Andy Worthington's Blog, page 126

November 20, 2013

From Guantánamo, Shaker Aamer Says, “Tell the World the Truth,” as CBS Distorts the Reality of “Life at Gitmo”

Please sign the petition, on the Care 2 Petition Site, calling for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison.

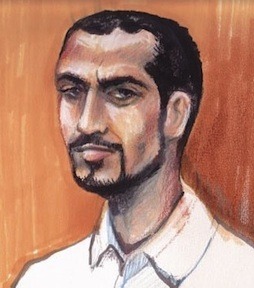

In September 2013, a team from CBS News’ “60 Minutes” show traveled to Guantánamo, producing a 13-minute show, “Life at Gitmo,” broadcast on November 17, which was most notable for featuring the voice of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, who shouted out while the presenter, Lesley Stahl, and her guide, Col. John Bogdan, the prison’s warden, were walking though one of the cell blocks.

Shaker shouted out, “Tell the world the truth. Please, we are tired. Either you leave us to die in peace — or either tell the world the truth. Open up the place. Let the world come and visit. Let the world hear what’s happening. Please colonel, act with us like a human being, not like slaves.”

He added, “You cannot walk even half a meter without being chained. Is that a human being? That’s the treatment of an animal. It is very sad what is happening in this place.”

The video is below, and the segment featuring Shaker begins about three minutes in:

Following Shaker’s cry for help, the CBS team at least bothered to investigate his story, discovering that he is one of 84 of the remaining 164 prisoners who were cleared for release by a high-level, inter-agency task force that President Obama established soon after taking office in 2009, and also that he was cleared for release by a military review board under President Bush. Lesley Stahl noted in the broadcast that, earlier this year, the British Prime Minister David Cameron had raised his case with President Obama at a G8 summit, and also noted that the British government had repeatedly called for his return to the UK.

She evidently found it troubling that he was still held, as the following exchange with Clive Stafford Smith, the director of the London-based legal action charity Reprieve, and one of Shaker Aamer’s lawyers, shows:

Lesley Stahl: I’m trying to understand how a prisoner who’s been cleared to leave twice, with an appeal from a Prime Minister of a friendly country, and he’s still sitting there — I’m just trying to figure out why he’s still there.

Clive Stafford Smith: I think it is a fascinating question and I would love a little more transparency.

Lesley Stahl: What’s the official explanation?

Clive Stafford Smith: I wish someone official would give me an explanation and they won’t. No one will say why they won’t let him go.

Stafford Smith also told her, “What I have said and what Shaker has said for years is that if you have got an allegations against him, put up or shut up,” and, when asked about what would happen if he were to be returned to the UK — if he would be locked up again, monitored, or a free man — Stafford Smith said, “Shaker has agreed to whatever conditions the British government want to put on him, because he has nothing to hide.”

Lies and distortions in CBS’s coverage of Guantánamo

It was powerful to hear Shaker’s voice, and his anguish, although unfortunately the rest of the show was a profound disappointment. The lies and distortions began early on. Lesley Stahl mentioned how there were men held who couldn’t be tried because, as she put it, “The evidence against them is weak or inadmissible, in some cases because it was obtained through quote ‘enhanced interrogation techniques.’”

Not mentioning that “enhanced interrogation” is a euphemism for torture — which would make statements inadmissible, and those who extracted them liable for prosecution — was one problem with this statement, but another was Stahl’s refusal to ask what other factors might contribute to information being “weak or inadmissible.” In the case of Guantánamo, this is because a shocking amount of the information masquerading as evidence consists of unreliable statements made by the prisoners, incriminating themselves or more often incriminating their fellow prisoners, and if these profoundly untrustworthy statements were not produced through the use of torture, they were often produced through other forms of coercion, or through bribing prisoners with better living conditions or in exchange for medical treatment.

Lesley Stahl was taken by Col. Bogdan to Echo Block, where prisoners are held in isolation, and where they responded to her arrival with Col. Bogdan by creating a huge noise, hammering against the doors of their cells. She was told, and repeated the claim, that this was “where detainees who’ve attacked guards are held,” but what was not mentioned was that prisoners held here are also those regarded as being influential — in other words, those like Shaker Aamer, who has been held in Echo Block, who are both articulate and furious about their ongoing imprisonment, and capable of stirring up other prisoners to take action to demand justice.

Discussing Col. Bogdan, Lesley Stahl failed to challenge him significantly on his role as the spur for the prison-wide hunger strike that began in February and raged for seven months. She acknowledged that it had involved him “cracking down,” as she put it, following his appointment last year, and searching cells for contraband, but she never questioned why such a search was deemed necessary in one of the most secure prison environments on earth, or asked him about how abusing prisoners’ Korans triggered the hunger strike. When she asked him what the reasons were for the hunger strike, his only reply was that “their primary complaint was to leave Gitmo,” which is partly truthful, but ignores his role and downplays that what they want, after nearly 12 years, is to be set free or charged and tried; in other words, what they are calling for is justice.

Stahl also mentioned that there had been force-feeding during the hunger strike, but failed to explain how medical professionals condemn it as a profoundly abusive process that should not be undertaken.

She also gave Col. Bogdan far too much time, unchallenged, to defend his own actions. Explaining why he had allowed her access to Echo Block, he said — as she put it — that “everything he’s done he’s done to protect the guards, and he wanted to show us what they’re up against.” Also allowed to pass unchallenged was his claim that PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) at Guantánamo is twice what it is on the battlefield, which, frankly, sounds implausible, and, if true, suggests only that this is what happens when guards are told, as they have been since the prison opened, that the men held there are “the worst of the worst,” when almost all of them are no such thing. It says nothing for the morale of America’s soldiers, if, in such a secure environment (for the soldiers), they are ending up with PTSD.

Towards the end of the program, Stahl delivered the following statement: “Everybody is trapped — the guards, the prisoners, and even President Obama, who says Guantánamo Bay has become so notorious it has quote ‘likely created more terrorists around the world than it ever detained.’” This overlooked President Obama’s own failure to challenge Congress when lawmakers imposed restrictions on the release of prisoners, which have meant that, for the last three years, almost no one has been freed from Guantánamo.

Unfortunately, Stahl followed on from the above by claiming that President Obama “can’t ignore the fact that, of the 606 prisoners already released, 100 have gone on to commit acts of terror.” That is a completely unacceptable claim, taken at face value from profoundly unreliable statements made since 2009 by the DoD and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, even though those claims have never been backed up with evidence. As the New America Foundation has demonstrated, a more realistic figure for those who have engaged — or tried to engage — militarily or through terrorism against the US following their release is 8 percent of the total number of released prisoners; in other words, 48 men in total.

When talking to Clive Stafford Smith, Lesley Stahl told him, “Col. Bogdan says that these are men who are taken off the battlefield so that they will stop committing the acts of terrorism that they are accused of, are believed to have done. This is where they’re taken until the war is over.”

Stafford Smith responded by asking how long the US authorities thought it was plausible for their “war” to continue, when the First World War only lasted four years, and the Second World War only lasted for six. However, Stahl — and Col. Bogdan — managed to evade the massive contradiction inherent in her line of questioning, involving “terrorists” being seized on “battlefields,” when it is soldiers who are seized on battlefields, to be held in accordance with the Geneva Conventions, while terrorists — sometimes on battlefields, but generally not — should be prosecuted in federal courts, as all other terror suspects have been for the last 12 years.

When Stahl was outside Shaker Aamer’s cell, and Shaker was calling out, “Let the world hear what’s happening,” Stahl asked Col. Bogdan, “Do you feel any sympathy for his situation?” Again unchallenged, Bogdan delivered a monstrous piece of “war on terror” rhetoric that should not have been allowed to pass without comment. “To be locked up or detained for 10 years, or 11 years,” he said, “sure, I’m sympathetic to that, but at the same time these men are enemies of us, just as we are enemies to them.”

When 84 of the remaining 164 prisoners have been cleared for release by the president’s own task force, because they are not regarded as posing a threat to the US to warrant their continued detention, that’s a monstrously unacceptable position, but it is typical of this generally ill-informed show that Col. Bodgan wasn’t even challenged.

Note: For a transcript of the “60 Minutes” show, see here.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

November 19, 2013

Award-Winning Soul Singer Esperanza Spalding Calls for Closure of Guantánamo in New Song, “We Are America”

[image error]In the long and ignoble history of the “war on terror” prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, those who have fought to secure its closure have generally labored without the kind of celebrity endorsement that tends to secure mass appeal for political causes. This year, however, celebrities began to take notice when the majority of the 164 prisoners still held embarked on a hunger strike to draw the world’s attention to their ongoing plight, and to remind people that over half of them — 84 men in total — had been cleared for release by an inter-agency task force that President Obama established shortly after taking office In January 2009.

The fact that these men were still held — and that justice appeared to have gone AWOL in the cases of the majority other prisoners still held — encouraged the best-selling novelist John Grisham to write an op-ed about Guantánamo for the New York Times on August (which I wrote about here), focusing on the case of Nabil Hadjarab, an Algerian national, who, Grisham discovered, had been prevented from reading his books. Nabil was freed soon after, although sadly the decision by the British singer-songwriter P.J. Harvey to record a song about Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, did not lead to his release, although nearly 100,000 people have listened to the song.

The latest celebrity to call for the closure of Guantánamo is Esperanza Spalding, a singer, songwriter and bassist who won a Grammy for Best New Artist in 2011. Her song, “We Are America,” with its accompanying video that features cameos by Stevie Wonder, Harry Belafonte and Janelle Monáe, is posted below, and is excellent — a soulful call for justice that ought to be rallying cry for all Americans who believe in the law, and who ought to be appalled that men are being held indefinitely without charge or trial at Guantánamo.

This is the chorus of “We Are America”:

I am America

And my America

It don’t stand for this

We are America

In our America

We take a stand for this

In addition, noticeable amongst the lyrics is Esperanza’s call, “Let them out,” which refers to the 84 prisoners cleared for release but still held, and her call for “justice for the men who should be free.” Also featured in the video are quotes from significant figures — including President Obama and Sen. John McCain, speaking about the need for Guantánamo to be closed.

I do hope you have time to watch the video, and that you will share it as widely as possible.

The video is accompanied by the following message, urging US listeners to tell their Senators to support the version of the National Defense Authorization Act that the Senate is voting on this week, which will help President Obama to close Guantánamo, and which I wrote about in detail here:

Take a stand. Call the US Capitol Switchboard (1-202-224-3121) to connect you to your two US Senators and your Congressional Representative. Tell them:

I am your constituent and I want you to support closing Guantánamo.

Indefinite detention and unfair trials are illegal, un-American and unnecessary.

Here’s the video:

Esperanza Spalding – We Are America from ESP Media on Vimeo.

Below I’m posting an op-ed that Esperanza Spalding wrote for the Los Angeles Times, and also an interview conducted for Amnesty International by Josefina Salomon.

I was also pleased to note that the Wall Street Journal covered the story, in which Esperanza said (by phone from Spain, where she was on tour), “I don’t have any prison experience, but it’s really hard to fathom being imprisoned in a place against your will and not to be charged with anything, not to have the ability to defend yourself, and to be there indefinitely. It’s hard to wrap your mind around it.”

She also said, “My wish is that the information in the video will pique people’s interest enough to go, ‘Hmm, I didn’t know all that,’” and, as the Wall Street Journal put it, “prompt them to learn more.”

I was also interested in the response to the song from the authorities at Guantánamo, as reported in the Miami Herald. Although Defense Department spokesman Lt. Col. Todd Breasseale called it “an evocative performance,” he added, “the artists involved in this particular song and video leave out this crucially important piece of information: Until Congress changes the law regarding the transfer requirements for detainees held at Guantánamo Bay, the department will continue to humanely safeguard those in its charge there.”

Whilst it was predictable that “humane” treatment of the prisoners was stressed — despite medical professionals agreeing that force-feeding is abusive and unacceptable — it was interesting that Lt. Col. Breasseale specifically blamed Congress for the fact that Guantánamo is still open, even though the blame also lies with President Obama, who has largely lacked the political will to challenge lawmakers, or to use a veto in the existing legislation to bypass them completely. However, it was also interesting to see that Lt. Col. Breasseale also followed the White House line about why the prison’s continued existence is unacceptable, when he said, “To be completely clear: We agree with the President. The facility is wildly expensive, it lessens cooperation with our allies, and keeping it open is outside of America’s best interests as it serves as a continued recruiting tool for extremists.”

Below is Esperanza Spalding’s op-ed and the interview:

Music to shine a light on Guantánamo Bay

By Esperanza Spalding, Los Angeles Times, November 18, 2013

I finally read all of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail” this spring while I was on tour for my album “Radio Music Society.” At about the same time, the hunger strike at Guantánamo Bay detention center hit the headlines. Soon, scores of men were being force-fed. The more I learned about what was going on at Guantánamo, the more I realized that the truths King expressed in his famous letter were back in our faces: “Justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

I vowed to do something. When I got home, I called my representative and senators and expressed my support for a just closure of Guantánamo. Then I called my friends and asked them to do the same. But that wasn’t enough: 84 men cleared for release by our national security agencies years ago were still sitting at Guantánamo. I left to go back on tour, but the burning question remained: What else can I do?

At a “Radio Music Society” band dinner, we talked about Guantánamo and realized we shared a deep concern about the issues it raises. Those talks inspired a song, and then a music video — “We Are America” — that we hope will mobilize support for closing the facility. As the project crystallized, I reached out to more friends — some who happen to be quite well known — and they agreed to support our effort by making cameo appearances in the video.

Throughout the process, and after consulting with the American Civil Liberties Union, Amnesty International, Human Rights First and Human Rights Watch, our resolve kept growing. We believe that the blatant injustice of detention without charge at Guantánamo violates not just U.S. human rights obligations but also our basic values and principles.

Of the 779 men who have been held at the facility since it was opened in 2002, only seven have ever been convicted of any charges in military tribunals. Two of those convictions have been overturned on appeal. Another six men are on trial now, and the government says it will only prosecute seven more. That means that of the 164 men being held (many of whom have been there for almost 12 years), about 150 are being held without charges, and they will never be charged.

King’s Birmingham letter emphasizes that concern for justice and equality is not enough to remedy the systematic violation of human rights: “[I am] compelled to carry the gospel of freedom far beyond my own home town…,” he wrote. “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

With the release of “We Are America,” we hope to shine a light for our fellow Americans on these nitty-gritty facts:

The Obama administration has the ability to transfer the 84 detainees who have already been cleared for release out of Guantánamo, and other detainees could soon be cleared by newly established review boards. However, current law needlessly places obstacles in the way of accomplishing that.

Now, the Senate has begun to change that. Provisions in the 2014 National Defense Authorization Act passed out of the Senate Arms Services Committee will break down some of these obstacles and give the president more flexibility to make transfers out of the detention facility. The full Senate will begin debate on the act, and those provisions, in the coming days.

Specifically, Sections 1031 to 1034 of the Senate’s version of the National Defense Authorization Act would permit the transfer of “detainees who have been ordered released by a competent U.S. court” and “would permit transfers for the purpose of detention and trial.” Since 9/11, federal courts have prosecuted hundreds of terrorism cases, and those convicted are currently serving long sentences in high-security federal prisons.

If the Senate and the House of Representatives agree to the Guantánamo provisions in the defense act, the few prisoners in the detention center who face charges could be prosecuted where it makes the most sense, in federal courts.

Radio Music Society (and friends) made “We Are America” because we believe that, while not all of us are called to the front lines like Martin Luther King Jr., we can all support our elected officials in doing the right thing.

Why did Esperanza Spalding record a song about Guantánamo?

By Josefina Salomon, Amnesty International, November 18, 2013

Q: What motivated you to start this whole project to begin with, what was the spark?

Esperanza Spalding: It was the first time I heard about the hunger strike. I was touring in Europe and I was appalled and embarrassed about what was happening. I remember I started researching online to see what I could do about it and I saw that I could download this action pack. With that you had some important info to use to call your representative. And I did, I did call my representative and Senators. In fact, I got a letter back from one Senator who basically said that she was not going to proactively deal with it but that they would ‘keep my comments in mind’, or something like that. But I really wanted to do more. And my band actually came to me first and said they wanted to do something too.

Q: And why do you think this particular issue is important to you — I mean there are a lot of causes you could latch on to — why this one?

Esperanza Spalding: Well, I guess from seeing my mom stick her neck out for other people many times over the years. She is someone who can’t stand injustice anytime. I think her example has affected me, but I’m usually not as brave as her to speak up. At some point in our lives, we’ve all been a silent witness to someone getting screwed over and it can be really confusing and scary to stand up for them. Particularly when they may be part of an unpopular or stigmatized group. I guess in this particular case, I was thinking of the man who has been picked up in his country or a country he was visiting, minding his own business, thrown into this detention center where he is degraded and humiliated; his holy book, his holy text that he sees as sacred, is desecrated, is disrespected; he doesn’t even have access to a fair opportunity to defend his own innocence. I see that and I think: “Oh my god!” He needs a champion.

Q: And what exactly do you mean by champion — what kind of champion are you talking about?

Esperanza Spalding: Well, I know that he has a champion in his lawyer. He has a champion in his family. He has a champion in the human rights community, in these organizations who are working tirelessly for his freedom. But I think he needs a public champion. They need a public champion that helps make it clear that, it’s not about him as an individual, it’s about him as a representative of humanity. That you, him and I have equal rights on this planet. That we’re entitled to those rights just by being a member of our collective humanity and that while I may not identify with or relate to or agree with someone — I could even hate someone — that person is still equally entitled to their own God-given, whoever-given, whatever force-given rights. Intrinsic basic human rights which the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, that my country ratified, protects.

So, in manifesting that belief, somebody’s got to be a public champion for these men. And I always thought that if I ever got well known in music, that I would want to use my “celebrity” to be a champion for people. So with this particular issue, I noticed the lack of a public champion, a well-known figure anyway. For example, when you think environmental degradation, you think of Leonardo DiCaprio or Matt Damon who have been very vocal about it. Or when you think of child malnutrition or poverty, you may think of Angelina Jolie. But when you think about the human rights violations happening at Guantánamo , you think of people in orange jumpsuits tying themselves to the fence in DC — they are the most public figures connected to Guantánamo . And I thought that’s not fair. So I thought if … if my star is bright enough, I can be their champion for this — I want to be that.

Q: And you mentioned your mother just a bit ago — what about her or your background do you think has had an impact on your motivations with this project?

Esperanza Spalding: I remember in elementary school, there was this little bratty, annoying and destructive little boy in my class that the teacher had a hard time with because he was such a pain in the butt! He was acting out and really just behaving terribly. He didn’t do homework, and would never behave. I remember distinctly my mom seeing past all of that and one day noticing he was squinting in the direction of the teacher. My mother asked him if he could see the chalkboard. I don’t know how she had the insight to do that. He didn’t really answer. She just had a feeling, so she convinced the school nurse to give him an eye exam, and it turned out he was nearly blind. This kid was nearly blind. And he was in a home situation where his parents didn’t really care that he was nearly blind, and so she, my mother, became his surrogate advocate at school. She made sure this kid got glasses. Not that it changed his behavior immediately because there were much deeper issues happening. But, what she was championing for was his ability to participate in education.

Q: So she recognized that there might be something else behind what was going on there?

Esperanza Spalding: Right! And she was his champion even though it wasn’t her “duty” — she just proactively did it. That was not out of character for her, but once I could grasp that he was suffering, on some level, I felt embarrassed because I had always joined in with the general dislike of this kid. Then, there goes my mom patiently talking to him, the only one who thought of taking this kid to get his eyes checked. That really had an impact on me — on my mind. And now I think, “Wow, go Mom … that was great!” you know? So, something in that experience is related to my concern for this issue. We have to see past all of the stereotypes, all the negativity, the stigma, the culture of resistance and fear, and go straight to the basic intrinsic rights of all people and fight for that. So that it’s not for any individual person, it’s about the basic human rights of all people.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

November 18, 2013

Will A Rehabilitation Center Lead to the Release of the Cleared Yemeni Prisoners in Guantánamo?

Two weeks ago, the Los Angeles Times ran an article about one of the enduring problems at Guantánamo — how to establish a situation in Yemen to reassure those who are concerned about the security situation in the country that it is safe to release the 56 Yemeni citizens still held at Guantánamo who were cleared for release nearly four years ago, in January 2010, by the inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shorty after taking office in 2009.

Two weeks ago, the Los Angeles Times ran an article about one of the enduring problems at Guantánamo — how to establish a situation in Yemen to reassure those who are concerned about the security situation in the country that it is safe to release the 56 Yemeni citizens still held at Guantánamo who were cleared for release nearly four years ago, in January 2010, by the inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shorty after taking office in 2009.

It is ridiculous, of course, that men cleared for release are still held, but that is the reality on the ground in the United States today, as it has been since the end of 2010, when lawmakers began passing legislation designed to prevent the president from releasing prisoners or closing the prison, as he had promised.

In fact, 84 of the remaining 164 prisoners in Guantánamo were cleared for release by President Obama’s task force, but while some of the other men need third countries to be found that are prepared to take them in because it is unsafe for them to be repatriated, and others — like Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison — only need President Obama to flex his political muscles to send them back home, the Yemenis are a slightly more complicated matter.

This is not for reasons that have anything to do with notions of justice. Those were first jettisoned by the Bush administration when a “war on terror” was declared following the 9/11 attacks, and Guantánamo was subsequently established, and they were jettisoned again, when, having promised to close Guantánamo within a year, and having established a sober and responsible inter-agency task force to review all the men’s cases, President Obama responded to the task force’s recommendations that 156 of the 240 prisoners held when he took office should be released by releasing some and then allowing the whole process to grind to a halt when he met political opposition.

For the last three years, only seven prisoners have been released from Guantánamo, but whenever the plight of the cleared prisoners has come up, it is clear that the Yemenis have been consigned to the bottom of the pile. The task force, conscious of long-standing fears about the security situation in Yemen, which had led to only 16 Yemeni prisoners being released by President Bush, had consigned 30 of the cleared prisoners to a separate category that they made up, which was called “conditional detention.” The detention of these men was justified as lasting until there was a perceived improvement in the security situation in Yemen, but the task force failed to provide any indication of who would decide this, or how it would be decided.

Then, on Christmas Day 2009, a Nigerian man recruited in Yemen, Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, tried and failed to blow up a plane bound for Detroit with a bomb in his underwear, and, in response, there was a hysterical backlash against all Yemenis, to such an extent that President Obama was prevailed upon to impose a moratorium on releasing any cleared Yemeni prisoners from Guantánamo, thereby consigning the other Yemeni prisoners — 28 at the time — to the same open-ended “conditional detention” as the 30 others.

Since that time, just one Yemeni prisoner has been released, and one other cleared prisoner died, and it was not until May this year that, provoked by a prison-wide hunger strike which had awakened the world’s media to the ongoing plight of the Guantánamo prisoners, President Obama dropped his ban on releasing Yemeni prisoners, which he announced in a major speech on national security issues.

Despite this, no Yemenis have been released since the speech, but the indefinite imprisonment of Yemenis on the basis of their nationality alone — which I regularly refer to as “guilt by nationality” — may be coming to an end, as the Los Angeles Times reported two weeks ago.

Plans for a rehabilitation center

According to the article, both US and Yemeni officials said that the Obama administration was talking to Yemeni officials about setting up a facility outside the capital Sana’a to hold dozens of prisoners — not just from Guantánamo, but also from Afghanistan, where a handful of Yemeni prisoners have been held for up to 11 years.

A US official described as being “familiar with the talks,” but “who spoke on condition of anonymity because the plans are classified,” told the Los Angeles Times, “There’s a definite recognition that this needs to happen but if it’s not done right, the risks are very high.”

It was noted that, although Yemeni officials “have drawn up preliminary plans for the facility,” outside Sana’a, “final agreement may be months away.” As the article explained, “Deep disagreements remain on funding, and about whether it would function as another prison or as a halfway house for detainees to re-enter society after years of confinement and isolation.”

That latter point is crucial, because there is absolutely no justification for imprisoning those who are released from Guantánamo, and who have already been cleared for release by President Obama’s task force, and there is no justification either for holding men returned from Afghanistan, who have not even had the luxury of a presidentially appointed task force making decisions about their disposition.

Those returned should only be held during a period of rehabilitation, designed to facilitate their re-entry into Yemeni society, because, if they posed any kind of significant threat, there would not be discussions taking place about their release. In Guantánamo, for example, there are five more Yemenis who were recommended by the task force for prosecution and 26 others who were recommended for ongoing imprisonment on the basis that they are too dangerous to release but insufficient evidence exists to put them on trial. This is a disgraceful attempt to justify detention, which I don’t endorse, of course, but a mechanism for addressing the men’s cases — known as the Periodic Review Boards — has recently been established, so there is some hope that they have not been abandoned completely.

I intend to write about the PRBs in the near future, but for now the importance of these cases for the prisoners cleared for release but still held is to distinguish between them, and to point out that, from the US government’s point of view, those eligible for release are not regarded as posing a threat, and should not be imprisoned on their return, just to satisfy the hysteria of a handful of people with power and authority in the United States.

These concerns were noted in the Los Angeles Times article, which explained, “Human rights activists warn that they will oppose the new facility if it means Yemenis who were imprisoned for years without being charged at Guantánamo Bay are merely shifted to serve indefinite detention at a new jail.” Andrea Prasow, senior counter-terrorism counsel with Human Rights Watch, said, “I don’t think [it] should exist unless it’s an actual rehabilitation program. There’s no way I would find it acceptable for [returned Yemeni detainees] to be held against their will.”

For their part, US officials portrayed the proposed facility as somewhere where returned prisoners “would undergo counseling, instruction in a peaceful form of Islam, and job training in Yemen before any decision on freeing them” was made. It was also noted that the program “would be modeled on a largely successful Saudi effort to reintegrate Islamic militants into society,” and White House officials stated that they were “working with the United Nations and other governments to assist Yemen with the project.” However, doubts remain about the intentions of the US, despite Caitlin Hayden, a spokeswoman for the National Security Council, stating, “We believe that the establishment of a credible, sustainable program would be an important step for the Yemeni government in bolstering their counter-terrorism capabilities.”

The key doubt concerns the relationship between the aspects of the program involving rehabilitation, and those involving “any decision on freeing them,” as the Los Angeles Times described it, as it could easily become a situation which replicates the fearfulness that has already kept the men at Guantánamo years after they were cleared for release.

As negotiations continue, the Los Angeles Times noted that US officials expressed concerns that repatriated Yemeni prisoners “may resume terrorist activities after being released, possibly by joining Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula,” while Yemeni officials “don’t want to be seen helping Washington create an alternative to the unpopular prison at Guantánamo Bay.” As the article described it, “They warn that any US-backed facility would create a target for attacks by Islamist militants, and thus would need heavy defences.” The article proceeded to explain that, in recent talks held in Rome “because of security risks in Yemen,” Yemeni officials “pressed US and European officials for funding for construction and training guards and other staff members,” and “brought Saudi Arabia into the talks as well in the hope it will pay for the project.”

The Los Angeles Times also noted that Yemen’s foreign minister, Abubakr Qirbi, “acknowledged last month that his government plans to construct a facility for ‘rehabilitation’ of Guantánamo Bay detainees,” but noted that he “did not mention the US involvement.” Alarmingly, the article also noted that he “portrayed the returning prisoners as non-violent.” Quite why this was regarded as an acceptable comment for the Los Angeles Times to make was not made clear, but, to return to the task force’s deliberations, if the 56 cleared for release were regarded as dangerous, they would not have been cleared for release.

In fact, there was nothing to take exception to in Abubakr Qirbi’s words. Yemen’s official news agency reported that he said, “We are currently planning to construct this facility and taking legal steps for the return of the 55 [or 56] people who the US has agreed to send home, those who do not pose a threat.” He added, “A meeting of specialists from Yemen, Saudi Arabia and the European Union was held to mull over the construction of the rehabilitation facility.”

The fact that Abubakr Qirbi did not mention the US was probably because of ambivalence in Yemen towards the supposed ally who conducts drone strikes on Yemeni soil, and keeps holding Yemeni citizens it says it no longer wants to hold.

I sincerely hope that the proposals regarding a rehabilitation center in Yemen lead to positive action, as the ongoing imprisonment of the cleared Yemeni prisoners is the single biggest reminder of the gross injustice of holding a high-level review process to decide who to release, and then not releasing them.

That, as I have said before, adds an edge of cruelty to the indefinite detention taking place at Guantánamo that even openly totalitarian regimes would hesitate to implement. It is time for these 56 men to be freed.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

November 17, 2013

Radio: Andy Worthington Discusses Guantánamo’s 12th Anniversary and Accountability for Torture with Scott Horton and Peter B. Collins

On Wednesday (November 13), the media, inspired by an article for the Guardian by Col. Morris Davis, the former chief prosecutor of the military commissions at Guantánamo, who has become a formidable critic of the prison since his resignation six years ago, picked up on a baleful anniversary — the 12th anniversary of the creation of one of the main founding documents of the Bush administration’s “war on terror.”

On Wednesday (November 13), the media, inspired by an article for the Guardian by Col. Morris Davis, the former chief prosecutor of the military commissions at Guantánamo, who has become a formidable critic of the prison since his resignation six years ago, picked up on a baleful anniversary — the 12th anniversary of the creation of one of the main founding documents of the Bush administration’s “war on terror.”

I subsequently spoke to Scott Horton on his hard-hitting political show, the latest in the dozens of interviews with Scott that I have taken part in over the last six years. The half-hour show is available here as an MP3, and I hope you have time to listen to it.

Scott described the show as follows: “Andy Worthington, author of The Guantánamo Files, discusses how Dick Cheney helped make torture an official US government policy; former Guantanamo inmate Omar Khadr’s fight for justice in a Canadian prison; and how torture has poisoned America’s soul.”

As Scott explained, we did indeed talk about how Omar Khadr, and his appeal against his outrageous 2010 conviction for war crimes (which I wrote about here), as well as also discussing the need for accountability for all of the senior Bush administration officials (up to and including George W. Bush, Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld) and their lawyers, who approved the use of torture.

I do, however, consider the spur to our discussion — the document issued on November 13, 2001 — as something worthy of reflecting on further.

The “Military Order of November 13, 2001,” or, to give it its official title, “Detention, Treatment, and Trial of Certain Non-Citizens in the War Against Terrorism,” authorized “terrorists and those who support them” to be “detained, and, when tried, to be tried for violations of the laws of war and other applicable laws by military tribunals.”

This document, which established the rationale for the opening of Guantánamo and the creation of military commissions, was a major contribution to the “war on terror” by George W. Bush’s Vice President, Dick Cheney, “the malevolent power behind the American imperial throne,” as I explained in June 2007 while the Washington Post was publishing a major series on Cheney by Barton Gellman (the author of Angler, a subsequent book about Cheney) and Jo Becker.

Via the Post, I discovered how:

[O]n 13 November 2001, under the cover of his regular weekly meeting with the President, [Cheney] played the leading role in circulating and gaining approval for the presidential order — Military Order No 1 — which stripped foreign terror suspects of access to any courts, authorized their indefinite imprisonment without charge, and also authorized the creation of “Military Commissions,” before which they could be tried using secret evidence. Approved within an hour by only two other figures in the White House — associate counsel Bradford Berenson, and deputy staff secretary Stuart Bowen, whose objections that it had to be seen by other Presidential advisors were only dropped after “rapid, urgent persuasion” that the President “was standing by to sign and that the order was too sensitive to delay” — the order’s swift and unprecedented passage bore all the hallmarks of Cheney’s preferred modus operandi: that of an ultra-secretive control freak who, while serving the President, was actually running the show himself.

While I hope you have time to listen to Scott’s show, I’d also like to recommend another interview I did recently, with someone else I have been speaking to for many years, Peter B. Collins, who interviewed me for the “Processing Distortion” show he does for FBI whistleblower Sibel Edmonds’ Boiling Frogs website.

Our interview, which lasted for over an hour, and was very wide-ranging and in-depth, is available here, although it you can only listen to it if you subscribe to Sibel’s site, something that I recommend, as both Sibel and Peter do important work, as I do, without any institutional backing.

This is how Peter described the show:

Since Obama’s May [23] speech, very little has changed at Guantánamo. British journalist Andy Worthington notes that while two Algerians were released in August, and in early October the Pentagon named its Special Envoy for Guantánamo (and Parwan in Afghanistan), very little else has changed since Obama lamented the hunger strike and blamed Congress. Worthington points out that the president can use an existing waiver process on some or all of the 84 men who have been cleared for release since 2009 — some far longer. We also discuss about 46 men Collins calls “zombies”, who will not be charged or tried but held indefinitely, and the obvious improprieties that have marked the early stages of the trials of Khalid Sheikh Muhammed and 4 co-defendants.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

November 15, 2013

New Report Condemns Role of Doctors, Psychologists and Psychiatrists as Torturers in Bush’s “War on Terror”

[image error]Unusually, there has been so much Guantánamo-related news lately that I haven’t had time to write about it all. A case in point is “Ethics Abandoned: Medical Professionalism and Detainee Abuse in the War on Terror” (also available here on Scribd), a 156-page report by the Task Force on Preserving Medical Professionalism in National Security Detention Centers, an independent panel of 19 military, ethics, medical, public health, and legal experts, who spent two years working on their report, with the support of the Institute on Medicine as a Profession and the Open Society Foundations.

The report was published on November 5, and, as a press release explained, the task force of experts “charged that US military and intelligence agencies directed doctors and psychologists working in US military detention centers to violate standard ethical principles and medical standards to avoid infliction of harm.”

The task force also concluded that, “since September 11, 2001, the Department of Defense (DoD) and CIA improperly demanded that US military and intelligence agency health professionals collaborate in intelligence gathering and security practices in a way that inflicted severe harm on detainees in US custody,” which included “designing, participating in, and enabling torture and cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment” of prisoners seized in the “war on terror.”

Particular criticism was directed at the CIA’s Office of Medical Services, who, as the task force explained, “played a critical role in reviewing and approving forms of torture, including waterboarding, as well as in advising the Department of Justice that ‘enhanced interrogation’ methods, such as extended sleep deprivation and waterboarding that are recognized as forms of torture, were medically acceptable.” The task force added, importantly, that CIA medical personnel “were present during [the] administration of waterboarding,” which is true, but the even more alarming fact is that all the torture and abuse that was so widespread in the “war on terror” needed medical personnel to be present to make sure — or to try and make sure — that no one died.

Dr. Gerald Thomson, Professor of Medicine Emeritus at Columbia University, and a member of the task force, stated, “The American public has a right to know that the covenant with its physicians to follow professional ethical expectations is firm regardless of where they serve. It’s clear that in the name of national security the military trumped that covenant, and physicians were transformed into agents of the military and performed acts that were contrary to medical ethics and practice. We have a responsibility to make sure this never happens again.”

The task force called on the DoD and CIA “to follow medical professional standards of conduct to enable doctors and psychologists to adhere to their ethical principles so that in the future they be used to heal, not injure, detainees they encounter,” and urged professional medical associations and the American Psychological Association “to strengthen ethical standards related to interrogation and detention of detainees.” The task force noted that, although the DoD had “taken steps to address some of these practices in recent years, including instituting a committee to review medical ethics concerns at Guantanamo,” the changes to the role of health professionals since 9/11, and what were described as “anaemic ethical standards adopted within the military” are still in place.

The report also listed the policies put in place in the “war on terror” that breached the required ethical standards “to promote well-being and avoid harm,” and listed them as:

Involvement in abusive interrogation; consulting on conditions of confinement to increase the disorientation and anxiety of detainees;

Using medical information for interrogation purposes; and

Force-feeding of hunger strikers.

That last point is one that has been of particular relevance this year, with the well-publicized hunger strike, which, for seven months, involved the majority of the prisoners. Despite court submissions by lawyers on behalf of the prisoners, in which they urged judges to order the government to stop the force-feeding, the judges were obliged to rule that they didn’t have jurisdiction because of previous rulings involving Guantánamo and hunger strikes. Specifically, when Congress passed the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005, the legislation prevented prisoners from suing over their living conditions.

An appeal was submitted last month, which I wrote about here, in which two of the three judges in the Washington D.C. appeals court, Judge David Tatel and Judge Thomas Griffith, “asked sceptical questions.” Reuters reported that, while they “stopped short of agreeing that forced feeding is inhumane, they suggested that Guantánamo detainees might be able to get around” the conditions in the DTA, which “bars them from suing over living conditions in extreme cases that might include forced feeding.”

The publication of the report also coincided with a screening, in London, of “Doctors of the Dark Side,” a documentary film, directed by Martha Davis, a clinical psychologist, who visited London for the screening at UCL, where I had the pleasure of meeting her. As described on the film’s website, “Doctors of the Dark Side” tells the stories of four prisoners and the doctors involved in their abuse, and exposes “how psychologists and physicians implemented and covered up the torture of detainees in US controlled military prisons.”

The website also features a powerful comment by Nathaniel Raymond, formerly the director of Physicians for Human Rights‘ anti-torture campaign, who called the participation of doctors, psychologists and psychiatrists in the Bush administration’s post-9/11 program of torture, rendition and indefinite detention “the single greatest scandal in the history of American medical ethics.”

One thing that struck me most powerfully while I was watching “Doctors of the Dark Side,” and that also emerged in discussions afterwards was, as I mention above in relation to waterboarding, that it is no exaggeration to say that, without doctors to oversee and check on the victims of torture, the entire program would have been inconceivable, laying the responsibility for the widespread torture and abuse on doctors, psychologists and psychiatrists as much as on the senior officials in the Bush administration and their lawyers, who conceived and authorized the programs of torture and abuse, and the senior military figures, and those in the CIA, who implemented them.

I hope that the publication of “Ethics Abandoned: Medical Professionalism and Detainee Abuse in the War on Terror” leads to further action, to try and ensure that the kind of abuse that is still ongoing at Guantánamo, with relation to the 11 prisoners still being force-fed, is brought to an end, and steps taken to make sure that it cannot happen again.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

November 14, 2013

Petition: Tell Boris Johnson Not to Approve the Monstrously Inappropriate Development Plans for Convoys Wharf in Deptford

Please sign the petition on Change.org, asking London’s Mayor, Boris Johnson, not to approve a £1bn plan to turn Henry VIII’s former Royal Dockyard at Convoys Wharf in Deptford into a luxury, high-rise housing development that would be more at home in Dubai.

Please sign the petition on Change.org, asking London’s Mayor, Boris Johnson, not to approve a £1bn plan to turn Henry VIII’s former Royal Dockyard at Convoys Wharf in Deptford into a luxury, high-rise housing development that would be more at home in Dubai.

All over London, housing developments that are unaffordable for the majority of Londoners continue to rise up, and equally unaffordable new projects continue to be approved. Councils are either cash-strapped and desperate, or they are seduced by developers’ promises that their developments will be of benefit to the community at large, even though the entry level for luxury developments is a household income of £72,000, way above the £53,000 that even a couple on the average UK income (£26,500) can afford. When you consider that the median income in the UK is £14,000 (the one that 50 percent of people earn more than, and 50 percent earn less than), it’s easy to see how the entire situation is out of control and is doing nothing for local people, or the majority of hard-working Londoners.

Down the road from where I live in south east London is Deptford, a vibrant but not affluent part of the London Borough of Lewisham, with a huge maritime history. Where Deptford meets the River Thames is the largest potential development site in the borough, Convoys Wharf, a 16.6 hectare (40-acre) site, which most recently was News International’s paper importing plant for printing Rupert Murdoch’s newspapers. Murdoch’s operation closed in 2000, and, since 2002, developers have been trying to gain approval for a massive luxury housing development on the site, featuring 3,500 homes — 3,000 of which will be sold “off-plan” to foreign investors — and including three towers rising to 40 storeys in height. Moreover, just 15 percent of the homes will be what is laughingly described these days as “affordable” (at 80 percent of market rents, these rents are actually unaffordable for most people), and just 4 percent will be for social rent (i.e. genuinely affordable) — that’s just 140 properties out of the total of 3,500.

The development would not only ruin the skyline in the whole of south east London and introduce a dangerous juxtaposition of immense wealth and poverty into Deptford, but would also largely destroy the hugely important heritage of the site, because Convoys Wharf, far from being just a recently abandoned industrial location, is in fact the site of King Henry VIII’s Royal Dockyard, founded exactly 500 years ago, in 1513.

For eleven years, with plans first by Richard Rodgers (who has an interesting architectural history), then by Aedas (whose scheme was criticised as being “monstrous”), and most recently by Terry Farrell (who doesn’t have an interesting architectural history), complaints about the unsuitable scale of the developers’ proposals, the relative absence of genuinely affordable housing, and their neglect of the site’s historical importance (which also includes the nearby site of Sayes Court, the former home of the diarist and botanist John Evelyn), have prevented it from going ahead, with English Heritage adding the considerable weight of their opposition to the plans to the complaints and proposals of local campaigners, and, most recently, the World Monuments Fund also adding Convoys What and Sayes Court to their internationally important watch list.

English Heritage’s criticism

In July, as Building Design explained, English Heritage “criticised Farrells’ £1 billion Convoys Wharf masterplan for failing to put the site’s history at the centre of the scheme.” The site added, “Responding to the planning application, English Heritage acknowledged that the new scheme was a significant improvement and praised the developer for carrying out the largest archaeological investigation of an historic dockyard in the world.”

In July, as Building Design explained, English Heritage “criticised Farrells’ £1 billion Convoys Wharf masterplan for failing to put the site’s history at the centre of the scheme.” The site added, “Responding to the planning application, English Heritage acknowledged that the new scheme was a significant improvement and praised the developer for carrying out the largest archaeological investigation of an historic dockyard in the world.”

Mark Stevenson, English Heritage’s archaeology advisor, said, “The scale of work undertaken is a reflection of the importance of the site, the anticipated quality and quantity of archaeology and that the applicant recognised that a detailed understanding was essential in developing a planning application to redevelop this nationally important site.”

However, as Building Design described it, “the eight ‘overarching design principles’ listed in the planning application do not include a consideration of the history of the site as an objective.” Stevenson explained that this “would appear to be at odds with the expectation of heritage being a core element of the design approach alluded to in the heritage statement,” adding a complain that “recent archaeological discoveries were not incorporated.”

He “urged Lewisham council to ‘seek further opportunities’ to reflect the historic character in the design,” but those opportunities, of course, have now been taken away by Hutchison Whampoa in its appeal directly to the Mayor.

The World Monuments Fund includes Convoys Wharf on its watch list

Most recently, Building Design reported on the inclusion of Convoys Wharf and Sayes Court on the World Monuments Fund’s watch list, stating that “Henry VIII’s naval dockyard at Deptford has been added to the list for the first time because of fears that a planned £1 billion housing development will damage the 500-year-old site.”

Describing Convoys Wharf as a “much-contested site, which retains some of its Tudor and Victorian structures,” and noting that historians “complain that none of the schemes does justice to the significance of the area,” Building Design spoke to Jonathan Foyle, the chief executive of World Monuments Fund Britain, who said, “Deptford’s most imminent threat comes from the failure of existing proposals to fully acknowledge and respect the heritage assets that the site has to offer.”

He added, “Incorporating the extensive archaeology and combining this with unique public spaces has the potential to strengthen Deptford’s local identity while securing this lost piece of the Thames jigsaw. It would also improve awareness of the little-known existence and overlooked history of the dockyard and gardens on a national stage.”

Building Design noted that Convoys Wharf and John Evelyn’s gardens join “67 sites from 41 countries on the 2014 list, including three others from the UK”: Battersea Power Station, which “remains on the list 10 years after it was first added despite the imminent start of restoration work to be overseen by Wilkinson Eyre,” the 16th-century Sulgrave Manor in Northamptonshire, built by the ancestors of George Washington, and Grimsby’s Victorian ice factory — “the earliest and largest-known surviving ice factory in the world, and the only one to retain its machinery” — and surrounding “Kasbah” docks.

The petition

Lewisham Council have been careful not to approve a plan that is fraught with serious problems, regardless of how much money the Hong Kong-based developers, Hutchison Whampoa, have been thrusting at them, but now the developers have tired of what they perceive as obstruction, and have appealed directly to Boris Johnson, London’s Mayor, and there are very real fears that Johnson will do the wrong thing and approve the plans as they currently stand.

In response, the petition states the following:

We, the undersigned, are gravely alarmed at the proposed scale and impact of the current plans by Hong Kong developer Hutchison Whampoa, that will irrevocably destroy the site of Britain’s historic Royal Dockyard and Sayes Court Garden at Deptford by the River Thames in London.

We welcome the recognition of this fact by the inclusion of Deptford Dockyard (now known as Convoys Wharf) and Sayes Court Garden on the World Monuments Fund Watch List for 2014 and the serious concern expressed by English Heritage and many other heritage bodies, Lewisham Council and local community groups represented by Deptford Is. We note that this year is the 500th anniversary of the founding of the Royal Docks by Henry VIII in 1513.

We also applaud the extensive work carried out by the Sayes Court Garden and Build The Lenox projects to create two visionary regeneration schemes. These will reinterpret and celebrate the heritage of the area while at the same time creating major new tourist attractions, safeguarding Deptford’s maritime and horticultural links, and creating skilled jobs for local people around the birthplace of the National Trust and Deptford Royal Dockyard.

We regret the lack of meaningful engagement with the community by Hutchison Whampoa so far; note that, at the developer’s request, the Mayor of London has used his powers to take over as the planning authority and further note that Sir Terry Farrell, who is the Mayor’s Design Adviser, is also the architect employed by Hutchison Whampoa.

We reject any claims that this scheme will address London’s housing needs. With a maximum of 15% affordable housing, just 4% of this for social rent, we believe it will make no significant difference to the capital’s housing crisis.

We therefore call on the Mayor of London as the planning authority, Sir Li Ka Shing, chairman of Hutchison Whampoa as the ultimate applicant and the Secretary of State to revise the proposals with greater sensitivity for their location. We ask them to respect 500 years of British maritime history and 360 years of horticultural history on this internationally significant site; one which is inextricably associated with Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, Sir Francis Drake, Sir Walter Raleigh, Samuel Pepys, John Evelyn, Octavia Hill, Christopher Marlowe, Tsar Peter the Great, and Captain James Cook.

Hutchison Whampoa “threw its toys out of the pram”

The most detailed analysis of the latest developments can be found on the “Deptford Is” website, where campaigners agains the current plan explain the circumstances whereby, despite the very real need for ongoing discussions about “important issues relating to transport, design and heritage, Sayes Court Garden and the Lenox Project, and sustainability,” Hutchison Whampoa “threw its toys out of the pram, as if its masterplan was incontrovertable and not subject to planning processes whereby different stakeholders could give their views on it.”

Edmond Ho, Hutchison Whampoa’s director of European operations, told Lewisham’s planners, “we believe the approach you are taking, in not only requesting further changes to the masterplan but even introducing new constraints and unrealistic demands … is both unreasonable and unwarranted, given the already tough viability constraints.”

As “Deptford Is” described it, “Shortly afterwards, Hutchison Whampoa wrote to the Mayor of London requesting he ‘call in’ the application. Bypassing local processes, and citing ‘delays’ and erosion of profits as a basis for his actions, Ho made a pre-emptive request for a premature decision. The Mayor duly called in the planning application on the grounds that the relationship between the developer and Lewisham had irrevocably broken down.”

“Deptford Is” described the move as “almost unprecedented,” and noted that, although Boris Johnson has said he will make a decision by February, “the decision-making process the GLA [Greater London Authority] must now go through is likely to take longer than Lewisham have been taking,” and, moreover, “By involving the Mayor of London, the process will now take place on a much larger stage. The developer’s refusal to engage with stakeholders and accommodate the worldwide importance of the site’s heritage will become ever more visible (it is this non-negotiable stance which has held back the development, not the planners). Meanwhile, by approaching London’s Mayor directly, Ho has terminated the democratic planning process and made a mockery of the Localism Act.”

“Deptford Is” added, “He is also perhaps hoping to bypass the final Archaeology report that is yet to be submitted. The report is expected to acknowledge that some 75% of the infrastructure representing 500 years of dynamic development of the Royal Dockyard at Deptford is essentially intact and ready to reinstate for maritime purposes. Or perhaps the final straw for the developer was the World Monuments Fund putting the site on its Watch List?”

“Deptford Is” also noted how Hutchison Whampoa has claimed, in a letter to Lewisham Council (which will also have been seen by the Mayor and the GLA) that “the GLA and Lewisham’s Design Panel have endorsed the masterplan and overall development,” even though Lewisham’s CEO, Barry Quirk, told Building Design that the developer “had submitted its plans at too early a stage, cutting short pre-application discussions, and had recently cancelled meetings at which outstanding issues could have been resolved.”

Edmund Ho also claimed that Hutchison Whampoa had “fully considered points raised by English Heritage,” although “Deptford Is” noted that what that meant was that, with “a familiar arrogance,” the developers’ response to English Heritage’s comments was merely “to explain how the masterplan decisions were reached”. “Deptford Is” added, “those decisions were made before [English Heritage]’s report was submitted, and [Hutchison Whampoa] has subsequently refused to alter its plans in order to acknowledge [English Heritage]’s unambiguous request to reduce the density of the development.”

Ho’s letter also claimed that Terry Farrell “took the time to meet with English Heritage to satisfy the concerns being raised,” adding that “we understand English Heritage have largely accepted the overall approach being taken,” even though English Heritage “have denied such a meeting took place.”

As also needs pointing out, and as was mentioned briefly in the petition, Terry Farrell “is part of the Mayor’s Design Advisory Group, which plays ‘a significant role in shaping future developments which fall under the Mayor’s responsibility through his regeneration, planning, housing and land powers.’” As “Deptford Is” noted, “Sir Terry advises the Mayor on ‘how to secure the best results on new developments through procurement.’ Could this not be viewed as a conflict of interests?” to which the answer, of course, must be a resounding yes.

“Deptford Is” also criticised Edmund Ho for claiming that further changes to the masterplan would push “the viability of the project to its limits,” pointing out that Hutchison Whampoa’s boss, Li Ka Shing, is “the eighth richest billionaire in the world.” They also worry about Boris Johnson’s cosiness with Chinese investors, following his recent trade visits to China and they also note that Johnson is “very pally with Rupert Murdoch, as is Li Ka Shing,” adding that, although News International sold the site to Hutchison Whampoa, Murdoch’s company retains “a profit share in the sale of the residential units.”

What will happen now?

It is to be hoped that English Heritage will again weigh in heavily on behalf of the heritage of the site, especially with the World Monuments Fund having taken up the cause of Convoys Wharf, and also because of Hutchison Whampoa’s blatant disregard for critics of its plans (including English Heritage) and the parameters of the existing planning processes. It is also to be hoped that local campaigners can make sure that the Mayor understands that they — we — are no push-over.

In addition, Deptford’s MP, Joan Ruddock, has written to Boris Johnson to request a meeting, calling the site “an archaeological and heritage jewel in London’s crown.” She said, “I will be trying to persuade the Mayor to recognise the immense heritage value of this site both to local people and the people of London. The development needs to reflect Deptford’s extraordinary past while meeting local needs and fitting into the local environment.”

[image error]Boris Johnson already faces one additional problem, as “Deptford Is” described it, because, in June this year, he “pledged his support for the Lenox project in answer to a written question from London Assembly member Darren Johnson.” Not only did he agree to the project, but he also “agreed that the ship be built at the Double Dry Dock” on the site, a decision that the developers evidently disliked, as their representatives refused to agree to a discussion about it. Johnson will need to be reminded of this fact, as well as being reminded that some heritage issues are too important to be swept aside for an envelope full of cash.

“Deptford Is” concluded their recent article by stating that Boris Johnson has two options. They claim that he “can use his power and influence to assist the owners to appreciate that they own a very valuable piece of England’s story” and adapt their plans appropriately, or, as they put it, he “can choose to demand that the owners, together with architects and specialists, including English Heritage, the World Monuments Fund and the London Borough of Lewisham, start with a clean slate and remove all the assumptions about this being just any old brownfield site.”

I believe that only the latter option is appropriate, but actually I’d like to see Hutchison Whampoa abandon their plans completely, so that big money and its greed can be booted out of Convoys Wharf completely, and we can have a new scheme led by those concerned with the site’s heritage, and with local people’s need for jobs and genuinely affordable housing. This, moreover, will need to be low-rise to respect the scale of buildings on the Thames shoreline in south east London.

At present, of course, it’s nothing more than a fantasy, as developers and speculators are still succeeding in turning every scrap of spare land in London into massive returns — for themselves, and themselves alone. This does nothing for London as a whole, and before the bubble bursts, when foreign investors are exhausted, or it becomes apparent that prices cannot rise vertiginously forever, or someone notices that speculative purchases continue to sit empty in vast numbers as hard-working Londoners struggle to get by, or are even forced to leave London entirely, I hope that somewhere a stand will be made — and I want, very much, for that stand to be taken in Deptford, at Convoys Wharf.

Note: See my article from last October, “Beautiful Dereliction: Photos of the Thames Shoreline by Convoys Wharf, Deptford,” for more about what Convoys Wharf, the shoreline and its desolation mean to me.