Tim Unwin's Blog, page 7

March 25, 2020

Donor and government funding of Covid-19 digital initiatives

[image error]We are all going to be affected by Covid-19, and we must work together across the world if we are going to come out of the next year peacefully and coherently. The world in a year’s time will be fundamentally different from how it is now; now is the time to start planning for that future. The countries that will be most adversely affected by Covid-19 are not the rich and powerful, but those that are the weakest and that have the least developed healthcare systems. Across the world, many well-intentioned people are struggling to do what they can to make a difference in the short-term, but many of these initiatives will fail; most of them are duplicating ongoing activity elsewhere; many of them will do more harm than good.

This is a plea for us all to learn from our past mistakes, and work collaboratively in the interests of the world’s poorest and most marginalised rather than competitively and selfishly for ourselves.

Past mistakes

Bilateral donors and international organisations are always eager to use their resources at times of crisis both to try to do good, but also to be seen to be trying to do good. Companies and civil society organisations also often try to use such crises to generate revenue and raise their own profiles. As a result many crises tend to benefit the companies and NGOs more than they do the purportedly intended beneficiaries.

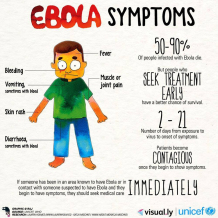

This was classically, and sadly, demonstrated in the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014, especially with the funding of numerous Internet-based initiatives – at a time when only a small fraction of the population in the infected countries was actually connected to the Internet. At that time, I wrote a short piece that highlighted the many initiatives ongoing in the continent. Amongst other things this noted that:

“A real challenge now, though, is that so many initiatives are trying to develop digital resources to support the response to Ebola that there is a danger of massive duplication of effort, overlap, and simply overload on the already stretched infrastructure, and indeed people, in the affected countries”, and

“A real challenge now, though, is that so many initiatives are trying to develop digital resources to support the response to Ebola that there is a danger of massive duplication of effort, overlap, and simply overload on the already stretched infrastructure, and indeed people, in the affected countries”, and“Many, many poor people will die of Ebola before we get it under control collectively. We must never make the same mistakes again”.

I have not subsequently found any rigorous monitoring and evaluation reports about the efficacy of most of the initiatives that I then listed, nor of the countless other digital technology projects that were funded and implemented at the time. However, many such projects hadn’t produced anything of value before the crisis ended, and most failed to many any significant impact on mortality rates or on the lives of those people affected.

In the hope of trying not to make these same mistakes again, might I suggest the following short-term and longer-term things to bear in mind as we seek to reduce the deaths and disruption caused by Covid-19.

Short-term responses

The following five short-term issues strike me as being particularly important for governments and donors to bear in mind, especially in the context of the use of digital technologies:

Support and use existing technologies. In most (but not all) instances the development and production of new technological solutions will take longer than the immediate outbreak that they are designed to respond to. Only fund initiatives that will still be relevant after the immediate crisis is over, or that will enable better responses to be made to similar crises in the future. Support solutions that are already proven to work.

Co-ordinate and collaborate rather than compete. Countless initiatives are being developed to try to resolves certain aspects of the Covid-19 crisis, such as lack of ventilators or the development of effective testing kits (see below). This is often because of factors such as national pride and the competitive advantage that many companies (and NGOs) are seeking to achieve. As a result, there is wasteful duplication of effort, insufficient sharing of good practice, and the poor and marginalised usually do not receive the optimal treatment. It is essential for international organisations to share widely accepted good practices and technological designs that can be used across the world in the interests of the least powerful.

Ensure that what you fund does more good than harm. Many initiatives are rushed onto the market without having been sufficiently tried and tested in clinical contexts. Already, we have seen a plethora of false information being published about Covid-19, some out of ignorance and some deliberate falsification. It is essential that governments and donors support reliable initiatives, and that possible unintended consequences are thorouighly considered.

Remember that science is a contested field. Value-free science does not exisit. Scientists are generally as interested in their own careers as anyone else. There is also little universal scientific agreement on anything. Hence, it is important for politicians and decision makers carefully to evaluate different ideas and proposed solutions, and never to resort to claiming that they are acting on scientific advice. If you are a leader you have to make some tough decisions.

Ensure that funding goes to where it is most needed. In many such crises funding that is made available is inappropriately used, and it is therefore essential for governments and donors to put in place effective and robus measures to ensure transparency and probity in funding. A recent letter from Transparency International to the US Congress, for example, recommends 25 anti-corruption measures that it believes are necessary to ” help protect against self-interested parties taking advantage of this emergency for their own benefit and thereby undermining the safety of our communities”.

In the medium term…

Immediate action on Covid-19 is urgent, but a well thought-through and rigorous medium-term response by governments and donors is even more important, especially in the context of the use of digital technologies:

We must start planning now for what the world will be like in 18 months time. Two things about Covid-19 are certain: many people will die, and it will change the world forever. Already it is clear that one outcome will be vastly greater global use of digital technologies. This, for example, is likely dramatically to change the ways in which people shop: as they get used to buying more of their requirements online, traditional suppliers will have to adapt their practices very much more rapipdly than they have been able to do to date. Those with access to digital technologies will become even more advantaged compared with those who cannot afford them, do not know how to use them, or do not have access to them.

Planning for fundamental changes to infrastructure and government services: education and health. The impact of Covid-19 on the provision of basic government services is likely to be dramatic, and particularly so in countries with weak infrastructures and limited provision of fundamental services. Large numbers of teachers, doctors and nurses are likely to die across the world, and we need to find ways to help ensure that education and health services can be not only restored but also revitalised. Indeed, we should see this as an opportunity to introduce new and better systems to enable people to live healthier and more fulfilled lives. The development of carefully thought through recommendations on these issues, involving widespread representative consultation, in the months ahead will be very important if governments, especially in the poorest countries, are to be able to make wise use of the opportunities that Covid-19 is creating. There is a very significant role for all donors in supporting such initiatives.

Communities, collaboration and co-operation. Covid-19 offers an opportunity for fundamentally different types of economy and society to be shaped. New forms of communal activity are already emerging in countries that have been hardest hit by Covid-19. Already, there are numerous reports of the dramatic impact of self-isolation and reduction of transport pollution on air quality and weather in different parts of the world (see The Independent, NPR, CarbonBrief). Challenges with obtaining food and other resources are also forcing many people to lead more frugal lives. However, those who wish to see more communal and collaborative social formations in the future will need to work hard to ensure that the individualistic, profit-oriented, greedy and selfish societies in which we live today do not become ever more entrenched. We need to grasp this opportunity together to help build a better future, especially in the interests of the poor and marginalised.

Examples of wasteful duplication of effort

Already a plethora of wasteful (in terms of both time and money), competitive and duplicative initiatives to tackle various aspects of the Covid-19 pandemic have been set in motion. These reflect not only commercial interests, but also national pride – and in some instances quite blatant racism. Many are also very ambitious, planning to deliver products in only a few weeks. Of course critical care ventilators, test kits, vaccines and ways of identifying antibodies are incredibly important, but greater global collaboration and sharing would help to guarantee both quantity and quality of recommended solutions. International Organisations have a key role to play in establishing appropriate standards for such resources, and for sharing Open Source (or other forms of communal) templates and designs. Just a very few of the vast number of ongoing initiatives are given in the reports below:

Critical care ventilators

India

Why Ventilators are key to fighting the coronavirus battle

Bengaluru based Skanray starts work on new ventilator design that would speed up production locally

How India can combat the ventilator shortage? Bangalore-based Skanray Technologies plans to make 1 lakh locally sourced ventilators in 2-3 months to battle coronavirus. Shereen Bhan speaks to Vishwaprasad Alva of Skanray Tech

Pakistan:

The first 3D-printed ventilator prototype in Pakistan could be ready within two weeks

Covid-19 ventilator hackathon

UPDATE: COVID-19 LOCAL VENTILATOR EFFORTS: HOW NOT TO BE AN INHIBITOR OF INNOVATION?

