Elizabeth Adams's Blog, page 31

February 7, 2018

Delusions of Grandeur

Napoleon's hat, worn in the Russian campaign.

Yesterday, with several hours between downtown meetings, we went to the current big exhibition at Montreal's Beaux-Arts Museum, about life at Napoleon's court. Ten years ago, the museum received a large bequest of one of the world's largest collections of Napoleonic memorabilia, from Ben Weider, the Montreal-born Canadian fitness entrepreneur. According to the notes on the exhibition, Weider had a lifelong fascination with the French ruler, and believed he had been wronged by history and was poisoned by the English on St. Helena. He was the founder and president of the International Napoleonic Society, became a member in 2000 of the French Legion of Honor (established by Napoleon himself) theories on Napoleonic history. Whatever that has to say about Weider, or Quebec, I won't speculate, but the fact is that in conjunction with major museums and collections in France, the Beaux-Arts has mounted a large and impressive exhibition that does give a pretty good idea of what life at Napoleon's court was like.

Hand-painted Sèvres porcelain.

Hand-embroidered waistcoat and jacket for a man in the Grand Chamberlain's service.

The exhibition includes major paintings by David, Ingres, Gros, Prud'hon and Gerard, as well as gold and vermiel tableware from Napoleon's court; hand-painted Sevres china; hunting rifles; elaborately embroidered clothing; furniture; a collection of cardboard soldiers representing the various regiments; crucifixes, candle-stands and communion vessels from the private chapel; and paintings and artifacts from the exiles on Elba and St Helena.

Portrait of Talleyrand, by Paul Prud'hon.

There were portraits by the great French painters of that time of all the major figures of the court, his two wives, the popes and cardinals -- and there were paintings of hunting, of wars, of favorite horses, of parades through Paris, of women of the court with their children. The overriding impression though, was of a man who calculated how to style himself as Emperor and did everything in his power to establish and maintain his ultimate sovereignty.

Portrait of Raza Roustam, Mameluke (1806) by Jacques Nicholas Paillot de Montabert. Raza Roustam had been kidnapped in Georgia at the age of thirteen and became a Mameluke -- the Arabic term for slave -- in the service of the bey of Cairo. During the Egyptian campaign, he was presented to Napoleon, who afterwards kept him at his side, attached to the royal household; Roustam slept outside Napoleon's bedroom "His primary function was that of a good-natured and non-threatening figure splendidly garbed in muslin and trimmings with a role in the spectacle of everyday life in the imperial court."

"The Dream of Ossian," painted by Ingres for the ceiling of Napoleon's bedroom in the Roman palace he never occupied; Ingres bought back the painting after Napoleon's death and reworked it.

It's astounding that a man who rose to power after the French Revolution had toppled the monarchy could have had such overreach, such megalomania, and established a court with as much excess as the Kings of France. Napoleon even styled his son "The King of Rome," and imprisoned the the pope who had crowned him after installing his own uncle, a cardinal, as the religious figurehead of his realm. And the people who had only a little earlier cried "off with their heads!" accepted it! It's incredible!

I walked through the rooms with a strange combination of disgust mixed with appreciation for the sheer beauty and workmanship in the paintings, textiles, and porcelain in particular. And I was grateful to be seeing these paintings in Montreal, where security is minimal, the galleries aren't crowded and a visitor like me can get close to the surface of the paintings to study them. Regardless of the subjects they were painting, the French artists of that time were astounding masters.

And then we returned home to the news of the current American president's plans for a great military parade: a president who already believes himself above the law, spends the taxpayers' money like water, has no compassion for the poor or disenfranchised, and could easily involve the nation is more wars. There's really not much to say; the agonized eyes of Ossian's dog express the feelings better than words.

January 16, 2018

Greetings from the Deep Freeze

It's one thing to have a few bitter cold days now and then: that's just part of living in the north. But the cold has been unrelenting up here for more than a month; I can hardly remember a winter when it was below 0 degrees F. for so long. The Celsius readings have hovered around -19 to -23, and out in the country they've been in the minus 30s. Today is a heat wave - about 12 degrees F.! It feels almost balmy! The mountain of plowed snow in the studio parking lot has become a mountain range, and I'm grateful every day that I don't have to keep shoveling out a car that's parked on a city street: people are really having a hard time this year.

Between Christmas and New Year's, we built ourselves a new IKEA bed, and completely tore apart and rearranged our bedroom. Meanwhile, my husband's computer underwent an automatic operating system upgrade that trashed everything, so he spent a lot of the holiday week trying to reconstruct his digital life. Then the same thing happened to mine. We had daily backups, so there was little damage or loss, it was just a pain in the neck. He quickly got my computer back up and running, but yesterday I realized that all my accounting files for Phoenicia had been in a different location, and the data starting from the middle of 2016 was gone, and not backed up where it should have been. Today I began reconstructing them. Strangely, it hasn't put me into too bad a mood. Like many other things, I figure I'll just do a little bit every day, and eventually it will be done. The cliches run through my head: "No use crying over spilt milk"; "what's done is done."

We've also had the inevitable mid-winter colds, sneezing and coughing our way through the month. Unlike Europe, our January and February here in eastern Canada tend to be bright and sunny a lot of the time, so I haven't felt depressed by grey days. What the cold does is make me feel cooped up, because I can't walk: it's far too cold and far too icy underfoot for walking-as-exercise. So, although I try not to make New Year's resolutions, I did vow to get back to the pool and to some sort of exercise regimen. That began last week in earnest, and it does feel better.

A double-length cowl in progress, in Alegria yarn from Manos del Uruguay.

I'm working on the design and layout for the new book by Luisa A. Igloria that Phoenicia will be publishing in March, The Buddha Wonders if She is Having a Mid-Life Crisis. And I'm trying to draw a little every day, and finish a knitting project, and cooking soups and stews and baking bread, as well as reading The Odyssey again, along with two friends. We're each reading a different translation (I'm reading Fagles, the others are reading Wilson and Lombardo), one Book a day, and talking about them as we go - a perfect midwinter project that reminds me of Sicily and the Mediterranean, and the Greek cities we visited.

Circe turning Odysseus' men into swine, from The Golden Iliad and Odyssey, by Martin and Alice Provensen: the book that first hooked me on the classical myths, and still has my all-time favorite illustrations. The look on Odysseus' face, in the background, is priceless.

January 11, 2018

Why these shells?

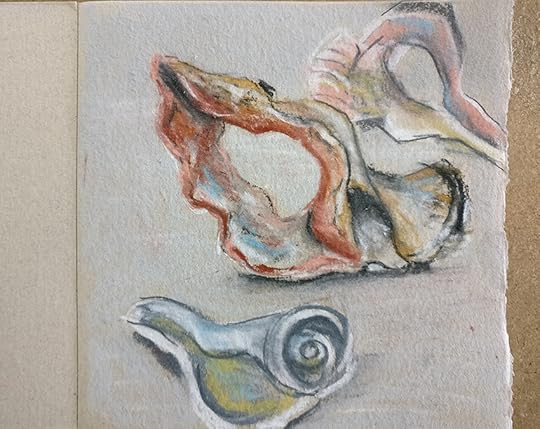

I've been drawing and painting more shells as the year begins.

A friend asked why.

I don't know exactly," I answered, and then thought about it...

I think shells are related, in my visual language, to skulls and bones; I like drawing them and adding them to still lives. And unlike the skulls and bones, clear symbols of mortality, shells are not exactly dead -- they're more like former homes, and related to the sea. So, for me they're evocative of the refugees who undertake perilous journeys across the seas.

But they're also quite challenging to draw properly because their growth is often an off-center spiral, not circular. I like the worn, broken ones especially, both for what they say and because they're beautiful in a different way from something perfectly preserved.

I've collected a lot of shells and beach stones, and most of them are sitting around in my studio. I'm trying to increase my fluency with them, but this is also therapeutic work when I'm feeling unsettled. And I end up with paintings and drawings: something real and tangible, rather than hours of aimless worry about a world I have little power to change. I've thought of writing and illustrating a small book about different land/sea edges: a sort of artist's journal, with essays like the one I wrote a few posts back about the sea. But it's just a thought.

What do you think?

(There are additional paintings and larger images at my artist's website.)

January 2, 2018

Drawing in Sicily

In my studio, before the trip, I indulging in one of my life's pleasures, putting together art supplies for travel. This is a tiny kit of hard pastels, about the size of my phone, from a box of NuPastels I've had (I kid you not) since high school. I used to sketch with compressed charcoal a lot, but lately it's been pen and watercolor, and I thought maybe it was time for a change. Pastels, of course, are one of my studio mediums of choice. After doing some Conté sketching in Mexico City last year, I wanted to expand on that. It was a surprise to be able to get thirty colors into this little box, including Conte in black and sanguine, and a soft graphite pencil. dithered about the paper, though, and finally packed a delicious hemp-and-rag handmade paper block from the Montreal paper-maker, St-Armand. I added a package of hand-cleansing wipes, and a mini-can of hairspray to use as fixative.

I did a few test sketches at the studio. The paper seemed a bit too soft, but I convinced myself it would work, maybe even force me to be looser.

So, one of our first evenings in Palermo, I sat down with the new kit and did this sketch of the artichokes we planned to eat for dinner. No problem with the graphite, but when I began to work with the pastels I found, to my dismay, that the lovely paper in my sketchbook was just too soft. The hard pastels kept tearing up little bits of fiber if I pressed hard enough to leave strong marks, or else they skipped over the surface if I applied too little pressure.

After an hour of struggling, I realized I would have to abandon my idea and just use ink or pencil for the rest of the trip. Looking sadly at all the beautiful colors in my box, I realized I had been seduced by the handmade sketchbook paper, but I had been wrong. I did discover that I really liked having a toned background, rather than white or cream, and it encouraged me to see the values of the subjects differently, and to experiment, so all was not lost! And the artichokes were delicious.

December 31, 2017

The Sea at Year's End

At the end of this emotion-filled year, the images that keep returning to me are of the sea.

Jacksonville, Florida

I'm not an ocean person; I've never lived near the shore. My home has been in the mountains and in pastoral, agricultural landscapes -- and after that, in large cities. Yet I think I've spent more time this year on the edges of the sea than in any other year of my life. I love it, and always have, even though I don't know it very well. And it seems an apt subject for how I feel on this last day of 2017.

Cefalù, Sicily

During the dark and difficult times of my life, I try to return to my breath: its pattern, constancy and immediacy help to center me again. The ocean is like that, too, and because of the hours I've spent watching it in so many different temperaments and clothings -- from the rocky Atlantic shores of Atlantic of New England, to the black volcanic sands of Iceland and the North Atlantic, the shell and sand beaches of Florida, and most recently the very different waters of the Mediterranean -- I have new images of ebb and flow, of constancy and immediacy, that I find calming and helpful in the midst of so much that is not.

Rhode Island

Of course the sea also contains death: it bears on it the hopes and bodies of some of the most desperate people on our planet; it's capable of massive destruction; and its very health is endangered just as its rising water threatens human settlement. But that's not what I am thinking of here. It's the hypnotic movement of the waves that has gone on forever and will go on for millennia after we are gone, a movement that has drawn human beings to stop and watch for as long as they have been on the earth: something wilder and vaster than us, full of terror but also full of beauty and mystery that transcend our fear and bid us to watch, to enter, to ride upon it and dive into it.

I need images like these in order to keep going, in order to keep creating, to keep living as a person of joy and optimism in the face of so much that is entirely opposite, to keep trying to bring light to the people and situations I encounter.

Cefalù, Sicily

This has been a terribly difficult year for anyone who thinks and feels. I've made a conscious decision to limit my time on social media, and watching and reading the news, not only because I find much of the discourse toxic, but because it leads nowhere. We need to be informed and involved, but not to the point of losing ourselves. The bright lights in my life continue to be love, friendship and intelligent, searching conversation, the arts, and nature: I am so grateful for them, and look forward to continuing to find ways to communicate and connect as another year opens up to us. Thank you all for being there, and I wish you all the very best for the new year.

Cefalù, Sicily

December 27, 2017

Knausgaard, Romans and Sicilians: my annual reading roundup, 2017

The faces that launched 3,000 pages: Amitava Kumar with Karl Ove Knausgaard in Reykjavik.

With the sigh that always precedes the first page of a massive reading project, I moved on from the final book of Elena Ferrante's sprawling, steamy, and gritty Neapolitan Quartet, which I loved and which had been a precursor to our travels in southern Italy, to the chilly and tormented Scandinavia of Karl Ove Knausgaard's My Struggle. In the spring of 2017, the writer Amitava Kumar posted a picture of himself with Karl Ove Knausgaard at the Icelandic Literary Festival. I wrote to Amitava (we follow each other on Instagram) saying that the photograph had felt like a sign that I couldn't avoid these books any longer. Later I wrote again: "I'm nearly through three of the volumes, and finding them disturbing, illuminating, and absolutely brilliant. But among my literary friends I can't find a single one who's actually read the books!"

Later, of course, I did find friends who had read them: longtime commenter, poet, and London friend Jean Morris, for instance, who shares my opinion. It seems that readers either love or hate Knausgaard, the latter type dismissing him as a narcissistic egotist, in love with his own voice. I'm in the former camp: I think what he has done is a contemporary continuation of the efforts of Joyce and Wolff to redefine the novel and convey the inner workings of our minds, in all their mundane detail as well as their occasional glorious heights of insight and expression. He has also been willing to cut himself wide open and risk both personal criticism and his closest relationships for the sake of the call of his literary work. I could not do it, but my work won't last, either: Knausgaard's will.

Like the New Yorker critic James Woods, I found the books "fascinating even when I was bored." Much of the writing is not boring at all, and although some women apparently are not, I was riveted by his detailed description of being male, from childhood through adolescence and into adulthood; it's not like anything I've ever read. While his extremely difficult relationship with his father is central to the books, I especially remember his accounts of his own struggles as a parent and husband: being the reluctant but dutiful child-carer for his young children while his wife was going back to school, how emasculated he felt, how bored and resentful; how painful it was for him to enter into a shared social life, how love and family obligation constantly conflicted with his desire to be alone and writing; how this affected his marriage, how guilty he felt for quarreling and how impossible it was not to. I cringed reading about his childhood relationships with other boys, and his sexual problems as a young man, but there too, I felt privileged for the window into a world I didn't know, and grateful that he had the courage to write such things down in excruciating detail.

So I admired his brutal honesty, and found that the greatest impact of the books was the way they forced me to examine or even analyze my own mind and heart: what did I really feel? I suppose I do this anyway, perhaps more than many people, but Knausgaard's honesty insists on your own -- perhaps this is one reason he makes many readers uncomfortable. I'm with the reviewer (Rachel Cusk) who called his work "the most significant literary enterprise of our times."

The statistics on my book list this year are unremarkable: 30 books, instead of the usual 35-40; 12 by women, 18 by men. 17 e-books, 1 audiobook. The lower overall count is because so many of these books were massive, dominated mostly by the Knausgaard series, each of which is over 600 pages. Encouraged by my husband, I've listened to more podcasts, watched more tv drama series and documentaries. I've read a lot of things online, and kept up with blogs and journals, but I was also writing seriously for a lot of these months. So I've been reading all the time, but the mix has changed, and there have been fewer and fewer printed books in my hands: perhaps an ominous statistic for a publisher.

I read and liked Claire-Louise Bennett's Pond -- quirky, disturbing and original -- having seen that Knausgaard recommended her work. Other standout novels in this year's list were Arundhati Roy's The God of Small Things, which I re-read with my book group, and John Berger's G, which I'd somehow never read before.

The Danish Girl, by David Ebershoff, is a sensitive and often painful exploration of one of the life and relationships of one of the earliest transgender surgery patients. Ebershoff was my friend Teju Cole's editor for Open City, and we met at the launch party for that book; I enjoyed talking to him and was glad to read his own writing. I also read Suspended Sentences, a trilogy of three short novels by Nobel winner Patrick Modiano, on the recommendation of my friend, avid reader Bill Gordh -- I'll definitely be reading more of Modiano's work.

Teju's Blind Spot was, of course, a favorite and without doubt the most important book to me, personally, last year: original, beautiful, searching, and truly genre-bending -- the sort of book I wish publishers still risked, but seldom do. I was delighted that Random House published it, after the original Italian printing, and in such a fine edition. I also greatly appreciated the photobooks My Dakota by Rebecca Norris Webb, and La Calle by Alex Webb, with essays and photographs about Mexico.

Other than the novels, much of my reading was connected with travels to Rome in 2016 and Sicily this year. Back when I was studying classics, I focused mainly on ancient Greece, so after being surrounded by Roman architecture, art, and inscriptions in Italy, I was inspired to read more about the ancient Romans, beginning with Mary Beard's eminently approachable S.P.Q.R. and moving on to some of the philosophers I had never read, such as Cicero and Marcus Aurelius. Two books about Sicily that I've found both enjoyable and valuable were The Stone Boudoir: Travels Through the Hidden Villages of Sicily, by Theresa Maggio, a writer from Brattleboro, Vermont, whose family roots are Sicilian, and British historian John Julius Norwich's essential Sicily: An Island at the Crossroads of History.

I've read a number of poetry manuscripts this year, including two that I've chosen to publish through Phoenicia in 2018, but the book of poems that has kept me company was The Poetry of Derek Walcott 1948-2013. As I wrote to Dave Bonta for his year-end list, "It's a big book, and it's been beside the bed all year, where I've dipped into it for an hour or just a few minutes, always finding phrases or metaphors, descriptions and emotions that touch me. Walcott's background was entirely different from mine, but we shared some loves, such as classical literature, European cities, the sea, nature, and watercolor painting. But I've been moved the most by his writing about being a black man in a white world, his writing about the American South, and his poems about the Caribbean, where he felt at home. His mastery of the English language is complete. I think this collection has brought me a lot closer to sensing the man behind the poems." The new book on my bedside will be Les cent plus beaux poemes quebecois: a Christmas gift from my friend Carole, and I pledge to read one poem from it every day.

So, here's the 2017 list: how about yours? What are the most memorable books you've read in past year? Or even the worst ones? I always appreciate the thoughts you share in the comments or send me by email after this annual post. And happy reading in 2018!

---

Book List 2017 (full list, starting in 2002, here)

Les cent plus beaux poemes quebecois, Editions Fides, with art by René Derouin

A Disappearance in Damascus, Deborah Campbell (in progress)*

The Nautical Chart, Arturo Perez-Reverte** (in progress)

Sicily: An Island at the Crossroads of History, John Julius Norwich

Suspended Sentences, Patrick Modiano*

Stand up Straight and Sing, Jessye Norman

The Stone Boudoir: Travels Through the Hidden Villages of Sicily, Theresa Maggio*

Pond, Claire-Louise Bennett*

Dancing in the Dark, (My Struggle, Book 4), Karl Ove Knausgaard*

The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy (re-read)*

A Death in the Family (My Struggle, Book 1), Karl Ove Knausgaard*

Men Explain Things to Me, Rebecca Solnit*

Boyhood Island (My Struggle, Book 3), Karl Ove Knausgaard*

A Man in Love (My Struggle, Book 2), Karl Ove Knausgaard*

The Danish Girl, David Ebershoff*

Blind Spot, Teju Cole

Incontinent on the Continent, Jane Christmas

Meditations, Marcus Aurelius*

Treatises on Friendship and On Aging, Marcus Tertullius Cicero*

S.P.Q.R. A History of Ancient Rome, Mary Beard

One Art (Letters of Elizabeth Bishop), Robert Giroux, Editor*

One Indian Girl, Chetan Bhagat (horrible!)

La Calle, Alex Webb

Saving Rome, Megan K. Williams

G, John Berger*

The Golden Bough, James George Frazer (in progress)*

Beethoven: His Spiritual Development, J. W. N. Sullivan

My Dakota, Rebecca Norris Webb

The Story of the Lost Child, Elena Ferrante*

The Poetry of Derek Walcott 1948-2013

December 23, 2017

Monreale 2: the Duomo

The cathedral, however, wasn't open, and we began to internalize an important Sicilian lesson: shops, churches, and museums close for a long mid-day break. Instead, we took the opportunity to walk around the small town looking for a lunch place that served something besides pizza, and was open during this non-tourist season. Eventually we found a little cafe with a white-aproned waiter proffering a tray of cheese and charcuteries at the door. We took the bait -- it was delicious -- and a blond woman who seemed to be the owner gestured us to one of two small tables at the back. "Perhaps you'd like a sandwich?" she suggested, in English, pointing toward a deli case full of cured meats and cheeses. "We have different Sicilian hams, cheeses...a glass of Sicilian wine?" An hour later we had consumed two delicious prosciutto, cheese and tomato sandwiches, some of that fine Sicilian wine, two almond cookies, and an espresso and a cup of lemon tea, and enjoyed a conversation with the proprietor and her husband, while watching the couple at a neighboring table eat an antipasto platter that looked even more delicious than our panini. Fortified and happy, we headed back down the cobblestone street, past a little market brimming with tomatoes and oranges, and down to the cathedral again, which had just re-opened.

"We should have visited in the morning," was our first thought when we entered the dark interior of what must be, in brighter light, glittering and brilliant. The huge, illuminated Byzantine mosaic in the apse, of Christ Pantocrator (παντός pantos ="all", κράτος, kratos = strength, might, power) dominated our sight for the first minutes, but as our eyes adjusted, we began to be able to see the mosaics all around the walls, and the golden coffered ceiling.

These mosaics were completed somewhat later than the building, and they illustrate biblical stories -- on the top panel in the picture above, you can see Adam and Eve, and the expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Below is the story of Noah and the Ark. It didn't matter at the time if many of the worshippers were illiterate: the cathedral itself was a picture book that they could read.

The floors are covered with the same sort of Cosmatesque pavements as in the Martorana in Palermo, and every inch of this huge interior is gilded or encrusted with stone inlays or mosaics. Because of its size, the space is overwhelming, and I found myself glazing over, unable to take it all in. But perhaps that was also in contrast to the light, airy, enchanting cloister, just a few hours earlier. We had a choice of going into an inner chapel, or climbing up into the northern tower. "Let's go up now, while there's still light," J. said, and I quickly agreed.

In the image below, you can see the southern tower that stands over the town's piazza. From the interior of the cathedral, we bought tickets from a clerk, bundled in scarves, and began climbing ancient stone stairs. On the first landing, we reached a window that looked out into the cloister, and then continued climbing until we came out on the walkway behind the green dome, and continues to the right of the picture, following the great nave of the cathedral.

Beside the walkway, this slanted roof of beautiful glazed tiles. At the end, a small door led into a dark passageway, just wide enough for one's shoulders. Light filtered in through arrow-slits on the cloister side, and also on the cathedral side. I peered through: we were above the choir stalls and organ, and then above the crossing, almost at eye-level with Christ Pantocrator. It was not only a place of worship, but a fortress: the Bishops's archers would have lined this passageway if the cathedral had been attacked, able to shoot down into the sanctuary. Two people descending from the tower met us in the passage, we all turned sideways, and squeezed by one another. J. and I kept going down to the far end, and then out onto the roof, where more steps, lined with intricately-glazed tiles, led up to the tower, with its pointed arches and geometric Arab patterns of tile and stone.

The view, toward Palermo and the sea, was magnificent, but also strategic. In those days, long before airplanes were even imagined, high ground was the best defense, and I began to understand why Italy had so many medieval hill towns. Thoughts of wars and sieges soon gave way to the wonder of standing in such a place.

That wonder increased when I later learned that King William II of Sicily, builder of this cathedral, had given refuge to friends and kinsmen of Thomas Becket, after the newly-consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury refused to do the will of his former friend King Henry II of England, and was forced to flee to the Continent. King William had become betrothed to Henry's youngest daughter, Joan, in 1168, when she was still a child. When Becket returned to England, and was murdered in 1170 by the King's men in Canterbury Cathedral, the marriage was called off, but after Henry did public penance at Becket's tomb, and Beckett was made a saint and martyr by the Pope, the relationship between the two royal houses improved again, and Joan was sent to Sicily where she and William were married, in 1177, just a few years after this cathedral was built, and by all accounts lived happily together.

Joan's mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and her brothers -- of whom Richard I (the Lionhearted), and King John (of the Magna Carta) were two -- had plotted to overthrow Henry; one of the younger brothers had been sent to live with Thomas Becket, and wrote that "Thomas showed me more kindness in one hour than my father did in my entire lifetime." It's almost certain that Joan's sympathies were with the murdered archibishop.

In any case, the earliest known depiction of Thomas Becket anywhere in Christendom, which bears the inscription "Saint Thomas of Canterbury," is in the apse of the Monreale Cathedral. I imagined Joan standing here, looking out over the sea toward England, turning to William, and saying, "We must memorialize Thomas, who was always kind to me."

December 22, 2017

Monreale 1: the Cloister

We took our first excursion out of Palermo on a bright November morning after buying a ZTL pass that allowed us to take our car in and out of the limited traffic zone for one day. This time, in daylight, armed with our phone GPS and better prepared, we managed to find our way out of the tangle of streets that had snared us the first night, and soon were driving south, and already uphill, through Palermo's suburbs. Small trucks loaded with neatly-arranged purple cauliflowers, tomatoes, or artichokes were parked near intersections, and the farmers stood nearby, waiting to sell their produce to local residents who lived in these poorer, crowded neighborhoods. Soon we were out of the city, and heading upward into the mountains.

The piazza outside the Duomo, Monreale

The piazza seen from the opposite direction. The Duomo is the central building behind the tall palm trees.

Monreale is located only about 9 kilometers from Palermo, but the drive takes a while because it goes so far uphill. We encountered our first switchbacks, and stopped at a pull-off to look down on a valley full of orange trees and tiled roofs, and back toward the sea. When we reached Monreale, a medieval hill town, all the streets were sharply angled and narrow, and only the very top of the town was flat. We parked in a commercial lot far below the street level, and climbed back up to the Duomo, or cathedral, in the town's central piazza, through tunnels formed by the tall walls of the old buildings, now full of lung-choking diesel fumes.

The extraordinary main doors of the cathedral, with Arab, Norman, and Italian/Byzantine elements.

The large bronze doors of the cathedral were shut when we arrived, and it was unclear where to enter. On a wall at the right, we pushed open an ancient wooden door to find ourselves in a gift shop that had been set up inside thick stone walls. This room opened onto a courtyard -- and as we stepped out of the stony darkness, we gasped. We were in the cloister of the Benedictine monastery that had been established after the cathedral was constructed, a square bordered by marble columns, each decorated with inlaid mosaic decorations and carved capitals, arranged around four quadrants of lawns inside clipped hedges.

Each quadrant of this garden had a small tree at its center, and the walkways joining them met at a large, low palm at the central point. It was a monastery cloister, to be sure, but unlike any monastery I had ever seen in Europe; the feeling was Arab, Spanish, Andalusian, and yet the carvings were Italian, and Christian. In one corner, a second room of columns formed an open "room" that contained a fountain with a broad basin: clearly reminiscent of an ablution fountain at a mosque.

These were conscious choices. King William II of Sicily, the grandson of Roger II, built the Montreale cathedral in 1174, and dedicated it to the Virgin Mary; today it's one of the most important and justifiably famous monuments on the entire island, but in an oddly remote location. The reason goes all the way back to 831, when the Arabs -- Islam would have only been 200 years old then -- took control of Palermo. The cathedral of Palermo was immediately converted to a mosque, and the Bishop of Palermo was allowed to go into exile in the hills. He settled in the small village of Monreale, overlooking Palermo and the sea, and built a modest church to keep a witness to Christianity. It remained so until the Norman conquest of the island in 1072. The Palermo cathedral was re-consecrated; many of the Norman royalty, including Roger II, were buried there. Partly to honor the memory of the exiled bishop, and partly because the Norman aristocracy was beginning to use this rural area as a hunting retreat, King William II built his great cathedral in Monreale. He also brought a community of Benedictine monks to the area, whose mission was to proselytize and convert the Arabs who formed the majority of the population. As in Palermo, Arab craftsmen were employed in the design and building, and, as we can see all over the world, the new religious leaders incorporated elements of the local religion in order to make it more familiar and acceptable. It's unclear how many Muslims actually converted, but the years of the Norman reign in Sicily were largely and deliberately peaceful for people of different faiths.

King William II of Sicily and his wife, Queen Joan of England, the daughter of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. More about them in the next installment.

I have never been in a space that affected me quite like this cloister. It was one of the most beautiful and calm places I have ever experienced. We wandered through the colonnades and paths for a long time, studying the mosaic inlays and individual carvings, and absorbing the calmness that seemed to emanate not only from its history as a refuge from the outer world, but from the scale, colors, and harmonious placement of the individual elements, which achieved something close to perfection.

This was true for the courtyard as a whole, and also when one looked at the details: the stories carved on the column capitals had been carefully chosen, the inlaid mosaics which never seemed to repeat the same patterns. And instead of flower beds and vines, here were four single trees that reflected this particular place as well as the scriptures common to all the Abrahamic faiths: an olive, a date palm, a pomegranate, and a fig. I thought of my father-in-law saying, "When I think of the Arabs, I like to think of them in Spain." This was not Andalusia, but a place he would have loved just as much.

I washed my hands and forearms in the fountain basin, and we left to go inside the cathedral.

December 16, 2017

Palermo's Mosaic - 2

Next door to St. Cataldo stands the Concattedrale Santa Maria dell’Ammiraglio, also known as the Martorana. Its founding charter dates from 1143, written in Arabic and Greek, and the church must have been completed by 1151, when its founder George of Antioch - an admiral and minister to King Roger II - was buried there. When the Arab traveller Ibn Jubayr visited the church in 1184, he described it as "the most beautiful monument in the world."

Although I had seen pictures of individual elements of the Martorana, I was unprepared for the effect of the interior when I walked inside. Every inch of every surface is decorated, often in minute detail. On the far end of the church, the original Byzantine mosaics in glittering gold set off figures, patterns and scenes in celestial blue, reds, pinks, lighter blues, greens, browns and white. On the nearer end, the columns and ceiling were decorated in a Baroque style between the 16th and 18th centuries, with paintings and architectural details covered in intricate patterns of carved and inlaid marble. The visual effect is overwhelming: you have to sit down.

We were greeted by one of the most famous pieces of art in all of Sicily: a mosaic portrait of Roger II being crowned by none other than a levitating Christ himself.

This portrait was commissioned by Roger himself, and originally placed on the Norman Facade of the building. The Sicilian kings had a longstanding feud with the Pope, who would normally crown them himself -- by bypassing the Pope in this representation and going straight to Christ, Roger was making a bold statement about his right to the throne. His coronation robe has been preserved and is now in a museum in Vienna. On the opposite side is another portrait, also from the original facade, of the church's founder, George, prostrating himself at the feet of the Virgin.

Because I can read some Greek, the mosaic lettering all over the walls and ceiling attracted me like a cereal box: I couldn't help but try to read what was written. Here the letters read "Rogerios Rex" but I was confused until I realized that the Greek "S", or Sigma (Σ) that I expected to see was replaced by a C. I learned later that this is a simplified variation of Σ that was used in Hellenistic handwriting, and on coins, called the "lunate sigma" because of its crescent-moon shape -- it appeared in all the inscriptions in the Palermo area, and must reflect its Greek heritage as well as common usage in religious contexts during that period.

The floor, and all the walls not given to mosaics, are covered in geometric Cosmatesque patterns in colored stone, typical of the Byzantine period in Italy but also reflective of Arab style and crasftmanship. This church contains inscriptions in Arabic, and like St. Cataldo and other monuments we would see later, its architecture derives from Islamic styles also found in north Africa.

This one is shown just slightly smaller than life-size. The red and green starbursts reminded me of poinsettias.

Overhead: full-length portraits of all the apostles, busts of lesser saints and contemporary figures, and the archangels surrounding Christ on a throne, while Biblical stories are depicted on the sides of the arches. My neck began to ache -- a feeling I'd have many times during our stay in Palermo.

Some of my favorite images were, not surprisingly, botanical. I loved this tree growing on rocks: it felt like a place to rest my eyes, but it also gave the same quiet feeling, on a larger scale, as depictions of nature in Ottoman and Persian miniatures.

A French tour group entered the church while we were there, led by a local guide. When he was finished with his introduction and the people were looking around on their own, I sat down and talked to him for a while: he was a young man, and told me he specialized in the Arab-Norman heritage of the area. If we had had more time, and if J. were more fluent in French, we might have hired him to take us around for an afternoon, but I enjoyed our conversation.

Only halfway through our first day, we began to see that "mosaic" was both a literal and figurative term in Palermo, describing not just these Byzantine, 12th century wonders, but the city's past and present history. Africa was never very far away, nor was Greece, nor was the Middle East. The Phoenicians had sailed here first, from Tyre, followed by Greeks and north Africans, then Romans, then Arabs, then the Normans who originally were, of course, "Norsemen" or Vikings. All of these cultures had left their marks and their patterns, and during some periods -- especially the 12th century under Roger and his descendants -- they had coexisted peacefully. During much more of its history, the island had known experienced terrible violence or, at best, constant tension. And yet, these monuments of a better time had been preserved, perhaps as a reminder of what was possible.

December 13, 2017

Palermo's Mosaic - 1

The obscurity of the previous night was banished by a glorious sunrise, and we stood on the balcony of the apartment, looking out over steeples and domes, tiled roofs, and below us, winding cobblestone streets where people began to go about their day. It was time for coffee.

We walked past still-closed shops to find the small cafe recommended the night before by our host. The colors and styles of the buildings were reminiscent of Rome, but where Rome was grand, Palermo seemed grittier, worn, rougher. The light off the sea bathed the stuccoed walls and Baroque facades in a stronger brilliance, while casting the tiny alleys into deep shadow. Old Italian men wearing dark caps stood in groups, bantering, while younger men and even small boys raced by on Vespas and motorcycles. There were few women anywhere, but many tall dark-skinned men also walked or gathered in groups, looking restless, some in western dress and others in North African attire: tunics over flowing robes, small round caps. In the side streets near us we passed small shops selling halal kebabs, couscous, Indian food. None of these people spoke to us, or even looked at us closely, and I tried not to appear to be paying much attention to them. We had never been in southern Italy before, and certainly not in Sicily. The first 24 hours in a new place are for acclimation: getting the lay of the land, and also trying to take its emotional temperature: what's going on, what's safe and what isn't, where should we walk, is there hostility toward tourists, westerners, North Americans; how are the women behaving, are people walking alone, what does their body language say? We have pretty good antennae, and had read up on these places ahead of time, but a lot of the things that create comfort or discomfort are subtle, and even personal. As we walked, I knew that we were both paying close attention, and that we'd compare notes soon.

After we crossed Via Maqueda, a main street that runs, uncharacteristically, straight and parallel to the harbor, we found ourselves in Piazza Bellini, a broad paved square bordered by two historic churches. It had just begun to rain. Cafe Stagnitta was around the back of the piazza, and we entered the typical, rather elegant Italian coffee-bar: narrow, with mirrors on the walls, a glass display case filled with sweets or sandwiches beneath a high counter, several busy clerks in aprons, and a huge, shiny espresso machine. You stand at the counter to drink your espresso and eat a pastry, or pay more to sit at a table. We stood, taking the place of two regular patrons who were just leaving. There were no tables in this tiny room anyway; probably in better weather there were several out on the piazza. I ordered my usual cafe latte decaffeinato and a small lemon-filled pastry, while J. asked for an espresso and a croissant filled with green pistachio cream - a Sicilian specialty. The small white cups clinked in their saucers; the barista smiled at us; the coffee was dark, rich, delicious. I scraped the last bits of foam from my cup with the small spoon, and we paid our bill and stepped out into the drizzling rain, careful not to slip on the slick marble pavement.

--

What had brought us to Sicily? Perhaps it was J.'s obsession with pizza, at first: we kept trying to get to Naples but always seemed to end up in other destinations. I had become even more curious about southern Italy after reading Elena Ferrante's four Neapolitan novels. There was our attraction to volcanos: Vesuvius, of course, south of Naples, but here on Sicily, the continually-active Mt. Etna. But it was the intersection of Sicily's history with our own that had sealed this decision. For me, there was the fact that this island was a major part of Magna Graecia -- the Greeks had established city-states here in the 5th century BC, and fought nearly continual wars with their great rival, Carthage, on the north coast of Africa, close to Sicily's southern coast; I was anxious to visit these ruins. For Jonathan, the Palermo area in particular had unique architectural monuments that blended the Norman kings' Christian religion and Byzantine art with the traditional work of native Arab craftsmen -- the island was mostly inhabited by Arab Muslims when the Normans arrived. Two of those Arab-Norman sites were right here, in this piazza.

We stood outside these buildings for a while, under a tall bell tower covered with geometric Arab motifs, and a towering date palm laden with branches of dark orange fruit. Dark pink bougainvillea bloomed in a courtyard behind a wrought iron fence; along the walls were agaves, palmettos. Where exactly were we: Damascus? Spain? Mexico? Florida?

A narrow path led along the side of the wall, above the piazza, and there we found the entrance to the smaller building, the Church of St. Cataldo, a straight-sided cube with three red domes. St. Cataldo, named after the medieval Irish Saint Cathaldus who came through southern Italy, was built in 1154 by Maio of Bari. Maio was magnus ammiratus ammiratorum or "great admiral of admirals" under the Norman King William I of Sicily , a title derived from the Arabic word "amir": he was an admiral but also a chancellor who wielded a great deal of influence. His primary legacy was to complete the centralisation and consolidation of Sicily that the earlier kings had begun, and he was responsible for a treaty that finally put an end to conflict between Sicily and the Pope. Maio is described variously as a totally honest, upright man and a corrupt womanizer who was the Queen's lover and involved in a plot to kill the King; in any event, he was assassinated not long after this church was built, and for that reason the interior was never finished.

The feeling, as we sat down under the stone domes, was of coolness, solidity, and immense calm. Two young women sold tickets in front of a curtained doorway, and serious conservation work was quietly proceeding in the altar area by white-coated technicians. Another couple sat quietly in wooden chairs. A middle-aged man paid, entered, took one look around, and loudly demanded his money back -- "This is all there is?" he shouted, in a mixture of English and Italian. "And it's under construction? You expect people to pay to see this?" The older of the two women politely and firmly refused to refund his money. "You have entered, you have to pay," she said, "It is how we finance the conservation." He finally gave up and stormed out; the rest of us exchanged amused glances.

The altar itself was original, as was the elaborate mosaic floor, but many of the interior decorations had been lost over the centuries, when the building had been used for other purposes such as a post office. The red color of the domes was probably an error of restoration from the 1800s.

Later I was glad we had seen this church first, both because of the emotional intensity that derived, I thought, from its simplicity, and because we could see the architectural structure so much more clearly than in interiors encrusted with Byzantine mosaics. The windows here, in particular, stood out for their varying, geometric Arab lattice motifs, which gave a lightness that contrasted with the massive arches. I had never been in such a place; Jonathan said it reminded him very much of buildings he had seen in Damascus.

Next: Byzantine mosaics, and King Roger of Sicily.