Nancy Bilyeau's Blog, page 20

November 26, 2015

Furness Abbey: From Glory to Ghost-Haunted Ruins

By Nancy Bilyeau

This is the latest in a series devoted to the monastic ruins of England. My trilogy, The Crown, The Chalice, and The Tapestry, is set in the 1530s and early 1540s; the main character is a young Dominican novice at a priory facing destruction.

The novels are thrillers, but the framework is a serious look at Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries. I spent years researching the brutal ending of a way of life for 1,700 nuns, 3,200 monks and 1,800 friars, all expelled from their homes within a five-year period. The stone buildings themselves were confiscated by the king or given to his loyal courtiers. Many were stripped of value and demolished; some were left standing but crumbled over the centuries.

"You love faded glory," said my husband, who knows me better than anyone in the world. He's right—I feel a strong pull toward grand old houses, pallid churches, neglected cemeteries, seldom-visited landmarks. To me, few ruins are as poignant as those of an English abbey.

Furness Abbey, in the county of Cumbria, has a long and fascinating history, its dissolution marked a pivotal moment in the king's attack on the monasteries, and it is ravishingly beautiful. Oh, and according to legend it houses several ghosts. :)

Furness Abbey

King StephenThe Founding: Stephen, grandson of William the Conqueror, count of Bologne and Mortain, and later King of England during a time of chaos, established Furness in 1127. In the founding document, Stephen wrote: "That in Furness an order of regular monks be by divine permission established; which gift and offering, I, by supreme authority, appoint to be for ever observed; and, that it may remain firm and inviolate forever, I subscribe this charter with my hand and confirm it with the sign of the holy cross."

King StephenThe Founding: Stephen, grandson of William the Conqueror, count of Bologne and Mortain, and later King of England during a time of chaos, established Furness in 1127. In the founding document, Stephen wrote: "That in Furness an order of regular monks be by divine permission established; which gift and offering, I, by supreme authority, appoint to be for ever observed; and, that it may remain firm and inviolate forever, I subscribe this charter with my hand and confirm it with the sign of the holy cross."

The chosen location was a remote, narrow valley in the north of Lancashire near the coast; it was sometimes called "the vale of the deadly nightshade," because of an abundance of atropa belladonna, a beautiful plant with toxic berries. The abbey's buildings were all constructed with the vivid-colored local sandstone.

Cistercian habit

Cistercian habit

The Order: The Cistercians were founded in 1098 out of a desire to adhere more strictly to the Rules of St. Benedict. Its emphasis was on manual labor and self-sufficiency, with isolation being of great value. By 1154, there were 54 Cistercian monasteries in England, the largest were Fountains and Rievaulx abbeys in North Yorkshire ... and Furness.

The Glory: In spite of the Cistercian emphasis on austerity and contemplation, Furness grew in wealth and local influence over the next few centuries. It controlled 55,000 acres of land; its holdings included iron mines, tanneries, fisheries and mills. A close connection sprang up between the abbey and the Isle of Man, and more than one monk became Bishop of Man.

Robert the BruceBeing so close to Scotland, Furness inevitably got caught up in border tensions. When Robert the Bruce invaded England in 1322, the abbot allowed the Scottish leader to stay overnight at Furness and paid him the enormous bribe of ten thousand pounds so that the abbey would not be harmed. It worked; the marauding army moved through abbey property without laying waste to it.

Robert the BruceBeing so close to Scotland, Furness inevitably got caught up in border tensions. When Robert the Bruce invaded England in 1322, the abbot allowed the Scottish leader to stay overnight at Furness and paid him the enormous bribe of ten thousand pounds so that the abbey would not be harmed. It worked; the marauding army moved through abbey property without laying waste to it.

Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion, from a 1913 painting. Note

Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion, from a 1913 painting. Note

the prominence of monks in the fervor.The Dissolution: Furness was one of the first of the kingdom's larger monasteries to fall. Its destruction is laced with irony. The Pilgrimage of Grace, a rebellion in the north of England, broke out because a great many people disagreed with the direction of the king's reforms. They wished, among other things, to preserve the monasteries that Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII's chief minister, was busy closing down.

Historians agree that the abbot of Furness in 1536, Roger Pyle, was a fearful, nervous man. When the rebellion boiled over, Pyle fled to the stronghold of the Earl of Derby, leaving his monks behind. In his absence, some of the monks contributed money to the rebels and pressured Furness tenants to do the same.

Although the rebel army outnumbered the forces of Henry VIII, they were defeated. In the mop-up, Henry VIII's anger with the Northern monasteries flipped to rage. Abbots were hanged, monks rounded up. Two of the Furness monks were imprisoned and questioned. In 1537, the king's man, the Earl of Sussex, met with Abbot Roger Pyle, his mission being to find enough wrongdoing to justify closing the abbey.

Although the rebel army outnumbered the forces of Henry VIII, they were defeated. In the mop-up, Henry VIII's anger with the Northern monasteries flipped to rage. Abbots were hanged, monks rounded up. Two of the Furness monks were imprisoned and questioned. In 1537, the king's man, the Earl of Sussex, met with Abbot Roger Pyle, his mission being to find enough wrongdoing to justify closing the abbey.

But there was a problem: Abbot Pyle had shown no disloyalty. The Earl of Sussex came up with a solution that turned out to have profound consequences. He summoned the abbot to Wyland, a place where the severed heads of defiant abbots and monks were prominently posted, and then made a suggestion: The Furness abbot could surrender the abbey to the Crown and go willingly, along with the 28 innocent monks. That way, there would be no penalties or prosecutions. Abbot Pyle at once agreed, and he signed a document on April 9, 1537, effectively giving the abbey to Henry VIII.

This tactic worked so well that it was to be the model of the future. Frightened abbots were asked to surrender their homes to the king, and most of them agreed.

The Crumbling: In most cases, surrendered abbeys were demolished or converted into private homes. Perhaps because of its isolated location, this did not happen to Furness. The land reverted to the crown, and all precious objects were carted off and valuable lead stripped. But many of the original buildings stand today, although ravished, like sandstone skeletons. Visitors can enjoy the sight of the cloister court, church tower, infirmary, chapter house and other structures.

The Crumbling: In most cases, surrendered abbeys were demolished or converted into private homes. Perhaps because of its isolated location, this did not happen to Furness. The land reverted to the crown, and all precious objects were carted off and valuable lead stripped. But many of the original buildings stand today, although ravished, like sandstone skeletons. Visitors can enjoy the sight of the cloister court, church tower, infirmary, chapter house and other structures.

A series of families have owned the abbey property, including the Dukes of Devonshire; it is now part of the estate of the Duke of Buccleuch, the largest private landowner in the U.K.

Since the Dissolution, many have fallen in love with Furness. The ruins fired the imagination of William Wordsworth, who wrote a poem dedicated to it in 1888: "See how her ivy clasps the sacred Ruin/Fall to prevent or beautify decay/And, on the moldered walls, how bright, how gay/The flowers in pearly dews their bloom renewing!"

The Spectres: There are stories of three ghosts haunting Furness. One is of a murdered monk climbing a staircase, almost as if he were being dragged up. The second is a White Lady, drifting around the ruins as she searches for the lover who left and never returned. The third, and eeriest, is a headless monk riding a horse under one of the grand sandstone arches--perhaps one of the monks who sided with the rebels during the Pilgrimage of Grace and was punished for it.

The Preservation: Furness is an English Heritage site, and efforts are being made to prevent further collapse. Archaeological digs last year revealed the grave of a medieval abbot who, according to a newspaper report, was "a well-fed, little exercised man in his forties who suffered from arthritis and Type 2 Diabetes."

To learn more on Furness and its history, go to http://www.furnessabbey.org.uk/ and http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/furness-abbey/.

---------------------------------

"In Lone Magnificence a Ruin Stands" is contained in The Ruins of Netley Abbey by 18th century poet George Keate.

---------------------------------

This is the latest in a series devoted to the monastic ruins of England. My trilogy, The Crown, The Chalice, and The Tapestry, is set in the 1530s and early 1540s; the main character is a young Dominican novice at a priory facing destruction.

The novels are thrillers, but the framework is a serious look at Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries. I spent years researching the brutal ending of a way of life for 1,700 nuns, 3,200 monks and 1,800 friars, all expelled from their homes within a five-year period. The stone buildings themselves were confiscated by the king or given to his loyal courtiers. Many were stripped of value and demolished; some were left standing but crumbled over the centuries.

