Kenneth Atchity's Blog, page 173

February 19, 2015

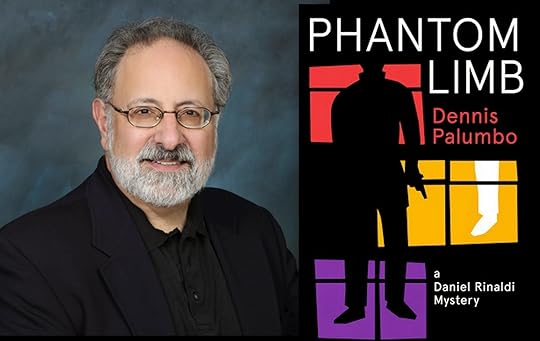

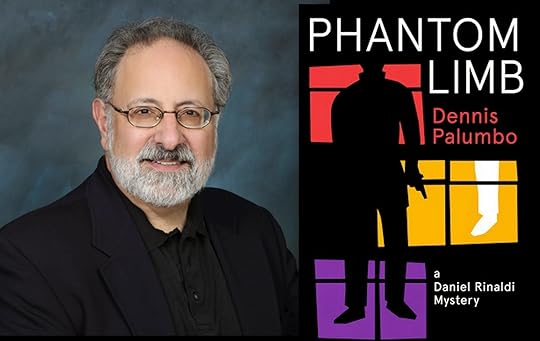

My Book, The Movie: Dennis Palumbo's Phantom Limb

Formerly a Hollywood screenwriter (My Favorite Year; Welcome Back, Kotter, etc.), Dennis Palumbo is now a licensed psychotherapist and author. His mystery fiction has appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, The Strand and elsewhere, and is collected in From Crime to Crime (Tallfellow Press). His acclaimed series of crime novels (Mirror Image, Fever Dream, Night Terrors and the latest,

Phantom Limb

) feature psychologist Daniel Rinaldi, a trauma expert who consults with the Pittsburgh Police.

Here Palumbo dreamcasts an adaptation of Phantom Limb:

As before, regarding my previous Daniel Rinaldi novel, Night Terrors, I still favor Anthony LaPaglia for the lead role in the movie version of my latest, Phantom Limb. He’d be perfect for the driven psychologist who consults with the Pittsburgh Police. But I could also see Robert Downey, Jr., for his mixture of intelligence and wry humor. Plus, now that he’s gotten into super-hero shape, I could believe he’s both a veteran therapist and a former amateur boxer.

For the role of Lisa Campbell, one-time Playboy Playmate turned Hollywood horror movie scream-queen, and now a mature woman unhappily married to a ruthless tycoon, my first choice would be Susan Sarandon. She has just the right combination of seasoned sexuality and smart-ass attitude. I think Sharon Stone would also fit the bill quite nicely.

Lastly, for the role of one of the main bad guys, an emaciated, bone-thin black sheep of a wealthy family, I envision the indie director John Waters. While not primarily an actor, he’d be perfect for the cunning, sleepy-eyed Ray “Splinter” Sykes. Though Crispin Glover would also be fine. Or Billy Bob Thornton.

Learn more about the book and author at Dennis Palumbo's website.

My Book, The Movie: Night Terrors.

The Page 69 Test: Phantom Limb.

Reposted from America Reads--Marshal Zeringue

Here Palumbo dreamcasts an adaptation of Phantom Limb:

As before, regarding my previous Daniel Rinaldi novel, Night Terrors, I still favor Anthony LaPaglia for the lead role in the movie version of my latest, Phantom Limb. He’d be perfect for the driven psychologist who consults with the Pittsburgh Police. But I could also see Robert Downey, Jr., for his mixture of intelligence and wry humor. Plus, now that he’s gotten into super-hero shape, I could believe he’s both a veteran therapist and a former amateur boxer.

For the role of Lisa Campbell, one-time Playboy Playmate turned Hollywood horror movie scream-queen, and now a mature woman unhappily married to a ruthless tycoon, my first choice would be Susan Sarandon. She has just the right combination of seasoned sexuality and smart-ass attitude. I think Sharon Stone would also fit the bill quite nicely.

Lastly, for the role of one of the main bad guys, an emaciated, bone-thin black sheep of a wealthy family, I envision the indie director John Waters. While not primarily an actor, he’d be perfect for the cunning, sleepy-eyed Ray “Splinter” Sykes. Though Crispin Glover would also be fine. Or Billy Bob Thornton.

Learn more about the book and author at Dennis Palumbo's website.

My Book, The Movie: Night Terrors.

The Page 69 Test: Phantom Limb.

Reposted from America Reads--Marshal Zeringue

Published on February 19, 2015 00:00

February 18, 2015

To friends in Pasadena-Altadena

Enjoy a rowdy and relaxing evening with my friend and tennis buddy Don Raymond on MARCH 1 at 7 p.m. At the Coffee Gallery Backstage – 2029 N. Lake Altadena CA 91001

I’m planning to be there and would love to see you too!

http://www.coffeegallery.com/showsat.htm

Published on February 18, 2015 00:00

February 16, 2015

New book reveals the story of the lawyer who was one of the last US soldiers to leave Vietnam

Pena (left) and Hagan, ABA Midyear Meeting in Houston. Photo by Kathy Anderson.In 2003, Richard Pena was on his second tour in Vietnam, leading a delegation from the People to People Ambassador Program. During a visit to the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City (the former Saigon), he looked at a photo depicting a line of American troops boarding an airplane between rows of North Vietnamese soldiers. In the middle of the photo was a young American soldier carrying a briefcase. That soldier was Pena, and he vividly remembered the scene that unfolded 20 years earlier.

Pena (left) and Hagan, ABA Midyear Meeting in Houston. Photo by Kathy Anderson.In 2003, Richard Pena was on his second tour in Vietnam, leading a delegation from the People to People Ambassador Program. During a visit to the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City (the former Saigon), he looked at a photo depicting a line of American troops boarding an airplane between rows of North Vietnamese soldiers. In the middle of the photo was a young American soldier carrying a briefcase. That soldier was Pena, and he vividly remembered the scene that unfolded 20 years earlier.Pena had used the briefcase during his first year in law school at the University of Texas, but his legal education was cut short when he was drafted in 1970 and then slated for duty in Vietnam—not as a legal clerk, as he expected, but as a medical technician in the operating room of the last U.S. military hospital still open as this country’s involvement in the war wound down in the early 1970s.

“That briefcase was my security blanket in Vietnam,” said Pena today at a book-signing reception for Last Plane Out of Saigon, which Pena and co-author John Hagan published in 2014 through Story Merchant Books in Beverly Hills, California. The reception was sponsored by the American Bar Foundation, where Hagan is co-director of the Center of Law & Globalization, during the 2015 ABA Midyear Meeting in Houston.

In addition to the comfort he got from a seemingly mundane item from home like a briefcase—clearly, Pena was a lawyer at heart even then—he also kept a journal to help him through the lunacy of the closing days of the U.S. military’s involvement in Vietnam. The journal entries touch on a variety of topics, including Pena’s experiences at the hospital, political musings and personal reflections. “It gave my real impressions on the ground of the war and my feelings about it,” he said at the book-signing reception.

Interspersed with those entries—left largely intact 41 years after they were written—are chapters by Hagan that put the war in the context of events in the United States and around the world.

At the heart of the book is Pena’s account of that flight out of Saigon in March 1973, when he was one of the very last U.S. troops to leave the country. Two years later, the United States made its final exit when military helicopters rescued diplomatic personnel, along with a handful of Vietnamese, off the roof of the U.S. embassy. While images of that chaotic departure are familiar to Americans—Rory Kennedy’s film The Last Days in Vietnam is an Oscar nominee for best documentary film—the photo of Pena and his comrades boarding the plane is iconic to the Vietnamese.

Pena’s return to the United States and civilian life was not easy. “I was angry,” he said. “I was angry the whole time after I got back. It did pass, but I was cold. I had my walls up.”

Pena returned to law school at the University of Texas, where he received his J.D. in 1976, then went into practice in Austin, where he represents plaintiffs in personal injury and workers compensation cases. He also went on to serve as president of the Austin Bar Association, the State Bar of Texas and the American Bar Foundation, and he served on the ABA’s Board of Governors. He believes his military experience made him a better, tougher lawyer. “I don’t care what people say. What are they going to do, send me back to Vietnam?”

But Pena said his time in Vietnam also left him skeptical about America’s military involvement in more recent wars, especially in the Middle East, and he sees a tough road ahead for many veterans of those conflicts. “War is war,” he said. “It’s an insane existence, and the whole game is to survive, both physically and mentally.” Citing high rates of suicide, post-traumatic stress disorder and addiction among veterans returning from wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Pena said, “My only advice is, ‘hold it and roll.’ That means do the best you can. Tomorrow may be a better day.”

Last Plane Out of Saigon

by Richard Pena & John Hagan

Reposted from ABA Journal

Published on February 16, 2015 00:00

February 13, 2015

Guest post on ON WRITING by Jerry Amernic, Author of The Last Witness

As part of his blog tour, Jerry Amernic has asked to come by to write a guest post about how he conducted his research for his latest book The Last Witness. It should make for an interesting read!

My novel The Last Witness is about the last living survivor of the Holocaust in the year 2039. The central character, Jack Fisher, is a 100-year-old man whose worst memories took place before he was 5, but he’s caught in a world that is abysmally ignorant and complacent about events of the last century.

Of course, a writer can research any historical event to his heart’s content and read everything about it. But for a subject like the Holocaust I thought it best to actually sit down with former child survivors. And I did.

A group meets regularly in Toronto where I live. I attended some of their meetings and also visited several of them in their homes.

Miriam, now 79, was one of only two dozen children who were found alive at Auschwitz when the place was liberated by the Red Army in 1945. She was nine. She told me about the trains that carried Jews to the death camp – with no windows or place to relieve yourself. She told me about old people who became corpses on the trip. She told me about seeing murders every day.

Gershon, who was only 3 at the time of liberation by U. S. troops, doesn’t remember much. Today he’s a grandfather and has been married to the same woman for decades. But he told me that throughout his whole life he has always been claustrophobic in tight quarters, and he also lives with this fear that those who are closest to him – even his wife – will leave him one day. Because everybody else did when he was little.

Imagine carrying a burden like that around with you.

So, through people like them, I learned something about what it was like to be a child survivor of the Holocaust.

I also made a point of meeting notable people. Like Sir Martin Gilbert. The official biographer of Winston Churchill, Mr. Gilbert is an eminent historian and author of some 70 books, including The Holocaust. He was most helpful and kind.

But most of my research involved finding specifics about what I needed, which meant reading. For example, my character Jack was born in the Jewish ghetto in the city of Lodz, Poland. He was a hidden child because if the Nazis found him, they would have taken him from his family. I learned how little children sneaked into the Aryan side of the city to steal food for their family. I learned about families living in the sewers below the streets to try and avoid detection. Indeed, I read whatever I could find about that Jewish ghetto and about Auschwitz – where my flashbacks are based.

It was an experience and a journey, and I only hope this novel is the same for my readers.

About the book

The year is 2039, and Jack Fisher is the last living survivor of the Holocaust. Set in a world that is abysmally ignorant and complacent about events of the last century, Jack is a 100-year-old man whose worst memories took place before he was 5. His story hearkens back to the Jewish ghetto of his birth and to Auschwitz where, as a little boy, he had to fend for himself to survive after losing all his family. Jack becomes the central figure in a missing-person investigation when his granddaughter suddenly disappears. While assisting police, he finds himself in danger and must reach into the darkest corners of his memory to come out alive. The Last Witness on Amazon Note from the Author My research included spending time with real-life, former child survivors. To illustrate the point of this novel, we produced a video and went around asking university students in Toronto where I live what they know about the Holocaust and World War II. The level of ignorance out there is incredible. Have a look here. Reposted from On Writing

The year is 2039, and Jack Fisher is the last living survivor of the Holocaust. Set in a world that is abysmally ignorant and complacent about events of the last century, Jack is a 100-year-old man whose worst memories took place before he was 5. His story hearkens back to the Jewish ghetto of his birth and to Auschwitz where, as a little boy, he had to fend for himself to survive after losing all his family. Jack becomes the central figure in a missing-person investigation when his granddaughter suddenly disappears. While assisting police, he finds himself in danger and must reach into the darkest corners of his memory to come out alive. The Last Witness on Amazon Note from the Author My research included spending time with real-life, former child survivors. To illustrate the point of this novel, we produced a video and went around asking university students in Toronto where I live what they know about the Holocaust and World War II. The level of ignorance out there is incredible. Have a look here. Reposted from On Writing

Published on February 13, 2015 00:00

February 12, 2015

Miki's Hope Reviews Ian Bull's The Picture Kills

Steven Quintana, an ex Army Ranger reconnaissance photographer witnesses something happen while on a mission which he can't get out of his head--recurring nightmares stalk him. He is still a photographer but now is one of the paparazzi getting photos of movie stars in California and being paid really good money for it. He has saved up almost enough to retire when he is offered a really huge amount to get one more photo of Julia Travers, a up and coming movie star. The last photo he managed to get of her she managed to kick him in the mouth hard enough to break a tooth! He just can't say no to the amount of money he is being offered for just one picture. He gets the picture and it is all too easy. That is when all hell breaks loose. Steven looks at the picture and realizes there is something wrong. He can not let it go and decides to follow up.

Then starts the non stop action--Julia is definitely not a dumb woman and Steven has abilities that are unreal. The bad guys are really bad!! This is the first book in a three book series and yes, at some point I will have to get the second and the third to see what happens next!

About the Book: (from Amazon)

When you’re covered in mud, running from men with guns, and stuck in small spaces with very little clothing on, it’s amazing what you can learn about a person.

Steven Quintana was once a top Army Ranger reconnaissance photographer until he made a fatal mistake on a mission. A boy was killed, and Steven’s military career was cut short—all because of a photo he took.

Now he works as a paparazzo in Hollywood where his photos can’t hurt anybody, the money is easy, and he can forget the past.

But when mega movie star Julia Travers is kidnapped, Steven discovers the kidnappers used photos he took to cover up the crime. Realizing that he’s still harming people with his camera, he swears to fix his mistake, Rambo-style.

But—life or death situation or not—the last person Julia wants coming to her rescue is the paparazzo whose photos got her into trouble in the first place.

THE PICTURE KILLS is a fun, fresh, sexy, snappy, fast-paced thriller that starts in celebrity-obsessed Hollywood and climaxes in the exotic and remote cays of the Bahamas.

Excerpt:

“Run, Julia!” someone shouts.

Julia bolts across the patio with her white robe flapping, swim fins in one hand and a canvas bag in the other. She slows to pick up the French Smoker’s gun and then leaps over the first wall.

I feel a bullet whizz past my cheek and then hear the gun-shot. I jump over the wall as more shots ring out. People shout as I disappear into the trees.

I have to move fast, both to escape Caballero and his friends but to also catch Julia.

The shouting continues for a bit and then stops, but I hear enough branches cracking and electronic chirps to know that four men are behind me. I keep searching for Julia while evading them. I notice a flash of white and head for it, and find her robe stuck in a tree. Smart girl, I think. I toss it in the high grass so they can’t find it.

Her trail is easy to find now. I pause every hundred yards and wait until I hear a small thud or crack in front of me, and then I head there until I find her trail again.

Then I reach the fisherman’s hut and the bent grass blades tell me she went inside. Not such a smart girl after all.

Creeping around the side, I find the closed door. “Julia,” I whisper.

There’s no answer, so I push the door open and step in-side. It’s pitch black. I pull a glow stick out of a pocket in my camo pants and crack it, letting the light leak through my knuckles.

Crouching in the corner next to the open window, she’s wearing a bikini, a man’s suit jacket and deck shoes that are too big, and her legs are scratched from running through the woods. She has her canvas bag in one hand and the French Smoker’s gun in the other.

She’s breathing hard, and then our eyes lock and she gasps. In five seconds a half dozen emotions flash across her face: fear…slight recognition…then confusion…then she really remembers who I am…and her face fills with anger.

It’s the same anger I saw ten days ago when I last stared at her eye-to-eye, when she knocked out my tooth with her foot. She raises the gun and aims it right at my heart.

“I hate you, you asshole.”

“Wait!” I yell.

The door next to me bursts open just as she pulls the trigger.

Purchase the Book Here

Ian Bull is the pen name of Donald Ian Bull, a TV producer turned thriller novelist. The Picture Kills is his first book, and the sequel, Six Passengers, Five Parachutes, will be out in 2015. Both feature former army reconnaissance photographer Steven Quintana and movie star Julia Travers.

Ian Bull is the pen name of Donald Ian Bull, a TV producer turned thriller novelist. The Picture Kills is his first book, and the sequel, Six Passengers, Five Parachutes, will be out in 2015. Both feature former army reconnaissance photographer Steven Quintana and movie star Julia Travers.Donald Ian Bull also wrote The Reality Director and Producer Guidebook, which teaches you how to direct true documentaries for television, without needing to add the word "reality" in quotes. He also writes a blog called CaliforniaBull, about growing up, living, working, and raising a family in California.

You can check out his work at IanBullAuthor.com, IntersectionProductions.com and CaliforniaBull.com.

He also gives kudos to his editors and publishers, Lisa Cerasoli and Ken Atchity of Story Merchant.

He grew up in San Francisco, attended UC Berkeley and then UCLA, and now lives in Los Angeles with his wife and daughter.

Authors Website

Goodreads

Reposted from Miki's Hope

Published on February 12, 2015 00:00

February 11, 2015

Special Reception for Richard Pena and John Hagan's Last Plane Out of Saigon

This past Friday, February 21, 2015, Richard Pena and co-author John Hagan traveled to Houston, TX to the American Bar Association's (ABA) Annual Meeting. The American Bar Foundation (ABF) put on a special reception for select guests, which featured the book as well as the two authors. This is the first time that Pena and Hagan have been together to talk about the book and share the details of how it came about. Upwards of 50 people attended the event and it was such an honor and joy to be able to share this story with those who attended. Click HERE to view the write up on the ABA Journal's website about the event!

This past Friday, February 21, 2015, Richard Pena and co-author John Hagan traveled to Houston, TX to the American Bar Association's (ABA) Annual Meeting. The American Bar Foundation (ABF) put on a special reception for select guests, which featured the book as well as the two authors. This is the first time that Pena and Hagan have been together to talk about the book and share the details of how it came about. Upwards of 50 people attended the event and it was such an honor and joy to be able to share this story with those who attended. Click HERE to view the write up on the ABA Journal's website about the event!

Last Plane Out of Saigon

by Richard Pena & John Hagan

Published on February 11, 2015 18:40

February 9, 2015

Dennis Palumbo Interviewed in the February Issue of Suspense Magazine

Published on February 09, 2015 00:00

February 6, 2015

Guest Post: Remembering Holocaust historian Sir Martin Gilbert and his ‘two Londons’ by Jerry Amernic

APPRECIATION

He didn’t have to be helpful. He didn’t know me or anything about me, only that I had an idea for a novel about the last living survivor of the Holocaust, and wanted to speak to him. He was intrigued, so he agreed to sit down with me after his lecture at the University of Western Ontario in London. Make that London, Ontario, a Canadian city of 350,000 people 120 miles west of Toronto.

Sir Martin Gilbert, who just passed away at the age of 78, was one of the world’s eminent historians and quite likely the leading chronicler of the worst human catastrophe we have ever seen. The official biographer of Winston Churchill and author of some 88 books, many of them on the two World Wars and Jewish history, he had been knighted in 1995 for “services to British history and international relations.” His epic work, “The Holocaust—A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War,” a book of almost 1,000 pages that I read and reread and marked up with highlighter and post-it notes ad infinitum, was what finally moved me from the research phase into the actual writing of my own book. The only other book of history that had such an effect on me was probably William Shirer’s “The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich.”

I had the pleasure of meeting Sir Martin on three occasions, the first time at the university in London. He said that he lived in two Londons—London, England, and London, Ontario, where he was a guest lecturer. There we were, along with his wife Esther, sitting in a university cafeteria, surrounded by a throng of students who didn’t seem to know him from Adam. I told him about my premise—a novel set in the near future about a 100-year-old Holocaust survivor who is caught in a world that is woefully ignorant of the past century.

Did he think it far-fetched? No, not at all. And then he offered me this tidbit: “Why don’t you have an event in the year 2030 that would eclipse the Holocaust?”

Hmm. What a thought. And that’s exactly what I did.

Gilbert’s book, the quintessential treatise on the genocide of Jews during World War II, should be required reading for any history course on the 20th century. His website describes it this way: “A comprehensive history of the Holocaust, stressing the human aspect, and telling the story of the deliberate murder of six million men, women and children through the words and experiences both of the murderers and of their victims.”

In typical Martin Gilbert fashion, the book also includes “34 photographs and 23 maps, each map specially prepared by the author to locate every place mentioned in the book, and every phase of the Holocaust.”

To call him meticulous would be an understatement.

Of course, he also wrote other books like “The Righteous—The Unsung Heroes of the Holocaust,” an examination of non-Jews in Europe who risked their lives to help save Jews. Churchill aside, he wrote biographies on such dignitaries as Lloyd George and Anatoly Shcharansky, and in addition to Jewish history, he wrote books about British history and European history. He also put together vast collections of photographs, documents, maps, and letters that would more than arm any prosecutor in a modern-day Nuremberg trial.

The contribution this man made to history is beyond measure. He wrote about Soviet refuseniks and was known to be a devout Zionist, but he was also part of a not-for-profit think tank committed to improving conditions for Palestinians on the West Bank. A master documenter of events who would leave no stone unturned, he brought a sense of purpose and balance to everything he wrote.

I still have the emails he sent me in response to my question about finding former child survivors of the Holocaust. He was quick to provide names and organizations. More recently, he was in town to do a book signing for “Will of the People—Winston Churchill and Parliamentary Democracy,” and asked how my novel was proceeding.

The third time I saw Gilbert was when I attended a lecture in which he talked about his childhood, and how he was evacuated to Canada during the war when he was 4 years old. I brought my wife and daughter along to that one. He said he always had a soft spot in his heart for Canada.

Sir Martin Gilbert mixed with opera stars like Placido Domingo, and he knew a number of world leaders, presidents, and prime ministers alike. Gordon Brown, when he was prime minister of Great Britain, had asked him to serve on a task force looking into the Iraq war. While comfortable in these circles, he was also a most generous man, and I had the pleasure of learning that first-hand.

He will be missed.

Jerry Amernic is a Canadian writer of fiction and non-fiction books. He is the author of the new Holocaust-related novel “The Last Witness.”

Jerry Amernic is a Canadian writer of fiction and non-fiction books. He is the author of the new Holocaust-related novel “The Last Witness.”

Reposted from JNS.org

He didn’t have to be helpful. He didn’t know me or anything about me, only that I had an idea for a novel about the last living survivor of the Holocaust, and wanted to speak to him. He was intrigued, so he agreed to sit down with me after his lecture at the University of Western Ontario in London. Make that London, Ontario, a Canadian city of 350,000 people 120 miles west of Toronto.

Sir Martin Gilbert, who just passed away at the age of 78, was one of the world’s eminent historians and quite likely the leading chronicler of the worst human catastrophe we have ever seen. The official biographer of Winston Churchill and author of some 88 books, many of them on the two World Wars and Jewish history, he had been knighted in 1995 for “services to British history and international relations.” His epic work, “The Holocaust—A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War,” a book of almost 1,000 pages that I read and reread and marked up with highlighter and post-it notes ad infinitum, was what finally moved me from the research phase into the actual writing of my own book. The only other book of history that had such an effect on me was probably William Shirer’s “The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich.”

I had the pleasure of meeting Sir Martin on three occasions, the first time at the university in London. He said that he lived in two Londons—London, England, and London, Ontario, where he was a guest lecturer. There we were, along with his wife Esther, sitting in a university cafeteria, surrounded by a throng of students who didn’t seem to know him from Adam. I told him about my premise—a novel set in the near future about a 100-year-old Holocaust survivor who is caught in a world that is woefully ignorant of the past century.

Did he think it far-fetched? No, not at all. And then he offered me this tidbit: “Why don’t you have an event in the year 2030 that would eclipse the Holocaust?”

Hmm. What a thought. And that’s exactly what I did.

Gilbert’s book, the quintessential treatise on the genocide of Jews during World War II, should be required reading for any history course on the 20th century. His website describes it this way: “A comprehensive history of the Holocaust, stressing the human aspect, and telling the story of the deliberate murder of six million men, women and children through the words and experiences both of the murderers and of their victims.”

In typical Martin Gilbert fashion, the book also includes “34 photographs and 23 maps, each map specially prepared by the author to locate every place mentioned in the book, and every phase of the Holocaust.”

To call him meticulous would be an understatement.

Of course, he also wrote other books like “The Righteous—The Unsung Heroes of the Holocaust,” an examination of non-Jews in Europe who risked their lives to help save Jews. Churchill aside, he wrote biographies on such dignitaries as Lloyd George and Anatoly Shcharansky, and in addition to Jewish history, he wrote books about British history and European history. He also put together vast collections of photographs, documents, maps, and letters that would more than arm any prosecutor in a modern-day Nuremberg trial.

The contribution this man made to history is beyond measure. He wrote about Soviet refuseniks and was known to be a devout Zionist, but he was also part of a not-for-profit think tank committed to improving conditions for Palestinians on the West Bank. A master documenter of events who would leave no stone unturned, he brought a sense of purpose and balance to everything he wrote.

I still have the emails he sent me in response to my question about finding former child survivors of the Holocaust. He was quick to provide names and organizations. More recently, he was in town to do a book signing for “Will of the People—Winston Churchill and Parliamentary Democracy,” and asked how my novel was proceeding.

The third time I saw Gilbert was when I attended a lecture in which he talked about his childhood, and how he was evacuated to Canada during the war when he was 4 years old. I brought my wife and daughter along to that one. He said he always had a soft spot in his heart for Canada.

Sir Martin Gilbert mixed with opera stars like Placido Domingo, and he knew a number of world leaders, presidents, and prime ministers alike. Gordon Brown, when he was prime minister of Great Britain, had asked him to serve on a task force looking into the Iraq war. While comfortable in these circles, he was also a most generous man, and I had the pleasure of learning that first-hand.

He will be missed.

Jerry Amernic is a Canadian writer of fiction and non-fiction books. He is the author of the new Holocaust-related novel “The Last Witness.”

Jerry Amernic is a Canadian writer of fiction and non-fiction books. He is the author of the new Holocaust-related novel “The Last Witness.”Reposted from JNS.org

Published on February 06, 2015 00:00

February 4, 2015

Follow Your Dreams

You can estimate the ROI of marketing expenses ONLY when you succeed in getting your sales to the point of success--NOT BEFORE. I see analyses everywhere that use the words "return on investment." In the riskiest career in the world--the creative career--you can't imply the cold numeral logic used in less-risky careers.

Successful artists--writers, ballerinas, painters, singers--have virtually unlimited upsides, and are among the richest people on the planet (consider Oprah, George Clooney, Michael Chrichton, etc. They did not get that way by figuring out ratios. They got that way through sheer determination and persistence, based on a decision to never give up until their dreams come true. Most of the ones I know not only gave EVERYTHING they had to their careers, but went deeply into debt to achieve success.

So, please, if you are determined to use the beancounter's approach to writing, go write business manuals for a big corporation. I give this speech every day all day: Marketing does NOT lead directly to sales. It leads to VISIBILITY. BUT, no visibility, no sales. So focus not on R.O.I. but on provable visibility. Let your destiny take care of the rest. If you don't have the stomach for this, KEEP YOUR DAY JOB.

Published on February 04, 2015 11:31

February 2, 2015

Guest Post: Special to the Big Thrill: The Importance of the Historical Thriller by Jerry Amernic

From my observations, people, especially the young, are surprisingly ignorant of history. When I taught writing courses to college students, I was dumbfounded by how little they know about historical events.

That got me thinking about some important periods in history, and what a travesty it would be if they were forgotten, only to suffer the risk of history, as they say, repeating itself. Thus became THE LAST WITNESS, a novel about the last living survivor of the Holocaust. In the book, the character’s one hundredth birthday takes place in 2039, but the world has all but forgotten.

Like many novels, it was first turned down by various publishers, one of whom said he had to “suspend disbelief” with the premise that people would know so little about the Holocaust a mere one generation down the road.

Really?

To prove my point, I decided to make a video—but not your regular, book-promo thing. I had a mission. A videographer and I spent an afternoon asking university students in Toronto, where I live, what they know about the Holocaust. And since this was a few days before November 11th, we also asked them about World War II.

What did we find? Many students didn’t know what happened at the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, who FDR and Churchill were, or what the Holocaust was all about. “I’ve heard of the Holocaust but I can’t explain it,” one student said. When I asked how many Jews were killed, another said, “thousands”—which is a far cry from six million.

Not a single student knew what The Final Solution was, or had heard of Joseph Mengele, and most had no idea who the Allies were, and yet, our video was shot just before November 11th—Remembrance Day in Canada, Veterans Day in the United States. It made me wonder: What would a veteran who stormed the beaches of Normandy with Allied forces on June 6th, 1944 think knowing that university kids today know nothing about what happened that day?

I don’t blame the kids. They are The Lost Generation when it comes to history, victims of a school system that no longer teaches it. This is a big problem in Canada, the U.S., Great Britain, and other countries. As a result, I don’t think it’s such a stretch to create a world in 2039 where rampant ignorance abounds about seminal events.

My research for THE LAST WITNESS began long before we shot that video. Several chapters in the novel contain flashbacks with my protagonist, a hidden child in the Jewish ghetto of his birth, and later, as a little boy at the death camp —Auschwitz— where all his family is lost. He is the only one who survives. But there was little point writing a historical thriller about a subject like this without meeting real-life, child survivors. So I did.

My research for THE LAST WITNESS began long before we shot that video. Several chapters in the novel contain flashbacks with my protagonist, a hidden child in the Jewish ghetto of his birth, and later, as a little boy at the death camp —Auschwitz— where all his family is lost. He is the only one who survives. But there was little point writing a historical thriller about a subject like this without meeting real-life, child survivors. So I did.Gershon Willinger was three years old when liberated by U.S. soldiers from a concentration camp in 1945. Like the character in my novel, he was the only one in his family who made it out. He doesn’t remember much, but for his entire life he’s felt claustrophobic in tight closed spaces, and he harbors a fear that those closest to him—even his wife—will leave him. Today, he’s a grandfather who lives just north of Toronto.

Did Gershon think my premise about the world not knowing much about the Holocaust in 2039 was far-fetched? No. In fact, not one survivor I met thought so. Miriam Ziegler was nine when liberated by the Red Army at Auschwitz. There is a photo of children standing behind a barbed-wire fence on the day they were freed, and Miriam is in it. She doesn’t like to talk about her experiences, but they’re seared into her memory, including that of the infamous Joseph Mengele, the Nazi doctor who performed twisted tests on children, especially twins. Miriam remembers seeing him walking around all the time. “The man in charge,” she said.

Some former child survivors readily go into schools to speak about their experiences. One of them, Elly Gotz, spent three years as a teenager in the Jewish ghetto in Vilnius, Lithuania. When he and his parents had given up hope and were about to commit suicide, they were freed, and all three survived. Today, Elly is a robust eighty-five-year-old who lectures at schools and for other groups. He even helped prepare videotaped testimonies of 450 Holocaust survivors, and has been honored for his work by the Government of Ontario. Elly was invaluable to me when I asked him to fact-check my historical flashbacks about life in the ghetto.

As a writer who is a stickler for accuracy—that goes for historical novels, too—I don’t like to bend history. My initial plan was to write about the Warsaw ghetto, the biggest Jewish ghetto of all, and follow my character as he got caught up in the Warsaw ghetto uprising, a signature event in World War II where Jews rose up to fight their Nazi oppressors. But when I discovered no Jews from Warsaw went to Auschwitz, I abandoned that idea.

The next biggest ghetto was in Lodz, Poland. Thousands of Jews were moved from there to Auschwitz, so I read everything I could find about the Lodz ghetto. I learned how children sneaked over the wall that divided the Aryan side from the Jewish ghetto to steal food for their family, how countless Jews lived in sewers below the city to stave off capture, and how they were transported like cattle—worse than cattle—in cold vile trains to the death camp.

All this became part of THE LAST WITNESS, but the book didn’t start out as a thriller. It was meant to be a commentary on how society is becoming historically illiterate, but I also wanted it to be a novel that would make you read from one page to the next.

In the story, my 100-year-old character becomes crucial to a missing-person investigation when his great-granddaughter, a schoolteacher, suddenly disappears. Thus, there are two story lines— the modern or near-future story, and the flashbacks about his life as a little boy trying to survive in what can only be described as hell.

Still, the book was missing something—pacing, or as writers like to say, it needed legs. I rectified that by making the NYPD detective involved in the missing-person investigation a much stronger character than he was in earlier drafts. Not only does he become the face of the larger society that has much to learn about what happened to European Jews in the 1940s, but he is larger than life at 6’5” and 330 pounds. I also threw in some neo-Nazis who make things interesting, and tightened the book up with a few final edits.

At the end of the day, the job of a thriller writer is to make the story believable and credible for the readers, and to keep those readers on the edge of their seats. Writers do this in different ways, but for me, weaving back and forth between the past and present (or in this case, the near future) is one way to tell a tale. I definitely learned a lot in this project, especially through those former child survivors, and hopefully my reader will too.

For more information, go to THE LAST WITNESS. The book is available on Amazon. You can see Jerry Amernic’s video with the university students here.

*****

Jerry Amernic is a writer who lives in Toronto. He has been a newspaper reporter and correspondent, newspaper columnist, feature writer for magazines, teacher of journalism, and media consultant. His most recent novel is The Last Witness, which is about the last living survivor of the Holocaust in the year 2039. Soon to be released is his biblical-historical thriller QUMRAN. Jerry’s first novel, Gift of the Bambino, was published in 2004 and will soon be re-released as an e-book.

Jerry Amernic is a writer who lives in Toronto. He has been a newspaper reporter and correspondent, newspaper columnist, feature writer for magazines, teacher of journalism, and media consultant. His most recent novel is The Last Witness, which is about the last living survivor of the Holocaust in the year 2039. Soon to be released is his biblical-historical thriller QUMRAN. Jerry’s first novel, Gift of the Bambino, was published in 2004 and will soon be re-released as an e-book.To learn more about Jerry, please visit his website and follow him on Facebook.

Reposted from The Big Thrill

Published on February 02, 2015 00:00