Andy Worthington's Blog, page 47

October 11, 2017

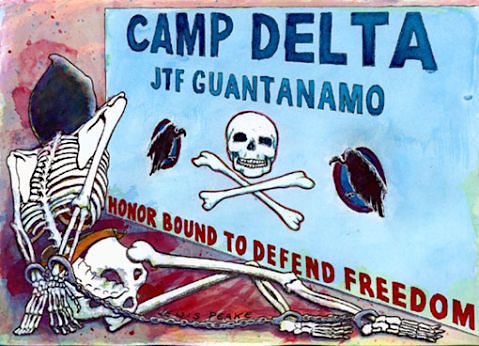

New York Times Finally Reports on Trump’s Policy of Letting Guantánamo Hunger Strikers Die; Rest of Mainstream Media Still Silent

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

So today, five days after the lawyer-led human rights organization Reprieve issued a press release, about how two of their clients had told them that, since September 20, prisoners on a long-term hunger strike were no longer being force-fed, and four days after I reported it (exclusively, as it turned out), the New York Times emerged as the first — and so far only — mainstream media outlet to cover the story, although even so its headline was easy to ignore: “Military Is Waiting Longer Before Force-Feeding Hunger Strikers, Detainees Say.”

As Charlie Savage described it, military officials at Guantánamo “recently hardened their approach to hunger-striking prisoners,” according to accounts given by prisoners to their lawyers, “and are allowing protesters to physically deteriorate beyond a point that previously prompted medical intervention to force-feed them.”

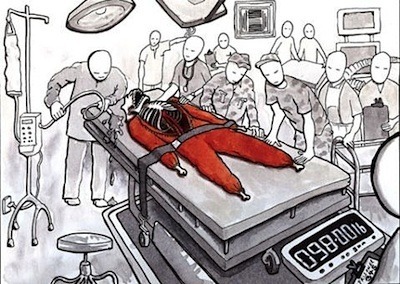

“For years,” Savage continued, “the military has forcibly fed chronic protesters when their weight dropped too much. Detainees who refuse to drink a nutritional supplement have been strapped into a restraint chair and had the supplement poured through their noses and into their stomachs via nasogastric tubes.”

But “around Sept. 19,” according to Clive Stafford Smith, Reprieve’s founder, “guards stopped taking hunger-striking detainees to feeding stations,” a change “reported by two Reprieve clients who had been subjected to tube feedings,” as explained in Reprieve’s original press release and in my article, “and corroborated by several other clients.”

Reprieve’s clients are Khalid Qassim (aka Qasim), a Yemeni, and Ahmed Rabbani, a Pakistani, and Charlie Savage was also told by David Remes that one of his clients, Abdul Salam al-Hela (aka al-Hilal), a Yemeni, had been on a hunger strike since August “but had not been tube-fed despite losing significant weight.” Al-Hela “also told him that other protesters were no longer being force-fed.”

One of those other prisoners is Sharqawi al-Hajj, another Yemeni, who I mentioned in my article on Friday based on reports made public about him last month, which I reported here. As his attorney, Pardiss Kebriaei of the Center for Constitutional Rights, told Charlie Savage, he “was hospitalized in July, though he eats a small amount of solid food each day to accompany pain medication.” On Sept. 21, he told Kebriaei that “a prison official told him a day earlier that he would not be forcibly tube-fed, either.”

All four of these men are amongst the 26 men (out of the remaining 41) who are not approved for release, but are not facing trials either. Between 2013 and 2016, they had their cases reviewed by Periodic Review Boards, a parole-type initiative of President Obama’s, but had their ongoing imprisonment upheld. The PRBs continue to assess their cases, but, in most it not all of them, it seems clear that the authorities have decided that they should continue to be held without charge or trial, because they are regarded, whether rightly or wrongly, as an ongoing security threat.

The lawyers who spoke to Charlie Savage also told him about a fifth prisoner, identified as a hunger striker by other prisoners, although he “does not have a lawyer,” and it is not known which category of prisoner he is. As well as the 26 men subjected to the PRBs, five of the men still held were approved for release but not freed before Obama left office, while ten are facing, or have faced trials.

In a statement, Navy Capt. John Robinson, a spokesman for the prison, said, as Savage described it, that “an 11-year-old military policy permitting the involuntary feeding of hunger-striking detainees remained in effect,” contradicting what the prisoners had told their lawyers.

Capt. Robinson explained, as the Times put it, that “[i]f medical officials decided tube-feeding was required to prevent death or serious self-harm,” the military would act accordingly. As he put it, “we would involuntarily enterally feed a detainee” — the military’s euphemism for force-feeding.

Capt. Robinson refused to discuss individual cases, but claimed that the military had not “involuntarily enterally fed a detainee in well over a year,” although it is, of course, impossible to ascertain whether or not this is true.

Savage pointed out that Capt. Robinson “would not elaborate on what it would mean to be voluntarily tube-fed,” but Pardiss Kebriaei “said it was most likely a reference to detainees who passively submitted to the procedure rather than fighting guards.”

A Pentagon spokesman, Maj. Ben Sakrisson, told the Times that “prison officials had decided to start to more rigorously enforce existing policy standards for what health conditions were sufficient to prompt force-feeding.” As he put it, “In some instances in the past, attempts to provide detainees who claimed that they were on hunger strike with a measure of dignity through voluntary enteral feedings unintentionally created a situation that potentially encouraged future hunger strikes. As a result, the pre-existing standard of medical necessity will be enforced in the future.”

Perhaps that makes sense to you, but to me it sounds like a deliberate attempt to bamboozle critics of the new policy that prisoners have been telling their lawyers about. As Charlie Savage described it, David Remes “interpreted the move as a new strategy to induce hunger strikers to stop,” and “accused the military of ‘playing chicken’ by withholding both force-feeding and medical care until the detainee was in danger of organ damage or even death.”

As he put it, “The theory is that a detainee won’t want to reach that point and so will abandon his hunger strike. Who will blink first?”

Who indeed? If a prisoner does refuse to give up a hunger strike, then surely the refusal to force-feed them or to offer them medical care risks them dying; and, in fact, makes that a possible or probable outcome.

Charlie Savage pointed out that the prisoners’ lawyers are in a difficult position, because many have argued in the past that “force-feeding amounts to torture and violates medical ethics” (all of which is true), but of course allowing men to die is difficult to accept. “For now,” as he put it, “the three lawyers said they are seeking independent medical evaluations of their clients,” although of course the prisoners themselves are on hunger strikes because they seek some sort of justice that is permanently denied to them.

As the Times put it, David Remes “said his client was protesting because he wanted the military to permit him to talk to his family twice a month rather than once,” Pardiss Kebriaei “said her client was in a general state of despair and might be suffering from an untreated illness,” and Clive Stafford Smith “said his clients were protesting because they wanted to be given trials or released.”

Their desire will come into even sharper relief if, as scheduled, military officials in the near future deliver a sentencing hearing for Ahmed al-Darbi, a Saudi prisoner who, in February 2014, accepted a plea deal in his military commission proceedings, in which, in exchange for testifying against other prisoners facing trials, he would be returned to Saudi Arabia next February to serve the remainder of his sentence.

As I explained two months ago, when he first began testifying as agreed, his plea deal shows the essential absurdity of Guantánamo, because, as the US government prepares to release him, it is also saying to less significant prisoners that they, on the other hand, will remain trapped at Guantánamo forever.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

October 9, 2017

What Should Trump Do With the US Citizen Seized in Syria and Held in Iraq as an “Enemy Combatant”?

It’s nearly a month since my curiosity was first piqued by an article in the Daily Beast by Betsy Woodruff and Spencer Ackerman, reporting that a US citizen fighting for ISIS had been captured in Syria and was now in US custody. Ackerman followed up on September 20, when “leading national security lawyers” told him that the case of the man, who was being held by the US military as an “enemy combatant,” after surrendering to US-allied Kurdish forces fighting ISIS in Syria around September 12, “could spark a far-reaching legal challenge that could have a catastrophic effect on the entire war against ISIS.”

At the time, neither the Defense Department nor the Justice Department would discuss what would happen to the unnamed individual, although, as Ackerman noted, “Should the Justice Department ultimately take custody of the American and charge him with a terrorism-related crime, further legal controversy is unlikely, at least beyond the specifics of his case.” However, if Donald Trump wanted to send him to Guantánamo (as he has claimed he wants to be able to do), that would be a different matter.

A Pentagon spokesman, Maj. Ben Sakrisson, told Ackerman that, according to George W. Bush’s executive order about “war on terror” detentions, issued on November 13, 2001, and authorizing the establishment of military commissions, “United States citizens are excluded from being tried by Military Commissions, but nothing in that document prohibits detaining US citizens who have been identified as unlawful enemy combatants.”

However, as Ackerman explained, “Keeping the unnamed American detained by the military — according to several attorneys with deep experience with post-9/11 detention-law questions — risks a showdown in court over the very foundations of the war against ISIS,” because the only legal basis for the US to be engaged militarily against ISIS is the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), passed by Congress just after the 9/11 attacks.

Using the AUMF to justify war with ISIS has always stretched the bounds of credulity, as Ackerman noted, describing how, “As the path of least political resistance, Barack Obama based the war against ISIS on the AUMF, despite ISIS not having existed on 9/11,” and also “treated ISIS’ high-profile split from al Qaeda in 2014 as a legally insignificant fact.”

Repeated efforts at passing a new AUMF to cover the war with ISIS came to nothing under President Obama, and Donald Trump’s administration has already “ruled out seeking ‘additional authorizations’ to replace or update the AUMF,” according to a letter the State Department sent to Congress in August.

As a result, the unnamed US captive is able to challenge the basis of his detention under habeas corpus, and, as attorneys told Ackerman, a US citizen can not only challenge the basis of their military detention in court, but doing so would “permit a judge to rule whether the AUMF applies to ISIS — and potentially invalidate it.”

On September 29, the ACLU sent a letter to Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and Attorney General Jeff Sessions “urging them to comply with the Constitution and ensure that the legal rights of the US citizen are respected,” but they received no reply. and so, on October 5, they filed a habeas corpus petition on his behalf in the US District Court for the District of Columbia, asking the court “to order the Pentagon to give the US citizen the opportunity to obtain legal assistance by putting him in secure contact with ACLU attorneys,” and also asking the court “to find that the military detention is unlawful and to rule that the only lawful basis to detain him is under properly filed federal criminal charges.”

As ACLU attorney Jonathan Hafetz explained, “Indefinite military detention without due process violates the most basic principles of our Constitution. The US government cannot imprison American citizens without charge or access to a judge. It also cannot keep secret the most basic facts about their detention, including who they are, where they are being held, and on what authority they are being detained. The Trump administration should not resurrect the failed and unlawful policy of ‘enemy combatant’ detentions.”

Following the submission of the habeas petition, the New York Times provided the most up-to-date information on the case. Eric Schmitt and Charlie Savage spoke to “an official familiar with internal deliberations” in the Trump administration, who “said the problem facing Pentagon and Justice Department officials is how to ensure that the man — who surrendered on Sept. 12 to a Syrian rebel militia, which turned him over to the American military — will stay imprisoned.”

The official — elsewhere described as a “senior administration official” — added that it “may not be possible to prosecute the man because most of the evidence against him is probably inadmissible,” but confirmed that “holding a citizen in long-term wartime detention as an enemy combatant — something the military has not done since the George W. Bush administration — would rekindle major legal problems left dormant since Mr. Bush left office and could put at risk the legal underpinnings for the fight against the Islamic State.”

The Times added that it was “unclear” whether the ACLU has standing to represent the prisoner without him “agreeing to let it represent him,” pointing out that, “Because Trump administration officials have refused to disclose his name, rights groups have been unable to track down any close relative to grant that assent on his behalf.”

The official who spoke to the Times provided some information about his background that was previously unknown, explaining that he “was born on American soil, making him a citizen, but his parents were visiting foreigners and he grew up in the Middle East,” and adding that the “near total lack of contact with the United States slowed efforts to verify his identity.”

Explaining the circumstances in which evidence was gathered against him, the official explained that he “was interrogated first for intelligence purposes — such as to determine whether he knew of any imminent terrorist attacks — without being read the Miranda warning that he had a right to remain silent and have a defense lawyer present.” The government “then started a new interrogation for law-enforcement purposes, but after the captive was warned of his Miranda rights, he refused to say any more and remains in military custody in Iraq.”

The source added that Investigators have identified a file “in a cache of seized Islamic State documents that appears to be about the captive,” but conceded that “prosecutors could have difficulty getting that record, which was gathered under battlefield conditions, admitted as evidence against him under more rigorous courtroom standards.”

As a result, the Times added, “while the Pentagon wants the Justice Department to take the prisoner off its hands, law enforcement officials have been reluctant to take custody of him unless and until more evidence is found to make it more likely that a prosecution would succeed.”

Steve Vladeck, a law professor at the University of Texas, who write about national security matter for the Just Security website, and recently wrote an article entitled, “The Increasingly Unsettling Indifference Toward the US Citizen ‘Enemy Combatant,’” told the Times that there was “a limit to how long the military can hold a citizen without at least letting him talk to lawyers.”

Vladeck said, “It would be one thing if this were a cooperating witness who was being kept in incommunicado detention to protect his safety and his intelligence value. But keeping someone in these circumstances simply because they don’t know what to do with him is not going to help them in court, if and when it gets there.”

In contrast, the Pentagon’s spokesman, Maj. Ben Sakrisson, claimed that “captured enemy fighters may be detained” as part of the armed conflict against the Islamic State, citing the 2004 Supreme Court ruling in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, against Yasser Hamdi, a US citizen captured in Afghanistan in December 2001.

As the Times explained, however, “there are questions that were not answered by that 2004 ruling and would be raised again by trying to hold the new detainee indefinitely.”

The article continued:

Mr. Hamdi, like the new captive, was born in the United States but raised abroad — in his case, Saudi Arabia. After he was captured in Afghanistan, the Bush administration moved him, along with hundreds of other wartime detainees, to the prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Only there did officials discover his citizenship.

They transferred him to a brig in South Carolina and continued to hold him as an enemy combatant under the laws of war. In 2004, the Supreme Court ruled that his detention as a wartime prisoner was lawful — but also that he had a right to challenge the evidence that he was an enemy fighter in a hearing before a neutral decision maker.

Instead of granting him such a hearing, the Bush administration sent him to Saudi Arabia. The Supreme Court has never ruled on what kind of hearing — or how much or what type of evidence — is sufficient to hold an American in indefinite wartime detention. Attempting to hold the new detainee in that fashion would raise those questions anew.

The Trump administration would also face political risks in holding an American as a long-term enemy combatant. The Bush administration’s decision to detain Mr. Hamdi without trial, along with an American [Jose Padilla] and a Saudi on a student visa [Ali al-Marri] who were arrested in Illinois and transferred to military custody, was controversial across the ideological spectrum.

That is something of an understatement, as I made clear in numerous articles from 2007 to 2009, challenging the imprisonment of US citizens and legal residents as “enemy combatants’ on the US mainland — and decrying the torture to which they were subjected.

See, from 2007, Jose Padilla: More Sinned Against Than Sinning and The torture of Ali al-Marri, the last “enemy combatant” on the US mainland, from 2008, Why Jose Padilla’s 17-year prison sentence should shock and disgust all Americans, Court Confirms President’s Dictatorial Powers in Case of US “Enemy Combatant” Ali al-Marri and The Last US Enemy Combatant: The Shocking Story of Ali al-Marri, and, from 2009, Ending The Cruel Isolation Of Ali al-Marri, The Last US “Enemy Combatant”, Why The US Under Obama Is Still A Dictatorship and Dictatorial Powers Unchallenged As US “Enemy Combatant” Pleads Guilty. For updates on Jose Padilla from 2011 and 2014, see: It Could Be You: The Sad Story of Jose Padilla, Tortured and Denied Justice and Shameful: US Judge Increases Prison Sentence of Tortured US Enemy Combatant Jose Padilla.

Concluding their article, Eric Schmitt and Charlie Savage noted that it was not yet clear whether the Trump administration is “also weighing transferring the captive to Iraqi or Kurdish custody,” noting that the Obama administration “sent a previous high-profile Islamic State prisoner, Umm Sayyaf, to Iraq,” although, perhaps crucially, she was not American.

The Times also made a point of asking whether the existing use of the 2001 AUMF to justify war with the Islamic State can survive a new legal challenge, although it is less than a year since a judge dismissed a lawsuit submitted by Capt. Nathan Michael Smith, who stated that, “while he supported fighting the Islamic State as a matter of policy, he believed that the current effort violated the Constitution and the War Powers Resolution, which limits combat operations to 60 days if Congress has not authorized the deployment.” Last November, Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly ruled that Capt. Smith “lacked the standing to bring the case,” as the New York Times described it, adding that Judge Kollar-Kotelly also said that “whether the war had been properly authorized was a question for the two elected branches of government, not a court, to decide.”

In her opinion, she wrote, “This case raises questions that are committed to the political branches of government. The court is not well equipped to resolve these questions, and the political branches who are so equipped do not appear to be in dispute as to their answers.”

The Times also pointed out that “legal experts have warned the Trump administration not to bring Islamic State detainees to Guantánamo” to avoid testing the ability to detain prisoners under the AUMF. As Steve Vladeck described it, “They don’t want this habeas case. This is not the hill the government wants to fight the ISIS or the US citizen questions on.”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

October 7, 2017

Trump’s Disturbing New Guantánamo Policy: Allowing Hunger Strikers to Starve to Death

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Disturbing news from Guantánamo, via the human rights organization Reprieve. Yesterday, in a press release, Reprieve explained that the authorities at Guantánamo have stopped force-feeding hunger-striking prisoners, a practice that ha existed for ten years, because of a new Trump administration policy.”

Hunger strikers have existed at Guantánamo almost since the prison opened, and in 2013 a prison-wide hunger strike drew worldwide condemnation for President Obama’s inaction in moving towards closing the prison, as he had promised on his second day in office. Inconvenienced by Republican lawmakers, who had raised considerable obstacles to the release of prisoners, Obama had chosen not to challenge the Republicans, and had, instead, done nothing. The hunger strike changed all that, but towards the end of 2013, after the release of prisoners resumed, the authorities at Guantánamo stopped reporting the numbers of men who were on a hunger strike.

According to Reprieve, since that time, some prisoners have continued with their hunger strikes, “peacefully protesting a lack of charges or a trial,” although very little has been heard about them, with just one example reported in recent years — that of Sharqawi al-Hajj, a Yemeni held without charge or trial at Guantánamo since September 2004, whose case I reported on last month, when he weighed just 104 pounds, and when, after he refused to submit to being force-fed, he “lost consciousness and required emergency hospitalization.”

Explaining the force-feeding policy at the prison, Reprieve stated that “[t]he ten-year practice had been to force feed them when they have lost one fifth of their body weight.” However, Reprieve were told that, on September 20, “a new Senior Medical Officer (SMO) stopped tube-feeding the strikers, and ended the standard practice of closely monitoring their declining health.”

The numbers remain classified, but Reprieve suggests that it includes six “low value” prisoners; in other words, six of the 26 men who are not facing trials (ten men are facing or have had trials) and who have not been approved for release (five others are in this category).

Reprieve also explained that one of the men on a hunger strike is Ahmed Rabbani, a Pakistani prisoner, who has been held — without charge or trial — since September 2002. He has been on a hunger strike since 2013, “reportedly weighs just 95 pounds, and is suffering internal bleeding.”

Another prisoner on a hunger strike is Khalid Qassim, also held without charge or trial since 2002, and also on a hunger strike since 2013. He has had no food whatsoever since September 20, and, two weeks later, has told his lawyers at Reprieve, “I can’t walk. My joints, my hips hurt me too much.” Reprieve explained that his blood sugar count has dropped to 55.

Khalid Qassim also stated, “Before the medical authorities at Guantánamo used to say we watch your health, meals or your weight, your health is important, if you’re in a bad condition, force feeding is required. After the 20th, they don’t say that.”

Reprieve also explained that the prisoners told them that “the new policy, which is combined with offering them trays of food, is designed to force them to end their strike.”

Ahmed Rabbani said, “I don’t want to die, but after four years of peaceful protest I am hardly going to stop because they tell me to. I will definitely stop when President Trump frees the prisoners who have been cleared, and allows everyone else a fair trial.”

In response to the news, Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, a lawyer with Reprieve who represents prisoners at Guantánamo, said, “This new Trump policy should not be implemented in secret. Not only will the detainees die as a result of their peaceful protest, but their deaths will spark still more anger if the military coerces them by manipulating their medical treatment. The Trump Administration must urgently allow independent medics to examine these detainees, before it’s too late.”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

October 5, 2017

Ten Years On, Guantánamo’s Former Chief Prosecutor on Why He Resigned Because of Torture, and How It Must Never Be US Policy Again

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Ten years ago, a significant gesture against the torture program introduced by the administration of George W. Bush took place when Air Force Col. Morris Davis, the chief prosecutor of the military commission trial system at Guantánamo Bay, resigned, after being placed in a chain of command below two men who approved the use of torture. Davis did not, and he refused to compromise his position — and on the 10th anniversary, he wrote an op-ed for the Los Angeles Times, reiterating his implacable opposition to torture, his incredulity that we are still discussing it ten years on, and his hopes for accountability, via the fact that, in August, torture architects James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen settled a lawsuit brought against them by three men tortured in CIA prisons, and also because, in the near future, “a citizen-led group, the North Carolina Commission of Inquiry on Torture, will hold a public hearing to take testimony from people who were involved in and affected by the interrogation program designed by Mitchell and Jessen.”

I’m cross-posting the op-ed below — but first, a little background.

I remember Col. Davis’s resignation, as it took place just a few months after I’d started writing about Guantánamo on an almost daily basis, and I knew it was a big deal, although I didn’t know the extent of it at the time. I did know, however, that he was not the first prosecutor to resign. Four resigned before him, including Marine Lt. Col. Stuart Couch, who was supposed to prosecute the Mauritanian Mohamedou Ould Slahi, but refused to because of the torture to which he had been subjected.

However, Davis was the first chief prosecutor to resign based on his objections to the system, and his objections went to the top of the government. His first objection was to Air Force Brig. Gen. Thomas W. Hartmann, a minor player in the Guantánamo story, who had been assigned as chief counsel to the official overseeing the military commissions in July 2007, but above him was a much bigger fish — William J. Haynes II, the general counsel of the Department of Defense; in other words, defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s number one lawyer.

Most people with any interest in America’s journey to the “dark side” after 9/11 know that the CIA was authorized to set up a global network of “black sites,” where prisoners were subjected to torture, but not everyone knows that torture was also specifically approved at Guantánamo, by Donald Rumsfeld, on the specific advice of Haynes.

As Jane Mayer revealed in an article for the New Yorker in 2006, “On December 2nd [2002], Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld gave formal approval for the use of ‘hooding,’ ‘exploitation of phobias,’ ‘stress positions,’ ‘deprivation of light and auditory stimuli,’ and other coercive tactics ordinarily forbidden by the Army Field Manual.” Haynes had approved the techniques in a memo five days before, and in a notorious hand-written note, Rumsfeld, who worked standing at a podium, scribbled on the memo with reference to prisoners being made to stand in stress positions, but for no more than four hours at a time, “I stand for 8-10 hours a day. Why is standing limited to 4 hours?”

After Davis’s resignation, he became an implacable critic of the system, writing a scathing op-ed for the Los Angles Times that December, and, in February 2008, he spoke to the Nation, and, as I explained at the time:

When asked by the Nation if he thought that the six men could receive a fair trial, he related a conversation with Haynes that had taken place in August 2005. According to Col. Davis, Haynes “said these trials will be the Nuremberg of our time ” — a reference to the 1945 trials of Nazi leaders, “considered the model of procedural rights in the prosecution of war crimes,” as the article described them. Col. Davis replied that he had noted that there had been some acquittals at Nuremberg, which had “lent great credibility to the proceedings.” “I said to him that if we come up short and there are some acquittals in our cases, it will at least validate the process,” Col. Davis remembered. “At which point, his eyes got wide and he said, ‘Wait a minute, we can’t have acquittals. If we’ve been holding these guys for so long, how can we explain letting them get off? We can’t have acquittals. We’ve got to have convictions.’”

Haynes then, suddenly, resigned, although he has never been held accountable for his important role in establishing the torture program, with which he was evidently involved from the earliest days. He went on to join the Chevron Corporation as its Chief Corporate Counsel, almost immediately after leaving the Pentagon, and, in June 2012, became General Counsel and Executive Vice President of SIGA Technologies, Inc., a New York-based pharmaceutical company.

After writing about and cross-posting Morris Davis’s writings about Guantánamo and torture, I finally met him when the attorney Tom Wilner and I (who set up the Close Guantánamo campaign in 2012) invited him to discuss Guantánamo at the New America Foundation (now New America) on the anniversary of the prison’s opening in 2011. He then joined us for subsequent events in 2012, 2013 and 2015.

Davis’s op-ed is cross-posted below, and I hope you have time to read it, and will share it if you find it useful.

Here’s why I resigned as the chief prosecutor at Guantánamo

By Morris Davis, Los Angeles Times, October 4, 2017

Ten years ago today, I informed Gordon England, then the Deputy Secretary of Defense, that I could no longer serve as chief prosecutor for the military commissions at Guantánamo Bay. I requested immediate reassignment to another post and, within an hour, my request was approved. Soon after, I received an order not to speak to anyone about why I quit.

Here’s why I quit. Earlier that day, I had been handed an order, signed by England, that reorganized the chain of command, effective immediately. The order had placed Air Force Brig. Gen. Thomas W. Hartmann above me, and it had placed William J. Haynes II, the general counsel of the Department of Defense, above Hartmann.

Haynes, you might recall, signed the infamous torture memo — the one authorizing enhanced interrogation at Guantánamo that was approved by former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. It was in the margin of Haynes’ memo that Rumsfeld scribbled a comment about a four-hour limit placed on the amount of time interrogators could force detainees to stand upright. If he himself stood eight to ten hours a day, Rumsfeld wrote, why was the limit only four hours?

Hartmann had arrived a few months before, in July 2007, to serve as chief counsel to the official overseeing the military commissions. He was anxious to get convictions and wanted me to use all evidence, regardless of how it was acquired. For two years, my policy had been that the prosecution would not use evidence obtained by torture, because evidence obtained by torture is tainted. By the end of his first month, Hartmann had already tried to challenge this well-established fact.

When I learned that two men who sanctioned torture were above me in the chain of command, I concluded that I could not ensure fair trials for the detainees at Guantánamo. Nor could I put my head down and ignore the fact that the United States employed a practice it had long condemned.

I wish I could say that, in the following decade, the U.S. recovered from the shock of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, recognized the errors it made and regained its legal and moral standing on the issue of torture. That would be fake news.

I thought the election of Barack Obama, one year after I resigned, signaled the beginning of a new chapter in which America would atone for having veered off course. It was soon clear that my optimism was misplaced. After he was elected but before he was inaugurated, President Obama said of the torture program that the U.S would “need to look forward as opposed to looking backwards.” It was obvious that no one involved in sanctioning torture would be held accountable.

Obama’s decision may have been pragmatic in the short term, given the severe economic crisis he inherited. In the long term, history will remember it as a mistake. The government officials who had sanctioned torture enjoyed eight years of impunity during the Obama administration. This set the stage for Donald Trump to claim during the 2016 campaign that “torture works,” and that if he were president, he would bring back “a hell of a lot worse than waterboarding.”

Trump’s pro-torture rhetoric has so far gone unfulfilled, thankfully. But the issue should not even be open for discussion anymore. We have Obama’s inaction to thank for this.

There has been some recent progress, however. In August, the architects of the enhanced interrogation program, the psychologists James Mitchell and John “Bruce” Jessen, settled a lawsuit brought against them by the American Civil Liberties Union on behalf of three former detainees who said they were tortured at CIA prisons overseas, including one who died in custody. Every previous case in which former prisoners attempted to hold the U.S. government accountable for its torture program — including cases brought against government officials, employees and contractors — was dismissed.

Another step is an initiative in my home state of North Carolina. Later this fall, a citizen-led group, the North Carolina Commission of Inquiry on Torture, will hold a public hearing to take testimony from people who were involved in and affected by the interrogation program designed by Mitchell and Jessen. At this hearing, the group will also examine North Carolina’s role in facilitating torture by allowing its airports to be used for “torture taxi” flights, in which suspected terrorists were picked up abroad and transported to CIA black sites.

When I resigned a decade ago, I assumed that the U.S. would have closed the book on torture by now. I am disappointed that the issue remains unsettled, but heartened that there are groups seeking accountability. Injustices must not be forgotten. I intend to do my part to make sure Americans remember: Torture was wrong then, and it is wrong now.

Col. Morris Davis served as the chief prosecutor of the Guantanamo military commissions from September 2005 to October 2007. He was represented by the ACLU in a 2010 lawsuit against the Library of Congress.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

October 4, 2017

My Thoughts on Gun Control, Based on a Comparative Analysis of the US and the UK

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist and commentator.

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist and commentator.

Following the latest gun-based terrorist atrocity in US (the Las Vegas Strip Massacre, in which a 64-year old white man shot dead 59 people and wounded more than 500), here are my thoughts on gun control, based on a comparative analysis of the differences between the US and the UK.

First of all, let me explain that, in London, where I live, I can’t, off the top of my head, think of where to find a single gun shop. In contrast, I think it’s fair to say, guns are readily available in the US.

As CNN explains, “Hundreds of stores sell guns, from big chains like Walmart to family-run shops.” Background checks are conducted in store purchases,” where gun buyers have to fill out a form from the ATF (the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives). However,required information only includes the buyer’s name, address, place of birth, race and citizenship. The store then runs a background check with the FBI, but this is a process that can only take a few minutes. There’s also a loophole to avoid any kind of background check — buying a gun at one of America’s many gun shows, where there are no checks.

In contrast, this is what you have to do to get a gun in the UK (the information is from the UK government):

You need a firearms certificate issued by the police to possess, buy or acquire a firearm or shotgun. You must also have a certificate to buy ammunition. You can get a firearm or shotgun certificate application form from the firearms licensing unit of your local police force.

You must: complete an application form; provide 4 passport photographs; have 2 referees for a firearm certificate and 1 referee for shotgun certificate; pay the fee for the certificate you are applying for.

You must also prove to the chief officer of police that you’re allowed to have a firearms certificate and pose no danger to public safety or to the peace.

A shotgun certificate won’t be given or renewed if the chief officer of police has a reason that you shouldn’t be allowed to have a shotgun under the Firearms Act. Or if they don’t think you have a good reason to have, buy or acquire a shotgun.

So now here are some statistics.

There was a total of 571 homicides (murder, manslaughter and infanticide) in the year ending March 2016 in England and Wales.

26 of those homicide victims (5% of the total) were killed by shooting.

In contrast, in the US, in 2015, there were 13,500 deaths by shooting.

The US has a population five times larger than the UK, so if the US had Britain’s gun laws, it is reasonable to assume that the death toll from guns would drop from 13,500 a year to around 130.

Or, to put it another way, if the UK had America’s gun culture, instead of 26 people being killed every year by guns, the number would be 2,700.

In other words, 100 times more people are killed by guns in the US than in the UK.

The US has around 300 million guns, whereas the UK has 1.8 million.

If the UK followed the US’s example, there would be 60 million guns in the UK.

If the US followed the UK’s example, there would be just nine million guns in the US.

And if there were just nine million guns in the US, instead of 300 million, I think it’s fair to suggest that there would be a phenomenal reduction in the number of gun deaths.

Defenders of America’s gun culture like to claim that “guns don’t kill people: people kill people,” but the evidence demonstrates that, in fact, while people do of course kill people, the overwhelming conclusion that has to be drawn from a dispassionate analysis of the facts is that it is predominantly people with guns who kill people.

Try gun control now, and see what happens.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

October 3, 2017

Life After Guantánamo: The Story of Mourad Benchellali, Freed 13 Years Ago But Still Stigmatized

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Three weeks ago, around the 16th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, there was a sudden flurry of media interest in Guantánamo, which was reassuring amidst the general indifference about the prison since Donald Trump became president. Most of the articles published focused on the alleged perpetrators of the attacks, and the inability of the military commission trial system to deliver justice because of its own inadequacies, and because the men allegedly responsible were all tortured for years in secret prisons run by the CIA, which I covered at the time, while others looked at former prisoners’ stories.

Four days after the anniversary, for example, the New York Times published a moving article by Mansoor Adayfi, resettled in Serbia last year, which I cross-posted here with my own commentary, while Al-Jazeera profiled Mourad Benchellali, a French national who was released in 2004, and has since become known for his efforts to prevent the radicalization of impressionable young people.

I’ve known about Benchellali’s story since I first began researching Guantánamo 12 years ago, in the fall of 2015, because the stories of most of the European nationals freed from the prison were well-reported — and contributed enormously to people’s general understanding of how malignant a project Guantánamo really is.

Benchellali came from a family concerned with Muslims’ struggles against oppression — particularly, it seems, in Chechnya — and went to Afghanistan, as a 19-year old, as an adventure, and, he hoped, as a way of raising his status against that of his elder brother. This is how I described his story in my book The Guantánamo Files, published in 2007, and I have no reason, ten years on, to dispute any of it. As I explained:

His father was a radical imam who had tried (and failed) to fight in Bosnia, his brother Menad had tried (and failed) to fight in Chechnya, and his brother, his father and even his mother had all spent time in French prisons, but he insisted that he went to Afghanistan for “an adventure” and as a way of enhancing his status, hoping that he would be “viewed differently” in his neighbourhood, and that his reputation might “match” that of his brother. He admitted that his sense of adventure was “misguided and mistimed,” and blamed his brother for encouraging him to go, and for arranging for him to attend a training camp. “For two months, I was there,” he wrote after his release, “trapped in the middle of the desert by fear and my own stupidity.”

When I profiled Benchellali in 2011, as part of a major analysis of the prisoners’ stories following the release of formerly classified military files by WikiLeaks, I also drew on an article in Le Figaro, from 2006, in which Benchellali made some statements about the abuse of prisoners in Afghanistan that seem to pre-figure what happened at Abu Ghraib in Iraq in 2003. Benchellali stated:

[In Kandahar] they hit us. They piled us one on top of the other. Sometimes, they took photos of us completely naked. We were interrogated several times a day. They handcuffed us to hurt us. I was tied to a bar placed above my head or then they tied me up very low on my back. Americans peed on detainees. I saw the Red Cross, but its representatives told me that there was nothing they could do.

He also spoke about the abuse prisoners suffered in Guantánamo, confirming what many other prisoners have said — that prisoners who were deemed to be uncooperative (in other words, those who refused to incriminate themselves and others, regardless of whether or not that information bore any resemblance to the truth) were subjected to particular bad treatment, including prolonged sleep deprivation (with some men moved every hour over days, weeks and even months) and torture through the use of loud music and white noise. The drive for confessions (whether reliable or not) is well-known to those who have studied Guantánamo closely, but I believe it is still unknown as a general rule.

Benchellali stated:

Then, in January 2002, I was transferred to Guantánamo. I was beaten up on the bus that was taking us to the camp. We were treated differently depending on whether or not we responded to questions. Those who did not “cooperate” were awakened every hour with the aim of preventing them from sleeping at all costs. They might put us in a room with the music very loud broadcast through large speakers or make us endure flashes of light for several hours at a time. Sometimes, they left us handcuffed for hours to a chair or then they turned down the air conditioning. The humiliations were numerous, in particular of a sexual nature. The Americans had prostitutes come into the camp. One of them planted herself in front of a Saudi — they were in the majority at Guantánamo — and smeared her menstrual blood on his face. The searches were constant and humiliating. They tied the Koran above us and took pleasure in batting it around.

In the six years since I profiled Benchellali, I have continued to take an interest in his case. He is active on social media, and, in 2015, he supported the ultimately successful campaign to secure the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison. It was also in 2015 that he was publicly humiliated by the Canadian government, which, on his arrival at Toronto’s airport, refused to allow him to visit on a planned — and already approved — trip to discuss his experiences and his work since his release.

The Al-Jazeera article, by Allison Griner, a freelance foreign correspondent from Florida, covers much of the above, and much more besides, further humanizing Benchellali by explaining how everything he does is for his ten-year old son — “the most beautiful gift that I could ever have gotten,” as he describes him. As he also says, “My prevention work, the youth outreach, all that — it’s for him. I want to make this Guantánamo experience into something positive, so he won’t be ashamed of it later on.”

I hope you have time to read the article, and will share it if you find it useful.

An ex-Guantánamo detainee rebuilds his life in France

By Allison Griner, Al-Jazeera, September 11, 2017

Thirteen years after Mourad left Guantánamo and returned to his native France, a shadow of suspicion still follows him.

Lyon, France: For days, the rain had battered the sides of the prison, pattering incessantly on its sheet metal walls. A hurricane was on its way — that much Mourad Benchellali had gathered. But no one had come to get him, and from what he could tell, it seemed unlikely that he or any of his fellow prisoners would be moved.

Staring out from a steel-mesh door, Benchellali struggled to contain his frustration. The number of guards he counted patrolling his cellblock had grown fewer and fewer, and those who remained were wearing survival gear. He remembers hearing rumours that the sea might rise and crash into the prison, as the storm tore closer.

One of the guards left on duty was someone he ordinarily enjoyed talking to: a religious man, well-versed in the Bible. Benchellali himself was the son of an imam, and usually, he appreciated the guard’s gentle presence, his willingness to stop and chat.

But this time, things were different. Benchellali was tense. He didn’t know if the hurricane would strike, or if it would swerve into another part of the Caribbean. Precious little information reached him from the outside world, isolated as he was in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

“How is it that your lives are important, and ours aren’t?” he remembers calling out to the guard. “Us, we can drown. It’s not a big deal. But you guys? You save your skin.”

The guard, he recalls, replied with his usual fervour: “Don’t worry. God is with you.” The situation, the guard told him, reminded him of Noah, the man chosen by God to survive a world-levelling flood in both Christian and Islamic faiths. “With you, it’s the same. You detainees shouldn’t worry. Even if it rains, even if the water bursts its banks, you will be saved in the end.”

It wasn’t often that Benchellali felt treated like someone worth saving. After all, Guantánamo detainees were supposed to be “the worst of the worst”, a condemnation repeated by several Bush administration officials during the post-9/11 “war on terror”.

Even now, a shadow of suspicion follows Benchellali wherever he goes. Thirteen years have passed since he boarded a plane out of Guantánamo, back to his native France. But the stigma has never faded.

A recurring dream in Guantanamo

Sitting in a train station cafe on a rainy Saturday in Lyon, 36-year-old Benchellali wears the straight face of a man who isn’t prone to outbursts of sentimentality. And yet, looking back, he admits the guard’s words touched him — so much so that years later, “Noah” sprang to mind when it came time to name his only child, a son.

“He’s the most beautiful gift that I could ever have gotten,” Benchellali says, staring into his empty cappuccino cup. He credits his son for giving him the motivation to talk about his past, although sometimes, he gets fed up with being prodded about his story after all these years.

“It tires me out,” Benchellali says in French. He has tried to move on, building a life for himself teaching others how to lay tiles. “I often remind the people I encounter that I’m not just an ex-Guantánamo detainee.”

His dark hair slicked back with gel and his broad shoulders hidden under a brown leather coat, Benchellali looks strikingly unremarkable — just another commuter hunkering down in the cafe, waiting for the storm to end.

All the same, he keeps his eyes low. As he prepares to launch into his story once more, his fingers nervously start to rip and twist the empty sugar packets from his coffee into tiny, feathery ropes. Words like “al-Qaeda” and “bin Laden” invariably earn him glances from surrounding tables.

Benchellali didn’t expect to have the life he has now. During the nights he spent in Guantánamo, he says he kept having the same dream: of a little boy, someone he instinctively recognised as the son he’d have one day. But his fellow inmates tried to let him down gently, warning him not to get too attached to the idea. It was just a dream after all. Guantánamo was their reality.

Prisoner 161: held without charges

When Benchellali first set foot in the Guantánamo Bay detention centre on January 17, 2002, he didn’t know if he would ever leave again. No one told him how long he would stay, or what he was charged with. He didn’t even know he was in Cuba when he arrived.

From that point on, Benchellali was known by the internment serial number 161, a mark of his status as a resident “enemy combatant” — a term used to designate people involved in hostilities against the United States and its allies. Pentagon documents from 2004 identify him as a “member of [al-Qaeda]” with a “commitment to Jihad” and “ties to other global terrorist networks”.

Those are allegations that Benchellali has long denied. He insists he’s not a dangerous man — just a young guy whose naivete led him into trouble. “It’s difficult to explain,” he says. “I knew appearances played against me.”

Like many of Guantánamo’s early detainees, Benchellali never had the chance to present his case at trial. He was a “terrorism” suspect with no means of arguing his innocence — or admitting to his mistakes.

“I never said I did nothing wrong. I’ve always said, ‘Yes, it wasn’t a good idea to go to Afghanistan. Yes, I found myself in an [al-Qaeda] training camp’. But what I don’t accept is that they called me a terrorist. That’s not true.”

Although Guantánamo’s detainees have been denounced as “battle-hardened terrorists”, few were ever charged, much less convicted. One high-ranking State Department official went so far as to describe many of the detainees as “victims” of incompetent vetting, imprisoned without solid evidence against them.

“There was no meaningful way to determine whether they were terrorists, Taliban or simply innocent civilians picked up on a very confused battlefield,” the official, Lawrence Wilkerson [the former chief of staff to Secretary of State Colin Powell], said in testimony delivered to the US District Court for the District of Columbia.

The 2011 release of confidential Guantánamo documents, orchestrated by the anti-secrecy group WikiLeaks, revealed prisoners from a range of backgrounds. These included an Al Jazeera cameraman, a taxi driver, and even an 89-year-old Afghan man with symptoms of senile dementia, some of whom were explicitly assessed as “not affiliated with [al-Qaeda] nor as being a Taliban leader”.

Benchellali’s file is not so straightforward. It indicates that prisoner 161 had family ties to “terrorism”; that he admitted to being in an al-Qaeda training camp; and that officials considered him a “high risk” to the US and its allies.

Travelling to Afghanistan at 19

By his own account, Benchellali was a small, skinny 19-year-old when he decided to leave for Afghanistan with a friend. He says his older brother Menad encouraged them to go, saying it would be a great opportunity to learn about Islam.

Benchellali knew Afghanistan was a dangerous country, with warring factions and a steady arms trade. That was kind of the point. Back home in Venissieux, Benchellali considered himself a weakling — and in his rough-and-tumble neighbourhood, it was strength that counted. He saw visiting Afghanistan as a chance to prove himself, once and for all.

So when his brother offered to set them up with fake travel documents and arrange their travel, Benchellali says he ignored his misgivings and accepted. He trusted his brother, and he saw the whole process as an adventure.

Benchellali and his friend first stopped in London for the travel documents, then made their way to Afghanistan, where his brother’s friends awaited them. He says he thought he was going to scale mountains and explore the country. Fighting was the last thing on his mind.

“It wasn’t about jihad. When I left for Afghanistan, I wasn’t angry. I didn’t have any hate,” he says.

But one day, after arriving in Afghanistan, Benchellali and his friend fell into a trap. Their hosts, fellow French speakers, offered to take them on a trip to meet other young Muslims. Instead, Benchellali and his friend found themselves being dropped off at an isolated al-Qaeda training camp. There, Benchellali would come face-to-face with one of the group’s leaders: a tall, bearded man he learned was Osama bin Laden.

Surrounded by desert in an unfamiliar land, Benchellali felt stuck. The camp’s al-Qaeda leaders refused to grant him permission to leave — not until he had finished two months’ worth of military training. It was the summer of 2001. By the time he left, the world would be a different place.

After September 11

The September 11 attacks had triggered a global “war on terror”, and Afghanistan quickly became the subject of a massive bombing campaign. US forces also led a dragnet operation to arrest “terrorism” suspects on the ground — a campaign that allegedly offered bounties in exchange for prisoners.

In the tumult, Benchellali joined a group of men fleeing across the Pakistan border. When they stopped to have tea at a mosque, they ended up being locked inside and taken into custody.

A Department of Defense report — one of 779 files that WikiLeaks obtained and published — offers no specifics as to why Benchellali was transferred from there to Guantanamo, other than that he “possesses intelligence information”.

Ultimately, Benchellali said he wasn’t surprised that US forces detained him in Pakistan. “That they arrested me, I found that normal. I mean, they have the right to ask me about where I went and why I was there. What’s not normal is to send us to Cuba. What’s not normal is to remove all our rights.”

He was 20 years old by the time he arrived in Guantánamo, in January 2002. For the two and a half years, he spent there, Benchellali claims he was subject to insults, isolation and torture, including physical blows, sleep deprivation and sexual violence. All the while, life back home in France moved on without him.

By the time he flew back, the girlfriend he had left behind as a teenager had become someone else’s wife. The family he grew up with would be scattered and broken.

But Benchellali didn’t know all that when he boarded a plane out of Guantánamo in July 2004. He imagined his nightmare was over — that he would step onto the tarmac and into his parents’ arms. It was only later that he discovered his family would never be whole again.

His brother Menad — the same brother who arranged for him to go to Afghanistan — had been arrested for manufacturing deadly toxins in the family apartment, as part of an alleged plot to attack Russian targets in France on behalf of Chechen separatists.

Several relatives had been detained in connection to Menad’s activities, including Benchellali’s mother, a fact that left him devastated: “It was the worst period of my life,” he says.

Not only was his family in turmoil, but his individual ordeal was far from over too. Benchellali still faced “terrorism” charges in France, and he was sent to the same facility that housed his mother, the Fleury-Merogis prison. As his case, and eventual conviction, drew the media’s attention, he started to receive letters of support — including one from the woman who’d eventually become the mother of his child.

But some of the letters, however well intentioned, put Benchellali ill at ease. He got the feeling that, even among his supporters, he was perceived as a “jihadist”, he says. That suspicion lingered even after a Paris appeals court overturned his “terrorism” conviction.

Becoming an activist

Benchellali wrote a book about his experiences and reinvented himself as an “anti-radicalisation” activist, with the aim of educating others about groups like al-Qaeda. He hopes that, by sharing his story, he can prevent others from falling into the same trap he once did. His message is particularly aimed at youth.

“I tell them, ‘Me, I’m going to tell my story. Afterwards, do with it what you like.’ That’s to say, I’m not going to give you lessons, and I’m not there to say what’s good or bad,” Benchellali explains. “But after that, you can’t say you didn’t know.”

Over the years, Benchellali has been invited to tell his story to school groups, community centres and law enforcement officials as far away as Australia.

But every once in a while, even today, an invitation gets revoked. Benchellali suspects fear is the driving factor — fear that he might be a recidivist in disguise.

“Maybe he’s pretending. Maybe he’s playing a role — I know people think that,” Benchellali says. “I understand that they’re afraid. But I think they’re wrong.”

Political value of recidivism data

Benchellali maintains that he never converted to al-Qaeda’s ideology, nor participated in any violence. But of the 714 detainees transferred out of Guantánamo, 121 have, according to a January report by the US Director of National Intelligence, been confirmed as re-engaging “in terrorist or insurgent activities”. An additional 87 detainees are suspected of re-engaging.

But those numbers are misleading, says lawyer Mark Denbeaux, director of the Seton Hall Law School Center for Policy and Research. He is one of the most vocal critics of the bi-yearly report, which tracks recidivism among former detainees.

Denbeaux points out that no evidence is offered to indicate who is reengaging in “terrorist” activities, and in what way. His research has uncovered inconsistencies in past reports — including instances where criticising the US government was counted as a “return to the fight”.

Though Denbeaux dismisses the recidivism reports as fundamentally flawed, he admits the data “has political value in order to try and legitimise torture in Guantánamo”. He sees the reports as an attempt to skew the public’s perception. “Right now, the fight going on is: What should the narrative be for Guantánamo?”

The fight for Guantánamo’s legacy hits close to home for Benchellali. He personally has noticed a shift in how the French public perceives Guantánamo. “Today in France, there are people who call for a French version of Guantánamo,” he says. “That wasn’t the case five, 10 years ago.”

He also worries about US President Donald Trump’s campaign promise to continue using Guantánamo as a prison and “load it up with some bad dudes”.

Trump and Guantánamo’s resurgence in popularity

Currently, Guantánamo’s detainee population has dwindled to 41, but the Trump administration is considering plans to keep Guantánamo open indefinitely. Under one proposal, its cells would be filled with suspects with alleged ties to the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS). Benchellali fears the move would usher in a renewed era of public acceptance for Guantánamo and its abuses.

“We have rehabituated Americans to the fact that Guantánamo is a good thing,” he says. “The Americans are the biggest power in the world. It’s the model that everyone watches. So if the US tortures, it’s over — everyone will torture.”

Laurel Fletcher, the director of the International Human Rights Law Clinic at the University of California, Berkeley, believes that calls to close or reduce the prison population at Guantánamo were strongest in the late 2000s, in a brief period of “hiatus between episodes of active, violent extremism”.

At the time, the Bush administration had started to reduce the detainee population, and future President Barack Obama was campaigning on a promise to close Guantánamo.

But public anxiety has grown since then. Fletcher points to recent attacks, like the one in Barcelona this past August, as contributing to “a backdrop of perceived terrorist threat”.

“When you have those incidents that are regularly cropping up, I think it activates people’s fear,” Fletcher says. She believes it’s a normal “visceral response” to support strong action in the wake of “terrorist attacks” — and that’s why Guantánamo may be experiencing a resurgence in popularity, despite evidence that its methods fail to make the public safer, she says.

Telling his story to young people

In the classrooms and community centres where he does his outreach work, Benchellali has increasingly heard a startling equivocation from the young people he speaks with. They tell him, more and more, that everyone — from the US to ISIL to Bashar al-Assad — is guilty of “terrorism”. For them, it is simply a tool.

“It’s a real problem when you explain to young people that violence doesn’t change things, and they say, ‘No, it’s the only thing that can cause change’,” he says. He prefers not argue with them. Instead, his strategy is to stick to telling his story, in the hope that his experience can serve as a warning.

But the increasing polarisation has made his task more difficult. When he visited Molenbeek, a Brussels neighbourhood that Western media sometimes calls the “jihadi capital of Europe,” one young student walked out in the middle of his presentation. His friends later told Benchellali that he was a bin Laden supporter who disapproved of Benchellali’s story.

On other occasions, it’s the teachers he meets who don’t want to listen. Benchellali says some of them are convinced that their students’ embrace of Islam is actually a descent into violence and perceived “extremism”.

It’s a frustrating topic to navigate, and Benchellali says he often considers quitting his outreach efforts altogether. In this age of increased tension, he feels discouraged, not least by the treatment he receives in his own country.

Still a ‘suspect’ in his own country

As a former “terrorism” suspect, Benchellali also has to deal with France’s “FIJAIT” system, which requires him to regularly update the government about his whereabouts. Each time his work takes him across an international border — to Switzerland or Belgium, for example — he has to check in with French authorities 15 days beforehand.