Steven Lyle Jordan's Blog, page 53

February 5, 2014

Consider generating your own power

Most people who set up “grid-tied” energy systems for their homes—solar cells and wind generators, mostly—think of the excess energy that they pump back into the grid as pay-back to the utilities, to offset their own energy costs and save them money. But it’s more than that. Grid-tied systems help support the energy grid during stress or peak load periods, often keeping them from failing.

Most people who set up “grid-tied” energy systems for their homes—solar cells and wind generators, mostly—think of the excess energy that they pump back into the grid as pay-back to the utilities, to offset their own energy costs and save them money. But it’s more than that. Grid-tied systems help support the energy grid during stress or peak load periods, often keeping them from failing.

An Earth Techling article describes the current Australian heatwave, which is greatly taxing the power grid in order to keep up with energy demand. The article highlights homes with their own solar cell rooftops, which feed their excess energy back into the grid during these peak-stress periods, and thereby take some of the load off of the struggling network.

The same article points out a number of occasions, during this past January’s record cold spells in the U.S., when privately owned wind generators (windmills) generated enough excess power to dump back into the grid and bolster it during peak load periods of heating homes.

Peak demand periods, such as the dead of summer (or winter) are of great concern to utilities: They have to construct everything with an eye towards handling that load, even though that load is only present less than 5% of their online time. That means larger and more expensive systems. Still, they rarely design for the absolute worst loads, which means that rare 110 degree day might strain their systems beyond their capacity to handle.

Studies in Australia, where a great deal of the country’s power is generated by private residential systems, have shown clearly that the residential power pumped into the grid during peak demand periods helps to ease the demand on the utility networks, lessening the likelihood of a system failure. This means that private power systems not only provide power to their owner’s homes, but they help insure their neighbors’ power will stay up, too.

Considering today’s concerns in places like the U.S. that terrorists may strike at us through our power grids, it would seem to make sense for as many homeowners as possible to generate as much of their own power as they can… essentially decentralizing the power grid for security reasons. Not only would it save them money in the long run, but a loss of grid power would not be as catastrophic; private power sources could continue to provide minimal power until the mains were brought back online.

Also, centralized power systems so backed up do not have to build as heavily to manage peak demand times. That means less infrastructure at less cost, and lower bills to the consumer to support that infrastructure.

All future home construction in the U.S. should take this, essentially a safety and money-saving feature, into account; every roof that is replaced or repaired should be considered a potential place to put up solar cells, and every yard with enough clearance should be considered a place for a wind generator.

Some the planet… save money… save your neighbor. Is there a more noble set of goals?

February 2, 2014

Want the next newsletter?

I’ve released my first new newsletter in months. If you’d like to be on the receiving list of future newsletters, subscribe here.

This is updated from the newsletter I used to put out: Constructed by Mailchimp, it will have a much better structure, and include opt-out and automatic sign-up scripts. If you get it, please share it!

Want the new newsletter?

I’ll be putting out my first new newsletter in months, probably on Tuesday. If you’d like to be on the receiving list, email rbea@rightbrane.com with your email address, and I’ll add you to the list!

February 1, 2014

Will relaxed sex standards help SF on TV?

Over the years as television has sought new audiences (and revenue streams), some channels have relaxed the old standards for acceptable sexual content. Starting with the big pay-cable giants like HBO and Cinemax, siphoning down to pay-per-view and the other pay-cable offerings, and now some second-tier cable networks (like FX) have begun to show sexual and language content that used to be forbidden to TV viewers.

Over the years as television has sought new audiences (and revenue streams), some channels have relaxed the old standards for acceptable sexual content. Starting with the big pay-cable giants like HBO and Cinemax, siphoning down to pay-per-view and the other pay-cable offerings, and now some second-tier cable networks (like FX) have begun to show sexual and language content that used to be forbidden to TV viewers.

