M. Allen Cunningham's Blog, page 24

October 13, 2010

Prime Passages: Cyril Connolly & C.S. Lewis Discuss Some Threats to Literary Appreciation

Connolly was writing seven decades ago, Lewis five, but amid a publishing culture geared almost exclusively toward so-called "upmarket fiction" their views are remarkably relevant.

"Writing is a more impure art than music or painting. It is an art, but it is also the medium in which many millions of inartistic people express themselves, describe their work, sell their goods, justify their conduct, propagate their ideas. It is the vehicle of all business and propaganda. Since it is hard to paint or compose without a certain affection for painting or music, the commercial element—advertisers, illustrators, are recognizable, and in a minority, nor do music and painting appeal to the scientific temperament.

But writing does. It is an art in which the few who practice it for its own sake are being always resented and jostled through its many galleries by the majority who do not. And the deadliest of these are the scientific investigators, clever young men who have themselves failed as artists and who bring only a passionate sterility and a dark, wide-focusing resentment to their examination of creative art. The aim of much of this destructive criticism, though not yet as publicly avowed, is entirely to eliminate the individual style, to banish imaginative beauty and formal art from writing. Prose will not only be as unassuming as good clothes, but as uniform as bad ones." (p.76)Cyril Connolly, Enemies of Promise (1938)

…What is more surprising and disquieting is the fact that those who might be expected ex officio to have a profound and permanent appreciation of literature may in reality have nothing of the sort. They are mere professionals. Perhaps they once had the full response, but the 'hammer, hammer, hammer on the hard, high road' has long since dinned it out of them. … For such people reading often becomes mere work. The text before them comes to exist not in its own right but simply as raw material; clay out of which they can complete their tale of bricks. Accordingly we often find that in their leisure hours they read, if at all, as the many read. I well remember the snub I once got from a man to whom, as we came away from an examiners' meeting, I tactlessly mentioned a great poet on whom several candidates had written answers. His attitude (I've forgotten the words) might be expressed in the form, 'Good God, man, do you want to go on after hours?'…For those who are reduced to this condition by economic necessity and overwork I have nothing but sympathy. Unfortunately, ambition and combativeness can also produce it. And, however it is produced, it destroys appreciation." (p.6-7)C.S. Lewis, An Experiment in Criticism (1961) and Connolly again (same book as above):

"One further question is raised by Maugham. 'I have never had much patience,' he states, 'with the writers who claim from the reader an effort to understand their meaning.' This an abject surrender, for it is part of the tragedy of modern literature that the author, anxious to avoid mystifying the reader, is afraid to demand of him any exertions. 'Don't be afraid of me,' he exclaims, 'I write exactly as I talk—no, better still—exactly as you talk.' Imagine Cezanne painting or Beethoven composing 'exactly as he talked'! The only way to write is to consider the reader to be the author's equal; to treat him otherwise is to set a value on illiteracy, and so all that results from Maugham's condescension to a reader from whom he expects no effort is a latent hostility." (p.79-80)

October 11, 2010

The Artist's Work

... In America it has always been the spiritual task of the artist to defend his art to a private self [image error]who wished it to be more notable or remunerative; today's task increasingly means defending one's art to a culture that expects it to be those things and more.

... In America it has always been the spiritual task of the artist to defend his art to a private self [image error]who wished it to be more notable or remunerative; today's task increasingly means defending one's art to a culture that expects it to be those things and more.

Whether you come to the desk as a writer in secondhand clothes or a CEO in clover, your prescribed oracle is now the same: the dollar. You have before you, like everybody else, the great playing field of the competitive marketplace. You must put your shoulder to the fray and reap a respectable yearly income—or, failing that, at least amass conspicuous honors, appointments, grants, awards—else admit that what you do is not really work. A hobby, maybe, this words-on-paper business. A spinsterish diversion that is quaint and slightly embarrassing in its Victorian echoes. Not work. Artists of late, enthusiastically subscribing to the "career track," offer collusion with and reinforcement of the new pragmatism. As Eric Larsen notes in his fulminating treatise A Nation Gone Blind: America in an Age of Simplification and Deceit, "Inner and outer, public and private, artwork and ad, conscience and collaboration" have never been so interchangeable. What is your mission statement? What are your credentials? Art-making, we're all led to understand, is not a way of life, a calling, a sacrificial act—we've grown up since the age of Rilke's Europe, of mollycoddling "the imagination"; we've learned self-respect. Red-eyed, brain-sore, hunchbacked novelist, ask thy bank account whether you're wasting your time; ask thy "reputation;" heed their replies. Doth they whisper: "Earn thy MFA!" "Get thee a teaching job!" "Network more!" Then jump to it or jump ship.

Says critic Lee Siegel in his book Falling Upwards: Essays in Defense of the Imagination, "The general anxiety now is that if you don't have a gallery, a movie about to be released, or a six-figure advance for a book soon after college, you have bungled opportunities previously unknown to humankind…. Instead of the artist patiently surrendering his ego to the work, he uses his ego to rapidly direct the work … toward the success that seems to be diffused all around him like sunshine." Siegel's bright-eyed hankerer, to continue an admittedly hyperbolic tone, is a capitalist stand-in for the spirited artist of old—a kind of new literary forty-niner, brain ablaze with Fifth Avenue rumors of the latest Big Deal, the who's who of agents, bestseller lists and film options, eager to demonstrate the skills of self-promotion, of being interesting—or even better, incendiary—in interviews. I find it hard to imagine the injunction of John Keats, one of literary history's great unprivileged, having any relevance in such a racket: "The genius of Poetry [read: art] must work out its own salvation in a man; it cannot be matured by law and precept, but by sensation and watchfulness in itself—that which is creative must create itself." ...

September 28, 2010

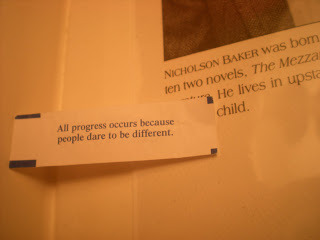

Behind the Flap

It was a fortune cookie strip: "All progress occurs because people dare to be different."

It was a fortune cookie strip: "All progress occurs because people dare to be different."

More of a proverb than a fortune, really, like the contents of most fortune cookies these days -- but how appropriate for Baker's book. And what an affecting reminder of the tangible, material, solitary, and yet simultaneously and mysteriously interpersonal joys that only books in tactile, material (non-digital) form can afford.

September 8, 2010

Prime Passage: Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech of Joseph Brodsky (1987)

September 3, 2010

E-Reading Device? Not For This Young Bibliophile

"...For me, to deny books their physical structure simply ignores far too much of what makes them enjoyable. The commitment they require, the way they force you into a state of simultaneous calm and focus -- these are things ...

July 27, 2010

Prime Passage: The Vivisector by Patrick White (1970)

About the artist-protagonist Hurtle Duffield:

"Suddenly he had begun to live the life for which he had been preparing, or for which he might even have been prepared. At the end of the years of watching, of blundering around inside an inept body, of thinking, or rather, endlessly changing coloured slides in the magic-lantern of the mind, the body had become an instrument, the crude, blurred slides were focusing into what might be called a vision. Most of the day he now spent steadily...

June 19, 2010

25 Ways E-Readers Can't Beat the Old-Fashioned Book

The iPad landed and techno-enthusiasts everywhere hurried, once again, to put on their coroner hats and issue preemptive reports on the death of the old-fashioned book. Now, it may be a different matter for those who crave, in books, the same button-punching dazzle offered by their gadgetry, but to this whisper-of-the-pages-loving reader all the declaiming of late seems a little, um, declamatory.

Before we cue Taps, let's step away from the media juggernaut, take a deep breath of...

June 17, 2010

Prime Passage: Underworld by Don DeLillo

"But you have to stand on a platform and see it coming or you can't know the feelings a writer gets, how the number 5 train comes roaring down the rat alleys and slams out of the tunnel, going whop-pop onto the high tracks, and suddenly there it is, Moonman riding the sky in the heart of the Bronx, over the whole burnt and rusted country, and this is the art of the back streets talking, all the way from Bird, and you can't not see us anymore, you ...