"You love faded glory," said my husband, who knows me better than anyone in the world. He's right—I feel a strong pull toward grand old houses, pallid churches, neglected cemeteries, seldom-visited landmarks. To me, few ruins are as poignant as those of an English abbey.

Furness Abbey, in the county of Cumbria, has a long and fascinating history, its dissolution marked a pivotal moment in the king's attack on the monasteries, and it is ravishingly beautiful. Oh, and according to legend it houses several ghosts. :)

Furness Abbey

King StephenThe Founding: Stephen, grandson of William the Conqueror, count of Bologne and Mortain, and later King of England during a time of chaos, established Furness in 1127. In the founding document, Stephen wrote: "That in Furness an order of regular monks be by divine permission established; which gift and offering, I, by supreme authority, appoint to be for ever observed; and, that it may remain firm and inviolate forever, I subscribe this charter with my hand and confirm it with the sign of the holy cross."

King StephenThe Founding: Stephen, grandson of William the Conqueror, count of Bologne and Mortain, and later King of England during a time of chaos, established Furness in 1127. In the founding document, Stephen wrote: "That in Furness an order of regular monks be by divine permission established; which gift and offering, I, by supreme authority, appoint to be for ever observed; and, that it may remain firm and inviolate forever, I subscribe this charter with my hand and confirm it with the sign of the holy cross."

The chosen location was a remote, narrow valley in the north of Lancashire near the coast; it was sometimes called "the vale of the deadly nightshade," because of an abundance of atropa belladonna, a beautiful plant with toxic berries. The abbey's buildings were all constructed with the vivid-colored local sandstone.

Cistercian habit

Cistercian habitThe Order: The Cistercians were founded in 1098 out of a desire to adhere more strictly to the Rules of St. Benedict. Its emphasis was on manual labor and self-sufficiency, with isolation being of great value. By 1154, there were 54 Cistercian monasteries in England, the largest were Fountains and Rievaulx abbeys in North Yorkshire ... and Furness.

The Glory: In spite of the Cistercian emphasis on austerity and contemplation, Furness grew in wealth and local influence over the next few centuries. It controlled 55,000 acres of land; its holdings included iron mines, tanneries, fisheries and mills. A close connection sprang up between the abbey and the Isle of Man, and more than one monk became Bishop of Man.

Robert the BruceBeing so close to Scotland, Furness inevitably got caught up in border tensions. When Robert the Bruce invaded England in 1322, the abbot allowed the Scottish leader to stay overnight at Furness and paid him the enormous bribe of ten thousand pounds so that the abbey would not be harmed. It worked; the marauding army moved through abbey property without laying waste to it.

Robert the BruceBeing so close to Scotland, Furness inevitably got caught up in border tensions. When Robert the Bruce invaded England in 1322, the abbot allowed the Scottish leader to stay overnight at Furness and paid him the enormous bribe of ten thousand pounds so that the abbey would not be harmed. It worked; the marauding army moved through abbey property without laying waste to it. Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion, from a 1913 painting. Note

Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion, from a 1913 painting. Notethe prominence of monks in the fervor.The Dissolution: Furness was one of the first of the kingdom's larger monasteries to fall. Its destruction is laced with irony. The Pilgrimage of Grace, a rebellion in the north of England, broke out because a great many people disagreed with the direction of the king's reforms. They wished, among other things, to preserve the monasteries that Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII's chief minister, was busy closing down.

Historians agree that the abbot of Furness in 1536, Roger Pyle, was a fearful, nervous man. When the rebellion boiled over, Pyle fled to the stronghold of the Earl of Derby, leaving his monks behind. In his absence, some of the monks contributed money to the rebels and pressured Furness tenants to do the same.

Although the rebel army outnumbered the forces of Henry VIII, they were defeated. In the mop-up, Henry VIII's anger with the Northern monasteries flipped to rage. Abbots were hanged, monks rounded up. Two of the Furness monks were imprisoned and questioned. In 1537, the king's man, the Earl of Sussex, met with Abbot Roger Pyle, his mission being to find enough wrongdoing to justify closing the abbey.

Although the rebel army outnumbered the forces of Henry VIII, they were defeated. In the mop-up, Henry VIII's anger with the Northern monasteries flipped to rage. Abbots were hanged, monks rounded up. Two of the Furness monks were imprisoned and questioned. In 1537, the king's man, the Earl of Sussex, met with Abbot Roger Pyle, his mission being to find enough wrongdoing to justify closing the abbey. But there was a problem: Abbot Pyle had shown no disloyalty. The Earl of Sussex came up with a solution that turned out to have profound consequences. He summoned the abbot to Wyland, a place where the severed heads of defiant abbots and monks were prominently posted, and then made a suggestion: The Furness abbot could surrender the abbey to the Crown and go willingly, along with the 28 innocent monks. That way, there would be no penalties or prosecutions. Abbot Pyle at once agreed, and he signed a document on April 9, 1537, effectively giving the abbey to Henry VIII.

This tactic worked so well that it was to be the model of the future. Frightened abbots were asked to surrender their homes to the king, and most of them agreed.

The Crumbling: In most cases, surrendered abbeys were demolished or converted into private homes. Perhaps because of its isolated location, this did not happen to Furness. The land reverted to the crown, and all precious objects were carted off and valuable lead stripped. But many of the original buildings stand today, although ravished, like sandstone skeletons. Visitors can enjoy the sight of the cloister court, church tower, infirmary, chapter house and other structures.

The Crumbling: In most cases, surrendered abbeys were demolished or converted into private homes. Perhaps because of its isolated location, this did not happen to Furness. The land reverted to the crown, and all precious objects were carted off and valuable lead stripped. But many of the original buildings stand today, although ravished, like sandstone skeletons. Visitors can enjoy the sight of the cloister court, church tower, infirmary, chapter house and other structures. A series of families have owned the abbey property, including the Dukes of Devonshire; it is now part of the estate of the Duke of Buccleuch, the largest private landowner in the U.K.

Since the Dissolution, many have fallen in love with Furness. The ruins fired the imagination of William Wordsworth, who wrote a poem dedicated to it in 1888: "See how her ivy clasps the sacred Ruin/Fall to prevent or beautify decay/And, on the moldered walls, how bright, how gay/The flowers in pearly dews their bloom renewing!"

The Spectres: There are stories of three ghosts haunting Furness. One is of a murdered monk climbing a staircase, almost as if he were being dragged up. The second is a White Lady, drifting around the ruins as she searches for the lover who left and never returned. The third, and eeriest, is a headless monk riding a horse under one of the grand sandstone arches--perhaps one of the monks who sided with the rebels during the Pilgrimage of Grace and was punished for it.

The Preservation: Furness is an English Heritage site, and efforts are being made to prevent further collapse. Archaeological digs last year revealed the grave of a medieval abbot who, according to a newspaper report, was "a well-fed, little exercised man in his forties who suffered from arthritis and Type 2 Diabetes."

To learn more on Furness and its history, go to http://www.furnessabbey.org.uk/ and http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/furness-abbey/.

---------------------------------

"In Lone Magnificence a Ruin Stands" is contained in The Ruins of Netley Abbey by 18th century poet George Keate.

---------------------------------

Published on November 26, 2015 08:52

October 28, 2015

Thetford Priory: Murdered Monks and a Desperate Duke

By Nancy Bilyeau

This post is one in a series on the monastic ruins of England, "In Lone Magnificence, a Ruin Stands" *

Thetford Priory

One of England's oldest ruins, Thetford's Priory of St. Mary is rich with drama. It was an East Anglian priory important to not only the Cluniac monks who lived there for 436 years but also the aristocratic family that buried their dead there. A powerful duke's struggle to protect Thetford from Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries proves just how impossible a quest that was.

The Founding: Hugh Bigod was a knight of Normandy who crossed the channel with Duke William. As one of the victors in the Battle of Hastings, Bigod reaped rewards of land and title, becoming the first Earl of Norfolk. He had at some point vowed to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. In his old age, Bigod was allowed to commute his vow to the founding of a monastery. By 1103, twelve monks arrived in Thetford, and Bigod and the new prior developed an ambitious plan. The buildings were arranged around a central cloister, enclosed by covered walkways. There was a church, dormitory, chapter house, prior's lodgings and barns.

But the eighth day after the stone-laying, Bigod died. What should have been a somber entombment of a noble patron turned into an angry dispute. The monks claimed the earl's body, saying that he should be buried in the priory as was specified in their foundation charter. But the Bishop of Norwich insisted that his cathedral, founded in 1096, had jurisdiction. The monks buried Bigod in the priory anyway; the bishop retaliated by stealing the body in the middle of the night and dragging it to Norwich.

But the eighth day after the stone-laying, Bigod died. What should have been a somber entombment of a noble patron turned into an angry dispute. The monks claimed the earl's body, saying that he should be buried in the priory as was specified in their foundation charter. But the Bishop of Norwich insisted that his cathedral, founded in 1096, had jurisdiction. The monks buried Bigod in the priory anyway; the bishop retaliated by stealing the body in the middle of the night and dragging it to Norwich.

It was the first time that a corpse was forcibly removed from Thetford Priory. It would not be the last.

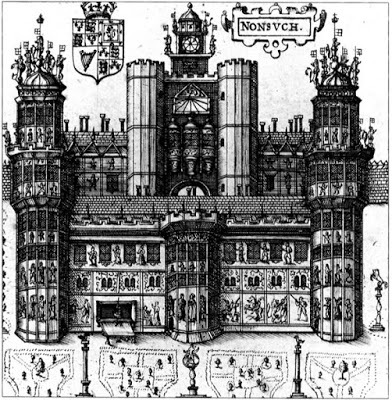

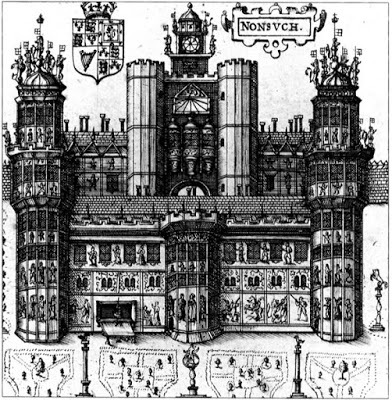

Cluniac habitThe Order: The Order of Cluny formed in 10th Century Burgundy as an offshoot from the Benedictines. They were determined to follow a more rigid interpretation of the Rule of St. Benedict and to steer clear of political and military matters of the world. More than 30 Cluniac priories were established in England. Some became wealthy. Thetford's fortunes waxed and waned. In the early 14th century, the king had to take the priory into his protection because of its "poverty and indebtedness." Later the monks were able to run the house again with some efficiency.

Cluniac habitThe Order: The Order of Cluny formed in 10th Century Burgundy as an offshoot from the Benedictines. They were determined to follow a more rigid interpretation of the Rule of St. Benedict and to steer clear of political and military matters of the world. More than 30 Cluniac priories were established in England. Some became wealthy. Thetford's fortunes waxed and waned. In the early 14th century, the king had to take the priory into his protection because of its "poverty and indebtedness." Later the monks were able to run the house again with some efficiency.

The Glory: In the mid-13th century, an artisan of Thetford, suffering an illness, dreamed that the Blessed Virgian appeared and told him that he should persuade the prior to build a chapel on the north side of the church. Moved, the prior set to work on a stone Lady Chapel.

When it came time to place a statute of Mary in the chapel, the monks selected an old wooden image that had been in storage. But when they removed the statue's head to restore it, they discovered a cache of relics, including the "grave-cloths of Lazarus," along with a letter from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Thetford became a center for pilgrimages to see the statute and relics, and pilgrims claimed many cures.

The gatehouse, best-preserved structureBut the priory witnessed violence too. The second prior, Stephen, turned Thetford into "a house of debauchery" and caroused with local knights. An enraged Welsh monk stabbed the prior to death; the monk, in turn, was arrested and spent the rest of his life in the prison of Norwich Castle.

The gatehouse, best-preserved structureBut the priory witnessed violence too. The second prior, Stephen, turned Thetford into "a house of debauchery" and caroused with local knights. An enraged Welsh monk stabbed the prior to death; the monk, in turn, was arrested and spent the rest of his life in the prison of Norwich Castle.

Even more disturbing, in 1313, a riot broke out in the priory. A mob forced its way in, assaulted the prior and murdered several monks at the high altar who were trying to protect their valuables from being stolen. An inquiry in town did not reveal why such a horrific attack took place, but protection was increased for the prior and surviving monks.

The Dissolution: The Howards assumed the titles of Norfolk in 1483, when Richard III, grateful for the family's support as he seized the throne, made John Howard the 1st duke of Norfolk, in the third creation of the dukedom since the Bigods. The first duke was the commander of Richard III's vanguard at the Battle of Bosworth, and was slain alongside his king. Howard was buried in Thetford Priory.

His grandson, Thomas Howard, third duke of Norfolk, was one of the senior peers and most important councillors of Henry VIII. He was a major landholder of East Anglia, possessor of many castles and titles, a feared military commander. His first wife was a princess of the House of York; his second was the eldest daughter of the duke of Buckingham. Norfolk is today perhaps best known for being the uncle of both Queen Anne Boleyn and Queen Catherine Howard, two alluring women whom, it was said, he helped place in the king's circle.

Thomas Howard, 3rd duke of NorfolkNorfolk held conservative religious views, but that didn't stop him from eagerly taking possession of monasteries that fell during the break from Rome and the Dissolution. The king handed out fallen abbeys and their surrounding property to courtiers to strengthen their loyalty to the crown. But as more and more priories and abbeys "surrendered," the duke began to fear for Thetford.

Thomas Howard, 3rd duke of NorfolkNorfolk held conservative religious views, but that didn't stop him from eagerly taking possession of monasteries that fell during the break from Rome and the Dissolution. The king handed out fallen abbeys and their surrounding property to courtiers to strengthen their loyalty to the crown. But as more and more priories and abbeys "surrendered," the duke began to fear for Thetford.

The priory held enormous spiritual value for the Howards. In the medieval age, a person's achievements would be honored and their soul remembered if a certain number of Masses were said. If that person were buried by his heirs with care and splendor in a place of significance, then eternal peace was ensured. The first and second Howard dukes were interred in Thetford's grand church, connecting them to the earliest holders of the Norfolk titles. In 1536, the king's illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, the duke of Richmond, was buried in the church, too, since he was also the son-in-law of the duke of Norfolk and the king had ordered Howard to take charge of the funeral.

The duke of Norfolk knew Henry VIII as well as any noble could fathom the Tudor king. Howard had served his monarch with great fervor. It was Norfolk and his father who defeated the Scottish army in Flodden; more recently, the duke suppressed the Pilgrimage of Grace. Still, the king was ungrateful to those who served him, and treacherous. He was unlikely to grant the Howards favors. So in 1539, the duke formally proposed to Henry VIII that the priory be converted into a church of secular canons. This privilege has been granted to several cathedrals. If the conversion were approved, the tombs would not be disturbed. It was not all that much to ask.

Framlingham tomb of Thomas Howard, 3rd duke of NorfolkThe king agreed to Howard's plan. But in 1540, the same year Henry VIII made teenage Catherine Howard his fifth wife, which everyone assumed would make the Howard family preeminent, the king changed his mind about Thetford. It would have to be dissolved like dozens of other monastic houses--no exceptions--even though his own illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, was buried there. Upset, the duke of Norfolk had no choice but to remove the remains of the dead dukes and duchesses (Richmond too) and transferred them to the Suffolk Church of St. Michael in Framlingham.

Framlingham tomb of Thomas Howard, 3rd duke of NorfolkThe king agreed to Howard's plan. But in 1540, the same year Henry VIII made teenage Catherine Howard his fifth wife, which everyone assumed would make the Howard family preeminent, the king changed his mind about Thetford. It would have to be dissolved like dozens of other monastic houses--no exceptions--even though his own illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, was buried there. Upset, the duke of Norfolk had no choice but to remove the remains of the dead dukes and duchesses (Richmond too) and transferred them to the Suffolk Church of St. Michael in Framlingham.

When, 14 years later, Thomas Howard died, he was buried there as well.

As for the Cluniac monks of Thetford, 13 signed a deed of surrender and were ejected with pensions. The church and all other buildings of Thetford were stripped of value and began their centuries of decay.

The specters: Sightings of ghosts have been reported for years, including that of monks chanting Latin or performing acts that were somewhat more frightening. When television camera crews set up one night at the priory, though, the ghosts did not see fit to show themselves.

The preservation: Thetford is an English Heritage sight and its existing buildings--a 14th century gatehouse, many of the walls of the church and cloister, and part of the prior's lodgings--can be visited most days of the year. For more information, go to http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/thetford-priory/.

The preservation: Thetford is an English Heritage sight and its existing buildings--a 14th century gatehouse, many of the walls of the church and cloister, and part of the prior's lodgings--can be visited most days of the year. For more information, go to http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/thetford-priory/.

-----------------------------------------

"In lone magnificence a ruin stands" is contained in The Ruins of Netley Abbey, by 18th century poet George Keate.

-------------------------------------------

Nancy Bilyeau is the author of The Crown, The Chalice and The Tapestry, mysteries set in the 16th century and featuring a Catholic novice. They are published by Simon & Schuster in North America and the United Kingdom.

This post is one in a series on the monastic ruins of England, "In Lone Magnificence, a Ruin Stands" *

Thetford Priory

One of England's oldest ruins, Thetford's Priory of St. Mary is rich with drama. It was an East Anglian priory important to not only the Cluniac monks who lived there for 436 years but also the aristocratic family that buried their dead there. A powerful duke's struggle to protect Thetford from Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries proves just how impossible a quest that was.

The Founding: Hugh Bigod was a knight of Normandy who crossed the channel with Duke William. As one of the victors in the Battle of Hastings, Bigod reaped rewards of land and title, becoming the first Earl of Norfolk. He had at some point vowed to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. In his old age, Bigod was allowed to commute his vow to the founding of a monastery. By 1103, twelve monks arrived in Thetford, and Bigod and the new prior developed an ambitious plan. The buildings were arranged around a central cloister, enclosed by covered walkways. There was a church, dormitory, chapter house, prior's lodgings and barns.

But the eighth day after the stone-laying, Bigod died. What should have been a somber entombment of a noble patron turned into an angry dispute. The monks claimed the earl's body, saying that he should be buried in the priory as was specified in their foundation charter. But the Bishop of Norwich insisted that his cathedral, founded in 1096, had jurisdiction. The monks buried Bigod in the priory anyway; the bishop retaliated by stealing the body in the middle of the night and dragging it to Norwich.

But the eighth day after the stone-laying, Bigod died. What should have been a somber entombment of a noble patron turned into an angry dispute. The monks claimed the earl's body, saying that he should be buried in the priory as was specified in their foundation charter. But the Bishop of Norwich insisted that his cathedral, founded in 1096, had jurisdiction. The monks buried Bigod in the priory anyway; the bishop retaliated by stealing the body in the middle of the night and dragging it to Norwich.It was the first time that a corpse was forcibly removed from Thetford Priory. It would not be the last.

Cluniac habitThe Order: The Order of Cluny formed in 10th Century Burgundy as an offshoot from the Benedictines. They were determined to follow a more rigid interpretation of the Rule of St. Benedict and to steer clear of political and military matters of the world. More than 30 Cluniac priories were established in England. Some became wealthy. Thetford's fortunes waxed and waned. In the early 14th century, the king had to take the priory into his protection because of its "poverty and indebtedness." Later the monks were able to run the house again with some efficiency.

Cluniac habitThe Order: The Order of Cluny formed in 10th Century Burgundy as an offshoot from the Benedictines. They were determined to follow a more rigid interpretation of the Rule of St. Benedict and to steer clear of political and military matters of the world. More than 30 Cluniac priories were established in England. Some became wealthy. Thetford's fortunes waxed and waned. In the early 14th century, the king had to take the priory into his protection because of its "poverty and indebtedness." Later the monks were able to run the house again with some efficiency.The Glory: In the mid-13th century, an artisan of Thetford, suffering an illness, dreamed that the Blessed Virgian appeared and told him that he should persuade the prior to build a chapel on the north side of the church. Moved, the prior set to work on a stone Lady Chapel.

When it came time to place a statute of Mary in the chapel, the monks selected an old wooden image that had been in storage. But when they removed the statue's head to restore it, they discovered a cache of relics, including the "grave-cloths of Lazarus," along with a letter from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Thetford became a center for pilgrimages to see the statute and relics, and pilgrims claimed many cures.

The gatehouse, best-preserved structureBut the priory witnessed violence too. The second prior, Stephen, turned Thetford into "a house of debauchery" and caroused with local knights. An enraged Welsh monk stabbed the prior to death; the monk, in turn, was arrested and spent the rest of his life in the prison of Norwich Castle.

The gatehouse, best-preserved structureBut the priory witnessed violence too. The second prior, Stephen, turned Thetford into "a house of debauchery" and caroused with local knights. An enraged Welsh monk stabbed the prior to death; the monk, in turn, was arrested and spent the rest of his life in the prison of Norwich Castle.Even more disturbing, in 1313, a riot broke out in the priory. A mob forced its way in, assaulted the prior and murdered several monks at the high altar who were trying to protect their valuables from being stolen. An inquiry in town did not reveal why such a horrific attack took place, but protection was increased for the prior and surviving monks.

The Dissolution: The Howards assumed the titles of Norfolk in 1483, when Richard III, grateful for the family's support as he seized the throne, made John Howard the 1st duke of Norfolk, in the third creation of the dukedom since the Bigods. The first duke was the commander of Richard III's vanguard at the Battle of Bosworth, and was slain alongside his king. Howard was buried in Thetford Priory.

His grandson, Thomas Howard, third duke of Norfolk, was one of the senior peers and most important councillors of Henry VIII. He was a major landholder of East Anglia, possessor of many castles and titles, a feared military commander. His first wife was a princess of the House of York; his second was the eldest daughter of the duke of Buckingham. Norfolk is today perhaps best known for being the uncle of both Queen Anne Boleyn and Queen Catherine Howard, two alluring women whom, it was said, he helped place in the king's circle.

Thomas Howard, 3rd duke of NorfolkNorfolk held conservative religious views, but that didn't stop him from eagerly taking possession of monasteries that fell during the break from Rome and the Dissolution. The king handed out fallen abbeys and their surrounding property to courtiers to strengthen their loyalty to the crown. But as more and more priories and abbeys "surrendered," the duke began to fear for Thetford.

Thomas Howard, 3rd duke of NorfolkNorfolk held conservative religious views, but that didn't stop him from eagerly taking possession of monasteries that fell during the break from Rome and the Dissolution. The king handed out fallen abbeys and their surrounding property to courtiers to strengthen their loyalty to the crown. But as more and more priories and abbeys "surrendered," the duke began to fear for Thetford.The priory held enormous spiritual value for the Howards. In the medieval age, a person's achievements would be honored and their soul remembered if a certain number of Masses were said. If that person were buried by his heirs with care and splendor in a place of significance, then eternal peace was ensured. The first and second Howard dukes were interred in Thetford's grand church, connecting them to the earliest holders of the Norfolk titles. In 1536, the king's illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, the duke of Richmond, was buried in the church, too, since he was also the son-in-law of the duke of Norfolk and the king had ordered Howard to take charge of the funeral.

The duke of Norfolk knew Henry VIII as well as any noble could fathom the Tudor king. Howard had served his monarch with great fervor. It was Norfolk and his father who defeated the Scottish army in Flodden; more recently, the duke suppressed the Pilgrimage of Grace. Still, the king was ungrateful to those who served him, and treacherous. He was unlikely to grant the Howards favors. So in 1539, the duke formally proposed to Henry VIII that the priory be converted into a church of secular canons. This privilege has been granted to several cathedrals. If the conversion were approved, the tombs would not be disturbed. It was not all that much to ask.

Framlingham tomb of Thomas Howard, 3rd duke of NorfolkThe king agreed to Howard's plan. But in 1540, the same year Henry VIII made teenage Catherine Howard his fifth wife, which everyone assumed would make the Howard family preeminent, the king changed his mind about Thetford. It would have to be dissolved like dozens of other monastic houses--no exceptions--even though his own illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, was buried there. Upset, the duke of Norfolk had no choice but to remove the remains of the dead dukes and duchesses (Richmond too) and transferred them to the Suffolk Church of St. Michael in Framlingham.