Spain

OxyGEN, is a device that responds to the lack of emergency respirators in the COVID-19 health crisis

UK

Government chooses design of ventilators that UK urgently needs

Dyson draws up plan for ventilator

USA

People Are Trying to Make DIY Ventilators to Meet Coronavirus Demand

Julian Botta (Johns Hopkins)

Testing kits

Australia

Rapid Covid-19 testing kits receive urgent approval from Australian regulator

Bangladesh

Bangladesh approves low-cost test kit to detect Covid-19

China/EU

New rapid test kit to detect COVID-19 soon available in EU

India

Mylab receives approval for Covid-19 test kit

Kenya

African Nations Try to Overcome Shortage of COVID-19 Test Kits

South Africa

The race for COVID-19 local test kits

Despite criticisms of the replicative and wasteful nature of many such initiatives, there are a few initiatives at a global scale that do offer hope. Prime among these must be Jack Ma’s donation of 20,000 testing kits to each of 54 African countries, which will go some way to reducing the need for these to be domestically produced across the continent. But this is sadly only a small shower of rain on an otherwise parched continent. Working together, we have much more to be achieved, both now and in the months ahead.

March 19, 2020

Crowdsourcing Covid-19 infection rates

Covid-19, 19 March 2020, Source: https://coronavirus.thebaselab.com/

I have become increasingly frustrated by the continued global reporting of highly misleading figures for the number of Covid-19 infections in different countries. Such “official” figures are collected in very different ways by governments and can therefore not simply be compared with each other. Moreover, when they are used to calculate death rates they become much more problematic. At the very least, everyone who cites such figures should refer to them as “Officially reported Infections”

As I write (19th March 2020, 17.10 UK time), the otherwise excellent thebaselab‘s documentation of the coronavirus’s evolution and spread gives mortality rates (based on deaths as a percentage of infected cases) for China as 4.01%, Italy as 8.34% and the UK as 5.09%. However, as countries are being overwhelmed by Covid-19, most no longer have the capacity to test all those who fear that they might be infected. Hence, as the numbers of tests as a percentage of total cases go down, the death rates will appear to go up. It is fortunately widely suggested that most people who become infected with Covid-19 will only have a mild illness (and they are not being tested in most countries), but the numbers of deaths become staggering if these mortality rates are extrapolated. Even if only 50% of people are infected (UK estimates are currently between 60% and 80% – see the Imperial College Report of 16th March that estimates that 81% of the UK and US populations will be infected), and such mortality rates are used, the figures (at present rates) become frightening:

In Italy, with a total population of 60.48 m, this would mean that 30.24 m people would be infected, which with a mortality rate of 8.34% would imply that 2.52 m people would die;

In the UK, with a total population of 66.34 m, this would mean that 33.17 m people would be infected, which with a mortality rate of 5.09% would imply that 1.69 m people would die.

These figures are unrealistic, because only a fraction of the total number of infected people are being tested, and so the reported infection rates are much lower than in reality. In order to stop such speculations, and to reduce widespread panic, it is essential that all reporting of “Infected Cases” is therefore clarified, or preferably stopped. Nevertheless, the most likely impact of Covid-19 is still much greater than most people realise or can fully appreciate. The Imperial College Report (p.16) thus suggests that even if all patients were to be treated, there would still be around 250,000 deaths in Great Britain and 1.1-1.2 m in the USA; doing nothing, means that more than half a million people might die in the UK.

Having accurate data on infection rates is essential for effective policy making and disease management. Globally, there are simply not enough testing kits or expertise to be able to get even an approximately accurate figure for real infections rates. Hence, many surrogate measures have been used, all of which have to make complex assumptions about the sample populations from which they are drawn. An alternative that is fortunately beginning to be considered is the use of digital technologies and social media. Whilst by no means everyone has access to digital technologies or Internet connectivity, very large samples can be generated. It is estimated that on average 2.26 billion people use one of the Facebook family of services every day; 30% of the world’s population is a large sample. Existing crowdsourcing and social media platforms could therefore be used to provide valuable data that might help improve the modelling, and thus the management of this pandemic.

Crowdsourcing

The violence in Kenya following the disputed Presidential elections in 2007, provided the cradle for the development of the Open Source crowdmapping platform, Ushahidi, which has subsequently been used in responding to disasters such as the earthquakes in Haiti and Nepal, and valuable lessons have been learnt from these experiences. While there are many challenges in using such technologies, the announcement on 18th March that Ushahidi is waiving its Basic Plan fees for 90 days is very much to be welcomed, and provides an excellent opportunity to use such technologies better to understand (and therefore hopefully help to control) the spread of Covid-19. However, there is a huge danger that such an opportunity may be missed.

The following (at a bare minimum) would seem to be necessary to maximise the opportunity for such crowdsourcing to be successful:

We must act urgently. The failure of countries across the world to act in January, once the likely impact of events in Wuhan unravelled was staggering. If we are to do anything, we have to act now, not least to help protect the poorest countries in the world with the weakest medical services. Waiting even a fortnight will be too late.

Some kind of co-ordination and sharing of good practices is necessary. Whilst a global initiative might be feasible, it would seem more practicable for national initiatives to be created, led and inspired by local activists. However, for data to be comparable (thereby enabling better modelling to take place) it is crucial for these national initiatives to co-operate and use similar methods and approaches. There must also be close collaboration with the leading researchers in global infectious disease analysis to identify what the most meaningful indicators might be, as well as international organisations such as the WHO to help disseminate practical findings..

An agreed classification. For this to be effective there needs to be a simple agreed classification that people across the world could easily enter into a platform. Perhaps something along these lines might be appropriate: #Covid? (I think I might have symptoms), #Covid7 (I have had symptoms for 7 days), #Covid14 (I have had symptoms for 14 days), #CovidT (I have been tested and I have it), #Covid0 (I have been tested and I don’t have it), #CovidH (I have been hospitalised), #CovidX (a person has died from it).

Practical dissemination. Were such a platform (or national platforms) to be created, there would need to be widespread publicity, preferably by governments and mobile operators, to encourage as many people as possible to enter their information. Mutiple languages would need to be incorporated, and the interfaces would have to be as appealing and simple as possible so as to encourage maximum submission of information.

Ushahidi as a platform is particularly appealing, since it enables people to submit information in multiple ways, not only using the internet (such as e-mail and Twitter), but also through SMS messages. These data can then readily be displayed spatially in real time, so that planners and modellers can see the visual spread of the coronavirus. There are certainly problems with such an approach, not least concerning how many people would use it and thus how large a sample would be generated, but it is definitely something that we should be exploring collectively further.

Social media

An alternative approach that is hopefully also already being explored by global corporations (but I have not yet read of any such definite projects underway) could be the use of existing social media platforms, such as Facebook/WhatsApp, WeChat or Twitter to collate information about people’s infection with Covid-19. Indeed, I hope that these major corporations have already been exploring innovative and beneficial uses to which their technologies could be put. However, if this if going to be of any real practical use we must act very quickly.

