C. Aubrey Hall's Blog, page 40

September 15, 2011

Being Tough; Being Kind

One of the tightropes a writer must walk is knowing when to be tough on yourself and when to give yourself a break.

Toughness means having the guts to challenge your ideas, to examine them for holes and contrivance, to see if they can withstand scrutiny or whether they'll crumble, etc.

Kindness means testing your ideas without killing them. Giving them a chance to bounce back. Letting them grow without grinding them to dust.

Toughness means pushing through the writing of your rough draft until you have it completed. It means not surrendering, not quitting until that task is done. Fatigue, worry, doubt, and interruptions must be withstood in order to keep going.

Kindness means understanding that you will lose your way at times but you'll always find it again. It means knowing that it's natural to become tired. That's nothing to beat yourself up about.

Toughness means facing your mistakes, even when it means jettisoning a scene, chapter, or maybe 100 pages.

Kindness means being glad you found the error and can fix it, and not calling yourself stupid for having erred in the first place.

Toughness means writing the best story and characters you can.

Kindness means knowing that we aren't machines. Some of our stories will be better than others, and that's just the way things are.

Walk the rope, friends.

Walk the rope.

September 13, 2011

The Author's Voice

Years ago, when I had a dozen or so publications under my belt, my old writing teacher Jack Bickham remarked to me: "When I read your copy, I don't detect any authorial voice at all."

I was crushed. At the time, I'd worked so hard on my writing craft, yet here was another thing I didn't know about and didn't provide in my stories. Voice? Voice? Where was I going to find one?

The answer is, of course, inside myself.

We aren't always ready to face that one, are we? Writers can be walking bundles of insecurity, contradiction, angst, doubt, and fear. We doubt that anyone's going to read what we've written. We doubt that anyone's going to enjoy our story. We doubt that anything we create has value or worth. And if those doubts and fears are strong enough, they can muzzle our voice until we silence it completely.

Do so, and you will write stories that may be well-crafted and smoothly paced, but they'll lack the essential connection–the link–that keeps readers coming back to your work.

So which writers appeal to you the most? Which are your favorites? Chances are that their voice is a major part of why you enjoy them so much.

This weekend, I was reading a YA novel called Bloody Jack by L.A. Meyer. It's a ripping good adventure, very enjoyable. I've read it several times. Is there a central antagonist? Not exactly. The story instead relies on a series of adventures as the protagonist skips her way from one mishap to the next. What makes this fast-paced pirate yarn work, however, is Voice. Presented in first person, we're given Jacky Faber's voice in spades, and what a voice it is. She makes the book work. Her personality is vivid enough to sweep readers along.

Characters that distinctive don't come along every day.

Another writer with a strong voice is Jim Butcher. His series protagonist is the wizard P.I. Harry Dresden, and Harry's snarky view of the world in which he inhabits helps lift the stories above just another paranormal tale.

John D. MacDonald's authorial voice is powerful. His soliloquies on anything and everything from jazz to gin to repairing a boat hull to the mind-numbing stupidity of television are wrapped up in the guise of protagonist internalization. And once again, they lift the Travis McGee mysteries out of the ordinary.

Dick Francis wrote with a very distinctive voice that came through every novel he produced.

All these examples are writers who use first-person viewpoint. Is that the answer? Just write in first-person if you want to develop a distinctive voice?

Not the answer. Maybe a step toward finding it.

Consider Dorothy Sayers. She wrote her books in third-person viewpoint, but her voice is distinctive. A few other authors of third-person viewpoint and strong voice:

Agatha Christie

Betty Neels

Georgette Heyer

Alastair Maclean

Jan Karon

Eudora Welty

Ray Bradbury

The list is endless. By now, I'm sure you're wondering why I haven't included your favorite novelist.

Voice shouldn't be muffled. It shouldn't be whispered. It should shout.

It's what you love, what you care intensely about, what you value and honor, what you abhor. It's wrapped up inside your protagonist, and it's not preaching a message. It's sharing your view, your opinion. It's saying, "Here's my insight. Here's what I have to say."

It's being brave enough to let that come out, to take the creative risk to reveal a bit of yourself to people. It's stringing your words together in a style that mirrors what you are. That kind of honesty or self-exposure is natural for some authors, difficult for others. But if we want to be read and remembered, we have to stop creeping in the tracks of writers who have gone before us and make our own footprints in the snow.

September 8, 2011

Speech Tags

One aspect of writing dialogue is how effective a good speech tag can be in carrying emotion forward through the plot.

In the professional writing program at the University of Oklahoma, we define tags as bits of information attached to characters that make them distinct in some way or provide information to readers. There are multiple kinds of tags: speech tags, mannerisms, physical appearance, tags of personality, etc.

Think of an item of clothing in a department store. You have a tag that lists the fiber content, a tag that states the country of manufacture, a tag that gives the size and price, etc.

In the hands of an inexperienced writer, a speech tag may be nothing more than an overused expression distinctive to its assigned character. For example:

"Why don't you get off that dratted chair and come help me shift this hay bale?" John demanded.

"You only had to ask me."

"I shouldn't have to ask! You dratted boys are all alike. Lazy, shiftless, no-good, dratted lunk-heads, that's you!"

The awkward repetition of "dratted" wears thin fast. It's serving no purpose other than to be something John habitually says.

In contrast, an effective speech tag conveys personality, uniqueness, and emotion. It's a reaction to what's happening in the story. It may indicate a decision within the character, as well.

Consider the character Will in David Lean's 1954 comedy, HOBSON'S CHOICE. In this film, Will (played by John Mills) is a shy, semi-literate, inarticulate cobbler. He happens to also be an exceptionally talented shoemaker who's exploited by his employer, Mr. Hobson. But during the course of the film, Will is pushed beyond his comfort zone and low expectations into becoming the owner of his own business.

Actor John Mills

At key points in the film, Will is struck by his progress. Each time he learns to assert himself, his future opens up to an even bigger and brighter one. And at these important turning points in the story, Will can only express himself by staring wide-eyed and saying, "By … gum!"

It is, in fact, the last line of dialogue in the movie.

Of course, the actor John Mills injects different tones and inflections into that simple phrase, but because "By gum" isn't overused or mindlessly repeated, it becomes delightful whenever it's spoken.

Another example of a well-done speech tag comes from Janet Evanovich's comedic mystery series centered around bounty hunter Stephanie Plum. Stephanie fumbles through her investigations with a cast of often zany secondary characters to help or hinder her. One of the two romantic leads is Ranger, a mysterious, dangerous, sexy security expert who sometimes does bounty work with Stephanie. Often, he's called in to rescue her from a tight spot or to provide her with transportation after her car is blown up. (She loses her car in nearly every book. A different kind of tag.)

Ranger's speech tag is "Babe."

If he meets Stephanie for breakfast and he's eating a tofu wrap and she sits down with a donut, Ranger's laconic comment of "Babe" indicates his reproachful opinion of her junk-food diet.

If he sees Stephanie splattered in blood or paint, watching the fire department douse her burning car, "Babe" takes on a much gentler, sympathetic connotation.

And if Stephanie's staying at his place because her apartment door has been kicked in by a goon, when she walks out of the shower in a towel and encounters Ranger in the bedroom, "Babe" can mean anything from admiration to desire.

So, in designing your characters and their styles of expressing themselves, check to see if you've given any of them useful speech tags that will personify them, show their emotions, and advance the story.

September 7, 2011

Staying on Track

There's an ad on TV about financial planning/investing. I think it's Fidelity that runs a green line down the sidewalk for its customers to follow. A man starts walking on the line, but then glimpses a fancy car in a dealer showroom window and pauses. The Fidelity adviser calls out to him to "stay on the line," and with a smile, the man continues.

The ad's well done. It's simple, visual, and effective.

Writers need to stay on a line as well. When we're working on a long, involved project such as a novel, it's easy to get sidetracked. We think, no need to work on the book everyday; I have lots of time until my deadline.

But pulling off the project means the story stops. You may stop thinking about it. You may let another activity or project take over your energy and creative focus. In a week or a month or three months later, when you come back to your novel you find that it's died. It's withered like a shrub left unwatered.

Can you resurrect a dead project? Maybe. A good flogging of craft, skill, determination, and sheer cussedness may be enough to put life back into it. Even so, you'll find that it's not the same.

If you can't revive it, what will you do? Shrug it off and tell yourself that it wasn't much good anyway? Are you going to treat your next writing idea the same? And at what point will your imagination stop serving you ideas that you're going to kill? Why bother?

A draft should be written from start to finish as constantly and as steadily as possible. Drafts of short stories preferably should be written in one sitting. Novels work best when you work on them daily. You may not get much written, or some days will see higher production of pages than others, but it's the steadiness that counts. Our thoughts need to be in our story. It makes us absent-minded and forgetful of other things, but as long as we do no harm (don't forget to feed a baby or pets and don't run stop signs because we're far away in the land of Mugu while we're driving home) what does it matter if we forget to buy cheese or don't listen to every word in our committee meeting?

I know that life interrupts us. A crisis occurs. A big work deadline looms. Someone tramples all over our writing time and leaves us fuming. These things happen. It happened to me this morning.

But we're not always overpowered by such interruptions. Sometimes we let ourselves be interrupted. We aren't ruthless enough in protecting our writing time. We're tired of our book. We're lonely. We're convinced that we're missing all the fun elsewhere.

Are we really? Or are we fooling ourselves?

If we're tired, then we have to find a way to keep going. Writers build their stamina by pushing themselves to stay the course instead of wimping out.

If we're lonely, then we need to make our characters more interesting.

If we're yearning for diversions, then we need to improve the quality of our plot.

Your goal is the completion of your draft. Stay on the line until you get there.

August 31, 2011

When Sparks Connect

In my last post, I discussed how I'm becoming magnetized to stories about waifs and war orphans. All summer I've been encountering them and mulling them over without any kind of forced attention.

I've plenty to do on the writing front, and although it's time to start cooking up a new proposal to submit to publishers, I haven't begun pushing my muse to give me material.

But has my muse perhaps begun to push me?

Over the weekend, an old plot scenario floated up to the surface of my mind. I'd written a manuscript about it years ago, but it was too grim and edgy to catch publisher interest at the time. In that version, I focused on the mother of a little boy as my central character.

Now, the connections are linking up. I want to use that old plot, but shift it around. My focus is going to be the child instead of the mother. An orphaned child. A waif.

Inspiration has come. My synapses are firing. I feel growing excitement over this project. (That's a good sign.) I'll give it a bit more time and see if my "muse magnet" attracts any more information, then I'll start outlining a plot.

Who's going to be the protagonist? The waif or a more streetwise boy?

Who's going to be the antagonist? Right now, I don't have that character, but I do know that formless, faceless Authority won't cut it.

What's the objective? No clue.

What's the story question? Not yet determined.

How many other characters do I need? I have two secondary figures starting to take dim shape in my mind. The rest are but shadows.

How will it end? Not yet determined.

The questions are a test of sorts. I'll see whether any answers come along. If the idea's viable, the answers will come and the story will grow. If the idea's not viable the whole thing will fade.

August 24, 2011

Follow Your Theme

Where do ideas come from?

*Beating your imagination like slave labor?

*Trying out the creativity exercises you find in blogs like this or in writing magazines or self-help books for writers?

*Keeping your muse well-fed, happy, and entertained?

*Listening to the small, quiet inner voice of your story sense when it starts to lay curiosities at your feet?

All of the above?

Let's examine that last question about listening to your curiosity.

Do you ever let it come, one small piece at a time, until you understand how these bits connect and whether you can transform them into a story?

I don't discuss theme often because some inexperienced writers tend to confuse theme with message. Theme–in the context of what I want to discuss today–is not an opinion you're going to cram down the reader's throat. Instead, it's an idea or perception that fascinates a writer and provides a wellspring of material.

When I'm developing a new theme–or area of fascination–I become very aware of details and ideas that pertain to it. I may have brushed past them before without ever noticing them. Now, I'm a magnet, and they vector toward me and cling.

For example: I happen to be an estate sale junkie (pun intended). Earlier this summer I drove rather a long way to a small community and a modest brick house on an acreage. Liquidators were closing the estate of a remarkable woman who was born in Poland and at the age of 14 was taken by the Nazis for labor. She worked as a maid, cleaning the home of a Nazi couple, and suffered daily abuse from the woman she worked for. At the end of WWII, there was liberation. She met an American soldier, married him, and came to America. Her small home was crammed with lovely items: porcelain figurines, trinkets, glassware, china, and needlework–all of fine quality and workmanship. You could see how this woman, who lost her family and suffered through terrible ordeals, had clung to a love of beauty and grace.

Her story has haunted me all summer. A few nights ago, I happened upon Montgomery Clift's first movie, THE SEARCH. I'm not a fan of Clift's, although he was an excellent actor and performed in stellar, thought-provoking movies. I almost switched this film off, but instead gave it a chance.

It's compelling and emotionally haunting. It deals with the plight of orphaned and lost children immediately after WWII, children torn from their homes by the Nazis, children put in labor camps or concentration camps, children starved, abused, and shocked, children tattooed with numbers on their arms. They're terrified of anyone in a uniform and don't understand that the Americans are trying to help them. They're French, Czech, Dutch, Polish, Lithuanian, etc. and don't understand English. The film focuses on the plight of one child, a little Czech boy who's been in Auschwitz. He can't remember his name or his mother or where he comes from. An American GI befriends him, teaches him English, gives him kindness, clothing, and food, and helps him find his family again.

As I watched THE SEARCH, I saw a scene depicting a girl of perhaps 12 or 13, clutching a small, ragged cloth bag containing the head of a doll, a watch, and another small item–all she had left of her former home. I thought of what I'd heard at the estate sale, about how that woman took only her doll and the family watch with her.

I have my family's ancestral watch–the timepiece of a great-great grandfather passed to my great-grandfather to my grandfather to me.

Connections.

Spider webs of ideas and concepts. Slender threads of curiosity weaving together with emotional response.

After I watched THE SEARCH, I thought back to one of my favorite films. It's called LITTLE BOY LOST, and it also deals with orphans after WWII. It's more schmaltzy than THE SEARCH, but in both films the young boy steals the show and makes it work.

LITTLE BOY LOST deals with an American journalist assigned to Paris. He marries a Frenchwoman and they have a baby son. While he's out of the country on business, the Germans occupy Paris and he's unable to return. His wife joins a Resistance group and is killed. The little boy vanishes. When the war ends, the man combs every French orphanage in search of his boy. The matron of one orphanage tells him his search is hopeless. She sets him up with Jean, a spindly little boy with big soulful eyes–nothing at all like the robust son the American envisions his boy to be. She tries to persuade this grieving, embittered man to adopt Jean, to help another child if he cannot help his own.

Although the casting is odd–Bing Crosby plays the role of the American father–it's neither a comedy nor a musical. Instead, it's about false expectations, loss, heartbreak, and reunion.

There's one more film that I've seen many times and happened to watch again a few weeks ago: RANDOM HARVEST with Ronald Colman and Greer Garson. It's set after WWI and it's a love story, not a tearjerker about homeless children. Yet Colman's amnesia gives him a slight waif-like quality. He's just as lost, just as cut off from his past, home and family.

There are too many portents and pointers telling me to pay attention to all this. What is my story sense trying to convey? What, emotionally, is drawing me to these themes? What are the feelings involved in these dramas? What connections am I making? Where am I going with them?

I don't know yet, but I've learned to follow these trails until enough ideas stick to me and I figure out what I want to do with them.

Are you listening to your curiosity?

August 22, 2011

Villains Behind the Curtain

"Orders are nobody can see the Great Oz! Not nobody, not nohow!"

–Frank Baum

One of the writing tenets I absolutely believe in is that every scene needs an antagonist. Follow this simple principle, and you'll be amazed at how much easier it is to write.

However, sometimes I meet resistance, puzzlement, and reluctance when I try to share this with others.

"But I don't want my villain revealed just yet!" is usually one of the biggest laments.

Okay.

Last week, I read several Agatha Christie mysteries. Her plots are marvels; her twists are legendary. She's deceptively simple on the surface level while offering complex human emotions and motivations beneath. If you're writing a mystery you don't want to reveal the villain at the start. The character will be present in the cast, but concealed within a deceptive guise.

Or the villain will come and go in the story, as in the case of the Harry Potter novels. Voldemort is mentioned in Chapter One, and the dread of him hangs like a cloud over the entire series. Yet he actually appears only occasionally, usually at the climax of each book. The rest of the time, Harry and his friends are coping with a succession of intermediary villains. Rowling keeps her young readers guessing by having troublesome teachers prove to be allies and friendly teachers prove to be cohorts of Voldemort's.

I think that inexperienced writers often stumble here when concealing the real villain's identity. They hide the character too well, and the individual simply isn't in the story until the climax. Then a villain pops up out of the blue, and it all looks very contrived.

What a writer must remember to do is establish the villain's role. Establish the existence of the villain. Acknowledge it either through character comments, the protagonist's thoughts, or switching viewpoint to the villain for the reader's information.

To return to mysteries: the identity of the murderer isn't going to be revealed until the end, but as soon as a victim is discovered, readers and the sleuth alike know there's a bad guy out there somewhere, a criminal who must be caught and punished.

In thrillers, the villain's actions are pivotal to the plot. Readers often meet the villain before the protagonist. But the story's emphasis doesn't lie with discovering identity; it's about stopping whatever the villain's up to. So if you pick up a Ken Follett thriller, say a classic like THE MAN FROM ST. PETERSBURG, you know who the assassin is, you watch the man dodging police and mixing nitroglycerin bombs in his rented room, and you wonder if anyone in the story is going to save the Tsar's cousin from assassination. To keep his good guys from looking stupid, Follett lets the British authorities know there's an assassination attempt brewing, but they can't track down the villain in time. The girl who befriends the villain has no clue who he really is or what he's trying to do. She thinks he's rather nice while he makes a patsy of her.

What if you're writing a fantasy yarn and your characters are on a quest to take back the Scroll of Magick and restore it to where it rightfully belongs? Your band of sojourners aren't going to meet the villain until near the end, but they have a concept of a villain's involvement with the story events. They may or may not know the evil sorceress's name or where her dark castle stands. They may have to search a long time before they confront her. But they are seeking her, and–like Harry Potter–they'll encounter plenty of trouble along the way. Evil sorceress isn't going to sit tamely in her castle and wait for them to show up. She'll throw all sorts of traps and pitfalls in their path.

To satisfy the principle of always having conflict, a writer of the hidden-villain story needs two kinds of opponents: intermediary antagonists and a master villain that's active behind the scenes.

The intermediary antagonists are often a successive string of foes. They hinder the protagonist as much as possible. Even so, it's important to salt the plot with a few encounters between the protagonist and the master villain as well.

How?

Be clever. In fantasy and science fiction, you can have confrontations in dreams and via mental communication, teleportation, and spells, etc. In other genres, you can utilize phone calls and text messages. You can have the villain leave cryptic origami birds on the protagonist's desk at work or inside her apartment as creepy little reminders that no place is safe and nothing is secure.

In my YA fantasy series, The Faelin Chronicles (under pen name C. Aubrey Hall), the protagonist is a boy who has visions. He's still learning magic, so he misinterprets the information at times. In The Call of Eirian (April 2012), he "sees" a pair of eyes staring at him from the sky just before he and his friends are attacked. He mistakenly identifies the attacker and doesn't learn the truth until much later in the story. The error keeps the boy's characterization plausible, sets up for a plot twist, and continues to hide the identify of the real villain for a few more chapters.

August 19, 2011

Making Pearls

In past posts, I've written about the dangers of distraction and how it can sabotage your story-in-progress. There are two primary types of distraction: those out of our control and those we create for ourselves.

The first camp includes such things as weather, nuclear attack, doorbells, phone calls, electricity cuts on a clear summer's day, neighbors, and repairmen. (To name only a few.)

My patio since the roofers, guttering men, and fence repairers came. Nothing like a hail storm to help your book along.

Some of these are more out of our control than others. Can you go without a hot-water tank until your chapter is written? Yes! Can I go without air conditioning in this plus-100-degree weather? No!

Setting possible nuclear attack aside as the facetious nonsense it is, there are ways to mitigate the effect of most of these distractions that come at us from the blue.

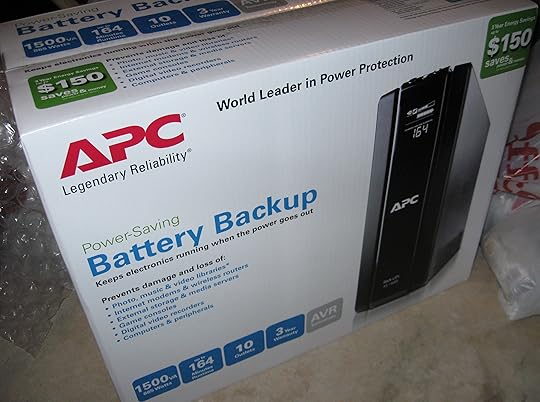

Installing a battery backup for your computer gear helps with weather and electricity cuts. I've used such a system for years. It won't handle everything, much less eliminate the distraction, but it helps you stay calmer than you would be otherwise. Last year, when I moved to my present abode, I tried to save money by purchasing a backup that's too small to do its job properly. Sitting down for a writing session with the worry that at any moment an electrical spike could DESTROY ALL is certainly a distraction. A few days ago, I finally got a bigger system. Now to find time to connect it ….

This is not an endorsement for this product. It just happens to be what I bought. I've probably gone too large this time, but we'll see.

Phone calls can be handled via discipline. You don't install a phone in your writing room or you let the voicemail pick up. Both solutions require iron-hard willpower–easier to discuss than to maintain. There are certainly moments in my writing time when I'd be thrilled to have the distraction of a phone call. (Beware such impulses. If you can't control them, remove the phone.)

As for distractions that we create for ourselves, I'll include computer games, Internet and emails, lunch dates, overscheduling, hobbies, and rewards.

These can all be dealt with, provided we're firm. Computer distractions can be controlled in a variety of ways–everything from turning off the little chime that announces you have a new email to writing on a computer that's never online. I take the latter route. It seems extreme, I know, but let's chalk it up to my artistic, dramatic temperament. Besides, once I attach myself to my favorite blog (myoldhistorichouse.blogspot.com) I can lose myself for an hour or more. But if I have to wait for the online computer to boot up (so s-l-o-w!) and switch chairs, I have time to feel guilty and make myself behave.

Now, the true reason I set up two computers in my writing office years ago was for security purposes. I keep my book and my income tax records on the writing computer that's never online to protect it against viruses and hackers, to help it last longer, and to circumvent distractions like computer mah jongg. I don't know how old the machine is–ten years? It boots in a flash because it's not clogged to death with patches, updates, cookies, pop ups, and all the endless junk that assails my online computer. It's never crashed and never had to go in for a tune up or repair. When I'm ready to write, I switch on the tower and the machine is ready in seconds. Less distraction.

Convenient? Not when I need to check emails or send off an attachment or research something. Which is better? No distractions or convenience? You know what I've chosen.

Lunch dates? A problem? Really?

Yes.

Several years ago, when my career was young, I was lunching with the very successful mystery author Carolyn Hart. I suggested that we meet again in a few weeks, and she refused because she was about to start a new book. She said she didn't go out to lunch when she was writing.

I didn't understand at the time. Lunch is important. At least to me! I'm going to stop writing in order to eat. What's distracting about that?

Eventually wisdom and understanding dawned on me. Set a lunch date or any appointment, and you have it in the back of your mind. It may be something pleasurable that you're looking forward to rather than something you dread. Even so, it can be a distraction. It takes time. It removes your thoughts from the job at hand.

I haven't given up all lunch dates, but I limit them to whatever day of the week I reserve for errands rather than writing.

Overscheduling can involve any number of things. You have a day job, family, friends, movies to see, events to attend, birthdays or celebrations, errands, etc. The list goes on and on to formidable lengths.

Schedule one additional activity to a writing day and see how many other appointments will attach themselves. I like to make out to-do lists to help myself stay organized. Usually the list will start with something "critical," like Bank, Post Office, Haircut, Vet's Office, and Writing. Why does writing always get listed at the bottom?

My writing teacher, Jack Bickham, recommended that any to-do list be flipped over, so that you began your day with Writing and later got to whatever else remained on the list.

Hobbies? Sure, I love them. I think writers need them to help spur creativity. But if they eat into writing time, or if you're thinking about that train diorama you want to build or that quilt you want to stitch instead of the scene you're about to write, then you're allowing yourself to be distracted unnecessarily.

I bought these at the flea market. Now they need polishing.

Same thing goes for rewards. There have been books that I haven't been very passionate about writing and projects that I contracted for solely to earn money. In those circumstances, I've often employed the carrot-and-stick method of discipline in order to meet my deadline. But even when I'm writing a book that I care intensely about, there are going to be sections where the passion fades. I may be thinking, If I meet my page quota by noon, I'll have time to drive to the City and shop at the bookstore. A distraction? You betcha!

Are you thinking by now that I intend for you to be a robotic writer, a Vulcan robotic writer that never feels, never deviates from the plan, never sneaks a little game of Solitaire, never wastes two precious hours of writing time on eBay?

Not at all!

We are, after all, humans first and then writers. Just beware the distractions that don't have to be in your life. Ask yourself why you're letting them hinder you instead of getting on with the story at hand.

This morning, the fence guys arrived at 7:30 a.m. to continue powerwashing my fence before it's stained. For hours I've listened to the throb of that machine outside my office wall. Have I written on my book? Not as yet today.

So small a machine, so loud a noise.

I could have. Instead, I've chosen to let the powerwasher "distract" me. Why? Because I really don't want to write the next scene and I've chosen not to crack the whip of discipline.

I'll pay for it later when I have to catch up on my page quota.

Where we are by noon. To quote the pope when Michaelangelo was painting the Sistine Chapel: WHEN WILL IT BE FINISHED?

August 9, 2011

Where Are We Going?

In my last post, I commented on disconnected or random conflict and the problems it can cause a writer.

I don't mean the kind of story where seemingly unrelated problems arise, but then at midpoint begin to fall into place and connect, leading to discovery of the true villain's identity.

I mean the kind of episodic, disjointed sort of story that rambles around without a true central antagonist at work and depends on shock or mayhem to propel the plot instead of cause-and-effect. Imagine the events of THE WIZARD OF OZ transpiring without the Wicked Witch.

My writing students are gravitating more toward this awkward plot structure. I find it increasingly difficult to correct. What is the root of this problem? I can find several things that, in combination, are affecting how story is perceived. Is it an evolution or an erosion?

1) The invention of the World Wide Web.

2) Video games

3) Role-playing games

4) Book series that are open-ended

None of these four factors is negative or undesirable; however, their prevalence helps generate a different audience expectation than perhaps some writers have dealt with before.

Recently, while having dinner with another author, I expressed frustration in getting my students to understand cause-and-effect plotting.

"That's because you're a linear thinker," my friend said. "Your students are web thinkers."

It explained a lot. I am indeed a linear writer. I grew up reading linear stories–meaning plots that move from a beginning point through a progression of tougher obstacles to an objective. Every action compels a reaction to occur, and the story advances with logic underlying its emotions and conflict.

I was trained to be linear. My writing craft is founded on cause-and-effect principles. Characters in my stories may be puzzled or baffled for a while, but they sort things out. No one is acting without a reason, whether or not those motivations are apparent to the protagonist at any given time.

The last time my agent shopped a prospective book synopsis around for me, one publishing house rejected it because it was "too linear."

Of course, the project sold to someone else. But that particular rejection has haunted me since. Initially, I didn't understand what it meant. My agent was likewise baffled. Yet since then, I've come to suspect that the fiction world is being assaulted by a quiet revolution.

Not the self-publishing versus legacy publishing debate currently raging among authors.

But instead one that speaks to the very heart of what story is and how to present it to readers. Is anyone paying attention to this? Is this issue the tiny leak that's going to eventually crumble the whole dam?

Linear story is based on a construction that dates back to antiquity, to the very first stories ever told. It pits protagonist against antagonist in a step-by-step, cause-and-effect progression of attempts and partial failures until the story's climax, where sacrifice, risk, and heroic action lead to victory . . . or defeat. At its best, this type of story is engrossing and cathartic.

Non-linear stories, however, aren't concerned with an arc of change for the protagonist. There may or may not be a central antagonist. Events are random problems to be solved that may or may not lead in any particular direction. Sacrifice doesn't often occur, or it happens to anyone but the protagonist. Poetic justice is ignored. The characters rush from here to there. They encounter danger and solve problems, and if they ricochet long enough there's an outcome of sorts.

As an example, let's consider a series of teen thrillers by Alexander Gordon Smith that begins with a novel called LOCKDOWN: ESCAPE FROM FURNACE.

It's fast, creepy, and shocking. It deals with a boy who's framed for a brutal murder, tried and convicted, and incarcerated in a horrifying prison. There's just enough linear structure to hold this story loosely together. The rest of it careens from one shock or problem to the next. There's a hint of an unseen antagonist, but the shadow force is so vague and nebulous that the story can't hinge on it. The ending is left open. The protagonist doesn't change significantly. Readers are supposed to read the next volume and the next, hoping–presumably–to eventually get answers.

LOCKDOWN serves process-oriented readers, those who are entranced by the grim story world and are so determined not to reach an end to this experience that they're willing to be cheated by the story's last page.

Compare Smith's tale to THE LIGHTNING THIEF by Rick Riordan. In this wildly popular YA story, the construction is definitely linear.

The protagonist is a dyslexic boy named Percy, who discovers he's the son of his human mother and one of the Greek gods of antiquity. Percy and his companions go on a quest to recover the stolen lightning bolt of Zeus. They constantly encounter traps and obstacles, but their unknown antagonist's hand is clearly working against them. Eventually, Percy identifies the villain and confronts him. Percy also discovers the identity of his father. And although this book is the first of a series, its plot is resolved. Percy goes through a significant arc of change. He fulfills the story role of hero through his sacrificial and courageous actions. This story serves results-oriented readers, those who expect a definitive outcome to Percy's adventure. These readers may wish for another story about Percy, but they'll continue because they've received a solid, rewarding reading experience. Their time spent in this story world has been worthwhile, and Riordan hasn't used tricks and shock just to keep them there.

The protagonist is a dyslexic boy named Percy, who discovers he's the son of his human mother and one of the Greek gods of antiquity. Percy and his companions go on a quest to recover the stolen lightning bolt of Zeus. They constantly encounter traps and obstacles, but their unknown antagonist's hand is clearly working against them. Eventually, Percy identifies the villain and confronts him. Percy also discovers the identity of his father. And although this book is the first of a series, its plot is resolved. Percy goes through a significant arc of change. He fulfills the story role of hero through his sacrificial and courageous actions. This story serves results-oriented readers, those who expect a definitive outcome to Percy's adventure. These readers may wish for another story about Percy, but they'll continue because they've received a solid, rewarding reading experience. Their time spent in this story world has been worthwhile, and Riordan hasn't used tricks and shock just to keep them there.

I try to comfort myself with the economic outcomes of these two books. Riordan's classically designed story has–so far–outsold Smith's shocker. I'm glad, but not because I'm out to disparage Smith's work. I read LOCKDOWN: ESCAPE FROM FURNACE with curiosity and got a certain amount of entertainment value from it. But it must always been seen for the type of book it is and not presented as a model of writing that should be emulated.

No, I'm glad for Riordan's success because it shows that an audience will still respond–and respond well–to the linear, classically designed story.

However, I think it's unwise to be complacent. If we're going to preserve cause-and-effect tales as the foundation of modern fiction–of all fiction–then we're going to have to fight for this construction and stand diligently for its defense.

August 3, 2011

Beware the Twilight Zone

You're writing a scene or chapter that you've meticulously plotted and planned ahead of time. You know where your story is going. You know what you want your characters to do. As soon as you finish with this plot event, you know where your story will go next.

You are–in effect–prepared.

Then something weird happens. An unseen force reaches out from the blinking cursor on your computor monitor and enters your brain. Your plans go fuzzy. The character dialogue becomes circular. The plot bogs down and will not move forward. You fume and strain and retype, and still you cannot advance. The next plot event seems to be receeding from your grasp.

Why, you wonder, won't your characters go there?

The reason is, my friend, that you have fallen into an alternative dimension of writing, where the best-laid plans go awry. This strange place is a trap, where your words become as meaningless as the angry buzzing of a fly bouncing into a glass windowpane again and again … and again.

Baffled and frustrated, you check your outline. There's nothing wrong with your story. Your events are sequential, with no illogical gaps. You check your characters. Each is well drawn and outspoken. In fact, your characters are talking too much. You seem unable to stop them. What they're saying is rather witty. Yet the story is not advancing.

How can you escape? Is this some type of advanced writer's block? Has your story sense abandoned you? Have you developed some mysterious variety of writer's blight?

No, my friend. You have omitted the element of "Connected Conflict" and utilized "Random Conflict" instead.

This problem is usually caused by the absence of a key character–the central story antagonist.

This individual has a vested interest in thwarting your protagonist's actions, and this individual is strongly–and logically–motivated to stand in your protagonist's way.

Yes, yes, I know all that, you may be saying. But for the first five chapters, my villain needs to be in Hoboken.

Especially when writing series fiction, it's easy to fall into awkward plot situations where the central antagonist is off-stage for a large section of the story. This leaves your protagonist to deal with incidental or minor antagonists instead.

It looks like it should be okay. You've designed conflict. You've got arguments and the kind of story action where characters are moving here and there to some degree of urgency.

But if you're honest, you'll realize there's something phoney about the whole thing, something contrived, something that doesn't quite click the way it should when scenes are crafted well.

But the story has to BE this way! you may be insisting.

Does it?

Without the connection of antagonism between protagonist and antagonist, the story will quickly devolve into incidents loosely strung together. You lose the internal logic of cause-and-effect. The plot begins to soften and bog down. It becomes more realistic and less constructed. As a result, you're left with author contrivance and a series of episodic skirmishes between randomly appearing individuals.

This will shunt you into the spongy dimension of bad story dynamics faster than you can realize you've exited the road.

Solution?

Stop.

Back up.

Figure out exactly where you left the central antagonist behind.

Plot a way to re-incorporate this character actively into the story.

Watch the knots in your scenes untangle and see how the story zooms forward once more.

C. Aubrey Hall's Blog

- C. Aubrey Hall's profile

- 7 followers