Andy Worthington's Blog, page 50

August 6, 2017

Video: Andy Worthington’s Band The Four Fathers Play Anti-Austerity Song ‘Riot’, Released on Sixth Anniversary of UK Riots

, and watch the live video here.

, and watch the live video here.Exactly six years ago, on August 6, 2011, riots erupted across the UK. The trigger had been the killing, by police, of Mark Duggan in Tottenham in north London the day before, and for the next three days there were riots across the country — the largest riots in modern British history, as 14,000 people took to the streets.

As I wrote back in May, when my band The Four Fathers released our song, ‘Riot’, which was partly inspired by the 2011 riots, “Buildings and vehicles were set on fire, there was widespread looting, and, afterwards, the police systematically hunted down everyone they could find that was involved — particularly through an analysis of CCTV records — and the courts duly delivered punitive sentences as a heavy-handed deterrent.”

I wrote about the riots at the time, in an article entitled, The UK “Riots” and Why the Vile and Disproportionate Response to It Made Me Ashamed to be British, and my song ‘Riot’ followed up on my inability to accept that the British establishment’s response to the riots had been either proportionate or appropriate.

As I put it in the first verse of ‘Riot’:

The establishment want us to believe everything is fine

But they’re brutal and intolerant if they think we step out of line

In 2011 when there was unrest in the streets

They hunted down those who stole a bottle of water while the bankers all walked free

They stole billions, they crashed the system and lost money for millions

But they never paid nothing and it’s the stench of this hypocrisy

That means that there must be a

Riot Riot Riot

Till you treat us all with decency

Above is a video (via YouTube) of us playing ‘Riot’ in the lovely little rock and roll basement of Vinyl Deptford, a record shop near our band’s home in south east London, at a gig in April. Thanks to Ellen for recording the video, as part of a set of three videos, all of which I subsequently edited. We have previously released ‘Rebel Soldier’ (on YouTube here and on Facebook here) and our cover of Bob Dylan’s ‘Masters of War’ (on YouTube here and on Facebook here). I hope you enjoy this latest video. The recording only contains the second and third verses, unfortunately, but the full version of the song is, of course, included in the studio recording.

The anniversary of the riots seems barely to have been marked in the mainstream media, although Mark Duggan’s family held their annual vigil at Tottenham Police Station on Saturday. Poet and writer Chimene Suleyman wrote an article for the Guardian, ‘A moment that changed me: walking home through the London riots in 2011’, and journalist Sophia Akram compared Mark Duggan’s death with that of Rashan Charles, killed this year, in an article for the Huffington Post, but there the media’s references to the riots end, even though, as Sophia Akram concluded her article:

A film about the 2011 riots from the viewpoint of those at the heart of them quoted Martin Luther King at its beginning – “A riot is the language of the unheard”.

Are people being heard? Well we have rising inequality and between 10% and 30% of deaths after police contact are black men. Charles along with Edir Da Costa and Darren Cumberbatch are the most recent cases from the shocking statistics. And a perception that there still hasn’t been any justice.

Saturday 4 August will be six years since Duggan’s death and the month when the 2011 riots began. And the situation is all depressingly familiar.

As I described the situation in 2011 when ‘Riot’ was released in May:

[N]o effort was made to address the reasons why people were so ready to revolt, and comments like those made by David Cameron, who called the rioters “broken” and “sick,” and Ken Clarke, then the Justice Secretary, who called them “feral,” were unhelpful. In fact, as Reading the Riots, a collaboration between the Guardian and the LSE established, the key reasons for the unrest were “[w]idespread anger and frustration at people’s every day treatment at the hands of police,” including the “use of stop and search, which was felt to be unfairly targeted and often undertaken in an aggressive and discourteous manner”, and “perceived social and economic injustices,” including “the increase in tuition fees, … the closure of youth services and the scrapping of the education maintenance allowance.”

University tuition fees had been trebled at the end of 2010, in a move that had seen the first widespread acts of civil disobedience under the coalition government, and youth services across the country had largely been cut almost as soon as the government took office in May 2010. In addition, the government had scrapped the EMA, which had provided financial support to pupils from poor backgrounds. All were understandable grievances as a response to the clear attack on poorer members of society through the government’s austerity programme.

I wrote about these protests at the time in a series of articles — see, for example, 50,000 Students Revolt: A Sign of Much Greater Anger to Come in Neo-Con Britain, Did You Miss This? 100 Percent Funding Cuts to Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Courses at UK Universities and Cameron’s Britain: “Kettling” Children for Protesting Against Savage Cuts to University Funding.

The report into the 2011 riots also found that gang involvement had been overstated by the authorities, as had the use of social media, and that rioters’ “involvement in looting was simply down to opportunism.”

The response of the courts was so heavy-handed that, I believe, it has left a permanent recognition amongst the less privileged members of society that there are two rules in play — one for the rioters, who, in one case, received a six-month prison sentence for stealing £3.50-worth of mineral water from an already looted store, and another for the bankers, the self-styled “Masters of the Universe,” who were not punished at all for their crimes that led to the global crash of 2008.

And as we look at the situation six years on from the 2011 riots, it is also worth reflecting the fact that, in the last year, another shocking example of contempt by the authorities emerged in June, when Grenfell Tower in west London was consumed in an inferno that was entirely preventable, and that only occurred because protections for the poor had gradually been whittled away over the years, to enable the rich to make greater profits.

And in Tottenham? Well, far from understanding the difficulties imposed on communities that face deprivation and poverty, Haringey Council — a Labour council — recently announced its intention to enter into a disgraceful deal with property developer Lendlease, who will provide funds for the council in exchange for leading the “regeneration” of Haringey’s social housing stock; in reality, the demolition of estates including Broadwater Farm, where Mark Duggan lived, and the social cleansing of the estates’ inhabitants.

I wrote about this housing scandal recently, in an article entitled, Haringey and the Wholesale Social Cleansing of London: Thousands of Social Tenants to Be Removed Via Estate Regeneration, and I wonder if those affected by this colossal programme of social cleansing — not just in Haringey, but across London’s 32 boroughs — will accept their homelessness, or their exile or banishment willingly, or if they will fight back?

