DeAnna Knippling's Blog, page 72

November 3, 2013

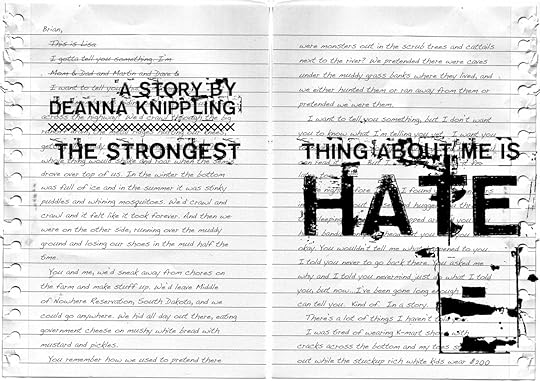

Coming soon in Black Static…

October 23, 2013

Editing Tips for Editors

Several editing observations have come up over the last week. I’m not sure they’re going to do anybody else any good, but at the very least it’ll help me process. This is coming out kind of rough and mean, I think at least partially because I’m trying to beat myself into submission, and if nothing else I find my (former?) personal bad habits more than a little irritating. Sorry. Maybe I could be tactful about this later. Like in ten years or so. Although really I expect by then to be repeating these points, only louder and more rudely, having almost completely forgotten I’ve previously bitched about them here. C’est la vie.

–

There’s a difference between the editing that one does in a critique group and the editing that one does for a client. The editing that one does for a client may not have ego to it. What you like, as a reader, doesn’t mean anything. Praise? Criticism? You have to do it in a critique group; it’s expected. Clients shouldn’t have to care if they don’t want to. Your opinion is a side comment, something that goes in a cover email (or doesn’t get said at all) and not in the document redlines, except on very rare occasions, and then only when it’s praise. Do you understand what the author’s trying to do? No? Then don’t ask repeatedly in the manuscript. If you dislike a character, then you can disliked them in the privacy of your own mind. Not in the comments. You’re getting paid for those comments; they better be a value-add.

–

Review your comments and remove every single one of them that you can.

–

Genre matters. Audience matters. Context matters. If your client is writing pulp, don’t edit them like they’re writing literary. You are responsible to know the difference and to avoid genres you don’t know well enough to edit. Otherwise, you will just piss the author off, and they will speak ill of you to others. If you dislike the work, remove yourself as gracefully as possible.

–

If you never, ever bitch about poor writing again it will still not be soon enough. Whether you are bitching about a client in particular or “clients in general,” as an editor, you’re kind of like a confessor. Keep your mouth shut. If writers were perfect, they wouldn’t need editors. On top of which, when editors are in editor mode, we’re assholes. Every piece of writing has issues, even after having been edited. Even ones edited by a professional editor. The general public can bitch about typos. Readers can bitch about typos. An editor bitching about typos is just someone bragging up their editing skills. Keep it in your pants or send a private email, buddy.

–

And just because you know how to write better than the writer does–even if it’s only in one technique or another–that doesn’t mean you get to try to improve the writer. –I have a problem with this. ”Oh, let me helpfully teach you how to structure a scene.” Especially in cases when I’m not being paid to do content editing. This just gets frustrating on both parts, as more and more time gets sunk into a project, and someone ends up getting screwed. Let the writer learn at their own pace and back the hell off. So what if their descriptions could be better? You might consider telling them once, tactfully, in a cover email.

–

Look it up. Ha ha, yes, you’ve been editing for twenty years now, of course you know what you’re doing. Look it up.

–

If you see a writer break a rule consistently, remove your redlines and comments about it, unless the rule-breaking may cause the author issues with their readers. For example, a consistently misspelled word–don’t fix it, unless it’s obvious that it’s not a dialect or slang or some other intentional change. If you’re feeling paranoid, you can flag it once and go back and fix it if the author says, “Ooh, that’s wrong, good catch.” Otherwise you’re wasting the author’s time as they dejectedly “fix” a bunch of stuff, then realize they didn’t have to in the first place. Even worse: pretend that you’re right even though you’re violating the author’s intentions.

–

No more hardcopy copyediting. Ever. Again. It’s a lot of work and prevents tact.

–

Every time you change or comment on something, you’re sucking up a little bit of the author’s willpower, even if it’s a good change/comment. If you can point out one thing that covers many items–if you can put something tactfully into a cover email–if you can shoot a quick email question before you flag fifty things–then do it that way. If you’re editing under another editor’s direction (or, in a small press, sometimes it’s the publisher’s direction), then talk to them first. Don’t drain the writer. They need to have the willpower to write more than you need to prove that you can spot errors. Trust me, you’re not impressing anybody with even a lick of experience by bleeding all over the page.

–

Don’t change the writer’s punctuation scheme. Yes. That means you…and you…and you. And often me. Change it for clarity? Yes, but only as appropriate, and if the author doesn’t use the Harvard comma on a consistent basis, then you will spread your legs and take that extra comma for the team. Deliberate run-on sentences? Bite your tongue and think of England.

–

Writers: There are editors that make you excited. Stressed, but excited. There are editors who leave you feeling drained and hurting with a stubbed toe of the mind (or worse). Sometimes you can’t avoid the latter. Some will improve a manuscript; others will pick it to pieces and suck the magic out. Learning to be edited is its own skill. You win some and you lose some. If someone else is paying for your work, then you might need to lose a few in order to win the ones that are really important. Lord knows I have. But if you’re paying the editor? You win. You just always win. And if the editor gives you attitude about that, then get another editor.

–

Again, let me apologize to any clients–past, current, and future–whose mental and creative toes I stub, in one way or another. I am often wrong, cranky while editing, and arrogant. But you win. Always. In the end, you win, and don’t let me tell you any different. It just makes me a worse editor.

October 16, 2013

Aunt Margie

I’m a writer, so here it is: My Aunt Margie passed away on Monday, of probably a massive stroke. Dad called to tell me. This is Dad: he always starts out the phone calls, and then Mom takes over. I think it’s because there’s only so much time he can stand to be social, and he has to work himself up to it. I’m his daughter, but I don’t think that really makes it any easier to talk on the phone. He has three daughters and two sons; he came from a family of nine kids. As the youngest, he’s had some of them pass before him. Margie is his older sister–if I’m interpreting things right, the one who mothered him, as a kid.

He told me Margie was gone. And then. Well, I knew I shouldn’t push for details, but I listened. And he told me he’d talked to her on Friday, he had a good talk with her. He’d been going to go over and cut wood for them, but it’d rained, and the wood would have been too wet. Personally, I’m terrified of chainsaws, but I think he likes them. He said the last time he went over there to cut wood, he didn’t tell anyone, and she chewed him out for it. Not…chewed him out. Said something. Teased him about it, probably. We’re a family of teasers and crap-givers.

He called again Monday afternoon, and we talked about the service. Margie wanted her body donated to science, but they can wait until after the service, he said. Then we talked about the weather. As I get older this makes more sense. Every time you talk about the weather, you’re talking about everyone. This last couple of years in Colorado, I saw it: fires that swept over your friends, taking everything from some, barely touching others. Flooding, the same way. When you talk about the weather you’re saying life goes on but you have to pay attention to it while it’s going on.

We do have to go on. I do. I thought it wasn’t hitting me as bad as other people who have passed over the last few years: Margie led a good life, both as a good person and as a life that wasn’t lived out in shades of despair and numbness, and believe me, that’s worth celebrating rather than mourning, because I’ve seen both now. But I’m having trouble functioning this morning, because in order to go on, I have to go on with Aunt Margie, rather than separate from her. I can’t leave her behind.

It’s a family tradition to tease each other, and I’m sure there’s lots of stories going around about goofy things she’s done. Or there will be those stories going around, or there should be. There’s always some story, with them, of some dumbass thing you’ve done that tells everyone exactly who you are. In a group of people plagued with eyeroll-worthy orneriness, it’s probably vital that these things get passed around. Plus there’s just so damned many of us. ”Who do you belong to?” was a common question I got growing up. I ask it at family reunions now. The stories help keep us sorted out.

I’m sure Aunt Margie had a bunch of stories that she told about herself, embarrassing stories. That was just the way she was. She liked to laugh. But here’s my story for her, one part of what I want to bring with me:

We’d just moved from the farm out to Flandreau. Because her clan lived out in Madison, I hadn’t really gotten to know her before then. I was in tenth grade and at a complete loss for pretty much everything. Except for one thing. And I know that this is going to be both offensive to the family and something that makes them nod because it’s true. I was relieved to be out of the gossip.