In essence, all that would be needed would be for there to be an agreed global classification of hashtags (as tentatively suggested above), and then a very widespread marketing programme to encourage everyone who uses these platforms simply to post their status, and any subsequent changes. The data would need to be released to those undertaking the modelling, and carefully curated information shared with the public.

Whilst such suggestions are not intended to replace existing methods of estimating the spread of infectious diseases, they could provide a valuable additional source of data that could enable modelling to be more accurate. Not only could this reduce the number of deaths from Covid-19, but it could also help reassure the billions of people who will live through the pandemic. Of course, such methods also have their sampling challenges, and the data would still need to be carefully interpreted, but this could indeed be a worthwhile initiative that would not be particularly difficult or expensive to initiate if global corporations had the will to do so.

Some final reflections

Already there are numerous new initiatives being set up across the world to find ways through which the latest digital technologies might be used in efforts to minimise the impact of Covid-19. The usual suspects are already there as headlines such as these attest: Blockchain Cures COVID-19 Related Issues in China, AI vs. Coronavirus: How artificial intelligence is now helping in the fight against COVID-19, or Using the Internet of Things To Fight Virus Outbreaks. While some of these may have potential in the future when the next pandemic strikes, it is unlikely that they will have much significant impact on Covid-19. If we are going to do anything about it, we must act now with existing well known, easy to use, and reliable digital technologies.

I fear that this will not happen. I fear that we will see numerous companies and civil society organisations approaching donors with brilliant new innovative “solutions” that will require much funding and will take a year to implement. By then it will be too late, and they will be forgotten and out of date by the time the next pandemic arrives. Donors should resist the temptation to fund these. We need to learn from what happened in West Africa with the spread of Ebola in 2014, when more than 200 digital initiatives seeking to provide information relating to the virus were initiated and funded (see my post On the contribution of ICTs to overcoming the impact of Ebola). Most (although not all) failed to make any significant impact on the lives and deaths of those affected, and the only people who really benefitted were the companies and the staff working in the civil society organisations who proposed the “innovations”.

This is just a plea for those of us interested in these things to work together collaboratively, collectively and quickly to use what technologies we have at our fingertips to begin to make an impact. Next week it will probably be too late…

March 18, 2020

Ten tips for working at home and self-isolating

I have always worked in part from home, on the road overseas in hotels, alone in strange places… However, when I left full-time salaried work in 2015, and shifted primarily to working from home, I swiftly discovered the need substantially to readjust my habits. For those without such experiences, who are being forced to self-isolate or work at home as a result of Covid-19 there are likely to be many challenges – but there are now plenty of guides available for things to do to help manage the rapid change of lifestyle (see below). Most of these are very sensible, but do not necessarily coincide with my own experiences. So here are just a few tips that might be useful (in approximate order of importance):

1. Be positive and treat it as an adventure

[image error]It is much easier to enjoy change if you treat it in a positive way. Think about all the good things: no need to travel to work; spending time with those you love (hopefully); doing things at home that you have always wanted to! Treat the next few weeks or months as an opportunity to do new and exciting things. Discover your home again!

2. Try to keep your work place separate from your sleeping place

[image error]If at all possible, it is absolutely essential to have separate sleeping and working places so that you remain sane. There is much evidence that trying to sleep in the same place in which you work can confuse the mind, and may tend to make it continue to work when you want to go to sleep – even subconsciously – rather than enabling you to rest. You are likely to be worried about the implications of Covid-19, and so it is essential that you do all you can to ensure a good night’s sleep. This may not be easy for many people, but you should still try not to work in your bedroom! And don’t continue working too late – give your body the time it needs to relax and rest.

3. Take as much exercise as possible

[image error]It is incredibly easy to put on weight when working at home, even if you think you are not doing so! This is bad for your health, and bad for morale. It’s easy to understand why this happens: many people commute to work, and even if not cycling, they walk from their transport node to their office; homes are smaller than offices, and so you generally walk more at work than at home; and often you will go out of the office during the daytime, perhaps for lunch, but you can’t do this if you are self-isolating. There are lots of things, though, that you can do to rectify this: walk up and down stairs several times a day (never take the lift); ensure that you go for a short walk every hour (even if it is just 20 times around your home); if you have some outdoor space, take up gardening (it uses lots of muscles you never thought you had!); and even if you don’t decide to buy a stationary bike (actually much cheaper than joining a gym), you can still exercise with a resistance band, or even use bags of sugar as weights!

4. Let everyone in the household have their own nest for working in

[image error]You may well already have done this! However, if not, remember that we all construct different kinds of places for working in. I know I am one of the most antisocial people in the world when I am thinking and writing; my home office looks a complete mess, but I know exactly where everything is, and woe betide anyone who moves something! So, if there are several of you working at home, try to create your own spaces for working in. Your husband, wife, partner, or children will all work in different ways, so try to ensure that everyone has a separate working place. You will all be more productive – and get on better after you’ve finished working!

5. Plan your day – and give yourself treats

[image error]When you don’t have to catch public transport, or cycle/drive/walk to work it is terribly easy to be lazy, and let time slip by without focusing on the tasks in hand. Most people like to feel they have achieved something positive every day. One way to ensure this is to plan each day carefully. And don’t forget to give yourself treats when you have achieved something – whatever it is that you enjoy!

6. Keep a balance to your life

[image error]This is closely linked to planning – but don’t just spend all your time relaxing, or doing nothing but work! It’s important to maintain diversity in life. If your boss expects you to work a 10 hour day, then make sure that you do (hopefully s/he won’t). But even then you have 14 hours each day to do other things (please try and get 7 hours of sleep – it will help to keep you fit and well)! I find that having a colour coded diary with a clear schedule helps me manage my life – even though I tend to work far too much! The trouble is I enjoy my work!

7. Create agreed ground rules and expectations to reduce tensions

[image error]Many people who now have to work at home because of Covid-19 will not have had much experience previously at doing this. It can come as a shock getting to see other aspects of a loved one’s life. Tensions are bound to arise, especially if you are trying to work when your children are at home because school has been closed. It can help to have a thorough and transparent discussion between all members of a household (including the children) to set some ground rules for how you are going to manage the next few weeks and months. This can indeed be challenging, and will frequently require revisiting, but having some shared expectations can help reduce the tensions that are bound to arise. Listening (however difficult it is) often helps to lower tension.

8. Wear different clothes just as you would if you went out to work (and play)

[image error]The clothes we wear represent how we feel, but can also help shape those feelings. It is amazing what an effect it can have if you get dressed smartly when you are feeling low. Likewise, most people like to dress in more relaxed clothing when they stop working, and we don’t usually sleep in the same clothes that we have worn during the day. Just because you are working at home, doesn’t necessarily mean that you will work well in your pyjamas (and imagine if you are suddenly asked to join a conference call without time to change!). The simple message is that we should continue to take care of ourselves, just as if we were going out to work or to a party!

9. Switch off your digital devices (at least some of the time)

[image error]Enjoy the physicality of life. Don’t always feel you have to be online in case “work” wants to get in touch. None of us are that important. The world will get by perfectly well without us! There is a lot of evidence that being online late at night can also disturb our sleep patterns. Remember that although we are increasingly being programmed to believe that digital technology gives us much more freedom in how we work, it is actually mainly used by the owners of capital further to exploit their workforces by making them work longer hours for no extra pay!

