Steven Lyle Jordan's Blog, page 50

March 29, 2014

Proposed new cover for Kestral III

This is the first new design proposal for the third Kestral novel, The House of Jacquarelle. Any opinions out there?

This is the first new design proposal for the third Kestral novel, The House of Jacquarelle. Any opinions out there?

I’ll be spending time on an editing pass through the novel before I re-release it, so there’s time to mess with this design, or try a few other variations. This design is similar to the first cover design, which featured Kestral and Mark O’Bannon in the literal crosshairs of an unknown assailant, and the Jacquarelle Mansion behind them. This time, I used my recently-discovered model for Kestral, a new building for the mansion, the new book layout, and a judicious use of Photoshop.

Do you think it works? Does it catch the eye? Does it look exciting… or cheesy? Let me know what you think.

March 26, 2014

Lost: Complement to The Prisoner

Lost. Perhaps a more polarizing television show hasn’t existed since the 1960s. The series about the fate of the passengers of Oceanic Flight 815 was fascinating and maddening at the same time… often to the same viewers at the same time. It weaved a strange story about a strange island that tormented its occupants, and ended on a bittersweet note that left the viewer wondering exactly how long they had been watching a bunch of dead men walking.

Lost. Perhaps a more polarizing television show hasn’t existed since the 1960s. The series about the fate of the passengers of Oceanic Flight 815 was fascinating and maddening at the same time… often to the same viewers at the same time. It weaved a strange story about a strange island that tormented its occupants, and ended on a bittersweet note that left the viewer wondering exactly how long they had been watching a bunch of dead men walking.

But Lost had most viewers fooled, for it was never a show about its plot. Lost was a show about personal journeys and life-affirming moments. It taught us about what motivates people, as individuals and as groups, in a world that is no more comprehensible than it is controllable.

And in this way, it provides a bookend to a 1960s TV show that equally fascinated and maddened audiences, that gave viewers an ending that really wasn’t, while presenting revelations about the main character that were really comments about ourselves: The Prisoner.

Stop and read comments by TV viewers about the original The Prisoner (yes, we’re ignoring that more recent fiasco by the same name) and Lost, and you start to find many parallels. In both series, the actual story—the overall plot that carried the viewer from episode to episode—was thin. And at times, patently ridiculous. At best, the episodes had an allegorical point to them (more in The Prisoner than in Lost), but they often presented as many questions as they answered. The characters, as well, tended to be types, not so much well-developed individuals, and fairly single-minded in their desire to reach their own personal goals.

Stop and read comments by TV viewers about the original The Prisoner (yes, we’re ignoring that more recent fiasco by the same name) and Lost, and you start to find many parallels. In both series, the actual story—the overall plot that carried the viewer from episode to episode—was thin. And at times, patently ridiculous. At best, the episodes had an allegorical point to them (more in The Prisoner than in Lost), but they often presented as many questions as they answered. The characters, as well, tended to be types, not so much well-developed individuals, and fairly single-minded in their desire to reach their own personal goals.

In both series, audiences demanded answers at the end; and in most cases, audiences weren’t satisfied with the answers they received. To be sure, both series ended on notes that were very Twilight-Zone-ish in their tone and delivery, and resulted in lively debates as to the meaning of the endings.

In The Prisoner‘s case, the ending presented the audience with the truth that they, themselves, are the ultimate controller of their own lives… and that the Village is the World in microcosm, their world, in which they will never truly escape. Lost had a similar message, but took it a step further in saying that you will continue along your path, chosen or given, until you die… possibly sooner than you expect.

In both cases, the point to the series wasn’t the stories; it was the people. The Prisoner was one man adamant about maintaining his own sense of self-worth and independence against a world working hard to reduce him to the status of non-entity among non-entities. His battle against a ruthless authority determined to render him meaningless, and a population who had swallowed the kool-aid and continually tried to coerce him into falling in step with them, was nothing short of an epic struggle.

Lost, in contrast, gave us many character arcs, and each one gave us something different. But in most cases, those arcs were presented as a series of defining moments, events that shaped the character’s personalities, and specifically dictated their reactions to the events happening around them on the island. The arcs of individuals worked in aggregate to describe a mini-society of people, thrown together and left to their own devices to navigate a world not of their making, that often made no sense except what they could tease out of it.

The Prisoner‘s battle was emblematic of the late 1960s: The idea that a monolithic Society was so busy trying to make everyone conform, mostly for the benefit of some uber-organization (like a government, a religion or a conglomeration), that it was killing the individual’s spirit. Many a viewer (like myself) took away the message that individuality is all that is important, and that society is designed to serve individuals… not the other way around. Viewers also learned that ultimately there was no escape from that society; only a continuation of the struggle to be recognized within it. In the end, the character named Number 6 was alone, as he was in the beginning.

Lost did not recognize a coherent, monolithic Society; it registered life as Chaos Incarnate, a largely (and ultimately) pointless exercise in survival. Lost taught viewers that life was more likely to simply grind you under its impartial wheels if you stood by and let it, and even if you didn’t… and it was up to you to find and cultivate the allies you needed to circumvent the dangers intact. Lost was about understanding and accepting the different people around you, finding a common ground for cooperation, and tackling unpredictable life arm-in-arm with allies. At the end of Lost, the characters were reunited, their journey over at last.

It is mainly the people who never caught on to the real messages of these shows who criticize them today. For those of us who got the messages, it’s interesting that the two shows share so many similarities, yet deliver such opposing messages about individuals in society. It forces the viewer to wonder if the world has changed so much that, where individuality was once the most important thing to cherish, now your place in community against the irrational mysteries of the world is paramount.

As time goes on, I expect these shows to become interlinked in popular lore, shows that complement each other in their lessons of our place in the world. And what will be really interesting is the show, some time in our future, that will teach us the next lessons about our place in the ever-changing world… just imagine how fascinating and maddening that show will be.

March 24, 2014

Conventions and “slut-shaming”

This IO9 article has recently resurfaced, and since I’m preparing to re-enter the world of conventions soon, I thought it was worth bringing up: Author Emily Finke describes the disagreeable treatment she received at a Balticon, when she cosplayed in a costume from Star Trek and became the brunt of women trying to shame her for wearing such a short skirt, and men trying to show up her Star Trek geek cred. Her understandable rant takes those fanboys and girls to task for such sorry behavior.

This IO9 article has recently resurfaced, and since I’m preparing to re-enter the world of conventions soon, I thought it was worth bringing up: Author Emily Finke describes the disagreeable treatment she received at a Balticon, when she cosplayed in a costume from Star Trek and became the brunt of women trying to shame her for wearing such a short skirt, and men trying to show up her Star Trek geek cred. Her understandable rant takes those fanboys and girls to task for such sorry behavior.

A truckload of comments have been applied to this post, and about the only way I can sum them up is to say that they are either a variation of “You Go Girl!” or “What did you expect, wearing a sexy outfit like that?” And it immediately reminded me of a post of mine from a while back, mentioning the latest French law that finally took off the books the requirement for women to wear skirts in public.

Why? Because at issue in both cases is the fact that people (not just women, of course) have the right to wear whatever they want, including clothing that makes a statement about them that they want to make. It is a matter of personal choice, and assuming that local culture won’t get you arrested for doing it (or you’re willing to risk it)… go ahead and do it. Emily wore her outfit, which (let’s face it) wasn’t scandalous when it was presented in 1966, much less today. She made a personal statement that she liked classic Star Trek and wanted to look the part, and it should have ended there.

Unfortunately, people are people, and as such, many are prone to little things like jealousy, distrust, sexual stimulation or simple misunderstanding… and attractive girls in sexy outfits have, throughout history, been known to attract both wanted and unwanted attention. It truly sucks that some people see attractive women as “sluts,” or that others become so physically uncomfortable around them that they don’t know how to act (and we could spend a week on all of the other types of people whom some people react adversely to). But these people do unfortunately exist, including in sci-fi and fantasy circles, and even Emily needs to accept that they are out there, and likely to do or say something stupid in response to her outfit.

