Terri Windling's Blog, page 97

February 21, 2017

Tilly's first protest

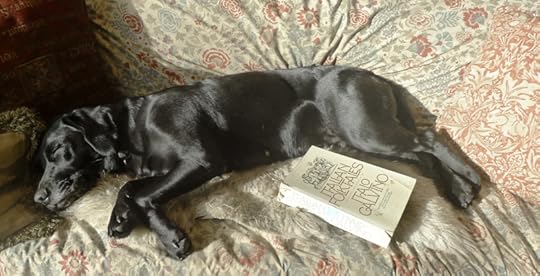

We took the hound with us to the One Day Without Us protest in Exeter, which was not only her first political march, but also her first city experience. The photo of her with Howard above comes from the event's Facebook page -- taken early, while the crowd was still gathering. Tilly looks a little worried in this picture, but she actually enjoyed the city: new sights, new sounds, new smells...and plenty of attention.

It was good to be there, showing solidarity with our European-born neighbors here in Devon. Listening to the stories of the ways their lives are being upending due to Brexit was truly heart-breaking. Thank you to all who support this political action, which is on-going.

The Brecht poem in the picture captions is from Poetry magazine (June, 2011), translated from the German by Adam Kirsch.

The Brecht poem in the picture captions is from Poetry magazine (June, 2011), translated from the German by Adam Kirsch.

February 20, 2017

Myth & Moor update

I am out of the office today in support of One Day Without Us.

As an immigrant myself, I am appalled by the UK government's stance that the rights of EU citizens who have legally made their homes in the UK are "bargaining chips" in the Brexit negotations -- and that these neighbors, co-workers, and family members now live in fear of deportation at some point in future. I'm ashamed that foreign-born residents of UK -- doing every kind of job from teaching, doctoring, nursing and care work to serving your latte at Starbucks -- are now made to feel disposable and unwelcome.

I have had deep immigration problems of my own due to the Orwellian rules imposted by Theresa May's Home Office -- and this with all the privileges of being white, English-speaking, middle class, married to a British citizen, and the mother of a British daughter. Take any or all of those privileges away, and the Home Office is even more brutal.

If you are in the UK, I hope you'll consider supporting "One Day Without Us" by joining your local protest today, and/or writing to your MP to object to the shameful lack of support for EU migrants (and immigrants from the rest of the world) at all levels of our government.

More info: http://www.1daywithoutus.org/

Tilly and I will be back very soon...with the Secret Something I've been working on. Thanks for your patience!

February 6, 2017

Myth & Moor update

I'm away this week, and back again on Monday, February 13. Have a good and creative week, everyone. Keep shining in the darkness.

February 2, 2017

Wild Neighbors

Fridays are now my day for reprinting posts from the Myth & Moor archives. This one first appeared here back in June, 2013....

"What would Robin Hood have made of Country Life's recent excavation into the fantasies of British 7-to-14-year-olds concerning the wild life and wild places of their native land?" asks poet and scholar Ruth Padel. "Two thirds had no idea where acorns come from, most had never heard of gamekeepers (do they  mug people or protect the Pokemons?), and most believed there were elephants and lions running round the English countryside. A third did not know why you had to keep gates shut ��� was it to keep the elephants in (or was some joker taking the piss just then?), or stop cows 'sitting on cars,' upsetting the countryside's most vital beast ��� the traffic?

mug people or protect the Pokemons?), and most believed there were elephants and lions running round the English countryside. A third did not know why you had to keep gates shut ��� was it to keep the elephants in (or was some joker taking the piss just then?), or stop cows 'sitting on cars,' upsetting the countryside's most vital beast ��� the traffic?

"In a closed, traditional society there is something special about animals born in the land where you, too, were born. The British used to look lazily at gardens, thickets, and moors, and know ��� without bothering to think about it ��� that foxes, hedgehogs, badgers, squirrels, and deer were out there flecking the undergrowth....

"Dangerous or vulnerable, shy or cunning, a pest or welcome visitor, our native animals are part of our romance with the secret wildness of the place we live, even if we never see much of them. We grew up with them in imagination. They were inside us, furry heroes of nursery rhymes, pictures and stories through which we learned the world. Little Grey Rabbit. The Stoats and Weasels of the Wild Wood. The Fox who Looked Out on a Moonlight Night. The Frog who would A Wooing Go. They are deep in British folk song, poetry, and popular art. 'Three Ravens Sat in an Old Oak Tree.' The holly and the ivy, the running of the deer. Landseer's 'Monarch of the Glen.'

"But that's the way it used to be. We are not a mono���traditional society any more ��� most kids' traditions center on the TV and the city street. To most children, a weasel is as unknowable as daffodils to a young Indian struggling with Wordsworth during the Raj."

How did we become so disconnected to the land we live on, and the wild neighbors we share it with? I think it's partly because we're losing the stories specific to the local landscape: the stories about this plant that grows on the hill nearby and that bird that migrates here each spring and not just the pan-cultural stories we share with everyone on the television and cinema screens. We no longer know the tales of the animals, and, increasingly, we no longer know animals themselves.

What a different attitude is conveyed by these words from a member of the Carrier Indian nation in British Columbia (quoted in Becoming Animal by David Abram):

"We know what the animals do, what are the needs of the beaver, the bear, the salmon, and other creatures, because long ago men married them and acquired this knowledge from their animal wives. Today the priests say we lie, but we know better. The white man has only been a short time in this country and knows very little about the animals; we have lived here thousands of years and were taught long ago by the animals themselves. The white man writes everything down in a book so it will not be forgotten; but our ancestors married animals, learned their ways, and passed on this knowledge from one generation to another."

The old story of a woman who marries a bear, for example, is one that used to roam widely, like the bears themselves, throughout North America. In a Nishga version recounted by Agnes Haldane of the Wolf clan of Gitkateen (in Wisdom of the Myth Tellers by Sean Kane), a tribal princess picking berries in the forest steps on a bit of bear scat and mutters angry remarks about the bears. As the women head for home, her basket breaks; repairing it, she is left behind. Two handsome men appear and tell her they've come to fetch her and lead her from the forest. Instead of leading her home, they take her to the village of the Bear People. The princess tricks the People into believing she is a woman of great power, and as a result she ends up marrying the son of the Bear Chief. She lives with him rather happily, and gives birth to two fine bear sons. But during a period of hibernation, her own brothers find her husband's cave and kill the bear in a rescue attempt. Her husband has foreseen this event. "When they skin me," he'd instructed her, "tell them to burn my bones so that I may go on to help my children. At my death they shall take human form and become skillful hunters. Now listen as I sing my dirge song. This you must remember and take to your father. My cloak he shall don as his dancing garment. His crest shall be the Prince of Bears."

The bear's sacrifice of his life for the benefit of human beings might seem suprising, but it's not an unusual theme in the indiginous tales of North America, where many story traditions say the animals were the First People, here before humans came. Sacred tales from many different Indian nations recount how Bear, or Coyote, or Eagle, or Deer first gave humans the precious, vital gift of fire; while in other tales language, hunting skills, dancing, even love-making, were first taught by animals. Though we've come to expect such respectfulness towards and from other species in American Indian lore, it can also be found in many other storytelling traditions around world -- such as in the sacred stories of the Ainu of Japan. As Gary Snyder notes (in The Practice of the Wild):

"In the Ainu world, a few human houses are in a valley by a little river. Food is often foraged in the local area, but some of the creatures come down from the inner mountains and up from the deeps of the sea. The animal or fish (or plant) that allows itself to be killed or gathered, and then enters the house to be consumed, is called a 'visitor,' marapto. Bear sends his friends the deer down to visit humans. Orca [the Killer Whale] sends his friends the salmon up the streams. When they arrive their 'armor is broken' -- they are killed -- enabling them to shake off their fur or scale coats and step out as invisible spirit beings. They are then delighted by witnessing the human entertainments -- sake and music. (They love music.) Having enjoyed their visit, they return to the deep sea or the inner mountains and report, 'We had a wonderful time with the human beings.' The others are then prompted themselves to go on visits. Thus if the humans do not neglect proper hospitality, the beings will be reborn and return over and over."

