DeAnna Knippling's Blog, page 97

December 16, 2010

Formatting for Lulu, Part 1

I've formatted three books for Lulu.com now (for private use only), and I'm going to record my lessons here, mostly for my own benefit, because I keep having to look things up! Lulu.com is a place where you can self-publish your own books; I've been using it to make copies of books for gifts. Part 1 covers the initial set up and text formatting for your book. Part 2 will cover making a book cover and putting it all together. ---

Go to Lulu.com.

Log in or sign up. (It's free.)

From the My Lulu tab, select the Dashboard sub-tab.

On the left sidebar, under My Projects | My Project List | Start A New Project select the type of new project you want (e.g., Paperback Book). You will go to the first page of the Content Creation Wizard, Start A New Project.

In the Working Title field, type your title. You can change this later.

In the Author fields, type the name you want to use, either your own or a pseudonym.

Under the What do you want to do with this project? menu, select the radio button that shows the appropriate option. (I select the first option, Keep it private and accessible only to me.)

Click the Save and Continue >> button. The Choose Your Project Options page should appear.

Under Paper, select the desired paper type. Publisher grade is cheaper, but there are only two paper size options. I have used Standard paper only and have liked the quality. If you buy 5+ books, there are discounts for Standard paper books.

Under Size, select the All tab, then select the desired size option. I have used Pocket size and U.S. Trade size. I didn't care for Pocket size; it was so small and hard to read, because of the stiffness of the book. I haven't received the U.S. Trade books yet. Note: Some sizes cost more than others.

Under Binding, select the desired binding. I have used Perfect-bound and liked it.

Under Color, select whether you want color pages in the interior (not the cover). You can have a color cover regardless of which option you pick. Note: color is a LOT more expensive.

Click the Save & Continue >> button. You should go to the Add Files page. Note: You can change any of these options later, but your template will depend on your page size; page size is the most important option here.

Under the Add Files | Upload | Before You Upload header, click on the download a template link. This should download a zip file to your computer.

Open the zip file.

Open the folder that has the page size on it.

Save the file with the page size name and template in the file name to your working folder for the project. Note: If you're using the method of cover creation that I list here, don't download anything else. Otherwise, you're on your own.

Open the template file and re-save it as the file for your book (e.g., bookname.lulu.doc). Note: Don't save MSWord files as .docx; I seem to remember that you can't use them.

Copy all the text in your story, paste it into the new file, and save it. Close your old file (to make sure you have a clean copy and don't format the wrong file.)

This is the point where I format my pages:

Note: I use MSWord 2007. I'm going to assume that if you use 2003, etc., you can figure out (or look up) how to do the commands for other versions, etc. I'm also going to assume that you don't need a table of contents. The template will set up page numbering for you. You can change it and you can add a header with your name/book title on alternate pages, but those are topics for a different day.)

Create a new style in the template called "Text." I do this by highlighting any text, then selecting Home | Quick Styles bottom arrow | Save Selection as a New Quick Style..., typing "Text" in the name field, then clicking the Modify button.

Modify the Text style as follows: Style for following paragraph Text, Font Garamond, Font Size 11, Justification Justify (both sides aligned), Spacing Single Space; Select Format | Paragraph and set the Indentation | Special Option to First Line 0.2" and the Spacing Before and After options to 0 pt. At the top of the Paragraph window, select the Line and Page Breaks tab and make sure all Pagination options are unchecked. Click the OK button. Note: for a list of fonts that Lulu.com will accept, click here.

Select all the text in your story by pressing CTRL-A.

In the Quick Styles area, select Text.

Remove all tab characters (you've set up an automatic tab that's smaller and more appropriate for your book). Press CTRL-F to pull up the Find and Replace window, click the Replace tab, then click More | Special | Tab character. Make sure the Replace with: field is blank. Click the Replace All button.

Remove all extra hard carriage returns between paragraphs (you can do a find/replace on this using the steps above, inserting two of the paragraph marks in the Find what: field and one in the Replace with: field).

Change all double spaces (e.g., after colons or periods) to a single space using the find/replace fields.

Change all underlining to italics using the find/replace fields. Leave both fields blank, but click in the Find what: field and press CTRL-U. Click in the Replace with: field and press CTRL-I.

