Terri Windling's Blog, page 99

January 10, 2017

Old stories made new

P.L. Travers (the creator of Mary Poppins) once said: "I shall never know which good fairy it was who, at my own christening, gave me the everlasting gift, spotless amid all spotted joys, of love for the fairy tale. It began in me quite early, before there was any separation between myself and the world. Eve's apple had not yet been eaten; every bird had an emperor to sing to and any passing beetle or ant might be a prince in disguise....Perhaps we are born knowing the tales, for our grandmothers and all their ancestral kin continually run about in our blood repeating them endlessly, and the shock they give us when we first hear them is not of surprise but of recognition. Things long unknowingly known have suddenly been remembered. Later, like streams, they run underground. For a while they disappear and we lose them. We are busy, instead, with our personal myth in which the real is turned to dream and the dream becomes the real. Sifting this is a long process. It may perhaps take a lifetime and the few who come around to the tales again are those who are in luck."

"Fairy stories are related to dreams," mused A.S. Byatt, whose novels and stories are often infused them."...and dreams are maybe most people's first experience of unreal narrative, and to myths. Realism is related to explanations and orderings -- the tale of the man in the bar who tells you the story of his life, the historian who explains the decisions of generals and the decline of economies. Great novels, I believe, always draw on both ways of telling, both ways of seeing. But because realism is agnostic and sceptical, human and reasonable, I have always felt it was what I ought to do. And yet my impulse to write came, and I know it, from years of reading myths and fairytales under the bedclothes, from the delights and freedoms and terrors of worlds and creatures that never existed."

"Raised as I was on the darkest, grimmest of Grimm���s fairy tales," writes Joanne Harris, "I���ve always been very much aware of the dual nature of the world depicted in folklore and story. For every happy ending, there is an equally tragic one; children left to die in the woods; lovers parted forever; villains with their eyes pecked out by crows, or burnt alive; or hanged. Fairytale is a world away from the comfortable assurances of the Disney franchise ��� and surely that was the purpose of those original fairy tales, devised as they were for an audience comprising mostly of adults; often very poor; people whose lives were cruel and harsh, and who would never -- even in fiction ---have accepted to believe in a world in which the shadows did not at least occasionally rival the light."

"Fairy Tales were the refuge of my troubled childhood, " writer and activist bell hooks reminisces. "Despite all the messages contained in them about being a dutiful daughter, a good girl, which I internalized to some extent, I was most obsessed with the idea of justice, the insistence in most tales that the righteous would prevail."

"The great archetypal stories," Jane Yolen notes, "provide a framework or model for an individual's belief system. They are, in Isak Dinesen's marvelous expression, 'a serious statement of our existence.' The stories and tales handed down to us from the cultures that proceded us were the most serious, succinct expressions of the accumulated wisdom of those cultures. They were created in a symbolic, metaphoric story language and then hones by centuries of tongue-polishing to a crystalline perfection.And if we deny our children their cultural, historic heritage, their birthright to these stories, what then? Instead of creating men and women who have a grasp of literary allusion and symbolic language, and a metaphorical tool for dealing with the problems of life, we will be forming stunted boys and girls who speak only a barren language, a language that accurately reflects their equally barren minds. Language helps develop life as surely as it reflects life. It is the most important part of the human condition."

"Magic happens," Maria Tatar observes, "when the wand of language strikes a stone and makes it melt, touches a spindle and turns it into gold, or taps a trunk and makes it fly. By drawing on a syntax of enchantment that conjures fluidity, ethereality, flimsiness, and transparency, writers turn solidity into resplendent airy lightness to produce miracles of linguistic transubstantiation. What is the effect of that beauty? How do readers respond to words that create that beauty? In a world that has discredited that particular attribute and banished it from high art, beauty has nonetheless held on to its enlivening power in children's books. It draws readers in, then draws them to understand the fictional worlds it lights up."

Philip Pullman gives this advice to writers and artists working with fairy tales today: "I���d say to anyone who wants to tell these tales, don���t be afraid to be superstitious. If you have a lucky pen, use it. If you speak with more force and wit when wearing one red sock and one blue one, dress like that. When I���m at work I���m highly superstitious. My own superstition has to do with the voice in which the story comes out. I believe that every story is attended by its own sprite, whose voice we embody when we tell the tale, and that we tell it more successfully if we approach the sprite with a certain degree of respect and courtesy. These sprites are both old and young, male and female, sentimental and cynical, sceptical and credulous, and so on, and what���s more, they���re completely amoral: like the air-spirits who helped Strong Hans escape from the cave, the story-sprites are willing to serve whoever has the ring, whoever is telling the tale. To the accusation that this is nonsense, that all you need to tell a story is a human imagination, I reply, ���Of course, and this is the way my imagination works.'"

