M. Allen Cunningham's Blog, page 22

June 5, 2011

Announcing a Special Offering

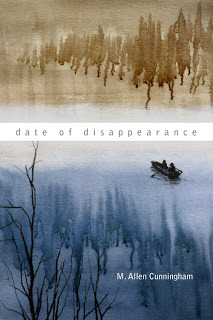

FORTHCOMING through your finest independent booksellers:

Date of Disappearance: assorted stories

Date of Disappearance: assorted stories

The new work of fiction by M. Allen Cunningham

in illustrated limited edition hardcover

(enough said for now ... )

Published on June 05, 2011 16:36

May 6, 2011

Prime Passage from On Grief & Reason by Joseph Brodsky: "You become what you read"

Found in "An Immodest Proposal," a speech delivered at the Library of Congress in 1991:

"In the process of composition a poet employs—by and large unwittingly—the two main modes of cognition available to our species: Occidental and Oriental. (Of course both modes are available whenever you find frontal lobes, but different traditions have employed them with different degrees of prejudice.) The first puts a high premium on the rational, on analysis. In social terms, it is accompanied by man's self-assertion and generally is exemplified by Descartes's "Cogito ergo sum." The second relies mainly on intuitive synthesis, calls for self-negation, and is best represented by the Buddha. In other words, a poem offers you a sample of complete, not slanted, human intelligence at work. This is what constitutes the chief appeal of poetry, quite apart from its exploiting rhythmic and euphonic properties of the language which are in themselves quite revelatory. A poem, as it were, tells its reader, "Be like me." And at the moment of reading you become what you read, you become the state of the language which is a poem, and its epiphany or its revelation is yours. They are still yours once you shut the book, since you can't revert to not having had them. That's what evolution is all about. … The purpose of evolution, believe it or not, is beauty, which survives it all and generates truth simply by being a fusion of the mental and the sensual. As it is always in the eye of the beholder, it can't be wholly embodied save in words: that's what ushers in a poem."(On Grief & Reason, p.206)

"In the process of composition a poet employs—by and large unwittingly—the two main modes of cognition available to our species: Occidental and Oriental. (Of course both modes are available whenever you find frontal lobes, but different traditions have employed them with different degrees of prejudice.) The first puts a high premium on the rational, on analysis. In social terms, it is accompanied by man's self-assertion and generally is exemplified by Descartes's "Cogito ergo sum." The second relies mainly on intuitive synthesis, calls for self-negation, and is best represented by the Buddha. In other words, a poem offers you a sample of complete, not slanted, human intelligence at work. This is what constitutes the chief appeal of poetry, quite apart from its exploiting rhythmic and euphonic properties of the language which are in themselves quite revelatory. A poem, as it were, tells its reader, "Be like me." And at the moment of reading you become what you read, you become the state of the language which is a poem, and its epiphany or its revelation is yours. They are still yours once you shut the book, since you can't revert to not having had them. That's what evolution is all about. … The purpose of evolution, believe it or not, is beauty, which survives it all and generates truth simply by being a fusion of the mental and the sensual. As it is always in the eye of the beholder, it can't be wholly embodied save in words: that's what ushers in a poem."(On Grief & Reason, p.206)

Published on May 06, 2011 20:19

Prime Passage from On Grief & Reason by Joseph Brodsky: "You become what you read"

Found in "An Immodest Proposal," a speech delivered at the Library of Congress in 1991:

"In the process of composition a poet employs—by and large unwittingly—the two main modes of cognition available to our species: Occidental and Oriental. (Of course both modes are available whenever you find frontal lobes, but different traditions have employed them with different degrees of prejudice.) The first puts a high premium on the rational, on analysis. In social terms, it is accompanied by man's self-assertion and generally is exemplified by Descartes's "Cogito ergo sum." The second relies mainly on intuitive synthesis, calls for self-negation, and is best represented by the Buddha. In other words, a poem offers you a sample of complete, not slanted, human intelligence at work. This is what constitutes the chief appeal of poetry, quite apart from its exploiting rhythmic and euphonic properties of the language which are in themselves quite revelatory. A poem, as it were, tells its reader, "Be like me." And at the moment of reading you become what you read, you become the state of the language which is a poem, and its epiphany or its revelation is yours. They are still yours once you shut the book, since you can't revert to not having had them. That's what evolution is all about. … The purpose of evolution, believe it or not, is beauty, which survives it all and generates truth simply by being a fusion of the mental and the sensual. As it is always in the eye of the beholder, it can't be wholly embodied save in words: that's what ushers in a poem."(On Grief & Reason, p.206)

"In the process of composition a poet employs—by and large unwittingly—the two main modes of cognition available to our species: Occidental and Oriental. (Of course both modes are available whenever you find frontal lobes, but different traditions have employed them with different degrees of prejudice.) The first puts a high premium on the rational, on analysis. In social terms, it is accompanied by man's self-assertion and generally is exemplified by Descartes's "Cogito ergo sum." The second relies mainly on intuitive synthesis, calls for self-negation, and is best represented by the Buddha. In other words, a poem offers you a sample of complete, not slanted, human intelligence at work. This is what constitutes the chief appeal of poetry, quite apart from its exploiting rhythmic and euphonic properties of the language which are in themselves quite revelatory. A poem, as it were, tells its reader, "Be like me." And at the moment of reading you become what you read, you become the state of the language which is a poem, and its epiphany or its revelation is yours. They are still yours once you shut the book, since you can't revert to not having had them. That's what evolution is all about. … The purpose of evolution, believe it or not, is beauty, which survives it all and generates truth simply by being a fusion of the mental and the sensual. As it is always in the eye of the beholder, it can't be wholly embodied save in words: that's what ushers in a poem."(On Grief & Reason, p.206)

Published on May 06, 2011 20:19

March 19, 2011

Goodbye to Bookstores? Not Yet!

I have a short feature essay in the Oregonian for Sunday, March 13. It deals with the rise of the e-book and the importance, as I see it, of standing up for community and media plurality by supporting bookstores and libraries.

Permit no farewell to the Age of the Bookstore! Clang in my brain goes the thought, prompted by news of Borders, bookselling behemoth, declaring bankruptcy and shuttering stores by a third. Even Borders! Then locally comes word that Powell's must prune personnel—and in southeast Portland the bright rooms of Looking Glass Books, 38-year cultural institution, are to be stripped and darkened. Outside a banner reads: for lease. One February morning I stand before it, morosely wishful. Had I the bucks and business acumen, I'd charge in and make a quixotic offer myself. To the staff I'd say, "Stay! We'll hold this line together!" Instead, clueless with a balance book and already mortgaged to my eyebrows, I shuffle inside to loiter amid liquidation signs, to suck in lovely ink-and-paper aromas while fondling volumes in farewell, and to eavesdrop on the regrets of other patrons. "We've loved coming here," the owner is told. "How we'll miss it!" "Sorry to see you go!" Note to self: business acumen was never lacking here. This store's got its clientele. No, the problem cited here and at Powell's—and even at Borders HQ—is the immaterial imp known as, yes, the e-book. Can this be? While one dawdled innocently in the ever-bright chambers of the Internet, flashed-at by ads, teased by Twitter, chloroformed by Facebook, something sinister happened to one's world. The physical bookstore—actual space-consuming locus of tangible, shelvable books (and ideally of a community's unique intellectual life)—came under assault from a fusillade of pixels. Pixels!Read the rest here.

Published on March 19, 2011 15:25

February 14, 2011

Prime Passage: Lionel Trilling (1952)

From Trilling's "The Situation of the American Intellectual at the Present Time" (1952), his contribution to a Partisan Review symposium on the subject. Prophetic?

"For purposes of the artist's salvation, it is best not to speak of the artist at all. It is best to think of him as crazy, foolish, inspired—as an unconditionable kind of man—and to make no provision for him until he appears in person and demands it. Our attitude to the artist is deteriorating as our sense of his need increases. It seems to me that the more we think about doing something for the artist, the less we think of him as Master, and the more we think of him as Postulant or Apprentice. Indeed, it may be coming to be true that for us the Master is the not the artist himself, but the great philanthropic Foundation, which brings artists into being, whose creative act the artist is. All signs point toward our desire to institutionalize the artist, to integrate him into the community. By means of university courses which teach the 'technique' of writing, or which arrange for the communication of the spirit from a fully initiated artist to the neophyte, by means of doctoral degrees in creativity, by means of summer schools and conferences, our democratic impulses fulfill themselves and we undertake to prove that art is a profession like another, in which a young man of reasonably good intelligence has a right to succeed. And this undertaking, which is carried out by administrators and by teachers of relatively simple mind, is in reality the response to the theory of more elaborate and refined minds—of intellectuals—who conceive of the artist as the Commissioner of Moral Sanitation, and who demand that he be given his proper statutory salary without delay. I do not hold with the theory that art grows best in hardship. But I become uneasy—especially if I consider the nature of the best of modern art, its demand that it be wrestled with before it consents to bless us—whenever I hear of plans for its early domestication. These plans seem to me an aspect of the modern fear of being cut off from the social group even for a moment, of the modern indignation at the idea of entering the life of the spirit without proper provision having been made for full security."