Replace all soft carriage returns (line breaks) with hard carriage returns using the find/replace fields. If you don't, you'll have huge blanks between words.

Format your chapter headings as follows: Highlight the chapter heading and select the Heading 1 option from the Quick Styles area. Right-click Heading 1 and select Modify... Format Heading 1 as follows: Style for following paragraph Text, Font Garamond, Font Size 16, Bold, Justification Center; Select Format | Paragraph and select the following: no indentation, Spacing Before 48 pt After 16 point. In the Paragraph window, click the Line and Page Breaks tab and make sure the Keep with Next and Page Break Before options are selected.

Click the OK button.

Remove all hard returns between your chapter headings and text.

Remove all special marks (e.g., #) to show scene breaks, using find/replace.

Format your title page. Type your title, press Enter, type "By", press Enter, type your name/pseudonym, and press Enter. From the Insert tab, click the Page Break button. Highlight all text on your title page. From the Home tab, select the Title option from the Quick Style area. Format the Title option as follows: Style for following paragraph Title, Font Book Antiqua, Font Size 24, Bold, Justification Centered. Either leave "By" and your name the same size or change them to a 14 pt font.

Format your copyright page, which should go directly after the title page. In Normal style, type the information at the bottom of this blog post (I was having trouble putting it in the list, so screw it.)

Format your second title page, which should have the name of the book only. Type the title and format it with Title style.

Insert a blank page after your second title page.

Note: To insert a dedication, insert TWO pages. Put the dedication on the odd page and insert a blank page on the even page after that.

Optionally, check that all your chapter headers fall on the right (odd-numbered) side by inserting blank pages at the end of chapters to force even-numbered chapter header pages to odd numbered pages.

Select the Print Preview option from the Quick Access Toolbar and check that all your pages fall as you want them, that you have no strange formatting issues, etc.

Go back to Lulu.com.

Click the Choose File button, choose your file, then select the Upload button to upload it.

Click the Make Print-Ready File >> button. This may take some time as Lulu converts your file.

Congratulations! Your text is now formatted and uploaded. Part 2 will have how to make a book cover, but I'm sick of being helpful with the type type right now. --- Copyright © "YEAR" by "Your Name" Cover design by "Name Name" Book design by "Name Name" All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the author. Printed in the United States of America First Printing: "Month YEAR" Personal Galley Proof: Not for resale Printed in the United States of America

December 9, 2010

Brains-eating Song

In all honor of Tom T. Hall, I hereby make this satire: In some of my songs I have casually mentioned The fact that I like to eat brains This little song is more to the point Roll out the corpse and don't mind the stains... I like brains. They're good gray, pink, or pus-rotted yellow! I like brains. They help me unwind and sometimes they make me feel mellow (makes her feel mell-ow) Kidney's are too rough, sirloin costs too much, tripe's smell still remains This little refrain should help me explain as a matter of fact I like brains (she likes brains) My spouse often frowns when we're out on the town And I'm wearing a new pair of arms He's sipping Scotch while I'm nibbling a notch From the neck of a waiter screaming alarms, but... I like brains. They're good pink, or pus-rotted yellow! I like brains. They help me unwind and sometimes they make me feel mellow (makes her feel mell-ow) Kidney's are too rough, sirloin costs too much, tripe's smell still remains This little refrain should help me explain as a matter of fact I like brains (she likes brains) Last night I dreamed that I was gunned down And my head was removed from my spine Aw, the gunner saw my brains start to leak down the drain Tasted them and said they were sublime! They were quite fiiiiiiiiine! I like brains. They're good pink, or pus-rotted yellow! I like brains. They help me unwind and sometimes they make me feel mellow (makes her feel mell-ow) Kidney's are too rough, sirloin costs too much, tripe's smell still remains This little refrain should help me explain as a matter of fact I like brains (she likes brains)

November 26, 2010

Book Release!

I was really straining to try to come up with something deep for my blog over the last few days. "I have to write something for release day...I better make it good!"

Yeah, I'm sick, and most of my functionally witty brain cells have curled up with a cup of hot water (all I can taste of tea is bitterness), a cough drop, and a blankie. So "good" will have to be relative today.

Choose Your Doom: Zombie Apocalypse has been released online at Doom Press, Amazon, Borders, Barnes & Nobles, Books-A-Million, Powell's, and many other places, I hope. (The publishers are still in discussion over some pretty cool stuff, but I don't want to talk about it until they say it's a done deal.)

