Terri Windling's Blog, page 102

November 23, 2016

Happy Thanksgiving

Dark Beauty

Having grown up amidst violence and ugliness, I have long dedicated my life to kindness, compassion and beauty: three old-fashioned ideals that I truly believe keep the globe spinning in its right orbit. William Morris, artist and socialist, considered beauty to be as essential as bread in everyone's life, rich and poor alike. It is one of the truths that I live by. Beauty in this context, of course, is not the shallow glamor peddled by Madison Avenue; it's a quality of harmony, balance and interrelationship: physical, emotional, and spiritual all at once. The Din�� (Navajo) called this quality h��zh����, embodied in this simple, powerful prayer: With beauty before me may I walk. With beauty behind me may I walk. With beauty below me may I walk. With beauty above me may I walk. With beauty all around me may I walk.

We are living through a time when dark, violent forces have been released, encouraged, and applified, on both sides of the Atlantic: by Trump in America, the Brexiteers here, Le Pen in France and too many others eager to extend its reach. I contend that in the face of such ugliness we need the beacon of light that is beauty more than ever -- and I hold this belief as someone who has not lead a sheltered life, nor is unaware of the true cost of violence on body and soul. It is because of the scars that I carry that I know that beauty, and art, and story, are not luxuries. They are bread. They are water. They sustain us.

And yet, like many of the writers and artists I know, I too have been struggling with how to move forward: not because I question the value of the work that we're doing here in the Mythic Arts/Fantasy Literature field (addressed in this previous post), but because public discussion, on Left and Right alike, has become so dogmatic, so scolding and contentious, and so mired in black-and-white thinking. In such an atmosphere, nuance and complexity sink like stones; and the idea that there are things that still matter in addition to our political crisis is damned in some quarters as trivial, escapist, or the realm of the privileged: labels which I do not accept.

Here on Myth & Moor, I advocate for the creation of lives rich in beauty, nature, art, and reflection -- but this is by no means a rejection of engagement, action, and fighting like hell against facism. Myth speaks in a language of paradox, and so all of us who work with myth are capable of holding seemingly opposite truths in balance: We'll fight and retreat. We'll cry loudly for justice (in our various ways) and we'll have times of soul-healing silence. We'll look ugliness directly in the face, unflinching, and we will walk in beauty.

Here on Myth & Moor, I advocate for the creation of lives rich in beauty, nature, art, and reflection -- but this is by no means a rejection of engagement, action, and fighting like hell against facism. Myth speaks in a language of paradox, and so all of us who work with myth are capable of holding seemingly opposite truths in balance: We'll fight and retreat. We'll cry loudly for justice (in our various ways) and we'll have times of soul-healing silence. We'll look ugliness directly in the face, unflinching, and we will walk in beauty.

"Beauty is not all brightness," wrote the late Irish poet/philosopher John O'Donohue. "In the shadowlands of pain and despair we find slow, dark beauty. The primeval conversation between darkness and beauty is not audible to the human ear and the threshold where they engage each other is not visible to the eye. Yet at the deepest core they seem to be at work with each other. The guiding intuition of our exploration suggests that beauty is never one-dimensional or one-sided. This is why even in awful circumstances we can still meet beauty. A simple instance of this is fire. Though it may be causing huge destruction, in itself, as dance and color of flame, fire can be beautiful. In human confusion and brokeness there is often a slow beauty present and at work.

"The beauty that emerges from woundedness," O'Donohue noted, "is a beauty infused with feeling: a beauty different from the beauty of landscape and the cold beauty of perfect form. This is a beauty that has suffered its way through the ache of desolation until the words or music emerged to equal the hunger and desperation at its heart....The luminous beauty of great art so often issues from the deepest, darkest wounding. We always seem to visualize a wound as a sore, a tear on the skin's surface. The protective outer layer is broken and the sensitive interior is invaded and torn. Perhaps there is another way to imagine a wound. It is the place where the sealed surface that keeps the interior hidden is broken. A wound is also, therefore, a breakage that lets in light and a sore place where much of the hidden pain of a body surfaces."

