Gary Allen's Blog, page 28

December 21, 2010

The Final Food Site Update (of 2010)

Here, at the very end of the year, with all sorts of holidays to occupy our attention, there's no time for procrastinating. We either get the update newsletter out, now, or continue setting a bad example for ourselves by sending it sometime in January.

While it seemed, not long ago, that our appetites would never return -- they have, just in time for one or two more gastronomic onslaughts. In the interest of seasonal good will, we offer this little bit of advice: The Science of Your Hangover, in which Kate Hilpern explains the how, why and escape route from post-holiday hell. It won't help you recover from all of the season's over-indulgences, but it may minimize the after-effects of one of them.

Regular subscribers to our updates newsletter receive these updates from our blog, Just Served, directly -- but there is much more on the blog that isn't sent automatically. We understand that many (OK, most) folks have better things to do with their time than wade through countless unwanted e-missives, so we avoid adding ours to that pile. However... should you feel an inexplicable craving for exactly the sort of self-indulgent claptrap we periodically post, you can satisfy that urge at Just Served.

Leitesculinaria is still in the process of reposting, sometimes with shiny new updates and edits, some of our older articles. The entire list of our currently-posted LeitesCulinaria articles (some twenty or so) is available here.

For hard-core addicts of our stuff (assuming such unlikely beings exist), Marty Martindale's Food Site of the Day has been completely redesigned, and has returned to posting A Quiet Little Table in the Corner -- an ever-changing index of our writings on the web.

As always, we conclude our monthly peregrinations with some presumably appropriate selections from On the Table's culinary quote pages. This month, alas, is no exception.

"There is a remarkable breakdown of taste and intelligence at Christmastime. Mature, responsible grown men wear neckties made of holly leaves and drink alcoholic beverages with raw egg yolks and cottage cheese in them." P.J. O'Rourke

"In my experience, clever food is not appreciated at Christmas. It makes the little ones cry and the old ones nervous." Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.

And, as any writer will tell you,

"Do give books for Christmas. They're never fattening..." Lenore Hershey

Gary

January, 2011

PS: If you encounter broken links, changed URLs -- or know of wonderful sites we've missed -- please drop us a line. It helps to keep this resource as useful as possible for all of us. To those of you who have suggested sites -- thanks, and keep them coming!

PPS: If you wish to change the e-mail address at which you receive these newsletters, or otherwise modify the way you receive our postings, go here.

PPPS: If you've received this newsletter by mistake, and/or don't wish to receive future issues, you have our sincere apology and can have your e-mail address deleted from the list immediately. We're happy (and continuously amazed) that so few people have decided to leave the list -- but, should you choose to be one of them, let us know and we'll see that your in-box is never afflicted by these updates again. You can unsubscribe here .

----the new sites----

20 Great TED Talks for Total Foodies

(these tasty twenty-minute talks range from insectivory to sustainability to urban planning to the versatility of pigs)

2,400-year-old Soup Found

(Chinese archaeologist Liu Daiyun found bones and soup in one bronze pot, and a wine-like liquid in another)

Chinese Noodle Dinner Buried for 2,500 Years

(archaeologists discovered noodles and moon-cake-like baked goods among ancient grave goods)

City's Food History on Exhibit

(restaurant memorabilia, from 1849 to 2010, an exhibition at San Francisco's Main Library)

Classical Cider

(Rachel Laudan muses on cider, Puvis de Chavannes, and the institution of Frenchness in France)

Divided We Eat

(Lisa Miller's Newsweek article on class differences in American eating habits)

Food & Foodways

(an index of available titles from the Center for the Study of the American South, at the University of North Carolina)

Foods, Most of Them Scary

(another site that proves that our nostalgia for foods of the past is terribly mistaken)

Guide to Spanish Cured Meats, A

(an annotated slide show from Saveur)

Historic Restaurant Photographs

(an archive of over 700 pictures compiled by The Museum of the City of New York)

In a Nutshell

(Noreen Malone's "brief history of nutcrackers," in Slate)

Kapeleion

("Casual and Commercial Wine Consumption in Classical Greece," Clare F. Kelly-Blazeby's PhD thesis; a PDF)

Maple Recipe Collection

(amassed by the University of Vermont)

Menus: The Art of Dining

(a digitized collection, history of menus and restaurant, the artists who created the menus and the technologies involved in their production)

New Front in the Culture Wars, The: Food

(article by Brent Cunningham and Jane Black, in The Washington Post, on how food choices are being used as political fodder)

Nuts…Their History

(part of the website of the Leavenworth Nutcracker Museum))

Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency, The (FFA)

(a clearing house for everything concerning the fishing industry in the region)

Wijnanda Deroo: Inside New York Eateries

(press release for an exhibit of photographs at NY's Robert Mann Gallery)

World of Breakfast, A

(article, in Saveur, comparing breakfast traditions in several countries, and some of the historical reasons for them)

----how-to blogs----

Blogs about blogging -- their writing, design, photography, promotion, and ethics -- can help us become better, and possibly more successful, writers (i.e., having more people read our stuff). Here are a few recent favorites:

3 Thanksgiving Cookbook Authors Dish on Their Craft

10 Things Every Cookbook Publisher Should Know

Food Blog Alliance

Food Blog Forum

Food Bloggers Unite

Let Your Story and Identity Shine Through, says Cookbook Publisher

Ten Blogging Mistakes I Learned in Year One

----still more blogs----

Another Wine Blog

Appetite

Creole Notes

Dining Alternative, The

Drankster

Drinkster

Hosemaster of Wine

In the Kitchen and on the Road with Dorie

Jane Black

Nectar Tasting Room and Wine Blog

Restaurant Club

Suburban Wino

Sweet Beet, The

----that's all for now----

Except, of course, for the usual legal mumbo-jumbo and commercial flim-flam:

Your privacy is important to us. We will not give, sell or share your e-mail address with anyone, for any purpose -- ever. Nonetheless, we will expose you to the following irredeemably brazen plugs:

Our books, The Resource Guide for Food Writers, The Herbalist in the Kitchen, The Business of Food: Encyclopedia of the Food And Drink Industries, and Human Cuisine can be ordered through the Libro-Emporium.

Here endeth the sales pitch(es)...

...for the moment, anyway.

___

"The Resource Guide for Food Writers, Update #123" is protected by copyright, and is provided at no cost, for your personal use only. It may not be copied or retransmitted unless this notice remains affixed. Any other form of republication -- unless with the author's prior written permission -- is strictly prohibited.

Copyright (c) 2011 by Gary Allen.

Published on December 21, 2010 14:14

November 21, 2010

Food Sites for December 2010 (almost, anyway)

It's the very end of November, not one of our favorite months -- even though it does include the National Day of Overindulgence (the pleasure of which, alas, is immediately canceled out by interminable football games suffered in dyspeptic silence). As many of you will be similarly occupied, we thought it might be a good idea to send this newsletter out early.

We're realists: The odds are against any of you wanting to read about food for quite a while.

Last month, Let Them Eat Crepes (edited by Melissa Doffing and Susan Koefod) was published. It contains several homages to those wonderful French pancakes -- including one, "A Bunch of the Boys Were Whooping It Up," by yours truly. Please don't hold that against this lovely little book, or keep you from ordering a copy here or at the book's website. [a disclosure of sorts: we have no financial stake in the sales of this book; our sole involvement was in writing the aforementioned essay]

Regular subscribers to our updates newsletter receive these updates from our blog, Just Served, directly -- but there is much more at the blog that isn't sent automatically. We understand that many (OK, most) folks have better things to do with their time than wade through countless unwanted e-missives, so we won't add ours to that pile. However... should you feel an inexplicable craving for exactly the sort of self-indulgent claptrap we periodically post, you can satisfy that urge at Just Served.

Leitesculinaria is still in the process of reposting, sometimes with shiny new updates and edits, some of our older articles. The entire list of our currently-posted LeitesCulinaria articles (twenty, so far) is available here.

For hard-core addicts of our stuff (assuming such unlikely beings exist), Marty Martindale's Food Site of the Day has been completely redesigned, and has returned to posting A Quiet Little Table in the Corner -- an index of our writings on the web.

