Andy Worthington's Blog, page 130

September 26, 2013

Is the Tide Turning Against the Tories, as Labour Pledges to Scrap the Bedroom Tax and Sack Atos?

Ever since the Tory-led coalition government got into power and ministers made it clear that they were seeking to do as much damage as possible to the poor, the ill, the unemployed and the disabled, and to dismantle, if possible, every state-owned enterprise, and anything that expresses some notion of communality and doesn’t involve naked profiteering, misery and uncertainty have been on the rise, and with good reason.

Ever since the Tory-led coalition government got into power and ministers made it clear that they were seeking to do as much damage as possible to the poor, the ill, the unemployed and the disabled, and to dismantle, if possible, every state-owned enterprise, and anything that expresses some notion of communality and doesn’t involve naked profiteering, misery and uncertainty have been on the rise, and with good reason.

As I have stated in numerous articles over the last few years, the assault on the unemployed and disabled has been particularly heart-wrenching, as the Tories, their spin doctors, their Lib Dem accomplices and their cheerleaders in the mainstream media have portrayed the unemployed as skivers, despite there being only one job available for every five of the country’s 2.5 million unemployed, and have portrayed disabled people with similar flint-hearted distortions.

As a result, wave after wave of vile policies have been introduced with very little outrage from people who probably don’t regard themselves as particularly cruel or heartless — the reviews for the disabled, run by Atos Healthcare, which are designed to find people with severe mental and physical disabilities fit for work, so that their benefits can be cut; the workfare programs for the unemployed that are akin to slavery and allow well-off companies to fundamentally undermine the minimum wage; and the overall benefit cap, the most popular policy in this new Cruel Britannia, according to a YouGov poll in April, in which 79 per cent of people, including 71 per cent of Labour voters, supported it. This is forcing tens of thousands of families to uproot themselves — with all the attendant social costs, particularly for their children — and move to cheaper places, which tend to be those with high unemployment, creating ghettoes, as part of a disgraceful process of social cleansing.

All along, there has been very little scrutiny of the true costs of welfare and the lies being told to implement the policies outlined above — to cite just three examples, the fact that the ballooning housing benefit bill is the fault not of tenants but of greedy landlords, unfettered by any legislation whatsoever, operating with impunity in a bubble maintained by central government and the Bank of England, through artificially low interest rates; the fact that it constitutes just two and a half percent of the government’s welfare spending, as this graph shows; and the fact that much of the government’s welfare payments are to people who are working, but are not paid enough to live on by their employers.

The last 40 months, since the coalition government began its poisonous work, have been so morally and ethically dark that it is easy to be profoundly pessimistic about the future, especially as the talk of scroungers and skivers is so prevalent, and so virulent. It is sometimes hard to remember that the downturn after the financial crash in 2008, which followed a decade-long, delirious housing boom that first saw smug, self-seeking materialism embedded as the nation’s primary characteristic, was the fault not of the poor, the ill, the unemployed and the disabled, but of the opposite — the super-rich and their facilitators, global pirates working in the financial sector, fully backed up by governments, whose crimes were on an almost unthinkable scale, and who, in a surreal twist that I find almost inconceivable, were bailed out and almost entirely let off the hook, and are back making fortunes in a lawless, parasitic, almost inestimably greedy line of work that has been neither punished nor reformed.

This is clearly the big problem still, the elephant in the room that, if left unchecked, will, the next time, finish the hubristic job of global destruction that last manifested itself in 2008, but instead of seeing this, most people, it seems, have been looking down rather than up, peering through the curtains at their neighbours, and obsessing about skivers and scroungers, people without work in a workless world, disabled people and immigrants.

A glimmer of hope: an end to the bedroom tax?

Despite the inevitability of pessimism, it seems that there may be a glimmer of hope on the horizon. As part of its all-embracing mission to hit the poor and to dehumanise them, the Tories decided to punish unemployed people living in social housing who had a spare room, with a bedroom tax — or as they wanted it called, an ‘under occupancy’ charge, whereby, as a horribly cheery leaflet produced by the government explained, “If you have one ‘spare’ bedroom your housing benefit will be cut by 14 per cent of your full weekly rent. If you have two or more spare bedrooms, you will lose 25 per cent.”

They didn’t care that this might look a bit cruel coming from a cabinet of millionaires who might not even know how many spare rooms they had; nor did they stop to listen to those with knowledge of the housing sector who told them that there were very few smaller properties for people to move to, and that it would end up costing more as people would have to downsize to non-existent properties, and would then have to be rehoused in the private sector, which would cost more.

They also didn’t care that some experts told them that they were punishing tenants for an under-investment in social housing that began with Margaret Thatcher’s great council house sell-off, when she prevented councils from building new homes — a policy, incidentally, that has been maintained ever since by Tory and Labour governments alike — and nor did they care, as I have been saying from the moment they made it clear that they want to get rid of social housing, abort tenancies, and drive up rents to whatever the market will bear, that people in social housing are human beings, the same as them, and have the right to regard their homes as homes.

However, while it would be an exaggeration to call the bedroom tax Cameron and Osborne’s poll tax — the single flat rate tax on every adult, regardless of income, that was introduced by Margaret Thatcher, and helped lead to her downfall when it met with widespread and sometimes violent protest — it has succeeded in doing what few of the Tories’ other heartless measures have done and that is to create a growing feeling that it is unjust.

One sign of this was the criticism by Raquel Rolnik, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on housing, who called for the bedroom tax to be scrapped after a recent fact-finding mission (and the Tories’ unpleasant response only made matters worse for all but the most rabid Little Englanders). As the Guardian explained in an editorial last Thursday:

Anyone who remembers the poll tax knows that some policies are so misconceived, and express so exactly the central criticism of the government that introduced them, that they become the token by which they are judged. The bedroom tax – an unjust attack on some of the most vulnerable in society – is well on the way to becoming the coalition’s poll tax. Two different surveys this week have confirmed that as many as half of all families who have lost some housing benefit – about £12 a week – because they have a spare room are now in arrears.

Last Wednesday, the Guardian reported that over half of families subjected to the bedroom tax had been pushed into debt since the policy was introduced at the start of April, and that the country’s largest housing groups were calling for it to be scrapped. As the paper reported:

The National Housing Federation, which represents housing associations, said a survey of 51 of its biggest members found more than half of their residents affected by the bedroom tax – 32,432 people – could not pay their rent between April and June. The survey shows a quarter of those affected by the tax had fallen behind with their rent for the first time ever.

At the National Housing Federation’s national conference on Thursday, David Orr, the chairman, was planning to point out that “over 330,000 households [were] already struggling to pay their rent and facing a frightening and uncertain future.” That is half of the 660,000 or so claimants of working age affected by the bedroom tax, of whom, as the Guardian also reported, 420,000 (63%) are disabled.

David Orr also stressed that ministers had “miscalculated the number of homes available for tenants to downsize into.” As the Guardian described it, “Although 180,000 households were ‘under-occupying’ two bedroom homes … only 85,000 one-bed homes became available in 2012.”

Orr was also planning to tell his conference, “Housing associations are working flat-out to help their tenants cope with the changes, but they can’t magic one-bedroom houses out of thin air. People are trapped. What more proof do politicians need that the bedroom tax is an unfair, ill-planned disaster that is hurting our poorest families? There is no other option but to repeal.”

The Independent also reported that there were at least 50,000 other families who have fallen behind on their rent and who face eviction. The paper stated: “Figures provided by 114 local authorities across Britain after Freedom of Information (FoI) requests by the campaign group False Economy show the impact of the bedroom tax over its first four months. The total number of affected council tenants across Britain is likely to be much higher than the 50,000 recorded in the sample of local authorities that responded to the FoI.”

That makes a total of at least 80,000 people, and, in its editorial last Thursday, the Guardian also noted that the crisis was so severe that housing associations were “recruiting extra bailiffs and setting aside large contingency funds to meet the costs of arrears and evictions.” False Economy noted that “only 16 of the 114 local authorities who responded to the FoI request have a ‘no-eviction’ policy, meaning many thousands of families risk losing their homes as a result of the bedroom tax,” as the Independent described it.

The Guardian editorial added, “It may be reasonable for Labour to be cautious about making spending commitments when the election is still 18 months away, but this is a policy unravelling, at huge cost to individuals and to councils, before our eyes.”

The Guardian proceeded to note that, although the bedroom tax was intended to reduce the £22bn housing benefit bill by about £500m a year, through moving “the 650,000 or so housing benefit recipients in homes too big for their needs to somewhere smaller”:

[N]o one in Whitehall seems to have understood how one of their bright ideas would work on the ground. Households are not all the same. Some people do have more space than they need. Many others turn out to need it – families with caring needs, split families, families providing (free) essential support for children or parents with troubles of their own. And if that wasn’t the case, in many areas – especially in the north of England – councils have a long tradition of regarding a spare room as part of living decently. Many families have one, and there are not nearly enough smaller homes for them all to move into. And, since private rents have risen so much faster than social rents, if they move into the private sector, the housing benefit bill will surely rise.

The Guardian also mentioned “new evidence that as real living standards are squeezed, voters are becoming more sympathetic to people who rely on benefits,” as discovered in the annual British social attitudes survey, and hinted that now would be a good time for the Labour Party to promise to scrap it.

And that was indeed what happened. As the Independent reported on Saturday, in a keynote announcement at the start of the Labour Party Conference in Brighton, Ed Miliband “pledged to abolish the Coalition’s ‘vicious and iniquitous bedroom tax’ if Labour is returned to power at the next election.”

He added that Labour “would make up for the £470m the spare room subsidy is meant to save by reversing some of the Government’s tax cuts for businesses and George Osborne’s ‘shares for rights’ scheme,” and the party was evidently buoyed into action by a survey indicating that “nearly 60 per cent of people believe the policy should be abandoned entirely” – and the support for its abolition from the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, who pointed out that it “was likely to mean a rise in debts to housing associations.”

He said, “When a series of other things are combined, notably reductions in benefit to take account of what is seen as excess house space – the so-called bedroom tax – higher costs for energy, and for many the fact that short-term lenders can take money direct from an account within hours of it coming in, suddenly the problem and possibility of growing a large-scale arrears becomes very serious.”

The end of the line for Atos?

In another sign that the tide may be turning against callousness, Labour also promised to sack Atos Healthcare, the much-criticized corporation that runs the Work Capability Assessments designed to find disabled people fit for work.

As the Guardian reported at the weekend, Liam Byrne, the shadow work and pensions secretary, was set to announce at the Labour Party Conference that ministers “will legislate to introduce a specific criminal charge of disability hate crime amid growing evidence that victims are being let down,” and that he intends to sack Atos. As the Guardian noted, “Two in five assessments are appealed against and 42% of those are successful. The company has also consistently failed to meet targets on average case clearance times since mid-2011, with 35,000 claimants having to wait longer than 13 weeks to receive their decision.”

For his speech, Byrne wrote, “Like most families in this country, I know first-hand that disability can affect anyone. Therefore it affects us all. Someone is registered disabled every three minutes. Yet today disabled people are threatened by a vicious combination of hate crime, Atos and the bedroom tax. Today we deny disabled people peace of mind, a job, a home and care. We need to change this.”

The news on Atos is not quite as hopeful as the bedroom tax plans, as the BBC reported that Byrne also stated, “We need a system that delivers the right help to the right people, so assessments have to stay.” On that front, Labour will have to demonstrate that they can genuinely reform a system that is manifestly cruel, and not just replace one unprincipled, multinational, tax-gobbling corporation with another that will be just as heartless as Atos. The entire system needs to be scrapped and rethought, so that disabled people are no longer subjected to reviews that are the equivalent of a legal system that presumes everyone guilty until proven innocent, and so that those with long-term and incurable or degenerative disabilities — whether physical, mental or both — are exempt from review altogether, instead of being called back again and again, as is the case at present.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

September 25, 2013

Nothing to Celebrate Four Months After Obama’s Promise to Resume Releasing Cleared Prisoners from Guantánamo

[image error]I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us – just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email. Please also visit, like, share and tweet the GTMO Clock website, which we established in July to monitor how long it has been since President Obama promised to resume releasing cleared prisoners from Guantánamo, and how many of those men have been released.

Four months ago, on May 23, President Obama delivered a major speech on national security issues, in which he promised to resume releasing cleared prisoners from Guantánamo. At the time, of the remaining 166 prisoners, 86 had been cleared for release in January 2010 by an inter-agency task force of officials from the major government departments and the intelligence agencies, which the president had established shortly after taking office in January 2009.

These men were still held for a variety of reasons. One reason was the onerous restrictions imposed by Congress, where lawmakers sought to prevent the release of prisoners under any circumstances, insisting that the defense secretary would have to certify that any prisoner he sought to release would be unable to engage in terrorism in the future. Another reason was a ban on releasing cleared Yemeni prisoners, who comprise 56 of those cleared for release but still held, which President Obama imposed in January 2010, after a failed airline bomb plot that was hatched in Yemen.

On May 23, while promising to resume releasing prisoners, President Obama also dropped his ban on releasing any of the cleared Yemenis, but since then no Yemenis have been freed, and just two prisoners out of the 86 — both Algerians — have been released, after the administration made the necessary certifications to Congress.

The great irony, four months since President Obama’s promise to resume releasing prisoners, is that the president only made this promise because he had been provoked into action by the prisoners themselves. In February, in despair at ever being released, or being granted any form of recognizable justice, the majority of the prisoners embarked on a prison-wide hunger strike, which drew the attention of the world’s media, the outrage of NGOs and medical professionals, and public criticism of the prison’s ongoing existence by high-level Democrats — in particular, Sen. Carl Levin, the chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

And yet, despite this, and despite the fact that only two prisoners have been released, and 84 cleared men still await release, the news from the Pentagon this week is that the hunger strike is “largely over,” as the New York Times described it yesterday.