Why keep re-telling these old, old stories? I'll give Maria Tatar the last word here:

Because, she says, ���it is through beauty, poetry and visionary power that the world will be renewed.���

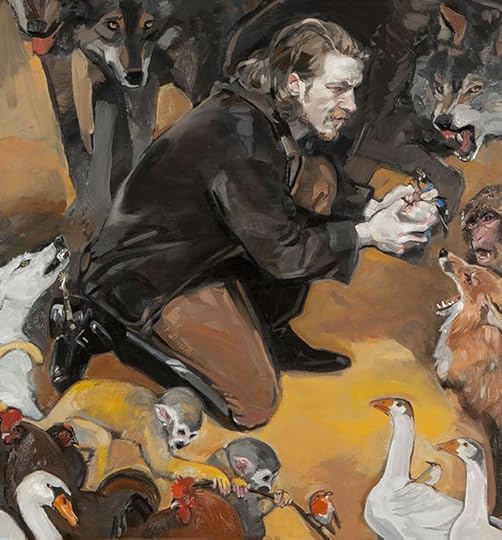

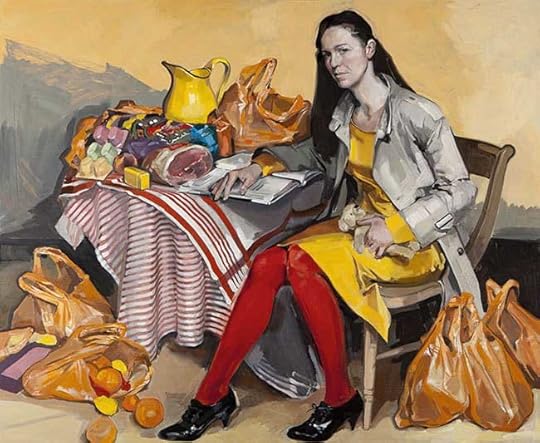

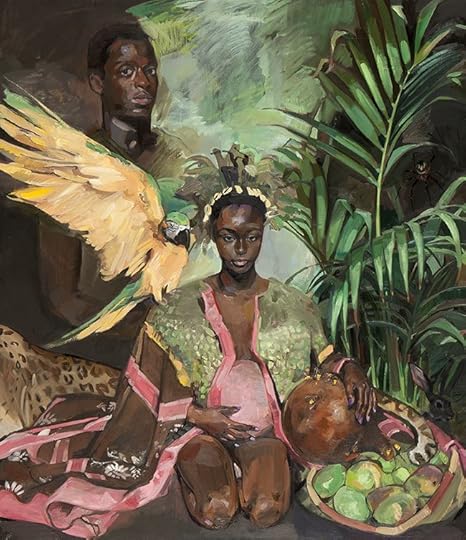

The wonderful paintings today are by Vanessa Garwood. Born in Israel in 1982, Garwood trained in painting and sculpture in Florence, Italy, followed by further studies elsewhere in Europe, Africa, and South America. She is currently based in London.

These paintings are from "And is it true? It is not true, an exhibition inspired by Garwood's childhood love of illustrated storybooks. "The series," she says, "expresses a concern for the future of books in a time where their impact is being diminished by an ever increasingly virtual world. For books -- and also paintings -- as lasting physical objects passed down from generation to generation."

Go here for more information on the show; and here to view more paintings and read the artist's reflections on them.

The paintings above are: Harriet and the Matches, Fitcher's Bird, Molly Whuppie, King Robin, Griselda, The Tailor of Gloucester, and Ananse the Trickster Spider. All rights to the art and text above reserved by the artist and authors. Many thanks to Helen Mason for introducting me to Vanessa Garwood's work.

The paintings above are: Harriet and the Matches, Fitcher's Bird, Molly Whuppie, King Robin, Griselda, The Tailor of Gloucester, and Ananse the Trickster Spider. All rights to the art and text above reserved by the artist and authors. Many thanks to Helen Mason for introducting me to Vanessa Garwood's work.

The Muses of Rooms

From "The Writer Herself" by Janet Sternberg:

"I'm drawn back to a room from my childhood -- the back room of my aunt's apartment. When my parents and I visited, I used to vanish into that room. My means of escape was the typewriter, an old manual that sat on a desk in the back room. It belonged to my aunt, but she had long since left it for the adjoining room, the kitchen. She had once wanted to write, but as the eldest of a large and troubled first-generation American family, she had other claims on her energies as well as proscriptions to contend with: class, gender, and situation joined to make her feel unworthy of literature.

"I now know I inherited some of her proscriptions," Sternberg contines, "but the back room at age nine was a place of freedom. There I could perform that significant act: I could close the door. Certainly I felt peculiar on leaving the warm and buzzing room of conversation, with its charge of familial love and invasion. But it wasn't the living room I needed: it was the writing room, which now comes back to me with its metal table, its stack of white papers that did not diminish between my visits. I would try my hand at poems; I would also construct elaborate multiple-choice tests. 'A child is an artist when, seeing a tree at dusk, she (a) climbs it (b) sketches it (c) goes home and describes it in her notebook.' And another (possibly imagined) one: 'A child is an artist when, visiting her relatives, she (a) goes down the street to play (b) talks with her family and becomes part of them (c) goes into the back room to write.'

"Oh my. Buried in those self-administered tests were the seeds of what, years later, made me stop writing. Who could possible respond correctly to so severe an inquisition? Nonetheless, that room was essential to me. I remember sitting at the desk and feeling my excitement start to build; soon I'd touch the typewriter keys, soon I'd be back in my own world. Although I felt strange and isolated, I was beginning to speak, through writing. And if I chose, I could throw out what I'd done that day; there was no obligation to show my work to anyone.