"For purposes of the artist's salvation, it is best not to speak of the artist at all. It is best to think of him as crazy, foolish, inspired—as an unconditionable kind of man—and to make no provision for him until he appears in person and demands it. Our attitude to the artist is deteriorating as our sense of his need increases. It seems to me that the more we think about doing something for the artist, the less we think of him as Master, and the more we think of him as Postulant or Apprentice. Indeed, it may be coming to be true that for us the Master is the not the artist himself, but the great philanthropic Foundation, which brings artists into being, whose creative act the artist is. All signs point toward our desire to institutionalize the artist, to integrate him into the community. By means of university courses which teach the 'technique' of writing, or which arrange for the communication of the spirit from a fully initiated artist to the neophyte, by means of doctoral degrees in creativity, by means of summer schools and conferences, our democratic impulses fulfill themselves and we undertake to prove that art is a profession like another, in which a young man of reasonably good intelligence has a right to succeed. And this undertaking, which is carried out by administrators and by teachers of relatively simple mind, is in reality the response to the theory of more elaborate and refined minds—of intellectuals—who conceive of the artist as the Commissioner of Moral Sanitation, and who demand that he be given his proper statutory salary without delay. I do not hold with the theory that art grows best in hardship. But I become uneasy—especially if I consider the nature of the best of modern art, its demand that it be wrestled with before it consents to bless us—whenever I hear of plans for its early domestication. These plans seem to me an aspect of the modern fear of being cut off from the social group even for a moment, of the modern indignation at the idea of entering the life of the spirit without proper provision having been made for full security."

Published on February 14, 2011 23:41

February 8, 2011

Prime Passage: "The Responsibility of the Poet" by Wendell Berry (1988)

(From the essay "The Responsibility of the Poet," found in Berry's book, What Are People For?)

"A poem reminds us...of the spiritual elation that we call 'inspiration' or 'gift.' Or perhaps we ought to say that it should do so, it should be humble enough to do so, because we know that no permanently valuable poem is made by the merely intentional manipulation of its scrutable components. Hence, it reminds us of love. It is amateur work, lover's work. What we now call 'professionalism' is anathema to it. A good poem reminds us of love because it cannot be written or read in distraction; it cannot be read or understood by anyone thinking of praise or publication or promotion. ...

"We are now inclined to make much of this distinction between amateur and professional, but it is reassuring to know that these words first were used in opposition to each other less than two hundred years ago. Before the first decade of the nineteenth century, no one felt the need for such a distinction -- which established itself, I suppose, because of the industrial need to separate love from work, and so it was made at first to discriminate in favor of professionalism. To those who wish to defend the possibility of good or responsible work, it remains useful today because of the need to discriminate against professionalism.

"Professional standards, the standards of ambition and selfishness, are always sliding downward toward expense, ostentation, and mediocrity. They tend always to narrow the ground of judgment. But amateur standards, the standards of love, are always straining upward toward the humble and the best. They enlarge the ground of judgment. The context of love is the world." (p.89-90)

"A poem reminds us...of the spiritual elation that we call 'inspiration' or 'gift.' Or perhaps we ought to say that it should do so, it should be humble enough to do so, because we know that no permanently valuable poem is made by the merely intentional manipulation of its scrutable components. Hence, it reminds us of love. It is amateur work, lover's work. What we now call 'professionalism' is anathema to it. A good poem reminds us of love because it cannot be written or read in distraction; it cannot be read or understood by anyone thinking of praise or publication or promotion. ...

"We are now inclined to make much of this distinction between amateur and professional, but it is reassuring to know that these words first were used in opposition to each other less than two hundred years ago. Before the first decade of the nineteenth century, no one felt the need for such a distinction -- which established itself, I suppose, because of the industrial need to separate love from work, and so it was made at first to discriminate in favor of professionalism. To those who wish to defend the possibility of good or responsible work, it remains useful today because of the need to discriminate against professionalism.

"Professional standards, the standards of ambition and selfishness, are always sliding downward toward expense, ostentation, and mediocrity. They tend always to narrow the ground of judgment. But amateur standards, the standards of love, are always straining upward toward the humble and the best. They enlarge the ground of judgment. The context of love is the world." (p.89-90)

Published on February 08, 2011 18:55

Prime Passage: "The Responsibility of the Poet" by Wendell Berry (1988)

(From the essay "The Responsibility of the Poet," found in Berry's book, What Are People For?)

"A poem reminds us...of the spiritual elation that we call 'inspiration' or 'gift.' Or perhaps we ought to say that it should do so, it should be humble enough to do so, because we know that no permanently valuable poem is made by the merely intentional manipulation of its scrutable components. Hence, it reminds us of love. It is amateur work, lover's work. What we now call 'professionalism' is anathema to it. A good poem reminds us of love because it cannot be written or read in distraction; it cannot be read or understood by anyone thinking of praise or publication or promotion. ...

"We are now inclined to make much of this distinction between amateur and professional, but it is reassuring to know that these words first were used in opposition to each other less than two hundred years ago. Before the first decade of the nineteenth century, no one felt the need for such a distinction -- which established itself, I suppose, because of the industrial need to separate love from work, and so it was made at first to discriminate in favor of professionalism. To those who wish to defend the possibility of good or responsible work, it remains useful today because of the need to discriminate against professionalism.

"Professional standards, the standards of ambition and selfishness, are always sliding downward toward expense, ostentation, and mediocrity. They tend always to narrow the ground of judgment. But amateur standards, the standards of love, are always straining upward toward the humble and the best. They enlarge the ground of judgment. The context of love is the world." (p.89-90)

"A poem reminds us...of the spiritual elation that we call 'inspiration' or 'gift.' Or perhaps we ought to say that it should do so, it should be humble enough to do so, because we know that no permanently valuable poem is made by the merely intentional manipulation of its scrutable components. Hence, it reminds us of love. It is amateur work, lover's work. What we now call 'professionalism' is anathema to it. A good poem reminds us of love because it cannot be written or read in distraction; it cannot be read or understood by anyone thinking of praise or publication or promotion. ...

"We are now inclined to make much of this distinction between amateur and professional, but it is reassuring to know that these words first were used in opposition to each other less than two hundred years ago. Before the first decade of the nineteenth century, no one felt the need for such a distinction -- which established itself, I suppose, because of the industrial need to separate love from work, and so it was made at first to discriminate in favor of professionalism. To those who wish to defend the possibility of good or responsible work, it remains useful today because of the need to discriminate against professionalism.

"Professional standards, the standards of ambition and selfishness, are always sliding downward toward expense, ostentation, and mediocrity. They tend always to narrow the ground of judgment. But amateur standards, the standards of love, are always straining upward toward the humble and the best. They enlarge the ground of judgment. The context of love is the world." (p.89-90)

Published on February 08, 2011 18:55

Prime Passage: The Paris Review Interview with David McCullough

"I write on an old Royal typewriter, a beauty! ...I've written all my books on it. It was made about 1941 and it works perfectly. I have it cleaned and oiled about once every book and the roller has to be replaced now and then. Otherwise it's the same machine. Imagine--it's more than fifty years old and it still does just what it was built to do! There's not a thing wrong with it.

"I love putting paper in. I love the way the keys come up and actually print the letters. I love it when I swing that carriage and the bell rings like an old trolley car. I love the feeling of making something with my hands. People say, But with a computer you could go so much faster. Well, I don't want to go faster. If anything, I should go slower. I don't think all that fast. They say, But you could change things so readily. I can change things very readily as it is. I take a pen and draw a circle around what I want to move up or down or wherever and then I retype it. Then they say, But you wouldn't have to retype it. But when I'm retyping I'm also rewriting. And I'm listening, hearing what I've written. Writing should be done for the ear. Rosalee reads aloud wonderfully and it's a tremendous help to me to hear her speak what I've written. Or sometimes I read it to her. It's so important. You hear things that are wrong, that call for editing."

"I love putting paper in. I love the way the keys come up and actually print the letters. I love it when I swing that carriage and the bell rings like an old trolley car. I love the feeling of making something with my hands. People say, But with a computer you could go so much faster. Well, I don't want to go faster. If anything, I should go slower. I don't think all that fast. They say, But you could change things so readily. I can change things very readily as it is. I take a pen and draw a circle around what I want to move up or down or wherever and then I retype it. Then they say, But you wouldn't have to retype it. But when I'm retyping I'm also rewriting. And I'm listening, hearing what I've written. Writing should be done for the ear. Rosalee reads aloud wonderfully and it's a tremendous help to me to hear her speak what I've written. Or sometimes I read it to her. It's so important. You hear things that are wrong, that call for editing."

Published on February 08, 2011 18:43

Prime Passage: The Paris Review Interview with David McCullough

"I write on an old Royal typewriter, a beauty! ...I've written all my books on it. It was made about 1941 and it works perfectly. I have it cleaned and oiled about once every book and the roller has to be replaced now and then. Otherwise it's the same machine. Imagine--it's more than fifty years old and it still does just what it was built to do! There's not a thing wrong with it.

"I love putting paper in. I love the way the keys come up and actually print the letters. I love it when I swing that carriage and the bell rings like an old trolley car. I love the feeling of making something with my hands. People say, But with a computer you could go so much faster. Well, I don't want to go faster. If anything, I should go slower. I don't think all that fast. They say, But you could change things so readily. I can change things very readily as it is. I take a pen and draw a circle around what I want to move up or down or wherever and then I retype it. Then they say, But you wouldn't have to retype it. But when I'm retyping I'm also rewriting. And I'm listening, hearing what I've written. Writing should be done for the ear. Rosalee reads aloud wonderfully and it's a tremendous help to me to hear her speak what I've written. Or sometimes I read it to her. It's so important. You hear things that are wrong, that call for editing."

"I love putting paper in. I love the way the keys come up and actually print the letters. I love it when I swing that carriage and the bell rings like an old trolley car. I love the feeling of making something with my hands. People say, But with a computer you could go so much faster. Well, I don't want to go faster. If anything, I should go slower. I don't think all that fast. They say, But you could change things so readily. I can change things very readily as it is. I take a pen and draw a circle around what I want to move up or down or wherever and then I retype it. Then they say, But you wouldn't have to retype it. But when I'm retyping I'm also rewriting. And I'm listening, hearing what I've written. Writing should be done for the ear. Rosalee reads aloud wonderfully and it's a tremendous help to me to hear her speak what I've written. Or sometimes I read it to her. It's so important. You hear things that are wrong, that call for editing."

Published on February 08, 2011 18:43

January 8, 2011

Prime Passage: Saul Bellow: Letters

From Bellow's letter to the Guggenheim Foundation, January 20, 1953:

"I am perfectly sure that he will become a major novelist. He has every prerequisite: the personal, definite style, the emotional resources, the understanding of character, the dramatic sense and the intelligence. He understands what the tasks of an imaginative writer of today are. Not to be appalled by these tasks is in and of itself a piece of heroism. Imagination has been steadily losing prestige in American life, it seems to me, for a long time. I am speaking of the poetic imagination. Inferior kinds of imagination have prospered, but the poetic has less credit than ever before. Perhaps that is because there is less room than ever for the personal, spacious, unanxious and free, for the unprepared, unorganized and spontaneous elements from which poetic imagination springs. It is upon writers like Mr. Malamud that the future of literature in America depends, writers who have not sought to protect themselves by joining schools or by identification with prevailing tastes and tendencies. The greatest threat to writing today is the threat of conformism. Art is the speech of an artist, of an individual, and it testifies to the power of individuals to speak and to the power of other individuals to listen and understand.

"Literal-minded critics of Mr. Malamud's novel, The Natural, complained that it was not about true-to-life baseball players and failed entirely to see that it was a parable of the man of great endowments, or myth of the champion. I have immense faith in Mr. Malamud's power to make himself understood. I should be very happy to hear that he had become a Guggenheim fellow." (p.118)

Buy Bellow's Letters here.

"I am perfectly sure that he will become a major novelist. He has every prerequisite: the personal, definite style, the emotional resources, the understanding of character, the dramatic sense and the intelligence. He understands what the tasks of an imaginative writer of today are. Not to be appalled by these tasks is in and of itself a piece of heroism. Imagination has been steadily losing prestige in American life, it seems to me, for a long time. I am speaking of the poetic imagination. Inferior kinds of imagination have prospered, but the poetic has less credit than ever before. Perhaps that is because there is less room than ever for the personal, spacious, unanxious and free, for the unprepared, unorganized and spontaneous elements from which poetic imagination springs. It is upon writers like Mr. Malamud that the future of literature in America depends, writers who have not sought to protect themselves by joining schools or by identification with prevailing tastes and tendencies. The greatest threat to writing today is the threat of conformism. Art is the speech of an artist, of an individual, and it testifies to the power of individuals to speak and to the power of other individuals to listen and understand.

"Literal-minded critics of Mr. Malamud's novel, The Natural, complained that it was not about true-to-life baseball players and failed entirely to see that it was a parable of the man of great endowments, or myth of the champion. I have immense faith in Mr. Malamud's power to make himself understood. I should be very happy to hear that he had become a Guggenheim fellow." (p.118)

Buy Bellow's Letters here.

Published on January 08, 2011 09:02