Elizabeth Adams's Blog, page 35

April 10, 2017

Palms for Passiontide

Palm tree and live oaks at Anwar and Mary Anne's, Jacksonville, Florida. Watercolor.

Palm branches overhead, Mexico City.

A pencil drawing of Quebec-style braided palms, from 2013

Nahuatl (Aztec) braided palm crucifixes and bundles of sacred herbs, Mexico City

Mexico City's Metropolitan Cathedral decorated for Palm Sunday

April 7, 2017

The Mexican Printmakers - Part II

Alfredo Zalce, "La revolucion y la libertad de prensa" (Revolution and freedom of the press), 1945.

This was such an impressive print. I was often struck by the complicated nature of the compositions, always in service to the subject, and how the artists played with variations in scale, distance, density, positive and negative space in order to achieve the most impact.

In this detail you can see how vigorous and free the carving is. Even in a minutely-planned image, that vigor gives an energy and immediacy that are palpable. Look at how different each face is, and how the artist has treated the texture of the clothing, hair, hats -- so much variation, so little repetition. Only a master could achieve this, because those aspects, I'm sure, happened directly during the carving, not in the drawing.

Ignacio Aguirre, "Las tropas constitutionalistas hacen el primer reparto des tierras" (Constitutionalist troops make the first land distribution),1946.

Another great use of perspective and scale.

Ignacio Aguirre Camacho, "Venustiano Carranza arenga los jefes constitutionalistas" (Venustiano Carranza harangues the constitutionalist chiefs), 1947.

I love the large dark figure of Venusiano contrasted with the multiple figures and flags on the top and right . And the many types of marks used to make the ground interesting, then the composition tied together with the white banner. Such a great use of positive and negative.

Leopoldo Mendez, "Deportacion a la muerte" (Deportation to death), 1942

And finally, another enormously effective print that uses perspective, scale, and light to create maximum impact, drawing attention to the faces of the huddled deportees, but insisting that we also look up the line to the malevolent cloud of black smoke in the distance.

Seeing these images up close felt like taking a master class in printmaking - it was a privilege, and I learned a lot.

April 6, 2017

The Mexican Printmakers - Part 1

Jose Chavez Morado, Escuela rural (Country School), 1936

Because I make relief prints, I was very happy to see original prints by of some of the Mexican masters of the early 20th century, in a show about the Arte Moderno movement (Modernism) and Mexican Identity at the Chapultepec Castle. In this post I'm just going to share some of my favorite prints, by different artists using different styles.

Some of these images were made to encourage social programs, agriculture, the building of schools.

Alfredo Zalce, Cosecha de maiz (Corn Harvest), 1948

Adolfo Mexiac, Ejidos comunales (no date)

Alfredo Zalce, Jurado popular (Popular jury), 1945. Look at the confidence and expressiveness of Zalce's carving - he was amazing.

Others commemorated particular events or people.

Alfredo Zalce, Portrait of Venustiano Carranza (first president of the republic) (not dated)

But prints by enormously talented artists were also a major means of political commentary, and I must say they feel more direct and effective than a lot of what goes on today.

Alberto Beltran y Elizabeth Catlett, Detengamos la guerra (Stop the war),1951

Finally, this lithograph seemed particularly timely:

Jose Chavez Morado, La Nube de mentiras (The Cloud of Lies), 1940

March 31, 2017

In the Parks

A yellow swallowtail on a pot of verbena at the Chapultepec castle.

Mexico City has such a reputation as an urban megalopolis with terrible air quality that one wouldn't think it had a lot of green space, but actually, the city's parks are many and beautiful.

The terrace of the castle overlooks the Chapultepec forest in every direction.

The Bosque de Chapultepec is one of the largest urban green spaces in the Western Hemisphere -- it's a forest park of 1,695 acres, twice the size of Central Park. Within the park are a number of museums - the famous Anthropology Museum, the Tamayo art museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art; a large lake (see above, top right); a zoo; many trails and paths and recreational areas where families love to stroll or picnic; and the Castle of Chapultepec itself with its extensive grounds.

A formal garden in the castle's top level courtyard.

Gardens require gardeners: these men had been trimming branches down below, and were struggling with their wheelbarrow, which overturned right after I took this picture.

A grove of palms underplanted with agapanthus, at the foot of the Chapultepec hill.

On certain Sundays, Paseo de la Reforma is closed to traffic and becomes a bike and pedestrian thoroughfare; we were lucky enough to hit one of those days. This is the street when it comes into the Chapultepec Park, giving access to the major museums and zoo.

---

Nearer to where we were staying are the semi-circular Parque Espana, and the oval Parque Mexico, which forms the center of what used to be the Hippodrome, or racetrack. The former course of the racetrack is Avenida Amsterdam, which runs in a gentle oval around the entire park, and the two lanes of traffic are separated by a wide, planted garden of trees and plants with a pedestrian walkway in the center. It's a wonderful place to walk, and we often found ourselves taking this (somewhat longer, but scenic) path whenever we were heading to someplace in the neighborhood.

In both of these parks, we often saw dog trainers with a whole hoard of perfectly-behaved canines. We talked to this young man at right, below, whose charges included four Afghan rescue dogs, and a large pet pig.

For someone like me who is crazy about plants, the parks are an endless source of amazement and pleasure. Many of the plants that thrive in Mexico City are species I know as houseplants, except here they are huge, sometimes attaining the size of trees. There's enough rain here for them to grow, but along with the water-loving rubber trees and azaleas and banana trees, are the native desert plants - cacti and various succulents -- and various monocots like the agaves, orchids, and bamboo. (I think I could happily go there and study and draw plants for the rest of my life.)

Every time we visit I notice more, and become more curious about this very different climate and ecology. And of course the birds and insects are different too; I spent an hour trying to get a good look at some tiny lizards in the Chapultepec gardens; they'd come out into the sun and then scurry around the trunk of the tree, just out of sight, like squirrels.

Of course, life is not so pleasant for the majority of the 22 million people who live in Mexico City; for many of them, just getting water takes up a big part of the day and is never certain. The Guardian ran an excellent photo essay yesterday by a photographer who walked around the entire periphery of Mexico City, documenting the often-dangerous, poor neighborhoods that spread up the sides of the old volcanoes on the edges of the valley. It's an eye-opening look at how much of the world, unfortunately, lives.

March 28, 2017

Drawings from Mexico - 1

A concha bread and two mangoes. I love how when you buy bread or pastries at the panaderia, each individual piece is wrapped in a square of thin waxy paper, which the clerk folds once around the bread, holds by the two open corners and then deftly spins to create a wrapper that won't unwind until you get home.

I was hoping to find time to draw in Mexico City - on other visits it's been pretty spotty, because there never seemed to be enough time. But I think another advantage of staying in an apartment, as well as having been to the city quite a few times before, was that we took more time to hang out at home and in our neighborhood or in cafes. I tried to take my sketchbook with me all the time, but I actually did more work at the apartment, continuing the still life drawings I've been working on for several years. Here's a first installment.

A rooftop terrace cafe overlooking the Templo Mayor - I need to add some color to this one.

We had intended to visit the archaeological site of the excavated Templo Mayor, just to the northeast of the Zocalo, on this particular day but it was hot, closing time was near, and rain threatened, so we opted for a rooftop beer and chips with guacamole; we stayed for an hour on this very pleasant terrace, with its own rooftop garden of cacti and succulents, watching the storm clouds advance over the city from the west.

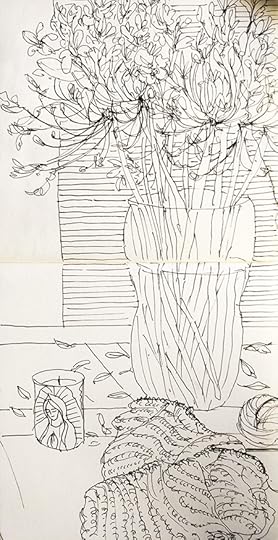

Still life with agapanthus and the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Flowers are incredibly inexpensive in the city, and available from kiosks on many neighborhood streetcorners. This was a huge bouquet of blue agapanthus and orange astroelmaria; it cost $6.00 and the vendor mixed the two types of flowers and cut the thick stems for me with a machete -- it lasted the entire two weeks we were there. The Virgin candle was a little metal tin filled with pink rose-scented wax, since roses were the sign by which she manifested herself to Juan Diego in 1531. I bought it at the supermarket and lit it during the surgeries of two friends back in the U.S. that took place while we were there; it's a ritual of ours to light a candle when remembering friends or family in particular need, and since the Virgin is sacred and omnipresent in Mexico City, it seemed appropriate.

A garden at the Castlillo Chapultepec, with a giant agave, and the city beyond.

Although we'd never been there before, we visited Chapultepec Castle -- former home of the ill-fated Emperor Maximilian -- twice. On this first visit, we climbed up the winding path through the woods to discover a rather unattractive castle on spectacular grounds, with a commanding view of the city. I had wanted to do a lot more drawing there but it didn't happen until I returned to Montreal; I'm working on some now. I do have some good pictures to show you - it was a fascinating place.

March 24, 2017

Getting Started: Portraits of Women at the Museo Nacional de Arte

Unknown Artist, "Portrait of a Woman Wearing a Shawl," 2nd half of 19th C.

In the past year we've made a decision not to run around too much when traveling -- to do one big thing a day, but not get exhausted trying to do several. Just getting around in such a vast city takes both time and effort (our pedometer shows us that we walked and biked an average of 13-14 daily miles, sometimes as much as 20 in a day; we covered 185 miles in two weeks.) The pattern we developed was to make a substantial breakfast -- yogurt, whole grain cereal, fruit, sometimes eggs and bread -- in our apartment, and spend the first few hours of the day on correspondence, writing, working on pictures we'd taken, drawing, consulting maps and internet and making plans for the day. Then we usually took off by bike or metro or foot in the late morning for whatever destination we'd chosen, either packing a lunch or planning to eat a midday meal out, as many Mexicans do, in mid-afternoon. Depending on that, we'd either come back and cook a late dinner (or a light meal) at the apartment, or eat out, usually in the neighborhood where we were staying, and then have some time to read, shower, and relax. At this time of the year, Mexico City, at 7,000 feet, is still very temperate and pleasant - it never got hotter than the mid 70s (22 degrees C), often rained a little around 4 or 5 pm, and was quite cool at night and in the early morning.

One of the main reasons we go to Mexico City - this was our fifth trip - is to be immersed in a culture that has valued art and design throughout its history, from the pre-Colombian right through the present. On our first full day, we decided to go to the Museo Nacional de Arte. We've been before, but there are always special exhibitions -- and we also wanted to revisit their collection of 19th century landscape paintings by Jose Maria Velasco, who really began the Mexican landscape tradition, and whose work shows what the Valley of Mexico was like before the city filled it and pollution obscured the mountains that ring the valley. (There's a post about this from last year, called "The Air We Breathe.")

This time we saw two small special exhibitions that I thought were excellent. The first was a show of portraits of women by self-taught painters - some folkloric, some highly accomplished - including my favorite, the portrait at the top of this post. Here are some others:

Jose Maria Estrada, "Portrait of the girl Manuela Gutierrez," 1836.

I don't have the name of the artist: this painting shows the death of the matriarch of a family.

Unknown artist, "Portrait of a Woman Holding Roses."

The second exhibition showed small sculptures of women, and included a couple of prints about the work of sculpture itself: as a relief-printmaker, I would be pleased and inspired over the next two weeks to see a number of master-works by Mexican linocut and woodcut artists in various exhibitions.

Mardonio Magnaña, "Baptism," 2nd quarter of 20th C., stone

Hollow Female Figure, Seated (Maternity Figure), 6th-10th C., clay

Romulo Rozo, "The Mestiza," 1936, bronze

Gabriel Fernandez Ledesma, "Sculpture and Direct Carving," woodcut, c. 1928.

These strong portraits of women, in paintings and sculpture, stayed with me, especially during "International Women's Day", an observance I find extremely offensive in its encapsulation -- can anyone imagine an "International Men's Day?" However, that day turned out to be very interesting in Mexico City, so stay tuned!

March 20, 2017

Back, slightly battered, with some thoughts on risk and reward

A quiet neighborhood on the way into Mexico City from Benito Juarez Airport.

We returned to the snowy north from two weeks in Mexico City last night. As usual, it was a good trip, filled with color and warmth, a great deal of art, and the activity of a vast metropolis, but complicated this year by the fact that, at the end of the trip, we both had bike accidents. J. wrenched his knee when his bike slid out from under him on the rain-slick marble plaza in front of the Palacio de Bellas Artes, and I took a more spectacular fall the following day when I tried to leave the bike path and hit a curb that was obscured by a deep puddle. J., ahead of me, had just exited safely in what I thought was the same place. My bike stopped and I kept going, landing on my face and smashing my right shin. It all happened so fast I can't tell exactly what happened, except that I tried to break my fall with my hands, and that it hurt quite magnificently when my nose hit the sidewalk. However, that nose didn't break, there wasn't a lot of blood, I was able to walk home with J.'s assistance (he was, of course, horrified), and except for a floor-burned face, fat lip, and impressive swelling and bruising on my leg, I'm OK and on the mend, and J. is too; his injury was in some ways worse but a lot less obvious.

Lying on a bed with ice packs for a day gave me some time to think. I guess some people would consider our style of travel too risky, or perhaps not age-appropriate, but the advantages of being willing to go off the beaten path have been tremendous for us. The surfaces in Mexico City are extremely irregular everywhere; you really have to watch out even when walking on the sidewalks, because there are holes, loose paving stones, bulges and dips, obstacles. The air quality is often terrible. The metro is extremely crowded, and could be - I suppose - scary and confusing, but it's also fast, efficient, and a way to share getting around the city with ordinary Mexicans that you would never experience otherwise. It's important to know what neighborhoods to avoid, and when; which cabs are safe and which aren't. You can buy all your food in fancy restaurants, or you can shop in the local mercados and street markets. If you do go onto the streets, poverty, helplessness, medical calamities, and desperation are going to be in your face, along with awareness of your own privilege and mobility. It helps to have a basic knowledge of the language, and to be able to communicate respectfully and personally with local people and ask for their help if necessary, when you yourself are vulnerable. In sum, we've found that we need to be extremely aware of our surroundings at all times: it reminds me of downhill skiing, where there is risk and real-time decision-making, to be sure, but also the reward of a different world of experience, with full attention in each moment. It only works if you are willing to be changed.

Crowds in the centro historico. There seemed to be few international tourists in the city while we were there.

So much travel has become a prepared and sanitized experience, which is why the unpredictability of global terrorism has kept many Americans, in particular, at home. It would be possibly to go to Mexico City and experience it entirely differently than we do, from luxury hotels to vetted cab rides and guided tours. Personally, I think each of us has to consider the statistics, our health and preparedness, and our own personal balance between risk and discomfort with uncertainty. I have never been afraid of flying; some people are. I regularly ride a bike in Montreal, where many people (especially my age) would not, and the paths are actually smaller, busier, and more dangerous than in Mexico City. We each make choices.

I grew up with a mother who was extremely risk-averse, especially about physical things, and a father who was much less so and determined to make me grow up unafraid. But, in general, people in my family did not travel much, or far: I've had to learn to do it. Part of that process has been learning to cope with some travel anxiety that came from my upbringing, and, ironically, that's been helped by occasionally getting sick or hurt or making a mistake, and finding out that I can survive. J. who was brought up by an international family and traveled a lot more than I did in his youth, has been a huge encouragement and help. I've discovered that if you're willing to travel the way we do way, you learn a great deal more than from taking cabs and staying in sanitized places that are prepared for western tourists. Interaction shows you how kind people are, and how willing they are to help. But it's not only that: I've learned a great deal about myself along the way, and gained a constantly shifting perspective rather than a fixed one. The stability in my life comes from an internal place, rather than external; I am grateful for that. I also realize that it's not what most people want, because at times I too find myself fighting with it, resisting, grasping for certainty and predictability. And then I step back, reconsider, and settle down.

I'll post some images of what we experienced over the next days, as we re-enter our life back home. One of the best aspects of this trip was staying in an apartment rather than the hotel we've used for the past four years; it allowed us to relax more and to cook our own food from the bountiful markets. And I found time to draw and paint; if we were to spend a longer period there I'd take better supplies and be even more intentional about it, because there is so much that calls to me.

March 1, 2017

Professional Affiliations, Artist-Style

Current painting in progress: A view of the St. Lawrence River from Cap-a-l'aigle, Quebec. Pastel, 16" x 12".

When I moved to Quebec from the U.S., one of the differences I gradually noticed was that many people seemed to append a series of letters to their professional signatures. When I inquired about this, I learned that these are the acronyms for professional organizations - a kind of accreditation that is sought after, confers legitimacy, and seems to matter here. For example, in my field of graphic design, the professional association is the Société des designers graphiques du Québec (SDGQ), founded in 1972 to advance the profession, lobby, and help with professional development. In order to become an accredited member, a designer must have at least seven years of practice, and to submit work to a panel of jurists for professional review. Once accepted, the designer can use the letters DGA after his or her name. The same is true for many other types of work here.

As an American, used to competing for design work solely on the basis of the merit of our proposals, I found this odd, and I must admit it never occurred to me to either want or try for such a designation; in fact it felt to me sort of offensive, or exclusionary. I had no idea if the designation helped people get work or not. Was it an ego-thing, I wondered? Was it just "what you do" as a professional here?

Later I noticed that fine artists also join societies, and hope to achieve the status of "master", with the permission to add designations such as "RWCS" (Royal Watercolor Society) to their name. Perhaps someone can enlighten me as to how these organizations started - I know there is a long tradition of them in Britain and probably also in English Canada, but how about in Quebec? Is this a venerable tradition that came from France, or did it have something to do with protecting French Canadians in the professions at the time of the Quiet Revolution? Did Quebec historically have a Guild system?

I've been a member of PEN Canada for years -- and I had to have a book published by a recognized press to qualify -- but the main reason for that is that I believe in the lobbying that organization does on behalf of free speech, and imprisoned and oppressed international writers. I rarely mention it. The point of today's post is to say that, twelve years on, I've joined one of these groups as an experiment - the Pastel Society of Eastern Canada. I'm not sure why; it certainly isn't characteristic. I'm planning to try to participate in their exhibitions and meet other regional artists; it's a way of connecting in real time and space, as opposed to the internet, and here -- in a country where things move a little more slowly, and galleries and exhibition opportunities are few -- that seems potentially worthwhile. However, when reading the information, I saw that after a certain number of acceptances into juried exhibitions, one can become a "signature member;" the highest level is "master pastellist", which requires a certain number of years of successful submissions and then evaluation by a jury (for whose consideration you pay a $300 fee, whether successful or not); then one can append the initials "MPSEC" to one's name. How, I ask myself, do I feel about this? I tend to be dismissive and disinterested. Yet a very high level of professional achievement indeed is required to become a member of, say, the Royal Canadian College of Organists; it's a real mark of recognition, and I was very happy when an organist I know well finally received this honor. My own attitudes are, apparently, somewhat conflicted.

Personally, as artists I feel we are all searching for our best means of expression - something that is elusive and by definition unattainable. I'm bothered by titles, awards, accreditation, degrees and honors which seem to indicate and enshrine some sort of "arrival;" I feel these are irrelevant and unnecessary among real artists because the point of doing art is that we are always in process: we know that we have never "arrived," that each piece is merely a bridge to the next, and that our life in art involves risk, failures and many brand new starting points. So, in that sense, we are all perpetual beginners, necessarily so -- and recognizing this for oneself is actually far more important than achieving levels conferred by some sort of authority. No one would be quicker to point that out than the musician I just mentioned.

But is it ever so simple and idealistic? Taking my own case in point -- I have a liberal arts degree, never went to art school, never had formal training, am essentially self-taught as a designer, artist, calligrapher -- and this was never a drawback for me in the U.S. because no one ever asked for my artistic credentials or professional associations; they just considered my present work, my personality in an interview, my client list, and my ability to do business professionally. But did it make a subtle difference to some of those clients, in New England, that I had graduated from to an Ivy League school? If I'm honest, the answer is probably yes. To others, it may have been a point against me (or they may have liked and accepted me in spite of the fact.) Is it ever possible for merit alone to succeed, or are we all subject to some extent to the rules of our own culture, to the tribes and societies to which we belong, to the secret hierarchy of "who we know" or "where we came from?" Do any of us refrain from using connections (or lines on our resumes) that we think might give us a leg up?

Here, in a quite different society, then, a number of questions come to mind: are these professional associations/titles actually necessary or helpful for one's work? How much of it has to do with ego-gratification? Why do certain cultures ascribe to these behaviors more than others, and why do titles and credentials matter more to certain people? Are these societies/titles a particular feature of Commonwealth countries?

While professional societies may do very good work in helping set standards and educating both practitioners and consumers about best business practices and pricing guidelines -- that's true in America too -- it seems to me that we shouldn't need titles and letters beside our names; this smacks to me of old European systems that came out of the Guilds and later became a way of distinguishing certain artists above others in a way that I find difficult to accept, because I dislike and distrust hierarchies. But I'm willing to hear the arguments for or against, both from North Americans and Europeans. Do you have any experience with this?

February 22, 2017

Drawing a Line

Still life with driftwood, skull, pottery and postcards of a Greek amphora and a painting by Ragnheidur Jonsdottir Ream. pen and ink.

This week, I got back to work. I'm still not back at my normal level of productivity, and I'm still feeling distracted by the news. But I'm working hard on a new writing project, doing Phoenicia's tax accounting, promoting the new books -- and I've been drawing.

It's difficult, isn't it? But the fact is that the longer we let ourselves and our work be derailed by politics, and the more we spin and spin on social media, the more the opposition has us right where it wants us. Without national organizations supporting the arts and humanities, keeping culture alive is going to be the responsibility of all of us, working both individually and collectively. That's no different from what the majority of us have been doing anyway -- most of us have not been funded by those organizations. And in some ways, adversity has the capacity to makes the arts, and artists, grow stronger.

Two pieces of driftwood and a Chinese dish. Charcoal.

A suggestion: go read some Russian poetry around the time of Stalin's rise to power. Read some Polish post-WWII poetry. If you want to know what white privilege is, reflect on the fact that you're upset about losing NPR, while many of your colleagues of color have been dealing with and writing about oppression, violence, loss, walls and the lack of a voice for centuries. I don't have much patience with the complaints and outrage of privileged liberals like myself (well, to be fair, I am more of a radical leftie), and frankly most of our whining is of the shared-outrage-and-ridicule variety, which doesn't do any good except to make us feel better in that moment, in a way that smacks of high school cliques. We need to get on with it: doing our work to the best of our ability, figuring out new paths and strategies, and showing up strongly for our colleagues and friends who don't have the privilege, influence, safety or respect that we do, and are in much greater danger.

Maybe we don't know what to write or say or paint yet, in this new climate where we find ourselves. That's OK. Practice. Just get back at it. I see it like Zen calligraphy or archery: when we draw, or write a poem every day, or practice our instrument, we are preparing ourselves and honing our technique, so that when the moment comes to express ourselves, we will be ready with words or images that are true and sharp. But even more than that, we're talking about being the people we're meant to be, in spite of what is going on. Each of us needs to do whatever is necessary to be strong enough inside to get through this without losing ourselves, our vision, or our love of humanity and what is most noble about it. We have to be able to say, with our actual actions and the examples of our lives, that it is impossible to suppress or destroy the best parts of the human spirit.

There's a reason why that Greek vase, painted by the master Exekias in the 5th C BC, about a story written several centuries before that, has been preserved throughout 2500 years (it's now in the Vatican Museum) -- and there's a reason why I have an image of it on my desk right now.

So think about it: what do you feel like you need? What's keeping you from your work? And let's talk about it and help each other.

February 16, 2017

On non-retirement

Painting in my Vermont backyard, sometime in the early 1990s (photo by Jonathan Sa'adah)

Unlike many people whose working life has been in institutions or businesses, I've always worked for myself, or in partnership with my husband, which is pretty much the same thing. My career has been in graphic design, communications, and publishing, first in print and then on the web, for a long list of corporations, institutions and non-profit organizations. It was challenging, demanding, and well-paid; now, that part of my life is pretty much over. I still have a publishing business, which is also challenging and demanding, and not well paid at all. In addition to the design, editing, illustrating and marketing for the publishing business, I sell some artwork or do a design job from time to time, and I write words and make music, both of which sometimes feel more difficult than the work for which I was paid during the past forty years.

Because of these lifelong interests, I can't imagine "retiring" in the traditional sense, and hope I won't have to. But the transition is significant when moving from paid work to unpaid work; from externally-imposed deadlines to those I impose on myself; and from clearly defined goals to work that may never be "used" or even seen, other than maybe sharing it with a small online audience. I have greater freedom now to decide what to do with my time, how to structure my days, and to what purpose. Although the concept of that much freedom once seemed like paradise, in actuality I haven't found this change particularly easy, though it's getting better. What's helped is trying to become more clear and intentional about what really matters to me, and who I am now.

A lot of my sense of self has always been about accomplishing something or learning something, but for many years the primary expression of that was through being responsible to other people and to organizations with which I've been involved, and meeting their expectations. My writing and artwork, reading and music, including taking piano and voice lessons, were "on the side," though it was crucial for me to keep doing them to whatever extent I could; sometime I felt like I was living two lives at once, plus being a wife, daughter, friend. I'm obviously happier if I'm busy; less happy when I feel aimless or scattered, and fortunate to have been pretty self-motivated and self-disciplined since childhood. What I'm revisiting now is the question "Why, and for Whom?" because the answer to that has shifted, both because of the big arc of life-changes, and because of much faster-moving shifts in the way we share creative work online and in real life.

How do we find a balance in later life, when we are no longer "needed" or even "wanted" in the same ways, or when we can't (or don't want to) keep up the same pace? I don't think the answer lies in becoming more self-centered, although we may have to adapt to being more alone, but actually in being more discriminating and focused about our choices. I want to help others, to be a mentor and friend, to teach, share, and give, and, equally, to learn from younger people, to stay engaged and in touch. I don't have children or grandchildren, so having contact with younger people requires an intentional effort.

But part of being a mentor is actually to be more and more ourselves: to keep doing our work, and living our truest lives. From the older people I've admired and learned from in my own life, it's clear to me that one can continually learn and grow, even with limitations that come with age or infirmity. And for that, one needs the freedom to concentrate, to experiment, to explore -- and also to do nothing, because out of that "no-thing" often comes clarity, peace, and genuine contentment in spite of the chaos of the world at large. That means saying "no" more often, both to myself and others, without guilt. It means not wasting time reading books I don't really want to read, or absorbing negative energy from other people, or losing hours on social media. I want to shed everything material that feels burdensome and unnecessary, and to travel these next years as lightly as possible, but still with focus and purpose.

This period of life is about acceptance of reality, and setting new priorities. Work-for-pay is less central. So is the striving to "be somebody" -- and thank God for that. Time opens up a little -- there are more uncommitted hours in each day -- and yet, the total is finite; the hourglass is starting to run out. Is that a tragedy? Only if we give up, abandon the search, step off the path, or decide we've already arrived. I need to remind myself sometimes, because it's impossible not to get discouraged or tired, but I do know the answer, at least for myself.

Who are we meant to be, in the end? So many people never seem to find an answer to that question. The answer for me is that we are meant to discover our true nature, which some might say "lies in God" or, to put it differently, in our interconnection with, and love for, all life. Discovering myself has always been an inner journey, through creativity, thinking, and being in nature, with the companionship of my beloved partner and a few close friends; for others, it is a different path. However, if we don't find our way into that primary relationship with our own true self by later midlife, we may remain mired in superficiality and materialism and what others think of us, as well as worrying about losing what we think we deserve or have hoarded up. Worse, our most constant companions will be fears, regrets, clinging, and bitterness. Take a look at the difference between the current First Family, and Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter at age 92; could anything be more obvious?