Andy Worthington's Blog, page 49

September 8, 2017

EXCLUSIVE: Fears for Long-Term Hunger Striker at Guantánamo: Lawyers Urge Court to Order Independent Medical Examination

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

On Wednesday, in a story that has not been reported elsewhere, the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) filed an emergency motion asking for an independent medical examination and medical records for Sharqawi al-Hajj, a Yemeni held without charge or trial at Guantánamo since September 2004, who, as CCR put it, “was held in secret detention and brutally tortured for over two years” before his arrival at Guantánamo.

CCR submitted an emergency motion after al-Hajj, who recently embarked on a hunger strike, and refused to submit to being force-fed, “lost consciousness and required emergency hospitalization.”

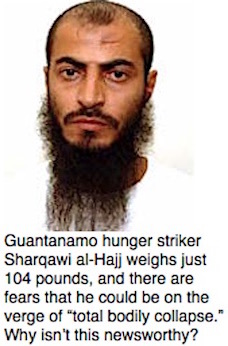

In the most chilling line in their press release about the emergency motion, CCR noted, “As of a recent phone call with his attorneys, Al Hajj was still on hunger strike and weighed 104 pounds.”

As CCR explained, “His hunger strike compounds long-standing concerns about his health. Prior to his detention, Al Hajj was diagnosed with the Hepatitis B virus, an infection affecting the liver that can be life-threatening, and experiences chronic, potentially ominous related symptoms, including jaundice, extreme weakness and fatigue, and severe abdominal pain.”

In a medical declaration submitted in support of the emergency motion, Dr. Jess Ghannam, a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Global Health Sciences in the School of Medicine at the University of California-San Francisco (UCSF), assessed that al-Hajj could be on the verge of “total bodily collapse.”

Dr. Ghannam stated:

In his habeas pleadings, he [al-Hajj] recounts and describes a consistent pattern of torture – both severe physical and mental abuse – before arriving at Guantánamo. His descriptions of torture are consistent with my review of the literature and from my own direct examination of detainees with the same trajectory before arriving at Guantánamo. I have described a condition, referred to a “Guantánamo Syndrome,” where individuals subjected to severe torture in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Jordan develop a wide range of significant medical and psychiatric symptoms and conditions that are debilitating and disabling. The symptoms include sleep difficulties, cognitive difficulties, gastro-intestinal difficulties, chronic pain, chronic headaches, fatigue, and general physical impairment. These symptoms are present in individuals who are not on hunger strikes and can cause severe physical and neuropsychological damage. In the midst of a hunger strike, these symptoms can lead to total bodily collapse and medically irreparable harm. It is my opinion, with reasonable medical probability, that Mr. Hajj may very well be on the precipice of total bodily collapse.

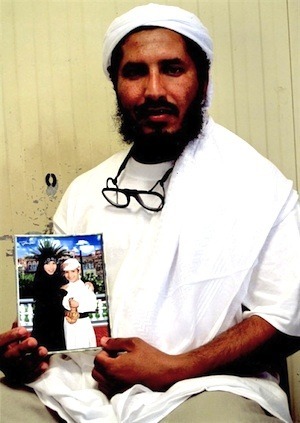

An attorney with CCR visited al-Hajj in Guantánamo last month, and witnessed his deteriorating condition.

However, Pardiss Kebriaei, a senior staff attorney at CCR, issued a statement in which she expressed no expectation that the government would act. She stated:

As it has virtually every time we have sounded an alarm about detainees, the government will deny there’s anything wrong, as if captivity for over 15 years with still no end in sight, on top of the documented torture these men have been through, is healthy, legal, and, moral.

She added:

The human experiment at Guantánamo – where the government tests how far it can go, first with torture and now with hopeless, perpetual detention, before breaking human beings – must end. Since the Trump administration will do nothing to respect human rights and the precarious health of our client, the courts must order it to.

In a further description of al-Hajj’s case, CCR noted that he “was arrested in Pakistan in 2002 [in a house raid in February 2002] and rendered by the United States to secret prisons, where he was interrogated under threats of electrocution and physical violence, subjected to regular beatings, and forced to endure complete darkness and continuous loud music.”

CCR added that his brutal treatment was “detailed in a ruling by the district court in Washington, D.C. striking statements from certain of his interrogations as tainted by torture.” That was in 2011, but prior to that his torture had been acknowledged by a judge considering the habeas corpus petition of another prisoner, Uthman Abdul Rahim Mohammed Uthman, in February 2010. Ruling on the eligibility of statements made by al-Hajj and Sanad al-Kazimi, another prisoner held in “black sites” before being sent to Guantánamo, Judge Henry H. Kennedy Jr. stated, “The Court will not rely on the statements of Hajj or Kazimi because there is unrebutted evidence in the record that, at the time of the interrogations at which they made the statements, both men had recently been tortured.”

In recent years, al-Hajj had his case reviewed by a Periodic Review Board, a parole-type process set up by President Obama. Although 38 out of 64 men had their release recommended by the PRB process, al-Hajj was not one of them. Following a PRB in March 2016, at which he was described by the US authorities as “a career jihadist who acted as a prominent financial and travel facilitator for al-Qa’ida members before and after the 9/11 attacks,” he was approved for ongoing detention on April 14, 2016. A second review took place In February 2017, but his ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial was approved in March. As CCR noted, “His next full review by the PRB will be in 2020.”

The question, now, however – beyond whether it is acceptable to hold someone for 18 years without charge or trial (which it clearly isn’t) – is whether al-Hajj will live that long.

Note: For more information about the case, see the CCR case page, where you can also find CCR’s emergency motion, a declaration by Pardiss Kebriaei and another medical declaration, by Dr. Robert L. Cohen.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

September 7, 2017

11 Years After CIA Torture Victims Arrived at Guantánamo, Whistleblowers Joseph Hickman and John Kiriakou on How Torture “Became Legal” After 9/11

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

Exactly eleven years ago, on September 6, 2006, George W. Bush, who had previously denied holding prisoners in secret prisons run by the CIA, admitted that the secret prisons did exist, but stated in a press conference that the men held in them had just been moved to Guantánamo, where they would face military commission trials.

