Andy Worthington's Blog, page 14

May 22, 2020

Coronavirus and the Meltdown of the Construction Industry: Bloated, Socially Oppressive and Environmentally Ruinous

Part of the massive development site at Nine Elms in Vauxhall, photographed on April 16, 2020 (Photo: Andy Worthington).

Part of the massive development site at Nine Elms in Vauxhall, photographed on April 16, 2020 (Photo: Andy Worthington).Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

Just for a while there, it was bliss. The roads were almost entirely empty, the air was clean, birds could be heard singing in central London, and, most crucially, the din of huge construction sites was almost entirely silenced. Construction sites not only generate vast amounts of noise and pollution; they also choke the roads with hundreds of lorries carrying material to them, or carrying away the rubble from buildings that, in general, should have been retrofitted rather than destroyed.

This is because the environmental cost of destroying buildings is immense, and we are supposed to have woken up to the environmental implications of our activities over the last few years, because, in 2018, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warned us that we only had 12 years to avoid catastrophic climate change unless we started arranging to cut our carbon emissions to zero, and, in response, the activism of Greta Thunberg and Extinction Rebellion helped to persuade central governments and local governments to piously declare “climate emergencies”, and to promise to change their behaviour.

Little has been seen in terms of major changes since these “climate emergencies” were declared last year — until, that is, the coronavirus hit. Since then, global pollution levels have dropped significantly — 17% on average worldwide, by early April, compared with 2019 levels, with a 31% decline recorded in the UK.

In London, meanwhile, measurements of carbon dioxide and methane were taken from the top of the BT Tower, and analysed by scientists at the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and the University of Reading, who discovered a 58% drop in carbon dioxide emissions, which, as the Daily Mail noted, “closely mirrors the daily reduction of 60 per cent in traffic flow in central London which Transport for London recorded during the first five weeks of the UK’s lockdown.” The Mail added that, “For May 3, the most recent data available, CO2 emissions were down more than 70 per cent while methane emissions had been slashed by around 56 per cent.”

Sadly, however, as scientists also warned, the changes — described by the Guardian as the “sharpest drop in carbon output since records began” — will swiftly be undone without further concerted political action. As the Guardian noted, “As countries slowly get back to normal activity, over the course of the year the annual decline is likely to be only about 7%, if some restrictions to halt the virus remain in place [and] if they are lifted in mid-June the fall for the year is likely to be only 4%.”

The Guardian added that this “would still represent the biggest annual drop in emissions since the second world war, and a stark difference compared with recent trends, as emissions have been rising by about 1% annually”, but, according to Corinne Le Quéré, a professor of climate change at the University of East Anglia, and the lead author of the study recording the fall in global carbon emissions, which was published in Nature, it would make “a negligible impact on the Paris agreement” goals of keeping the increase in global average temperature to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels to prevent the onset of catastrophic climate change.

In London, after the lockdown was declared on March 23, the majority of the capital’s heavily polluting construction sites — contributing significantly to the level of emissions — shut down, although in some cases only as a result of criticism (for one example, see the ‘Shut the Sites‘ campaign).

The result was inspiring, as the city fell silent, and the roads were almost entirely empty, because, before the coronavirus hit, London’s roads were almost permanently choked with traffic, creating homicidal levels of air pollution.

In addition, the city, as a whole, had for many years been at war, invaded by an enemy that most people didn’t even recognise: the global corporate construction industry, involved in the creation of huge numbers of new housing, office and retail developments — often through “mixed use” developments that combin all three, and that, as noted above, also contributed massively to air pollution.

These huge developments purport to be beneficial to Londoners, but the housing is way beyond the reach of ordinary hard-working Londoners, and is intended primarily for foreign investors, and the entire programme is actually only a means for parasitical transnational investment entities to take over prime inner city real estate, and to hire the bloated egos of superstar architects to design these monstrous new developments.

The results — some completed, but many others only partly completed — are now scattered across London, with particular concentrations at Nine Elms in Vauxhall and Battersea, in Canary Wharf and in the City of London, but with other examples springing up in almost every borough.

A key component in this land grab has been developments involving so-called “social housing”, whereby, in general, housing associations, which trade on their reputation as kindly providers of affordable housing for poorer workers, have hooked up with the same parasitical transnational investment entities, with the full support of central and local government, to create new housing developments.

These often involve the demolition of existing — and, crucially, structurally sound — council estates, which are replaced, primarily, with properties for private sale, along with two other scams: “affordable” housing that is much less affordable than the housing it replaces, and “shared ownership”, in which people buy a share of a property (say, 25%), and pay rent on the rest (as well as unregulated and often grossly inflated service charges), but are only secure tenants until they own the property 100%, and stand to lose everything if they fall into arrears.

After the lockdown began, and the sites that had initially stayed open were pressurised to shut, I was relieved to discover very few sites open on my daily bikes rides around London, to take photos for my ongoing photo-journalism project, ‘The State of London.’ The whole of Nine Elms went quiet, as did most of the sites at Canary Wharf and the City, although a noticeable exception was at 40 Leadenhall Street, where work clearing the ground for a proposed £1.4 billion, 900,000 sq. ft. development, nicknamed ‘Gotham City’, continued as though there was going to be some sort of demand for it when the worst of the crisis is over — which it clearly isn’t yet, despite the government’s false and cynical optimism about nudging us towards a return to “business as usual.”

Another notable exception was on the Aylesbury Estate, in Walworth, in south east London, where demolition contractors continued to demolish Chiltern House, one of the great concrete housing blocks on what was once one of Europe’s largest housing estates, an act of double vandalism — both socially, because of its intent to socially cleanse the area of its poorer inhabitants, and, environmentally, because, as the academics Mike Kane and Ron Yee have demonstrated, “The carbon cost of constructing this building was extremely high. The reinforced concrete structural frame (excluding partition walls and internal elements) is estimated to weigh in excess of 20,000 tonnes which equates to approx. 1,800 tonnes of emitted CO2 for the concrete alone. This figure is significantly increased with the remainder of the construction process and transport emissions. Demolition of Chiltern House requires in the region of 800+ HGV truck journeys through London’s congested streets, and the use of heavy demolition machinery will greatly add to the figure again. Clearly, the CO2 emission cost of reaching just the cleared site (after only 40 years of housing use) is very high, moreover, if the replacement building is of conventional construction (with only 30 year warranty), then the overall environmental cost of providing additional homes is enormous.”

Since last week, however, when Boris Johnson suggested that everyone who could return to work should do so, sites have been reopening. Most of Nine Elms is still quiet, but work has resumed on the biggest project of all, Battersea Power Station, and other sites are also starting up again.

Inside the massive and soulless Battersea Power Station development on April 16, 2020 (Photo: Andy Worthington).

Inside the massive and soulless Battersea Power Station development on April 16, 2020 (Photo: Andy Worthington).This is a great shame, because, to anyone paying attention, the construction industry was already a “zombie” industry before the coronavirus hit, in part because of the cumulative damage caused by its remorseless greed, and in part because of the Tories’ obsession with fulfilling the morbidly flawed EU referendum in June 2016, whose sole purpose, in terms of Britain’s international business prospects, appears to have been to turn us from a “safe pair of hands” into an untrustworthy basket case.

The entire parasitic global construction industry assumed its current prominence after the global economic crash of 2008, which was, of course, caused by criminally greedy investment bankers who were not subsequently punished. After their sub-prime mortgage scam unravelled so spectacularly, their attention soon turned to these new developments that plague not only London but also any other city whose elected leaders can be manipulated by false promises of unparalleled wealth creation, exciting new “communities” and job opportunities — fables that some politicians actually seem to believe, while others merely embrace them cynically.

The reality, as was revealed in a Guardian exposé two years ago, entitled, ‘Ghost towers: half of new-build luxury London flats fail to sell’, is that “[m]ore than half of the 1,900 ultra-luxury apartments” built in London in 2017 had “failed to sell.” Henry Pryor, a property buying agent, frankly told the Guardian that the London luxury new-build market was “already overstuffed but we’re just building more of them.” He added, “We’re going to have loads of empty and part-built posh ghost towers. They were built as gambling chips for rich overseas investors, but they are no longer interested in the London casino and have moved on.” He also pointed out that the developers had “failed to sell homes despite offering discounts, incentives and freebies – including free furniture, carpets and curtains and even cars”, because, while they offered “luxuries including concierge, gyms and spas”, fundamentally “they’re all the same” — and over-priced.

The same is true of the office blocks being built, for which no market seemed to exist even before the coronavirus hit — and which may become substantially less popular in the post-virus world. In an article on May 1, entitled ‘The end of the office? Coronavirus may change work forever’, the FT noted that, “Facing a sudden need to cut costs, chief executives have indicated in recent days that their property portfolios look like good places to start given the ease with which their companies have adapted to remote set-ups.”

Jes Staley of Barclays said, “The notion of putting 7,000 people in a building may be a thing of the past.” Dirk van de Put of Mondelez said, “Maybe we don’t need all the offices that we currently have around the world”, while Sergio Ermotti of UBS said they were “already thinking about moving out of expensive city centre offices.”

Let’s hope that this really is the end for this zombie business of hideously overpriced housing and offices, and the relentless shops that accompany them — trying, it seems, to make sure that we can’t walk more than a few feet without spending money.

What we’re going to need when we come out of this crisis is genuinely affordable housing, at social rents (think £50 per adult per week) to support all those people who, even before the crisis hit, were clinging on by their fingernails while the frantic world that collapsed two months ago was still engaged in what we all seemed to regard as an endless party, but one in which we were not encouraged to ask too many questions about who was being exploited, and how fundamentally, terrifyingly unsustainable it all was.

* * * * *

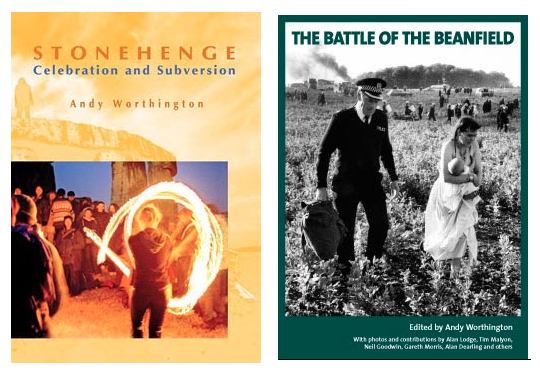

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 18, 2020

“The Use of Power and Ideology in Guantánamo”: New Academic Paper Focuses On My Book “The Guantánamo Files”

The cover of Andy Worthington’s 2007 book “The Guantánamo Files.”

The cover of Andy Worthington’s 2007 book “The Guantánamo Files.”Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

Imagine my surprise last week when a post popped up on Facebook, which I was tagged in, that read, “The Use of Power and Ideology in Guantánamo: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Andy Worthington’s The Guantánamo Files.”

Clicking through, I found that it was an entire academic article focusing on my 2007 book The Guantánamo Files, published in the latest issue (June 2020) of the European Journal of English Language and Literature Studies, a publication by EA Journals (European-American Journals), part of the UK-based European Centre for Research Training and Development, which is “an independent organisation run by scholars mainly in the UK, USA, and Canada.”

Written and supported by students and supervisors at GC University, in Faisalabad, Pakistan, the abstract explains that “[t]he research deals with the use of power and ideology in Andy Worthington’s The Guantánamo Files (2007) as the narratives (generally called Gitmo narratives) of the detainees show the betrayal of American ideals, [the] US constitution and international laws about human rights. Since its inception, Guantánamo Bay Camp is an icon of American military power, hegemony and legal exceptionalism in the ‘Global War on Terror.’”

