C. Aubrey Hall's Blog, page 44

March 22, 2011

Me, Myself & I

What is your protagonist's self-opinion?

Does she believe she can never do anything right? Is she always late? Does she hate her own body image? Does she feel eclipsed by her younger, beautiful sister?

Or perhaps she thinks very highly of herself, values her opinions above others, believes in speaking frankly even if it hurts someone's feelings, and feels complacent, sure of herself, and entitled.

We have two very different women here, don't we?

Example A (let's call her Amelia) is going to behave in certain ways that reinforce her self-concept. She may make remarks such as, "Don't depend on me to be there on time. You know I'm always late." Or she may grow flustered whenever given a responsibility. She will reflect her dislike of her body image by the clothing or colors she wears. And even if friends invite her along, she may refuse to join in the fun if her sister is part of the group.

Example B (let's call her Beatrice) will always be dispensing advice, whether the recipient has asked for it or not. She will speak loudly and in a forthright, blunt manner. She will probably trample over the feelings of people like Amelia, and then become impatient or embarrassed by the reaction she gets. She will be calm and self-assured in her demeanor. She will always take the best chair or help herself first to the plate of cookies. Even if she is overweight, she will not be embarrassed by it, but may instead drop comments such as, "You should know, dear, that men always prefer full-figured women to beanpoles."

In character design, choose that individual's self-opinion and then devise personality traits and behaviors to correspond. You'll end up with a believable, plausible character.

March 10, 2011

Character Hobbies! Why?

"Beware the hobby that eats."

–Benjamin Franklin

Last year, I was coaching a student who'd gotten stuck in plotting his manuscript. I asked Pete about his protagonist's favorite flavor of ice cream.

Blank stare.

Pete was writing a serious, forensic-focused mystery. He never understood why I was asking about ice cream when he needed to get his character through a problematic scene about a broken chain of evidence.

I wanted to make Pete see that he didn't know his character well enough to solve the scene. If you can't call up a character's favorite drink, ice-cream flavor, or type of music, you're unlikely to be clear about how that character's going to deal with challenging plot situations.

Knowing your character's hobbies, however, doesn't mean you're going to center your story around them or chase after tangents. It means you're adding enough extra dimension to bring the protagonist to life.

Quick! Name character Travis McGee's favorite brand of gin: (Boodles, and later, Plymouth.) Quick! Name character James Bond's favorite cocktail: (a dry martini that's shaken, not stirred.) Quick! Identify the name of character Spenser's dog: (Pearl.) Quick! Name character Harry Potter's favorite sport: (quidditch.)

Authors John D. MacDonald, Ian Fleming, Robert B. Parker, and J.K. Rowling have all understood the value of knowing what their protagonists do for fun. Even STAR TREK's somber Mr. Spock played a Vulcan harp and three-dimensional chess in his off-duty hours.

The standard writing advice is to construct a character consistently from a foundation of focused dominant impression. I agree with that method. I even teach it. But if you don't add additional layers and texture to a character from that basis, you'll end up with a character that's superficially vivid and even effective to a limited degree, but ultimately devoid of life.

Example: Say that you want your protagonist to be serious.

Let's call him Joe.

He's six feet two and muscular. He has steel-gray eyes and blond hair clipped short. His features are chiseled. Maybe he has a faint scar on his chin. His background includes service as a former Navy SEAL and playing college football for Alabama. He's married to a dentist named Lauren. They have no children, no pets. Joe is dependable, responsible, loyal, and protective. He's conservative in religion, politics, and finances. He drives a blue sedan, chosen for gas economy. He and his wife live in a middle-class suburb in a remodeled mid-century house.

I could go on and on, but by now I figure you're losing any initial interest you might have had in Joe. I'm bored with him, too.

Why? He's vivid physically and his military background hints at possible excitement, but the more I continue choosing details that only fit his dominant impression of "serious," the more he starts to flatten as a character. He's lifeless, and no matter how much research I might do on the grade and color of his wall-to-wall carpet, piling on additional consistent details isn't going to help.

What does Joe do in his spare time when he's not involved in your story's plot events? Does he listen to music? Tinker on an old car? Play computer chess? Build boats in his basement? Coach Little League baseball? Grow orchids competitively? Attend flea markets?

Let's say that he loves to play poker. You can leave it at that level, and show a relaxed side of Joe that enjoys inviting his friends over to his man cave in the garage, where they gamble for low stakes and drink beer while the game's on.

If we want to bump up the intensity a notch, we might choose to put a severe gambling addiction in Joe's past. Now, he bets with bottle caps and tries to hide how much his hands shake when his friends discuss more serious betting.