In another essay in the same volume, Snyder writes: "A young white woman asked me: 'If we have made such good use of animals, eating them, singing about them, drawing them, riding them, and dreaming about them, what do they get back from us?' An excellent question, directly on the point of etiquette and propriety, and putting it from the animals' side. The Ainu say that the deer, salmon, and bear like our music and are fascinated by our languages. So we sing to the fish or the game, speak words to them, say grace. Periodically we dance for them. A song for your supper: performance is currency in the deep world's gift economy. The other creatures probably do find us a bit frivolous: we keep changing our outfits and we eat too many different things. Nonhuman nature, I can't help feeling, is well inclined towards humanity and only wishes that modern people were more reciprocal, not so bloody."

The idea that animals love human song reminds me of this passage from Linda Hogan's gorgeous novel Power:

'[T]he panther remembers when humans were so beautiful and whole that her own people envied them and wanted to be like them. They admired the humans and the way the two-legged people stood beneath trees with leaves leaning down over them as they picked ripe fruits, how their beautiful eyes were fully open. How straight they walked! How beautiful the beads about their necks, the dresses women made in fabric that was the dark green of the trees and the light colors of flowers. How intelligent the little shell and wooden bowls they ate from, how good they were at devising ways to catch fish with simple bone and metal, at making trails through the thickets. They stood so gracefully and full of themselves, they sang so beautifully; it remembers all this, how they sang. The whole world rejoiced with their voices....

"[The panther] remembers when its own people surrounded the humans and gave them life and power, medicine to heal, to hunt, even to direct lightning and stormclouds away from their beautiful dark-eyed children....But now they have turned against her. Now that they have no need for her, Sisa and her people, the panther, are leaving. They leave in sadness and grief. Now so few of the humans have songs or presence, so many have such heaviness that they can barely walk or move, raise themselves from their beds in the morning. And Sisa believes, sees, that the world could end with their human misery."

And in Wild: An Elemental Journey (another book that I highly recommended), Jay Griffiths shares this:

"Creatures are gente, I'm told, everywhere I go in the Amazon: they are 'people like us' with customs and homes and they are accorded gentleness for being gente. You must address the world gently, I was told, even to the wind you should speak con cari��o -- with tenderness. The Harakmbut say that all animals were people m��s all�� -- long ago -- and there is therefore a profound equality between us and them; they are like distant family, and one has duties and expectations as one would with family members. People are 'familiar' with the habits and ways of animals, and this familarity is cherished. (By contrast in the West, close familiarity with animals was considered devilish: the witch and her 'familiar.')

"Animals should be treated kindly, even in hunting, for they are kin to humans. 'We owe...kindliness to other creatures: there is an intercourse and mutual obligation between them and us,' wrote Michael de Montaigne, sounding uncannily like an Amazonian Indian."

"Homo sapiens," wrote the late naturalist Ellen Meloy (in Eating Stone: Imagination and the Loss of the Wild) "have left themselves few scant places and scant ways to witness other species in their own world, an estangement that leaves us hungry and lonely. In this famished state, it is no wonder that when we do finally encounter wild animals, we are quite surprised by the sheer truth of them."

Louise Erdrich portrays this sense of surprise in a passage from her novel The Painted Drum:

���Coming down off the trail, I am lost in my own thoughts and unprepared when a bear chugs across the path just before it gives out on the gravel road. I am so distracted that I keep walking towards the bear. I only stop when it rears, stands on hind legs, and stares at me, sensitive nose pressed into the air, weak eyes searching. I have never been this close to a wild bear before, but I am not frightened. There is no menace in its stance; it is not even curious. The bear seems to know who or what I am. The bear is not impressed. ���

No, I don't expert that the bear would be impressed with many of us these days, nor the bees and badgers, the hares and hedgehogs and other wild folk here in the hills of Devon. We don't know their stories any longer. We've forgotten their songs. We don't "stand with presence."

No, I don't expert that the bear would be impressed with many of us these days, nor the bees and badgers, the hares and hedgehogs and other wild folk here in the hills of Devon. We don't know their stories any longer. We've forgotten their songs. We don't "stand with presence."

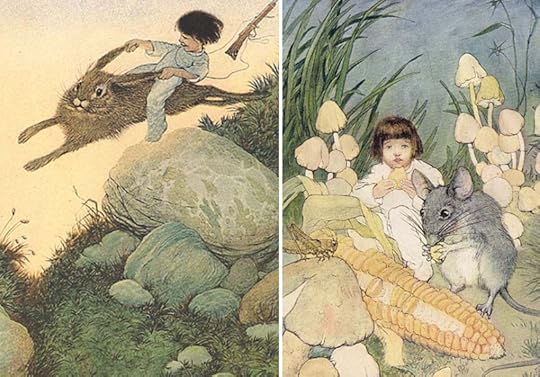

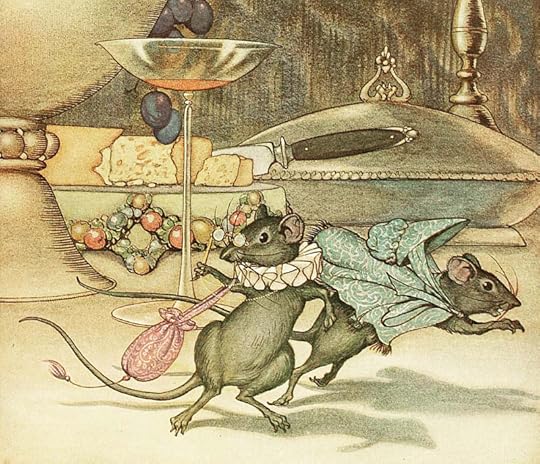

In From the Beast to the Blonde, Marina Warner discusses the role of "beasts" in fairy tales, and how our perceptions of these stories have changed as attitudes towards animals have changed. "Just as the rise of the teddy bear matches the decline of real bears in the wild," she notes, "so soft toys today have taken the shape of rare animal species. Some of these are not very furry in their natural state: stuffed killer whales, cheetahs, gorillas, snails, spiders and snakes -- and of course dinosaurs -- are made in the most inviting deep-pile plush. They act as a kind of totem, associating the human being with the animal's capacities and value. Anthropomorphism traduces the creatures themselves; their loveableness sentimentally exaggerated, just as formerly, belief in their viciousness crowded out empircal observation."

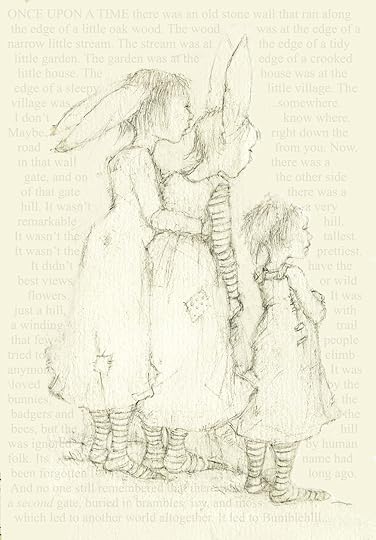

This is clearly true, and a world in which children interact only with animal-shape-objects while remaining ignorant about the creatures outside their own back door (be it country badger or urban fox) is clearly a world out of balance. And yet, for me, those soft animal toys awakened my interest in and life-long love of the wild, as did the anthropomorphised animals of tales like Peter Rabbit, Winnie the Pooh, and Wind and Willows. I'm thinking quite a lot about this these days, as I work on a book project involving bunny girls and other animal children. I want these magical beings to lead children back to nature, not to be nature's safe, cuddly substitute. Is this possible? At this point in the process, I have more questions than I have answers....

When I think back to my own childhood, what I wish is that someone had noted my passion for animals and placed a wildlife guide in my hands alongside those tales of Mole and Rat and Benjamin Bunny...or better still, led me out of doors and into the wild, and told tales of the land we then lived on. Not in place of those books, which had done their work in opening the door into wonder for me, but as the next necessary step of attaching wonder to the living world around us.

"How, then to renew our viceral experience of a world that exceeds us -- of a world that is wider than ourselves and our own creations?" asks David Abram (in Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology). "Does a revitalizing of oral [storytelling] culture mean that mean that we must renounce reading and writing? Must we empty our bookcases? Must we unplug our computers and drag them down to the dump?

"Hardly. The renewal of oral culture entails no renunciation of books, and no rejection of technology. It entails only that we leave abundant space in our days for interchange with one another and with our surroundings that is not mediated by technology: neither by television nor the cell phone, neither by the handheld computer or the GPS satellite...nor even the printed page.

"Among writers, for example, it entails a recognition (even an anticipation) that there are certain stories we may stumble against that ought not to be written down -- stories that we might instead begin to tell with our tongue in the particular topography where those stories live. Among parents, it requires that we set aside, now and then, the books that we read to our children in order to recount a vital story with the whole of our gesturing body -- or better yet, that we draw our kids out of doors in order to improvise a tale about how the nearby river feels when the fish return to its waters, or about the wild wind that's even now blustering its way through the city streets, plucking the hats off people's heads.... Among educators, it requires that we begin to rejuvenate the arts of telling, and of listening, in relation to the geographical place where our lessons actually happen."

"Can we renew in ourselves an implicit sense of the land's meaning, of its own many-voice eloquence?" David wonders. "Not without renewing the sensory craft of listening, and the sensuous art of storytelling. Can we help our students to carefully translate the quantified abstractions of science into the qualitative language of direct experience, so that those necessary insights begin to come alive in their felt encounters with cumulus clouds and bleaching corals, with owls and deformed dragonflies and the intricate tangle of mycelial mats? ...Most important, can we begin to restore the health and integrity of the local earth? Not without restorying the local earth."

"We are of the animal world," Linda Hogan reminds us (in her beautiful collection of essays, Dwelling: A Spiritual History of the Living World). "We are part of the cycles of growth and decay. Even having tried so hard to see ourselves apart, and so often without a love for even our own biology, we are in relationship with the rest of the planet, and that connectedness tells us we must reconsider the way we see ourselves and the rest of nature.

"A change is required of us, a healing of the betrayed trust between humans and earth. Caretaking is the utmost spiritual and physical responsibility of our time, and perhaps that stewardship is finally our place in the web of life, our work, our solution to the mystery of what we are."

Indeed. Part of that stewardship, surely, is caretaking our local, traditional stories as well as the land that gave birth to them. And listening for the land's new stories. Telling them. And singing, so the animals can hear us.

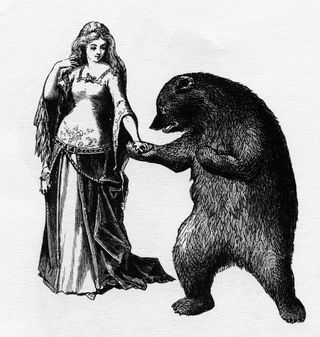

The photographs above, of our four-footed and winged neighbors here in Devon, come from the Devon Wildlife Trust website. The art above: "Ratty" by my two-footed neighbor Steve Dooley (from the enchanting new Wind and the Willows for iPad); "Woman & Bear," a Victorian illustration (artist unknown); Peter Rabbit by the great Beatrix Potter; and my wee Rabbit Sisters.

Running with the wolves

To carry on with yesterday's discussion...

Of all wild stories, the ones involving wolves seem somehow the wildest, for the wolf is an animal who carries our love and fear of wilderness in equal measure. A wide range of wolf mythology can be found around the world wherever wolves have roamed: in some tales they are depicted as culture heroes and loyal companions to the gods; in others they are devilish, destructive figures, enemies of the gods and humankind alike, agents of primal chaos.

"The tradition of the wolf as warrior-hero is older than recorded history," writes Barry Lopez in his magnificent book Of Men and Wolves. "The legend of Romulus and Remus and other wolf children point up another ancient image, that of the benevolent wolf-mother. The deaths of those taken for werewolves and burned alive in the Middle Ages represent yet another, focusing negative feelings about the wolf.

"I have written about the wolf as a symbol of twilight; other writers have suggested, and I agree with them, that the wolf is a symbol reflecting two human alternatives at war: instinctual urges and rational behavior. In Hesitant Wolf and Scrupulous Fox, Karen Kennerly says the wolf is the creature who is most like us in fable. 'Out of phase with himself,' she says, 'he is defeated alternately by hubris and naivete. He becomes the irreconcilability between instinct and rational thought.' His attempts to live a rational life is defeated by his urge to behave basely. Thus, the human and bestial natures. The central conflict between man's good and evil natures is revealed in his twin images of the wolf as a ravening killer and as nurturing mother. The former was the werewolf; the latter the mother to children, like Romulus and Remus, who found nations."

The wolves of myth, of course, are human creations, and have little to do with the actual lives of wolves living in the wild -- a subject that has been studied extensively by scientists of many different stripes in modern times, and about which there is much we still don't know, or fully understand. Wolf packs are complex, sophisticated systems -- and it seems that every time wolf scholars assert theories about precisely how they work, new data arises to shatter those theories. In a world where we like to map and track and pin knowledge down into cold, hard facts, the wolves elude us, slipping back into dark, starless night of mystery.

This makes them irresistible creatures for writers of "wild stories," and the howling of wolves can be found in many good (and not-so-good) works of fantasy fiction.

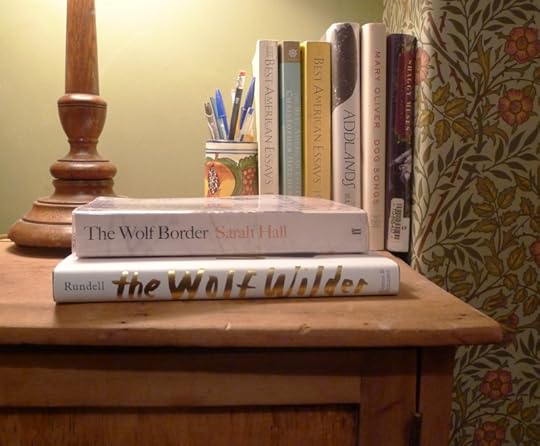

One of my favorite wolf stories is a recent one, The Wolf Wilder by Katherine Rundell. It's an absolutely splendid novel, which I'll let the author describe herself:

"The Wolf Wilder," says Rundell, "is a fairy tale of sorts; in it, two children ride wolves across Russia in the snow. Much of fiction writing involves finding new ways to talk about old desires, and mine is a litany of all the things I dreamt of as a child: snow, knife, skis, wolf, boy. My source-text was the glorious Russian fairy tale, The Tale of Ivan Tsarevich, the Firebird and the Grey Wolf. In it Ivan Tsarevich, the son of a Tsar, is sent to catch a firebird that is eating his father's apples. He comes to a crossroads where a choice is set out: 'Whoever goes to the right shall die. Whoever goes along the  middle way will have his horse devoured by the grey wolf.' Ivan takes the middle road and, in the blunt diction of fairy tales, the grey wolf does indeed eat his horse, then suggests that Ivan ride on his own back to glory, instead.

middle way will have his horse devoured by the grey wolf.' Ivan takes the middle road and, in the blunt diction of fairy tales, the grey wolf does indeed eat his horse, then suggests that Ivan ride on his own back to glory, instead.

"What I remember most clearly is one line. 'The grey wolf said, 'Get on my back and hang on tightly': and the wolf carried him off 'just as if he were on a swan's back.' That line reverberates with desire, both childlike and adult. It captures the doubleness of innocence and experience in fairy tales -- as Carol Ann Duffy writes in her poem 'Little Red Cap': What little girl doesn't dearly love a wolf?

"Shape-shifting wolves have always had cultural bite. The very first transformation scene in Ovid is also one of the earliest fictional accounts of lycanthropy, and was always the story in the Metamorphoses that I, as an unpleasant child, loved most. King Lycaon murders a hostage sent from Epirus, cooks his limbs 'still warm with life, boiling some and roasting others over the fire,' and serves it to Zeus as a feast that doubles as a taunt. In vengeance, Zeus strikes his palace with lightning and sends Lycaon out into the wild. 'There he uttered howling noises, and his attempts to speak were in vain. His clothes changed into bristling hairs, his arms to legs, and he became a wolf. His own savage nature showed in his rabid jaws.' Transformation, in Ovid, is a kind of truth-telling.

"Wolves offer a straightforward kind of truth, too," Rundell continues. "In Charles Perrault's 1697 version of Little Red Riding Hood; girls who get into bed with strange men don't survive. The wolf, for Perrault, is an entirely unsubtle stand-in for human lust. Angela Carter took Perrault's stories and inverted them; the result was The Bloody Chamber. Carter's world transforms the tradition of captured, passive girls; instead, it is delicious and dangerous: all dirt and diamonds, dust on mirrors, girls with architectural cheekbones and red cloaks. The young women in her tales are their own fairy godmothers. Her Red Riding Hood, faced with a wolf in the bed, 'burst out laughing; she knew she was nobody's meat.' Elsewhere, Carter wrote: "I really do believe that a fiction absolutely self-conscious of itself as a different form of human experience than reality (that is, not a logbook of events) can help to transform reality itself. 'Fairy tales remind us that we are so very hungry; the human appetite for other humans is insatiable, and Carter embraces hunger. A little bit of something wild does you good.' "

(I recommend reading Rundell's article, "The Greatest Literary Wolves," in full.)