"Looking back nowl I feel sad at so constrained a sense of freedom, so defensive a stance: retreat behind a closed door. Much later, when I returned to writing after many silent years, I believed that the central act was to open that door, to make writing something that would not stand in opposition to others. I imagined a room at the heart of the house, and life in its variety flowing in and out. Later still I came to see that I continued to value separation and privacy. I began to realize that once again I'd constructed a test: a true writer either retreats and pays the price of isolation from the human stream or opens the door and pays the price of exposure to too many diverse currents. Now I've come to believe that there is no central act; instead there is a central struggle, ongoing, which is to retain control over the door -- to shut it when necessary, open it at other times -- and to retain the freedom to give up that control, and experiment with the room as porous.

"I've also come to believe that my harsh childhood testing was an attempt at self-definition -- but one made in isolation, with no knowledge of living writers. In place of a more expansive range of choices that acquaintance, particularly with working women writers, could have provided, I substituted the notion of a single criterion for an artist. That view has altered with becoming a woman and an artist."

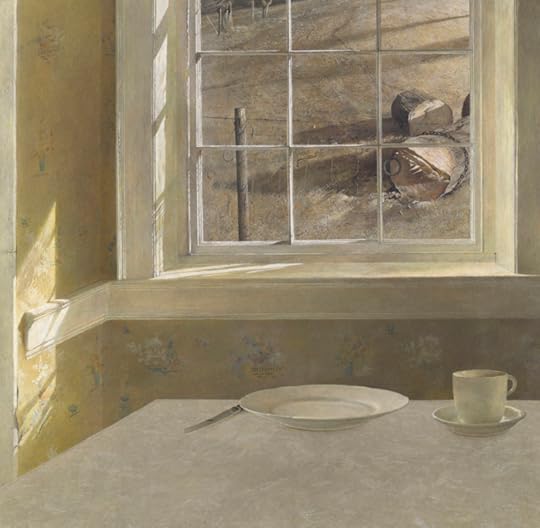

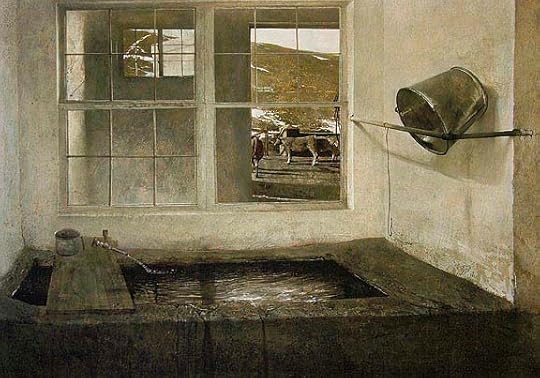

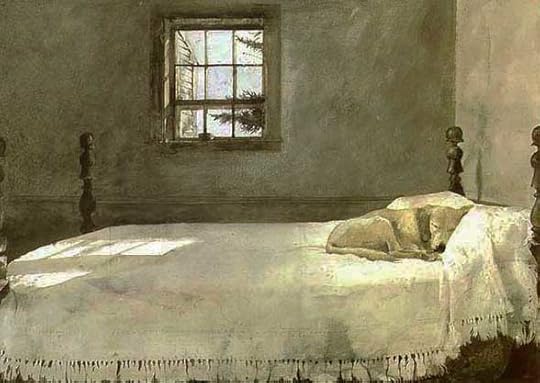

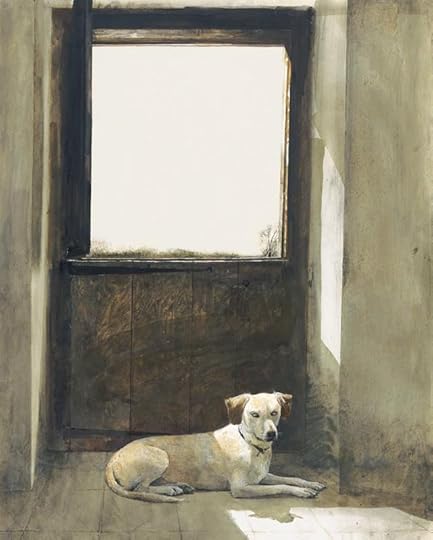

The paintings today are by the great American realist artist Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009), whose subject was the land, people and animals around him in rural Pennsylvania and coastal Maine. He was the son of the illustrator N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945); and his own son, Jamie Wyeth, is also a painter working in the realist tradition. To learn more, I recommend An American Vision: Three Generations of Wyeth Art by James H. Duff.

The passage above is from "The Writer Herself," the introduction to The Writer on Her Work, edited by Janet Sternburg (Virago Press, 1992), which I recommend. The poem in the picture captions is "The Muses of Rooms" by Vern Rutsala (1934-2014) from Poetry Magazine, January, 1990. (Run your cursor over Wyeth's art to read it.) All rights to the text and art in this post are reserved by the authors and artist or their estates.

The passage above is from "The Writer Herself," the introduction to The Writer on Her Work, edited by Janet Sternburg (Virago Press, 1992), which I recommend. The poem in the picture captions is "The Muses of Rooms" by Vern Rutsala (1934-2014) from Poetry Magazine, January, 1990. (Run your cursor over Wyeth's art to read it.) All rights to the text and art in this post are reserved by the authors and artist or their estates.

January 9, 2017

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Tales of sailors, stars, and storms this week, from London and the West Country....

To begin with, two songs by Emily Mae Winters, a singer/songwriter whose work is inspired by history, myth, and literature. Winters was born in England, raised on the Irish coast, and studied music and theatre at Central in London. Her debut album, Siren Serenade, is due out in April.

Above: "Star," a wonderful song referencing a classic poem by John Keats. The video was filmed in the "Poets' Church," St Giles in the Fields, in London.

Below: "Anchor." Both songs can be found on Winters' Foreign Waters EP.

The next two come from The Changing Room, an award-winning music collective in Cornwall performing songs in both English and Cornish. The group centers on songwriters Sam Kelly and Tanya Brittain, working with a range of musicians including Jamie Francis, Evan Carson, Morrigan Palmer Brown, Kevin McGuire, John McCusker, and Belinda O���Hooley.

First, "The Grayhound," a song about Cornwall's lively history of smuggling; and about the ships, known as revenue luggers, whose aim was to hunt the smugglers down. Second, "Gwrello Glaw," a Cornish-language song about weathering storms both real and metaphoric. Both pieces come from The Changing Room's fine second album, Picking Up the Pieces (2016).

And to end with today: "The Bow to the Sailor" by singer/songwriter Ange Hardy, from Somerset. It's from Hardy's third album, Lament of the Black Sheep (2014), which is lovely -- as is all of her work.

The art today is by Jeanie Tomanek. Please visit her beautiful website to see more.

January 5, 2017

Telling the story

I've decided to make Fridays my day for reprinting posts from the Myth & Moor archives. I have nine years of them after all -- having started this blog in 2008 -- so some of them may be unfamiliar to you, depending on when you joined us here. New posts will published Monday to Thursday (with Mondays, as always, dedicated to music); then Friday's archival post will relate to themes that have emerged during the week. The marvelous Le Guin poem excerpted below first appeared here in autumn 2014. It's a poem about women writers and storytellers, reprinted today with a little more art. Additional excerpts from the poem are tucked into the picture captions.

I see her walking

on a path through a pathless forest

or a maze, a labyrinth.

As she walks, she spins

and the fine threads fall behind her

following her way,

telling

where she is going,

telling

where she has gone.

Telling the story.

The line, the thread of voice,

the sentences saying the way.

(from "The Writer On, and At, Her Work)

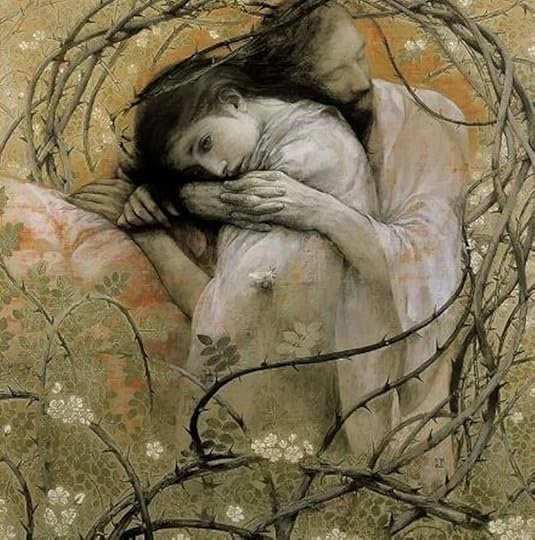

The magical art in this post is by painter and illustrator Toshiyuki Enoki. Born in Tokyo in 1961, he was trained in traditional Japanese painting, lacquer painting, and western painting techniques. Please go here to see more of his work.

The poem excerpted above, and in the picture captions, is from The Writer on Her Work, edited by Janet Sternberg (Virago Press, 1992); it also appears in Le Guin's collection The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination (Shambhala, 2004). I recommend seeking it out to read in full. All rights to the text and art above are reserved by the author and artist.

The poem excerpted above, and in the picture captions, is from The Writer on Her Work, edited by Janet Sternberg (Virago Press, 1992); it also appears in Le Guin's collection The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination (Shambhala, 2004). I recommend seeking it out to read in full. All rights to the text and art above are reserved by the author and artist.

The community of storytellers

From "Nine Beginnings" by Margaret Atwood:

"You learn to write by reading and writing, writing and reading. As a craft it's acquired through the apprentice system, but you choose your own teachers. Sometimes they're alive, sometimes dead.

"As a vocation, it involves the laying on of hands. You receive your vocation and in your turn you must pass it on. Perhaps you will do this only through your work, perhaps in other ways. Either way, you're part of a community, the community of writers, the community of storytellers that stretches back through time to the beginning of human society.