As the article proceeds to explain, “There are a number of stories available about what happened to the inhabitants of the Guantánamo Bay Detention Camps in the form of books, articles, news and online stuff. These narratives are told and retold by many authors with multi perspective approach, but Andy Worthington’s The Guantánamo Files is one of the most prominent works of Gitmo narratives covering all issues of the topic. The goal of this work is to highlight the dark and unknown secrets of the detainees’ lives inside Gitmo and to know what is happened to the detainees in Guantánamo and why they are inside this limbo.”

The article also states, “For the first four years only the top American officials knew the exact number and names of the detainees. It was almost impossible to recount the stories of these male Muslims as they were detained without any charge or trial and they had no contact with their families. They were unable to make any contact even to their lawyers in the beginning and they were simply the apparatus of a lawless experiment conducted in the Torture Lab of America in the remote area of Cuba outside the jurisdiction of American law.”

Furthermore, the article adds, “Guantánamo, in terms of Foucault [“Discipline and Punish” (1979)], saw a new theory of law and crime. It was a new moral or political justification of the right to punish. Old laws were eliminated and old customs died out in Guantánamo. The working of military tribunals was also illegal and deeply flawed. The prisoners were not allowed to have any legal representation, and were stopped from seeing the classified evidence against them. The evidence often consisted of allegations based on unconfirmed reports or torture.”

The main body of the article subjects the stories of Abu Zubaydah, Mohamedou Ould Slahi and Mohammed Al-Qahtani, as discussed in my book, to “critical discourse analysis,” concluding, through examining these three stories of particularly abused individuals, that Guantánamo stands as “a symbol of civilizational breakdown through self-serving and pre-planned power abuse.”

My thanks to Ph.D. scholar Ahmad Saeed Iqbal, Assistant Professor Dr. Muhammad Asif and Visiting Lecturer Muhammad Asif Asghar for this article. It’s reassuring that this work I undertook so many years ago continues to have resonance around the world.

To buy The Guantánamo Files as an e-book or paperback, please see the Pluto Press page here.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 14, 2020

Landlords: The Front Line of Coronavirus Greed

End rent now: a protestor in Los Angeles.

End rent now: a protestor in Los Angeles.Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

As the coronavirus continues to cripple the economy, it is clear to anyone paying attention — a situation not encouraged by either our political leaders or the mainstream media — that its disastrous effects are extremely unevenly distributed.

While some people are working from home on 100% pay, others — the essential workers of the NHS, pharmacists, those in the food industry, postal workers and other delivery people, public transport workers, and many others — have continued to work, often at severe risk to their health, because of the government’s inability to provide proper PPE or a coherent testing system. Other workers, meanwhile, have been furloughed on 80% of pay (up to £2,500 a month), while another huge group of former workers have been summarily laid off, and have been required to apply for Universal Credit, a humiliating process that also involves the requirement to try to survive on less than £100 a week.

While those on Universal Credit receive support in paying their rent, and one of the government’s first moves, when the lockdown began, was to secure mortgage holidays for homeowners, no such support exists elsewhere in the economy for those who are renting. This is a disaster both for businesses and for those living in properties owned by landlords and not receiving housing benefit, as there has been no suggestion from the government, at any time over the last seven weeks, that landlords should share everyone else’s pain.

Sadly, this is typical of the way that governments behave, because, for the last 20-odd years, the ownership of property, whether of homes or commercial properties, has conferred on owners the right to participate in a feeding frenzy of greed, and, moreover, to see themselves as both superior and uniquely entitled to make as much money as they can get away with, with little or no thought given to those who are exploited as a result.

The result of this mentality, as the economy has crashed, and millions of people have lost their incomes or seen their incomes cut, and numerous businesses have been forced to shut their doors to the public, is that those struggling to pay for their landlords’ sense of self-entitlement are, in a domestic context, either paying most of their income in rent, or are likely to be made homeless, and, in a business context, are likely to go bust.

It’s possible that there will have to be reckoning when, after the worst of this crisis is over, the streets are full of homeless families, and shops, pubs, restaurants, theatres and offices are all shut and boarded up because no one can actually afford to run businesses any more, but it would be reassuring if there were efforts to prevent this total collapse by reining in the self-entitled greed of landowners, homeowners and landlords sooner rather than later.

Private renters’ woes

On the domestic front, to give you some idea of the extent to which those living in privately rented property are being affected by the combination of the coronavirus and their landlords’ undiminished greed, startling news has emerged via Ome, a company that is trying to rethink rental deposits, about the extent to which suffering workers are still being fleeced by their landlords. The company undertook research into how furloughed workers are coping, and discovered that, prior to the lockdown, the average tenant in the UK “was paying 47% of their monthly net income to cover the cost of renting”, an amount that has increased to 57%, an increase of 10%.

In London, meanwhile, the research revealed that, prior to the lockdown, “rent already accounted for 64% of the average monthly net income”, and that this has increased to 85%, an increase of 21%.

The research also indicated that the highest change in the percentage of income paid in rent was in Kensington and Chelsea, “where a furlough reduction in monthly income means renting now accounts for 152% of the average wage, a huge jump of 94%”. Other shocking increases were noted in “Westminster (+76%), Camden (+52%), Richmond (+43%), Hammersmith and Fulham (+40%) and Wandsworth (+39%)”, with rent “now accounting for upward of 93% of income for those on furlough.”

In order to try to protect renters to some extent, the government sought to prevent evictions for three months when the lockdown started, but that much-trumpeted ban seems, in reality, to have been toothless, as Amelia Gentleman of the Guardian recently exposed shocking stories of hospitality workers in London who were almost immediately made homeless after the lockdown began, because they lost their jobs overnight and then couldn’t pay their rent, and were evicted and are now living on the streets.

Beyond these stories, many evictions have indeed been put on hold, but only for a limited time. As Joe Beswick of the New Economics Foundation pointed out in a Guardian article on May 12, “The suspension is scheduled to end in mid-June, and has not been extended.” Beswick pointed out that “Citizens Advice found last week that 2.6 million private renters have already missed, or expect to miss, a rent payment due to the crisis”, and added:

For thousands of renters who’ve lost their income but are still required to pay rent, eviction could come quickly once the suspension is lifted. In the words of Ghazal, a member of the London Renters Union: “I’ve lost all my work because of the pandemic. My landlord won’t give me a rent reduction and I’m worried that this means I will be forced out.” London Councils, the representative body of the city’s local authorities, has warned of an “avalanche” of evictions coming down the line.

Beswick noted how, last weekend, the Labour party announced a “five-point plan” to protect renters, which “extends the eviction suspension by six months, gives renters two years to pay off any rent arrears built up during the crisis, and asks the government to consider a temporary increase to housing benefit”, but as he explains, “even this is unlikely to be enough, and involves plunging tenants into debt to protect landlords’ income streams.”

As he proceeded to explain, “With the Bank of England contemplating the worst recession in 300 years, renters’ incomes are unlikely to bounce back once lockdown lifts, and the impact of the crisis on people’s ability to pay rent will be here to stay. If we are to protect renters, we need to solve the problem of rent.”

He added, “Under Labour’s plan, a renter who missed three payments of the average monthly rent in England (£867 a month) would find themselves paying £108 extra every month for the next two years”, an extra cost that many renters will be unable to afford. Instead, as NEF has recently proposed, the best answer — indeed, the only way to avoid a potential tsunami of homelessness — “is to temporarily suspend rents.”

For more on the housing rental crisis, see this Independent article about how students are taking on rapacious landlords, who are refusing to write off rents, even for students whose courses have been cancelled, by embarking on rent strikes, a course of action that other renters need to keep a close eye on.

Meltdown in the hospitality sector

In the business sector, meanwhile, the same problem — of landlords seeking to extract money from tenants that they simply don’t have — threatens to wipe out an extraordinary number of businesses unless some sort of enactment of shared pain takes place.

Restaurants have been making this clear since the lockdown began, with award-winning chef Yotam Ottolenghi warning in the Guardian on April 11 that the coronavirus will destroy the UK restaurant industry without assistance — particularly with regard to rents. As he noted:

Thanks to the government-funded furlough scheme, we are fortunate enough to be able to pay our staff while they are at home. There are, however, other serious issues, the most burning of which is rent. Though some landlords have made private arrangements with tenants to forgo rent payments for a certain period, most are demanding their quarterly transfers. For businesses with zero income, this is a kiss of death. Accumulating debt now, when we are not operating, will severely hamper our ability to re-establish businesses that pay salaries, taxes, bills and rents. For many, it will simply mean that they cannot renew trading — this would be a devastating and totally unnecessary outcome. For the lucky ones, it will mean that they hang on by the skin of their teeth, but will not have enough capital to expand and create more jobs, which will be so sorely needed when this crisis is over.

For more on the restaurant crisis, see Jay Rayner’s Observer article, ‘Will Britain’s restaurants survive coronavirus?’ and this article on the ‘Eater London’ website, detailing how a number of restaurant owners have “asked the government to consider a nine-month rent-free period” to save their businesses. Rayner, following up on Ottolenghi’s position, explained how Criterion Capital, “which owns large slabs of property around London’s Leicester Square”, had been threatening Caffe Concerto with a winding up order, because it had not paid rent on one of its sites, and noted that Andrew Sell of Criterion told the FT, “We are driven to take such action because we are a business that has an obligation to our lenders, to collect rent and meet their demands for interest payment to be made on time.” He added that, as he saw it, “The property industry is being treated as the nation’s bank”, which is a very un-generous position.

Kate Nicholls, the chief executive of the industry body UK Hospitality, said that she had “heard repeated stories of restaurant owners facing issues of this sort”, explaining, with some accuracy, “Too many landlords, banks and insurance companies are simply not sharing the pain of this.”

Elsewhere in the hospitality industry, pubs are also facing a bleak future. As the Guardian explained on May 10, “[w]ith only one of the big six landlords cancelling rents”, publicans are fearful about their future.

Already suffering from “ties”, an “ancient but controversial deal under which pubs buy their beer at inflated prices from the business that owns their property”, supposedly in exchange for lower rents, publicans are now finding that “nearly all of the major pub companies have refused to cancel rents, opting to defer their demands or offer a discounted rate instead.”

Edward Anderson, who runs three pubs in Cheltenham, told the Guardian, “It’s just debt that we can’t repay when we reopen.” His landlords had “offered to postpone the rent bill”, but that wasn’t enough. As the Guardian added, “rents are set based on a pub’s ‘fair, maintainable trade’, in other words the turnover it expects to make in a year. But while takings have fallen off a cliff overnight, rent reassessments take place only every five years, meaning that when those rent demands resume, there will be less in the till to honour them with.”

Dave Law, who runs the Eagle Ale House near London’s Clapham Common, told the Guardian, “We need rent to be cancelled during the period. We’re being forced to pay based on turnover that we can’t make because of government decree. Rents are already inflated and when we come out of this, we’re going to be in a recession.” As the Guardian added, “Like Anderson, he fears he won’t be able to recoup his lockdown losses unless pubcos step up and share more of the pain.”

So what does the future hold? Will landlords recognise the scale of the crisis facing their tenants, or will we have to wait until as I suggested above, “the streets are full of homeless families, and shops, pubs, restaurants, theatres and offices are all shut and boarded up because no one can actually afford to run businesses any more”?

I fervently hope not.

