the calendar when most Catholic countries had already shifted to January 1st in the 16th century or 17th century?

It took an 18th century act of Parliament for England to officially begin each new calendar year on January 1st. The centuries of discrepancy cause lots of headaches for historians and genealogists. There’s no question that it’s strange, not least because England lagged behind much of the rest of Western Europe. Why did this Protestant nation cling to Annunciation Day—by its very definition a day revolving around the Virgin—as the time to change the calendar when most Catholic countries had already shifted to January 1st in the 16th century or 17th century?

The reason for the January 1st controversy has a lot to do with England’s refusal to take orders from a pope after Henry VIII’s break from Rome in the 1530s. It was Pope Gregory XIII who replaced Julius Caesar’s calendar, devised in 45 BC, with a new one in 1582—and it’s the Gregorian calendar we all use today. Reform was unquestionably needed. There were too many days in the year; the equinoxes were out of whack; the Julian calendar had strayed 10 days from the solar calendar. Among other things, the pope’s new calendar established that each calendar year begin on January 1st. Once it was issued, Italy, Spain and Portugal instantly adopted the Gregorian calendar, followed by France and the other Catholic countries of Europe. But England, Germany and the Netherlands refused. So for centuries, there were two calendars in Western Europe.

The first step to understanding this furor is to realize that Pope Gregory XIII was not simply someone who cared about calendars. Born in Bologna as Ugo Buoncompagno, he was a transitional pope. Certainly not as venal and corrupt as the Borgias a century earlier, he was a gifted teacher and administrative talent who nonetheless had an illegitimate son before marrying and really liked to spend money.

Once he became Gregory XIII, he spent huge sums on not only Catholic colleges but also displays such as the Gregorian Chapel in St. Peter’s. To pay for all this, he resorted to papal confiscation. Most relevant to our story, he supported the overthrow of Henry VIII’s Protestant daughter, Elizabeth I.

Gregory’s predecessor, Pope Pius V, had already excommunicated Elizabeth and declared her a usurper in 1570. During his papal office, Gregory put intense pressure on the Spanish king, Philip II, to invade and dethrone England’s queen. Gregory personally financed an armed force of 800 men to land in Ireland to join a Catholic rebellion against Elizabeth (it fizzled). Moreover, a Jesuit led the papal commission to devise the Gregorian calendar—and the Jesuits were the religious order specifically created to fight the Protestant Reformation. This all fueled Elizabethan England’s refusal to accept anything that originated in the Vatican. The fierce clashes between Catholic and Protestant in the 16th century are the tumultuous background of my historical thrillers. The heroine of my novels, The Crown, The Chalice, and The Tapestry, is a novice in the Dominican Order at Dartford Priory, outside London. But it’s not just the Christian splintering in early modern Europe that fascinates me. I also love studying what came long before the Renaissance. On a recent October, as Halloween approached, I researched the roots of the holiday’s celebration in Tudor England and made some discoveries. I learned that the roots of Halloween reach back to the Dark Ages Celtic festival of Samhain (“summer’s end”), when people lit bonfires and put on costumes to scare away the spirits of the unfriendly dead. All-Hallows-Even, which was shortened to “Halloween” in the 16th century, was a complex blend of Celtic and Catholic customs. After all, the holiday was the run-up to All Saints’ Day on November 1st, an occasion to venerate all the Catholic martyrs. Not surprisingly, the Protestant Reformers took a dim view of Halloween, but its popularity was so great that they were unable to stamp it out. My blog post on Halloween (http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com/2011/10/truth-about-halloween-and-tudor-england.html) stirred up so much attention that it made me want to keep reading about the distant and complex roots of what we celebrate today. I began thinking about the origins of Christmas and New Year’s Day the morning of December 20th of last year, when I stood outside my apartment building with my son, waiting for his school bus to arrive. Although it was 7:15 a.m., dawn had barely broken; the Christmas lights that the superintendent had strung over the bushes glowed yellow in the purplish-gray light. A hazy fullness hung in the air—and it seemed to carry a strange potency. Almost like something magical. I had no idea as I stood there that what I sensed would connect to January 1st and the fascinating furor over when to begin the calendar year.

I snapped a photo and posted it on my Facebook page, along with sharing a description of the strange feeling all around me. A high school friend, D.K. Carlson, offered an explanation: “The solstice is almost here.” It made me shiver to think it was the power of the winter solstice that touched me that morning: the approach of the shortest day of the year, the moment when the earth is in a point of its orbit farthest away from the sun. I find it very interesting that Julius Caesar established December 25th as the date of the winter solstice. It was—you guessed it—Pope Gregory XIII who made the adjustment to December 21st. Long before the time of Julius Caesar, man honored the solstice. Bronze Age archaeologists have uncovered symbols and signs that reveal awareness of the shortest day of the year. The monuments of Stonehenge and Newgrange in Ireland are believed to have solstice alignments. In 2000 BC, people may have gathered at Stonehenge in mid-December to pray for the sun to return again, the source of all life.

Again and again, in many societies and religions, the solstice has great meaning. For the Druids, it was Alban Arthuan, the Light of Winter. As part of the celebration, priests cut the mistletoe that grew on winter oaks and blessed it. Germanic pagans launched the tradition of burning the Yule log and decorating a home with clippings of evergreen trees. In Rome, not surprisingly, the celebrations became more debauched. Saturnalia, which took place in mid-December, ran the gamut from heavy drinking to gambling to reversing society norms, with masters waiting on slaves. Lighting candles was very important. So was the tradition of children going house to house, offering small gifts, such as wrapped fruit, in exchange for other tokens. Saturnalia was so popular that not even the Fall of Rome could kill it. It morphed into the Feast of Fools, celebrated from the Fifth Century until the Renaissance in much of Western Europe on January 1st. The servants became the masters, with a lower-echelon “Lord of Misrule” chosen to preside over all drunken festivities beginning in late December and concluding on the first of January. Not surprisingly, the early Catholic Church did not look kindly on the parties--stimulated by the winter solstice--that marked January 1st. The church leaders didn’t want something as important as beginning a new year to take place on that same day. In 567 AD, a Council of Tours decreed that the first of January was abolished and the blameless Annunciation Day was chosen. It took a while for this to be accepted, but by medieval times, people in England looked on March 25th as the beginning of the year. And this tradition stuck through the Plantagenets, the Tudors, the Stuarts, and into the time of the Hanoverians.

Until finally, in 1752, in the reign of George II, England—and its colonies in the Americas—made the change, and January 1st was officially deemed the beginning of the year.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Published on December 13, 2015 12:13

November 26, 2015

Furness Abbey: From Glory to Ghost-Haunted Ruins

By Nancy Bilyeau

This is the latest in a series devoted to the monastic ruins of England. My trilogy, The Crown, The Chalice, and The Tapestry, is set in the 1530s and early 1540s; the main character is a young Dominican novice at a priory facing destruction.

The novels are thrillers, but the framework is a serious look at Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries. I spent years researching the brutal ending of a way of life for 1,700 nuns, 3,200 monks and 1,800 friars, all expelled from their homes within a five-year period. The stone buildings themselves were confiscated by the king or given to his loyal courtiers. Many were stripped of value and demolished; some were left standing but crumbled over the centuries.

"You love faded glory," said my husband, who knows me better than anyone in the world. He's right—I feel a strong pull toward grand old houses, pallid churches, neglected cemeteries, seldom-visited landmarks. To me, few ruins are as poignant as those of an English abbey.

Furness Abbey, in the county of Cumbria, has a long and fascinating history, its dissolution marked a pivotal moment in the king's attack on the monasteries, and it is ravishingly beautiful. Oh, and according to legend it houses several ghosts. :)

Furness Abbey

King StephenThe Founding: Stephen, grandson of William the Conqueror, count of Bologne and Mortain, and later King of England during a time of chaos, established Furness in 1127. In the founding document, Stephen wrote: "That in Furness an order of regular monks be by divine permission established; which gift and offering, I, by supreme authority, appoint to be for ever observed; and, that it may remain firm and inviolate forever, I subscribe this charter with my hand and confirm it with the sign of the holy cross."

King StephenThe Founding: Stephen, grandson of William the Conqueror, count of Bologne and Mortain, and later King of England during a time of chaos, established Furness in 1127. In the founding document, Stephen wrote: "That in Furness an order of regular monks be by divine permission established; which gift and offering, I, by supreme authority, appoint to be for ever observed; and, that it may remain firm and inviolate forever, I subscribe this charter with my hand and confirm it with the sign of the holy cross."

The chosen location was a remote, narrow valley in the north of Lancashire near the coast; it was sometimes called "the vale of the deadly nightshade," because of an abundance of atropa belladonna, a beautiful plant with toxic berries. The abbey's buildings were all constructed with the vivid-colored local sandstone.

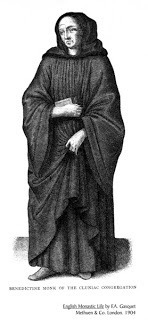

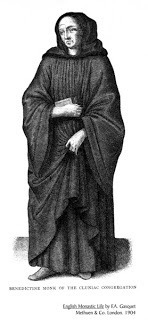

Cistercian habit

Cistercian habit

The Order: The Cistercians were founded in 1098 out of a desire to adhere more strictly to the Rules of St. Benedict. Its emphasis was on manual labor and self-sufficiency, with isolation being of great value. By 1154, there were 54 Cistercian monasteries in England, the largest were Fountains and Rievaulx abbeys in North Yorkshire ... and Furness.

The Glory: In spite of the Cistercian emphasis on austerity and contemplation, Furness grew in wealth and local influence over the next few centuries. It controlled 55,000 acres of land; its holdings included iron mines, tanneries, fisheries and mills. A close connection sprang up between the abbey and the Isle of Man, and more than one monk became Bishop of Man.

Robert the BruceBeing so close to Scotland, Furness inevitably got caught up in border tensions. When Robert the Bruce invaded England in 1322, the abbot allowed the Scottish leader to stay overnight at Furness and paid him the enormous bribe of ten thousand pounds so that the abbey would not be harmed. It worked; the marauding army moved through abbey property without laying waste to it.

Robert the BruceBeing so close to Scotland, Furness inevitably got caught up in border tensions. When Robert the Bruce invaded England in 1322, the abbot allowed the Scottish leader to stay overnight at Furness and paid him the enormous bribe of ten thousand pounds so that the abbey would not be harmed. It worked; the marauding army moved through abbey property without laying waste to it.

Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion, from a 1913 painting. Note

Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion, from a 1913 painting. Note

the prominence of monks in the fervor.The Dissolution: Furness was one of the first of the kingdom's larger monasteries to fall. Its destruction is laced with irony. The Pilgrimage of Grace, a rebellion in the north of England, broke out because a great many people disagreed with the direction of the king's reforms. They wished, among other things, to preserve the monasteries that Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII's chief minister, was busy closing down.

Historians agree that the abbot of Furness in 1536, Roger Pyle, was a fearful, nervous man. When the rebellion boiled over, Pyle fled to the stronghold of the Earl of Derby, leaving his monks behind. In his absence, some of the monks contributed money to the rebels and pressured Furness tenants to do the same.

Although the rebel army outnumbered the forces of Henry VIII, they were defeated. In the mop-up, Henry VIII's anger with the Northern monasteries flipped to rage. Abbots were hanged, monks rounded up. Two of the Furness monks were imprisoned and questioned. In 1537, the king's man, the Earl of Sussex, met with Abbot Roger Pyle, his mission being to find enough wrongdoing to justify closing the abbey.

Although the rebel army outnumbered the forces of Henry VIII, they were defeated. In the mop-up, Henry VIII's anger with the Northern monasteries flipped to rage. Abbots were hanged, monks rounded up. Two of the Furness monks were imprisoned and questioned. In 1537, the king's man, the Earl of Sussex, met with Abbot Roger Pyle, his mission being to find enough wrongdoing to justify closing the abbey.

But there was a problem: Abbot Pyle had shown no disloyalty. The Earl of Sussex came up with a solution that turned out to have profound consequences. He summoned the abbot to Wyland, a place where the severed heads of defiant abbots and monks were prominently posted, and then made a suggestion: The Furness abbot could surrender the abbey to the Crown and go willingly, along with the 28 innocent monks. That way, there would be no penalties or prosecutions. Abbot Pyle at once agreed, and he signed a document on April 9, 1537, effectively giving the abbey to Henry VIII.

This tactic worked so well that it was to be the model of the future. Frightened abbots were asked to surrender their homes to the king, and most of them agreed.

The Crumbling: In most cases, surrendered abbeys were demolished or converted into private homes. Perhaps because of its isolated location, this did not happen to Furness. The land reverted to the crown, and all precious objects were carted off and valuable lead stripped. But many of the original buildings stand today, although ravished, like sandstone skeletons. Visitors can enjoy the sight of the cloister court, church tower, infirmary, chapter house and other structures.

The Crumbling: In most cases, surrendered abbeys were demolished or converted into private homes. Perhaps because of its isolated location, this did not happen to Furness. The land reverted to the crown, and all precious objects were carted off and valuable lead stripped. But many of the original buildings stand today, although ravished, like sandstone skeletons. Visitors can enjoy the sight of the cloister court, church tower, infirmary, chapter house and other structures.

A series of families have owned the abbey property, including the Dukes of Devonshire; it is now part of the estate of the Duke of Buccleuch, the largest private landowner in the U.K.

Since the Dissolution, many have fallen in love with Furness. The ruins fired the imagination of William Wordsworth, who wrote a poem dedicated to it in 1888: "See how her ivy clasps the sacred Ruin/Fall to prevent or beautify decay/And, on the moldered walls, how bright, how gay/The flowers in pearly dews their bloom renewing!"

The Spectres: There are stories of three ghosts haunting Furness. One is of a murdered monk climbing a staircase, almost as if he were being dragged up. The second is a White Lady, drifting around the ruins as she searches for the lover who left and never returned. The third, and eeriest, is a headless monk riding a horse under one of the grand sandstone arches--perhaps one of the monks who sided with the rebels during the Pilgrimage of Grace and was punished for it.

The Preservation: Furness is an English Heritage site, and efforts are being made to prevent further collapse. Archaeological digs last year revealed the grave of a medieval abbot who, according to a newspaper report, was "a well-fed, little exercised man in his forties who suffered from arthritis and Type 2 Diabetes."

To learn more on Furness and its history, go to http://www.furnessabbey.org.uk/ and http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/furness-abbey/.

---------------------------------

"In Lone Magnificence a Ruin Stands" is contained in The Ruins of Netley Abbey by 18th century poet George Keate.

---------------------------------

This is the latest in a series devoted to the monastic ruins of England. My trilogy, The Crown, The Chalice, and The Tapestry, is set in the 1530s and early 1540s; the main character is a young Dominican novice at a priory facing destruction.

The novels are thrillers, but the framework is a serious look at Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries. I spent years researching the brutal ending of a way of life for 1,700 nuns, 3,200 monks and 1,800 friars, all expelled from their homes within a five-year period. The stone buildings themselves were confiscated by the king or given to his loyal courtiers. Many were stripped of value and demolished; some were left standing but crumbled over the centuries.

"You love faded glory," said my husband, who knows me better than anyone in the world. He's right—I feel a strong pull toward grand old houses, pallid churches, neglected cemeteries, seldom-visited landmarks. To me, few ruins are as poignant as those of an English abbey.

Furness Abbey, in the county of Cumbria, has a long and fascinating history, its dissolution marked a pivotal moment in the king's attack on the monasteries, and it is ravishingly beautiful. Oh, and according to legend it houses several ghosts. :)

Furness Abbey

King StephenThe Founding: Stephen, grandson of William the Conqueror, count of Bologne and Mortain, and later King of England during a time of chaos, established Furness in 1127. In the founding document, Stephen wrote: "That in Furness an order of regular monks be by divine permission established; which gift and offering, I, by supreme authority, appoint to be for ever observed; and, that it may remain firm and inviolate forever, I subscribe this charter with my hand and confirm it with the sign of the holy cross."

King StephenThe Founding: Stephen, grandson of William the Conqueror, count of Bologne and Mortain, and later King of England during a time of chaos, established Furness in 1127. In the founding document, Stephen wrote: "That in Furness an order of regular monks be by divine permission established; which gift and offering, I, by supreme authority, appoint to be for ever observed; and, that it may remain firm and inviolate forever, I subscribe this charter with my hand and confirm it with the sign of the holy cross."

The chosen location was a remote, narrow valley in the north of Lancashire near the coast; it was sometimes called "the vale of the deadly nightshade," because of an abundance of atropa belladonna, a beautiful plant with toxic berries. The abbey's buildings were all constructed with the vivid-colored local sandstone.

Cistercian habit

Cistercian habitThe Order: The Cistercians were founded in 1098 out of a desire to adhere more strictly to the Rules of St. Benedict. Its emphasis was on manual labor and self-sufficiency, with isolation being of great value. By 1154, there were 54 Cistercian monasteries in England, the largest were Fountains and Rievaulx abbeys in North Yorkshire ... and Furness.

The Glory: In spite of the Cistercian emphasis on austerity and contemplation, Furness grew in wealth and local influence over the next few centuries. It controlled 55,000 acres of land; its holdings included iron mines, tanneries, fisheries and mills. A close connection sprang up between the abbey and the Isle of Man, and more than one monk became Bishop of Man.

Robert the BruceBeing so close to Scotland, Furness inevitably got caught up in border tensions. When Robert the Bruce invaded England in 1322, the abbot allowed the Scottish leader to stay overnight at Furness and paid him the enormous bribe of ten thousand pounds so that the abbey would not be harmed. It worked; the marauding army moved through abbey property without laying waste to it.

Robert the BruceBeing so close to Scotland, Furness inevitably got caught up in border tensions. When Robert the Bruce invaded England in 1322, the abbot allowed the Scottish leader to stay overnight at Furness and paid him the enormous bribe of ten thousand pounds so that the abbey would not be harmed. It worked; the marauding army moved through abbey property without laying waste to it. Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion, from a 1913 painting. Note

Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion, from a 1913 painting. Notethe prominence of monks in the fervor.The Dissolution: Furness was one of the first of the kingdom's larger monasteries to fall. Its destruction is laced with irony. The Pilgrimage of Grace, a rebellion in the north of England, broke out because a great many people disagreed with the direction of the king's reforms. They wished, among other things, to preserve the monasteries that Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII's chief minister, was busy closing down.

Historians agree that the abbot of Furness in 1536, Roger Pyle, was a fearful, nervous man. When the rebellion boiled over, Pyle fled to the stronghold of the Earl of Derby, leaving his monks behind. In his absence, some of the monks contributed money to the rebels and pressured Furness tenants to do the same.

Although the rebel army outnumbered the forces of Henry VIII, they were defeated. In the mop-up, Henry VIII's anger with the Northern monasteries flipped to rage. Abbots were hanged, monks rounded up. Two of the Furness monks were imprisoned and questioned. In 1537, the king's man, the Earl of Sussex, met with Abbot Roger Pyle, his mission being to find enough wrongdoing to justify closing the abbey.

Although the rebel army outnumbered the forces of Henry VIII, they were defeated. In the mop-up, Henry VIII's anger with the Northern monasteries flipped to rage. Abbots were hanged, monks rounded up. Two of the Furness monks were imprisoned and questioned. In 1537, the king's man, the Earl of Sussex, met with Abbot Roger Pyle, his mission being to find enough wrongdoing to justify closing the abbey. But there was a problem: Abbot Pyle had shown no disloyalty. The Earl of Sussex came up with a solution that turned out to have profound consequences. He summoned the abbot to Wyland, a place where the severed heads of defiant abbots and monks were prominently posted, and then made a suggestion: The Furness abbot could surrender the abbey to the Crown and go willingly, along with the 28 innocent monks. That way, there would be no penalties or prosecutions. Abbot Pyle at once agreed, and he signed a document on April 9, 1537, effectively giving the abbey to Henry VIII.

This tactic worked so well that it was to be the model of the future. Frightened abbots were asked to surrender their homes to the king, and most of them agreed.

The Crumbling: In most cases, surrendered abbeys were demolished or converted into private homes. Perhaps because of its isolated location, this did not happen to Furness. The land reverted to the crown, and all precious objects were carted off and valuable lead stripped. But many of the original buildings stand today, although ravished, like sandstone skeletons. Visitors can enjoy the sight of the cloister court, church tower, infirmary, chapter house and other structures.

The Crumbling: In most cases, surrendered abbeys were demolished or converted into private homes. Perhaps because of its isolated location, this did not happen to Furness. The land reverted to the crown, and all precious objects were carted off and valuable lead stripped. But many of the original buildings stand today, although ravished, like sandstone skeletons. Visitors can enjoy the sight of the cloister court, church tower, infirmary, chapter house and other structures. A series of families have owned the abbey property, including the Dukes of Devonshire; it is now part of the estate of the Duke of Buccleuch, the largest private landowner in the U.K.

Since the Dissolution, many have fallen in love with Furness. The ruins fired the imagination of William Wordsworth, who wrote a poem dedicated to it in 1888: "See how her ivy clasps the sacred Ruin/Fall to prevent or beautify decay/And, on the moldered walls, how bright, how gay/The flowers in pearly dews their bloom renewing!"

The Spectres: There are stories of three ghosts haunting Furness. One is of a murdered monk climbing a staircase, almost as if he were being dragged up. The second is a White Lady, drifting around the ruins as she searches for the lover who left and never returned. The third, and eeriest, is a headless monk riding a horse under one of the grand sandstone arches--perhaps one of the monks who sided with the rebels during the Pilgrimage of Grace and was punished for it.

The Preservation: Furness is an English Heritage site, and efforts are being made to prevent further collapse. Archaeological digs last year revealed the grave of a medieval abbot who, according to a newspaper report, was "a well-fed, little exercised man in his forties who suffered from arthritis and Type 2 Diabetes."

To learn more on Furness and its history, go to http://www.furnessabbey.org.uk/ and http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/furness-abbey/.

---------------------------------

"In Lone Magnificence a Ruin Stands" is contained in The Ruins of Netley Abbey by 18th century poet George Keate.

---------------------------------

Published on November 26, 2015 08:52

October 28, 2015

Thetford Priory: Murdered Monks and a Desperate Duke

By Nancy Bilyeau

This post is one in a series on the monastic ruins of England, "In Lone Magnificence, a Ruin Stands" *

Thetford Priory

One of England's oldest ruins, Thetford's Priory of St. Mary is rich with drama. It was an East Anglian priory important to not only the Cluniac monks who lived there for 436 years but also the aristocratic family that buried their dead there. A powerful duke's struggle to protect Thetford from Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries proves just how impossible a quest that was.

The Founding: Hugh Bigod was a knight of Normandy who crossed the channel with Duke William. As one of the victors in the Battle of Hastings, Bigod reaped rewards of land and title, becoming the first Earl of Norfolk. He had at some point vowed to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. In his old age, Bigod was allowed to commute his vow to the founding of a monastery. By 1103, twelve monks arrived in Thetford, and Bigod and the new prior developed an ambitious plan. The buildings were arranged around a central cloister, enclosed by covered walkways. There was a church, dormitory, chapter house, prior's lodgings and barns.

But the eighth day after the stone-laying, Bigod died. What should have been a somber entombment of a noble patron turned into an angry dispute. The monks claimed the earl's body, saying that he should be buried in the priory as was specified in their foundation charter. But the Bishop of Norwich insisted that his cathedral, founded in 1096, had jurisdiction. The monks buried Bigod in the priory anyway; the bishop retaliated by stealing the body in the middle of the night and dragging it to Norwich.

But the eighth day after the stone-laying, Bigod died. What should have been a somber entombment of a noble patron turned into an angry dispute. The monks claimed the earl's body, saying that he should be buried in the priory as was specified in their foundation charter. But the Bishop of Norwich insisted that his cathedral, founded in 1096, had jurisdiction. The monks buried Bigod in the priory anyway; the bishop retaliated by stealing the body in the middle of the night and dragging it to Norwich.

It was the first time that a corpse was forcibly removed from Thetford Priory. It would not be the last.

Cluniac habitThe Order: The Order of Cluny formed in 10th Century Burgundy as an offshoot from the Benedictines. They were determined to follow a more rigid interpretation of the Rule of St. Benedict and to steer clear of political and military matters of the world. More than 30 Cluniac priories were established in England. Some became wealthy. Thetford's fortunes waxed and waned. In the early 14th century, the king had to take the priory into his protection because of its "poverty and indebtedness." Later the monks were able to run the house again with some efficiency.

Cluniac habitThe Order: The Order of Cluny formed in 10th Century Burgundy as an offshoot from the Benedictines. They were determined to follow a more rigid interpretation of the Rule of St. Benedict and to steer clear of political and military matters of the world. More than 30 Cluniac priories were established in England. Some became wealthy. Thetford's fortunes waxed and waned. In the early 14th century, the king had to take the priory into his protection because of its "poverty and indebtedness." Later the monks were able to run the house again with some efficiency.

The Glory: In the mid-13th century, an artisan of Thetford, suffering an illness, dreamed that the Blessed Virgian appeared and told him that he should persuade the prior to build a chapel on the north side of the church. Moved, the prior set to work on a stone Lady Chapel.

When it came time to place a statute of Mary in the chapel, the monks selected an old wooden image that had been in storage. But when they removed the statue's head to restore it, they discovered a cache of relics, including the "grave-cloths of Lazarus," along with a letter from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Thetford became a center for pilgrimages to see the statute and relics, and pilgrims claimed many cures.

The gatehouse, best-preserved structureBut the priory witnessed violence too. The second prior, Stephen, turned Thetford into "a house of debauchery" and caroused with local knights. An enraged Welsh monk stabbed the prior to death; the monk, in turn, was arrested and spent the rest of his life in the prison of Norwich Castle.

The gatehouse, best-preserved structureBut the priory witnessed violence too. The second prior, Stephen, turned Thetford into "a house of debauchery" and caroused with local knights. An enraged Welsh monk stabbed the prior to death; the monk, in turn, was arrested and spent the rest of his life in the prison of Norwich Castle.

Even more disturbing, in 1313, a riot broke out in the priory. A mob forced its way in, assaulted the prior and murdered several monks at the high altar who were trying to protect their valuables from being stolen. An inquiry in town did not reveal why such a horrific attack took place, but protection was increased for the prior and surviving monks.

The Dissolution: The Howards assumed the titles of Norfolk in 1483, when Richard III, grateful for the family's support as he seized the throne, made John Howard the 1st duke of Norfolk, in the third creation of the dukedom since the Bigods. The first duke was the commander of Richard III's vanguard at the Battle of Bosworth, and was slain alongside his king. Howard was buried in Thetford Priory.

His grandson, Thomas Howard, third duke of Norfolk, was one of the senior peers and most important councillors of Henry VIII. He was a major landholder of East Anglia, possessor of many castles and titles, a feared military commander. His first wife was a princess of the House of York; his second was the eldest daughter of the duke of Buckingham. Norfolk is today perhaps best known for being the uncle of both Queen Anne Boleyn and Queen Catherine Howard, two alluring women whom, it was said, he helped place in the king's circle.

Thomas Howard, 3rd duke of NorfolkNorfolk held conservative religious views, but that didn't stop him from eagerly taking possession of monasteries that fell during the break from Rome and the Dissolution. The king handed out fallen abbeys and their surrounding property to courtiers to strengthen their loyalty to the crown. But as more and more priories and abbeys "surrendered," the duke began to fear for Thetford.

Thomas Howard, 3rd duke of NorfolkNorfolk held conservative religious views, but that didn't stop him from eagerly taking possession of monasteries that fell during the break from Rome and the Dissolution. The king handed out fallen abbeys and their surrounding property to courtiers to strengthen their loyalty to the crown. But as more and more priories and abbeys "surrendered," the duke began to fear for Thetford.

The priory held enormous spiritual value for the Howards. In the medieval age, a person's achievements would be honored and their soul remembered if a certain number of Masses were said. If that person were buried by his heirs with care and splendor in a place of significance, then eternal peace was ensured. The first and second Howard dukes were interred in Thetford's grand church, connecting them to the earliest holders of the Norfolk titles. In 1536, the king's illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, the duke of Richmond, was buried in the church, too, since he was also the son-in-law of the duke of Norfolk and the king had ordered Howard to take charge of the funeral.

The duke of Norfolk knew Henry VIII as well as any noble could fathom the Tudor king. Howard had served his monarch with great fervor. It was Norfolk and his father who defeated the Scottish army in Flodden; more recently, the duke suppressed the Pilgrimage of Grace. Still, the king was ungrateful to those who served him, and treacherous. He was unlikely to grant the Howards favors. So in 1539, the duke formally proposed to Henry VIII that the priory be converted into a church of secular canons. This privilege has been granted to several cathedrals. If the conversion were approved, the tombs would not be disturbed. It was not all that much to ask.

Framlingham tomb of Thomas Howard, 3rd duke of NorfolkThe king agreed to Howard's plan. But in 1540, the same year Henry VIII made teenage Catherine Howard his fifth wife, which everyone assumed would make the Howard family preeminent, the king changed his mind about Thetford. It would have to be dissolved like dozens of other monastic houses--no exceptions--even though his own illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, was buried there. Upset, the duke of Norfolk had no choice but to remove the remains of the dead dukes and duchesses (Richmond too) and transferred them to the Suffolk Church of St. Michael in Framlingham.

Framlingham tomb of Thomas Howard, 3rd duke of NorfolkThe king agreed to Howard's plan. But in 1540, the same year Henry VIII made teenage Catherine Howard his fifth wife, which everyone assumed would make the Howard family preeminent, the king changed his mind about Thetford. It would have to be dissolved like dozens of other monastic houses--no exceptions--even though his own illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, was buried there. Upset, the duke of Norfolk had no choice but to remove the remains of the dead dukes and duchesses (Richmond too) and transferred them to the Suffolk Church of St. Michael in Framlingham.

When, 14 years later, Thomas Howard died, he was buried there as well.

As for the Cluniac monks of Thetford, 13 signed a deed of surrender and were ejected with pensions. The church and all other buildings of Thetford were stripped of value and began their centuries of decay.

The specters: Sightings of ghosts have been reported for years, including that of monks chanting Latin or performing acts that were somewhat more frightening. When television camera crews set up one night at the priory, though, the ghosts did not see fit to show themselves.

The preservation: Thetford is an English Heritage sight and its existing buildings--a 14th century gatehouse, many of the walls of the church and cloister, and part of the prior's lodgings--can be visited most days of the year. For more information, go to http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/thetford-priory/.

The preservation: Thetford is an English Heritage sight and its existing buildings--a 14th century gatehouse, many of the walls of the church and cloister, and part of the prior's lodgings--can be visited most days of the year. For more information, go to http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/thetford-priory/.

-----------------------------------------

"In lone magnificence a ruin stands" is contained in The Ruins of Netley Abbey, by 18th century poet George Keate.

-------------------------------------------

Nancy Bilyeau is the author of The Crown, The Chalice and The Tapestry, mysteries set in the 16th century and featuring a Catholic novice. They are published by Simon & Schuster in North America and the United Kingdom.

This post is one in a series on the monastic ruins of England, "In Lone Magnificence, a Ruin Stands" *

Thetford Priory

One of England's oldest ruins, Thetford's Priory of St. Mary is rich with drama. It was an East Anglian priory important to not only the Cluniac monks who lived there for 436 years but also the aristocratic family that buried their dead there. A powerful duke's struggle to protect Thetford from Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries proves just how impossible a quest that was.

The Founding: Hugh Bigod was a knight of Normandy who crossed the channel with Duke William. As one of the victors in the Battle of Hastings, Bigod reaped rewards of land and title, becoming the first Earl of Norfolk. He had at some point vowed to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. In his old age, Bigod was allowed to commute his vow to the founding of a monastery. By 1103, twelve monks arrived in Thetford, and Bigod and the new prior developed an ambitious plan. The buildings were arranged around a central cloister, enclosed by covered walkways. There was a church, dormitory, chapter house, prior's lodgings and barns.

But the eighth day after the stone-laying, Bigod died. What should have been a somber entombment of a noble patron turned into an angry dispute. The monks claimed the earl's body, saying that he should be buried in the priory as was specified in their foundation charter. But the Bishop of Norwich insisted that his cathedral, founded in 1096, had jurisdiction. The monks buried Bigod in the priory anyway; the bishop retaliated by stealing the body in the middle of the night and dragging it to Norwich.

But the eighth day after the stone-laying, Bigod died. What should have been a somber entombment of a noble patron turned into an angry dispute. The monks claimed the earl's body, saying that he should be buried in the priory as was specified in their foundation charter. But the Bishop of Norwich insisted that his cathedral, founded in 1096, had jurisdiction. The monks buried Bigod in the priory anyway; the bishop retaliated by stealing the body in the middle of the night and dragging it to Norwich.It was the first time that a corpse was forcibly removed from Thetford Priory. It would not be the last.

Cluniac habitThe Order: The Order of Cluny formed in 10th Century Burgundy as an offshoot from the Benedictines. They were determined to follow a more rigid interpretation of the Rule of St. Benedict and to steer clear of political and military matters of the world. More than 30 Cluniac priories were established in England. Some became wealthy. Thetford's fortunes waxed and waned. In the early 14th century, the king had to take the priory into his protection because of its "poverty and indebtedness." Later the monks were able to run the house again with some efficiency.

Cluniac habitThe Order: The Order of Cluny formed in 10th Century Burgundy as an offshoot from the Benedictines. They were determined to follow a more rigid interpretation of the Rule of St. Benedict and to steer clear of political and military matters of the world. More than 30 Cluniac priories were established in England. Some became wealthy. Thetford's fortunes waxed and waned. In the early 14th century, the king had to take the priory into his protection because of its "poverty and indebtedness." Later the monks were able to run the house again with some efficiency.The Glory: In the mid-13th century, an artisan of Thetford, suffering an illness, dreamed that the Blessed Virgian appeared and told him that he should persuade the prior to build a chapel on the north side of the church. Moved, the prior set to work on a stone Lady Chapel.

When it came time to place a statute of Mary in the chapel, the monks selected an old wooden image that had been in storage. But when they removed the statue's head to restore it, they discovered a cache of relics, including the "grave-cloths of Lazarus," along with a letter from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Thetford became a center for pilgrimages to see the statute and relics, and pilgrims claimed many cures.

The gatehouse, best-preserved structureBut the priory witnessed violence too. The second prior, Stephen, turned Thetford into "a house of debauchery" and caroused with local knights. An enraged Welsh monk stabbed the prior to death; the monk, in turn, was arrested and spent the rest of his life in the prison of Norwich Castle.