"As for the particular society to which you yourself belong -- sometimes you'll feel you're speaking for it, sometimes -- when it's taken an unjust form -- against it, or for that other community, the community of the oppressed, the exploited, the voiceless. Either way, the pressures on you will be intense; in other countries, perhaps fatal. But even here, speak 'for women,' or for any other group that is feeling the boot, and there will be many at hand, both for and against, to tell you to shut up, or to say what they want you to say, or to say it a different way. Or to save them. The billboard awaits you, but if you succumb to its temptations you'll end up two-dimensional.

"Tell what is yours to tell. Let others tell what is theirs."

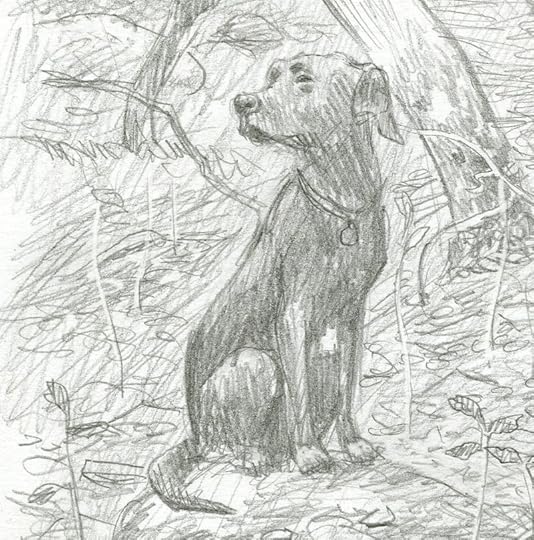

Words: The passage by Margeret Atwood is from "Nine Beginnings," published in The Writer on Her Work, edited by Janet Sternburg (Virago Press, 1992). The poem in the picture captions is from Allegiances: New Poems by William Stafford (Harper & Row, 1970). All rights reserved by Margaret Atwood and the Stafford estate. Pictures: Tilly at the Fairy Spring on Chagford Commons.

Words: The passage by Margeret Atwood is from "Nine Beginnings," published in The Writer on Her Work, edited by Janet Sternburg (Virago Press, 1992). The poem in the picture captions is from Allegiances: New Poems by William Stafford (Harper & Row, 1970). All rights reserved by Margaret Atwood and the Stafford estate. Pictures: Tilly at the Fairy Spring on Chagford Commons.

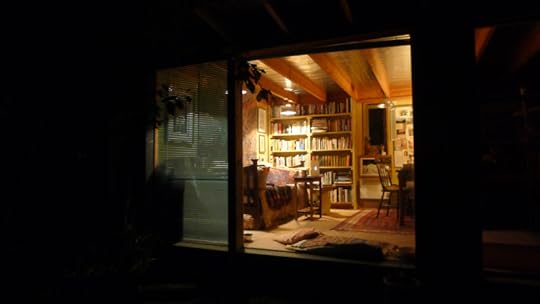

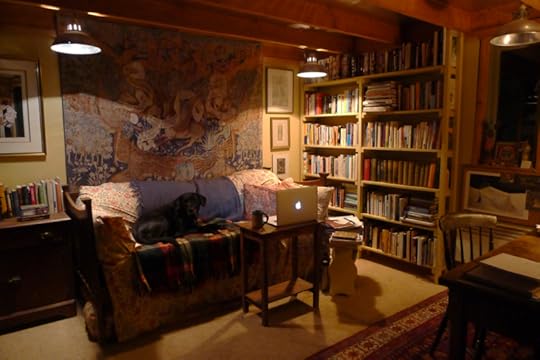

January 4, 2017

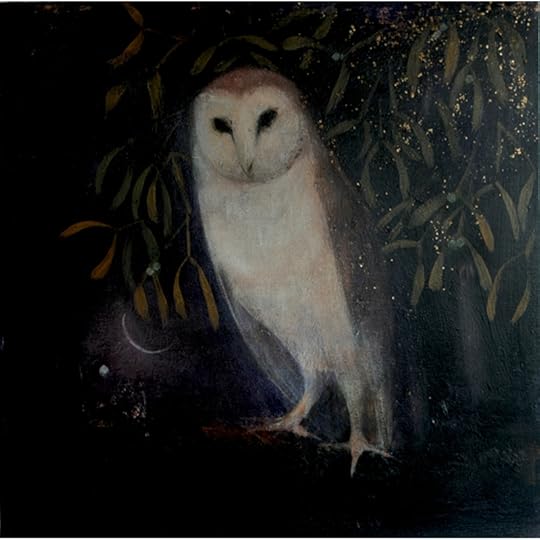

A parliament of owls

At this time of year the mornings are dark, so I climb the hill to my studio on a pathway lit by moonlight and stars. I unlock the cabin, light the lamps, and Tilly settles sleepily on the couch. Behind us, the oak and ash of the woods are silhouettes cut out of black paper; below, the village lies in a bowl of darkness, the outline of the moor on its rim. I can hear water in the stream close by, and owls calling from the woodland beyond. The sun rises late, the days are short, and the owls are a regular presence.

In the myths and lore of the West Country, the owl is a messenger from the Underworld, and a symbol of death, initiation, dark wisdom. She is an uncanny bird, a companion to hedgewitches, sorcerers, and the Triple Goddess in her crone aspect. There are owls in the woods all year long, of course, but winter is when I know them best: as I climb through the dark guided by a small torch, and my dog, and the owls' parliament.

