Andy Worthington's Blog, page 16

March 9, 2020

Please Support My Quarterly Fundraiser: Seeking $2500 (£2000) For My Guantánamo Work and London Photography

Andy Worthington on RT in January 2020, and recent images from his ongoing photo-journalism project ‘The State of London.’

Andy Worthington on RT in January 2020, and recent images from his ongoing photo-journalism project ‘The State of London.’Please click on the ‘Donate’ button below to make a donation towards the $2,500 (£2,000) I’m trying to raise to support my work on Guantánamo over the next three months of the Trump administration, and/or for my London photo-journalism project “The State of London”.

Dear friends and supporters,

As many of you know, for the last 14 years I have been an independent journalist and activist, writing about Guantánamo and the men held there, and campaigning to get the prison closed. I have no institutional backing, and I’m therefore reliant on your support and generosity to enable me to keep doing this important work.

Guantánamo has been the main focus of my working life for the last 14 years, and it remains as true now, as it has been throughout my long dedication to the cause of getting Guantánamo closed, that I can’t do what I do without your support.

To preserve my health — both physically and mentally — I have also spent the last eight years cycling around London on a daily basis, taking photos of the changing face of the capital, for a project that I call ‘The State of London’, which involves me posting a photo — and an accompanying essay — every day on Facebook.

If you can make a donation to support my ongoing efforts to close Guantánamo, and/or ‘The State of London,’ please click on the “Donate” button above to make a payment via PayPal. Any amount will be gratefully received — whether it’s $500, $100, $25 or even $10 — or the equivalent in any other currency.

You can also make a recurring payment on a monthly basis by ticking the box marked, “Make this a monthly donation,” and filling in the amount you wish to donate every month, and, if you are able to do so, it would be very much appreciated.

The donation page is set to dollars, because the majority of those interested in my Guantánamo work are based in the US, but PayPal will convert any amount you wish to pay from any other currency — and you don’t have to have a PayPal account to make a donation.

Readers can pay via PayPal from anywhere in the world, but if you’re in the UK and want to help without using PayPal, you can send me a cheque (to 164A Tressillian Road, London SE4 1XY), and if you’re not a PayPal user and want to send cash from anywhere else in the world, that’s also an option. Please note, however, that foreign checks are no longer accepted at UK banks — only electronic transfers. Do, however, contact me if you’d like to support me by paying directly into my account.

While I don’t anticipate anything stopping me from continuing to cycle around London taking photos — except for the kerb that threw me off my bike at the end of January, which left me housebound for several weeks — on Guantánamo I feel the need to make explicit what I’m sure many of you will, by now, have realized: that I won’t stop writing about Guantánamo, and campaigning to get the prison closed, until it is shut once and for all.

I can only hope that I live long enough to see the day when Guantánamo is closed for good. I recently turned 57, and was a youthful 43 when I began working on Guantánamo full-time back in 2006, but although there has been progress in that time — the release of over 500 men by the time George W. Bush left office, and nearly 200 under Barack Obama — the worst thing that could possibly have happened, three years and four months ago, was for Donald Trump to have been elected president. Trump has, quite literally, sealed Guantánamo shut since taking office, releasing only one man because he was obliged to do so, and showing no intention of releasing any of the 40 other prisoners under any circumstances, even though only nine of them are facing or have faced trials, and five of them were unanimously approved for release, between 2009 and 2016, by high-level government review processes under Obama. The 26 others, who Trump is happily holding forever without charge or trial, were helpfully described many years ago as the “forever prisoners,” although by now that is a label that can genuinely be regarded as applying to all the men still held.

For the men still held, all hope is draining out of their lives, in a pointless and cruel facility in which they are getting older, and suffering from health problems related to ageing — or, in some cases, related to their torture and abuse — while the world appears largely to have forgotten them. Via my annual visits in January, marking the anniversary of the prison’s opening, I try to keep the story of the prison alive (as in my interview with RT this January), and I am also committed to doing all I can to get the prisoners’ own stories out to the world — via publicizing an important and ongoing exhibition of prisoners’ artwork at CUNY School of Law (see here and here), and also, most recently, by publishing, with my own introduction, a powerful and moving profile of one of the artists — the “forever prisoner” Khalid Qasim — by his friend, the former prisoner Mansoor Adayfi, who was resettled in Serbia in 2016, and has become an accomplished writer.

I hope you can make a donation to support my ongoing work — but even if you can’t, please be assured that taking an interest in it is what truly brings it to life!

And if you’re interested in any other manifestations of my creativity and activism, my books Stonehenge: Celebration & Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield are still available to order from me, my music with my band The Four Fathers is on Bandcamp, and for my other interest — housing activism — you can watch ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, the documentary I narrated about the housing crisis, here. In addition, my book The Guantánamo Files might also still be available, and, for a small fee, you can watch “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo,” the documentary I co-directed, here.

Andy Worthington

London

March 9, 2020

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign.

March 8, 2020

“My Best Friend and Brother”: A Profile of Guantánamo Prisoner Khalid Qasim by Mansoor Adayfi

Khalid Qasim (left), who is still held at Guantánamo, and his friend Mansoor Adayfi, released in 2016, and resettled in Serbia, who has written a powerful and moving profile of him, published below.

Khalid Qasim (left), who is still held at Guantánamo, and his friend Mansoor Adayfi, released in 2016, and resettled in Serbia, who has written a powerful and moving profile of him, published below.Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

Today we’re delighted to be publishing a brand-new article by former Guantánamo prisoner Mansoor Adayfi, about his friend Khalid Qasim, who is one of the 40 men still held in the prison at Guantánamo Bay in its latest iteration under Donald Trump — a place without hope, cruelly and pointlessly still in existence 18 years after it first opened.

To try and shine a light on the continuing injustice of Guantánamo — and the plight of the men still held — we were delighted, two weeks ago, to publicize an exhibition of prisoners’ artwork taking place at CUNY School of Law in New York, in an article entitled, Humanizing the Silenced and Maligned: Guantánamo Prisoner Art at CUNY Law School in New York. The exhibition was formally launched on February 19, and I wrote about its launch here, but my initial article focused on the work of just one prisoner, whose work had ben shown before the official launch, during my annual visit to the US in January, to call for the closure of the prison on the anniversary of its opening.

The prisoner is Khalid Qasim (also identified as Khaled Qassim), and as I was writing my article I noticed that Mansoor Adayfi had posted a message on Facebook stating, “My best friend and brother Khalid Qassim, 18 years behind bars at Guantánamo, without any charges or trial. What is enough for Trump?”

I had followed Mansoor’s story at Guantánamo, up to and including his review, in September 2015, via a parole-type review process, the Periodic Review Boards, which approved his release, followed by his resettlement, in July 2016, in Serbia, which had been prevailed upon to offer new homes to prisoners who could not be safely repatriated, or, as in Mansoor’s case, whose home country, Yemen, was regarded as unsafe.

In 2017, I was wonderfully surprised when Mansoor, who had learned English in Guantánamo, wrote a powerful and moving article, “In Our Prison on the Sea,” about life in Guantánamo, which was published in the New York Times, and was subsequently used as the introduction to the very first exhibition of Guantánamo prisoners’ art, “Ode to the Sea: Art from Guantánamo Bay,” at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, which ran from October 2017 to January 2018, and included some of Khalid’s art.

Mansoor and I subsequently began communicating, and in September 2018, after he had written a Facebook post describing Saifullah Paracha, Guantánamo’s oldest prisoner, as “a father, brother, friend, and teacher to us all,” I wrote to him to ask if he would be interested in writing more about Saifullah for “Close Guantánamo” — and was delighted when he said yes. That article, “The Kind Father, Brother, and Friend for All at Guantánamo,” was published in October 2018, and it was a great honor for us to be able to publish it.

And so, after I saw Mansoor’s recent post about Khalid Qasim, a fellow Yemeni, I asked him if he had any comments to make about Khalid for my article, and was surprised and delighted when, a day later, he sent an entire article, which is posted below, and which I have edited only slightly. Mansoor’s article clearly explains his friendship with and admiration for Khalid, as well as revealing the extent of his talents, his compassion, his leadership abilities, and the respect he is held in by prisoners and prison staff alike.

Unfortunately, while having leadership abilities — being, for example, a block leader as Khalid was — is undoubtedly appreciated on the ground by the guard force and their commanders, it tends to be looked on less favourably by those higher up the chain of command, who seem to be obsessed with regarding any kind of leadership ability as an indicator that the prisoner in question poses a threat to US security and must continue to be held.

How else are we to accept that Khalid — who was never anything more than a Taliban foot soldier in Afghanistan, and whose benevolent life force has been so impressive in Guantánamo — continues to be held, 18 years and three months since his initial capture, and 17 years and ten months since his arrival at Guantánamo?

24 years old at the time of his capture, he is now 43, and wants nothing more than to finally have his long and unjust imprisonment without charge or trial brought to an end.

If you agree — and especially after reading Mansoor’s moving tribute — please share it, and help us to continue to publicize the stories of the men still held at Guantánamo, and not even accused of any kind of involvement with terrorism whatsoever, in this election year. By 2021, we desperately need the kind of leadership in the US that will recognize the injustice of continuing to hold men like Khalid without charge or trial, and the need for Guantánamo to be closed once and for all.

Please also feel free to make a donation to the fundraiser to support Mansoor’s writing in Serbia.

Best Friend and Brother

By Mansoor Adayfi

“We like Khalid to represent all the detainees. He talks like a poet when he speaks on behalf of the detainees, and he’s an easy man to deal with.”

Navy Commander and Camp 6 officer-in-charge (OIC), 2010

“Here is our Soundcloud! I love your voice; it shifts me out of here to my own world.”

A female guard

“If you want things done in the best way, and in a creative way, Khalid is your man.”

Omar, a former detainee at Guantánamo

“Brothers, please take it easy on Khalid, don’t ask too much of him. He doesn’t know how to say no.”

Suhail, a detainee at Guantánamo

My brother and best friend, Khalid Qasim. I first met him in 2002, Camp 1, Golf Block. The situation in the camp was like hell, fear of the unknown, intensive interrogation, torture, and confusion. You need someone to assure you that you will be okay. The words “you will be okay” wasn’t enough. Khalid has his own creative way to tell you that everything is going to be okay, and you will be okay, through his beautiful voice and singing. He started singing songs in the camp, and those words, his rhythm, and his beautiful voice brought us hope and took us to another world that’s not Guantánamo. In no time he was well known as Khalid the singer.

Khalid the singer

Khalid is a caring person. He wants to make everyone feel good and happy, and always tries to make our life less miserable in the camp, either by singing, by his sense of humor, poetry, essays, or by his paintings. Besides singing in Arabic, he learned to sing in English, Russian, Pashto, Urdu, and Farsi. He makes all the nationalities (48 nationalities) who are detained at Guantánamo feel happy and to connect them to themselves. This is Khalid’s special touch.

We had one night a week when we sang and told stories and shared our culture with each other, as men from all over the world, and on that night Khalid would sing for us all, in different languages. it was so beautiful to listen to his singing, I could appreciate how he changed the situation, how detainees called him from other blocks to sing for them. I could see how those detainees loved him when he sang in their language. Even the guards liked and admired him. Some called him “The Star.” They also enjoyed listening to his singing, especially in English.

In no time Khalid was one of the most famous detainees in our Guantánamo world. The camp administration would punish him sometimes for singing, but Khalid never quit. When they moved him to solitary confinement for punishment, he would continue singing there.

In solitary confinement, we were in boxes made of steel — dark, cold, brightly lit, hot, with noise, sleeplessness, and hunger. Here Khalid’s beautiful voice would free us every day and would tell us there is hope. Some detainees would try to meet in the recreation area to ask him to sing for them. He was always busy making others happy.

His handsome face and his kindness, his beautiful voice and his creativity would attract anyone to him.

Khalid the teacher

Khalid started early with poetry, essays, short novels, depending on his memory, and started writing things down as soon as he had a chance to get a pen and paper. He also started drawing using a pen and paper. He learned English and became proficient in writing and speaking. He became a writer in Arabic in English.

Khalid is a good teacher with patience. After learning English, he started teaching. He gave me classes in English when I started learning and would always motivate me. He held classes in Arabic and English, poetry, composing, soccer ball coaching, singing, and painting. He taught both detainees and guards. A guard we nicknamed “Khalid’s student” or “Khalid’s kid” spent nine months learning Arabic with Khalid, and started talking to us in the Arabic language. He taught me how to play soccer. This is a long and funny story, but I got better in the end.

Khalid the player

After ending our hunger strike in 2010, we were moved to Camp 6 to the communal living blocks. The brothers started playing soccer, and each group was looking for a good player so they could win the match. When Khalid played his first match, he scored seven goals. Detainees and guards who were watching the match started cheering for him. Guards always bet on our matches and players. Khalid had his own team and was the team captain. He won many tournaments, and had a lot of fans amongst the detainees, the guards and the camp staff. Navy guards said, “Man! This man is a pro. When he touches the ball, his playing is like a piece of music.”

Playing soccer at Guantánamo was our “Game of Thrones,” and was very competitive between detainees. There were many teams, and good players, and each had their own fans. And there were many injuries too, but not in a bad way.

Khalid the leader

In 2010, in Camp 6, the communal camp, each block had a block leader. Khalid was ours. The Navy Commander who was in charge of Camp 6 (the officer-in-charge, or OIC) liked Khalid, and would always try to get problems solved through Khalid, because of his good English, his understanding, and the way he handles issues.

And like other detainees who speak English, Khalid always translates between detainees and guards, camp staff, and medical staff. This is not an easy job to do because it takes a lot of time and energy.

Khalid the artist

Khalid started making art early, before the art class even started. I don’t recall him going to the art class. He was already a gifted and talented artist. He started using a pen and paper, and his art is powerful and very expressive. Khalid would talk beautifully about his artwork. He gave most of his artwork to detainees, camp staff, and guards. He didn’t like to turn them down. I would always argue with him that he should keep his artwork, but this is Khalid, a kind person, who loves to make others happy.

An example of Khalid Qasim’s artwork, literally made from Guantánamo (from the gravel in the recreation yard), commemorating the three men who died at Guantánamo in June 2006.

An example of Khalid Qasim’s artwork, literally made from Guantánamo (from the gravel in the recreation yard), commemorating the three men who died at Guantánamo in June 2006.Nevertheless, Khalid is an ambitious man, who has beautiful dreams and ideas about how to start a family, and get a degree in English literature and art. He works hard at Guantánamo to prepare himself for college and to build his life when leaves. Unfortunately, the camp administration took the little he had. They took the laptop from the class, and stopped his art from leaving Guantánamo.

I don’t know what the camp administration is trying to accomplish by depriving the men there from learning. I don’t know what kind of men they want those detainees to be when they eventually leave Guantánamo. I hope the US government will understand that it needs to help the men there to prepare themselves for the difficulties they will face after Guantánamo. From my experience, I can’t escape Guantánamo. I face difficulties and hardship every day, but learning English at Guantánamo has helped me in my daily life.

I really miss Khalid. We lived years and years together and developed a strong bond of brotherhood and friendship.

I pray to Allah to hasten Khalid’s release and the release of the other men detained there.

Mansoor Adayfi

Belgrade, Serbia

February 21, 2020

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

March 5, 2020

International Criminal Court Authorizes Investigation into War Crimes in Afghanistan, Including US Torture Program

The logo of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and an image of a secret prison.

The logo of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and an image of a secret prison.Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

Good news from The Hague, as the Appeals Chamber of the International Criminal Court (ICC) has into war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Afghanistan since May 2003 “by US armed forces and members of the CIA, the Taliban and affiliated armed groups, and Afghan government forces,” as the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) explained in a press release.

The investigation, as CCR also explained, will include “crimes against humanity and war crimes … committed as part of the US torture program,” not only in Afghanistan but also in “the territory of other States Parties to the Rome Statute implicated in the US torture program”; in other words, other sites in the CIA’s global network of “black site” torture prisons, which, notoriously, included facilities in Poland, Romania and Lithuania. As CCR explained, “Although the United States is not a party to the ICC Statute, the Court has jurisdiction over crimes committed by US actors on the territory of a State Party to the ICC,” and this aspect of the investigation will look at crimes committed since July 1, 2002.

AS CCR also explained, “The investigation marks the first time senior US officials may face criminal liability for their involvement in the torture program.”

Today’s ruling reversed a previous — and widely-criticized — decision by the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber, on April 12, 2019, not to authorize the investigation that was first submitted by the ICC’s Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda on November 20, 2017. As CCR explained, this was “the first time the ICC had denied a Prosecutor’s request to open an investigation,” and it “came on the heels of overt hostility toward the Court by the Trump administration. US officials threatened to impose sanctions on and criminally prosecute ICC officials and revoked the ICC Prosecutor’s visa to the United States.”

In an effort to deflect attention from the court’s political cowardice, the Pre-Trial Chamber concluded last year that, although “the legal criteria for opening an investigation were satisfied,” because “there was evidence of grave crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court, which were not being prosecuted elsewhere,” the request for an investigation was rejected, because it “would not serve the interests of justice,” because of the court’s speculation that the states concerned “would not cooperate,” and because, as they explained, the “political climate” and “political landscape” would, in CCR’s words, “make a meaningful investigation difficult.”

In response to last April’s ruling, as CCR noted, “Former diplomats, chief prosecutors, and United Nations Special Rapporteurs, as well as other international human rights and criminal law experts and non-governmental organizations, submitted amicus briefs in support of the investigation.”

In addition, at a hearing before the Appellate Chamber in December, attorneys representing victims of the US torture program “argued,” as CCR described it, “that the ICC investigation into the Afghanistan situation represents their last opportunity to obtain some measure of justice for the grave crimes they suffered,” adding, “The United States has been unwilling to investigate and prosecute civilian and military leadership responsible for torture and other grave violations of international law. The ICC is the court of last resort for those who have been denied justice elsewhere.”

CCR represents two men who, as they put it, “were tortured in CIA black sites, proxy-detention, and DoD facilities,” and are now held indefinitely in Guantánamo. These two men, Sharqawi Al-Hajj and Guled Hassan Duran, are “among victims who submitted representations in support of the Prosecutor’s request, detailing their experiences,: and, as CCR also explained — and as I wrote about here — Sharqawi Al-Hajj “recently attempted suicide, cutting his wrists.”

Another former “black site” prisoner who is part of the case — and who was not held in Guantánamo — is Mohammed al-Asad, who, sadly, died in 2016 “without seeing justice done,” as CCR put it, adding that “his wife continues his quest” with the support of the Global Justice Clinic at NYU School of Law. As CCR also explained, “Al-Asad “was secretly detained and tortured in Djibouti and Afghanistan — both Member States of the ICC — as part of the US torture program.”

As CCR also described it, “Other legal teams representing victims before the ICC include Reprieve and the attorneys for Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri,” also held at Guantánamo and charged in seemingly interminable military commission trial proceedings.

Commenting on today’s news, Katherine Gallagher, CCR Senior Staff Attorney and ICC Victims Legal Representative, said, “Today, the International Criminal Court breathed new life into the mantra that ‘no one is above the law’ and restored some hope that justice can be available — and applied — to all. For more than 15 years, like too many other victims of the US torture program, Sharqawi Al-Hajj and Guled Duran have suffered physically and mentally in unlawful US detention, while former senior US officials have enjoyed impunity. In authorizing this critical and much-delayed investigation into crimes in and related to Afghanistan, the Court made clear that political interference in judicial proceedings will not be tolerated.”

Nikki Reisch, Counsel for the Global Justice Clinic at NYU School of Law, said, “On behalf of our client, Mohammed al-Asad and his surviving family, we applaud the Appeals Chamber for rejecting the repugnant logic of the US torture program, which sought to place detainees in a legal black hole and deny them access to justice for the abuses they suffered. At a time when authoritarian tendencies are on the rise, the decision sends an important signal to all states that might does not make right, and that no one is above the law.”

Reprieve represents another Guantánamo prisoner, Ahmed Rabbani, who “was among the victims who supported the appeal.” Rendered to Afghanistan and tortured for 540 days by US personnel, he has been held in Guantánamo since 2004 without charge or trial. Responding to the news that the appeal has been upheld, he said, “If the people who tortured me are investigated and prosecuted, I will be very happy. I would ask just one thing from them: an apology. If they are willing to compensate me with $1 million for each year I have spent here, that will not be enough. I am still going through suffering and torture at present. But I would be happy with just three words: ‘We are sorry.’”

Reprieve’s Deputy Head of UK litigation, Preetha Gopalan, added, “This decision is welcome news to everyone who believes that the perpetrators of war crimes should not enjoy impunity, no matter how powerful they are. This is the first time the US will be held to account for its actions, even though it tried to bully the ICC into shutting this investigation down. That the ICC did not bow to that pressure, and instead upheld victims’ right to accountability, gives us hope that no one is beyond the reach of justice.”

As Reprieve also explained in their press release, “The court’s decision comes at a time when both the US and UK are attempting to block domestic investigations into ‘war on terror’ era torture and rendition. The UK Government is facing a High Court challenge of its failure to hold an independent judge-led inquiry into historic abuses. In the US President Donald Trump recently intervened in three war crimes cases, pardoning two service members and restoring the rank of a third.” Reinforcing the UK angle, the Guardian reported that it is “possible” that “allegations relating to UK troops” could emerge as the investigation proceeds, with, presumably, other NATO forces also not immune to scrutiny of their actions.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which “currently represents Khaled El Masri, Suleiman Salim, and Mohamed Ben Soud — all of whom were detained and tortured in Afghanistan — before the ICC,” also issued a statement, via Jamil Dakwar, director of its Human Rights Program, who said, “This decision vindicates the rule of law and gives hope to the thousands of victims seeking accountability when domestic courts and authorities have failed them. While the road ahead is still long and bumpy, this decision is a significant milestone that bolsters the ICC’s independence in the face of the Trump administration’s bullying tactics. Countries must fully cooperate with this investigation and not submit to any authoritarian efforts by the Trump administration to sabotage it. It is past time perpetrators are held accountable for well-documented war crimes that haunt survivors and the families of victims to this day.”

Note: For further information, visit the Center for Constitutional Rights’ case page.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

March 3, 2020

The Four Fathers Release New Song ‘Affordable’, Marking the Anniversary of the Destruction of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden’s Trees

The cover of the Four Fathers’ new online single, ‘Affordable’, released on March 3, 2020.

The cover of the Four Fathers’ new online single, ‘Affordable’, released on March 3, 2020.Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

Last Thursday, February 27, marked a sad anniversary for environmental activists and housing campaigners, as it was the first anniversary of the destruction of the 74 mature and semi-mature trees that made up the magical tree cover of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, in south east London, which provided an autonomous green space in a built-up urban area, and also mitigated the worst effects of pollution generated by traffic on nearby Deptford Church Street, where particulate levels have been measured at six times the safety levels recommended by the World Health Organisation.

Unfortunately, the struggle to save the trees, which had been ongoing since 2012, largely took place before environmental activism went mainstream, via the actions of Greta Thunberg and Extinction Rebellion, although this was not just an environmental issue. The destruction of the garden was also part of a proposal by Lewisham Council and housing developers to build a new housing development on the site, one that desperate, dissembling councillors sought to sell to the public as providing much-needed new social homes, when the reality, as with almost all current housing developments, is that a significant number of the new homes are for private sale, existing council housing is to be destroyed, and its replacement will be homes that are described as “affordable”, when they are no such thing.

Instead, the allegedly “affordable” component of the development is a mixture of properties at ‘London Affordable Rent’, which, in Lewisham, is 63% higher for a two-bedroom flat than traditional social rents, and ‘shared ownership’, a notorious scam, whereby, in exchange for a hefty upfront payment, occupants are made to believe that they own a share of the property (typically 25%), whereas, in reality, they are only assured tenants unless they find a way to own the property outright, and, along the way, have to pay rent on the share of the property that they don’t, even nominally, own, and are also often subjected to massive — and unregulated — service charges.

At Tidemill, the council stealthily twinned its proposed development with Amersham Vale, in New Cross (the former site of Deptford Green secondary school), and over both sites, where 329 new properties are planned, 131 are for private sale, 54 for shared ownership, and 141 for rent. 13 of those are promised replacements for the tenants in Reginald House, with three leaseholders also promised some sort of exchange for the homes that they thought they owned.

On their website, Lewisham Council lie about the provision of new homes, falsely claiming that, of the 209 new homes planned for Tidemill, “158 (76%) will be affordable”, when in fact, that total is made up of 38 ‘shared ownership’ properties (which shouldn’t be described as “affordable”), and the three “leaseholder properties to be transferred”, as well as 117 properties for rent.

The council’s figures also exclude Amersham Vale, even though the two sites are twinned, because, at Amersham Vale — sickeningly marketed as ‘The Muse’ — two-thirds of the total number of properties (80 out of 120) are for private sale, with just 24 for rent and 16 for ‘shared ownership.’ Over both sites, therefore, the allegedly “affordable” component is actually just 40%, and, as noted above, it remains debatable how affordable the so-called “affordable” rents actually are for those on a low income.

I have regularly described the word “affordable” as one of the most abused words in the English language right now, and in the summer of 2018, as the clock was ticking on Tidemill, I wrote a blistering, punky rock and roll song about it, for my band The Four Fathers, which we premiered, just three days after the Tidemill occupation began, at the Party in the Park community festival in Fordham Park in New Cross, and which has been a regular feature of our live sets ever since.

In December we finally got round to recording it, at Charlie Hart’s Equator Studios in Brockley, with overdubs added in January, and a final mix last month, and I’m delighted to be making it available, to mark this sad anniversary, via Bandcamp, where all our studio recordings can be found.

<a href=”http://thefourfathers.bandcamp.com/tr... by The Four Fathers</a>

At the December recording session — the first with our new bassist, Paul Rooke — we also recorded two other new songs, ‘The Wheel of Life’, a slowish reggae reflection on mortality and transcendence, and ‘This Time We Win’, an anthem for the environmental movement, and we’ll be releasing both of those in the weeks to come, but for now I hope you enjoy ‘Affordable’, and will share it if you do.

The battle to save Tidemill

The Tidemill garden had been designed and laid out, in concentric circles, by pupils, teachers and parents from the old Tidemill primary school at the end of the 1990s, and its circular patterns — which were, to be honest, a bit trippy — contributed significantly to the perception of it as a kind of green Tardis, which definitely felt bigger on the inside than it looked from the outside!

When the school moved, in 2012, guardians installed in the old school — and then representatives of the local community — were given “meanwhile use” of the garden while Lewisham Council finalised plans to redevelop the site with the housing association Family Mosaic (who merged with the giant housing association Peabody in 2016) and the private developer Sherrygreen Homes, part of a group of companies that includes the building company Mulalley, Lewisham Council’s preferred building contractor.

Throughout that time, campaigners sought to prevent the council from destroying the garden — and also from destroying Reginald House, a block of structurally sound council flats next to the garden — as part of their redevelopment proposals. The first wave of campaigners, around 2008, when the plans were first mooted, had successfully removed two bigger blocks of council flats, on Giffen Street, from the plans, but, when it came to Reginald House and the garden, the council and the developers wouldn’t change their minds.

In September 2017, the council finally approved the Tidemill plans, but the news only drew many more campaigners to the garden, to step up the use of the space, and also, unbeknownst to the council and the developers, to hatch plans to occupy it to prevent its destruction. Those who loved the garden’s extraordinary tranquility — especially significant in such an urban area — continued to be drawn to it, as were gardeners, who tidied it up and showed it love, and, as a community-led autonomous space, the garden also hosted musical events, art and craft workshops — and a hustings for the council elections in May 2019.

At the end of August 2019, when the council terminated the “meanwhile use” lease, and asked for the keys back, campaigners occupied the garden instead, a bold move — combining environmental and housing activism — that secured supportive coverage from mainstream media including the BBC, and London-wide, national and global support from activists.

The occupation, which I was part of, was a genuinely extraordinary experience, as we grappled with the day to day running of an occupation site, with all the issues that involved — some involving solidarity in action; others involving, for example, vulnerable people drawn to the site (some homeless, some with mental health issues). We also dealt with numerous reporters and academics, had a supportive visit from Sian Berry of the Green Party (now the Party’s co-leader), had films made, fulfilled our pre-arranged inclusion in the international renewed Deptford X arts festival, and continued to campaign against the council and Peabody, over a two-month period, until we were violently evicted, by 130 bailiffs from a notoriously violent (and union-busting) company, County Enforcement, supported by the police.

For months, the bailiffs were paid to guard the garden 24 hours a day, with Cllr. Paul Bell, the Cabinet Member for Housing, admitting in March 2019 that the council had spent £1,372,890 on evicting and guarding the Tidemill site, a cost that has obviously increased since, and which also doesn’t take into account the £1m-plus that has been spent on guarding the old Tidemill school. A reasonable estimate, therefore, would be that around £3m has been pointlessly spent at Tidemill, where building work has still not even started.

Along the way, the most prominent aspect of the council’s post-eviction activities has been the destruction of the trees on February 27 last year, an act of premature vandalism that can only be regarded as a spiteful response to the development’s opponents, just as the eviction was a premature, and violent response to the occupation. In case anyone is in any doubt about this, it’s important to remember that a review of the legality of the development, launched and paid for by the garden’s defenders, was still before the courts as bailiffs tore into the garden at dawn on October 29, 2018, dressed in skull masks, screaming as though Deptford was the jungle in ‘Apocalypse Now’, and subsequently endangering the life of a young activist who had climbed to the top of a slender tree to try to delay the eviction.

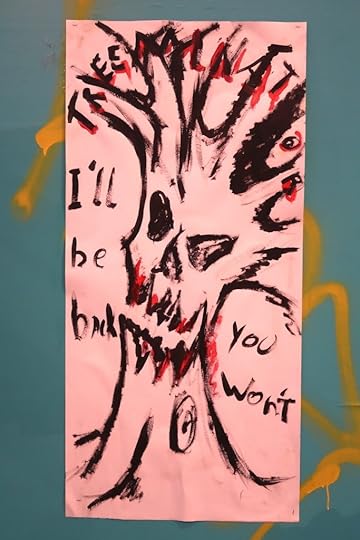

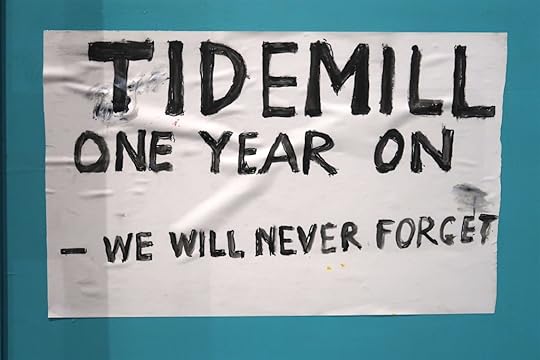

Last Thursday, activists remembered the day of the trees’ destruction by putting up handmade posters, commemorating the trees and continuing to criticise the garden’s destruction, on the Peabody-blue hoardings surrounding it. Within 12 hours, the posters were removed, as Lewisham Council, Peabody and Sherrygreen Homes continue to try to pretend that they are engaged in important work for the community, and to stifle any notion of ongoing dissent. However, I’ve published photos of some of the posters below, to keep their message alive despite the clampdown, and, as with ‘Affordable’, I’d be delighted if you’d share them.

Note: Please also be aware that Lewisham Council’s dubious activities with regard to housing don’t stop at Tidemill and Amersham Vale. At Besson Street in New Cross, they are still engaged in plans to build new homes for market rent with a private developer, and at Achilles Street in New Cross they recently secured approval for the complete destruction of a housing estate and associated shops via a rigged ballot process.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

February 26, 2020

Photos and Report: The Launch of “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison” at CUNY School of Law in New York

One of the extraordinary ships made out of recycled materials at Guantánamo by Moath al-Alwi, who is still held, as shown in the exhibition, “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison,” at CUNY School of Law in New York (Photo: Elena Olivo).

One of the extraordinary ships made out of recycled materials at Guantánamo by Moath al-Alwi, who is still held, as shown in the exhibition, “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison,” at CUNY School of Law in New York (Photo: Elena Olivo).Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

Last week was the launch of “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison,” a powerful new art exhibition featuring work by eleven current and former Guantánamo prisoners at CUNY School of Law’s Sorensen Center for International Peace and Justice, in Long Island City in Queens, New York, which I wrote about in article entitled, Humanizing the Silenced and Maligned: Guantánamo Prisoner Art at CUNY Law School in New York.

This is only the second time that Guantánamo prisoners’ artwork has been displayed publicly, following a 2017 exhibition at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, also in New York, which became something of a cause célèbre after the Pentagon complained about it. That institutional hissy fit secured considerable sympathy for the prisoners — and criticism for the DoD — but in the end the prisoners lost out, as the authorities at Guantánamo clamped down on their ability to produce artwork, and prohibited any artwork that was made — and which the prisoners had been giving to their lawyers, and, via their lawyers, to their families — from leaving the prison under any circumstances.

Since the launch, a wealth of new information has come my way, via Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, who represents around ten of the 40 men still held at Guantánamo, and who was one of the main organizers of the exhibition, which is running until mid-March, with further manifestations continuing, I hope, throughout the rest of the year.

Shelby and I have known each other for many years, and when I visited the US last month, on my annual visit to call for the closure of Guantánamo on the anniversary of its opening, I visited CUNY School of Law, to see the early version of “Guantánamo [Un]Censored” that was showing at the time, featuring artwork by Khalid Qasim, one of Shelby’s clients, which I wrote about — and included photos from — in my article last week. Shelby and I later travelled to Harlem, to the Revolution Books store, for a speaking event that, after a day spent discussing the injustices of Guantánamo and the plight of the men still held, was highly-charged emotionally, and the video of that event is here.

Following last week’s launch, Shelby sent me her opening remarks, which I’m posting below, as well as some background to and observations about the exhibition, and a link to photos by Elena Olivo, which I’m scattering liberally throughout the article. The photo below captures some of the large crowd attending the launch, as well as the main organizers and speakers on the night.

From the left: Arpita Vora, Coordinator at the Sorensen Center (in black); L. Camille Massey, Founding Executive Director of the Sorensen Center for International Peace and Justice (in white); Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, Guantánamo lawyer and CUNY School of Law alumna; Aliya Hussain, Advocacy Program Manager at the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR); and Ramzi Kassem, Co-Director of CUNY School of Law’s Immigrant and Non-Citizen Rights Clinic (INRC), which also represents Guantánamo prisoners. CCR and INRC were also organizers of the exhibition, and, at the launch, Shelby, Ramzi and Aliya spoke, after an introduction by Camille.

From the left: Arpita Vora, Coordinator at the Sorensen Center (in black); L. Camille Massey, Founding Executive Director of the Sorensen Center for International Peace and Justice (in white); Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, Guantánamo lawyer and CUNY School of Law alumna; Aliya Hussain, Advocacy Program Manager at the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR); and Ramzi Kassem, Co-Director of CUNY School of Law’s Immigrant and Non-Citizen Rights Clinic (INRC), which also represents Guantánamo prisoners. CCR and INRC were also organizers of the exhibition, and, at the launch, Shelby, Ramzi and Aliya spoke, after an introduction by Camille.Shelby’s opening remarks are posted below:

This is the art that the government tried to completely silence when they learned of its heightened visibility with the last gallery it was in. This is the art they banned and threatened to incinerate. Guantánamo has always been about dehumanizing those imprisoned there and erasing them. Coming out to see this art — and as a result, the artists — is an act of resistance and solidarity.

The stories told of those at the sharp end of the most powerful government in the world are often, almost inevitably, the facts of the oppression: their rendition, their torture, their lack of a trial. Their identities and the depths of who they are — what they want in life, what they laugh at, cry at, fight for and against, what they spend their days thinking about — is erased. Their artwork enables my clients to be heard, to reach audiences across the world in their own terms — by their merits, and not the reliability of their lawyers’ characterisations.

And like their artwork in the first gallery back in 2017, this event reminds the world that they are still there. So many people still don’t know that most have never even been charged with a crime; that these are men and not monsters.

They are creative, and humble, and bright, and loyal people, who have been kept from their families for decades. Their habeas cases may be stayed in futility but their days tick by.

The men our government threw into a dungeon, against every single law ever written—to preserve our “safety”—those men remind us with their artwork who they actually are; that they continue to have hope and dream dreams.

And artwork for them, as it is for so many across time and space, is the way to express those basic tenets of humanity.

Following up on her opening comments, Shelby wrote to me in an email that “the objective — of the entire exhibition — is to provide a platform for the men to be heard, on their own terms, rather than through the words of others, and to combat the purposeful silencing and identity-erasure that GTMO perpetrates.” And as she also explained, since the clampdown that followed the 2017 exhibition, most of the prisoners stopped making art, so “part of the purpose of our event is to facilitate their being heard and to inspire them to start making art again.”

Best known for his ships, Moath al-Alwi has also made more intimate works like this domestic scene (Photo: Andy Worthington).

Best known for his ships, Moath al-Alwi has also made more intimate works like this domestic scene (Photo: Andy Worthington).In total, the work of 13 current and former prisoners is featured; nine artists, and four others providing contributions in other media. As Shelby explained, “CCR provided the art by Ghaleb al-Bihani and Djamel Ameziene [both released], Beth Jacob provided the art by Mohammed al-Ansi [also released], Ramzi that by Moath al-Alwi [still held], Mark Maher [of Reprieve] that of Ahmed Badr Rabbani [stlll held],” and the other artists’ work is a combination of my clients’ and that of former detainees with whom my clients put me in touch” — Khalid Qasim, Sabry Mohammed al-Qurashi and Assadulah Haroon Gul (all still held), and released prisoner Abdulmalik al-Rahabi.

At the launch of the exhibition, “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison,” at CUNY School of Law in New York, a visitor looks at a painting by released prisoner Ghaleb al-Bihani (Photo: Elena Olivo).

At the launch of the exhibition, “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison,” at CUNY School of Law in New York, a visitor looks at a painting by released prisoner Ghaleb al-Bihani (Photo: Elena Olivo).The other contributions, collected by Shelby, were from former prisoner (and talented writer) Mansoor Adayfi, who provided audio anecdotes about life in the prison, poetry from Towfiq al-Bihani, who is still held, and prose from Abdullatif Nasser (still held) and released prisoner and best-selling author Mohamedou Ould Slahi.

A poem by Guantánamo prisoner Towfiq al-Bihani, who is still held, despite unanimously being approved for released by a high-level government review process established by President Obama in 2009. The poem is being shown in the exhibition, “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison,” at CUNY School of Law in New York (Photo: Elena Olivo).

A poem by Guantánamo prisoner Towfiq al-Bihani, who is still held, despite unanimously being approved for released by a high-level government review process established by President Obama in 2009. The poem is being shown in the exhibition, “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison,” at CUNY School of Law in New York (Photo: Elena Olivo).As Shelby also explained, the entire project — “a GTMO art gallery hosted by CUNY Law whose scope expanded upon John Jay’s ‘Ode to the Sea’ theme and incorporated as many artists as we could find” — had been in the works for at least three years, and it seems appropriate that it has ended up at CUNY, because as Shelby also explained, “I initially reached out to CUNY Alumni Relations when I noticed professional artwork on display at CUNY and asked if they’d consider a GTMO exhibition and my beloved CUNY community leapt at the idea. Camille Massey and Alizabeth Newman (Int. Executive Director, Alumni Engagement & Initiatives, CUNY Law) paid me a visit and looked through the enormous collection of artwork that I had from my clients alone (collected pre-ban, but not showcased in John Jay just due to the sheer volume of it, and consistency with their theme).”

In addition, Shelby explained that the organizers also “plan to have a series of events while the gallery is up, including one centering on ‘storytelling’ and countering the predominant government narratives,” and, hopefully, “a final event with a distinguished speaker in conversation with Ramzi as part of the Sorensen Center’s ‘Critical Voices’ series.”

In the meantime, please help to get the prisoners’ voices heard by sharing this article as widely as possible, and do get in touch if you have any ideas about how those of us who recognize the importance of getting the wretched prison at Guantánamo Bay closed down once and for all can build momentum from this exhibition, and get some significant mainstream media coverage.

Art by various Guantánamo prisoners, as featured in in the exhibition, “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison,” at CUNY School of Law in New York (Photo: Elena Olivo).

Art by various Guantánamo prisoners, as featured in in the exhibition, “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison,” at CUNY School of Law in New York (Photo: Elena Olivo).* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

February 22, 2020

Humanizing the Silenced and Maligned: Guantánamo Prisoner Art at CUNY Law School in New York

Artwork by Guantánamo prisoner Khalid Qasim, still held without charge or trial, showing in “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison,” an exhibition at CUNY School of Law in New York.

Artwork by Guantánamo prisoner Khalid Qasim, still held without charge or trial, showing in “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison,” an exhibition at CUNY School of Law in New York.Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

For the men held in the US government’s disgraceful prison at Guantánamo Bay, where men have now been held for up to 18 years, mostly without charge or trial, the US authorities’ persistent efforts to dehumanize them — and to hide them from any kind of scrutiny that might challenge their captors’ assertions that they are “the worst of the worst” and should have no rights whatsoever as human beings — have involved persistent efforts to silence them, to prevent them from speaking about their treatment, and to prevent them from sharing with the world anything that might reveal them as human beings, with the ability to love, and the need to be loved, and with hopes and fears just like US citizens.

Cutting through this fog of secrecy and censorship, “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison” is an exhibition of prisoners’ art that is currently showing in the Sorensen Center for International Peace and Justice at CUNY (City University of New York) School of Law, based in Long Island City in Queens. The exhibition opened on February 19, and is running through to the middle of March. Entry is free, and anyone is welcome to attend.

As the organizers explain on the CUNY website, “The exhibit showcases artworks — the majority of which have never before been displayed — of eleven current and former Guantánamo prisoners, and includes a range of artistic styles and mediums. From acrylic landscapes on canvas to model ships made from scavenged materials such as plastic bottle caps and threads from prayer rugs, ‘Guantánamo [Un]Censored’ celebrates the creativity of the artists and their resilience.”

The organizers also quote Moath al-Alwi, a Yemeni national and a client of CUNY Law School’s Immigrant and Non-Citizen Rights Clinic (INRC), who is one of the 40 men still held at Guantánamo, discussing what his artwork — the “model ships made from scavenged materials,” mentioned above — means to him. As he says, “Despite being in prison, I try as much as I can to get my soul out of prison. I live a different life when I am making art.”

The prisoners whose work is featured in the exhibition — represented by INRC, Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, Reprieve and the Center for Constitutional Rights — include six men still held — Khalid Qasim, Sabry Mohammed al-Qurashi, Towfiq al-Bihani, Ahmed Badr Rabbani and Assadulah Haroon Gul, as well as Moath al-Alwi — and five who have been released: Mohammed al-Ansi, Abdulmalik al-Rahabi, Ghaleb al-Bihani, Djamel Ameziane and Mansoor Adayfi.

As mentioned above, most of the artwork on display has not been seen before, but the works that have been seen were shown a little over two years ago at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, in a show, “Ode to the Sea: Art From Guantánamo Bay,” that not only gave an insight into the prisoners’ humanity — and in some cases revealed genuine artistic talent — but also reflected well on the authorities at Guantánamo, who, after far too many years of preventing the prisoners from engaging in any kind of self-expression, had allowed men regarded as “well-behaved” to attend art classes.

All this good will, however, was shattered when the Pentagon, mistakenly inferring that current prisoners were seeking to sell their artwork, retaliated by threatening to destroy prisoners’ artwork, and to prevent them from making any more art in future. The Pentagon’s absurd overreaction was bad PR for them, making the show much more popular than it would have been, and attracting significant mainstream media coverage — and criticism of the Pentagon’s position. I wrote about it at the time, in a number of articles, including Persistent Dehumanization at Guantánamo: US Claims It Owns Prisoners’ Art, Just As It Claims to Own Their Memories of Torture and The Guantánamo Art Scandal That Refuses to Go Away, and I reviewed the show, after I visited it in January 2018, here.

In the long run, however, the most lasting damage was at Guantánamo, where, although prisoners were allowed to resume making art, they were prevented from giving it to their lawyers, as gifts for them and for their families, a clampdown that has disillusioned and disincentivized many of the men, who were only interested in producing artwork if they were able to give it to those they were close to.

The CUNY show that has just opened is hugely important, as a renewed effort to show the prisoners as human beings, and also to highlight the unfairness of the Pentagon’s clampdown.

Although I missed the launch on February 19, I visited CUNY School of Law last month, when a version of the current exhibition was taking place, launched on January 11 (the 18th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo), which focused on the work on just one prisoner — Khalid Qasim (aka Khaled Qassim), whose case has long been of interest to me.

Of the 40 men still held, around half are regarded as “high-value detainees,” and are held in a secretive facility known as Camp 7, while the rest of the men — the “lower-value detainees” — are held in the more public Camp 6, and while it would be a mistake even to accept that all the men identified as “high-value” are in fact of significance, the “lower-value detainees” very noticeably contain men who, by any objective analysis, don’t pose any kind of threat, having never been anything more than low-level foot soldiers in Afghanistan, recruited to take part in a long-running inter-Muslim civil war that, after 9/11, suddenly morphed into a war against the US.

Khalid Qasim is one of these men; only, it seems, regarded as a threat because, in his nearly 18 years at Guantánamo, brutalized in those early years, and never charged or tried for any kind of crime, he was a persistent hunger striker, and had what was perceived as a “bad attitude” to the circumstances of his imprisonment.

Artwork by Guantánamo prisoner Khalid Qasim, showing in “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison,” an exhibition at CUNY School of Law in New York.

Artwork by Guantánamo prisoner Khalid Qasim, showing in “Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison,” an exhibition at CUNY School of Law in New York.Guided by Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, who is co-counsel for Qasim and around ten other prisoners, I was able to appreciate his work far more than I would have, had I been left to my own devices. The photo above, for example, is, quite literally, made of Guantánamo, consisting of gravel collected by Khalid from the prison’s recreation yard, mixed with broken-up MRE (Meals-Ready-to-Eat) boxes, and then glued in place. I found that very powerful conceptually, and was then quite moved when Shelby explained that the three red bars signify the three men who died on the night of June 9, 2006, in what the authorities called a suicide pact, but which numerous other people — including serving US personnel at the base at the time — have suggested was a cover-up for the fact that they were killed.

Similarly, when it came to a gravel, glue and MRE painting of a candle, I would not have realized that it, too, represented a prisoner who had died. Nine men have died in total at the prison since it opened in January 2002 — many under dubious circumstances, and all slandered in death by the authorities — and to commemorate them Khalid painted nine candles, each given to a member of his family. As Shelby explained, they were “taken off the base in groups of two and three,” because Khalid “was afraid that paying respect to the deaths of his fellow prisoners would be silenced by the censors at Guantánamo.”

Another gravel, glue and MRE painting — at the top of this article — is Khalid’s bold statement of a single word — “No” — and, in an unclassified note to Shelby in May 2017, he explained what it meant. As he put it, “I refuse oppression of any kind from anyone even if it is from those closest to me. I strongly expressed my objection when I was forcefully taken out of my cell for feeding. Before the F.C.E. [forced cell extraction] camera (and in the presence of guards, medical staff, high ranking officials and my fellow detainees), I said NO to unjust rules, NO to giving in and NO to giving up.”

In addition, as Shelby explained, because Khalid was “rightly concerned that a piece reading ‘NO’ would not make it through the GTMO censors to the world outside, he chose to write his name upside-down so as to incline a casual reader to understand the piece to read an innocuous ‘ON.’”

Also on display were more classical paintings, heavily covered with primer so that they look like Renaissance paintings, showing symbolic or allegorical scenes relating to imprisonment, which, presumably, were taxing to the military’s art reviewers and censors, who were ridiculously paranoid that the men’s art might contain coded messages to Al-Qaeda. This was an absurd position when, more logically, what they were far more likely to contain — if they strayed off the innocuous picture postcard scenes chosen as subjects by many of the prisoners — would be oblique commentaries about the dreadful circumstances of their confinement, rather than any terrorist connection that never existed in the first place.

One of Khalid Qasim’s symbolic paintings.