I wasn’t the center of gossip, thank God. No, it was just that the farm itself was the center of gossip, the geographical ground zero of the Knippling clan and all its drama. There was always some low-level feud going on between wives. Some argument between brothers. Someone calling someone else a fool behind their backs.

A couple of hundred miles away, it was restful. Peaceful.

I tried to tell this to Margie one day. I had to tell someone, and my parents weren’t the ones to talk to. They were going through a lot, good and bad, having left the farm. And one day we were over at her house for some reason or another, and it just came out. Horribly, awkwardly.

I’m prettty sure I insulted the people she loved best. She forgave me. She said, “You don’t get to pick your family. You don’t have to like them. You just have to love them.”

It’s true, and it helped. I learned to roll eyes with the best of them. And what she didn’t say, but what I have also taken with me, is that they just have to love me. Whenever I made a choice I knew that would have the gossips all a-flutter, I thought about her words, and went on with what I felt called to do.

She wasn’t a saint, or at least she wouldn’t let anyone call her one. But everyone who knew her knows that she is one of the pillars of everything solid and merciful in our lives, no matter how much or little she touched them.

For example, I’ve talked to other people who were so filled with despair that they say things like the world is awful and people are crap and why bother. Well, but then there’s my Aunt Margie, see? I always knew those people were wrong. It’s not the world itself that’s wrong, because if that were the case, then Aunt Margie would have been wrong. And she wasn’t. I just can’t plumb the depths of despair because of her and people like her. I already know better.

This causes me to get extremely irritable at times; I just want to shake people for being such idiots when it’s just not necessary. And so I know I can’t be her. I’m just not that patient. And I’m not that forgiving. But I’ll try.

Because I like her. Very much.

October 9, 2013

Horror vs. Ghost Stories

I love old ghost stories. Mostly late 19th-century British ones. There are some good American ones, Canadian ones…but mostly British ones. They’re short, maybe five thousand words at most, and are not inhabited by ghosts so much as they are by something else. Yeah, there are ghosts, but not even half the time. There are ghosts of servants that terrify their masters…people possessed by tiger gods…cancer embodied as crabs…vampires that go about in daylight and invite one to tea.

You could call them ghosts, as a kind of general catchall, but they’re something else. You have to wonder if, at the time, the British were acutely aware of the Empire falling apart, of history being redefined by other people who weren’t British. Of things being not what they seemed.

But – I’m getting ahead of myself. I’ve always wanted to write a good, turn-of-the-centuryish ghost story, but the’ve always seemed to escape me. I think it’s because I didn’t really understand them.

A couple of weeks ago, at a new thrift store (DAV), I found a curious book. It’s called The Haunted Looking Glass: Ghost Stories Chosen by Edward Gorey. It’s just what it sounds like, twelve ghost stories with Edward Gorey illustrations. Algernon Blackwood, Robert Louis Stevenson, Wilkie Collins, and yes, Bram Stoker. Most of them I haven’t read before. ”The Monkey’s Paw” I think is the only one, but I haven’t finished the collection yet.

I had just about finished “The Body-Snatcher” by Stevenson last night when I went to bed, which might imply that it wasn’t that interesting a story, but I was very tired, so I stuck in the bookmark and went to bed.

I woke up about two, dreaming of redlines (editing marks) that had ripped themselves off the page and were bleeding freely. It’s been that kind of week. They were after me, trying to tell me to do something horrible. Some serial killers hear gods, angels, demons–I hear redlines muttering madness to me in my sleep. At any rate, I woke up, tossed and turned for a bit, then got up and wrote a few pages in my journal, because I couldn’t go back to sleep for worrying. About money, mostly, but also about feeling like I had grown pettier and meaner recently. More likely to snarl than laugh.

I wrote. As I wrote, not before, I realized that the dream with the redlines had been a nightmare so bad that it had woken me up, and that I had kept myself from going back to sleep because I didn’t want to chance slipping back into it. Simultaneously, I figured out why I was feeling so negative; when I feel like I’m not contributing, I get angry at other people that I feel aren’t contributing, or that…well, someday I’ll write it in a story. That’s what I do when I find out something so awful that I don’t want to actually confess it about myself, but I need to get it out in the open, more or less. A story has the benefit of being fictionalized, so you can both distort the truth and let a decent amount of time pass before you have to talk about it with anyone, so you have time to heal over the wounds to your ego. At any rate, it wasn’t pretty.

Then, feeling tired but not quite willing to go back to sleep, I read the end of the Stevenson story.

It was abrupt, so abrupt that it felt lame. Maybe it was just…the time it was written…eh. Whatever.

I went to bed and had a hard time falling asleep, because my head was full of good ideas. Fortunately I did fall asleep, and I did remember the one idea that was really good. I worked on it some more this morning already. I keep going, “Oh, this is good.” It was such a relief to have the weight of all that negativity off my shoulders that my mind was full of more good things than it knew what to do with.

When I woke up again, I reread the end of the Stevenson story. Yes, still curiously lame.

But then I flipped back to the beginning.

There was the end of the story. You had to read the story like this: Beginning–>End–>Beginning. If you didn’t read the beginning again, well, you might have been able to hold the entire story in your head and mentally reread the beginning. At any rate, the beginning, after I read the end, had changed.

Aside from everything else, this got me thinking about ghost stories. Not horror. But ghost stories.

Horror is about pain, and whether you give in to pain, resist it, recover from it…pain. When you look at Edgar Allen Poe, you’re looking at horror. You don’t go back to the beginning of an Edgar Allen Poe story and find that it has changed under you. Sure, “The Purloined Letter” was there all along, but in Poe’s version of ghost stories, it’s all about madness and torture and shock, not about redefinition.

The primary element of a ghost story is haunting. And what we are haunted by is not ghosts, not things that go bump in the dark, but by our assumptions about ourselves, which are so much stronger than the facts that we observe about the world…but the world will insist on its not being entirely erased by our notions.

If we could see ourselves clearly, we would not be haunted.

Free Fiction Wednesday: The Secret of the Cellar

Not much has changed here – the layout and fonts are all. Okay, that sounds like a lot. But really it wasn’t.

Under the basement…down in the dark…

Elly always gets stuck with entertaining her relatives while their parents talk to her mom. Blah, blah, blah. It goes on for hours. But this time, she worked and worked to make a special surprise for her visiting cousins…a haunted house in the basement! With a super-duper, extra-gross surprise in the spooky cellar.

It should be the most fun that they’ve had in forever…until things start to go mysteriously wrong…

“The Secret of the Cellar” will be free here for one week only, but you can also buy a copy at B&N, Amazon, Smashwords, Apple, Kobo, Powell’s and more.

—

The Secret of the Cellar

When the cousins came over to Elly’s tiny yellow house in Michigan, which was shoved in between two other houses so they almost touched and had barely any yard in the front or the back and no parks to go to, her mom would say, “Elly! Take your cousins downstairs and entertain them while we talk,” and she would. Sometimes they would play “stay off the lava” by jumping between the old, stinky, ripped up couches, and sometimes they would play “planet destroyer” by using the white pool ball to knock all the other balls off the pool table, which usually ended up with someone having pinched fingers and them all getting in trouble for making too much noise, and sometimes they would play “hide and seek.” One time Elly followed her cousin Jackson to the downstairs closet under the stairs and locked the door so he couldn’t get out. Then she found all the other cousins and they went upstairs and played tea with snickerdoodles and dolls until it was time for them to go. Jackson was so proud of not being found that he never noticed that he got locked in, because she unlocked the door before she yelled for him to go home.

This time it wasn’t Jackson but the M cousins from Iowa. There were four girl cousins, and their names all started with M: Missy, Mandy, Mary, and Maureen, which Elly thought must be kind of embarrassing at school.

“Just let us know if you need anything, girls!” said Aunt Jane.

“Okay!” Elly said. She led them away from the living room with all the adults to the door to the basement. She had her lucky purple dinosaur shirt on, and her lucky red sneakers, and her jeans with butterflies on the back pocket, for good luck.

“Can we play pretend?” asked Mandy. “I want to be Esmeralda the Elf Queen again.”

“No,” said Elly. They were always wanting to play the same game over and over again, and she wasn’t going to let them. “Today we are going into the basement.”