"Where woundedness can be refined into beauty," he adds, "a wonderful transfiguration takes place. For instance, compassion is one of the most beautiful presences a person can bring to the world and most compassion is born from one's own woundedness. When you have felt deep emotional pain and hurt, you are able to imagine what the pain of another is like; their suffering touches you. This is the most decisive and vital threshold in human experience and behavior. The greatest evil and destruction arises when people are unable to feel compassion. The beauty of compassion continues to shelter and save our world. If that beauty were quenched, there would be nothing between us and the end-darkness which would pour in torrents over us."

So please, fellow artists and art lovers, keep seeking out, spreading, and making beauty. Don't stop. We all need you. I need you.

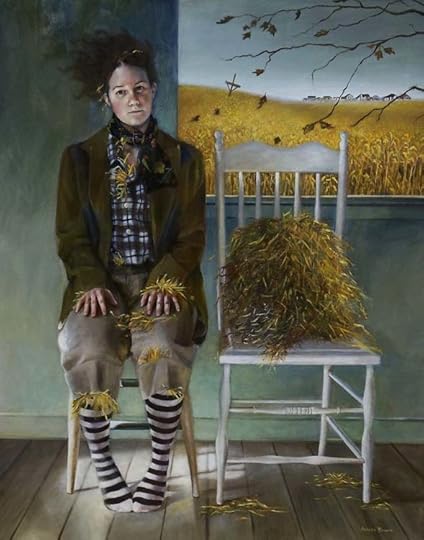

The art today is by Andrea Kowch, an award-winning American painter based in Michigan. Kowch finds inspiration in the emotions and experiences of daily life in the rural Midwest -- resulting, she says, in "narrative, allegorical imagery that illustrates the parallels between human experience and the mysteries of the natural world. The lonely, desolate American landscape encompassing the paintings��� subjects serves as an exploration of nature���s sacredness and a reflection of the human soul, symbolizing all things powerful, fragile, and eternal. Real yet dreamlike scenarios transform personal ideas into universal metaphors for the human condition, all retaining a sense of vagueness to encourage dialogue between art and viewer.���

The passage above is from Beauty: The Invisible Embrace by John O'Donohue (HarperCollins, 2004), all rights reserved by the author's estate. All rights to the art reserved by Andrea Kowch. A related post from 2014: "The Beauty of Brokeness."

The passage above is from Beauty: The Invisible Embrace by John O'Donohue (HarperCollins, 2004), all rights reserved by the author's estate. All rights to the art reserved by Andrea Kowch. A related post from 2014: "The Beauty of Brokeness."

November 21, 2016

The lessons of autumn

From The Solace of Open Spaces by Gretel Ehrlich:

"All through autumn we hear a double voice: one says everything is ripe; the other says everything is dying. The paradox is exquisite. We feel what the Japanese call 'aware' -- an almost untranslatable word meaning something like 'beauty tinged with sadness.' "

"Autumn teaches us that fruition is also death; that ripeness is a form of decay. The willows, having stood for so long near water, begin to rust. Leaves are verbs that conjugate the seasons."

"The truest art I would strive for in any work would be to give the page the same qualities as earth: weather would land on it harshly, light would elucidate the most difficult truths; wind would sweep away obtuse padding. Finally, the lessons of impermanence taught me this: loss constitutes an odd kind of fullness; despair empties out into an unquenchable appetite for life."

The quotes above are from The Solace of Open Space by Gretel Ehrlich (Viking, 1985). The poem in the picture captions is Gary Snyder's paean for the American continent (called "Turtle Island" by some indiginous tribes), from his collection Turtle Island (New Directions, 1974). All rights reserved by the authors.

The quotes above are from The Solace of Open Space by Gretel Ehrlich (Viking, 1985). The poem in the picture captions is Gary Snyder's paean for the American continent (called "Turtle Island" by some indiginous tribes), from his collection Turtle Island (New Directions, 1974). All rights reserved by the authors.

November 20, 2016

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today, some soul-stirring music from the British Isles, to lift the heart and start the week with beauty.

Above: "Un i Sain Ffagan/One for Saint Fahans" by The Gentle Good (Gareth Bonello), from Cardith, Wales. "Saint Fagans National History Museum," says Bonello, "is a large outdoor museum just outside Cardiff. It houses a large social history collection, including an extensive folk song archive, which was my first contact with traditional Welsh music. Until recently I worked for the Museum���s learning department and so I wrote this guitar instrumental as a farewell. It is loosely based on Welsh fiddle tunes although I���ve incorporated some of my other influences as well."