Unfortunately, people are people, and as such, many are prone to little things like jealousy, distrust, sexual stimulation or simple misunderstanding… and attractive girls in sexy outfits have, throughout history, been known to attract both wanted and unwanted attention. It truly sucks that some people see attractive women as “sluts,” or that others become so physically uncomfortable around them that they don’t know how to act (and we could spend a week on all of the other types of people whom some people react adversely to). But these people do unfortunately exist, including in sci-fi and fantasy circles, and even Emily needs to accept that they are out there, and likely to do or say something stupid in response to her outfit.

Like the rest of us, Emily can only hope that someone else will mitigate any inappropriate behavior directed her way. Apparently at Balticon, such people were in short supply that year. But I would like to think that at Awesome Con, a convention that features a lot of comic book creators, fans and cosplay, that bad behavior will be much less tolerated in the midst of such a diverse audience.

And this is a sci fi, fantasy and comics convention, for pity’s sake; people go there to have fun. Unlike my article about workplace fashion, people are free to dress as they like, because there is no reason to downplay the differences or attractions of the sexes in a lighthearted convention atmosphere—especially one whose themes regularly include highlighting the differences and attractions of the sexes. Why anyone would go to such a place, then proceed to pick on someone who shares their interests—one of the few places where someone with those interests can put on a costume and not be laughed at over it—is beyond ludicrous.

And this is a sci fi, fantasy and comics convention, for pity’s sake; people go there to have fun. Unlike my article about workplace fashion, people are free to dress as they like, because there is no reason to downplay the differences or attractions of the sexes in a lighthearted convention atmosphere—especially one whose themes regularly include highlighting the differences and attractions of the sexes. Why anyone would go to such a place, then proceed to pick on someone who shares their interests—one of the few places where someone with those interests can put on a costume and not be laughed at over it—is beyond ludicrous.

So here’s hoping fans like Emily will feel free to dress up as they like; and that others will be able to compliment them on their costume, maybe ask polite questions about it, and even deliver a personal compliment, without crossing the line into creepiness or obnoxiousness.

March 21, 2014

Working Awesome Con

It’s official: I will be working at the upcoming Awesome Con, in Washington DC April 18-21, on two of the discussion panels. I’ve been asked to participate in a discussion on traditional vs self-publishing, and one on the philosophical subject: “Are Heroes Getting Smaller?”

It’s official: I will be working at the upcoming Awesome Con, in Washington DC April 18-21, on two of the discussion panels. I’ve been asked to participate in a discussion on traditional vs self-publishing, and one on the philosophical subject: “Are Heroes Getting Smaller?”

I was actually asked about a third panel which I had rather vaguely pitched, to discuss working real science ideas into modern science fiction… what I call futurist fiction. Unfortunately, they didn’t have anyone else to put on such a panel. So they offered to let me be a one-person panel!

I considered it; but my thought was, “Take an author no one knows and have him do a panel on what happens to be the most unpopular sub-genre of science fiction at the moment? It’ll be me and three guys, all taking a nap while they wait for the next scheduled act in that room!” I politely declined.

I’m looking forward to the panels I’ll be sitting in on, and any others I can check out… not to mention, visiting my first SF convention in years, something I plan to do more of in the future… and maybe to confer, converse, and otherwise hob-nob with my brother wizards… er, uh, fellow creators and artists, including a few famous faces from TV and movies, established and upcoming writers and comic artists, and even a former astronaut.

I’m looking forward to the panels I’ll be sitting in on, and any others I can check out… not to mention, visiting my first SF convention in years, something I plan to do more of in the future… and maybe to confer, converse, and otherwise hob-nob with my brother wizards… er, uh, fellow creators and artists, including a few famous faces from TV and movies, established and upcoming writers and comic artists, and even a former astronaut.

Mostly I feel the need to connect with more people in my chosen interest. My lack of regular connection to SF fans leaves me feeling… well, if not alone, let’s say… isolated. I need a reminder that there are more SF fans around than just me and one or two people I know.

And hopefully this will give me another promotional outlet as well, improving my chances of increasing my public profile and getting some sales action going… at the very least, giving me some added incentive to write another book!

So, if you manage to come, look for the publishing and heroes panels, stop by, and wave if you see me!