Six years on from the 2011 riots, it would, I think, be impossible for anyone truly objective to say that conditions have changed favourably for the capital’s poorer inhabitants, as their very existence in the city that many of them have always called home comes under a sustained, unprecedented, and, to my mind, absolutely unforgivable threat.

Below is the studio recording of ‘Riot.’ Please have a listen, and feel free to buy it as a download if you’d like to support our work.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp. He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp. He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

August 4, 2017

Sufyian Barhoumi, the Peaceful Algerian Cleared for Release But Still Trapped in Guantánamo

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

In the long and sordid history of Guantánamo — open for 15 years and seven months, and still holding men indefinitely without charge or trial, in defiance of domestic and international norms regarding imprisonment — it’s sometimes easy for people to forget the role played by lawyers in resisting the injustice of the prison, and in publicizing the men’s stories.

For over 12 years now, lawyers have generally been the only people outside of the various branches of the US government — and foreign intelligence services — who have had contact with the prisoners. Lest we forget, the men held at Guantánamo have never been allowed to have family visits, unlike prisoners held on the US mainland — even those convicted of horrendous crimes — and so often the lawyers have been the only people capable of filling the gap left by relatives, and, of course, bringing messages from the men’s families, which has happened time and again as lawyers have visited their clients’ families, and have subsequently been the bearers of their relatives’ communications.

Recently, a new lawyer brought some fresh insight and indignation to a role that many of those involved in must be struggling to keep fresh, after so many years, after the exhaustion of eight years of Obama that, in the end, left the prison open, and with Trump so uninterested in doing anything to bring justice to the remaining 41 prisoners, either by releasing them or putting them on trial in a valid, internationally recognized system, or working towards shutting the prison once and for all.

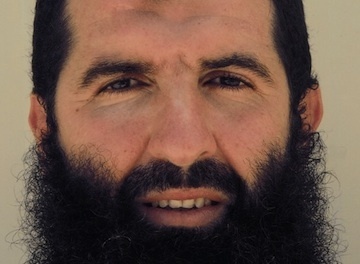

Noor Zafar is a Bertha Justice Institute Fellow at the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights, working on litigation challenging government abuses in national security. She recently wrote an article for Mother Jones about visiting one of the remaining prisoners, Sufyian Barhoumi, an Algerian whose case I have followed since I began researching and writing about Guantánamo over eleven years ago.

I discussed him in my book The Guantánamo Files, published in 2007, I followed his brief time as a candidate for a trial by military commission in Bush’s last year in office, I wrote about him having his habeas corpus petition turned down (in 2009 and 2010), I wrote about him in 2013 when he asked to be charged with something — anything — so he might get out of Guantánamo, and I also wrote about him last year, when his case was considered by the second review process set up by President Obama, the Periodic Review Boards, leading to a recommendation for his release.

As a result of my coverage of Barhoumi’s case, I knew he was an extremely well-behaved prisoner, an avid footballer, and “a natural diplomat,” as another of his lawyers, Shayana Kadidal, put it, who was well-liked by the guards at Guantánamo. What I didn’t know, which Noor Zafar reveals, is that, after his PRB result, he “was so sure of his impending departure that he distributed his possessions, including his prized wristwatch, as farewell gifts to his fellow detainees.”

The disappointment must have been immense when he wasn’t actually released, and has now found himself once more entombed as Donald Trump has shut the door on Guantánamo, but as Zafar explains, despite this, “[h]is tranquility and sense of perspective are remarkable. When he talks about his future, it is evident that he is drawing upon a reservoir of strength and optimism he has cultivated during his years in detention.”

I hope you have time to read Zafar’s article, which I’m cross-posting below. One passage which leapt out at me was a painful lesson learned about the limits of justice in America today. As Zafar puts it, “Guantánamo is a testament to what three years of legal education did not teach me: the powerful can twist the law beyond recognition to validate unjust outcomes.”

My Visit With One of the Forgotten Prisoners of Guantánamo

By Noor Zafar, Mother Jones, July 14, 2017

15 years later, the detention camp has become a place where time has no meaning.

Last month, I took my first trip to the US military detention camp at Guantánamo Bay to visit Sufyian Barhoumi. As a military handler drove me and my colleagues from the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) down the winding road from the ferry landing to the camp, I marveled at the lush green hills and sparkling blue water around us. The serenely beautiful setting stands in stark contrast to the detention camp, which is jarringly ugly: Endless rolls of rusty barbed wire, layers of fencing enmeshed with opaque green cloth, cages with peeling paint, gravel pits where grass should be. A warehouse to store men we don’t know what to do with.

Guantánamo is a sprawling network of several smaller detention camps. Many of the camps, such as Camp Iguana, where children were held, are no longer in use. Currently, detainees are housed in two different camps. Fourteen “high value detainees,” who were interrogated at the CIA’s notorious “black sites” prior to being shipped to Guantánamo, are held in Camp 7. The rest, like Sufyian, are held in Camp 6. At Camp Echo, the site designated for client meetings, my colleagues and I are ushered into a tiny office. We submit our papers to a member of the Privilege Review Team (PRT), who must approve and stamp them before we can bring them into our meeting. The detainees and anyone who interacts with them are subject to a gag order. Very little information is allowed in, and very little is allowed out.

Attorneys must obtain security clearances to meet with their clients because everything the detainees say is presumptively classified, even now, a decade and a half after they were brought here. The PRT must ensure that their utterances don’t pose a threat to national security before they can be declassified and shared with the public. I applied for my clearance to see Sufyian a few months before I graduated from law school; it took nearly 10 months to process.

When we are led in to the meeting area, Sufyian stands to greet us. We quickly ease into conversation. When he smiles, he wrinkles his nose and reveals a wide grin through his salt-and-pepper beard. Sufyian is an avid soccer player, and when I ask about his reputation as the best striker in Guantánamo, he smiles sheepishly and looks at the floor. He explains that now, at 43, he is getting too old to play. With fewer men left in Sufyian’s camp, they can no longer field a full team for a match.

Sufyian, who is originally from Algeria, has been detained without trial at Guantánamo for 15 years. As a young man, he lived in Spain, France, and England, working as a farm worker and a street merchant. Sufyian was captured in March 2002 in Faisalabad, Pakistan. Military prosecutors charged him three times with allegedly training would-be insurgents on how to make improvised explosive devices , but each time those charges were dropped for lack of evidence. In 2012, tired of waiting for the government to decide what offense he had committed, Sufyian offered to plead guilty to anything in order to get a release date.

Finally, in August 2016, Sufyian was cleared for transfer by the Periodic Review Board, an administrative body comprised of officials from six national security agencies who review detainees’ eligibility for release. It was expected that he would soon be sent back to Algeria to be reunited with his mother and siblings. Sufyian was so sure of his impending departure that he distributed his possessions, including his prized wristwatch, as farewell gifts to his fellow detainees.

But bureaucratic recalcitrance cost Sufyian his freedom. In the final week of Barack Obama’s presidency, CCR filed an emergency motion asking the D.C. district court to waive congressional restrictions on detainee transfers (such as the requirement that the Secretary of Defense certify that no released detainee would commit any harmful acts) and direct the government to release Sufyian. Despite the Obama administration’s authority to bypass the certification requirement and incoming President Donald Trump’s promise to halt all transfers from Guantánamo, the government opposed CCR’s motion. Ultimately, the court sided with the government. Sufyian, along with 40 other men, 4 of whom are cleared for release, are currently stranded in Guantánamo.

The erasure of Guantánamo from our public consciousness, mirrored by the prison’s physical deterioration, is unsettling. During the Bush administration it became synonymous with torture and lawlessness, but the Obama administration whitewashed the brutality of indefinite detention through a steady flow of human rights rhetoric and legalisms. President Obama claimed he wanted to shutter the prison but was unwilling to take the political risk of bypassing an obstructionist Congress in order to do so. Now, President Donald Trump has not only said he will keep Guantánamo open, he has promised to “load it up with some bad dudes.”

Responsibility for the failure to close Guantánamo lies with all three branches of government, but the ultimate enabler has been apathy. Federal courts, in particular, have been complicit in Guantánamo’s continued operation by abdicating their role as a check on executive power. The jurisprudence that has crystallized in the Guantánamo detainees’ cases is so deferential to the government that it ensures no detainee may be set free as the result of a court order. Beyond embodying the failure of the rule of law, Guantánamo is a testament to what three years of legal education did not teach me: the powerful can twist the law beyond recognition to validate unjust outcomes. There is no other way to explain why Sufyian is still detained today.

When we ask Sufyian how he is doing, given the new political reality, he points towards the ceiling and makes a gesture of supplication. “Alhamdulillah,” he repeats several times — praise be to God. His tranquility and sense of perspective are remarkable. When he talks about his future, it is evident that he is drawing upon a reservoir of strength and optimism he has cultivated during his years in detention.

With Ramadan approaching, Sufyian requests various treats to give his fellow detainees as they break their fasts — chocolates, Nutella, strawberry Nesquik. Ultimately, though, the conversation always comes back to a replacement for the watch he gave away.

Legal visits like this one have become a weird formality. Both attorneys and detainees are acutely aware that the law will not lead to freedom. The promise of Boumediene v. Bush, the landmark 2008 Supreme Court ruling that granted Guantánamo detainees the right to challenge the legality of their detention in federal court, has faded. On the rare occasions where detainees’ habeas corpus petitions have been granted, they have been reversed on appeal. When the government has not appealed unfavorable rulings, it has dragged its feet in securing transfers, causing technically free men to languish.

The importance of pursuing legal challenges lies in creating opportunities for detained men to tell their stories. Much of the shift in narrative that occurred in the late Bush and early Obama years was the result of lawyers presenting detainees to the world as human beings deserving of basic dignity. At Guantánamo, the role of the lawyer is as much storyteller as it is litigator.

There is something odd about standing in Guantánamo’s Naval Exchange grocery store deciding whether to buy white or whole wheat pasta, or walking through the gift shop with its displays of shot glasses and stuffed toys, while being so close to men who have had years of their lives stolen from them. As a Muslim woman who grew up in post-9/11 America, Guantánamo will always be a place of orange jumpsuits, black hoods, and dog-kennel cages — a place where Muslim men and boys were sent to be interrogated, tortured, and imprisoned. It is the foundation on which the US government constructed its “Global War on Terror” against mythical superhuman Muslim terrorists. This is the Guantánamo that recklessly expanded presidential power and spurred the blockbuster Supreme Court cases we dissected in my Con Law class. I expected it to be more imposing, the sense of injustice more palpable.

Every aspect of our visit — taking the ferry across the bay to the prison each morning, eating lunch at Subway for four days straight, frantically shopping at the Naval Exchange for items requested by our clients — feels sterile, routine, mechanic. The layers of bureaucracy separating attorney from client, from the security clearance down to the button we must press to summon a guard to let us out of the meeting room, drain any sense of normalcy from what should be a basic human interaction.

The only time I felt fully human while at Guantánamo was when meeting with Sufyian. When Sufyian told us about his friend, an ailing 71-year-old detainee from Pakistan, or when he spoke with sadness and hope about his desire to see his mother again, I felt a jolt of emotion that reassured me that I hadn’t yet succumbed to the hollowness of this place.

When our meeting time ends, Sufyian stands up, as if we are his guests and he is going to escort us to the door. His left leg is chained to the floor, so he shuffles a few inches and we say our goodbyes. “See you — what’s the Urdu word for ‘tomorrow’?” Sufyian asks me, picking up on an earlier part of our conversation in which he showcased his budding knowledge of Urdu after learning that it was my native tongue. “Kal,” I say. “Hum kal milengay.” We will meet again tomorrow.

The windowless armored van that will transport Sufyian back to his cell is waiting outside. When the detainees are brought to and from the meeting area, they are blindfolded, shackled, and escorted by a group of guards in full gear. While the entire spectacle is ridiculous, I don’t understand why the men are deprived of catching even a glimpse of the beautiful island on which they are held captive. But then, the answer behind the many absurdities of Guantánamo is usually “national security.”

On our last day at Guantánamo, as we ride the yellow school bus making endless loops around the base, we see a C-17 taxiing on the runway. My colleague remarks that, prior to Trump’s inauguration, C-17s were a sign of hope. Whenever detainees were about to be transferred, they would be brought to the airport — in the middle of the night, blindfolded and shackled just as when they first arrived — and then put into a plane like this one.

I think of the watch I’ll bring Sufyian on my next visit. A strange request for a man who is being detained indefinitely at a prison where time has been rendered meaningless. Amid this crushing uncertainty, I try to latch on to Sufyian’s insistence that, when it is meant to be, he will be free. As I watch the C-17 take off, I dare myself to imagine the day Sufyian will be flying somewhere far away to resume the rest of his life.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp. He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp. He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

August 2, 2017

My Photos: The Wet But Still Wonderful WOMAD Festival 2017

See my photo set on Flickr here!

The WOMAD festival (World of Music, Art and Dance) takes place on the last weekend of July, and since 2002 I have attended the festival every year — first at Reading, and, since 2007, at Charlton Park in Wiltshire — with my family and friends, as my wife runs children’s workshops, culminating in the children’s procession on Sunday evening that snakes through the entire festival site.

I’ve taken photos of the festival every year, and have made them available on Flickr since 2012 — see the photos from 2012 here and here, from 2014 here, from 2015 here, and from 2016 here.

This year the weather was quite challenging, but we all had a great time anyway. The camaraderie was great in our camp, and there was wonderful music everyday — starting on the Thursday night before most people were there with my favourite band of the festival, who I had never heard of before — Bixiga 70, a Brazilian Afrobeat band — and an old favourite, Orchestra Baobab, from Senegal, and continuing with Junun (from Israel and Rajasthan) and Oumou Sangare (from Mali) on Friday, young rapper Loyle Carner (from Croydon), kora legend Toumani Diabate (from Mali) and Toots and the Maytals (from Jamaica) on Saturday, and whirling dervishes from Syria, Benjamin Zephaniah from the UK, Seun Kuti and Egypt 80 from Nigeria, and US vibes legend Roy Ayers on Sunday.

My son Tyler also performed, at the Hip Yak Poetry Shack, and there was a wonderful procession, featuring the phoenix Dot designed. My band The Four Fathers missed the boat when it came to the Open Mic at Molly’s Bar, where we’ve played before, but we did play at the camp, along with other musically-inclined campers.

If you haven’t yet been to a WOMAD festival, I can’t recommend them highly enough. Please check out the UK site, and also the international site for other events worldwide.

Also see the album here:

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp. He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp. He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

July 26, 2017

Off to WOMAD, Back on Monday! Have A Listen to The Four Fathers While I’m Away

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist and commentator.

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist and commentator.

Dear friends,

It’s that time of year again, when a whole posse of us from south east London head down to Charlton Park in Wiltshire for the WOMAD world music festival, which this year is celebrating its 35th year!

This will be my 16th annual visit, as part of a group of family and friends running children’s workshops, led by my wife Dot. I first went just after our wedding, and have been every year since — in the festival summers of 2004 and 2005, for example, when I launched my books Stonehenge: Celebration & Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield at the Glastonbury Festival, and also spoke and sold books at the Big Green Gathering and the Shambala Festival, and in 2007, the first year at Charlton Park, after the move from Reading, when it became a mud bath, and we feared it might not survive.

But this “hardy celebration of music marginalised by the western pop machine”, as the Times describes it, is not so easily destroyed. WOMAD came bouncing back in 2008, having redesigned its place in the landscape of Charlton Park, and it has been thriving ever since.

I find it hard to imagine that I could love a festival more than WOMAD. I love world music, rather more than most western music, and WOMAD constantly surprises, delivering up music I didn’t know beforehand that ends up blowing me away — and I know it’s the same for thousands of other people. Check out my archive of photos and recollections here.

West African music is a particular love of mine — joining roots reggae, particularly from the late 70s, as musical themes that continually resonate in my life, along with an esoteric timeline of rock and pop music that has never abandoned me since my days of watching Top of the Pops as a child, and the Old Grey Whistle Test as teenager, and the time I spent from 1977 onwards devouring all kinds of albums — rock, pop, punk, new wave, soul and disco — then, at university, the great singer-songwriters, and the unforgettable pulse of roots reggae.

This love of reggae — and some punk sensibility and the poetic leanings of the singer-songwriter — have never left me, and I hope, on Sunday, to be playing a few songs at the open mic at Molly’s Bar with Richard Clare of my band The Four Fathers (where all my music loves have been colliding since 2014), our former bassist, Louis Sills-Clare, and my son Tyler (The Wiz-RD), a beatbox poet.

While we’re away, do feel free to check out our music. Below are the videos we recently made available of two songs we regularly perform live — our cover of Bob Dylan’s ‘Masters of War’ and ‘Rebel Soldier’, an old folk song that I gave a new tune, and a reggae rhythm, while living in Brixton in the 1980s. Both are on our first album, ‘Love and War.’

Please also check out our studio recordings, including our latest releases, ‘Riot’, a warning to the Tories about the effects of their austerity programme, and ‘London’, a love song to the capital over 30 years, as its wildness has been lobotomised by greed, from our forthcoming second album, ‘How Much Is A Life Worth?’ which we’ll be releasing in September.

See you on Monday!

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp. He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp. He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

July 25, 2017

Video: Architects for Social Housing’s Powerful Public Meeting, ‘The Truth About Grenfell Tower’, and Their Detailed Report

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist and commentator.

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist and commentator.

On June 22, a week after the dreadful Grenfell Tower inferno in west London, which I wrote about here and here, Architects for Social Housing (ASH), an organisation set up two years ago to oppose the demolition of housing estates for profit, and for social cleansing, which, instead, can be refurbished, held an open meeting to examine what caused the Grenfell fire, and what lessons can and must be learned from it.

I attended that meeting, in the Residents Centre of Cotton Gardens Estate in Lambeth, which was attended by around a hundred people, including residents, housing campaigners, journalists, lawyers, academics, engineers and architects. It was an articulate and passionate event, and I’m delighted that an edited film of the meeting is now available on YouTube, made by the filmmaker Line Nikita Woolfe (with the assistance of Luc Beloix on camera and additional footage by Dan Davies), produced by her company Woolfe Vision.

The meeting was hosted by Geraldine Dening and Simon Elmer of ASH, and a prominent guest was the architect Kate Macintosh, who, at the age of 28, designed the acclaimed Dawson’s Heights estate in Dulwich. Her late husband, George Finch, designed Cotton Gardens, another acclaimed estate, and one whose structural integrity, it became apparent at the meeting, had not been compromised as Grenfell Tower’s had, with its chronically ill-advised refurbishment leading, in no uncertain terms, to the terrible and entirely preventable loss of life on June 14.

The 80-minute video is posted below, and I wholeheartedly recommend it to anyone interested in what happened at Grenfell and why — and what we can do about it.

ASH have also produced a powerful report (also here as a PDF) following on from the meeting, in which they follow up on the four themes of the meeting:

1) to share what we know collectively about the technical causes of the Grenfell Tower fire;

2) to expose the management structures and political decisions that allowed these technical conditions to be in place;

3) to advise residents of council tower blocks on the safety or otherwise of their homes, and what changes need to happen in order to stop such a disaster ever happening again;

4) to organise opposition to the use of the Grenfell Tower fire to promote London’s programme of estate demolition.

In their report, they pull no punches, forensically analysing the greed, the deregulation (the “red tape” the Tories so gleefully boasted about getting rid of), the absurd self-certification processes that have replaced anything resembling accountability in the private sector’s multi-faceted takeover of social housing, and the murderous indifference of the council and the management organisation responsible for all of Kensington and Chelsea’s social housing, to name just a few of the more prominent themes investigated.

A few key passages leapt out at me as I read this compelling report — the senior architect, who wished to remain anonymous, but who wrote that, at Grenfell, those responsible for the refurbishment of the tower “might as well [have] clad the building in ten-pound notes dipped in Napalm,” and this passage, from that same architect, about PFI:

Since PFI was introduced by Thatcher we have a legacy of hundreds, if not thousands, of sub-standard buildings – schools, hospitals, police stations, etc – that the taxpayer is still paying extortionate rents for under the terms of the 30-year lease-back deal that is PFI. This is her legacy of cosy relationships between local authorities, quangos and their chummy contractors. It is a culture of de-regulation, of private profit before public good … what the public must demand and get now over the Grenfell Tower fire are criminal convictions, and soon.

I was also aware that the following discovery, based on analysis of Grenfell and the surrounding area, is never reported in the mainstream media — that “crime levels on council estates are in fact consistently lower than in the surrounding area, contradicting everything we are told about council estates and their communities by terrace-dwelling journalists and developer-lobbied politicians. Not only are estates not ‘breeding grounds’ for crime, as they are characterised in both Fleet Street and Westminster, but the close-knit communities that form within them significantly reduce crime rates.”

There are other passages that leapt out at me — the following, for example — but I do encourage you, if you can find the time, to read the whole report:

The Grenfell Tower fire was not an accident but an inevitable result of the managed decline of council estates as a principle of our housing policy, the deliberate neglect of maintenance to homes preparatory to their demolition and redevelopment, and the unaccountability of councils, tenant management organisations and the private contractors they employ to the concerns and even the lives of residents. From the government’s Estate Regeneration National Strategy and the London Mayor’s Good Practice Guide to Estate Regeneration to the individual schemes of London’s councils, existing policy is to demolish our estates, evict their residents and redevelop the land as luxury apartments for home ownership and capital investment. If – as politicians never tire of telling us – we must ‘learn the lessons’ of this man-made disaster, we should start by stopping the social cleansing of communities like that of Grenfell Tower and start investing in the maintenance, refurbishment and security of London’s council estates and the residents who call them home. Our homes need maintaining by accountable and repesentative bodies, not managed decline by private management and developers trying to profit from this disaster.

After coming up with “a starting list of the more than 60 individuals we believe should be immediately arrested by the police and their records seized, investigated for their role in the Grenfell Tower fire, and where necessary put on trial in a criminal court,” including private contractors and consultants on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment, board members and directors of the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation, councillors and officers on Kensington and Chelsea Council, and Members of Parliament and civil servants, the report concludes with the following paragraphs:

What the Grenfell Tower fire has exposed is that the separation between the public and private spheres in UK housing no longer exists in any qualifiable sense, and any trust we may once have had that the duties of the former are independent of the interests of the latter has no foundation in practice. From our work with council estate communities trying to save their homes, and from our own experience of living on council estate tower blocks, ASH has become increasingly interested in the potential of a third sphere of activity, which is neither public nor private. What those commentators on council estates who live – to use Andrew Gimson’s description – in their ‘little terraced houses’ do not understand is that the most important space on a council estate does not fall into the clear distinction between private and public that terrace-dwellers cross every time they step outside their home and into the street. In seeking to recreate the street life of working-class communities, post-war council estates designed communal spaces into their architecture. These include not only the community halls in which residents meet – and which because of this are always the first part of the estate to be shut down by councils intent on demolishing it – but the internal hallways and external walkways between individual homes; the numerous landings outside lifts; the lifts themselves – where in the few seconds it takes to ascend or descend relationships with neighbours are made and maintained; and above all in the entrance halls – in many cases later additions to address the teething problems of this new form of communal living – and in which the concierge, known to every resident and therefore knowing every resident, is the presiding spirit of the estate, setting the tone for its cordiality, its fraternity and its ethos of mutual support.

All of this is unknown to the dwellers in privately-owned homes and fenced-in gardens; but it is where the collective life of a council estate takes root and grows. Most importantly, it is a space which is neither private, and therefore subject to the property or tenant rights of the individual or household, nor public, and therefore the province of the council. Rather, it is a collective space, over which no resident has rights, which none of them own, but for which they all take responsibility and share in its benefits. As the corruption of the public sphere by the private accelerates under increasingly accommodating government policy, mayoral direction and council practice, and the lives of those under the management and care of these public bodies are increasingly put at risk of eviction, homelessness and even death, ASH believes this third sphere, the space and activity of community, must be reclaimed.

Once the charred skeleton of Grenfell Tower is buried and the land cleared for redevelopment, it will still be in the hands of Kensington and Chelsea council. Worse still, the fire has brought about precisely that demolition of the ‘blight’ that Grenfell Tower, in the eyes of the council and the TMO, represented, freeing up the land it stands on for the potential residual values the original masterplan for the Lancaster West estate envisaged activating through its redevelopment as ‘high end’ properties for home ownership and capital investment. Were this to come about – and under existing ownership and policy there is nothing to stop it happening – it would be the greatest betrayal of both the dead and the survivors of the Grenfell Tower fire.

To oppose this, therefore, ASH proposes that a portion of the £20 million donated by the general public – and which the government should be invited to match – be used to purchase the land on which Grenfell Tower stands and place it in Trust for the survivors and the surrounding community; and that in its place housing is built that is neither owned by the council nor run by the KCTMO, but owned and managed as a Community Land Trust or Housing Co-operative by the residents themselves. From the ashes of Grenfell Tower, and the forces of private greed and public corruption that burnt it to the ground, a new Community estate could rise – as a home for the homeless of Grenfell Tower, and as a model of communal housing for the hundreds of thousands of Londoners currently threatened by the programme of estate regeneration.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp. He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp. He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

July 24, 2017

Six Months of Trump: Is Closing Guantánamo Still Possible?

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

Just a few days ago, we passed a forlorn milestone: six months of the presidency of Donald Trump. On every front, this first six months has been a disaster. Trump humiliates America on the international stage, and at home he continues to head a dysfunctional government, presiding by tweet, and with scandal swirling ever closer around him.

On Guantánamo, as we have repeatedly noted, he has done very little. His initial threats to send new prisoners there, and to revive CIA “black sites,” have not materialized. However, if he has not opened the door to new arrivals, he has certainly closed the door on the men still there.

These include, as Joshua A. Seltzer, the senior director for counterterrorism at the National Security Council from 2015 until Trump took office, wrote in “Is Closing Guantánamo Still Conceivable?,” a recent article for the Atlantic, “the five still held at Guantánamo despite being recommended for transfer.” He added, “This official designation refers to those still believed to be lawfully detained under the law of war, but unanimously recommended for repatriation or resettlement by an interagency group of career officials. In other words, their continued detention has been deemed unnecessary, assuming an appropriate country can be identified to accept them under conditions that ensure their humane treatment and address any lingering threat they might pose.”

Seltzer continued: “Trump has couched his refusal to continue with this process as part of his near-wholesale rejection of Obama and his presidency. His campaign pledge to fill the detention facility was preceded by a direct reference to his predecessor: ‘This morning, I watched President Obama talking about Gitmo,’ Trump began, before making clear that his desire to keep it open was diametrically opposed to Obama’s wish to close it.”

That was the speech in which Trump said of Guantánamo, “we’re gonna load it up with some bad dudes, believe me, we’re gonna load it up,” and, even after he took office, the wild rhetoric continued. In March, as we wrote about here, he tweeted an outrageous lie about Guantánamo — “122 vicious prisoners, released by the Obama Administration from Gitmo, have returned to the battlefield. Just another terrible decision!”

As we explained at the time, “That number, 122, was taken from a two-page ‘Summary of the Reengagement of Detainees Formerly Held at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba,’ issued by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence in July 2016. The summaries are issued twice a year, and, crucially, what Trump neglected to mention is that 113 of the 122 men referred to in that summary were released under President Bush, and just nine were released under President Obama. In the latest ODNI summary, just released, the total has been reduced to 121, with just eight men released under President Obama.” (We should add that, here at “Close Guantánamo,” we also dispute the figures compiled by the ODNI).

“Rebuking a bipartisan project”

However, what is important about Trump’s position is not just his stupidity, or his wholesale opposition to whatever position was taken by President Obama; it is also, as Seltzer explains, that it is in opposition to the settled, bipartisan view of almost the whole of the US establishment.

As he puts it, “closing Gitmo isn’t just an Obama position.” George W. Bush, who opened it, “expressed support for shutting it down in 2006,” and “[b]oth candidates in the 2008 presidential election backed its closure … By breaking with longstanding efforts to repatriate or resettle detainees, Trump has refused to act on the recommendations of career national security professionals. He isn’t simply rejecting an Obama policy, as he claims. He is, instead, rebuking a bipartisan project.”

Seltzer’s sharp analysis continues: “Trump’s Guantánamo policy is a microcosm of his approach to so much, particularly in foreign affairs and national security policy. His reluctance to endorse America’s commitment to NATO’s collective self-defense (a reluctance he seems to have reversed recently), his similarly pointed efforts to rile its NAFTA partners without articulating a credible alternative, his seemingly concerted abnegation of American commitments to international partnerships and assumption of leadership in global affairs — he frames all of this as a rebuke of Obama’s purported ’weakness and irresolution’ when, in fact, it is a stark rejection of vital, bipartisan elements of America’s approach to world affairs. Trump’s foreign policy isn’t anti-Obama. It’s anti-everyone other than his own small and somewhat bizarrely oriented team of advisers.”

Seltzer proceeds to note that, worryingly, Trump’s position on Guantánamo “plays to the small streak of American political discourse that imbues the detention facility’s continued operation with inordinate symbolic value in the war on terror,” a “post-9/11 American toughness towards terrorism, and more specifically, a militarizing of that effort,” which, in turn, “represents an American commitment to ‘taking the gloves off’ when it comes to counter terrorism and minimizing the legal rights afforded to terror suspects.”

As he describes it, “Never mind the federal courts’ well-established, successful track record of prosecuting terrorism suspects; those with an unwavering committment to the Guantánamo project embrace its symbolism, regardless of the history and facts.” He then cites Ed Meese, Attorney General under Ronald Reagan, from 1985-88, who suggested, on the 10th anniversary of the establishment of the Guantánamo prison (the very day that “Close Guantánamo” was established), that Guantánamo helps Americans “remember that the United States is engaged in armed conflict and has been since September 11, 2001.” As Seltzer puts it, “In Meese’s telling, the facility is a concrete reminder that the war on terror ‘would be different from all previous wars,’” an echo of the alarming position taken by the Bush administration, which continues to poison America’s commitment to the rule of law (including spurious justifications of Guantánamo’s continued existence).

Seltzer proceeds to note that the current Attorney General, Jeff Sessions, has been “[p]erhaps the single most consistently vocal supporter” of the Guantánamo project, pointing out that, “soon after being sworn in, [he] reaffirmed his longstanding view that Guantánamo is ‘a perfect place’ to send newly detained terrorism suspects.”

In Seltzer’s analysis, this is another example of Trump “indulging a fringe view of what threatens Americans and what keeps them safe,” echoing “his determination to take the legal fight over his anti-Muslim travel ban all the way to the Supreme Court, over strong indications from a range of former national security professionals that such a response simply isn’t responsive to today’s actual terrorist threats.” (Seltzer adds that he is one of those former national security professionals).

Moreover, Trump’s position is not merely bad domestic politics; it is also, as Seltzer adds, counterproductive. That is how the former officials describe the Muslim ban, and Seltzer also notes that his “experience as a White House counterterrorism official under Obama confirms others’ observations that continued detention at Guantánamo makes it harder for key partners to help America with real counterterrorism needs.”

In a key condemnation of Trump’s position, he notes, “This is playing politics with national security, not protecting it.”

Seltzer proceeds to concede that “neither of Trump’s predecessors pursued a headlong dash to close the facility,” adding that, under Obama, this was “sometimes to the frustration of those outside government for whom Guantánamo’s closure was an urgent moral issue, even if one that the reality of congressional politics would simply not allow.” That ignores, as we stated from when we first started campaigning in January 2012, the reality that a presidential waiver existed in the legalisation that Congress produced to tie Obama’s hands, which, sadly, he chose never to use.

Seltzer also writes of “a sometimes slow but justifiably cautious process for evaluating which detainees could be transferred and under what conditions, and then for pursuing such transfers.” He adds, “That was what our counterterrorism partners wanted to see from us: the journey, if not the destination. So long as those governments could tell themselves and their citizens that Washington was considering the transfer recommendations of career officials, Guantánamo generally didn’t represent a stumbling block to the type of cooperation on which counterterrorism inevitably relies.”

That latter point may well be true, but on the review process, Seltzer’s position ignores the layers of unjustifiably extreme caution that meant that men approved for ongoing imprisonment under Obama’s 2009 review process (the Guantánamo Review Task Force), when they were designated as being “too dangerous to release,” had to wait, in many cases, for another six or seven years until the second Obama review process, the Periodic Review Boards, decided that, after all, they were not too dangerous to release, and, in many cases, the supposed intelligence used to justify their ongoing imprisonment was hopelessly flawed.

In conclusion, Seltzer claims that, although “it’s easy to view [Guantánamo] as a place frozen in time,” it “remains a dynamic place. Reviews of detainees and the threat they may pose are ongoing, and those may yield additional recommendations for transfers beyond the five detainees already in that category. And, just last month, new military commissions charges were filed against a detainee, making him the 11th current detainee to be at some stage of military commissions proceedings.” As we noted in a recent article, however, the decision to charge alleged al-Qaeda terrorist Hambali in the military commissions is nothing to celebrate, as the system remains irreparably broken. As a Trump administration official told Spencer Ackerman of the Daily Beast, “This system doesn’t work.”

A federal court trial that punctures Trump’s rhetoric

Since Seltzer filed his article for publication, there has been a development that shows, more appropriately, Trump’s rhetoric being undermined by political reality. Despite his bombastic claims that he would bring new prisoners to Guantánamo, he has just “brought a man suspected of belonging to Al Qaeda to the United States to face trial in federal court, backing off [his] hard-line position that terrorism suspects should be sent to the naval prison in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, rather than to civilian courtrooms,” as the New York Times put it.

The Times added, “The suspect, Ali Charaf Damache, a dual Algerian and Irish citizen, was transferred from Spain and appeared on Friday in federal court in Philadelphia, making him the first foreigner brought to the United States to face terrorism charges under President Trump,” also noting that he is a suspected recruiter for al-Qaeda, who “was charged with helping plot to kill a Swedish cartoonist who depicted the Prophet Muhammad in cartoons.”

The Times also noted, “With Mr. Damache’s transfer, Attorney General Jeff Sessions adopted a strategy that he vehemently opposed when it was carried out under President Barack Obama. Mr. Sessions said for years that terrorism suspects should be held and prosecuted at Guantánamo Bay. He has said that terrorists did not deserve the same legal rights as common criminals and that such trials were too dangerous to hold on American soil. But the once-outspoken Mr. Sessions was uncharacteristically quiet on Friday. He gave a speech one block away from the Philadelphia courthouse where Mr. Damache appeared and did not address the case.”

This is one commendable instance of reality intruding on Trump’s fantasy view of justice — echoing what happened with his enthusiasm for torture, when even his own appointees opposed him — but it remains clear that, in general, his approach to Guantánamo remains disastrous. As Seltzer notes, in closing, “another six months of Trump’s approach to Guantánamo will, whatever his rhetoric professes, leave the country less safe — not more.”

We cannot agree more.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp. He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp. He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

July 21, 2017

“Choose Peace”: An Inspiring Message of Tolerance From Former Guantánamo Prisoner and Torture Victim Mustafa Ait Idir

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Last year, I was honored to be asked to write a short review to promote a Guantánamo memoir by two former prisoners, Lakhdar Boumediene and Mustafa Ait Idir, two of six Algerians living and working in Bosnia-Herzegovina, who had been kidnapped by the US authorities in January 2002 and flown to Guantánamo, where they were severely abused. The US authorities mistakenly thought they were involved in a plot to bomb the US embassy in Sarajevo, despite no evidence to indicate that this was the case. Before their kidnapping, the Bosnian authorities had investigated their case, as demanded by the US, but had found no evidence of wrongdoing. However, on the day of their release from Bosnian custody, US forces swooped, kidnapping them and beginning an outrageous ordeal that lasted for six years.

Five of the six — including Boumediene and Ait Idir — were eventually ordered released by a federal court judge, who responded to a habeas corpus petition they submitted in 2008, after the Supreme Court granted the Guantánamo prisoners constitutionally guaranteed habeas corpus rights, by telling the US government, in no uncertain terms, that they had failed to establish that they had any connection to Al-Qaeda or had any involvement in terrorism.

Ait Idir, who had worked for Qatar Charities in Bosnia before his capture, where he had been widely recognized as a talented athlete and coach, was returned to his wife and family in Sarajevo, where he is now a computer science teacher at a secondary school, while Boumediene, an aid worker for the Red Crescent Society in Bosnia before his kidnapping, who gave his name to the Supreme Court case establishing the prisoners’ habeas rights, was resettled in France in May 2009.

Two of the other three, Mohammed Nechle and Boudella al-Hajj, were released with Ait Idir in Bosnia in December 2008, just after the ruling, while another joined Boumediene in France in November 2009. The sixth man, Belkacem Bensayah, whose ongoing imprisonment had been upheld by the judge in 2008, won his appeal in 2010, vacating the ruling, but his case was never reconsidered. He was finally released in Algeria (against his will) in December 2013.

Ait Idir and Boumediene’s memoir, Witnesses of the Unseen: Seven Years in Guantánamo, is an extraordinary indictment of the US authorities’ incompetence and brutality after the 9/11 attacks, which I wholeheartedly recommend. As I stated in my review:

Lakhdar Boumediene and Mustafa Ait Idir are two of the most notorious victims of the US’s post-9/11 program of rendition, torture, and indefinite detention. Kidnapped on groundless suspicions, they are perfectly placed to reflect on the horrors of Guantánamo and the “war on terror.” With a warmth and intelligence sadly lacking in America’s treatment of them, this powerful joint memoir exposes their captors’ cruelty and the Kafkaesque twists and turns of the U.S. government’s efforts to build a case against them.

Last week, Mustafa Ait Idir was given an opportunity to send a message to the US people via a column in USA Today, which he delivered with eloquence, and an extraordinary sense of tolerance and dedication to peace. In this he is not alone. Numerous former prisoners have emerged from the prison to spread a message of peace, and not, as so many US and Western observers expect, to be consumed by bitterness.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi, for example, the best-selling author of Guantánamo Diary, who was subjected to a particularly harsh program of torture in Guantánamo, under the mistaken belief that he was member of al-Qaeda, recently told his editor, Larry Siems, that he forgave everyone who had mistreated him, because otherwise he would be poisoned by hatred, which would eat away at him. Those obsessed with vengeance — like those who seem unable to move on from the trauma of 911 — would do well to take heed of his comments.

Mustafa Ait Idir’s op-ed is posted below, and I do hope you have time to read it, and that you’ll share it if you find its message of hope and forgiveness useful.

Former Guantánamo Bay prisoner message to Muslims: No suffering can justify terrorism

By Mustafa Ait Idir, USA Today, July 13, 2017

There are those who ask why more Muslims haven’t spoken out against terror, all the while covering their ears so as not to hear those of us who do.

After illegally seizing me from my family in Europe, the American government held me in an island prison for almost seven years. During those years, I experienced and observed unspeakable suffering and abuse. I was bewildered and angry; America was torturing and tormenting me for no reason at all. It was as though no one cared that I had never wished harm on anyone. My innocence made no difference.

My oldest son first learned I was in Guantánamo when his classmates, having read an article about me online, mocked him about my plight. Another of my sons, born a few months after I was interned, first met me on the telephone. I missed the first six years of his life. As much as anyone, I have earned a right to rage against an American government that acted out of fear and prejudice. A government that, as we saw with Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ visit to Guantánamo last week in apparent preparation to refill it with prisoners, sadly has yet to demonstrate a capacity to learn from its mistakes.

And so I hope I have earned the right to be taken seriously when I say this, to any of my Muslim brothers and sisters, and to anyone else, contemplating violence: I beg of you, choose peace. Whatever complaints one might have about particular policies and politicians, and I assure you I have several, violence will only make matters worse.

The bigots and fear-mongers, the Donald Trumps and Dick Cheneys, are emboldened and empowered by acts of terror. And no matter what you have been through, regardless of what hell you have been forced to endure, nothing could possibly justify propelling nails into a throng of teenagers, ramming a bus into a crowd, or flying a plane into a building. It is one thing to be upset, even enraged; it is another to be heartless. Neither Allah nor any god of any religion could ever support such cruelty to our fellow man.

I worry that this plea may fall on deaf ears, or rather, ears that are capable of hearing but unwilling to listen. And I wonder if my voice will also be ignored, as countless others have, by those who find it easier to think of all Muslims as bad.

There are those who ask why more Muslims haven’t spoken out against terror, all the while covering their ears so as not to hear those of us who do. There are those who support unfair measures that prevent people from entering the United States because they are Muslim, and who defend or even promote Guantánamo. Those people, through their words and deeds, lend weight and voice to the extremists and drown out the rest of us. This is exactly what the extremists want.

But I am home again with my wife and family, and I have overcome far too much to give up hope now. Violence is not inevitable. I am a schoolteacher, and I know that children will only learn to hate if adults teach them to. Right now there are young Muslims deciding whether to hate the West, and young Westerners deciding whether to hate Islam. There are voices, including mine, urging them not to. Extremists and Islamophobes are trying to drown us out. Will we let them?

Mustafa Ait Idir, a computer science teacher in Sarajevo, was seized in Bosnia at the demand of the U.S. in October 2001, ordered released by two Bosnian courts, and illegally handed over to American forces who brought him to Guantánamo in January 2002. A U.S. judge ordered his release in 2008. Idir and Lakhdar Boumediene are co-authors of Witnesses of the Unseen: Seven Years in Guantánamo . They were co-plaintiffs in the 2008 Boumediene v. Bush case before the Supreme Court, which gave Guantánamo prisoners access to federal courts.