“We always go into the basement,” said Maureen. She was the smallest. And the whiniest.

Elly had a very small red metal flashlight in her pants pocket, attached to a keychain holder. Now she turned it on by turning the cap in a circle and held it under her face. “Yeah, but then we are going into the cellar.”

Missy said, “I don’t want to go into the cellar.” She was the oldest. And the bossiest.

“Then don’t,” said Elly.

Missy opened her mouth. Missy had just turned thirteen and was getting about as annoying as the adults.

Elly had been practicing really hard to find out if she could control people’s minds, like an evil telepathic genius or something. She stared at Missy’s mouth, trying to make her say, “Okay…I’ll go hang out with the adults then…”

But of course Missy didn’t do what Elly wanted her to do.

“No,” said Missy. “I’m going. You’re going to do something crazy that goes completely and ridiculously wrong. I can tell.”

Elly rolled her eyes.

She could roll her eyes all the way up into her head. She had to be careful about it, because it made her dizzy. She held the flashlight out a little, and Maureen went urrreeeeeee! which was a stupid sound but made Elly happy that she’d freaked Maureen out anyway.

Elly said, “Follow me if you dare,” then laughed dramatically.

“Whatever,” Missy said, and jerked the door open.

All the lights were off.

Elly shone the light down the stairs. The metal treads at the ends of each stair shone dully back at them. The door at the bottom of the stairs was wide open, and the tilted mirror at the other end of the downstairs guest bedroom reflected Elly’s floating face back at them.

Maureen made another gulping, squeaking sound.

“You aren’t too chicken, are you?” Elly asked.

“No,” Missy said. “But if you keep messing around I’m going to tell on you.”

Elly laughed again. She wasn’t trying laugh dramatically, but it sounded pretty nasty anyway. She wondered if she could learn how to make that laugh on purpose, but now wasn’t the time to practice. “You’re a teenager now. If you tell your mom will just say, ‘Now, Missy. You know that you’re the eldest, and you’re supposed to be in charge.’”

Missy said, “I don’t care. I will anyway.”

Elly ignored her and started walking down the stairs. Ignoring Missy was about the only way to deal with her anyway. As they went down the stairs, Elly said, “Once upon a time there was a little kid who went to a haunted house. Her name was—”

“Her name was Missy,” Mary said.

Elly frowned, because she knew that when she smiled her voice didn’t sound as spooky. She knew that because her mom was always making her laugh when she was trying to be spooky. But that was okay, Mom was good practice. Because if you could spook out Mom, you could spook out anybody, and Mom said she was getting pretty close.

“Okay, her name was Missy and she was almost a teenager,” Elly said.

“I am a teenager,” Miss said.

“This story isn’t about you, it’s about someone else named Missy.”

It was really, really dark. It was already night outside and plus Elly had closed all the basement curtains, which were short and tan with red yarn stitching for decoration and had plastic on the backs to keep out the sun, so it was really dark.

“Who else do you know that’s named Missy?”

“Lots of people,” Elly said, annoyed, “except they’re all dead.”

“They are not. You don’t know any dead people.”

Elly really wished she could just put a piece of silver tape over Missy’s mouth. Because Missy was going to spoil everything. “She had gone visiting at her cousin’s house, and the cousin’s mom told her about a—”

“Her aunt,” Missy said. “Your cousin’s mom is called your aunt. Are you stupid?”

Elly stopped at the bottom of the stairs and held the flashlight under her chin. She about felt ready to cry or scream or throw a tantrum. This was not going the way it was supposed to be going.

“If you don’t shut up, then I’m not going to tell the story.”

Missy breathed in, and Elly quickly interrupted: “I mean, if you don’t want to hear the story, then go away.”

Nobody said anything for a minute, and then Maureen said in a teeny tiny voice with really fast words that kind of ran together, “Um I want to hear the story but you shouldn’t say shut up.”

Elly snorted. “I can say shut up if I want to.”

“But you might hurt someone’s feelings.”

“Missy already hurt my feelings. So I don’t really care if I hurt hers back.”

“Oh.”

Elly stared at Missy and Missy stared back.

Mary said, “Something smells bad down here.”

Elly took a deep breath. She pretended to smell whatever Mary smelled, but she was really just trying to keep from crying. But anyway she couldn’t smell anything.

“Fine,” Missy said.

Elly turned toward the big room, which was the room with all the stinky, broken couches and the pool table and the ancient, torn dress-up clothes that felt like sticky sandpaper because they hadn’t been washed for so long and the door to the cellar.

“Her cousin’s mom told her a story about a ghost, and it creeped her out so much that she couldn’t sleep all night. The next day, Missy went to a haunted house with her friends from school. They were going through the haunted house together when suddenly they realized that they were being followed by a ghost.”

She dragged her shoe on the gray yarn she’d left on the floor, in exactly the right spot. It was her secret trigger.

On the other side of the room something went clickaclickaclicka.

It was just an old red metal windup clown car and she had to practiced about twenty times to get it all to go right, but her cousins didn’t need to know that.

Maureen went urrrr—and then there was a slap as Mary put her hand over Maureen’s mouth, and then Maureen screamed into Mary’s hand.

Elly kept walking. Now she was in her spookiest mood. “Everybody screamed and ran, and the next thing that Missy knew, she was lost…in the middle of a room full of spider webs.”

A tiny thread brushed her face. She gave it a soft pull.

The ripped-up sheets didn’t come down and brush on everyone’s faces like they were supposed to. So she pulled harder.

The thread broke.

She said a bad word, and she said it just a little too loud.

“You shouldn’t say that,” Maureen said. “It might hurt—”

Elly said the word again, but quieter. “Never mind. Let me finish the story.”

Missy sighed loudly.

Quickly, Elly started telling the story again before Missy could start talking. “And then she went into a room where the ghost appeared in front of her and said, ‘You can’t go into this room…there are gushy, yucky, squishy things in this room. My body is in this room.’ It was the ghost of a little kid…who looked just…like…Missy.”

She stopped at the right spot on the floor, trying not to move her foot too much or she’d give the whole thing away, and pushed the power button on the remote with the toe of her shoe.

The TV turned on and the movie started playing.

It was a movie of Elly, dressed up as a ghost.

The movie Elly said, “Dooon’t gooo in the cellerrr.” Mom had helped her edit the movie so it really did look like Elly was a ghost. She was see-through and wavy, and she was surrounded by mist.

Mary burst out laughing. “This is about the stupidest thing I’ve ever seen.”

But her voice was kind of high and squeaky, and really fast.

Maureen, however, was so scared she couldn’t even go urreeeep.

The movie turned into black and white specs of static, which Mom thought would be creepy. Elly didn’t but whatever, it made Mom happy.

Elly was about to start on the final trick, which was behind the cellar door, when Missy said, “Really? Come on, Elly, really? How stupid can you get?”

Elly pushed her teeth together over her lips and smooshed them back and forth. Her chest hurt so bad. She felt like Missy had just beat her up. Didn’t she know how hard she worked on this? Didn’t she know how bad that she wished someone would make a haunted house for her?

And nobody ever, ever would.

“Don’t say stupid,” Maureen peeped. “That word hurts people’s feelings.”

Elly couldn’t breathe right. It felt like she was all smashed up, like a fancy china doll that had been thrown against the wall and jumped on and smashed up into little pieces.

“Fine!” she shouted.

And she walked over to the cellar door and yanked on the door.

But it wouldn’t move.

She dropped the flashlight on the floor, and took both hands, and pulled on the door.

It still wouldn’t move.

“Help me,” she said. A horrible, loud sound was ringing in her ears. It was a sound coming from the inside of her own head, the sound that she always heard in her head before she started crying with a broken heart.

Mary stood next to her and put her hands over Elly’s hands and helped pull.

And then Maureen grabbed the back of Mary’s jeans and helped pull.

But the door still wouldn’t come open.

“Please, Missy,” Elly said. Her voice sounded far, far away, and the sound in her head sounded closer and closer. She didn’t have long before she had to throw herself on one of the stinky couches and cry until she fell asleep or everyone went away. “Please help us.”

“Pleeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeease,” said Maureen, saying it for a long time until she ran out of breath, and then she breathed in loud and said it some more. She could do that for a very long time.

“If you don’t I’ll tell Brady about your dolls,” Mary said.

Missy grabbed onto Mary’s arms and yanked hard, just to be mean.

But the door opened with a loud grawaaaaaaaahonk! as it scraped over the basement floor.

They all let go of the door at the same time and skipped backwards, all bonking into each other and trying not to fall, Elly especially because she would have squashed Maureen.

“Ugh,” said Mary.

Maureen said, “That smells bad.”

Missy said, “Wow. Just…wow, Elly. What did you do, put a bucket full of dog poop down there?”

Whatever they were smelling, Elly couldn’t smell it.

She and her mom had put a bucket of squishy guts made out of noodles and jello and peeled grapes and hamburger, for the end of the ghost story.

“Make sure you hold everyone’s hands as they go down the steps,” Mom had said. “Those are some pretty steep, sharp, hard cement steps. Only one person at a time and hold the railing.”

Missy said, “I’m not going down there.”

Mary said, “I’m going to puke. Elly, I have to go into the bathroom and puke so turn on the light right now.”

Maureen started crying, a sad cry that made Elly’s angry, disappointed tears stop, because she sounded so sad.

The story was over, the haunted house was done.

“Okay, okay,” she said. She reached over to the switch beside the cellar door and turned it on.

The cellar lit up.

There were wood shelves with glass jars full of applesauce and tomato sauce and cut-up cooked chicken in parts.

And a hole in the floor with a black pump to take water out of the cellar when it flooded.

And a bucket with gushy fake guts in it, for the haunted house.

And sharp, sharp, tiny cement stairs.

And a girl with blonde hair and a pale, pale face and a purple dinosaur t-shirt and butterfly jeans and lucky red sneakers and a lot of blood missing, well, not missing, because you could see it right there, running down the stairs, across the floor, and into the square black hole for the pump, and her head smashed open so you could see all the brains inside.

It was Elly’s own body.

Three voices screamed.

Elly stared at her hands…they were disappearing. And she couldn’t make any sound at all.

THE END.

October 2, 2013

Indie Publishing: Check your page count!

I think I’m going to just have to add walking (most) clients through their royalty calculators to my interior print layout services.

Because what happens is I ask them, “How many pages do you want the interior to be, approximately?” and they say, “Oh, whatever looks good.”

This is a bad, bad idea.

Okay. Let’s take this as an example. You have a 120,000-word book. (Here’s where the experienced people flinch, because they already know there are some painful choices to be made.) You decide you want a 12-point font, because it’s important that your text be readable. You tell your designer, “It’s important that my text be readable.”

Your designer, quite correctly, goes for a 12-point font (or something reasonable, which will depend on the font itself), multiplies that number by, oh, 1.5, and comes up with a good amound of space for the leading, that is, the space between the lines of text. Single space is 1x the text size (so your text is 12-point text and your leading is 12-point spacing between lines). Double space is 2x the text size (12-point text, 24-point leading). Leading at 1.5 is a good starting place for this kind of thing–but the designer should be willing to change this, based on client input. Designers, until they do all the interior formatting fiddly bits (and you should be approving the design before they start on those), are not married to a strict 1.5x font leading.

By following those guidelines, your designer could hand you off a book that’s over 450 pages in length, at a 6×9″ layout.

As a rule of thumb, you want to make about $2 each on lowest tier of royalties from your distributor. Because we’re talking indie POD stuff here, your basic options are CreateSpace, Lightning Source International (LSI), and Lulu. If I have time I’ll double back and look up the info for LSI and Lulu, but here’s the CreateSpace royalty calculator, which is what most of you are going to start out with.

Go take a look at it and plug in the numbers: b/w interior, trim size 6×9″, number of pages 450. You have to enter a cover price. Let’s enter, oh, $9.99.

Those of you who know where I’m going with this, yes, you can snigger.

Enter the price and hit Calculate.

What you will see is that the Amazon royalty is -$.26, the eStore royalty is $1.74, and the expanded distribution (all other places other than Amazon or directly through CreateSpace) is -$2.26. The number is also a negative in the pounds and euros fields.

Your good intentions plus the designer’s good intentions equals YOU WILL LOSE MONEY ON THIS BOOK.

Generally, you want to shoot for a profit of about $2 per book. This means a) you make some money, and b) the BOOK SELLERS MAKE ENOUGH MONEY TO MAKE IT WORTH CARRYING YOUR BOOK. The book sellers make a percentage of your cover price–usually around 40-50%. If the book is priced too low, they won’t stock it. Pfft. They’re not selling books to be noble. So don’t undercut your royalty by more than like 50 cents, or the booksellers won’t want it, either.

In order for this 450-page book to make $2, you have to price it between $19.99 and $20.99, which makes it a tough sell to readers, even in trade paperback size (6×9″).

URK.

Okay. Let’s say you looked at those numbers and went back to your interior designer (before you finalized the design, mind you, because if you approved the design and let your designer do all the fiddly bits, you deserve to pay for the additional hours of formatting work over and above your original agreement) and said, “Look, 450 pages is too many. Can you get me down to…350?”

As you can see if you go to the royalty calculator, if you can get the book down to 350 pages, then you can charge $16.99 for the book, which is slightly more reasonable (for a trade paperback).

Your designer should be able to do this. They should be able to give you options for cutting over 20% of your page lengths, if they’re starting from a reasonably ideal text layout. Now, if they start out by saying, “I know this is a long book and you’re going to want to save some pages, so I’ve condensed the layout a little,” then they may not be able to make another big cut to the pages. I’m just saying that in most cases, there’s a lot of wiggle room. They may have a hard time hitting an exact page count, but if you give them a range of 25 pages or so, they should be able to hit it.

However, this 120,000-word book will never be anything but a 120,000-word book, and when the text comes back, it will be much closer to single-spaced than it will be to a 1.5 leading, as I discussed above. The margins may be smaller; blank pages may be removed; you may end up with less open space on your chapter pages. In extreme cases, you may end up with just a chapter marker, with no separate chapter page at all. You will still end up with a book that you have to charge more money for. Because it’s a 120,000-word book.

As the publisher (dear indie publisher), it’s your responsibility to think about these things. Don’t just say, “I trust you,” even if you have a good designer. They may do a great job with the layout. You could have the prettiest interior ever. But if the page count might kill your sales, then ask your designer for help–ASAP.

September 30, 2013

Free Fiction Monday: The Whispering Tree

Strong language and adult situations, for those of you who find such thing appealing. I was thinking…I particularly like those stylized black and white covers. Here’s a version that fits my short story template.

A writer torn between two genres, two worlds…and Horror always cheats.

If only the best writer of his generation, Richard O’Shea, had come down clearly on one side or the other between the horror and fantasy genres, none of this would have happened. But he didn’t, and now both worlds play dirty to get his soul. The fairy lands send their queen: a lusty, foul-mouthed punk with glitter and sex in her eyes. Hell sends something darker.

The two worlds won’t share him. They’re getting old, and need fresh meat, as it were, to revitalize their realms. Richard wants to believe that the punk charms of Fairy have won him over…but Hell doesn’t need Richard to like it in order to win.

Now the only thing between Richard and Hell’s dark charms is Victoria, his editor. An editor who carries both pens and swords…and has very sharp teeth…

“The Whispering Tree” will be free here for one week only, but you can also buy a copy at B&N, Amazon, Smashwords, Apple, Kobo, Powell’s and more.

—

The Whispering Tree

The love of my life had just told me that the reason she’d been holding herself back was that she wasn’t human, but a Fairy. A real one. And that, if I had went to Fairy with her, according to the rules of fantasy, we would be setting inevitable machines of tragedy in motion that would work to keep us apart forever after.

I’d just told her that I intended to find a way around the rules. It was what I did, after all. Not break rules so much as just…weasel around them.

“But the rules—”

“When you have the rules figured out, it’s time to change the rules,” I said, more bravely than I felt.

She put her hands on the small, round table…and headbutted me. Oh, I don’t think it was intentional; in her next movement, she grabbed both sides of my head and kissed me. “Then run away with me,” she said. “To Fairy. And we will change everything.”

I saw stars and the inside of my skull felt as though it had a nosebleed. “Didn’t you just tell me that if I loved you we’d have to live here forever—”

She kissed my forehead tenderly in apology. “Fuck living here. It’s dull.”

I didn’t dare move lest I pass out. “What about Victoria?”

Celia had just finished telling me that Victoria, my wife and editor, wasn’t human, either, but a member of Celia’s court—the fairy court. It was hard to believe Victoria a fairy, with her blunt, steel-gray hair and little purse lines around her lips. Easier to believe it of Celia.

“Fu—” Celia burst into the loudest, coarsest, manliest type of laughter. “No. Not her. Me. Fuck me.” She kissed me again.

I discovered, after half a year of anticipation (and now that the excruciating headache that she’d given me had faded somewhat) that I rather liked it.

Celia pulled out a hand-rolled cigarette (when I’d met her, she’d claimed she had virgins roll them for her and lick the papers shut with their hungry mouths; it was a little more believable, now) and lit it. She blew smoke to my left, then offered me a drag, her lips doing that thing where they sparkle in the light like they’re covered with glass. “They can’t possibly find you that quickly. We’ll go in and get out before they know about it.”

“They.” I took a drag on it. It was good enough that it reminded me of the first cigarette I’d ever had, or the first time I’d fallen in love, before I’d fucked everything up.

“The legions of Hell. You can’t think that Fairy is the only land that wants you. Yes, you have a gift for fantasy. But…” She let her eyes linger on me, making me feel like quite the bad boy for once in my life. “You have a gift for horror, too.”

“Um,” I said. It was one thing to know that the personification of your favorite genre wanted you; quite another to know that the genre you tried to avoid but that kept creeping back into your stories would be after you, too.

“It’s us versus them, baby. They want you at least as bad as I do.”

I raised an eyebrow at her. “For…”

She cackled. “Oh, yes. But they certainly won’t make you eggs and toast the next morning.”

“Is there breakfast in Fairy? And if I eat it, will I have to stay there forever?”

“Most do,” she said. “I make a mean french toast. But fuck it. Let’s go.” She stood up from the table. She was tall; in her impossible shoes she was taller than I. Her eyes glinted at me through a curtain of black lashes.

I made one last effort at resistance, knowing that it was meant to serve the same purpose as a negligee on a bride. “But what about Victoria?”

Celia’s smile widened. “She doesn’t go for romance…adventure…sex. Except in books. As I’m sure you’ve noticed.”

—

I knew it the moment they decided to cross into Fairy, the moment he kissed her. A hole was punched into my heart, letting all the blood drain away until I was cold as ice.

I looked at my hands on the keyboard. They had turned from a repulsive light-peach color to a flat gray. I grinned helplessly, feeling my teeth sharpen into dogs’ teeth. As expected, O’Shea had decided to break his promise to me to stay on this side of mortality until he’d committed to a genre. I had two proposals on my desk: one horror, one fantasy. Both, to be honest, sucked—his heart wasn’t in either of them. He wanted to write both.

Men.

His career was in the balance, and Celia was trying to sway things her way: Come with me to Fairy and I’ll have sex with you… As though Hell would let him go without a fight.

Someone gasped. My armor and armaments were coming back to me as I lost my mortality, and my secretary, Mikaela, was getting an eyeful of a gray, sharp-toothed knight coming out of her boss’s office.

My buckles jingled. I strode across the room.

The security guard stood next to the elevator door. “Ma’am?”

“I am going out, Charles,” I said, lowering my visor.

He pushed the elevator button for me.

I called over my shoulder. “Mikaela? Hold my calls.”

She had followed me and was standing behind me on her tiptoes. “Victoria? What’s going on?”

“Family emergency,” I said. I reached out with my gauntleted hand and held her quivering chin gently. “Fear not. I shall not abandon my list. I shall return soon to ensure your book is published.”

The League of Viciously Spiteful Cows, mid-list at best, although I had enjoyed it immensely. It might take off at the chain stores, I thought, if we could get it in the book clubs. She wasn’t a talent like O’Shea, just a normal girl with a good sense of humor. It would be a relief to work with her.

Mikaela nodded tearfully, confusion fighting with loyalty in her eyes.

The elevator dinged and the door opened. I stepped aside to let the mail cart pass, then joined two smirking men in suits on their way to the ground floor. I did not kill them.

O’Shea was in deadly danger, and I had sworn to protect him.

—

I followed Celia out of the café. She stepped into the street and was nearly hit by a conveniently-empty cab that screeched to a stop an inch from her hip. The driver’s hands were shaking as we slid into the seat behind him and he moved forward with traffic.

“That was just the damnedest thing—”

“To Fairy,” Celia interrupted him.

“Yeah,” he said. “Yeah. I know where that is. Yeah.” After another half-block, he said, “Wait, what?”

Celia rolled her eyes. “It’s a nightclub on Eighth and Fifty-third? The Pickled Fairy? Lots of fags?”

“Oh. Yeah,” the driver said, and we were on our way.

I spent the rest of the drive with her twined between my legs. We kissed. She fondled me through my trousers. I rolled my tongue over her half-covered breasts in what must have been full view of the driver, and didn’t care.

Eventually, we reached The Pickled Fairy. Celia waved at the driver, and he said, obviously against his will, “Never mind the fare. Sorry about almost killing you back there.”

“Don’t worry about it,” I said, and we skipped off.

It was midmorning, and the air was still cold enough to curl the hair in my nose. The front of the place was covered with abstract purple and green shapes that reminded me of Mardi Gras masks—but with insect eyes staring from the holes. Celia walked up to the front door; it was locked. She glanced up and down the street—it wasn’t exactly abandoned—took off her pump, which looked like a steel-tipped prostitute’s shoe or something Bowie used to wear, and used it to smash in the glass. She had to pound at it a few times to push the wire mesh apart, but nobody seemed to notice.

She reached in, fiddled around a bit, and opened the door out toward us. I followed her in. Well, it was her club. We went through the entryway, where the old theater had sold popcorn and Celia’s fairies now sold condoms and feather boas and wine out of boxes, and into the club itself.

Only a few of the lights were on. Most of the theater seating had been removed, the floor was covered with some kind of tile that looked gray but shimmered with color as I walked on it. Glass booths had been built into the walls on platforms, with gauzy curtains covering the inside—for concealment or enhancement, I had never been sure which.

She put her hands on her hips and pursed her lips. Her hair was a tousled mess strung with Christmas tinsel. She was wearing a teal corset and a miniskirt made out of what looked like feathers but felt like satin. I stroked her ass. She bent over at the waist and grabbed her shoes at the ankle.

After a few moments, she stopped me. “Not here. Over there.” She pointed at the old stage, hung with swings and cages.

“Er,” I said, suddenly uncomfortable. Her sense of balance was legendary among her customers, who always caught her in time; mine usually involved looking British and apologizing profusely.

She grinned with perfectly-formed teeth. “What, swings too kinky? No. We’re going to Fairy.” She led me up the ramp to the stage, swinging her hips as she walked on her impossibly stacked shoes. “I don’t just want to fuck you,” she said. “I want to fuck with your head. I want to show you what you’ve been imagining all your life. I want to—“

She screamed.

—

My horse, Lord William Falcon, was waiting on the sidewalk, snorting hot steam from his nostrils. He stamped a hoof as I pushed through the revolving door in the lobby, scratching the glass with my gauntlets. I whistled, and he charged gleefully though the crowd, pushing passersby aside with his enormous chest.

I swung up in the saddle, checked the seating of my sword, Holiday, to make sure it wouldn’t catch in a strap, and patted Falcon on the neck. “Ho, noble steed.”

“Welcome back, mistress,” he said. “To Hell and back.”

“To Hell and back,” I confirmed. “We defend O’Shea from demons this day.”

“As you predicted,” Falcon noted. “Celia cannot resist her mortals, can she?”

“Indeed not. I had hoped for a peaceful changeover, but—not with this Queen.”

“Peace is for the mortal realm, mistress. It has no place in fairy.”

I sighed. I complained about the ways of mortal writers…but for the life of me, I loved their comma mishaps so. Falcon was right.

We galloped down the street, leaping over shrieking pedestrians and food carts redolent of garlic and tongue, wheeling to a halt in front of the Pickled Fairy, my Queen’s nightclub.

I slid to the ground, then spat on the sidewalk. “Phaugh!” I hated the place, but it was the nearest place to Fairy in the mortal realm. I remembered when it had been as used bookstore, as was right and proper.

I drew Holiday and slashed through the front door, then charged past the glitter and sparkle. Richard O’Shea was standing just on this side of mortality with his mouth open and his eyes fixed on Celia.

Celia was impaled on the spikes of a demon, who casually ripped off her beglittered arm and gnawed on it. Celia gasped, “Save Richard! Hell shall not have him!”