My other favorite wolf story of recent years is Sarah Hall's finely-crafted novel The Wolf Border, about the re-introduction of wolves on a vast estate on the border of Cumbria and Scotland. This is a contemporary, largely Realist story with one slight fantasy element: in Hall's fictional world, the Scottish Referendum of 2014 has ended with Scottish independence. I admit that it took me a while to warm to the novel's protogonist, zoologist Rachael Caine, a damaged and damaging character -- but that, it turns out, is the point of the book. Rachael's emotional journey, paired with the saga of her wolves, is beautifully rendered, and I loved this book without reservation by the last page and journey's end.

Unlike the wolves of fantasy, Hall's wolves are never more or less than animals, fulfilling naturalist Henry Beston's vision that "the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours, they move finished and complete, gifted with the extension of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings: they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth."

This is not to disparage the wolves of fantasy literature, whose stories satisfy in a wholly different way: they are metaphorical tales exploring our relationship with the wild (for good or ill), and they work on us the way myths and fairy tales work on us: indirectly, symbolically, poetically, and below the level of conscious thought.

"Fantasy," explains Ursula Le Guin, "is a different approach to reality, an alternative technique for apprehending and coping with existence. It is not antirational, but pararational; not realistic but surrealistic, a heightening of reality. In Freud's terminology, it employs primary, not secondary process thinking. It employs archetypes, which, as Jung warned us, are dangerous things. Fantasy is nearer to poetry, to mysticism, and to insanity than naturalistic fiction is. It is a wilderness, and those who go there should not feel too safe....It is a journey into the subconscious mind, just as psychoanalysis is. Like pyschoanalysis, it can be dangerous; and it will change you."

The best wolves in fantasy are the ones that haunt your dreams when the book is done: Nighteyes in the Farseer books of Robin Hobb; the feral wizard-wolf at the heart of The Book of Atrix Wolfe by Patricia A. McKillp; the motorcycle-riding shapeshifters in The Evil Wizard Smallbone by Delia Sherman; the wild wolf-raised heroine of The Firekeeper Saga by Jane Lindskold; the mysterious Stephen, raised by wolves, in Alice Hoffman's darkly romantic Second Nature; the deliciously sinister Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken; or the frightening yet alluring beasts in Angela Carter's "The Company of Wolves" (and the movie made from it).

A list of good "wolf fantasy" would also surely have to include: Julie of the Wolves by Jean Craighead George (winner of the Newbery Medal); Wolf by Gillian Cross (winner of the Carnegie Medal, based on Little Red Riding Hood); Children of the Wolf by Jane Yolen (based on a real-life "feral children" tale), A Companion to Wolves by Sarah Monette & Elizabeth Bear; and The Sight by David Clement-Davies (told from a wolf pack's point of view). Please recommend other wolf tales I haven't mentioned here in the Comments.

Barry Lopez points out that benevolent wolves are more common in modern literature than they were in ancient myth and legend:

"I think, somehow, that looking for the wolf-mother [or -father, or steadfast companion] is the stage we are at now in history. If we go back to the time of Lycaon and follow the development of the wolf image through the Dark and Middle Ages to the present, the overriding impression is that of a sinister creature. But [now], whether out of guilt or because we have reached such a level of civilization as to allow us the thought, we are looking for a new wolf. We seem eager to be corrected, to know how wrong our ideas about wolves have been, how complex the creature really is, how ultimately unfathomable. What we are looking for, I think, is a way to return mystery to the animals, and distance and selfhood, and thereby dignity.

"Almost like errant children, we seem to want forgiveness from the wolves. And I think that takes great courage.

"It may be reasonable to expect most people to dismiss the notion of a nurturing wolf as a naive person's referent," Lopez adds, "but that doesn't seem wise to me. When, from the prisons of our cities, we look out to the wilderness, when we reach intellectually for such abstractions as the privilege of leading a life free from nonsensical conventions, or one without guilt or subterfuge -- in short, a life of integrity -- I think we can turn to wolves. We do sense in them courage, stamina, and a straightforwardness of living; we do sense that they are somehow correct in the universe and we are still at odds with it.

"As our sense of sharing the planet with other creatures grows -- and perhaps that is ultimately the goal of natural history -- the deep contemplation of wolves may be seen as part of an attempt to nurture the humbler belief that there is more to the world than mankind."

Perhaps that is the ultimate goal of Mythic Arts as well.

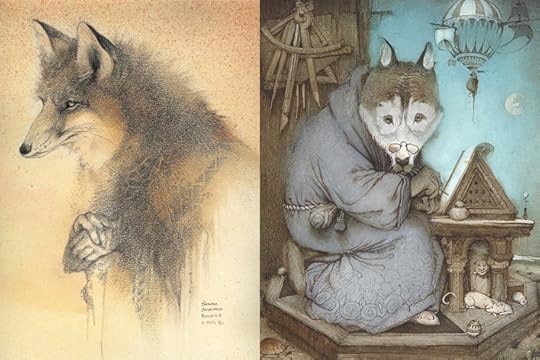

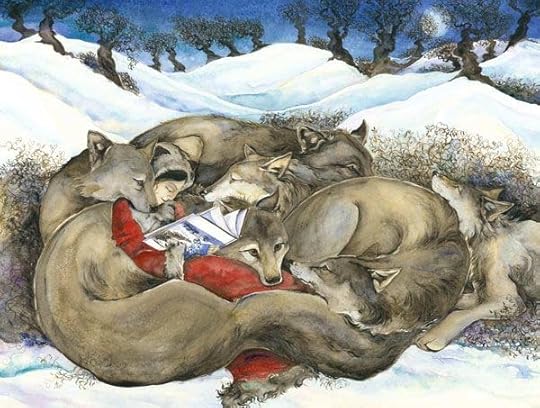

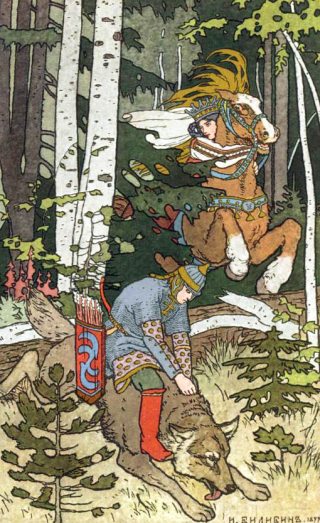

Pictures: The art above is: "Wolf Warrior" by Susan Seddon Boulet, a leaping wolf on gold by Jackie Morris, "Papa Wolf & Tree" by Tricia Cline, "Van Tsarevich Riding the Gray Wolf" by Viktor Vasnetsov, "Ivan & the Wolf" by Ivan Bilibin, "Little Red Riding Hood" by Gustave Dor��, "Little Red Riding Hood "by Adrienne Segur, a grey wolf photographed by Cole Young, "Wolf Thoughts" by Jackie Morris, "Zar" by Igor Oleinikov, "Pope Tricksie & the Wolves" by Tricia Cline, "What to do with all this love?" by Chiara Baustista, "The Dreamcatcher" by Susan Seddon Boulet, "Wolf" by Kirill Chelushkin, "Wolf Bloy" by Danielle Barlow, "Tales of the Firebird" by Gennady Spirin, bedside reading, and "Little Evie in the Wildwood" by Catherin Hyde. Words: The passages by Barry Lopez are from his ground-breaking book Of Wolves and Men (Scribners, 1978); the passage by Katherine Rundell is from her article "The Greatest Literary Wolves" (The Telegraph, September 2015). Both are recommended. All rights to the art and text above are reserved by the artists and authors.

