Kenneth Atchity's Blog, page 14

September 27, 2024

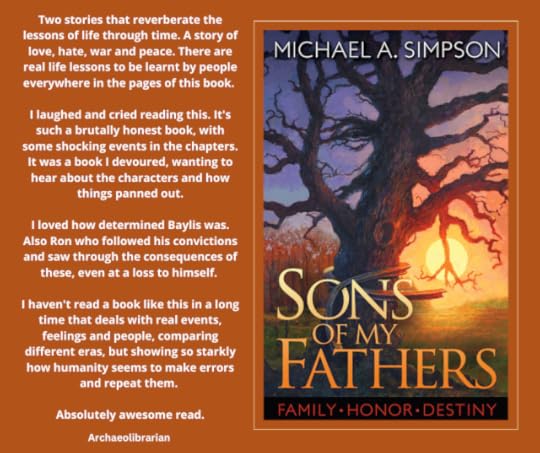

Michael A. Simpson's Sons of My Fathers Five Star Review!

AVAILABLE ON AMAZON

Synopsis:

Sons of My Fathers, based on the true story of author Michael A. Simpson’s family, is a multi-generational journey that intertwines two dramatic stories set one hundred years apart—the heroic saga of 19-year-old Ulysses Simpson who, when "hell comes to Georgia," joins his father on a course of revenge, a path that will forever change the destiny of their clan. And the true tale of another young Simpson man six generations later who, despite his moral reservations, enlists in the U.S. Army, following in the footsteps of his father who was a WWII Marine Corps combat veteran and one of the legendary fighting force's elite instructors during the Korean War.

When Ron volunteers as a "walking dead"—the term for those who fly unarmed medevac helicopters during combat because of their high mortality rate—but is instead assigned to fly a Huey gunship, he fights a personal war with himself over whether to keep a century-old family oath. As his brother Michael comes of age and experiences his first love, Ron's fateful decision forces him to confront his family's past and risk sacrificing his own future, an act that ultimately sets a landmark precedent for "soldiers of conscience" who would follow him in military service.

Deeply personal and compellingly written by the younger brother in this story, the book is uniquely set against America's involvement in two great civil wars—our country's own conflict in the 1860s and Vietnam in the late 1960s. It is an evocative journey into the author's family history and the universal themes central to it—the bonds of family and star-crossed love, duty versus faith, the true nature of patriotism and conscience in war, and the turbulent end of innocence. Rich in emotional textures, Sons of My Fathers is a transformative and timeless coming-of-age narrative.

Other than his mother’s lullabies, the whistle of the Dixie Flyer was the earliest sound Michael Simpson could remember hearing.

Since the time of Baylis Simpson and the Confederacy, the locomotive’s melancholy cry had announced its passage through Forest Park, a quiet Georgia town of hard work and modest dreams snuggled on Atlanta’s southern doorstep. The rail line pierced through the heart of this blue-collar community, running parallel to Main for several blocks before bending south, just before the street emptied out onto Jonesboro Road in front of the Fort Gillem Army base. The road was the same one that Rhett Butler and Scarlet O’Hara used for their imaginary escape from Atlanta. The fictional Tara plantation was said to have been located just a short stride down its blacktop.

Every night of Michael’s young life, the Flyer’s whistle beckoned him, filling his imagination with a long-vanquished landscape of graceful mansions and stately plantations, of hoop-skirted ladies who thought about things tomorrow and men who frankly didn’t give a damn.

5 out of 5 (exceptional)

Independent Reviewer for Archaeolibrarian - I Dig Good Books!

I'm not usually a 5 star reviewer but.....

Two stories that reverberate the lessons of life through time. A story of love, hate, war and peace. There are real life lessons to be learnt by people everywhere in the pages of this book.

I laughed and cried reading this. It's such a brutally honest book, with some shocking events in the chapters. It was a book I devoured, wanting to hear about the characters and how things panned out.

I loved how determined Baylis was. Also Ron who followed his convictions and saw through the consequences of these, even at a loss to himself.

I haven't read a book like this in a long time that deals with real events, feelings and people, comparing different eras, but showing so starkly how humanity seems to make errors and repeat them.

Absolutely awesome read. Thank you Michael A Simpson!

* A copy of this book was provided to me with no requirements for a review. I voluntarily read this book, and my comments here are my honest opinion. *

Michael A. Simpson is a writer, director and producer of award-winning documentaries and feature films (whose credits include the Oscar-winning “Crazy Heart,” “Hysteria,” and “Kidnapping Mr. Heineken”). He continues his older brother Ron's tradition of questioning authority and speaking out against social and political injustice, as his friends, both real and virtual, will attest. He grew up in dark rooms watching flickering images on a screen, is a connoisseur of raisin oatmeal cookies, a walking storehouse of music knowledge and trivia, finds reasons to get his passport inked whenever possible, and remains a “rebel without a pause.” "Sons of My Fathers," based on his family's history, is his first book.

September 25, 2024

ROBERT RIVENBARK INTERVIEW WITH THE HAMMER

Robert's prize-winning novel THE CLOUD. THE CLOUD was honored as one of the 20 best books of 2023 by Bookworm Reviews, and it's currently in development as a feature film with manager/producer Ken Atchity, CEO of Atchity Productions and Story Merchant books.

Robert is is launching a crowdfunding campaign to raise the budget to shoot a three-minute film trailer with an A-list actor attached to trailer and feature film. Stay tuned for future broadcasts to learn how you can participate and become a producer on the project.

When Everyone's A Virtual Reality Slave, Who Can Free The Human Soul?

Get The Cloud: A Speculative Fiction Novel On Amazon Today!

September 23, 2024

Story Merchant E-Book Deal Michael A. Simpson's Sons of My Fathers

FAMILY * HONOR * DESTINY

A transformative and timeless journey into one family's personal history during two controversial wars.

AVAILABLE ON AMAZON

Michael A. Simpson is a writer, director and producer of award-winning documentaries and feature films (whose credits include the Oscar-winning “Crazy Heart,” “Hysteria,” and “Kidnapping Mr. Heineken”). He continues his older brother Ron's tradition of questioning authority and speaking out against social and political injustice, as his friends, both real and virtual, will attest. He grew up in dark rooms watching flickering images on a screen, is a connoisseur of raisin oatmeal cookies, a walking storehouse of music knowledge and trivia, finds reasons to get his passport inked whenever possible, and remains a “rebel without a pause.” "Sons of My Fathers," based on his family's history, is his first book.

Michael A. Simpson is a writer, director and producer of award-winning documentaries and feature films (whose credits include the Oscar-winning “Crazy Heart,” “Hysteria,” and “Kidnapping Mr. Heineken”). He continues his older brother Ron's tradition of questioning authority and speaking out against social and political injustice, as his friends, both real and virtual, will attest. He grew up in dark rooms watching flickering images on a screen, is a connoisseur of raisin oatmeal cookies, a walking storehouse of music knowledge and trivia, finds reasons to get his passport inked whenever possible, and remains a “rebel without a pause.” "Sons of My Fathers," based on his family's history, is his first book.

September 19, 2024

Julie Sara Porter of Bookworm Reviews Robert Rivenbark's The Cloud: Involving High Tech Science Fiction Excels at Presenting Microcosms of Futuristic Tech Heavy World

In 2040 California, VR designer Blaise Pascal is an employee of The Cloud, a tech corporation that practically runs the world. He is assigned to tweak a game which contains an addictive drug that controls The Slags, the lower classes. As he ascends higher within The Cloud, he is made aware of the company's nefarious schemes while he is torn between two women: Mitsuko, his ambitious supervisor and Kristina, a member of the Resistance against the Cloud.

The book is excellent at capturing the futuristic world from the oligarchical structure to the little details like wardrobe, slang terms, and recreational activities. Rivenbark put a lot of care and effort into this world.

One of the ways that he accomplishes this is to portray each character as representations of their world. Mitsuko represents The Cloud: narcissistic, cold, artificial, and dehumanized. Kristina represents The Slags: selfless, warm, authentic, and completely human. Blaise is both, a former Slag who worked his way up to The Cloud and now is compelled to fight against it.

The Cloud presents a world that is so caught up in technology, that only a few remember a world without it. It is those people who will rebuild society when the technology is gone.

Get The Cloud: A Speculative Fiction Novel On Amazon Today!

FULL REVIEW:

Spoilers: It's always a treat when I read one book, then I read its polar opposite. I read two books set in the 2040s, Mark Richardson's Malibu Burns and Robert Rivenbark's The Cloud. Both are set in California, both after times of political and environmental unrest and both have worlds in which technology and AI have taken over. However, in execution the two books go in opposite directions. Malibu Burns doesn't concentrate on the futuristic world so much as it does on the mindscape of its lead protagonist. The Cloud does involve interesting characters but it concentrates more on how this futuristic world affects them. Malibu Burns is strong on character and The Cloud is strong on setting and world building.

Blaise Pascal is a VR designer who works for The Cloud, the tech corporation that practically runs the world. He is currently working on Gilgamesh V, the latest game to appeal to The Slags, the lower classes who aren't connected to The Cloud (like Blaise once was). His director, Minsheng is impressed with Blaise's work but wants him to tweak the game to include an addictive drug which will control The Slags. As Blaise climbs higher in the corporation and spends time with the Slags, he begins to see the corruption, dehumanization, and mass murder that his superiors are planning. He is caught between the luxurious technology driven world that he wants and the honest connections of the human driven world that he needs.

Many of the characters are well written, Blaise in particular, but mostly they serve as microcosms of the society in which they live. They are shaped and changed by the universe around them and we see the strengths and weaknesses of the world because of how it affects them.

Blaise is the person in the middle. He came up from the low tech Slag world leaving behind a missing father, a mentally ill and deceased mother, and intense poverty to move to the high rise Cloud world. He hooked himself up to the devices that monitor his actions and created VR simulations for the people that he was once a part of.

While Blaise is a huge part of how the Cloud works, he is not exactly enamored with his surroundings. He is a military vet who has seen his share of bloodshed in the name of the corporations and governments who pulled the strings. He also is mourning the deaths of his wife and daughter, the last people he felt connected to. Now he buries himself in work and a sardonic attitude. While his remarks are humorous (for example when his immediate supervisor, Mitsuko gives him an order, he remarks, "I ignored you the first time."), they reveal a cynical detachment for a lifestyle that provided him with creature comforts but little else.

Blaise's only relief is the downtime he gets when he goes to the Slags towns, perhaps his only means of any type of companionship and the only time that he can be himself without being spied upon. It is here that he meets Kristina, who is part of a resistance group against The Cloud. She tells Blaise some important information about his mother and what his role is to be in this revolution. As Blaise starts to see the Cloud for its true colors, as a dictatorship, he becomes an active participant in ending it by being the revolution's inside person and saboteur.

Unfortunately, Blaise's new role as rebel coincides with his promotion through The Cloud and his involvement with his supervisors, Mitsuko and Minsheng and the shady directors behind them. The threats and underhanded deals that collapse the lower classes are made all too real. In one chapter, Blaise is nearly tortured by mantises, cybernetic insects which inject their victims with a painful venom. He then watches in horror as those mantises are then used on people including many of the rebels.Blaise becomes involved in a love triangle between Kristina and Mitsuko. While normally, I don't like love triangles because I find them cliched and often unnecessary with The Cloud, I will make an exception because of what each character represents.

Mitsuko represents The Cloud. She is a narcissistic ambitious person who uses many that come near her. In her world, relationships can only be made on a superficial shallow level. Because of this, terms like "friends, "family," and "lovers" are mere words. Because they are just words without feeling around them, those terms can be redefined however they see fit as Mitsuko reveals during one of the few times when she displays some reality beyond the materialistic driven persona that we have already seen. She is a woman who has been hurt in the past, knows what it's like to struggle to get to where she is, but doesn't care. She lost her humanity and compassion for others and sees the people around her as allies for or obstacles against the company that she reveres and even worships. She represents the worst that Blaise could be.

Kristina represents the resistance, the rebels that are still in touch with their humanity. They have technology in that they were able to build a functioning self-sustaining community, but all of their technology is used to benefit a larger society, rather than controlling it. They, particularly Kristina, haven't lost who they are or the love for those around them.Kristina cares about her fellow rebels and family. Even though she is in love with Blaise, she isn't afraid to call him out on the actions and the people behind The Cloud's actions.

Kristina has a strange ability to read into other's souls. This ability opens up possibilities that when society heads further into progress and science, what was once considered magic could be rediscovered.It also gives Kristina deeper insight into people. She sees beyond the surface that Mitsuko sees. She sees into Blaise's past and how he really feels. She makes a real connection with him, a connection that Blaise thought was lost.

The Cloud shows us a world that becomes so intertwined with its technology, that only the very few remember what it means to be human and it is them who will rebuild the world once that heavily technological superficial world is gone.

via Bookworm Reviews

September 17, 2024

Silver's Reviews Gives Leo Daughtry's Talmadge Far, Five Stars

1950’s -1960’s - North Carolina - things are changing, but also staying the same.

Three families - one rich tobacco farm owner and two sharecroppers.

Gordon Talmadge has no regard for his sharecroppers or anyone that is in a lower class than he is.His son is exactly like him. When his son Junior gets in a confrontation with the sharecropper’s son, who do you think everyone will believe?

Talmadge Farm kept me turning the pages with Mr. Daughtry’s descriptive writing and wonderful characters.You will become part of the character’s lives - their sorrows and their joys.

It does have more sorrows for most of the characters than joys, but historical fictions fans will enjoy Talmadge Farm as you live through what was happening and changing in the South during this time and with wealthy landowners and those who worked for them.

In the end, though, you will be left with a warm feeling because of the closeness the families share and their hopefulness. 5/5

Read Snowblind's Prologue and Sample Chapters!

There is a wolf in me... fangspointed for tearing gashes... a red tongue for raw meat... and the hot lappingof blood — I keep the wolf because the wilderness gave it to me and thewilderness will not let it go.fromWILDERNESS by Carl Sandburg

PROLOGUEHis mother saw him staring andturned her eyes away.Hecould see she was afraid. Afraid of his hunger. Afraid of the wrath of thesilver-bearded Father.Thenight wind howled over the sod roof, moaned at the icy window. Three days hadpassed, and still the old man had not returned. They feared, again, he wouldcome back with nothing. The traps had been covered in snow. They had no baitleft — they had eaten everything.Onthe table the sacred candle burned brightly. The candle could only be burnedwhen the Book was being read. This was a Law of the Father. The Law could notbe broken.Theeight-year-old boy read the Book aloud:"Whatare human beings, that you make so much of them, that you set your mind onthem, visit them every morning, test them every moment?"Theboy paused, gazed at the candle's dancing flame. The Father had said the wordsof the Book would fill his empty belly. If he did not learn them, he would noteat.Inhis mind he repeated the words he had read. What are human beings...Helooked down at his mother. She sat on the caribou rug, on the dirt floor, inthe light of the flickering flame. Her dark skin glowed warmly, her hair hungblack as night.Howcould her belly grow so large when they had no food to eat?TheFather had taken her from an Inupiat village, on an island in the Arctic sea.She had long ago learned the language of the Book, but when the Father was outon the hunt, she would speak to herself in a tongue the boy did not understand.When he questioned her, she would point to the scar on her face, the scar fromthe Father's knife.Theboy was not allowed to know her words. The Book would tell him everything. TheBook was all he would need.Heturned a page and read another passage."Amortal, born of woman, few of days and full of trouble, comes up like a flowerand withers, flees like a shadow and does not last. Do you fix your eyes onsuch a one? Do you bring me into judgment with you?"Hepaused again, gazed absently at the flame, his lips moving in silence. Stillthe hunger gnawed.Helooked again at his mother. She was stringing tiny blue snail shells on stiffthreads of sinew. The shells would adorn the sackcloth doll that rested on herlap, a family heirloom whose ivory head had lost its amber eyes.Shenoticed the boy staring. Again she looked away.Hishunger had turned on itself, clawing in his belly like a ravening wolf. He fedthe wolf the words of the Book."Whyis light given to one in misery, and life to the bitter in soul, who longs fordeath but it does not come, and digs for it more than for hidden treasures, whorejoice exceedingly and are glad when they find the grave?"Theboy stopped reading. He closed the Book. His pulse pounded, his hands trembled.The wolf would not be sated.Hestared until his mother finally looked at him.Fora long moment she peered into his eyes. Then she rose to her feet, holding herswollen belly, and went to the window. Out in the cold night, wind-blown ghostsof snow whirled over moonlit tundra.Surelyhe would not return tonight.Shewalked to the table, leaned over and blew out the candle. The sod house fellinto darkness.Theboy waited anxiously.Hismother's hands were always warm. Even in the cold she wore no gloves. She heldhis face tenderly, then took his trembling hand and led him through thedarkness of the room.Faintgray moonlight fell across the bearskin bed. His mother lay on her side andpulled him down to her, speaking the strange, forbidden words.Sheopened her dress, lifted out a pale, pendulous breast. His hands gropedhungrily. He pressed his wet mouth to the dark aureole, his strong teethseizing the nipple. The boy sucked ravenously. Soon, warm gorging milk flowedforth, bathing his tongue, filling his mouth, seeping out over his chin. Hesucked the breast and lapped the milk, and held her body tight.Minutesswiftly passed, the boy's hunger unrelenting. At last he pulled away, panting,his open mouth dripping spittle. Slowly, his languid eyes opened.Hefroze, gaping into the morbid light of the moon."Whatis it, Job?" his mother asked. She turned to the icy window.Outside,in the darkness, the Father stood staring, his starving eyes glaring like awolf.

1. Sunlight flared off the glistening snow,blinding her path to the turn. For a flashing moment, fourteen-year-old KrisCarlson couldn't see the flag. She cut too late, displacing snow instead ofarcing the curve, and for a few frightening seconds lost her balance, nearlyspilling over the icy curl. She recovered quickly into the flat, her newstiffer skis gaining speed and stability for the run into the next turn. Withluck, she'd pick up the lost seconds in the final sprint. She'd have to. Sixpoints behind the fifteen-year-old downhill leader, Claudia Lund, she couldn'tafford another mistake.Thenext turn, even tighter than the last, glittered with surface ice, sheered to asheen. Kris leaned deep into the arc, adjusting her radius in the middle of theturn with a subtle twist of her ankles. Her shoulder banged the flagpole as shecleared the twist, hopping into a quick series of steep moguls, her kneesbobbing like a set of springs.Finalturn. She knew this one, she'd skied it in her mind a hundred times. She heardher father's voice: "Load the tail, skid the shovel." There was afine line between going all out and not making any mistakes. It was a lineshe'd have to cross. She banked full speed into the long turn, loading up hertail, building critical power for the final sprint.Krisshot out of the turn at record speed. The crowd roared — she had it locked.Soaring into the final run, she hugged her knees and schussed for the finish.Agrin grew across her face. Her dad would be at the bottom. He was always there,waiting for her.Shewanted nothing more than to make him smile.* * *The old moose trickled a bright redtrail of blood in the snow. Hunks of flesh had been torn from its body, itsmatted fur glistened with sweat. It lumbered into the narrow ravine, tottering,weaving, out of breath, stopping at last at the frozen bank of the surgingSawtooth River.Icefloes churned and heaved in the current with a roar like muffled thunder. Themoose drew a kind of power from the sound, the vibrations rising up through theanimal's trembling limbs. The surge of strength suffused its body, steeling thebeast for battle. The regal moose raised its crown and turned to face thewolves.Lopinglightly over the shelf ice at the shore, the five silver, silken huntersquickly circled their prey. They snarled, salivating, growling guttural andwild. The moose whirled, stumbling, its labored breath trailing dragon cloudsof fog. They had circled before, and the bull had escaped. Now they wereclosing in for the kill.Thedark-eyed lead wolf lunged, tearing a gash in the great beast's rump. Anotherseized its leg, its razor fangs cutting deep. The moose groaned and scooped itstowering head, impaling the animal in its tangled rack. The wolf yelped,staggered back. The moose charged, stomping, its pounding hooves crushing thecowering wolf's ribs.Thepack backed off. The wolf was dead. The moose trotted off up the frozen shore.Snowfell softly in the windless ravine. Ahead, high above the rumbling Sawtooth, ablack wooden bridge spanned the gorge. The moose clambered up the craggy slopeas the wolves resumed their hunt.* * *Kris was traveling with her fatherand her seven-year-old brother, Paul, in her father's red Chevy pick-up, comingdown through the mountains from Garrison Pass. Her new skis rattled in the bedof the truck. Kris had kept on her lilac snowsuit, zippered to the neck; herblack hair hung straight to her shoulders, her bright blue eyes were smiling.She had won the Women's Junior Downhill race, first place in the girls'twelve-to-fifteen year age bracket, setting a personal best on the half-milecourse down the north slope of Dome Mountain. The ski resort, on the edge ofthe Alaska Range, fifty miles from their home in Healy, always held the firstdownhill races of the Spring season. Kris was already looking forward to thenext. She had her eye on the Alaska Alpine Championships."Dad?Do you think Mom will come to the Winterhaven trials?"Herfather studied the oncoming road through the falling veil of snow. "Shewon't want to miss it, Sweety. Not after we show her what you won today."Paulsat between them, twisting the trophy in his small hands, trying to unscrew thetiny gold skier from the mount."Pauly!"cried Kris, pulling the trophy away from him."It'sa boy, it's not a girl," he said.Krisexamined the figure. "You can't tell," she said."Ican tell," said Paul.Krisruffled his hair with her hand. He grabbed her wrist, pretended to bite it,growling. Kris tickled him."Nono no!" he shouted, squealing with laughter.Kristurned back to the road, a smile on her face. A black bridge appeared throughthe falling snow.

2. "The 'woo' bridge!" Krisexclaimed."'Woo'bridge!" echoed Pauly.Thetruck rolled onto the bridge, and a resonant "woo" sound rose up fromthe tires. All three passengers grinned, staring into the white wall of snow asthe deep bellow of the bridge filled their ears.Thenthe blood drained from their faces.Thecolossal moose came charging out of the whiteness directly toward them. Kris'sfather instinctively slammed the brakes and pulled the wheel. The truckcareened across the bridge, just missing the bloody, frothing bull, slidingpast it through a madhouse of leaping wolves. He hammered the brake, but theice had them. They continued to slide, smashing through the guardrail and outover the gorge.Krisscreamed, a high shrill scream of unblinking terror, as they dropped throughthe air toward the river of ice.Thetruck pierced the tumbling floes with a bone-crunching jolt. Kris's headbounced against the dash, her body flung wildly as the seatbelt grabbed. Sheglimpsed her father's bloody, vacant face as the truck plunged headlong intothe frigid water. They plummeted swiftly, sinking in the current, the cabraging with the inflowing torrent.Paulscreamed and gurgled as the water engulfed him. Her father tossed about, limpand unconscious. Kris tore at her seatbelt. The water rose quickly to herchest, neck, chin, mouth —Shewas underwater, the truck tumbling in the current. The snowsuit miraculouslykept her from freezing. Feeling blindly, she found the buckle, unlatched herseatbelt. Pauly clawed at her side. She opened her eyes to see him, and thefrozen water clamped her eyeballs with icy talons. She saw her brotherthrashing in the glacial murk. She reached for him, fought to undo hisseatbelt. Her eyes went gelid, seared with the cold. She undid the belt, thenturned, grabbed for the door handle. The door was jammed. She yanked on thelever, it wouldn't budge. The window crank, too, was stuck. The door had beencrushed when they'd broken through the rail.Kris'slungs burned. Her vision darkened.Outof the dark came a glimmer of gold. She grabbed the trophy, slammed it againsther window. Once. Twice. The third time the window shattered. She scrambled outquickly, shards of glass tearing her snowsuit, frozen fingers of water grippingher. She reached back through the window for Paul.Hewas gone.Shepeered into the murk, her eyes stinging, the icy water clawing her corneas.Groping wildly, she could not reach her brother.Kriswas out of breath.Shepushed away from the truck, pulled frantically for the surface, ramming hardinto a ceiling of ice. Unable to see, she groped along, feeling for a gap. Herhands fell on the snaking roots of a tree trunk. She climbed the roots, an icefloe pounding at her back. At last she emerged from the teeth of the river,gasping, coughing, screaming for air. She crawled off the log onto the broadsnow surface of a massive floe.Pitch-blacknight had fallen in the middle of the day. Kris could not see — her eyeballshad been frozen into rocks by the cold. With a violent shiver, she collapsed,and the raging Sawtooth carried her away.Two hours later, in the river townof White Circle, Kris Carlson's body was hauled from the ice.

3. They fear me. I have torn them in mywrath.They haveno hunger these men who hunt with dogs. They tear me from my mother'swomb and drag me through the snow. They gape at me with their mouths. Theystrike me with their fists. They mass themselves against me. They seize me bythe neck and dash me to pieces. They cast me into the mire, and I become likedust and ashes. My skin turns black and falls from me, and my bones burn withheat.Let themhope for light but have none. They'll never see the eye of day, the eye of dayis shut. I know there is no light. I know freedom comes with blood. I know thewolf. The wolf will not betray me.I slashopen their kidneys and show no mercy. I pour out their gall on the ground. Iburst them again and again. I sew sackcloth upon my skin. I eat flesh like awolf. My strength is in the ice. My strength is in my loins. My strength is inthe muscles of my belly. I make my tail stiff like cedar; the sinews of mythighs are knit together. My bones are tubes of bronze, my limbs like bars ofiron.I am thefirstborn of Death.These menare full of fear. They will know my power. They will die, just like the rest.All ofthose who fear the wolf will perish by my hands.I will eatthem. All of them.* * *In the clear, cold, aurorean night,across the frozen tundra, three Inuit dog sleds glided over the snow. Thestampeding teams of Alaskan huskies pumped clouds of steam into the brisk nightair, while two Inuit mushers ran, rode, and pushed the sleds behind them.Inthe first sled, Shakshi, a large Yakuutek hunter with high Mongoliancheekbones, leathery, wind-burned skin, and an icy black moustache, locked hisdark eyes on his wheel dog, Tiuna, whose silver tail hung low. Roluk, the hugeSiberian lead dog at the head of the team, threw a glance back at thefreeloader, yapping in complaint. Shakshi shouted a command, yanking histugline. The dogs came to a halt.Thesecond and third sleds drew to a stop behind him. The musher of the second,Anokuk, a broad-faced Yakuutek with a rifle over his shoulder, turned hisslitted eyes behind him. The third sled, with its full gangline of pantingdogs, was riderless.Lashedto the sled was a giant cage.Shakshidismounted. He walked up the line of his dogs, slowly, menacingly. When he cameto Roluk he paused; like a priest giving benediction, he touched the lead dog'shead with the back of his hand. The dog barked sharply, once. The mushercontinued slowly down the other side, past the swing dogs, the team dogs, theheavy pullers in the middle of the line. He paused at last beside Tiuna,staring down at her. The wheel dog whimpered, sullenly. She knew she had offended.Shakshi leaned over and smacked her — a wallop on her rump. Tiuna snapped backto life.Shakshireturned to his sled, eyeing his comrade. Anokuk nodded back toward the thirdsled. A guttural groan like the sound of an animal emanated from the giantcage.Thetwo hunters approached warily, Anokuk un-slinging his rifle.Thecage, tightly lashed to the sled, was made of thick, interwoven saplings.Inside, barely visible in the feeble light of the moon, a massive form laybound in hides and chains.Thecreature stirred.Shakshinodded to Anokuk. The narrow-eyed hunter raised his rifle barrel, aimed throughthe bars, and fired.Theshot rang out across the tundra. The dogs grew silent. Shakshi and Anokukglanced at one another — the groans had stopped.Thehunters drew close to the bars, peered into the darkness of the cage. A bloodred tranquilizer dart had stuck through the pile of hides. The mammoth body laystill as a corpse.Shakshinodded to his comrade, and the two men returned to their sleds. The dogs jumpedto their feet, barking with freshened vigor. Tiuna, of all of them, looked mostready to go. As he mounted the whalebone runners and reached for his tugline,Shakshi noticed something on his sled. A hide had blown loose. Beneath it, thelifeless eyes of a Yakuutek stared out at him. A chunk of the dead musher'scheek was missing, gouged from his face. Shakshi touched the wound with hisgloved hand. Teeth marks scarred the torn flesh.Shakshicovered the head, lashing the hide securely to the sled. Then he gave thecommand to his dogs and they bolted into the night.

4. Fairbanks International Airport hadjust come into view when the air traffic controller's voice came over theheadset. "Charlie Five-five, this is Fairbanks Tower, do you read me,over?"JoshMarino recognized Dean Stanton's voice, gravelly and low like the grumbling ofa lion. "Roger, Fairbanks," Josh replied, "this is CharlieFive-five, requesting landing, over." He pictured the cotton-haired old mansitting in the tower, his crumpled brown-bag face and heavy-rimmed glasses, acigarette dangling from his lips as he growled into the mike."CharlieFive-five, drop to twelve hundred and turn right zero-three-zero. You haveRunway Three.""Roger,Fairbanks," Josh answered. "When are you gonna quit smoking?" hewanted to add, but didn't. The old man will probably die with a cig in hismouth. "Descending to one thousand two hundred feet," Josh repeated."Turning right zero-three-zero for the straight-in to Number Three,over."Thetwenty-four-year-old pilot flew his company's single-engine Cessna back andforth from Anchorage to Fairbanks so often that hearing Dean Stanton's voicewas like hearing the subway driver call out your stop. "Charlie Five-five,you're cleared for landing." Josh wore a khaki jacket, high leather boots,and a belt-sheathed jackknife. His tousled black hair stuck out in feralprofusion from his red headband and his over-size earphones. He worked for asmall electronics company down in Anchorage, but still kept his one-roomapartment in Fairbanks, still considered the central Alaskan city his home. Hewas working toward his Masters in electrical engineering, and flew back to takeclasses at the University of Fairbanks on Saturday mornings twice a month. Andhe taught some classes at a local school, too, though that was more a labor oflove than anything else.Joshadjusted the flaps, grabbed the control yoke in his left hand and eased thethrottles back with his right. The plane banked and angled down toward thebroad stretch of runway ahead. The snow had been cleared and the black asphaltglistened. I could land this baby with my eyes closed, he thought, and for amoment, he actually tried it. One second the runway was fast approaching, thenext second everything went dark. A shiver of fear shot through the pilot; hiseyes popped open despite himself.Mustbe how my students feel, he thought, and wondered if he could teach them how toland a light plane. This would be quite a feat even with their eyes wide open —considering the fact that his students were blind.* * *Dean Stanton watched the Cessna 207Skywagon roll to a stop on Runway Three, then removed his glasses, rubbed hiseyes, and crushed his cigarette out on the linoleum floor. Behind him stoodDavid Adashek, the Fairbanks Chief of Police, a large, rock-chested man,bursting from his jacket and tie. Adashek was scratching his gray-haired head,staring down with a grimace at the collection of smashed butts scattered aroundStanton's feet.Stantonnoticed him looking. "Cleaning crew'll get 'em. Albert and Ace —Spic'n'Span. They get 'em every night.""Whydon't you just find yourself an ashtray, Dean?"Stantonlifted the headset off his ears, laid it around his neck. "FAA won't allowashtrays." He pointed to a sign next to the door. NO SMOKING.Adashek'seyebrows went up. He scanned the rest of the room. Three other controllers wereat work in the tower; all of them were smoking. The place had a heavier haze inthe air than the strip bar on Wolf Run Road. "I thought you boys had tofollow the letter of the law in here."Stantonlit up another one and blew out a lungful of smoke. "How long you been inAlaska, Chief?"Adasheknodded wearily. The ‘80’s seemed like a lifetime ago. "Long enough to knowI shouldn’t ask," he said.Hestepped up to the broad window, his eyes squinting into the arctic light. JoshMarino's tiny white Cessna was taxiing off the field. Beyond him, far off onthe horizon, silver clouds were forming above the snowy peaks. Adashek staredat the mountains, and for a long moment, didn't speak."It'sbeen two hours since they touched down," he said at last. "What doyou suppose is going on out there?"Stantonleaned back in his swivel chair, folded his hands behind his head."Knowing Jake, he's probably trying to make a deal on some furs.""Knowingthe Yakuutek," said the Chief, "he better not be looking for anybargains."

5. The Yakuutek hunter pointed hisrifle at Jake O'Donnell's head. Jake's eyeballs were wrenched to his temple,locked on the tip of the barrel. Not much more than a four-inch gap between thecold steel and the red-haired pilot's brains. This made using the brains aneven more difficult task than usual."Saysomething, Donny! He's gonna kill me, for Chrissake!""Saywhat?" asked his copilot. Donny was facing the other Yakuutek, who washolding a gun to Donny's chest. "I been talkin'. Nobody'slistenin'!""Tell'em I ain't lyin' goddammit!"He'ain't lyin'! Goddammit."Thehunter pressed the barrel of his gun into Jake's ear. Jake shuddered. Then,slowly, he turned his head, looked up the barrel into the Inuit's eyes."I...I told you. I 'ain't got the goddamn money!"Thehunter didn't speak. He wiped his brown hand down his shaggy black moustache.Was this fella angry or just trying to make up his mind?"Believeme, amigo. It's the truth, so help me God."Thebarrel didn't move. The Inuit's eyes stared deeply into Jake's. Jake struggledto take in a breath. If the gun hadn't unnerved him, the man's stare certainlydid.Jakeglanced at the big cage lying on the snow under the right wing of the GoonyBird, his aging twin-engine DC-3. Inside the cage, the mountain of a creaturelay barely visible, asleep under its cocoon of chains and hides."Look,"Jake said in a calmer voice, "you can keep the son-of-a-bitch. We'll sendsomebody back with the money.""Yeah,that's right!" chimed in Donny. "Keep the fucker. We'll let theSheriff collect him himself."Thetwo big hunters held steady.Jakeshot a nervous glance at Donny. "I don't think they want to keephim."Donnylooked at the cage. "Can't say I can blame 'em. Fucker don't look toofriendly."Avoice crackled from the empty cockpit."Hey,"Jake said, suddenly lighting up. "I bet that's the Chief now!"DeanStanton's voice continued sputtering from the radio. The hunters looked mildlycurious... or suspicious — it was hard for Jake to tell."That'shim, ain't it, Donny?""Yeah,that's Adashek all right. I can tell by the voice.""He'sthe badge with your money," Jake said. "We can talk to him, he'lltell you all about it." Jake began slowly backing toward the door to theplane. The hunter followed him with the barrel of his gun."Comeon," he said, leading him slowly back. "Right up here, we'll talk tothe man himself, I swear to God."Donnystarted moving with Jake, then stopped abruptly. His hunter had poked thebarrel of his gun into Donny's considerable belly. Donny raised his hands insurrender. "Okay, okay... you're right, you're right. It's only the Chiefof Police, no big deal, just a whole big pile of money waiting for you, waitingback there with your name on it and all you gotta do — " he suddenlygasped as the man again jabbed his gut with the rifle. Donny coughed, put hishand on the barrel, eased it gently back. "Okay, I'll shut up."Jakewas backing up through the doorway into the plane, the hunter following himwith his gun. Stanton's voice was still crackling through static on the cockpitradio. "Whiskey Four-O — ... do you... over."Thehunter followed Jake through the cockpit door into the nose of the DC-3, hisgun held to him like metal to a magnet."Niceand easy," Jake said, reaching for the radio mike. He slowly unhooked itand adjusted the frequency. Then he thumbed the button and spoke to DeanStanton."FairbanksTower this is Whiskey Four-O-Three, over."Jakewatched the hunter's black eyes as the air traffic controller's voice camethrough in reply. "Whiskey Four-O-Three this is Fairbanks Tower. We readyou loud and clear."* * *Dean Stanton handed his microphoneto Chief Adashek."Areyou all right, Jake? Did you find—"Jake'sstatic-broken voice interrupted him. "Just fine, Chief, except for the .22your friend here's been pointing in my face for the past half hour. Apparentlyyou and your Eskimo friends had a little miscommunication.""Idon't understand," the Chief said."Wellneither do I!" Jake shouted. "Mr. Yackety-Yack here thought he wassupposed to collect his reward money upon delivery of the prisoner."TheChief glanced uncomfortably at Stanton. "It's not money he's looking for,Jake.""What?!""There'sa Yakuutek man in jail here for manslaughter. If we get the prisoner back herealive, their man will go free. That's the arrangement we made with thetribe.""Manslaughter,huh. Gee, that's great, that's really great. Tell me, Chief, who'd the guy kill— a pilot?""Ifyou just explain to him—""Goddammit,you explain it to him! He sure as hell ain't listening to me!"Adashekglanced at Stanton, who shrugged his shoulders. The Chief raised the miketo his lips. "Shakshi, are you there? Can you hear me?"Adashekwaited, but heard no reply. "Is he there, Jake?""Yeah,he's here. He just don't talk much.""Thenlisten to me, Shakshi, please. It's very important that you do not cause anyfurther delay. We will release your friend when the prisoner arrives herealive. That was the deal. I urge you, he is extremely dangerous and must—"Ahowl came over the radio, followed by a blast and a burst of static."Jake?Do you copy?"Therewas no reply, just the steady crackle of static. The Chief looked frightened."Whiskey Four-O-Three, do you copy, over."Stantontook the mike back from him, played with the frequency. "WhiskeyFour-O-Three this is Fairbanks Tower, do you read me, over."Nothing.Adashekand Stanton looked at one another.

6. Jake's face had gone white. Hestared speechless at the radio. The hunter had slammed it with the butt of hisgun, knocking it loose from the console.Jakelooked up at him. "That little yell o’ yours is the most you've said allday."TheInuit, standing bent in the low doorway, wiped his long moustache again,glaring at Jake.Jakelooked past the hunter into the cargo hold. It was crammed full of bags,crates, packages, and mail. "Look, Shocky, or whatever-your-name-is, Idon't know what happened out there to your friend, but you captured thisgoddamn lunatic and now me and my partner gotta take him to the Chief. So whydon't we see if we can strike ourselves a little bargain here."Jakemoved gently past him into the cargo hold. He pulled a large box out of a sackand ripped it open. "It's coming on Christmas, Shocky. Why don't wecelebrate a couple weeks early?" Inside the large box was another boxwrapped with ribbons and gold paper. Jake tore it open and pulled out...ADustbuster.Heheld it up for the hunter, turning it in his hands. "Whaddya think,Shocky? Your wife, maybe? Tidy up the igloo real—"TheInuit swung his rifle, batting the Dustbuster, crashing it against the wall. Heanchored the gun on his shoulder and advanced toward Jake.Jakecrawled backward in terror, stumbling over the mounds of baggage and boxes."Wait a minute!" he cried desperately. "I’m sure we can worksomethin' out!"Thehunter aimed his gun.Jakegrabbed a stuffed duffel bag and hugged it to his chest. "Donny! Help!Somebody! Please!"Shakshinoticed something and relaxed his hold on the rifle."What...what is it?" Jake stammered.TheInuit was staring at the top of the duffel bag.Jakelooked at the opening. A small furry white tail was sticking out."What...this? This here?" Jake clawed open the bag. The Yakuutek'sface widened in amazement.Alitter of half a dozen snow-white fur balls spilled out onto Jake O’Donnell'slap. They couldn't have been more than a few weeks old.TheYakuutek stared at them, his mouth agape. This proud hunter from the ArcticCircle had apparently never laid eyes on a cat.Jakeheld one out in his trembling hands. "You like the kitty, Shocky? She’sone o’ Lily's litter. Lily is Frank Dieter’s cat. We were taking 'em back tothe pound in Fairbanks."TheYakuutek hunter set down his rifle. He took the tiny creature into his arms asif some great miracle of the Earth Mother had been handed him, a precious giftfrom the White Spirit of the North. A small smile crossed his face, a smile ofawe that Jake thought he'd probably not forget for a long, long time."Youall right in there, Jake?" he heard Donny shout."Yeah,"he called back.Hewatched the Inuit cradling the kitten. "What do you say, Shocky. Wannatrade the monster for the kitties?"

7. The snowman had no head.Threechildren, bundled in parkas and scarves and boots and gloves, were on theirknees rolling a ball of snow across the white-blanketed schoolyard. Theystumbled over each other like puppies, the sound of their laughter echoingsharply off the high brick wall of the schoolhouse.Kriscould hear them from the parking lot. She was sitting in the car with hermother, Linda Carlson, a 42-year old widow whose raven-black hair had alreadybegun to gray. Linda was talking to her, but Kris was no longer listening toher words. Carried away by the echoing shrieks of the children, she had driftedoff to another time and place, far away in a distant corner of her memory,where her tiny brother Paul was searching for a carrot he'd dropped in thesnow.Graduallyshe became aware of her mother speaking her name."Yousee, honey, that's exactly what I'm talking about.""What?"said Kris irritably, turning from the window. She wore a stylish pair ofsunglasses that reminded Linda of pictures of her own mother from the 1950's."Nowdon't get defensive. You weren't listening, that's all.""Iwas listening.""Youwere a million miles away.""No,I wasn't," Kris mumbled. In her mind she saw Paul gleefully holding up hiscarrot."I'mnot going to argue," said her mother. "We've already decided aboutthis.""Youdecided about it.""Youhad your say. I listened. I determined that you're just giving up. I won't letyou do that.""Mom,I'm eighteen years old. I can make my own decisions. I always have to do ityour way.""That'snot true. You didn't want a dog. Did I force you to get a dog?""Idon't like dogs," Kris said emphatically. "And they don't likeme.""Honey...the Burton's Shepherd didn't know you, that's all."Krisrubbed her hand nervously. "I don't want to depend on an animal likethat."Lindalooked at her daughter. She reached out, took one of her hands tenderly in herown. "It's okay to admit you're afraid of dogs. There's nothing wrong withbeing afraid." She continued to hold her daughter's hand, gently caressingit. "Don’t you think that might be what's happening here, too?"Krispulled away. "Spare me the psychotherapy, Mom.""Youloved the cross-country. What's so different about this?""What'swrong is that this is what you want. You couldn't care less about what Iwant. You're treating me like a child.""Well,maybe if you didn't act like such a..." She stopped herself. "Somedayyou'll thank me, Krissy.""Right,Mom. So original."Lindasighed. She yanked on the door handle and climbed gruffly out of the car. Krisheard her walk to the trunk. She's probably forgotten something, Kris thought.She's always forgetting something. She didn't used to be like that..."Kris,where's your bag?" She was rifling through the messy trunk."Iput it out, Mom. Did you take it?""Ithought I told you—. Oh. Here it is."Lindaslammed the trunk shut, walked around and opened Kris's door."Giveme your hand."Fora long moment, Kris didn't budge. Then she suddenly remembered something, thereason she'd finally agreed to come here at all. She reached for her whitecane, took her mother's hand, and climbed carefully out of the car."Mom?"she asked as her mother shut the door. "Do you see a Beetle in thelot?"Hermother looked at her, puzzled. "A beetle?""Yeah,you know, the car, the old Volkswagen Bug.""Oh,uh..." She scanned the parking lot. Next to the schoolyard, where thechildren were jamming a stick nose into the snowman's eyeless head, she spotteda rusty, mustard VW Bug."Yes,over there, there's a yellow one in the corner."Kris'sheart skipped a beat."Why?"her mother asked. "Whose is it?""Oh...nobody," said Kris. Her mother eyed her inquisitively as they headed intothe school.

8. "I wish you'd sit down andrelax." Andrea Parks had been watching Linda pace the floor since she'dcome into her office."I'mfine," said Linda."Youdon't look fine. You look worried."Lindastopped walking and turned to her friend. Andrea, as always, looked cool,casually elegant, and efficient. She wore a short white blazer, a fitted skirt,and a pale blue silk scarf beneath her short blonde hair. Sitting, legscrossed, on the edge of her desk, she looked like a woman in complete controlof her life.Lindahad felt that way, once. She wanted to feel that way again."What?"asked Andrea. "What is it?"Lindashook her head. After a moment she started to speak, but was interrupted by thering of the telephone.Andreareached across her desk. "Director Parks. Oh, hi George." She raisedher finger and nodded to Linda, indicating the call would be short.Lindaturned to the window that overlooked the training room. A fifty-foot-longsimulated ski slope dominated the enormous room. Slick white carpet covered theslope, with a handrail along one edge and safety nets mounted under each side.Two blind children, not more than ten years old, were clinging to the railinghalfway down the slope, their skis splayed out awkwardly beneath them.Atthe bottom, loudly coaxing them on, stood a compact, muscular African-Americanwoman with extremely short-cropped hair, wearing Spandex and bright redhigh-top basketball shoes. Linda had seen the woman before at the school.Andrea had said she was a veteran of Iraq. She was surrounded now by half adozen children of various ages, all in skis, flopping about like penguins whilewaiting their turn on the hill. Linda could not find Kris among them, andwondered if she was still in the waiting room.TheBlind Learning Center was the only one of its kind in the entire state ofAlaska. The school was widely renowned for the range of its programs and thequality of its well-trained staff. Many of the students' families had moved toFairbanks from other parts of the state so their children could regularlyattend.Lindaand her daughter lived in the town of Healy, at the northeast corner of DenaliNational Park. Fairbanks was only 70 miles away, an easy drive up Highway 3along the frozen banks of the Nenana River. Linda had made the drive a thousandtimes. She was a part-time social worker carrying a case load at a communitymental health clinic in the city. A year after Kris lost her sight in theaccident, she'd begun taking her along on the commute, leaving her forcross-country lessons at the school while she went to work at her job in town.It had been good for Kris, she'd thought. It had helped her to forget."Well,at least you've stopped pacing."Lindaturned.Andreawas hanging up the phone. "Won't you please sit down?" she said.Lindashrugged. She took a seat on a Wassily chair beneath a framed poster of a sandbeach rimmed with palm trees."Iwant you to stop worrying," Andrea insisted. "Kris had a great timecross-country skiing with us.""Shedid," said Andrea. "But lately she's been... I don't know — pullingback again. She won't take even the slightest risk. It's like she's lost allher self-confidence.""Youknow that's not the least bit unusual at this stage. It takes years—""It'sbeen four years since the accident, Andrea. She's stopped making any progress.She sits around moping, feeling sorry for herself. I can't seem to do anythingright. I'm walking on eggshells."Lindastood again and walked to the window. She watched the kids on their skis,tacking their way down the make-believe hill. "You didn't know herbefore," she said thoughtfully. "She was so... exuberant. So full oflife. Just like her dad."Andrealeft her desk and walked over to stand by her friend. They'd known each otherfor three years now and the two women had grown close. "I'm sorry,Linda," she said. "I know how you feel. But it takes time. Youknow that better than anyone."

Copyright © 2012 by Michael AbbadonAll rights reserved.

September 16, 2024

Story Merchant E-Book Deal: Michael Abbadon's Thriller Snowblind!

Snowblind by Michael Abbadon

Available on Amazon

She skis sightless, a monster at her heels!

Eighteen-year-old Kris Carlson needs a second chance. Blinded years before in a freak accident, Kris is trying to restart her life by learning how to ski again—without eyesight. A new audible-radar technology makes this miracle possible.

When the initial trials prove promising, Kris heads off to the mountains for a weekend of skiing with the ski school director and her daughter. But the three women encounter a fierce winter storm and are forced to take refuge in a trapper’s cabin.

Kris soon discovers the trapper’s mauled corpse. It seems a plane has gone down in the storm, and there’s some kind of monstrous beast on the loose.

September 13, 2024

Join Rudy Yuly and Empire Way at Machine House, Sept. 21, 2024

Come have a listen at the family-friendly Machine House Brewery in Hillman City.

Adults, kids and pets welcome! Hope tosee you there!

Sept. 21, 7-9 PM

No cover, tips welcome

Machine House Brewery

5718 Rainier Ave SSeattle

September 11, 2024

“Art Informs Life and Life Informs Art”: Dennis Palumbo on Art, Life, and Psychotherapy – Part II

SECOND THOUGHTS

By Vincenzo Di Nicola, MPhil, MD, PhD, FCAHS, DLFAPA, DFCPA

Dennis Palumbo, MA, MFT

Introducing Dennis Palumbo – Psychotherapist and Writer

It is a pleasure to introduce Dennis Palumbo, MA, MFT, to the readers of Psychiatric Times. Dennis is a licensed psychotherapist in Los Angeles, CA, where he specializes in treating individuals in the creative arts community of Hollywood. He is uniquely well-suited for this specialized work given his double, even triple, skill sets as a former Hollywood scriptwriter and current detective fiction novelist,1 teacher of creative writing,2 and his work with Robert Stolorow, MD, incorporating intersubjectivity theory in his psychotherapeutic work. Dennis will soon be addressing readers of Psychiatric Times in a monthly column of his own, “Creative Minds: Psychotherapeutic Approaches and Insights.” His latest essay is about his role as Consulting Producer on the recent Hulu TV series, “The Patient.”3

We have had an enriching exchange about art, life, and psychotherapy for several years. Dennis was our invited guest for the inaugural meeting of American Psychiatric Association Caucus on Medical Humanities in Psychiatry in New Orleans, LA, in 2022. Dennis’ uniquely diverse and specialized skill sets allow me to explore the question of the relationship between the psy disciplines and detective fiction. More generally, I wanted to explore the roots of creativity and empathy in creative writing and clinical work and connect it to therapy.

Di Nicola: A friend of mine, Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker, PhD, was asked by Stephen Colbert on his show to describe cognitive neuroscience in 5 words. Without skipping a beat, Steve said, “Brain cells fire in patterns.” That echoed our teacher Don Hebb’s discovery of “cell assemblies” at McGill University. As a social psychiatrist and philosopher, my answer would be that “Meaning emerges in social context.” What would your 5 words be? Either about writing or about therapy?

Palumbo: For writing: “Communicating inner worlds in narrative.”

For therapy: “Therapy explores subjectivity in context.”

Di Nicola: We grew up on opposite sides of the US-Canada border in steel towns with large immigrant working class populations. I am a first-generation Italian immigrant who grew up in Hamilton, ON, while you are a third generation Italian-American from Pittsburgh, PA. What does your Italian heritage mean to you generally and as a writer and therapist?

Palumbo: I take great pride in being an Italian-American. Growing up in Pittsburgh, I learned a lot about the Italian craftsmen, painters, and contractors who built much of the city. I think I have inherited the Italian love of good food, pride in hard work, and talking with your hands! I also value our long legacy as visual artists and performers.

As a therapist, I think my background as a child of Italian-American blue-collar workers informs, consciously or not, my prejudice in favor of hard work, consistency, and passionate emotions. Not that I trumpet these values in session with patients, but I must admit that I am drawn to patients who exhibit them.

I also relate to struggle itself, having grown up hearing of my grandparents’ struggles against ethnic stereotyping and all-out discrimination. So the career struggles of my creative patients, especially in such brutal marketplaces as Hollywood and publishing, affect me deeply, and supporting them comes naturally.

I can only think of 1 or 2 clinical colleagues who share my Italian-American heritage, both of whom take their work seriously and passionately. The rest of my colleagues are primarily Jewish, though one Gentile has snuck in.

In my Hollywood career, most of my fellow writers and producers were Jewish. There are a good number of Italian-American creatives in the entertainment industry, but most felt the need to anglicize their names (best-known example is David Chase—originally DeCesare—creator of “The Sopranos”). This was particularly true for performers, like Tony Bennett (Antonio Dominick Benedetto), Pat Cooper (Pasquale Vito Caputo), and Dean Martin (Dino Paul Crocetti).

As a writer, particularly in my fiction, my Italian-American heritage is front-and-center. The protagonist of my Daniel Rinaldi mystery series is a proud Italian-American, and this aspect of his character, background, and opinions is highlighted throughout the books. (In one of the books, reference is made to a very reticent public figure with a rock-ribbed Republican background. As described to Rinaldi by an acquaintance: “He’s a WASP, Danny. All he cares about is Scotch and quiet.”) Which reveals some prejudice on my part!

Other Italian-American characters show up throughout the series, as well as in some of my short stories. Sometimes, their being Italian-American is an important aspect of their characterization; sometimes it is just incidental.

Di Nicola: Psychiatry and the Cinema explores film from the dual perspectives of the Gabbard brothers: Krin, who teaches comparative literature, and Glenn, who is a well-known psychotherapist.4 What are the implications of transferring insights from the page to the screen for you as an author?

Palumbo: Since the beginning of my writing career, prose and screenwriting have been intertwined. I started writing short stories while still in high school and received some very nice rejection notes from many of our finest magazines. I continued writing stories when I arrived in Los Angeles to try to break into TV and film writing. Interestingly enough, the same week my then-writing partner and I were hired as staff writers on the ABC sitcom, “Welcome Back, Kotter,” I sold my first mystery short story to Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. And it was while I worked on that popular sitcom that I sold my first novel, a science fiction thriller called City Wars, to Bantam Books. Throughout my Hollywood career I continued to write Op-Eds, reviews, essays, and short stories.

I would say the biggest takeaway from my scriptwriting experiences, both in TV and film, was a sharpening of my skill at dialogue, which I feel enhances my fiction immensely. Writing for Hollywood also teaches you to “cut to the chase”—as they say in the entertainment business—in that your work in prose becomes more streamlined, less flabby and overwritten. On the other hand, sometimes when adapting a prose work—a novel or short story—for the screen, it is actually better to expand on a scene (or even a sentence) in the work to maximize its dramatic effect. For example, I was once hired to write a screenplay based on a novella by Jim Harrison. At one point in the narrative, the main character goes to a bordello where, as Harrison wrote, “it cost him $300 not to get a hard-on.” A vivid, explanatory sentence, and another rueful reminder of the character’s mid-life crisis. In my script adaptation, that 1 line became the basis for a 3-page scene. It was an event in his life that, while perfectly described as an ironic single sentence in the novella, needed to be dramatized to work onscreen.

In transferring material from the page to the screen, as in much in life, there is no “one-size-fits-all” model. Which, by the way, is exactly how I feel about psychotherapeutic treatment.

Di Nicola: David Gilmour was a delightful film critic for CBC television. When his 16-year-old son Jesse dropped out of school for a year, his father made a deal with him: he had to watch 3 films a week of his father’s choosing. His charming memoir, The Film Club,5 tells the story of that year and what happened to their father-son relationship. What are the implications of transferring insights from the arts (novels, screen) to “real life” and to therapy?

Palumbo: When it comes to this question, the usual answer is that art informs life and life informs art. The latter position is much more easily grasped: things happen to people in life (marriage, divorce, childbirth, job loss, chronic illness, etc) and artists transform these experiences into either a narrative, musical, plastic or visual form. Books, plays, films, TV series, poems, musicals, etc, derive their expressive power by reflecting or transforming or questioning or validating the assumptions associated with the whole range of the human experience. So that part is easy to understand; ie, the phrase “art imitates life.”

Where it gets interesting is when we consider how readily and powerfully the arts inform life. To take a cliched example, after the hundreds of romantic stories produced by Hollywood over the past 100 years, couples have some particular ideas of what their relationship “should” be like. Certainly they are aware that whatever is going on their relationship, it surely does not seem or feel like what has been seen by them onscreen. Case in point: years ago, there was a popular TV series called “Hart to Hart,” in which Robert Wagner and Stefanie Powers played a rich, beautiful, breezily-romantic couple who solved crimes (of course they did). While the series was on the air, the wife in a couple I was seeing explained that her goal for therapy was: “To be like the couple on ‘Hart to Hart’.” Of course, a nearly impossible model to emulate.

None of us are immune. When I was a kid, reading about the witty writers dining regularly at the Algonquin table, I just assumed that when I grew up and became a famous writer, that was how I would spend my evenings: breaking bread and drinking cocktails with smart, sardonic, and well-dressed fellow celebrities. Despite my screenwriting success, the sobering fact that working in Hollywood was not actually like that was pretty dispiriting.

Di Nicola: No, we are not immune, Dennis. The Italian film, Cinema Paradiso by Giuseppe Tornatore, tells the poignant story of Totò, a boy without a father, and Alfredo, a gruff childless film projector who befriends him in their Sicilian town. There are hilarious scenes where the young boy sneaks a peak at the town priest censoring the love scenes from the movies that Alfredo cuts out. Years later, when Totò has become a filmmaker in Rome, he finally returns home for Alfredo’s funeral who has left him a special legacy: a reel of all the “outtakes” from the films of his childhood and youth, representing the love that is absent from his life. When I met my father for the first time in Brazil as an adult, many images and metaphors flooded my imagination but none captured my experience better than those “outtakes” as a concrete metaphor for the missing pieces of my life.6,7

Palumbo: Our models for sexual attraction, courage, success, popularity, and even parenting are being portrayed constantly now online, as well as on film and television, plays and musicals, books and graphic novels. And often these artistic representations of “real life” are so impactful that some people are stirred emotionally more by portrayals they see than by events in their own lives.I had a patient recently who detailed all the effort he was putting into a Valentine’s Day dinner with his girlfriend. “Nowadays,” he told me, “it’s all about the optics.”

Isn’t everything nowadays? Even politics is frequently described as “show business for ugly people.” The implication being that it is all show business.

So what does that mean for therapy? Not only does the clinician have to explore and untangle a patient’s early childhood, the familial dynamics and patterns, but to see this in the context of a media/image-drenched culture in which the patient is embedded. A culture that gives birth to assumptions, prejudices, prescribed desires, and shifting personality models. This means the clinician has to have a significant familiarity with these cultural touchstones and explore their meanings—for him- or herself as well as with the patient.

Just as the arts can provide us with insights into our own issues and concerns, and why certain films or books or poems can “change one’s life,” good therapeutic treatment enjoins with the patient to see what patterns (or narrative, if you like) underlie his or her particular engagement with life. Which means drawing as much from everything the patient has seen, read and listened to as from the real-life events in his or her experience.

Di Nicola: How do you think philosophy informs your work and how does your work reciprocally affect your philosophy?

Palumbo: Good question. I will try to keep my answers short, though it deserves a longer one.

There are certain philosophical books (for example, William Barrett’s The Illusion of Technique and Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus) that have had a profound impact on my theoretical thinking in terms of my work with patients. Though I have a pretty good grounding in both Gestalt and intersubjectivity theory as guidelines in my work, I have moved away from adherence to any concrete orthodoxy. As a therapist, I do not subscribe to the “one-size-fits-all” model of clinical treatment, and this allows me a certain freedom of approach in my work with patients.