Or, we can escalate Joe's hobby into a plot problem. He's convinced he's under control, only he's down to the tune of $80,000. He told his wife he went on a business trip, but instead he sneaked down to Tunica, Mississippi, and spent three crazy days in the casino. Now, if he pulls that much money from savings, his wife will be asking questions he doesn't want to answer. Meanwhile, there's a poker championship he's dying to enter, and he spends the mortgage payment for the entry fee. After all, if he wins the championship, the prize will pay for half of his outstanding debt.

Why does Joe love to gamble? Does he like the challenge and stimulation of the game? Is it the adrenaline rush, the feeling of being on the edge that he misses now that he works in a dull corporate office? Maybe he learned how to play as a kid and was always good at it. Maybe he got into it in college. Maybe it steadied his nerves before dangerous missions while he was in the Navy.

Something in his background is going to explain why he has this passion or obsession now. As you design his character, seeking answers to questions of why will make you dig deeper into what makes this guy tick. He starts to come to life. He starts to become interesting.

February 27, 2011

Character Background: The Good and the Ugly

What's good and useful about character background?

It makes you better acquainted with the character you're designing. If you know where the character grew up and with what type of family, that automatically gives you a better perspective. You'll find it easier to write plausible, consistent character reactions. For example, you'll know why Irmentrude freaks out whenever she sees even a photograph of a spider (because her little brother used to put his pet tarantula on her face while she was sleeping), and you can present her adult phobia in your story with compassion and an added dimension.

Mexican blood leg tarantula. Photo from reptilesalive.com

The noir film that made a star of actor Alan Ladd was This Gun for Hire. He played a stone-hearted, sociopathic assassin who shoots a number of unsavory characters and seems only able to care for stray cats. But there's a famous moment in the film when he shares an event from his childhood. The woman giving him foster care broke his wrist with an iron because he reached for a chocolate bar. And as he talks about that moment and other examples of mistreatment, his eyes shimmer with tears and we can see in his face that unwanted, abused child. The audience understands how he's grown up into a violent, desperate, isolated man thanks to a brutal background. The film doesn't condone his adult crimes, but it creates a depth to his character that he wouldn't otherwise have.

Alan Ladd plays the killer Raven in 1942's THIS GUN FOR HIRE. Photo from Paramount Pictures.

What's ugly about character background?

It can become a trap for the unwary writer. If you aren't careful, as you write pages and pages of a background dossier you'll then feel compelled to share all of it with your readers.

Don't.

Hemingway's old iceberg theory certainly applies here: just as only the tip of an iceberg shows above the surface, so should you share maybe 10% (or less) of what you know about your characters with your readers. Save the rest for your own insight and understanding.

Also, make sure you only devise enough background to help you fully know and understand your characters, especially their motivations. If you aren't careful, you can spend too much time on background and never get around to actually creating the story. Let your plot dictate what their backgrounds will be. Again, with my Alan Ladd example: we learn only enough about his past to understand why he grew up to be a killer. No more than that.

It's a matter of balance.

February 23, 2011

Creating Characters

From time to time, I'm asked for my secret list of character building. It's not really "my" list. I obtained it by taking Jack Bickham's writing classes at the University of Oklahoma some years ago, and use it now in my own courses. To most of these inquiries, I usually give the same answer: read CREATING CHARACTERS by Dwight V. Swain or WRITING NOVELS THAT SELL by Jack Bickham.

But a response like that, while sincerely offered and genuinely helpful, tends to disconcert some folks. I'm reminded of the advice I was given years ago when I decided I wanted to study Latin: "go and buy a copy of Wheelock; you can learn the basics yourself."

Sure. Teaching yourself writing technique is about as easy as teaching yourself a different language. Possible, but not very probable.

So with thanks to Bickham, I'll be sharing a few things that I know about characterization in the series to come.

BASIC CHARACTER ELEMENTS

This very simple character checklist — or one similar to it — is something that you've probably seen before. That's okay. Just because it's simple doesn't mean it's ineffective.

Name

Age

Gender

Education

Marital status

Social and economic status

Family

Friends & Enemies

Job

Hobbies

Appearance

Clothing and habitat

Goal

Key background facts

Opinion of self

Others' opinion of him or her

Characteristic entry action

Repeating tags or tag clusters

Some of the items are self-explanatory. Others obviously need more elaboration. We'll start on that next time.

February 17, 2011

Bragging Rights

A copy of my newest book was waiting on my doorstep this week when I came home from work. There it lay on the mat in a mangled envelope that looked like it had been across the world and back.

Inside, a jewel of a hardcover edition, featuring some smashing cover art. Of course, I'm as prejudiced as a new parent showing off her new baby, but don't you think it looks handsome?

Publication date: April 1, 2011 from Marshall Cavendish

My new pseudonym is C. Aubrey Hall. This book, Crystal Bones, will be out April 1 and launches a young adult trilogy called The Faelin Chronicles.

I just completed the manuscript for the second book at the end of January, which is why some of my blogs have been sporadic lately. Now I'm set to start writing the third book.

But today, I had to share Book One with you.

Crystal Bones is about twins — a boy called Diello and his sister Cynthe – who are half-Fae and half-human. They fit in nowhere except at home. On their thirteenth birthday, their world is shattered by a ruthless goblin king determined to destroy them and everything they care about. It's all because of something secret their parents did long before they're born. They have to draw on their smarts, cleverness, and the scant magical abilities they possess in order to elude the goblins … and survive.

The story world I've created around Diello and Cynthe is based very loosely on a medieval Welsh foundation, with plenty of my own imagination and magical wonders thrown in. Crystal bones refers to Diello's ability to enhance and strengthen the magic of others in use near him. That is, however, by no means all that he and Cynthe can do.

February 13, 2011

Musings

What are writers made of?

Flights of fancy …

Random bits of lyricism …

Dialogue chattering in the back of their skulls …

Anguish as sharp as barbed wire …

Memories — good and bad — woven in strands that stretch across time …

Drive, determination, ambition, and dreams — always dreams …

Drive, determination, ambition, and dreams — always dreams …

The fragility of a bruised rose petal …

The toughness to keep on …

Empathy …

Compassion …

Cruelty …

The belief and wonder of a child …

The ability to wander back in time or leap to the future …

The capacity to hope …

The tendency to despair …

The willingness to gamble …

Enough vanity to publish …

Enough faith to persevere …

Enough doubt to always be asking, Does it work, does it work, does it work?

Where do we come from, we writers?

What shapes us? What molds us? What in our DNA chain spins the wheel of destiny that whispers, Spend your life among words?

How many of us listen to the little voice that entices, luring us through a portal of imagination?

How many of us turn aside at the gate of, "There's no living to be made from it?"

How much talent sputters to a standstill on the stony road of practice?

There are so many barriers, obstacles, and gatekeepers before writers. Some keep marching. They toil up the mountain of craftsmanship. They knock on the door of publication and keep knocking until it opens.

Shakespeare had a patron. We have day-jobs. We find a way to eat so that we can go on plotting and designing characters.

Is it worth it?

As much as breathing.

February 10, 2011

Teamwork

My two Scotties, playing in this week's snow ... they fight over toys, but just let a mouse come by and it's teamwork all the way.

In today's fiction market with the big splashy brand-name authors making headlines, chatting with Oprah or appearing on morning talk shows to promote their latest books, it's easy to think writing success is just random luck.

Are you still sitting around, waiting for inspiration to strike you the way it did J.K. Rowling?

Did you ever think you have to prepare yourself to receive luck?

Writers are a combination of two important qualities: talent and craftsmanship.

The first one you're born with. You may be born with quite a lot. You may be born with a tiny drop.

The second one you gain through hard work and practice. You write a short story a day, like Ray Bradbury did when he was starting out. You write a novel manuscript of, say, 100,000 words — not by wishing but by planting your backside in a chair every day and writing until you type "The End." Then you toss that draft except perhaps for a couple of good scenes and you start over. Learning as you go, improving the story as you go. You practice by facing the myriad challenges of plot and character and rewriting until you're good at it.

You make luck by honing your craft, by listening to your innate story sense, and by letting your talent and craft work together as a team. That way, when the right opportunity comes along, you're ready to receive it.

Photo by Deborah Chester

February 6, 2011

After Despair: Writing Diagnostics X(b)

Wesley in the "Pit of Despair." (Image from THE PRINCESS BRIDE 1987 courtesy of 20th Century Fox)

In the previous entry, I covered climax structure, steps 1 through 4, and left off in the Dark Moment, which I said should never be rushed. Have you waited long enough for what comes next?

STEP 5: The Reversal. Now despite steps 1-4 making it appear as though the protagonist is going to lose, we don't really want that to happen. Most commercial fiction is, after all, about positive endings. So in this next-to-last step of the climax, there's going to be a reversal of some kind that flips the situation.

Image FORT APACHE 1948, directed by John Ford, courtesy of RKO.

In older yarns, the cavalry (or whatever version of deus ex machina) showed up just in the nick of time. However, in today's fiction it's considered a cheat if someone else rescues the protagonist from a tough spot. So the protagonist has to have a trick up her sleeve, or be tougher or more determined than the antagonist, or have sent for help, or have the cell phone on and transmitting the villain's threats to the FBI agents that are standing by, etc.

It is usually necessary for a writer to plant the seeds of the reversal much earlier in the story, so that when it happens the reversal is unforeseen by the reader but entirely plausible. Easy enough to do in revisions.

Example: in Pretty Woman, the reversal comes because Vivian is stronger than Edward. She holds out longer than he can, and he surrenders, realizing that he's sufficiently in love with her to go after her.

Image from ROMANCING THE STONE 1987, 20th Century Fox

In Romancing the Stone, Joan Wilder is grappling with the villain at the edge of the crocodile pit. The reversal comes when she grabs his cigar from his mouth and burns him in the face with it. He releases her, staggers off balance, and falls into the pit. She is not physicially strong enough to overpower him in hand-to-hand fighting, but she's used her wits superbly.

In Star Wars: The Return of the Jedi, Luke's earlier attempts to reach his father finally come to fruition when Darth Vader turns on the Emperor and saves his son's life.

Keep in mind, however, that the reversal will seem cheap without a well-done Dark Moment.

STEP 6: The Reward. This conclusion of the story is sometimes known as the denouement or the wrap-up. It's where poetic justice is handed out, based on what the characters deserve. This stage of story climax is all about making sure fairness prevails.

So how brave or foolish has the protagonist been?

How ruthless has the antagonist been?

What should happen to each of them as the story concludes?

A writer has several options. If the protagonist has grown and improved and risked much during the course of the story and has saved the day, then this character will obtain the story goal plus extra rewards.

Often winning the heart of the love interest is presented as one of the rewards.

If the protagonist managed to save the day but made several mistakes and could have done much better, then the character will obtain the story goal but may lose the love interest or see very little additional reward.

If the protagonist has thrown away chances and trampled over others and devolved as a character, he or she will lose the story goal.

Options for the antagonist are equally varied, but instead of "reward," think in terms of "punishment."

The antagonist is supposed to lose his or her story goal.

If the antagonist is a charming rogue, or helped incidental minor characters, or showed redeeming qualities in the course of the story, then the antagonist will lose the goal but escape capture.

If the antagonist is a villain, he or she will lose the story goal and be punished additionally, perhaps incarcerated or even killed.

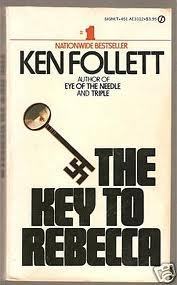

Example: in Ken Follett's WWII thriller, The Key to Rebecca, the hero prevents British plans from falling into Rommel's hands, saves his son's life, and gets the girl. The villain fails to steal the plans and is incarcerated in a tiny, windowless cell where his acute claustrophobia drives him mad.

In Gone with the Wind, Scarlett O'Hara finds out too late that she loves Rhett instead of Ashley and she pays for her many mistakes by failing to stop Rhett from leaving her.

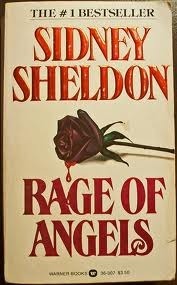

In the Sidney Sheldon novel Rage of Angels, the protagonist survives the climax with her life intact, but because of her mistakes she has lost her integrity, lost her lover, lost her career, lost her son, and is left walking down a snowy street at dusk, with nothing.

Some novels cover these six steps in a couple of scenes separated by a sequel. Others take two, possibly three chapters. Still others, such as the Dick Francis mystery Whip Hand, spend the second half of the novel spanning the climax.

Certainly in the writing of any story, whatever its length, the climax requires revision and possibly several drafts to get everything exactly right. But in terms of evaluating a story premise — which is what this diagnostic series has been about — it's important to look at story climax in terms of being a destination. Chances are in your working synopsis or outline, some of these steps will be rough or vague. Go ahead and sketch them out. They will change and adapt during the actual writing of your rough draft, but thinking ahead through these steps will help you focus on where your story is going. And you are much more likely to get there.

February 2, 2011

Climax Structure: Writing Diagnostics X(a)

There are six steps in creating a classic climax structure, and they're designed to deliver optimal reader entertainment.

STEP 1: The Choice. The protagonist should be boxed in or cornered or confronted by the antagonist. The antagonist has the upper hand and will offer the protagonist a choice of two courses of action. Neither alternative should be good. Even if one of the choices looks attractive, it should come at an extremely high cost.

Example: in the Dick Francis mystery novel, Odds Against, the protagonist is tied up by the villain and threatened with physical torture if he doesn't tell where the incriminating evidence has been hidden. This is a simple either/or kind of choice. If Sid caves in and tells, he may save himself from agony, but the villain will get away with his crime. However, if Sid remains brave and courageously silent, he's going to be beaten with a crowbar.

Never let the choice be an easy one.

STEP 2: The Decision. Often I refer to this as the sacrificial decision because that's what the protagonist should do … surrender something dear. The very definition of hero carries the Greek meaning "sacrifice." So the protagonist may have to sacrifice the story goal, or perhaps his life or reputation.

Example: in the climax to Suzanne Collins's YA novel, The Hunger Games, the protagonist is willing to sacrifice her life.

In Odds Against, the protagonist chooses not to let the villain get away.

STEP 3: Action. Because people are filled with good intentions that they don't always act upon, it isn't enough for the protagonist to intend to do the right thing. Sacrifice is difficult, and at the last moment courage could fail. So it's necessary for the protagonist to take irrevocable action, to burn her bridges, if you will. Then there's no going back.

This is where the protagonist may suddenly spring at the antagonist, initiating a dangerous fight. This is where the protagonist may make a phone call, or verbally refuse the deal offered by the antagonist.

Example: in the film Pretty Woman, Vivian gathers up her clothing and leaves Edward's penthouse suite in the luxurious hotel.

In the Dick Francis novel, Whip Hand, the protagonist activates a tape recorder and asks a witness to share information despite having been threatened with extreme violence if he doesn't drop the investigation.

Whatever the protagonist does, it's going to force the antagonist to carry out what was threatened in The Choice.

STEP 4: The Dark Moment. If a writer is doing her job well, this part of the story should look bleak, perhaps even dire. The story goal should appear lost. The story question should appear to be a no. It should look as though the protagonist has failed. An inexperienced writer will rush the Dark Moment, but a clever writer will not. This agonizing section of suspense is critical to the success of the climax. You must keep your readers enthralled here and not let them pull away.

Example: in the film Pretty Woman, the Dark Moment comes when Vivian and Edward spend their first night apart. They've been unable to agree. Edward wants her to become his mistress. She wants marriage and a committed relationship. She leaves (acting on her sacrificial decision). Her tearful ride back to her apartment shows her Dark Moment. She thinks she's lost the man she's fallen in love with, and she's miserable.

In Odds Against, the Dark Moment occurs while Sid is enduring the beating.

[Steps 5 & 6 will be covered in my next blog.]

January 27, 2011

And furthermore: Writing Diagnostics IX(b)

"Whatever begins, also ends." — Seneca

I'm finding as a writing teacher that fewer and fewer of my students instinctively understand the need for a real story conclusion, much less how it's constructed.

I suppose that's due in part to less reading, the popularity of series fiction, and the current way many television episodes are being written. In TV, story arcs now span whole seasons or even cover the entire duration of the show instead of episodes standing separately. As a result of this trend, TV characters may be more complex and dimensional than in the past, but they never finish much either. Some shows offer a semi-climax at the end of a season, but then leave questions hanging to bridge viewers to the next season. These hooks are effective in keeping viewers loyal to the show, and are similar to what authors of series novels do, but they don't provide true endings. Other shows resolve a weekly subplot. My point is not to criticize TV, but to observe that viewers are exposed to fewer conclusive, climatic endings than before.

If you're a fan of the Robert Jordan franchise of fantasy novels, you're probably more into process than result. You don't want the story to end, do you? So the series goes on and on and on …

But suppose you aren't the creator of a hit television series like THE GOOD WIFE or BURN NOTICE. Suppose you aren't Robert Jordan or Jim Butcher, with a highly successful series of novels.

Let's say instead that you're a writer trying to put a short story together. Or you're a novelist trying to plan and plot a 300-page science fiction yarn about hostile aliens invading a prosperous colony world.

In such cases, you have to know that your protagonist will be the one to resolve the problem. You need to be trying to figure out how. You also need to know where your protagonist and antagonist are going to clash in a big finale.

In a stand-alone story or novel, you're responsible for supplying an ending that's complete by resolving the emotional issues as well as the central story question; providing readers with a cathartic experience; answering all the questions that were raised in the plot; and — most importantly — leaving a reader convinced that she got her money's worth.

Exactly how is all that accomplished?

Stay tuned ….

C. Aubrey Hall's Blog

- C. Aubrey Hall's profile

- 7 followers