10. Use the time creatively to do something that you have always wanted to do

[image error]Being self-isolated at home will mean that you have vastly more time on your hands than you can ever imagine (as long as you don’t work all day and night). Use it creatively to do something that you have always thought about doing, but never had the time before. Read those books that you always wanted to. Learn a musical instrument. Learn to speak a new language (Python or Mandarin). Take up painting. Discover how to cook delicious meals with limited resources. Photograph the wildlife in your garden. Grow your own vegetables. Make beer. Even just plan your next (or first) holiday.

Other useful resources (with a mainly UK focus) include:

Mind – Coronavirus and your wellbeing

Young Minds – Looking after your mental health while self-isolating

The Guardian – How to survive isolation with your roommates, your partner, your kids – and yourself

Financial Times – Living in self-isolation: beating quarantine boredom and eating carbs

I very much hope that some of these ideas will help to get you through the next few months, and that we will all emerge from the Covid-19 pandemic as being more considerate for others, and less concerned about ourselves. Thinking more about how you can help others rather than what you want yourself is a good way to start planning for self-isolation.

March 17, 2020

What we understood by Corona…

It is not easy to be positive about the spread of Covid-19 (the latest Coronavirus) around the world, which as I write has now reached at least 164 countries with a death toll of around 8,000 people. However, until the start of 2020, “Corona” meant rather different things to people. I was particularly struck by this while travelling in Pakistan in January and February of this year. So, I posted a tweet earlier today to explore what people had associated with the word in the past. This is the result (to be updated should any further suggestions be made!).

Mexico (and Puerto Rico)

[image error]In Mexico and indeed in many other countries, Corona was above all else associated with beer! Produced by Cerveceria Modelo, Corona is a pale lager and one of the five top-selling beers across the world. In 2013 the Grupo Modelo merged with Anheuser-Busch InBev in a transaction valued at US$ 20.1 billion. Interestingly, one of the three main breweries in Puerto Rico in the 1930s was called Cerveceria Corona, and it later sold its rights to Cervecería Modelo de México, which then launched Cerveza Corona as Modelo’s Corona Extra.

Pakistan

[image error]In Pakistan, Corona was known above all else as a paint. It is made by Dawn Coating Industry, which was founded in 1970, and has the ambition of becoming the largest national decorative paint company in the country. Its advertisments can be seen painted on buildings across Pakistan, but also on hoardings celebrating national holidays.

Spain

[image error]In Spain, Corona, or Coronas, was primarily associated with various wines. It is perhaps best known in its incarnation in the well-known Familia Torres wine Coronas, which was trademarked as long ago as 1907 by Juan Torres Casals, and is one of the oldest trademarks in the Spanish wine industry. Today, Torres’ Coronas wine is made mainly from Tempranillo with a small amount of additional Cabernet Sauvignon. However, Corona in Spanish merely means “crown”, and so the word has also been used for other wines, as in the Corona de Aragón wines, most notably made from Garnacha grapes (produced by Grandes Vinos).

Egypt

[image error]In complete contrast, Egyptians thought that Corona was a type of chocolate biscuit (thanks so much to Leila Hassan for sharing this). Corona was established in Ismailia in 1919 by Tommy Christo (the son of a Greek businessman), as the first confectionery and chocolate company in the Egyptian market. Corona was nationalised in 1963, and then sold to the Sami Saad Group in 2000. For some, the association with “Bimbo” reminds them of a roadside café on Route E6 in Mo i Rana in Norway of the same name (thanks Ragnvald Larsen), which provides a neat introduction to that country…

Norway

[image error]To be fair, very few people made the above connection. However, the café takes its name from the baby elephant in the Circus Boy series (1956-58) and has persisted since the café first opened in 1967. Moreover, the Norwegian krone is pronounced in a similar way to the word corona, and as Tono Armas has pointed out in Spanish it is even called “Corona noruega“.

Japan

[image error]The Corona Corporation in Japan traces its origins back to the founding of kerosene cooking stiove factory in Sanjo, Niigata Pref., by Tetsuei Uchida in 1937. In the late 1970s it entered the air conditioning market, and has subsequently diversified into a range of fan heaters as well as nano-mist saunas and geothermal hybrid hot water systems (Thanks so much to Yutaka Sato for sharing this).

USA/California

[image error]I am never sure whether California should be seen as distinct from the USA, but for those who live there Corona is a town of about 150,000 people in Riverside County. It was originally called South Riverside, and was founded during California’s citrus boom in the 1880s. It was once called “The Lemon Capital of the World” (by USAns), and today is perhaps best known (at least by musicians) for being where the flagship factory, Custom Shop and headquarters of Fender guitars was established in 1985.

USA/Utah

[image error]

Corona Arch, Utah, USA

One of the most striking “Coronas” is the sandstone Corona Arch in a side canyon of the Colorado Rover west of Moab in Utah, which was once known as Little Rainbow Bridge. This had become a renowned site for rope swinging. A three mile hiking trail includes Corona Arch and nearby Bowtie Arch.

Astronomers

[image error]For astronomers, of course, a corona is the aura of plasma that surrounds stars including the sun. More simply, it can be considered as the outer layer of the Sun’s atmosphere that extends millions of miles into space, and generates the solar wind that travels across our solar system. It is difficult to see because it is hidden by the brightness of the sun, but is clearly visible during a total solar eclipse.

Geologists

[image error]

Image from https://www.alexstrekeisen.it

For geologists, a corona is a microscopic band of minerals, usually found in a radial arrangement around another mineral. More generally, it is a term applied to the outcome ofreactions at the rims of structures, where a change in metamorphic conditions can create porphyroblast growth or partial replacement of some minerals by others.

Do please share more thoughts on your memories of Corona before Covid-19.

March 10, 2020

Warsaw: lest we forget…

Images on the garden perimeter at the Warsaw Uprising Museum

Participating in the 12th TIME Economic Forum in Warsaw, especially on a day when the Government prohibited the holding of such large-scale events (because of Covid-19), provided an opportunity to visit and reflect on some of the city’s history, and indeed the history of Poland more generally. It was a stark reminder of human inhumanity. It was also, though, an opportunity to appreciate the efforts made in Europe since 1945, and especially through the creation of the European Union, to try to ensure that such almost unbelievable horrors do not happen again in our continent. We should surely do more not to promote them in other parts of the world.

Katyn

I began by reflecting on the implications of the Katyn Massacre in 1940 when some 22,000 Polish officers and members of the intelligentsia were massacred by the Soviet People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) at the instigation of Lavrentiy Beria and with Stalin’s approval. Although Katyn is some 850 kms to the east of Warsaw, I still find it hard to believe that so many countries were complicit in the Soviet denial of this atrocity, even if this was in the broader interests of retaining Soviet support in the war against Nazi Germany. The elimination of so many leading military and academic figures (including half the Polish officer corps as well as 20 university professors, 300 physicians; several hundred lawyers, engineers, and teachers; and more than 100 writers and journalists) makes the Polish intellectual resurgence in the second half of the 20th century all the more remarkable. It is hard to think that I first hosted a Polish academic colleague in the UK (Prof Wiesław Maik from the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń) 36 years ago and only 44 years after the massacre. Then, and in my subsequent meetings with academic colleagues from Poland, I have always been impressed by their rigour and commitment.