Below: "Olive Willow Song" by Jim Ghedi, who is based in an old mining town near Sheffield (South Yorkshire). In the video below, filmed in one of the oldest buildings in Sheffield, Ghedi is accompanied by Jamie Burney on fiddle and Ben Eckersley on cellow.

Above: "Bagpiper's & Sheila's 70" by Lady Maisery (Rowan Rheingans, Hazel Askew, and Hannah James), from their new album, Cycle. The first tune comes from a 1799 William Mittell manuscript, the second was composed by Hannah. The tunes are accompanied by singing tunes without words in the folk tradition of "mouth music" (or "diddling").

Below: "Ballads Of The Broken Few" by Seth Lakeman, from the other side of Dartmoor, accompanied by Wildwood Kin, from Exeter. The video was filmed in Torre Abbey in south Devon, and the song is from Seth's fine new album of the same name.

November 18, 2016

There is no time for despair

When the clamour of the world (and the Internet) grows harsh and cacophonous, I find it healing, grounding, and necessary to turn away from keyboards and screens, to ration the time I spend online, and to be fully present in tactile world: in the morning light sifting through the studio, in the rising of the wind through the trees behind, in the words slowly forming in ink on fresh white paper spread out on my wooden desktop.

Instead of flicking through Web pages, imbibing the Internet's manic energy and then coming offline feeling fractured and spent, I pull books from down the shelves and turn their rustling pages at a measured, more human pace...and my soul unclenches. My attention deepens. Something vital in me is quickened back to life. And yes, I am using a keyboard now to share these thoughts with you online, but it's not a full rejection of the Web I am after in my life. It's proportion and balance.

Instead of flicking through Web pages, imbibing the Internet's manic energy and then coming offline feeling fractured and spent, I pull books from down the shelves and turn their rustling pages at a measured, more human pace...and my soul unclenches. My attention deepens. Something vital in me is quickened back to life. And yes, I am using a keyboard now to share these thoughts with you online, but it's not a full rejection of the Web I am after in my life. It's proportion and balance.

The Internet is a useful communication platform, and an increasingly important one...but books, oh, books more than paper and ink. They are powerful medicine. Real books, I mean. Physical books, sitting on the dusty shelves of my studio and surrounding me like old friends, dog-earred and battered with love and use, their pages thick with margin notes and underlines.

How could I ever doubt that art matters? Words have saved me over and over. Words are saving me right now. Books are what I turn to when the world grows dark, and they never fail to give me strength.

This morning, for instance, Ben Okri asks me:

"What hope is there for individual reality or authenticity, when the forces of violence and orthodoxy, the earthly powers of guns and bombs and manipulated public opinion make it impossible for us to be authentic and fulfilled human beings?"

I've been asking myself the same question all week.

"The only hope," he answers, "is in the creation of alternative values, alternative realities. The only hope is in daring to redream one's place in the world -- a beautiful act of imagination, and a sustained act of self becoming. Which is to say that in some way or another we breach and confound the accepted frontiers of things."

Then Rebecca Solnit joins the conversation:

"Cause-and-effect assumes history marches forward," she notes, "but history is not an army. It's a crab scuttling sideways, a drip of soft water wearing away stone, an earthquake breaking centuries of tension. Sometimes one person inspires a movement, or her words do decades later, sometimes a few passionate people change the world; sometimes they start a mass movement and millions do; sometimes those millions are stirred by the same outrage or the same ideal, and change comes upon us like a change of weather. All that these transformations have in common is that they begin in the imagination, in hope."

"To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic," adds Howard Zinn. "It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty, but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, kindness. What we choose to emphasize in this complex history will determine our lives. If we see only the worst, it destroys our capacity to do something. If we remember those times and places -- and there are so many -- where people have behaved magnificently, this gives us the energy to act, and at least the possibility of sending this spinning top of a world in a different direction."

Barry Lopez pulls me out of a Western-centric point of view, reminding me of the things I share in common with people the world over:

"I believe in all human societies there is a desire to love and be loved," he says, "to experience the full fierceness of human emotion, and to make a measure of the sacred part of one's life. Wherever I've traveled -- Kenya, Chile, Australia, Japan -- I've found the most dependable way to preserve these possibilities is to be reminded of them in stories. Stories do not give instruction, they do not explain how to love a companion or how to find God. They offer, instead, patterns of sound and association, of event and image. Suspended as listeners and readers in these patterns, we might reimagine our lives. It is through story that we embrace the great breadth of memory, that we can distinguish what is true, and that we may glimpse, at least occasionally, how to live without despair in the midst of the horror that dogs and unhinges us."

