Andy Worthington's Blog, page 128

October 22, 2013

150 Days of the GTMO Clock: Despite Obama’s Promise, Just Two out of 86 Cleared Prisoners Freed from Guantánamo

[image error]Today the GTMO Clock, an initiative launched by the “Close Guantánamo” campaign in August, marks a sad anniversary — 150 days since President Obama promised to resume releasing prisoners from Guantánamo who were cleared for release by an inter-agency task force he appointed when he took office in 2009. Although 86 men (out of 166 prisoners in total) were cleared for release when the president made his promise on May 23, just two of those 86 men have been freed in the last five months.

Please visit the GTMO Clock site, like it, share it and tweet it if you regard this as unacceptable.

President Obama made his promise in a major speech on national security issues, when he stated, “I am appointing a new, senior envoy at the State Department and Defense Department whose sole responsibility will be to achieve the transfer of detainees to third countries. I am lifting the moratorium on detainee transfers to Yemen, so we can review them on a case by case basis. To the greatest extent possible, we will transfer detainees who have been cleared to go to other countries.”

Since that speech, two envoys have been appointed — Cliff Sloan at the State Department (in June), and Paul M. Lewis at the Pentagon, in an appointment announced two weeks ago. Sloan, described by The Hill as “a veteran Washington attorney and civil servant,” clerked for Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, and, more recently, was the publisher of Slate magazine, and legal counsel for the Washington Post‘s online operations. Lewis has served as General Counsel for the House Armed Services Committee, and the director of the Office of Legislative Counsel in the Office of the General Counsel of the Department of Defense. He begins his job on November 1.

Encouragingly, a Pentagon press release described Lewis as the “Special Envoy for Guantánamo closure,” and it is to be hoped that he will help to fulfill the president’s other promises. Despite lifting his own moratorium on releasing cleared Yemenis, which he imposed following a failed bomb plot in December 2009 that was hatched in Yemen, the president has failed to release any Yemenis, even though they comprise two-thirds of the 84 cleared prisoners.

In fact, the president has released just two prisoners since he made his promise to resume releasing prisoners — two Algerians who were repatriated in August.

To demand the release of all the prisoners who were told in January 2010 that the US government no longer wished to hold them — and who, in many cases, were cleared for release by military review boards under President Bush, in 2006 and 2007 — please do the following:

What you can do now

1. Call the White House and ask President Obama to release all the men cleared for release. Call 202-456-1111 or 202-456-1414 or submit a comment online.

2. You can also call the Department of Defense, and ask Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel to issue the certifications required by Congress to enable prisoners to be released, on 703-571-3343.

3. Please also feel free to write to the prisoners at Guantánamo.

Note: This article was published simultaneously here and on the website of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

150 Days of the GTMO Clock: Despite Obama’s Promise, Just Two out of 84 Cleared Prisoners Freed from Guantánamo

[image error]Today the GTMO Clock, an initiative launched by the “Close Guantánamo” campaign in August, marks a sad anniversary — 150 days since President Obama promised to resume releasing prisoners from Guantánamo who were cleared for release by an inter-agency task force he appointed when he took office in 2009. Although 86 men (out of 166 prisoners in total) were cleared for release when the president made his promise on May 23, just two of those 86 men have been freed in the last five months.

Please visit the GTMO Clock site, like it, share it and tweet it if you regard this as unacceptable.

President Obama made his promise in a major speech on national security issues, when he stated, “I am appointing a new, senior envoy at the State Department and Defense Department whose sole responsibility will be to achieve the transfer of detainees to third countries. I am lifting the moratorium on detainee transfers to Yemen, so we can review them on a case by case basis. To the greatest extent possible, we will transfer detainees who have been cleared to go to other countries.”

Since that speech, two envoys have been appointed — Cliff Sloan at the State Department (in June), and Paul M. Lewis at the Pentagon, in an appointment announced two weeks ago. Sloan, described by The Hill as “a veteran Washington attorney and civil servant,” clerked for Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, and, more recently, was the publisher of Slate magazine, and legal counsel for the Washington Post‘s online operations. Lewis has served as General Counsel for the House Armed Services Committee, and the director of the Office of Legislative Counsel in the Office of the General Counsel of the Department of Defense. He begins his job on November 1.

Encouragingly, a Pentagon press release described Lewis as the “Special Envoy for Guantánamo closure,” and it is to be hoped that he will help to fulfill the president’s other promises. Despite lifting his own moratorium on releasing cleared Yemenis, which he imposed following a failed bomb plot in December 2009 that was hatched in Yemen, the president has failed to release any Yemenis, even though they comprise two-thirds of the 84 cleared prisoners.

In fact, the president has released just two prisoners since he made his promise to resume releasing prisoners — two Algerians who were repatriated in August.

To demand the release of all the prisoners who were told in January 2010 that the US government no longer wished to hold them — and who, in many cases, were cleared for release by military review boards under President Bush, in 2006 and 2007 — please do the following:

What you can do now

1. Call the White House and ask President Obama to release all the men cleared for release. Call 202-456-1111 or 202-456-1414 or submit a comment online.

2. You can also call the Department of Defense, and ask Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel to issue the certifications required by Congress to enable prisoners to be released, on 703-571-3343.

3. Please also feel free to write to the prisoners at Guantánamo.

Note: This article was published simultaneously here and on the website of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

October 21, 2013

How the Egyptian Media Has Reported the Story of Tariq Al-Sawah, a Severely Ill Prisoner in Guantánamo

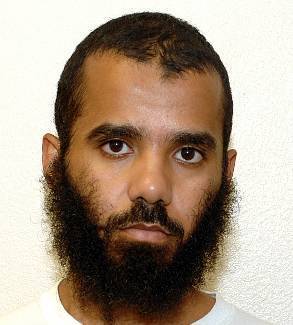

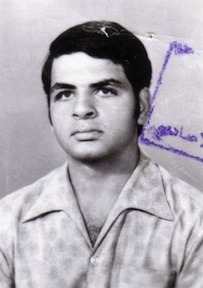

Last week I reported the story of Tariq al-Sawah, the last Egyptian prisoner in Guantánamo, whose lawyers are seeking his release because “his health is too poor for him to pose any kind of threat.” Al-Sawah (also identified as Tarek El-Sawah), an explosives expert for al-Qaeda who became disillusioned with his former life and has cooperated extensively with the authorities in Guantánamo, is “in terrible shape after 11 years as a prisoner at Guantánamo Bay, a fact even the US military does not dispute,” as the Associated Press explained in a recent article. He is 55 years old, and as the AP also noted, his weight “has nearly doubled” in his long imprisonment, “reaching more than 420 pounds at one point, and his health has deteriorated as a result, both his lawyers and government officials concede.”