A Pentagon spokesman, Lt. Col. Samuel House, said that the military “would no longer issue daily updates on the number of inmates participating in the protest, eligible for force-feeding or hospitalized, as had been its practice over the past few months, because the participation has fallen away from its peak two months ago,” as the Times put it.

Lt. Col. House said, “Following July 10, 2013, the number of hunger strikers has dropped significantly, and we believe today’s numbers represent those who wish to continue to strike.” Since September 11, the number of prisoners taking part in the hunger strike has been steady at 19 individuals. This is still considerably more than the seven or so who were long-term hunger strikers when the prison-wide hunger strike began in February, but it is considerably less than the 106 that the military conceded were taking part in the hunger strike from June 28 to July 10.

Noticeably, however, 18 of these 19 men are being force-fed, a process that medical professionals regard as unacceptable, as they have pointed out on several occasions in the last six months.

In April, the American Medical Association (AMA) wrote a letter to the Pentagon stating that “force feeding of detainees violates core ethical values of the medical profession,” and in June, in an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, three medical professors wrote, “Military physicians should refuse to participate in any act that unambiguously violates medical ethics,” adding, “Military physicians who refuse to follow orders that violate medical ethics should be actively and strongly supported.”

Shortly after this editorial was published, 153 doctors from the US and around the world condemned the force-feeding of hunger strikers at Guantánamo in a letter to President Obama that was published in the Lancet, and in July the British Medical Association (BMA) followed suit, writing to President Obama “urging him to immediately suspend the role of doctors and nurses in force-feeding prisoners held at Guantánamo Bay and to launch an inquiry into how the ‘unjustifiable’ practice ha[d] been allowed to develop.”

Here at “Close Guantánamo,” we believe that focusing on the hunger strike being “largely over” deflects attention from the ongoing violation of the core ethical values of the medical profession that is involved in force-feeding prisoners, and we note that it remains an outrage no matter how many or how few men are being subjected, twice a day, to having tubes inserted up their noses and into their stomachs, and force-fed liquid nutrient.

We also believe that nothing should be allowed to deflect from the importance of releasing cleared prisoners, and urge President Obama to do much more than he has done so far. We demand the release of the 84 cleared prisoners, who include 56 Yemenis and 28 men from other countries, and we insist that, if third countries cannot be found for some of those men who face persecution in their own countries, they should be given new homes in the United States.

If you agree with our demands, please contact the White House and the Department of Defense, as outlined below.

What you can do now

Call the White House and ask President Obama to release all the men cleared for release. Call 202-456-1111 or 202-456-1414 or submit a comment online.

Call the Department of Defense and ask Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel to issue certifications for other cleared prisoners: 703-571-3343.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

September 24, 2013

Photos: Save Lewisham Hospital Victory Parade and Rally, September 14, 2013

Save Lewisham Hospital Victory Parade and Rally, September 14, 2013, a set on Flickr.

On Saturday September 14, six weeks after a High Court judge, Mr. Justice Silber, ruled that health secretary Jeremy Hunt had acted unlawfully when he approved plans to severely downgrade services at Lewisham Hospital (see here and here), campaigners and supporters of the hospital — and of the NHS in general — gathered in the centre of Lewisham, in south east London, and marched past the hospital and on to Ladywell Fields, the park behind the hospital, for a celebration of the victory.

At the rally in Ladywell Fields, there were speakers, stalls, bands and a general air of celebration and solidarity that even the rainy weather couldn’t dispel. We are, after all, used to poor weather, as our first march against the proposals, which attracted 15,000 supporters on a Saturday last November, took place in the pouring rain (see here). I took the photos above, which I hope capture something of our general resilience, and our refusal to have our spirits dampened by the rain.

The victory over the Tories, and the senior management of the NHS behind the proposals to downgrade Lewisham, was certainly worth celebrating. The plans for Lewisham, approved by Hunt in January, had been put forward last October by Matthew Kershaw, an NHS Special Administrator appointed to deal with the financial problems of a neighbouring trust, the South London Healthcare Trust, in the first use of the Unsustainable Providers Regime, legislation for dealing with bankrupt trusts that was introduced by the last Labour government.

The proposals had involved Lewisham, a solvent hospital, having its A&E Department shut, so that there would only be one A&E Department for the 750,000 inhabitants of the boroughs of Lewisham, Greenwich and Bexley, and cutting maternity services so severely that nine out of ten mothers in a borough of 270,000 people would have to give birth elsewhere.

The struggle is not over, of course. Hunt has appealed (although I don’t believe that anyone expects him to win), as Mr. Justice Silber ruled that “neither the recommendations of the TSA [the Trust Special Administrator] nor the decision of the Secretary of State reducing the facilities at LH [Lewisham Hospital] fell within their powers,” and also ruled that Hunt and the TSA had failed to satisfy one of four requirements for the proposals; namely, that the plans had “support from GP Commissioners” — something that was powerfully explained by Dr. Helen Tattersfield, the Chair of the Lewisham Clinical Commissioning Group, in a submission that I posted here.

More troubling, as I explained in an article two weeks ago, is the fact that a merger between Lewisham and the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Woolwich, one of the South London Healthcare Trust’s three hospitals, is going ahead as planned. The merger itself is not the problem, as it seems to me that Lewisham’s management would not have agreed to it unless they thought it feasible, but I fear what financial pressures may be exerted in future, because of the SLHT’s debts, running at £1 million a week when Matthew Kershaw was called in last summer.

Part of this debt comes from the ruinous PFI deals negotiated for building Queen Elizabeth Hospital and the Princess Royal Hospital in Bromley, which cost £210 million, but, when repaid, will have cost £2.5 billion. I am reassured that Matthew Kershaw recommended that the Department of Health and the Treasury should cover the shortfall between the amount of income the Queen Elizabeth Hospital and the Princess Royal Hospital can generate from patients and the costs of their PFI payments, estimated by Kershaw to be “between £22 million and £25 million per year, about a third of the overall costs of the annual PFI payments.”

However, Kershaw also recommended — and Hunt accepted — that £74.9 million of efficiencies should be made across all three SLHT hospitals, including the Princess Royal (being taken over by King’s), and Queen Mary’s Hospital in Bexley (being taken over by Oxleas NHS Trust), and the very real fear, of course, is that decisions will be taken about where the axe will fall that will reverse or endanger the huge success secured by the 25,000 campaigners in Lewisham over the last ten months.

While vigilance is required, supporters can at least let their hair down on Friday September 27, at a fundraiser and celebration in the wonderful 1950s Rivoli Ballroom in Crofton Park, and can also join the Lewisham contingent in a trip to Manchester on Sunday September 29 to call for defence of the NHS outside the Conservative Party Conference. Details of those events are here and here.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

September 23, 2013

Book and Video: Ahmed Errachidi, The Cook Who Became “The General” in Guantánamo

In the busy months in spring, when the prisoners at Guantánamo forced the world to remember their plight by embarking on a prison-wide hunger strike, I was so busy covering developments, reporting the prisoners’ stories, and campaigning for President Obama to take decisive action that I missed a number of other related stories.

In the busy months in spring, when the prisoners at Guantánamo forced the world to remember their plight by embarking on a prison-wide hunger strike, I was so busy covering developments, reporting the prisoners’ stories, and campaigning for President Obama to take decisive action that I missed a number of other related stories.

In the last few weeks, I’ve revisited some of these stories — of Sufyian Barhoumi, an Algerian who wants to be tried; of Ahmed Zuhair, a long-term hunger striker, now a free man; and of Abdul Aziz Naji, persecuted after his release in Algeria.

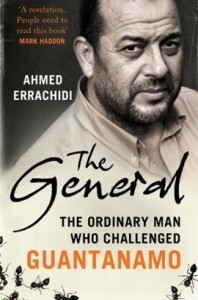

As I continue to catch up on stories I missed, I’m delighted to revisit the story of Ahmed Errachidi, a Moroccan prisoner, released in 2007, whose story has long been close to my heart. In March, Chatto & Windus published Ahmed’s account of his experiences, written with Gillian Slovo and entitled, The General: The Ordinary Man Who Challenged Guantánamo.

As I explained in an article two years ago, when an excerpt from the book was first showcased in Granta:

[In 2006,] when I first began researching the stories of the Guantánamo prisoners in depth, for my book The Guantánamo Files, one of the most distinctive and resonant voices in defense of the prisoners and their trampled rights as human beings was Clive Stafford Smith, the director of the legal action charity Reprieve, whose lawyers represented dozens of prisoners held at Guantánamo.

One of the men represented by Stafford Smith and Reprieve was Ahmed Errachidi, a Moroccan chef who had worked in London for 16 years before his capture in Pakistan, were he had traveled as part of a wild scheme to raise money for an operation that his son needed. What made Ahmed’s story so affecting were three factors: firstly, that he was bipolar, and had suffered horribly in Guantánamo, where his mental health issues had not been taken into account; secondly, that he had been a passionate defender of the prisoners’ rights, and had been persistently punished as result, although he eventually won a concession, when the authorities agreed to no longer refer to prisoners as “packages” when they were moved about the prison; and thirdly, that he had been freed after Stafford Smith proved that, while he was supposed to have been at a training camp in Afghanistan, he was actually cooking in a restaurant on the King’s Road in London.

“The Cook Who Became The General” was the proposed title of a book telling Ahmed’s story, which Clive suggested I should write with him, after I wrote an article that Ahmed picked up on after his release in Morocco in March 2007. This never came about, although I remained in touch with Ahmed, and I sometimes regret that I have been too desk-bound in my Guantánamo work, and missed out on having Ahmed tell me his story while cooking for me at his home in Tangier.

I have still not made it to Tangier to meet Ahmed, although I hope that one day I will. In the meantime, however, to promote Ahmed’s book, Giles Whittell of the Times visited him for a major feature in the Times‘ magazine on Saturday March 16, which I’m cross-posting below, along with a powerful video Ahmed made in Morocco in May, discussing, in particular, the hunger strike, and his fears for a friend he left behind at Guantánamo, who was cleared for release when he was, but was not freed. That man is Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, whose release I — and many, many other people — have been seeking and demanding for many years.

I wholeheartedly recommend The General: The Ordinary Man Who Challenged Guantánamo, which can be bought via Amazon in the UK and in the US. You can also listen to Ahmed talking to the BBC on Outlook, on the World Service, in a program that was first broadcast on May 8, 2013.

Prisoner 590 talks to Giles Whittell

The Times, March 16, 2013

Ahmed Errachidi was a chef in a Mayfair hotel. In 2002 he was imprisoned in Guantanamo Bay. For five years he was shackled, beaten, sprayed, groped, taunted, interrogated. Ahmed was innocent. This is his story.

At one point in the dreadful weeks after 9/11, Ahmed Errachidi allowed himself to think he might be saved by British secret agents. It was a forlorn hope, but he had no other sort to cling to.

Errachidi is a big, proud, fearless man, born in Morocco, fond of London and once a fan of Spurs. He is also a devout, well-travelled Muslim. In early 2002, as US special forces scoured Afghanistan for any trace of al-Qaeda leaders, he was arrested by Pakistani police across the border in the badlands of Waziristan.

How he got there is convoluted enough, but it was only the beginning of his story. Suspected of terrorism, he was sent via a series of jails to an interrogation centre in Lahore. Eventually, he was visited there by two men from the FBI. He imagined they would quickly check his background and arrange for his release. Instead, they transferred him to Kabul. Part of the giant Bagram airbase outside the Afghan capital was by then a US-run internment camp, and it was there that he heard British accents for the first time since leaving London.

He was not in good shape. He had spent six weeks being shackled, beaten and malnourished as his life ran out of control and the world around him descended into war. To make matters worse he was, his doctors said, bipolar, although the diagnosis would in the end help him.

Errachidi was told the British voices belonged to officers from MI5. “When I heard them coming, I thought, ‘My torture is over. My pain is over, because now I’m going to deal with someone who is civilised,’” he says. “I had one foot in freedom.”

In fact, the British were no help at all. They questioned him, gave no indication as to whether they believed him, and said in any case their hands were tied. Bagram was to all intents and purposes America.

And so the interrogations continued. Errachidi was moved to Kandahar, where he says his guards once spent a day removing his leg irons with bolt cutters and hacksaws. By the end he was sitting in a pool of his own blood. From Kandahar he was flown to Guantánamo Bay (26 hours on the floor of a troop transport) and there he spent five and a half years – beaten, sprayed, groped, taunted, interrogated and deprived of sleep so routinely that the monotony became almost as unbearable as the abuse.

Four of those years were spent in punishment blocks, in solitary confinement.

“How do I know?” he asks. “I counted out the year or so that I was not in isolation.”

Some of what Errachidi endured at America’s naval base on the southeast tip of Cuba will be familiar to connoisseurs of the “enhanced interrogation”, or torture, that the Bush Administration encouraged there. Some has not been reported until now. What makes his story unique is his response: he got mad, and almost got even. He became Guantánamo’s de facto guerrilla commander, sustained by small victories against the prison regime and fuelled in his search for bigger ones by a deep and boundless anger.

When detainees were forced to wear shirts they did not like, Errachidi persuaded them to rip them up. When their Korans were abused and prayer times interrupted, he led a series of rebellions to ensure they were respected. When things got desperate in 2006, and prisoners living with mounds of their own faeces were brought food by guards in full biological warfare suits and respirators, he daubed the words “YOU CRIMINALS” on his cell wall in his own blood.

Errachidi was in the first wave of prisoners to arrive at Guantánamo after 9/11, presented to their guards as the “worst of the worst” – men trained to kill and die and supposedly taught not to feel pain. Because of his influence over his fellow inmates, Errachidi was assumed to be senior al-Qaeda. He was nicknamed “the General”.

A secret 2004 memo from the camp commander to the Pentagon’s Southern Command headquarters in Miami was the closest thing US officials ever issued to a rap sheet for prisoner 590. It said he had “known affiliations with several Islamist extremist groups, to include a direct association with the leader of the Moroccan Islamic Fighting Group as well as other contacts with known members of al-Qaeda”. He had travelled to Afghanistan, the memo continued, “to participate in jihad against the US”. Another document stated that in July 2001 he had received weapons training and bomb-making classes at the al-Farouq Training Camp, knew how to conduct suicide attacks on airliners with smuggled flammable liquids and had issued a fatwa authorising prisoner suicides.

Despite all this, the force of Errachidi’s rage still mystified his captors. One camp commander, Colonel Mike Bumgarner, risked his career by negotiating with the General, hoping to restore order in return for quality-of-life concessions. The deal didn’t hold, and at the end of his tour of duty Bumgarner was left scratching his head. What was it about this man that he had failed to grasp? The answer was simple. Errachidi was angry because he was innocent. In five and a half years, not a shred of evidence of terrorist activity or links to terrorists was produced against him. The allegations on the two official memos in his Guantánamo file were invented. Ahmed Errachidi was not al-Qaeda. He was a cook. He was not even a cook for jihadists, but for paying customers at a string of restaurants, some of them quite swanky, in London, his adopted home, where he had worked for 17 years.

In the summer of 2001, when he was supposed to be learning bomb-making in the mountains outside Kandahar, he was working shifts at the Westbury hotel in Mayfair. It would have been easy to check – by phone or even on foot. The Westbury is on New Bond Street, three blocks from the US Embassy in Grosvenor Square. But no one bothered. No one, that is, except Clive Stafford Smith, the British-born human-rights lawyer. He met Errachidi in 2004, contacted the hotel and verified the story, whereupon the case against the General began to fall apart.

Six years on from his release, Errachidi has written a memoir. It took him two years to decide to write it and one to get it finished, and it is his first full account of his lost years as a suspected enemy combatant. It takes the reader step by step down through the multilevel hell on Earth created to dismantle al-Qaeda, and it will force anyone still on the fence about Guantánamo Bay to reassess not only what the camp says about America, but also the supposedly just war that filled it.

Errachidi condemns 9/11, but also the sledgehammer response. “If the US Army had gone into [Afghanistan] to look for bin Laden and al-Qaeda, or even the Taleban for that matter, I’d have been in favour,” he writes. “But I didn’t think and still don’t think they had a right to bomb civilians from the air… You can’t terrorise 29 million people and claim you are fighting terrorism.” (Estimates of the civilian death toll in the first four months of the war in Afghanistan range from 1,000 directly killed by air strikes to 20,000 when refugee deaths from disease and hunger are included.)

Errachidi writes and talks as someone who put himself under that bombardment and paid dearly. He has survived with a hard-boiled take on the morality of fighting terrorism – “To me, killing people with a car bomb or an F-16 is the same thing” – and a belief that he needs to tell the world what has really been happening in Guantánamo Bay before it loses focus and moves on. Why should we care? He’s a cook with a Moroccan high-school education. The broad outlines of the abuse of prisoners and due process at Guantánamo are already known. And as President Obama has found, shutting the place down – given the risk that detainees sent home will be tortured (again) – is easier said than done.

For what it’s worth, Errachidi says that risk is wildly exaggerated. He calls it “the big lie, the old song”. Furthermore, Obama’s failure to keep his promise to shut Guantánamo creates the prospect of indefinite detention without trial on US-controlled territory, which would be a monstrous hypocrisy and a systematic denial of justice even if every inmate there were guilty of crimes against humanity. As it is, according to the available evidence, the vast majority are not. Errachidi is a case in point. That the camp is still open six years after his release makes his story more urgent, not less.

“This is me coming out of my shell,” he says, as we look for a patch of sun against which to take his picture in the steep backstreets of Tangier, where he was born and raised and where he now owns a thriving café above the port. His publisher would like him to come out of his country, not just his shell, to talk more widely about what he has written, but he can’t – he has no passport. The Moroccan government has refused to issue one since his release, but he believes the US is trying to muzzle him and blames Washington “for using the Moroccans as a jailer”. (The US Embassy in Rabat declined to comment.)

He hates being reminded he is now a prisoner in his own country. But the reminder comes anyway, the day after we first meet. He wants to show us the Atlantic coast, both for another picture and because it is magnificent. So we drive there in his 4×4, through Tangier’s salubrious western suburbs and past discreet walled compounds, ending at a famous lookout point above Hercules’ Cave.

Some Interior Ministry officials have got there first. They’re wearing dark glasses and long black overcoats as if supplied by central casting. They ask for permits. Without the right papers, a photo session is out of the question. Errachidi assumes they’ve been following us and boils over. After a brief shouting match we leave, reversing at high speed. He holds the steering wheel with one hand and his iPhone in the other, taking pictures of the goons and reminding them that he funds their Toyota Land Cruiser with his taxes.

It takes him a while to calm down. Further up the coast we stop and he sits, fuming.

“This is how I get when I get angry,” he says. “When I’m provoked, I feel as if I’m back in Guantánamo.”

He was taken there because of a disastrous overlap of world history and his own.

From his café in central Tangier, the view of Europe is extraordinary. Seven miles away across the Strait of Gibraltar lie Spain, the Rock and opportunity. Dozens of bodies of Africans who set out to swim to a better life are washed up on Tangier’s beaches every year, but in 1985 the 18-year-old Errachidi knew better. He acquired his first passport and a Spanish tourist visa, and took the ferry.

At large in Europe, he headed first for Chesterfield, where he had a standing invitation from a couple he’d once shown around Tangier. He gravitated to London and felt oddly at home. “I even liked it when it was dark and rainy and I couldn’t catch the vaguest glimpse of the sun,” he writes. He found it easy to get on with Brits. He learnt the language, learnt to cook and learnt the fine art of extracting visa extensions from the Home Office.

By 2001 he had a wife and children in Tangier, but his work was still in London. It was a complex life, made more so by a nervous breakdown when his father died, a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and a running battle over his immigration status. Worse than any of these was a heart defect detected in his infant son, Imran.

Errachidi had friends in London, mainly from the mosques he attended in Finsbury Park and Regent’s Park. But he was feeling a long way from where he was most needed.

Then the twin towers were attacked. He watched “with disbelief and horror” in a North London café as they fell. Soon afterwards, he was told that Imran would need expensive surgery to fix his heart. “In the run-up to that news I was already thinking of starting my own business,” he says. “When the news came it was like a light going on: time to go, time to do it.”

He knew that if he left Britain he might not be allowed to return, but Britain, for once, was not part of his plans. Pakistan was.

At this point, his movements became, in retrospect, a series of red flags for intelligence analysts: fighting-age Moroccan male who attends radical North London mosques heads to Pakistan weeks after 9/11. Crosses into Afghanistan as refugees pour out. Picked up in northern Waziristan as hunt for Osama bin Laden moves there from Tora Bora.

It might have helped that his explanation fell into the category of stuff you can’t make up. But it didn’t help. People with the power to free or detain him simply did not believe him.