Pictures: The art above is: "Wolf Warrior" by Susan Seddon Boulet, a leaping wolf on gold by Jackie Morris, "Papa Wolf & Tree" by Tricia Cline, "Van Tsarevich Riding the Gray Wolf" by Viktor Vasnetsov, "Ivan & the Wolf" by Ivan Bilibin, "Little Red Riding Hood" by Gustave Dor��, "Little Red Riding Hood "by Adrienne Segur, a grey wolf photographed by Cole Young, "Wolf Thoughts" by Jackie Morris, "Zar" by Igor Oleinikov, "Pope Tricksie & the Wolves" by Tricia Cline, "What to do with all this love?" by Chiara Baustista, "The Dreamcatcher" by Susan Seddon Boulet, "Wolf" by Kirill Chelushkin, "Wolf Bloy" by Danielle Barlow, "Tales of the Firebird" by Gennady Spirin, bedside reading, and "Little Evie in the Wildwood" by Catherin Hyde. Words: The passages by Barry Lopez are from his ground-breaking book Of Wolves and Men (Scribners, 1978); the passage by Katherine Rundell is from her article "The Greatest Literary Wolves" (The Telegraph, September 2015). Both are recommended. All rights to the art and text above are reserved by the artists and authors.

February 1, 2017

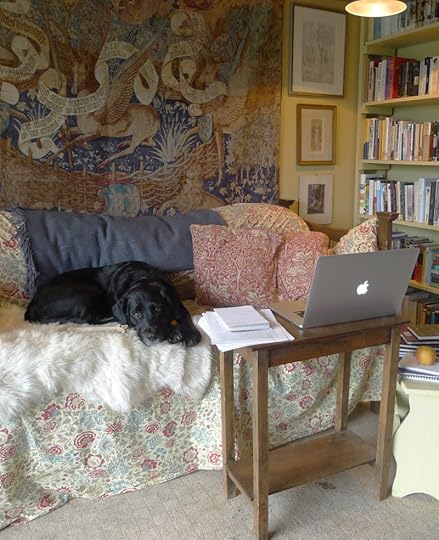

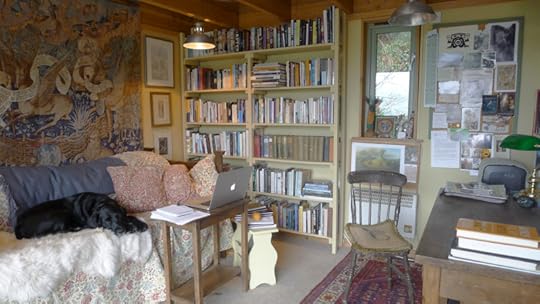

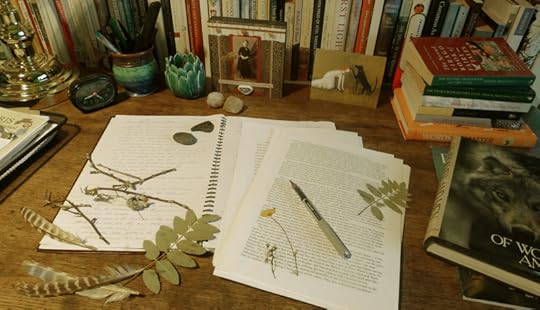

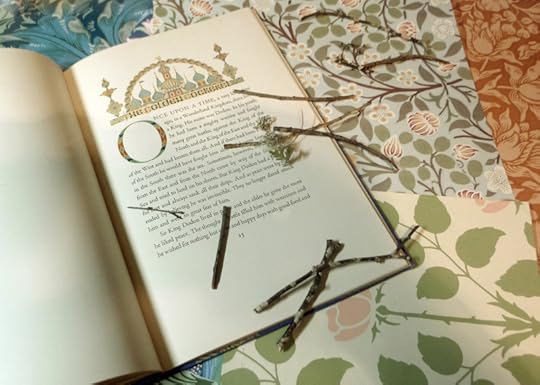

Wild stories

While the world of human affairs goes on its noisy way, I return again and again to the woods and hills behind my studio. To moss. To mud. To the dark, damp mulch of leaves carpeting the forest floor. To the strength of granite and the swift ways of water. To the prickly beauty of holly and gorse. To the patience of seed and bulb and skeletal trees...all waiting, like me, for the spring.

I keep leaving my desk, Tilly close at my heels, crossing from the imaginary landscapes of writing or reading to a world I can touch, and smell, and taste: to the old stone wall at the edge of the treeline, and pathways trodden through bracken by ponies and sheep. To streams filled with rain, bogs thick with mud, fields that glitter with morning frost. To the cold winter wind. To discomfort. To pain. To joy. To the things that are real.

An occupational hazard for the solitary writer is to live in the realm of the mind alone (or the shadowlands of the Internet), and not in the body, the senses, the wild rhythms of the local groundscape we each inhabit, whether rural or urban. For many of us in the fantasy field, the wild world is the very place that we seek to conjure and enter through stories and paintings -- and so we must not neglect our relationship with the elemental wild around us. In our kind of work, "magic" is not a metaphor for gaining power, control, or authority, but for our numinous connection with natural world, and our nonhuman neighhbors. It is wild work. It is soul work. And we need wild stories right now, more than ever.

"I have a sense," writes Kate Bernheimer (author & editor of The Fairy Tale Review) "that a proliferation of magical stories, especially fairy tales, is correlated to a growing human awareness of separation from the wild and natural world. In fairy tales, the human and animal worlds are equal and mutually dependent. The violence, suffering, and beauty are shared. Those drawn to fairy tales, perhaps, wish for a world that 'might live forever.' My work as a preservationist of fairy tales is entwined with all kinds of extinction."

"Writing," says Sylvia Linsteadt, "is my way into the heart of the world -- its wildness, its strange magic, its beauty, its terrors, its sadness, its joy. Metaphor (a favorite of mine) is an act of shape-shifting, of remembering that each thing is hitched to the next in the great cyclical transformation of energy, from sun to seed to doe to cougar and back to worm; the line between ourselves and the wild world is thin indeed. Writing (thick with metaphor) is the means through which I can praise the wild mystery of this world, and also explore its unseen realms -- the realms inside the hearts of bears and granite stones and buckeye trees; the lands just the other side of the moon and the fog, the lives of men and women long ago or just around the corner. If I were buckeye tree, then writing would be the buckeyes that fruit at the ends of my limbs come late August. In other words, writing is the thing made in me from all the waters and winds and soils and stories that come through my five senses (or six), and it feels very inevitable, like the buckeyes at the end of summer.

"Also, I have always been an avid reader," Sylvia continues; "especially as a child I devoured books that told of magical worlds and lands, lady-knights and healers, the everyday peasant life of Old Europe (especially Scotland & Ireland), talking animals, caravans of camel nomads, druids, long adventures on horseback. Such books literally shaped and changed my life. They informed the way I see the world today -- as a place much more mysterious and full of wild magics than we tend to believe, where everything is alive and everything speaks. So I write because writing is even better than reading in the sense that you really get to go to those places in your imagination, and give them to other people. The stories we tell ourselves and each other form the world in which we live."

Our task, as David Abram sees is, "is that of taking up the written word, with all its potency, and patiently, carefully, writing language back into the land. Our craft is that of releasing the budded, earthly intelligence of our words, freeing them to respond to the speech of things themselves -- the the green uttering-forth of leaves from the spring branches. It is the practice of spinning stories that have a rhythm and lilt of the local soundscape, tales for the tongue, tales that want to be told, again and again, sliding off the digital screen and slipping off the lettered page to inhabit the coastal forests, those desert canyons, those whispering grasslands and valley and swamps."

"Storytellers ought not to be too tame," Ben Okri agrees. "They ought to be wild creatures who function adequately in society. They are best in disguise. If they lose all their wildness, they cannot give us the truest joys."

Jay Griffiths adds: "What is wild cannot be bought or sold, borrowed or copied. It is. Unmistakeable, unforgettable, unshamable, elemental as earth and ice, water, fire and air, a quitessence, pure spirit, resolving into no contituents. Don't waste your wildness: it is precious and necessary."

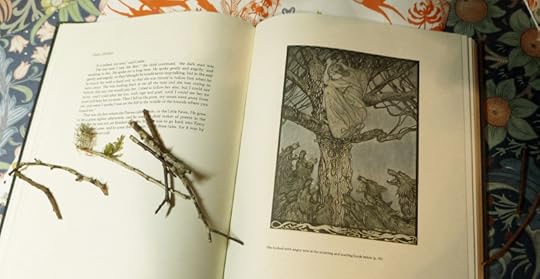

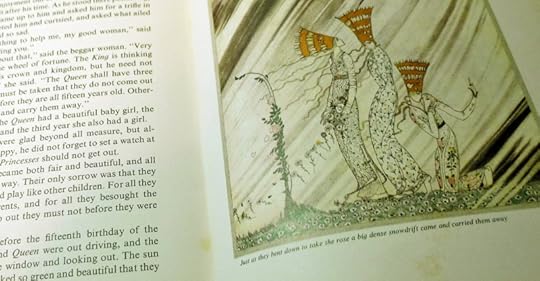

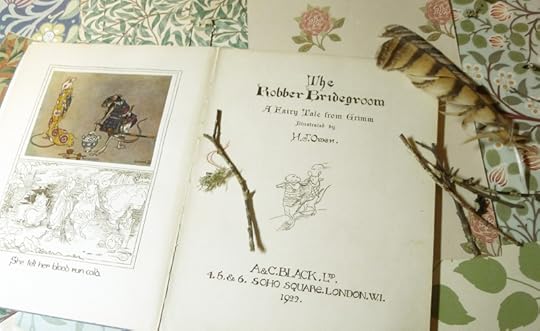

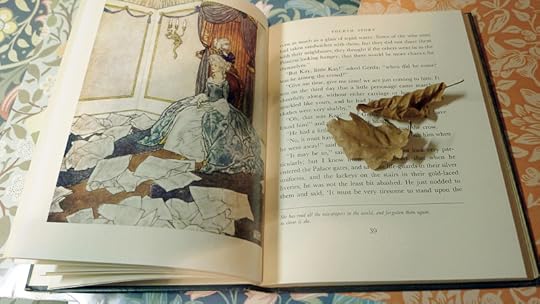

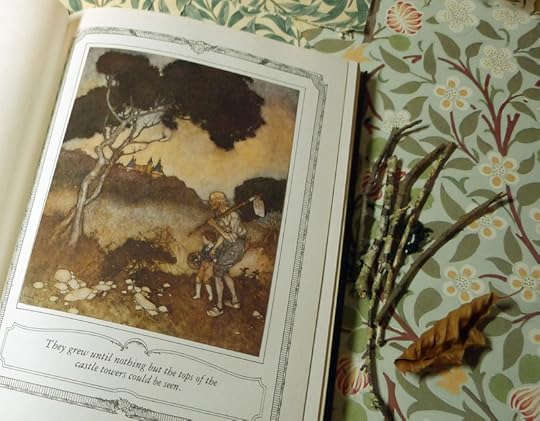

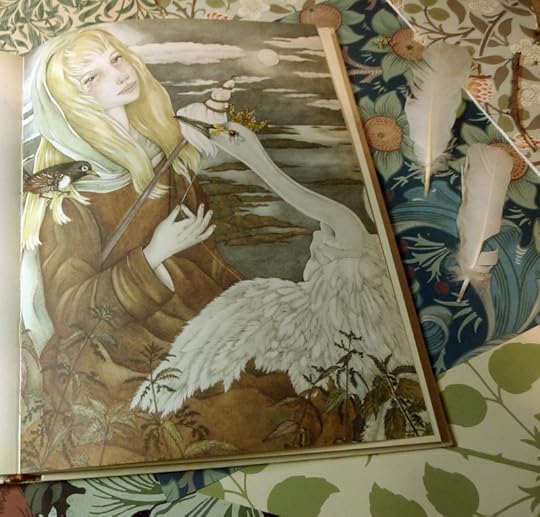

Words: The passage by Sylvia Linsteadt is from an interview by Asia Sular (Woolgathering & Wildcrafting, Sept. 2014), which I recommend reading in full. Kate Bernheimer's quote is from the Introduction to her anthology My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me: Forty New Fairy Tales (Penguin, 2010); Ben Okri's quote is from his essay collection A Way of Being Free (W&N, 1997); Jay Griffith's quote is from Wild: An Elemental Journey (Penguin, 2007). All three books are recommded. All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: My quiet hillside studio on rainy day -- with the hound, works-in-progress, old fairy tale books, and bits of the wild slipping in from the woods.

Words: The passage by Sylvia Linsteadt is from an interview by Asia Sular (Woolgathering & Wildcrafting, Sept. 2014), which I recommend reading in full. Kate Bernheimer's quote is from the Introduction to her anthology My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me: Forty New Fairy Tales (Penguin, 2010); Ben Okri's quote is from his essay collection A Way of Being Free (W&N, 1997); Jay Griffith's quote is from Wild: An Elemental Journey (Penguin, 2007). All three books are recommded. All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: My quiet hillside studio on rainy day -- with the hound, works-in-progress, old fairy tale books, and bits of the wild slipping in from the woods.

January 31, 2017

Animal Medicine

Come into Animal Presence

by Denise Levertov

Come into animal presence.

No man is so guileless as

the serpent. The lonely white

rabbit on the roof is a star

twitching its ears at the rain.

The llama intricately

folding its hind legs to be seated

not disdains but mildly

disregards human approval.

What joy when the insouciant

armadillo glances at us and doesn't

quicken his trotting

across the track into the palm brush.

What is this joy? That no animal

falters, but knows what it must do?

That the snake has no blemish,

that the rabbit inspects his strange surroundings

in white star-silence? The llama

rests in dignity, the armadillo

has some intention to pursue in the palm-forest.

Those who were sacred have remained so,

holiness does not dissolve, it is a presence

of bronze, only the sight that saw it

faltered and turned from it.

An old joy returns in holy presence.

The art today is by American ceramicist Caroline Douglas, who received a BFA from the University of North Carolina and has worked in clay for over forty years, inspired by mythology, fairy tales, dreams and the antics of animals and children. Since sustaining a serious injury in 2000, Douglas has been exploring the relationship between healing and creativity in her dual roles as artist and teacher:

"Our imaginations are sacred," she explains. "At the deepest level, they can put us in touch with the collective unconscious that we all share. I create in clay a version of my intentions and dreams. Making something real in physical form makes it real on many levels. In my classes we travel a journey of transformation and exploration through art to find a deeper place, a more fulfilling place -- that place where stillness reigns and time stretches out and magic has its way with us. It is an alchemy of sorts, a turning of lead into gold. "

Please visit the artist's website or Facebook page to see more of her deeply magical work.

The poem by Denise Levertov (1923-1997) is from Poems 1960-1967 (New Directions, 1983). All rights to the art and text in this post are reserved by the artist and the author's estate.

The poem by Denise Levertov (1923-1997) is from Poems 1960-1967 (New Directions, 1983). All rights to the art and text in this post are reserved by the artist and the author's estate.

January 29, 2017

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today, three singers of Portuguese fado: a genre of songs expressing feelings of love and saudade (or longing)...often sad, and thus called "the Portuguese blues."

Above: "Gente Da Minha Terra (People of My Land)" by Mariza (Marisa dos Reis Nunes), performed in 2013. Born in Portuguese Mozambique and raised in Lisbon, she is widely regarded as the leading singer of the New Fado movement.

Below: A beautifully simple version of "Melhor de Mim." It comes from Mariza's most recent album, Mundo (2015) -- which is terrific.

Above: "O Pastor," performed in 2010 by Teresa Salgueiro, from Lisbon. Salgueiro first recorded this song with the Portuguese music ensemble Madredeus. (She was their lead singer until 2007.) If you're unfamiliar with the group, I recommend their compilation album Antologia, which is utterly gorgeous.

Below: "Meu Amor de Longe" by Raquel Tavares, who is also from Lisbon. Fado songs tend to emphasize personal stories of love, longing, and other emotional themes -- but they're not all sad, as this song shows. It comes from Tavares' most recent album, Raquel (2016).

The art today is by Paula Rego, who was born and raised in Portugal and now lives in London. Rego's work often incorporates imagery from Portuguese folklore, fairy tales, nursery rhymes, children's literature and women's history. "We interpret the world through stories," she says. "Everybody makes, in their own way, sense of things; but if you have stories it helps."

(Rego is also a close friend of fairy tale scholar Marina Warner, whose project on refugee stories seems more vital than ever right now.)

If you'd like a little more fado this morning, try this previous post from 2014.

January 26, 2017

In the Forest of Stories

Fridays are now my day for reprinting posts from the Myth & Moor's archives. This one, from summer 2013, relates to our discussions this week on fairy forests and the power of stories....

"At the beginning of my life was a forest," says Francis Spufford (in his charming memoir, The Child That Books Built). He means an actual forest (an 18th century park, turned wild, close to his parents' house), but also the metaphorical forest at the beginning of fiction, a forest made of stories:

"This one spread forever. Its canopy of branches covered the land, covered every form of the land, whether the ground beneath jagged or rolled. The forest went on. Up in its living roof birds flitted through greeness and bright air, but down between the trunks of the many trees there were shadows, there was dark. When you walked this forest, your feet made rustling sounds, but the noises you made yourself were not the only noises, oh no. Twigs snapped; breezes brought snatches of what might be voices. Lumpings and crashings in the undergrowth marked the passages of heavy things far off, or suddenly nearby.