Last week I reported the story of Tariq al-Sawah, the last Egyptian prisoner in Guantánamo, whose lawyers are seeking his release because “his health is too poor for him to pose any kind of threat.” Al-Sawah (also identified as Tarek El-Sawah), an explosives expert for al-Qaeda who became disillusioned with his former life and has cooperated extensively with the authorities in Guantánamo, is “in terrible shape after 11 years as a prisoner at Guantánamo Bay, a fact even the US military does not dispute,” as the Associated Press explained in a recent article. He is 55 years old, and as the AP also noted, his weight “has nearly doubled” in his long imprisonment, “reaching more than 420 pounds at one point, and his health has deteriorated as a result, both his lawyers and government officials concede.”

Al-Sawah’s request has not yet been ruled on, but, noticeably, it follows the recent success achieved by lawyers for Ibrahim Idris, a Sudanese prisoner who is severely schizophrenic. In Idris’s case, the Justice Department decided not to contest his habeas corpus petition — a first for the DoJ lawyers who are notorious for defending every detention, even those of prisoners cleared for release in January 2010 by President Obama’s inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force. Al-Sawah’s case is more complicated, because, although Idris was cleared for release by the task force, al-Sawah was recommended for prosecution – a decision that made no sense, as logic dictates that he should be released as a reward for his extensive cooperation, documented in this Washington Post article from 2010.

When I wrote about Tariq al-Sawah last week, I promised I would revisit his story to include further information from two detailed articles written by freelance journalist Tom Dale and published in the Egypt Independent in July last year and March this year, which shed more light on his case.

In the article from last July, “Egypt’s last Guantánamo detainee in fight for freedom and truth,” Tom Dale ran through al-Sawah’s story, drawing in particular on discussions with al-Sawah’s brother Jamal, and with his military defense lawyer, Marine Lt. Col. Sean Gleason, who is still retained as a result of al-Sawah being put forward for a trial by military commission in 2008, even though those charges were later dropped.

Tom Dale began by explaining how Jamal al-Sawah described his brother as “a broken man, bereft of hope, vastly obese and severely depressed,” and Lt. Col. Gleason “also says he is innocent.” Gleason told him that the US government have “never provided any evidence to support their allegations.” Assigned to the case in August 2011, he “immediately applied for a speedy trial so that Sawah could ‘have his day in court,’” but the prosecution “summarily withdrew its charge — ‘conspiracy and material support for terrorism’ — and thereby returned Sawah to the legal limbo of indefinite detention.”

In his article, Tom Dale reported that both Lt. Col. Gleason and al-Sawah’s brother saw “only one possibility of breaking that limbo: a formal request by the Egyptian government to repatriate Sawah.” Noting, correctly, that it was “the route home for the vast majority of the 600 Guantánamo detainees who have been released,” Dale added that the two men “had several meetings at the justice and foreign ministries” to “lobby for such a request” just before his article was published, and in August, as Reuters reported, the Egyptian Foreign Ministry announced that President Morsi’s government has asked the US to release him, although that obviously didn’t happen.

Tariq al-Sawah’s story

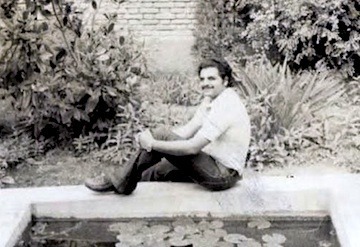

In his report, Tom Dale nevertheless pieced together al-Sawah’s story more throughly than in any previous account, noting how, in 1990, he left Alexandria where he had grown up, to work in Athens, and in 1992 he “became involved with a charity working in Croatia to assist Bosnian refugees fleeing sectarian violence.”

As Dale proceeded to explain, “The next year, he appears to have given up his charity work, and became involved with militias fighting against the ethnic cleansing in Bosnia. After fighting ended at the end of 1995, Sawah married a Bosnian woman and settled down in the country for which he had fought. They had a daughter.”

He added, “According to the letters that Sawah and his family used to send his brother’s family, these were happy times. They worked a small farm, and Sawah taught Arabic in a local orphanage and mosque.”

Unfortunately for al-Sawah, his happiness “was not to last.” During the Dayton peace accord in 1995, the Bosnian government had bowed to a Serbian demand for foreign fighters to be expelled from Bosnia-Herzegovina. This took many years to implement, but from 2000 onwards the expulsions began, and al-Sawah, “in no uncertain terms,” as Dale described it, “was told he had to leave.”

Lt. Col. Gleason explained what happened next: “When he was forced to leave in 2000, he was unable to come back here to Egypt because he had fought in the Bosnian conflict — he was afraid if he came back here, the secret police would arrest him. He tried to emigrate to other countries in Europe, but that wasn’t approved. One of the few countries that would accept him at that time was Afghanistan.”

On arrival in Afghanistan, as Dale described it, he “was immediately arrested, and kept in prison for several weeks.” When Taliban interrogators discovered his military experience in Bosnia, they told him that “they were fighting a similar conflict against the Northern Alliance,” Lt. Col. Gleason explained, adding, “You know, ‘the tribes of the Northern Alliance are raping women, and they’re murdering innocent people, and would you help us fight against them?’ Tariq agreed to do that. And that’s the fight he was in when he was captured less than a year later.”

As Dale described it, al-Sawah “was captured after having been injured by US cluster bombs while attempting to flee, unarmed, across the border to Pakistan.”

He added that, although al-Sawah “was close to networks of Islamist militants in both Bosnia and Afghanistan,” and also “trained Taliban fighters in the use of military explosives” and “attended a meeting in July 2001 at which Osama bin Laden was present,” his lawyers contend that there is “no basis to convict him of terrorism or taking up arms against the US.”

Commenting on the classified military files from Guantánamo that were released by WikiLeaks in 2011 (on which I worked as a media partner), Dale accurately noted that they “provide insight into what seems to be disregard for both fact and coherence on the part of US interrogators.” In al-Sawah’s case, the original charge sheet for his proposed trial by military commission claims that he “traveled to Afghanistan and joined Al-Qaeda to fight against the United States,” even though, as Dale noted, “when he traveled to Afghanistan there was no US presence there, and he had just left Bosnia, where there were several US bases.”

The charge sheet also stated that he had admitted to membership of Al-Qaeda, although Lt. Col. Gleason insisted that he “has always denied that he was ever associated with Al-Qaeda.”

Dale added that two documents from 2008 “state that Sawah was a member of Al-Qaeda for ‘approximately two years’ in Afghanistan, despite the fact that the same documents record that he spent just 14 months in the country before entering US custody.’ Crucially, both documents claim that he “developed a shoe-bomb prototype that could be used to bring down a commercial airliner,” similar to the one used by the failed “shoe bomber” Richard Reid. AsDale noted, however, former FBI special agent Ali Soufan explained in his book The Black Banners that “the allegation was known to be unsound since 2004,” as Dale put it.

Soufan wrote:

I found out that the military interrogators had said to him: “You’re an explosives expert. If you were to build a shoe bomb, how would you do it?” He had drawn them a diagram. That diagram constituted their “proof.” It turned out that it was a bad drawing, unrepresentative of the shoe bomb Reid used … They were novice interrogators and didn’t understand that you can’t just jump to those kinds of conclusions. They admitted that they had messed up.

Dale noted that Soufan “added an untrue allegation of his own — that Sawah ‘fought in the original Afghan Jihad,’” which cannot be the case because he spent that entire period, in the 1980s, in Alexandria.

One clearly unreliable claim exposed in the files is that al-Sawah fought in Chechnya, “even though the same document records his presence in either Bosnia or Afghanistan during the period of both Chechen wars.” It was also noted that his former membership of the Muslim Brotherhood provided “evidence of his ‘commitment’ to ideas that would mitigate in favor of his continued imprisonment.”

Tariq’s brother

In discussing Tariq al-Sawah’s case with his brother Jamal, Tom Dale discovered that Jamal as-Sawah, who has lived in the US for over 30 years, has also suffered because of his brother’s detention. In summer 2002, when he flew to Egypt for a holiday, as he has done regularly for the last 30-odd years, he was seized at the airport and taken to a holding facility. He told Dale, “I was in a solitary cell, handcuffed, hooded in the cell for ten days before interrogation. And then the interrogation started.” Dale added, “At this time, his brother’s arrest was not public knowledge,” indicating to Jamal that “the US authorities must have passed his name to the Egyptian security services.”

Although he was released, “the security services wouldn’t leave him alone, coming for him at home every few days,” as Dale put it. Jamal as-Sawah said, “They turned our life into a nightmare. The way they used to come at night, knock on the door, three o’clock in the morning, dragging me down the stairs, in front of everybody in the house. You hear any voice, you think they’re coming for you. Anybody knocks on the door, you jump, tell the kids to hide.”

Jamal noted that the visits “became much more polite after Jamal complained to an FBI officer around 2008, who promised he would intercede,” but in the US he is also “under constant surveillance.” He told Dale he had “become friendly with the FBI officers that tail him,” stating, “They’re watching your house, they’re watching your wife, they’re watching your phone, they’re watching your car. You’re watched everywhere you go.”

Tariq’s chronic health problems

Reflecting on Tariq al-Sawah’s health, Lt. Col, Gleason told Tom Dale that, on arrival at Guantánamo in 2002, he weighed around 91 kilograms (about 200 pounds), but he now weighs nearly 204 kilograms (about 450 pounds). He added that al-Sawah’s health “is in serious danger,” and that he “can barely walk 10 feet without having to sit down.” As Gleason put it, “He can’t even lay down on the bed because he’s so big that it would cut off his supply of oxygen, so he sleeps sitting up.” said Gleason.

Reflecting on Tariq al-Sawah’s health, Lt. Col, Gleason told Tom Dale that, on arrival at Guantánamo in 2002, he weighed around 91 kilograms (about 200 pounds), but he now weighs nearly 204 kilograms (about 450 pounds). He added that al-Sawah’s health “is in serious danger,” and that he “can barely walk 10 feet without having to sit down.” As Gleason put it, “He can’t even lay down on the bed because he’s so big that it would cut off his supply of oxygen, so he sleeps sitting up.” said Gleason.

The military lawyer also told Dale that he had “asked for his client’s medical records so that they can be shown to an independent doctor,” and had also askedfor him to be able to “see a US military obesity specialist.” Although both requests had been denied at the time, Gleason understood that a doctor had “recently assessed” al-Sawah and “her conclusion was that he was receiving negligent medical care.”

Dale added, sharply, “Even leaving medical care aside, Sawah’s obesity raises questions about the duty of care being exercised toward him.” As Lt. Col. Gleason explained, “They can control what he eats, they can control what he does, and yet he’s gained over 250 pounds.”

Dale also noted that Ali Soufan had suggested that al-Sawah “was brought ice cream to lift his mood during interrogations in 2004, despite the fact that he was already overweight.” and the Washington Post article in 2010 noted, as Dale put it, that “he was ‘enticed’ with takeout meals to participate in show questionings for visiting officials.” According to Lt. Col. Gleason, “based on his weight, based on his age, he’s at a high risk of death.”

Jamal as-Sawah stated that, when he “first saw his brother, over Skype, he was shocked.” As he said, “He was delirious, he was dizzy, he was so … huge. He aged so much.” He added, “Of course, he’d been detained without hope.”

For Jamal as-Sawah, the death of hope for Tariq is profoundly depressing, because he “was once a man with a great many hopes.” The family “grew up in Ibrahimiya, a working-class neighborhood of Alexandria that was full of Greeks, Armenians and Italians,” and their father, a government employee, whose salary “wouldn’t always stretch to the end of the month,” used to “take the two boys to hunt birds in what were once the marshlands of Semouha, and fish in the sea.” Jamal recalled it as “a happy childhood,” and one “full of laughter.”

He said that he and his brother “used to dream of growing up and living in the US, ‘American cars, blonde women.’” He added, as Dale described it, “Even now, when the two talk — as they are allowed to for an hour every three months — their conversation turns to that boyhood dream. The two had wanted to move their families to Florida, and go fishing for barracuda in the deep blue sea off the Florida Keys.”

Dale concluded his article with the following poignant paragraph: “Sawah will now never live in Florida, nor will he cast his line into the waters that separate Miami from Cuba and Guantánamo Bay. These days, he sits in his cell, on the other side. Reportedly, among the few pleasures he is allowed, he paints pictures of the sea.”

In a follow-up article in March 2013, “Detention continues for last Egyptian in Guantánamo, despite deteriorating health,” Tom Dale noted that there were fears for his life, that the authorities were “refusing specialist medical treatment, or even to allow his lawyer to view his medical records,” even while “developments in his legal case provide hope that he may one day be released.”

He also noted that, following the Egyptian government’s official request for al-Sawah’s release last August, the government had hired a lawyer, Robert Tucker, to formally request a hearing for him. Dale explained that Tucker “was retained in December, but was unable to start work until funding was released to him on 25 January.”

On the legal front, al-Sawah still has a habeas corpus petition pending, although a request for him to be “freed on an interim basis, pending a Periodic Review Board hearing,” was turned down by a US court last November.

Turning to his medical problems, Dale confirmed that he is “morbidly obese,” and that he is “beset with respiratory and heart complications,” and is “at significant risk” of death, according to a doctor. Although the US authorities “have refused him appropriate treatment, according to his doctor and lawyers, and continue to withhold his medical records,” Dr. Sondra Crosby, an associate professor of medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine and Public Health, has been able to examine al-Sawah on two occasions. Last October, in a letter to one of al-Sawah’s lawyers, which was provided to officials at Guantánamo and filed in a federal court the same month, she wrote that his “extreme obesity” has left him at “an increased risk of death from all causes.”

Noting that he has “a body mass index of more than 40,” Dr. Crosby also noted that al-Sawah “is so obese that he cannot sleep lying down, lest the soft tissue from his neck block his airway,” as previously reported, adding that he is “at great risk of coronary artery disease and heart failure,” and his “functional status is extremely limited.” Dale added, “Associated with these conditions, and with his long internment, he is described as depressed and hopeless, with impaired neurocognitive functionality.”

Dr. Crosby also noted that, to her knowledge, al-Sawah “has not received appropriate specialized evaluation or treatment for his condition.” Lt. Col. Gleason, who “has the appropriate security clearance” to view his clients’ medical records, but has not been allowed to do so, despite first submitting a request in August 2011, told Dale that he has “received no official explanation.” Gleason also explained that he had requested “a specialist physician to develop a treatment plan for his client,” but that this proposal “has been ignored by the military commander at Guantánamo,” and he is “unaware of any steps” being taken to treat his client’s “life-threatening heath concerns.”

He added that he had been told that the prisoners “are fed the same food as the guard force, leading him to believe Sawah’s weight problem is underpinned by other factors.” He cited references to claims that al-Sawah “was fed unhealthily at times to encourage compliance,” as in the Washington Post report in 2010, which, drawing on a statement made by an unnamed US official, noted, “the overweight Egyptian was enticed with takeout from the Subway franchise on the base.”

Dale added that Ali Soufan, mentioned above, had describing al-Sawah in 20004, who he interviewed him, as “overweight and happiest when we’d bring him ice cream.”

By email, Gleason told Dale, “It is clear to me that Sawah’s health has been declining over the 18 months I’ve been seeing him. It doesn’t appear that his weight has increased or decreased during the time I’ve been meeting with him, but his energy levels have been steadily declining.”

He added that al-Sawah “is also experiencing memory loss,” noting that his daughter and one of his sisters “spoke to him via Skype early last month from Alexandria and, his brother Jamal says, his sister had the impression that he is in a worse condition than on any of the previous occasions on which she has spoken to him in captivity.”

The Bosnian connection

Dale also noted that in February this year, Darryl Li, an anthropologist at Columbia University, interviewed a Bosnian man who had fought alongside al-Sawah in the Mujahideen Brigade in Bosnia in the 1990s — which, it should be noted, received support from the US — and that Li “agreed to put a question to the Bosnian source on behalf of Egypt Independent.” This source stated, “He had a big body, big hands, big hair. He looked dangerous, but was actually a very good person. He didn’t get into discussions much, was quiet. He found himself in jihad because it was a simple challenge. [He] used to say, ‘You should be patient until the action.’”

He added, “I’m absolutely sure that he’s not a guy who should be in Guantánamo … Maybe he’s a dangerous-looking guy [but] he wants to do some practical good in the world.”

The Bosnian said that he “last saw Sawah at Sarajevo airport as he left the country for the last time,” en route to Afghanistan as he was unable to return home. 13 years later, Lt. Col. Gleason appealed for his long imprisonment to be brought to an end. Noting that his client “has now been held by the United States for over 11 years without being tried or convicted of any crime,” Gleason said, “He looks forward to having an opportunity to clear his name and to be reunited with his family in Egypt. Based on his declining health condition, he hopes that day comes soon.”

Hopefully, the Periodic Review Board will pay attention to all the cases that come before them, and will recognize why Tariq al-Sawah’s imprisonment should come to an end.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

October 19, 2013

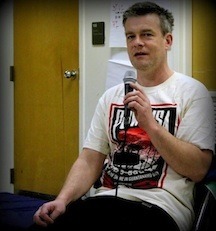

An Interview with Guantánamo Expert Andy Worthington for The Prisma, An Online Multi-Cultural Newspaper

Recently, I was interviewed by a young Spanish journalist, Francisco Castañón, for The Prisma, an online multicultural newspaper. The interview is here, and in it I explained how I came to write about Guantánamo, for my book The Guantánamo Files, and I also ran through aspects of the story of Guantánamo, past, present and future to help to explain why the prison is still open, and why its continued existence is so monstrously unjust. I hope you find it useful.

Recently, I was interviewed by a young Spanish journalist, Francisco Castañón, for The Prisma, an online multicultural newspaper. The interview is here, and in it I explained how I came to write about Guantánamo, for my book The Guantánamo Files, and I also ran through aspects of the story of Guantánamo, past, present and future to help to explain why the prison is still open, and why its continued existence is so monstrously unjust. I hope you find it useful.

Andy Worthington, Guantánamo and the survivors

By Francisco Castañón, The Prisma, October 13, 2013

Since Obama took power in 2009, he has freed 73 of the prisoners in Guantánamo, of the 240 prisoners who were held when he took office. Three others have died. But in the last three years Congress approved new laws which made the promise to close the prison even more difficult to fulfill.

Former prisoners like Omar Deghayes, Moazzam Begg and Murat Kurnaz have made public the extreme conditions which the prisoners are still suffering.

Kurnaz told how difficult it was to live in a solitary confinement cell, to keep himself alive in such a small space with just enough air to breathe.

Besides the international criticisms that the US government’s treatment of the prisoners is unlawful, the prison is very expensive to maintain: 454 million dollars a year, a figure which most Americans do not approve of.

Andy Worthington is an independent investigative journalist, writer, photographer, film-maker and political activist. He began his investigation for The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison in 2006.

He talked to The Prisma about his book and the present situation in the military camp.

The Prisma: Why is Guantánamo Bay still open, even though President Obama said in 2009 he was going to shut down the detention camp?

Andy Worthington: First of all, let me say that there are currently 164 prisoners, although 84 of them were approved for transfer out of the prison by a task force that President Obama established when he took office. This was high-level, involving officials in all the government departments and the intelligence agencies. They spent 2009 meeting every week, and they went through the files of all the prisoners. They made decisions about whether they were recommended for trial, recommended for release, or for ongoing detention without charge or trial in some cases.

So President Obama has released 70 of the 156 prisoners cleared for release by the task force, but for the last three years he has released very few prisoners, mainly because Congress passed new laws making it very difficult for him to do that, but also because he couldn’t be bothered to spend the political capital to do something that could make him unpopular in Congress.

Earlier this year, there were 86 men still held about whom the US government said, “we don’t want to hold these guys forever, we don’t want to put them on trial,” but they are still stuck in Guantánamo. In August Obama released two of them, so now there are 84. Over half of the people held in Guantánamo, the US government says it doesn’t want to carry on holding.

The Prisma: Why did you decide to write about Guantánamo?

Andy Worthington: Like many other people, I realized when Guantánamo opened, on the 11th of January 2002, that something had gone badly wrong. The United States was attacked horribly on September 11, 2001, but I think there was a kind of desire for revenge that was driving the US in response, and the government ended up picking people up randomly and bringing them to Guantánamo.

When the prison opened, it was unnerving to see the prisoners wearing orange jumpsuits, with blacked-out goggles on their eyes, in the famous photos that were released by the US government, which showed the prisoners cowering on the ground with soldiers shouting on them. To everybody apart from the Americans those were pretty horrible photos.

In 2004 the first British prisoners were released, and also in 2005, and particularly at that time people start hearing from English speaking British citizens about the kind of stuff that happened to them. My interest in Guantánamo grew as I heard these stories, and later in 2005 I started researching Guantánamo to find the stories of the released prisoners, to find what news reports there were about them. At that time the prison had been open for three and a half years but the Americans still hadn’t said who they were holding.

Then the US government lost a lawsuit and was compelled to release 8,000 pages of documents, including the names and nationalities of the prisoners, the allegations against them and the transcripts of tribunals held to decide if they were “enemy combatants.” The whole tribunal process was unjust but the transcripts provided an insight into who the prisoners were, and I used all this information as the basis for my book The Guantánamo Files.

The Prisma: When did the US government release that information?

Andy Worthington: It was in March, April and May 2006.

The Prisma: Did you meet some of the prisoners?

Andy Worthington: When I was initially doing my research I didn’t. I was in touch with a few lawyers who represented Guantánamo prisoners at the time, but as the years have passed I have been in touch with more of the former prisoners. In particular, I got to know Omar Deghayes very well, and he and the former prisoner Moazzam Begg appeared in “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo,” the documentary film that I co-directed.

The Prisma: What can you tell us about the prisoners’ experiences?

Andy Worthington: It is quite extraordinary how some of these people survive what they went through. There are a number of ways that you can react to being in prison. Some people chose a pattern of non-resistance, so everything they were told to do they did. Other people couldn’t stand what was happening so they fought back against them, and if you do that they treat you very badly.

The main thing that a lot of people went through repeatedly was isolation, being put into isolation cells for more than 30 days at a time. Murat Kurnaz was a German prisoner, of Turkish origin, who explained in his autobiography how there was very little air in the cells. He explained how all the time in isolation he was lying on the floor breathing in a very shallow manner just to stay alive.

The US authorities also specifically had some techniques that they used to break people, because they thought that if they were punishing people they were going to get them to collaborate. However, people with experience dealing with interrogation will tell you that trying to break people is not the way to get them to collaborate with you.

The Prisma: How much money does it cost to the USA to maintain Guantánamo?

Andy Worthington: Everything has to be taken there from the US mainland, so it’s insanely expensive. The basic running cost is around 1.2 million dollars per year per prisoner, which is insane.

So, you’ve got 84 cleared prisoners at the moment, and that’s costing you 100 million dollars every year to hold guys that you said you don’t want to hold in the first place.

The Prisma: How can the international community allow the US government to do that in Guantánamo?

Andy Worthington: The problem is that there is no mechanism in place beyond complaining. The International Criminal Court is not recognized by the United States, so George W. Bush, Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld cannot be taken to The Hague and held accountable for their actions, which, of course, include torture, which is illegal.

Another problem is getting other countries to cooperate, because many dozens of other countries were complicit in the “war on terror,” allowing US planes to use their airports or airspace when prisoners were kidnapped, or cooperating through intelligence gathering.

The Prisma: Is there any official investigation into the treatment of the prisoners in Guantánamo?

Andy Worthington: No, sadly, even though between February 2002 and June 2006 the US government behaved like there were no rules about how you treated prisoners, as though you could hold people without any rights.

Eventually, there was an internal investigation in the Department of Justice, into the behaviour of John Yoo and Jay Bybee. Yoo, as a lawyer in the Office of Legal Counsel, which is supposed to provide impartial legal advice to the executive branch, wrote memos in 2002 that said that the torture wasn’t torture — so that US operatives could engage in torture with impunity.

The ethics investigation concluded that Yoo and his boss Bybee had been guilty of professional misconduct, which was quite a serious conclusion, but President Obama allowed a Justice Department fixer to rewrite that conclusion. He said that everybody was under a lot of pressure, and they just exercised poor judgment, meaning that no sanctions were possible. That was pretty shocking.

The Prisma: How did the reports of how they treated the prisoners come out to the public?

Andy Worthington: It is interesting because the main thing happened in 2004, after the Abu Ghraib scandal first became public. Somebody inside the Bush administration couldn’t accept what was happening and leaked Yoo’s “torture memo” to the media. So here you have a senior lawyer, very close to Dick Cheney, the Vice President of the Unites States, saying torture isn’t torture unless it rises to the level of an organ failure or even death. Yoo lifted this from a medical insurance document, and cut and pasted into what he was preparing about torture. So in 2004 that document was leaked, and that provided a very big insight into the treatment of prisoners.

Other insights came through reporters working on aspects of the stories, but one of the most important sources was the prisoners themselves — either former prisoners or prisoners still held who told their accounts to their lawyers after the Supreme Court ruled in 2004 that they had habeas corpus rights, and lawyers were allowed to visit them.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

October 18, 2013

Although Two Men Weigh 75 Pounds or Less, Guantánamo Prisoner Moath Al-Alwi Says, “We Will Remain on Hunger Strike”

For six months, Guantánamo managed to be in the news on a regular basis, as a prison-wide hunger strike succeeded in pricking the consciences of the mainstream media. Unfortunately, since the numbers of those involved fell (from 106 on July 10 to 53 a month later), the media largely moved on. At the height of the hunger strike, 46 prisoners were being force-fed, a process condemned by medical professionals, but although the US authorities state that just 15 prisoners are currently on a hunger strike, all of them are being force-fed.

For six months, Guantánamo managed to be in the news on a regular basis, as a prison-wide hunger strike succeeded in pricking the consciences of the mainstream media. Unfortunately, since the numbers of those involved fell (from 106 on July 10 to 53 a month later), the media largely moved on. At the height of the hunger strike, 46 prisoners were being force-fed, a process condemned by medical professionals, but although the US authorities state that just 15 prisoners are currently on a hunger strike, all of them are being force-fed.

Moreover, as was explained this week in an op-ed for Al-Jazeera America by Moath al-Alwi, a Yemeni prisoner also known as Moaz al-Alawi, the men who are still hunger striking have no intention of giving up, even though, as al-Alwi explains, some have lost so much weight that their appearance would send shockwaves around the world if a photograph were to be leaked. As he states, “one of my fellow prisoners now weighs only 75 pounds. Another weighed in at 67 pounds before they isolated him in another area of the prison facility.”

The situation for the prisoners who are still on a hunger strike is clearly horrific. As al-Alwi states in his op-ed, which I’m posting below, the force-feeding remains “painful and horrific,” as it was when he described it previously, in another op-ed for Al-Jazeera in July that I’m also posting below.

For the men still on a hunger strike, an adequate response from President Obama would be to release all the prisoners who were cleared for release by the president’s interagency Guantánamo Review Task Force in January 2010 but are still held — currently 84 of the remaining 164 prisoners. Despite promising to resume releasing cleared prisoners in a major speech on national security issues in May, just two prisoners have been released in the last five months.

Moath al-Alwi is not one of those cleared for release, and in fact he was one of 48 prisoners recommended for ongoing detention without charge or trial by the task force nearly four years ago. Two of these men subsequently died. It was recently announced that long-promised reviews for these men will begin soon, as well as for 25 others previously recommended for trials, to decide whether they should continue to be held, but it is unclear if the administration is genuinely interested in critically revisiting previous decisions. Al-Alwi, for example, had his habeas corpus petition turned down in January 2009 and his appeal was turned down in July 2011, even though, all along, as Judge Richard Leon, who ruled on his habeas petition, noted, there has never been any evidence of him “actually using arms against US or coalition forces.”

Guantánamo inmate: ‘We will remain on hunger strike’

By Moath al-Alwi, Al-Jazeera America, October 15, 2013

I write this after my return from the morning’s force-feeding session here at Guantánamo Bay. I write in between bouts of violent vomiting and the sharp pains in my stomach and intestines caused by the force-feeding.

The US government now claims that, among the 164 prisoners at Guantánamo, there are fewer than two dozen hunger strikers, down from well over 100 back in August. I am one of those remaining hunger strikers. I have been on hunger strike for almost nine months, since February.

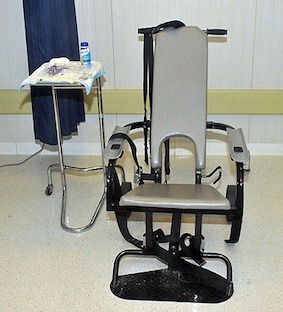

The guards dragged me out of my cell at around 8:20 a.m. As they took me, shackled, past the other cells and toward the restraint chairs — my brothers and I call them torture chairs — I could barely breathe because of the smell. Some of my brothers are now tainting the walls of their cells and blocking the air-conditioning vents with their own feces in protest.

The force-feeding remains as painful and horrific as the last time I described it. The US military prison staff’s intent is to break our peaceful hunger strike. The result can be read all over my body. It is visible on my bloodied nose and in my nostrils, swollen shut from the thick tubes the nurses force into them. It is there on my jaundiced skin, because I am denied sunlight and sleep. It is there, too, in my bloated knees and feet and my ailing back, wrecked from prolonged periods spent in the torture chair and from the riot squad’s beatings. You can even hear it in my voice: I can barely speak because they choke me every time they strap me into the chair.

No form of pressure is too cruel or petty for our captors. They have deprived me of medication for as long as I remain on hunger strike. They have also taken away electric razors necessary for proper grooming and require all hunger strikers to share a single razor, despite the serious health risks that this poses. A rash spread among some of my fellow prisoners because of this measure by prison authorities.

Not even our rare calls with our families are held sacred. Three weeks ago, as the guards took me to a telephone call with my family, they subjected me to a humiliating and unnecessary search of my private areas. I resisted peacefully, as best I could, and tried to reason with the guards. To avoid these humiliating searches, some of my fellow hunger strikers have abstained from calls with their loved ones or meetings with their attorneys.

Many brothers have ended their hunger strikes because of these brutal force-feeding practices and the cruel punishment inflicted by the prison guards and military medical staff.

Others have chosen to suspend their hunger strikes to give President Barack Obama time to make good on his renewed promise to release Guantanamo prisoners.

But as for my brothers and me, we will remain on hunger strike. We pray that the next thing we taste is freedom. It may be hard to believe, but one of my fellow prisoners now weighs only 75 pounds. Another weighed in at 67 pounds before they isolated him in another area of the prison facility. These men survive only by the grace of God. May God continue to sustain us all until we achieve our goal of justice.

Editor’s Note: Moath al-Alwi [is] a Yemeni national who has been in US custody since 2002. He was one of the very first prisoners moved to Guantánamo Bay detention camp, where the US military assigned him Internment Serial Number (ISN 028). The article was translated from the Arabic by his attorney, Ramzi Kassem.

My life at Guantánamo

By Moath al-Alwi, Al-Jazeera, July 7, 2013

A detainee at the US prison explains that hunger striking is the only way left to cry out for life, freedom and dignity.

A month ago, the guards here at Guantánamo Bay gave me an orange jumpsuit. After years in white and brown, the colours of compliant prisoners, I am very proud to wear my new clothes. The colour orange is Guantánamo’s banner. Anyone who knows the truth about this place knows that orange is its only true colour.

My name is Moath al-Alwi. I have been a prisoner of the United States at Guantánamo since 2002. I was never charged with any crime and I have not received a fair trial in US courts. To protest this injustice, I began a hunger strike in February. Now, twice a day, the US military straps me down to a chair and pushes a thick tube down my nose to force-feed me.

When I choose to remain in my cell in an act of peaceful protest against the force-feeding, the prison authorities send in a Forced Cell Extraction team: six guards in full riot gear. Those guards are deliberately brutal to punish me for my protest. They pile up on top of me to the point that I feel like my back is about to break. They then carry me out and strap me into the restraint chair, which we hunger strikers call the torture chair.

A new twist to this routine involves the guards restraining me to the chair with my arms cuffed behind my back. The chest strap is then tightened, trapping my arms between my torso and the chair’s backrest. This is done despite the fact that the torture chair features built-in arm restraints. It is extremely painful to remain in this position.

Even after I am tied to the chair, a guard digs his thumbs under my jaw, gripping me at the pressure points and choking me as the tube is inserted down my nose and into my stomach. They always use my right nostril now because my left one is swollen shut after countless feeding sessions. Sometimes, the nurses get it wrong, snaking the tube into my lung instead, and I begin to choke.

The US military medical staff conducting the force-feeding at Guantánamo is basically stuffing us prisoners to bring up our weight — mine had dropped from 168 pounds to 108 pounds, before they began force-feeding me. They even use constipation as a weapon, refusing to give hunger strikers laxatives despite the fact that the feeding solutions inevitably cause severe bloating.

If a prisoner vomits after this ordeal, the guards immediately return him to the restraint chair for another round of force-feeding. I’ve seen this inflicted on people up to three times in a row.

Even vital medications for prisoners have been stopped by military medical personnel as additional pressure to break the hunger strike.

Those military doctors and nurses tell us that they are simply obeying orders from the colonel in charge of detention operations, as though that officer were a doctor or as if doctors had to follow his orders rather than their medical ethics or the law.

But they must know that what they are doing is wrong, else they would not have removed the nametags with their pseudonyms or numbers. They don’t want to be identifiable in any way, for fear of being held accountable someday by their profession or the world.

I spend the rest of my time in my solitary confinement cell, on 22-hour lockdown. The authorities have deprived us of the most basic necessities. No toothbrushes, toothpaste, blankets, soap or towels are allowed in our cells. If you ask to go to the shower, the guards refuse. They bang on our doors at night, depriving us of sleep.

They have also instituted a humiliating genital search policy. I asked a guard why. He answered: “So you don’t come out to your meetings and calls with your lawyers and give them information to use against us.”

But the prisoners’ weights are as low as their spirits are high. Every man I know here is determined to remain on hunger strike until the US government begins releasing prisoners.

Those of you on the outside might find that difficult to comprehend. My family certainly does. If I’m lucky, I’m allowed four calls with them each year. My mother spent most of my most recent call pleading with me to stop my hunger strike. I had only this to say in response: “Mom, I have no choice.” It is the only way I have left to cry out for life, freedom and dignity.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

Today, As Guantánamo Hunger Strikers Seek Relief in Washington Appeals Court, A US Protestor Will Be Force-Fed Outside

Today, at 11 am Eastern time (4 pm GMT), lawyers for three prisoners still held at Guantánamo Bay — including the last British resident, Shaker Aamer — will ask the appeals court in Washington D.C. to order the government to end the force-feeding of prisoners, denounced by the World Medical Association and the UN, in which, as the legal action charity Reprieve explained in a press release, “a detainee is shackled to a specially-made restraint chair and a tube is forced into his nostril, down his oesophagus, and through to his stomach.”

Today, at 11 am Eastern time (4 pm GMT), lawyers for three prisoners still held at Guantánamo Bay — including the last British resident, Shaker Aamer — will ask the appeals court in Washington D.C. to order the government to end the force-feeding of prisoners, denounced by the World Medical Association and the UN, in which, as the legal action charity Reprieve explained in a press release, “a detainee is shackled to a specially-made restraint chair and a tube is forced into his nostril, down his oesophagus, and through to his stomach.”

At the height of the prison-wide hunger strike at Guantánamo this year, 46 men were being force-fed. That total has now fallen to 15, but twice a day those 15 men are tied into restraint chairs, while liquid nutrient is pumped into their stomachs via a tube inserted through their nose.

As well as Shaker Aamer, the other petitioners in the appeal are Abu Wa’el Dhiab, a Syrian, and Ahmed Belbacha, an Algerian. All three were cleared for release by President Obama’s inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force in January 2010, and are represented by Reprieve and Jon B. Eisenberg.

In July, Judge Gladys Kessler, ruling on the motion submitted by Abu Wa’el Dhiab, — which, nevertheless, she turned down because of a legal precedent involving Guantánamo and force-feeding — described force-feeding as “painful, humiliating, and degrading.” She pointed out that Abu Wa’el Dhiab had “set out in great detail in his papers what appears to be a consensus that force-feeding of prisoners violates Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which prohibits torture or cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment,” and also explained that “the President of the United States, as Commander-in-Chief, has the authority — and power — to directly address the issue of force-feeding of the detainees at Guantánamo Bay.”

Judge Rosemary Collyer, who ruled against the motion submitted by Shaker Aamer, Ahmed Belbacha and Nabil Hadjarab (who has since been released), was less sympathetic, but Reprieve and Jon B. Eisenberg argue in the appeal (available here) that, although the government “has attempted to argue that the issue does not lie within the court’s jurisdiction,” this is wrong, because the force-feeding that is taking place is a “deprivation of substantial rights,” and “a seizure of [the detainee’s] internal organs through the forcible invasion of his gastro-intestinal tract.”

Furthermore, in response to the government’s claim that force-feeding is “humane,” the appeal notes that the Ninth Circuit court in California “recently upheld California’s legislative ban on force-feeding of ducks and geese to produce foie gras, deeming the ban to be a lawful pursuit of the state’s ‘interest in preventing animal cruelty.” The lawyers for the men in Guantánamo note, “The irony of protecting ducks and geese from a practice that is inflicted on human beings at Guantánamo Bay speaks volumes.”

As Reprieve described it, the appeal also “argues that the detainees were denied their right to religious free exercise because authorities at the prison deprived them of the ability to conduct communal prayer unless they stopped hunger striking.”

While the appeal is being heard, Andrés Conteris, an activist with the campaigning group Witness Against Torture, will be force-fed on the steps of the court.

Conteris is on the 103rd day of a fast which he began on on July 8 to protest about the force-feeding of hunger-striking prisoners not only in Guantánamo, but also in Pelican Bay Prison in California, where prisoners are held in horrendous long-term isolation in the notorious Secure Housing Units (SHUs) and are challenging the system through regular hunger strikes.

Conteris, who has lost 57 pounds since his fast began, says, “Force-feeding is torture. I wish to make visible what the US government is perpetrating against prisoners in Guantánamo and to remind the world that indefinite detention continues.” The 52-year old activist has been force-fed at the White House, in Oakland, California, and at US embassies in Uruguay and Argentina. He describes it as follows: “The nasal tube feeding feels like endless agony. It feels like I’m drowning.”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

October 15, 2013

Lawyers Seek Release from Guantánamo of Tariq Al-Sawah, an Egyptian Prisoner Who is Very Ill

Two weeks ago, when lawyers in the US Justice Department decided — for the first time — not to contest the habeas corpus petition of a prisoner in Guantánamo, it was a cause for celebration. The man in question, Ibrahim Idris, a Sudanese man in his early 50s, is severely mentally ill, as he suffers from schizophrenia, and is also morbidly obese. As his lawyer Jennifer Cowan explained, “Petitioner’s long-term severe mental illness and physical illnesses make it virtually impossible for him to engage in hostilities were he to be released, and both domestic law and international law of war explicitly state that if a detainee is so ill that he cannot return to the battlefield, he should be repatriated.”

Two weeks ago, when lawyers in the US Justice Department decided — for the first time — not to contest the habeas corpus petition of a prisoner in Guantánamo, it was a cause for celebration. The man in question, Ibrahim Idris, a Sudanese man in his early 50s, is severely mentally ill, as he suffers from schizophrenia, and is also morbidly obese. As his lawyer Jennifer Cowan explained, “Petitioner’s long-term severe mental illness and physical illnesses make it virtually impossible for him to engage in hostilities were he to be released, and both domestic law and international law of war explicitly state that if a detainee is so ill that he cannot return to the battlefield, he should be repatriated.”

As I explained in my most recent article, “Some Progress on Guantánamo: The Envoy, the Habeas Case and the Periodic Reviews,” it is disgraceful that the Justice Department lawyers responsible for dealing with the Guantánamo prisoners’ cases have “vigorously contested every petition as though the fate of the United States depended on it.” I have long been outraged that, in particular, “petitions have been fought even when the men in question have been cleared for release by President Obama’s Guantánamo Review Task Force,” as I described it.

I added:

I am unable to explain why there has been no cross-referencing of cases between the task force (which involved officials from the Justice Department) and the Civil Division of the DoJ, or why Attorney General Eric Holder has maintained the status quo, and no other senior official, up to and including the President, has acted to address this troubling lack of joined-up thinking. However, it is to be hoped that it signals the possibility for further successful challenges by prisoners who are ill — as well as opening up the possibility for cleared prisoners to call for their release through the habeas process.

As I also mentioned, the Associated Press followed the news about the Justice Department refusing to contest Ibrahim Idris’ habeas petition (and Judge Royce Lamberth’s subsequent ruling, ordering his release) by reporting that, as I described it, “lawyers for another severely ill prisoner, Tariq al-Sawah (aka Tarek El-Sawah), an Egyptian, are also seeking his release, and lawyers for Saifullah Paracha, a Pakistani who is very ill with cardiac problems, also spoke to the AP about their client’s case. Noticeably, neither man was cleared for release by the task force, but it is clear their illnesses are not something that the authorities can endlessly ignore.”

As the AP explained, Saifullah Paracha, who is 66 years old, “has a heart condition serious enough that the government brought a surgical team and a mobile cardiac lab” to Guantánamo to treat him, although he “refused the treatment because he didn’t trust military medical personnel.” As I explained in an article in 2007, Paracha is regarded as an al-Qaeda sympathiser by the US, but he has always disputed their arguments, claiming that he is nothing more than a businessman.

Tariq al-Sawah, an explosives expert for al-Qaeda who became disillusioned with his former life and has cooperated extensively with the authorities in Guantánamo, is also seriously ill. As the AP described it, he is “in terrible shape after 11 years as a prisoner at Guantánamo Bay, a fact even the US military does not dispute.” 55 years old, his weight “has nearly doubled” in his long imprisonment, “reaching more than 420 pounds at one point, and his health has deteriorated as a result, both his lawyers and government officials concede.”

Tariq al-Sawah, an explosives expert for al-Qaeda who became disillusioned with his former life and has cooperated extensively with the authorities in Guantánamo, is also seriously ill. As the AP described it, he is “in terrible shape after 11 years as a prisoner at Guantánamo Bay, a fact even the US military does not dispute.” 55 years old, his weight “has nearly doubled” in his long imprisonment, “reaching more than 420 pounds at one point, and his health has deteriorated as a result, both his lawyers and government officials concede.”

His lawyers — and doctors they were allowed to bring to Guantánamo to examine him — paint what the AP described as “a dire picture” of “a morbidly obese man with diabetes and a range of other serious ailments,” who “is short of breath, barely able to walk 10 feet, unable to stay awake in meetings and faces the possibility of not making it out of prison alive.”

Marine Lt. Col. Sean Gleason, a military lawyer appointed to represent him when he was charged in the military commissions at Guantánamo in 2008 (and who still represents him even though the charges were subsequently dropped), told the AP, “We are very afraid that he is at a high risk of death, that he could die at any moment.”

In August, his lawyers filed an emergency motion with a federal court in Washington D.C., asking a judge to order the military to provide “adequate” medical care. As the AP described it, this includes “additional tests for possible heart disease and a device to help him breathe because of a condition they say is preventing his brain from receiving enough oxygen.”

As the AP added, the judge hasn’t yet ruled on the motion, but the request about medical care is secondary to a request for the US to release him. As with Ibrahim Idris’s case, they state that “his health is too poor for him to pose any kind of threat.” As Lt. Col. Gleason noted, “It boggles the mind that they are putting up a fight on releasing him.”

Callously, Justice Department lawyers responded by stating that, although al-Sawah “is currently in poor health, his life is not in imminent danger.”

The AP also noted that al-Sawah, who is average height (5′ 10″), weighed 215 pounds when he arrived at Guantánamo in May 2002, although another of his lawyers, Mary Petras, told the AP “he was obese by the time she first met him in March 2006.”

His lawyers hope that a judge will grant their motion, but if not they hope that the newly established Periodic Review Boards (for 71 prisoners, out of 164 in total, who have not been cleared for release) will reverse the decision, made in January 2010 by President Obama’s inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force, to recommend him for prosecution.

As the AP noted, al-Sawah has high-level support for his claim, because he has “received letters of recommendation from three former Guantánamo commanders,” which they describe, accurately, as “a rare string of endorsements.”

In one letter, retired Army Maj. Gen. Jay Hood called him “a unique prisoner” who was “unlike the violent Islamic extremists who formed much of the population at Guantánamo.” Another, Rear Adm. David Thomas, noted his “restricted mobility due to obesity and other health issues.” Adm. Thomas recommended his release in his Detainee Assessment Brief in September 2008, which was released by WikiLeaks in 2011, and only later contradicted by the task force.

“Most striking,” as the AP noted, is “a letter from an official whose name and job title are redacted for security reasons,” who spent several hours a week with al-Sawah over the course of 18 months. He noted that al-Sawah has been “friendly and cooperative” with US personnel, and stated, “Frankly, I felt Tarek was a good man on the other side who, in a different world, different time, different place, could easily be accepted as a friend or neighbor.”

These are powerful statements in support of al-Sawah, but what I find just as persuasive — and which is only alluded to above, and was not mentioned at all by the AP — is the fact that, back in March 2010, in an important article for the Washington Post, Peter Finn reported that al-Sawah and another prisoner, Mohamedou Ould Slahi, a Muaritanian, “had become two of the most significant informants” in Guantánamo. As a result, they were “housed in a little fenced-in compound at the military prison, where they live[d] a life of relative privilege — gardening, writing and painting — separated from other detainees in a cocoon designed to reward and protect.”

What was particularly shocking about this was the refusal of the authorities to reward the men for their extensive cooperation by releasing them.

As Finn noted:

Some military officials believe the United States should let them go — and put them into a witness protection program, in conjunction with allies, in a bid to cultivate more informants.

“I don’t see why they aren’t given asylum,” said W. Patrick Lang, a retired senior military intelligence officer. “If we don’t do this right, it will be that much harder to get other people to cooperate with us. And if I was still in the business, I’d want it known we protected them. It’s good advertising.”

Peter Finn also noted that a military official at Guantánamo at the time of his article had “suggested that that argument was fair,” although he stated that it was “a hard-sell argument around here.”

The only possible acknowledgement of al-Sawah’s status referred to in the recent discussions came at one point in the AP article, when it was noted that, although he had “faced charges of conspiracy and providing material support for terrorism,” the government “withdrew those charges and told his lawyers that prosecutors had no intention of filing them again for reasons that have not been made public.”

As those charges were dropped, not to be reinstated, despite the task force’s recommendation that he be prosecuted, those dealing with al-Sawah’s case should acknowledge W. Patrick Lang’s comments about informants, as well as accepting that some prisoners are too ill to hold.

In addition to the severely ill prisoners under discussion at the moment (Ibrahim Idris, Tariq al-Sawah and Saifullah Paracha), there are undoubtedly other prisoners who are severely ill. I know of a handful of cases, but do not feel it appropriate to discuss them unless their lawyers believe it to be useful.

As the AP also noted, ”two prisoners have died from natural causes — one from a heart attack, the other from colon cancer,” and several prisoners have “raised medical complaints” related to their participation in this year’s prison-wide hunger strike.

Cori Crider, the Strategic Director of Reprieve, the London-based legal action charity whose lawyers represent 15 Guantánamo prisoners, said, “There are a whole slew of people with a whole slew of serious health problems.”

Note: In an article to follow, I will analyze Tariq al-Sawah’s story as reported in the last 15 months in the Egyptian media, and specifically by Tom Dale in the Egypt Independent.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.