As always, we end our monthly sermon with some selections from On the Table's culinary quote pages. This month, a month that contains a superfluity of superfluity, when excess exceeds all reasonable limits, clearly requires no more -- hence there is but one quotation:

Gary

December, 2010

PS: If you encounter broken links, changed URLs -- or know of wonderful sites we've missed -- please drop us a line. It helps to keep this resource as useful as possible for all of us. To those of you who have suggested sites -- thanks, and keep them coming!

PPS: If you wish to change the e-mail address at which you receive these newsletters, or otherwise modify the way you receive our postings, go here.

PPPS: If you've received this newsletter by mistake, and/or don't wish to receive future issues, you have our sincere apology and can have your e-mail address deleted from the list immediately. We're happy (and continuously amazed) that so few people have decided to leave the list -- but, should you choose to be one of them, let us know and we'll see that your in-box is never afflicted by these updates again. You can unsubscribe here.

----the new sites----

15 Food & Cooking Myths, Busted

(a selection of ideas from Harold McGee's Keys to Good Cooking)

Food in the 'Hood

(food history articles by Joel Denker, author of The World on a Plate: A Tour Through the History of America's Ethnic Cuisine)

Food Science Central

("…free articles on many topics in food science, food technology and nutrition")

In Praise of Fast Food

(Tom Philpott's essay, in Grist, on the omnipresence of fast food throughout history and across cultures)

Market Assistant

("Containing a Brief Description of Every Article of Human Food Sold in the Public Markets of the Cities of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn; Including the Various Domestic and Wild Animals, Poultry, Game, Fish, Vegetables, Fruits, &C, &C. with Many Curious Incidents and Anecdotes;" complete text of Thomas F. De Voe's 1867 book)

Nourish

(site of an organization whose mission it is to educate the public about our food systems)

Science Behind Why We Love Ice Cream, The

(Wall Street Journal report on work being done at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia)

Wessels Living History Farm, The

(site of a museum of 1920s farming, with sections on later periods, and various resources -- including podcasts on different aspects of farm life)

----how-to blogs----

Blogs about blogging -- their writing, design, photography, promotion, and ethics -- can help us become better, and maybe even more successful, writers ("success" being a relative, and highly-variable, notion). Here are a few of our favorites:

As Pretty as Egg Salad: a Food Styling Post

Authors, Social Media and the Allure of Magical Thinking

Food Photography: How to Shoot Ugly Food

How Right is the Customer who Blogs?

Should I Tweet?

Social (Marketing) Network, The: Can an Analog Girl Thrive in the Digital World?

----still more blogs----

Afghan Cooking Unveiled

Ecocentric

Edible Geography

Edible Living

Jefferson's Table

Lucid Food

menuism

Vintage Cookbooks

----that's all for now----

Except, of course, for the usual legal mumbo-jumbo and commercial flim-flam:

Your privacy is important to us. We will not give, sell or share your e-mail address with anyone, for any purpose -- ever. Nonetheless, we will expose you to the following irredeemably brazen plugs:

Our books, The Resource Guide for Food Writers, The Herbalist in the Kitchen, The Business of Food: Encyclopedia of the Food And Drink Industries, and Human Cuisine can be ordered through the Libro-Emporium.

Here endeth the sales pitch(es)...

...for the moment, anyway.

___________

"The Resource Guide for Food Writers, Update #122" is protected by copyright, and is provided at no cost, for your personal use only. It may not be copied or retransmitted unless this notice remains affixed. Any other form of republication -- unless with the author's prior written permission -- is strictly prohibited.

Copyright (c) 2010 by Gary Allen.

We're realists: The odds are against any of you wanting to read about food for quite a while.

Last month, Let Them Eat Crepes (edited by Melissa Doffing and Susan Koefod) was published. It contains several homages to those wonderful French pancakes -- including one, "A Bunch of the Boys Were Whooping It Up," by yours truly. Please don't hold that against this lovely little book, or keep you from ordering a copy here or at the book's website. [a disclosure of sorts: we have no financial stake in the sales of this book; our sole involvement was in writing the aforementioned essay]

Regular subscribers to our updates newsletter receive these updates from our blog, Just Served, directly -- but there is much more at the blog that isn't sent automatically. We understand that many (OK, most) folks have better things to do with their time than wade through countless unwanted e-missives, so we won't add ours to that pile. However... should you feel an inexplicable craving for exactly the sort of self-indulgent claptrap we periodically post, you can satisfy that urge at Just Served.

Leitesculinaria is still in the process of reposting, sometimes with shiny new updates and edits, some of our older articles. The entire list of our currently-posted LeitesCulinaria articles (twenty, so far) is available here.

For hard-core addicts of our stuff (assuming such unlikely beings exist), Marty Martindale's Food Site of the Day has been completely redesigned, and has returned to posting A Quiet Little Table in the Corner -- an index of our writings on the web.

As always, we end our monthly sermon with some selections from On the Table's culinary quote pages. This month, a month that contains a superfluity of superfluity, when excess exceeds all reasonable limits, clearly requires no more -- hence there is but one quotation:

"SATIETY, n. The feeling that one has for the plate after he has eaten its contents, madam." Ambrose Bierce

Gary

December, 2010

PS: If you encounter broken links, changed URLs -- or know of wonderful sites we've missed -- please drop us a line. It helps to keep this resource as useful as possible for all of us. To those of you who have suggested sites -- thanks, and keep them coming!

PPS: If you wish to change the e-mail address at which you receive these newsletters, or otherwise modify the way you receive our postings, go here.

PPPS: If you've received this newsletter by mistake, and/or don't wish to receive future issues, you have our sincere apology and can have your e-mail address deleted from the list immediately. We're happy (and continuously amazed) that so few people have decided to leave the list -- but, should you choose to be one of them, let us know and we'll see that your in-box is never afflicted by these updates again. You can unsubscribe here.

----the new sites----

15 Food & Cooking Myths, Busted

(a selection of ideas from Harold McGee's Keys to Good Cooking)

Food in the 'Hood

(food history articles by Joel Denker, author of The World on a Plate: A Tour Through the History of America's Ethnic Cuisine)

Food Science Central

("…free articles on many topics in food science, food technology and nutrition")

In Praise of Fast Food

(Tom Philpott's essay, in Grist, on the omnipresence of fast food throughout history and across cultures)

Market Assistant

("Containing a Brief Description of Every Article of Human Food Sold in the Public Markets of the Cities of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn; Including the Various Domestic and Wild Animals, Poultry, Game, Fish, Vegetables, Fruits, &C, &C. with Many Curious Incidents and Anecdotes;" complete text of Thomas F. De Voe's 1867 book)

Nourish

(site of an organization whose mission it is to educate the public about our food systems)

Science Behind Why We Love Ice Cream, The

(Wall Street Journal report on work being done at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia)

Wessels Living History Farm, The

(site of a museum of 1920s farming, with sections on later periods, and various resources -- including podcasts on different aspects of farm life)

----how-to blogs----

Blogs about blogging -- their writing, design, photography, promotion, and ethics -- can help us become better, and maybe even more successful, writers ("success" being a relative, and highly-variable, notion). Here are a few of our favorites:

As Pretty as Egg Salad: a Food Styling Post

Authors, Social Media and the Allure of Magical Thinking

Food Photography: How to Shoot Ugly Food

How Right is the Customer who Blogs?

Should I Tweet?

Social (Marketing) Network, The: Can an Analog Girl Thrive in the Digital World?

----still more blogs----

Afghan Cooking Unveiled

Ecocentric

Edible Geography

Edible Living

Jefferson's Table

Lucid Food

menuism

Vintage Cookbooks

----that's all for now----

Except, of course, for the usual legal mumbo-jumbo and commercial flim-flam:

Your privacy is important to us. We will not give, sell or share your e-mail address with anyone, for any purpose -- ever. Nonetheless, we will expose you to the following irredeemably brazen plugs:

Our books, The Resource Guide for Food Writers, The Herbalist in the Kitchen, The Business of Food: Encyclopedia of the Food And Drink Industries, and Human Cuisine can be ordered through the Libro-Emporium.

Here endeth the sales pitch(es)...

...for the moment, anyway.

___________

"The Resource Guide for Food Writers, Update #122" is protected by copyright, and is provided at no cost, for your personal use only. It may not be copied or retransmitted unless this notice remains affixed. Any other form of republication -- unless with the author's prior written permission -- is strictly prohibited.

Copyright (c) 2010 by Gary Allen.

Published on November 21, 2010 19:05

October 25, 2010

Food Sites for November 2010

Gill Farm, Hurley, NY

Gill Farm, Hurley, NYBy November, the last of the harvests are in (at least here in the Hudson Valley), and those who practice certain outdoor sports turn their minds from fishing to the pursuit of other game. The time for light salad-like repasts is over, and we crave hearty, slow-cooked, deep-flavored dishes -- and light amusements give way to more substantial pastimes. Some of us actually read.

Books, even.

Regular subscribers to our updates newsletter receive these updates from our blog, Just Served, directly -- but there is much more at the blog that isn't sent automatically. We understand that many (OK, most) folks have better things to do with their time than wade through countless unwanted e-missives, so we won't add ours to that pile. However... should you feel an inexplicable craving for exactly the sort of self-indulgent claptrap we periodically post, you can satisfy that urge at Just Served. Last month, we added "Carbonara" -- the apotheosis of bacon, but feel free to choose something from the archives -- such as the seasonally-appropriate "Thanksgiving (Special Holiday Report)."

Leitesculinaria is still in the process of reposting, sometimes with shiny new updates and edits, some of our older articles. The entire list of our currently-posted LeitesCulinaria articles (twenty, so far) is available here.

For hard-core addicts of our stuff (assuming such unlikely beings exist), Marty Martindale's Food Site of the Day has been completely redesigned, and has returned to posting A Quiet Little Table in the Corner -- an index of our writings on the web.

As always, we end our monthly sermon with some selections from On the Table's Culinary Quote pages. This month is no exception (and, for some reason, they all feature a specific avian species):

"Coexistence... what the farmer does with the turkey -- until Thanksgiving." Mike Connolly

"It was dramatic to watch [my grandmother] decapitate [a turkey] with an ax the day before Thanksgiving. Nowadays the expense of hiring grandmothers for the ax work would probably qualify all turkeys so honored with "gourmet" status." Russell Baker

"On Thanksgiving, you realize you're living in a modern world. Millions of turkeys baste themselves in millions of ovens that clean themselves." George Carlin

"TURKEY, n. A large bird whose flesh when eaten on certain religious anniversaries has the peculiar property of attesting piety and gratitude. Incidentally, it is pretty good eating." Ambrose Bierce

"Turkey is undoubtedly one of the best gifts that the New World has made to the Old." Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

"Turkey takes so much time to chew. The only thing I ever give thanks for at Thanksgiving is that I've swallowed it." Sam Greene

"TURKEY: This bird has various meanings depending on the action in your dream. If you saw one strutting and/or heard it gobbling, it portends a period of confusion due to instability of your friends or associates. However, if you ate it, you are likely to make a serious error in judgment." The Dreamer's Dictionary

"You first parents of the human race...who ruined yourself for an apple, what might you have done for a truffled turkey?" Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

Gary

November, 2010

PS: If you encounter broken links, changed URLs -- or know of wonderful sites we've missed -- please drop us a line. It helps to keep this resource as useful as possible for all of us. To those of you who have suggested sites -- thanks, and keep them coming!

PPS: If you wish to change the e-mail address at which you receive these newsletters, or otherwise modify the way you receive our postings, go here.

PPPS: If you've received this newsletter by mistake, and/or don't wish to receive future issues, you have our sincere apology and can have your e-mail address deleted from the list immediately. We're happy (and continuously amazed) that so few people have decided to leave the list -- but, should you choose to be one of them, let us know and we'll see that your in-box is never afflicted by these updates again. You can unsubscribe here.

----the new sites----

10 Historical Figures Who Were Total Foodies

(expected ones, like Marcel Proust and Catherine de Medici, but also Charles Darwin and Nelson Mandela)

2500 Years of Caviar History

(a tiny taste of luxury foodstuff)

Amaranth

(Purdue University's factsheet on a new world plant that has provided grain and greens since ancient times)

Antique Gin Bottles

(multiple galleries featuring bottles, labels, seals and other ephemera from several collectors)

Appalachian Cook Book

(where else can you find a recipe for Stuffed Possum?)

Caviar, the Incredible, Edible Egg

(a detailed look at the subject, with information about recent advances in caviar production in the US)

Comprehensive Apple Variety List

(twelve page description and use chart)

Culinary Arts Colleges

(a descriptive guide to culinary arts colleges and universities in the US, with links to each program; alphabetical by state)

Examination of Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols

(an in-progress study conducted by the Institute of Medicine, part of the National Academy of Sciences)

Greater Midwest Foodways Alliance

(site "...celebrating, exploring and preserving unique food traditions and their cultural contexts in the American Midwest")

Science of Menu Layout, The

(if you're in the restaurant business, you probably already know this -- or you should; if not, you'll never read a menu the same way again)

Squash Named from an Indian Word

(not just etymology, but a history of these New World vegetables)

Traditional Bajan Recipes

(a few recipes from Barbados)

UMass Cranberry Station

(site dedicated to protecting the cranberry crop, with the help of specialists in "plant pathology, entomology, environmental physiology, plant nutrition/cultural practices, weed science/integrated pest management, and floriculture")

Wild Game Cookery: Venison

(a PDF factsheet from the University of Minnesota's Extension Service)

----how-to blogs----

Blogs about blogging, and about the writing process in general, can help us become better, and maybe even more successful, writers (whatever "success" means to each of us). Here are a few of our favorite blogs for bloggers about the business, meaning, and process of food writing and photography:

Annoying Wine Words: Five Overused Terms That Tell Us Nothing About Wine!

Artificial Light Food Photography

My Food Writing Trap

New Rules for Judging "Quality" in Published Content, The

This month we're featuring several posts by Dianne Jacob (author of Will Write for Food and the blog of the same name:

Blogging Just For Love? No Way

Exclusive Offer! Only 1000 Food Bloggers Qualify

Is Lower Pay for Web Writing Defensible?

Outrageous Blogger Request, and the Outcome

Putting the "Free" in Freelance

----still more blogs----

American Menu, The

Ann Arbor Cooks

Barbara's Eastern European Food Blog

Cheese Is Alive

Cheese Poet

It's Not You, It's Brie

Kitchen Retro

Madame Fromage

Noshstalgia

Save the Deli

Wrightfood

----that's all for now----

Except, of course, for the usual legal mumbo-jumbo and commercial flim-flam:

Your privacy is important to us. We will not give, sell or share your e-mail address with anyone, for any purpose -- ever. Nonetheless, we will expose you to the following irredeemably brazen plugs:

Our books, The Resource Guide for Food Writers, The Herbalist in the Kitchen, The Business of Food: Encyclopedia of the Food And Drink Industries, and Human Cuisine can be ordered through the Libro-Emporium.

Here endeth the sales pitch(es)...

...for the moment, anyway.

__________________________________

"The Resource Guide for Food Writers, Update #121" is protected by copyright, and is provided at no cost, for your personal use only. It may not be copied or retransmitted unless this notice remains affixed. Any other form of republication -- unless with the author's prior written permission -- is strictly prohibited.

Copyright (c) 2010 by Gary Allen.

Published on October 25, 2010 07:48

October 13, 2010

Carbonara

Ristorante Piperno, Rome

Ristorante Piperno, RomeIn 1981, Calvin Trillin suggested, in The New Yorker, that Thanksgiving would be improved by skipping the usual dried-out turkey -- and substituting succulent spaghetti carbonara. Of course, he also wanted to live on Santo Prosciutto, a mythical Caribbean island steeped in Italian culinary traditions.