His account goes like this: on leaving London for the last time, Errachidi went first to Morocco to see his family. Then he flew to Islamabad in search of silver jewellery to bring back in his suitcase and start selling. (He’d opted for silver from Pakistan over silk from China or Turkey, but had also considered getting into washing-up liquid and rabbits; there is a decent market in Morocco for rabbit meat.)

In Islamabad, he spent some of his time scoping out the local silver markets but much of it watching CNN and BBC World News in his rented room, and crying. “What they were showing on TV was just catastrophic. All the channels, they were doing a lot on all these refugees, all these children crying, facing death, fleeing their homes.”

He realised this misery was unfolding a few hours’ drive away across the Afghan border and, he says, resolved to go and help. He claims he went out of simple fellow feeling and because of his distress over his son – rather than despite it. “I had my pain, my problems,” he says. “I desperately wanted to get away from them.”

For dozens of interrogators, this defied credulity. Readers may share their doubts, and even Stafford Smith concedes the story makes sense to some only in the light of Errachidi’s bipolar disorder. Nonetheless, it is his story. It has never changed, and after seven hours in his charming, outraged company, I could only conclude it was the truth.

To get to Kabul he took taxis when he could and walked when he had to, sometimes at night. There, he says, he saw collateral damage up close: sometimes the survivors of extended families ripped apart by bombs from the sky, sometimes just warm limbs. He spent 25 days cooking for a refugee convoy travelling from Kabul to Kandahar. At one point, a grateful boy proffered a double handful of walnuts, and it all seemed worth it.

Strolling along Tangier’s main beach at dusk more than a decade later, he says he often thought of that boy’s hands when looking at his own, in handcuffs in Guantánamo.

Camp rules required prisoners to push their hands through a hole in their cell doors, wrists together, to be cuffed before leaving for exercise or being moved to another cell. New detachments of guards would often tremble with fear when first forced into close proximity with inmates for this sort of chore. But most would quickly lose that fear, and then it was the prisoners’ turn to be afraid.

The first wave, almost all of whom have now been released, were guinea pigs in a long-running experiment in how to control and extract information from supposedly hardened terrorists without blatant violation of the Geneva Conventions.

A young Russian, also arrested in Pakistan and taken to Guantánamo, told The New York Times after his release: “In Russia, they beat you up; they break you straightaway. But the Americans had their own way, which is to make you go mad over a period of time. Every day they thought of new ways to make you feel worse.”

Errachidi experienced them all, sometimes all at once. He lists some: extreme cold; food and sleep deprivation; pepper spray; continuous loud noise from industrial vacuum cleaners and strimmers placed near the cells; strong-smelling liquid sprayed over the cells’ all-metal surfaces that brought on headaches, vomiting and dizziness. In principle, guards were not supposed to beat up inmates. In practice, he says beatings by special units on the pretext of maintaining order were routine.

“In the middle of all this we were like zombies,” he says. “Then this woman soldier would come with a piece of chocolate and make me watch, and she would start moving her body and slowly eating it.” His reaction was fear rather than arousal – “The fear that you are not dealing with a human being. To think that the human being in front of you has no mercy is more frightening than losing your freedom.”

Some guards did not conform to type. Errachidi remembers one, a Vietnam vet, who stood out as older, calmer and more obliging than the others. Another, Terry Holdbrooks, sought out prisoner 590 for conversations about Islam and converted while on the base. He told an interviewer later that when his fellow guards found out they promised to “skull-f*** the Taleban” out of him.

“But most of them were KKK,” Errachidi says, using the term loosely. “They were immune when they saw us in pain. There was a lot of yee-hah and jumping for joy when they saw us screaming.”

It is now nine years since the Abu Ghraib scandal in Iraq first exposed this sort of behaviour by US soldiers; and nine years also since the US Supreme Court first resisted White House efforts to create at Guantánamo what one Bush Administration official called “the legal equivalent of outer space”. Even so, it would be another two years before Stafford Smith managed to persuade US officials that Errachidi was not worth detaining any longer.

In the meantime, Mike Bumgarner’s efforts to find common ground with his prisoners failed. The place became, in prisoner 590’s words, a war zone. He was accused of inciting hunger strikes and suicide attempts – falsely, he says – and was placed in a punishment block for what he describes as 23 straight days of torture. To protest their innocence rather than merely their conditions, prisoners started defecating on their cell floors instead of in their buckets for up to ten days at a time.

In June 2006, three inmates, two Saudis and a Yemeni, hanged themselves in their cells.

At no point, Errachidi says, did any of his dozens of interrogators take seriously his claims of innocence. “They were told to get ‘actionable intelligence’, not show that the US had made a gross error,” says Stafford Smith. “Most interrogators were simply trying to confirm things that others had said, most of which were false. Such are the fruits of coercion.”

Stafford Smith says Errachidi’s bipolar diagnosis was vital for winning back his freedom. Without it, his decisions to travel to Pakistan and then Afghanistan at such a dangerous time were not deemed explicable.

Looking back, does he consider those decisions rational? “I was as normal as I am talking to you now,” he says. “What affected my decisions was the health of my son. The news that he would need an operation was a catastrophe.”

He makes two further points: for a Muslim with a Moroccan passport and no European work visa but a compelling need to start a business, Pakistan was not a crazy place to go, even in late 2001. It was one of few sensible options open to him. As for his one-man mercy mission to Afghanistan, he wonders why he should believe the US Army went there partly to relieve suffering if US soldiers refuse to believe that he, as a Muslim, might want to do the same.

By 2006, Bumgarner had given up on Errachidi and allowed his name to go on a list of inmates eligible for release. Actual release did not come for another year, and when it did, it was abrupt. “Five and a half years, then, ‘You’re free to go,’” he says, still sounding amazed. “No explanation, no apology, nothing.” Just a kit bag containing some cheap clothing and toiletries. But freedom came with a bonus: his son, Imran, had recovered without surgery and was now a healthy six-year-old at primary school.

Errachidi still sees orange prison suits in his nightmares, but he is a survivor. Besides his café, he owns a chicken restaurant up the hill. Some of the Brits who fly in on Ryanair have probably been there. If not, they should. It’s good, and its owner is a generous host. He believes George Bush, Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld should stand trial for what has happened at Guantánamo. He is furious with Obama for leaving it open and resents Hillary Clinton’s lectures on human rights over the past four years. Otherwise, he bears no grudges: “I can distinguish between people and their leaders,” he says, a man of the world itching for his horizons to expand again. “If I had a visa, I’d take my kids to Disneyland tomorrow.”

‘The soldier sprayed hot gas into our faces’: An extract from The General: The Ordinary Man Who Challenged Guantánamo, dealing with one night when the emergency reaction force stormed the cells

When I first got to Guantánamo, protests tended to be reactive and spontaneous, and running underneath them there was an air of hopelessness: few of us felt we had any way of stopping the things that were done to us. The longer I was there, the more convinced I became of the need to change that sense of powerlessness.

Since Korans were not allowed in punishment [cells], the soldiers were supposed to call the chaplain or the interpreter to collect the Koran and keep it safe until the prisoner had served his term of punishment. But on one awful night, the soldiers broke their own rules and began to use force to remove Korans from prisoners arriving in punishment block India.

We started banging on the doors and shouting. The soldiers took no notice. So, in order to demean them in the same way that they were demeaning us, one of the prisoners started shouting out the name of Osama bin Laden. All the prisoners took up the chant, “Osama bin Laden, Osama bin Laden.’’ I joined in. It was very scary at first.

Our shouts enraged the soldiers. They wanted to take something from us but we had so little: in the end, they could only demand that we give up our towels. We refused and continued to taunt them. So they sent for an emergency reaction force (ERF) to storm our cells.

ERFs were made up of five or six soldiers wielding shields and wearing black protective clothing over their military uniforms as well as helmets. This gear was designed not only to protect them but also to cast fear: their appearance was much more terrifying than any normal human figure. When they were ready to attack a prisoner in his cell they’d form a human train, the soldier at the front wielding the large shield, the kind riot police use, like a fat tube cut in half lengthways. The cell door would be opened, another soldier would spray a hot gas known as OC (oleoresin capsicum) spray into the prisoner’s face, causing excruciating pain to eyes, skin and throat as well as choking the prisoner and making him collapse. Once the prisoner was on the ground, the other soldiers would rush in and beat him.

They used different methods for these beatings. Some would press as hard as they could on the soft point behind our ears. Some would lift our heads off the ground before smashing them down on the metal floor. Some would twist our fingers back hard enough to break them. And all the time they were doing this they’d be shouting, “Do not resist, do not move,” even though by this point it was impossible to do either. They also filmed these attacks, telling us this was to “ensure the safety of the prisoner”, which was laughable given the damage they were doing. Afterwards they’d use the medical kit they had brought with them to staunch the bleeding, bruising and bone fractures they’d inflicted on us. But before this first aid was applied, our hands and feet would be shackled from behind as we lay face down on the floor; they’d put our faces over the toilet.

Such attacks would last for about 15 minutes and then, after administering the first aid, they’d remove the shackles and then, holding on to each other, would slowly withdraw from the cell in a line, the last soldier remaining to restrain the prisoner until he was finally pulled from the prisoner’s body with such force that they’d all end up falling backwards. Then the cell door would be slammed shut. And all the time other prisoners could see what was happening through gaps around the door hatches, although we weren’t in a position to do anything other than bear witness and find ways to express our rage. We’d call to each other, beating on the doors and walls of our cells to show that we prisoners were as one.

The ERF attacked prisoners one by one. That night in India these attacks were repeated at least 20 times. They had started in Mishal’s cell [Mishal al-Harbi, who suffered brain damage as a result of the attack]. I could hear him yelling and I could hear the sounds of them beating him. Through the small gaps in the edges of the food slots in our doors, some of the prisoners saw them bringing Mishal out on a stretcher. They also saw blood.

The situation escalated. By now we were all yelling into the exhaust pipes at the back of our cells, because if we shouted there, other blocks might hear. Mishal was taken to hospital, but our night didn’t end there. They began to beat us, cell by cell.

© Ahmed Errachidi and Gillian Slovo 2013. Extracted from The General: The Ordinary Man Who Challenged Guantánamo, published by Chatto & Windus.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

September 22, 2013

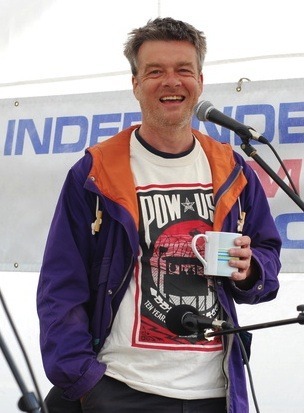

Andy Worthington Joins Film-Makers and Authors to Judge Contest for Short Films About Torture

Are you a film-maker and an anti-torture activist? If so, then a video contest, for which I’m a judge, will be of interest to you. The Tackling Torture Video Contest, launched in Minneapolis on June 30 by by Tackling Torture at the Top, a committee of WAMM (Women Against Military Madness), is open to both amateur and professional filmmakers.

Are you a film-maker and an anti-torture activist? If so, then a video contest, for which I’m a judge, will be of interest to you. The Tackling Torture Video Contest, launched in Minneapolis on June 30 by by Tackling Torture at the Top, a committee of WAMM (Women Against Military Madness), is open to both amateur and professional filmmakers.

The deadline for entries is January 9, 2014. For full details see here — and see here for the home page.

Videos can be anything from 30 seconds to 5 minutes in duration. The contest is open to any citizen of any nation, but all videos must be in English or have full translations of all sound and text into English as part of the videos themselves.

There are four prizes in the competition: a $500 jury prize in the “serious” category; a $500 jury prize in the “humorous/satirical” category; and two $300 Audience Favorite prizes, one for “serious” and one for “humorous/satirical.”

After the deadline, 20 finalists will be announced. The selection will be made by members of Tackling Torture and the Top and WAMM. At this point the videos will be made available for audience voting, and the competition’s five judges will also view the films and make their decisions. Judging will be competed by January 30, 2014, and the winners will be announced on February 7, 2014, on the 12th anniversary of George W. Bush’s notorious memo authorizing the use of torture by declaring that the Geneva Conventions did not apply to prisoners seized in the “war on terror.”

The judges for the competition are:

Sebastian Doggart, producer of the award winning biographical documentary “American Faust: From Condi to Neo-Condi.”

Joseph Jolton, filmmaker, adjunct faculty, Media Arts, Minneapolis College of Art and Design

Professor Peter Kuznick, Professor of History at American University, co-writer with Oliver Stone of “The Untold History of the United States” documentary series for Showtime

Professor Alfred McCoy, J.R.W. Smail Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, author of A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror and Torture and Impunity: The US Doctrine of Coercive Interrogation .

Andy Worthington, investigative journalist and filmmaker, author of The Guantánamo Files and co-director, with Polly Nash, of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo.”

This is how the organisers describe the contest:

Despite US and international law prohibiting the use of torture, the US has used torture, often euphemistically called “enhanced interrogation techniques,” in its so-called “War on Terror.” Despite the law, despite documented proof that such efforts produce inadmissable evidence, false information and false confessions, and despite the blowback of such efforts, the US continues to shield the lawbreakers –both those who committed and those who authorized torture — by “looking forward, not backward,” and there is evidence that such techniques continue to be used and falsely justified.

Through TV shows like “24” and Hollywood films like the commercially successful “Zero Dark Thirty” and the new documentary “Manhunt,” the US’s use of torture is presented as viable, and even necessary to our country’s security. Unfortunately, a majority of the under-informed and misinformed public now thinks that torture is necessary and useful.

Tackling Torture at the Top, through this contest, hopes to produce entertaining and informative videos that contradict this harmful and inhumane view, educate the public, raise questions about the direction of our foreign policy and our use of the military, and by so doing, give the public the awareness and courage to rein in our country’s out of control security apparatus.

The contest managers are Tom Dickinson and Coleen Rowley (former FBI agent and whistleblower) on behalf of Tackling Torture at the Top Committee of WAMM, Minnesota, USA. For further information contact them here and also see their Facebook page.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

September 21, 2013

Petition and Protest: Stop This Callous Government’s Sickening War on the Disabled

[image error]Please sign the petition to the British government to end the “War on Welfare,” which currently has over 55,000 signatures but needs 100,000 to be eligible for a Parliamentary debate, and, if you can, come to the ’10,000 Cuts & Counting’ protest in Parliament Square on Saturday September 28.

The British government’s assault on the poor, the ill, the unemployed and the disabled is so disgraceful that it’s often difficult to know which particular horror is the worst, although every time that their attacks on the disabled come under the spotlight I’m reminded of the importance of the saying, “The mark of a civilised society is how it treats its most vulnerable members” — attributed, in various forms, to Mahatma Gandhi, Winston Churchill and Harry S. Truman — and it strikes me that the most disgusting of all the oppressive policies directed at the most vulnerable members of society by sadistic Tories masquerading as competent politicians — backed up by their Lib Dem facilitators and the majority of the mainstream media — is their war on the disabled.

The people behind these assaults overwhelmingly identify themselves as Christians, even though no trace of Christian values exists in their policies, and they are, instead, waging war on the very people that Christ would have told them are in need of their protection most of all.

I have been covering the government’s war on the disabled since 2011 (see my archive of articles here and here), and a brief explanation of what has been happening can be found in an article I wrote last August, in which I explained:

As the centrepiece of its mission to impoverish the disabled, the government has implemented a Work Capability Assessment, designed to establish that people with serious physical and/or mental disabilities are, in fact, fit for work, and can have their financial support cut — and, in some circumstances, be forced into unpaid work. Beginning [in 2013], with the stated aim of cutting spending by 20 percent over the next three years, the Disability Living Allowance (DLA), which, as the Guardian put it, “pays out a maximum of £130 a week [and] is a welfare payment designed to help people look after themselves and aimed at those who find it difficult to walk or get around,” will be replaced by the Personal Independence Payment (PIP), heavily criticised by disability campaigners. Moreover, the fact that the government has announced its intention to cut spending by 20 percent indicates that it is driven by cost and not by need, as is also clear from an examination of the tests run for the Department for Work and Pensions by the French company Atos Healthcare.

The tests, are, by any objective measure, a disaster, as they deliberately fail to provide an accurate assessment of claimants’ illnesses, and are being overturned on appeal to such an extent that any attempt to claim that the system is credible is being thoroughly undermined. As I explained in another article last year, “the inconvenient truth [for the government is] that, on appeal, tens of thousands of decisions made by Atos’ representatives are being overturned. The average is 40 percent, but in Scotland campaigners discovered that, when claimants were helped by representatives of Citizens Advice Bureaux, 70 percent of decisions were overturned on appeal.” Of the 1.8 million assessments carried out by Atos since 2009, around 600,000 have been the subject of an appeal, costing the government £60m.

In July, Atos was severely criticised by the Department for Work and Pensions, following what the Independent described as “months of complaints about allegedly unfair and slapdash decisions” made by the company. The DWP “audited around 400 of the company’s written reports into disability claimants, grading them A to C. Of these, 41 per cent came back with a C, meaning they were unacceptable and did not meet the required standard.” What this meant in practice was that “a serious error or omission occurred, such as no evidence to justify the recommendations,” or there were “inconsistencies in the evidence provided.”

Surprisingly, the findings led the DWP to describe the poor quality of the reports as “contractually unacceptable,” and to decide to strip Atos of “its monopoly on deciding whether people with disabilities are fit to work,” as the Independent described it. The DWP announced that “it would be inviting other companies to bid for fresh regional contracts by summer 2014,” but although this is a blow for Atos, it is unlikely that any replacement company will do a more objective and honest job, given that the whole purpose of the reviews is to cut the number of claimants; in other words, to fix reality around the policy.

In a powerful article in the Guardian, Amelia Gentleman greeted the news about Atos as follows:

Many people will welcome the Department for Work and Pension’s decision to bring in new providers alongside Atos to perform the work capability assessment (WCA), and to retrain existing Atos staff.

They will include Sylvia Newman, whose husband, Larry, was found fit for work after an Atos assessment. After a long career in work, he had developed a serious lung condition, his weight had dropped from 10 to seven stone and he had trouble walking and breathing. In order to qualify for employment and support allowance (ESA), the new sickness benefit worth £95 a week, he needed 15 points in the test; he was given zero. He was dismayed to note a number of significant inaccuracies in the Atos report, and decided to appeal, but died from lung problems, before the appeal was heard. One of the last things he said to his wife before doctors put him on a ventilator was: “It’s a good job I’m fit for work.”

Last year the Guardian reported on the case of Ruth Anim, who was told after an Atos assessment that she was capable of finding work in the near future, despite the fact she needed constant one-to-one care, had no concept of danger and attended life skills classes to learn practical things like how to make a sandwich or a cup of tea. She was also described in the Atos report as a “male client”. Atos apologised for “any discrepancy in our report and any distress this may have caused.”

Amelia Gentleman also highlighted the complaints about the underlying problems with the system:

[S]ome campaigners say the real cause of most problems associated with the WCA is not the company that carries out the tests but the underlying policy it is paid to implement. By focusing anger on Atos, attention is distracted from the government’s drive to reduce the numbers of people claiming sickness benefits, under which the eligibility criteria have been narrowed so that many severely ill and disabled people no longer qualify. Changing the company providing the test may not change the experience of many claimants, as the new providers will be obliged to test people according to the same criteria.

Caroline Hacker, head of policy at Parkinson’s UK, said : “This report confirms what many disabled people already know, that Atos Healthcare has been failing thousands of people across the UK for the last five years. Put simply, this admission of failure is far too little too late.

“Not all blame for the ongoing failures of these tests can be levelled solely at Atos Healthcare, who operate within the government’s utterly inadequate method of assessing our most vulnerable citizens. All too often we hear from people with Parkinson’s – a progressive condition – who are told that they will be fit to work in a year’s time because they’ve failed to score enough points under the government designed system.”

Highlighting the ongoing injustice of the assessment process, a coalition of campaigners — including Disabled People Against Cuts, Black Triangle Campaign, Disability Arts Online and Atos Stories — have come together to put together an event on Saturday September 28, beginning at 12 noon in Parliament Square, entitled, ‘10,000 Cuts and Counting,’ described as “a ceremony of remembrance and solidarity for those who have had their lives devastated by the austerity programme, including more than 10,000 people who died shortly after undergoing the Atos Work Capability Assessment, the degrading test used by the government to assess the needs of people receiving benefits related to disability and ill health.”

You can also sign up and share the event on Facebook, and for a collection of powerful stories about disabled people’s experiences of the Atos assessments, please see the Facebook page Atos Miracles.