Terri Windling's Blog, page 104

October 27, 2016

"Into the Wood" series, 56: Death in Folk & Fairy Tales

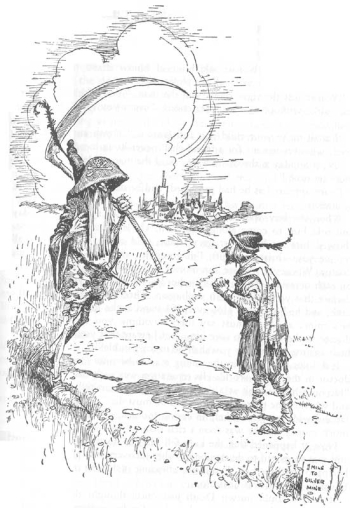

Once upon a time there was a poor tailor who could barely feed his twelve children. When the thirteenth was born, the distraught man ran out to the road nearby determined to find someone to stand as godfather to the child. He knew of no other way that he could provide for his newborn son. The first person to pass was God, but the poor tailor rejected him. "God gives to the rich and takes from the poor. I'll wait for another to come." The second to pass was the Devil, but the poor tailor rejected him too. "He lies and cheats and leads good men astray. I'll wait for another." The third man to pass was Death, and the poor tailor considered him carefully. "Death treats all men alike, whether rich or poor. He's the one I'll ask."

Now Death had never been asked such a thing before, but he agreed at once. "Your child shall lack for nothing," he said, "for I am a powerful friend indeed." The years went by and he kept his word. The boy and his family lacked for nothing. When the boy finally came of age, his Godfather Death appeared before him. "It is time to establish you in the world. You are to become a great physician. Take this magical herb, the cure for any malady of this earth. Look for me when you're called to a patient's bed. If you see me at its head then give them a tincture of the herb and your patient will be well. But if you see me at the foot, you'll know it is their time to die. Your diagnosis will always be right, and you will be famous around the world."

Now Death had never been asked such a thing before, but he agreed at once. "Your child shall lack for nothing," he said, "for I am a powerful friend indeed." The years went by and he kept his word. The boy and his family lacked for nothing. When the boy finally came of age, his Godfather Death appeared before him. "It is time to establish you in the world. You are to become a great physician. Take this magical herb, the cure for any malady of this earth. Look for me when you're called to a patient's bed. If you see me at its head then give them a tincture of the herb and your patient will be well. But if you see me at the foot, you'll know it is their time to die. Your diagnosis will always be right, and you will be famous around the world."

And so it was. The young man became the most famous doctor of his time, and his fame spread far and wide until it reached the ears of the king. The king lay sick in his golden bed and he summoned the tailor's son to him. But when the young doctor arrived at last in the richly appointed bedchamber, he saw that the king was gravely ill and that Death stood at his feet. Now this king was much beloved and the young man wanted to cure him very much. He quickly instructed the court attendants to turn the bed the opposite way, and he then restored the king to health with a tincture of the magical herb. Death was not pleased. He shook his long, bony finger at his godson and said, "You must never cheat me again. If you do, it will be the worse for you."

The young man took this warning to heart and did not cross his godfather again -- until the king's daughter fell ill and he was summoned back to the palace. This was the good king's only child. He was desperate to see her well. "Save her life," said the king, "I shall give you her hand in marriage." The doctor went to the lovely maiden's bedchamber, where Death was waiting. He stood at the foot of the princess's bed, ready to take her away. "Don't cross me again," his godfather warned, but the doctor was half in love already. He ordered the princess's bed to be turned and he gave her the herbal tincture.

The princess was healed immediately, but Death reached out a cold, white hand and clamped it on his godson's arm, saying. "You'll go with me instead." He took the young man into a cave, its wall niches covered with millions of candles. "Here," he said, "are candles burning for every life upon the earth. Each time a candle grows low and snuffs out, a life is ended. This one is yours." Death pointed to a candle that had burned down to a pool of wax. "Please," his godson begged, "for many years I was your faithful servant. Please, Godfather Death, won't you light a new candle for me?" Death gazed at him remorselessly. The candle sputtered and flickered out. The young doctor fell down dead.

This story, titled Godfather Death, comes from the German folk tales of the Brothers Grimm. It can also be found in variant forms in a number of other countries as well -- such as The Shepherd and the Three Diseases from Greece, The Just Man from Italy, The Soul-Taking Angel from Armenia, The Contract with Azrael from Egypt, Dr. Urssenbeck from Austria, and The Boy With the Keg of Ale from Norway. It's one of a number of folk and fairy tales in which Death is personified: sometimes as a frightening figure, sometimes as a compassionate one, and sometimes as a matter-of-fact man or woman with a job to do.

There are many tales in which Death is out-witted, such as Jump In My Sack from Slovenia -- in which a young man pleases a powerful fairy who offers him two magic wishes. He asks for a sack which will suck in whatever he names, and a stick that will do all he asks. These wishes are granted, and the young man uses the sack to bring him meat and drink, until he comes to a great city and falls in with a group of gamblers. Death (or the Devil, in an Italian version of the tale) is among the gamblers in disguise, amusing himself at the gaming table by luring men to financial ruin and then collecting their souls when they are driven to suicide. The young man sees through Death's disguise. He orders the sack to suck Death up, then orders the stick to beat him soundly. At length Death begs for mercy, promising the young man whatever he wants. The young man asks for the restoration to life of all his gambling friends, and then orders Death to leave at once and to stay far away from him. But many years later, old and ill, he has second thoughts about this bargain. He now uses the sack to call Death back, and is grateful to be led away.

In a number of tales Death is outwitted and banished with dire consequences. The old, the ill, and the fatally wounded do not die, but linger in agony until finally the importance of Death's role can no longer be ignored. In a Spanish tale, an old woman traps Death in her pear tree and will not let him go until he promises to never come back. The woman's name is Tia Miseria (Aunt Misery), and as long as Death keeps his promise to her, we'll have misery in the world. In a similar tale from Portugal, Death outwits the old woman in the end -- but finds her so shrewish, he promptly brings her back to her house and flees.

Some tales feature a Godmother Death, such as versions of the stories told in Slovenia and Moravia, and across the sea in America's Appalachian Mountain region. The depiction of death as male or female depended on the culture, the times, and the storyteller, but examples of both are widely found in folk tales the world over. In Death and the Maiden, a story known in both folk tale and folk ballad form, the interaction of a male Death figure and the well-born young woman he's come to claim has an almost seductive quality. She tries to bargain for her life, offering up her gold and jewels, as he gently explains that she must go with him that very night. In some pictorial representations of the story, Death is portrayed as a knight clad in black; in others, more frighteningly, he is a skeleton in knightly clothes. (Franz Schubert drew on this tale for his lovely Quartet in D Minor: Death and the Maiden, composed in 1824.) In a Turkish fairy tale, The Prince Who Longed for Immortality, a male Death figure is pitted against the Queen of Immortality. They wager over who will get the hero by throwing him up in the air. In a story from northern Italy, Death is portrayed as a lovely young woman. She's an unwelcome guest in the palace when her true identity is revealed (as she takes the handsome young king away) ��� but a welcome guest in the cottage of a poor, old woman who's been waiting for her.

In early medieval representations, Death was usually masculine: powerful, pitiless, omnipresent. Clad in black, he was the Grim Reaper who cut men and women down in their prime, prince and poet and pauper alike. In the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, we find more examples of Death as a woman ��� such as Donna La Morte in Petrarch's famous poem, "The Triumph of Death," who appears suddenly all "black, and in black" to claim the life of a young noblewoman. The Dance of Death (or Danse Macabre) first appeared in the middle of the 14th century as the Black Death ravaged its way across Europe. The Dance of Death originated in the form of a Christian spectacular play, performed in churchyards and cemeteries among charnel houses and graves. Death appeared here as masked, skeletal figures intent on leading away a series of victims (twenty-four in number) from all classes of society. The victims would protest, offering reasons why they and they alone should be spared, but in the end all are danced off to the grave while the fiddlers play. This was paired with sermons stressing that death could strike anyone at any time, exhorting the audience to prepare themselves and live free of sin.

In Italy in the following century, death spectacles were more elaborately staged. As Charles B. Herbermann and George Charles Williams describe them (in the Knight, Death, and the Devil."

My friend and colleague Midori Snyder is a writer who has worked with the folklore of death in several ways ( in her elegiac faery novel Hannah's Garden, her children's story "Jack Straw" [read it online here], and in a novel-in-progress based on an Italian fairy tale), so I asked her for her thoughts on the subject:

"There are many characters in folklore associated with death," Midori responded, "various death-announcers and death-dealers, but I would suggest that they are not actually Death figures, as in a Mr. or Ms. Death personified. Morrigan, the Irish goddess of War, for example, revels not only in the glory of war but also its violence and carnage: the taste of fear, the scent blood, the dying moments of warriors on the battlefield. Flying above the battle in the form of a black crow, she is a figure of Fate, like the Valyries of Norse myth, foretelling who will live and who will die...but she is not Death herself. The various incubi and succubi of European folk legend are death-dealers, in their actions are fatal to the luckless mortals who get tangled up with them...but they aren't Death, either. Their interest is in specific individuals (generally those who catch their sexual interest), whereas Death is an equal opportunity killer. Death takes the child, the adult, the old, the young, the strong, the weak. Death doesn't discriminate, but moves over everything in a constantly shifting, unpredictable pattern. That is what is so terrifying, the way death resists being slotted into a known plan. All we know is that it will happen -- but never when and never how. Tales such as Godfather Death, or the medieval Dance of Death, specifically addressed this idea and this terror -- as opposed to folklore's other death-dealing creatures, who select very specific victims. Edgar Allan Poe's frightening story 'Masque of the Red Death' plays with the idea that one imagines one can foretell and identify Death, and therefore keep him/her out. And what is chilling in the tale is the sheer ease with which Death infiltrates the masque with the rest of the revelers."

"I've also been thinking about the differences in those stories where the dead live in an alternate world to ours," Midori continues. "The Greek god of the Underworld, Hades, is not a Mr. Death figure, but, rather, he is the King of the Dead, content to rule over the souls who have come to him instead of going out and nabbing them himself. Likewise in the Christian tradition, where those who die are 'born to eternal life' in heaven or hell, Christ isn't a Mr. Death, and neither is Satan (especially if one thinks of Dante's image of him, frozen in a bed of ice), although both have something to say about dead souls in the afterlife.

"When we look at myth, specifically at that cycle of tales in which death is brought into the world (often by a bumbling Trickster figure), death is rarely personified. It moves like a force of nature, invisible and ubiquitous. Death happens. But in folk and fairy tales, death acquires a face, a figure, a point of consolidation -- which allows the protagonist of the tale, when confronted with his or her mortality, to recognize the moment at hand. The personified images of Mr. or Ms. Death are generally of the wanderer, the traveler, the one not bound by place or position. The very anonymity and flexibility of personified Death insures the equality with which death meets us all...high and low.

"Death is also a mirror reflection of ourselves. In medieval and Renaissance pictorial representations, Death often wears a tattered, mirror version of the clothes his victim wears. It is, after all, for each of us, our Death that we meet, no one else's. In the stories where he appears, Mr. Death is a reflection -- a concrete, externalized image of the protagonist's death. And therefore his/her appearance has something to say about the character whose death it is that has arrived. From the Grim Reaper of medieval legend to the elegant young stranger in Peter Beagle's story 'Come Lady Death' or the 'woman in white' in Bob Fose's All That Jazz, from Shiva with her voluptuous form and deadly arms to Johnny Depp in Jim Jarmusch's haunting film Dead Man, Death appears in a variety of guises but also functions differently as a narrative sign. Coyote's death in Trickster myths, for example, is experienced (and read) very differently than the death proffered by the skeletal knight who comes to take the Maiden away. The first is read as temporary, because Coyote always come back to life -- while the other is frighteningly permanent. The skeleton reflects what the Maiden will become. Indeed, what we'll all become."

Death is a frequent theme in fairy tales -- as well as the stark realities of death's aftermath, for many stories begin with the death of one or both of the hero's parents. Fairy tale historian Marina Warner points out that death in childbirth was far more common in centuries prior to our own and the prevalence of step-children and orphans in fairy tales reflected a social reality. Many of these tales (in their pre-Victorian forms) were exceedingly violent, including those gathered by the Brothers Grimm in editions published for German children. Though the Grimms are known to have edited their fairy tales with a rather heavy hand, stripping them of sensuality and moral ambiguity, they had no such qualms about leaving much of the worst violence intact. (Indeed, as scholar Maria Tatar has noted, in some stories they beefed it up.) Murder, cannibalism, and infanticide are staples of the fairy tale genre. From Bluebeard with his chamber of horrors to the goodwife in The Juniper Tree who decapitates her inconvenient step-son, death is a very real threat in the tales -- yet it does not always have the last word. In Fitcher's Bird (a Bluebeard variant), the heroine not only outwits the wizard who aims to marry then murder her, but she's able to bring the hacked-up bodies of her predecessors back to life. The step-son in The Juniper Tree returns to earth in the form of a bird. Cinderella's dead mother returns as a fish (in the oldest, Chinese version of the story), a cow (in a Scottish variant), or a tree (in the version found in Grimms), watching over her daughter and whispering wise words of advice.

Another good example is the story of Snow White. Our heroine is not merely sleeping but dead, in the early versions of her tale: displayed in a glass coffin, her form incorruptible, like a saint's. The necrophilic overtones of the story are most evident in a 16th century Italian version called The Crystal Casket. In this tale, the heroine is persuaded to introduce her teacher to her widowed father. Marriage ensues, but instead of gratitude, the teacher treats her step-daughter cruelly. An eagle helps the girl to escape and hides her in a palace of fairies. The step-mother then hires a witch, who sells poisoned sweetmeats to the girl. She eats one and dies. The fairies revive her. The witch strikes again, disguised as a tailoress with a beautiful dress to sell. When the dress is laced up, the girl falls down dead -- and this time the fairies will not revive her. (They're miffed that she keeps ignoring their warnings.) They place the girl's body in a fabulous casket, rope the casket to the back of a horse, and send it off to the royal city.

The casket is soon found by a prince, who falls in love with the beautiful "doll" and takes the body home with him. "But my son, she's dead!" protests his mother. The prince will not be parted from his treasure; he locks himself away in a tower with the girl, "consumed by love." Soon he is called away to battle, leaving the doll in the care of his mother. The queen ignores the macabre creature -- until a letter arrives warning her of the prince's impending return. Quickly she calls for her chambermaids and commands them to clean the neglected corpse. They do so, spilling water in their haste, badly staining the maiden's dress. The queen thinks quickly. "Take off the dress! We'll have another one made, and my son will never know." As they loosen the laces, the maiden returns to life, confused and alarmed. The queen hears her story with sympathy, dresses the girl in her own royal clothes, and then, oddly, hides the girl behind lock and key when the prince comes home. He immediately asks to see his "wife." (What on earth was he doing in that locked room?) "My son," says the queen, "the girl was dead. She smelled so badly that we buried her." He rages and weeps. The queen relents. The heroine is summoned, her story is told, and the two are now properly wed.

The casket is soon found by a prince, who falls in love with the beautiful "doll" and takes the body home with him. "But my son, she's dead!" protests his mother. The prince will not be parted from his treasure; he locks himself away in a tower with the girl, "consumed by love." Soon he is called away to battle, leaving the doll in the care of his mother. The queen ignores the macabre creature -- until a letter arrives warning her of the prince's impending return. Quickly she calls for her chambermaids and commands them to clean the neglected corpse. They do so, spilling water in their haste, badly staining the maiden's dress. The queen thinks quickly. "Take off the dress! We'll have another one made, and my son will never know." As they loosen the laces, the maiden returns to life, confused and alarmed. The queen hears her story with sympathy, dresses the girl in her own royal clothes, and then, oddly, hides the girl behind lock and key when the prince comes home. He immediately asks to see his "wife." (What on earth was he doing in that locked room?) "My son," says the queen, "the girl was dead. She smelled so badly that we buried her." He rages and weeps. The queen relents. The heroine is summoned, her story is told, and the two are now properly wed.

Author and fairy tale scholar Veronica Schanoes notes, "Many fairy tales and myths concern the fantasy that if you love someone enough, you can bring them back from the dead. In fairy tales, that effort is usually successful and the wish is fulfilled: Sleeping Beauty wakes up; Snow White revives; the older sisters in Fitcher's Bird are resuscitated; the heroine recovers her prince in East of the Sun, West of the Moon; etc. But in myth, the stories tend to be more poignantly about the limits of human love and its inability to defeat death: Gilgamesh can't bring back Enki; Achilles can't bring back Patroclus; Theseus cannot rescue Pirithous; Orpheus fails; and even though she is a goddess, Demeter's love for Persephone can only bring her back part-way."

The fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen often touch on the subject of death, but the ones that address the subject directly are among his most pious and sentimental, better suited to Victorian tastes than they are to ours today. One of the more interesting of them is The Story of a Mother, in which Death knocks on a woman's door and takes her beloved son away. The distraught woman determines to follow, and makes her long, weary way to Death's realm. There, she finds a greenhouse filled to the bursting with flowers and trees of all kinds -- each one representing a single life somewhere on earth. When Death arrives, she tricks him into giving back the life of her son -- but Death shows her the future and the terrible life her child will lead. She knows then that his death is god's will, and a mercy, and she is at peace.

Andersen's very best tale about death has deservedly become a classic. The Nightingale is the story of a Chinese Emperor and a bird with an exquisite song. The Emperor dotes on the bird for awhile, then replaces the humble, faithful creature with a golden mechanical replicate...until the night that Death comes for him, squatting heavily on his chest:

Opening his eyes he saw it was Death who sat there, wearing the Emperor's crown, handling the Emperor's gold sword, and carrying the Emperor's silk banner. Among the folds of the great velvet curtains there were strangely familiar faces. Some were horrible, others gentle and kind. They were the Emperor's deeds, good and bad, who came back to him now that Death sat on his heart.

"Don't you remember?" they whispered one after the other. "Don't you remember���?" And they told him of things that made the cold sweat run on his forehead.

"No, I will not remember!" said the Emperor. "Music, music, sound the great drum of China lest I hear what they say!"

But nothing will drown out the whispers. The Emperor's mechanical bird sits silent, for there is no one to wind it up. Then the real nightingale arrives, having heard wind of the emperor's plight. He sings so beautifully that the phantoms fade and even Death stops to listen. The nightingale bargains for the emperor's life, and Death departs.

Death underlines the magical stories that make up The Arabian Nights, for it is the reason Scheherazade spins her tales: to save herself and her sister. "There's something almost Trickster-ish about Scheherazade," Midori points out. "She uses storytelling to keep death at bay -- but she does so by never finishing the tale in the morning, where its conclusion might signal the arrival of her own promised death. Instead, she leaves off at a cliffhanger, which requires yet another night to finish -- and then promptly starts another tale before the night is over. The moment of completion (the rehearsal of 'death') does come -- but in the middle of the night, which enables her to resurrect herself in another tale before the sun rises. So it's as though each story produces its own moment of death, followed by a new work that resurrects the storyteller. It's like trickster's death in the Coyote stories, a death that is never final. He's always returning, repeating a movement between death and creation."

It fairy tales, too, death is not always final; it's sometimes an agent of change and transformation. Sleeping Beauty in her death-like sleep, Snow White in her glass coffin: this is a mere rehearsal for death, and out of it new life is created (literally, in the case of Sleeping Beauty, who gives birth to twins as she lies asleep and wakes as they try to suckle). In Trickster myths, the connection between death and life, destruction and creation, is usually made clear; but in fairy tales too, death is not always an ending, or at least not just an ending. It can have within it the seeds of new life, of change, of transformation ��� which is what these tales, at their most basic level, are so often all about.

"Death in folklore, when not associated with the more violent sorts of death-dealers, is generally rather ambiguous," Midori concludes, "which is of course the nature of death itself. At some point we must accept and embrace it, because it is the fate of us all -- yet we resist it (at least at certain times in our lives) because of its finality. Death figures in folk and fairy tales allow us to personalize our contact with death long enough to confront it, to argue with it, to pit our wits against it . . . and perhaps, if we are lucky, to finally make peace with it."

This is fertile ground for fantasy writers, some of whom have already made good use of it: Ursula K. Le Guin in The Farthest Shore, Jane Yolen in Cards of Grief, Rachel Pollack in Godmother Night, Neil Gaiman in his Sandman comics, etc.. But there's still much territory to explore as the fantasy genre ages and matures... and as we fantasy writers and artists age and mature along with it.

For an excellent discussion of death in fantasy literature, I highly recommend "Imagined Afterlives," a new essay by Katherine Langerish.

The marvelously macabre photographs today are by the American photographer Daniel Vazquez, who lives and works in the Bay Area of California. Please visit his "American Ghoul" website and Instagram page to see more of his stunning work (and to purchase his prints).

Pictures: The photographs above are by Daniel Vazquez; all rights reserved by the artist. The illustrations are: "Godfather Death" by Johnny B. Gruelle (1880-1938) and the Death tarot card by Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951). Words: Many thanks to Midori Snyder for her contribitions to this essay. (Go here to read some of her own essays on myth and folklore, highly recommended.) All rights to the text above reserved by the authors.

Pictures: The photographs above are by Daniel Vazquez; all rights reserved by the artist. The illustrations are: "Godfather Death" by Johnny B. Gruelle (1880-1938) and the Death tarot card by Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951). Words: Many thanks to Midori Snyder for her contribitions to this essay. (Go here to read some of her own essays on myth and folklore, highly recommended.) All rights to the text above reserved by the authors.

October 26, 2016

The tales we tell

As I mentioned yesterday, author and scholar Marina Warner has been exploring the importance of Story in the lives of refugees, migrants and other displaced peoples in her timely and valuable cross-border project Stories in Transit. The following passage comes from Dame Warner's "Stories in Transit: Telling the Tale in Times of Conflict":

"���In order to have a story���, comments Lorraine Daston, in order to become historical, ���one must have listeners, with whom one shares a common language, fellow feeling, and an understanding of the home left behind. All these things are denied the modern exiles. At most, a journalist or a Red Cross official takes down a telegraphic version of the catalogue of horrors suffered: a sound byte, not a story.��� She goes on to ask, ���What does it take to have a story, a life that makes sense in a senseless world of forced wandering that shatters all continuity? ��� Even the luckiest exiles, those who are able to settle and prosper in a new land, must face the bitter truth that their native tongue will no longer be spoken gladly by their own grandchildren, that their stories will be increasingly lost in translation���.

"���In order to have a story���, comments Lorraine Daston, in order to become historical, ���one must have listeners, with whom one shares a common language, fellow feeling, and an understanding of the home left behind. All these things are denied the modern exiles. At most, a journalist or a Red Cross official takes down a telegraphic version of the catalogue of horrors suffered: a sound byte, not a story.��� She goes on to ask, ���What does it take to have a story, a life that makes sense in a senseless world of forced wandering that shatters all continuity? ��� Even the luckiest exiles, those who are able to settle and prosper in a new land, must face the bitter truth that their native tongue will no longer be spoken gladly by their own grandchildren, that their stories will be increasingly lost in translation���.

"Cultural and literary transmission of myth and story is a process of constant, deep and fruitful metamorphosis, acts of memory against forgetting, acts of bonding against forces of splitting. These metamorphoses take place in dialogue with written texts, but are not constrained by writing: indeed mobile narratives are a dynamic feature of contemporary culture because the internet and digital technologies have opened up a vast arena for varieties of performance, recitation, speech, combining sound, image, voice. The traffic in mobile myths is rising with the strong and omnipresent return of acoustics to communication -- we have entered a hybrid era, in which the oral is no longer placed in opposition to the literate. When Borges commented that he had always imagined Paradise 'will be a kind of library���, it is interesting to remember that the great writer was himself blind for a great part of his life, and he was read to -��� books for him were sounded.

"The United Nations has started to respond to the immaterial needs of displaced peoples -- that cultural heritage -- connectedness and belonging established through memory and imagination, might be a human right has become what is being called the new frontier. Such compass points are formed, often, not by material goods, but by immaterial artefacts: by words spoken, recited, performed, sung, and remembered. They may be preserved in books but they also travel by other ethereal conduits, especially in the age of the internet when they are at one and the same time vigorous and fragile. They may inhere in...things, containers of memories and history. In 2003, Unesco declared protection for intangible cultural heritage, but the dominant implication was that this applied principally to the culture of unlettered peoples -- to orature. This needs adjusting -- highly literate civilisations also flourish through oral -- performed, played -- channels of transmission."

Indeed they do, and this is an important point to be championing.

The extraordinary artwork today is by my friend and neighbor Virginia Lee.

Virginia grew up in Chagford, studied Illustration at Kingston University, and worked for a time on The Lord of the Rings trilogy in New Zealand (sculpting architectural statues and merchandise for the films). She has since illustrated several children���s books, including The Frog Bride (a retelling the Russian fairy tale), Persephone: A Journey from Winter to Spring, The Secret History of Mermaids and Hobgoblins. She has also illustrated cards for The Storyworld, a toolkit for the imagination, and The Enchanted Lenormand Oracle. For her personal work, she says: "I use my own visual language to explore themes of transformation and connection to nature, creating realms where deep aspects of the psyche are embodied in folkloric characters and revealed in the mythic landscape."

To see more of her work, visit Virginia's website, blog, and Etsy shop.

The passage above is from "Stories in Transit: Telling the Tale in Times of Conflict" (Museo Internazionale delle Marionette G. Pasqualino, Palermo, Italy, January 2016). You can read the full piece online here (pdf). Virginia Lee's images, from top to bottom, are: "The Diplomat," "Life in a Nutshell," "Minotaur," "Three Hares Tor," and "Tides of Emotion." All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and artist.

October 25, 2016

Listen. Listen.

In celebration of Peter Oswald's new book Sonnets of various sizes (Shearsman, 2016), my husband Howard has filmed him delivering each poem at Aller Park, on the Dartington estate, where Peter is Artist-in-Residence. These little films are scheduled to appear once a week on the "Sonnet Feed" of Peter's website, released every Friday afternoon.

The first two sonnets are online now...and they are simply gorgeous.

As devoted as I am to the printed word, I love listening to these pieces, sinking back into that old, old oral tradition...

Peter Oswald (for those who don't know his work already) is an award-winning playwright & poet, performer & storyteller...and co-founder, with Howard, of the new Foxhole Theatre company, dedicated to exploring verse and mask drama in all its varied forms.

Peter's plays have been produced at the Globe and the National, as well as in the West End, on Broadway, and around the world. He was Writer-in-Residence at the Shakespeare's Globe from 1998 to 2005 (under the mentorship of Mark Rylance, for whom he wrote two leading roles); and at Dartington from 1997 to 1998 -- resuming the latter position in conjunction with his wife, poet Alice Oswald, in 2016-2017. Last month, Peter and Alice took part in Stories in Transit, a project organized by Marina Warner in Palermo, Italy, exploring storytelling in relation to refugees, migrants, and other displaced peoples.

In addition to his other theatre work, Peter also gives solo performances of story-poems based on sagas and folktales at theatre venues and literary festivals in UK and abroad. His delightful rendition of Three Folktales (from the Italian tradition) will be of particular interest to the Mythic Arts community...as well as the Viking saga he is currently working on with Howard. (But more about that anon.)

Here's a short taste of Three Folktales:

October 24, 2016

Thank you...

...to everyone who has kept the conversation here going while I've been away, or ill, or otherwise distracted. I always read the comments under each posr, even when I fall behind on answering..and I'm grateful to all of you who take the time to write, kindly carrying the discussion forward when I can't carry it myself.

The illustration above is by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939).

October 23, 2016

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I'd like to follow up last week's music (classical compositions inspired by birds) with Hanna Tuulikki's Away With the Birds, a project exploring the mimesis of birds in Gaelic folk songs. Tuulikki is an English/Finnish composer based in Edinburgh, known for creating interdisciplinary works rooted in myth, folk history and the natural world. In the video below, she discusses the genesis of Away With the Birds:

"The idea for the work grew out of an interest in music from around the world, noticing that in cultures where people have an intimate connection with the land they are also good mimics of the sounds around them, and their music seems to grow directly from this relationship. I believe our music, and even our language, originated and evolved from our listening to the sounds of the animate landscape, or what eco-philosopher David Abram calls the more-than-human world. So I began a journey looking for this kind of sound-making process closer to home..."

The Wildscreen event where Tuulikki was speaking was "a celebration of natural storytelling" held in Glasgow, Scotland last May. In another video from the same event, Scottish singer Julie Fowlis performs "An Ron/Ann an Caolas Ododrum," a traditional Gaelic song about seals. She's accompanied by Donald Shaw (from Capecaille), backed up by clips from the BBC series Hebrides.

To end with, here's Julie Fowlis again, performing "Smeorach Chlann Domhnaill,"  which includes the following words (in translation):

which includes the following words (in translation):

A mavis, I, on a mountain top,

Watching sun and cloudless skies.

Softly I approach the forest

I shall live in otherwise.

If every bird praises its own land,

Why then should not I?

Land of heroes, land of poets...

The abundant, hospitable, estimable land.

The image at the top of this post is by Russian surrealist photographer Katerina Plotnikova. The seal photograph is from the Hebrides tv series. The drawings are by Carson Ellis and Honor Appleton (1879-1951). More avian folk songs can be found in "Going to the Birds." For avian folklore:"When Stories Take Flight."

October 20, 2016

On the shores of mystery

Here's one more passage from Kathleen Dean Moore's Wild Comfort: The Solace of Nature, which (as you may have guessed by now) I highly recommend:

"Some people suggest that science is the enemy of the sacred. This puzzles me. I suppose the argument is that the more we understand or think we understand, the smaller the realm of mystery becomes; under the hot light of scientific knowledge, the sacred warps and shrinks, like Styrofoam in flames. But this argument won't work because mystery is infinite, the only natural resource that humans can't exhaust in this giant fire sale we call an economy.

"The physicist Chet Raymo thinks of scientific understanding as an island in a sea of mystery. The larger the island, the longer its coastline -- that area where the deep sea of what we don't understand slaps and smacks at the edge of what we think we know, a rich place of bright water and dark, fecund smell.

"If so, then this is our work in the world: to pull on rubber boots and stand in this lively, dangerous water, bracing against the slapping waves, one foot on stone, another on sand. When one foot slips and the other sinks, to hop awkwardly to keep from filling our boots.

"To laugh, to point, and sometimes to let this surging, light-flecked mystery wash into us and knock us to our knees, while we sing songs of celebration through our own three short nights, our voices thin in the darkness."

The passage above is from "The Time for the Singing of Birds" by Kathleen Dean Moore, published in her essay collection Wild Comfort (Trumpeter/Shambhala, 2010). The poem in the picture captions is an untitled shaman song by the 19th century Inuit oral poet Uvavnak, translated by Jane Hirshfield, from Women in Praise of the Sacred (HarperCollins Publishers Inc, 1994). All rights reserved by the authors. The photographs were taken on Devon/Cornwall north coast.

The passage above is from "The Time for the Singing of Birds" by Kathleen Dean Moore, published in her essay collection Wild Comfort (Trumpeter/Shambhala, 2010). The poem in the picture captions is an untitled shaman song by the 19th century Inuit oral poet Uvavnak, translated by Jane Hirshfield, from Women in Praise of the Sacred (HarperCollins Publishers Inc, 1994). All rights reserved by the authors. The photographs were taken on Devon/Cornwall north coast.

October 19, 2016

Floating on the pulse of the Earth

After a week's disconnection from the Internet and the news headlines, it was disheartening to return home again and find the world in worse shape then ever. The UK government's xenophobic pronouncements are truly frightening, the American election is even worse...while climate change roars on and refugees prepare for another hard winter, homeless and unwanted. I'd come back to Chagford feeling calm and restored by a week of solitude in nature, yet the tide of dreadful news threatened to sweep me back into a state of despondency. The following passage by Kathleen Dean Moore steadied me, however, reminding me that hope and despair, happiness and sorrow, are cyclical things, like nature itself. There will be good news, there will be bad news, and we carry on: fighting the good fight and finding ways to make beauty, even out of the darkest of materials.

"I don't know what despair is," writes Moore," if it's something or nothing, a kind of filling up or an emptying out. I don't know what sorrow does to the world, what it adds or takes away. What I think I do know now is that sorrow is part of the Earth's great cycles, flowing into night like cool air sinking down a river course. To feel sorrow is to float on the pulse of the Earth, the surge from living to dying, from coming into being to ceasing to exist.

"Maybe this is why the Earth has the power over time to wash sorrow into a deeper pool, cold and shadowed. And maybe this is why, even though sorrow never disappears, it can make a deeper connection to the currents of life and so connect, somehow, to sources of wonder and solace. I don't know.

"And I don't know what gladness is or where it comes from, this splitting open of the self. It takes me surprise. Not an awareness of beauty and mystery, but beauty and mystery themselves, flooding into my mind suddenly without boundaries. Can this be gladness, to be lifted by that flood?"

Yes. Yes it can.

The passage is above is from the introduction to Wild Comfort: The Solace of Nature, essays by Kathleen Dean Moore (Trumpeter/Shambhala, 2010); all rights reserved by the author.

The passage is above is from the introduction to Wild Comfort: The Solace of Nature, essays by Kathleen Dean Moore (Trumpeter/Shambhala, 2010); all rights reserved by the author.

October 18, 2016

Earth's gifts

I started writing a post this morning about my adventures during my week away from Chagford, and it seems to be turning into an essay on me, so it's going to be a day or two before its done. It's coming, I promise.

I've returned home to a garden (or "yard," as we Americans say) that has turned decisively to autumn, dressed in rusty reds and golden yellows, the air smelling of wood smoke and apples. When the weather permits, I've been working outdoors, soaking in the sun before the winter is upon us. The Hound is glad to have me back, and is sticking even closer to my side than usual...as if I might slip away again if she lets me out of her sight.

I've returned home to a garden (or "yard," as we Americans say) that has turned decisively to autumn, dressed in rusty reds and golden yellows, the air smelling of wood smoke and apples. When the weather permits, I've been working outdoors, soaking in the sun before the winter is upon us. The Hound is glad to have me back, and is sticking even closer to my side than usual...as if I might slip away again if she lets me out of her sight.

One of the books I have on the go

at the moment is Wild Comfort: The Solace of Nature, an essay collection by naturalist, educator, and philosopher Kathleen Dean Moore. I started reading Wild Comfort half a year ago, and for some reason, I didn't stick with it then -- I can't imagine why, because this time I can't put it down. Books are like that sometimes. They open to you when they're ready, and not before.

"The earth offers gift after gift," writes Moore, "life and the living of it, light and the return of it, the growing things, the roaring things, fire and nightmares, falling water and the wisdom of friends, forgiveness. My god, the forgiveness, time, and the scouring tides. How does one accept gifts as great as these and hold them in the mind?

"Failing to notice a gift dishonors it, and deflects the love of the giver. That's what's wrong with living a careless life, storing up sorrow, waking up regretful, walking unaware. But to turn the gift in your hand, to say, this is wonderful and beautiful, this is a great gift -- this honors the gift and the giver of it. Maybe this is what [my friend] Hank has been trying to make me understand: Notice the gift. Be astonished at it. Be glad for it, care about it. Keep it in mind. This is the greatest gift a person can give in return.

" 'This is your work,' my friend told me, 'which is a work of substance and prayer and mad attentiveness, which is the real deal, which is why we are here.' "

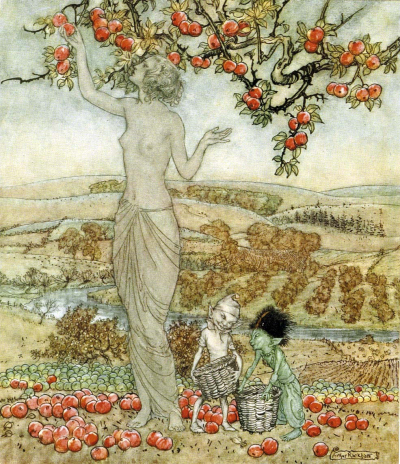

The passage by Kathleen Dean Moore above is from "Burning Garbage on an Incoming Tide," published in Wild Comfort: The Solace of Nature (Trumpeter Books/Shambhala, 2010). The poem in the picture captions is from Poetry magazine (January, 1985). All rights reserved by the authors. The illustration is "Pomona," the Roman goddess of fruit and nut trees, by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939).

The passage by Kathleen Dean Moore above is from "Burning Garbage on an Incoming Tide," published in Wild Comfort: The Solace of Nature (Trumpeter Books/Shambhala, 2010). The poem in the picture captions is from Poetry magazine (January, 1985). All rights reserved by the authors. The illustration is "Pomona," the Roman goddess of fruit and nut trees, by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939).

October 17, 2016

Tunes for a Monday Morning

My apologies for being away from Myth & Moor for longer than expected. I spent a week of solitude in a very beautiful place (more about that tomorrow), then came down with the flu shortly after my return. I'm on the mend now, however, and back to a regular studio schedule (touch wood).

I was surrounded by birds and birdsong during my week away from home, so this morning's music is an homage to all of our winged neighbors....

Above: The Rotterdam Philharmonic performs "Cantus Arcticus, Op.61" by Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara (1928-2016). Rautavaara passed away just a few months ago, but his gorgeous and rather mystical music lives on. In this piece, the conventional instrumental soloist is replace with taped birdsong from Arctic Finland.

Below: "The Lark Ascending" by English composer Ralph Vaughn Williams (1872-1958), performed by Scottish violinist Nicola Benedetti. Williams' composition was inspired by George Meredith's poem of the same name.

Below: "The Blackbird," a short piece for flute and piano by French composer Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992), performed by Kenneth Smith on flute and Matthew Schellhorn on piano. Messiaen was a passionate ornithologist as well as a musician, and spent a great deal of time in the wild studying birdsong.

And last: "The Birds," a suite for small orchestra by Italian composer Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936), inspired by 17th & 18th century works attempting to render bird song and movement as musical notations. The first three movements of the suite are performed below by the Academic Chamber Soloists Prague.

I wish I could also offer you something from John Harvey's Bird Concerto with Pianosong, but I can't find any performances of it online at all -- so I can only urge you to seek out London Sinfonietta's recording of this stunning piece of music if you don't know it already.

I also recommend "The Wild Dove, Opus 110," a favorite piece of mine by Czech composer Anton��n Dvo����k, beautifully performed by the Symfonieorkest Vlaanderen here. And American composer John Luther Adams' spare and magical "Songbirdsong," which you'll find here.

You might also be interested in the BBC documentary Why Birds Sing, available on YouTube in six parts starting here.

The illustration above is "Green Willow" by Warwick Goble (1862-1943). The photographs are from Wiki Commons, photographers credited in the picture captions.

September 30, 2016

I'm off...

I will be away from home for the next week, and then back to the studio on Monday, October 10. These are the words I'd like to leave you with, from an interview with Anthony Doerr:

"Life is wonderful and strange...and it���s also absolutely mundane and tiresome. It���s hilarious and it���s deadening. It���s a big, screwed-up morass of beauty and change and fear and all our lives we oscillate between awe and tedium. I think stories are the place to explore that inherent weirdness; that movement from the fantastic to the prosaic that is life....

"Life is wonderful and strange...and it���s also absolutely mundane and tiresome. It���s hilarious and it���s deadening. It���s a big, screwed-up morass of beauty and change and fear and all our lives we oscillate between awe and tedium. I think stories are the place to explore that inherent weirdness; that movement from the fantastic to the prosaic that is life....

"What interests me -- and interests me totally -- is how we as living human beings can balance the brief, warm, intensely complicated fingersnap of our lives against the colossal, indifferent, and desolate scales of the universe. Earth is four-and-a-half billion years old. Rocks in your backyard are moving if you could only stand still enough to watch. You get hernias because, eons ago, you used to be a fish. So how in the world are we supposed to measure our lives -- which involve things like opening birthday cards, stepping on our kids��� LEGOs, and buying toilet paper at Safeway -- against the absolutely incomprehensible vastness of the universe?

"How? We stare into the fire. We turn to friends, bartenders, lovers, priests, drug-dealers, painters, writers. Isn���t that why we seek each other out, why people go to churches and temples, why we read books? So that we can find out if life occasionally sets other people trembling, too?"

Indeed.

The quote by Anthony Doerr is from an interview in Wag's Review (Issue 8). The illustrations above are by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) and E.M. Taylor (1906-1964).

The quote by Anthony Doerr is from an interview in Wag's Review (Issue 8). The illustrations above are by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) and E.M. Taylor (1906-1964).

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers