M. Allen Cunningham's Blog, page 19

September 28, 2012

Reason No. 8,972,654 to Be Grateful for Librarians

... Because they stand up to greedy obstructionist corporations!

In an open letter to America's largest publishers dispatched in light of these companies' Draconian restrictions on e-book sales to libraries, American Library Association President Maureen Sullivan brooks no market-tyrants:

In an open letter to America's largest publishers dispatched in light of these companies' Draconian restrictions on e-book sales to libraries, American Library Association President Maureen Sullivan brooks no market-tyrants:

It’s a rare thing in a free market when a customer is refused the ability to buy a company’s product and is told its money is “no good here.” Surprisingly, after centuries of enthusiastically supporting publishers’ products, libraries find themselves in just that position with purchasing e-books from three of the largest publishers in the world. Simon & Schuster, Macmillan, and Penguin have been denying access to their e-books for our nation’s 112,000 libraries and roughly 169 million public library users.President Sullivan goes on to school the robber baron CEOs in the true and higher purpose of book publishing and its long-honored relationship to our public library system. I find the following paragraphs particularly beautiful:

Librarians understand that publishing is not just another industry. It has special and important significance to society. Libraries complement and, in fact, actively support this industry by supporting literacy and seeking to spread an infectious and lifelong love of reading and learning. Library lending encourages patrons to experiment by sampling new authors, topics and genres. This experimentation stimulates the market for books, with the library serving as a de facto discovery, promotion and awareness service for authors and publishers.

Publishers, libraries and other entities have worked together for centuries to sustain a healthy reading ecosystem — celebrating our society’s access to the complete marketplace of ideas. Given the obvious value of libraries to publishers, it simply does not add up that any publisher would continue to lock out libraries. It doesn’t add up for me, it doesn’t add up for ALA’s 60,000 members, and it definitely doesn’t add up for the millions of people who use our libraries every month.

America’s libraries have always served as the “people’s university” by providing access to reading materials and educational opportunity for the millions who want to read and learn but cannot afford to buy the books they need. Librarians have a particular concern for vulnerable populations that may not have any other access to books and electronic content, including individuals and families who are homebound or low-income. To deny these library users access to e-books that are available to others — and which libraries are eager to purchase on their behalf — is discriminatory.

We have met and talked sincerely with many of these publishers. We have sought common ground by exploring new business models and library lending practices. But these conversations only matter if they are followed by action: Simon & Schuster must sell to libraries. Macmillan must implement its proposed pilot. Penguin must accelerate and expand its pilots beyond two urban New York libraries.

We librarians cannot stand by and do nothing while some publishers deepen the digital divide. We cannot wait passively while some publishers deny access to our cultural record. We must speak out on behalf of today’s — and tomorrow’s — readers. The library community demands meaningful change and creative solutions that serve libraries and our readers who rightfully expect the same access to e-books as they have to printed books.(Read the letter in full)

So, which side will you be on? Will you join us in a future of liberating literature for all? Libraries stand with readers, thinkers, writers, dreamers and inventors. Books and knowledge — in all their forms — are essential. Access to them must not be denied.

Published on September 28, 2012 08:41

September 21, 2012

Dear Famous Writers School (P.S.)

“All signs point toward our desire to institutionalize the artist, to integrate him into the community. By means of university courses which teach the ‘technique’ of writing, or which arrange for the communication of the spirit from a fully initiated artist to the neophyte, by means of doctoral degrees in creativity, by means of summer schools and conferences, our democratic impulses fulfill themselves and we undertake to prove that art is a profession like another, in which a young man of reasonably good intelligence has a right to succeed. And this undertaking, which is carried out by administrators and by teachers of relatively simple mind, is in reality the response to the theory of more elaborate and refined minds—of intellectuals—who conceive of the artist as the Commissioner of Moral Sanitation, and who demand that he be given his proper statutory salary without delay. I do not hold with the theory that art grows best in hardship. But I become uneasy—especially if I consider the nature of the best of modern art, its demand that it be wrestled with before it consents to bless us—whenever I hear of plans for its early domestication. These plans seem to me an aspect of the modern fear of being cut off from the social group even for a moment, of the modern indignation at the idea of entering the life of the spirit without proper provision having been made for full security.” -- Lionel Trilling

“All signs point toward our desire to institutionalize the artist, to integrate him into the community. By means of university courses which teach the ‘technique’ of writing, or which arrange for the communication of the spirit from a fully initiated artist to the neophyte, by means of doctoral degrees in creativity, by means of summer schools and conferences, our democratic impulses fulfill themselves and we undertake to prove that art is a profession like another, in which a young man of reasonably good intelligence has a right to succeed. And this undertaking, which is carried out by administrators and by teachers of relatively simple mind, is in reality the response to the theory of more elaborate and refined minds—of intellectuals—who conceive of the artist as the Commissioner of Moral Sanitation, and who demand that he be given his proper statutory salary without delay. I do not hold with the theory that art grows best in hardship. But I become uneasy—especially if I consider the nature of the best of modern art, its demand that it be wrestled with before it consents to bless us—whenever I hear of plans for its early domestication. These plans seem to me an aspect of the modern fear of being cut off from the social group even for a moment, of the modern indignation at the idea of entering the life of the spirit without proper provision having been made for full security.” -- Lionel Trilling “The Situation of the American Intellectual at the Present Time” (1952); found in: The Moral Obligation to be Intelligent, p. 285

Published on September 21, 2012 10:42

September 20, 2012

Dear Famous Writers School...

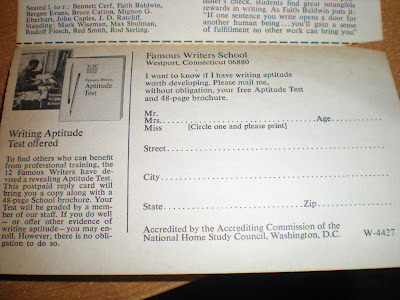

Immersed in a 1969 Fawcett Crest edition of Herzog, a reader notices that a small, yellowing tri-folded brochure has fluttered into his lap.

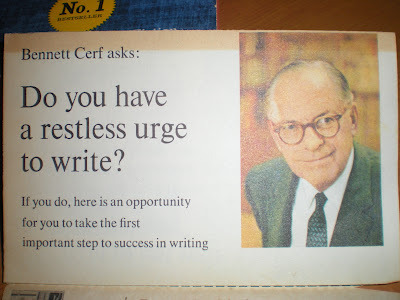

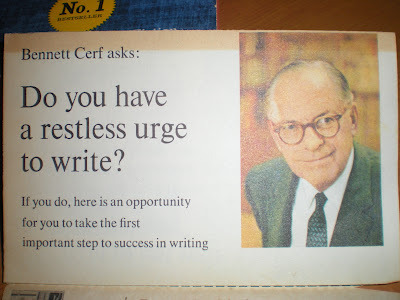

It purports to offer a personal message from Random House founder Bennett Cerf:

Inside the brochure, the "Famous Writers School" and its "revealing Aptitude Test" are extolled as sure means of harnessing creative inspiration via the guidance of famous literary professionals -- and of launching a "successful writing career," finding "success in writing," etc.

Taking a cue from the epistolary impulses of Herzog himself, the reader pens a reply to this transchronological dispatch:

Dear Famous Writers School,

Were you among the first to peddle a secular deliverance from the spiritual pangs of art? Did it start with the likes of you, or could one find your counterpart in the ancient world? You take up, I suppose, an immemorial tradition -- the merchant class has always traded in shortcuts, always sold to the confessant a means of circumventing the rigors of real confession: indulgences, &etc. Even Gutenberg perfected his press with funds raised this way. Yes, but with you something is different. What you offered was a new brand of clergy ordained by sales figures and anointed by the pentecostal light of "fame." It was the number of units sold, it was notoriety, it was mass appeal upon which you based your claim of authority. This was sensible, rational. I see your logic. What was lacking, though, was that old dependable leavener: Shame. It only takes a dash of the stuff to increase the nutrients that enable the questioning of questionable undertakings, and thus it's extremely valuable in moderation (in excess, of course, it will stymie all action). I know, the market, perceived to be an autonomous, self-propelling, and amoral organism, has no place for shame. I can see how you got along fine without it, sure. But listen, had you never married the profane and vacuous standards of the dehumanized marketplace to the holy, humanizing labor of art -- or had you never done so in such a speciously authoritative way and on a such a mass scale -- had you, in short, thought twice before ordaining yourselves high priests in the New Church of the Cynical Arts, we might all be better off today. Maybe.

Yours Truly, ---------

It purports to offer a personal message from Random House founder Bennett Cerf:

Inside the brochure, the "Famous Writers School" and its "revealing Aptitude Test" are extolled as sure means of harnessing creative inspiration via the guidance of famous literary professionals -- and of launching a "successful writing career," finding "success in writing," etc.

Taking a cue from the epistolary impulses of Herzog himself, the reader pens a reply to this transchronological dispatch:

Dear Famous Writers School,

Were you among the first to peddle a secular deliverance from the spiritual pangs of art? Did it start with the likes of you, or could one find your counterpart in the ancient world? You take up, I suppose, an immemorial tradition -- the merchant class has always traded in shortcuts, always sold to the confessant a means of circumventing the rigors of real confession: indulgences, &etc. Even Gutenberg perfected his press with funds raised this way. Yes, but with you something is different. What you offered was a new brand of clergy ordained by sales figures and anointed by the pentecostal light of "fame." It was the number of units sold, it was notoriety, it was mass appeal upon which you based your claim of authority. This was sensible, rational. I see your logic. What was lacking, though, was that old dependable leavener: Shame. It only takes a dash of the stuff to increase the nutrients that enable the questioning of questionable undertakings, and thus it's extremely valuable in moderation (in excess, of course, it will stymie all action). I know, the market, perceived to be an autonomous, self-propelling, and amoral organism, has no place for shame. I can see how you got along fine without it, sure. But listen, had you never married the profane and vacuous standards of the dehumanized marketplace to the holy, humanizing labor of art -- or had you never done so in such a speciously authoritative way and on a such a mass scale -- had you, in short, thought twice before ordaining yourselves high priests in the New Church of the Cynical Arts, we might all be better off today. Maybe.

Yours Truly, ---------

Published on September 20, 2012 11:39

September 19, 2012

"They Deserve Ruthless Suspicion"

In a brilliant long article at Open Letters Monthly, writer Nathan Schneider reminds us about the value of a serious, well-reasoned questioning of the dogmas of techno-consumerism. And he doesn't mince words either.

"The Amazon Kindle is a catastrophe: an interface to a proprietary market managed by a profit-motivated outfit that wants to own and monetize your memory theater. … Apple’s iPad, the overgrown smartphone that has been eating up the Kindle’s market-share in the e-book business, isn’t much better. The slicker Apple’s products get, the more overbearingly they seek to control the user experience. … Until these companies take seriously the needs and, above all, the rights of readers (the human beings, not the machines), they deserve ruthless suspicion. … The point of all this worrying is to dig a spur in the capacity of human creativity to outsmart the enemies of imagination. ..."

Published on September 19, 2012 23:11

September 14, 2012

Submitting (and not)

Dear L,

As you well know, a writer wants most of all to feel understood — and among writers novelists seek this more than any, don’t we? Despite our shy, hermetic ways we’re a starved and eager crew. I became extremely cognizant of this during my first stay at an artist’s colony last summer, surrounded every breakfast and supper by fifteen other writers, all of us earnest, awkward, and cagey in our happiness at being thrown together — and somehow mistrustful of togetherness, cautious of our hunger for it.

This secretive, solitary, often isolating art demands the counterweight of comprehension — being comprehended is the novelist’s version of being a part of things. And yet for all but one percent of us this understanding comes so rarely, or reaches us only vaguely, fragmentarily, as echo or suggestion. As I’ve mentioned, I sent you my manuscript because while it has been skimmed and scattered on many a befuddled editor’s desk (or computer screen, God forbid) over these last nine months, I knew you would comprehend it, L. But you’ve done far more: you’ve taken the time and care to show how you’ve comprehended it. Where editors for whatever addled, mercenary, or blindly subjective reasons have failed and disappointed the book, you have bolstered it. This writer feels his readerly faith restored. And his book, much-rejected thing, feels better about itself.

It can only be itself, in the end. Far from personal dejection, this has been the effect of the rejection — I mean submission — process overall: my own redoubled sense of the book’s completeness and selfness, and yet of some injury or indignity repeatedly done to the book by "professionals." In other words, far from feeling cast down (having done my utmost and written to the best of my powers the book that wanted to be written), I feel, in a parental way, worried for this poor, pure-hearted, overlooked, jabbed and bullied manuscript. How will it find its footing in the world? Who (what editor and readers) will befriend it?

How many publishers have seen it, you ask? I have the tally at about 22 so far. Beyond rote rejectionese like “I was not passionate enough about this,” here, for indignant fun, is an exhibit of some things editors have said, plus my own addenda:

-“I’m not sure I’m confident enough Cunningham can sustain the narrative clearly enough over such a long time span to be satisfying.”

(It’s obvious this guy didn’t finish it, so he wouldn’t know either way.)

-“I thoroughly enjoyed the scope of the piece … [but] I didn’t find it varied enough in theme.”

(Themes crash-course: clocks/years/generations; telegraph/letters/communication; secrecy/silence/silhouettes/shadows; Manifest Destiny/western movement/American vastness/spiritual vacancy; Civil War/family war/American violence; Old World/New World; technology/personal reinvention; Benjamin as latter-day Hamlet... [but you, of course, saw these, L!] )

-“I felt that he was often forgetting the reader … I had trouble connecting with the characters … I just never felt the narrative taking on momentum and pulling me through … [but] I was fascinated by the details of the camps and the letters from the war!”

(How could she like the war letters and not find that they provided momentum?)

-“I found the narrative thread here rather difficult to follow and had a hard time with the letters — they took me away from the characters, and the moment, in a way that I found disruptive.”

(Ditto: letters & momentum)

-“The structure of the book often reveals the characters’ fates before we truly become attached to them … and this tends to diminish the drama of the developing plot.”

(She didn’t read attentively enough to notice what the main plot really is.)

-“It feels very ‘historical’ to me and sometimes that category comes with a feeling of heaviness.”

(Can’t heaviness be good? Isn’t Hardy heavy? James? Toni Morrison?)

I’m not merely crazy or disgruntled, am I, to respond as I do above? Your own response to the book, L, reaffirms that I’m not — that the problem the novel has faced is faulty or distracted reading. A few other editors have — subtly and not-so-subtly — alluded to my “track record” as reason for rejection. And so many of the responses, like the above, contradict one another, that it all comes out a wash. Or, if there is a moral, it’s this: Writer, Follow Thy Own Star, and Be Thee Patient!

I’ve been reading Lionel Trilling lately, and the other day I was struck by something he wrote in 1947 describing a contemporary deification of “reality” (as opposed to flights of imagination) in literary taste. For Trilling, this wish to narrowly define and enshrine reality showed a cultural mistrust of “the internal” which, eerily, seems to me to hold true in today’s literary marketplace:

But I, for one, am a reader who likes a novel to make some demands upon me. And demanding novels do see the light — some anyway, even ones authored by obscurer writers.

Goodness, now I’m afraid I must apologize for writing a jeremiad where I meant only to express appreciation. But hopefully this can bring with it, more than idle complaint, a bit of solidarity, because I know your own beautiful work has lately braved the same climate. I do really appreciate you giving your time, L, and treating the manuscript to such a respectful reading. I feel that you’ve seen in it all that I would hope for a reader to see.

While my prospects of earning any decent advance on this one have all but evaporated, the passionate objective remains to simply see the thing into print. A strange position to find myself in, I must say, having felt all along that this is my strongest — and certainly my most plot-driven (and wouldn’t that mean “commercially viable”?) — book.

Oh, but meanwhile there remains only and as ever the work of doing one’s best and holding one’s ground. And of clearing one’s head of all these matters once at the desk. The work itself is what one has. So much else is beyond one’s control.

Meanwhile, too, we have friendship.

In friendship, with great thanks,

—M

As you well know, a writer wants most of all to feel understood — and among writers novelists seek this more than any, don’t we? Despite our shy, hermetic ways we’re a starved and eager crew. I became extremely cognizant of this during my first stay at an artist’s colony last summer, surrounded every breakfast and supper by fifteen other writers, all of us earnest, awkward, and cagey in our happiness at being thrown together — and somehow mistrustful of togetherness, cautious of our hunger for it.

This secretive, solitary, often isolating art demands the counterweight of comprehension — being comprehended is the novelist’s version of being a part of things. And yet for all but one percent of us this understanding comes so rarely, or reaches us only vaguely, fragmentarily, as echo or suggestion. As I’ve mentioned, I sent you my manuscript because while it has been skimmed and scattered on many a befuddled editor’s desk (or computer screen, God forbid) over these last nine months, I knew you would comprehend it, L. But you’ve done far more: you’ve taken the time and care to show how you’ve comprehended it. Where editors for whatever addled, mercenary, or blindly subjective reasons have failed and disappointed the book, you have bolstered it. This writer feels his readerly faith restored. And his book, much-rejected thing, feels better about itself.

It can only be itself, in the end. Far from personal dejection, this has been the effect of the rejection — I mean submission — process overall: my own redoubled sense of the book’s completeness and selfness, and yet of some injury or indignity repeatedly done to the book by "professionals." In other words, far from feeling cast down (having done my utmost and written to the best of my powers the book that wanted to be written), I feel, in a parental way, worried for this poor, pure-hearted, overlooked, jabbed and bullied manuscript. How will it find its footing in the world? Who (what editor and readers) will befriend it?

How many publishers have seen it, you ask? I have the tally at about 22 so far. Beyond rote rejectionese like “I was not passionate enough about this,” here, for indignant fun, is an exhibit of some things editors have said, plus my own addenda:

-“I’m not sure I’m confident enough Cunningham can sustain the narrative clearly enough over such a long time span to be satisfying.”

(It’s obvious this guy didn’t finish it, so he wouldn’t know either way.)

-“I thoroughly enjoyed the scope of the piece … [but] I didn’t find it varied enough in theme.”

(Themes crash-course: clocks/years/generations; telegraph/letters/communication; secrecy/silence/silhouettes/shadows; Manifest Destiny/western movement/American vastness/spiritual vacancy; Civil War/family war/American violence; Old World/New World; technology/personal reinvention; Benjamin as latter-day Hamlet... [but you, of course, saw these, L!] )

-“I felt that he was often forgetting the reader … I had trouble connecting with the characters … I just never felt the narrative taking on momentum and pulling me through … [but] I was fascinated by the details of the camps and the letters from the war!”

(How could she like the war letters and not find that they provided momentum?)

-“I found the narrative thread here rather difficult to follow and had a hard time with the letters — they took me away from the characters, and the moment, in a way that I found disruptive.”

(Ditto: letters & momentum)

-“The structure of the book often reveals the characters’ fates before we truly become attached to them … and this tends to diminish the drama of the developing plot.”

(She didn’t read attentively enough to notice what the main plot really is.)

-“It feels very ‘historical’ to me and sometimes that category comes with a feeling of heaviness.”

(Can’t heaviness be good? Isn’t Hardy heavy? James? Toni Morrison?)

I’m not merely crazy or disgruntled, am I, to respond as I do above? Your own response to the book, L, reaffirms that I’m not — that the problem the novel has faced is faulty or distracted reading. A few other editors have — subtly and not-so-subtly — alluded to my “track record” as reason for rejection. And so many of the responses, like the above, contradict one another, that it all comes out a wash. Or, if there is a moral, it’s this: Writer, Follow Thy Own Star, and Be Thee Patient!

I’ve been reading Lionel Trilling lately, and the other day I was struck by something he wrote in 1947 describing a contemporary deification of “reality” (as opposed to flights of imagination) in literary taste. For Trilling, this wish to narrowly define and enshrine reality showed a cultural mistrust of “the internal” which, eerily, seems to me to hold true in today’s literary marketplace:

“Whenever we detect evidences of style and thought we suspect that reality is being a little betrayed.”Then, in an essay by Ozick (love this lady) about Saul Bellow, I find this wonder:

“The art of the novel … is in the mix of idiosyncratic language — language imprinted in the writer, like the whorl of the fingertip — and an unduplicable design inscribed on the mind by character and image.”The art of the novel, that is, thrives on the ineluctable peculiarities of style. Singularities of vision, we could say. Or, to come back to Trilling, the “internal” stamp. But don’t you get the sense, as I do, that to write like oneself, to show the whorl, is to earn in the current marketplace editorial scorn? — that is, unless you’re an established DeLillo or Ondaatje. Aren’t we fiction-writers made to feel (subliminally through the culture, or overtly via editors) a little ashamed of pliant language or structure, as if we’re making unreasonable demands upon readers? As if the definition of a fine and viable novel is that which meets the reader at face-value, sans subtext, nuance, subtlety of theme, already fully explicated on every page — i.e., ideal for dipping in and out of while text-messaging or downloading a TV show. According to the general sentiment (at least among major publishers), peculiarity of style is a form of lying or of extreme egotism — and we see what they do to liars and egotists nowadays, in this Age of Disgraced Memoirists.