Book and mortar stores? Not so much. If you see a copy out in the wild, let me know! But because this is the publisher's first book, bookstores are a tad bit reluctant to stock it. The next part of my evil plan is, as soon as I get author copies, to schlep books to the stores in town and say, "Pretty pretty want one?"

I'm pretty sure the answer will be "yes."

I've tried to contact various local bookstores and conventions by e-mail, but that seems to be the perfect way to be ignored, so I'm going to try again with materials in hand and my face at the door. If you know of a book store in Colorado that I should check out, let me know. I'm planning on hitting Black Cat, Hooked on Books, B&N/Borders in town (they're only stocking books for the signing, I believe), Poor Richard's, Compleat Games and Hobbies, and Tattered Cover in Highland Ranch. If you have contact info, even better :)

Here are the signing dates:

December 11th, South Colorado Springs Borders, 1-5 p.m.

December 12th, Park Meadows Borders, 1-5 p.m.

If you're in the Colorado Springs area and want me to sign a book, let me know. I still don't have my books yet, though!

I have had a lot of support on this book, not just from the publisher side of things, but from people I know and people that I've met through the course of trying to get word out.

Thank you. It's humbling to have other people on my side; I will do my best to be on your side, too.

Finally, as always, this book wouldn't be happening with out Lee and Ray. Without them, I wouldn't have the reservoir of strength to do this, either the writing side or the public side. And I certainly wouldn't be happy enough to be able to crack jokes about it.

November 15, 2010

Inside the Story

I had a really good run of slush stories to read for Apex Magazine in the last few days; I sent up about three issues worth of stories to the editor, Cat Valente. Yay! Good stories! But there were some stories in there that didn't make my personal cut, and I've been trying to figure out what made the difference for me. Instinctually, I knew within a few lines whether the story was going to work for me or not - but not logically. The ones I accepted, I didn't think "this story is good" or "this story is not good." I just read, in some cases until 2/3 of the way through the story, and knew that even if I didn't think Ms. Valente would like the stories, it would be dishonest of me not to send them to her: each would be a credit to the magazine and enjoyable to a majority of readers, even if they don't fit her vision (and I can't argue with that; she's picked some almost unbelievably magical stories, and I have enjoyed every one). Sadly, you can't publish everything you like if you're going to pay the writers. However, with the stories that I didn't like, I thought, "this story isn't what I want" almost immediately; I was extremely conscious of reading the story, as a story, all the way through. When I read the stories I liked, I went somewhere else. When I read the stories I didn't like, I stayed on the page. Logically, there was no substantive difference between the writing in two sets of stories. When I went back and compared the sentence-by-sentence writing of the two sets of stories, they weren't much different. The writing in the good stories had, in most cases, a slightly higher level of taste; they didn't use a lot of adverbs, had active verbs, etc., but weren't poetic or startling or anything (except in one case, but the experimentalism in the sentences wasn't consistent throughout, and that's not why I picked the story; the writing was a distraction rather than a natural addition, but the story was good enough that after the first page, I didn't care). But here's the trick: I didn't consciously notice the writing in the good stories until I was further along in the story, after I'd made my decision. It might have mattered subconsciously, but not logically; I didn't use the quality of the sentence-by-sentence writing as the touchstone for my decisions. Something I did notice was that the good stories were never "outside" the story. I'm not sure how to explain this; I'm just barely getting a feel for it. In the good stories, something happened, the characters reacted to it, which made something else happen, which made the characters react to it... The writer never described the story itself, never explained backstory unless it was the kind of thing the character felt necessary to explain (as though the character were telling me the story to my face), never talked about right and wrong. Never talked to the reader. Never judged. I don't think I'm saying this right. It felt like the writers had been hypnotized and had entered their own worlds and were babbling about what they were seeing and feeling, right in the moment, as though conscious thought were something abandoned. I couldn't see any signs that the writers were outside their stories, that they made any conscious judgments about their stories. I don't know whether they really did or didn't, but that's how it came across, as though none of it were deliberate or planned or tweaked. As I'm slowly improving in my writing, I suspect that the technique here is to build up your ability to write well, consciously, painstakingly culling adverbs, writing believable dialogue, etc., but turning all that off when you're sitting down to write, turning off all judgement of right and wrong, all ability to see anything but what's going on in your head as you type. It doesn't sound that hard, as I type this, but I know, sitting down to write, that it can't be easy, or everyone would be doing it. I'd be doing it, doing it consistently.