To date, just one man has been successfully prosecuted — Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani, a minor player in the 1998 bombings of two US embassies in Africa, who was only successfully prosecuted because he was moved to the US mainland and given a federal court trial. In response, Republican lawmakers petulantly passed legislation preventing such a success from happening again, leaving the other men to be caught in seemingly endless pre-trial military commission hearings, or imprisoned indefinitely without charge or trial. Seven men — including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four other men changed in connection with the 9/11 attacks — are in the former category, while another man (Majid Khan) agreed to a plea deal in 2012, but is still awaiting sentencing, and five others — including Abu Zubaydah, a logistician mistakenly regarded as a high-ranking terrorist leader, for whom the torture program was first developed — continue to be held without charge or trial, and largely incommunicado, with no sign of when, if ever, their limbo will come to an end.

Last year, I wrote an article about the “high-value detainees” on the 10th anniversary of their arrival at Guantánamo, entitled, Tortured “High-Value Detainees” Arrived at Guantánamo Exactly Ten Years Ago, But Still There Is No Justice, and this year I’m taking the opportunity to cross-post an excerpt from a recently published book, The Convenient Terrorist, by Joseph Hickman and John Kiriakou, published by Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., and available from Amazon, Barnes & Noble and IndieBound. The excerpt was first published on Salon.

The authors know what they are talking about. Hickman was a guard at Guantánamo, in charge of the towers, from which, on the night of June 9, 2006, he witnessed an unusual movement of vehicles that prompted him to severely doubt the claim, made later that night, that three prisoners had committed suicide. Hickman’s story was first exposed publicly in Harper’s Magazine in January 2010, and in 2015 a book based on his experiences, Murder At Camp Delta, was published. Kiriakou, meanwhile, was a CIA analyst and case officer, and was imprisoned for nearly two years for whistleblowing, having disclosed the identity of a fellow CIA officer to a journalist, even though the journalist did not publish the officer’s name.

Hickman and Kiriakou’s article is timely and fascinating. They explain how “[p]reparations for implementing a torture program … pre-dated Abu Zubaydah’s capture [in March 2002] by many months,” something that I have long argued, but lacked the evidence to prove. They also run through the development of the program — including the key role played by James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, psychologists who had worked for the US military in the SERE program (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape), training US personnel to resist torture if captured by a hostile enemy. For a total of $81m, Mitchell and Jessen reverse-engineered the SERE program for use on alleged terrorists, even though, as Hickman and Kiriakou point out, Senate investigators working for the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report into the CIA torture program, of which the executive summary was published in December 2014, “noted that neither Jessen nor Mitchell had any firsthand experience as interrogators,” and “nor did either have specialized knowledge of Al Qaeda, a background in terrorism, or any relevant regional, cultural, or linguistic expertise.” both men recently avoided a trial by reaching a financial settlement with two of their victims, and the family of a third, who died in US custody in Afghanistan in 2002, and there are hopes that, as a result, further calls for accountability might also be successful.

Hickman and Kiriakou also write of the role played by “torture memo” author John Yoo, and his boss Jay Bybee, and run through the techniques approved by Yoo and Bybee, which, they explain, are “specifically prohibited” by US law. They also write about how the FBI refused to be involved, and Kiriakou adds his own explanation of how, when he learned what was required of him under this new regime, he also refused to be involved, although others were not so principled. As he and Hickman note, “More than a dozen CIA officers accepted the invitation to be trained in the new techniques. This dozen became the core cadre of ‘interrogators,’ a designation the CIA had never had before.”

I hope you have time to read the article below, and will share it if you find it useful.

The road to torture: How the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation techniques” became legal after 9/11

The road to torture: How the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation techniques” became legal after 9/11By Joseph Hickman and John Kiriakou, Salon, September 4, 2017

The CIA’s torture techniques — 10 in total — increased in severity as one went down the list.

The FBI allows agents to take one of two approaches when conducting an interrogation. The Informed Interrogation Approach calls for the interrogator to become as fully informed on issues important to the subject as possible, and then to establish a rapport with the target. Under this approach, the interrogator builds trust over a period of time until the subject begins to supply useful information. In contrast, the Coercive Interrogation Approach — sometimes called the Coercive Interrogation Technique — calls for interrogators to employ force and pain, and to create a feeling of helplessness and isolation which will make the subject more likely to talk to his interrogator.

But the FBI would not be the only ones interrogating Abu Zubaydah.

Investigators for the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence found that the CIA, at the time of the 9/11 attacks, had in place “longstanding formal standards for conducting interrogations.” These standards did not include torture or “enhanced techniques” of any kind. Indeed, according to the 2012 Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture:

In January 1989, the CIA informed the Committee that “inhumane physical or psychological techniques are counterproductive because they do not produce intelligence and will probably result in false answers.” Testimony of the CIA deputy director for operations in 1988 (Richard Stolz) denounced coercive interrogation techniques, stating, “[p]hysical abuse or other degrading treatment was rejected, not only because it is wrong, but because it has historically proven to be ineffective.” By October 2001, CIA policy was to comply with the Department of the Army Field Manual “Intelligence Interrogation.” A CIA Directorate of Operations Handbook from October 2001 states that the CIA does not engage in “human rights violations,” which it defined as: “Torture, cruel, inhuman, degrading treatment or punishment, or prolonged detention without charges or trial.” The handbook further stated that “[i]t is CIA policy to neither participate directly in nor encourage interrogation which involves the use of force, mental or physical torture, extremely demeaning indignities or exposure to inhumane treatment of any kind as an aid to interrogation.”

Yet the rules that had worked so well in the past didn’t seem to fit the world of late 2001, at least according to the CIA leadership. By November 2001, CIA Director George Tenet had ordered his attorneys and senior officers of the Agency’s Counterterrorism Center to draft new protocols for interrogation that would allow for harsher approaches than the Agency had ever allowed before.

In a classified memo entitled “Hostile Interrogations: Legal Considerations for CIA Officers,” dated November 21, 2001, “the Israeli example” is cited as a possible basis for arguing before courts and the American people that “torture was necessary to prevent imminent, significant, physical harm to persons, where there is no other available means to prevent the harm.”

But the CIA was already on record with the Senate Intelligence Committee as saying that torture didn’t work. Committee investigators wrote, “Despite the CIA’s previous statements that coercive physical and psychological interrogation techniques ‘result in false answers’ and have ‘proven to be ineffective.’” Nonetheless, by the end of November 2001, CIA attorneys began circulating a draft memorandum suggesting “novel” legal defenses for CIA officers who might, in the future, engage in torture. According to Senate investigators, “The memorandum stated that the ‘CIA could argue that the torture was necessary to prevent imminent, significant, physical harm to persons, where there is no other available means to prevent the harm,’ adding that ‘states may be very unwilling to call the US to task for torture when it resulted in saving thousands of lives.’”

Still, it wasn’t up to the CIA’s leadership to decide when and if torture should be employed. That remained a policy decision, and it would have to have the support of the Principals’ Committee, chaired by the President, and including the Vice President, the National Security Advisor, the Attorney General, and the Secretaries of State and Defense — in addition to the CIA Director.

In January 2002, according to Senate investigators, the principals began debating whether to apply Geneva Convention protections to captured prisoners from Al Qaeda and the Taliban. Director Tenet sent a letter to President Bush urging “that the CIA be exempt from any application of these protections,” arguing that application of Geneva would significantly hamper the ability of the CIA to obtain critical threat information necessary to save American lives. On February 1, 2002 — approximately two months prior to the detention of the CIA’s first prisoner — a CIA attorney wrote that if CIA detainees were covered by Geneva there would be “few alternatives to simply asking questions.” The attorney concluded that, if that were the case, “then the optic becomes how legally defensible is a particular act that probably violates the convention, but ultimately saves lives.”

Preparations for implementing a torture program thus pre-dated Abu Zubaydah’s capture by many months. Senior CIA officers had already bought into the use of “Ticking Time Bomb” scenarios, in which it was argued that captured terrorists had to be tortured to reveal the locations of operations still underway that might result in the deaths of innocent people. However, as FBI agent and interrogator Ali Soufan would later testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee, these scenarios never actually arise. But that didn’t stop the CIA’s senior-most officials from creating a list of torture techniques, euphemistically called “enhanced interrogation techniques,” to be used on high-profile prisoners.

According to the CIA’s inspector general at the time, “the capture of senior Al Qaeda operative Abu Zubaydah on 27 March 2002 presented the Agency with the opportunity to obtain actionable intelligence on future threats to the United States from the most senior Al Qaeda member in US custody at the time. This accelerated CIA’s development of an interrogation program.”

That development took the form of two CIA contract psychologists, Bruce Jessen and James Mitchell. Jessen and Mitchell had been psychologists with the US Air Force Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) school, where military personnel are exposed to the kinds of intense and hostile interrogation techniques to which they might be subjected if they were to be shot down and fall into enemy hands. The two founded a consulting company in 2005 to offer the CIA, apparently through a friend who worked in the CIA’s Office of Technical Services, a “reverse-engineered” version of SERE training that could be carried out on prisoners to force them to talk. Senate investigators noted that neither Jessen nor Mitchell had any firsthand experience as interrogators, “nor did either have specialized knowledge of Al Qaeda, a background in terrorism, or any relevant regional, cultural, or linguistic expertise. Jessen had reviewed research on ‘learned helplessness,’ in which individuals might become passive and depressed in response to adverse or uncontrollable events. He theorized that inducing such a state could encourage a detainee to cooperate and provide information.” Yet it was Jessen and Mitchell who first suggested a list of ten coercive techniques that would be used on prisoners.

CIA officers then sent this list of techniques to the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) for clearance. OLC attorney John Yoo drafted a series of memos approving each of the proposed techniques as legal. OLC director and assistant attorney general Jay Bybee signed the memos in early August 2002 after clearing them with attorneys on the National Security Council. Vice President Richard Cheney later confirmed that he “and others” had “signed off” on the torture techniques. For the first time in US history, it was now legal to torture prisoners.

The CIA’s torture techniques — ten in total — increased in severity as one went down the list. They were largely modeled on techniques used by Chinese communists against captured American servicemen during the Korean War, according to Senator Carl Levin, former chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. As outlined in the CIA Inspector General’s Report, they included Attention Grasp; Walling; Facial Hold; Facial Slap or Insult Slap; Cramped Confinement; Insect Placement; Wall Standing; Stress Positioning; Sleep Deprivation; and Waterboarding:

The attention grasp consists of grasping the detainee with both hands, with one hand on each side of the collar opening, in a controlled and quick motion. In the same motion as the grasp, the detainee is drawn toward the interrogator.

During the walling technique, the detainee is pulled forward and then quickly and firmly pushed into a flexible false wall so that his shoulder blades hit the wall. His head and neck are supported with a rolled towel to prevent whiplash.

The facial hold is used to hold the detainee’s head immobile. The interrogator places an open palm on either side of the detainee’s face and the interrogator’s fingertips are kept well away from the detainee’s eyes.

With the facial or insult slap, the fingers are slightly spread apart. The interrogator’s hand makes contact with the area between the tip of the detainee’s chin and the bottom of the corresponding earlobe.

In cramped confinement, the detainee is placed in a confined space, typically a small or large box, which is usually dark. Confinement in the smaller space lasts no more than two hours and in the larger space it can last up to eighteen hours.

Insects placed in a confinement box involve placing a harmless insect in the box with the detainee. [Authors’ Note: This was to enhance the mental strain on prisoners like Abu Zubaydah, who had an irrational fear of insects.]

During wall standing, the detainee may stand about four to five feet from a wall with his feet spread approximately to his shoulder width. His arms are stretched out in front of him and his fingers rest on the wall to support all of his body weight. The detainee is not allowed to reposition his hands or feet.

The application of stress positions may include having the detainee sit on the floor with his legs extended straight out in front of him with his arms raised above his head or kneeling on the floor while leaning back at a 45 degree angle.

Sleep deprivation will not exceed eleven days at a time.

The application of the waterboard technique involves binding the detainee to a bench with his feet elevated above his head. The detainee’s head is immobilized and an interrogator places a cloth over the detainee’s mouth and nose while pouring water onto the cloth in a controlled manner. Airflow is restricted for twenty to forty seconds and the technique produces the sensation of drowning and suffocation.

The problem with these techniques is that — the opinions of John Yoo and Jay Bybee notwithstanding — they were specifically prohibited by law. The Federal Torture Act, 18 US Code § 2340, clearly defines torture:

[T]orture means an act committed by a person acting under the color of law specifically intended to inflict severe physical or mental pain or suffering (other than pain or suffering incidental to lawful sanctions) upon another person within his custody or physical control;

“Severe mental pain or suffering” means the prolonged mental harm caused by or resulting from —

the intentional infliction of threatened infliction of severe physical pain or suffering;

the administration or application, or threatened administration or application, of mind-altering substances or other procedures calculated to disrupt profoundly the senses or the personality;

the threat of imminent death; or

the threat that another person will imminently be subjected to death, severe physical pain or suffering, or the administration or application of mind-altering substances or other procedures calculated to disrupt profoundly the senses or personality; and

“United States” means the several States of the United States, the District of Columbia, and the commonwealths, territories, and possessions of the United States.

The remainder of the Act could not be any clearer:

Offense. —

Whoever outside the United States commits or attempts to commit torture shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both, and if death results to any person from conduct prohibited by this subsection, shall be punished by death or imprisoned for any term of years or for life.

Jurisdiction. — There is jurisdiction over the activity prohibited in subsection (a) if —

the alleged offender is a national of the United States; or

the alleged offender is present in the United States, irrespective of the nationality of the victim or alleged offender.

Conspiracy. —

A person who conspires to commit an offense under this section shall be subject to the same penalties (other than the penalty of death) as the penalties prescribed for the offense, the commission of which was the object of the conspiracy.

The ten approved methods seem to meet the criteria for torture even when applied exactly as described. Yet the CIA officers involved did not always adhere strictly to the techniques. At least two prisoners were killed by CIA officers (or persons acting on behalf of the CIA) during interrogations. These instances — and many more near misses — often involved variations on the ten approved methods.

It wasn’t just US law that prohibited what the CIA was doing. The United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment — of which the United States was the primary author and an original signatory — specifically bans anything approaching “enhanced interrogation” techniques. As Article 1 of the convention states:

torture means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent of acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.

There was precedent for punishing Americans involved in torture, and specifically for involvement in waterboarding. On January 21, 1968, the Washington Post ran a front-page photograph of an American soldier waterboarding a North Vietnamese prisoner. On the day that the photo was published, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara ordered an investigation, and the soldier eventually was court martialed and convicted of torturing a prisoner.

The government had found waterboarding to be an inappropriate form of torture as recently as 1968. No law had been changed since. The Bush Administration merely pretended — thirty-four years later — that this and other precedents did not exist.

President George W. Bush approved the torture of Abu Zubaydah in writing on August 1, 2002. However, it turned out that there was already a backstory, and the torture had already begun, apparently in anticipation of the President’s approval.

The CIA had flown Abu Zubaydah from Pakistan to his “onward location,” a secret prison in a foreign country, codenamed Detention Site Green, in late March 2002. He was too severely wounded to be questioned initially, however, and the Johns Hopkins physician had set up shop on the scene to care for his charge. The CIA medical team decided after his arrival that they could not handle the severity of his injuries, and Abu Zubaydah was again moved to a hospital for treatment. FBI Agent Ali Soufan recalled before the Senate Judiciary Committee: “At the hospital, we continued our questioning as much as possible, while taking into account his medical condition and the need to know all information he might have on existing threats.”

Some weeks later, Abu Zubaydah had recovered enough to be interrogated. As Soufan told the Senate Judiciary Committee:

Immediately after Abu Zubaydah was captured, a fellow FBI agent and I were flown to meet him at an undisclosed location. We were both very familiar with Abu Zubaydah and have successfully interrogated Al Qaeda terrorists. We started interrogating him, supported by CIA officials who were stationed at the location, and within the first hour of the interrogation, using the Informed Interrogation Approach, we gained important actionable intelligence. The information was so important that, as I learned later from open sources, it went to CIA Director George Tenet, who was so impressed that he initially ordered us to be congratulated.

Traditional FBI techniques were working. Those techniques instructed agents to “know your subject, establish a rapport with him, and engage him in conversation.” This was happening, and it was yielding results. Soufan told the Senate Judiciary Committee that when Abu Zubaydah returned to the secret site from the hospital: “We were once again very successful and elicited information regarding the role of Khalid Shaikh Muhammad as the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, and lots of other information that remains classified. It is important to remember that before this, we had no idea of KSM’s role in 9/11 or his importance in the Al Qaeda leadership structure. All this happened before the CTC team (the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center) arrived.”

This was pivotal information. The CIA had had no idea that Khalid Shaikh Muhammad had been the mastermind of the September 11 attacks. They knew only that an individual named “Mukhtar” had been in charge at the time. Muhammad was on the FBI’s most wanted list because he had been indicted in 1996 for his role in a plot to detonate explosives on twelve US airliners flying over the Pacific. On April 10, 2002, during an interrogation conducted by Soufan, Abu Zubaydah identified a photograph of Muhammad as “Mukhtar” and said, correctly, that he was a relative of Ramzi Ahmed Yousef, who was in a US prison after having detonated a bomb at the World Trade Center in 1993.

According to Senate investigators in the Senate torture report released in December 2014, “Abu Zubaydah told the FBI officers that Mukhtar trained the 9/11 hijackers and also provided additional information on KSM’s background, to include that KSM spoke fluent English, was approximately 34 years old, and was responsible for Al Qaeda operations outside Afghanistan.” It was the FBI and Soufan that collected this critical information. There was no CIA involvement. But interestingly, Senate investigators noted, “Subsequent representations on the success of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program consistently describe Abu Zubaydah’s identification of KSM’s role in the September 11, 2001 attacks, as well as his identification of KSM’s alias (Mukhtar), as being ‘important’ and ‘vital’ information.” The CIA was taking credit for the FBI’s success.

Actionable intelligence notwithstanding, the CTC team’s arrival presaged a sea change in the treatment of Abu Zubaydah.

Unbeknownst to Soufan and his FBI colleagues, a decision had been made in Washington that would change everything. The President had signed the order allowing Abu Zubaydah’s torture to begin, and the CTC team already on its way to the site included untrained interrogators and also Jessen and Mitchell, who had created the torture program by reverse-engineering the SERE training.

As Soufan told the Senate Judiciary Committee:

A few days after we started interrogating Abu Zubaydah, the CTC interrogation team finally arrived from DC with a contractor who was instructing them on how they should conduct the interrogations, and we (the FBI) were removed. Immediately, on the instructions of the contractor, harsh techniques were introduced, starting with nudity.

The new techniques did not produce results as Abu Zubaydah shut down and stopped talking. At that time, nudity and low-level sleep deprivation (between 24 and 48 hours) was being used. After a few days of getting no information, and after repeated inquiries from DC asking why all of a sudden no information was being transmitted, when before there had been a steady stream, we were again given control of the interrogation.

Soufan soon returned to his Informed Interrogation Approach. Abu Zubaydah, again clothed and with a good night’s sleep, started talking. He gave the FBI details on Jose Padilla, the so-called “dirty bomber” whom Abu Zubaydah said was planning to detonate a radiological bomb. Thanks to this information, Padilla was arrested in Chicago, charged with criminal conspiracy, convicted, and eventually sentenced to twenty-one years in a federal prison.

But that wasn’t good enough for the CIA, and the contractor again began using torture techniques, this time employing constant loud noise and temperature manipulation, in addition to nudity and sleep deprivation. Soufan and a fellow FBI agent objected to this, but were overruled. A CIA psychologist who had objected earlier left the site in protest.108 The harsher techniques failed — again — and Soufan was once more asked to reengage with Abu Zubaydah. He had been traumatized by the torture techniques, but, eventually, Abu Zubaydah began speaking with Soufan.

While this was happening, Soufan sent formal objections to both FBI Headquarters and CIA Headquarters. In a cable to his leadership, he said that the CIA psychologist:

believe[s] AZ is offering “throw away information” and holding back from providing threat information. (It should be note [sic] that we have obtained critical information regarding AZ thus far and have now got him speaking about threat information, albeit from his hospital bed and not [an] appropriate interview environment for full follow-up (due to his health). Suddenly the psychiatric team here wants AZ to only interact with their [CIA officer] as being the best way to get the threat information … We offered several compromise solutions … all suggestions were immediately declined without further discussion … This again is quite odd as all information obtained from AZ has come from FBI lead interviewers and questioning … I have spent an un-calculable [sic] amount of hours at [Abu Zubaydah’s] bedside assisting with medical help, holding his hand and comforting him through various medical procedures, even assisting him in going [to] the bathroom … We have built tremendous [rapport] with AZ and now that we are on the eve of “regular” interviews to get threat information, we have been “written out of future interviews.”

The CIA tactics had shifted once more. Rather than sitting across a table from Soufan, Abu Zubaydah was now interrogated by CIA officers wearing all black uniforms — which included boots, gloves, balaclavas, and goggles — to keep Abu Zubaydah from identifying the officers, as well as to prevent him from “seeing the guards as individuals who he may attempt to establish a relationship or dialogue with.” Meanwhile, Abu Zubaydah was kept naked, deprived of sleep, and after being returned to Detention Site Green from the hospital, kept in a small white room with no windows and four halogen lights.

The CIA-FBI pissing match was coming to a head. The contractor again insisted on taking over, and he asked CIA Headquarters for permission to put Abu Zubaydah into what was called a “confinement box.” Accordingly, Soufan again protested to his superiors at the FBI. He refused to further assist in interrogating Abu Zubaydah. FBI Director Robert Mueller agreed with Soufan’s assessment — that the CIA’s techniques constituted torture — and ordered that all FBI personnel return to the US.

By the summer of 2002, the CIA was fully in control of Abu Zubaydah’s fate. In June 2002, the CIA team decided to put Abu Zubaydah into isolation (solitary confinement) where he remained for forty-seven days. This isolation ended on August 4, 2002, after the President signed the memorandum allowing torture.

The problem for the CIA was that Abu Zubaydah was not providing actionable intelligence on Al Qaeda’s next attack. This was because he simply didn’t know any further information. But the “good cops” were out, while Jessen, Mitchell, and the “bad cops” were in. The CIA saw Abu Zubaydah’s inability to provide the information as “unwillingness,” and deemed him “uncooperative.”

It was this determination that Abu Zubaydah was only being uncooperative that convinced CIA Headquarters to employ increasingly severe forms of interrogation upon their subject. As US Senate investigators subsequently found, in July of 2002 the CIA’s leadership held several meetings specifically to discuss the use of “novel interrogation methods” on Abu Zubaydah. These were the “enhanced interrogation techniques” that had previously been cleared by the Justice Department.

It was during this period, at the end of July 2002, that a senior officer at the Counterterrorism Center approached John Kiriakou and asked if he wanted to be “certified in the use of enhanced interrogation techniques.”

“What’s that mean?” Kiriakou asked in the moment.

“It means we’re going to start getting rough with these guys!” was the immediate response.

The CTC officer quickly explained the new techniques that were in the offing.

“That sounds an awful lot like torture,” Kiriakou said.

But then he added that he would take a couple of hours to think about it.

Kiriakou made an appointment to see a very senior CIA officer with whom he’d had a friendly relationship for a decade. That same afternoon he went to the seventh floor, the CIA’s executive level, for the meeting. A moment after sitting down, he told the senior officer about the approach from CTC.

“What do you think?” he asked.

The response was not what he’d been expecting.

“First let’s call it what it is,” the senior officer said. “It’s torture. They can use any euphemism they want, but it’s still torture. And torture is a slippery slope. Eventually, somebody is going to go overboard and they’re going to kill a prisoner. When that happens, there’s going to be a Congressional investigation. Then there’s going to be a Justice Department investigation. And in the end, somebody’s going to go to prison. Do you want to go to prison?”

Kiriakou didn’t.

Kiriakou walked back down to CTC, found the officer, and said bluntly: “This is a torture program. I don’t want to be associated with it.”

But others did.

More than a dozen CIA officers accepted the invitation to be trained in the new techniques. This dozen became the core cadre of “interrogators,” a designation the CIA had never had before.

Yet prior to the actual torture beginning, the CIA found it had more paperwork to take care of. Following the July meetings, the CTC General Counsel and other CIA legal officials sent a letter to Attorney General John Ashcroft asking for a formal declination letter. This would be a letter from the Justice Department specifically declining to prosecute any CIA officer, or any person working on behalf of the CIA, “who may employ methods in the interrogation of Abu Zubaydah that otherwise might subject those individuals to prosecution.” The letter would also specify that “the interrogation team had concluded that the use of more aggressive methods is required to persuade Abu Zubaydah to provide the critical information we need to safeguard the lives of innumerable innocent men, women, and children within the United States and abroad.” It concluded, tellingly, that these “aggressive methods” would otherwise be prohibited by the torture statute.

The CIA knew that what they were planning to do was torture. They admitted as much in this letter. That was why they were asking for a “Get out of Jail Free” card for their torturers.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

September 5, 2017

My Band The Four Fathers Release New Single, ‘She’s Back’, About Pussy Riot, As Maria Alyokhina Releases Memoir, ‘Riot Days’

Today, my band The Four Fathers are releasing ‘She’s Back’, our new online single from our forthcoming album, ‘How Much Is A Life Worth?’, which we’ll be releasing on CD soon, hopefully within the next month.

Today, my band The Four Fathers are releasing ‘She’s Back’, our new online single from our forthcoming album, ‘How Much Is A Life Worth?’, which we’ll be releasing on CD soon, hopefully within the next month.

‘She’s Back’ was written by guitarist Richard Clare, first aired in 2015, and recorded in a session last year for the new album. It’s about Pussy Riot, politicized performance artists from Russia, who use punk music to get across their messages, which have involved feminism, LGBT rights and the corruption of Vladimir Putin. We recorded it in July 2016, with Richard on lead vocals and 12-string guitar, me on rhythm guitar and backing vocals, Brendan Horstead on drums, Andrew Fifield on flute and Louis Sills-Clare on bass.

The song is below, on Bandcamp, where you can listen to it, and, if you wish, download it for just £1 ($1.30). We hope you like it!

She’s Back by The Four Fathers

Formed in 2011, Pussy Riot gained international notoriety in 2012 after five members of the group staged a punk rock performance — a ‘Punk Prayer’ — inside Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, which was aimed at the church’s support for Putin during his election campaign.

Three of the five were subsequently arrested, in March 2012 — Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, Maria Alyokhina and Yekaterina Samutsevich — and were put on trial in July. In August, they were convicted of “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred”, and sentenced to two years’ imprisonment. Samutsevich’s sentence was suspended on appeal in October, but Tolokonnikova and Alyokhina had their sentences upheld, and were imprisoned for 21 months, only finally being released on December 23, 2013.

Tolokonnikova and Alyokhina subsequently appeared as Pussy Riot members during the Winter Olympics in Sochi, where, as Tolokonnikova reported, Cossacks employed as security guards “attacked us, beat us with whips and abundantly sprayed us with pepper gas”. In March 2014, Tolokonnikova and Alyokhina were “seriously assaulted at a fast food outlet by local youths in Nizhny Novgorod.” Last month, Alyokhina was briefly detained, in Yakutsk in eastern Siberia, with another Pussy Riot member, Olga Borisova, after a protest against the imprisonment of film-maker Oleg Sentsov. As the Guardian described it, “the pair unfurled a ‘Free Sentsov’ banner on a road bridge, along with plumes of coloured smoke.”

Richard states that the song was “inspired by an interview with Nadezhda Tolokonnikova about her time in a gulag and her aims and feelings after release.” Her first major interview after her release seems to have been with Der Spiegel, the week after her release, in which, under the heading, ‘I Want Justice’, she spoke of her imprisonment as follows:

I spent most of the time at a penal colony in Mordovia. This is what my day was like there: Wake up at 5:45 a.m., 12 minutes of early-morning exercise, followed by breakfast and forced labor as a seamstress. Being allowed to go to the bathroom or smoke a cigarette depended on the guards’ mood. Lunch was greasy and of poor quality. The workday ended at 7 p.m., when there was roll call in the prison yard. After that, we were sometimes required to shovel snow or do other cleanup work. Then we waited in line to wash up a little, and finally we went to bed.

Asked if she was treated decently, she said:

No. It was terrible. They tried everything to break me and silence me. The collective punishments were the worst, almost unbearable. Because of a small gesture, or when I asked the camp management to observe the law, 100 people were assigned to a punishment unit, where beatings were customary. I was treated better than others, simply because there was so much public attention. In my case, they did adhere to the eight-hour workday required by law. The other women were often forced to slave away for up to 16 hours a day.

In September 2014, Tolokonnikova spoke to Amelia Gentleman of the Guardian, when she had “set up a prison-reform project and launched a news agency website, Mediazona.” The prison reform project, set up with Alyokhina, is Zona Prava (Justice Zone), described as “a campaigning charity aimed at improving conditions in Russia’s jails.”

In October 2016, as the Guardian described it, Pussy Riot “released a song celebrating the vagina, in an unashamed feminist riposte to Donald Trump and his boast that when he meets beautiful women he ‘grabs them by the pussy.’” The song, ‘Straight Outta Vagina’, was written by Tolokonnikova, and recorded in the US, and that same month they also released another anti-Trump song, ‘Make America Great Again.’

Bringing the story up to date, Maria Alyokhina has a memoir out next week, ‘Riot Days’, reviewed by the Guardian last week, and described as “a punk version of history and a work of art in itself, a statement against corruption and patriarchy.” In an interview at the weekend, asked about Donald Trump, she said, “Political art is simply essential for life in the United States right now. It’s not just about Trump. It’s about Nazi groups that are calling for people to be judged according to racial characteristics and so on. If you call someone dangerous then it means you are scared of them. You shouldn’t be scared, you need to act.” She added, as the Guardian described it, that “[p]eople everywhere should be wary of putting too much faith in politicians,” who, as Alyokhina said, need to be “poked in the backside.” She also said, “Politics is not something that exists in one or another White House. It is our lives. The political process is happening all the time.”

She also made a few other good comments about activism, both of which reflect my own experiences: firstly, “Every day a person makes choices. It doesn’t happen that you suddenly understand something and become a different person just like that. It’s daily toil,” and, secondly, “I am not the sort of person who sits around waiting for some sort of end. You have to keep acting whatever the conditions. I fight against indifference and apathy … and for freedom and choice.”

Please also feel free to follow The Four Fathers on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, and email us if you want to be on our mailing list, or if you can offer us any gigs!

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

September 1, 2017

Radio: I Discuss My Contention That We Should Take a Break from Constant Phone and Internet Use with Chris Cook on Gorilla Radio

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist and commentator.

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist and commentator.

Regular readers will know that I just got back from a fortnight’s holiday in Sicily with my family, and that, after the second week, in which I was offline for the whole time, I returned to the UK and published my immediate thoughts about the benefits of sometimes switching off from the whole internet and mobile phone world in an article entitled, Switch Off Your Devices and Have a Week Off: Why Headspace, Silence and Human Interaction is Good for Us.

After publishing it, I was very pleasantly surprised when Chris Cook of Gorilla Radio, based in Canada, got in touch to ask me if I’d be interested in appearing on his weekly show to discuss it, and I happily agreed. Chris and I have spoken many times before, but always about Guantánamo, so I was delighted to be able to talk about another topic that interests me.

The one-hour show is available here (and here as an MP3) and my interview with Chris begins around 35 minutes in, after an interview William Laurance, an Australian research professor, who has been studying the impact of cars on wildlife, and is the author of an article entitled, Curbing an Onslaught of 2 Billion Cars.

In my analysis of the benefits of balancing our online presence with time off, I acknowledged that I work as an online journalist and commentator, and have no desire to put myself out of a job (or what passes for a job), but I was pleased to be able to express some of my doubts about possible downsides to our relationship with the internet and particularly with smart phones — hand-held devices that would once have required an entire room to power them, but which are now ubiquitous, even though their advent is so recent that definitive assessments of their long-term impact don’t currently exist.

As well as worrying about the atomizing effects of mobile technology and the internet, I also have concerns about how all this technology also accompanies an increasingly mechanized world, the dangers posed by artificial intelligence (introduced in a guest post recently by my friend Tom Pettinger), and how fundamentally alarming it is that so many creative people are now required to make their work available for free, a shifting business model in which, often, the only people who are making a profit run, work for, or are shareholders of the giant tech companies who are eating up more and more of the world in a generally unchecked manner. People should be more questioning, I think, of the giant corporations at the heart of this supposed Brave New World — like Apple, Google and Amazon, but also other Silicon Valley success stories like Uber and Airbnb. For more on this, check out We need to nationalise Google, Facebook and Amazon. Here’s why by academic Nick Srnicek in the Guardian two days ago, Secrets of Silicon Valley on the BBC, and, from July, The billion-dollar palaces of Apple, Facebook and Google in the Observer.

In my article, I was particularly interested in seeing if people have any enthusiasm for the notion of us switching off all our devices every now and then — a week here and there, perhaps one day a week when we all agree to switch off and return to the kind of social interactions that used to exist — and I remain fascinated by that idea, although I’ve had little feedback about it.

Do feel free to let me know what you think about any of the above.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

August 30, 2017

Donald Trump Is Still Trying to Work Out How to Expand the Use of Guantánamo Rather Than Closing It for Good

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

In a dispiriting sign of counter-productive obstinacy on the part of the Trump administration, the New York Times recently reported that, according to Trump administration officials who are “familiar with internal deliberations,” the administration is “making a fresh attempt at drafting an executive order on handling terrorism detainees.” As Charlie Savage and Adam Goldman described it, these efforts “reviv[e] a struggle to navigate legal and geopolitical obstacles” to expand the use of the prison at Guantánamo Bay, which opened over 15 and a half years ago.

Drafts of proposed executive orders relating to Guantánamo had been leaked in Trump’s first week in office, although, as the Times noted, “Congress and military and intelligence officials pushed back against ideas in early drafts, like reopening the CIA’s overseas ‘black site’ prisons where the Bush administration tortured terrorism suspects.” As a result, the White House “dropped that and several other ideas, but as the drafts were watered down, momentum to finish the job faltered.”

Alarmingly, however, Savage and Goldman noted that the Trump administration officials they spoke to told them that Trump “had been expected to sign a detention policy order three weeks ago,” and that the plan only “changed after he fired his first chief of staff, Reince Priebus, on July 28 and replaced him with John F. Kelly,” a retired Marine Corps general who was the commander of US Southern Command, which oversees prison operations at Guantánamo, from November 2012 to January 2016.

Kelly had clashed with Obama administration officials about Guantánamo, and as the Washington Post noted in July, the relationship between him and the Obama White House “had become so strained that, in the weeks before he retired, multiple administration officials went to the media and accused Kelly and other military leaders of endeavoring to undermine [Obama’s] Guantánamo closure plan.”

Despite this, the officials said that “on July 31 — Mr. Kelly’s first day — the National Security Council announced that the White House wanted a new round of interagency deliberations” before issuing a new executive order. The Times reported that the message “came during a secure video teleconference with counterterrorism strategy and legal officials at military, diplomatic and intelligence agencies,” with the agencies “asked to consider three potential versions of the order and make recommendations” by the middle of August.

The Times explained that the first of the three versions “was the version that Mr. Trump was preparing to sign three weeks ago,” which “would reverse a January 2009 order by President Barack Obama that directed the government to close the prison, and make clear that the Trump administration’s policy was instead to keep it open indefinitely.” According to an official who spoke to the Times, this first version “would also say that Guantánamo could be used to hold accused members of Al Qaeda or the Islamic State,” even though transferring Islamic State suspects to Guantánamo “would defy warnings by national security and legal officials about creating legal risks for the broader military campaign underway in Iraq and Syria.”

The second version, according to the official who spoke to the Times, “would add language that says the secretary of defense, Jim Mattis, may bring newly captured terrorism suspects to the prison … explicitly grant[ing] an authority that is merely implicit or ambiguous in the first version,” while the third version “would direct Mr. Mattis to establish criteria about which new detainees should be brought to the prison,” and “would also make clear that new arrivals would be given periodic reviews by a six-agency parole-like board that recommends whether to keep holding or to transfer detainees” — and which have been in operation for the existing Guantánamo prisoners since 2013.

Another official described as being “familiar with internal deliberations” said that Trump was “unlikely to sign any detention order for several weeks because the changes may be wrapped into a broader counterterrorism policy review that is underway.” It was also noted that a spokesman for the National Security Council “declined to comment.”

The proposals are no less troubling now than they were when first floated in January, and it is to be hoped that an executive order reviving Guantánamo doesn’t materialize. As the Times noted, to date the administration “has brought no new detainees to Guantánamo, despite Mr. Trump’s campaign vow to fill the prison back up,” and this is clearly a situation that is encouraging for legal experts, who have expressed profound and repeated doubts about the legality of bringing any new prisoners to Guantánamo, as well as pointing out that federal courts remain the only reliable venue for prosecutions, and for any country with which the US wishes to have a constructive relationship.

As the Times explained, “European and Middle Eastern allies will not transfer detainees to the United States without a promise they will not be sent to Guantánamo,” noting that, last month, “Spain transferred custody of a terrorism suspect, Ali Charaf Damache, whom the Trump administration brought to federal court in Philadelphia for a civilian trial,” while, in the case of an al-Qaeda suspect known as Abu Khaybar, “held in Yemen by an unidentified Middle Eastern ally,” the administration’s efforts to secure his transfer have floundered because, according to current and former law enforcement officials, those holding him, “while willing to transfer [him], will not do so if his destination would be Guantánamo.”

A Washington Post editorial condemning Trump’s plans

In an editorial on Sunday, the Washington Post weighed in with unambiguous criticism of Trump’s plans. In Bringing new detainees to Guantánamo would be a grave mistake, the Post’s editors reminded readers — and the administration — that, after the executive order was leaked in January, “Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis and CIA Director Mike Pompeo disavowed the draft after it was leaked to the press, and the order — which also called for a policy review on the possible reopening of secret CIA prisons around the globe — was never signed.”

Noting that “the administration is trying again,” with an interagency group “drafting a policy that would reverse President Barack Obama’s decree calling for the closure of the prison and authorize Mr. Mattis to bring suspected terrorists to Guantánamo,” the Post’s editors stated, bluntly and accurately, “This would be a grave mistake.”

The editors proceeded to welcome the fact that “none of the policies currently under consideration float a return to the use of CIA prisons — a practice which did great damage to the United States’ international reputation after 9/11” — but pointed out that, “even absent this provision, an executive order authorizing newly captured prisoners to be detained at Guantánamo would risk alienating US allies.” Here at “Close Guantánamo,” we also believe it would have been reassuring to see the editors add that what has been happening at Guantánamo since 2002 is also an affront to values the US claims to hold dear.

In further explanation of their position, the Post’s editors stated, “Domestically, detaining ISIS fighters at the prison would be an invitation to years of risky litigation over the scope of government authority in the battle against the Islamic State,” adding that “short-sighted congressional restrictions on transferring detainees out of Guantánamo, along with a system for trying detainees by military commission that has proved painfully slow and mired in legal confusion, could consign any new detainees to custody without trial for decades.” As the editors added, “The military judge in the case against the 9/11 attackers has yet to even set a trial date.”

The Post’s editors also noted, accurately, that, in contrast to the mess at Guantánamo, the government “has had relative success in prosecuting terrorism suspects in federal court,” proceeding to explain that, in July, “the Trump administration itself extradited a suspected al Qaeda recruiter from Spain to face criminal charges — Ali Charaf Damache, a dual Algerian and Irish citizen, who was brought to a federal court in Philadelphia.

The Post’s editors also noted another, more troubling case as an “indication of the viability of criminal prosecutions,” referring to the case of Ahmed Abu Khattala, “the accused ringleader of the 2012 attacks on an American compound in Libya,” who was interrogated aboard a ship sailing to the United States for three days following his capture in 2014. Just two weeks ago, a federal judge ruled in the government’s favor in the case. The arrangement, as the Post’s editors described it, “allowed government interrogators [from the High-Value Detainee Interrogation Group, set up under President Obama, and consisting of military, intelligence and law enforcement officials] to question Mr. Khattala to gain intelligence before advising him of his right to remain silent, then inform him of his rights and restart the questioning with a new team of officials [from the FBI] in order to build a criminal case against him.” As the editors proceeded to explain, “In holding that prosecutors could use Mr. Khattala’s statements after being read his rights, the court showed that criminal trials need not preclude the intelligence gathering that can be valuable for preventing attacks.”

The editors added, “To be sure, this system is far from perfect,” acknowledging that the judge in Mr. Khattala’s case “hinted that the government may face restrictions on its ability to conduct lengthy interrogations at sea,” but not mentioning how the system of interrogation without rights, followed by a second interrogation by a so-called “clean team” of FBI agents, echoed what took place at the “black sites” and Guantánamo with the so-called “high-value detainees,” to the dismay of many lawyers and legal experts (and ourselves).

Despite our caveats about aspects of the US’s detention policy under Obama, as well as under Trump, we agree wholeheartedly with the Post’s editors’ observation that these cases “demonstrate that the United States can fight terrorism without compounding the tragic mistakes of Guantánamo Bay,” and that “Mr. Trump would be wise to pay attention.”

We hope Donald Trump and his officials are listening.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

August 27, 2017

Switch Off Your Devices and Have a Week Off: Why Headspace, Silence and Human Interaction is Good for Us

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist and commentator.

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist and commentator.

I’m just back from a fortnight’s holiday with my family in Sicily, and am also just back online after a week with no internet access at all, which was a wonderfully refreshing experience.

Don’t get me wrong. I make a living — or what passes for a living — mostly online, and I know more than many how the internet can enable individuals to become truly independent media sources and activists, and how we can reach out across the world in a way that was never possible before the advent of the world wide web. It’s what I’ve been doing for the last eleven years, and will continue to do so long as there are appreciate people out there who are prepared to support me in what I do.

However, the permanently connected world is not without its pitfalls — and I’m not just thinking about fake news, bigotry, and the horrendous rise of cyber-bullies and cyber-misogynists. Every year, when I switch off, I return to a time when there was space in our lives — space to think, to reflect, even to be bored, which can be a constructive experience. It’s somewhere I try to get to regularly in my everyday life, cycling around London taking photos, with no mobile phone connecting me to the online world (or able to track my every move), but I always return to my laptop, to the blizzard of emails, notifications, status updates and more from the absurdly large number of people who purport to be my “friends,” but who, in reality, are a relatively small number of friends and acquaintances vastly outnumbered by people I don’t know at all.

In the online world, seeking attention, we are encouraged to ignore how often our words and our thoughts disappear into the ether, and yet how much we are encouraged to keep on chasing interest and approval via likes and follows, like hamsters in a wheel that only gets smaller and faster-moving the more we go round in it. I’m still avoiding being tied to a mobile phone, in part because of an absurd, old-school desire to be “free”, but also because I genuinely find their use to be alarming — like an extension of people’s bodies, statuses and likes checked relentlessly like nervous tics, attention spans shrunk to almost nothing, intellectual capacity reduced to 140 characters or less.