At the same time, my clinical work over these 30 years has informed and given perspective to any philosophical ideas that I too easily embraced. Simply put, my patients and their issues, beliefs, and unique histories are a continual source of surprise and wonder to me. As St. John of the Cross put it (though in a markedly different context), “I came into the Unknown, beyond all science.”

I must admit, I respond more favorably to philosophical writers whose literary skill predominates (Camus, Schopenhauer, de Beauvoir, some Nietzsche) or else whose intellectual reach excites me (Kant, Wittgenstein, Spinoza), whether I agree with them or not. But I do find that these categories of thought provide an intellectual base for my clinical thinking, whereas most conventional “personality theories” tend to restrict it.

Di Nicola: In the middle of the 20th century, Hollywood experienced an entertainment industry blacklist as part of a moral panic called the “Red Scare.”8 Does the Hollywood blacklist have any relevance today?

Palumbo: It has no relevance as such today, though its spirit lives on in “cancel culture.” Both are examples of Hollywood’s timidity and unwillingness to buck social/authoritative forces in fear of diminished profits. I feel similarly about the old Hays office and its code for movies.

These kinds of investigations or codes, whether originating in Congress or self-generated by the industries involved, speak to the single goal of profits, which in turn is based on getting the greatest number of viewers, which really means offending the least number of viewers. To do that, content providers (today’s term, which I loathe) need to conform to and in fact reinforce the conventional beliefs of the audience. Which was the genesis of the Hays Office and its crusade against overt sexuality (straight or gay), substance use (except alcohol, which was permitted as comedy), satiric views of religion, or any plot that hinted at a crime going unpunished. The blacklist occurred as a result of an anti-Communist paranoia, famously spearheaded by Joseph McCarthy. Today’s cancel culture, derived initially from the (long overdue!) #MeToo Movement, has now become merely another way for commercial content providers to insulate themselves from criticism (much of it warranted) that they are insensitive to the experiences of non-white, non-male, and non-straight individuals.

As the culture changes and the pendulum of what is acceptable swings back and forth, it is important for the artist to stay true to his/her creative vision. Certainly, no easy task in a brutal, demanding, and still quite conventional marketplace. For the therapist, often justly accused of being an agent of the dominant culture, it is important to stay attuned to the subjective experience of the patient, in the lived context of the patient’s world.

Di Nicola: How do you feel as a psychotherapist about the level of violence in the culture generally and more specifically in the portrayals of the entertainment industry in which you have been intimately involved in various roles?

Palumbo: That is a complicated question, as most of yours are! It deserves more space than an interview allows. Caveat aside, I have strong feelings about gun violence in the US and think our inadequate gun laws lead to more domestic shootings, road rage events, and gunfire outbreaks in public places like bars or parties. As a psychotherapist, I have seen how the level of violence has increased an overall unease in some patients. In addition, the rise of anti-Semitism and anti-Muslim violence has been particularly disturbing, both to me and to my patients.

Yet, while the level of violence is unacceptable, its depiction on the news and social media has an effect on consumers that is somewhat unwarranted. History shows us that violence has been an aspect of our lives as a species and as nations since time began, so it is probably untrue that the level it is at now is somehow unique. As Neil Postman pointed out, in the past, before world-wide communication, “bad news” was learning that your neighbor’s farm had burned down, and so you and everybody else in town could go help rebuild it. Nowadays, with global communication’s unprecedented reach, we learn of wars, famines, and violent revolutions occurring all over the world, about which we can do very little. This adds to our feeling that “things are getting worse,” and yet this may or may not be empirically true. So addressing my patients’ concerns about how dangerous and violent the world seems has become more and more front-and-center in our clinical work. Especially when it affirms old childhood messages about the patient's vulnerability about external events, how treacherous and dangerous others can be, how incompatible ethnic and religious differences are.

The second part of your question is more problematic. For one thing, I am the author of a series of psychological thrillers which often depict implied or even graphic violence in some scenes. My defense of this aspect of my novels is that these scenes lend authenticity and suspense to the narrative, and are to be expected in the genre. I must admit, too, that I derive a reasonable catharsis from writing these types of stories. My joke is that it is better for my violent urges to be on the page than out in the real world! Parenthetically, most research on the effect of violence in entertainment (primarily visual representations on film and television) is contradictory. There are certainly isolated incidents of a particular violent act depicted in a film replicated in real life by someone who claims to have been inspired by what they saw onscreen, but these are outlier events. Violence in drama has been a staple of narrative since the Greeks, if not before. From Oedipus and Medea to Punch and Judy, from Shakespeare to pulp magazines, violence and popular narrative have been hand-in-hand.

Moreover, in my practice, I treat writers, directors and actors who routinely work in genres whose narratives are often quite violent. My sense is that, since most artists understand that drama demands conflict, and that violence in some cases is both appropriate and expected (based on the genre), the use of it is merely grist for the mill. Though in my own case, I will never forget being a guest on a PBS interview show after the release of my fifth Daniel Rinaldi novel, Head Wounds, which featured several pretty harrowing scenes. The first question the host asked was, “Dennis, are you all right?”

Stillness, Quietude, Equanimity

One of the chapters of Dennis’ book on writing quotes Saul Bellow, a Nobel prize-winning writer born here in Montreal, who said that writing possesses a “stillness that characterizes prayer.”2 In that chapter, Dennis recommends quietude: “A hushed, private space, to which a writer is granted access by the act of writing itself.” It brings to mind a quality that another Canadian, the great physician William Osler, MD called aequanimitas—equanimity. Stillness, quietude, equanimity.

And let me add one last word. I have always been inspired by the first word I learned in ancient Greek, σωφροσύνη, sophrosyne—“soundness of mind,” which I interpret as a judicious balance. Dennis Palumbo has that, in spades.

Resources

For a superb, reassuring and therapeutic guide to writing, consult Dennis Palumbo’s Writing from the Inside Out. John Wiley & Sons; 2000.For his latest Daniel Rinaldi thriller, read Deniss Palumbo’s Panic Attack. Poisoned Pen Press; 2021.Dr Di Nicola is a child psychiatrist, family psychotherapist, and philosopher in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, where he is professor of psychiatry & addiction medicine at the University of Montreal and President of the World Association of Social Psychiatry (WASP). He has been recognized with numerous national and international awards, honorary professorships, and fellowships, and was recently elected a Fellow of the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences and given the Distinguished Service Award of the American Psychiatric Association. Dr Di Nicola’s work straddles psychiatry and psychotherapy on one side and philosophy and poetry on the other. Dr Di Nicola’s writing includes: A Stranger in the Family: Culture, Families and Therapy (WW Norton, 1997), Letters to a Young Therapist (Atropos Press, 2011, winner of a prize from the Quebec Psychiatric Association), and Psychiatry in Crisis: At the Crossroads of Social Sciences, the Humanities, and Neuroscience (with D. Stoyanov; Springer Nature, 2021); and, in the arts, his “Slow Thought Manifesto” (Aeon Magazine, 2018) and Two Kinds of People: Poems from Mile End (Delere Press, 2023, nominated for The Pushcart Prize).

Dennis Palumbo is a licensed psychotherapist in private practice, specializing in working with creative patients. His award-winning series of mystery thrillers—the latest is Panic Attack—feature psychologist and trauma expert Daniel Rinaldi. He is also the author of Writing From the Inside Out, as well as a collection of mystery short stories, From Crime to Crime. Recently, he served as Consulting Producer on the Hulu limited series “The Patient.” Formerly a Hollywood screenwriter, Palumbo’s credits include the feature film “My Favorite Year,” for which he was nominated for a Writers Guild Award for Best Screenplay. He was also a writer for the ABC-TV series “Welcome Back, Kotter,” among numerous other series. His short fiction has appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, The Strand, Mystery Weekly, and elsewhere. His work helping writers has been profiled in The New York Times, Premiere Magazine, GQ, The Los Angeles Times and other publications, as well as on NPR and CNN.

September 10, 2024

You can LISTEN to Leo Daughtry's Talmadge Farm on Audible!

It's 1957, and tobacco is king. Wealthy landowner Gordon Talmadge enjoys the lavish lifestyle he inherited but doesn't like getting his hands dirty; he leaves that to the two sharecroppers - one white, one Black - who farm his tobacco but have bigger dreams for their own children. While Gordon takes no interest in the lives of his tenant farmers, a brutal attack between his son and the sharecropper children sets off a chain of events that leaves no one unscathed.