March 19, 2014

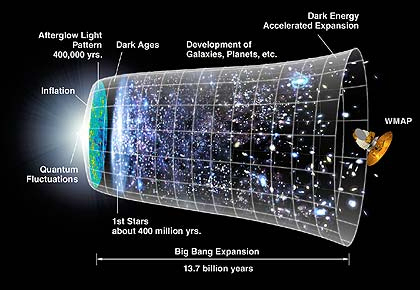

Proof of the Big Bang reinforces my own favorite theory

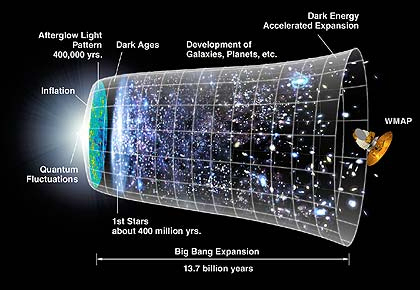

The monstrous news this week is about data from Harvard scientists that identified evidence of cosmic inflation right after the Big Bang. This is a Nobel Prize-level discovery, which reinforces the theory of the Big Bang and rules out the theory that our universe undergoes a regular Big Bang, Big Crunch, Big Bang creation loop.

The monstrous news this week is about data from Harvard scientists that identified evidence of cosmic inflation right after the Big Bang. This is a Nobel Prize-level discovery, which reinforces the theory of the Big Bang and rules out the theory that our universe undergoes a regular Big Bang, Big Crunch, Big Bang creation loop.

There are many layman’s descriptions of this phenomenon and its significance (this one from Gizmodo actually isn’t bad)… and make no mistake, it’s hugely significant as it reinforces one theory over another, and brings us that much closer to the moment of creation. However, even this finding does not answer two significant questions: What, exactly, caused the Big Bang; and what, exactly, was there before the Big Bang? Some scientists argue that, since the moment before the Big Bang would not be anything observable, it just doesn’t matter; only the result is important.

Others still want more than that, understandably… I, in particular, would love to know what there was before the Big Bang, and what caused the Bang in the first place.

I have a theory.

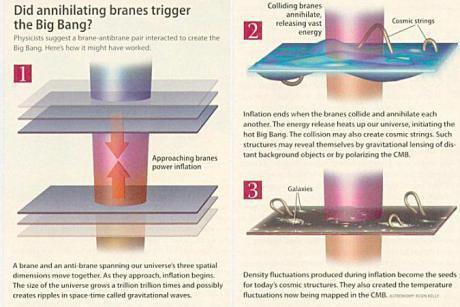

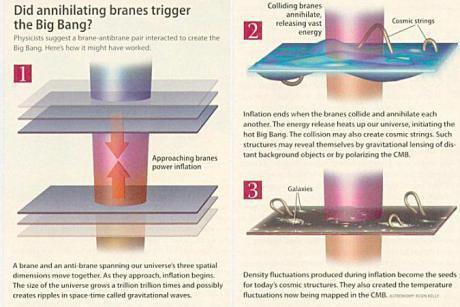

Some scientists believe that our universe is one of many universes, separated from each other by a unique “frequency” inherent to that universe. Much like parallel sheets of paper separated by space, not touching, these universes exist parallel to each other, not touching, by virtue of their different frequencies keeping them apart. These universes are called “branes,” or membranes, each one as real and viable as the next.

Multiple universes–branes–each existing parallel to each other, separated by a unique “frequency.”

Some scientists theorize that over time these branes’ frequencies change, which causes them to move in relation to each other: The closer to the same frequency, the closer branes will be to each other. Occasionally (eventually?) two branes’ frequencies become identical and they come together, powerfully combining their fundamental elements and energies into one. This essentially annihilates the two branes and creates a new brane, and all of those fundamental elements from two branes are injected into the one new brane through a burst of energy emanating at a single point in the new brane, creating a (…wait for it…) Big Bang.

An illustration of brane/universes coming together to create new branes.

Sooner or later, our brane, once created by the merging of two older branes, will itself merge with another brane, and the resultant collision will annihilate our two branes and create a single brand new one. Maybe the end result of all this merging will be one final brane, the final universe of all the universes. Or, maybe, the brane we live in is the last one…

Obviously, I have no physics to back this up. No one does. We just have further proof of the Big Bang that would have resulted from the events of my theory. On the other hand, no one can contradict it yet, either… how cool is that?