Framlingham tomb of Thomas Howard, 3rd duke of NorfolkThe king agreed to Howard's plan. But in 1540, the same year Henry VIII made teenage Catherine Howard his fifth wife, which everyone assumed would make the Howard family preeminent, the king changed his mind about Thetford. It would have to be dissolved like dozens of other monastic houses--no exceptions--even though his own illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, was buried there. Upset, the duke of Norfolk had no choice but to remove the remains of the dead dukes and duchesses (Richmond too) and transferred them to the Suffolk Church of St. Michael in Framlingham.When, 14 years later, Thomas Howard died, he was buried there as well.

As for the Cluniac monks of Thetford, 13 signed a deed of surrender and were ejected with pensions. The church and all other buildings of Thetford were stripped of value and began their centuries of decay.

The specters: Sightings of ghosts have been reported for years, including that of monks chanting Latin or performing acts that were somewhat more frightening. When television camera crews set up one night at the priory, though, the ghosts did not see fit to show themselves.

The preservation: Thetford is an English Heritage sight and its existing buildings--a 14th century gatehouse, many of the walls of the church and cloister, and part of the prior's lodgings--can be visited most days of the year. For more information, go to http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/thetford-priory/.

The preservation: Thetford is an English Heritage sight and its existing buildings--a 14th century gatehouse, many of the walls of the church and cloister, and part of the prior's lodgings--can be visited most days of the year. For more information, go to http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/thetford-priory/.-----------------------------------------

"In lone magnificence a ruin stands" is contained in The Ruins of Netley Abbey, by 18th century poet George Keate.

-------------------------------------------

Nancy Bilyeau is the author of The Crown, The Chalice and The Tapestry, mysteries set in the 16th century and featuring a Catholic novice. They are published by Simon & Schuster in North America and the United Kingdom.

Published on October 28, 2015 03:33

September 29, 2015

What was the Life of a Medieval Nun?

By Nancy Bilyeau

This blog post is part of a blog hop to celebrate the publication of Castles, Customs, and Kings: True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors, Volume 2. Details at the end of the post.

Anyone who writes historical fiction acts as a time traveler. What was life like for our characters? How much an author tries to enter the mind of a person who lived centuries ago depends on the author--and the subject. When it comes to lives of long ago, their thoughts and desires and expectations, some of the people seem like us, just wearing different clothes and eating different food.

But then there are the late-medieval Dominican nuns. And they are not much like us.

While researching the history of the Dartford Priory for my trilogy of mysteries, I found myself intrigued, awed, puzzled and impressed by the nuns who lived within the cloister walls. The sole nunnery for Dominican sisters opened its doors in 1372 and was demolished by order of Henry VIII in 1538. It was one of the twenty wealthiest priories in the kingdom, with nuns whose families came from the local gentry, the aristocracy and even royalty. Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville's youngest daughter, Bridget, lived and died at Dartford. But while the priory owned a great deal of property, to provide for both the nuns and the friars at a nearby Dominican order, the women's existences were humble.

Their lives were ruled by custom--by religious doctrine set by the Dominican Order and adhered to meticulously. The sisters took vows of poverty, chastity, charity, and obedience. Dartford was an enclosed order, meaning the women could not leave. The doors were locked from the outside every night. They had chosen to live apart from the world.

Allow me to share just a few other aspects of what would have been expected of Sister Joanna, the protagonist of my series of historical mysteries.

They prayed more than you could possibly imagine

The Dominican sisters worshipped in their chapel up to eight hours a day. That's right. Eight hours. Using the same liturgy as all of their order's friaries and priories, the women "sang the offices." The Divine Office extended the prayer of the Mass throughout the day. Also known as the Liturgy of the Hours, the Divine Office is a “sacrifice of praise” in hymns, psalms, and canticles.

They wore uncomfortable clothing.

The Dominican habit they all wore was a white tunic and scapular, a leather belt, a black mantle, and a black veil. The habit was made of unfinished wool, expressing the penance, purity, and poverty of the order. Women and men could only wear linen by special permission. In 1474, Prioress Beatrice Eland petitioned to be allowed to wear linen instead of unfinished wool because she was debilitatem et antiquitatem (elderly and debilitated). She was granted a special license to do so.

The habits worn at a New Jersey Dominican order today.

The habits worn at a New Jersey Dominican order today.

They slept and ate very little. And it was cold.

In a modern-day Dominican nunnery, the sisters usually gather for Lauds (morning prayer), Vespers (evening prayer), and Compline (night prayer). But in the early 16th century, at Dartford Priory, the sisters would have followed the custom of the full monastic schedule.

Whenever the bell rang, the 16th century sisters had to rise from sleep or work and proceed to where they'd sing the offices. Matins and Lauds opened the day at midnight in the summer and at 2 am in the winter. The next time for prayer was dawn: Prime. Some members remained in the chapel between Matins and Prime. Which meant the only sleep they obtained was between the end of Compline, the night prayer, and Matins, at midnight, perhaps three hours total.

As for meals, the word often used is "meager." They practiced perpetual abstinence from meat. There were two meals a day in the summer and one meal a day in the winter. On Fridays at the very least--perhaps three days a week--they fasted, consuming only bread and water. All meals were consumed in silence.

Obviously, there was no central heating in a Tudor-age abbey or priory. Often the buildings had a large cloister garden in the center, where medicinal herbs where grown, and open passageways extended from the quadrangle into the main building. This meant in the winter they moved around in the open air routinely, wearing only their habits. Did most rooms have fireplaces? Nope. Besides the kitchen, often there was one room set aside in the entire abbey or priory with a fire lit, called the Calefactory, or warming room.

This cloister in Croatia shows the open passageways surrounding the garden

This cloister in Croatia shows the open passageways surrounding the garden

------------------------------------

To us, this all may seem hard to fathom. More like prison than a religious house. But their daily lives should be compared not to ours but to those of people who lived outside of the priory walls. And life was rough in the 16th century, especially for women. Many found profound fulfillment in their enclosed orders.

After the prioress was forced to "surrender" the priory to Henry VIII and the buildings were demolished, some of the sisters lived together in small groups, attempting to continue their spiritual community. After Mary I came to the throne and attempted to return the kingdom to the Catholic faith, Dartford was one of two women's religious houses chosen for restoration. Fifteen years had passed, yet more than eight nuns joyfully returned to Dartford, to resume the way of life I've described above and follow to the letter each detail of their spiritual customs.

As Catherine of Siena, a 14th century Dominican saint, wrote, "There is nothing we can desire or want that we do not find in God."

To learn more about the real-life women of Dartford Priory, go here.

-----------------------------------------

I have contributed several chapters to the new anthology Castles, Customs, and Kings: True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors, Volume 2, edited by Debra Brown and Sue Millard

Nearly 50 different authors share the stories, incidents, and insights discovered while doing research for their own historical novels.

To order Castles, Customs and Kings in the U.S., go to Amazon US http://www.amazon.com/Castles-Customs-Kings-English-Historical/dp/0996264817.

To order the book in the United Kingdom, go to http://www.amazon.co.uk/Castles-Customs-Kings-English-Historical/dp/0996264817

This blog post is part of a blog hop to celebrate the publication of Castles, Customs, and Kings: True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors, Volume 2. Details at the end of the post.

Anyone who writes historical fiction acts as a time traveler. What was life like for our characters? How much an author tries to enter the mind of a person who lived centuries ago depends on the author--and the subject. When it comes to lives of long ago, their thoughts and desires and expectations, some of the people seem like us, just wearing different clothes and eating different food.

But then there are the late-medieval Dominican nuns. And they are not much like us.

While researching the history of the Dartford Priory for my trilogy of mysteries, I found myself intrigued, awed, puzzled and impressed by the nuns who lived within the cloister walls. The sole nunnery for Dominican sisters opened its doors in 1372 and was demolished by order of Henry VIII in 1538. It was one of the twenty wealthiest priories in the kingdom, with nuns whose families came from the local gentry, the aristocracy and even royalty. Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville's youngest daughter, Bridget, lived and died at Dartford. But while the priory owned a great deal of property, to provide for both the nuns and the friars at a nearby Dominican order, the women's existences were humble.

Their lives were ruled by custom--by religious doctrine set by the Dominican Order and adhered to meticulously. The sisters took vows of poverty, chastity, charity, and obedience. Dartford was an enclosed order, meaning the women could not leave. The doors were locked from the outside every night. They had chosen to live apart from the world.

Allow me to share just a few other aspects of what would have been expected of Sister Joanna, the protagonist of my series of historical mysteries.

