Tim Unwin's Blog, page 4

June 21, 2022

Environmental impact of digital tech: spectrum environmental efficiency

It was a real pleasure to join the Wireless World Research Forum’s (WWRF) 47th meeting held at the University of Bristol today, where at the invitation of Knud Erik Souby I presented a short paper entitled “Environmental impact of digital tech: spectrum environmental efficiency“. This provided a broad introduction to the reseach agenda of the Digital Environment System Coalition (DESC) Working Group on spectrum environmental efficiency.

In essence, the paper

emphasised the substantial amount of existing research on spectrum efficiency and energy efficiency;highlighted the lack of existing research on “spectrum environmental efficiency” (rather than just on energy);reflected on the observation that, although 5G is widely seen as being more energy efficient, the total increase in traffic (and sensors) means that 5G systems as a whole require more energy than was the case with previous wireless generations;emphasised the importance of future wireless generations being designed to reduce environmental harms;outlined aspects of the future research agenda of the working group, including:always taking environmental considerations (not just climate and energy) into our research practice;what are environmental implications of using different parts of the spectrum?how do different masts/antennae impact the environment?new ways of assessing landscape impactenvironmental implications of sensor networkrecommendations for good practices by telecom/wireless companies – and regulatorshelping develop a toolkit for the UN Partner2Connect digital coalitionhow can future wireless generations minimise environmental harms?links with DESC working group on satellites and outer space (with UNOOSA involvement);recognised the importance of listening to and understanding alternative/indigenous knowledges about the environment (and digital tech);noted that the WWRF is a formal partner of DESC; andinvited members of the WWRF, and especially those from the private sector, to join DESC and contribute to our future work.

June 8, 2022

Academic perspectives on WSIS and the SDGs, WSIS 2022

It was a great pleasure to have been invited to contribute as a panellist to Session 406 of the WSIS Annual Forum on 2nd June 2022 on the theme of “Academic perspectives on WSIS and the SDGs”. This was a hybrid event, and as the picture below shows it was sadly not attended by very many people actually in Geneva! (Follow this link for my short, full presentation.)

However there was active participation online, and it was good to share some reflections on the theme. As ever, I tried to be diplomatically provocative, reflecting on my participation in the original World Summit on the Information Society in Geneva (2003) and Tunisia (2005)…

… as well as on many occasions since at the WSIS annual forums, especially when in 2019 I changed WSIS to MISS in front of my good friend Houlin Zhao the Secretary General of the ITU:

… as well as on many occasions since at the WSIS annual forums, especially when in 2019 I changed WSIS to MISS in front of my good friend Houlin Zhao the Secretary General of the ITU:

My presentation in particular emphasised the important need for the UN system to stop replicating and duplicating its efforts to use ICTs for “development” (or should this read “to serve the interests of the rich and powerful” especially the “digital barons“?); it is striking and sad, for example, that the UN Secretary General’s Roadmap for digital cooperation and Our Common Agenda make no mentions at all of the WSIS process.

My main argument was that with only eight years to go, it is essential that we start planning now for what will replace the SDGs, especially with respect to the uses of digital tech.

I did, though, also address to other themes: how academics can indeed benefit from the WSIS process (see below) as well as a short introduction to the work that we are now doing as part of the Digital-Environment System Coalition (DESC).

Follow this link for my short, full presentation.

Follow this link for my short, full presentation.

May 25, 2022

Freedom, enslavement and the digital barons: a thought experiment

It was a delight and a challenge to have the opportunity earlier today to present a keynote for this year’s IFIP 9.4 conference on Freedom and Social Inclusion in a Connected World in the form of a thought experiment on the topic of “Freedom, enslavement and the digital barons“.

My main aim was to explore how thinking about the “unfree” can help us better understand the intersection between freedom and digital tech. In particular I focused on five main themes: some of the ways in which academics have previously considered the concept of freedom within the field of Information and Communication Technologies for Development (ICT4D); ways of understanding “unfreedom”; six examples of digital enslavement; the relationships between freedom, rights and responsibilities; and the ways in which people in general and academics in particular can resist enslavement by the digital barons.

