Elizabeth Adams's Blog, page 37

January 12, 2017

The Gates of Janus

January.

There's a space of time after the end of one year when the new one seems suspended in time, like a train on the platform that we haven't yet boarded, or a person -- awaited but unknown -- who stands on our doorstep, still outside the circle of our acquaintance. We move forward reluctantly, still held by the past: the Christmas tree in the living room, the half-filled tins of cookies, the messages we intended to write over the holidays that still need to be sent. We resolve all sorts of new beginnings but the brandy-soaked fruitcake, baked late, is still improving, and the community pool isn't yet open; surely my good intentions can be put off a few days longer.

Epiphany and Twelfth Night come and go. We've sung all the Christmas music; my choir folder is empty for the first time since September. I've written "2017" a few times now, and each of those Roman numerals inked on the page or appearing on my screen cuts a chink in the armor of the past year; it weakens as the numbers grow into double digits: eight, ten, twelve. The tree has to come down, says my husband, it would be so much easier to do it during this warmer spell. I agree, but bargain for the weekend. He's right, though. The holly berries are brown and falling off their stems, and even the persimmons, which I so happily drew and painted through the season, are soft and shriveled.

Here we are, then, on January 12th. I've finally finished a project that belonged to last year and feel ready to stop procrastinating about several new ones. But I realize that it is not just any new year that's holding me back, it's this year, and the uncertainty about what lies ahead. If I could hold back time, I would.

So I spend my morning reading about ancient Rome and the fall of empire. My intention for the months ahead is to writing something longer about Rome, and about my own life, for which some of these blog posts are notes, a draft. It's difficult to give shape to something formless, but that is the challenge and pull as well. One of the last books I read in 2016 was The Hour of the Star, by Clarice Lispector, in which she shows us her own reluctance to give shape to her protagonist, who both attracts and repels her, perhaps because she senses what she will be forced to do to her in the course of the short novel of her life, in order to be true to the person she is inventing. In this new year where we feel such a lack of control, this exploration of the process of creativity felt somehow comforting.

Silver Roman didrachm from 225-12 BC

Janus, one of the most ancient Roman deities, is always depicted with two faces. He has been associated with the month of January from the time of King Numa Pompilius, seven centuries before Christ. Numa was the second of the seven legendary kings of Rome who ruled after the city's founding by Romulus. He is credited with adding two months, January and February, to the Roman Calendar which formerly began in March and ran through December, followed by an unnamed winter gap of 56 days. The Romans continued to celebrate the New Year at the beginning of March until 154 BC, when the Senate declared January 1 to be the start of the year, probably as an acknowledgement of Janus, whose faces look forward to the future and backward toward the past.

Janus was the god of beginnings, symbolized by gates and doorways; his name, ianus, also means an arcade or covered walkway in Latin, while ianua became the word for any double-sided door, such as an entrance door to a home or the entrance to a temple.

Numa Pompilius is also considered to be the builder of the Temple of Janus, in about 700 BC, one of the earliest buildings in the Roman Forum. The temple was small and rectangular, open to the sky, and enclosed by bronze gates.

According to tradition, the gates of the Temple of Janus were closed when Rome was at war, and opened when at peace. In the Aeneid, Virgil mentions that the gates were closed when the war began between the Latins and the Trojans; Augustus boasted that he had closed the gates three times during his reign.

Sestertius of Nero, 64-66 AD

The emperor Nero issued this coin, showing the closed gates of the temple, in 64-66 AD. It commemorates the end of war with Armenia; the legend reads: PACE P[opuli] R[omani] TERRA MARIQ[ue] PARTA IANVM CLVSIT ("Since the peace of the Roman People was established on land and sea, he closed the Shrine of Janus").

--

The closing of the gates was a big deal, accompanied by ceremonies and proclamations, because it so seldom happened; throughout the centuries Rome was rarely at peace. I can't think of any modern equivalent to these temple gates, certainly not in America, where the waging of undeclared war has fallen to new depths. My sense of dread is not necessarily about wars to come, but more about how war is even defined in 2017. Despite the outward appearance and gentle rhetoric of the Obama administration, America has been engaged in an escalating drone war throughout these eight years, a war that would certainly have continued and perhaps increased under Clinton. Special forces are covertly deployed in many countries; a new 30-year program will modernize and refurbish America's nuclear capability rather than dismantling it. I doubt that even an erratic president will allow a nuclear exchange. But terror abroad and at home, random acts of murder by disturbed persons (often, sadly, military veterans), domestic police violence, racial and ethnic profiling, detentions and deportations, surveillance, and - perhaps most important of all - the divisions in society in general, have increased and will continue to do so, along with the anxiety of human beings everywhere, and the desperate needs of refugees fleeing violence. So it is not a case of closed gates and open ones, as any intelligent person knows, but the emperors would always like us to think so.