They prayed more than you could possibly imagine

The Dominican sisters worshipped in their chapel up to eight hours a day. That's right. Eight hours. Using the same liturgy as all of their order's friaries and priories, the women "sang the offices." The Divine Office extended the prayer of the Mass throughout the day. Also known as the Liturgy of the Hours, the Divine Office is a “sacrifice of praise” in hymns, psalms, and canticles.

They wore uncomfortable clothing.

The Dominican habit they all wore was a white tunic and scapular, a leather belt, a black mantle, and a black veil. The habit was made of unfinished wool, expressing the penance, purity, and poverty of the order. Women and men could only wear linen by special permission. In 1474, Prioress Beatrice Eland petitioned to be allowed to wear linen instead of unfinished wool because she was debilitatem et antiquitatem (elderly and debilitated). She was granted a special license to do so.

The habits worn at a New Jersey Dominican order today.

The habits worn at a New Jersey Dominican order today. They slept and ate very little. And it was cold.

In a modern-day Dominican nunnery, the sisters usually gather for Lauds (morning prayer), Vespers (evening prayer), and Compline (night prayer). But in the early 16th century, at Dartford Priory, the sisters would have followed the custom of the full monastic schedule.

Whenever the bell rang, the 16th century sisters had to rise from sleep or work and proceed to where they'd sing the offices. Matins and Lauds opened the day at midnight in the summer and at 2 am in the winter. The next time for prayer was dawn: Prime. Some members remained in the chapel between Matins and Prime. Which meant the only sleep they obtained was between the end of Compline, the night prayer, and Matins, at midnight, perhaps three hours total.

As for meals, the word often used is "meager." They practiced perpetual abstinence from meat. There were two meals a day in the summer and one meal a day in the winter. On Fridays at the very least--perhaps three days a week--they fasted, consuming only bread and water. All meals were consumed in silence.

Obviously, there was no central heating in a Tudor-age abbey or priory. Often the buildings had a large cloister garden in the center, where medicinal herbs where grown, and open passageways extended from the quadrangle into the main building. This meant in the winter they moved around in the open air routinely, wearing only their habits. Did most rooms have fireplaces? Nope. Besides the kitchen, often there was one room set aside in the entire abbey or priory with a fire lit, called the Calefactory, or warming room.

This cloister in Croatia shows the open passageways surrounding the garden

This cloister in Croatia shows the open passageways surrounding the garden------------------------------------

To us, this all may seem hard to fathom. More like prison than a religious house. But their daily lives should be compared not to ours but to those of people who lived outside of the priory walls. And life was rough in the 16th century, especially for women. Many found profound fulfillment in their enclosed orders.

After the prioress was forced to "surrender" the priory to Henry VIII and the buildings were demolished, some of the sisters lived together in small groups, attempting to continue their spiritual community. After Mary I came to the throne and attempted to return the kingdom to the Catholic faith, Dartford was one of two women's religious houses chosen for restoration. Fifteen years had passed, yet more than eight nuns joyfully returned to Dartford, to resume the way of life I've described above and follow to the letter each detail of their spiritual customs.

As Catherine of Siena, a 14th century Dominican saint, wrote, "There is nothing we can desire or want that we do not find in God."

To learn more about the real-life women of Dartford Priory, go here.

-----------------------------------------

I have contributed several chapters to the new anthology Castles, Customs, and Kings: True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors, Volume 2, edited by Debra Brown and Sue Millard

Nearly 50 different authors share the stories, incidents, and insights discovered while doing research for their own historical novels.

To order Castles, Customs and Kings in the U.S., go to Amazon US http://www.amazon.com/Castles-Customs-Kings-English-Historical/dp/0996264817.

To order the book in the United Kingdom, go to http://www.amazon.co.uk/Castles-Customs-Kings-English-Historical/dp/0996264817

Published on September 29, 2015 22:00

What was the Life of a 16th century Nun?

By Nancy Bilyeau

This blog post is part of a blog hop to celebrate the publication of Castles, Customs, and Kings: True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors, Volume 2. Details at the end of the post.

Anyone who writes historical fiction acts as a time traveler. What was life like for our characters? How much an author tries to enter the mind of a person who lived centuries ago depends on the author--and the subject. When it comes to lives of long ago, their thoughts and desires and expectations, some of the people seem like us, just wearing different clothes and eating different food.

But then there are the late-medieval Dominican nuns. And they are not much like us.

While researching the history of the Dartford Priory for my trilogy of mysteries, I found myself intrigued, awed, puzzled and impressed by the nuns who lived within the cloister walls. The sole nunnery for Dominican sisters opened its doors in 1372 and was demolished by order of Henry VIII in 1538. It was one of the twenty wealthiest priories in the kingdom, with nuns whose families came from the local gentry, the aristocracy and even royalty. Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville's youngest daughter, Bridget, lived and died at Dartford. But while the priory owned a great deal of property, to provide for both the nuns and the friars at a nearby Dominican order, the women's existences were humble.

Their lives were ruled by custom--by religious doctrine set by the Dominican Order and adhered to meticulously. The sisters took vows of poverty, chastity, charity, and obedience. Dartford was an enclosed order, meaning the women could not leave. The doors were locked from the outside every night. They had chosen to live apart from the world.

Allow me to share just a few other aspects of what would have been expected of Sister Joanna, the protagonist of my series of historical mysteries.

They prayed more than you could possibly imagine

The Dominican sisters worshipped in their chapel up to eight hours a day. That's right. Eight hours. Using the same liturgy as all of their order's friaries and priories, the women "sang the offices." The Divine Office extended the prayer of the Mass throughout the day. Also known as the Liturgy of the Hours, the Divine Office is a “sacrifice of praise” in hymns, psalms, and canticles.

They wore uncomfortable clothing.

The Dominican habit they all wore was a white tunic and scapular, a leather belt, a black mantle, and a black veil. The habit was made of unfinished wool, expressing the penance, purity, and poverty of the order. Women and men could only wear linen by special permission. In 1474, Prioress Beatrice Eland petitioned to be allowed to wear linen instead of unfinished wool because she was debilitatem et antiquitatem (elderly and debilitated). She was granted a special license to do so.

The habits worn at a New Jersey Dominican order today.

The habits worn at a New Jersey Dominican order today.

They slept and ate very little. And it was cold.

In a modern-day Dominican nunnery, the sisters gather for Lauds (morning prayer), Vespers (evening prayer), and Compline (night prayer). But in the early 16th century, at Dartford Priory, the sisters would have followed the custom of the full monastic schedule.

Whenever the bell rang, the 16th century sisters had to rise from sleep or work and proceed to where they'd sing the offices. Matins and Lauds opened the day at midnight in the summer and at 2 am in the winter. The next time for prayer was dawn: Prime. Some members remained in the chapel between Matins and Prime. Which meant the only sleep they obtained was between the end of Compline, the night prayer, and Matins, at midnight, perhaps three hours.

As for meals, the word often used is "meager." They practiced perpetual abstinence from meat. There were two meals a day in the summer and one meal a day in the winter. On Fridays at the very least--perhaps three days a week--they fasted, consuming only bread and water. All meals were consumed in silence.

Obviously, there was no central heating in a Tudor-age abbey or priory. Often the buildings had a large cloister garden in the center, where medicinal herbs where grown, and open passageways extended from the quadrangle into the main building. This meant in the winter they moved around in the open air routinely, wearing only their habits. Did most rooms have fireplaces? Nope. Besides the kitchen, often there was one room set aside in the entire abbey or priory with a fire lit, called the Calefactory, or warming room.

This cloister in Croatia shows the open passageways surrounding the garden

This cloister in Croatia shows the open passageways surrounding the garden

------------------------------------

To us, this all may seem hard to fathom. More like prison than a religious house. But their daily lives should be compared not to ours but to those of people who lived outside of the priory walls. And life was rough in the 16th century, especially for women. Many found profound fulfillment in their enclosed orders.

After the prioress was forced to "surrender" the priory to Henry VIII and the buildings were demolished, some of the sisters lived together in small groups, attempting to continue their spiritual community. After Mary I came to the throne and attempted to return the kingdom to the Catholic faith, Dartford was one of two women's religious houses chosen for restoration. Fifteen years had passed, yet more than eight nuns joyfully returned to Dartford, to resume the way of life I've described above and follow to the letter each detail of their spiritual customs.

As Catherine of Siena, a 14th century Dominican saint, wrote, "There is nothing we can desire or want that we do not find in God."

To learn more about the real-life women of Dartford Priory, go here.

-----------------------------------------

I have contributed several chapters to the new anthology Castles, Customs, and Kings: True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors, Volume 2, edited by Debra Brown and Sue Millard

Nearly 50 different authors share the stories, incidents, and insights discovered while doing research for their own historical novels.

To order Castles, Customs and Kings in the U.S., go to Amazon US http://www.amazon.com/Castles-Customs-Kings-English-Historical/dp/0996264817.

To order the book in the United Kingdom, go to http://www.amazon.co.uk/Castles-Customs-Kings-English-Historical/dp/0996264817

This blog post is part of a blog hop to celebrate the publication of Castles, Customs, and Kings: True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors, Volume 2. Details at the end of the post.

Anyone who writes historical fiction acts as a time traveler. What was life like for our characters? How much an author tries to enter the mind of a person who lived centuries ago depends on the author--and the subject. When it comes to lives of long ago, their thoughts and desires and expectations, some of the people seem like us, just wearing different clothes and eating different food.

But then there are the late-medieval Dominican nuns. And they are not much like us.

While researching the history of the Dartford Priory for my trilogy of mysteries, I found myself intrigued, awed, puzzled and impressed by the nuns who lived within the cloister walls. The sole nunnery for Dominican sisters opened its doors in 1372 and was demolished by order of Henry VIII in 1538. It was one of the twenty wealthiest priories in the kingdom, with nuns whose families came from the local gentry, the aristocracy and even royalty. Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville's youngest daughter, Bridget, lived and died at Dartford. But while the priory owned a great deal of property, to provide for both the nuns and the friars at a nearby Dominican order, the women's existences were humble.

Their lives were ruled by custom--by religious doctrine set by the Dominican Order and adhered to meticulously. The sisters took vows of poverty, chastity, charity, and obedience. Dartford was an enclosed order, meaning the women could not leave. The doors were locked from the outside every night. They had chosen to live apart from the world.

Allow me to share just a few other aspects of what would have been expected of Sister Joanna, the protagonist of my series of historical mysteries.

They prayed more than you could possibly imagine

The Dominican sisters worshipped in their chapel up to eight hours a day. That's right. Eight hours. Using the same liturgy as all of their order's friaries and priories, the women "sang the offices." The Divine Office extended the prayer of the Mass throughout the day. Also known as the Liturgy of the Hours, the Divine Office is a “sacrifice of praise” in hymns, psalms, and canticles.

They wore uncomfortable clothing.

The Dominican habit they all wore was a white tunic and scapular, a leather belt, a black mantle, and a black veil. The habit was made of unfinished wool, expressing the penance, purity, and poverty of the order. Women and men could only wear linen by special permission. In 1474, Prioress Beatrice Eland petitioned to be allowed to wear linen instead of unfinished wool because she was debilitatem et antiquitatem (elderly and debilitated). She was granted a special license to do so.

The habits worn at a New Jersey Dominican order today.

The habits worn at a New Jersey Dominican order today. They slept and ate very little. And it was cold.

In a modern-day Dominican nunnery, the sisters gather for Lauds (morning prayer), Vespers (evening prayer), and Compline (night prayer). But in the early 16th century, at Dartford Priory, the sisters would have followed the custom of the full monastic schedule.

Whenever the bell rang, the 16th century sisters had to rise from sleep or work and proceed to where they'd sing the offices. Matins and Lauds opened the day at midnight in the summer and at 2 am in the winter. The next time for prayer was dawn: Prime. Some members remained in the chapel between Matins and Prime. Which meant the only sleep they obtained was between the end of Compline, the night prayer, and Matins, at midnight, perhaps three hours.

As for meals, the word often used is "meager." They practiced perpetual abstinence from meat. There were two meals a day in the summer and one meal a day in the winter. On Fridays at the very least--perhaps three days a week--they fasted, consuming only bread and water. All meals were consumed in silence.

Obviously, there was no central heating in a Tudor-age abbey or priory. Often the buildings had a large cloister garden in the center, where medicinal herbs where grown, and open passageways extended from the quadrangle into the main building. This meant in the winter they moved around in the open air routinely, wearing only their habits. Did most rooms have fireplaces? Nope. Besides the kitchen, often there was one room set aside in the entire abbey or priory with a fire lit, called the Calefactory, or warming room.

This cloister in Croatia shows the open passageways surrounding the garden

This cloister in Croatia shows the open passageways surrounding the garden------------------------------------

To us, this all may seem hard to fathom. More like prison than a religious house. But their daily lives should be compared not to ours but to those of people who lived outside of the priory walls. And life was rough in the 16th century, especially for women. Many found profound fulfillment in their enclosed orders.

After the prioress was forced to "surrender" the priory to Henry VIII and the buildings were demolished, some of the sisters lived together in small groups, attempting to continue their spiritual community. After Mary I came to the throne and attempted to return the kingdom to the Catholic faith, Dartford was one of two women's religious houses chosen for restoration. Fifteen years had passed, yet more than eight nuns joyfully returned to Dartford, to resume the way of life I've described above and follow to the letter each detail of their spiritual customs.

As Catherine of Siena, a 14th century Dominican saint, wrote, "There is nothing we can desire or want that we do not find in God."

To learn more about the real-life women of Dartford Priory, go here.

-----------------------------------------

I have contributed several chapters to the new anthology Castles, Customs, and Kings: True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors, Volume 2, edited by Debra Brown and Sue Millard

Nearly 50 different authors share the stories, incidents, and insights discovered while doing research for their own historical novels.

To order Castles, Customs and Kings in the U.S., go to Amazon US http://www.amazon.com/Castles-Customs-Kings-English-Historical/dp/0996264817.

To order the book in the United Kingdom, go to http://www.amazon.co.uk/Castles-Customs-Kings-English-Historical/dp/0996264817

Published on September 29, 2015 22:00

September 14, 2015

My Love of Atmosphere

It always makes my day when a reviewer, whether it's a professional book critic or a reader sharing thoughts on amazon and goodreads, remarks on my love of creating atmosphere in my books. I do aim to immerse readers in the sights, sounds and smells of Tudor England. I almost feel like the mistress of a time-travel machine. The next stop is 1540. :)

From the respected website crimereview.co.uk:

For the rest of the review, go here.

From the respected website crimereview.co.uk:

"In this final chronicle of the Joanna Stafford trilogy, Nancy Bilyeau’s vivid prose, mastery of atmosphere, a deft and pacey plot involving two kings, greedy and ambitious barons and bishops, influence seekers, religious fanatics, spies and killers, set against a background of Europe-wide uncertainty, dread and oppression, bring the Tudor period to thrilling life."

For the rest of the review, go here.

Published on September 14, 2015 05:30

August 10, 2015

What did Whitehall Look Like?

One of the challenges in writing my 16th century trilogy is how many buildings are lost. Not just the abbeys, either. In The Tapestry, Joanna Stafford spends one-third of the book at the palace of Whitehall, which burned to the ground in 1698.

In my post on English Historical Fiction Authors, I share some of my research into the lost beauty of Whitehall. Go here to read.

In my post on English Historical Fiction Authors, I share some of my research into the lost beauty of Whitehall. Go here to read.

Published on August 10, 2015 05:36

August 9, 2015

"In Lone Magnificence, a Ruin Stands": Tintern Abbey

By Nancy Bilyeau

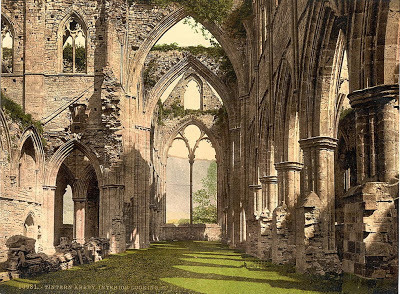

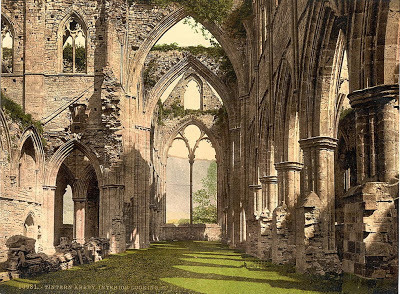

Tintern AbbeyThis post is the next in a series on the monastic ruins of England. In the first installment I wrote about Furness Abbey in Cumbria; in the second I wrote about Thetford Priory in Norfolk. I launched this project with my post on English Historical Fiction Authors: "Listening to Blackfriars." And now I move the series to a treasure of Wales...

Tintern AbbeyThis post is the next in a series on the monastic ruins of England. In the first installment I wrote about Furness Abbey in Cumbria; in the second I wrote about Thetford Priory in Norfolk. I launched this project with my post on English Historical Fiction Authors: "Listening to Blackfriars." And now I move the series to a treasure of Wales...

Tintern Abbey

On the Welsh bank of the River Wye, Tintern Abbey, founded in 1131, soars to the sky nearly six hundreds years after the last monks departed. It survived the Edwardian Wars, the Bubonic plague, even the destruction of the monasteries--roofless, yes, and crumbling in many places, but far more intact than most other medieval abbeys. Tintern has proved a potent force of inspiration for writers, painters, and musicians, ranging from poet William Wordsworth to metal band Iron Maiden--not to mention Alan Ginsberg!

THE FOUNDING: Walter de Clare, lord of Chepstow and a relation of the Bishop of Winchester, founded Tintern Abbey. The De Clares were a vigorous, often violent Norman family that jostled for power from the time of William the Conqueror up to the early 14th century. When Walter, abbey founder, died childless, his nephew Gilbert De Clare assumed control of his lands, becoming the first Earl of Pembroke while earning the nickname Strongbow for his soldiering, mostly on behalf of King Stephen during the war over succession with his cousin, Queen Mathilda.

A view of the abbey churchTintern was the second Cistercian abbey to be established in England; its monks arrived from Blois in France. Over the next century, the high point in England's history of monasticism, Tintern's land holdings grew rapidly. Thanks to the patronage of Roger Bigod, earl of Norfolk, the monastery was blessed with a large, ornate church, following a cruciform plan. More than 200 feet long, it was built in red sandstone in the Gothic style.

A view of the abbey churchTintern was the second Cistercian abbey to be established in England; its monks arrived from Blois in France. Over the next century, the high point in England's history of monasticism, Tintern's land holdings grew rapidly. Thanks to the patronage of Roger Bigod, earl of Norfolk, the monastery was blessed with a large, ornate church, following a cruciform plan. More than 200 feet long, it was built in red sandstone in the Gothic style.

THE ORDER: The Cistercians, also known as the White Monks, were formed with the goal of reform. They were very popular--by the year 1200 there were more than 500 Cistercian abbeys in Europe.

THE GLORY: The beauty of Tintern was a source of great pride to the surrounding countryside. Because its location was somewhat isolated, the abbey did not suffer any attacks during King Edward I's brutal conquest of Wales in 1282. Other monasteries thought to be sheltering Welsh leaders were damaged.

Gilbert De ClareTintern might have come under the protection of Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Hertford and Gloucester and commander of the king's forces for a time. Because of the family's connection to Tintern, it is possible the "Red Earl"--so named for his red hair and dangerous temper-- ordered the abbey left alone. The Red Earl was a noble perpetually scheming and fighting and changing sides. He supported Simon de Montfort instead of Henry III, but betrayed him and later became young King Edward I's greatest champion, eventually marrying one of his daughters. Undoubtedly guilty of horrific murders, he often spoke of a desire to go on Crusade to the Holy Lands. In his 50s, he fought so bitterly with another nobleman over a land dispute, he was briefly imprisoned. De Clare was most definitely a creature of the medieval age.

Gilbert De ClareTintern might have come under the protection of Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Hertford and Gloucester and commander of the king's forces for a time. Because of the family's connection to Tintern, it is possible the "Red Earl"--so named for his red hair and dangerous temper-- ordered the abbey left alone. The Red Earl was a noble perpetually scheming and fighting and changing sides. He supported Simon de Montfort instead of Henry III, but betrayed him and later became young King Edward I's greatest champion, eventually marrying one of his daughters. Undoubtedly guilty of horrific murders, he often spoke of a desire to go on Crusade to the Holy Lands. In his 50s, he fought so bitterly with another nobleman over a land dispute, he was briefly imprisoned. De Clare was most definitely a creature of the medieval age.

After the battles in Wales were over, Tintern's renown grew. In 1326 Edward II, the son of the Red Earl's patron-turned-punisher, spent two nights there.

It was not a king or a nobleman but a disease that dealt Tintern its most serious blow. In 1348 or 1349 the Bubonic Plague reached Wales, killing one-third of the population. Wrote Welsh poet Jean Geuthin:

THE DISSOLUTION: When Henry VIII broke with Rome and set loose the laws that dissolved the monasteries, some of the abbots and priors, monks and friars, resisted and incurred the wrath of the king. Tintern was not one of them. On Sept. 3, 1536, Abbot Wyche surrendered the abbey and all of its lands. If a monastery was in or near London, it was likely to be transformed into a home for a nobleman close to the king. But no one took Tintern as a home. All valuables were taken and the roofs were stripped for their lead.

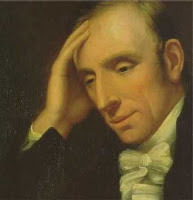

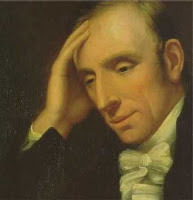

THE LEGACY: Few visited Tintern and no one much cared about its history until the Romantic movement, keen for picturesque ruins, discovered the abbey. Just about the time Turner painted the monastery, William Wordsworth in 1798 wrote the much-admired "Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey":

William Wordsworth"...These beauteous forms,

William Wordsworth"...These beauteous forms,

Through a long absence, have not been to me

As is a landscape to a blind man's eye:

But oft, in lonely rooms, and 'mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind,

With tranquil restoration: -- feelings too

Of unremembered pleasure: such, perhaps,

As have no slight or trivial influence

On that best portion of a good man's life..."

Tintern Abbey became a popular destination, inspiring other poets, novelists, painters, and scholars. Parties especially liked to go at night to see the torchlight dance off the soaring walls.

Painting by J.M.W. TurnerThe crown purchased the land from its owner, the duke of Somerset, in 1901 and the buildings were better maintained.

Painting by J.M.W. TurnerThe crown purchased the land from its owner, the duke of Somerset, in 1901 and the buildings were better maintained.

In 1967 Allen Ginsburg took an acid trip at Tintern and wrote a poem dedicated to "clouds passing through skeleton arches."

In 1967 Allen Ginsburg took an acid trip at Tintern and wrote a poem dedicated to "clouds passing through skeleton arches."

But of all the dedications to Tintern, perhaps the one least predictable by its medieval monks and lords was the band Iron Maiden, in its video for the song "Can I Play with Madness." It makes excellent use of the ruins site: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ocFxQjPeyiY

To learn more about visiting Tintern Abbey, now owned by Cadw, go here.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"In lone magnificence a ruin stands" is contained in The Ruins of Netley Abbey, by 18th century poet George Keate.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Nancy Bilyeau is writing a thriller trilogy set in 16th century England during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The first novel, The Crown, published by Simon&Schuster in North America and Orion in the United Kingdom, was on the short list of the Crime Writers' Association's Ellis Peters Historical Dagger Award in 2012. The second novel, The Chalice, won Best Historical Mystery from the RT Reviews.

Tintern AbbeyThis post is the next in a series on the monastic ruins of England. In the first installment I wrote about Furness Abbey in Cumbria; in the second I wrote about Thetford Priory in Norfolk. I launched this project with my post on English Historical Fiction Authors: "Listening to Blackfriars." And now I move the series to a treasure of Wales...

Tintern AbbeyThis post is the next in a series on the monastic ruins of England. In the first installment I wrote about Furness Abbey in Cumbria; in the second I wrote about Thetford Priory in Norfolk. I launched this project with my post on English Historical Fiction Authors: "Listening to Blackfriars." And now I move the series to a treasure of Wales...Tintern Abbey

On the Welsh bank of the River Wye, Tintern Abbey, founded in 1131, soars to the sky nearly six hundreds years after the last monks departed. It survived the Edwardian Wars, the Bubonic plague, even the destruction of the monasteries--roofless, yes, and crumbling in many places, but far more intact than most other medieval abbeys. Tintern has proved a potent force of inspiration for writers, painters, and musicians, ranging from poet William Wordsworth to metal band Iron Maiden--not to mention Alan Ginsberg!