"This was a populated wood. All wild creature lived here, dangerous or benign, according to their natures. And all the other travelers you had heard of were in the wood too, at this very moment: kings and knights, youngest sons and third daughters, simpletons and outlaws, a small girl whose bright hood flickered between the pine trees like a scarlet beacon...

"...and a wolf moving on a different vector to intercept her at the cottage, purposefully arrowing through thickets, leaving a track of disturbance behind him as an alpha particle does when it streaks across a cloud chamber....

"These people, these dangers, were not far away, but you would never meet them. The adventures could never intersect, although they shared the forest; although they would be joined in time by more, and still more, wayfarers, the more elaborated beings who came from the more elaborate worlds of privately read story, rather than the primitives of fairy tale. Mole from Wind in the Willows would pelt in hunted panic through a nighttime tract of the forest, whose bare boughs jutted 'like a black reef in some still  southern sea.' Through twisted foliage would creep Wart, in The Sword and the Stone, past pale-eyed predators and baby dragons hissing under the stones, to his first sight of Merlyn swearing at a bucket. But each traveled separately, because it was the nature of the forest that you were alone in it. It was the place in which by definition you had no companions, and no resources except your uncertain self. It was the Wild, were relationship ceases, where connection is suspended."

southern sea.' Through twisted foliage would creep Wart, in The Sword and the Stone, past pale-eyed predators and baby dragons hissing under the stones, to his first sight of Merlyn swearing at a bucket. But each traveled separately, because it was the nature of the forest that you were alone in it. It was the place in which by definition you had no companions, and no resources except your uncertain self. It was the Wild, were relationship ceases, where connection is suspended."

There would be encounters in the forest, Spufford adds, for the solitary nature of a young hero's journey is spiritual and emotional, not literal. "Eventually the state that the whole wood represented [for you, the reader/traveler] would be embodied. One of those rustlings would become a footfall, would become a meeting, and you stepped forward to it as best you could. You could no more avoid the encounters of the wood -- all significant, all in their way tests -- than you could cross it on a neat dependable path. It existed to cause changes, and it had no pattern you could take hold of in the hope of evading change. You never went out the same as you went in."

In the pages of Enchantment Hunters: The Power of Stories in Childhood, the brilliant fairy tale scholar Maria Tatar notes:

"The journey as a master trope for the reading experience becomes evident in our use of the term armchair traveler, as well as in a wide range of velvety reports about the reading experience. 'Most of the time I simply enjoyed the luxurious sensation of being carried away by the words, and felt, in a very physical sense, that I was actually traveling somewhere wonderfully remote, to a place that I hardly dared glimpse on the secret last page of the book,' Alberto Manguel reports in his history of reading. The novelist Katie Roiphe describes a similar sense of kinetic exhileration while reading during recovery from a childhood bout of pneumonia: 'I broke open the books the chased the words. It was a breathless activity like running.'"

But it is deeply paradoxical, Tatar points out, "that a practice involving nothing but sitting still and staring at black marks on a white page is pitched as travel with the added benefit of powerful sensory stimulation. Reading is often said to open up alternate world superior to the one inhabited by the reader, producing an improbable rush of life.

"'From that first moment in the schoolroom at Chatres,' C.S. Lewis recalls in contemplating the role of books in his life, 'my secret imaginative life began to be so important and so distinct from my outer life that I almost have to tell two separate stories.' It was in that imaginative world that the author of The Chronicles of Narnia felt 'stabs of joy' so keen that they rivaled any feelings attending real-life experience."

There is a point for most bookish children when the choice of reading material becomes private and deeply personal; when adult attempts to guide or share the reading journey are no longer always welcome. From the bedside tales of our youngest years we progress to reading with a parent or teacher's help, and then on to reading all by ourselves. Books become our private treasures, solitary journeys into wondrous places that adults (except that magical creature called an Author) would surely not understand...or so we think, as each succesive generation discovers the vast Forest of Stories anew.

And indeed, some adults don't understand. Many children tagged as "bookworms" endure a tedious amount of teasing (or worse) from non-readers, as if a passion for print is odd, effete, perhaps even slightly unsavory. "When I was a boy,"the novelist/playwright/critic Robertson Davies once wrote, "many patronizing adults assured me that there was nothing I liked better than to 'curl up with a book.' I despised them. I have never curled."

"Each time a child opens a book," writes Lois Lowry, "he pushes open the gate that separates him from Elsewhere. It gives him choices. It gives him freedom. Those are magnificent, wonderfully unsafe things."

"Books may be the only true magic," says Alice Hoffman.

And indeed they are true magic.

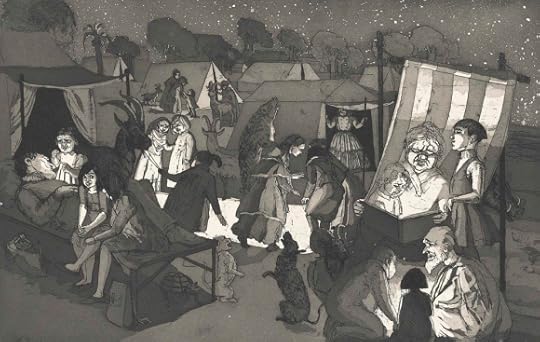

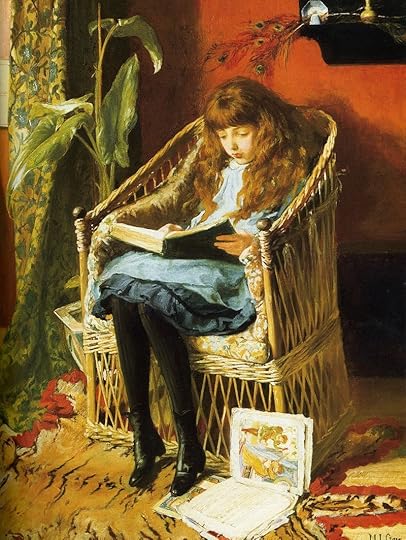

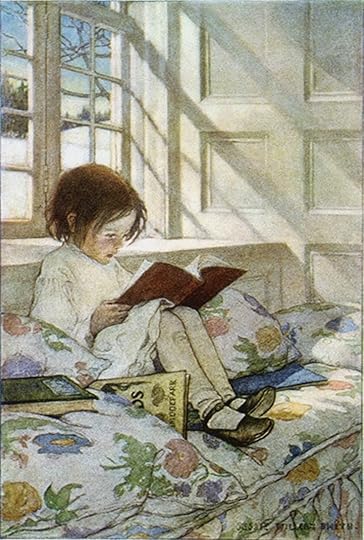

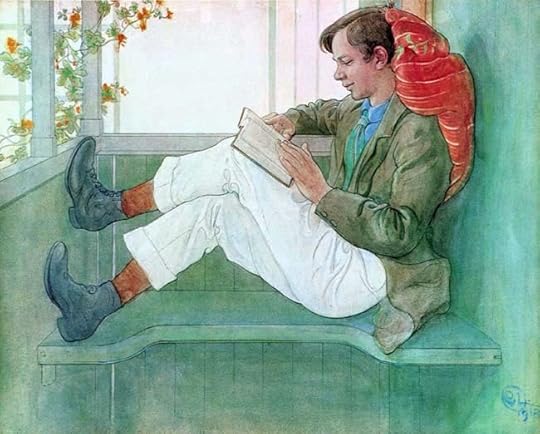

Pictures above: A photograph from Transition Voice magazine; Leshy Forest illustrations by Rima Staines; four book sculptures by Su Blackwell (working with discarded texts); "Mole, Ratty, and Otter" by E.H. Shepard (1879-1976); "Fairy Tales" by Mary L. Gow (1851-1929); "The Fairy Book" by Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935); "Five Little Pigs" by Elizabeth Shippen Green (1871-1954);

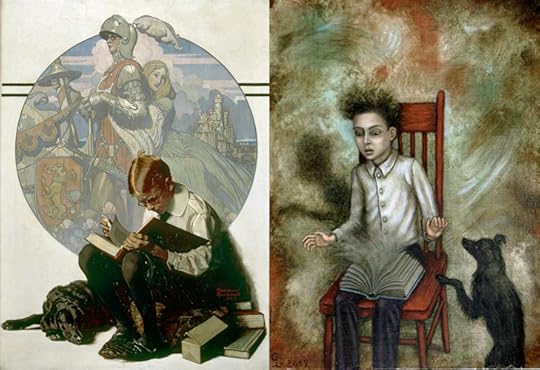

"Jungle Tales" by James J. Shannon (1862-1923); "My Son Reading" by

Carl Larrson (1853-1991) ; a book sculpture by Kerry Miller (working with discarded texts); "Boy Reading" by Norman Rockwell (1884-1978); "The Book" by Gina Litherland; "Little Red" by Jackie Morris; and Tilly dreaming of fairy tales.