The Warsaw Ghetto

Not much remains of the Ghetto in the vibrant modern city of Warsaw with its new high-rise business centre. But hidden away, almost invisible, tiny traces can be found. I am grateful to a friend for pointing out where I could find an old gate to the Ghetto at the intersection of Grzybowska and Żelazna streets.

Click to view slideshow.

The wall surrounding the Warsaw Ghetto began to be constructed in April 1940, and consisted initially of some 307 hectares, but was gradually reduced in size, making life inside ever more miserable. It is very hard today to envisage the horrors that the Jews living inside had to face. It was from here that they were deported by the Nazis to concentration camps, with some 254,000 Ghetto residents being sent to Treblinka in the summer of 1942. By the time it was demolished in May 1943 following the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, it is estimated that at least 300,000 Jewish inhabitants had been killed, with some 92,000 dying of hunger and related diseases.

The Warsaw Uprising

Nearby the remnants of the Ghetto wall is the museum of the 63 day Warsaw Uprising in August-October 1944 (sadly closed when I tried to visit). This was the largest uprising by any European resistance group during the 1939-45 war, and was timed to coincide with the retreat of the German army in the face of the Soviet advance. However, the Soviet Army did not continue its progress, which gave the German army time to regroup, crush the Uprising, and subsequently largely destroy the city of Warsaw. Despite some support from British and US forces, the uprising was doomed to failure without the continued advance of the Soviet forces. It has been estimated that 16,000 Polish resistance fighters were killed, with around 6,000 more being badly wounded; somewhere between 150,000 and 200,000 civilians are also estimated to have been killed, mainly in mass executions. On a sunny day, at the edge of the modern business centre of Warsaw, it is hard to imagine the horrors and violence of what happened.

The destruction and rebirth of the old city of Warsaw

Following the Uprising, the Germans implemented what had been a long-intended plan to destroy the city as part of its Germanization of Central Europe. They had even drawn up designs (by Hubert Gross) to create a “New German City of Warsaw” as early as 1939. However, although they must have known in 1944 that they would soon be defeated, and there was then little to be gained from destroying the city, they nevertheless proceeded to raze it to the ground in vengeance for the Uprising. Between September 1944 and January 1945, some 85-90% of all the buildings in Warsaw were destroyed. The scale of devastation is only too visible from the many photographs taken following Hitler’s defeat, and can be seen on various plaques in the city following its designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980.

With amazing energy, the Polish people set about rebuilding the old city between the late-1940s and the 1970s, and as the imahges below attest it is hard today to believe that everything we see now is less than 80 years old.

Click to view slideshow.

Seeing the modern city of Warsaw, alongside its ancient heart once again beating strongly, I find it incredibly difficult to comprehend the horrors and violence experienced by the Polish people, especially during the 1939-45 war. I have always been impressed by the diligence, generosity and energy of the friends I have made from Poland, and those of us in Britain should all be grateful to them for their contribution to our economy in recent years. Being here makes me realise once again the tremendous strides we have made in Europe during my lifetime – one of the longest periods of prolonged peace in the continent’s history. This owes much to the work of those who sought to rebuild the continent after 1945, and to the activities of the various European institutions that they constructed, not least the European Union. It makes me even more sad that so many people in Britain chose to follow those of our so-called leaders who for their own selfish interests and political ambitions sought to separate us from the EU in the forlorn hope that Britain might once again be “Great” (alone). We must never forget the enormous sacrifices made by so many people that we might live in peace. I for one am grateful to have had this opportunity to be reminded once again of the sacrifices made by the Polish people, and am privileged to have had the chance to express my own thanks by participating in the TIME Economic Forum, which captured so well the economic vibrancy and energy that characterise Poland in the 21st century. Dziękuję…

[image error]

Dance during the TIME gala dinner

March 6, 2020

The Douro and Vila Nova de Gaia in late February: remembering friends

It was wonderful to be back in northern Portugal last week after many years of absence. The sights, smells, and tastes resurfaced numerous poignant memories. There have certainly been huge changes, not least the vast network of motorways, and generally increased affluence. Many of these have been for the better. However, much also remains the same, and it was wonderful to visit old haunts – even finding one or two places scarcely changed. It is now only a two-hour drive from Porto up to Pinhão at the heart of the best grape growing areas for port wine, and so on a bright sunny morning we headed up there, swiftly crossing the Minho, climbing up into the Serra do Alvão, and then dropping down from Vila Real towards the Douro river. I hope that the images below catch something of the very special character of this part of the Douro Valley – and the grapes that are cultivated there.

Click to view slideshow.

Vila Nova de Gaia, opposite Porto near the mouth of the Douro, has traditionally formed the second integral part of the port trade, providing space for the lodges where the wines are matured. The blue skies turned to clouds, mist and rain the next day, but this did not detract from the pleasure of revisting lodges (where port is matured) that I had first explored some 40 years ago. The narrow streets winding down the hill through the lodges to the river below hadn’t changed, but the corporate structure of the “trade” certainly has, with once proudly independent family firms now being integrated into a small handful of larger companies.

Click to view slideshow.

The ghosts of close friends, many no longer with us, haunt these familiar locations. They were so hospitable to generations of geography students (and staff!) from Durham University and Royal Holloway, University of London, with whom they shared their experiences of the port trade – as well as their wonderful wines both in the Douro and down at Vila Nova de Gaia. Thanks are especially due to Bruce Guimaraens and John Burnett – from whom I learnt so much – and are sadly no longer with us. But walking back past Quinta da Foz and the Cálem lodges also reminds me of many great times with Maria da Assunção Street Cálem learning from her about the business of port from a Portuguese perspective – and being challenged about the role of acacdemics undertaking research in other countries.

Port is one of the world’s great wines, but remains sadly unfashionable today. It is time for more of us to continue to sings its praises – from the freshness of dry white port, or the nuttiness and subtlety of a fine 20 year old tawny, to the unique character of great vintage ports!

[image error]

February 17, 2020

The attitudes and behaviours of men towards women and technology in Pakistan

Gender digital equality, however defined, is globally worsening rather than improving. This is despite countless initiatives intended to empower women in and through technology. In part, this is because most such initiatives have been developed and run by and for women. When men have been engaged, they have usually mainly been incorporated as “allies” who are encouraged to support women in achieving their strategic objectives. However, unless men fundamentally change their attitudes and behaviours to women (and girls) and technology, little is likely to change. TEQtogether (Technology Equality together) was therefore founded by men and women with the specific objective to change these male attitudes and behaviours. It thus goes far beyond most ally-based initiatives, and argues that since men are a large part of the problem they must also be an integral part of the solution. TEQtogether’s members seek to identify the best possible research and understanding about these issues, and to incorporate it into easy to use guidance notes translated into various different languages. Most research in this field is nevertheless derived from experiences in North America and Europe, and challenging issues have arisen in trying to translate these guidance notes into other languages and cultural contexts. TEQtogether is now therefore specifically exploring male attitudes and behaviours towards women and digital technologies in different cultural contexts, so that new culturally relevant guidance notes can be prepared and used to change such behaviours, as part of its contribution to the EQUALS global initiative on incresing gender digital equality.