In her essay "Owls," Mary Oliver writes of her search for the birds in the woods near her home -- describing her quest, and the passage from winter to spring, in prose that takes my breath away:

"Finally the earth grows softer, and the buds on the trees swell, and the afternoon becomes a wider room to roam in, as the earth moves back from the south and the light grows stronger. The bluebirds come back, and the robins, and the song sparrows, and great robust flocks of blackbirds, and in the fields blackberry hoops put on a soft plum color, a restitution; the ice on the ponds begins to thunder, and between the slices is seen the strokes of its breaking up, a stutter of dark lightning. And then the winter is over, and again I have not found the great horned owl's nest.

"Finally the earth grows softer, and the buds on the trees swell, and the afternoon becomes a wider room to roam in, as the earth moves back from the south and the light grows stronger. The bluebirds come back, and the robins, and the song sparrows, and great robust flocks of blackbirds, and in the fields blackberry hoops put on a soft plum color, a restitution; the ice on the ponds begins to thunder, and between the slices is seen the strokes of its breaking up, a stutter of dark lightning. And then the winter is over, and again I have not found the great horned owl's nest.

"But the owls themselves are not hard to find, silent and on the wing, with their ear tufts flat against their heads as they fly and their huge wings alternately gliding and flapping as they maneuver through the trees. Athena's owl of wisdom and Merlin's companion, Archimedes, were screech owls surely, not this bird with the glassy gaze, restless on the bough, nothing but blood on its mind.

"When the great horned is in the trees its razor-tipped toes rasp the limb, flakes of bark fall through the air and land on my shoulders while I look up at it and listen to the heavy, crisp, breathy snapping of its hooked beak. The screech owl I can imagine on my wrist, also the delicate saw-whet that flies like a big soft moth down by Great Pond. And I can imagine sitting quietly before that luminous wanderer the snowy owl, and learning, from the white gleam of its feathers, something about the Arctic. But the great horned I can't imagine in any such proximity -- if one of those should touch me, it would be the center of my life, and I must fall. They are the pure wild hunters of our world. They are swift and merciless upon the backs of rabbits, mice, voles, snakes, even skunks, even cats sitting in dusky yards, thinking peaceful thoughts. I have found the headless bodies of rabbits and bluejays, and known it was the great horned owl that did them in, taking the head only, for the owl has an insatiable craving for the taste of brains. I have walked with prudent caution down paths at twilight when the dogs were puppies. I know this bird. If it could, it would eat the whole world.

"In the night," writes Oliver, "when the owl is less than exquisitely swift and perfect, the scream of the rabbit is terrible. But the scream of the owl, which is not of pain and hopelessness, and the fear of being plucked out of the world, but of the sheer rollicking glory of the death-bringer, is more terrible still. When I hear it resounding through the woods, and then the five black pellets of its song dropping like stones into the air, I know I am standing at the edge of the mystery, in which terror is naturally and abundantly part of life, part of even the most becalmed, intelligent, sunny life -- as, for example, my own. The world where the owl is endlessly hungry and endlessly on the hunt is the world in which I too live. There is only one world."

Like Oliver, I strive to create and inhabit a "becalmed, intelligent, sunny" life -- fashioned from ink and paint, old storybooks, and rambles through the hills with the hound -- but darkness, mortality, and mystery are the flip side of that coin. I remember this during the winter months, on the dark path up to my studio. I remember it when my body fails and death glides by on a horned owl's wings; it does not come to my wrist, not yet, thank god, but some day it must, and it will. I remember it when the dark daily news intrudes on my studio solitude, demanding response, outrage, activism. I resist the dark. My life has known too much dark and I want no more of it. I'm a creature of dawn...but the nightworld is our world too. There is only one world.

"Most people are afraid of the dark," writes Rebecca Solnit (in a beautiful essay on Virginia Woof). "Literally, when it comes to children; while many adults fear, above all, the darkness that is the unknown, the unseeable, the obscure. And yet the night in which distinctions and definitions cannot be readily made is the same night in which love is made, in which things merge, change, become enchanted, aroused, impregnated, possessed, released, renewed.

"As I began writing this essay," Solnit continues, "I picked up a book on wilderness survival by Laurence Gonzalez and found in it this telling sentence: 'The plan, a memory of the future, tries on reality to see if it fits.' His point is that when the two seem incompatible we often hang onto the plan, ignore the warnings reality offers us, and so plunge into trouble. Afraid of the darkness of the unknown, the spaces in which we see only dimly, we often choose the darkness of closed eyes, of obliviousness. Gonzalez adds, 'Researchers point out that people tend to take any information as confirmation of their mental models. We are by nature optimists, if optimism means that we believe we see the world as it is. And under the influence of a plan, it���s easy to see what we want to see. It���s the job of writers and explorers to see more, to travel light when it comes to preconception, to go into the dark with their eyes open.' "

That is indeed our job. So I climb through the dark, and open myself to its beauty, its terrors. And I sit down to write.

The art today is by Catherine Hyde, an extraordinary painter based in Cornwall. Catherine trained at Central School of Art in London, and has been exhibiting her work in galleries in London, Cornwall, and father afield for over thirty years. In 2008 she was asked to interpret Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy���s fairytale The Princess��� Blankets, which won the English Association���s Best Illustrated Book for Key Stage 2 in 2009. Her second book, Firebird written by Saviour Pirotta, was awarded an Aesop Accolade by the American Folklore Society in 2010. Her third book, Little Evie in the Wild Wood written by Jackie Morris, is a twist on the Red Riding Hood fairy tale. She both wrote and illustrated The Star Tree, which has been nominated for the 2017 Kate Greenaway Award and shortlisted for the 2017 Cambridgeshire Children���s Picture Book Award. I recommend all four books highly.

Regarding her work process, she says: "I am constantly exploring the places between definable moments: the meeting points between land and water, earth and sky, dusk and dawn in order to capture the landscape in a state of suspension drawing the viewer to the liminal spaces that lie between dream and consciousness.���

Please visit Catherine's website, blog, and online shop to see more of her art.

The passage by Mary Oliver is from "Owls" (Orion Magazine, 1996). The passage by Rebecca Solnit is from "Virginia Woolf���s Darkness: Embracing the Inexplicable" (The New Yorker, 2014). The poem in the picture captions is from New & Selected Poems by Mary Oliver (Beacon Press, 1992). All right reserved by the authors. The paintings by Catherine Hyde are: a detail from The Falling Sar, The Wild Night Ascending, The Soft Hush of Night, The Running of the Deer, The Golden Path, and The Sleeping Earth. All rights reserved by the artist.

The passage by Mary Oliver is from "Owls" (Orion Magazine, 1996). The passage by Rebecca Solnit is from "Virginia Woolf���s Darkness: Embracing the Inexplicable" (The New Yorker, 2014). The poem in the picture captions is from New & Selected Poems by Mary Oliver (Beacon Press, 1992). All right reserved by the authors. The paintings by Catherine Hyde are: a detail from The Falling Sar, The Wild Night Ascending, The Soft Hush of Night, The Running of the Deer, The Golden Path, and The Sleeping Earth. All rights reserved by the artist.

January 3, 2017

Beginning again

At the beginning of a new year, it's a useful time to reflect on the process of starting new creative work -- for no matter what stage we're in at the moment (beginning, middle, or end), when the work is done, it's back to square one and we're facing the blank page once more. Experience only goes so far. Unless we're writing the same book over and over, or painting the same image time after time, we must re-learn our craft and acquire the skills to bring each new piece to life.

Dani Shapiro, in her excellent book Still Writing, reflects on the crucial moment of beginning, and where we find our entry point:

"For some writers, it's character. For others, it's place. What's our way into the story? When do we have enough to begin? If we're climbing a mountain, we need something to grab on to. We wedge our foot into a crevice in the rock and pull ourselves up. We are feeling our way in the dark.

"For some writers, it's character. For others, it's place. What's our way into the story? When do we have enough to begin? If we're climbing a mountain, we need something to grab on to. We wedge our foot into a crevice in the rock and pull ourselves up. We are feeling our way in the dark.

"We have nothing to go by, but still, we must begin. It requires chutzpah -- the Yiddish word for that ineffable combination of courage and hubris -- to put one word down, then another, perhaps even accumulate a couple of flimsy pages, so few that they don't even start the smallest of piles, and call it the beginning of a novel. Or memoir. Or story. Or anything, really, other than a couple flimsy pages.

"When I'm between books," Shapiro says, "I feel as if I will never have another story to tell. The last book has wiped me out, has taken everything from me, everything I understand and feel and know and remember, and...that's it. There's nothing left. A low-level depression sets in. The world hides its gifts from me. It has taken me years to realize this feeling, the one of the well being empty, is as it should be. It means I've spent everything. And so I must begin again.

"I wait. I try to be patient. I remember Colette, who wrote that her most essential art was 'not that of writing, but the domestic task of knowing how to wait, to conceal, to save up crumbs, to reglue, regild, change the worst into the not-so-bad, how to lose and recover in the same moment that frivolous thing, a taste for life.' Colette's words, along with those of a few others, have migrated from one of my notebooks to another for over twenty years now. It's a wisdom I need to remember -- wisdom that is so easy to forget."

Of course, waiting for a new idea to take shape is not an excuse for avoiding the studio altogether.

"The advice I like to give young artists," says painter Chuck Close, "or really anybody who'll listen to me, is not to wait around for inspiration. Inspiration is for amateurs; the rest of us just show up and get to work. If you wait around for the clouds to part and a bolt of lightning to strike you in the brain, you are not going to make an awful lot of work. All the best ideas come out of the process; they come out of the work itself. Things occur to you. If you're sitting around trying to dream up a great art idea, you can sit there a long time before anything happens. But if you just get to work, something will occur to you and something else will occur to you and something else that you reject will push you in another direction. Inspiration is absolutely unnecessary and somehow deceptive. You feel like you need this great idea before you can get down to work, and I find that's almost never the case."