November 12, 2010

Distraction, Mistraction, Untraction, Alack-tion

Since a couple of writers whose advice I generally follow have posted on the nature of distraction (and because I've made my wordcount for the day), I'm going to chime in here. Believe me, I understand the irony of writing a distracting blog entry about how to resist distractions. I prefer to think of it as cruelty rather than blatant ignorance. Everyone seems to be talking about trying to stay focused and disciplined. I know, I know the temptation of abandoning the slog of one word after another, because it's just too hard sometimes. But I suspect staying motivated as a writer is one of those paradoxes of life, like "Love is the best" and "Love is the worst." "Writers have to stay focused." "Writers have to stay distracted." Here's my logic:

All writers have to live with distractions.

Defeating a distraction is distracting.

When it's more interesting to do the dishes than write, perhaps your brain is trying to tell you something.

Writing should be more fun than doing the dishes; if you're not having fun, why would anyone else?

Maybe your brain is trying to tell you something, like, "I'm bored" or "I'm tired" or "I'm hungry" or "I don't have faith in this whole writer thing."

Maybe your brain is looking for something.

Maybe you're getting in the way of finding what it is, by strangling your distractions.

Maybe you're just about to daydream.

Maybe daydreaming is why you wanted to be a writer in the first place.

Maybe your distractions are opportunities to daydream.

And come up with something that will make you want to write.

So don't kill the goose that laid the golden egg by being too disciplined.

Play.

You enjoy this. Don't forget.

October 30, 2010

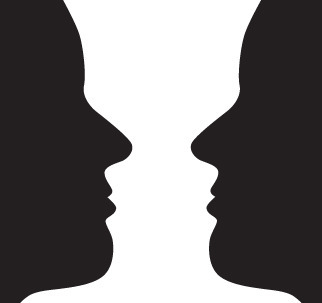

L is for Illusion

For some reason, while I was out for my run today, I had one of those brilliant flashes of insight that end up sounding kind of lame when approached from a more rational direction. Here's the insight: Writers don't write stories. See what I mean? But let me explain. When I sit down and write, I have something that happens in my head. I translate this into words. I hope that someone will eventually read it, so I send it out into the world in some form or other. They read it. Something happens in their heads. Where is the story? On the page or in my/the readers' heads? Words are nonsense. That whole "A rose is a rose is a rose" thing by Gertrude Stein is an exercise in nonsense. (For example - say the word "pizza" fifty times. Chances are you'll have a second or two where the word doesn't mean anything, it's just a couple of syllables.) Words are nonsense out of which our brains make sense, whether there's any sense there or not.

For some reason, while I was out for my run today, I had one of those brilliant flashes of insight that end up sounding kind of lame when approached from a more rational direction. Here's the insight: Writers don't write stories. See what I mean? But let me explain. When I sit down and write, I have something that happens in my head. I translate this into words. I hope that someone will eventually read it, so I send it out into the world in some form or other. They read it. Something happens in their heads. Where is the story? On the page or in my/the readers' heads? Words are nonsense. That whole "A rose is a rose is a rose" thing by Gertrude Stein is an exercise in nonsense. (For example - say the word "pizza" fifty times. Chances are you'll have a second or two where the word doesn't mean anything, it's just a couple of syllables.) Words are nonsense out of which our brains make sense, whether there's any sense there or not.

`Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe: All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe.

Is that sense or nonsense? Lewis Carroll meant something (if you look it up in Annotated Alice you'll see what), but he didn't bother to explain it to his readers, although I suspect he might have, to Alice. But even if you don't know what the words "mean," you still try to make meaning out of it, the same way you make shapes out of clouds. The picture above - is it a face or a vase? Neither; it's an optical illusion. Our brains fill in meaning, but it's essentially a Rorschach blob. The picture happens inside our heads - the creator's and the viewers'. Same thing with words.* Writers don't write stories; we imagine them. Then we create the illusion of a story with words (pictures, etc.). If we're good, we get the readers to imagine very nearly the same story that we imagined. It's why some people write every single freaking detail and still can't write worth a damn. You can write a photograph, but what the reader "sees" is an Impressionistic painting, or even modern art - even in classic books. People tend to skim description. It's why some people write exactly what happened in their imagination, and the stories suck. They're not creating the illusion; they're recording. It's why the writer doesn't work in a vacuum; good readers are essential. Not just nice. Bad readers = sucky story. (Get a five-year-old to read your intellectual thriller and you'll see what I mean.) It's why a writer doesn't have to be perfect in order to sell a million books; the story comes from the readers, not the words. The words are an illusion that we often forgive, when we really want that story in our brains. It's why there better be some damned description at the beginning (I kick myself on this), because there is no illusion. So. I write stuff. People are going to call what I write stories. But the words aren't the story; they're just an illusion. If you're good, that illusion sparks the story in the reader. But the words aren't worth crap without that other imagination to make it fly. *And movies. Nothing actually moves.

October 23, 2010

Zombie Change BAAAAD

I'm a Johnny-come-lately when it comes to zombies.

I'm okay with that, because I tend to see them a bit differently than the people who dealt with them originally; I think zombies are funny, and public tastes seem to be with me at the moment.

Sure, zombies are scary - but they're funny, too.

People talk about how zombies symbolize the downfall of modern civilization or how we, as a society, are shooting ourselves in the foot in various ways, by a materialistic, corporate culture, or by treating various types of people as less worthy than others.

I see it differently. Zombies are change.

CHANGE IS BAD.

What causes zombie outbreaks? Science.

SCIENCE IS BAD; YOU LEARN STUFF, AND THEN YOU HAVE TO CHANGE.

Or, if the explanation's not science (and if one's provided), then the explanation is usually "some fool was messing around with something he shouldn't have."

CURIOSITY IS BAD.

The zombies come, and society is never the same again. The people you never thought would hurt you (either because they had no reason to, or because they didn't have the strength to do it), they're out for your brains.

And anyone who comes in contact with change, they're corrupted, so KILL THEM TOO. Because anyone who changes is stupid and violent, and there are traitors within your midst.

October 21, 2010

Eulogy for an Accidentally Deleted Story

What does it mean when you're relieved when you lose a story? When it's just too much to contemplate reading it again? Let alone editing it? I find I had a hard time dealing with some of my darker predictions. They seemed like simple math, a tale born of the inevitable. Does it mean that I dread the future, because it will be too terrible to want to see? Will people born after now see it as the ordinary, the unexpected? Would that be better or worse?

What does it mean if you're relieved that you've lost a story? When you dreaded having to fix what went wrong with it? You're glad it's gone; you won't make an effort to get it back? You' made all the decent efforts, but what it comes down to was rewriting the whole damned thing? And you won't, no matter how many people, inside and out, tell you to do it?

Does it mean you've given up?

---

I did it. I accidentally deleted the draft of a story, then (later) thoughtfully ran Crap Cleaner and deleted my trash before I mailed emailed myself the draft. I have three copies of an empty folder for backup. It's gone.

Goodbye, story. Like an angry teenager writing bad poetry in a revealing, tacky lace blouse, you were up to no good. But this wasn't what you deserved.

October 19, 2010

Writing is One Big Fat Problem

I've been working on writing better short stories, part of which involves reading slush at Apex. There was no instruction manual on how to do this, and I still don't know if I'm doing it right. Nevertheless, there are some things I'm starting to pick up on, and I think I'm a better writer for it.

One of those things is the insight that every piece of commercial fiction has a problem. Most commercial fiction follows this pattern:

Problem

How the main character attempts to solve the pattern

Solution (a definite success or failure in trying to solve the original pattern)

This pattern is also known as:

Beginning

Middle

End

Literature and experimental fiction may or may not follow this pattern, but commercial fiction at least includes a problem: the rest of the story might be implied (especially in flash fiction), but the promise of the story is there.

I've been seeing some submissions to Apex that don't have problems, they have situations.

What's the difference?

A situation is what, in general, is happening. Aliens are taking over the planet! is a situation.

A problem is a roadblock in the way of a character's goals. Aliens are taking over the planet and my server went down in the middle of a boss fight! is a problem. Aliens are taking over the planet and they're killing everyone…including me, if they can catch me! is a problem.