By the way (of a shameless plug), this is the same theory I made reference to in the second Kestral novel, The Lens: The Brane Spray Symphony that is the reward (and punishment) of a bet between Mark and Sarander is supposed to be a days-long Fantasia-like artistic recreation of the beginning of the universe, starting with the moment when two branes finally meet and the resultant ejecta create our universe, in an effect quite similar to a (…wait for it…) Big Bang.

By the way (of a shameless plug), this is the same theory I made reference to in the second Kestral novel, The Lens: The Brane Spray Symphony that is the reward (and punishment) of a bet between Mark and Sarander is supposed to be a days-long Fantasia-like artistic recreation of the beginning of the universe, starting with the moment when two branes finally meet and the resultant ejecta create our universe, in an effect quite similar to a (…wait for it…) Big Bang.

Proof of the Big Bang reinforces my own theory

The monstrous news this week is about data from Harvard scientists that identified evidence of cosmic inflation right after the Big Bang. This is a Nobel Prize-level discovery, which reinforces the theory of the Big Bang and rules out the theory that our universe undergoes a regular Big Bang, Big Crunch, Big Bang creation loop.

The monstrous news this week is about data from Harvard scientists that identified evidence of cosmic inflation right after the Big Bang. This is a Nobel Prize-level discovery, which reinforces the theory of the Big Bang and rules out the theory that our universe undergoes a regular Big Bang, Big Crunch, Big Bang creation loop.

There are many layman’s descriptions of this phenomenon and its significance (this one from Gizmodo actually isn’t bad)… and make no mistake, it’s hugely significant as it reinforces one theory over another, and brings us that much closer to the moment of creation. However, even this finding does not answer two significant questions: What, exactly, caused the Big Bang; and what, exactly, was there before the Big Bang? Some scientists argue that, since the moment before the Big Bang would not be anything observable, it just doesn’t matter; only the result is important.

Others still want more than that, understandably… I, in particular, would love to know what there was before the Big Bang, and what caused the Bang in the first place.

I have a theory.

Some scientists believe that our universe is one of many universes, separated from each other by a unique “frequency” inherent to that universe. Much like parallel sheets of paper separated by space, not touching, these universes exist parallel to each other, not touching, by virtue of their different frequencies keeping them apart. These universes are called “branes,” or membranes, each one as real and viable as the next.

Multiple universes–branes–each existing parallel to each other, separated by a unique “frequency.”

Some scientists theorize that over time these branes’ frequencies change, which causes them to move in relation to each other: The closer to the same frequency, the closer branes will be to each other. Occasionally (eventually?) two branes’ frequencies become identical and they come together, powerfully combining their fundamental elements and energies into one. This essentially annihilates the two branes and creates a new brane, and all of those fundamental elements from two branes are injected into the one new brane through a burst of energy emanating at a single point in the new brane, creating a (…wait for it…) Big Bang.

An illustration of brane/universes coming together to create new branes.

Sooner or later, our brane, once created by the merging of two older branes, will itself merge with another brane, and the resultant collision will annihilate our two branes and create a single brand new one. Maybe the end result of all this merging will be one final brane, the final universe of all the universes. Or, maybe, the brane we live in is the last one…

Obviously, I have no physics to back this up. No one does. We just have further proof of the Big Bang that would have resulted from the events of my theory. On the other hand, no one can contradict it yet, either… how cool is that?

By the way (of a shameless plug), this is the same theory I made reference to in the second Kestral novel, The Lens: The Brane Spray Symphony that is the reward (and punishment) of a bet between Mark and Sarander is supposed to be a days-long Fantasia-like artistic recreation of the beginning of the universe, starting with the moment when two branes finally meet and the resultant ejecta create our universe, in an effect quite similar to a (…wait for it…) Big Bang.

By the way (of a shameless plug), this is the same theory I made reference to in the second Kestral novel, The Lens: The Brane Spray Symphony that is the reward (and punishment) of a bet between Mark and Sarander is supposed to be a days-long Fantasia-like artistic recreation of the beginning of the universe, starting with the moment when two branes finally meet and the resultant ejecta create our universe, in an effect quite similar to a (…wait for it…) Big Bang.