Pictures above: A photograph from Transition Voice magazine; Leshy Forest illustrations by Rima Staines; four book sculptures by Su Blackwell (working with discarded texts); "Mole, Ratty, and Otter" by E.H. Shepard (1879-1976); "Fairy Tales" by Mary L. Gow (1851-1929); "The Fairy Book" by Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935); "Five Little Pigs" by Elizabeth Shippen Green (1871-1954);

"Jungle Tales" by James J. Shannon (1862-1923); "My Son Reading" by

Carl Larrson (1853-1991) ; a book sculpture by Kerry Miller (working with discarded texts); "Boy Reading" by Norman Rockwell (1884-1978); "The Book" by Gina Litherland; "Little Red" by Jackie Morris; and Tilly dreaming of fairy tales.

Fairy tales and fantasy, when the need is greatest

"In an age that seems to be increasingly dehumanized, when people can be transformed into non-persons, and where a great deal of our adult art seems to diminish our lives rather than add to them, children's literature insists on the values of humanity and humaneness." - Lloyd Alexander

"The great subversive works of children's literature suggest that there are other views of human life besides those of the shopping mall and the corporation. They mock current assumptions and express the imaginative, unconventional, noncommercial view of the world in its simplest and purest form. They appeal to the imaginative, questioning, rebellious child within all of us, renew our instinctive energy, and act as a force for change. This is why such literature is worthy of our attention and will endure long after more conventional tales have been forgotten."

- Alison Lurie (Don't Tell the Grown-Ups)

"The fairy tale, which to this day is the first tutor of children because it was once the first tutor of mankind, secretly lives on in the story. The first true storyteller is, and will continue to be, the teller of fairy tales. Whenever good counsel was at a premium, the fairy tale had it, and where the need was greatest, its aid was nearest."

- Walter Benjamin ("The Storyteller," Selected Writings: 1935-1938)

"This is the thing about fairy tales: You have to live through them, before you get to happily ever after. That ever after has to be earned, and not everyone makes it that far."

- Kat Howard (Roses and Rot)

"If you read fairy tales carefully, you���ll notice they are mostly about people who aren���t heroes. They don���t have special powers, or gifts. Often they are despised as stupid, They are bullied, beaten up, robbed, starved. But they find they are stronger than their misfortunes."

- Amanda Craig (In a Dark Wood)

"People who���ve never read fairy tales have a harder time coping in life than the people who have. They don���t have access to all the lessons that can be learned from the journeys through the dark woods and the kindness of strangers treated decently, the knowledge that can be gained from the company and example of Donkeyskins and cats wearing boots and steadfast tin soldiers. I���m not talking about in-your-face lessons, but more subtle ones. The kind that seep up from your sub-conscious and give you moral and humane structures for your life. That teach you how to prevail, and trust. And maybe even love."

- Charles de Lint (The Onion Girl)

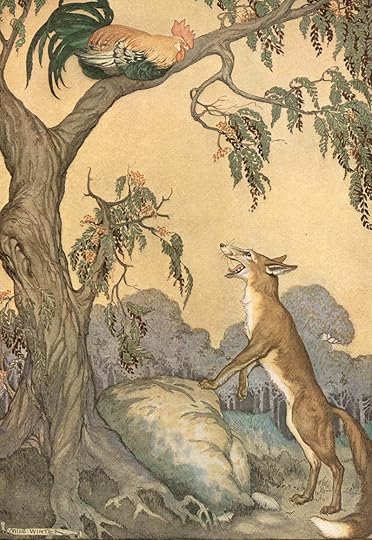

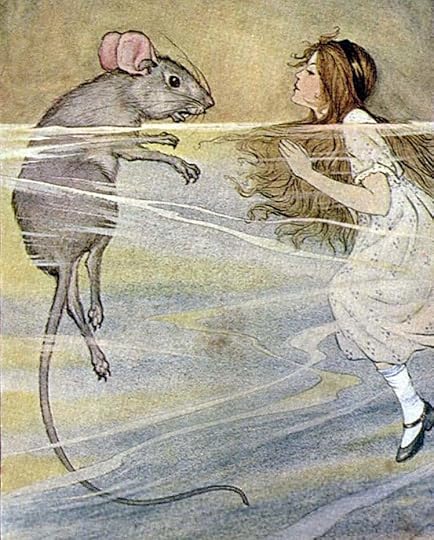

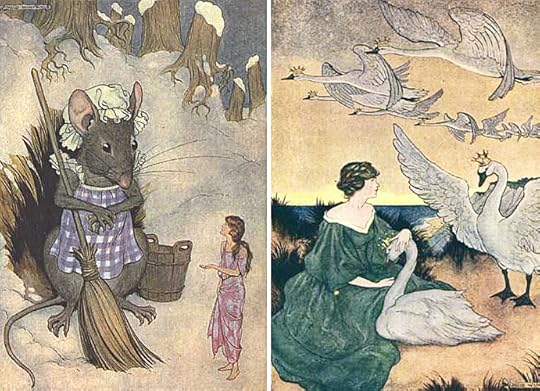

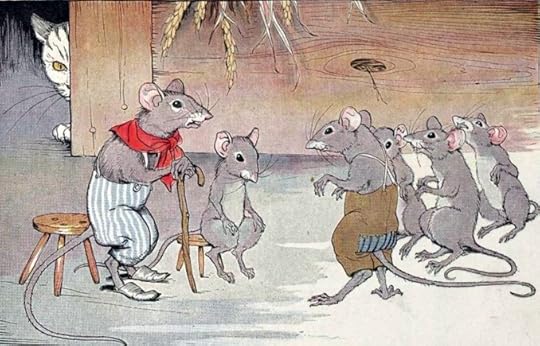

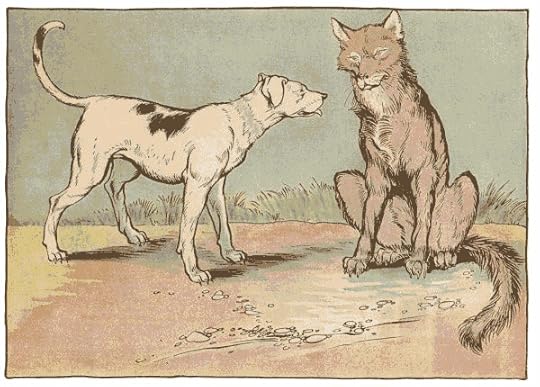

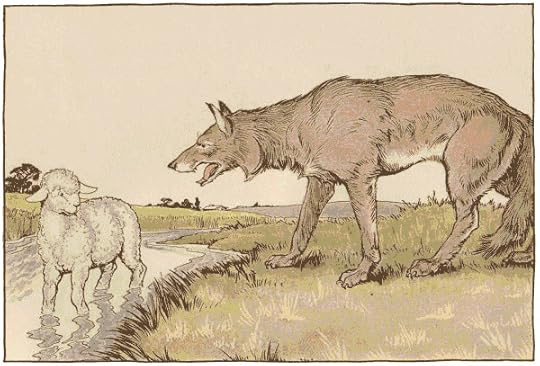

The art today is by the American illustrator Milo Winter (1888-1956).

Born in Princeton, New Jersey, Winter trained at The School of the Arts Institute in Chicago, and illustrated his first children's book (Billy Popgun) at the age of 24. He lived in Chicago until the 1950s, and in New York City thereafter, illustrating a wide range of books for both children and adults -- including Gulliver���s Travels, Tanglewood Tales, Arabian Nights, Alice in Wonderland, Twenty Thousand Leagures Under the Sea, The Three Muskateers, Treasure Island, A Christmas Carol Aesops for Children, and Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers