Where Are We Going?

In my last post, I commented on disconnected or random conflict and the problems it can cause a writer.

I don't mean the kind of story where seemingly unrelated problems arise, but then at midpoint begin to fall into place and connect, leading to discovery of the true villain's identity.

I mean the kind of episodic, disjointed sort of story that rambles around without a true central antagonist at work and depends on shock or mayhem to propel the plot instead of cause-and-effect. Imagine the events of THE WIZARD OF OZ transpiring without the Wicked Witch.

My writing students are gravitating more toward this awkward plot structure. I find it increasingly difficult to correct. What is the root of this problem? I can find several things that, in combination, are affecting how story is perceived. Is it an evolution or an erosion?

1) The invention of the World Wide Web.

2) Video games

3) Role-playing games

4) Book series that are open-ended

None of these four factors is negative or undesirable; however, their prevalence helps generate a different audience expectation than perhaps some writers have dealt with before.

Recently, while having dinner with another author, I expressed frustration in getting my students to understand cause-and-effect plotting.

"That's because you're a linear thinker," my friend said. "Your students are web thinkers."

It explained a lot. I am indeed a linear writer. I grew up reading linear stories–meaning plots that move from a beginning point through a progression of tougher obstacles to an objective. Every action compels a reaction to occur, and the story advances with logic underlying its emotions and conflict.

I was trained to be linear. My writing craft is founded on cause-and-effect principles. Characters in my stories may be puzzled or baffled for a while, but they sort things out. No one is acting without a reason, whether or not those motivations are apparent to the protagonist at any given time.

The last time my agent shopped a prospective book synopsis around for me, one publishing house rejected it because it was "too linear."

Of course, the project sold to someone else. But that particular rejection has haunted me since. Initially, I didn't understand what it meant. My agent was likewise baffled. Yet since then, I've come to suspect that the fiction world is being assaulted by a quiet revolution.

Not the self-publishing versus legacy publishing debate currently raging among authors.

But instead one that speaks to the very heart of what story is and how to present it to readers. Is anyone paying attention to this? Is this issue the tiny leak that's going to eventually crumble the whole dam?

Linear story is based on a construction that dates back to antiquity, to the very first stories ever told. It pits protagonist against antagonist in a step-by-step, cause-and-effect progression of attempts and partial failures until the story's climax, where sacrifice, risk, and heroic action lead to victory . . . or defeat. At its best, this type of story is engrossing and cathartic.

Non-linear stories, however, aren't concerned with an arc of change for the protagonist. There may or may not be a central antagonist. Events are random problems to be solved that may or may not lead in any particular direction. Sacrifice doesn't often occur, or it happens to anyone but the protagonist. Poetic justice is ignored. The characters rush from here to there. They encounter danger and solve problems, and if they ricochet long enough there's an outcome of sorts.

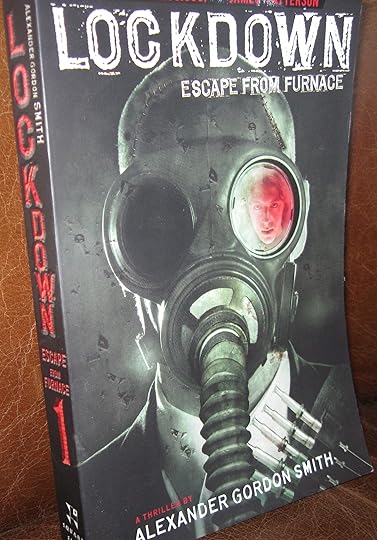

As an example, let's consider a series of teen thrillers by Alexander Gordon Smith that begins with a novel called LOCKDOWN: ESCAPE FROM FURNACE.

It's fast, creepy, and shocking. It deals with a boy who's framed for a brutal murder, tried and convicted, and incarcerated in a horrifying prison. There's just enough linear structure to hold this story loosely together. The rest of it careens from one shock or problem to the next. There's a hint of an unseen antagonist, but the shadow force is so vague and nebulous that the story can't hinge on it. The ending is left open. The protagonist doesn't change significantly. Readers are supposed to read the next volume and the next, hoping–presumably–to eventually get answers.

LOCKDOWN serves process-oriented readers, those who are entranced by the grim story world and are so determined not to reach an end to this experience that they're willing to be cheated by the story's last page.

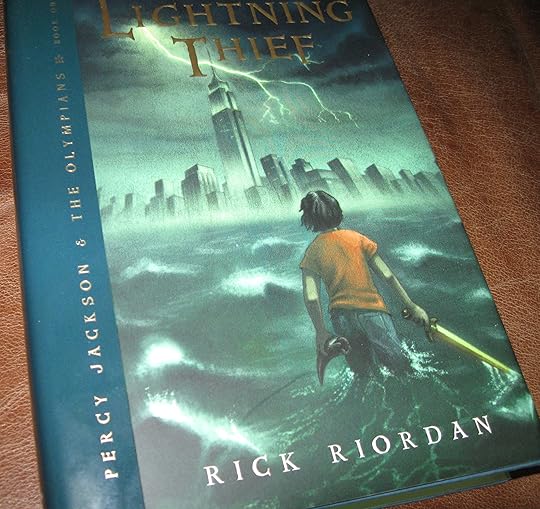

Compare Smith's tale to THE LIGHTNING THIEF by Rick Riordan. In this wildly popular YA story, the construction is definitely linear.

The protagonist is a dyslexic boy named Percy, who discovers he's the son of his human mother and one of the Greek gods of antiquity. Percy and his companions go on a quest to recover the stolen lightning bolt of Zeus. They constantly encounter traps and obstacles, but their unknown antagonist's hand is clearly working against them. Eventually, Percy identifies the villain and confronts him. Percy also discovers the identity of his father. And although this book is the first of a series, its plot is resolved. Percy goes through a significant arc of change. He fulfills the story role of hero through his sacrificial and courageous actions. This story serves results-oriented readers, those who expect a definitive outcome to Percy's adventure. These readers may wish for another story about Percy, but they'll continue because they've received a solid, rewarding reading experience. Their time spent in this story world has been worthwhile, and Riordan hasn't used tricks and shock just to keep them there.

The protagonist is a dyslexic boy named Percy, who discovers he's the son of his human mother and one of the Greek gods of antiquity. Percy and his companions go on a quest to recover the stolen lightning bolt of Zeus. They constantly encounter traps and obstacles, but their unknown antagonist's hand is clearly working against them. Eventually, Percy identifies the villain and confronts him. Percy also discovers the identity of his father. And although this book is the first of a series, its plot is resolved. Percy goes through a significant arc of change. He fulfills the story role of hero through his sacrificial and courageous actions. This story serves results-oriented readers, those who expect a definitive outcome to Percy's adventure. These readers may wish for another story about Percy, but they'll continue because they've received a solid, rewarding reading experience. Their time spent in this story world has been worthwhile, and Riordan hasn't used tricks and shock just to keep them there.

I try to comfort myself with the economic outcomes of these two books. Riordan's classically designed story has–so far–outsold Smith's shocker. I'm glad, but not because I'm out to disparage Smith's work. I read LOCKDOWN: ESCAPE FROM FURNACE with curiosity and got a certain amount of entertainment value from it. But it must always been seen for the type of book it is and not presented as a model of writing that should be emulated.

No, I'm glad for Riordan's success because it shows that an audience will still respond–and respond well–to the linear, classically designed story.

However, I think it's unwise to be complacent. If we're going to preserve cause-and-effect tales as the foundation of modern fiction–of all fiction–then we're going to have to fight for this construction and stand diligently for its defense.

C. Aubrey Hall's Blog

- C. Aubrey Hall's profile

- 7 followers