[image error]

Meeting of EQUALS partners in New York, September 2018

Pakistan is widely acknowledged to be one of the countries that has furthest to go in attaining gender digital equality. Gilwald, for example, emphasises that Pakistan has a 43% gender gap in the use of the Internet and a 37% gap in ownership of mobile phones (in 2017). Its South Asian cultural roots and Islamic religion also mean that it is usually seen as being very strongly patriarchal. In order to begin to explore whether guidance notes that have developed in Europe and North America might be relevant for use in Pakistan, and if not how more appropriate ones could be prepared for the Pakistani content, initial research was conducted with Dr. Akber Gardezi in Pakistan in January and February 2020. This post provides a short overview of our most important findings, which will then be developed into a more formal academic paper once the data have been further analysed.

Research Methods

The central aim of our research was better to understand men’s attitudes and behaviours towards women and technology in Pakistan, but we were also interested to learn what women thought men would say about this subject. We undertook 12 focus groups (7 for men only, 4 for women only, and one mixed) using a broadly similar template for both men and women, that began with very broad and open questions and then focused down on more specific issues. The sample included university students and staff studying and teaching STEM subjects (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics), tech start-up companies, staff in small- and medium-sized enterprises, and also in an established engineering/IT company. Focus groups were held in Islamabad Capital Territory, Kashmir, Punjab and Sindh, and they were all approximately one hour in duration. We had ideally wanted each group to consist of c.8-12 people, but we did not wish to reject people who had volunteered to participate, and so two groups had as many as 19 people in them. A total of 141 people participated in the focus groups. The men varied in age from 20-41 and the women from 19-44 years old. All participants signed a form agreeing to their participation, which included that they were participating voluntarily, they could withdraw at any time, and they were not being paid to answer in particular ways. They were also given the option of remaining anonymous or of having their names mentioned in any publications or reports resulting from the research. Interestingly all of the 47 women ticked that they were happy to have their names mentioned, and 74 of the 94 men likewise wanted their names recorded. The focus groups were held in classrooms, a library, and company board rooms. After some initial shyness and uncertainty, all of the focus groups were energetic and enthusiastic, with plenty of laughter and good humour, suggesting that they were enjoyed by the participants. I very much hope that was the case; I certainly learnt a lot and enjoyed exploring these important issues with them.

This report summarises the main findings from each section of the focus group discussions: broad attitudes and behaviours by men towards the use of digital technologies by women; how men’s attitudes and behaviours influence women’s and girls’ access to and use of digital technologies at home, in education, and in their careers; whether any changes in men’s attitudes and behaviours towards women and technology are desirable, and if so how might these be changed. In so doing, it is very important to emphasise that although it is possible to draw out some generalisations there was also much diversity in the responses given. These tentative findings were also discussed in informal interviews held in Pakistan with academics and practitioners to help validate their veracity and relevance.

I am enormously grateful to all of the people in the images below as well as the many others who contributed to this research.

Click to view slideshow.

Men’s attitudes and behaviours towards the use of digital technologies by women in Pakistan

When initially asked in very general terms about “women” and “digital technology” most participants had difficulty in understanding what was meant by such a broad question. However, it rapidly became clear that the overall “culture” of Pakistan was seen by both men and women as having a significant impact on the different ways in which men and women used digital technologies. Interestingly, whilst some claimed that this was because of religious requirements associated with women’s roles being primarily in the sphere of the home and men’s being in the external sphere of work, others said that this was not an aspect of religion, but rather was a wider cultural phenomenon.

Both men and women concurred that traditionally there had been differences between access to and use of digital technologies in the past, but that these had begun to change over the last five years. A distinction was drawn between rural, less well educated and lower-class contexts, where men tended to have better access to and used digital technologies more than women, and urban, better educated and higher-class contexts where there was greater equality and similarity between access to and use of digital technologies.

Whilst most participants considered that access to digital technologies and the apps used were broadly similar between men and women, both men and women claimed that the actual uses made of these technologies varied significantly. Men were seen as using them more for business and playing games, whereas women used them more for online shopping, fashion and chatting with friends and relatives. This was reinforced by the cultural context where women’s roles were still seen primarily as being to manage the household and look after the children, whereas men were expected to work, earning money to maintain their families. It is very important to stress that variations in usage and access to technology were not always seen as an example of inequality, but were often rather seen as differences linked to the Pakistan’s culture and social structure.

Such views are changing, but both men and women seemed to value this cultural context, with one person saying that “it is as it is”. Moreover, there were strongly divergent views as to whether this was a result of patriarchy, and thus dominated by men. Many people commented that although the head of the household, almost always a man, provided the dominant lead, it was also often the mothers who supported this or determined what happened within the household with respect to many mattes, including the use of technology.

In the home, at school and university, and in the workplace

Within the home

Most respondents initially claimed that there was little difference in access to digital technologies between men and women in the home, although as noted above they did tend to use them in different ways. When asked, though, who would use a single phone in a rural community most agreed that it would be a male head of household, and that if they got a second phone it would be used primarily by the eldest son. Some, nevertheless, did say that it was quite common for women to be the ones who used a phone most at home.

Participants suggested that similar restrictions were placed on both boys and girls by their parents in the home. However, men acknowledged that they knew more about the harm that could be done through the use of digital technologies, and so tended to be more protective of their daughters, sisters or wives. Participants were generally unwilling to indicate precisely what harm was meant in this context, but some clarified that this could be harassment and abuse. The perceived threats to girls and young women using digital technologies for illicit liaisons was also an underlying, if rarely specifically mentioned, concern for men. There was little realisation though that it was men who usually inflicted such harm, and that a change of male behaviours would reduce the need for any such restrictions to be put in place.

A further interesting insight is that several of the women commented that their brothers are generally more knowledgeable than they are about technology, and that boys and men play an important role at home in helping their sisters and mothers resolve problems with their digital technologies.

At school and university

There was widespread agreement among both men and women that there was no discrimination at school in the use of digital technologies, and that both boys and girls had equal access to learning STEM subjects. Nevertheless, it is clear that in some rural and isolated areas of Pakistan, as in Tharparkar, only boys go to school, and that girls remain marginalised by being unable to access appropriate education.

[image error]

Boys in rural school in Tharparkar

Furthermore, it was generally claimed that both girls and boys are encouraged equally to study STEM subjects at school, and can be equally successful. Some people nevertheless commented that girls and boys had different learning styles and skill sets. Quite a common perception was that boys are more focused on doing a few things well, whereas girls try to do all of the tasks associated with a project and may not therefore be as successful in doing them all to a high standard.

There were, though, differing views about influences on the subjects studied by men and women at university. Again, it was claimed that the educational institutions did not discriminate, but parents were widely seen as having an important role in determining the subjects studied at university by their children. Providing men can gain a remunerative job, their parents have little preference over what degrees they study, but it was widely argued that traditionally women were encouraged to study medicine, rather than engineering or computer science. Participants indicated that this is changing, and this was clearly evidenced by the number and enthusiasm of women computer scientists who participated in the focus groups. Overall, most focus groups concluded with a view that generally men studied engineering whereas women studied medicine.

In the workplace

There is an extremely rapid fall-off in the number of women employed in the digital technology sector, even if it is true that there is little discrimination in the education system against women in STEM subjects. At best, it was suggested that only a maximum of 10% of employees in tech companies were women. Moreover, it was often acknowledged that women are mainly employed in sales and marketing functions in such companies, especially if they are attractive, pale skinned and do not wear a hijab or head-scarf. This is despite the fact that many very able and skilled female computer scientists are educated at universities, and highly capable and articulate women programmers participated in the focus groups.

[image error]

Women employed in the tech sector in Pakistan

Part of the reason for this is undoubtedly simply the cultural expectation that young women should be married in their early 20s and no later than 25. This means that many women graduates only enter the workforce for a short time after they qualify with a degree. Over the last decade overall female participation in the workforce in Pakistan has thus only increased from about 21% to 24%, and has stubbornly remained stable around 24% over the last five years.

Nevertheless, the focus groups drilled down into some of the reasons why the digital technology sector has even less participation of women in it than the national average. Four main factors were seen as particularly contributing to this:

The overwhelming factor is that much of the tech sector in Pakistan is based on delivering outsourced functions for US companies. The need to work long and antisocial hours so as to be able to respond to requests from places in the USA with a 10 (EST) – 13 (PST) hour time difference was seen as making it extremely difficult for women who had household and family duties to be able to work in the sector. There was, though, also little recognition that this cultural issue might be mitigated by permitting women to work from home.

Moreover, both men and women commented that the lack of safe and regular transport infrastructure made it risky for women to travel to and from work, especially during the hours of darkness. The extent to which this was a perceived or real threat was unclear, and there was little recognition that most threats to women are in any case made by men, whose behaviours are therefore still responsible.

A third factor was that many offices where small start-up tech companies were based were not very welcoming, and had what several people described as dark and dingy entrances with poor facilities. It was recognised that men tended not to mind such environments, because the key thing for them was to have a job and work, even though these places were often seen as being threatening environments for women.

Finally, some women commented that managers and male staff in many tech companies showed little flexibility or concerns over their needs, especially when concerned with personal hygiene, or the design of office space, As some participants commented, men just get on and work, whereas women like to have a pleasant communal environment in which to work. Interestingly, some men commented that the working environment definitely improved when women were present.

It can also be noted that there are very few women working within the retail and service parts of the digital tech sector. As the picture below indicates this remains an environment that is very male dominated and somewhat alienating for most women.

[image error]

Digital technology retail and service shops in Rawalpindi

Changing men’s attitudes and behaviours towards women and technology

The overwhelming response from both men and women to our questions in the focus groups was that it is the culture and social frameworks in Pakistan that largely determine the fact that men and women use digital technologies differently and that there are not more women working in the tech sector. Moreover, this was not necessarily seen as being a negative thing. It was described as being merely how Pakistan is. Many participants did not necessarily see it as being specifically a result of men’s attitudes and behaviours, and several people commented that women also perpetuate these behaviours. Any fundamental changes to gender digital inequality will therefore require wider societal and cultural changes, and not everyone who participated in the focus groups was necessarily in favour of this.

It was, though, recognised that as people in Pakistan become more affluent, educated and urbanised, and as many adopt more global cultural values, things have begun to change over the last five years. It is also increasingly recognised that the use of digital technologies is itself helping to shape these changed cultural values.

A fundamental issue raised by our research is whether or not the concern about gender digital equality in so-called “Western” societies actually matters in the context of Pakistan. Some, but by no means all, clearly thought that it did, although they often seemed more concerned about Pakistan’s low ranking in global league tables than they did about the actual implications of changing male behaviour within Pakistani society.

Many of the participants, and especially the men, commented that they had never before seriously thought about the issues raised in the focus groups. They therefore had some difficulty in recommending actions that should be taken, although most were eager to find ways through which the tech sector could indeed employ more women. Both men and women were also very concerned to reduce the harms caused to women by their use of digital technologies.

The main way through which participants recommended that such changes could be encouraged were through the convening of workshops for senior figures in the tech sector building on the findings of this research, combined with much better training for women in technology about how best to mitigate the potential harm that can come to them through the use of digital technologies.

Following the main focus group questions, some of the participants expressed interest in seeing TEQtogether’s existing guidance notes. Interestingly, they commented that many of the generalisations made in them were indeed pertinent in the Pakistani context, although some might need minor tweeking and clarification when translated into Urdu.

However, two specific recommendations for new guidance notes were made:

Tips for CEOs of digital tech companies who wish to attract more female programmers and staff in general; and

Guidance for brothers who wish to help their sisters and mothers gain greater expertise and confidence in the use of digital technologies.

These are areas that we will be working on in the future, and hope to have such guidance notes prepared in time for future workshops in Pakistan in the months ahead.

Several men commented that improving the working environment for women in tech companies, and enabling more flexible patterns of work would also go some way to making a difference. Some commented how having more women in their workplaces had already changed their behaviours for the better.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to colleagues in COMSATS University Islamabad (especially Dr. Tahir Naeem) and the University of Sindh (especially Dr. M.K. Khatwani) for facilitating and supporting this research. We are also grateful to those in Riphah International University (especially Dr. Ayesha Butt) and Rawalpindi Women University (especially Prof Ghazala Tabassum), as well as those companies (Alfoze and Cavalier) who helped with arrangements for convening the focus groups. Above all, we want to extend our enormous thanks to all of the men and women who participated so enthusiastically in this research. It was an immense pleasure to work with you all.

Sey, A. and Hafkin, N. (eds) (2019) Taking Stock: Data and Evidence on Gender Equality in Digital Access, Skills, and Leadership, Macau and Geneva: UNU-CS and EQUALS; OECD (2019) Bridging the Digital Gender Divide: Include, Upskill, Innovate, Paris: OECD;

See for example the work of EQUALS which seeks to bring together a coalition of partners working to reduce gender digital equality.

See for example, Manry, J. and Wisler, M. (2016) How male allies can support women in technology, TechCrunch; Johnson, W.B. and Smith, D.G. (2018) How men can become better allies to women, Harvard Business Review.

Especial thanks are due to Silvana Cordero for her important contribution on the specific challenges of translation in Spanish in the Latin American context.

Siegmann , K.A. (no date) The Gender Digital Divide in Rural Pakistan: How wide is it & how to bridge it? Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI)/ISS; Tanwir, M. and Khemka, N. (2018) Breaking the silicon ceiling: Gender equality and information technology in Pakistan, Gender, Technology and Development, 22(2), 109-29; see also OECD (2019) Endnote 1.

Gilwald, A. (2018) Understanding the gender gap in the Global South, World Economic Forum,

Chauhan, K. (2014) Patriarchal Pakistan: Women’s representation, access to resources, and institutional practices, in: Gender Inequality in the Public Sector in Pakistan. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

This research builds on our previous research in Pakistan published as Hassan, B, and Unwin, T. (2017) Mobile identity construction by male and female students in Pakistan: on, in and through the ‘phone, Information Technologies and International Development, 13, 87-102; and Hassan, B., Unwin, T. and Gardezi, A. (2018) Understanding the darker side of ICTs: gender, harassment and mobile technologies in Pakistan, Information Technologies and International Development, 14, 1-17.

All names will be listed with appreciation in reports submitted for publication.

Our previous research (Hassan, Unwin and Gardezi, 2018) provides much further detail on the precise types of sexual abuse and harassment that is widespread in Pakistan.

https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Pakistan/Female_labor_force_participation/

February 7, 2020

Inter Islamic Network on IT and COMSATS University workshop on ICT for Development: Mainstreaming the Marginalised

[image error]The 3rd ICT4D workshop convened by the Inter Islamic Network on IT (INIT) and COMSATS University in Islamabad, and supported by the UNESCO Chair in ICT4D (Royal Holloway, University of London) and the Ministry of IT and Telecom in Pakistan on the theme of Mainstreaming the Marginalised was held at the Ramada Hotel in Islamabad on 28th and 29th January 2020. This was a very valuable opportunity for academics, government officials, companies, civil society organisations and donors in Pakistan to come together to discuss practical ways through which digital technologies can be used to support economic, social and political changes that will benefit the poorest and most marginalised. The event was remarkable for its diveristy of participants, not only across sectors but also in terms of the diversity of abilities, age, and gender represented. It was a very real pleasure to participate in and support this workshop, which built on the previous ones we held in Islamabd in 2016 and 2017.