“My Queen,” I said. I grabbed Richard, threw him over my shoulder, and ran back with him to the sidewalk.

In the daylight, he finally regained the power of speech and the illusion of bravery. “Put me down!” he shouted. I tossed him across Lord Falcon’s back. “Take him to safety,” I said, slapping Falcon on the flank. Falcon, ever melodramatic, reared (while not allowing O’Shea to budge an inch on his back—magic) and galloped away.

I ran back into the club. Demons were swarming from behind the curtain at the back of the stage; Celia had disappeared. I hacked them down as they poured toward me.

Aside from redlining, I live for days like this.

—

Snatches of conversation rang in my ears as the horse galloped willy-nilly with me through Manhattan.

“Girls with jobs. Girls with money—”

“A three million investment will get you—”

“I’m so used to Laurel taking minutes—”

The conversations usually ended with some kind of exclamation as the stallion charged into them.

I was unable to move from the back of the horse, even to lift my head; it was as though I had been glued there. The sound of his hooves echoed through my skull.

“Let me down!” I shouted. My words came out somewhat garbled, as part of my face was stuck to the skin on the back of his neck.

“Be patient, my Lord,” the horse said.

“Where are we going?”

“A place of safety. Back to the editorial offices, where you can make a reasoned decision between genres, as My Lady Victoria requested.”

“At least let me sit up.”

The horse chuckled. “Nay, my Lord.”

Another conversation: “In a spiritual context—”

“Help me!” I screamed. But we passed the voices in a split-second.

The sound of the horse’s hooves changed from the ring of steel on pavement to dull clomping. The horse slowed and stopped. His skin twitched under me, as if I were a particularly pesky fly. He danced in place, whickering nervously and turning in place. He froze and almost stumbled, then whinnied in fear.

I caught a glimpse of something green and hideous as he wheeled, full of spikes and sharp edges. It looked unlike and yet like the thing that had attacked Celia. I whimpered. The horse’s muscles gathered under me, and it leapt forward. I almost fell, even though I was glued to his back.

“But dude, like, the homes are really old, like thirty years old. Holy shhhhiiiiiiii—”

Something hooked into my back, and I screamed as I flew off the horse’s back…

—

I chopped, and I chopped, and I chopped my way forward through demon flesh until I reached the curtain that, at my Queen’s will, would open the way to Fairy, but had been hijacked by the guards of Hell.

A massive quartskuller was guarding the way. I attacked with an overhand cut. The quartskuller’s treelike, wooden arms jerked forward and grabbed me around my torso.

When fighting a quartskuller, always attack with an overhead swing; it’s the only way to keep your sword free for fighting, because they will grab you. The demon slowly began to crush me to death. My breastplate, forged out of a warding sprite being punished for insulting the queen at a party, resisted the pressure as best it could.

I brought Holiday’s spiked pommel down smartly on the quartskuller’s head and twisted the quillons. Luckily, I hit the soft spot on the first try, and the demon’s brain fluid welled up around the spike. I jerked Holiday free, and the demon’s head deflated with a spurt.

This in no way should be taken to imply that it released me. However, now I was able to chop its arms away from its chest without it being able to think of any way to stop me. Eventually I freed myself.

Despite what other knights may say, the only real danger in fighting a quartskuller is in the inevitable delay in removing at least one of its arms. One really must clear all minor enemies from the area before engaging. With enough time, even the most mindless demonling can find a gap in one’s armor into which to insert its razor-sharp tongue.

I charged through the portal.

—

I awoke in Hell. I will not describe the tortures I experienced, witnessed, and became there; suffice it to say that I have been assured that in no way could I have prevented what occurred.

Especially the parts of it I enjoyed. Hell has its temptations.

—

I do not care for Hell-spawn, but they serve a higher purpose than anything in Fairy. Hell is the skin of the world, its first barrier against the Outer Dark. Some in the Fairy realms laugh nervously when the subject arises, and defend their prejudices against the Hell-folk by saying the demons have spent too much time on the edge of the world and have started to become the formless monsters against which they defend, which is so much manure; I have told them so.

What is a demon but a kind of monster?

What is a monster but a twisted reflection?

What is the purpose of a reflection but to cause us to reflect, to become self-conscious?

The demons of Hell are twisted, but they are twisted in our service, so that we might be ashamed of ourselves if we should happen to recognize ourselves in them. Also, they are (for the most part) formidable warriors, able to transcend matter and spirit and attack the Outer Ones directly. It is true that battle changes them, but not for the worse. I salute them, when they do not abduct my husband and Queen for their own foul purposes.

When I stepped into Hell, which could have been an instant later or an eon, time being what it is in the mythical realms, a gaggle of demonlings called lebensmen had hold of O’Shea and Celia in an antechamber of Hell. Apparently, O’Shea hadn’t made his choice yet, for which I was grateful.

The antechamber appeared to be a bureaucratic office of some sort, filled with the waiting dead in grisly condition. These were the ones who, in life, had glanced up at atrocity and returned their gazes to their magazines and their cell phones; in death, they would be called out of one waiting room and escorted into another—until they chose to see and to act, which of course they would not. Personally, I would rather have been damned from something from which redemption might be gleaned, like mass murder or working as a street mime.

Celia had died but recently; O’Shea was standing over her, bending her backwards over a coffee table covered with dental magazines, holding the knife quivering in her breast with a loathsome look on his face, with thin red tendrils leading away from his ankles. The master lebensman, lounging in all its lobster-red, sluglike glory, was lecturing its juniors on the proper way to wrap a victim, so that it neither could escape nor know that it had been wrapped and made to dance. The master had, in a fit of delicate insight, taken possession of O’Shea rather than Celia. The master was letting him howl and struggle against the control, making him think himself a coward for both attacking Celia and being unable to ameliorate the attack by stabbing himself.

Celia had died knowing what had been done to her. She had a frustrated scowl on her face and clearly was glaring at the master, who stood a good deal of distance away from Richard. The younglings had withdrawn from her, leaving bloody trails between her body and their master.

“Unhand him,” I yelled, drawing Holiday. With two swipes of the sword, I cut down three of the juniors and a handful of do-nothings on a nearby bench, leaving only two juniors left. “Withdraw!”

The two juniors squealed and slithered away in fright, moving no faster than a crippled snail. The master looked up absentmindedly, adjusted his spectacular on its frame over his head, and said, “Oh, pardon. I hadn’t realized you were in such a hurry. One moment.”

It took what seemed like hours, but there was no rushing him, or it would have left irreparable damage. Meanwhile, I carefully, lovingly (but not gently) cut Celia into pieces, cleaned her as best I could with glossy magazine paper from one of the damned, and stuffed her into a large mail bag, which I tossed on the ground next to Richard. While he writhed in pain and horror as the master withdrew its nerve fibers, I ate a golden apple, offering a slice to the master as he worked.

“Thank you. I hate these rush jobs,” he said, oozing his tail over the slice.

“May I ask why?”

The lebensman shrugged, inasmuch as it could, the slime on its face rippling. “It’s all just a game of Satan says to me. Satan says, ‘Convince Richard O’Shea that he is a monster.’ And I say, ‘Yes, Satan.’”

“Indeed.”

I suppose I could have charged down to the depths of Hell and demanded satisfaction of His Lord Satan; however, it was a long way to go for an enraging smirk and a “Celia started it,” so I crunched on my slice of apple and waited instead, as it seemed that Richard and my Queen would be returned without further struggle, now that Hell had had its say.

“Shouldn’t you have taken him down further?” I asked. “Shown him the sights? Given him the tour?”

The master lebensman rippled. “Satan had, apparently, but it wasn’t convincing enough. ‘Keep it simple,’ Satan said. ‘As banal as you can find. Let his imagination do the work.’”

“Ah,” I said. “Well, I shall take him back to neutral ground and threaten him with contracts until he picks one.”

At the word “contract,” the lebensman shuddered. “Can’t he do both? I’ve never understood.”

“Can’t be on two shelves at once. Is he providing a refuge from mundanity, or is he providing catharsis in the dark? He can cross over, but in the end, he must pick a shelf, or the readers will never find him.”

“Ah,” the lebensman said, clearly not understanding, but literary theory was often beyond the reach of the lesser demons.

The last of the tendrils withdrew, and Richard collapsed on the first level of Hell and sobbed. I hefted the mail bag over one shoulder and him over the other. Magazines snapped in irritation as the exit disappeared behind me.

“Put me down,” he said.

—

Victoria dumped me on the cold floor of the tunnel. “Down, as requested.” She hefted the bag more firmly on her shoulder; it reminded me of my college laundry bag, dripping similarly-disgusting fluids.

“You saved me,” I said.

“I suppose. They would have sent you back to the mortal realms eventually. Now walk. We’re going back to the editorial offices.”

“Why?” I moaned. “Why did you—” I couldn’t say it. I waved a hand at the bag.

“Easier to carry, and she can’t leave part of herself behind this way,” she said. “The last time I lost part of her, it took her forever to rot, and all of Fairy was in chaos for years. We had to withdraw from the mortal realms entirely, or lose the whole place to the demons.” She walked up the tunnel, quickly leaving me behind.

“Wait,” I said.

She didn’t. I limped up the path until I caught up with her; she started walking faster.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

She snorted. “Sorry for what? Trying to get into fairy without making a decision, even after I warned you not to?”

“Betraying you with Celia,” I said. I wasn’t entirely sure I meant it.

Victoria gritted her teeth. “I was put there to be betrayed. You were always meant to fall in love with her. That is fairy. No love may be mundane, reliable, or sane. It’s always hopeless and doomed but extremely desirable. You were, however, not meant to cross into fairy without making up your mind.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Why?” she said. “You only get to write in one genre, O’Shea.”

“What about pseudonyms?”

“Then you can write two names’ worth of crap. Both those proposals were crap, and you know it. Until you make up your mind what you’re actually doing, you will continue to write crap.”

After that, she refused to speak to me, and drew further and further away.

—

I hate being dragged into her plots. She got herself killed on purpose so he would feel like he had to save her. They made him kill her so he’d feel like a beast. Why can’t these people just be rational?

—

I struggled up a tunnel made of solidified meat for what seemed like millennia.

How could I live with myself? I had killed her. I should turn around and…no. I would not willingly go back to Hell. Who would? The worst man in the world would not willingly go into Hell, no matter how much he believed he deserved it. Only someone who thought Hell was not real would even joke about going there.

Unless he wasn’t wanted anywhere else.

Unless he knew that in order to find salvation, one had to go through Hell first. Anything else would feel false, I knew. With Hell, you knew where you were: people were monstrous—perhaps salvageable, but monstrous—the bad were punished, the good were found out, you had to admit your lack of innocence (and none of us were innocent) before you could get out again. The point of Hell was knowing when you deserved to be in it, and when you didn’t.

But fairy—

You never knew what you were going to get with fairy, except that it wouldn’t be dull.

As I ruminated, the tunnel became lighter, not that I had had any trouble seeing before. Less oppressive. The walls were made out of silvery skin that almost, but didn’t quite, reflect me. It showed a shadowed man, walking. I could have been anyone, least of all myself.

I could always turn around. I could always turn around later and admit that I was a monster. Every step brought a fresh wave of shame and contempt for myself. I should have fought harder. I should have killed myself, first. I cried, and to my ears, it sounded like a doll’s crying, fake in my own ears, mechanical, my tears running out of a well in my head that would have to be refilled using an eye-dropper. Eventually, I ran out.

But I kept going until the tunnel became shiner and shinier, and I could see my own reflection. I was an old man with a long beard and a magician’s robe. I was a thief stealing a magic lantern from a cavern…and taking a single jewel to call his own. I was a hero, come from humble origins, to save the world. I had chosen Fairy.

—

I got tired of waiting for O’Shea to stop admiring himself, so I sent two mizzerah brownies to bring O’Shea along. He’d made up his mind, and even Hell knew it.

The mizzerah, dressed like extremely short human hookers with knobby green skin and stiff, sloppy Mohawks, dropped O’Shea at my feet. He opened his eyes blearily.

It was time for the paradox.

“Look,” I said, pointing at the throne made out of glass shards and sparkling with blue-green bloodstains. I’d arranged Celia there, tying her various pieces and parts in place with glittering silver scarves.

He took one shuddering glance at Celia’s carelessly-stacked body parts and looked away.

“Look,” I said, pointing at the shimmering nebulae out of which the floor had been made, whole solar systems being crushed and distended every time the Queen summoned us to dance before her. The sins of disco were great indeed, and long overdue for change.

He winced and stared straight ahead.

“Look,” I said, pointing toward the rest of the court, gaily-dressed sylphs in legwarmers and muscled trolls with razor blades dangling from their ears, all of them staring at him very nearly pop-eyed.

I wasn’t the only one ready for a change.

He closed his eyes.

I grabbed him by the chin and turned his face back toward my Queen. “Close your eyes and I’ll rip your eyelids off.”

“You wouldn’t—”

I opened my visor and gave him my best editorial look.

“You would,” he said.

I nodded.

He took a deep breath and watched as Fairy changed. The glitter faded. The glass throne turned to well-worn leather. Heavy tables, divided into carrels, rose from the floor. The walls lost their peacock feathers and grew shelves, then books whose spines read gibberish. O’Shea glanced toward them longingly (he’s a writer, after all), and I jerked his chin back toward my Queen. He had to finish it.

I didn’t change. I never change.

Sitting in a huge, leather-bound chair was a tiny bit of a girl with long, dark hair and thick glasses. She was wearing a school uniform with red embroidery on her shoulder and reading a book.

O’Shea gasped. “Celia?”

I grabbed his shoulder. “Her name isn’t Celia anymore.”

He looked, if anything, even worse than he had in Hell. “I loved her,” he said. “And now she’s gone.”

“Yes,” I said, trying but not succeeding in keeping the irritation at his stupidity out of my voice. “That’s what it means, to be the best writer of a generation. You change everything you touch, and you can never get the old ways back, because you can never write someone else’s story, not really.”

He watched the girl, who couldn’t have been more than eight, reading the book. Tears welled up. He wiped them away with the side of his forefinger, then looked at them in the soft light coming from the green-shaded desk lamps at the carrels. “I should have chosen hell. I should have chosen hell.”

I grinned at him, and he stared at my sharp teeth. “Let us kneel.”

As we knelt, the little girl looked up. Her eyes were filled with stars.

—

I printed the whole thing out. Eight hundred pages. And dropped it on her desk.

Victoria looked up. She was back to being human again, which I found slightly disturbing. We had separated (but not divorced), while declaring to everyone that we would remain the best of friends. I would have liked to stay with her, but she insisted that she refused to be made a fool of, even if her then-Queen had ordered it.

“What’s this?” she asked.

“The project I’ve been working on, wouldn’t tell you about. First draft.”

“It’s a bit long, isn’t it?” But she pulled aside the title page—The Whispering Tree by Richard O’Shea—and started reading.

Emma was a precocious sort of girl who never felt the need to take her parents’ advice, so when her mother (a tall storklike woman named Jascinta) and her father (a stunningly dapper man named Fred) told her not to read under the willow tree in the back of her new Grandmother’s house, she shrugged.

“If this is Grandmother’s house,” she asked, “then whose mother is she? I’ve never heard of her before.”

Her mother and father shared a sweet, smug smile and refused to answer her, which, she felt, justified not only her carrying the leather-bound edition of Through the Looking-Glass from her so-called “Grandmother’s” library and a glass of lemonade to the bottom of the willow, but everything, everything, that happened afterwards.

Her only regret was what had happened to the book.

“Could be interesting,” Victoria said, turning the page with satisfaction. “You know you’re missing a comma, don’t you?”

—

THE END.

September 25, 2013

The Garlic Ice Cream Incident

Last weekend was the Pikes Peak Urban Gardens’ garlic festival. It wasn’t big, and there wasn’t as much garlic as you might have expected. I mean, a garlic festival, you expect things to reek of garlic. You expect a six-foot dancing garlic bulb and a raw garlic eating contest. Roast meat slathered in garlic–perhaps even on a spit.

Maybe someday. Now it’s small enough to fit in a garden center that doesn’t take up even a small block.

There was a guy playing guitar. A guitar-shaped guitar without a lei of garlic around its neck. He played non-garlicky songs. There were food trucks outside the festival. We got an iced coffee–one of the trucks was run by a guy that does food stuff up by where my husband works. We passed by someone selling juice out of the back of a smart car. There was supposed to be garlic popcorn, but it hadn’t got running yet. There was a video of how to grow garlic: it ran for ten minutes and started on the half hour. It was like one of those movies that you see in an art museum, on a loop. It’s not something you couldn’t find elsewhere; it’s just there to give context.

We stopped by all the tables. I ate a salad from Seeds Community Cafe, which was a good thing. I’d heard of them but hadn’t bothered to go because I thought they were a bunch of do-gooders with more ideals than sense, and who couldn’t cook. But the salad was good, and now I think I’ll go check them out sometime soon. I ate all of the salsas from the salsa contest; there was a Japanese salsa (which turned out to be a green salsa with tamari sauce) and a beet-garlic salsa (which sadly tasted nothing of garlic). I had a veggie taco that was mostly potatoes. Good, but it reminded me of why being a vegetarian is hard: all that freaking starch.

It was a small festival, okay? We didn’t say for the cookoff or whatever else there was. We stayed for maybe an hour. It was good, a good place to be.

But what I really want to tell you about was the garlic ice cream.

What did you think of, when you first read that phrase? Garlic ice cream.

I think it’s important.

Did you decide it was going to be disgusting? Did you decide that it was interesting, and you’d have to try it? Would it help if I told you that it was made by the cooks over at Blue Star?

We tried it. We stood in line and got a two-ounce cup of it with a little spoon. Lee took a bite first and decided it was godawful.

I took a bite. At first, it was awful. But I’ve tasted weird food before, and I love finding out how the mind works. I know this stuff is made by people who would otherwise only make delicious things. This horrific flavor sensation, of vanilla ice cream with raw garlic mixed in, isn’t all there is.

Then I think, “cold garlic cheese spread.”

There’s a snap in my mouth, and the ice cream tastes different. Now it’s not vanilla ice cream with garlic on top. Now it’s chilled garlic cheese spread, thinned out with milk and cream, and the garlic’s not raw, it’s roasted.

Two completely different flavors; each of them was more or less all in my mind. An optical illusion of the taste buds.

It wasn’t just me, either. I told Lee, and the same thing happened to him.

We both finished the entire thing, sitting at a table under an awning, listening to Mr. Guitar Player pick along. Soon after that, we left and went over to Ivywild. They gave us beer coupons at the garlic festival, so we went over there, got a sausage plate, and drank our beers. The sausage plate, by the way, had sweet pickles on it, which were apparently good if you like that kind of thing, which I don’t. Guh. I tried one, but no–there was no snapping into place of the flavors, no sudden reinterpretation.

I’ve been thinking about this for days.

About how our minds affect our taste buds. About how our opinions affect our perceptions. About how optimist, pessimist, and realist don’t really cover this. (The pessimist is guaranteed to hate garlic ice cream; the optimist is guaranteed to at least try the garlic ice cream but will probably taste the same thing the pessimist does; the realist is guaranteed to eat garlic ice cream. What is it, what outlook on life is it, that can go, “this isn’t garlic ice cream–this is cold garlic cheese spread”? A sales mentality?)

I keep running into things that make me go, “You’re not seeing what’s in front of you. You’re seeing garlic ice cream, not cold garlic cheese spread.”

Because I’m a writer, I think about how this affects my books. Is a book better because people say it is? Once Twilight became Twilight, was it all but impossible for some people to like it?

I’m still pondering. How much of what I see is completely warped by my opinion? Not just a little better or a little worse than I would otherwise think it? But completely different? How much of what I wrote above is even true?

I don’t know. But I do know that I have Exo protein bars (made with cricket flour) coming to the house. I hope they get here soon.

September 18, 2013

Free Fiction M–WEDNESDAY: The Society of Secret Cats

This one is late this week because…erm…I found more typos than I could live with. So–this will be up until next Wednesday, if you please.

Also! A preview of the forthcoming “King of Cats” follows the story. Sooo happy with that one.

What if cats were really there to guard your dreams?

Lost in the Forest of Dreams, the dashing, handsome cat Ferntail must rescue his human girl from her horrible nightmares, nightmares that come from outside her mind. Will a mysterious and beautiful cat from The Society of Secret Cats help lead them out of the forest…or further astray? Now (or soon) available at Amazon, B&N, Smashwords, Apple, Kobo, Powell’s, and more.

—

The Society of Secret Cats

Mice are delicious. But even more delicious are monsters, ghosts, and things that go bump in the night. Your mother or father might tell you that they are all in your head and that you’re just imagining things. In a way, they’re right. Monsters are all in your head.

But you’re not just imagining things.

—

I was inside Jaela’s head with a tasty monster called an Aranea, dribbling slime and trying to skitter out of the way on its spider claws, when the entire world of dreams shook, as though being shifted around by an earthquake.

The Aranea crawled up the wall of Jaela’s bedroom, clinging to the ceiling, too scared even to spit acid at me, as I tried to keep Jaela from waking. It is bad when a dreamer wakes before you have eaten the monster, because the monster is able to escape the dreamer’s head, sometimes for a short time, sometimes for a long time, and cause mischief.

When I was a wee kitten, I let one of her monsters get out, and it threw a tantrum in her room, only disappearing when her parents appeared to find out what was the matter. Jaela hid in a corner and screamed, and wouldn’t stop screaming even when her parents asked her what was the matter.

She was punished for breaking toys and writing in crayon strange words in letters and languages that none but those who walk dreams could ever read.

But, even as a kitten, I could read them: Stupid cat.

It was the first time I had been called a cat instead of a kitten, and I found that it filled me with anger, to have my profession insulted by having a newborn baby dream-walker compared to my fine teachers.

And ashamed that I had let the dream escape.

Inside Jaela’s dream, I purred, trying to soothe her. Sometimes she woke suddenly, looked around for a few seconds, and then went back to sleep as she shifted to a more comfortable position.

Not this time.

As the dream world shook, it changed, becoming less like Jaela’s closet, bedroom, house, and city, and more like a forest full of long trees with even longer shadows.

The shaking turned from a constant rumble into footsteps. Some gigantic thing was coming toward us through Jaela’s dream, toward her dream-self. She whimpered, squatted down on the moldy leaves of the forest floor, and wrapped her arms around her knees.

“Shh,” I told her. “I will defend you. No monster will hurt you while I am here, my princess.”

It was not often that I spoke her in dreams.

“Ferntail?” she said. “Where are we?”

“I do not know,” I said.

“We are in the Great Forest,” hissed a voice.

I quickly looked up and saw the Aranea above us, on one of the trees. I growled at it, and it backed up the trunk.

It laughed through its long teeth at me. “You’ll never catch me here, dream-walker. There are too many ways for me to escape, not like the corner of some bedroom, where you can trap me and eat me.”

“Run away, little nightmare,” I said. “Lest something bigger come along and snap off your many legs so you can’t run away anymore.”

“Please,” Jaela said. The ground was shaking even harder than before.

I shifted form, until I walked like a man on my hind legs, and picked up Jaela in my arms. I ran quickly through the forest, ignoring the branches that whipped across my fur, protecting Jaela in my arms. She put her arms around my neck and clutched me hard, but not so hard that she couldn’t breathe.

We ran, the footsteps growing louder, until I came upon a little house in a clearing of the forest. I hadn’t noticed that the forest was dark (we cats can see well in dark places) until we reached the clearing, and bright moonlight shone down, making the long blades of grass shine white. The windows of the little house were covered with wooden shutters that let only tiny cracks of light through, but the chimney was puffing smoke. Jaela shivered in my arms, and I realized she must be cold, a human outside at night in only her nightgown.

I stepped toward the house when the hissing voice laughed at me again. “I wouldn’t do that if I were you.”

I looked up; the spiderlike Aranea hung above us, as though we hadn’t moved a step. The tree even looked the same, for all I could tell.

“Get back!” I swiped at it with one paw, cutting across one leg, which dripped clear fluid onto the forest floor.

“Sssss…no need to be rude,” the Aranea said. “But I would avoid the house if I were you. Witches live in houses in the middle of the wood. A word to the wise.”

Jaela shivered again. “She is cold,” I explained.

“Better to be cold than eaten,” the Aranea said.

“She cannot be eaten in her own dream,” I said.

The Aranea dribbled green slime onto a foreleg and rubbed it over the wound in its other leg. “But she is not in her own dream any longer, as I said. This is the Great Forest, not some little child’s dream. This is something bigger.”

I turned around in a circle slowly as the shaking, quaking footsteps grew ever closer. “What is it, then? I have never been here, nor have I ever heard of it.”