But I, for one, am a reader who likes a novel to make some demands upon me. And demanding novels do see the light — some anyway, even ones authored by obscurer writers.

Goodness, now I’m afraid I must apologize for writing a jeremiad where I meant only to express appreciation. But hopefully this can bring with it, more than idle complaint, a bit of solidarity, because I know your own beautiful work has lately braved the same climate. I do really appreciate you giving your time, L, and treating the manuscript to such a respectful reading. I feel that you’ve seen in it all that I would hope for a reader to see.

While my prospects of earning any decent advance on this one have all but evaporated, the passionate objective remains to simply see the thing into print. A strange position to find myself in, I must say, having felt all along that this is my strongest — and certainly my most plot-driven (and wouldn’t that mean “commercially viable”?) — book.

Oh, but meanwhile there remains only and as ever the work of doing one’s best and holding one’s ground. And of clearing one’s head of all these matters once at the desk. The work itself is what one has. So much else is beyond one’s control.

Meanwhile, too, we have friendship.

In friendship, with great thanks,

—M

Published on September 14, 2012 08:30

August 29, 2012

"A Place to Curate Ideas and Experiences"

The folks over at the Melville House blog, Moby Lives, are running a marvelous Q&A series featuring some of our country's best indie booksellers. Today's installment spotlights Megan Wade Antieau of Skylight Books in Los Angeles, and is a veritable celebration of indie spirit and erudition. Read, and remember why one buys indie!

"... For me, part of why I’m in bookselling is actually about social change; I am interested in the creation and rebuilding of alternative, localized cultures, as well as more democratic, localized economic institutions. Independent bookstores are a pretty perfect intersection of those two things. I come from both a community organizing and an academic background, but feel that most non-profit models and university models are not helping us do the type of grassroots political and intellectual work that needs to happen for real change in this country. A bookstore, on the other hand, is a place to curate both ideas and experiences in the form of books and conversations for a really broad audience, to constantly prod and provoke people in ways they aren’t necessarily looking for. So seeing that type of slow change happen with our customers is part of what keeps me inspired, as well as those moments where we are clearly aiding the creation of an alternative artistic or political culture in face of the national, monopolistic culture; for instance, every time we have a customer come in who is there to talk as well as shop, who brings in their own poetry or comics for consignment at the same time as they’re picking up both a staff recommendation and something from another local author. ..."

Published on August 29, 2012 08:50

August 18, 2012

From the Dept. of Cultural Envy: Argentine Writers Granted Literary Pensions

Some societies regard the work of the imagination as a thing of vital social value. From the New York Times of August 12, 2012:

The city of Buenos Aires now gives pensions to published writers in a program that attempts to strengthen the “vertebral column of society,” as drafters of the law described their goal. Since its enactment recently, more than 80 writers have been awarded pensions, which can reach almost $900 a month, supplementing often meager retirement income. ...And there are plans to implement the pension program throughout Argentina:

“I’m very optimistic about the approval of our bill,” Mr. Junio said. “There’s a general recognition of the transcendent role that writers have had in forging our society.”Culture shock! Try to imagine an American legislator speaking to the "transcendent role" of the literary arts in the U.S.

Here in Buenos Aires, the requirements for obtaining the pension are fairly strict. A writer must be at least 60 and the author of at least five books released by known publishing houses, ruling out self-published writers. Authors of tomes on law, medicine or other technical matters need not apply, as the pensions are limited to writers of fiction, poetry, literary essays and plays. …

“We prefer not to call it a pension, but rather a subsidy in recognition of literary activity,” said Graciela Aráoz, a poet who is president of the Argentine Writers Society, which has more than 800 members. “In the end, this is about fortifying the pleasurable act of reading, which prevents us from turning into the equivalent of zombies.” ...

Published on August 18, 2012 08:21

August 17, 2012

Prime Passages: Kenneth Clark & Henry James on Civilization

From Civilisation, the illustrated companion book to Lord Kenneth Clark's 1969 BBC documentary of the same name:

What is civilization? I don’t know. I can’t define it in abstract terms—yet. But I think I can recognize it when I see it, and I am looking at it now [Paris].From The Master, Volume 5 of Leon Edel's towering biography, Henry James: A Life:

… At certain epochs man has felt conscious of something about himself—body and spirit—which was outside the day-to-day struggle for existence and the night-to-night struggle with fear; and he has felt the need to develop these qualities of thought and feeling so that they might approach as nearly as possible to an ideal of perfection—reason, justice, physical beauty, all of them in equilibrium. He has managed to satisfy this need in various ways—through myths, through dance and song, through systems of philosophy and through the order that he has imposed on the visible world. … However complex and solid [civilization] seems, it is actually quite fragile. It can be destroyed. What are its enemies? Well, first of all fear—far of war, fear of invasion, fear of plague and famine, that makes it simply not worthwhile constructing things, or planting trees or even planting next year’s crops. And fear of the supernatural, which means that you daren’t question anything or change anything. The late antique world was full of meaningless rituals, mystery religions, that destroyed self-confidence. And then exhaustion, the feeling of hopelessness which can overtake people even with a high degree of prosperity. There is a poem by the modern Greek poet, Cavafy, in which he imagines the people of an antique town like Alexandria waiting every day for the barbarians to come and sack the city. Finally the barbarians move off somewhere else and the city is saved; but the people are disappointed; it would have been better than nothing. Of course, civilization requires a modicum of material prosperity—enough to provide a little leisure. But, far more, it requires confidence—confidence in the society in which one lives, belief in its philosophy, belief in its laws, and confidence in one’s own mental powers. … People sometimes think that civilization consists in fine sensibilities and good conversation and all that. These can be among the agreeable results of civilization, but they are not what make a civilization, and a society can have these amenities and yet be dead and rigid. So if one asks why the civilization of Greece and Rome collapsed, the real answer is that it was exhausted. And the first invaders of the Roman empire became exhausted too. As so often happens, they seem to have succumbed to the same weakness as the people they conquered. … These early invaders have been aptly compared to the English in India in the eighteenth century—there for what they could get out of it, taking part in the administration if it paid them, contemptuous of the traditional culture, except insofar as it provided precious metals… Civilization means something more than energy and will and creative power: something the early Norsemen hadn’t got, but which, even in their time, was beginning to reappear in Western Europe. How can I define it? Well, very shortly, a sense of permanence. (Civilisation; pp.1-14)

New York had created not a social order but an extemporized utility-life that substituted the glamour of technology for the deep-rooted foundations of existence. … Man could create so blindly and so crudely the foundations of inevitable ‘blight.’ … Civilization meant order, composition, restraint, moderation, beauty, duration. It meant creation of a way of life that ministered to man’s finest qualities and potential. Using this standard of measurement, James found America terribly wanting. It was founded on violence, plunder, loot, commerce; its monuments were built neither for beauty nor for glory, but for obsolescence. It put science and technology to the service of the profit motive, and this would lead to the decay of human forms and human values. Older nations had known how to rise above shopkeeping; they had not made a cult of ‘business’ and of ‘success.’ And then James hated the continental ‘bigness’ of America. Homogeneity, rootedness, manners—modes of life—these were his materials, and everywhere James looked he found there had been an erosion of the standards and forms necessary to a novelist, necessary also to civilization. The self-indulgence and self-advertisement of the plunderers was carried over to the indulging of their young. Americans had interpreted freedom as a license to plunder.

(The Master: Henry James, Vol.5, pp.291-317)

Published on August 17, 2012 09:32

June 6, 2012

M. Allen Cunningham's Date of Disappearance Now for Sale!

Available for purchase direct from the publisher here. Available through Powell's Books in Portland, Oregon (and in stock at other fine indie bookstores soon). ISBN: 978-0-615-58931-2 Retail price: $17.95 208 pages5.5x8.5 with French flaps

www.Atelier26Books.com

Published on June 06, 2012 21:00

Date of Disappearance Now for Sale!

Available for purchase direct from the publisher here. Available through Powell's Books in Portland, Oregon (and in stock at other fine indie bookstores soon). ISBN: 978-0-615-58931-2 Retail price: $17.95 208 pages5.5x8.5 with French flaps

www.Atelier26Books.com

Published on June 06, 2012 21:00