Kenneth Atchity's Blog, page 15

September 6, 2024

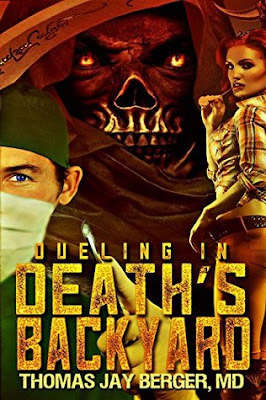

Archaeolibrarian Reviews Thomas Jay Berger's Dueling in Death's Backyard!

Add to Goodreads

Add to GoodreadsGenre:Medical, Thriller

Synopsis:What is it like to stop a heart and duel with death in his own backyard with a human life at stake? Until now, only a cardiac surgeon could know.

And only a cardiac surgeon with the skills of a Faulkner award winning writer could bring readers not just into the O.R. but into the heart itself to share that cosmic experience. In Dueling in Death’s Backyard, Thomas J Berger, MD – trained by Dr. John Kirklin, the true Father of Cardiac Surgery -- does exactly that and does it in the context of a medical murder mystery exposing a VA hospital scandal from decades before they became front page news.

After 13 hours and 30 units of blood, Cooper Logan and his mentor, Holt McDuff had nearly succeeded in replacing the old farmer’s entire dissected aorta. When the final suture line exploded, they were soaked in sticky scarlet blood in seconds and what had been a human being became a pile of organic junk. If the difference was a soul, it had slipped unseen through their fingers. Although he hadn’t slept in days, Cooper insisted on closing and breaking the news to the family. At least he could spare Holt those depressing final chores.

A wrestling scholarship had taken Cooper from a troubled youth in Boston to a surgical residency in Birmingham, Alabama, where he fit in like a Hell’s Angel at a British High Tea. He was more Clint Eastwood as Rowdy Yates than Richard Chamberlain as Dr. Kildare, and everyone kept telling him he didn’t look like a doctor.

Cooper was obsessed with becoming a cardiac surgeon -- stopping hearts and pitting his scalpel against Old Grim’s scythe right there in Death’s backyard. Most doctors spend their lives avoiding such situations. Only Cooper, and other cardiac surgeons, live to fight on that mystic battlefield for the life of every patient.

Culture shock and hospital politics threaten Cooper’s chances for success, but with Holt’s help he is on track to complete his residency. Then, conflict with a drug addicted nurse and her powerful protector get Cooper fired. His lover dumps him and it seems that things couldn’t get much worse. Then they do. The druggy nurse is murdered and Cooper is framed for the crime. Dr. McDuff seems to want to help but has his own secret agenda. To save his dream and his life, Cooper must unravel a mystery decades older than he is, and solve a murder in the process.

“Gently Cooper...caress her. The coronary is a women...caress her with the scalpel and she will open herself for you.”

4 out of 5 (very good)

4 out of 5 (very good)Independent Reviewer for Archaeolibrarian - I Dig Good Books!

I have to say this was different from my usual. In a good way! The dramatic opening page where you've a man bleeding out, told in a very graphic way. With the twist of being told as a doctors memoir. I really enjoyed it, and was a bit concerned this opener couldn't be topped. That was my mistake, entirely. It could, it did!

I liked the character of Tiny the best. As much as I liked the character of the trainee doctor, Tiny just had so many facets. He wasn't just the stereotypical dumb criminal, you actually liked him, despite knowing he was a character who'd take you out without a thought, and I don't mean for dinner!!

The book twisted and turned and everyone had a dark secret, or something they would rather you didn't know.

If you don't like details about medical procedures, and how heart operations work, I'd say steer clear, but if you like knowing from a real doctor, the story itself is fiction ,but you can sense some of the thoughts and feelings are true.

Give this book a go, if it wouldn't normally be on your genre of choice. So glad I did!!

Amazon UK | Amazon USKindle Unlimited

Amazon UK | Amazon USKindle Unlimited

Tom Berger is a Faulkner Award winning author, distinguished cardiac surgeon, adventurer, and lifetime martial artist. After training with his mentor, Dr. John Kirklin, the true Father of Cardiac Surgery, Dr. Berger went on to start his own cardiac surgery program in a small town in Montana. His program was recognized by the Wall Street Journal as being tied for the lowest mortality in the nation for Medicare coronary artery bypass procedures. Settled now in Miami, Dr. Berger continues to train in the martial arts, writes, and consults as an expert in medical malpractice cases.

Reposted from Archaeolibrarian

September 4, 2024

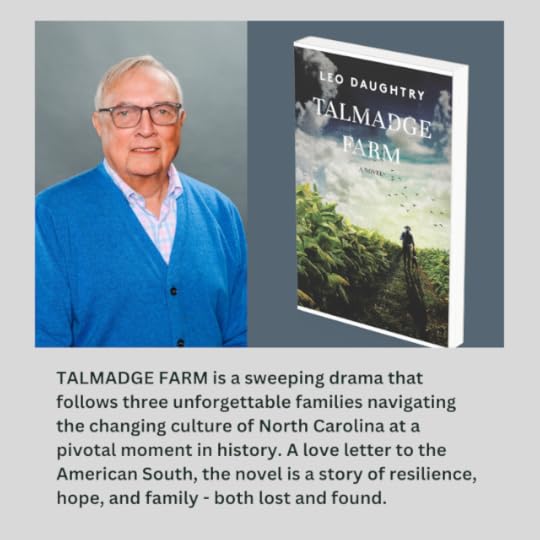

Books Forward Marissa DeCuir Interviews Author Leo Daughtry About his Debut Novel Talmadge Farm

What inspired you to write “Talmadge Farm?”

I lived through changing times, particularly the 1950s when there was nearly complete segregation in the South, especially in rural areas. Sharecropping was common, and women did not divorce in those times because it was considered demeaning, a failure. Then in the 1960s, everything began to change. Sharecropping disappeared, birth control entered the picture, and women could live life with more freedom and less dependence on men.

Can you tell us more about your family history and its connection to North Carolina and tobacco? How did this environment influence your writing? Beyond the direct associations with tobacco and North Carolina, are there more subtle aspects of your upbringing and family history that influenced your writing?

Tobacco was king in North Carolina. People practically worshiped it. Where I grew up, it put food on the table. Cotton was more up and down, but tobacco provided financial stability, not just for farmers but for the whole community. My family grew tobacco, sold fertilizer and seed, and managed a tobacco auction. It was our whole world.

You have had a successful career as a lawyer and an Air Force Captain before that. What prompted you to pursue writing fiction?

I always had the idea for this particular story in my head. The 1950s and 1960s were two decades that changed the world, and a farm with sharecroppers is a bit of a pressure cooker environment. You have the farmowner’s family – in many cases people of wealth and entitlement – living just down the driveway from the sharecropping families. The sharecroppers were poor and had limited options, so they felt stuck living on a farm that didn’t belong to them doing backbreaking work with no way out. It’s a situation that lends itself to drama: families with major differences in class/race/socioeconomic status living in such close proximity to one another.

How has the landscape of tobacco farming changed, and how did you incorporate those changes into the plot of “Talmadge Farm?”

Probably the biggest change was the shift from sharecropping to migrant workers. Today, tobacco farmers are large corporations that use migrant workers as laborers. But in the 1950s, farming relied almost completely on sharecropping, which was a hard life. Tobacco farming is physically demanding work, and sharecroppers needed the help of all family members to complete the various steps – planting, seeding, suckering, priming, worming, and cropping – of harvesting the crop. Sharecroppers at one farm would help sharecroppers at the neighboring farm because they did not have the resources to hire extra people. In the 1950s, sharecroppers were unable to get credit anywhere but at the general store and maybe the feed store. They truly lived hand to mouth all the time, only able to pay their debts after the tobacco auction in the fall. Hence the phrase “sold my soul to the company store.” Sharecroppers often turned to moonshining as a way to make extra money.

As I describe in the novel, sharecropping began to disappear in the 1960s as children of sharecroppers started taking advantage of new opportunities that the changing society offered. Migrant workers took over the labor of farming. In addition to labor changes, new machinery improved the industry. N.C. State was instrumental in developing advances in the farming world. Legislation changed and farmers were allowed to have acreage allotments outside of the land they owned. I touch on all of these changes in the novel.

Are any of the characters in your book based on real people?

Not really. The closest characters to real people in my life are the characters of Jake and Bobby Lee. Jake is a Black teenager who wants to escape farm life and ends up running away to Philadelphia to become a success. Bobby Lee is a young Black soldier stationed at Fort Bragg. On the farm where I grew up, there was a Black sharecropping family with four sons, the youngest of whom was my age. We were very good friends. All of the boys were bright and athletic, could fix anything, yet were limited in their opportunities. They didn’t have a school to go to or a job to look forward to. Their only options were to stay on the farm or join the army. The character of Gordon, while not based on any one person, reminds me of a lot of men I knew who did not treat women well, who were racist, who enjoyed the status quo and were resistant to anything that threatened their way of life.

In addition to the changing tobacco farming methodologies, the 1950s ushered in a period of profound social change, marked notably by the introduction of credit cards. How did these outside factors impact farming, and in what ways did they inform the development of the plot in “Talmadge Farm?”

In the novel, Gordon is the president of the local bank, yet he resists the advances in the banking industry, including credit cards and car loans and the incursion of national banks into rural communities. Gordon’s father, who founded the bank, was a brilliant man adept at navigating the bank through changing times, but Gordon simply doesn’t have the smarts to see what’s coming, and no one can get through to him. He’d rather play a round of golf than look at the balance sheet. So between the changing farming landscape and the evolution of new banking practices, Gordon is getting squeezed from both sides of the ledger as it were. It proves to be his downfall. I think that’s one of the great strengths of the plot – how everything is tied to everything else.

How did other social changes – including race relations – impact the tobacco industry and your writing?

In the 1960s, the minority labor pool available to farm tobacco began to dry up as kids started moving up north or joining the army. We see this in the novel through the characters of Jake and Bobby Lee. Ella is another example. She’s the Black teenage daughter of a sharecropping family, and she hates farm work. She ends up enrolling in a secretarial program and getting a job at the county clerk’s office, opportunities that were unheard of in the 1950s.

The Surgeon General issued a groundbreaking report 60 years ago on the harmful effects of smoking. How did this pivotal moment influence your approach to writing? What firsthand impacts did you observe while coming of age among the tobacco farms of North Carolina?

Most people where I lived didn’t believe the Surgeon General was accurate in that report. Most everyone smoked. People viewed it as the government coming in and trying to tell us what to do. A prevailing theme was that the government was trying to get rid of tobacco but wasn’t doing anything about alcohol. One notable exception I remember is that good athletes in the 1950s were discouraged from smoking, so maybe the coaches were on to something that the rest of us weren’t ready to hear yet. In the novel, we see Gordon’s constant frustration at what he views as interference from the government, while other characters, mostly ones involved in the medical community, begin to appreciate that smoking was bad for one’s health.

How did you address the plight of women in the novel?

In the 1950s, women were very limited in their opportunities. There were very few professional opportunities for women outside of teaching, nursing, and working as a secretary. Divorce was scandalous and unheard of in those days. We see lots of examples of this in the novel. But of all the characters, it’s two of the women who have the clearest moral compasses: Claire, Gordon’s wife, and Ivy, the Talmadges’ maid. Both of them see more clearly than anyone else where Gordon is going off the deep end, but they are nearly powerless to do anything about it.

The novel touches on themes of privilege, racial injustice, and the struggle for autonomy and dignity. How did you navigate these sensitive topics while crafting the narrative, and what challenges did you encounter along the way?

I lived through this time, and I witnessed first-hand people who enjoyed privilege that was unearned as well as racial injustices that denied Black people access to the same opportunities as white people. And yet most people – white and Black – were simply striving to make a better life in an honorable way. I tried to infuse all of the characters in “Talmadge Farm” with dignity and humanity, even Gordon, who finally gets his comeuppance in the end.

The novel is described as a “love letter to the American South.” Can you expand on this sentiment?

As I look back on my childhood, in many ways it was a wonderful time to grow up. It was safe. We never locked our doors. Our whole life existed just in that area; it was a long trip traveling to Raleigh, which was only 60 minutes away. There was a strong sense of community, of church, of taking care of each other.

Ultimately, what do you hope readers will take away from “Talmadge Farm?”

I mainly hope they will be entertained by a great story about three families who called Talmadge Farm home during the tumultuous times of the 1950s-1960s.

What impact do you aspire for the book to have on discussions about history, identity, and resilience in the American South?

We have now moved on from the post-Civil War time and the Jim Crow period to a place where we’re beginning to find our identity as a state and region. In the 1950s, North Carolina was one of the poorest states in the country. Our economy was dependent primarily on tobacco farming but also textiles and furniture making, none of which paid a living wage. Segregation was rampant, and minorities had few opportunities to improve their lot in life. Our university graduates who studied computer science and technology ended up leaving the state to find jobs in those industries. That all began to change in the 1960s with the enforcement of desegregation, the advent of birth control, and changes in farming regulations and methods. Another major turning point in our state’s economy was when Governor Hodges convinced IBM to move from New York to North Carolina as part of the development of the Research Triangle Park. A large number of technology and pharmaceutical companies followed suit, and there was a ripple effect that extended across the state, even to areas like Hobbsfield, our fictional town in “Talmadge Farm.” My hope is that reading this novel will help people understand how we got to where we are today.

Marissa DeCuir

Marissa DeCuirA former award-winning journalist with national exposure, Marissa now oversees the day-to-day operation of the Books Forward author branding and book marketing firm, along with our indie publishing support sister company Books Fluent.

Born and bred in Louisiana, currently living in New Orleans, she has lived and developed a strong base for our company and authors in Chicago and Nashville. Her journalism work has appeared in USA Today, National Geographic and other major publications. She is now interviewed by media on best practices for book marketing.

September 2, 2024

Story Merchant E-Book Deal FREE September 2 - September 6! Dueling in Death's Backyard by Thomas Jay Berger, MD

AVAILABLE ON AMAZON

A gifted heart surgeon finds himself facing the big questions about death and a soul’s release. Everyone has a dark secret or something they would rather you didn't know.

What is it like to stop a heart and duel with death in his own backyard with a human life at stake? Until now, only a cardiac surgeon could know.

And only a cardiac surgeon with the skills of a Faulkner award winning writer could bring readers not just into the O.R. but into the heart itself to share that cosmic experience. In Dueling in Death’s Backyard, Thomas J Berger, MD – trained by Dr. John Kirklin, the true Father of Cardiac Surgery -- does exactly that and does it in the context of a medical murder mystery exposing a VA hospital scandal from decades before they became front page news.

After 13 hours and 30 units of blood, Cooper Logan and his mentor, Holt McDuff had nearly succeeded in replacing the old farmer’s entire dissected aorta. When the final suture line exploded, they were soaked in sticky scarlet blood in seconds and what had been a human being became a pile of organic junk. If the difference was a soul, it had slipped unseen through their fingers. Although he hadn’t slept in days, Cooper insisted on closing and breaking the news to the family. At least he could spare Holt those depressing final chores.

A wrestling scholarship had taken Cooper from a troubled youth in Boston to a surgical residency in Birmingham, Alabama, where he fit in like a Hell’s Angel at a British High Tea. He was more Clint Eastwood as Rowdy Yates than Richard Chamberlain as Dr. Kildare, and everyone kept telling him he didn’t look like a doctor.

Cooper was obsessed with becoming a cardiac surgeon -- stopping hearts and pitting his scalpel against Old Grim’s scythe right there in Death’s backyard. Most doctors spend their lives avoiding such situations. Only Cooper, and other cardiac surgeons, live to fight on that mystic battlefield for the life of every patient.

Culture shock and hospital politics threaten Cooper’s chances for success, but with Holt’s help he is on track to complete his residency. Then, conflict with a drug addicted nurse and her powerful protector get Cooper fired. His lover dumps him and it seems that things couldn’t get much worse. Then they do. The druggy nurse is murdered and Cooper is framed for the crime. Dr. McDuff seems to want to help but has his own secret agenda. To save his dream and his life, Cooper must unravel a mystery decades older than he is, and solve a murder in the process.

August 30, 2024

New From Story Merchant Books The Little Chinese Girl by Sylvia Kramer

The bond between a mother and a child is never broken. Rose, the little Chinese girl, is loved. She is kidnapped from her birth mother but never forgotten. She is rescued, adopted and cherished. From the far away rice paddies of her birth to the loving arms of her adoptive mother in New York City. Rose is the living proof of the pure love between a mother and a child. Her journey is not over as she is called to heaven in a tragic accident leading her adoptive mother into the arms of Jesus as she learns to live again. If you have ever loved a child this hauntingly beautiful novel will reach your core. The Little Chinese Girl is a journey of love.

August 26, 2024

Story Merchant E-Book Deal #FREE August 26 - August 30 ! My Obit: Daddy Holding Me by Kenneth Atchity

AVAILABLE ON AMAZON

August 23, 2024

“Mirrors and Prisms”: An Interview with Dennis Palumbo About Art, Life, and Psychotherapy – Part I

SECOND THOUGHTS

By Vincenzo Di Nicola, MPhil, MD, PhD, FCAHS, DLFAPA, DFCPA

Dennis Palumbo, MA, MFT

Introducing Dennis Palumbo – Psychotherapist and Writer

It is a pleasure to introduce Dennis Palumbo, MA, MFT, to the readers of Psychiatric Times. Dennis is a licensed psychotherapist in Los Angeles, CA, where he specializes in treating individuals in the creative arts community of Hollywood. He is uniquely well-suited for this specialized work given his double, even triple, skill sets as a former Hollywood scriptwriter and current detective fiction novelist,1 teacher of creative writing,2 and his work with Robert Stolorow, MD, incorporating intersubjectivity theory in his psychotherapeutic work. Dennis will soon be addressing readers of Psychiatric Times in a monthly column of his own, “Creative Minds: Psychotherapeutic Approaches and Insights.” His latest essay is about his role as Consulting Producer on the recent Hulu TV series, “The Patient.”3

We have had an enriching exchange about art, life, and psychotherapy for several years. Dennis was our invited guest for the inaugural meeting of American Psychiatric Association Caucus on Medical Humanities in Psychiatry in New Orleans, LA, in 2022. Dennis’ uniquely diverse and specialized skill sets allow me to explore the question of the relationship between the psy disciplines and detective fiction. More generally, I wanted to explore the roots of creativity and empathy in creative writing and clinical work and connect it to therapy.

Besides international literary fiction and poetry, detective novels and murder mysteries have been my great avocational passion, something that Dennis and I share with such serious thinkers as Austrian-British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein and British social psychiatrist Sir Michael Shepherd, MD, who wrote an insightful little book about Sherlock Holmes and Freud. And literary greats from Jorge Luis Borges to TS Eliot chimed in on what makes great detective fiction, not to mention pliers of the trade, especially British detective fiction writer PD James.4

Mirrors and Prisms

In this interview, Dennis Palumbo talks about the classical notion of “art imitating life” and something more intriguing, more crucial where “the arts inform life.” The first formulation sees art as a passive mirror, whereas the second one sees the arts are a transformative prism. This was brilliantly expressed in the “Ultra Manifesto,” an “iconoclast ideology” whose bold credo was “not to have a credo,” by a group of Spanish writers including Jorge Luis Borges5:

Two aesthetics exist: the passive aesthetic of mirrors and the active aesthetic of prisms. Guided by the former, art turns into a copy of the environment’s objectivity or the individual’s psychic history. Guided by the latter, art is redeemed, makes the world into its instrument, and forges—beyond spatial and temporal prisons—a personal vision.

With his dual careers as a writer and a psychotherapist, Dennis Palumbo offers his insights into how art imitates life imitates art.

Vincenzo Di Nicola, MPhil, MD, PhD, FCAHS, DLFAPA, DFCPA: You have been in private practice as a psychotherapist for over 30 years and prior to that you were a Hollywood screenwriter, working in both TV and film. Can you talk about that experience?

Dennis Palumbo, MA, MFT: Looking back on my career in Hollywood, what springs most to mind is how lucky I was. Yes, I was a good writer and a hard worker, and subscribe to Louis Pasteur’s belief that “chance favors the prepared mind.” But I knew many others starting out when I did who were even better writers and worked harder, yet they never achieved their career goals.

In both TV and film, I was fortunate to work with many people I admired. But, as any Hollywood scribe will tell you, it is a brutal industry, and can be quite unkind to writers. The cliched narrative of having to appease diva-like stars, dictatorial directors, and illiterate studio and network executives is no cliché for those toiling in the screen trade. And while my experience in show business was overwhelmingly positive, I found the constant hustling and struggle to maintain creative integrity taking a considerable toll over the years. In fact, once my screenwriting career had been established, my concurrent turn to prose writing was a counterpoint to some of my frustrations with the limits of Hollywood storytelling. I was also frustrated by the way TV and film writers are routinely treated; unlike the theater and with books, Hollywood writers do not own copyright on their material, so it can be rewritten, edited, or discarded by producers, directors, and studio execs at their discretion. In retrospect, I see my turning occasionally to prose writing during this period as an example of what a self-psychologist might term an “antidote function” or a Freudian “reaction formation.”

Di Nicola: British physician and author Arthur Conan Doyle, MD, was inspired by the clinical reasoning of his medical professor at Edinburgh to portray the famous deductions of his character Sherlock Holmes. Another Brit, Sir Michael Shepherd, MD, wrote a little book on Sherlock Holmes and The Case of Dr Freud6 and your friend Nicholas Meyer wrote the best Sherlock Holmes pastiche about a fictional encounter between Holmes and Freud in The Seven-Per-Cent Solution.7 Can you explain the enduring appeal of crime and detective stories, from both a writing and a psychological viewpoint?

Palumbo: From a psychological point of view, the standard response to this question is that the detective brings order to a disordered world; when the guilty person whose crime has torn the fabric of civilized society is exposed and caught, that fabric is mended.

I also think the character of the detective (whether male or female, private or an amateur, or a member of the official police) speaks to our yearning for a parent figure who is smart, compassionate, and dogged in their pursuit of the truth. As children, we need the security of knowing where things stand; what can and cannot be relied on. In most crime fiction, we can rely on the protagonist to share that need with us and, like a good parent, in the end provide it.

In my own crime fiction, my psychologist hero/amateur sleuth serves this purpose in spades.1 In fact, as clinicians sift through facts, emotions, and patterns of behavior in search of illuminating a patient’s core issues, so does the hero in crime fiction. Both therapists and detectives look for “clues,” and then are tasked with finding out what truths they may point to.

I say this with a caveat: I am not totally comfortable with the notion that clinical treatment is primarily some kind of detective work. Just as I have always been uneasy with it described as archeological work, “digging” for the truth underlying a patient’s issues. For one thing, it implies that unearthing such material helps “cure” the patient; ie, helps the patient return to a “normal” level of functioning. Once again tasking (approvingly) the therapist with being an agent of the dominant culture.

That said, the psychological appeal of the protagonist in crime fiction is undoubtably bound up in our need for a hero/parent/restorer of order. At the most basic level, while we readers are often thrilled or titillated by the crimes depicted, we want good to triumph over evil. We want justice to prevail. Again, a somewhat regressed need, frequently seen in a young child’s firm belief in the rightness and necessity of rules (before adolescence comes along and shreds that belief).

In looking at the popularity of crime fiction in terms of writing, I think you have to go back to the Greeks. Unlike other fiction, particularly what we call “literary fiction,” most crime fiction is plot-driven. No matter how well-written, no matter how multidimensional the characters may be, no matter how grounded in psychological sophistication the narrative is, crime and detective fiction is built on plot. The crime, the suspects, the clues, the hero or heroine’s missteps until glimpsing the truth—these elements make for a satisfying mystery story. This does not always mean a “happy ending,” but readers expect (and deserve) a structure built along these lines.

Drama has its demands, and crime fiction has even more. Nowhere outside of children’s fiction is the requirement for a beginning, middle, and end so stringent. The point is, life does not make sense. Much “literary” fiction reaffirms this. Crime fiction—for all its violence, disturbing psychological themes, and often bizarre plot—is popular because, in the end, the story satisfies. The pieces all come together and make sense. Unlike the ragged edges of life, the solution of a crime novel or short story completes a narrative Gestalt that satisfies the reader.

Di Nicola: Can you address the mirror issues of empathy (psychotherapy) vs cruelty (psychopathy) that detective fiction deals with?

Palumbo: In most crime or detective fiction, a duality within the human personality is a given. Reminiscent of Robert Louis Stevenson’s theme in his Strange Case of Jekyll and Hyde, in which he posits a simple internal struggle between good and evil in each person, today’s crime fiction tends toward a more sophisticated approach, which indeed mirrors the psychological concept of empathy vs sociopathy.

Psychotherapy is based on an assumption of a clinician’s empathy, whether using Carl Rogers’ proposal of “unconditional positive regard” or else some more contemporary understanding of the intersubjectivity inherent in the therapeutic dyad. Despite what personal issues and preferences the clinician brings to the treatment room, and the ways these interact with those of the patient, the given is that the therapist cares. In crime fiction, as in life, the sociopath does not.

In most crime and detective fiction, especially in recent years, the protagonist “cares” in a similar way, often expressed as “the victim in this case deserves justice,” or—again, a more modern narrative device—the detective or police officer relates personally to the victim’s history or circumstance. Seeing him- or herself in the victim’s shoes often aids in understanding the cause of the crime or points to the motives of possible suspects.

Conversely, the cruelty of the villain is implied by a lack of such empathy, or even a clearly determined stance against the notion of relating in any way to his/her victim. This can be bluntly stated by the villain (things he/she says to the victim or evidenced by such dramatic device as letters sent to the media or messages left at the crime scene. The other evidence of the antagonist’s sociopathy is the heightened brutality of the crime, in which the murders are noteworthy for their excessive violence or degradation of the victim.

Regardless of approach or level of psychological sophistication, this good/evil duality within each of us is assumed in crime fiction as a given. Perhaps reflecting the notion that the reader sees the human condition in these same terms.

Di Nicola: That’s an intriguing take! We are both fans of Film Noir, in which the detective protagonist crosses the line and is often as transgressive as the criminal.8 How do you account for that?

Palumbo: Because the line between empathy and cruelty is thin and even porous. One of the reasons we love Film Noir is that the ostensible protagonist often crosses that line, either for a woman or out of greed, and our own desires resonate with his choices, even as we fear the eventual (and usually inevitable) outcome.

Di Nicola: What prompted your career change from screenwriter to psychotherapist? And what were the challenges involved?

Palumbo: Ironically, the year I retired from screenwriting was one of the most financially successful in my career. I had attained my graduate degree and completed the required 3000 intern hours to sit for the clinical exam while still working as a Hollywood writer, with only my wife and a few close friends knowing about my studies and shift in career goals. But as to what had prompted this decision, one that was viewed as either brave or crazy by those who knew (most falling into the latter camp), my reason was twofold: firstly, I had always been interested in psychology and philosophy, and had read widely in both subjects since college. This interest was intensified by the 3 months I spent in Nepal. Ostensibly there to research the life of a famous mountain climber for a proposed film, I instead lived, studied, and meditated at altitude in the Himalayas. During this period of intense reflection—and living far away from the distractions and obligations of my Hollywood career—I began to feel a need to change the course of my life. But more importantly, it was my many years as a patient in therapy (prior to and following my Nepal sojourn) that ultimately prompted the decision. The therapeutic dyad had become—and remains—the most emotionally and intellectually challenging experience of my life. It speaks to a core preoccupation of mine with the varieties of subjective perception, including my own. An interest I had explored, to the limited extent allowed in a commercial marketplace, as a screenwriter. But now I no longer wanted to be merely a curious and empathic witness to what was going on in the pool—I wanted to jump into the water myself.

The biggest challenge in changing careers was to convince myself that I was allowed to do it. Coming from a hard-working, blue-collar background, the thought of walking away from a successful, high-paying job to venture into the uncharted territory of a clinical practice often felt like a rebuke to my more pragmatic, “common sense” self-concept. Yet as the years of study and practical experience as an intern at a low-fee family clinic and a psychiatric facility went on, I was more and more convinced that this new path was the right one for me. In the 3 decades since, I have never once regretted that decision.

Di Nicola: You specialize in treating creative people, primarily in the entertainment industry. Besides drawing on your own experiences, was there some specific reason that you chose to specialize in this area?

Palumbo: I knew from the start of my practice that I wanted to work with creative individuals, but not only because of my previous career. I have always been fascinated by the struggles that artists, including myself, deal with on a daily basis—issues both personal and professional. I also deeply revere artists and feel their contribution to society is at the same time profound, underrated and woefully misunderstood. Kierkegaard said that faith is a nonrational commitment; I think the same thing could be said of a commitment to a creative career. Or as one of my writer patients said of the desire to write: “It’s a blessing you’ve been cursed with, or else a curse you’ve been blessed with.” I could not put it any better myself.

Di Nicola: What are the most common issues your creative patients present?

Palumbo: Initially, most creative patients present with what I might call “the usual suspects”: writers’ block, procrastination, fear of rejection, etc, with the accompanying anxiety. There is also the depression that often predominates when creative aspirations go unfulfilled for a long period of time. And even for those artists who are in relationships, or enjoy the benefits of a strong social network, most creative endeavors—especially in their early stages—require a significant period of solitude, which for some is experienced as acute loneliness. Not to mention the financial issues, dealing with the politics of the marketplace, and a variety of other more pragmatic concerns.

Di Nicola: You have mentioned elsewhere that these creative issues are inextricably bound up patients’ personal issues. What do you mean?

Palumbo: I am referring to the fact that a patient’s particular set of issues, and especially the meanings they assign to them, are at the core of their creative struggles. For example, as painful and frustrating as it is to encounter a creative block, what makes navigating it so difficult is the meaning patients give to being blocked. What if it means the project they are working on is flawed? What if it means they are less talented than they had hoped? What if they are sure that (insert favorite artist here) never gets blocked? What if their parents were right and they should have gone to law school? These kinds of meanings need to be explored before the more pragmatic concerns that might underlie the block can be addressed. These concerns are usually (but not always) shame-based.

Let’s use writers’ block as an example: Perhaps the writer has never before written an explicit sex scene and so freezes at the thought. Perhaps the narrative involves characters that closely resemble or are even based on the writer’s family of origin. Maybe the writer has only done nonfiction and is trying fiction or poetry for the first time. Or maybe the writer has had success in one genre but is anxious to try another. Concerns such as these, usually involving a fear of shameful self-exposure, are often aspects of the writer’s creative roadblock that need to be investigated.

Di Nicola: In his autobiography, The Magic Lantern, Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman9 confessed that he turned himself into a liar: “I created an external person who had very little to do with the real me. As I didn’t know how to keep my creation and my person apart, the damage had consequences for my life and creativity far into adulthood. Sometimes I have to console myself with the fact that he who has lived a lie loves the truth.” In your clinical experience, what are the relational issues that creative people deal with, in particular with family members, romantic partners, and friends?

Palumbo: This is a huge issue, but to reduce it down to an appropriate explanatory length, in my experience most creative peoples’ intimate circle—family, romantic partners, and, to a lesser extent, friends—are a significant aspect of their lives, and not always in the best of ways. The financial struggles that often accompany a creative person’s career strivings can have a powerful impact on that person’s life partner, since their fortunes are, in a sense, combined. For an additional “turn of the screw”—crediting Henry James—this burden of financial troubles becomes even more impactful if the writer has children. In addition to money worries, the emotional toll that creative ambition takes on the artist can make him or her hard to live with. The ups and downs of a creative career, and their resultant stresses, are coexperienced by the life partner. I have had many romantic partners of creative people in my practice complain that they can no longer tolerate living with the uncertainty and “emotional roller-coaster” of their mates’ ambitions. Even quite successful artists find that their success can cause familial disharmony, due to a requirement to travel extensively, or to the stress of being in the public spotlight. As my patients who are themselves the adult children of famous artists regularly complain, growing up in that particular circumstance was not easy.

I am often reminded of a quote by Robert Frost: “The one thing all nations of the earth share is a fear that a member of your family will want to be an artist.” As someone who left engineering school to seek my fortune as a Hollywood writer, I can certainly attest to that. Among others in my family, my grandmother routinely lit novena candles to save my soul. (This happened every Sunday at her Catholic church, named Our Lady of Perpetual Sorrow. I wish I were witty enough to have made that up.)

Dennis Palumbo is a licensed psychotherapist in private practice, specializing in working with creative patients. His award-winning series of mystery thrillers—the latest is Panic Attack—feature psychologist and trauma expert Daniel Rinaldi. He is also the author of Writing From the Inside Out, as well as a collection of mystery short stories, From Crime to Crime. Recently, he served as Consulting Producer on the Hulu limited series “The Patient.” Formerly a Hollywood screenwriter, Palumbo’s credits include the feature film “My Favorite Year,” for which he was nominated for a Writers Guild Award for Best Screenplay. He was also a writer for the ABC-TV series “Welcome Back, Kotter,” among numerous other series. His short fiction has appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, The Strand, Mystery Weekly, and elsewhere. His work helping writers has been profiled in The New York Times, Premiere Magazine, GQ, The Los Angeles Times and other publications, as well as on NPR and CNN.

August 21, 2024

In this Interview with Monica Hadley on Writers' Voices Leo Daughtry Remembers Midcentury South in 'Talmadge Farm

Listen here

Former lawyer and politician, Leo Daughtry, stopped by to share his debut novel, Talmadge Farm. Set in North Carolina in the 1950’s, Talmadge Farm follows the lives of Gordon Talmadge, a wealthy landowner, and the two sharecropping families who reside and tend to the tobacco farm on his property.

As readers delve into the novel, they learn how these three families are affected during a period in time when the culture and economy were shifting in the Deep South. As far as the inspiration for this book, Daughtry said, “Well, I wanted to let people know about how farming was in the 50’s, early 60’s. Most people were born after the war was over and I was born before the war started. I lived at a time when all the farms in my area were farmed by what we call sharecroppers… I wanted to tell their story about how their life was very poor… and how it ended, how sharecropping finally ended in this area and were replaced by what we call migrant workers, workers who came down from Florida, up the coast, stopping in South Carolina and migrating up to North Carolina, then on to Virginia, and up that way.”

August 19, 2024

Story Merchant E-Book Deal: The Invisible Hand: A Pareto Sisters Mystery by P.E. Klein

AVAILABLE ON AMAZON

Ever heard of Fenton Pareto? He's only the coolest private investigator around. But when the Bay Area turns into a nightmare of disappearing jewels, tormented pets, and mysteriously glitching cellphones, even he needs some backup. Enter Charlie and Clarke Pareto, his super-smart daughters, ready to take on the mystery that's stumping their dad.

Think you've got what it takes to crack the code? Then strap in for a rollercoaster ride with the Pareto sisters, as they match wits with a remote enemy who's controlling the chaos like a puppet master. And just when you think it couldn't get crazier, the sisters get framed for a crime they didn't commit!

But, how are the sisters supposed to clear their names while dodging booby traps, weaponized music, and dangerous QR codes? With a hefty dose of courage, a dash of stubbornness, and a custom-made secret weapon - their razor-sharp minds.

The Invisible Hand is the first heart-stopping book in an epic trilogy, where the Pareto sisters dive headfirst into a world of secrets, danger, and shocking discoveries. Inspired by the author's own experiences in Menlo Park, California, this story will have you flipping pages like there's no tomorrow.

So buckle up, detective, and remember: in this game, nothing is as it seems.

August 16, 2024

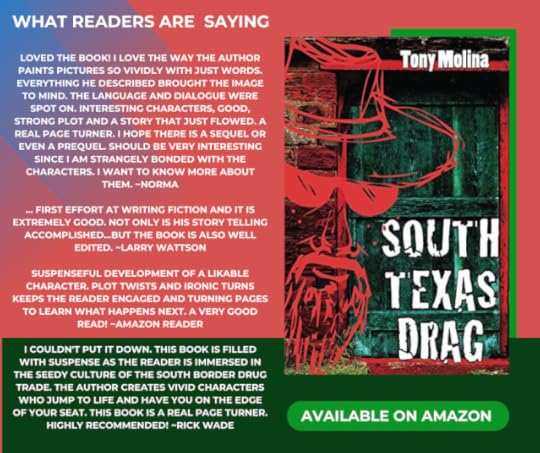

What Readers Are Saying About Tony Molina's South Texas Drag

AVAILABLE ON AMAZON

EXCERPTS

My eyes open and I can feel the heat of the day. The air in South Texas is like a hot skillet, pressing you down into the dirt. It’s all we can really count on in South Texas, the heat.

I grab both Glocks and the two mags, all loaded up with seventeen rounds apiece. My cold steel fila and berretta .25 cal. are tucked in my boot, and my cover knife is secure on my belt. Everybody, from the cops to the crooks, always takes my belt knife but they usually miss my cold steel knife with the Tanto blade, which is my best weapon. If you have a gun at your waist and I have my knife, you will never clear leather. My tio’s right hand guy, El Machete, took him, barely alive, to a tree where he tied him up, cut a hole in his stomach, pulled out about four feet of guts, and tied those to a stake. That way, the dude could see what the coyotes were having for dinner. I pull up to my crew’s digs. “I see you, joto. Don’t try to flank me, and I can see Paco on the roof. Why do you guys do this every time? Paco,” I yell up, “don’t wear your hunting camo on a tin roof. I saw you when I hit the hill behind your house, pendejo.”

We picked the package up at the Cadillac Bar in Nuevo Laredo from a horse trainer. He explained the ice chest had horse semen from some famous racehorse. It was worth a lot of money, and we had a timeframe of six hours before it would be worthless. Sounded easy, turned into a shitstorm—but we pulled it off. Can you imagine going to jail in Nuevo Laredo Mexico for trafficking horse love juice? Embarrassing.

“Untape her mouth.“

Rigo does, and I ask her name.

“Loraine, motherfucker!“

“Orale, Loraine. Bit of a fucked up name for a Mexican chick, but okay.” I’m all focus, deep breathing and everything. Good thing I got my yoga in. Then I notice it: she’s wearing Versace jeans, a Vera Wang top, and a badass A. Lange & Sohne 18-karat red gold watch. Something’s not right. That isn’t a gift you give any girlfriend….

August 14, 2024

New From Story Merchant Books Leo Daughtry's Talmadge Farm

TALMADGE FARM is a sweeping drama that follows three unforgettable families as they navigate the changing culture of North Carolina at a pivotal moment in history. A love letter to the American South, the novel is a story of resilience, hope, and family—both lost and found.

AVAILABLE ON AMAZON

It’s 1957, and tobacco is king. Wealthy landowner Gordon Talmadge enjoys the lavish lifestyle he inherited but doesn’t like getting his hands dirty; he leaves that to the two sharecroppers – one white, one Black – who farm his tobacco but have bigger dreams for their own children. While Gordon takes no interest in the lives of his tenant farmers, a brutal attack between his son and the sharecropper children sets off a chain of events that leaves no one unscathed. Over the span of a decade, Gordon struggles to hold on to his family’s legacy as the old order makes way for a New South.

About the Author

Leo Daughtry is an attorney, businessman, and former Republican state lawmaker. His debut novel reflects on the dreams and struggles of the American South, made more poignant by Leo's personal experiences growing up among the tobacco fields of Sampson County, North Carolina.

What People Are Saying“Talmadge Farm is a classic. Through the lives of a farm owner’s family and their sharecropping tenants, Leo Daughtry weaves a story about the emerging South. This is a story of triumph and tragedy, of good and evil, and finally reconciliation. A true morality play."— Gene Hoots, former tobacco executive and author of Going Down Tobacco Road“Set in North Carolina in the 1950s and 60s, Leo Daughtry’s story gives readers a cast of flawed characters that elicit sympathy, anger, love and hate. The Talmadges, landed gentry, and their two sharecropper families try to adjust to the changing political, economic and social landscape of the decade. Gordon Talmadge commits one mistake after another, ultimately destroying the legacy handed to him, as his loyal wife Claire stands by his side while the sharecropper families – one Black, one white – are ultimately driven off the farm for better and for worse. A page turner. — George Kolber, author of Thrown Upon the World, and writer/producer of Miranda’s Victim“In this stirring novel, Leo Daughtry creates a big, complicated portrait of family, place, race, class, and greed. Set in North Carolina, Talmadge Farm tells the story of three intertwined families. Daughtry delves deep into the heart of his characters. You’ll almost forget that you don’t know them personally; this story feels that real.”— Judy Goldman, author of Child: A Memoir and Together: A Memoir of a Marriage and a Medical Mishap