What, exactly, was his turkey-replacing dish? Waverley Root's classic The Food of Italy (1971), gives carbonara but sixteen words ('though he does call it "a particular favorite"). The Dictionary of Italian Food & Drink defines it as:

pasta (usually spaghetti) with egg yolks, Guanciale, Pecorino Romano or (less traditionally) Parmesan cheese, and black pepper. Variations from these few ingredients are common, but they are not called carbonara, at least not in Italy. Cream is not an ingredient of true carbonara; it is an aid to inexperienced cooks who have trouble getting the eggs to the right consistency without it.

The recipe for this Roman specialty is remarkably simple, yet its ingredients need some explanation.

Guanciale is seasoned and air-cured -- but unsmoked -- Italian bacon, cut from the cheek of the hog (as opposed the belly, in American bacon, or tenderloin, in Canadian bacon) It is similar to pancetta, but its texture is firmer. Think proscuitto, but with much more luxurious fat.

Pecorino Romano is a sharp grating cheese made from sheep's milk (unlike the sweeter cow's milk Parmigiano). While it is made in Lazio (home to Rome), it is also made elsewhere -- however its style is definitely Roman.

Whole eggs can be used, but can easily become scrambled (which is why beginners sometimes resort to adding cream); egg yolks alone will yield a perfectly creamy result, and golden color, when cooked only by the pasta's heat.

The name "carbonara" suggests a number of folk etymologies that have become attached to the dish. The Dictionary of Italian Food & Drink eliminates one of them: "Carbonara is the name of a town, near Bari, and is not related to pasta alla carbonara."

One of these pseudo-histories claims that the name comes from the wives of coal miners or charcoal makers (just as "meuniere" refers to a French miller's wife). This is somewhat suspect, as neither mining nor charcoal-making are major businesses in Rome.

Another suggests that the dish was a favorite of the Carbonari, an Italian political secret society. This, while suspect, is more appealing, since it mirrors the history of the Slow Food movement (that began among Italian leftists, who -- being Italian first, and communist second -- always wanted to know the best places to eat when meeting with fellow travelers).

Yet another version of the story says that the dish originated when Allied forces entered Rome during World War II. Supposedly, their rations included bacon (highly doubtful) and powdered eggs (probable, but not very appetizing) -- and welcoming Romans invented the dish to make use of these ingredients. Creating wonderful dishes from whatever is available is very Italian, but the story doesn't ring completely true. Spam would have been more likely than bacon -- and pasta with spam and eggs sounds more Monty Python than cucina rustica.

The time period is probably accurate, though, since the dish was first mentioned in The New York Times in the July 12, 1954 issue (never one to be the first to mention a new trend, and nine years for the good gray lady is just fashionably late). The article's title, "News of Food; When in Rome, You Eat Magnificent Meals in Simple Restaurants," is generally good advice (at least it was when we went searching for good carbonara). One thing we discovered was that the guanciale was always cut exactly the same way: in little strips, one and a half inches long.

Whatever the true story of the dish's origins, the likeliest explanation of the name is the presence of specks of black pepper in the dish that look like bits of coal or charcoal.

As for Trillin's plan to delete turkey from his family's Thanksgiving menu -- they tried it just once (his wife, Alice, found the experience too depressing to repeat). But good stories don't die easily, and Trillin had to tell it, again and again, during succeeding holiday seasons. Once, he even heard himself, on his car radio, expounding the virtues of spaghetti carbonara -- while driving to a friend's house to partake in a traditional Thanksgiving turkey dinner.

Spaghetti alla Carbonara

In the past few years, spaghetti carbonara has been subject to all sorts of little "improvements," often adding garnishes that only diminish the purity of the original dish. Here's our recipe, roughly based on one by Marcella Hazan:

Ingredients

1/2 pound guanciale (or pancetta, if guanciale can't be found)

2 Tablespoons olive oil

1 Tablespoon butter

3 cloves garlic, peeled and crushed

1/4 Cup dry white wine (such as Orvieto or Est! Est! Est!)

2 Tablespoons salt

8 egg yolks (or 3 whole eggs)

3/4 Cup pecorino romano, freshly grated

1/2 teaspoon black pepper, coarsely ground

Method

1. Cook garlic in butter and oil until golden, then discard garlic.

2. Slice guanciale into small strips, one and a half inches long, a quarter inch wide, and an eighth of an inch thick. Fry guanciale in garlic-scented fat until browned, Add wine and boil for a couple of minutes, scraping any browned bits from bottom of pan. Set pan aside (but do not drain away any of the delicious fat).

3. Cook spaghetti in at least a gallon of rapidly-boiling salted water until just tender, but still firm.

4. In large serving bowl, beat egg yolks (or whole eggs), cheese and pepper.

5. Reheat guanciale and its fat. Toss drained pasta in pan, add egg mixture to coat evenly (adding a bit of the water the pasta cooked in, if the mixture seems too dry). Serve immediately.

Published on October 13, 2010 12:40

September 28, 2010

Food Sites for October 2010

Pumpkin patch, New Paltz, NY

It's practically October. There's an unfamiliar chill in the air, and an occasional whiff of apple-wood smoke, that sharpen the appetite for slow-cooked meals and warm sweet spices -- cinnamon, nutmeg, mace and cloves. Flavors we haven't craved in months.

Regular subscribers to our updates newsletter receive these updates from our blog, Just Served, directly -- but there is much more that doesn't appear, unbidden, like fly-by-night offers of unwanted mortgages and miracle enhancers of our physiological attributes.

Should you have nothing more worthwhile to do, and feel a craving for more of the sort of bloviating in which we periodically indulge, you can satisfy that urge at our blog. Last month's new entries included: "Eighty-Six" -- some speculation about a familiar piece of restaurant jargon ; and "Tasting Vertically," an updated version of an article about food history that originally appeared in The Valley Table magazine. No physiological enhancements should be expected from any of these offerings.

Leitesculinaria has posted our new piece, "The History of Chicken Fingers," -- which, oddly enough, actually features some historical stuff about chicken fingers. The site has just reposted a new and improved version of our piece on "Burrata di Andria Cheese." The site is still in the process of reposting, sometimes with shiny new updates and edits, some of our older articles. The entire list of our currently-posted LeitesCulinaria articles (twenty, so far) is available here.

For hard-core addicts of our stuff (in the event that such unlikely beings exist), Marty Martindale's Food Site of the Day has been completely redesigned, and has returned to posting A Quiet Little Table in the Corner -- an ever-changing index of our writings on the web.

As always, we end our monthly sermon with some selections from On the Table's culinary quote pages. This month is no exception:

"Not on morality, but on cookery, let us build our stronghold: there brandishing our frying-pan, as censer, let us offer sweet incense to the Devil, and live at ease on the fat things he has provided for his elect!" Thomas Carlyle

"In all professions without doubt but certainly in cooking. One is a student all his life." Fernand Point

"The only real stumbling block is fear of failure. In cooking you've got to have a what-the-hell attitude." Julia Child

and one non-culinary quote, just for perspective:

"Have you ever observed that we pay much more attention to a wise passage when it is quoted than when we read it in the original author?" Philip G. Hamerton

Gary

October, 2010

PS: If you encounter broken links, changed URLs -- or know of wonderful sites we've missed -- please drop us a line. It helps to keep this resource as useful as possible for all of us. To those of you who have suggested sites -- thanks, and keep them coming!

PPS: If you wish to change the e-mail address at which you receive these newsletters, or otherwise modify the way you receive our postings, go here .

PPPS: If you've received this newsletter by mistake, and/or don't wish to receive future issues, you have our sincere apology and can have your e-mail address deleted from the list immediately. We're happy (and continuously amazed) that so few people have decided to leave the list -- but, should you choose to be one of them, let us know and we'll see that your in-box is never afflicted by these updates again. You can unsubscribe here .

----the new sites----

At the Greek Table

("Your Guide to the Greek Lifestyle;" wines and recipes)

Consider Nutmeg

(Oliver Thring's post on the troubled history of one spice; more of his articles are available here )

Counter Space: Design and the Modern Kitchen

(an exhibit at NYC's Museum of Modern Art; September 15, 2010–March 14, 2011. Make sure to click on "View Exhibition Site" -- there's a gallery of 22 stills from films featuring kitchens)

Cuisine du Quebec

(recipes, chefs and ingredients from francophone Canada; in French, naturellement)

Food for Thought

("…an examination and celebration of the ways food helps to define Indiana's culture, considering food in the context of history, law, politics, science, the arts, religion, ethnicity and our place in the world;" from the Indiana Humanities Council)

Guide to Tropical Fruit in South America, A

(J. Kenji Lopez-Alt's annotated slide show of 30 fruits, from anon to zapote)

History of Macaroni, The

(Clifford Wright's definitive essay on the subject of pasta's origins)

Hot Pepper, The

(a gardener's and cook's forum for every aspect of genus Capsicum, and related hot stuff)

How Women Reshaped the Modern Kitchen

(Elaine Louie's New York Times article about "Counter Space: Design and the Modern Kitchen," an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art)

MFK Fisher: Poet of the Appetites

(hour-long video of a symposium held at NYC's New School)

Seasoned Meat Forums, The

(recipes, tips & techniques, curing & smoking, and FAQs -- for making sausages and jerky)

Society for the Study of Ingestive Behavior, The (SSIB)

("...an organization committed to advancing scientific research on food and fluid intake and its associated biological, psychological and social processes")

Sorry, You Absolutely Cannot Eat These Animals in New York State

(just in case you wanted to know what is NOT on the menu)

Turkish-Cypriot Cuisine

(recipes from Cyprus)

----how-to blogs----

Blogs about blogging -- and about the writing process in general -- can help us become better, and possibly more successful, writers. Bloggers, nowadays, need to be able to do more than write about food -- they must often be able to match their text with complementary photos. Here are a few of our favorite blogs for bloggers (as is obvious, this month has been a busy one, with a couple of major confabs of food writers):

Action Verbs and Similes Make Food Writing Sing

Food Photography

Food Photography: How to Shoot Soup

Future of Food Writing at the International Food Blogger Conference, The

Giving Recipes Away a Big Subject at IFBC

LiveBlogging from the Professional Foodwriters Symposium at the Greenbrier

Day One

Day Two

Day Three

Day Four

Unfortunate Truths of Food Blogging, The

Wanna Write a Cookbook? -- Make Those Recipe Intros Tasty

----still more blogs----

Feasting on Art

Giusto Gusto

Historic Cookery

Nancy Baggett's Kitchen Lane

Veggie Belly

----that's all for now----

Except, of course, for the usual legal mumbo-jumbo and commercial flim-flam:

Your privacy is important to us. We will not give, sell or share your e-mail address with anyone, for any purpose -- ever. Nonetheless, we will expose you to the following irredeemably brazen plugs:

Our books, The Resource Guide for Food Writers, The Herbalist in the Kitchen, The Business of Food: Encyclopedia of the Food And Drink Industries, and Human Cuisine (and a bunch of others) can be ordered through the Libro-Emporium.

Here endeth the sales pitch(es)...

...for the moment, anyway.

__________________________

"The Resource Guide for Food Writers, Update #120" is protected by copyright, and is provided at no cost, for your personal use only. It may not be copied or retransmitted unless this notice remains affixed. Any other form of republication -- unless with the author's prior written permission -- is strictly prohibited.

Copyright (c) 2010 by Gary Allen.

Published on September 28, 2010 07:09

September 18, 2010

Tasting Vertically

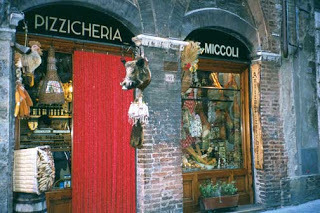

A salumeria in Siena, where cinghiale (wild boar) is a local specialty.

A salumeria in Siena, where cinghiale (wild boar) is a local specialty.Wine tastings can be informal gatherings or they can be highly structured events designed to teach us to recognize the subtle differences between closely related wines. Typical examples of the latter might consist of comparisons between several wines of one region or varietal, such as the latest vintage of wines from Bordeaux, or Pinot Noirs from the Pacific Northwest. These are called "horizontal tastings." Tastings can also be arranged vertically, perhaps comparing all the vintages of Chateau Haut Brion for the last fifty years. The two methods reflect different kinds of learning and differing degrees of sophistication.

Everyone knows that, over the last forty years or so, there has been a rapid and worldwide rise in interest in cooking and eating. This has led to an incredible expansion of choices of foods, cookbooks, restaurants, cooking equipment and ingredients, representing an ever-growing list of ethnicities and cultures. In a sense, we have all been involved in the broadest of possible horizontal tastings.

It sometimes seems that no corner of the world, no matter how remote or obscure, has already been explored for (or looted of) its culinary treasures. In our insatiable quest for new tastes, and textures, and aromas, we rush from one ethnic market (or continent) to another, always imagining that somewhere, in a place no other foodie has yet traveled, there is a magical dish that will transform our lives forever.

The problem with this approach, of course, is that, in our haste, we don't experience the depth of connection that indigenous peoples have with their own foods. Our broad, but shallow, tasting experiences, by their very nature, deprive us of the fulfillment we seek.

Perhaps that is why we're beginning to see a different approach to the search for culinary meaning, one that promises to provide the depth of understanding, the depth of flavor we've been craving. Having gone as far as we can, horizontally, in all directions, we have but one choice: taste vertically.

We do this by acquiring a taste for history. When we know where our food comes from, not just in the fashionable sense of eating locally-grown foods, but in understanding how it got to be the way it is: when a dish was created, under what technological, ethnic, geographical, political and religious circumstances, we begin to develop that "depth of connection" we missed during our earlier "horizontal" explorations.

In recent years, there has been an explosion of interest in vertical tasting. It can be seen in several forms: culinary historical societies, websites devoted to food history, libraries devoted to historic culinary collections, historical cookbooks, and countless articles in food magazines like this one.

Serious foodies, in almost every major city in the US, have formed culinary historical societies. Important ones include the Chicago Culinary Historians, the Culinary Historians of Ann Arbor, the Culinary Historians of Boston, the Culinary Historians of New York, the Culinary Historians of Washington, DC, the Culinary Historians of Atlanta, the Historic Foodways Society of Delaware Valley, and the Houston Culinary Historians. Similar groups, like Oldways and Slow Food, study and try to preserve ancient food practices, ingredients and dishes before they are lost to commercially-motivated "progress."

The Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA) is not specifically about food, but when its members re-enact medieval events, they are particularly careful to produce all their meals as authentically as possible, and they have been responsible for a number of translations of early cookbooks (both in printed form and, incongruously enough, as web-based recipe databases). Similar groups re-enact Revolutionary War battles (such as the annual Burning of Kingston) and Civil War events. These groups meticulously reproduce the dishes and preparations of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, respectively.

There are, literally, hundreds of websites devoted to food history. Here are a selected few:

Clifford A. Wright

Food History

Food History News

Food Timeline History Notes

Gherkins & Tomatoes

History and Legends of Favorite Foods

The Old Foodie

A few that are specific to my own area (New York's Hudson Valley) include:

Brooklyn Brewery

Research Resources

Libraries with significant historic culinary collections include:

Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America

The Culinary History Collection at Newman Library

The Connecticut Historical Society

Johnson and Wales College Library

The Public Libraries of Chicago, Los Angeles, and Milwaukee

Nestle Library

Rare Book and Special Collections Division of the Library of Congress

Special Collections (University of California, Davis)

The Department of Special Collections: Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center

In our own area, New York Academy of Medicine Library has an excellent collection of very old and rare cookbooks, as does the New York Public Library and the Bobst Library (New York University). The Conrad Hilton Library at The Culinary Institute of America, in Hyde Park, has one of the biggest and finest collections in the country.

A few periodicals are dedicated to food history (such as the newsletters of the various culinary historians' groups mentioned earlier) but mainstream magazines, like Saveur, routinely carry articles on food history.

So many historical cookbooks have been published in recent years that it would be impossible to list them all. A few that can tell us something about how we got to eat the way we do here, in the Hudson Valley, are worthy of mention.

Peter Rose, together with Donna Barnes, curated an exhibit at the Albany Institute of History and Art. It was called Matters of Taste: Food and Drink in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art and Life. The exhibit has closed, but the beautiful and informative catalog (that contains a small recipe book) is still available. Regular readers of The Valley Table know that Ms. Rose specializes in the study of Dutch foodways and their influence in the Hudson Valley.

Ian Kelly, an actor and food historian, has written Cooking for Kings: The Life of Antonin Careme, the First Celebrity Chef. French cuisine may, at first, seem unrelated to the way we eat today, but virtually all serious restaurants (and restaurateurs) draw on the organization and techniques of the classic French kitchen. Further, no matter how we may feel about the situation, it is almost impossible to imagine a world without celebrity chefs, and Careme was the prototype for all of them.

Historian Sandra Sherman (formerly at the University of Arkansas), has given us Fresh from the Past: Recipes and Revelations from Moll Flander's Kitchen -- a detailed look at the foods and lifestyles of eighteenth-century England, a time when cookbook-publishing was booming. In fact, the first cookbook published in America (1742) was a reprint of Eliza Smith's 1727 book, The Compleat Housewife; or, Accomplished Gentlewoman's Companion; the first truly American cookbook wasn't published until 1796: Amelia Simmons' American Cookery; or The Art of Dressing Viands, Fish, Poultry, and Vegetables, and the Best Modes of Making Pastes, Puffs, Pies, Tarts, Puddings, Custards, and Preserves, and All Kinds of Cakes, from the Imperial Plumb to Plain Cake, Adapted to this Country, and All Grades of Life. Sherman's book gives us a very good idea of what our Founding Fathers would have expected to see on their tables.

A few years back, Francine Segan published Shakespeare's Kitchen. She looked at the kind of dishes prepared in England four hundred years ago (the dishes our earliest colonials would have known well) and updated them for modern tastes. Later, she did the same with even older ancestors of our cooking in The Philosopher's Kitchen: Recipes from Ancient Greece and Rome for the Modern Cook. In both books, she includes the original recipes, so we can compare -- in a perfect example of the vertical tasting.

Of course, if you really want to go back as far as possible in your search for the roots of our cuisine, you might want to read Jean Bottero's The Oldest Cuisine in the World: Cooking in Mesopotamia. Carefully examining and analyzing the inscriptions on three five-thousand-year-old clay tablets in the Beinecke Library at Yale, Dr. Bottero was not able to recreate actual recipes, but many of the ingredients and methods are oddly, and reassuringly, familiar.

_________________________

This (somewhat altered) article was first published in the March/May 2005 issue of The Valley Table, and appears here by permission of the publishers.

Published on September 18, 2010 06:22

August 30, 2010

food sites for September 2010

Remember when foods were still seasonal -- not shipped in from some distant clime -- and you looked forward to the year's first sweet corn, the first sun-warmed tomato?

It's September and the farm stands are starting to run out of local sweet corn; tomatoes are still around in all colors and sizes -- but heaps of squashes and the earliest apples have appeared. We've had a few cool days that suggest Autumn is on the way, and the prospect of cooking indoors -- cooking the sorts of things that take a long time and involve a hot oven -- actually sounds enjoyable.

Regular subscribers to our updates newsletter receive these updates from our blog, Just Served, directly -- but there is much more that doesn't appear, unbidden, like offers of unwanted credit cards, in the mail.

Should you have nothing more worthwhile to do, and feel a craving for more of the sort of bloviating in which we periodically indulge, you can satisfy that urge at our blog. Last month's included: "Hot Wings" -- a touching father-son reminiscence involving irresponsible consumption of capsaicin; "Pink Kashmiri Tea," -- featuring some idle speculation on the inexplicable (or, at least, inexplicable by us); "What's Eating You?" -- a hint of the way cannibalism appears in our everyday speech; and "Food Controversies in Context" -- a somewhat revised version of a talk given at the New School, 20 February 2008.

Leitesculinaria is still in the process of reposting, sometimes with shiny new updates and edits, some of my older articles. The entire list of our currently-posted LeitesCulinaria articles (nineteen, so far) is available here.

As always, we end our monthly sermon with some vaguely seasonal comments from On the Table's culinary quote pages. This month is no exception:

"[The (apple) pie should be eaten] while it is yet florescent, white or creamy yellow, with the merest drip of candied juice along the edges (as if the flavor were so good to itself that its own lips watered!), of a mild and modest warmth, the sugar suggesting jelly, yet not jellied, the morsels of apple neither dissolved nor yet in original substance, but hanging as it were in a trance between the spirit and the flesh of applehood... then, O blessed man, favored by all the divinities! Eat, give thanks, and go forth, 'in apple-pie order!'" Henry Ward Beecher

"As the days grow short, some faces grow long. But not mine. Every autumn, when the wind turns cold and darkness comes early, I am suddenly happy. It's time to start making soup again." Leslie Newman

"If you want to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first create the universe." Carl Sagan

"The first zucchini I ever saw I killed it with a hoe." John Gould

Gary

September, 2010

PS: If you encounter broken links, changed URLs -- or know of wonderful sites we've missed -- please drop us a line. It helps to keep this resource as useful as possible for all of us. To those of you who have suggested sites -- thanks, and keep them coming!

PPS: If you wish to change the e-mail address at which you receive these newsletters, or otherwise modify the way you receive our postings, go here.

PPPS: If you've received this newsletter by mistake, and/or don't wish to receive future issues, you have our sincere apology and can have your e-mail address deleted from the list immediately. We're happy (and continuously amazed) that so few people have decided to leave the list -- but, should you choose to be one of them, let us know and we'll see that your in-box is never afflicted by these updates again. You can unsubscribe here.

----the new sites----

50 Best Cookbooks of All Time, The

(a briefly annotated list from London's Guardian; from Bartolomeo Scappi 's Opera dell'Arte del Cucinare to David Chang's Momofuku, 'though not in chronological order; the top ten are here)

100 Top Restaurant Review Sites For Restaurateurs

(diners, today, increasingly rely upon electronic reviews in choosing a restaurant; Chef Mark Garcia provides links to some of the best review sites)

Anise Liqueurs

(the family of drinks found all around the Mediterranean: absinthe, arak, chinchon, ouzo, pastis, raki and sambuca)

Australian Culinary Lingo

(how to tell your lilly-pilly from your yabby, mate)

Born Round

(site promoting Frank Bruni's book of the same name, but filled with his musings on all things gastronomic)

Brief History of the Birthday Cake, A

(blogger Kathryn McGowan traces the classic dessert to two technological developments, and tests the oldest birthday cake recipe in print)

Bush Tucker

(Australian for wild foods: birds, fish, fruits, flowers, herbs, insects, mammals, mushrooms, reptiles, spices and vegetables)

Chile-Head

(hot stuff: chile botany, chemistry, recipes, growing tips, reviews of sauces, methods of preparation and storage, and more)

Favorite Wine and Drinking Quotes

(compiled by Natalie Maclean; there are more here)

Flavors of Rome

(Carol Coviello-Malzone's guide to visiting, and eating in, the Eternal City; with recipes, of course)

Food for Thought

(Ann Landi's article, in Art News, on the way "portion sizes in depictions of the Last Supper have grown" over time)

Great Recipes from Famous Movies

(Saveur article featuring 21 dishes, from Eat Pray Love's cacio e pepe to Mostly Martha's gnocchi)

I Need Coffee

(articles on all aspects of the subject, an obsession bordering on the jitters)

Is Food the New Sex?

(Mary Eberstadt's essay, in Stanford University's Policy Review, on the changing face of morality in an environment where people can have as much as they want of either)

Let Us Now Praise the Great Men of Junk Food

(if we are what we eat, this brief chronology of certain iconic foods tells us more than we want to know about ourselves)

Pleasures of Truly Wild Wild Rice, The

(reprint, at Salon, of Ed Behr's article that originally appeared in The Art of Eating; additional Behr articles are posted at the same site)

Primary Sources for "The First Thanksgiving" at Plymouth

(the only first-hand accounts of the original Thanksgiving, from Pilgrim Hall Museum)

Swineweb

(news, research and trade articles on everything about the pork industry)

Tricks of the Trade

(article in The Age on how menu design steers customers to higher-profit items)

Turkish Coffee: Rich in Flavour and Tradition

(history of, and traditions associated with, the tiny intense cups of sweetened coffee)

----changed URLs----

Origins and Ancient History of Wine, The

----how-to blogs----

Blogs about blogging -- and about the writing process in general -- can help us become better, and possibly more successful, writers. Here are this month's favorites:

Just Exactly What is Worthwhile About Food Writing?

You blog too much. Here's one big idea that can help.

----still more blogs----

Comestibles

Field to Feast

Food and Drink

Food Blogga

Memorie di Angelina

Playing with Fire and Water

RasaMalaysia

Sausage Debauchery

Stuffed Nation

Tea and Cookies

----that's all for now----

Except, of course, for the usual legal mumbo-jumbo and commercial flim-flam:

Your privacy is important to us. We will not give, sell or share your e-mail address with anyone, for any purpose -- ever. Nonetheless, we will expose you to the following irredeemably brazen plugs:

Our books, The Resource Guide for Food Writers, The Herbalist in the Kitchen, The Business of Food: Encyclopedia of the Food And Drink Industries, and Human Cuisine can be ordered through the Libro-Emporium.

Here endeth the sales pitch(es)...

...for the moment, anyway.

________________________

"The Resource Guide for Food Writers, Update #119" is protected by copyright, and is provided at no cost, for your personal use only. It may not be copied or retransmitted unless this notice remains affixed. Any other form of republication -- unless with the author's prior written permission -- is strictly prohibited.

Copyright (c) 2010 by Gary Allen.

Published on August 30, 2010 08:50

August 27, 2010

Food Controversies in Context

Introduction: Kinds of Controversies

Food scandals come in many flavors -- or off-flavors, if you prefer. Consumers get upset when the media tell them about price gouging. News about the combined issues of food quality and food safety (which could be about contamination by pathogens or adulterants, or the over-use of antibiotics and growth hormones) creates mass hysteria. Less intense reactions are generated by news of the environmental impacts of food-production -- such as pollution, over-harvesting, monoculture, genetic modification -- but, for concerned citizens, the outrage is just as real. Other politically active citizens, who may or may not be the same people concerned about environmental issues, take their social responsibility very seriously. The issues of animal rights, working conditions among food producers, exploitation of poor third-world farmers, and the loss of cultural distinctions -- caused by the globalization of mass-produced foods -- are of great concern to such people.

It might be useful to examine a number of these issues, to see what -- if anything -- we can make of them.

Fair Pricing

Is there anyone, anywhere, who likes being ripped off?

Of course not.

When we discover that our favorite candy bar has been diminished by half an ounce, but the price has remained the same -- or, worse, has increased, we are outraged, if only for a moment. We may say that we won't pay it, but -- in the end -- we always do. Every time we hear of price gouging, at every level of the economy, we moan and groan about it, but never really do anything about it.

Has anyone ever successfully boycotted his or her favorite candy bar?

No, in fact the only time anyone seriously complains about price gouging is when they're running for public office or trying to sell their newspapers and magazines. Those among us who are even vaguely savvy realize that this is just another effort to rip us off, so we ignore it. Consequently, we might conclude that fair pricing is not, properly, a scandal.

Depressing, perhaps, but not the kind of thing that gets the public all worked up.

What has roused the public to violence is the perception that the government doesn't care about the well-being of the public stomach. Statements such as Marie Antoinette's famous "Let them eat cake" -- which, by the way, she never said -- are just the sort of thing that leads to the toppling, sometimes literally, of heads of governments. Consequently, prudent governments have worked to prevent that perception from forming in the minds of the governed. The French baguette has long been standardized at 250 grams (just under nine ounces). The price used to be fixed as well, but with the adoption of the Euro, the price now fluctuates -- but at least the consumer knows that the weight of the bread is consistent.

Government standards for staple foods are older than that example -- and the French should have taken a lesson from England's thirteenth century King, Henry III, who signed into law the Assize of Bread and Ale. It standardized the quality, measurement, and pricing for bakers and brewers. Rather than setting uniform weights and prices for bread, the law established fixed ratios between grain prices and the price (and weight) of loaves. Many bakers, afraid of running afoul of the new laws, began giving their customers an extra loaf or roll for every dozen purchased -- giving rise to the practice known as "baker's dozen." The standards for bread were abandoned in the nineteenth century, but the baker's dozen survives as a sign of fair-play and good intentions.

The complicated rules of the Assize of Bread and Ale were, as you might suppose, also applied to brewed beverages. By the sixteenth century, the rules were changed to allow local magistrates to set pricing standards for ale. Of course, there are more ways to cheat a customer than through exorbitant pricing.

Melegueta pepper, or grains of paradise (Amomum Melegueta) -- was used, in the Renaissance, as a cheap substitute for black pepper (Piper nigrum). The adulteration of beer and wine with this spice increased their perceived warmth, and was intended to give the illusion of higher alcoholic strength. Elizabeth the First, in the sixteenth century, loved the taste of melegueta pepper in drinks -- but George the Third, in the eighteenth, banned its use by brewers. He was concerned that its use was disguising weak quaffs. The fines for its illicit use were so great that the spice virtually disappeared in England -- and, eventually, throughout Europe. Today it has reappeared, without larcenous intent, in Sam Adams Summer Ale.

Jan Whittaker, a food writer and consumer historian, summarized the situation: "Economic development …facilitates adulteration. Although it is as old as the history of trade, in its modern manifestations it is often the stepchild of science. Scientific development breeds sophisticated trickery via new preservatives, dyes, and fillers. The conditions that promote adulteration are clear: a rapidly expanding economy and lax government controls, combined with bargain-hungry consumers driving a market for cheap goods."

In a sense, we get what we pay for -- even when we don't know what we're buying.

Food Quality

In the past few years Eric Schlosser's Fast Food Nation and Morgan Spurlock's Super-size Me, have roused the public's concerns over the quality of hamburgers and, indeed, the whole hamburger-based culture in which we seem to live. People have been disgusted by what they've learned about the contents of their burgers. Their outrage has led some fast food chains to post the nutritional content of their products in their places of business (I almost said "restaurants," but the very word stuck in my throat). Needless to say, the information is not very accessible -- it's often hidden away in a corner, and printed in small-enough type to discourage casual readers. The fact, however, is that the nutritional content of the burgers is not the real issue.

What people really want to know, and what such informational posters fail to address, is "what's really in them?"

Every once in a while, rumors drift through the consuming public -- unsettling and unsubstantiated rumors -- that reveal the depth of people's worries about food quality. Urban legends circulate about Kentucky Fried Rat, the scarcity of cats near Chinese restaurants, the percentage of earthworm meat that is legally permissible in mass-produced hamburger meat, or rodent hairs in peanut butter. Most of these stories are either untrue, bigoted, or simply reflect the public's lack of mathematical sophistication. What they do tell us is that people are more than willing to believe the worst when it comes to the provenance of their food. When, not long ago, someone claimed to find a severed finger in a meal at Wendy's, the average American's first reaction was to believe it -- not question the motives of the claimant.

Such claims are indeed scandalous, but what makes them scandalous is our willingness to assume their accuracy. The reason we believe them is that we have been conditioned by factual reporting of such matters in the past. A You-Tube-featured video of diseased cattle being taken into a slaughterhouse in Southern California brought the public's attention to the fact that 143 million pounds of diseased beef had been recalled from the food markets -- the largest recall of beef in our history. The recent recall of millions of fresh eggs is but another example.

The tradition of muckraking journalism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, especially that of Upton Sinclair, created a similar public awareness of the limits of food quality in the American marketplace.

Before the summer of 1905, the quality of American food was monitored by just two men -- the Department of Agriculture's entire Bureau of Chemistry. The Senate had contemplated a Pure Food and Drug bill for three years -- with little enthusiasm. In that year, the editor of Appeal to Reason, sent Upton Sinclair to the Chicago stockyards to chronicle their terrible working conditions -- just the sort of thing that a socialist magazine would want to publish. He spent most of November and December of that year interviewing workers. While there, Sinclair met a man who had worked in Armour's "killing beds." The man had, himself, written an exposé of what he had seen there, but he told Sinclair that "old P.D. Armour had paid him five thousand dollars not to publish it."

Sinclair's series of articles were republished in other magazines, then was then published in book form, in 1906, as The Jungle. The disturbingly squalid book was typical of the muckraking journalism of the day. Sinclair had been a student in New York City in the 1890s -- and his book was an emotionally charged and convincing extension of Jacob Riis's 1890 exposé, How the Other Half Lives.

In The Jungle, the packing plants in Chicago were called "Durham's," but readers all knew they were reading about Armour's plants. The book is ugly, dark and squalid -- and the slaughterhouse scenes were horrific.

The magazine articles and subsequent novel outraged the American public -- not as much about the worker's situation as the sanitary conditions in the plants, and of the plant's products. The popularity of The Jungle caused meat sales to decline so sharply, that President Theodore Roosevelt empowered the Neill-Reynolds Commission to investigate conditions in the nation's food industry.

For the preceding three years, the U.S. Senate had considered a Pure Food and Drug bill, but there had been little public support for it until Sinclair's book appeared. Suddenly it was pushed forward -- in part by the findings of the Neill-Reynolds Commission.

Roosevelt told Sinclair that the commission was able to confirm everything in the book except one particularly graphic scene, in which a worker falls into a vat used for rendering lard. Sinclair confirmed the story, explaining that, "the men who had fallen into lard vats had gone out to the world as Armour's Pure Leaf Lard… the families were paid off and shipped back to Lithuania, or whatever European land they had come from…"

Sinclair's investigation of conditions in Chicago's stockyards and packing plants aroused the wrath of the consuming public and forced the creation of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 and the Beef Inspection Act. The Pure Food and Drug Act, concerned primarily with adulteration, contained only one sentence about food quality (other than issues of undesirable additives). According to Section 7, a food was considered impure, "If it consists in whole or in part of a filthy, decomposed, or putrid animal or vegetable substance, or any portion of an animal unfit for food, whether manufactured or not, or if it is the product of a diseased animal, or one that has died otherwise than by slaughter."

Roosevelt's concern -- combined with the fact that meat sales in the U.S. dropped by 50% in the weeks following The Jungle's release -- was more than enough to lead to the successful passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, and its corollary the Beef Inspection Act. Superficially in the best interest of consumers, the act's penalties for industry violators were light. Industry lobbyists managed to make these acts relatively toothless (a maximum of one year's imprisonment and/or a maximum fine of $500 per violation), these acts did lead to the restructuring of existing agencies, like the Bureau of Chemistry, into what has been known, since 1930, as the Food and Drug Administration. The FDA was created to restore the public's faith in the safety of its food supply systems, rather than force the companies to protect the public well-being.

A massive recall, in 2008, of tainted beef was oddly familiar -- including the USDA's official Recall Release (FSIS-RC-005-2008), which announced Hallmark/Westland Meat Packing Company's voluntary recall of two year's worth of tainted meat as a "Class II" situation. Here's how Class II is defined: "This is a health hazard situation where there is a remote possibility of adverse health consequences from the use of the product." The word "remote" is clearly intended to calm the public's fears about exactly what they've been eating for the last two years. For those who have seen the videos, the official pronouncement is small consolation.

Food Safety

In the fall of 2006, manure from nearby pastures contaminated the water used to irrigate a California spinach farm. Premium-grade, "pre-washed" spinach then found its way into grocery stores and into the salads of health-conscious consumers. Ironically, consumers were not aware that "organic" could mean that the crisp healthy greens on their table could be contaminated with E. coli O157:H7 -- a particularly virulent stain of fecal bacteria that could lead to diarrhea, kidney failure, and even death. Before the month was out, three companies that obtained their spinach from Natural Selections Foods (the California grower and processor of the spinach) announced recalls of their products. According to a December 29th article in USA Today, "Demand for spinach fell to almost nothing in September after the FDA temporarily warned consumers not to eat fresh spinach." Four months later, sales were still down to 37% of what they had been the previous December.

Adulterants, like the grains of paradise mentioned earlier, have long been used to alter the public's perception of a food's quality. They are also used to reduce the cost of the product's manufacture. Pet foods from China have been found to be contaminated with melamine -- a toxic compound that is not only cheap, but causes nutritional analysis to indicate higher levels of protein than are actually in the pet food. The public was, naturally, very upset -- especially when some of their beloved pets sickened and died. The situation did not improve when it was discovered that some pigs raised in California were given the same kind of melamine-tainted feed, and had found their way into the human food chain.

Cases of willful adulteration or unintended contamination can lead to effects on the food industry that are way out of proportion to their initial causes, as consumers will go out of their way to avoid any product that has even a hint of a connection to such scandals.

British cookbook author Robert Kemp Philp wrote in 1861, "Those who desire to obtain good Cayenne Pepper, free from adulteration and poisonous colouring matter, should make it of English chilies." The adulteration he described was not at all unusual. One of the reasons that Absinthe was banned in most countries a few decades later (aside from its alleged hallucinogenic properties and the efforts of crusaders for prohibition) was its frequent adulteration with poisonous copper sulfate.

While we're discussing potent potables, consider the fact that Angostura Bitters no longer contain even traces of angostura bark (Cusparia trifoliata). They did, originally, but nineteenth-century rumors of contamination by strychnine (Strychnos nux-vomica) caused its manufacturers to abandon every part of the Angostura plant but its name.

The first legislation aimed at controlling the use of food additives was enacted in Britain, early in the 19th century, following the work of Frederick Accum. It was intended to prevent food adulteration. In the US, public concern about the safety of bread that was baked outside of the home led New York City to pass the New York Bakeshop Law, setting minimum standards for hygiene. Ironically (and oddly reminiscent of current efforts to limit government interference in business, at the expense of the public), the Supreme Court overturned that law in 1905 -- a year before Upton Sinclair's book came out.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Sylvester Graham -- and a little later, John Harvey Kellogg, sensed that something had gone wrong with American food, but they lacked our scientific perspective. The science of nutrition was still in its infancy. Frederick Hopkins first identified what he called "accessory factors" to nutrition in 1898 -- these compounds would later be called "vitamines" (short for "vital amines), and in 1920 became the "vitamins" we know today. Men like Kellogg and Graham were ready, if not truly able, to formulate nutritional regimens that they believed would lead to good health. They were convinced that the processed foods of the day were responsible for the poor health -- physical, spiritual and moral -- of the American populace. They preached that whole grains, processed as little as possible, were the key to good health.

Both men had enormous impact on American eating habits, in part because of the enthusiasm of their followers. Large numbers of influential people flocked to Kellogg's sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan -- Upton Sinclair among them. The Transcendentalist authors of Concord -- Thoreau, Emerson and Alcott -- were Graham converts who brought his ideas to a wider public than he could ever have achieved on his own. The theories of Kellogg and his competitors (including his own brother Will Keith Kellogg and former patient Charles William Post) led to the American attachment to breakfast cereals, while our notions about whole foods can be traced directly to the coarse whole-wheat flour -- named for its promoter -- that gives us Graham Crackers.

Over-use of Antibiotics and Growth Hormones

Since the first antibiotic -- penicillin -- was discovered in 1928, we have enjoyed a kind of immunity from diseases that have literally plagued us for milennia. However, antibiotics cannot solve all of our health problems; they cannot stop viruses, fungus infections, parasites or environmental illnesses caused by toxins. Even for those diseases that can be successfully treated with antibiotics, there are important concerns of a very different nature. When antibiotics are used improperly -- -either in ineffective dosages, or for too short a period to completely destroy the offending bacteria, the few that remain can develop a tolerance for the drug. Once that happens, the survivors become the dominant form and multiply rapidly, effectively eliminating the drug's usefulness.

This is bad enough when we use antibiotics to treat our own diseases, but it's even worse when we use them to treat the animals we use for food. There are a few reasons why this is so.

First, the public is -- for the most part -- unaware that it is eating small amounts of these antibiotics in the meats it consumes. This is significant because when low doses of the drugs are taken, it gives bacteria a better chance to mutate into drug-resistant forms, so when we do become ill, we have fewer choices of weapons to use against the disease.