December 29, 2016

Creativity, Christmas, and Politics

In December, I didn't have much time for holiday-related creative projects. I was busy with a commissioned pastel painting of an Icelandic seascape, and the linocut illustrations (still not completed) for Dave Bonta's Ice Mountain: An Elegy. J. and I made a trip to central New York to celebrate my father's 92nd birthday, in mid-December. There was a lot of rehearsing and singing with my choir for two Lessons&Carols services, one at the beginning of Advent and one just before Christmas, and of course the music for advent Sundays and the midnight mass on Christmas Eve, but we didn't do a Messiah this year, and that was, frankly, a relief. I managed to bake a couple of batches of cookies, but for the first year in ages didn't make any fruitcakes, better known here as Christmas cakes, at all. I had hoped to make some other gifts, but alas, it didn't happen.

However, during the week before Christmas I made some linocut cards that I wanted to share with you virtually, since I only made twenty or so. This is the third holiday medallion-like image I've made; I guess it's turning into a series. So...Merry Christmas, Happy Holidays to you, dear Readers and Friends!

But through it all, there have been a few drawings. I did this drawing of some quinces at my niece's house in New Hampshire, over Thanksgiving, then the dried-up pomegranate in pencil after I got home:

Yesterday I finally found a box of colored pencils I had misplaced since our move up here, and did a couple more drawings last night:

I like the illustrative quality of this Santa with the subdued background - he was originally a candy box, made of flocked paper, with a tree tucked in his arm and a head that bobs on a spring. He belonged to my maternal grandmother and always came out at Christmas in her home, and now in mine. But I think the persimmons, below, deserve a much bolder treatment than they've received here. However, it was a good opportunity to find out more about working with the pencils.

Often I do better without little pointy things in my hands, although speed of drawing helps a great deal to avoid fussiness. I like the vigor of the pomegranate above, and the spontaneity of this dashed-off, fountain pen sketch of a desktop in my studio, on a sheet of paper that already had a big scribble across it:

As the year draws to a close (uh, no pun intended) I do feel the urge to draw, both for its absorbing and meditative quality that I always find restorative, and because I see commitment to creativity as a radical and hopeful act. Not only does it affirm some of the best qualities of human beings, it speaks to a future with hope. I need to shore up my own defenses against the difficulties to come, but I also want to be doing positive creative things that say, "yes, this is who I am, always have been, and always will be, and nothing can take that away." I will be doing political activism too, sometimes combined with art or writing I'm sure (the first thing is to knit a pink pussy hat for a friend who's going to the Women's March on Washington the day after the inauguration) but I think it is vitally important that we don't allow our deepest selves to become de-railed by anger or fear.

Expressing emotion through art is one way forward, but I think it is more true to myself to continually point toward the tender beauty of the world and its people and the love I feel for them, hoping to encourage deeper thoughtfulness and embody positive emotions, rather than making dark and angry paintings or prints. I'm not talking about putting my head in the sand, or fiddling while Rome burns - not at all. What I'm trying to say is there is harmony, balance, and simplicity around us and within us, even at the worst time and in the worst places: the fact that these qualities exist is a continual encouragement, and we can always cultivate greater ability to find, nurture, and protect them. But I don't know exactly what direction my work, including publication projects, will take as events unfold, and it is part of what I know I'll be facing and exploring in 2017.

December 26, 2016

It's that time again: my book list for 2016

Without further ado, here are the books I read during the past year, in reverse chronological order. Commentary begins below the list.

* indicates books read as e-books

2016

"The Golden Bough," an oil by Joseph Mallord William Turner, shows the scene from The Aeneid that began Frazer's exploration in

The Golden Bough

.

The Golden Bough, James George Frazer (in progress)*

Beethoven: His Spiritual Development, J. W. N. Sullivan (in progress)

The Hour of the Star, Clarice Lispector*

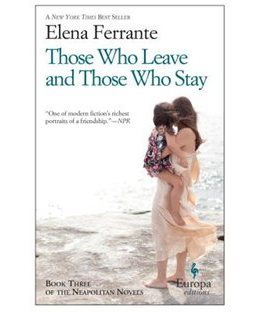

Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, Elena Ferrante*

The Days of Abandonment, Elena Ferrante*

The Story of a New Name, Elena Ferrante*

The Whole Field Still Moving Inside It, Molly Bashaw

Kafka on the Shore, Haruki Murakami

Conversations with a Dead Man, Mark Abley

My Brilliant Friend, Elena Ferrante*

Outline, Rachel Cusk

The Faraway Nearby, Rebecca Solnit*

The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, Haruki Murakami (re-read)

Known and Strange Things, Teju Cole

Ice Mountain, Dave Bonta

Lunch with a Bigot, Amitava Kumar*

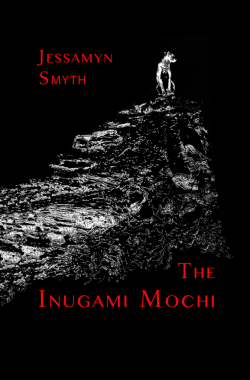

The Inugami Mochi, Jessamyn Smyth*

Pastrix, Nadia Bolz-Weber*

Traveling Mercies, Anne LaMott

A Whole Life, Robert Seethaler*

Monster, Jeneva Burroughs Stone

A Strangeness in My Mind, Orhan Pamuk** (dnf)

Poems, Michael Ondaatje

M Train, Patti Smith

Just Kids, Patti Smith*

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Horrors, J. K. Rowling

Thesaurus of Separation, Tim Mayo

Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter, Cesar Aira*

The Sound of the Mountain, Yasunari Kawabata*

Leaving Berlin, Joseph Kanon*

The Savage Detectives, Roberto Bolano

The Japanese Lover, Isabel Allende*

First, the stats: 32 titles, of which 17 were e-books, either from Kindle or downloaded on OverDrive from the Bibliotheque nationale. I'm pleased to see an exact split between books by female and male authors, too.

There were so many outstanding books this year, that I might be better off to say which ones I don't recommend -- but I'd rather be positive. My vote for best-book/should-last-forever would have to be Roberto Bolano's The Savage Detectives, but I also particularly liked the beautifully written M Train, by Patti Smith, the quirky and detailed Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter by Cesar Aira, Murakami's brilliant Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, and the Elena Ferrante Neapolitan Quartet, of which I've read three and am anxiously awaiting #4, on hold from the library.

Most of you know that I'm a Murakami fan and have read most of his books; I also know he's not to everyone's taste. Wind-Up Bird held up very well the second time around. Kafka on the Shore, which I also read this year, is a fine novel too but not (for me anyway) on the same level as Bird or IQ84, probably my favorite so far of his novels.

Then, what can I say objectively about books by friends, or books I read in manuscript and then published? Of the former, I greatly enjoyed Jessamyn Smyth's The Inugami Mochi, the story of her dog Gilgamesh and their remarkable relationship. I was privileged to take a long walk with the two of them, some years ago, so I felt like I had already had a small window into the material she wrote about after his passing; it's a beautiful book that challenges many people's assumptions about communication and relationship between humans and animals, but for me it was not a big leap. I've already written about Dave Bonta's Ice Mountain: An Elegy, which I liked enough to want to illustrate and publish. And while many illustrious readers and critics have chosen Teju Cole's Known and Strange Things for their own top-ten-of 2016 book lists, and I totally concur, I'm also quietly proud that a couple of the included essays had their origins here on this blog. Jeneva Burroughs Stone's Monster and Tim Mayo's Thesaurus of Separation round out this paragraph, the first by a poet and essayist I met, like Jessamyn, through qarrtsiluni, and the second by a Vermont poet I had never met, but whose work and friendship I now value very much.

Then, what can I say objectively about books by friends, or books I read in manuscript and then published? Of the former, I greatly enjoyed Jessamyn Smyth's The Inugami Mochi, the story of her dog Gilgamesh and their remarkable relationship. I was privileged to take a long walk with the two of them, some years ago, so I felt like I had already had a small window into the material she wrote about after his passing; it's a beautiful book that challenges many people's assumptions about communication and relationship between humans and animals, but for me it was not a big leap. I've already written about Dave Bonta's Ice Mountain: An Elegy, which I liked enough to want to illustrate and publish. And while many illustrious readers and critics have chosen Teju Cole's Known and Strange Things for their own top-ten-of 2016 book lists, and I totally concur, I'm also quietly proud that a couple of the included essays had their origins here on this blog. Jeneva Burroughs Stone's Monster and Tim Mayo's Thesaurus of Separation round out this paragraph, the first by a poet and essayist I met, like Jessamyn, through qarrtsiluni, and the second by a Vermont poet I had never met, but whose work and friendship I now value very much.

The very best book of poetry I read this year was Molly Bashaw’s The Whole Field Still Moving Inside It (The Word Works, 2014.) I recommended this for Dave's crowd-sourced compendium of favorite poetry books of the year, writing, "The poems, ostensibly about farming and farm life, are of course — as Heaney showed us so convincingly — about life itself, in all its beauty, bewilderment, and violence. I was impressed by Bashaw’s use of language, and deeply moved by her ability to describe but not over-explain, because so much of what she talks about defies explanation or even analysis. She leaves things as they are, but also leaves a great deal of room for the reader. Barhaw grew up on small farms in New England and upstate New York, but graduated from the Eastman School of Music and worked for 12 years in Germany as a professional bass-trombonist — so it’s probably no surprise that her poems resonated with me. She’s young and her work has won a bunch of prizes but that doesn’t matter to me; I certainly wish I had published this first book of hers myself and hope to meet the poet someday so I can tell her."

But it's the Ferrante books that have a real hold on me. She manages that rare feat of writing a gripping story that seems absolutely true to life, and writing extremely well. There's a conversation between the elusive Ferrante and author Sheila Heti in the latest issue of Brick, in which Heti remarks that these books make her lament the number of unwritten or unknown books by women, about women, throughout the centuries - what a loss this is for literature, and also for our knowledge of ourselves. I have found them absolutely riveting for the same reasons I love Virginia Woolf: her ability and desire to enter into the heads of her characters and bring their thought processes, and therefore themselves, to life.

But it's the Ferrante books that have a real hold on me. She manages that rare feat of writing a gripping story that seems absolutely true to life, and writing extremely well. There's a conversation between the elusive Ferrante and author Sheila Heti in the latest issue of Brick, in which Heti remarks that these books make her lament the number of unwritten or unknown books by women, about women, throughout the centuries - what a loss this is for literature, and also for our knowledge of ourselves. I have found them absolutely riveting for the same reasons I love Virginia Woolf: her ability and desire to enter into the heads of her characters and bring their thought processes, and therefore themselves, to life.

So, let me know what you think, and also what you've been reading - I always look forward to the annual lists that some of you share with us here, too! And I hope everyone is having some extra time this week to curl up with a book.

December 25, 2016

Happy Holidays!

Wishing you all the joy of simple pleasures this holiday season. Now that my own Christmas has come and is almost gone, I'm looking forward to having some time to actually write again here. Please be safe and warm and peaceful, wherever you are.

December 20, 2016

Ice Mountain: the back story according to Dave

In January, Phoenicia will be publishing Ice Mountain: An Elegy, a book of short poems by my longtime close friend and collaborator Dave Bonta. The cover linocut illustration and design are by me, and the book will also include five of my original linocut illustrations, inspired by Dave's poems.

Dave has just written a post at Via Negativa , "The Ice Mountain Cometh," about the genesis of the book, and how it morphed into a collaboration that includes me, and will soon extend to the videographer Marc Neyes and perhaps others, and I thought you might find it as interesting as I did. In his post, Dave talks not only about poetry itself, but print vs digital distribution, and his own commitment to poetry being accessible to everyone, not just to read, but to use and build on creatively. But he's also aware of the financial realities of putting books into print, and discusses how we made the decisions about publication and creative access for this project.

And, last but not at all least, he tells the story of the "porcupine tree" on the cover and what has strangely happened to it...

The picture of Dave above was taken by Alison Kent, and he notes that the sweater he's wearing was knit by Rachel Rawlins according to a traditional Icelandic design named after Odin, the Norse god who brought the gift of poetry to humans.

(Ice Mountain: An Elegy is now available for pre-order at a special price, and will ship in late January. 10% of all proceeds will benefit local and regional conservation efforts in central Pennsylvania.)

December 10, 2016

Rome IV: Saint Cecilia

November 6

The bells we hear in our apartment, on the hours and before Mass, come from the church of Santa Cecilia, just a few rooftops away. This morning the tall ironwork gates were open when we arrived, and we walked through the courtyard with its Roman urn and still-blooming roses to the wide portico, where, as in many of the churches, Roman inscriptions and reliefs found on the site are embedded in the stuccoed walls. Santa Cecilia is built on the site of the home of an early Christian noblewoman who converted her husband, Valerian, to Christianity, and was martyred in AD 230 for her beliefs. According to the story, at first Cecilia was imprisoned in the steam bath of her own home for three days, but when the door was opened, she was not dead, but came out singing. After that they tried to behead her, but she hung on for three more days. Her body was interred in the catacombs, but discovered several centuries later by Pope Paschal I, and moved in 820 to the church that had been built above her family home.

I had expected the church to contain symbols or images of music -- after all, we choirs celebrate Saint Cecilia's Day on November 22, singing Odes that have been written by famous composers -- but there was only an elderly nun from the convent next door practicing the organ, rather badly, and the sculpture of Cecilia herself in white marble, lying on her side, beneath the altar. The sculptor, Stefano Maderno, was present when her tomb was opened in 1599, and he swore that her body was uncorrupted, and lying on its side, just as he depicted in his work. Cecilia has become known as the inventor of the organ and the patron saint of music, but actually there is little evidence that she was a musician. Nevertheless, we musicians are happy to have a patron saint, and I am especially pleased that she is a woman.

Above the altar is a mosaic by Pietro Cavallini, a painter and mosaic designer who was the major Roman artist of the late 13th century, who influenced his much more famous contemporary, Giotto. Though almost unknown today, Cavallini was a pioneer in breaking with the stiff Byzantine tradition; his figures have solidity, weight, and individuality.

The apse mosaic at Santa Cecilia has a frieze of lambs similar to those in Santa Maria of Trastevere, the major mosaic by the same artist. I puzzled over this smaller work, fascinated by the shimmering schools of red, green and blue fishes, the palm trees dripping with clusters of dates, the tiny head on the priest holding a model church on the far left, and curious about the identities of the two women pictured in the mosaic - who were they?

The exhaustive Blue Guide to Rome answered my question: on the right are the white-bearded St. Peter - holding keys; St. Valerian (Cecilia's husband); and Saint Agatha. On the left are St Paul, holding a book; St. Cecilia; and St. Paschal (Pope Paschal I), holding a model church, with a square "nimbus" around his head that indicates he was still alive at the time the mosaic was made. The palm trees represent the Garden of Eden. The twelve lambs below this scene are the twelve apostles coming from the holy cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem, on either side of Christ, the Lamb of God; and the mosaic inscription describes the finding of St. Cecilia's relics by Pope Paschal and his work to restore the church.

But the church's secret treasure is the Cavallini fresco (c.1300) of the Last Judgement in an upstairs balcony, hidden behind the screen dividing the nun's chapel from the church below. I had read that access was only at certain hours, and only through the convent, so I went into the little bookstore at the back, where another elderly nun was bent over her crochet work, and inquired with my rudimentary Italian, holding a postcard that pictured a detail from the frescoes and pointing to my eyes. She smiled and gestured outside and to the left, and said something like "sonnere," miming a finger pushing a button, which I took to mean "sonnez" or "ring." I thanked her, paid for my postcard, and went to collect Jonathan.

This door behind a magnificent lantana, on the opposite side of the church, doesn't lead to the convent, but it's the same idea.

Outside, we found a wooden door in the building to the left of the church, with a small buzzer beside it.

"Are you sure about this?" he asked, looking dubious.

"That's what she told me," I said, and pushed the buzzer.

A young woman in street clothes answered the door and invited us to come in. Near an even tinier giftshop, with a few postcards, rosaries, and crochet work, a sign was pinned to the doorframe reading "Cavallini," with an arrow beneath it. I pointed to it and said "Cavallini?" She nodded, and replied, "Due." Two euros. I took the coins out of my purse and paid her. Then she said something to a black-clothed figure sitting in the gift shop, and a tiny nun arose and very slowly took the three or four steps out of the little room and moved away from us down a hallway. She was only four and half feet tall, stooped, and so old as to seem ancient; intelligent eyes shone in her face, which was as creased and crumpled as tissue paper, but behind them was a kind of unreadable darkness and immense fatigue. In one hand she held a rosary made of green beads, and when we hesitated, she raised the other hand slightly and with a small gesture of her fingers indicated we should follow her down the hallway.

At the end of the hall was an elevator; we entered. Slowly she pushed the button for the next floor, facing away from us. I glanced at Jonathan; he met my gaze, wide-eyed. When the elevator stopped, she gestured to us to go ahead of her, through a vestibule that connected the church to the convent, furnished simply and beautifully with a wooden bench, and a table beneath a window. A step up led to the unlit balcony at the back of the church, behind its grille. Here, behind the wooden benches for the nuns when they attended mass, were Cavallini's paintings, some very badly damaged, but in places bright and intact.

No photographs of Cavallini's frescoes were allowed. This is an image of the fresco I found on the internet; we certainly couldn't see it like this as there was little light and the figures, from shoulder height, are hidden behind wooden benches that are within a foot or so of the painted wall. Later, at Padua, Giotto would paint a Last Judgement with the apostles seated on thrones in a composition nearly identical to this one.

The nun took a seat to the side, and her fingers moved over her rosary as she watched us, carefully guarding the frescoes. "How old do you think she is? I whispered to J., as we moved across the room, peering at the painted wall over the backs of the benches.

"I don't know. 200!"

Another visitor, a young woman, came into the room, took a cursory glance around, and left. We stayed for perhaps twenty minutes, looking carefully at the portraits of Jesus, apostles and saints on the plaster -- men, women, and angels -- and then nodded to the nun that we were ready to leave. I waited for her to get to her feet, and she again gestured for us to go ahead, but she saw our concern for her as we waited, and slowly glided past us into the elevator. Again she did not raise her head to look at us, until we were finally at the end of the corridor again and I bent down and said "grazie, grazie," with as much warmth in my voice as I could, and she gave me the smallest of smiles and nodded in acknowledgement. Then we opened the door and went out into the world, and she remained in the home where she had spent the past century.

(There will be more about this church and the nuns who care for it, toward the end of this journal)

December 4, 2016

Rome Journal III: Peter

November 6, 2016

The first two nights, exhausted, we slept nearly twelve hours. But today we felt the jetlag more than before, waking for a long time in the night and then rising late. We had a late breakfast/lunch at a cafe in Trastevere, standing up at the counter like the locals to drink our espresso and caffe latte and eat a pastry chosen from the glass shelves below. Then we walked over to Santa Cecelia but found the gates closed -- many of the churches are closed at midday -- so we walked west across Trastevere to the Palazzo Corsini, where there were only a few tourists in the huge family villa with its beautiful gardens and grounds, along with a stunning Caravaggio.

Caravaggio's St. John the Baptist, at the Palazzo Corsini

And a different image of St. John the Baptist, also at the Palazzo Corsini.

Then we walked up the Janiculum hill a second time -- we had been there the first day -- to visit the Tempietto del Bramante, a martyrium on the supposed spot where St. Peter was crucified.

Climbing up the hill to San Pietro in Montorio

The tempietto is a very small temple built by the architect Donato Bramante on the orders of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain in 1502 to fulfill a vow made for the birth of their first son, who died a few years earlier. Now it is enclosed in a courtyard of a Spanish academy, through which you walk in order to reach the tempietto.

It was raining, and we were alone. I walked slowly around the beautiful little temple, and then entered it, standing in the dim circular interior, barely larger than my outstretched arms. I looked at the inlaid marble floor, the simple statues, the crypt that was visible through a round hole in the floor -- and suddenly, unexpectedly, my eyes filled with tears. I stood for a while, blinked them back, went out beyond the ring of columns, and saw Jonathan raising his camera to capture me and the soft, beautiful light on the stones of grey and beige. I shook my head, no, and he lowered the lens, looked at me quizzically. I turned and went back inside.

Bramante's tempietto is considered to be the first example of a perfectly-proportioned, classically-inspired Renaissance building; it harkens back to small circular Roman temples like the Temple of Vesta and Temple of Hercules, but it is miniature, and now very nearly hidden. Located on the site where -- let's say, since we don't really know -- Peter died, on the side of an unmarked hill near the 9th century church of San Pietro in Montorio, it is only found by visitors willing to make a concerted effort to find the path and come at one of the few designated opening times. The circular hole in the floor marks the place where the cross stood. Peter's body was taken away, and is supposedly interred now in the grand center of Roman Catholicism, St. Peter's Basilica; this is, after all, the city of Peter, "on whose rock I will build my church." St. Peter's Basilica represents the Church triumphant, larger-than-life, the center of Catholicism, clearly competitive with Constantinople and Jerusalem. This was something entirely different: a martyrium, a place where one man met his death.

I have listened to the Gospels all my life: Peter, the most earnest disciple, always comes across as over-eager, talking too much, getting it wrong, insisting he'll be faithful and failing, but he was still the leader Jesus chose, perhaps because he was so quintessentially like all of us. I'm not sure I've ever really connected with him; instead I've seen him as a major character in an often-repeated story. But today, standing at the purported site of his awful death -- at his request head-down on a cross so as not to die the same way as Jesus -- I felt vividly present to the man, or perhaps he was present to me. It was more of a human encounter than a religious one -- but maybe more true for that. And I wonder if this place will always represent Rome to me, as much as anything else: a less-than-lifesize statue of a bearded man holding a set of keys, in the dim light filtering in from two small vertical openings, a pavement set in stones of white and red and green, an oculus opening not onto the sky but into the earth.

November 28, 2016

Rome Journal II: All the Gods

November 5, 2016

I've never been in a city where the light is softer or more beautiful than this one. The colors are married to the light and they play together all day long, regardless of whether the sky is bright or overcast or misty or raining hard, as it did today. And when the cobbled pavement is wet and shining, it's gorgeous, but you definitely have to watch your step.

The neighborhood where we're staying, Trastevere, is on the western bank of the Tiber, while the city's historical center was on the east, and its name literally means "across the river." But it is not a new suburb by any means: Trastevere was originally Etruscan, but by the time of the Republic (c. 509 BC) sailors and fishermen had begun to live there, along with Jewish and Syrian immigrants, and the Romans gradually built bridges to connect the west bank to the city. A logical place to construct early bridges was the Tiber Island, just a few minutes' walk from where we are living, in a modernized apartment in a house built around 1600 AD.

Our street is a tiny winding alley barely big enough for the little cars and motorcycles and scooters that do drive down it, but mostly it is a lane for local people walking to and from their houses. There is a famous bakery just a couple of doors away, Biscotti Innocenti, run by a woman who makes hundreds of kinds of delicious, intricate little cookies, and also the shop of someone who seems to restore or copy antique marblework; it hasn't been open yet but through the window I can see all sorts of plaster casts piled atop each other or leaning against the walls.

There are more places to eat nearby than anyone could visit in a lifetime, and the food has been uniformly fabulous. But I'm cooking too: tonight a shrimp risotto made with a bag of nano rice that cost less than 2 euros here and would go for $8 in Montreal. It's fairly quiet and we've slept a great deal, but the bells of nearby Santa Cecelia are ringing right now, at 9:00 pm, as they do to mark all the monastic hours. I haven't visited the patron saint of music yet, but I will, in spite of the gruesomeness of her martyrdom.

We needed a quiet evening tonight to digest our day. In the morning we had crossed the Tiber and walked up to the Largo de Torre Argentina, where an exposed excavation of five Roman temples now houses a colony of wild cats, and from there to Campo di Fiori to see the market and have lunch, a white foccaccia-style pizza stuffed with mozzarella and zucchini blossoms, at Forno, a famous bakery on the edge of the market square.

Campo di Fiori, "Field of Flowers"

From there we walked in the rain to Piazza Navona, looked at the Bernini Fountain of the Four Rivers along with hundreds of other tourists, and went on through the narrow streets to the Pantheon.

Piazza Navona

Heading back, we stopped at the ornately baroque Chiesa de Gesu, the mother church of the Jesuits, and then Piazza San Marco, where we both admitted that we were having a bit of a hard time as the sheer amount of wealth and power began to sink in: wealth that has been concentrated here in families and churches and government for more than two millennia, and shown off in triumphal arches, palaces, military monuments, self-aggrandizement.

"I think I've always identified a lot more with the people who had to deal with this," J. said.

Ponte Sisto, 1473

I've found myself thinking a lot about Empire and what it has meant all through history: the acquisition and concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few elites, won through wars of one kind or another, on the backs of the expendable lives of the ordinary people. The artists we now revere were often practically slaves to the rulers and popes and rich aristocrats who were their patrons, and the hypocrisy between church teaching and the level of their decoration, not to mention the way the popes and cardinals lived, is astounding. We walked home quietly, hand in hand, in a light rain, both of us thinking about the upcoming elections and feeling disturbed: it just goes on and on, like the Tiber flowing under its bridges.

The one we crossed today was built in 62 BC, has survived intact, and been in continuous use ever since. How can you not be amazed by the fact that your feet are touching stones worn smooth for more than two thousand years?

And the Pantheon, that "pan-theon", a temple to all gods, whose dome is still the largest non-concrete-reinforced dome in the world, has also survived. Its huge columns were carved in Egypt and transported by wooden sledges from the quarry to the Nile, then down the river by barge during the spring floods, by boat across the Mediterranean to the Roman port of Ostia, then by barge up the Tiber and rolled or dragged to the building site. Marcus Agrippa had originally commissioned the temple during the reign of Augustus (27 BC to 14 AD); the Emperor Hadrian rebuilt and dedicated it in 126 AD. The temple has been in continuous use ever since, but became a Christian church in the 7th century, which may have saved it from the destruction visited upon many Roman buildings during the Middle Ages.

Here, for the first time, I began to try to get my head around what I was actually seeing. Although my own period of passionate study had been ancient Greece (archly, I had thought of the Romans as copyists, appropriators, imitators), I had also studied some Roman history and art, taken some Latin. The Pantheon had been begun during the reign of Augustus, at the time of Christ. Luke's Gospel, written somewhere around AD 80 or 90, contains the famous Christmas passage about Mary and Joseph having to travel to Bethlehem to register for a Roman census: "And it came to pass in those days, that there went out a decree from Caesar Augustus, that all the world should be taxed." The light filtering through its oculus high above my head, I realized, may have shone on the person who issued that decree; his feet may have walked across this floor.

As I stood under the dome, looking at the Christian sculptures and paintings that now decorate it, and the empty niches above, where Roman gods probably once stood, I also felt wistful. Conquerors have always erased history by writing over it, but I would have liked to stand in the original temple in the presence of Athena and Zeus and Poseidon, gods who had felt alive to me since my childhood, already renamed Minerva and Jove and Neptune by the Romans. But all I saw of them remaining were fragments of some dolphins carved in travertine, high up on the very back of the building's exterior, and between them the raised fork of Neptune's trident.

November 22, 2016

Rome Journal, I

Yes, I've been away. Physically far away, and also silent for some time in order to process recent events, because I didn't want to add unhelpful words to the torrent. But now, we're back, and I'll gradually add some photographs and entries from the journal I kept during the first two weeks of November, when we were in Rome - as it turns out, an entirely appropriate place from which to witness history, and try to record one's own impressions.

November 3, 2016 7:15 am

Jonathan adjusts the electronic window shade in the Boeing 787 and the sun comes up. We're just about to cross Ireland and head out over St. George's Channel en route to London. I've slept at least two hours and feel fairly good as the cabin crew comes around with coffee, tea, muffins. But for the last hour I've been listening to Simon Rattle and the Weiner Philharmoniker play Beethoven's 5th. Earlier in the flight I'd listened to the 1st and 3rd symphonies, but now, after some sleep, and closer to Europe, I feel like hearing the 5th again.

It is, in a word, perfect: the storms of war, the foreboding beginning, the turmoil of the incredible third movement, and finally the resolution and hopefulness of the 4th. I pull off the headphones, shaking my head. This is a touchstone for me, this overplayed work of absolute genius. I rarely listen to it on purpose - of course we all encounter it on the radio, in the background - but when I actually do, each time there is something revelatory. Ten years ago, when Kent Nagano had first come to direct the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal, he did the full Beethoven cycle, and I heard the 5th one night from a seat on the side of the balcony: the live performance, very beautifully played, made me feel I had never really heard it before. And now, Rattle's early recording makes me listen hard again to Beethoven's commentary on the anxiety of his own times, during this week of our anxiety, and reminds me that the human spirit survives in spite of everything.

London, 11:30 am

The flight arrives late at Heathrow, and we have only an hour to change terminals, go through security yet again, and get to our gate. We're waiting for the train that ferries passengers between terminals when I realize that I've left my jacket, the only outerwear I've brought on the trip, under the airplane seat. I decide to head back, agreeing to meet J. at the departure gate. He leaves on the train, and I discover that it's impossible to go back: the doors only open one way, but I remember that there are customer service stations for arriving passengers with connections, so I head up the escalator, berating myself for my stupidity. The British Airways agent calls the arrival gate and explains the problem. "Go on through security," she tells me, "or you'll miss your flight. When you arrive at the gate, have them call again, and we'll hope that someone can meet you there."

I calm down, and go through the required process, find the gate for the afternoon flight to Rome, and ask the boarding attendant to make the call. She does, and suggests that I sit near the desk to wait: "They have the jacket," she says, "and they'll send someone over, but we're going to be boarding soon, so sit close to the desk so we can find you if they get here in time..."

Then I look in the crowded waiting area for J., who should have arrived well ahead of me. But he isn't anywhere to be seen. There's no message on my phone. I send a text; I call but his voicemail picks up; I walk around a little, getting worried. They're calling the flight, but he's nowhere to be seen. Just then a young man arrives at the desk with a black parcel under his arm - it's my jacket! I greet him gratefully and sign a form, and then begin scanning the thinning crowd again. When almost everyone has boarded I see J. hurrying toward the gate, looking disheveled. "My prescription skin medication triggered the scanner, and they totally disassembled me," he said. "My phone and computer had been shunted off along with the carry-on, so I couldn't call you." So much for our decision to take only carry-on luggage! But we pull ourselves together, show our boarding passes, and get on the plane, hoping that all the glitches are now behind us. In a few minutes we're airborne, and soon over the mountains: when we cross them, it will be Italy, for the first time in my life.

November 1, 2016

The Last of Fall

At first, upon leaving, there's the Jacques Cartier bridge, the city bathed in morning light below, the harbor with one or two big boats at the docks, the flat wide expanse of the canal. Then the long cloverleafs off the bridge and around to the south and west, with the old wooden rollercoaster at La Ronde over your shoulder, back onto the busy highway past the Bucky Fuller dome from Expo, the rows of skinny poplars along the banks of the canal, the line of commuters waiting to cross via the old Victoria Bridge. The city's skyscrapers recede in the distance, past the Champlain Bridge, now being rebuilt and surrounded by a giant construction site; the last of the tall urban condos with signs on their roofs, "Vue sur le fleuve," and finally the concrete and steel rapidly yield to trees, grassy fields, flatness, a huge sky.

It's early morning at the very end of October, and the light is tender: ravishing, really. The sky is a pale, slatey blue, dappled with an overall pattern of little clouds, and the soft light from the east washes over trees to which colored leaves still cling, fields that remain green. Two weeks ago, the color was as intense as I've ever seen it. Now the landscape is desaturated, but, to me, perhaps even more beautiful. Everything in the visual field has been turned down not just one notch, but several, and in this greying, filtered morning I feel no trace of the melancholy many seem to associate with the end of autumn; I love these softer shades of lavender and chartreuse and olive, russet and brown, mustard and citron; I like the sense of the earth sleepily yawning and putting itself to bed.

In the summer you always see tractors in these fields, or groups of workers bent over strawberries and beans; in the fall, big machinery harvesting corn or plowing or spreading manure, or a flock of geese or gulls gathering up the leavings. But today there's no human activity; just the long narrow arpents strobing past in the side window like measures marking off a musical score: this one still full of dry standing corn, this one grassy, here a woodlot, the next plowed and ready for spring planting. Far beyond, a house or two, a row of tall windmills, a blue tractor parked at the far edge of a field, a few orange dots that must be pumpkins left on the vine. Flocks of crows haunt the tops of pines; I see a Cooper's hawk that's after something, several big red-tails, and, far ahead, a single flock of Canada geese.

Soybeans.

Corn.

The roadsides have been planted with tall grasses, whose white plumey fronds wave in the wind. Their long stalks are pink, and suddenly the grasses seem like vast flocks of tropical birds on spindly legs, feathers ruffling, resting before a much longer migration than usual.

Maybe I imagine them this way because I, too, am leaving soon, or maybe it's just a desire to populate this landscape with something incongruous: a sign that its once-unfamiliar flatness has become familiar enough to engage my imagination, not just my eyes. I decide to delay my errand across the border long enough to stop and take some pictures, but by the time I exit the highway the light is already changing, the sun a little higher, a little harsher, and the poetry of the morning disappears with a flock of starlings that rise from a field, whirl, and vanish over the horizon.