Note: For what’s happening in the US, see ‘Cancel the Rent’, a brand-new article in the New Yorker.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 11, 2020

Celebrating Eight Years of My Photo-Journalism Project, ‘The State of London’

Andy Worthington’s most recent photos of London under lockdown, as part of his photo-journalism project ‘The State of London.’

Andy Worthington’s most recent photos of London under lockdown, as part of his photo-journalism project ‘The State of London.’Please feel free to support ‘The State of London’ with a donation. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

Check out all the photos here!

Exactly eight years ago, on May 11, 2012, I set out on my bike, from my home in Brockley, in the London Borough of Lewisham, in south east London, to begin a project of photographing the whole of London — the 120 postcodes that make up what is known as the London postal district or the London postal area (those beginning WC, EC, E, SE, SW, W, NW and W). These postcodes cover 241 square miles, although I’ve also made some forays into the outlying areas that make up Greater London’s larger total of 607 square miles.

I’ve been a cyclist since about the age of four, and I’d started taking photographs when I was teenager, but my cycling had become sporadic, and I hadn’t had a camera for several years until my wife bought me a little Canon — an Ixus 115 HS — for Christmas 2011. That had renewed my interest in photography, and tying that in with cycling seemed like a good idea because I’d been hospitalised in March 2011 after I developed a rare blood disease that manifested itself in two of my toes turning black, and after I’d had my toes saved by wonderful NHS doctors, I’d started piling on the pounds sitting at a computer all day long, continuing the relentless Guantánamo work I’d been undertaking for the previous five years, which, perhaps, had contributed to me getting ill in the first place.

As I started the project, I had no idea really what I was letting myself in for — how massive London is, for example, so that even visiting all 120 of its postcodes would take me over two years, or how completely I would become enthralled by the capital that has been my home since 1985, but that was unknown to me beyond familiar haunts (the West End, obviously, parts of the City, and areas like Notting Hill and Ladbroke Grove, which I’ve always been drawn to), and places I’d lived (primarily, Brixton, Hammersmith, briefly, Forest Hill, Peckham and, for the last 20 years, Brockley).

That first day involved just a short circuit, down through Deptford to the River Thames at Greenwich, but as the weeks passed, I began making longer journeys — to central London through Bermondsey, much of which was unknown to me, along the River Thames from Deptford through Rotherhithe to Tower Bridge and beyond, and through the Greenwich Foot Tunnel, which led to the Thames Path along the northern shore of the Thames, as well as east London’s two major canals — the Regent’s Canal, which loops up through Hackney, Islington and Camden, eventually joining the Grand Union Canal at Little Venice, near Paddington, and the Limehouse Cut, which heads out through Bow, joining the River Lea, and passing through Stratford on its way north via Clapton and Tottenham — all routes that have become staples of my cycling, as well as the south eastern river route, through Greenwich, on to Charlton and Woolwich, and, on occasion, to Thamesmead and beyond. I have also, of course, become very familiar with the entire network of main roads — although I do tend to cycle on back streets as much as possible.

In the first few months, I had to cycle everywhere, rather than hopping on a train with my bike and getting a head start, as I have often done over the years, because it was the run-up to the Olympics, when bikes were banned on trains at all times, and not just, as usual, at rush hour. That led to me getting to know my immediate neighbourhood extremely well, including a variety of routes into central London, but it took until August 2012 before I was able to start ranging across the capital more widely.

As the project developed, I got to know the capital almost as an extension of myself. I revelled in the now-ness of being out in it, in all types of weather, on a bike, enjoying the light, the shadows, the storm clouds, the rain, the changing seasons, and I got to know it in detail, becoming particularly drawn to its council estates, and finding myself wounded by the many forms of desecration visited on the capital — most cynically, in the post-Olympic boom, with Boris Johnson as Mayor, in which ‘luxury’ housing developments, often featuring inappropriate tall towers, were approved everywhere, and through the cynical destruction of council estates for replacement developments that priced out locals, and provided massive profits for private developers.

On the fifth anniversary of that first conscious decision I took, to start chronicling the capital with a camera on a bike, I began publishing a photo a day on a Facebook page, called, unsurprisingly, ‘The State of London’, following up soon after with a Twitter page.

In terms of technology, I have also adapted over the years. 15 months after starting the project, I upgraded to a Canon Powershot SX270 HS, and went through a few of those before finally making a crucial upgrade last February, and buying a Canon Powershot G7 X Mk II, which has changed my life. I now get stunningly sharp images, and a zoom that enables me to take excellent long shots of buildings and streets without any distortion of the parallels — the equivalent of an SLR that I can keep in my pocket!

And while the first 13 months with my G7 X were an adventure in increased self-confidence, as I finally began to feel that I was doing justice to the scope of my project, the last seven weeks have taken it to a new level, as I have been chronicling London under the coronavirus lockdown, which has been an extraordinary experience, revisiting the city I have got to know so well over the last eight years, but finding it — and the West End and the City, in particular — almost entirely deserted, as though some sort of apocalypse has taken place that has rid the capital of all its inhabitants, but has left all the buildings standing.

I’m delighted to note that all of this work was noticed by ‘My London’, a website representing a number of London regional newspapers, which published eight of my photos last week, and I hope very much — although I know I keep saying this — that some sort of book and exhibition will be forthcoming, as well as a website. If you can help with any of this in any way, please do get in touch.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 8, 2020

Lockdown Listening: Radiolab’s Six-Part, Four-Hour Series About Guantánamo Prisoner Abdul Latif Nasser, Cleared for Release But Still Held

An image produced by Will Paybarah for Radiolab’s series “The Other Latif,” about Guantánamo prisoner Abdul Latif Nasser.

An image produced by Will Paybarah for Radiolab’s series “The Other Latif,” about Guantánamo prisoner Abdul Latif Nasser.Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

As the coronavirus continues to impact massively on our lives, via lockdowns and a global death count that has now reached over 250,000, spare a thought for the prisoners at Guantánamo, who are more isolated than ever. Although it is profoundly reassuring that the virus has not reached the prison — despite a US sailor contracting it on the naval base in March — the 40 men still held have not had any contact with anyone other than their captors since the US lockdown began.

Their attorneys are no longer able to fly out to see them, and, last Saturday, Carol Rosenberg of the New York Times tweeted that the International Committee of the Red Cross had “canceled its quarterly visit because of the virus.” As she proceeded to explain, ICRC delegations have been “meeting with the detainees and prison commander since Camp X-Ray opened in 2002,” and the visit on May 22 would have been the ICRC’s 135th visit to the prison.

As the lockdown continues — and so many of us have more time on our hands than previously — now seems like a good opportunity for those of you who are interested in Guantánamo to listen to “The Other Latif,” an unprecedented six-part, four-hour series about one particular prisoner, Abdul Latif Nasser, the last Moroccan national in the prison, whose case we have covered many times over the years — see, for example, Abandoned in Guantánamo: Abdul Latif Nasser, Cleared for Release Three Years Ago, But Still Held, from last August, and Trump’s Personal Prisoners at Guantánamo: The Five Men Cleared for Release But Still Held, from last November.

Of the 40 men still held at Guantánamo, Abdul Latif Nasser is one of the most unfortunate, having been unanimously approved for release in July 2016 by a high-level US government review process, the Periodic Review Boards (PRBs), which was established under President Obama, but not released.

By the time the Moroccan authorities finalized the necessary paperwork and got it back to the US government, President Obama had just 22 days left in office, whereas, for many years, Congress had demanded that 30 days’ notification be given to lawmakers before any prisoner could be released — meaning, as a result, that Nasser missed being released by just eight days.

Donald Trump, of course, has no interest in releasing anyone from Guantánamo under any circumstances, leaving Nasser trapped, along with four other men approved for release but still held when Obama left office, 26 other men appropriately identified by the mainstream media as “forever prisoners,” who were approved for ongoing imprisonment by their PRBs, and just nine men facing, or having faced trials.

“The Other Latif” is the first ever multi-part series produced for Radiolab, part of WNYC Studios, which, in turn, is part of the esteemed New York Public Radio, and the series was inspired by a single tweet seen by Radiolab’s Latif Nasser — a tweet by Reprieve, dated January 19, 2017, which stated, “Read our urgent letter to @POTUS seeking intervention for Abdul Latif Nasser, cleared yet stranded at Guantánamo Bay.”

As the Radiolab website explains, “Latif Nasser always believed his name was unique, singular, completely his own,” until he made “a bizarre and shocking discovery,” that “he shares his name with another man: Abdul Latif Nasser, detainee 244 at Guantánamo Bay.” As the website proceeded to explain, the US government painted “a terrifying picture of The Other Latif as Al-Qaeda’s top explosives expert, and one of the most important advisors to Osama bin Laden.” However, Nasser’s lawyer, Shelby Sullivan Bennis, told Radiolab’s Latif that “he was at the wrong place at the wrong time, and that he was never even in Al-Qaeda.”

In seeking to establish the truth about his namesake, Latif was led “into a years-long investigation, picking apart evidence, attempting to separate fact from fiction, and trying to uncover what this man actually did or didn’t do.”

Some have criticized the end result for its tone. Josephine Livingstone of the New Republic, for example, lamented that Radiolab’s “house podcast style holds back what is otherwise an extraordinary series.” She stated that the series “contains what I can only call some beautiful lines of inquiry,” adding that “Nasser chases the story through sunflower fields in Sudan, through his own uncertain youth, along the halls of Guantánamo Bay itself,” and that “[t]hese investigations throw an unexpected and rather poignant light across the subject matter,” but suggests that “the show is constrained by a few flaws that feel endemic to trends within the medium of podcasting itself, rather than to Nasser’s particular work.”

These flaws involve, primarily, a kind of forced levity that is obviously very much at odds with the seriousness of the subject matter. As Johnstone describes it, Radiolab’s house style, “in this context — a very serious story with tragic consequences — feels like a deliberate signature imposed without concession to the topic.”

That said, she concludes her article by stating, “You’d be hard-pressed to listen to The Other Latif and not learn something, and that seems like success to me” — and there is indeed an extraordinary depth to Latif’s investigation, regardless of how it is often presented. Guantánamo is so rarely covered in depth in the mainstream media, and yet here is a four-hour radio series about a single prisoner in Guantánamo, defying every expectation that, at an editorial meeting, it would have been confined to, at most, a single one-hour show.

Instead, in the first episode, Latif begins to explore who his namesake may be, discussing the alleged evidence with Shelby Sullivan Bennis, and hearing about how he should have been released until Donald Trump happened; in the second episode he travels to Morocco to meet Nasser’s family, who welcome him so thoroughly that he feels his “objectivity” being threatened; in the third episode, he investigates Nasser’s time working on a sunflower farm in Sudan; in the fourth episode, he investigates his time in Afghanistan; in the fifth episode he visits Guantánamo; and in the sixth episode he visits Washington, D.C. to talk to those with knowledge of how and why Nasser was approved for release, but was not actually freed, which the website describes as “a surprisingly riveting story of paperwork, where what’s at stake is not only the fate of one man, but also the soul of America.”

We hope you have time listen to “The Other Latif,” and will share it if you find it useful.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 4, 2020

Radio: I Discuss the Coronavirus Changing the World Irrevocably, Plus Guantánamo and WikiLeaks, with Chris Cook on Gorilla Radio

Andy Worthington calling for the closure of Guantánamo outside the White House on January 11, 2020, the 18th anniversary of the prison’s opening (Photo: Witness Against Torture).

Andy Worthington calling for the closure of Guantánamo outside the White House on January 11, 2020, the 18th anniversary of the prison’s opening (Photo: Witness Against Torture).Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

Last Tuesday, I was delighted to speak to Chris Cook, for his radio show Gorilla Radio, beaming out to the world from Vancouver Island, in western Canada. Our full interview — an hour in total — can be found on Chris’s website. It’s also available here as an MP3, and I hope you have time to listen to it. A shorter version — about 25 minutes in total — will be broadcast in a few weeks’ time.

Chris began by playing an excerpt from the new release by my band The Four Fathers, ‘This Time We Win’, an eco-anthem inspired by the campaigning work of Greta Thunberg and Extinction Rebellion.

We then discussed my most recent articles about Guantánamo, A Coronavirus Lament by Guantánamo Prisoner Asadullah Haroon Gul and Asadullah Haroon Gul, a “No-Value Detainee,” and One of the Last Two Afghans in Guantánamo, Asks to Be Freed, both dealing with one of the many insignificant prisoners still held at Guantánamo, out of the 40 men still held — Asadullah Haroon Gul, whose lawyers are trying to secure his repatriation as part of the Afghan peace process.

13 minutes into the interview, Chris asked me to discuss my recent article, Nine Years Ago, Julian Assange and WikiLeaks Released the Guantánamo Files, Which Should Have Led to the Prison’s Closure, which I was happy to do, because I worked with WikiLeaks as a media partner for the release of classified military files relating to the Guantánamo prisoners in April 2011, and I’m appreciative of every opportunity to point out that the information contained in the files — about patently false, or otherwise unreliable statements made by the prisoners, about their fellow prisoners, often through the use of torture or other forms of abuse — destroys whatever shallow reasons the US government has cobbled together over the years to justify the prison’s ongoing existence.

19 minutes into our interview, we began discussing the coronavirus, with particular reference to my article, The Coronavirus Lockdown, Hidden Suffering, and Delusions of a Rosy Future. I castigated the Tory government, headed by Boris Johnson, for their failure to take the virus seriously back in February and March, noting a dreadful TV interview in which Johnson spoke about the government’s preferred “herd immunity” option, involving people, as he put it, “taking it on the chin”, and allowing the virus to pass through the population. It was, as I explained, actually “a recipe for maximum slaughter.”

I also spoke about how difficult it is, right now, to know what the future holds, given that so much “business as usual” has shut down, although I did note some positives: the revelation that key workers are actually the most important people in society, how many people are suddenly thinking about what life means, and are more relaxed now that the insane consumerist treadmill has, at least temporarily, come to an end, and how, for once, the sky in London — and other major cities — is clean.

Unfortunately, as I also noted, it’s also of great relevance that millions of people who were working — many in the entertainment and hospitality sectors — suddenly have no money, and are dependant for their survival on a lumbering and long-undermined welfare system. I also spoke about a particular problem that isn’t being discussed enough — involving rents, both in a domestic context, and also in relation to businesses, noting that the shutdown is a nightmare for the many independent businesses who had been clinging on by their fingernails before the virus hit, and are in no position to defer their rents, to be paid back later.

At this point, the interview that will be broadcast came to an end, but Chris and I continued talking for another 35 minutes, for the longer version linked to above, which took in all manner of other aspects of the coronavirus story: the British effort to frame it within a “plucky” wartime context, the role of Brexit, Britain’s ideological civil war, and fears of governments — not just the British — using the crisis as an opportunity for increased authoritarianism.

I also spoke about how important I think it is for us to think about and talk about the massive changes the coronavirus crisis has brought, which are not, in general, being covered in the mainstream media, and expressed my hope that what passed for our culture before the crisis — which seemed to be based on becoming “crazier, faster, angrier, more stupid, using up more and more of what we only have finite amounts of” — might finally be brought to to an end, as I discussed in my article, Health Not Wealth: The World-Changing Lessons of the Coronavirus — although it may be that this “opportunity to rein in our most suicidal stupidity”, as I put it, will be missed.

44 minutes in, Chris asked me about my photo-journalism project, ‘The State of London’, which gave me an opportunity to talk about my eight-year project of cycling around London’s 120 postcodes, taking photos, and how I have been responding to the coronavirus crisis, still cycling around taking photos, and being particularly drawn to the City and the West End (London’s banking centre and its main shopping and entertainment district), which have almost entirely shut down over the last six weeks, and are empty in a way that no one has ever seen before.

An empty Regent Street on April 17, 2020, photographed as part of Andy’s ongoing photo-journalism project, ‘The State of London.’

An empty Regent Street on April 17, 2020, photographed as part of Andy’s ongoing photo-journalism project, ‘The State of London.’There is much more in the interview than I’ve managed to discuss above, so I hope that, if it sounds interesting, you’ll check it out, and will share it if you find it useful.

To reiterate: we need to think about and talk about this crisis, and what it means, and not leave that to our politicians and our mainstream media to resolve, because, for a variety of reasons, they are not necessarily trustworthy or reliable. “Business as usual” may be difficult to restore, but that isn’t going to stop the money people from trying to press the re-set button, and those of us who, in particular, realise that we were already accelerating towards extinction even before the virus hit need to be ready to argue for and agitate for a better world when we come out of this.

Thanks for listening!

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from seven years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

April 29, 2020

Change the World! A Life in Activism: I Discuss Stonehenge, the Beanfield, Guantánamo and Environmental Protest with Alan Dearling

Andy Worthington calling for the closure of the prison at Guantánamo Bay outside the White House, singing and playing guitar, and challenging the police and bailiffs on the day of the eviction of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford.

Andy Worthington calling for the closure of the prison at Guantánamo Bay outside the White House, singing and playing guitar, and challenging the police and bailiffs on the day of the eviction of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford.Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

At the start of the year, I was delighted to be asked by an old friend and colleague, Alan Dearling, the publisher of my second book, The Battle of the Beanfield, if I’d like to be interviewed about my history of activism for two publications he’s involved with — the music and counter-culture magazine Gonzo Weekly and International Times, the online revival of the famous counter-cultural magazine of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

In February, after my time- and attention-consuming annual visit to the US to call for the closure of the prison at Guantánamo Bay on the anniversary of its opening, I found the time to give Alan’s questions the attention they deserved, and the interview was finally published on the International Times website on March 21, just two days before the coronavirus lockdown began, changing all our lives, possibly forever. Last week, it was also published in Gonzo Weekly (#387/8, pp. 73-84), and I’m pleased to now be making it available to readers here on my website.

In a wide-ranging interview, Alan asked me about my involvement with the British counter-culture in the ’80s and ‘90s, which eventually led to me writing my first two books, Stonehenge: Celebration & Subversion, and, as noted above, The Battle of the Beanfield. my work on behalf of the prisoners in Guantánamo Bay, which has dominated much of my life for the last 14 years, and my more recent work as a housing activist — with a brief mention also of my photo-journalism project, ‘The State of London’, and my music with The Four Fathers.

I hope you have time to read the interview, and, while I’m acutely conscious that it doesn’t address the massively changed post-coronavirus world, you can find my reflections on life right now in my articles, Imagining a Post-Coronavirus World: Ending Ravenous Capitalism and Our Consumer-Driven Promiscuity, Health Not Wealth: The World-Changing Lessons of the Coronavirus, The Coronavirus Lockdown, Hidden Suffering, and Delusions of a Rosy Future and In the Midst of the Coronavirus Lockdown, Environmental Lessons from Extinction Rebellion, One Year On

Change the World! A Life in Activism with Andy Worthington

Alan Dearling: Always good to share some time with you, Andy. Our paths have kept on criss-crossing since back in the 1990s, possibly the late ’80s. Firstly, it was around your research for your Stonehenge book. I’d been working with a number of new Travellers, especially Fiona Earle and folk involved with the School Bus – the Travellers’ School Charity. What do you remember from those times?

Andy Worthington: I’d first come across the traveller community via the Stonehenge Free Festival, which I visited in 1983 and ’84, when I was a student. At the end of 1985 I moved to London – to Brixton, to be exact – and while I retained my interest in free festivals and the travellers’ movement, I was more generally caught up in living in Brixton in the Thatcher era – lots of squats, great local bands.

However, in 1987/88, when I was living on the hard-to-let Loughborough Estate, the first move towards the privatisation of social housing took place, via Housing Action Trusts (HATs). At six locations across the UK, including the Loughborough Estate and the neighbouring Angell Town Estate, Thatcher proposed taking estates out of council control, handing them over to her cronies to do up, and then renting them back to tenants – presumably, of course, at hugely inflated prices. The struggle against HATs came to dominate my life at that time, but I’m pleased to report that the Brixton HAT was seen off, particularly via the largely black community of Angell Town, led by a formidable organiser, Dora Boatemah.

Alan Dearling: What about your life before your Stonehenge book? Had you been much involved with the squatting and protest scene, particularly the anti-roads movement?

Andy Worthington: Yes, there was a pretty big squatting scene in Brixton when I moved there, and protest was also a part of life under Thatcher – I’m thinking the anti-apartheid protests, when Thatcher massively mobilised the police to protect the South African Embassy in Trafalgar Square, and, of course, the Poll Tax Riot in 1990. In 1991, I became involved in the rave scene, and was at the Castlemorton Free Festival in May 1992, and I also got involved in Reclaim the Streets, when it started in Camden, and also at subsequent events, like the occupation of the M41. I also got involved in protests against the Criminal Justice Act, the clampdown on our freedoms that followed Castlemorton, just as there had been a clampdown on our freedoms in the Public Order Act of 1986 that followed the Battle of the Beanfield in June 1985, when 1,400 police from six counties and the MoD had violently decommissioned a convoy of travellers en route to Stonehenge to set up what would have been the 12th annual Stonehenge Free Festival.

An aerial view of the Stonehenge Free Festival in 1984, as photographed from a police helicopter, and ‘liberated’ from the police at the 1991 Beanfield trial.

An aerial view of the Stonehenge Free Festival in 1984, as photographed from a police helicopter, and ‘liberated’ from the police at the 1991 Beanfield trial.Alan Dearling: Your Stonehenge book brought together many examples of the importance of Stonehenge in ‘celebrations and rituals’ right through to the anarchic festies and parties of the ’70s and ’80s. Can you describe some of the lasting highlights of that book?

Andy Worthington: I love the British counter-culture, Alan, which was much more a thing of the ’70s than the ’60s, as pranksters like Bill ‘Ubi’ Dwyer and Wally Hope, who set up the Windsor and Stonehenge Free Festivals, sought to undermine ‘straight’ materialistic society, and to create alternative lifestyles, and it was great to chronicle these developments, and the development of traveller culture, from the early ’70s to the Battle of the Beanfield. Then, of course, just when Thatcher thought she had won, the rave scene and the road protest movement came out of nowhere to undermine her, and it was also exhilarating to chronicle those more recent events. Sadly, though, I have to say that, although I was pleased to also write about the long legal struggle to secure access to Stonehenge, in terms of a sustained counter-culture, the 21st century is far too readily recognisable as a period in which dull materialism has been dominant.

Alan Dearling: Did the Stonehenge book directly lead you onto the ‘Battle of the Beanfield’ book, which I helped contribute to and published through Enabler Publications?

Andy Worthington: Yes, I had become friends with Neil Goodwin, who co-directed the Beanfield documentary ‘Operation Solstice‘, and in fact had launched my Stonehenge book in June 2004 at the 491 Gallery in Leytonstone, where he lived, which was the last surviving outpost of the concerted resistance to the expansion of the M11 Link Road in the ’90s.