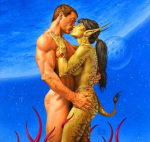

Could this trend be a help to science fiction content for television? Science fiction, in its regular depiction of aliens, future cultures and advanced technology, has had as a regular theme the exploration of alternative sexual practices, mores and inhuman biologies. In books, these depictions were publicly considered to be okay (if racy)… mainly because there were no pictures, and visual depictions of sex are usually the first thing to be censored by authorities.

Television and movies being a visual medium, therefore, it makes sense that sexual subjects would be in most cases edited away… or, if the story could not be told without them, the story would not be told. Which, when you think about it, is exactly the way television has treated all sex since its invention.

But now that standards are relaxing, and we’ve seen Dennis Franz’ butt on national airwaves (and much sexier butts since), sexual content, skin on skin action, non-heterosexual and even unorthodox sexual activities have become acceptable—usually with prior warning labels and suggestions to apply parental discretion.

Does this mean that the public is ready to see alien sex, with more than two sexes, different genital arrangements, unexpected copulatory methods, etc? With other aliens exclusively, it might come off as a sort of weird nature documentary… but how about when humans participate in there somewhere? Will seeing Kathy being impregnated through her nose, or Bob putting his hand into an alien’s sensory canal to induce orgasm, work for audiences?

Okay, maybe things don’t need to be so… extreme. But some SF stories feature unusual sexual arrangements. Would TV executives allow the depiction of sex with a man and three Venusians, with four different types of genitalia between them? Could audiences handle what would look like a woman being penetrated by the probosces of a giant insect? And would any possible squeamishness be risked by executives in order to put a particularly powerful program on?

Or would we just get Alien? Which, if you think about it, is about a creature that forcibly uses humans to gestate its offspring, killing the humans in the process… a particularly rough form and result of cross-species sex, if you will. Of course, the Alien movies are about the idea that this forced sexual contact is bad, and these creatures must be stopped. But suppose the humans lived through the process, and even enjoyed it… would we look at this series the same way? Would we allow it to be shown on TV?

Right now, we get the easy titillation of aliens who were essentially like humans, but with some sexual attribute that humans might find fascinating or attractive in real life (prehensile penises, forked tongues, multiple breasts, green skin, etc). But as time goes by, and TV execs get a bit more adventurous—probably just in an attempt to score fresh ratings wins, but still—we may see a day when the kind of sex that makes science fiction unique, makes its way to our televisions, opens us to new story experiences and gives us something really exotic to watch.

January 24, 2014

Writing as a process

Every so often, I come across an article in which a writer seems to lament some aspect of novel writing that troubles them: How do you create this kind of character? How do you world-build? Why is writing a good ending so hard?

Every so often, I come across an article in which a writer seems to lament some aspect of novel writing that troubles them: How do you create this kind of character? How do you world-build? Why is writing a good ending so hard?

This always strikes me as strange, because I imagine any person who tries to write must have done a fair amount of reading and writing as they grew up… probably in school. And I immediately think: Didn’t any of that reading and writing sink in?

Everything I learned about writing came from two specific things: Reading other books; and writing assignments in school. Reading other books (probably thousands of them) taught me story structure, character building, world building, fitting words and style to moment, plots, twists, emoting and description.

Writing assignments taught me how to plan, outline, gather and organize data, decide on an appropriate structure, select my story’s beginning, edit out extraneous material, and wind down my story quickly after the climax. I also learned about sentence structure, grammar, spelling and the literary licenses of storytelling and of certain genres.

Armed with those two sets of skills, I write. And I don’t have a lot of trouble doing it. Sure, I don’t have tight deadlines bearing down on me, which takes a lot of the pressure off. (Writing quickly was also something I learned in school, but I try to conveniently forget that particular lesson.) But once I start the process, developing the aspects of the story into a tight outline, I generally find that I can write like the wind once I have my bits and pieces together.

The use of the word process is important to how I see writing. Some writers would have you believe there’s something magic and transcendental about creating stories out of words. I disagree. Really, we all learn how to tell stories; it’s part of being able to communicate with others. Writing is just a process of combining our natural storytelling skills with the mechanics of turning those stories into words on a page (or screen)… mechanics that we are exposed to in others’ works, and which we practice to do ourselves as we grow and mature.

My process has certain steps that I use to assemble my material and record my story. My process takes from the material I’ve read and the storytelling tricks I’ve learned, and the writing skills I’ve developed through practice, to assemble my pieces and put them down for others to read. And every other writer’s process may be subtly or wildly different… but they all have one.

My feeling is: If you are a writer, and some part of the writing process gives you trouble, you probably need to revise your process; possibly to change the manner in which you break your story down, or build character details, or assemble your story threads, or decide upon your voice. For me, working out the details on my process allows me to work on a book over any period of time, in different working conditions, with any breaks or vacations worked in as required, and still have no trouble creating the finished product.

So get the process down. Everything after that should be cake.

January 20, 2014

King’s dream, not reflected in the stars

On Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, It’s natural to reflect on how his message has affected relations in the U.S., and not just racial; King believed in trust and brotherhood among all groups and nationalities, and saw that only that total trust and brotherhood would allow us to grow and prosper. We’ve made a lot of strides since then, though we clearly have a long way to go in others.

On Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, It’s natural to reflect on how his message has affected relations in the U.S., and not just racial; King believed in trust and brotherhood among all groups and nationalities, and saw that only that total trust and brotherhood would allow us to grow and prosper. We’ve made a lot of strides since then, though we clearly have a long way to go in others.

However, I find myself looking even further afield than that, and reflecting on how King’s message had impacted science fiction over the years. I have to say that, with some notable exceptions, I don’t think King’s message is reaching to the stars in our science fiction (or fantasy).

At the moment, the most popular SF and fantasy material is all about conflict: Star wars, alien or rival invasions, versions of the Crusades, etc, far outnumber SF about discovery or exploration. A great deal of fantasy is either devoted to wars between kingdoms or repelling great, evil (and usually ugly) forces, or stories of forbidden love, usually love between species, which tends to bring its own conflicts among the species opposing the couple.

Violence. Conflict. Race (or species) hatred. These are the present hallmarks of SF and fantasy. And sure, there are exceptions, usually in the form of the single non-human creature that willingly tags along with the humans… the Spocks and Chewbaccas of the genres. Or the series about groups of various races who have learned to work together, as depicted on shows like Farscape or Star Trek. But these are the exceptions that prove the rule, as these isolated groups band together to resist the single-minded forces of other races (most of which show no racial or species diversity of their own… oh, you hadn’t noticed?), fighting desperately to control their own areas and forcibly remove or wipe out any other aliens in the area.

In SF, we’ve gotten really good at throwing almost every color of the melting pot at our stories, doing our best to make ourselves look progressive and egalitarian. But it seems that, once we’ve seeded our main characters with Africans, Asians, Moors, Mexicans, Aleutians and Celts, we forget that the idea of race can extend to the other planets we aspire to visit as well.

In most SF, aliens are still depicted as mysterious and ultimately untrustworthy, outsiders, prone to animosity and violence… exactly the way we used to depict terrestrial races. In fact, the lone “exception” is often placed in the story in order to have someone conveniently around to tell the humans why they should be careful around others of their species, or why they react so badly to tribbles or the color orange or B-flat. The “exception” is also presented as the Enlightened One, the only member of their species who has risen above those issues and can play nice with humans (and as the tribble reference suggests, Star Trek‘s Worf is the perfect example of such a character).

But more often, conflicts involve entire races/species… and since war over resources rarely applies in SF, the driving forces are more often pure racial hatred, sometimes driven by an initial misunderstanding, but never resolved, never even an attempt at resolving the conflict. Race warfare with the ultimate desire for complete genocide.