The difference is that the character may or may not have to respond to a situation; a character must respond to a problem, or there will be unacceptable consequences, for that character, no matter how noble or petty.

You might have a character who doesn't care whether the aliens take over the planet, as long as the servers stay up. No problem–literally. You can write a story about that character who doesn't care, while the rest of society collapses. It's ironic, but it's not actually a story; there's no beginning, middle, and end.

But add a problem that the character cares about–Aliens are taking over the planet but the servers are still up only now I can't get pizza–and you have a story. The main character goes through these steps:

Problem: no pizza

Attempt to solve: call for delivery. Nobody answers.

Attempt to solve: walk three blocks to pizza place. Nobody home.

Attempt to solve: break into pizza place and start making pizzas, but don't know how. Start fire.

Attempt to solve: call mom for advice on how to make pizza, she's being attacked by aliens and hangs up.

…and so on, until Our Slacker has solved the problem and eradicated the aliens, obtaining pizza in the process, or has failed so definitively that no further action can be taken to solve that problem: Our Slacker almost succeeded, but the aliens have captured him and extracted all his memories of pizza, returning him to his home with no idea of the humanity he's lost.

If you want a slightly less trivial example, take the story of the Hero who Must Save the World.

Problem: Hero must save world.

Attempt to solve: Whine "why me" a few times and get out of it

Attempt to solve: Try to trick someone else into doing it

Attempt to solve: The bad guys come and kick your butt until you're more angry at them than you're afraid of actually getting started, etc.

The story doesn't end until the problem is solved or it very definitively can't be. People tend to like the first better, unless you want to scare them, in which case the second is a pretty good option. I also like the stories in which the character solves the problem in such a way as to make the problem worse. There are all kinds of variations you can take.

If you're like me, as you're plotting and/or editing your story, check to make sure you have a problem, that every action your main character takes is trying to solve that problem, and that problem is solved at the end of the story. It sounds mind-bogglingly simple until it comes time to apply it to your own work, of course.

Note: all the attempts to solve the problem should fail until you get to the very end. If you're like me, you can give your characters a moment of success, then laugh as you jerk it away from them. But if the character succeeds before the end of the story, then you're going to have to come up with a different problem.

This sounds like a clever solution until you realize that the end of the story no longer has anything to do with the beginning of the story. Readers tend to notice this; it can be forgiven but generally cheeses people off. "I thought I was reading a story about Our Slacker getting his pizza, not a romance about love among the storks!" Fling!

If you're in a college course, this idea is sometimes called "unity of action" or "put the remote down and stop changing channels in the middle of my TV show."

Generally, if you must have that alien/slacker comedy with a touch of stork-on-stork action, it's better to make one problem a substep of solving a larger problem, such as arranging a certain long-legged romance as part of getting the last pizza on Earth away from the aliens.

Literature and experimental fiction are different, of course.

By my lights, literature is exploring situations, not problems. Lord of the Flies wasn't mainly about how a group of kids got off a desert island, but how they acted when removed from society. The story didn't end because the characters got themselves off the island (the solution to a problem), but because they were removed from the situation. Our delight in the book comes from the ideas of the book and how they were explored, inspiring us to think about them even further, not because some hero saved the day. (There are no MacGuyvers on the island with Piggy, unfortunately.)

Experimental fiction is a different kettle of fish; it looks at the rules of story and then pushes them around and plays with them, much as a poet plays with words. The rules of poetry aren't the rules of prose, but you have to know the rules of prose before you start playing with poetry. Grammar? Spelling? Of course. Some poems have very strict, known rules; others have very strict, unknown rules. Unknown by the reader, that is. The poet will know, even if it's only subconsciously. Experimental fiction writers have usually mastered the regular forms of stories, and are distorting them, remixing them, deconstructing and reconstructing them. It is by experimenting with fiction that rules are shaken up or destroyed. Whether a piece of experimental fiction is meant to be commercial fiction, literature, or something else is entirely up to the author.

September 30, 2010

Adventures in Writing

As you may know, I am trying to launch myself as a professional writer. This has had its ups and downs, mostly a series of small, soul-eroding downs interspersed by a few interruptions almost-unbelieved ups.

One of the series of small, soul-eroding downs is the short story rejections I receive. I am at [checks Duotrope] 23 short story rejections since I started keeping track, and no acceptances. One maaaybe.

Obviously, I'm not writing the kind of short stories that people pick up, fall in love with, and can't help but buy. You can tell me comforting things if you like, that my stories are good enough and it's them, not me. That may very well be the case; however, it remains a fact that I'm not making so many sales as to offset (in my mind) the number of rejections I'm getting. Maybe it's because I'm an attention hog. I know, many people do not see me as an attention hog; I've learned that attention is an investment. Also, I like to listen to other people talk, so I can rip off their stories and personalities as fiction later. Sorry about that.

Let me point out that I could have just said what I was going to say without writing paragraphs on paragraphs of blather. I want just that little bit more of attention, you see, to feel witty and wise for just a moment more.

Title: New Slush Editor at Apex!

At any rate, I was at the point where I needed to find out why I wasn't getting short stories published. Ah, I said. If only I could get my hands on what the slush editors read. A few days later, Clarkesworld sent out a call for slush editors. I like them well enough and they get a lot of awards, but I thought it would be too much work.

Then I saw a call for Apex slush editors, and I took the morning off to reread what they had online.

I picked up an issue shortly after they first started, in 2006-2007 or so, and sent in for a subscription. Dark and creepy tales, ghost stories for grownups. I like ghost stories. The other magazine I was reading at the time was Weird Tales, which should tell you about my tastes, but they were doing more cthulu knockoffs than I could take (jaded much?). At the time, I decided that I could write better than everyone I read in Apex, so there. Only I couldn't. Stupidly, I quit reading short stories for a long time (out of spite) and gave away all my back issues.

Fast forward to the present day. I'd started reading Apex again; it was a) online, b) free, and c) full of stories that I wished I was good enough to write.

I begged, I pleaded, and I got the job a week ago. Somewhere between three and five stories go through my inbox a day.

Here are a few of the things I've learned so far:

A form rejection can mean any one of a number of things, like "You didn't follow the formatting guidelines" or "You went over the specified word count" or "This isn't what we publish."

So far, I've been reading everything I receive, all the way through.

I haven't seen ONE submission that wasn't formatted correctly (standard MS format) that I've been even remotely tempted to send forward. I'm sure I will eventually, but the odds aren't good.

Likewise, manuscripts with typos are also the ones with sloppy plotting. It isn't that a typo will kill you; it's that a lack of professionalism seems to repeat itself on all levels.

I see a lot of stories that are limited somehow, so that you can read the first paragraph (in some cases, just the title) and know how it's going to come out. Some are bad puns. Some are simple reversals of a common idea. Some are just a common idea, like "bad things happen to xxx kind of people." I'm not truly solid on why this is, but it seems like there's some idea that the story is about, and that's it.

Nothing happens organically, but only in service to said idea, which is black and white. Well, this is a magazine about wonder and mystery (dark miracles?), which are not produced in said pure colors, for the most part.

Those stories aside, I see a lot of passable stories. I'm not supposed to pass them on to the editor unless they're outstanding, exceptional.

I hang on to the ones I like for a few days. If, when I'm reading the rest of the stories, I look at that e-mail and find myself reluctant to send out a rejection on it, because I've been thinking or dreaming about it, I'll send it on, because it moved me the way the stories in the magazine move me.

Whether or not that means I'm sending up the right stories for the magazine has yet to be determined.

Here's who gets the non-form letters: new writers (if I can think of anything useful to say); the one rewrite request I asked for, because I couldn't get the story out of my head but yelled out loud with disappointment when I read the ending; when I feel like I have something useful to say (not often, oddly).

The passable stories and the stories that belong at other magazines don't usually get any comments. The badly formatted stories get a link to the guidelines Apex uses (although I think I've forgotten to delete this on a few properly formatted stories...oops).

A well-written voice will hook me faster than anything else, even faster than action action action! The stories where I settle in comfortably, reading every line instead of skipping past the description--it's because of the voice.

I've sent three stories up (they know who they are) and have two more in the bucket to see if I continue to like them as much as I do. I think that's my favorite part so far, going back over the stories that I like, running my tongue over them (not LITERALLY, ow). Yes, that's it, a good one. Like a vampire, selecting prey :)