Ann Patchett reminds us that in order to write we need to cross the line between thinking about creating and getting down to work:

"The journey from the head to the hand is perilous and lined with bodies," she warns. "It is the road on which nearly everyone who wants to write -- and many of the people who do write -- get lost.���

If creative anxiety is what prevents you from beginning, Barbara Kingsolver has this advice:

"Close the door. Write with no one looking over your shoulder. Don't try to figure out what other people want to hear from you; figure out what you have to say. It's the one and only thing you have to offer."

Dani Shapiro concurs:

"Remember, as you begin, that you are in a remote and exotic place -- the literary equivalent of far eastern Bhutan. It is a place where no one can find you. Where anything is possible. Where, for a time, you are free, liberated from the ideas and expectations of others. You are trekking, and vistas are infinite. This freedom is necessary whether you are working on your first book or your tenth. In order to create a world on the page, you need to push away from the world around you. You must forget its expectations and constraints."

A new year is beginning. At this moment, it is all potential. The vista is infinite.

Words: The passage by Dani Shapiro is from Still Writing: The Pleasures & Perils of the Creative Life (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2013); the quote by Ann Patchett is from The Getaway Car: A Practical Memoir About Writing & Life (Byliner, 2011); and I recommend both. The Close and Kingsolver quotes have been reprinted so often that I'm afraid I don't know the orignal context of either one. The poem in the picture captions is from Circles on the Water: Selected Poems of Marge Piercy (Alfred A. Knopf, 1982). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The first drawing is by John D. Batten (1860-1932), for The Black Bull of Norroway (a Scottish variant of East of the Sun, West of the Moon). The second and third drawings are by W. Heath Robinson (1872-1944), picturing Gerda's quest in The Snow Queen. Further reading: For more on the subject of creative anxiety, go here and here. On procrastination, go here.

January 2, 2017

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today's music begins with "Porz Goret" by Yann Tiersen, a composer and pianist from Finist��re, Brittany. The piece is from Eusa, a book of ten piano scores based on Tiersen's home island of Ouessant, with field recordings of natural sounds (wind, rain, and the sea) from the places that inspired each piece. "Ouessant is more than just a home," he says, "it���s a part of me. The idea was to make a map of the island and, by extension, a map of who I am."

Below: "Waterfalls" by C��cile Corbel, also from Finist��re, who performs new and traditional songs in Breton, English, and French. This one is from Corbel's new album, Vagabonde (a collaboration with other musicians from Brittany, the British Isles, and beyond), filmed near the harpist's home in the Breton countryside.

Above: "Szerelem," an old Hungarian song performed by the Wild Honey Trio (Peia Luzzi, Megan Danforth and Cyrise Schachter) -- an American vocal group dedicated to gathering, studying, and performing traditional music from around the world. "I think of songs as living on our breath," says Luzzi; "if they are not carried or sung, they are lost."

Below: "Oj ty rzeko" by Laboratorium Pie��ni (Song Labratory), from Poland. This wonderful all-woman polyphonic group performs traditional songs from Poland, Ukraine, the Balkans, Belarus, Georgia, Scandinavia, and father afield. Their work, they say, "is inspired by the sounds of nature, and is often intuitive, wild and feminine."

And to end with: "Walk" by composer and pianist Ludovico Einaudi, from Turin, Italy. Returning to Einaudi's music each January has become something of a ritual for me -- along with cleaning the house on New Year's Day, sweeping out the remains of the last year and welcoming in the new.

Now the sun is rising. The gate stands adjar. Let's see where this new day will lead....

December 23, 2016

The studio is closed for the holidays until Mon...

The studio is closed for the holidays until Monday, January 2nd. My deepest apologies for the lack of new posts recently -- the flu that has swept our household (and half the village) has been both tenacious and severe. But we'll start again fresh in the new year -- and I look forward to resuming our conversations about books, art, folklore, nature, resilience, and living in this world in a good, mythic way. Thank you for being part of our Mythic Arts community, and have a good holiday.

The fairy painting above is by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). The drawing of Tilly as a pup is by David Wyatt. The poem in the picture captions is by Liz Lochhead (Scottish Poetry Library), after John Donne's "A Nocturnal upon St. Lucy���s Day Being the Shortest Day."

The fairy painting above is by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). The drawing of Tilly as a pup is by David Wyatt. The poem in the picture captions is by Liz Lochhead (Scottish Poetry Library), after John Donne's "A Nocturnal upon St. Lucy���s Day Being the Shortest Day."

The studio is closed for the holidays until Monday, Jan...

The studio is closed for the holidays until Monday, January 2nd. My deepest apologies for the lack of new posts recently -- the flu that has swept our household (and half the village) has been both tenacious and severe. But we'll start again fresh in the new year -- and I look forward to resuming our conversations about books, art, folklore, nature, resilience, and living in this world in a good, mythic way. Thank you for being part of our Mythic Arts community, and have a good holiday.

The art above is by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). The poem in the picture captions is by Liz Lochhead (Scottish Poetry Library), after John Donne's "A Nocturnal upon St. Lucy���s Day Being the Shortest Day."

The art above is by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). The poem in the picture captions is by Liz Lochhead (Scottish Poetry Library), after John Donne's "A Nocturnal upon St. Lucy���s Day Being the Shortest Day."

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers