Kenneth Atchity's Blog, page 239

April 28, 2012

Maggie Gyllenhaal Talks Sex Scenes

Tribeca: Maggie Gyllenhaal on Sex

Scenes From a Woman’s Perspective

By JULIE BLOOM

Maggie Gyllenhaal as Charlotte Dalrymple.

Ricardo Vaz Palma, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

“The plague of our times,” a character declares in “Hysteria,”

Tanya Wexler’s new film, “stems from an overactive uterus.” The time is

Victorian England and the focus is the invention of the vibrator. The

romantic comedy, which plays at the Tribeca Film Festival on Thursday

and opens commercially on May 18, stars Hugh Dancy as Mortimer, a

forward-thinking doctor, and Maggie Gyllenhaal as Charlotte, a champion

of women’s rights and the rebellious daughter of Mr. Dancy’s mentor, as

well as his romantic match.

Tribeca Film Festival

Though its period detail and depiction of naïve men trying to “cure”

hysterical women through womb massage seems hilariously out of date,

there are moments when issues of women’s rights raised (lightly) in the

film feel surprisingly relevant. We spoke with Ms. Gyllenhaal by

telephone about “Hysteria” and why there are still so few good sex

scenes. Here are edited excerpts from the conversation:

Q.

Do

you think the light tone makes a movie about female sexuality more

palatable? Why are there so few good movies about the subject?

A.

I’ve

talked to so many people about this. I’ve been interviewed about this

all over the world and because of how they finance movies now, I’ve

talked to women in Norway and Italy and Finland, Spain and all these

women kind of say the same thing, which is there aren’t a lot of movies

like this. And why is it even in all those different cultures where

they’re not particularly prudish and open to talking about female

sexuality? Why, when they watch the movie, is there a kind of hysteria?

When I saw it in Toronto, people were laughing in this kind of

hysterical way, like, oh my God, an orgasm — and me, too, in a way. I

hadn’t been around for the orgasm stuff because Charlotte doesn’t get

the chance with the vibrator, and so I hadn’t seen it and I had the same

feeling, I got a little flushed and I got a little shy.

Q.

Why is sex still such a complicated thing to tackle on film?

A.

I’ve

thought a lot about women in movies and sex and sex scenes. The

question is why, if half of the adult population is women who have sex,

why is it difficult to see? I personally think this doesn’t necessarily

account for this movie, but the most interesting sex scenes that I’ve

done or seen are the ones that are truthful from a women’s perspective —

instead of what I think everybody got used to in the ’80s and ’90s: put

on a black Victoria’s Secret demi bra and be lit perfectly and arch

your back. That’s supposed to look like sex. But that doesn’t look like

sex for most people, and if it does, I think you’re probably missing out

on a lot. The more truthful you can be, the sexier it is and the more

uncomfortable it can make you sitting next to a stranger in a movie

theater.

Q.

As an actress, do you look for roles that are more honest about sex?

A.

Someone

was talking to me about a film-school character trope, these women in

their 20s, quirky, happy-go-lucky, don’t-need-anything kind of girl —

that romantic comedy fantasy. But the problem with that fantasy — and

I’ve been offered so many parts like that — mostly those women don’t

have a lot of need. So you see a man kind of go, “This woman doesn’t

care what I do.” I think everybody has great need and that’s so

complicated. If somebody needs you, if you need them, all of a sudden

you’re going to have responsibility and that’s part of what’s so scary

about sex to begin with. In the case of “Hysteria” all of these women

have massive need, and some of them are so unhappy and they’re not

functioning.

Q.

Did you think having a female director was important?

A.

If

you’re directed by a woman, it’s going to change the feel of the movie.

I remember doing “Sherrybaby,” which was also directed by a woman

[Laurie Collyer] and I was doing a really complicated sex scene where

the guy in it was like, “That’s not sexy,” and we were both like, “Yes

it is.” It’s not what you think would be sexy, but it is. There’s

something about having a woman see things more like you that can be

really helpful.

Q.

What about these scenes makes them work or not?

A.

There’s

been such a history of sex scenes that don’t speak to me at all. So

when you have the opportunity to do a sex scene and still be a real,

thinking person in the midst of it, it can be an incredible way of

expressing something about who you’re playing and something about the

story. Sex on screen can be one of the most compelling ways of telling a

story. Not if you stop acting — I think a lot of people stop acting and

start pretending that they’re in a soft-core porn. But the women who

don’t I get so interested in. It’s something we don’t talk a lot about

in our culture and all of sudden there’s a comparable experience, like I

had sex in this way and it felt disappointing and lonely or I’ve had

sex in this way and experienced a connection I never could have felt any

other way. That’s where I get really interested. Even if you’re talking

to your friends, are you getting into the absolute deepest intimacies

of it? Maybe, but to see someone act it well, it can make you feel like

you have a connection to other human beings.

Q.

What was it like working with Hugh Dancy?

A.

His

character was hard. He has to make a massive philosophical change in

the way he thinks about the world in general. Which I think must have

been difficult for him. Because you kind of go: people have been having

sex forever and women have been having orgasms, so these guys just all

of a sudden truly believed that there was nothing sexual about it and

they were just having paroxysms? Either they’re so massively

disassociating and it’s terrifying, or they know it’s sexual and they

can’t say, but what a hard thing to have to play.

Q.

Do you think movies have gotten better about dealing with female sexuality?

A.

In

a lot of ways we have. In a lot of ways we haven’t. I do see some

movies now and then [with] a sex scene I can relate to and I see a lot

less of the ’90s version that I was describing before. I recently went

to see “Girlfriends” [from 1978] and it was one of the first narrative

movies directed by a woman here [Claudia Weill] and it had a huge effect

because of that. She said afterward she made it because she was tired

of going to the movies and feeling like the woman’s story was not her

story and she was like the other friend way in the background. Even

though there isn’t a lot of explicit sex in that movie, it’s about a

girl in New York trying to get by and figure out who she is, and I

related to it so much and that was made more than 30 years ago. What sex

scenes have I liked recently? The sex in “Blue Valentine.” That was

very sad and real.

Q.

Have you thought at all about “Hysteria’s” relevance in this contentious season of political debate over women’s bodies?

A.

It’s

funny because I never thought this movie could really hold a political

agenda. I don’t think you can ask it to except in a gentle way, and at

the same time so many people have said to me, there’s a scene [where] I

say I know one day women will vote and have access to education and have

rights over their own bodies. And 100 years later we still haven’t

gotten there. But my favorite thing was a woman in Italy said to me,

“Which do you think has done more for women’s equality and emancipation,

the vibrator or the dishwasher?”

April 27, 2012

Tribeca Film Festival With Sandra Siegal and Kate Linder

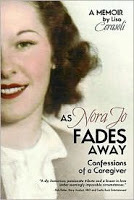

STORY MERCHANT CLIENT LISA CERASOLI ON MARIA SHRIVER’S BLOG

Alzheimer's and Caregiving

A Granddaughter’s Journey: Alzheimer’s is Not Just for The ElderlyIn 2003, I fell into caregiving quite accidentally, like most family caregivers. When my father called with a diagnosis of terminal lung cancer, without a second thought (or a single rational one), I hopped a plane back to my hometown in Michigan.

The plan? To “heal the guy” and high-tail it back to L.A. He died nine months later.

My grandfather, his father, was in the later stages of Alzheimer’s, which was verified when he looked directly at my father’s obituary and innocently asked, “Who is that guy?” That was my first genuine experience with this disease, and it was at that moment that I realized I couldn’t leave Mom and Gram.

My grandfather died shortly thereafter. I had the honor of cutting his hair the day before he passed. He spoke his first and last words in weeks that day. “Thank you,” he said, as he gazed up at me.

Directly upon the heals of his death, my grandmother, the fabulous Miss Nora Jo, started to become anxious, forgetful and more paranoid than usual.

She was always really funny and tactless; she was our “Archie Bunker in really great drag!” But eventually, she, too, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. My husband and I (along with our two-year-old daughter and his twelve-year-old son) moved her in promptly.

And that’s when life shifted from Michigan to Mars.

We had Gram up to the house every weekend for three years. So we assumed moving her in would feel the same. We were wrong. In The Secret Life of Bees, Sue Monk Kidd writes, "Knowing what’s right and doing it are two entirely different things. And it’s doing the right thing that counts.”

Well, we knew what the right thing was, and then we did it, which people constantly commend us for, but that did not take away from the shocking reality of “the doing.” And we knew from the moment we made that decision, we were in over our heads.

One year (and several anti-depressants into this adventure) later, my mom suggested I write about it. My response to that was, “Mom, I can barely put together a cohesive grocery list. You want me to write a book?!”

But after further “sleepless” contemplation, I realized, this might be a way to involve my gram, and give us both a nice distraction, along with a bit of purpose. The result was, As Nora Jo Fades Away, my second book.

Here are few excerpts:

Gram could only tell the time now by looking at the stove. “395” to her meant five minutes till Oprah! For us it meant, time to throw in the pizza!

If I left the room for any reason, my return was received as a near-reunion. That is, if they weren’t all trailing me. Let me put it to you this way: between my young daughter, Jazz, my Tea Cup Poodle, Beau, and my gram, Miss Nora Jo, I haven’t peed alone since the summer of ’05.

Gram has been referring to my daughter as “that little boy” and hiding perishables in her underwear drawer for months, and then some long-lost relatives pop in for a visit and suddenly she’s as clear and clairvoyant as a damned psychic. I swear, this job has no glory.

Gram came from a generation that didn’t know anything about “me time,” so it’s not just the Alzheimer’s that has her terrified to be alone. Still, it’s tough, and some days the guilt engulfs me. I want to hold her hand through this whole journey but there are days when answering the same questions become unbearable: My husband is Pete; his son is Brock; I’m Jazzy’s mom. It’s January. It’s June. It’s 2009. No, Gram, we’re not going to have a hurricane, that was national news. My husband is Pete; his son is Brock; I’m Jazzy’s mom. It’s January. It’s June. It’s 2009. It’s all so exhausting...

There she was, rocking in her chair to the beat of her tears. It was Christmas Eve. I approached cautiously. “Gram, what’s wrong?”

“I’m just so ashamed. I didn’t know Ricky-- my own grandson. I’m just so ashamed.” She choked out.

“It’s okay. It’s okay.” I consoled. “Like fifty percent of people your age suffer from memory loss.”

“Yeah, but eighty percent of ‘em are already dead!” She retorted.

...And the woman had a point.

Writing made me realize that this journey was not just exhausting, but contained an abundant series of oddly touching moments that were changing us all for the better.

The memoir won the 2010 Paris Book Festival, and then the London and L.A. Book Festivals, as well, which honestly gave me confidence (and some energy) to pursue Alzheimer’s advocacy on a bigger level.

There was so much we were all learning, about ourselves, this disease, the power of compassion, the ability to “let go.” And the book exposed all angles of the illness -- guilt, fear, anger, devastation, but also the foibles and the funnies that were occurring, too.

And then in the Fall of 2010, I went to Maria Shriver's March on Alzheimer’s in Long Beach, California. I came back even more re-energized (and not just ‘cause I got a break)!

I decided that younger generations needed to become familiarized with this disease, and that the best way to “education” that demographic would be to make it feel like entertainment.

So, I started filming us. Gram was engaging and hilarious and incredibly endearing. And she had passed those traits straight down to my daughter, Jazz, her great granddaughter. So I had two great leading ladies who were a near-century apart but saw each other more as sisters.

And many of their “commonalities,” like their love of card games and coloring contests, made our journey manageable. And we were no longer in “over our heads.” The water was often “neck high,” but we had learned to stay afloat. We still weren’t perfect, but we were pulling it off.

Caregiving is going to be inevitable for many. My objective and my passion is to create mass awareness until we find a cure. There are hidden joys in every aspect of life, even when illness strikes. \

Knowledge is power. Compassion is key. Love and humor can conquer anything. And we are all much stronger than we think.

My grandmother and my daughter taught me that life is about perspective. My documentary, “14 DAYS with Alzheimer’s,” has become mine.

********

In 2003, Lisa Cerasoli (then an actor - Series Regular, General Hospital) met with Ken Atchity about her screenplay. He said, “Sounds like a novel.” She started writing while simultaneously leaving for Michigan to care for her Dad. On the Brink of Bliss & Insanity - published by Five Star Publications - was the result. It won The London & L.A. Book Festivals. As Nora Jo Fades Away, evolved when Lisa & family took in her gram upon diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. It won The 2010 Paris Book Festival, then nabbed a beautiful foreword from Leeza Gibbons. It’s optioned by RicheProductions. They are currently developing the series. Lisa refers her documentary, “14 DAYS with Alzheimer’s,” as “the sequel” to her memoir. It was completed in August of 2011 and has been touring ever since.

April 26, 2012

REGISTER FOR MY NEXT FREE WEBINAR MAY 8, at 2:30 PM (est.)

Writing Treatments that Sell

The treatment is a tool used by Hollywood writers to provide a

compelling overview of a story prior to writing or revising it. It’s as

useful as a marketing device as it is as a diagnostic tool, and some

treatments have even sold for millions of dollars. Based on his

bestselling book, Writing Treatments that Sell, Dr. Atchity will show

you what a treatment is and what you need to know about its essential

elements in order to add it immediately to your arsenal of professional

writing tools.

About the Presenter

About the PresenterDr. Atchity is the author of 15 books, including A Writer’s Time,

Writing Treatments That Sell, and How to Publish Your Novel. He’s worked

successfully in nearly every area of the publishing and entertainment

business, and has spent his lifetime helping writers get started with

and improve their careers. As founder and head of Atchity Entertainment

International, Inc., The Writer’s Lifeline, Inc., including Atchity

Productions and Story Merchant, and The Louisiana Wave Studio, LLC. he

has produced nearly 30 films in the past 20 years for major studios,

television broadcasters, and independent distribution. He is currently

nominated for an Emmy for “The Kennedy Detail,” based on the New York

Times bestselling book he developed. For nearly twenty years before, as

professor of literature and teacher of creative writing at Occidental

College and UCLA, he helped literally hundreds of writers find a market

for their work by bringing their craft and technique to the level of

their ambition and vision. During his time at Occidental, he also served

as a regular reviewer for The Los Angeles Times Book Review.

Register Now

May 8, 2012 at 02:30PM

May 31, 2012 at 02:30PM

April 25, 2012

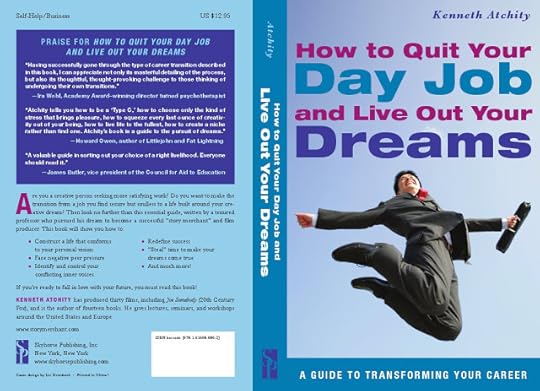

New Cover: How to Quit Your Day Job!

April 24, 2012

Hysteria's US Premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival

March 21, 2012

Story Merchant Client Lisa Cerasoli's "14 DAYS with Alzheimer's" is an Official Selection at 7th International Women's Film Festival

Screening is at 11:00 am on Sunday, March 25th

West Hollywood Library

625 N San Vicente

West Hollywood CA 90069

Based on the award-winning memoir, As Nora Jo Fades Away, 14 DAYS with Alzheimer's is the documentary short (follow-up) to the book. It's a humorous, heartbreaking and revealing look into the lives of Nora Jo and Lisa, her granddaughter and caregiver. This film leaves little to the imagination. Nora Jo has officially turned into 'Archie Bunker in really great drag,' and so this film captures not only the series of tragedies that come with this illness, but the 'funnies and the foibles' as well. And it proves that while Alzheimer's is also known as The Memory Thief, it's incapable of stealing love.

Based on the award-winning memoir, As Nora Jo Fades Away, 14 DAYS with Alzheimer's is the documentary short (follow-up) to the book. It's a humorous, heartbreaking and revealing look into the lives of Nora Jo and Lisa, her granddaughter and caregiver. This film leaves little to the imagination. Nora Jo has officially turned into 'Archie Bunker in really great drag,' and so this film captures not only the series of tragedies that come with this illness, but the 'funnies and the foibles' as well. And it proves that while Alzheimer's is also known as The Memory Thief, it's incapable of stealing love.The Los Angeles Women’s International Film Festival is produced by Alliance of Women Filmmakers Inc. a non-profit 501c(3) organization established by Diana Means to empower women filmmakers to create diverse roles for women. Each year in March the festival showcases narratives, documentaries, animation and student short films. The festival’s programming reflects Diana’s commitment to educate and inform audiences of social political and health issues impacting women globally.

To Purchase Tickets Click Here

March 20, 2012

Join My FREE Webinar Tomorrow 2:30 pm (est)

In today’s publishing turmoil, as the internet challenges traditional publishing and traditional agents are retooling to stay abreast of the changing tide, it’s become even more difficult to find an author’s representative. Dr. Atchity will lead you through the steps that will give you a fighting chance to find someone who will take you and your book seriously in this session based on his book How to Publish Your Novel (useful also for nonfiction writers).

In today’s publishing turmoil, as the internet challenges traditional publishing and traditional agents are retooling to stay abreast of the changing tide, it’s become even more difficult to find an author’s representative. Dr. Atchity will lead you through the steps that will give you a fighting chance to find someone who will take you and your book seriously in this session based on his book How to Publish Your Novel (useful also for nonfiction writers). About the PresenterDr. Atchity is the author of 15 books, including A Writer’s Time, Writing Treatments That Sell, and How to Publish Your Novel. He’s worked successfully in nearly every area of the publishing and entertainment business, and has spent his lifetime helping writers get started with and improve their careers. As founder and head of Atchity Entertainment International, Inc., The Writer’s Lifeline, Inc., including Atchity Productions and Story Merchant, and The Louisiana Wave Studio, LLC. he has produced nearly 30 films in the past 20 years for major studios, television broadcasters, and independent distribution. He is currently nominated for an Emmy for “The Kennedy Detail,” based on the New York Times bestselling book he developed. For nearly twenty years before, as professor of literature and teacher of creative writing at Occidental College and UCLA, he helped literally hundreds of writers find a market for their work by bringing their craft and technique to the level of their ambition and vision. During his time at Occidental, he also served as a regular reviewer for The Los Angeles Times Book Review. Register Now March 21, 2012 at 02:30PM

March 19, 2012

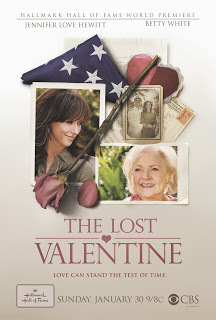

The television winner of the Faith & Freedom Awards Goes to “The Lost Valentine!”

Christian Oscars Honor Family Friendly Films

Written by Raven Clabough

On Friday, February 10, the winners of the 20th Annual Faith and Values Awards were announced at the Universal Hilton Hotel in Hollywood. A number of worthy films and television programs received prizes for their positive elements from patriotism to family values.

The Movieguide Faith and Values Awards are sponsored by the Christian Film & Television Commission and Movieguide, founded by Dr. Ted Baehr. The glittering event, also dubbed the “Christian Oscars” attracted a number of Hollywood executives, producers, writers, and directors, and major celebrities including Joe Montegna, Kevin Sorbo, James Patrick Stuart, and Pat Boone.