March 16, 2014

The new class system

Author, agent and blogger Donald Maass has written a nice post about what he describes as the new class system in publishing that’s developed as the industry has moved forward. He does not see an industry of dinosaurs slowly being replaced by the plucky mammals gaining evolutionary dominance.

Author, agent and blogger Donald Maass has written a nice post about what he describes as the new class system in publishing that’s developed as the industry has moved forward. He does not see an industry of dinosaurs slowly being replaced by the plucky mammals gaining evolutionary dominance.

What’s happened instead is an evolution of the publishing world into a new class system, and like any class system it has winners, losers and opportunities. It’s a system that, if not recognized for what it is, will trap frustrated writers in a pit far more hopeless than the one they yearned to escape.

Maass breaks down the “classes” of authors into the very understandable “first class,” “coach” and “freight,” best defined by their status, quality and available opportunities in the publishing industry. He goes on to describe the limitations inherent in these classes, the obstacles faced by an author hoping to move up to the next level.

It has a lot of similarities to the description of the “publishing castle” that I’ve used for years, to illustrate a system where a publisher acts as final say over publishing—the king, as it were—and immediately circling this royalty of publishing control are the cherished favorites, the knights and other rich or popular royals, whose accomplishments are lionized by the royalty, and whose works are immediately recommended to a populace all but coerced into supporting the status quo.

Below them, but still in the castle, are lesser figures and talents who have managed to enter the castle under accomplishment, hook or crook; and having gained access, now enjoy some of the benefits of castle life. They often spend more time kow-tow-ing to the kings and royals than the amount of benefit they gain from the relationship; but it’s still better than being outside the castle, digging in the mud to support the king.

And therein do we find the bulk of the talent (or lack thereof), outside the castle and hoping to find a way in. Outside, life is tough, opportunities are scarce, and even the smart, strong or lucky can be cut down by unfortunate circumstances, or simply never given the opportunity to prove their worth. Though some may almost miraculously gain access, most will never enter the castle and gain its benefits, no matter what they do. Maybe a few will manage to leave their lot, and find another location where they can shine… but more likely, they’ll end up in the employ of another castle through which they are still denied entrance.

The choice of metaphors—Maass’ and mine—are clearly designed to suggest the hope/possibility of an eventual revolt of the system, a breakdown of the present feudal system and the subsequent installment of a new reality, a hopefully more equal state. Clearly this would please the many people on the outside looking in, and I freely confess to being one of those. (Of course, we all know that revolutions often result in new states as unequal as the previous state, just for different people.)

Being that Maass is an agent, I’m not sure how he really feels about the possibility or value of a revolution. All the same, I’d rather see the revolution come, as it’s my opinion that a shakeup couldn’t hurt.

March 15, 2014

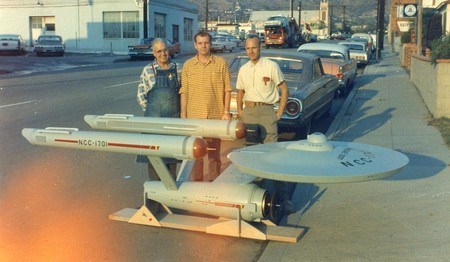

Homebuilt Enterprise!

Yeah, I know, I’m having a Trek-geek attack today, but I have to share the video of a private modelmaker recreating my personal favorite of all the Enterprise versions. This guy is my hero!

The one, the only, the original Enterprise

How cool is this? The original 1964 screen “hero” model of the USS Enterprise, built for Star Trek (TOS, of course).

Terraforming and genetic manipulation both.

(originally posted on SciFi Ideas) Science Fiction loves the idea of terraforming… rebuilding a planet or moon to be more hospitable for human habitation. A term and concept (also known as geo-engineering) at least as old as the 1940s, it has become even more popular today, and has leaked into TV shows like Star Trek: The Next Generation and Firefly, as writers begin to realize how easy it can be to impact a biosphere. (We greatly impact our own biosphere every day, applying a concept we generally call pollution.)

Science Fiction loves the idea of terraforming… rebuilding a planet or moon to be more hospitable for human habitation. A term and concept (also known as geo-engineering) at least as old as the 1940s, it has become even more popular today, and has leaked into TV shows like Star Trek: The Next Generation and Firefly, as writers begin to realize how easy it can be to impact a biosphere. (We greatly impact our own biosphere every day, applying a concept we generally call pollution.)

Of course, impacting it in a desirable way is still considered the concept’s major challenge, so writers often center their stories around the brilliant planetary engineers who slave over intense computations, debate and study the possible consequences, and ultimately, take an action (like dropping ice-asteroids into an atmosphere) and roll the dice.

It’s often assumed that a planet, given time and smart enough engineers, will eventually become another Earth. But that would seem like a very inefficient way to go about it. After all, the likelihood that we’ll find a planet that will give us a functional duplicate of Earth are pretty slim; and there must be many more planets out there that can be reshaped to some extent, but never quite equal the qualities of Earth. Is that, then, a reason not to reshape that planet… and possibly give up a lot of real estate, just because it’s not a duplicate of Earth? Is that a reason to limit your efforts to those incredibly few planets you’re likely to find that can be duplicate Earths?

I’d say No to both questions. Because, fortunately, science fiction has also discovered the concept of biologic engineering… the idea of making biological changes to the human body, possibly right down to the genetic level, presumably to improve its capabilities and/or survivability. It hasn’t been done much in SF (in TV and movies, at least), but the combination of geo-engineering and biologic engineering open up a much larger possibility of creating human-habitable planets than does geo-engineering alone. It’s sort of like a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup: Two great concepts that work great together.

(Cue commercial: “Hey, you got your geo-engineering on my biologic augmentation!” “Say, you got biologic augmentation all over my geo-engineering!” “HEY!…”)

Suppose, for instance, that you have a planet that is noticeably larger than Earth. You can terraform it to be like Earth, but the planet has a much stronger gravity well because of its larger size… and I seriously doubt geoengineers would be able to do anything about that.

The solution: Biologically engineer your population to be able to withstand stronger gravity, with more robust skeletal structures, muscles and organs. Presto: Your not-quite-Earth is now perfectly habitable for the genetically-modified population.

Or suppose your not-quite-Earth had a much lower gravity, resulting in a lot of rocky terrain and ridiculous mountains in the way? Well, maybe now’s the time to biologically engineer people with hollow bones and feathers on their arms and legs, and let them fly around instead of walking on the difficult terrain.

Or how about a planet very heavy in a toxic metal? Perhaps the colonists could be engineered with particular compounds in their bodies that helped to counteract that metal, or even use it as another source of nourishment.

So, imagine a lot of planets capable of being geo-engineered to within tolerable specs of Earth. When combined with biologic engineering, the result is a number of “races” of humans, all constructed around the standard, “baseline” human, but augmented to fit their chosen environment.

One of the pluses of this arrangement is that, since all of the “races” are offshoots of humans, they are more likely to be able to share: Their joint history means shared cultural references and languages; their shared biology means they all have roughly the same senses and vocal cords for communication; they can tolerate most of the same foods, breathe the same air, etc, with possibly only minor steps taken to provide a requirement or screen a particular element when they travel to other worlds.

One of the minuses is that, if the biologists aren’t careful and take their augmentations too far, these differences could turn out to be so extreme that your population may not be able to visit other Earth-like planets without significant life-support gear. And suppose you’re born on Earth-Analogue 12, and want to permanently relocate to Earth-Analogue 49? There may be a limit to how much biologic engineering (or re-engineering) can be done to adapt you to another planet. You may need life-support gear to live on that planet for the rest of your days.

Still, this is a much more realistic and practical situation than the old SF standby of unrelated aliens that all approximate humans, can all hang together, speak English and even, to some extent, procreate… something that works great on TV and movies where creature budgets may be limited, but highly unrealistic and unlikely… and assuming there are aliens out there to hang with, for that matter.

Perhaps, as SF in TV and movies mature and move past the tropes of the 20th century, we’ll see more of these scenarios… and a much more likely future.

(Steven Lyle Jordan is a futurist and author who has used the combination of geo-engineering and biologic manipulation in his novel series The Kestral Voyages, and has further plans for it down the line.)