The examples of digital enslavement that I briefly explored were:

Digital addictionWe are the dataGovernments enforcing use of digital systems for government servicesLabour exploitation (through extending the working week)Digital poverty and educationDigital tech contributing to modern slaveryTime precluded the inclusion of several other forms of enslavement that I might have considered. Drawing on my medievalist backgroung, I was especially interested in the role and interests of the Digital Barons.

In part, this keynote drew on arguments that I have previously addressed in more detail in

Prolegomena on Human Rights and ResponsibilitiesThe advantages of being unconnected to the Internet: a thought experiment Reclaiming ICT4DI also made it clear that appropriately designed digital tech can be used to great advantage by poor and marginalised communities, although given the theme of the confernce I concentrated exclusively on “digital enslavement” and the role of the “digital barons”.

The full slide deck (in .pdf format) is available here without the transitions and animations. It also omits the subtitles in Spanish that were included for our colleagues in Peru who had originally been planning to host us in person.

May 23, 2022

On language, gender and digital technologies

I wrote a short post back in 2018 on the gendered languages of ICTs and ICT4D, and partly in the light of this I was very kindly invited to contribute to the fascinating collection of essays edited by Domenico Fiormonte, Sukanta Chaudhuri and Paola Ricaurte on Global Debates in the Digital Humanities, recently published by the University of Minnesota Press.

The short chapter is divided into two parts. The first on language, gender and digital tech is based on the premise that in the broad field of digital technologies, most practitioners have been blind to the gendering of language and thus perpetuate a male-dominated conceptualization of ICT4D. It addresses: the gendering of electronic parts, the use of language in ICT4D, digital technologies represented by male nouns, and computer code: bits and qubits. The second part explores some of my thoughts on the use of the term “frontier technologies”, building on another 2018 blog post.

Male & Female Connectors

Male & Female Connectors

I’m delighted that the publishers have now shared a copy of this with me, and have also given me permission to share it here. The chapter is only seven pages long, but I hope that readers may find that it challenges some of their existing thoughts about aspects of gender and digital tech. I would be delighted to carry on the conversation with anyone who mght be interested…

April 29, 2022

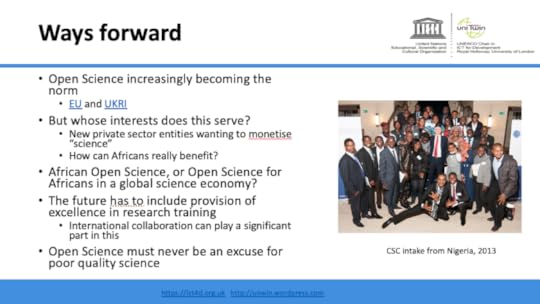

“Open Science” Keynote for WACREN

It was a real privilege to have been invited to give a keynote on “Open Science in Africa and for Africans: addressing the challenges” this morning at the West and Central African Research and Education Network (WACREN) 2022 conference held in Abidjan. The role of a keynote is to provoke and challenge, and so I took the opportunity to share some of the reflections and challenges that I have been struggling with over many years, and especially since I first met the inspirational CEO of WACREN, Boubakar Barry, some 18 years ago in Dakar, Sénégal at an event we participated in on Free/Libre and Open Source Software convened by Imfundo.

Participating online in the hybrid WACREN 2022 conference

Participating online in the hybrid WACREN 2022 conferenceThe six challenges on which I focused in the Keynote were:

Whose interests does Open Science really serve?The rise of individualism: is it too late for communal science?Which models of publication best serve Africa?How valuable are Open Data, and for whom?The dangers of Scientism?Who pays?Underlying my thoughts are two fundamental concerns:

If you don’t have access to, or cannot use “Open Science”, can you really benefit from it? Does “Open Science” really empower the poor and marginalised?Is Open Science mainly a means through which the rich and powerful continue to maintain their positions of privilege? This is typified by the ways through which global corporations and companies persuade governments to make their data about citizens available as Open Data, so that these companies can then extract considerable profit from them.The full slide deck in .pdf format is available here, and the slide below summarises my final thoughts about the ways forward.

March 1, 2022

London International Model UN 2022: A new UN for a New World Order

Delegates at the London International Model UN conference, 25 February 2022

Delegates at the London International Model UN conference, 25 February 2022It was a real privilege to have been invited to give the keynote address at the 2022 London International Model UN conference held at Central Hall, Westminster on 25th February. After much discussion with the organisers we agreed that I would use the occasion to challenge the delegates with some of the problems I see facing the UN as an organisation, and offer some recommendations as to how these can be addressed. With the invasion of Ukraine by Russia the day before, I considered fundamentally revising what I had intended to say, until I realised that much of what I had prepared was even more relevant following the events of the previous 24 hours.

The event was recorded by the organisers, but for those wishing to have an outline of what I said it is available in .pdf format here (with low resolution images). I was delighted to receive so many questions, and I very much hope that my answers were able to provide further insights into my thinking on these matters.

It was a wonderful opportunity to engage in intergenerational dialogue, and I am most grateful to Luna, Savvas and Siddarth, as well as other members of the Secretariat, for all of their organisation and bringing together so many inspirational young people in London to discuss the important issues facing the world today.

The choice of blue and yellow flowers for my “thank you bouquet” was brilliantly appropriate!

February 7, 2022

To app or not to app? How migrants can best benefit from the use of digital tech

IntroductoryThis post was first published on the OECD’s Development Matters site on 7th February 2022, and is reproduced here with permission and under a slightly different title

UN agencies, donors, and civil society organisations have invested considerable time, money and effort in finding novel ways through which migrants, and especially refugees, can benefit from the use of digital technologies. Frequently this has been through the development of apps specifically designed to provide them with information, advice and support, both during the migration journey and in their destination countries. All too often, though, these initiatives have been short-lived or have failed to gain much traction. The InfoAid app, for example, launched by Migration Aid in Hungary amid considerable publicity in 2015 to make life easier for migrants travelling to Europe, posted a poignant last entry on its Facebook page in 2017: “InfoAid app for refugees is being rehauled, so no posting at the moment. Hopefully we will be back soon in a new and improved form! Thank you all for your support!”

However, new apps continue to be developed, drawing on some lessons from past experience. Among the most interesting are MigApp (followed by 93 668 people on Facebook) developed by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) as a one-stop-shop for the most up-to-date information. Another is RedSafe developed by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which enables those affected by conflict, migration and other humanitarian crises to access the services offered by the ICRC and its partners. Other apps seek to be more local and focused, such as Shuvayatra (followed by 114 026 on Facebook), which was developed by the Asia Foundation and its partners to provide Nepali migrant labourers with the tools they need to plan a safer period of travel and work abroad.

Our work with migrants nevertheless suggests that in practice very few migrants in the 12 countries where we are active in Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean, ever use apps specifically designed for migrants. Moreover, most of those who claim to use such apps name them as Facebook, Imo, or WhatsApp, which were never originally intended as “migrant apps”. A fine balance therefore needs to be made when developing relevant interventions in combining the professional knowledge (often top-down) of international agencies with the more bottom-up approaches that focus on the digital tech already used by migrants.

Our wider research goes on to highlight four broad areas for action to complement the plethora of activities around app development:

1. Information sharing and collaborationFirst, there needs to be much more information sharing and collaboration between international organisations working in this field. While an element of competition between agencies may be seen as positive in encouraging innovation, there remains far too much overlap, duplication and reinventing the wheel. The creation of a global knowledge-sharing platform on digital tech and migration could provide a first port of call that any organisation considering developing a new initiative could go to for ideas or potential collaborative opportunities.

2. No one-size-fits-all: diversity in the use of digital tech by migrantsSecond, our research has shown very clearly that use of digital tech by migrants varies considerably in different areas of the world and between different groups of migrants. There is no one-size-fits-all, and context matters. Hence, practitioners should be careful when making generalisations about how “migrants and refugees” use, or want to use, digital tech.

3. Developing digital tech with migrants not for themThird, it is important to remember that actions and policies are much more likely to succeed if they are developed with rather than for migrants. This fundamental principle is too frequently ignored, with well-meaning “outsiders” too often seeking to develop digital interventions for migrants without fully understanding their needs and aspirations. As our own research has shown, though, it is far from easy to appreciate and understand the underlying needs that different groups of migrants prioritise and how best they can be delivered.

4. Assisting migrants to help each other in using digital tech wisely and safelyFourth, it sadly remains as true today as it was twenty years ago that many of the poorest and most marginalised still do not know how to use digital technologies effectively, appropriately, securely and safely. Many migrants contributing to our research own a smartphone or have access to one, but frequently they only have a rudimentary knowledge of how to use it optimally. Some aspire to use digital tech to learn and acquire skills, while others wish to enhance their business opportunities; in both cases, many do not know how best to do so. Few also sufficiently appreciate the very significant security, privacy and surveillance issues associated with using digital tech. The development of basic training courses – preferably face-to-face – may be one of the best investments that can be made in assisting migrants to help themselves when using digital tech.

Looking to the futureLooking to the future, the power relationships involved in the migration process mean it is likely that migrants will become increasingly controlled and subject to surveillance through the use of digital tech. In some circumstances, it might even be wiser for migrants to avoid using any form of digital tech at all. However, there are exciting opportunities to develop novel ways through which migrants might benefit further from digital tech. One of the challenges faced by many migrants is the sadness associated with being away from family and friends. While video calls can go some way to mitigate this, new developments in haptics may soon enable us to feel someone’s touch or hug.

Likewise, inserting microchips into our bodies is becoming increasingly widespread, and in the future this practice could offer real potential for migrants for example to have their qualifications and other documents actually within their bodies, or for their families to be able to track them on the often dangerous journey to their destination. Countering this, of course, is the likelihood that most authorities would use such technologies for surveillance purposes that would threaten migrants’ privacy.

As with all digital tech, it is important to remember that it can be used to do good or to harm. Many migrants are especially vulnerable, and it is incumbent on those seeking to support them that migrants are able to make their own informed decisions on how they choose to use digital tech. Often, the best interventions might well be built around improving existing ways through which migrants use apps and other digital technologies, rather than developing entirely new solutions that may never be widely used.

I am particularly grateful to G. Hari Harindranath and Maria Rosa Lorini, as well as the many other people and migrants with whom we are working, for their contributions to the ongoing research practice on which this post is based.

December 1, 2021

The advantages of being unconnected to the Internet: a thought experiment

The 2021 ITU Facts and Figures report highlighted that 2.9 billion people, or 37% of the world’s population, have still never used the Internet. Implict in this, as in almost all UN initiatives relating to digital technology, is the ideal that everyone should be connected to the Internet. Hence, many global initiatives continue to be designed to create multi-stakeholder (or as I prefer, multi-sector – see my Reclaiming Information and Communication Technologies for Development) partnerships to provide connectivity to everyone in the world. But, whose interests does this really serve? Would the unconnected really be better off if they were connected?

Walking in the Swiss mountains last month, and staying in a place where mobile phones and laptops were prohibited, reminded me of the human importance of being embedded in nature – and that of course we don’t really need always to be digitally connected.

Although I have addressed these issues in many of my publications over the last 20 years, I have never articulated in detail the reasons why people might actually be better off remaining unconnected: hence this thought experiment. There are actually many sound reasons why people should consider remaining unconnected, and for those of us who spend our lives overly connected we should think about disconnecting ourselves as much as possible. These are but a few of these reasons:

Above all, we were born to be a part of the physical world in which we live. Virtual realities may approximate (or even in some senses enhance) that physical world, but they are fundamentally different. Those who spend all of their time connected miss out on all the joys of living in nature; those who are unconnected have the privilege of experiencing the full richness of that nature.Those who are unconnected do not have to waste time sifting through countless boring e-mails or group chats to find what is worthwhile, or the messages in which they are really interested.The unconnected cannot give away for free their valuable data from which global digital corporations make their fortunes.Being unconnected means not harming the physical environment through the heavy demands digital technologies place on our precious natural world (see the work of the Digital-Environment System Coalition – DESC)Those who are unconnected do not suffer the horrors of online harassment or digital violence.The unconnected are not forced by their managers to self-exploit by doing online training once they are home after a day’s work, or answer e-mails/chat messages sent by their managers at all hours of the day and night.Those who are not online don’t have to run the risk of online scams or phishing attacks that steal their savings – and the poor suffer most when, for example, their small amounts of money are stolen.The unconnected can largely escape much of the digital surveillance now promulgated by governments in the name of “security” and “anti-terrorist” action.The unconnected do not suffer from digital addictions to online games, gambling, or pornography.Ultimately, being connected is akin to being enslaved by the world’s digital barons and their corporations; if you cannot stop using digital tech for a few days, let alone a week, surely you have lost your freedom?Despite the fine sounding words of those leading global connectivity initiatives, is it really the poorest and most marginalised who are going to benefit most from being connected? Surely, this agenda of global connectivity is being driven mainly in the interests of the global corporations that will be paid to roll out the tech infrastructre, or that will benefit from exploiting the data that we all too willingly give them for nothing? Does not, for example, digital financial inclusion benefit the financial and tech companies and institutions far more than it does the poorest and most marginalised? This is not to deny that digital tech does indeed have many positive uses, but it is to ask fundamental questions about who benefits most.

I remember visiting a village in Africa with colleagues who couldn’t understand why the inhabitants didn’t want mobile phones. Walking over the hills to see their friends was more important to them than the ease of calling them up. This post owes much to that conversation.

We all need to ask the crucial questions about whose interests our often well-intentioned global digital connectivity initiatives really serve. If we wish to serve the interests of the poorest and most marginalised, we must become their servants and not the servants of the world’s rich and powerful; we must be humble, and learn from those we wish to serve.

And the world’s rich and privileged also need to take care of ourselves; if we have difficulty living a day without being connected, surely we have indeed become enslaved? We need to regain our freedom as fully sentient beings, using all of our senses to comprehend and care for the natural world in which we live. May I conclude by encouraging people to think about using the hashtag #1in7offline. Take one day a week away from digital tech to experience the wonders of our world, unmediated by the paltry digital alternative. Or try taking a week away from the digital world every seven weeks. If you cannot do this, ask yourself why!

November 22, 2021

“We’ve seen it all before”: sketches about why so many digital tech for development initiatives fail

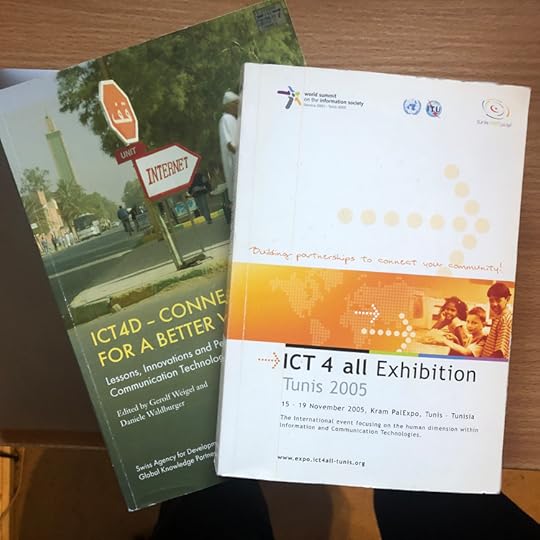

Clearing out boxes of old books and reports recently, I was struck by how many ICT4D (Information and Communication Technologies for Development) initiatives there have been over the last 20 years, many of which have simply repeated the mistakes of their predecessors. Most have failed to make real and significant improvements in the lives of the world’s poorest and most marginalised people. Quick looks at Weigel and Waldburger’s (2004) seminal book, and the ICT4 all Exhibition catalogue for the 2005 WSIS Summit in Tunis, remind us that most of the problems we are addressing in 2021 are broadly similar to those that were being addressed 20 years ago: how to enable the most marginalised to benefit from digital tech; moving from rhetoric to action; how to deliver effective partnerships; the importance of local languages; financing challenges; or how to ensure access…

An invitation to give a lecture at the Aga Khan University in Pakistan as part of a Master’s course on Learning and Teaching with Technology later this week provided me with the opportunity to reflect at some length on this thorny issue, and to come up with some suggestions as to why we continue to reinvent the wheel, and what we need to change if we really want to work with the poorest and most marginalised in delivering effective ICT4D initiatives that will help to empower them.

It also reminded me that even when I first started teaching in universities in the mid-1970s I used multimedia technologies such as slides (diapositives), aerial photos, film clips, overhead transparencies – as well as books. There is very little fundamentally new in the use of ICTs in education; it’s just the detail of the tech that has changed. As long ago as the early 1990s I thus enjoyed delivering lectures to students across London through the University Live-Net TV network, and in the middle of that decade enjoyed participating in the work of the Computers in Teaching Initiative in the UK. Hopefully we had learnt by then many of the challenges and success factors that previous colleagues involved in delivering education at a distance had shared with us.

Why are we failing so badly to learn the lessons of the past?Reflecting on this simple question, I came up with six main suggestions as to why valuable lessons from previous ICT initiatives, especially in the education sector, do not seem to have been sufficiently learnt:

Lack of background research Increased emphasis on innovation The problem with “self”Short-termism Commercialisation and marketisation of education Insufficient intergenerational dialogueI am sure there are many more, and I look forward to exploring these ideas further with interested colleagues. Each needs to be fleshed out in much more detail, but the following brief notes cover some of the aspects that may be of particular importance.

Lack of background researchThe Google (or DuckDuckGo) first page syndromeonly following up links on the first page (or two)only reading the most recently published materialToo many people failing to explore and learn from what has been done beforeToo much of a hurry? Believing only the latest is best? Nothing old is worthwhile? A strong sense of self-belief, and that there is no need to read (see further below) Past research and practice are inaccessible or unavailable but this isn’t really true – many of us have written at length about our previous experiencesProblems with innovationIt is well known that most innovations failalthough estimates of the precise percentage vary (some suggest 95% of new products fail)Overcoming failure often seen as being essential for subsequent successBut surely it’s best not to make the well known mistakes that others have made before? So why is innovation (scientific and business) usually seen as being such a good thing? Many governments (and donors) are increasingly focusing on funding innovation to drive economic growth – should they use taxpayers’ money to fund failure?Might it not be wiser for donors and governments to spread what we know works, say for 60% of the population, to everyone?Reducing inequalities rather than maximising growthThe problem with “self”Self(ish) individualismThe need to be first Overconfidence in own excellence Having great qualifications so must know the truth Unwilling to be self-critical Brought up within the power and culture of non-self-critical scientism A self-congratulatory culture (illustrated by awards processes) Competitive rather than communal culture Enjoys making mistakes in the belief that they will learnVery expensive for others, especially in the international development contextShort-termismShort-term job delivery and then move onIt’s always good to be seen to be bringing in new ideasYou don’t have to pick up the bits because you’ve left by thenThe world of 140 characters Project cycles often very short It’s important to show success even when you’ve done nothing Those who shout loudest tend to get heardEven when there is little substance behind the claimsShort term is much easier than doing something long term Perhaps “Agile” also has something to do with this?The commercialisation and marketisation of educationEdTech is about the technology not the education Everything is about expanding the market Sales driven, with short term targets Pitching to donors A different skill set to delivery Donors have large budgets and also have to show quick gains Unrealistic target setting Pilots where it is easiest Instead they should be done where it is most difficult We are measuring different success factors Connecting a million childrenBut are they the most marginalised, and do they learn anything?Insufficient intergenerational dialogue“Youth have all the answers” Older people have wrecked the world and so should now listen to young people who have all the good ideas Much political posturing The old have no idea how to use digital tech Really?Little priority given to mentoring Especially 360o Even fewer initiatives specifically designed to be inter-generational Youth political institutions often replicate existing flawed global institutions Especially within the UN systemMoving beyond a sketchI have frequently been frustrated when I hear exciting new ideas being advocated about ways through which the latest generation of technologies (be it AI, AR, blockchain, or the Metaverse) can tranform global education for the better. More often than not, the technology is the easy bit. It’s everything else that’s difficult. As a contribution at least to what governments need to get right, we collectively crafted a report on Education for the most marginalised post-COVID-19: Guidance for governmetns on the use of digital technologies in education (freely available under a CC BY licence at https://ict4d.org.uk/technology-and-education-post-covid-19, and https://edtechhub.org/education-for-the-most-marginalised-post-covid-19) which I hope goes some way to sharing global good practices at least in this area. Perhaps we should do similar reports for the private sector and for civil society, although those in these sectors could still learn much from our report for governments.

The above six sets of suggestions are just a beginning, but I wanted to share them here to provoke discussion. Everyone will have their own list of suggestions. What’s missing from the above? I’d be interested to hear from anyone who might like to explore this theme further! I need to learn more! At the very least, I hope that future colleagues will address these suggestions head on and thereby no longer repeat the same mistakes that so many of us have made in the past.

October 27, 2021

Digital for Life?

View of the Eiger, Mönch and Jungfrau from small tarn above Grosse Scheidegg

View of the Eiger, Mönch and Jungfrau from small tarn above Grosse ScheideggIt was a privilege to have been invited to contribute to the panel on Digital for Life? at the Club of Rome’s annual conference today along with luminaries such as Carlos Álvarez Pereira, Ndidi Nnoli-Edozien, Anders Wijkman, Charly Kleissner, Mariana Bozesan and Bolaji Akinboro. I fear, though, that my perspective was a little different from that of many of the panelists who were from a business, financial and entrepreneurial background. It was also challenging to convey the nuances of what I had intended to say in my opening 4 minutes!

So, for anyone who might be interested, I’m posting my speaking notes here. At least, this is more or less what I had intended to say!

Digital for Life?I think of two things when presented with this question:

First, that many of those developing digital technologies and indeed in the biotech sector more widely are working hard to extend human life through digital tech. The work of Calico (subsidiary of Alphabet, Google’s parent company) and Elon Musk’s creation of Neuralink are just two examples (claiming that “that people would need to become cyborgs to be relevant in an artificial intelligence age. He said that a “merger of biological intelligence and machine intelligence” would be necessary to ensure we stay economically valuable”, Guardian , 2017). More widely, the increasing blending of human and digital makes me think that within a relatively short period of time, perhaps already, it will not be possible for “pure humans” to survive, in a world increasingly dominated by cyborgs. For many this does not matter; for others (including me) it does. We need to think such thoughts so that we can debate them openly, thereby enabling people to reach wise judgements as to the kinds of future “we” wish to create. This in turn of course depends on who “we” are, and here I would err on the side of relativism and diversity. I find one single universal “we” frightening; just as I do the idea of universal individual human rights, without the balancing necessary responsibilities to ensure that diverse individuals can live side-by-side (see Unwin, 2014).The second idea I would like to share is that digital technologies are becoming increasingly harmful to life (of all kinds) on planet earth. We need to understand the negatives of technology on nature/earth/the physical environment, as well as the positive potential of its use. This is obviously important in the context of the upcoming COP26 jamboree. Although much effort has been expended on trying to show how digital tech is squeeky-green-clean and can contribute much to a reduction in CO2 and thus “save the planet from climate change”, the truth is much dirtier. Increasing research shows just how anti-sustainable many digital techs are: fast fashion business models (smart-phone life/owned span around a couple of years); companies preventing right to repair; environmentally harmful mining of rare-earth minerals; bitcoin using more energy than Argentina or the Netherlands; satellite pollution of outer space (akin to the way we used to treat the oceans); digital tech creating twice as much carbon emissions as the airline industry; and energy demand spiralling upwards as 5G, AI, smart cities and a world of sensors come to dominate our lives. The Digital-Environment System Coalition (DESC) that I founded earlier this year, and to which anyone is most welcome to join, is committed to rethinking the relationships between digital tech and the life of nature, focusing on both the benefits and the harms that it can be used to create. Page one of the participants

Page one of the participantsWe had a fascinating, albeit attenuated, discussion and I look forward to continuing the exploration. I have much to learn from what others think and say. These are critically important issues if we wish to leave a better world to the next generation, and not have it transformed irrevocably by the scientism of those creating ever more enslaving and destructive digital technologies.

Tim Unwin's Blog

- Tim Unwin's profile

- 1 follower