The inaugural session included addresses by Prof Dr Raheel Qamar (President INIT and Rector COMSATS University, Islamabad), Mr. Shoaib Ahmed Siddiqui (Federal Secretary Ministry of IT & Telecom) and Dr. Tahir Naeem (Executive Director, INIT), as well as my short keynote on Digital Technologies, Climate Change and Sustainability. This was followed by six technical sessions spread over two days:

Future of learning and technology

Policy to practice: barriers and challenges

Awareness and inclusion: strategizing through technology

Accessibility and Technology: overcoming barriers

Reskilling the marginalised: understandng role reversals

Technical provisio: indigenisation for local needs.

These sessions included a wide diversity of activities, ranging from panel sessions, practical demonstrations, and mind-mapping exercises, and there were plenty of opportunities for detailed discussions and networking.

Highlights for me amongst the many excellent presentations included:

Recollections by Prof Abdful Mannan and Prof Ilyas Ahmed of the struggles faced by people with disabilities in getting their issues acknowledged by others in society, and of the work that they and many others have been doing to support those with a wide range of disabilities here in Pakistan

The inspirational presentations by Julius Sweetland of his freely available Open Source Optikey software enabling those with multiple disbilities to use only their eyes to write and control a keyboard

Meeting the young people with Shastia Kazmi (Vision 21 and Founder of Little Hands), who have gained confidence and expertise through her work and are such an inspiration to us all in continuing our work to help some of the pooorest and most marginalised to be empowered through digital technologies.

The very dynamic discussions around practical actiona that we can all take to enable more inclusive use of digital technologies (mindmaps of these available below)

How can we best change men’s attitudes and behaviours so that gender digital equality improves in Pakistan?

How can digital technologies be used better to support learning in deprived contexts?

Enormous thanks must go to Dr. Tahir Naeem (COMSATS University and Executive Director of INIT) and his team, especially Dr. Akber Gardezi and Atiq-ur-Rehman, for all that they did to make this event such a success.

Quick links to outputs:

My short keynote on Digital Technologies, Climate Change and Sustainability.

How can we best change men’s attitudes and behaviours so that gender digital equality improves in Pakistan?

How can digital technologies be used better to support learning in deprived contexts?

January 16, 2020

Digital technologies and climate change, Part III: Policy implications towards a holistic appraisal of digital technology sector

This is the third of a trilogy of posts on the interface between digital technologies and “Climate Change”. Building on the previous discussion of challenges with the notion of “climate change” and the anti-sustainability practices of the digital technology sector, this last piece in the trilogy suggests policy principles that need to be put in place, as well as some of the complex challenges that need to be addressed by those who do really want to address the negative impact of digital technologies on the environment.

[image error]

To be sure, various global initiatives have been put in place to try to address some of the challenges noted above, and the impact of digital technologies on “Climate Change” is being increasingly recognised, although much less attention is paid to its impact on wider aspects of the environment. One challenge with many such global initiatives is that they have tended to suffer from an approach that fragments the fundamental problems associated with the environmental impact of digital technologies into specific issues that can indeed be addressed one at a time. This is problematic, as noted in the previous two parts of this commentary, because addressing one issue often causes much more damage to other aspects of the environment.

As I have noted elsewhere, the Global e-Sustainability Initiative (GeSI) is one of the most significant such initiatives, having produced numerous reports, as well as a Sustainability Assessment Framework (SASF) that companies and organisations can use to evaluate their overall sustainability. This has three main objectives:

“Strengthen ICT sector as significant player for achieving sustainable development goals

Enable companies to evaluate and improve their product portfolios with a robust and comprehensive instrument

Address sustainability issues of products and services in a coherent manner providing the basis for benchmarking and voluntary agreements”.

However, GeSI is made up almost exclusively of private sector members, and is primarily designed to serve corporate interests as the wording of the above objectives suggests. Typically, for example, it has shown clearly how companies can reduce their carbon imprint, and many are now beginning to do so quite effectively, but the unacknowledged impact of their behaviour on other aspects of the environment is often down-played. Little of their work has, for example, yet included the impact of satellites on the environment. Likewise, it has failed to address the fundamentally anti-sustainable business model on which much of the sector is based.

Similarly, civil society organisations have also tended to fragment the digital-environment into a small number of parts for which it is relatively easy to gather quantifiable data. Thus, Greenpeace’s greener electronics initiative focuses exclusively on energy use, resource consumption and chemical elimination. These are important, though, showing that most digital companies that they analysed have a very long way to go before they could be considered in any way “green”; in 2017 only Fairphone (B) and Apple (B-) came anywhere near showing a shade of green in their ranking. Recent work by other organisations such as the carbon transition think tank The Shift Project has also begun to suggest ways through which ICTs can become a more effective part of the solution to the environmental impact of ICTs rather than being part of the problem as it is at present, although usually primarily from a carbon-centric perspective focusing on climate change.

These observations, alongside those in Parts I and II, give rise to at least seven main policy implications:

Above all, it is essential that a much more holistic approach is adopted to policies and practices concerning the environmental impact of digital technologies.

These must go far beyond the current carbon fetish and include issues as far reaching as landscape change, the use of satellites and the negative environmental impacts of renewable energy provision. There is a long tradition of research and practice on Environmental Impact Analysis that could usefully be drawn upon more comprehensively in combination with the ever-expanding, but more specific, attention being paid purely to “Climate Change”.

Such assessments need to weigh up both the positive and the negative environmental impacts of digital technologies.

This issue is discussed further below, but there needs to be much more responsible thinking about how we evaluate the wider potential impact of one kind of technology, which might do harm directly, although offering some beneficial solutions more broadly.

The fundamental anti-sustainability business models and practices of many companies in the digital technology sector must be challenged and changed.

The time has come for companies that claim to be doing good with respect to carbon emissions, but yet remain bound by a business approach that requires ever more frequent new purchases, need to be called to task. Companies that maintain restrictive policies towards repairing devices must be challenged. Mindsets need to change so that there is complete re-conceptualisation of how consumers and companies view technology. Laptops, tablets and phones should, for example, be designed in ways that could allow them to be kept in use for a decade rather than a few years. Until then, much of the rhetoric about ICTs contributing to sustainable development remains hugely hypocritical.

There needs to be fundamental innovation in the ways that researchers and practitioners theorize and think about the environmental impact of digital technologies.

It will be essential for all involved to create new approaches and methodologies in line with the emphasis on a holistic approach to understanding the environmental impact of digital technologies noted above. Only then will it be possible to avoid the piecemeal and fragmented approach that still dominate today, and thus move towards the use of technologies that can truly be called sustainable.

In turn, it is likely that such new theorizing will have substantial implications for data.

Much work on the climate impact of digital technologies is shaped by existing data that have already been produced. New models and approaches are likely to require new data to be created.

It is important that there is open and informed public debate about the real impacts of digital technologies on the wider environment, and not just on climate.