So, it seems peace and brotherhood don’t extend much further than this planet… or, for that matter, much beyond certain countries on this planet. Which makes it doubly a shame that King didn’t survive to today, because it’s clear we still need a voice like his to inspire us to better relations and understanding with our brothers and sisters… both here, and in our future.

January 16, 2014

After WHAT fall?

I recently heard about a solicitation to submit short stories for an anthology based on the concept “after the fall of technology.” I was included in the solicitation, so I gave it some thought. Eventually, I decided: What fall of technology?

I recently heard about a solicitation to submit short stories for an anthology based on the concept “after the fall of technology.” I was included in the solicitation, so I gave it some thought. Eventually, I decided: What fall of technology?

Yeah, I just can’t see it happening at all, much less in some form analogous to our so-called “Dark Ages,” as most people imagine such a scenario. For one thing, those “Dark Ages” weren’t so dark as some would have us think; and for another, the world is so vastly different now than during that Dark Age, that it is virtually impossible to “fall” so far now as we did then.

The Dark Ages are primarily known for their lack of innovation and minimal spread of education. This was a period just after the end of the Little Ice Age, which had dealt European civilization a serious blow, and they were still in the process of picking up the pieces; life was still mostly about day-to-day survival. There seemed to be no room for science and education during that period.

But that is an untruth. Science and education went on, even in the Dark Ages: In Europe, most of it was related to agriculture and animal husbandry, in order to support their primary activity of the day (and to the tools of war, to support the secondary activity of the day). What we consider “simple peasants” today were actually shrewd farmers and tenders of livestock, and as they domesticated and selectively bred animals like dogs into varied companions and assistants, became very shrewd hunters as well.

But that is an untruth. Science and education went on, even in the Dark Ages: In Europe, most of it was related to agriculture and animal husbandry, in order to support their primary activity of the day (and to the tools of war, to support the secondary activity of the day). What we consider “simple peasants” today were actually shrewd farmers and tenders of livestock, and as they domesticated and selectively bred animals like dogs into varied companions and assistants, became very shrewd hunters as well.

And during this time, a select few scientists were advancing knowledge in other areas, less immediately practical, but useful as forming the groundwork for research and development that would come later, when resources were better suited. This knowledge continued to accumulate and be recorded, until relative peace came to Europe and time and resources could be diverted away from war and towards social improvement.

Now, this is important: All of the above applies to Europe only. While Europe was having its “Dark Age,” the Chinese empire was flourishing, growing and developing at a rapid pace. Its knowledge in many areas surpassed that of the West, though there were areas where the knowledge of both supplanted that of the other. Egypt had, centuries earlier, surpassed them both, and only the damage done by the desertification of North Africa laying waste to the Egyptian empire before Europe’s Dark Age prevented them from being the likely technological masters of the West at the end of Europe’s Dark Age.

And lest we forget, there was already an empire in Central and South America, and a thriving pre-industrial culture in North America (whose extents we are only now beginning to decipher). All of these cultures were technologically accomplished in one area or another, almost all of them in the areas of agriculture, social engineering, animal husbandry, textiles and basic pottery and metallurgy. These regions could have continued to expand and thrive technically, and would have in most cases, if national competition or other environmental factors had not brought them down.

The European “Dark Ages” were only dark in Europe. The rest of the world was advancing and developing just fine. Yes, Europe recovered, and thanks to their own accumulation of knowledge and theory in store for better times, arguably managed to speed up the process of industrialization that further accelerated scientific knowledge; but that’s no reason to assume that advancement had died during their absence, nor would not have continued without their help.

One of the reasons for this limited view of history is the relative isolation and perceived superiority of the regions described above. Europe didn’t know what China was doing, any more than China knew what Central America was doing, or Central America knew what Egypt was doing… and all of them just assumed they were the most advanced place in the world, with nothing to learn from others. They were growing and developing in relative isolation, so some regions concentrated on different technological areas, and as a result, knowledge of a particular field was stronger in certain regions than others. When they all began to meet, trade and collaborate (or compete), knowledge became more evenly dispersed between them… or, as an empire succumbed to another, some specialized knowledge was lost.

But eventually, we came upon a point in history when, thanks to worldwide communications and trade, the entire world shares the same knowledge. We have spread to the far corners of the world, mass occupying every continent save one, and sharing resources, manufacturing and trade worldwide. And that’s where we find ourselves today.

Now, imagine a catastrophe, as large or small as you’d like. Imagine a small or large proportion of humanity was impacted by the catastrophe, maybe even wiped out. But this is a world in which we have people, knowledge and a viable manufacturing base in every corner of the world except Antarctica. Even if we nuked the crap out of the northern hemisphere, there are still billions of people in the southern hemisphere to pick up where the northern left off. Floods could wipe out huge swaths of coastal lands, and still leave billions of people at higher elevations behind.

If Chile, for example, needed information or products that it used to get from Germany—but because of some disaster, it couldn’t now—it has the same knowledge and manufacturing capability to make that product or divine that information itself. It has the resources to maintain its equipment, and to make new tools to support that maintenance. It can teach itself how to take on duties formerly done by others in foreign lands.

In fact, there is little that one nation can do that another couldn’t learn and take over. If, in the worst of disasters, certain highly specialized tools or energy sources became impossible to get, some areas of technology might have to scale back or go into effective hibernation until the infrastructure can be replaced. But we could still accomplish a lot with what we had left.

Even individual creators, mechanics and craftsmen now have the capability of fabricating almost anything in their garage, thanks to modern tools, including the latest lathes, 3D printers and molding technology, capable of creating the most intricate productions barely imaginable just a decade ago.

The more likely scenario, in a major disaster, would be people either traveling to the location of the disaster once it was over, to see if there was anything to recover (or take over) in that area; or, if it was too far gone, they would alter trade patterns to accommodate the loss of a major player or region and move on.

So, you see, it is highly unlikely that we would or could ever suffer a “fall of technology”; it’s a concept based on a myth. A disaster, even a worldwide one, might do a great deal of damage to civilization… or it might effectively wipe us off the face of the Earth, and it really wouldn’t matter much at that point.

But as long as there are a few makers left… a few people with fabricating tools, a power source and the knowledge to use them… humans will build, rebuild, and continue to advance. Technology would not fall; at worst, it would retool.

January 15, 2014

What you need to know about the court decision that just struck down net neutrality

The principle behind the phrase "net neutrality" is that internet service providers of all kinds should treat data flowing over the open internet equally, without giving preferential treatment to data from one provider or platform. On Tuesday, however, the Federal Communications Commission's rules governing that kind of behavior were struck down by an appeals court in Washington, D.C. -- as…

This could be the beginning of the end for web fair access.

Book reupholstery needed

A new publishing contact mentioned to me recently that he thought my novel covers should be redone; he told me that they were okay, technically, but they weren’t great novel sellers.

A new publishing contact mentioned to me recently that he thought my novel covers should be redone; he told me that they were okay, technically, but they weren’t great novel sellers.

I couldn’t argue with him… it’s not like my novels are flying off the (digital) shelves, after all. I’ve gotten some decent ratings from my books, but never compliments on my covers… and very few sales overall. I have to consider that the quality of my covers may be a major stumbling block in selling my work.

Novel cover art is the first thing readers see… it is the upholstery that presents your novel to their eyes, and it must look good to be noticed among the walls of books alongside it. Cover art can be a funny thing; there are a lot of things to consider. It’s not enough to be proficient in Photoshop (which I am… well, as they say, just proficient enough to be dangerous), you need to consider whether your art fits the genre and style that fans are attracted to. And these days, your book art may only be seen as a thumbnail image on a computer screen or cellphone, so it has to look good at almost the size of a screen icon.

All of that can be tricky to pull off, and I’ve seen my share of covers that did it badly. I’ve tried to apply my skills to the challenge, and since my books are 100% ebooks, I’ve sided with the “good looking thumbnail” strategy. I’ve occasionally posted my upcoming covers on Facebook, and they are all up on Pinterest, to let people see what I had to offer. And on one occasion, I entered the cover of Sarcology in a contest and won an award from The Book Designer, a website that specializes in self-publishing and ebook design.

But that was probably the only affirmation that I ever received from my covers. At the same time, no one ever told me they were no good… and maybe that’s where my peer review strategy failed. I suppose I can no longer assume that no news is good news.

I’m going to have to set up a better set of art reviewers, and use them methodically, something I’ve never really done before. I put considerable effort into my books… I don’t want an unappealing cover to turn them away before they give my work a chance.

And I may have to try to figure out a way to get some professional artists involved in the process—yeah, talking about pay. I’ve always been proud of my ability to create ALL of my book, from start to finish; but I may have to consider passing on the creation of cover art to those better suited at it than I.

But for now, I’m going to start a process of reviewing and redoing every book cover I can, and try to do a much better job at design than I have in the past. I’ll build my reviewers, toss concepts around, and try to get a better perspective on my own work. Hopefully, all of this will result in improved sales and popularity.

At any rate, it sure can’t hurt.

(If you’re interested, feel free to peruse the covers and weigh in here on what you do and don’t like about them. I’m not afraid of criticism, so be honest; how else am I going to improve?)

January 10, 2014

Her: Guess who’s plugged in to dinner?

[image error]Her, Spike Jonze’s new movie, is at once unique… and not. Which seems to be an odd thing to say regarding a movie about a man who falls in love with his computer. But the seemingly strange relationship is not nearly as original as it might seem. Because, if you think about it, you’ll realize that movies, books, plays and who knows how many other forms of media have gotten a lot of mileage out of portraying the unlikely couple, the kids from opposite sides of the tracks: The Black man and the White woman; the Bronx kid and the Puerto Rican immigrant; the poor American artist and the rich French girl; the Beauty and the Beast; the Princess and the Vagabond; the King and the Teacher; even the girl and the robot servant (yes, Bicentennial Man, the only movie in this list that, I hope, needs direct referencing; as well as my own novel, Sarcology). So, the guy and the computer shouldn’t seem like that much of a stretch after all.

It seems to be part of human nature for like-minded people to draw together, and to distrust or shun those outside of their established social group. This extends to relationships, and creates schisms between people of different groups that want to come together. Some of our greatest myths and stories have come from couples that, despite incredible pressure from their peers to shun or even kill each other, resist the social pressures and prevail in love; and some of our most painful stories have come from those whose love could not overcome those pressures. There’s a reason Romeo and Juliet, and for that matter, West Side Story, aren’t known just for their balcony scenes.

But stories like these, and like Her, are good reminders for us that we, whether Black or White or Brown or Yellow, Jewish or Muslim, young or old, beauty or beast, American or European, rich or poor, aren’t as different as we may think we are. We often see each other through the colored glasses of distrust, ignorance or fear; these stories show us how to remove those glasses and extend our hands, to show the best of ourselves in being willing to offer our trust, to set aside our fears and prejudices, and let new people into our worlds. They also teach us to refrain from judging others who are not like us, who have a different perspective or point of view, and who may be open to happiness from sources we would not have considered.

I don’t know if this particular movie will have the enduring strength of a West Side Story or a Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? But there’s no reason it shouldn’t. As we come ever so much closer to creating truly intelligent computer systems, and begin to break down the walls surrounding the concepts of machine consciousness, human emotions and drives, it should come as no surprise that we would soon be looking at the possibilities of a true human-computer relationship. The relationship in Her is admittedly stranger than most, if only because there is no real physical form for the computer to take… but as so many delight in pointing out, love is more than a physical relationship; so why not this?

It’s still too early to tell what kind of relationships we’ll have with our computers in the long run—tools, acquaintances, partners, friends, servants, masters or pets—but Her will serve as good as any other jumping off point to begin to figure it out.