Terry Tempest Williams concurs, and affirms the role that artists play in the transmission of such stories:

"Bearing witness to both the beauty and pain of our world is a task that I want to be part of. As writers, this is our work. By bearing witness, the story that is told can provide a healing ground. Through the art of language, the art of story, alchemy can occur. And if we choose to turn our backs, we've walked away from what it means to be human."

Then Toni Morrison takes me firmly by the shoulders and sends me back to my desk again:

Troubled times, she says, are "precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.

"I know the world is bruised and bleeding," she adds, "and though it is important not to ignore its pain, it is also critical to refuse to succumb to its malevolence. Like failure, chaos contains information that can lead to knowledge -- even wisdom. Like art."

Like art indeed.

Words: The first five quotes above are from the following books, all recommended: A Way of Being Free by Ben Okri (Phoenix, 1998); Hope in the Dark by Rebecca Solnit (Nation Books, 2005); You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train by Howard Zinn (Beacon Press 2002), About This Life by Barry Lopez (Vintage, 1999), and A Voice in the Wilderness: Conversations with Terry Tempest Williams, edited by Michael Austin (Utah State University Press, 2006). The final quote is from "No Place for Self-Pity, No Room for Fear" by Toni Morrison (The Nation, March 2013); I owe thanks to Maria Popova of Brain Pickings for introducing me to it. Pictures: The drawing and painting above are by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). The photographs are from my studio cabin, perched on a Devon hillside at the edge of a small wood.

November 17, 2016

Something we once knew

1

Sometimes in the open you look up

where birds go by, or just nothing,

and wait. A dim feeling comes

you were like this once, there was air,

and quiet; it was by a lake, or

maybe a river you were alert

as an otter and were suddenly born

like the evening star into wide

still worlds like this one you have found

again, for a moment, in the open.

2

2

Something is being told in the woods: aisles of

shadow lead away; a branch waves;

a pencil of sunlight slowly travels its

path. A withheld presence almost

speaks, but then retreats, rustles

a patch of brush. You can feel

the centuries ripple generations

of wandering, discovering, being lost

and found, eating, dying, being born.

A walk through the forest strokes your fur,

the fur you no longer have. And your gaze

down a forest aisle is a strange, long

plunge, dark eyes looking for home.

For delicious minutes you can feel your whiskers

wider than your mind, away out over everything.

Poet William Stafford (1914-1993) was dedicated to the cause of pacifism, deeply in love with the natural world, and described himself as "one of the quiet of the land." His collection Traveling Through the Dark won the National Book Award in 1963, and he was the nation's Poet Laureate in 1970.

''We may feel bitterly," wrote Adrienne Rich, "how little our poems can do in the face of seemingly out of control technological power and seemingly limitless corporate greed, yet it has always been true that poetry can break isolation, show us to ourselves when we are outlawed or made invisible, remind us of beauty where no beauty seems possible, remind us kinship where all is represented as separation."

"Atavism" is from Passwords by William Stafford (HarperCollins, 1991). The Adrienne Rich quote is from "Defy the Space That Separates" (The Nation, Oct 1996). All rights reserved by the authors' estates.

"Atavism" is from Passwords by William Stafford (HarperCollins, 1991). The Adrienne Rich quote is from "Defy the Space That Separates" (The Nation, Oct 1996). All rights reserved by the authors' estates.

November 16, 2016

Creating a tolerable world

Ana��s Nin was born to Cuban parents in France, raised in Europe, Cuba and the U.S., and then settled in Paris after her marriage, establishing herself in its lively art community of the '20s & '30s. By the summer of '39, however, facism was rising, war was approaching, and the French government was urging foreign nationals to get out of the country while they still could. Nin followed her American husband to New York, heart-broken at losing the city she loved, worried sick about friends and family she was leaving behind. Fourteen years later, emerging from the world-wide trauma of the war years, she wrote the following words her diary:

"Why one writes is a question I can answer easily, having so often asked it of myself. I believe one writes because one has to create a world in which one can live. I could not live in any of the worlds offered to me -- the world of my parents, the world of war, the world of politics. I had to create a world of my own, like a climate, a country, an atmosphere in which I could breathe, reign, and recreate myself when destroyed by living. That, I believe, is the reason for every work of art.

"The artist knows the world is a subjective creation," Nin continued, "that there is a choice to be made, a selection of elements. It is a materialization, an incarnation of his inner world. Then he hopes to attract others into it, he hopes to impose this particular vision and share it with others. When the second stage is not reached, the brave artist continues nevertheless. The few moments of communion with the world are worth the pain, for it is a world for others, a gift for others, in the end. When you make a world tolerable for yourself, you make the world tolerable for others."

It has been one week since the U.S. election, and the country has taken a fearsome turn for those of us who value civility, decency, diversity, and the norms of democracy. I keep hearing the same question from friends and colleagues in the Mythic Arts field: How can I simply return to my work? Making art can seem like a frivolous pursuit compared to the urgent news of the day; to the need for action and activism, as opposed to the quiet withdrawal from the world upon which creative work often depends.

I have two thoughts about this. First, that art is not frivolous. As Jeannette Winterson states so eloquently:

"Naked I came into the world, but brush strokes cover me, language raises me, music rhythms me. Art is my rod and my staff, my resting place and shield, and not mine only, for art leaves nobody out. Even those from whom art has been stolen away by tyranny, by poverty, begin to make it again. If the arts did not exist, at every moment, someone would begin to create them, in song, out of dust and mud, and although the artifacts might be destroyed, the energy that creates them is not destroyed. If, in the comfortable West, we have chosen to treat such energies with scepticism and contempt, then so much the worse for us."

Or as Ursula Le Guin said in her National Book Award acceptance speech in 2014:

"Hard times are coming, when we���ll be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope. We���ll need writers who can remember freedom -- poets, visionaries -- realists of a larger reality."

And how right she was.

My second thought is that, yes, we are in a period of cultural crisis -- and in such times, each of us must decide where our energy and resources can best be employed. For some, this may mean postponing personal projects in order to throw oneself fully into activism as a matter of urgency. The brilliant young writer Laurie Penny, for example, tweeted this last week:

"I'd planned to scale back the full-time political writing to do more fiction. That nice life plan is now in the bin. That's okay. Game on."

For others, full-time activism is not a practical option, nor is it the best deployment of our time and our gifts. I'll use myself as an example here. I was politically active in my younger years, but in late middle-age I'm contrained by health issues, by family responsibilities, and by the paucity of "spoons" I have to distribute among competing priorities each day. Within these constraints, the best use of my time is to focus on the things I'm designed by my nature to do: to write, to paint, to create "beauty in a broken world" (to use Terry Tempest William's evocative phrase), and perhaps lift the spirits of those who are on the Front Lines, doing the hard physical work I can no longer do.

I do not think this task is a lesser one. My job is to tell stories, in words and in paint -- and stories, well-told, are not trivial things. Stories teach. Challenge. Console. Refresh. They examine the world, and re-imagine the world. They remind us of what courage looks like, and hope. They explain us to each other. They explain us to ourselves. They feed us. Heal us. Confound us, and shake us out of despair or complacency. They light the path through the dark of the forest, bring us home on a path of breadcrumbs and stones. Telling stories is meaningful work, even now. Especially now. Game on.

I don't mean to say it's a binary choice: going out into the world in the form of activism or turning inward to create works of art. We can do both, of course, and many of the artists I admire most throughout history have blended the two. How do we do this? With "sacred rage," Terry Tempest Williams advises, and an open and active heart:

"I don���t think there is anything as powerful as an active heart," she says. "And the activists I know possess this powerful beating heart of change. They do not fear the wisdom of emotion, but embody it. They know how to listen. They are polite when they need to be and unyielding when necessary. They remain open, even as they push boundaries and inhabit the margins, understanding eventually, the margins will move toward the center. They are tenacious, informed, patient, and impatient, at once. They do not shy away from what is difficult. They refuse to accept the unacceptable. The most effective activists I know are in love with the world. A good activist builds community.

"I used to ask the question, 'Am I an activist or a writer?' I don���t ask that anymore. I am simply a human being engaged."

May we all be "human beings engaged" with the world around us, in one way or another. Loudly or softly, on the streets or at the desk...whichever way suits each of us best. We need it all right now. We need the urgent political conversations...but also the quiet discussions of books and art, folklore and myth, for they serve to keep our hearts open, receptive and responsive. To remind us of what we're fighting for. And to honor what's soft, and deep, and nuanced at a time when the dominant discourse is too often hard, and shallow, and simplistic.

"All kinds of activism will be needed in the coming months and years," says Laurie Penny. "Including the quiet, gentle activism of quiet, gentle people."

Myth & Moor is a safe haven for the quiet and gentle....

But if you're noisy and kind, you are welcome here too.

The passage by Ana��s Nin is from The Diary of Ana��s Nin, Volume 5, 1947-1955 (Harcourt, 1975). The passage by Jeanette Winterson is from Art Objects (Vintage, 1966). The two quotes by Laurie Penny are from her Twitter page. The quote by Terry Tempest Williams is from an interview by Devon Fredericksen (Guenerica, August 2013). The poem in the picture captions is from What to Remember When Waking by David Whyte (Sounds True, 2010). All rights reserved by the authors. The drawing is by Charles Robinson (1870-1937).

The passage by Ana��s Nin is from The Diary of Ana��s Nin, Volume 5, 1947-1955 (Harcourt, 1975). The passage by Jeanette Winterson is from Art Objects (Vintage, 1966). The two quotes by Laurie Penny are from her Twitter page. The quote by Terry Tempest Williams is from an interview by Devon Fredericksen (Guenerica, August 2013). The poem in the picture captions is from What to Remember When Waking by David Whyte (Sounds True, 2010). All rights reserved by the authors. The drawing is by Charles Robinson (1870-1937).

November 15, 2016

Guest Post: Tenderness, the Breaker of Curses

My apologies for missing this week's "Monday Tunes" post. I had computer problems yesterday, and spent the day sorting it out -- but all is well now and I'm back online again.

Today's Guest Post is by my friend Briana Saussy, based in San Antonio, Texas. Bri is a writer, teacher, counselor and community-maker deeply rooted in the myth & fairy tale tradition. One of the many ways she spreads magic in the world is through her wonderful Lunar Letters, sent out on the full moon each month. I love Bri's writing, and these missives are invariably wise, insightful, and enchanting.

Like many around the world, I am still in a state of shock and horror from the American election result, compounded with the fall-out from the EU Referendum result here in UK. Speaking to my husband about it, he reminded me that fearfulness of the future can make us draw in and close ourselves off, when what we need to do is the opposite: Open our hearts, step out into the world, carry the light forward when the world feels dark. Brianna's latest Lunar Letter is helpful in this regard, and I asked her permission to share it here.

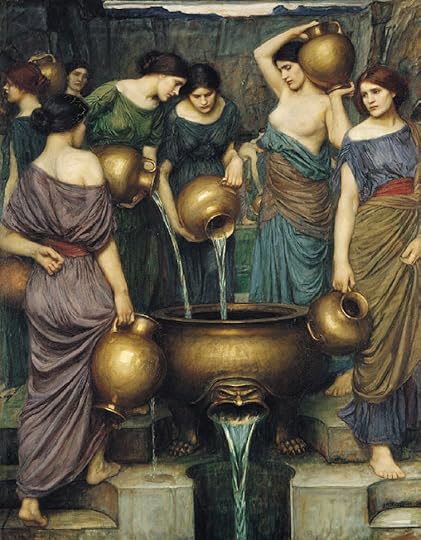

"To be cursed," writes Briana, "is to be dried up, devoid of moisture and suppleness, brittle and lacking the essential ingredient of life: fresh, circulating water. The most harmful afflictions of body, mind, spirit, and soul are those that seek to take away, ignore, and otherwise exploit our ability to be tender towards ourselves and towards one another. The remedy for this affliction may take many different forms, but always includes blessing what is tender within you.

"To be cursed," writes Briana, "is to be dried up, devoid of moisture and suppleness, brittle and lacking the essential ingredient of life: fresh, circulating water. The most harmful afflictions of body, mind, spirit, and soul are those that seek to take away, ignore, and otherwise exploit our ability to be tender towards ourselves and towards one another. The remedy for this affliction may take many different forms, but always includes blessing what is tender within you.

"In many different cultures, the evil eye is understood primarily as a ���drying��� condition, one in which your money dries up, your health dries up, your fertility and verve for life also dry up. In opposition, to be blessed is to be moist, supple, full of flowing water, clean, bathed, and tender like new shoots of grass, tender like fresh green wood sprouting forth from a tree, tender like the water filled skin of a newborn baby nestled up safely in your arms. Losing one���s tenderness, therefore, is tantamount to losing one���s life.

"The loss of tenderness and thus of life is not difficult to achieve. Let yourself be taken over by anger, envy, jealousy, hatred, and fear, and you will know how easy it is to do. You can observe for yourself the negative consequences of being taken over by these emotions, how they cause a withering and a contraction in your life and relationships. But even so, we may come to doubt the need for tenderness. Why be tender in a world and in a time that seems so often to only reward the tougher-than-nails? How does one cultivate tenderness in the face of violence, bloodshed, and injustice? What is tenderness other than one more vulnerability, easily overcome by those who are 'stronger'? How do we stay tender in times such as these and how do we bless our tender places?

"We bless our tender places by calling in the waters. We call in the waters so that we might cry good and salty tears, make nourishing soup, wash the dust off our clothes, and irrigate the seeds we have planted. So that we may drink of the waters and bathe in them, washing ourselves clean, literally renewing ourselves. We call in the waters from within, reaching deep and accessing the sacred well that may be blocked or polluted, but is simply waiting to be set free, waiting to be cleansed so that it can run, rush, and spring forth from the solid ground of your very life.

"Tenderness -- and the circulating life waters corresponding to it - points to the deepest parts of our resilient nature. Resilience is a power, and it is what makes for much needed hardiness of life and soul.

"Tenderness -- and the circulating life waters corresponding to it - points to the deepest parts of our resilient nature. Resilience is a power, and it is what makes for much needed hardiness of life and soul.

"Sometimes it seems that there is no water to call in, no source of nourishment, of life-celebrating and life-protecting magic. But finding the water, finding the sources of life and nourishment, is not an easy task. Especially not when you look around and all you see is hard, sun-baked rock, packed gravel, and too much asphalt."I have lived most of my life in desert regions, and so I know from firsthand experience the water that is there, hundreds of feet under the ground and flowing in madly rushing rivers or collected in fathomless lakes. You don���t see it, but it is there. When the territory around looks most inhospitable to tenderness, then you know that you are in exactly the right spot to fill yourself up with all that gives life, all that keeps you supple, all that keeps you tender. You may have to dig for it, you might have to learn to collect it drop by drop from precious rainfalls, you may end up going on a pilgrimage to find it; but it is there, waiting to be called upon.

"To bless tenderness is also to protect it. In desert areas that are hot, arid, and dry, the culture is one of toughness, and even the plants with their prickles and thorns seem to just be waiting for their chance to chew you up and spit you out. If you neglected to look closely, you would be forgiven for thinking that toughness and hardness is all that matters. But soulful seekers do look closer, and what we find are that the plants with the best boundaries are the same that have the most tender, water-filled skins. They give us the blessing way. Find the water, find the sources of life, and when you do, keep them safe; build a good boundary around them. Don���t just let anyone access your tenderness, choose actively and with discernment who and when and where receives the privilege of your softness.

"To bless tenderness is also to protect it. In desert areas that are hot, arid, and dry, the culture is one of toughness, and even the plants with their prickles and thorns seem to just be waiting for their chance to chew you up and spit you out. If you neglected to look closely, you would be forgiven for thinking that toughness and hardness is all that matters. But soulful seekers do look closer, and what we find are that the plants with the best boundaries are the same that have the most tender, water-filled skins. They give us the blessing way. Find the water, find the sources of life, and when you do, keep them safe; build a good boundary around them. Don���t just let anyone access your tenderness, choose actively and with discernment who and when and where receives the privilege of your softness.

"To bless our tender places is to ask for and gladly accept help. In many cultures there are Gods and Holy Helpers who bring the waters of life, bring the rains, bring the thunderclouds that roll in with their big noise, making the hairs on the back of your neck stand up and reminding you that you are very much alive, creating with every breath you take, holding an infinite cosmos within your very body. We are not islands meant to do it all on our own. We have two-legged and four-legged, winged, clawed, fanged, and finned relatives who are here and ready and willing to help point us in all the right directions; so we look to them and we listen.

"Finally, tenderness is meant to be shared. Like water, it requires a solid vessel, the boundary of the cacti, to keep it stored up safely; but once we are filled up with it we cannot help but overflow. The overflow happens in many ways -- through tears and laughter and deep kisses and long touches, through creative work and vibrant dance, and the sweet sound of the saxophone or drums under the stars. These are all medicines, results from the blessing and safe keeping of your tenderness, that literally spill forth and out into the world much like water, nourishing much like water, and restoring so many that are on the brink of death back into life.

"Tenderness is no small thing. It is, in truth, a source of the greatest strength. It is not the weak spot or the pain point to be covered up, but rather a sign post, the tracks in the snow, that carry you forward to your own headwaters, no matter where it leads. So remember that anytime the flow feels blocked, anytime your skin feels shrunken and life feels too dry, relationships too brittle, and your broken places too yawning and jagged; remember when you feel raw and exposed, vulnerable, or too tender, remember what lessons tenderness has to teach you about your own hardiness, your own deeply resilient nature. It may be time to bless your most tender places and call forth the waters once more."

Divination: under the light of the full moon in Taurus with your divination tools at the ready ask:

Where can I be more tender?

Where can is my tenderness ready to be shared?

Where do I need better protection and boundaries around my tenderness?

If you'd like to sign up for Briana's Lunar Letters, you can do so here. You can also read her previous letters by following the same link. I also recommend her Daily Blessings, beautifully illustrated by Cassandra Oswald. For more about lore of water, see my previous post "Water, wild and sacred."

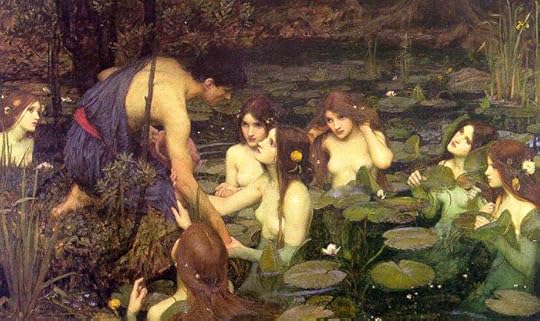

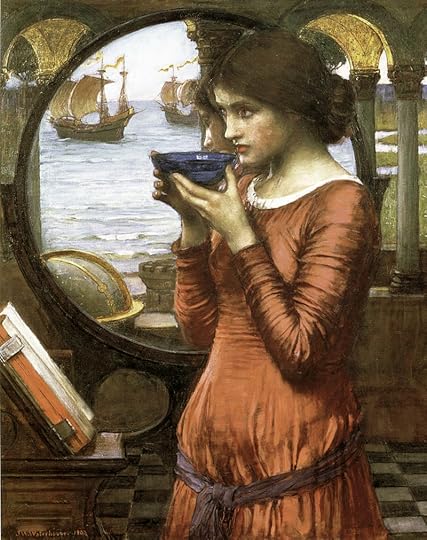

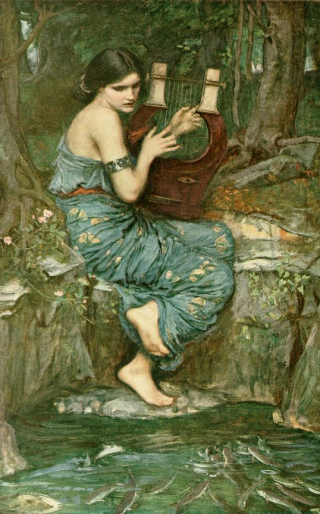

The art today is by John William Waterhouse (1849-1917), an English painter in the "Second Wave" of the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

November 10, 2016

Re-connection

I am going to ground for a few days in order to re-connect with nature and art, and to re-find my natural optimism and fighting spirit. I wrote about the process of doing so here, in a piece I posted last June.

I'll be back on Monday. Take care of yourselves.

The poem in the picture captions is from Wendell Berry's Standing by Words (Counterpoint, 2005); all rights reserved by the author.

The poem in the picture captions is from Wendell Berry's Standing by Words (Counterpoint, 2005); all rights reserved by the author.

November 9, 2016

The view from here

Today we grieve. Tomorrow we fight. Art & activism matter more than ever. So does community. Stay strong.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers