Andy Worthington's Blog, page 13

June 24, 2020

Military Judge Rules That Terrorism Sentence at Guantánamo Can Be Reduced Because of CIA Torture

Guantánamo prisoner Majid Khan, in a photo taken at the prison in 2018, and the military commissions judge, Army Col. Douglas K. Watkins, who has ruled that his sentence, based on a plea deal agreed in 2012, can be reduced because he was tortured in “black sites” by the CIA.

Guantánamo prisoner Majid Khan, in a photo taken at the prison in 2018, and the military commissions judge, Army Col. Douglas K. Watkins, who has ruled that his sentence, based on a plea deal agreed in 2012, can be reduced because he was tortured in “black sites” by the CIA.Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

It’s been nearly two years since I last reported on the military commission trial system at Guantánamo, which is less an oversight than a tacit acknowledgement that the entire system is broken, a facsimile of justice in which the defense teams for those put forward for trials are committed to exposing the torture to which their clients were subjected in secret CIA “black sites,” while the prosecutors are just as committed to keeping that information hidden.

I’m pleased to be discussing the commissions again, however, because, in a recent ruling in the case of “high-value detainee” Majid Khan, a judge ruled that, as Carol Rosenberg described it for the New York Times, “war court judges have the power to reduce the prison sentence of a Qaeda operative at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, as a remedy for torture by the CIA.”

When I last visited the commissions, the chief judge, Army Col. James L. Pohl, who had also been the judge on the case of the five men accused of involvement in the 9/11 attacks since the men were arraigned in May 2012, had just caused a stir by ruling that confessions obtained by so-called “clean teams” of FBI agents, after the men were moved to Guantánamo from the CIA “black sites” where their initial confessions were obtained through the use of torture, would not be admitted as evidence. In a second blow, he announced his resignation.

While Col. Kohl was 67 years old, his successor, Marine Col. Keith A. Parrella, was just 44, although he evidently lacked his predecessor’s stamina, as he only made it to May 2019 before announcing that he would be taking up a new job commanding the Marine Corps Embassy Security Group in June.

Col. Parrella was replaced by Air Force Col. Shane Cohen, but he only lasted nine months, announcing in March this year that he was “retiring from active duty military in July,” and that his last day on the bench would be April 24. Col. Cohen said that he was leaving “based on the best interests of my family,” but it must surely also be connected to the fact that he allowed secret in-court communication between the CIA and prosecutors. In addition, his departure has thrown into doubt the January 2021 date he had enthusiastically set for the 9/11 trial to begin, 19 years and 4 months after the 9/11 attacks, and nearly 18 years since the alleged mastermind of the attacks, Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, was captured in Pakistan.

As NPR explained, Col. Cohen’s announcement was “the latest of many disruptions in the controversial and problematic case, which has cost US taxpayers at least $6 billion since 2002.” It also came “a month after another prominent Guantánamo legal figure effectively asked to quit.” In February, James P. Harrington, the lead attorney for Ramzi bin al-Shibh, one of the five men charged in the 9/11 trial, “requested Cohen remove him from the case, citing health issues and ‘incompatibility’ with his client.”

As a fourth judge is sought to take the poisoned chalice that is the judge’s chair in the 9/11 trial, another judge, Army Col. Douglas K. Watkins, who was appointed in October 2018 to replace Col. Pohl as the commissions’ chief judge, and who was also assigned to the case of Major Khan, delivered a ruling that, like Col. Pohl’s “clean team” ruling, has sent shockwaves through the prosecution team.

Khan, a hapless Al-Qaeda recruit, agreed to a plea deal in 2012, in which it was agreed that he would serve a further 13 years from the date of his sentencing if he testified in connection with the 9/11 trial. As Carol Rosenberg explained, Khan’s guilty plea in 2012 involved him accepting that he worked for Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, and “deliver[ed] $50,000 of Qaeda money that helped finance the 2003 bombing of a Marriott Hotel in Jakarta, Indonesia, that killed 11 people, and plotting other, unrealized terrorist attacks.” She added that the ruling “could have implications for other Guantánamo trials.”

However, Khan’s sentencing has been repeatedly delayed, because the 9/11 trial is stuck in pre-trial hearings, which does nothing to reward him for being what I described two years ago as “a reformed character, who has cooperated fully with the authorities, and ought to be regarded as having paid his debt to society, and to be able to resume his life.”

As Rosenberg also explained, “During his time in the CIA black sites, Mr. Khan says, he was hung from his wrists and kept naked and hooded to the point of wild hallucinations. He was held in darkness for a year, isolated in a cell with bugs that bit him until he bled. A Senate investigation disclosed that in his second year of CIA detention, the agency ‘infused’ a purée of pasta, sauce, nuts, raisins and hummus into his rectum because he went on a hunger strike.”

In his 43-page ruling, Col. Watkins “did not address the veracity of Mr. Khan’s claims. But he said that ‘taken as true, this mistreatment rises to the level of torture.’” He added that “he would decide the facts — and whether Mr. Khan would earn credit — based on evidence about what happened to Mr. Khan in CIA and US military custody during a presentation to his sentencing jury, a panel of military officers.” No date has been set for sentencing, but Col. Watkins also said that “Mr. Khan and his lawyers could make additional presentations beyond what the jury hears.”

Prosecutors, in contrast, “had argued that the judge had no such authority because, unlike in the court-martial cases that Colonel Watkins hears as an Army judge, there was no explicit provision for it in the manual for the commissions, which are a hybrid of military and civilian tribunals.” Col. Watkins, however, disagreed. As he explained in his ruling, “The defense has met their burden in this commission to show, by a preponderance of the evidence, that this military judge has the inherent authority to grant a remedy in the form of administrative sentencing credit for abusive treatment amounting to illegal pretrial punishment, especially when no other remedy is available.”

Responding to the ruling, Scott Roehm, the Washington policy director for the Center for Victims of Torture, said, “A military commission has taken a meaningful step toward a CIA torture victim receiving some type of modest reparation or remedy, a step that no other US government institution has taken.” He called the ruling “the most basic acknowledgment of the United States’ obligations, and Mr. Khan’s rights, under the Convention Against Torture,” adding, “The bigger test in this case will be whether Judge Watkins actually grants the pretrial punishment credit Mr. Khan deserves.”

The chief defense counsel, Marine Brig. Gen. John G. Baker, called it “a watershed decision.” As he described it, “It is about time that we see a means to hold the government accountable for the reprehensible torture of Mr. Khan and other commission defendants in a court a law. While it may seem obvious that being tortured by government actors should have some effect on a defendant’s ultimate sentence, the prosecution has disagreed every step of the way.”

As Rosenberg explained, prosecutors had attempted to argue that, “because he pleaded guilty, Mr. Khan had no right to seek the credit.” Col. Watkins, however, again disagreed, stating, “He did not bargain away or waive any credit for the conditions under which he has been detained at any point in time since his capture in 2003.”

Khan’s attorney, J. Wells Dixon of the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights, explained that he read the judge’s decision as also “open[ing] the door to a claim that Mr. Khan was denied due process because he was not given access to a lawyer in his first year at Guantánamo.” He called the opinion “a recognition of the universal prohibition on torture that exists throughout all bodies of law, including the military commissions at Guantánamo,” and noted that the judge had quoted William Blackstone, described by Rosenberg as “the 18th-century British jurist whose treatises are a foundation of American law,” and who averred that, “in the dubious interval” between capture, detention and trial, “a prisoner ought to be used with the utmost humanity.”

There could hardly be a more poignant reminder of how, in Majid Khan’s case, the very opposite was true — and I very much hope that we will hear, in due course, that his sentence will be reduced.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 22, 2020

Thoughts on the Summer Solstice – and Video of The Four Fathers’ Set for the Virtual Stonehenge Free Festival

A lonely Stonehenge on the summer solstice 2020, and The Four Fathers playing a solstice set for the Virtual Stonehenge Free Festival.

A lonely Stonehenge on the summer solstice 2020, and The Four Fathers playing a solstice set for the Virtual Stonehenge Free Festival.Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

Normally, for the summer solstice, the longest day of the year, I write an article about Stonehenge, the ancient temple aligned on the solstices, discussing its long and contested history, and the crowds who have gathered there to celebrate the solstice sunrise. If this is of interest, then please feel free to check out my articles from 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2017, 2018 and 2019.

My fascination with Stonehenge dates back 37 years, to when I was a student and visited the Stonehenge Free Festival, in 1983 and 1984 — visits that not only awakened in me an interest in ancient sacred sites, but also showed me the reality of an alternative lifestyle outside of the prevailing model of nuclear families in Margaret Thatcher’s Britain.

The festival, which had started in 1974, had grown to become a huge autonomous gathering that occupied the fields opposite Stonehenge for the whole of the month of June — and which has been accurately described as “a working exercise in collective anarchy” — until its violent suppression in 1985, when a convoy of travellers making their way to Stonehenge to set up what would have been the 12th festival were ambushed by 1,400 police from six counties and the MoD, and were then violently “decommissioned”, in one of the most shocking episodes of state brutality against unarmed men, women and children in modern British history, which has become known as the Battle of the Beanfield.

21 years after my first visit to the festival as a 20-year old student, the fascinations awakened by that visit — and the shocking reverberations from the Battle of the Beanfield — found voice in my first book, Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion, a counter-cultural history of Stonehenge, in which I told the stories of all the various outsiders drawn to Stonehenge over the centuries, mixing those accounts with reflections on how it was perceived by archaeologists and the state. Because of Stonehenge’s importance to so many colourful individuals and movements, the book was also something of a counter-cultural history of post-war Britain.

My second book, The Battle of the Beanfield, followed in 2005, featuring transcripts of interviews with many of those involved in the events of that dreadful day, as recorded for the 1991 documentary ‘Operation Solstice’, shown on Channel 4, as well as excerpts from the police log, and opening and closing chapters that I wrote, with input from the publisher, Alan Dearling.

Looking back on those times now, the extent to which the state was prepared to go to shut down a modern nomadic movement ought to remain permanently disturbing, but sadly most people don’t know about it, and don’t know how, for the next 14 years, a military-type exclusion zone was established around Stonehenge every summer solstice, which only came to an end in 1999, when the Law Lords, then the highest court in the land, ruled that the exclusion zone was illegal.

In 2000, in response, English Heritage, which manages Stonehenge, was obliged to introduce ’Managed Open Access’ for the summer solstice, allowing visitors to congregate in the stones (which are normally off limits) for the solstice dawn. The great irony, of course, is that, during the days of the festival, only a few hundred people generally made their way to the stones from the festival site for the solstice dawn, whereas, since 2000, the stones have ended up as the focal point for an all-night party (albeit one without any amplified music) of up to 30,000 people.

This year, of course, ‘Managed Open Access’ was cancelled because of the coronavirus, with English Heritage responding by streaming the solstice live worldwide, from an empty temple, while a handful of Stonehenge aficionados held a ceremony outside.

Elsewhere, meanwhile, other online solstice celebrations took place, including the Virtual Stonehenge Free Festival, which my friend Neil Goodwin (co-director of ‘Operation Solstice’) had set up, and which I helped launch on June 1, the 35th anniversary of the Battle of the Beanfield, with a talk about the Beanfield anniversary on the virtual main stage, followed by a few songs by my band The Four Fathers, played by me and my son Tyler (aka award-winning beatboxer The Wiz-RD), as well as a Wiz-RD solo set. The video is available here (or here).

For the solstice, I arranged with Neil to get together with the rest of the Four Fathers (minus our bassist Paul Rooke, who was on a plane back from San Francisco at the time) for a live session from drummer Bren’s back garden — although in the end, although we played live on the afternoon of June 20, we decided that it was impossible to broadcast it live via Facebook, but that we would, instead, film it and make it available via YouTube.

The video — which was posted on the Virtual Stonehenge Free Festival’s Facebook page — is below, and I think we captured a rather lovely solstice vibe, thanks to Bren’s son Jem Horstead, who filmed it and edited it, and is available for commissions, having just finished a film degree at LSBU.

I hope you agree — and I also hope that, sometime in the not too distant future, we’ll be able to entertain you by playing live somewhere, as the charms of the virtual world — while helping in some ways to overcome the isolation of lockdown — also have their limits. We are, after all, social animals, and we need to be able to come together to celebrate, to protest and to enjoy.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 18, 2020

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights’ Ground-Breaking Decision in the Case of Former Guantánamo Prisoner Djamel Ameziane

Former Guantánamo Prisoner Djamel Ameziane and his response to a a recent and important decision taken by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), criticizing the US for his treatment during 12 years in US custody (Image by the Center for Justice and International Law).

Former Guantánamo Prisoner Djamel Ameziane and his response to a a recent and important decision taken by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), criticizing the US for his treatment during 12 years in US custody (Image by the Center for Justice and International Law).Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

I’ve had a busy few weeks, and haven’t been able, until now, to address a recent and important decision taken by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) in the case of Djamel Ameziane, an ethnic Berber from Algeria who was imprisoned at Guantánamo for nearly 12 years, from February 2002 to December 2013, after an initial two month’s imprisonment at Kandahar air base in Afghanistan. The IACHR is a key part of the Organization of American States (OAS), whose mission is “to promote and protect human rights in the American hemisphere,” and whose resolutions are supposed to be binding on the US, which is a member state.

As his lawyers at the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) explained in a press release on May 28, the IACHR’s decision (available here) determined that the United States was “responsible for Mr. Ameziane’s torture, abuse, and decade-long confinement without charge,” and issued a series of recommendations — namely, that “the United States should provide ‘adequate material and moral reparations’ for the human rights violations suffered by Mr. Ameziane for his 12 years of confinement.”

As CCR added, “Some of these measures include the continuance of criminal investigations for the torture of Mr. Ameziane at Kandahar Airbase and Guantánamo Bay detention center; compensation for his years spent in arbitrary detention to address any lasting physical and psychological effects; medical and psychological care for his rehabilitation; and the issuance of a public apology by the United States president or any other high-ranking official to establish Mr. Ameziane’s innocence.”

The decision was, as CCR also explained, “the first decision ever made by a major regional Human Rights body regarding the human rights violations committed at the Guantánamo Bay prison camp,” and marked “a historic victory for Mr. Ameziane and the rights of others detained at Guantánamo Bay to judicial reparations.”

Responding to the decision, Djamel Ameziane said, “I was tortured for more than a decade at Guantánamo, and still suffer from the trauma of my horrible experience. The Commission’s decision is a significant step towards reparations for me and for other Muslim men and boys who were unjustly detained and abused in Guantánamo Bay during the dark days of the ‘War on Terror.’”

He added, “I urge the United States to honor the Commission’s recommendations, acknowledge the serious harms that we suffered, and close the prison camp. Guantánamo Bay must end. I am especially concerned about my fellow Algerian, Sufyian Barhoumi, who has been cleared for transfer for many years but continues to be held indefinitely. Sufyian, we have not forgotten you, and pray for your safe return home.”

“Tea on a Checkered Cloth,” artwork by Djamel Ameziane, made in Guantánamo, 2010. Djamel was one of the prisoners whose art was featured in “Ode to the Sea: Art from Guantánamo Bay,” an exhibition that ran at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York in 2017-18.

“Tea on a Checkered Cloth,” artwork by Djamel Ameziane, made in Guantánamo, 2010. Djamel was one of the prisoners whose art was featured in “Ode to the Sea: Art from Guantánamo Bay,” an exhibition that ran at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York in 2017-18. Ameziane, born in 1967, had left Algeria in 1992 to escape persecution, ending up in Austria, where he became a prominent chef at an Italian restaurant in Vienna. In 1995, however, as CCR explained in a profile of him in 2008, “more restrictive immigration policies kept Djamel from extending or renewing his visa, and his work permit was denied without explanation.” He then traveled to Canada, applying for asylum, and working “for an office supply company and for various restaurants in Montreal.” However, in 2000, his asylum application was turned down, and so, “fearful of being forcibly returned to Algeria and with few options, Djamel went to Afghanistan, where he felt he could live freely without discrimination as a Muslim man, and where he would not fear deportation to Algeria.”

As CCR added, “Once in Afghanistan, he did not participate in any military training or fighting and, as soon as the war started, he fled to escape the fighting. He was captured by local police while trying to cross the border into Pakistan, and was turned over to US forces for a bounty. Later, in Guantánamo, soldiers told Djamel that the Pakistanis sold people to them in Afghanistan for $2,000, and in Pakistan for $5,000.”

Nevertheless, like everyone who ended up in US custody at this time, Djamel was treated appallingly in Kandahar, and then at Guantánamo. Describing one experience, in the prison’s early years, when horrible abuse was widespread, CCR described how, “In one incident, guards sprayed him all over with cayenne pepper and then hosed down with water to accentuate the effect of the pepper spray and make his skin burn. They then held his head down and placed a running water hose between his nose and mouth, running it for several minutes over his face and suffocating him, repeating the operation several times.” Recalling that experience, he stated, ‘I had the impression that my head was sinking in water. Simply thinking of it gives me the chills.’”

As CCR added, “Following that episode, the guards bound him in cuffs and chains and took him to an interrogation room, where he was left for several hours, writhing in pain, his clothes soaked while air conditioning blasted in the room, and his body burning from the pepper spray. He has spent as many as 25 and 30 hours at a time in the interrogation room, sometimes with techno music blasting, ‘enough to burst your eardrums.’”

Ac CCR explained in its recent press release, “the IACHR determined that Mr. Ameziane suffered abuse and torture at the hands of prison camp officers; dealt with long periods of solitary confinement; was beaten during interrogation; did not receive medical care for injuries sustained during his confinement; was prevented from practicing and insulted for his religious beliefs; and was denied regular contact with his family.”

CCR added that the IACHR recognized that the US had also “violated the principle of non-refoulement, when it forcibly returned Ameziane to his home country of Algeria, which he had fled from fear of violence and persecution, particularly for being a member of the Berber ethnic minority.” As CCR also noted, “At the time, Mr. Ameziane was the beneficiary of protective measures issued by the Commission.”

This was indeed the case. The IACHR had first been alerted to Djamel’s case in 2008, when they had stated, “All necessary measures must be taken to ensure Djamel Ameziane is not transferred to a country where he would face persecution.” In 2010, after CCR hooked up with CEJIL (the Center for Justice and International Law), an organization advocating for the defense and promotion of human rights in the Americas, whose main objective is “to ensure full implementation of international human rights standards in the Member States of the Organization of American States,” Djamel became the first Guantánamo prisoner to have a hearing before an international body, when the IACHR heard his case, and in March 2012, as I reported at the time, the IACHR issued “a landmark admissibility report” in his case, marking the first time the organization had accepted jurisdiction over the case of a Guantánamo prisoner.

The IACHR then began to “move to gather more information on the substantive human rights law violations suffered by Djamel Ameziane — including the harsh conditions of confinement he has endured, the abuses inflicted on him, and the illegality of his detention,” and in September 2017 held a hearing in Mexico City, which I wrote about here, to which Djamel submitted a statement, which I published here, in which he pointed out that “Guantánamo was created to destroy people, to destroy Muslims.”

I’m delighted that, ten years after Djamel’s case was first submitted to the IACHR, the Commission has issued such a powerful ruling, and I note too that, as CCR described it in their press release, they also made “several conclusions about the prison camp more broadly: that the United States should establish a truth commission to investigate the prison camp and prosecute all those implicated in acts of torture between 2002 and 2008, among other measures”, and also urged the US “to take all steps necessary to comply with the recommendations made in 2015,” in the IACHR report. “Towards the Closure of Guantánamo,” including “providing detainees with adequate medical, psychiatric, and psychological care, access to justice, and ultimately, the closure of Guantánamo.”

Of course, Donald Trump has no interest in the IACHR’s powerful decision in Djamel Ameziane’s case, but all decent people in the US and around the world — as well as human rights organizations globally — do care, and should take heart that this decision will strengthen calls for the prison’s closure when, one day, Donald Trump is no longer in charge.

As J. Wells Dixon, a senior staff attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights, and Mr. Ameziane’s long-time counsel, said, “Guantánamo Bay is a human rights disaster and should be closed with the urgent assistance of OAS Member states.” Francisco Quintana, program director for the Andean Region, the Caribbean, and North America at CEJIL, added, “Djamel Ameziane’s case is not only emblematic of the abuses committed against men arbitrarily detained during the so-called War on Terror, but of the long struggle towards truth, justice, and reparations many of these men will face and the possibility of obtaining some measure of peace. We will continue to stand in solidarity with Mr. Ameziane and monitor the situation at Guantánamo Bay until the center is shut down and those who suffered abuse at the camp are repaired in full.”

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 14, 2020

No Justice, No Peace on the Third Anniversary of the Grenfell Tower Fire

The Grenfell Silent Walk on December 14, 2017, commemorating those who died in the fire that engulfed Grenfell Tower in west London six months earlier, on June 14, 2017. The Silent Walks took place every month until the coronavirus lockdown hit.

The Grenfell Silent Walk on December 14, 2017, commemorating those who died in the fire that engulfed Grenfell Tower in west London six months earlier, on June 14, 2017. The Silent Walks took place every month until the coronavirus lockdown hit.Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

Since the very public murder of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis three weeks ago, there has been a welcome and understandable resurgence of the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement that first surfaced back in 2014, after a spate of police murders of unarmed black men and boys in the US.

Today, as we remember the terrible fire at Grenfell Tower in west London, which occurred exactly three years ago, the resurgence of the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement seems entirely appropriate.

72 people died in an inferno that engulfed the 1970s tower block they lived in in North Kensington, an inferno that was caused, primarily, because the structural integrity of the building had been lethally compromised by a re-cladding operation designed to make the tower look more “attractive” — not only had existing windows not been repaired or replaced to make sure that they were fireproof, but the re-cladding involved holes being drilled all over the tower that, on the night that the fire broke out, allowed it to consume the entire tower is an alarmingly short amount of time.

Also unaddressed in the refurbishment was the internal situation in the tower — including the neglect of the fire doors necessary for the compartmentalisation process designed to contain a fire within any flat it broke out in for an hour, allowing sufficient time for the emergency services to arrive.

The Grenfell Tower fire should never have happened, and the fact that it did is the responsibility of those who were meant to ensure the safety of those who lived in it, but who completely failed to fulfil their responsibilities — the Tory government, which was obsessed with cutting regulations to facilitate profiteering and cost-cutting, local government (Kensington and Chelsea Council), the private company (Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation) to which control of the borough’s social housing had been outsourced, and all the various contractors involved in the business of turning structurally sound buildings into death traps. One of the most startling revelations of the fire was that dangerous flammable cladding was actually legal, and that nowhere in the broken chain of command of a neo-liberalised social housing programme was there anyone prepared to point out how wrong — and potentially lethal — this was.

So why did this all happen? Well, the bottom line is that those who live in social housing are regarded as, at best, second-class citizens by those in power. It is arguable that the provision of social housing — rented housing at genuinely affordable rents — has in general been led by people with little regard for their tenants. In the 19th century, god-fearing men taught to believe in looking after those less fortunate than themselves also saw the chance to make a profit out of creating housing for low-paid workers, and the great council house building projects of the 20th century can be seen less as projects that arose spontaneously than as responses to two great national calamities — the First World War and the Second World War, both of which exposed how returning soldiers were faced with chronic housing shortages. Along the way there have undoubtedly been episodes when government, local government and architects all believed in the provision of genuinely affordable housing for low-paid workers, and also designed that housing with vision.

Unfortunately, since Margaret Thatcher began dismantling the notion of the state providing genuinely affordable rented housing — for life — to those in need of it, there has been a concerted effort to demonise those who live in social housing, and particularly on housing estates, with the mainstream media complicit in portraying them as unemployed and/or criminals, a shameful pattern of owner-occupier-led black propaganda that has been disgracefully successful, and that has led to a steady reduction in the availability of social housing, a commensurate increase in the profit-making opportunities for private landlords, and an entrenchment of a society-wide notion of those who live in social housing as second-class citizens.

Three years on from the Grenfell Tower fire, this dark propaganda continues to pollute the discourse around this preventable disaster. It is no wonder that, today, ‘Black Lives Matter’ is being discussed with reference to Grenfell, as many of the tower’s residents were indeed black.

But, in addition, we should also recognise that ‘Brown Lives Matter’, that ‘Refugees’ Lives Matter’, and that ‘Working Class Lives Matter’, as the tower’s inhabitants were a mix of people of diverse backgrounds, but all, crucially, were not part of the ruling elite or those it rules for — primarily itself, but also, to a negotiable degree, the middle class.

Also worth thinking about are the victims of Margaret Thatcher’s drive to sell off council housing — those who lived in flats in Grenfell Tower that had been bought under the ‘Right to Buy’ scheme and were paying market rents to private landlords.

Back in 2018, the Guardian published a memorial to those who died — accounts told by their families and friends — and, in an introductory article, explained how “[t]he makeup of the people who died shows how diverse, open and tolerant Britain has become in the past 30 years (more than half the adult victims had arrived in the country since 1990)”, adding that “[t]here were few white-collar workers among the victims and only seven white Britons , indicative of how the disaster disproportionately affected minority ethnic communities.” 18 of those who died were children, while the oldest victim was 84.

As the Guardian also explained, “There was an Afghan army officer, a Sudanese dressmaker, a British artist and an Italian architect. There was an Egyptian hairdresser, an Eritrean waitress and a Lebanese soldier. There were taxi drivers and teachers, football fans and churchgoers, devout Muslims, big families and working singletons. People whose lives were complicated by health issues or love or both. Neighbours on nodding terms, and friends for life from the flat next door.”

Three years on from the Grenfell Tower fire, as we remember those who died, as we remember that, despite an ongoing official inquiry, no one has been held accountable for what happened on June 14, 2017, and as we remember that, up and down the country, 56,000 people are still living in buildings with dangerously flammable cladding, we should also remember, as with the resurgent ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement, that a broad coalition of all those oppressed by a majority-white elite — on the basis of race and class — are still let down, or actively stigmatised, belittled or oppressed by those in charge, and that, fundamentally, the lives of those who live in social housing are still regarded as disposable by our leaders and those responsible for our safety.

Below is ‘Grenfell’, which I wrote after the fire, and recorded with my band The Four Fathers, featuring, and produced by Charlie Hart.

<a href=”http://thefourfathers.bandcamp.com/tr... by The Four Fathers</a>

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 10, 2020

Never Forget: The “Season of Death” at Guantánamo

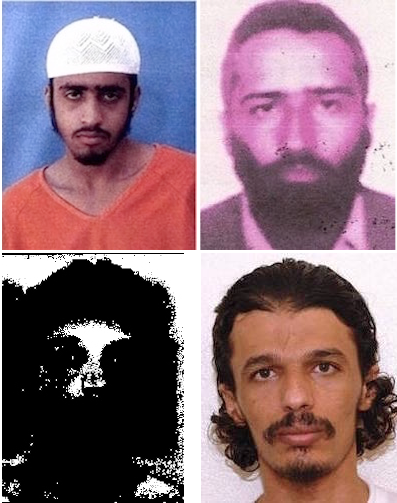

Four of the five prisoners who died at Guantánamo between May 30 and June 9 in 2006, 2007 and 2009, hence my description of it as the “season of death.” The top row shows Yasser al-Zahrani and Ali al-Salami, two of the three men who died on the night of June 9, 2006. No photo exists of the third man, Mani al-Utaybi. The bottom row shows the only photo of Abdul Rahman al-Amri, who died on May 30, 2007, and Mohammed al-Hanashi (Muhammad Salih), who died on June 1, 2009. All the deaths were described by the authorities as suicides, but these claims are disputed.

Four of the five prisoners who died at Guantánamo between May 30 and June 9 in 2006, 2007 and 2009, hence my description of it as the “season of death.” The top row shows Yasser al-Zahrani and Ali al-Salami, two of the three men who died on the night of June 9, 2006. No photo exists of the third man, Mani al-Utaybi. The bottom row shows the only photo of Abdul Rahman al-Amri, who died on May 30, 2007, and Mohammed al-Hanashi (Muhammad Salih), who died on June 1, 2009. All the deaths were described by the authorities as suicides, but these claims are disputed. Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

There are days in your life when events take place and everyone remembers where they were. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 are one example; and depending on your age, others might be the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the moon landing, the fall of the Berlin Wall, Nelson Mandela being freed from prison, and the “shock and awe” of the opening night of the illegal invasion of Iraq.

One of those occasions for me is June 10, 2006, when it was reported that three prisoners at Guantánamo had died, reportedly by committing suicide — two Saudis, Yasser al-Zahrani, who was just 18, and Mani al-Utaybi, and Ali al-Salami, a Yemeni. The authorities’ response was astonishingly insensitive, with Rear Adm. Harry Harris, the prison’s commander, saying, “This was not an act of desperation, but an act of asymmetric warfare committed against us.”

While it remains deeply shocking to me, 14 years on, that suicide could be described as an act of war, this was not the only problem with the authorities’ response to the deaths. The Pentagon’s PR machine swiftly derided the men as dangerous terrorists, even though none of them had been charged or tried for any offence. In fact, one of them, Mani al-Utaybi, had been approved for transfer back to his home country — although the authorities were unable to say whether or not he had been informed of this fact before he died.

Moreover, as I was able to establish from my research at the time for my book The Guantánamo Files, the authorities’ allegations didn’t hold up.

Yasser al-Zahrani, as I explained in my book, “was accused of being a Taliban fighter who ‘facilitated weapons purchases,’ but it was apparent that he was only 17 years old at the time of his capture, and that this scenario was highly unlikely.” In the case of Mani al-Utaybi, meanwhile, “the only ‘evidence’ that he was an ‘enemy combatant’ was his involvement with Jamaat-al-Tablighi, the vast worldwide missionary organization whose alleged connection to terrorism was duly exaggerated by the Pentagon, which had the effrontery to describe it as ‘an al-Qaeda 2nd tier recruitment organization.’”

The third man, Ali al-Salami, was accused of being what the Pentagon described as “a mid- to high-level al-Qaeda operative who had key ties to principal facilitators and senior members of the group,” although these allegations were all made by shadowy, unidentified individuals, including some who had evidently been held in CIA “black sites” and subjected to torture, and were therefore extremely untrustworthy.

What was apparent instead, to anyone who dug a little deeper into the story, was that all three men had been long-term hunger strikers, and, as such, had been a thorn in the side of the authorities.

Describing them, former prisoner Ahmed Errachidi, a bipolar Moroccan chef and longterm British resident, who was released in 2007, wrote in his memoir, The General: The Ordinary Man who Became One of the Bravest Prisoners in Guantánamo, published in 2013, ”Those three had been amongst the finest. They were always ready to help their fellows and they were brave as well. They were men of the highest morale: in the forefront of every protest, they weren’t given to despair. In fact, they kept on smiling even in the most difficult circumstances.”

He added that, although the authorities claimed that they had “found the three hanging in their cells” at 1am on June 10, 2006, “We prisoners refused to accept that the three had killed themselves. We couldn’t understand how it could possibly have happened given that four soldiers were supposed to always be patrolling the block and monitoring us … We believed their deaths were a direct result of torture and were enraged when the administration said they’d committed suicide as part of their war against the USA, which once again made America look like the victim and us look like the aggressors.”

The prisoners were not the only ones to doubt the official narrative. In 2010, Harper’s Magazine published “The Guantánamo Suicides,” a detailed article by Scott Horton based on statements made by Staff Sgt. Joe Hickman, who had been in charge of the guard towers on the night the men died — as well as statements by some of his colleagues. Studying the movement of vehicles on the night, Hickman believed that the men had been killed, whether by accident or design, at a secret facility elsewhere on the base, before being brought back to the main prison, but although he later wrote a book, Murder at Camp Delta, providing even further details about the men’s deaths, the establishment closed ranks and no proper inquiry ever took place.

Other deaths

The three men discussed above were not the only men to die at this time of year at Guantánamo under suspicious circumstances — hence my description of it as the prison’s “Season of Death.”

Last week, I posted on Facebook the only known photo of Abdul Rahman al-Amri, a Saudi who died on May 30, 2007, taken from his classified military file, which was released by WikiLeaks in 2011 — a black and white photocopy that is quite disturbing.

Al-Amri’s death kickstarted my career as an independent journalist, because I had just completed and submitted the manuscript for The Guantánamo Files to my publisher, and, when I read about his death, contacted the Guardian to see if they would be interested in me writing something about him, as I knew his story from my research. They said no, adding that they’d just go with whatever the Associated Press wrote, and so I posted an article about al-Amri’s death on my website — the first of over 2,300 articles that I have now published about Guantánamo on my website — and followed it up with another article about him two days later.

A soldier in the Saudi Army for nine years, al-Amri had traveled to Afghanistan to support the Taliban just before the 9/11 attacks, and was held in Camp 5 at Guantánamo, reserved for the “least compliant and most ‘high-value’ inmates,” according to a US military spokesman. He didn’t have an attorney, and so little was known about him, but the former prisoner Omar Deghayes later told me that he was extremely devout, and had been deeply disturbed by interrogations that had involved sexual abuse. He had also been a long-term hunger striker whose weight had dropped to 90 pounds during the prison-wide hunger strike in 2005, and was apparently still hunger striking before his death.

Omar Deghayes gave me no reason to think that al-Amri’s death wasn’t suicide, but in 2012 the investigative journalist Jeffrey Kaye wrote that “autopsy reports show[ed] that Al Amri was found dead by hanging with his hands tied behind his back, calling into question whether he had actually killed himself,“ and in his book Ahmed Errachidi, noting that al-Amri was “one of the veteran hunger strikers in Camp 5,” also cast doubt on the suicide story, stating, “My experience of Camp 5 told me that it would be impossible for anyone to hang themselves there. The cells there had been designed to prevent suicide or self-harm — the walls were made of concrete and there was no hoop, ring or opening to which a prisoner could tie anything.”

Jeffrey has since written much more about al-Amri’s death — and that of Mohammad al-Hanashi (aka Muhammad Salih), the other prisoner who died during Guantánamo’s “Season of Death” — on June 1, 2009. Another longterm hunger striker, with leadership abilities, like the three men who died in June 2006, he had been spirited away to the prison’s ‘psych’ unit — the behavioral health unit (BHU) — before his death, but as his friend, the released British resident Binyam Mohamed explained after his death, “The BHU was built as a secure unit to prevent, among other things, potential suicide attempts. Everything that someone could use to hurt himself has been removed from the cell, and a guard watches each prisoner 24 hours a day, in person and on videotape. In light of this, I am amazed that the US government has the audacity to describe [his] death categorically as an ‘apparent suicide.’”

In the years since, Jeffrey has undertaken further research into these two deaths, culminating in his 2016 book, Cover-up at Guantanamo: The NCIS Investigation into the ‘Suicides’ of Mohammed Al Hanashi and Abdul Rahman Al Amri, which I urge anyone interested in knowing the truth about Guantánamo’s “Season of Death” to read.

14 years on from the deaths of Yasser al-Zahrani, Mani al-Utaybi and Ali al-Salami, I remember the loss of their lives, as well as those of Abdul Rahman al-Amri and Mohamed al-Hanashi — and the four other men who have also died at the prison since it opened 18 long years ago — and I also remember how the sorrow and indignation that I felt then helped to forge the path that I am still on today — writing relentlessly about Guantanamo, and calling for the closure of this wretched prison, where men are still held without charge or trial, and where the stain of this injustice will not go away until this terrible place is closed once and for all.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 8, 2020

Lockdown Fundraiser: Seeking $2500 (£2000) to Support My Guantánamo Work and My Photo-Journalism Project, ‘The State of London’

Andy Worthington calling for the closure of the prison at Guantánamo outside the White House on January 11, 2020, the 18th anniversary of the prison’s opening, and a section of photos from the coronavirus lockdown in London, as featured on Andy’s Facebook page ‘The State of London.’

Andy Worthington calling for the closure of the prison at Guantánamo outside the White House on January 11, 2020, the 18th anniversary of the prison’s opening, and a section of photos from the coronavirus lockdown in London, as featured on Andy’s Facebook page ‘The State of London.’Please click on the ‘Donate’ button below to make a donation towards the $2,500 (£2,000) I’m trying to raise to support my work on Guantánamo over the next three months of the Trump administration, and/or for my London photo-journalism project ‘The State of London’.

Dear friends and supporters,

Every three months I ask you, if you can, to support my ongoing journalism and activism — mostly on Guantánamo — and my photo-journalism, via my project ‘The State of London’, for which I have no institutional backing. As a very modern version of a freelance journalist, I’m reliant on you, my supporters, to support my work via donations if you like what I do and are able to help.

This is a long-standing arrangement, and it largely arose because there was no room for someone like me in the mainstream media, which didn’t want an expert on Guantánamo writing relentlessly about the prison, the men held there, and why it needs to be closed, and who, in general, dismiss people who are relentlessly dedicated to important causes as “activists” rather than journalists. This is a distinction that I don’t find valid, which serves to largely sideline writers who burn with indignation at injustices in favour of those who embrace “objectivity” — and sadly it tends only to end up supporting the status quo.

On Guantanamo, I have doggedly sought its closure for 14 years now, and have no intention of giving up while it remains open, because its very existence is such a legal, ethical and moral abomination. Your support for my relentless persistence regarding this hugely important but almost entirely forgotten topic is very greatly appreciated.

I continue to publish around 30 articles every three months here on my website, although I also post additional links and thoughts and opinions on Facebook, and, in addition, my photo-journalism — via ‘The State of London’ — has also become an increasingly significant part of my work, in which, every day, I post a photo on Facebook and Twitter taken from what is now eight years of cycling around London’s 120 postcodes, taking photos of the changing face of the city that has been my home for 35 years.

If you can make a donation to support my ongoing efforts to close Guantánamo, and/or my photo-journalism, please click on the “Donate” button above to make a payment via PayPal. Any amount will be gratefully received — whether it’s $500, $100, $25 or even $10 — or the equivalent in any other currency.

You can also make a recurring payment on a monthly basis by ticking the box marked, “Make this a monthly donation,” and filling in the amount you wish to donate every month, and, if you are able to do so, it would be very much appreciated.

The donation page is set to dollars, because the majority of those interested in my Guantánamo work are based in the US, but PayPal will convert any amount you wish to pay from any other currency — and you don’t have to have a PayPal account to make a donation.

Readers can pay via PayPal from anywhere in the world, but if you’re in the UK and want to help without using PayPal, you can send me a cheque (to 164A Tressillian Road, London SE4 1XY), and if you’re not a PayPal user and want to send cash from anywhere else in the world, that’s also an option. Please note, however, that foreign checks are no longer accepted at UK banks — only electronic transfers. Do, however, contact me if you’d like to support me by paying directly into my account.

A changed world

My last fundraiser was at the start of March, when both the US and the UK were waking up to a new threat — the novel coronavirus COVID-19 — which, in the three months since, has changed the world to an extent that, I think, almost no one saw coming, even though governments were repeatedly warned about it by experts.

One of the disastrous effects of the coronavirus is the number of jobs and livelihoods that have been suddenly lost, or put on hold, including a huge number of creative people, and while I’m fortunate not to have been particularly hard hit to date, I completely understand if people are finding funds in short supply when it comes to donating to worthy causes.

The coronavirus, of course, has also featured significantly in my work — in a number of articles that I’ve written, including the following that deal specifically with what it might mean for our future: Imagining a Post-Coronavirus World: Ending Ravenous Capitalism and Our Consumer-Driven Promiscuity, Health Not Wealth: The World-Changing Lessons of the Coronavirus, The Coronavirus Lockdown, Hidden Suffering, and Delusions of a Rosy Future, In the Midst of the Coronavirus Lockdown, Environmental Lessons from Extinction Rebellion, One Year On, Landlords: The Front Line of Coronavirus Greed and Coronavirus and the Meltdown of the Construction Industry: Bloated, Socially Oppressive and Environmentally Ruinous.

The virus — and the lockdown — also came to dominate ‘The State of London’, as I have been out cycling every day and taking photos since the lockdown began on March 23, and, in particular, making repeated visits to the West End and the City, which, at the height of the lockdown, were almost entirely deserted, and seemed like some sort of dystopian future in which all the buildings remained standing, but the people had disappeared. You can see my lockdown photos here, and I hope that my archive of the last three months will lead eventually to a book, some exhibitions and a website. Again, any support you can give will be invaluable, as I have no institutional backing for what has become, over the last eight years, a labour of love.

Thanks, as ever, for your interest in my work. Whether or not you can make a donation, it’s important that I let you know that, without your interest, all that I do would mean nothing.

Andy Worthington

London

June 8, 2020

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign.

June 5, 2020

Elizabeth Warren and 14 Other Senators Ask Pentagon About Coronavirus Protections at Guantánamo

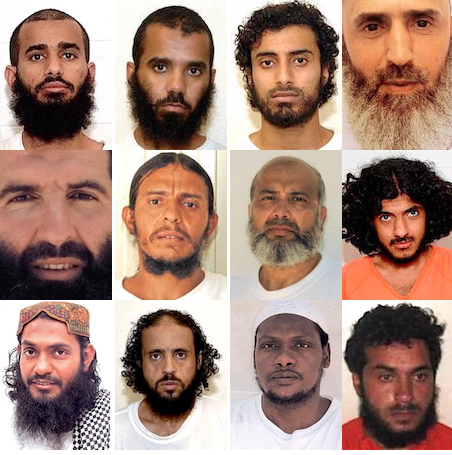

Six of the 15 Senators who have written to defense secretary Mark Esper to ask what protections are being provided to prisoners and US personnel at Guantánamo in response to the coronavirus crisis. Top row, L to R: Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, Dianne Feinstein. Bottom row, L to R: Dick Durbin, Patrick Leahy, Cory Booker.

Six of the 15 Senators who have written to defense secretary Mark Esper to ask what protections are being provided to prisoners and US personnel at Guantánamo in response to the coronavirus crisis. Top row, L to R: Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, Dianne Feinstein. Bottom row, L to R: Dick Durbin, Patrick Leahy, Cory Booker.Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

The prisoners at Guantánamo Bay — held, for the most part, without charge or trial for over 18 years now — have rarely had the support they should have received from the various branches of the U.S. government — the executive branch, Congress and the judiciary — considering how outrageous it is for prisoners of the U.S. to be held in such fundamentally unjust conditions.

Since Donald Trump became president, of course, any pretence of even caring about this situation has been jettisoned. Trump loves Guantánamo, and is happy for the 40 men still held to be imprisoned until they die, and he hasn’t changed his mind as a new threat — the novel coronavirus, COVID-19 — has emerged.

Last week, however, representatives of another group of people with a long history of not doing much for the prisoners — lawmakers — sent a letter to defense secretary Mark T. Esper calling for clarification regarding what, if anything, the Pentagon is doing to “prevent the spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic among detainees in the prison facility at the United States Naval Station Guantánamo Bay, Cuba (Guantánamo), as well as efforts to protect service members responsible for detention operations and all other military personnel at the base.”

The signatories to the letter, initiated by Elizabeth Warren, are Bernie Sanders, Dianne Feinstein, Richard J. Durbin, Patrick Leahy, Jack Reed, Edward J. Markey, Sherrod Brown, Tammy Baldwin, Cory A. Booker, Christopher A. Coons, Jeffrey A. Merkley, Ron Wyden, Benjamin L. Cardin and Thomas R. Carper — all Democrats, apart from Sanders, an Independent.

In their letter, they also noted, “Given current U.S. restrictions on the transfer of detainees off the base and the lack of comprehensive medical infrastructure on the premises, we are concerned that the incidence of COVID-19 on the base combined with an already at-risk detainee population could cause a significant outbreak endangering the health and safety of all.”

The Senators noted the two confirmed incidences of coronavirus on the base — a sailor who was “apparently not involved in detention operations,” whose infection and isolation was announced on March 24, and another individual, “involved in detention operations,” whose positive COVID-19 test was announced on April 7.

“However,” as they proceeded to explain, “it remains unclear whether the Department’s coronavirus infection control efforts will be enough to protect the health of the 40 detainees at the Guantánamo prison facility, some of whom are ‘aging detainees [who] could require specialized treatment for issues such as heart attack, stroke, kidney failure, or even cancer,’” according to “Deprivation and Despair: The Crisis of Medical Care at Guantánamo,” a June 2019 report by the Center for Victims of Torture and Physicians for Human Rights. Citing that same report, the Senators also explained that “there are serious concerns ‘about Guantánamo’s ability to provide medical care to the remaining detainees as time passes and with seemingly no prospect of their release,’ noting that the facility ‘did not have the specialists and equipment necessary’ to care for them.”

Furthermore, as the Senators explained, “This aging and chronically ill population, some of whom retain the mental and physical wounds of torture, may be at greater risk of serious medical complications from COVID-19. Another complicating factor is current U.S.law, which strictly prohibits the transfer of Guantánamo detainees off the base to other U.S. territory. Although the Senate adopted an amendment to a version of the Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) that would have permitted temporary detainee transfers to DoD medical facilities in the United States for ‘emergency or critical medical treatment,’ this provision was not included in the final law.” See my articles here and here about the 2020 NDAA, and how efforts to provide support for the prisoners, and to move towards closing the prison, were shut down.

As the Senators also explained, again drawing on the report cited above, “Some of the Guantánamo detainees’ health conditions are also worsened by the prolonged, indefinite detention […], a form of abuse that has been extensively documented to carry severe and long-lasting health consequences.”

They added, “Given the incidence of COVID-19 at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Station, the serious and deteriorating health conditions of detainees, the deficient infrastructure to care for complex medical needs at the prison facility, and the strict prohibition on detainee transfers to the United States — even temporary transfers for urgent medical reasons — we are concerned that our military personnel responsible for detention operations, as well as the detainees themselves, are at a heightened risk of contracting COVID-19 and suffering severe health consequences.”

As the Senators also explained, “Unfortunately, current rigid restrictions on detainee transfers prevent the United States from securely resettling or repatriating Guantánamo detainees, and in effect, prevent the fair adjudication of cases against any remaining detainees under U.S. domestic criminal law. In particular, an act of Congress would be required to authorize temporary and conditional medical transfers of detainees to DoD medical facilities in the United States.”

The Senators added that “Congress and the Trump Administration should work together to close the Guantánamo Bay prison facility, which represents a ‘legal black hole’ for detainees and reportedly costs $540 million per year to operate, or $13 million per prisoner. In the meantime, we seek to ensure that our detention operations serve the best interest of the health and safety of everyone on base.”

To this end, they asked four questions to conclude their letter, also calling for a response by June 10:

1. What procedures are in place to address a confirmed or presumed positive case of COVID-19 among detainees or military personnel involved in detainee operations? Please include a discussion of the capacity of medical care available at the facility. Are prevention and treatment options at the base consistent with applicable Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) standards?