Tim Unwin's Blog, page 2

November 16, 2023

(Un)Sustainability in the Digital Transformation

It was good to have had the opportunity to share some provocative thoughts around sustainability and the digital transformation in a short keynote for the CMI/AAU, IDA Connect and WWRF conference at Aalborg University in Copenhagen this morning (on 16th November).

Aalborg University Copenhagen

Aalborg University CopenhagenIn summary, I sought to challenge some existing taken for granted (and politically correct) assumptions and rhetoric around digital tech and sustainable development, building around the following outline:

On sustainable development and the UN systemThe dominant global rhetoric on climate change and sustainabilityTowards a more holistic model of understanding the interface between digital tech and the environmentOn growth and innovationExamples of unsustainable digital developmentMany business modelsSpace and the global commonsSpectrum environmental efficiency Illustration by Vilhelm Pedersen of Hans Christian Andersen’s Kejserens nye klæder

Illustration by Vilhelm Pedersen of Hans Christian Andersen’s Kejserens nye klæderThe full slide deck is available here.

October 5, 2023

Remember whatever happens don’t overdo it

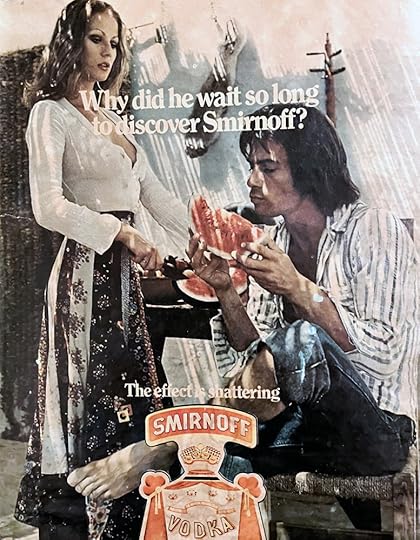

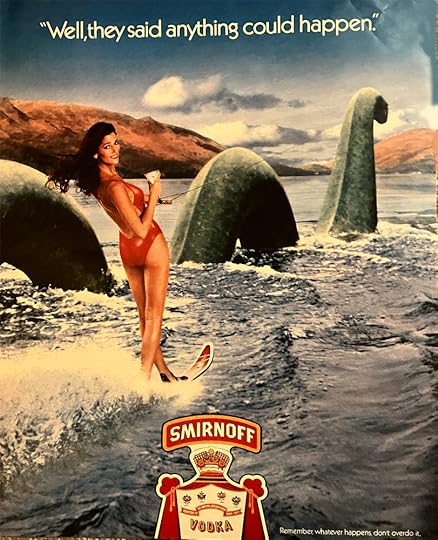

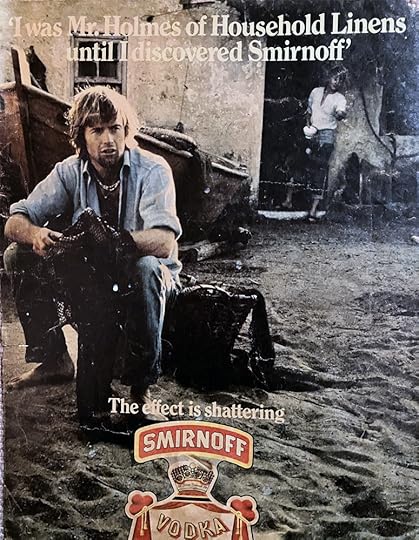

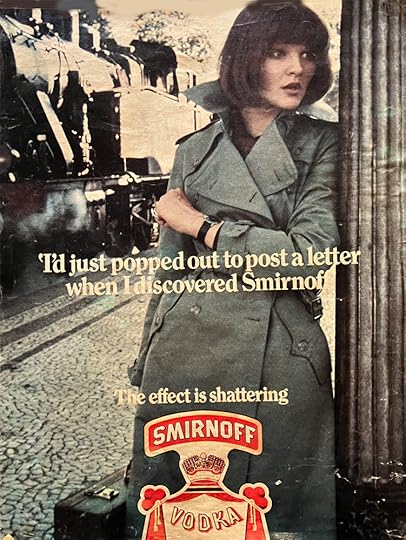

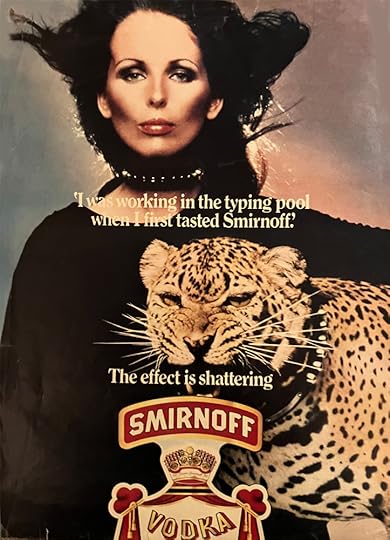

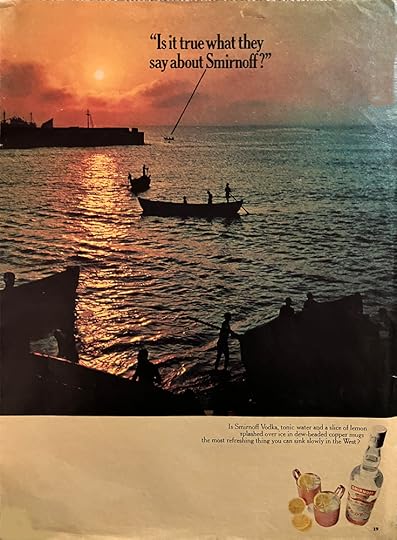

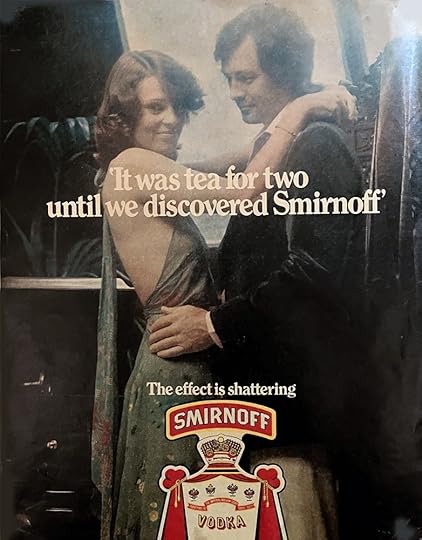

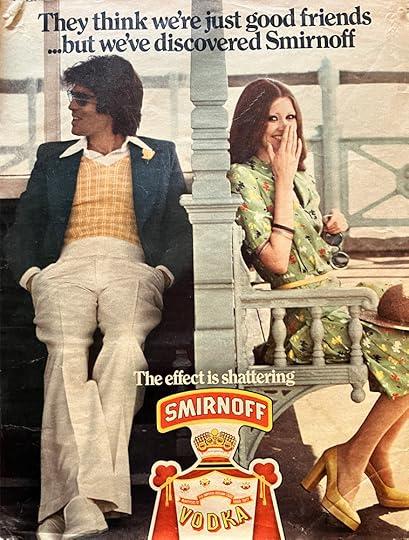

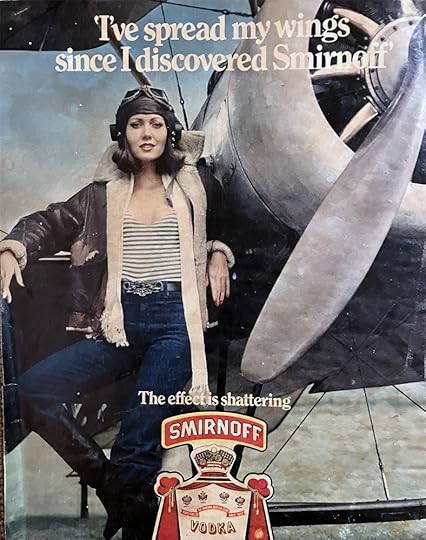

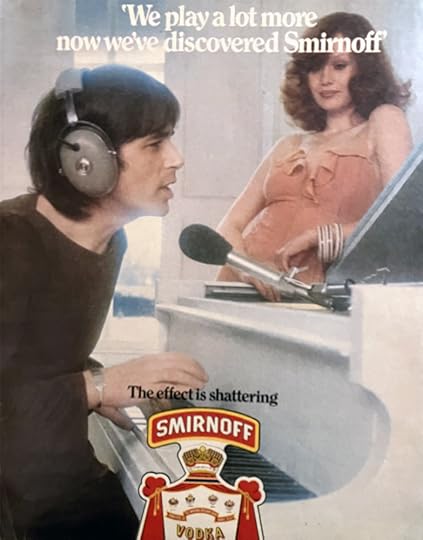

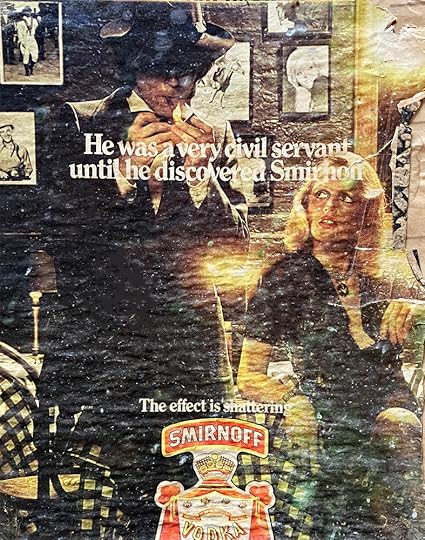

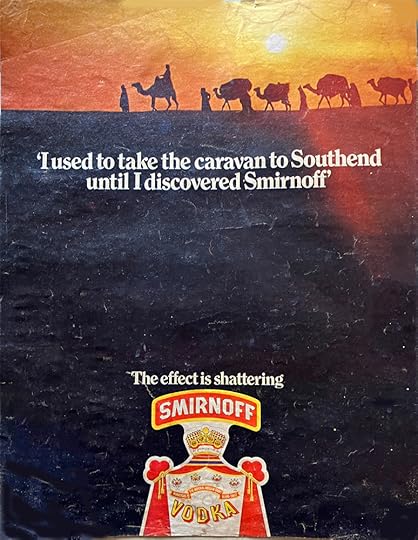

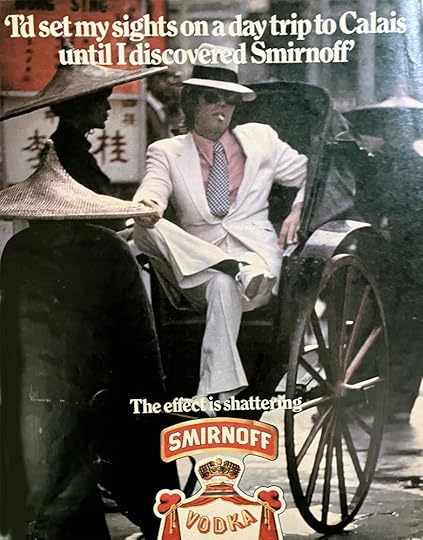

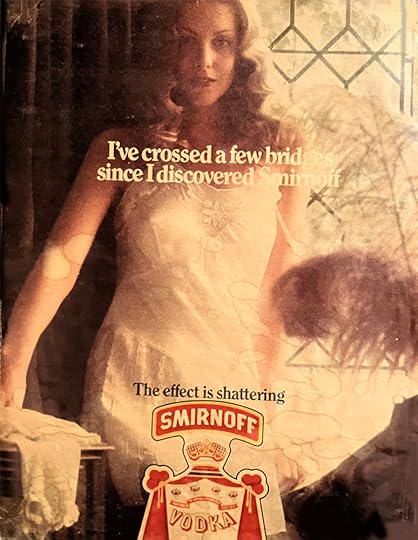

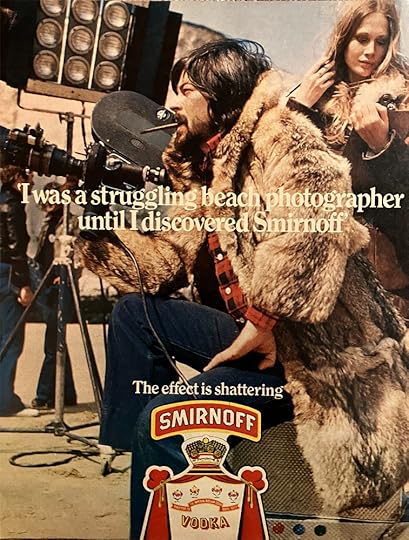

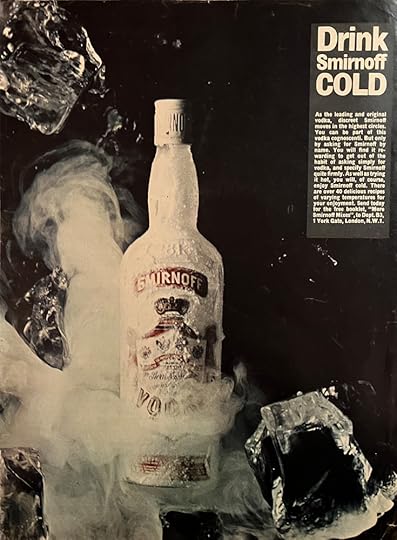

As a student in the mid-1970s I probably drank more vodka than was necessarily good for me. It was part of my fascination with all things Russian. It was also just at the time when Smirnoff launched its striking advertising campaign (by Young & Rubican), with images such as the one above alongside various plays on phrases such as “Well they said anything could happen” and “The effect is shattering”. In small print, as in the bottom right corner of the above image, there was also sometime written “Remember whatever happens don’t overdo it”. The images were often controversial or slightly risqué, and with later restrictions on alcohol advertising would mostly be unacceptable today, but they did capture a moment in our cultural lives. I remember using small amounts of blu tac in the corners to stick several of them on the walls of my rooms, along with large posters by Alphonse Mucha. The two went together well.

Going through countless boxes and files as I cleared out my mother’s house recently, I rediscovered some 20 of these adverts in various states of survival and decay, and thought that others might be interested in this snapshot of what was then acceptable in advertising. The campaign subsequently received a fair amount of criticism, especially from feminist writers, but at the same time it has also widely been seen as being among the best advertising campaigns of the last 50 years. I post the selection below as a cultural snapshot frrom the mid-1970s and a reminder of but one element of student life 50 years ago. One day I might get round to writing a serious article based on the large number of similar advertisements for wine that I have collected through the ages!

September 19, 2023

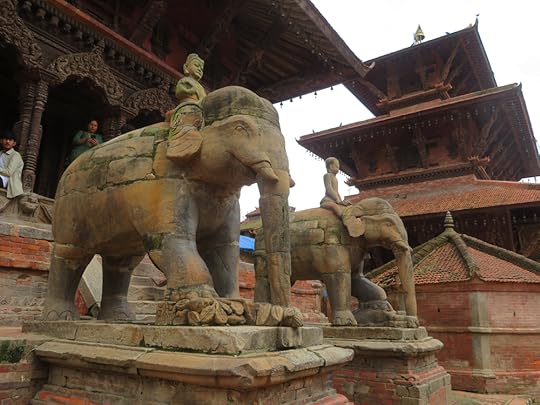

Impressions of Kathmandu and Patan Durbar Squares

A recent work visit to Kathmandu in July 2023 provided brief opportunities to visit the old Durbar (Royal) Squares in Kathmandu and Patan. Both had suffered serious damage in the 2015 earthquakes, which killed nearly 9,000 people and injured a further 22,000, with some 750,000 houses being damaged or destroyed. While much restoration work still remains to be done throughout the country, it is impressive to witness the extent of the restoration of these important historical monuments and museums. We were so grateful to Nayan Pokhrel for taking us to places we would never have found without him, and for unravelling the complex layers of cultural history that lay behind their original construction. I hope that the images below convey something of the beauty and splendour of these wonderful places and their surrounding streets.

Kathmandu Durbar SquareUnder the dark clouds of the monsoon rains…

Patan Durbar Square

Patan Durbar Square

September 5, 2023

Digital learning and measuring impact: challenges and opportunities

It was a very real pleasure to have been invited by The Digital School to speak today on monitoring and evaluation of the use of digital tech in learning at UNESCO’s Digital Learning Week held in Paris.

Should anyone be interested, my presentation is available here (without transitions). In summary,

I had a simple aim: to persuade the audience that we still need to do much more to embed quality monitoring, evaluation, research and learning when using digital tech in educationDrawing on UNESCO’s recent Global Education Monitoring Report (thanks Manos)I explored why, after decades of implementation, we are still unsure about the impacts and outcomes of “digital learning”?I suggested that we need to shift our focus away from measuring technological inputs to concentrate much more on learning outcomes.The presentation then explored three of the main reasons why so many digital tech in learning initiatives have not undertaken effective monitoring and evaluation:Insufficient rigorous baseline studies focusing on learning outcomesInsufficiently detailed financial modelsEssential for value for money measuresAn approach that does not compare “like with like”In moving towards a conclusion I also briefly touched on two other issues:The “me syndrome”, andThe environmental impact of digital techTo close, I highlighted the adverse impacts that are likely to ensue if we don’t pay enough attention to rigorous monitoring and evaluation.

I am very grateful to all those who took the time to engage with me afterwards and help build the conversation that we all need to have to make a difference in the lives of the poorest and most marginalised. Do ciick on the links below for a copy of my presentation.

Click on this link to access the above presentation in .pdf format.

June 27, 2023

I piani di Castelluccio

I have always wanted to visit the high plateaus in the Apennine mountains of central Italy in late May and early June to witness the efflorescence of colour as the spring flowers burst into bloom. This year provided a wonderful opportunity to do just that. The tiny village of Castelluccio lies on a hill in the midst of these plains, at an altitude of 1452 m, some 28 kms north of Norcia, and at the centre of the Monti Sibillini National Park. Driving towards it from Visso to the North through the Province of Marche one first encounters the little Pian Perduto (literally, the lost plain). At a distance the flowers do not at first seem particularly impressive, but the closer one gets the more beautiful they appear, with multiple combinations of reds, blues, whites and yellows, as the images below hopefully illustrate:

Crossing the border into Umbria one winds up the hill towards Castelluccio and its numerous tourists bursting out of minibuses to sample the many pop-up food stalls. Driving onwards, it is possible to take the little tracks across the Pian Grande (Great Plain) beneath Monte Vettore, past the shepherds still pasturing their sheep, and into the numerous fields sown with a multiplicity of different crops and flowers.

It is an amazing sight, quite unlike anything that I have experienced before. Walking along the field edges the sweet scents of the flowers and the buzzing of countless insects reminds one of the significance and power of the natural world – the real world – something that will never fully be replaced by digital tech. It is so beautiful and so uplifting.

Looking more closely, though, it is also possible to see the white scar across the upper slopes of Monte Vettore (left image below), a reminder of the devastating forces of nature experienced in earthquakes. This is but one expression of the massive 2016 earthquakes that killed some 300 people and devastated nearby Norcia, largely destroying its monuments and churches (below right), especially the basilica of San Benedetto (patron saint of Europe). It will sadly be many years before these buildings are safely restored.

I very much hope that one day I will return to the restored churches of Norcia, and once again experience the wonder of i piani di Castelluccio.

June 2, 2023

Power hierarchies and digital oppression: towards a revolutionary practice of human freedom

I recently spent three hours completing an online financial expenses claim form for the finance department of our university relating to an overseas research trip. There were only 20 items of expenditure to be entered. However, each of the receipts had to be copied, reduced in size to suit the requirements of the software and uploaded into the system, along with separate details of the credit card payments for them. These had to be matched with numbered explanatory entries on another page of the online form, none of which could be automatically generated, and each of which required separate keyboard entry. On average, it therefore took me nine minutes per entry. I’m sure that anyone who has been forced to use Unit4’s Agresso software will know just what a cumbersome and time-consuming piece of software this is. Of course, it purports to reduce the time spent by staff in the accounts department, thus reducing the university’s expenditure on staffing, but this is at a significant cost in terms of the amount of time that I, as a user, have to spend. In the past, using hard copy receipts and forms, this task would have taken me much less than an hour to complete. My time is precious, and this represents a significant waste of time and money for myself and the university, over and above the costs that the university has incurred in purchasing the software and training staff in its use.

This is but one example of the ways in which digital tech is being designed and used to shift the expenditure of labour from the top downwards, and from the centre to the periphery (see my 2020 post on this for more examples). End users now have to do the work that those at the centre of networks (such as organisations, institutions, or governments) previously had to do; end users produce and upload the data that the centre formerly collected and processed. This is one of the main reasons why workers and citizens are now forced to spend considerably longer time and more effort completing mundane tasks, for the benefit of more powerful centres (and people) who give them no choice, and force them to conform to the digital systems that they control.

Examples of everyday digital oppression

Examples of everyday digital oppressionThere are many examples of this tendency, but the following currently seem to be most problematic (over and above the ever present challenge of spam, hacking and online fraud; I do not, though, address issues such as digital violence and sexual harassment here because I have written about them elsewhere, and want in this piece to focus instead on the everyday, normal processes through which structural imbalances are designed and enforced in the everyday use of digital tech):

The (ab)use of e-mails, especially when disseminated by the centre to groups of people. It is easy to send e-mails from the centre to many people at the periphery or down the hierarchy, but the total burden of time and effort for all the recipients can be enormous. This is particularly with respect to copy correspondence, which adds considerably to the burden (see my e-mail reflections written in 2010 but still valid!). It is increasingly difficult for many people to do any constructive work, because they are inundated with e-mails. Being forced to download attachments and print them off for meetings. Some people “at the centre” still require those attending meetings to print off hard copies of documents before attending. This is quite ridiculous, since it vastly increases the total amount of time and effort involved. If hard copy materials are required, these should always be produced and distributed by the centre and not the end user.Extending the working day through access to and use of digital tech. The above two observations are examples of the general principle that digital tech has been used very widely to extend the working day, without paying staff for this increase. The idea that e-mails can be answered at home after “work”, or personal training done in “spare time”, are but two ways through which this additional expropriation of surplus value is achieved.Companies requiring users to complete online forms and upload information. This widespread practice is one of the most common ways through which companies reduce their own labour costs and increase the burden on those for whom they are intended to be providing services. Creating online accounts, logging on with passwords, and then filling in online forms has become increasingly onerous for users, especially when the forms and systems are problematic or don’t have options for what the consumer wants to enquire about. Such systems also take little consideration of the needs of people with disabilities or ageing with dementia who often have very great difficulty in interacting with the technology.Users having to download information, rather than receiving it automatically at their convenience. Centres, be they companies or organisations, now almost universally require users to log on to their systems and go through complex, time-consuming protocols to gain access to the information that centres wish to disseminate (banks, financial organisations, and utility companies are notorious for this). In the past, such material was delivered to users’ letter boxes and could simply be accessed by opening an envelope. Again, this is to the benefit of the centres rather than the users.Useless Chatbots, FAQs, online Help options and voice options on phone calls. Numerous organisations require consumers/users to go through digital systems that are quite simply not fit for purpose and often take a very considerable amount of users’ time (and indeed costs of connectivity). While some systems do provide basic information reasonably well, the majority do not, and require users to spend ages trying to find out relevant information. Many organisations also now make it very difficult for users to find alternative ways of communicating with them, such as by telephone. Even when one can get through to a telephone number and negotiate the lengthy and confusing numerical or voice recognition options, it frequently takes an extremely long time (often well over 30 minutes, or a 16th of the working day) before it is possible to speak with someone. Sadly, human responders once contacted are also often poorly trained and frequently cannot give accurate answers.Having to use yet another digital system chosen by centres and leaders to exploit you in their own interests. There are now so many different online cloud systems for communicating with each other at work (or play), such as Microsoft’s Teams, Google’s Workspace, Slack, Trello, Asana, and Basecamp (to name but a few). None of us can expect to be adept at using all of them. However, leaders of organisations and teams generally impose their own preferred software solution (or those ordained by their organisation) on members. Rarely are they willing to change their own preferences to suit those of other team members. Hence, this reinforces power relationships and those lower down the food chain are forced to comply with solutions that may well not suit them.Filling in forms online that are badly designed, crash on you, and often don’t have a save function for partially completed material. I am finding this to be an increasingly common and very frustrating form of hidden abuse. The number of times I have had to fill in forms online that take far longer than just writing a document or sending an e-mail is becoming ever greater. This is particularly galling when the software freezes or the save function does not work, and everything gets lost, forcing me to start all over again. The hours I have lost in this way (particularly in completing documents for UN agencies) are innumerable.Time wasted in having to scroll through quantities of inane social media to find a message that someone has sent you and is complaining that you have not yet responded to it. The answer to this is simply not to use social media, and especially groups (see my practices), or to “unfriend” people who do this, but increasingly this is yet another means through which centres seek to control and exploit those at the peripheries or lower down the work hierarchy.Centres simply failing to respond to digital correspondence, especially with complaints, and forcing users to keep chasing them online. I have lost count of the number of times I have had to fill in an online form, usually about something I have been asked to do by a company or agency, or concerning an appointment or complaint, only for them never to reply. This forces me to waste yet further time trying to contact them about why they haven’t responded!This list of examples could be added to at great length, and mainly reflects my own current angst (for earlier examples see On managerial control and the tyranny of digital technologies). To be sure, not all digital systems are as appalling as the above would suggest, and credit should be given where due. The UK’s digital service, https://gov.uk is generally a notable positive exception to this generalisation, and I was, for example, very impressed when I recently had to use it to renew a passport. However, to change this situation it is necessary to understand its causes, the most important of which are discussed below.

The rise of digital capitalism and the causes of digital oppression

The rise of digital capitalism and the causes of digital oppression Five main causes lie at the heart of the above challenges. Underlying them all, though, is the notion that it is right and proper for companies to seek to expand their markets and lower their costs of production in the pursuit of growth. Capital accumulation is one of the defining (and problematic) characteristics of all forms of the capitalist mode of production, and new digital technologies have two key attributes in supporting this process: first, the use of digital tech very rapidly accelerates all forms of human interaction; and second, their use can replace much human labour (thus increasing the human labour productivity of those remaining in employment) . On the assumption that the cost of introducing digital tech is cheaper than the cost of human labour, then digital tech can be used dramatically to increase the rates of capital accumulation and surplus profit acquisition by the owners of the means of production. However, if there is insufficient demand in the market, not least because of falling purchasing power as a result of reduced levels of human labour, then the twin crises of realisation and accumulation will inevitably ultimately cause fundamental problems for the system as a whole. It must also be realised that (as yet) digital tech does not actually have any power of its own. The power lies with those who conceive, design, construct and market these technologies in their own interests. As the apparent AI ethical crisis at the moment clearly indicates, the scientists who support this process are as much to blame for its faults as are the owners of capital who pay them. Five aspects of this underlying principle can be seen at work in leading to the current situation whereby those at the system peripheries or the bottom of hierarchies are being increasingly oppressed through the uses of digital tech (as described in the examples above):

First, labour costs have generally long been perceived as being the critical cost factor in many industrial and commercial sectors. The digital tech sector has therefore been very adept at persuading other companies and organisations to do away with human labour and replace it with technology in the productive process. The labour that is left must be forced to work longer hours while also increasing its productivity. However, companies and organisations have also been persuaded that they can make further significant cost savings by ensuring that consumers and staff lower down the hierarchy do much of the work for themselves by, for example, filling in online forms and using chatbots as discussed above. Digital tech is used to shift the balance of time spent on tasks to the consumers or users. This insidious shift of emphasis is a classic expression of the digital oppression that is now increasing being felt by people across the world.A second significant feature of capitalist enterprises is their need to create as uniform a market as possible so that they are then able sell as many of the same products or services as they can. This emphasis on uniformity requires users to adjust their previously diverse human behaviours to conform to the uniform digital systems that are imposed on them. It lowers overall costs, and enables markets rapidly to be expanded. We experience this every time we have to choose which of a number of options we are given on a phone call, or fill in an online form, where what we are concerned about does not easily fit in to any of the options we are given. Similarly, we encounter it every time someone wanting us to do something requires us to use their software package or app rather than our preferred one. Again, we encounter a different form of digital oppression.Third, the increasing emphasis and reliance on digital systems means that the human labour remaining in organisations and companies becomes increasingly overstretched. Without adding to the amount of time that they work, staff having to use digital systems through which they are constantly bombarded with requests and actions become ever more oppressed. Furthermore, the difficulty of finding qualified and knowledgeable staff competent enough to give a good service to clients and customers, means that organisations are increasingly not capable of responding satisfactorily to those who don’t fit into the uniform-demanding digital systems that they now operate. This is why some companies make it as difficult as possible for clients and customers actually to speak with a human being among their staff, and why the quality of service they provide can be so bad. Some turn to call centres overseas, which often provide a dire service on poor quality phone lines staffed by people who cannot competently speak or understand the language of the customers.Fourth, much of the software and systems that governments, organisations and companies are persuaded to buy by the tech sector is poorly designed, poorly constructed and poorly implemented. As but one example, in 2015 the abandoned NHS patient record system in the UK had “so far cost the taxpayer nearly £10bn, with the final bill for what would have been the world’s largest civilian computer system likely to be several hundreds of millions of pounds higher, according a highly critical report from parliament’s public spending watchdog” ( The Guardian , 2015). The quality of design and programming in many apps, especially when outsourced to countries with very different cultures of coding, is often very low, and it is unsurprising that the functionality of many digital systems is so dire. Despite much rhetoric about human-computer interaction and user-centred design, the reality is that much tech is still built by people with little real knowledge and expertise in what users really want and how best to make it happen. All too often, they are themselves brought up within the culture of uniformity that limits real quality innovation.Finally, the scientism (science’s belief in itself) that has come to dominate the tech sector and its role in human societies has largely served the interests of the rich and powerful, not least through the hope that aspirant digital scientists have to join that elite themselves. Ultimately, this serves the interests of the few rather than the many. Those on the peripheries or at the lower end of hierarchies have instead become increasingly oppressed and enslaved as a result of the propagation of digital tech across all aspects of human life (see my Freedom, enslavement and the digital barons: a thought experiment). It is becoming ever more crucial to challenge scientism, and counter the belief that science in general, and digital tech in particular, has the ability to solve all of the world’s problems. What’s to be done

What’s to be doneNone of these challenges and none of the reasons underlying them need to be as they are. There is nothing sacrosanct or inevitable about the design, creation and use of digital tech. We do not need it to be as it is. It is only so because of the interests of the scientists who make it and the owners of the companies who pay them to do so.

There are numerous ways through which we can challenge the increasingly dominant hegemony of the digital tech sector in human society at both an individual and an institutional level. I concentrate here on suggestions for individual actions that can help us regain our humanity, leaving the discussion of the important regulatory transformations that are essential at a structural level for a future post. After all, it is only as individuals in our daily actions that we can ever regain any real power over the structures that oppress our “selves”. Any actions that can help change the underlying structures and practices giving rise to the oppressions exemplified at the start of this post are of value, and they will vary according to our individual space-time conjuctures. I offer the following as an initial step to what might be termed a revolutionary practice of digital freedom:

Create multiple identities for ourselves. As individuals we are much more complex than the uniformity that digital systems wish to impose on us. We are so much more than a single digital identity. Hence, we must do all we can to create multiple identities for ourselves as individuals, and resist in every way possible attempts to control and surveil us through the imposition of such things as single digital identities.We must resist being forced to use specific digital technologies. We should always refuse to use digital tech when we can do something perfectly well without it. We must likewise very strongly resist attempts by companies, governments and organisations to force us to use a single piece of tech (hardware or software) to do something, and always demand that they provide a solution through our individually preferred technologies. At a banal level, for example, if you are happy with using Zoom and Apple’s Keynote, Mail, Numbers and Pages, you should never be forced by anyone to use Microsoft Teams or Google Workspace. If people or organisations are not willing to adapt to your individual needs they are probably not worth working with (or for) anyway. Many societies now require restaurants to provide details of all possible food preferences and allergies, so why should we accept being oppressed by digital tech companies who only wish us to conform to one uniform system?We should never accept poor quality digital systems. If you cannot do something you want to through an organisation’s digital systems, then it is always worth complaining about it. Writing a letter of complaint, copied widely to relevant ombudsmen, is not only quicker than trying to use poor quality tech systems, but numerous complaints can cumulatively help to change organisations.We must always challenge scientism, and emphasise the importance of the humanities in answering the questions that scientists cannot answer. Our particular structure of science primarily serves the interests of scientists, who work in very particular ways. This model of science is overwhelming dominant in the way in which digital tech is created. Although scientists can produce impressive results, they are not the guardians of all knowledge, and they are by no means always right. Almost every theory that has ever been constructed, for example, has at some later time been disproved. We must therefore resist all efforts to make science (or STEM subjects) dominant in our education systems. We must cherish the arts and humanities as being just as valuable for the future health of the societies of which we are parts.We should identify and challenge the interests underlying a particular digital development. All too often innovations in digital tech are seen as being inevitable and natural. This is quite simply not the case. All developments of new technology serve particular interests, almost always of the rich and powerful. To create a fairer and more equal society this must change. The scientists who have developed generative AI, for example, are completely responsible for its implications, and it is ridiculous that they should now be saying that it has gone too far and should somehow be controlled. They did not have to create it as it is in the first place.We need to implement our own digital systems to manage emails and social media. It is perfectly possible to reduce the amount of digital bombardment that we receive, but we need to manage this consciously and practically (see my Reflections on e-mails). Simple ways to start doing this are: file all copy correspondence separately; always remove yourself from mailing lists unless you really want to receive messages (you can always rejoin later); limit your participation in social media (especially WhatsApp) group; and keep a record of the time you spend each day doing digital tasks (it will amaze you) and think of how you could use this time more productively!Take time offline/offgrid to regain our humanity. It is perfectly possible still to live life offline and offgrid. Many of the world’s poorest people have always done so. The more we are offline, the more we realise that we do not need always to be connected digitally. Some time ago I created the hashtag #1in7offline, to encourage us to spend a day a week offline, or, if we cannot do that, an hour every seven hours offline. Not only does this reduce our electricity consumption (and is thus better for the physical environment), but it also gives us time to regain our experience of nature, thereby regaining our humanity. The physical world is still much better than the virtual world, despite the huge amount of pressure from digital tech companies for us to believe otherwise. Remember that if we don’t use physical objects such as banknotes and coins, or physical letters and postcards, we will lose them. Think, for example, of the implications of this, not least in terms of the loss of the physical beauty of the graphics and design on banknotes or stamps, key expressions of our varying national identities (not again that digital leads to bland uniformity). Remember too that every digital transaction that we make provides companies and governments with information about us that they then use to generate further profit or to surveil us ever more precisely. Being offline and offgrid is being truly revolutionary.

May 17, 2023

An environmentally harmful alliance of growth mantras

This post argues that a coalition of interests around economic and demographic growth has not only created significant inequalities across the world, but has also been the main factor driving global environmental degradation. It is demographic growth in combination with a particular form of tech-led capitalist economic growth that has been the main driver of global environmental change, of which climate change is but a small part.

Economic GrowthEconomic growth has for many decades been seen by economists and international organisations alike as the key means through which poverty can be eliminated, especially in the economically poorer countries of the world. This powerful mantra lay at the heart of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs, 2000-2015) and has more recently been central to aspirations for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, 2015-2030). Yet, as I have frequently argued elsewhere,[i] these aspirations have never been achieved, they focus on absolute poverty rather than relative poverty, and the resultant unfettered economic growth has almost always been associated with an increase in inequalities. For those concerned with equity and who define “development” primarily as the reduction of inequalities, policies designed to increase growth alone are doomed to failure and need to be replaced.

National policies and international frameworks focused on growth primarily support the interests of those private sector companies and global corporations that have worked so assiduously to shape the UN rhetoric around economic growth and innovation. Digital tech companies have long been at the forefront of this, not only driving growth, but also reaping the benefits of so doing.[ii] Economic growth is deemed to be essential both to expand markets and also to increase labour productivity, whereby owners of the means of production can extract surplus value.

In trying to consider alternative models of socio-economic activity, I have often used the notion a “no-growth” economy as a heuristic device, encouraging audiences to consider how economic activity might be organised if growth was somehow prohibited. Although there are many potential outcomes, one of the most interesting is the thought that the pressures to achieve a reduction in inequalities might increase under such conditions, thus leading to a fairer and more equitable society. I have also found the work of the Post-Autistic Economics Network to be a helpful source of inspiration, challenging as it does many of the usually taken for granted assumptions of neo-classical (and indeed neo-liberal) economics.[iii]

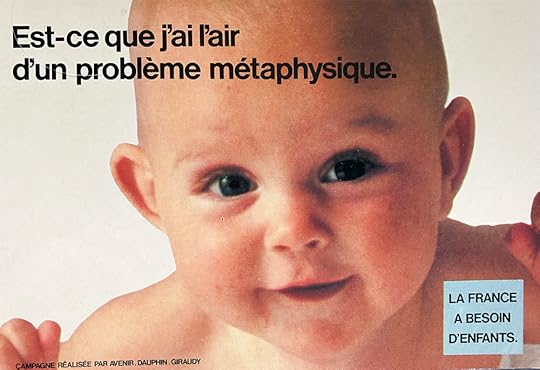

Demographic growthRecent debates about the balance between the positive and negative impacts of demographic growth on the economy have highlighted their inextricable intertwining with the rhetorics of economic growth.[iv] On the one hand there are those who argue that ageing populations with few young and economically productive people are deeply problematic for economic growth, and that policies to encourage higher birth rates or immigration are essential to enable economic viability. Years ago, I thus well remember the French advertising campaign to encourage families to have more children, beautifully encapsulated in this postcard:

On the other, are those who point to a demographic dividend in Africa, through which increasing numbers of young people are going to drive the economy forward, fuelled especially by the potential of digital tech. See for example, this image below from Invest Africa in an article entitled How can Africa harness its demographic dividend (and note its emphasis on digital tech).

Both arguments are deeply problematic. In the African case, this naïve dream is only going to be possible if young people are well educated and jobs are available for them; it seems more likely that this will actually be a demographic millstone rather than a dividend. The “problem” of an ageing population likewise only becomes serious if systems are put in place to extend human life at high cost for long periods of time, or if labour productivity stagnates or declines.[v]

Much of the international debate concerning demographic change has been articulated around its interconnectedness with economic growth. Put simply, the interests underlying the continued drive for economic growth are frequently the same as those that advocate for population increase as being positive and that technology can continue to ensure a healthy lifestyle for a very much larger human population. Rather less interest has surprisingly been devoted to what human experiences of such changes might be. This is especially so when the twin mantras of economic growth and demographic growth are confronted by their combined impact on the environment. This is particularly evident in the reactions over the last 50 years to The Club of Rome’s 1972 report on Limits to Growth,[vi] and to the much more recent and controversial film Planet of the Humans, produced by Michael Moore in 2019.

Limits to Growth, Planet of the Humans and the legacy of Thomas MalthusIn 1972, the Club of Rome published its prescient report entitled Limits to Growth, which argued that if the then growth trends in population, industrialisation, resource use and pollution continued unchecked, then the carrying capacity of the earth would be reached some time within the following century.[vii] I remember distinctly the wake-up call that this provided for me as an undergraduate, and thinking back to those days have been fascinated by how its message seemed increasingly to be ignored in the ensuing decades. Few countries apart from China (see below) really responded to this message, although some such as India made tentative efforts to address it. I distinctly remember, for example, being in Sonua market in what was then South Bihar (now Jharkhand) in 1976 and seeing this painted slogan of two parents and two children that formed part of the government’s 20 point programme during the 21 month state of emergency declared by Indira Gandhi.

India’s population was then 637.45 million; in 2023 it is 1,428.63 million. The policy was not a success.

Interestingly, 30 years after the Club of Rome report, the authors published an update, in which they concluded that “it is a sad fact that humanity has largely squandered the past 30 years in futile debates and well intentioned, but halfhearted, responses to the global ecological challenge”. This is an overly generous observation, largely because of the very specific interests that have underlain economic and demographic change in subsequent years. In essence, as noted above, the owners of the world’s major companies, supported by many economists have argued convincingly that both economic and demographic growth are essential for the future success of humanity, that the new SDGs are indeed sustainable,[viii] and that technology can continue to provide innovative solutions to the increasing problems caused by the pressure of people on the planet. I find it extraordinary to think that in my lifetime the world’s population has risen by 288% from 2.77 billion people to 8 billion people. What I find more frightening, though, is that there is nothing in the UN’s development goals really about population growth,[ix] and there was almost universal condemnation in the world’s capitalist countries when China adopted its 1 child per family policy when it was introduced in 1980.[x] Widespread criticism of the Club of Rome’s report and others who held their views was based primarily on the grounds that they were neo-Malthusian,[xi] and that the world was coping perfectly well, in large part through technological advances that were overcoming the challenges of an increasing population. Indeed, the observation that very much higher levels of population have been able to live on the planet over the last 50 years would seem to support such a view. However, this fails to recognise that very many of those people live in abject poverty and misery, and that the environmental impact of such growth has been very significant indeed. Unfortunately, much of the focus of the international community has been captured by the rhetoric around climate change, which has served to reduce emphasis on the wider environmental impact caused by the double mantra of economic and demographic growth. Climate change causes nothing; it is the factors giving rise to changes in the climate that are the ultimate cause and the real problem that needs addressing.

These issues were brought to the fore by the film Planet of the Humans produced by Michael Moore, and directed by Jeff Gibbs in 2019. This has been very widely criticised by those within the so-called environmental and green lobbies on the grounds that it was outdated and misleading, especially concerning the scientific evidence and more recent developments in renewable energy. However, many of these criticisms miss the fundamental point of the film, which was that our economic system, based on the present model of capitalist growth is fundamentally unsustainable, particularly in the context of continued demographic growth.[xii]

Many of these arguments might appear to smack of neo-Malthusianism which has been almost universally condemned from a wide range of angles, as were the criticisms of Malthus’ original works.[xiii] Engels, writing in 1844,[xiv] put it this way: technological and scientific “progress is as unlimited and at least as rapid as that of population”. Many continue to agree with Engels’ proposition, or at least hope that he was right. However, the scale of human impact on the environment today is vastly different from when Malthus first wrote his Essay on the Principle of Population at the end of the 18th century, and the world’s population is now more than twice as much as it was when Limits to Growth was first published. People are seriously talking about and investing in the colonisation of outer space to provide continued sustenance for the world; technology once again to the fore. My emphasis in this piece, though, is not so much to take issue with the many diverse arguments of those who challenge neo-Malthusianism, but rather, and much more simply, to suggest that the dominant global focus on climate alone is hugely damaging because it fails to address the wider environmental impacts of our thirst for growth.

Environmental implications“Climate change” has become a popular focus of concern and political protest, but as I have argued extensively elsewhere[xv] it is a deeply problematic notion conceptually, especially when abbreviated to just these two words “climate” and “change”, ignoring the words “human” and “induced”. All too often, it is used in a way that externalises it as being somehow separate from the human actions that cause weather patterns to change, while at the same time also implying that humans can somehow solve it without addressing the deeper structural problems facing the world. Likewise, all too frequently, the answer to the problem of “climate change” is naïvely deemed to be an over-simplified reduction in carbon emissions. Leaders of the digital tech sector, with their voracious appetite for growth and innovation are eager to comply with this agenda, while failing almost completely to recognise the enormous harms that they are causing to other aspects of the environment. By focusing largely on “climate change” they can feel good whilst also maintaining their life blood of economic and demographic growth that drives their creation of profit.

This is most definitely not to suggest that changes in temperature, rainfall, and wind patterns are unimportant; very far from it. But it is to argue that these are caused fundamentally by the twin mantras of economic and demographic growth that have increasingly dominated the world over the last century, rather than by some exogenous notion of climate change. More worryingly, these mantras have been fuelled still further by the unachievable and unsustainable Sustainable Development Goals that have become part of the problem rather than a solution. Contrary to much popular rhetoric, the very dramatic increases in global carbon emissions do not appear to have begun until the beginning of the 20th century, and coincide very closely with increases in world population.[xvi] Put another way, had global population not increased as dramatically as it has done over the last century, then those living here would not have been faced with the impending crisis that we now urgently need to address.

Moreover, and I would suggest more importantly, the emphasis on “climate change” has largely distracted attention from the crucial effort that must be placed on the wider environmental impacts of economic-demographic growth. Climate is but a small part of the physical environment, which includes the lithosphere, biosphere and hydrosphere, alongside the atmosphere. By focusing so heavily on climate, and ways that digital tech can be used to reduce carbon emissions, activists, academics, politicians, business leaders, civil society organisations and citizens alike are missing the bigger picture. The design and use of digital tech is causing significant environmental harms that tend to be ignored in the search for a solution to climate change.[xvii]

In conclusion: a new beginningThis post has contributed to my previous body of work by articulating five main inter-related propositions:

There has been a coalition of interests between those advocating economic and demographic growth, largely reflecting the determinant structures of contemporary global capitalism.[xviii]This is archetypically reflected in the power of the digital tech sector, which has permeated the UN system.[xix]The dramatic impact of the digital tech sector on the wider physical environment has been largely hidden by an overwhelming global emphasis on climate change, and ways through which digital tech can reduce carbon emissions.It is important to understand climate change as a result and not a cause, and therefore focus on doing something about the real causes of climate change (the economic-demographic growth mantra) rather than primarily addressing carbon emissions.It is essential to understand changes to the climate as but a part of the much wider negative environmental impacts of the coalition of interests underlying the economic-demographic growth mantra.

Are we facing a new era of increasing mass-migration, famine, disease and warfare? Is the economic growth model that has dominated the last century going to consume itself in a falò delle vanità? Might there be less inequality and poverty in the world if there were fewer people and the wealth that was created was shared more equally? Can we imagine a beautiful physical environment that could be created out of the desolate and scourged world we are currently creating? How might digital tech be used to serve the interests of the poorest and most marginalised more than those of the rich and powerful? These questions are all inter-related, and we need to find answers to them before it is too late.

[i] Unwin, T. (2007) No end to poverty, Journal of Development Studies, 45(3), 929-953; see also my post in 2010 on Development as ‘economic growth’ or ‘poverty reduction’

[ii] For an overview of the role of the private sector in shaping UN tech policy see my Reflections on the Global Digital Compact (2023).

[iii] For a brief history, see http://www.paecon.net/HistoryPAE.html; see also Stiglitz, J.E. (2019) People, Power and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent, Allen Lane, and Stiglitz, J.E. (2002) Globalization and its discontents, New York: W.W. Norton & Company

[iv] See for example, World Economic Forum (2022) David Sinclair explains what an ageing population means for economies around the world, which includes a range of different aruments about the impact of an ageing population.

[v] Efforts by the Digital Barons (leaders of major US digital corporations) to extend human life far beyond its present span, such as those by Zuckerberg (see CNET, 2013), Larry Page (founding Calico, an Alphabet subsidiary, in 2013), Jeff Bezos (with his investment in Altos Labs, MIT Technology Review in 2021) and Larry Ellison (founder of Oracle, investing in ageing research, see Time, 2017) to name it a few are deeply worrying, both because only the rich will be able to afford such treatments, but also because they will inevitably mean an even greater population load on the planet; Elon Musk’s reported criticism of such practices (The Independent) is about the only occasion I have ever agreed with him about something!

[vi] See also The Limits to Growth+50

[vii] See also the raft of activities undertaken by the Club of Rome in 2022 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the report, https://www.clubofrome.org/ltg50/.

[viii] Which, in case it is unclear from the thrust of my argument, most of them definitely are not.

[ix] See Population Matters, Population and the Sustainable Development Goals.

[x] The policy was reversed in 2015, and its impact remains controversial; see Wang, Z. et al. (2016) Ending an Era of Population Control in China: Was the One-Child Policy Ever Needed?, American Journal of Economics and Society.

[xi] See further below on Thomas Malthus; in essence, critics of neo-Malthusianism have suggested that these arguments were overstated and premature, and that technology would enabled very much higher population levels to be sustained.

[xii] See responses at https://planetofthehumans.com/filmmakers-responses/.

[xiii] See, for example, Saigal (1973), Wu Ta-kun (1979), Burkett (1998), Kelly (2021), Shermer (2016),

[xiv] Engels, F. (1844) Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy”, Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, 1844, p. 1.

[xv] See, for example, “Climate Change” and Digital Technologies: redressing the balance of power (Part 1), Digital technologies and climate change, Part I: Climate change is not the problem; we are, Digital technologies and climate change, Part II: “Unsustainable” digital technologies cannot deliver the Sustainable Development Goals, Digital technologies and climate change, Part III: Policy implications towards a holistic appraisal of digital technology sector, Problems with the Climate Change mantra.

[xvi] See https://unwin.files.wordpress.com/2022/11/graphs-2.jpg.

[xvii] See http://desc.global which is attempting to understand the relative balance between environmental harms and benefits of digital tech.

[xviii] In essence, demographic growth has been co-opted to serve the interests of the private sector (capitalism) in seeking to overcome the tendency towards a falling rate of profit. Put simply, population must grow to provide both an expanded market and more labour to ensure economic growth.

[xix] This is taken much further in my Reflections on the Global Digital Compact (2023)

May 4, 2023

Digital and Youth: participating in World Data Forum side event in Macau

It was a great honour to be asked by a group of young Chinese interns at the United Nations University Institute in Macau to give a short keynote address at the hybrid event that they were organising from there on 30th April in partnership with The Institute for AI International Governance of Tsinghua University (I-AIIG), forming part of the World Data Forum satellite event being convened by the Institute in the city of Macau. As their introduction to the event summarised:

The younger generation are often seen as digital natives who have more exposure and access to data technology than older generations. They are also more likely to use data technology for learning, innovation, participation and empowerment. However, this also means that they face unique opportunities and challenges related to data that need to be explored and addressed.

As the satellite event of this year’s World Data Forum, this youth forum will take “Digital and Youth” as the main theme, adhere to youth leadership and youth participation, aiming to provide a platform for dialogue and exchange among different stakeholders who are interested in or affected by data and its impact on youth.

In the brief 15 minutes available, I chose to focus on three proposals:

We need new, more inclusive modes of inter-generational dialogue about digitalJust because it is possible to do something, does not mean that it is right or good to do so.Digital tech is all too often assumed to be inherently good – but we need to mitigate the harms to ensure any good can prevailWe must all consider the environmental impact of data, and digital tech more widely. Digital tech is often the cause of environmental harms rather than a solutionThe full presentation (in .pdf format is available at Data and Youth.

The event was great fun, and the organisers had brought together many leading young academics from across China working on digital tech in general, and data in particular, divided into four main sessions:

Youth Work on Digital Humanities in Empowering the Cultural LegacyDigital technology and WellnessArtificial Intelligence Cutting EdgePersonal Information Protection and Data Security Governance

Many thanks to everyone involved for making this such an interesting and enjoyable experience.

March 30, 2023

Attributing geographical causality: why I have problems with using the terms “Global South” and “Global North”

I have long been troubled by the widely accepted and increasingly used terms Global South and Global North.[i] Those who wish to use them for political purposes or to highlight the factors that they claim cause inequalities across the world will of course continue doing so, but there are at least six main reasons why I find it a misleading and problematic choice of terminology. I list these below just to help explain why I don’t uses these terms, and I hope my comments may also encourage others to do likewise.

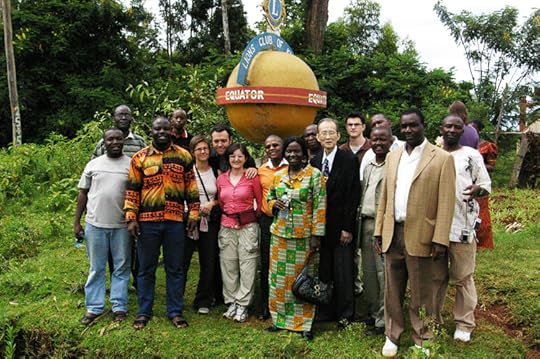

People from several different parts of the world coming together on the Equator in KenyaAbove all, the use of such terminology implies some kind of

spatial causality

, usually around the idea of the North exploiting the South in the present and/or the past. This strikes me as being surprisingly similar to the now widely discredited notion of environmental determinism, advocated by the likes of Ellsworth Huntington and Ellen Churchill Semple in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (for a wider discussion, see my

The Place of Geography

, 1992). There is not something universal about living in the North (whatever that means), or about the North itself that makes it inherently more powerful and dominant than the South.[ii]I remain confused about

why the word “Global” is at all necessary

. What does it add? In 1980, the Brandt Report entitled North-South: a Programme for Survival, managed to convey very similar meaning, but much more succinctly,[iii] and indeed also drew a much more nuanced wavy line between the two regions. To be sure, there are those who want to use the term global to represent some kind of global solidarity, especially in the South, but this is more aspirational than real (see also comments on relative usage of the terms below)In an

absolute

global sense, the geographical north is the northern hemisphere, and the south the southern hemisphere. Yet, there are problems with such usage to refer to per capita economic wealth and human well-being. It is often forgotten that the South Asian countries of Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, for example, are all in the northern hemisphere. Likewise, many more African countries are in the northern hemisphere than are in the southern.[iv] The rich countries of Australia and New Zealand are in contrast in the southern hemisphere.

There is also much economic poverty in the northern hemisphere and much richness in the southern

. If large absolute regions are being considered it is in some ways more accurate to consider the Tropics (between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn) as being economically poorer/more exploited than either of the areas to the north and the south. Such suggestions, though are dangerously close once again to falling down the slippery slope of environmental determinism.North and South can also, though, be interpreted in a

relative

sense. Given that only 10-12% of the world’s population actually lives in the Southern Hemisphere, this relative approach is certainly a more realistic one to trying to grapple with the differences between states. It is nevertheless also problematic as a framework for explaining wealth differences (or indeed most other differences).

Countries or regions further north are sometimes poorer in per capita wealth then those further south and vice versa

. Canada’s per capita income is less than that of the USA; Mozambique and Angola are poorer than South Africa. In the UK, the widely used term North-South divide actually refers to a poorer northern region and a richer southern one.I’m afraid that

the argument that I sometimes hear that the use of the terms is only an approximation and simplification and it doesn’t really matter if they are inaccurate holds no water with me

. Using such terms reinforces inaccurate understandings of cartography and geodesy, and supports looseness of meaning and language. I wonder how many people, for example consider that India is in the Global South, and thus think it is also in the southern hemisphere? Moreover, all too frequently we read or hear comments such as “The Global North generally correlates with the Western world”.[v] If that is the case, surely “Western” would be a better term to use than Northern. But we need to remember then that everywhere Western is west of some East.A significant problem is therefore that

seeking to carve the world up into binary divisions is overly simplistic and usually harmful

, for all but those who persist in using or imposing them. There are enormous differences between the continents and countries within both the so-called Global South and the Global North, and it is this rich diversity that we must cherish in multi-layered ways and understandings. Those who seek to impose an ill-fitting binary distinction generally do so in their own interests. Sometimes this is for the sake of simplicity, but as the above brief comments highlight such simplicity can be very misleading. At other times it has just become a lazy shorthand. As that well known “source of all knowledge” tells us “The Global South is a term generally used to identify countries in the regions of Latin America, Africa, Asia and Oceania”.[vi] Well, why not instead just use the actual geographical names Latin America, Africa, Asia and Oceania? This source goes on to comment that “Most of humanity resides in the Global South”.[vii] It is interesting to ponder what this actually means. As noted above this is certainly not true if South here is referring to the Southern Hemisphere.

People from several different parts of the world coming together on the Equator in KenyaAbove all, the use of such terminology implies some kind of

spatial causality

, usually around the idea of the North exploiting the South in the present and/or the past. This strikes me as being surprisingly similar to the now widely discredited notion of environmental determinism, advocated by the likes of Ellsworth Huntington and Ellen Churchill Semple in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (for a wider discussion, see my

The Place of Geography

, 1992). There is not something universal about living in the North (whatever that means), or about the North itself that makes it inherently more powerful and dominant than the South.[ii]I remain confused about

why the word “Global” is at all necessary

. What does it add? In 1980, the Brandt Report entitled North-South: a Programme for Survival, managed to convey very similar meaning, but much more succinctly,[iii] and indeed also drew a much more nuanced wavy line between the two regions. To be sure, there are those who want to use the term global to represent some kind of global solidarity, especially in the South, but this is more aspirational than real (see also comments on relative usage of the terms below)In an

absolute

global sense, the geographical north is the northern hemisphere, and the south the southern hemisphere. Yet, there are problems with such usage to refer to per capita economic wealth and human well-being. It is often forgotten that the South Asian countries of Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, for example, are all in the northern hemisphere. Likewise, many more African countries are in the northern hemisphere than are in the southern.[iv] The rich countries of Australia and New Zealand are in contrast in the southern hemisphere.

There is also much economic poverty in the northern hemisphere and much richness in the southern

. If large absolute regions are being considered it is in some ways more accurate to consider the Tropics (between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn) as being economically poorer/more exploited than either of the areas to the north and the south. Such suggestions, though are dangerously close once again to falling down the slippery slope of environmental determinism.North and South can also, though, be interpreted in a

relative

sense. Given that only 10-12% of the world’s population actually lives in the Southern Hemisphere, this relative approach is certainly a more realistic one to trying to grapple with the differences between states. It is nevertheless also problematic as a framework for explaining wealth differences (or indeed most other differences).

Countries or regions further north are sometimes poorer in per capita wealth then those further south and vice versa

. Canada’s per capita income is less than that of the USA; Mozambique and Angola are poorer than South Africa. In the UK, the widely used term North-South divide actually refers to a poorer northern region and a richer southern one.I’m afraid that

the argument that I sometimes hear that the use of the terms is only an approximation and simplification and it doesn’t really matter if they are inaccurate holds no water with me

. Using such terms reinforces inaccurate understandings of cartography and geodesy, and supports looseness of meaning and language. I wonder how many people, for example consider that India is in the Global South, and thus think it is also in the southern hemisphere? Moreover, all too frequently we read or hear comments such as “The Global North generally correlates with the Western world”.[v] If that is the case, surely “Western” would be a better term to use than Northern. But we need to remember then that everywhere Western is west of some East.A significant problem is therefore that

seeking to carve the world up into binary divisions is overly simplistic and usually harmful

, for all but those who persist in using or imposing them. There are enormous differences between the continents and countries within both the so-called Global South and the Global North, and it is this rich diversity that we must cherish in multi-layered ways and understandings. Those who seek to impose an ill-fitting binary distinction generally do so in their own interests. Sometimes this is for the sake of simplicity, but as the above brief comments highlight such simplicity can be very misleading. At other times it has just become a lazy shorthand. As that well known “source of all knowledge” tells us “The Global South is a term generally used to identify countries in the regions of Latin America, Africa, Asia and Oceania”.[vi] Well, why not instead just use the actual geographical names Latin America, Africa, Asia and Oceania? This source goes on to comment that “Most of humanity resides in the Global South”.[vii] It is interesting to ponder what this actually means. As noted above this is certainly not true if South here is referring to the Southern Hemisphere.In brief, this is call for meaning, clarity and precision. If we mean that techno-capitalism domiciled in the states of the USA, Canada, the countries of Europe, the Gulf and Australia/New Zealand increasingly controls and exploits the rest of the world then let’s say so rather than couching our language in a mealy mouthed meaningless “geographical” distinction between North and South. But even this is an over-simplification of a different kind. What about China and indeed Russia? Those who really believe that there is something about being “Northern” that makes people dominant, aggressive and exploitative, and something about being “Southern” that makes them ripe for exploitation, believe on. But such dreams will not improve the lives of the world’s poorest and most marginalized wherever they are found. It is indeed a great disservice to the many rich indigenous cultures, traditions, livelihoods, and social formations to be found in Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, Asia and the Pacific. We must always ask ourselves in whose interest words are used. Who benefits most from the use of the terms Global North and Global South?

[i] Apparently first used by Carl Oglesby in 1969 in “Vietnamism has failed … The revolution can only be mauled, not defeated”. Commonweal, 90.

[ii] Despite this notion having been long discredited, I do think it is time that the environmental factors influencing human behaviour are revisited in a more sensitive and sensible way by geographers. The influence of day and night length variations on cultural behaviours in high latitudes is, for example, a fascinating topic of enquiry.

[iii] Two words rather than four; Brandt, W. (1980) North-South: a Programme for Wurvival; Report of the Independent Commission on International Development Issues, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

[iv] The equator runs through southern Somalia, Kenya, Uganda, the Congos, and Gabon.

[v] From the widely used popular source of knowledge about everything, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_North_and_Global_South, 30 March 2023.

[vi] Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_North_and_Global_South, 30 March 2023.

[vii] Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_North_and_Global_South, 30 March 2023.

March 8, 2023

Reflections on slavery: past, present and future

This reflection[i] has three main purposes:

to emphasise the long and diverse history of slavery across the world, and to highlight its differing historical expressions and complexities;to recognise that we cannot change the past nor know the future with certainty, and can only act in the immediacy of the present; andabove all, in the light of the above, to encourage us all to do much more now to eliminate the scourge of modern slavery.ContextIt is easy to say or write that slavery is fundamentally wrong because of the loss of freedoms and violence usually[ii] associated with it. It is far more difficult, though, actually to do something constructive about eliminating slavery at the only time over which we have any control, the present.

The Black Lives Matter and associated anti-slavery protests in the UK in 2020 raised many questions (see image above). I was particularly challenged, for example, by the emphasis of those protesting on the past rather than on contemporary slavery. The majority of banners likewise seemed to highlight the wrongs of past slavery more than they did the wrongs of present slavery. My reflections here seek to grapple with why this was, and why it remains so.[iii] In the years since, there has been much more visible concern in Britain over reparations for past slavery, especially relating to the 18th and 19th centuries, than there has been real action to eliminate contemporary slavery: statues of people who had once been slave-owners have been torn down; streets have been renamed; universities, such as Manchester and Cambridge that have benefitted from donations from people who gained from the slave trade have undertaken enslavement inquiries; and institutions such as the National Trust have published reports on their links with historic slavery.

In part this is because of the overlapping interests between the Black Lives Matter movement and those protesting against slavery.[iv] However, slavery matters in its own right; it is not just a racial matter. In this piece I therefore seek to disentangle the issues of slavery and racism.[v] I want to focus primarily on slavery rather than race. I fully recognise that the two are often intertwined, and there are good reasons why people feel strongly about this intersection, but here I focus on broader issues relating specifically to slavery, and how we respond to the past. I begin with the personal reflections on the origins of my own interest in slavery, and then provide a short conceptual framework that includes a note on definitions of slavery, before highlighting what I see as some of the most difficult and problematic issues concerning slavery past, present and future. My purpose is to encourage us to shift our focus from the past about which we can change nothing, to the present where we do have the option to do so.

My interests in slaveryI have long been interested in slavery, from my days as a boy reading the Bible about the unfairness of Joseph being sold into slavery (Genesis 37) and my difficulty in trying to reconcile my own emerging moral views about slavery with some of Paul’s comments on slaves being obedient to their masters (Ephesians 6, Colossians 3, 1 Timothy 6, and Titus 2). However, I have taken a much more serious and academic interest in slavery since the mid-1970s. Three factors have been particularly important in helping to shape my current understanding of these issues.

First, my doctoral thesis in historical geography written in the second half of the 1970s focused in large part on the changing economic and social structures of medieval Midland England. I was fascinated to learn that slaves could sometimes have had better lifestyles than villeins within feudal society. In this I was heavily influenced by the writings of March Bloch (both his seminal La Société Féodale first publishedin 1939, but also in essays that have recently been collated under the title Slavery and Serfdom in the Middle Ages ) and in the historical records with which I was working.Second, some 20 years ago I encountered modern slavery in England for the first time as I sought to support someone who was trying to rescue a person who had been forced into slavery on their arrival to work in our country. This opened my eyes to the widespread existence of modern slavery in many parts of the UK, and it continues to haunt me as I continue to see such slavery within the country that I call home. Third, my experiences working in Africa during the last 20 years have inevitably forced me to confront issues of colonial history and slavery, especially in Sierra Leone and Ghana. Despite its fraught history both as a Crown Colony until 1961 and then as an independent state since, Freetown and Sierra Leone always cause me to think about the potential for freedom in the human mind and the abolition of slavery;[vi] it is also salutary to recall that it is the home of Fourah Bay College which was founded in 1827 as the first western style university built in Sub-Saharan Africa.[vii] I like to think that there is a connection between freedom and knowledge.

Freetown, 2009

Likewise, I have many fond memories of working in Ghana. A visit to Cape Coast Castle in 2008, though, remains etched in my mind because of one very specific conversation that I had there while visiting the Castle and Dungeon. Initially the castle had been established as a small fort by the Swedish Africa Company in the middle of the 17th century, and it later became one of the most important “slave castles” along the former Gold Coast. Watching a group of European women who were very upset by what they saw, one of my close Ghanaian friends commented that he never quite understood why many Europeans became so emotionally distressed when visiting the castle. I was initially perplexed, but he went on to say that, after all, it was the African people living in the surrounding areas who had sold their awkward cousins and uncles, or people captured in conflicts as slaves to the Europeans in return for guns and other items that they wanted. Slavery had long been a way of life in the region, and had most definitely not been introduced by the Europeans. His matter of fact comments challenged much of what I had previously rather taken for granted about the Triangular trans-Atlantic slave trade.[viii] This trade was undoubtedly coercive, violent and exploitative, but its transactional character and the collaboration of African communities who were willing to sell other Africans for a price to European slavers needs to be recognised in any discussion of this particular expression of slavery.[ix]

Cape Coast Castle, 2008 (as rebuilt by the British in the 18th century)

On concepts and definitionsI have long enjoyed reading Onora O’Neill’s inspirational philosophical writings (see especially the collection of essays published as Justice Across Boundaries, 2016), and have found that many of my own ideas coincide quite closely with hers, especially around obligations, rights and justice (although I have tended to focus on the notion of “responsibilities” rather than “obligations”). In particular, she highlights the difficulties that arise in discussing the rights to compensation for actions in the distant past that are widely considered to be wrong today. Her work is well worth reading at length on this topic; I frequently return to it for clarity on these difficult issues. What follows is in part sparked by reflections on slavery in the contexts of these wider philosophical and conceptual debates. Three challenges seem particularly important.