Kristen Lamb's Blog, page 11

November 6, 2020

Holding Out for a Hero: Tips for Building a Protagonist Readers Will LOVE

Humans are a story people, meaning we all share one thing in common—we LOVE a great hero. Yet, crafting a hero isn’t as simple as one might think. In fact, new writers generally serve up a ‘hero’ too soon. They fail to understand that the title—HERO—is something that must be earned.

In fact, the harder it is for our main character to attain this noble title, the more valuable it is. The greater the opposition (externally and internally), the sweeter the prize.

To be blunt? Story participation trophies are about as exciting as real-world participation trophies.

A Hero is the FINAL Product

Before we get to any tips, let’s first make one thing clear. The hero is the final product forged in the fires of adversity. This might seem obvious to everyone who hasn’t tried to write a novel. When you’re new, though? You’re insecure.

Hey, I’ve been there.

I thought my main character had to be perfect for readers to like/want to root for her. Adding any flaws made me nervous.

I know! Give her ninja skills, too!

Frequently, new writers want their MC to be everything amazing. He/She has the looks and the moves. They’re larger than life and super *add in whatever superlative here*.

Yet, when it comes to great stories, this is a formula for a snooze fest. A hero, by definition, must overcome something to be worthy of the appellation. The story, then, is the account of the overcoming.

When we start the story, we begin with a rough protagonist, riddled with flaws who then crosses paths with the antagonist’s agenda. Once the protagonist makes a conscious decision to step out of his/her comfort zone and agree to the journey, the transformation process begins.

Rough Flawed MC–>Evolving Protagonist–>Hero

As we go through these tips, keep in mind that genre will heavily dictate each of these factors.

#1 Give Your MC (Hero) Weaknesses

One of the reasons we want to give our MC some weaknesses is that no one is perfect. We (readers) can’t relate to perfect people. While it is scary to admit our protagonist is flawed, flaws are what will help readers connect and the story resonate.

Fear of failure, lack of confidence, lack of experience, gullibility, overconfidence, fear of abandonment, trust issues, insecurity, addiction, etc. are all very human weaknesses we can exploit for maximum tension.

Once we flesh out a protagonist and his or her weaknesses, we’ll have a better idea how this character will need to grow. The ideal story problem won’t have the MC operating in her strengths, rather it will have hit her right in her soft spots.

This will give only two options: change and grow stronger or collect allies to buttress areas of weakness.

Today, I’ll try to use two very different genres as well as examples I’ve not used before. No Lord of the Rings, today.

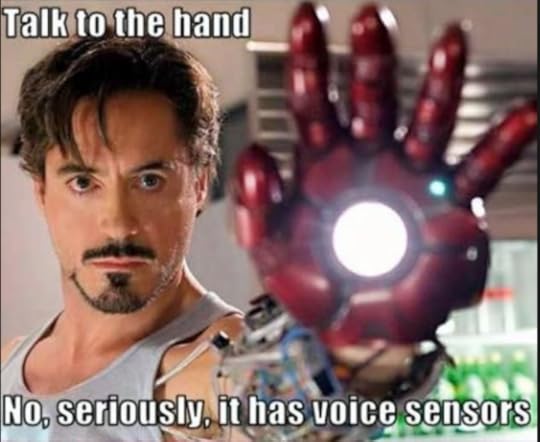

Stranger Things : Even Superheroes are Weak

For instance, in the popular series Stranger Things, the MC, Eleven, escapes a secret government facility that’s been using her to spy on the Soviets as part of black bag operations. She has strengths (mental powers), but these powers are majorly hindered due to the fact that she’s never lived out in the real world.

Her naivete makes her extremely vulnerable to recapture. Until she can learn how to function outside of a lab, she’ll have to learn to trust her new allies (and trust is NOT her strong suit either).

Though Eleven has crazy mind powers, we can relate to her because her weaknesses make her more like us.

…unless you have mind powers. Then look me up because we totally should be friends.

Isn’t It Romantic? Everyone Wants Love

Since not everyone is a science fiction buff, I’ll use another example from a light comedy I absolutely LOVED. In the movie Isn’t It Romantic, Natalie, a woman disenchanted with love, suddenly finds herself trapped in a romantic comedy.

The main character (played by Rebel Wilson) is not the kind of gal normally cast as the heroine of romantic comedies…which is much of the point of the movie. She’s overweight, insecure, and lets her colleagues run roughshod over her.

Because of her low self-esteem, she fails to demand the credit she’s due as a talented NY architect and, instead, tolerates terrible treatment (like when a major client sends her out for coffee when she’s the project manager not the coffee gopher).

Though Natalie has clear surface weaknesses—her weight, lack of fashion sense—she has some internal weaknesses as well. She’s bitter, doesn’t believe in love, is very judgmental, and automatically seems to assume the worst.

Don’t know about y’all, but I can relate to a lot of this, especially the part about being a doormat. One phrase: GROUP PROJECT.

Enough said.

#2 Give Your MC (Hero) Wounds

We don’t have to live very long in this crazy messed-up world before we get sucker-punched. Ideally, our MC will have a ‘life’ before the beginning of our story (backstory).

Genre will dictate what kind of wounds and the level of damage, but my point here is that pain is pivotal for any good story. Perfectly adjusted people make for lousy fiction (provided such people even exist).

All of us have been hurt and, when put under pressure, these are the weak seams most likely to burst.

Hero Wounds Don’t Have to Be Weird

Using my first example above, Stranger Things, Eleven has suffered serious trauma. She was torn away from her biological mother at an early age then imprisoned in a secret government facility. Her short life has been nothing but a series of terrifying and morally repugnant experiments.

The government has also harnessed her powers and forced her to do a lot of very bad things, leaving her with crushing guilt.

Remember, Eleven already had trust issues before she escaped. She won’t last in the outside world all on her own. But, her false guilt and abandonment issues only fuel her fear of trusting anyone.

Additionally, Eleven believes she’s poison because life has taught her that life is nasty, brutish and short for those who get too close to her.

The problem, however, is if she fails to trust, she has no hope of survival, let alone living long enough to be a hero. Though most of us, I assume, don’t have amazing psychic powers, we can at least understand what it’s like to be betrayed and how hard that can be to overcome.

We might also feel false shame or guilt over events that weren’t even our fault.

So, hopefully, y’all can see that even though Stranger Things involves some seriously extraordinary elements, the connective points that resonate with the audience (us) often are actually very common.

Hero Wounds We Can All Relate To

Going back to Isn’t It Romantic, there are so many scenes in this movie that resonated with me. Early in the movie, young Natalie is watching Pretty Woman. She’s obviously enraptured in the story when Mom bursts her bubble:

“They’ll never make a movie about girls like us, and you know why? Because it would be so sad that they’d have to sprinkle Prozac on the popcorn or people would kill themselves.“

Once we see this critical moment in Natalie’s past, it becomes pretty obvious why she’s grown into a jaded and lonely adult. She believes love (respect) is only for the perfect women in ads, magazines and in the movies. Her mom’s crappy comment left a deep wound that never healed.

Because of this wound, she acts out in ways that reaffirm this untruth. She pushes people away, doesn’t recognize those who really do care for her and value her, and she fails to see love that’s right in front of her face.

This is all because deep down, she doesn’t believe she is worthy of love.

#3 Give Your MC (Hero) a Blind Spot

The blind spot is directly related to the MC’s weaknesses and wounds. We meet our MC in normal world, and, without any opposition, it’s tough to see weaknesses.

For instance, I have no idea if my arms are weak until I try to pick up that fifty pound bag of dog food and suddenly find that I can’t. So long as my husband always carries in the dog food, I might keep on believing my upper body strength is just fine. Only when my strength is tested will I be able to see I’m somehow lacking.

The same is true for wounds. Maybe I believe I am a super-confident person because I’m always in charge and get things DONE. But, when faced with a challenge too big for me to handle alone, circumstances will force me to face the fact I’m not confident at all, rather I’m an insecure control freak.

This is the point of the story problem. It reveals weaknesses and wounds that LOOOVE to hide in the blind spot.

Protagonists with no weaknesses and who are fully self-actualized are boring. It takes a hero to face the darkness, especially the darkness lurking inside.

Another tricky thing about blind spots is they tend to offer false confidence because they often masquerade as strengths.

Superhero Blind Spots

Eleven escapes the government facility and, over time, forges friendships and allies (though not easily). Why? Because if Day One she showed them her powers and detailed the government experiments, it would have been a pretty boring story.

Too much too soon.

Withholding information creates tension that keeps audiences riveted. What better way to do this than have an MC with serious trust issues?

Eleven’s justifiable paranoia keeps her withholding critical information. But, it isn’t just her trust issues that keep her from spilling the tea.

She actually cares about the first real friends she’s ever made and doesn’t want any harm to come to them. Yet, in her misguided desire to protect them, she ironically places them in much more danger.

In ways, she’s overconfident that her abilities can be enough to keep them safe. Even if that isn’t true, she underestimates their abilities in comparison to her own. Her underestimation of the collective power of her team is what steadily draws them all deeper into danger and steady raises the stakes from Eleven simply remaining free to her placing their entire plane of existence is in danger.

Until Eleven becomes aware of her blind spot, she has no chance of being a hero.

Holding Out for a Hero

I really loved the movie Isn’t It Romantic because it did a really great job of teasing the audience along what we believed would be a predictable rom-com ending. The only difference would be the overweight acerbic architect would find true love as opposed to the rom-com cookie-cutter prototype we all expect.

If you haven’t seen the movie, I highly recommend it. It’s just a fun, good time.

When Natalie (through an odd twist of events) finds herself thrust into a world where everything is a rom-com, it forces her to face who she is and why she believes what she believes.

As is true with the blind spot, Natalie soon starts noticing how she’s part of her own problem. Others walk all over her because she allows it, then goes off and complains instead of changing her behaviors. If she acted like a top end architect, the odds would improve that others would treat her as one.

She also realizes the biggest blind spot of all—WHY she’s so bitter when it comes to romantic movies (and how this is spilling into real life).

Natalie’s journey isn’t as much about a new wardrobe or makeover as it is about remembering the core pain and finally recognizing that it never healed. She never found love because she didn’t see it even when it was right next to her.

This is when Natalie becomes the hero in her own story. She can’t give to others what she doesn’t even have for herself…LOVE.

Build-A-Hero

After all of this, can you look at your main character and give them some relatable flaws? A protagonist with a secret, struggling with an addiction, has a hard time trusting, doesn’t believe they are good enough/strong enough/talented enough to get the job done?

Maybe someone so damaged they’ve gone off course believing they’re doing the right thing, only to learn how misguided they’ve become?

Think of your favorite stories and what flaws made the protagonists into the most interesting heroes (I.e. Forrest Gump, Bones, Deadpool).

What about wounds? Would Monk have ever been Monk if his wife hadn’t died the way she did? If he didn’t carry the false guilt that propelled an obsessive need for control? His wound created the flaws that makes him an unparalleled investigator.

Let’s look at a great blind spot. Think of what created the immortalized version of Sarah Connor. Terminator was a good movie, but Terminator 2 is iconic. Why?

Because Sarah started out as an everyday waitress thrust into extraordinary events. In her single-minded mission to protect her son and the planet, she unwittingly transformed into the very thing she sought to destroy.

In the end, we all love to make our characters larger than life, cool and kick@$$ in every way. Don’t let me stop you. We still can!

Just keep in mind that layering a healthy dose of flaws, wounds and blindspots can elevate a story from meh to magical. Even all our favorite comic book heroes have issues, blindspots and drama.

What Are Your Thoughts? I LOVE Hearing From You!

Who are some of your favorite heroes and why? I think a lot depends on my mood. Stranger Things is a really cool series because, while Eleven has the spotlight, every character is a hero in his/her own way and I could write a month of blogs easily on all the different characters.

They did an excellent job of layering in flaws, weaknesses, blindspots, and then using those to arc the characters into fantastic and fully formed heroes!

In fact, I think a lot of the best writing is coming out of series these days so it’s tougher to give good examples from the movies without reaching back in time to examples I’ve used plenty of times before.

But chime in! Have one place on the internet that is a little bit fun, right? What’s your favorite movie? Favorite hero/heroine and why?

The post Holding Out for a Hero: Tips for Building a Protagonist Readers Will LOVE appeared first on Kristen Lamb.

October 30, 2020

Story Structure: Why Some Stories Fall Apart & Fail to Hook Readers

Story structure is a HUGE deal in all stories. The last couple of posts, I’ve mentioned memoirs and how they can utilize a variety of structures. This said, there are so many variegations for the memoir, that I just can’t do them all justice here.

Since I am at least sharp enough to know when to defer to people much smarter than me…AND because I am #1 at HUMBLE…

At the end of the post, I’ll give y’all some links to people who ARE memoir experts and can do a much better job explaining all the structural styles available.

This said, if you’ve read my last two posts The Quest: The Hero’s Journey Meets Memoir and Narrative Style: The Heart of Storytelling we didn’t ONLY talk about memoirs. Rather, we discussed where some fundamentals for writing great memoirs apply across the board to other types of storytelling.

Whether we’re writing a memoir, novel, short story, essay, or even screenplays…structure matters.

If we keep starting out with great ideas that ultimately end up haunting our hard drives unformed and unfinished?

Structure.

Or, maybe we finish books, but no one seems to want to read them. It could be the glut in the market. OR it could be that the core idea is GOLD, but the structure isn’t such that it fully reveals what our story has to offer.

There are many reasons our writing might be stalling, stumbling, fumbling or failing. Yet, in my 20 years editing? It’s almost always, always a problem with story structure.

Story Structure and FLOW

The first obstacle we authors face—when writing anything—is subtly embedding a strong enough hook. How can we at least get the readers’ attention when there is so much cool stuff on YouTube to watch?

Yet, even when we hook the reader, the next challenge (and possibly the toughest) is to coax them into a state that psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi referred to as “flow.”

In the Wired article Go With the Flow, Csikszentmihalyi defined flow as, “Being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved, and you’re using your skills to the utmost.”

Anyone who’s ever started a book, planning to simply read a few pages…only to end up still awake at three in the morning because we just NEEDED TO KNOW HOW IT ENDS!

That’s flow.

Flow is intentional and inherent in the design.

Fail to Plan, Plan to Fail

Structure, sadly, is probably one of the most overlooked topics even though it’s the most critical.

Why? Because structure is for the reader (even with memoirs). The further an author deviates from structure, the less likely the reader will be lulled into flow.

When structure is missing, incomplete, or flawed, the easier it is for readers to become confused, frustrated and finally give up. Structure isn’t simply for function, but for beauty as well (refer to jacked up Ikea fail above).

Sadly, too many emerging writers want to get to the ‘fun’ stuff (for them). Pretty prose, descriptions, characters, using new words are great imaginative play. Unfortunately, that’s all it is. Play.

Structure can be tough to wrap your mind around and, to be blunt, most pre-published writers don’t understand it. They rely on wordsmithery and hope they can bluff past readers with their glorious prose.

Yeah, no. Prose isn’t plot.

Great Stories: Back to the BASICS

Today we are going to go back to some story structure basics, before we ever worry about things like Aristotelian structure (non-linear structure), turning points, rising action, and darkest moments, etc.

Now before you guys get the vapors and think I’m boxing you into some rigid format that will ruin your creativity, nothing could be further from the truth.

Plot is about elements, those things that go into the mix of making a good story even better.

Structure is about timing—where in the mix those elements go.

When you read a novel that isn’t quite grabbing you, the reason is probably structure. Even though it may have good characters, snappy dialogue, and intriguing settings, the story isn’t unfolding in the optimum fashion. ~James Scott Bell from Plot and Structure.

Structure holds stories together and helps them make sense and flow in such a way so as to maximize the emotional impact by the end of the tale. When it comes to memoirs, structure directly relates to the TYPE of memoir we want to write (more on that later).

The Micro Scale of Story Structure

Same thing can be said for writers…

Same thing can be said for writers…We’re going to first ZOOM IN and place the novel under a literary electron microscope.

The most fundamental basics of a novel are cause and effect. Super basic. An entire novel can be broken down into cause-effect-cause-effect-cause-effect (yes, even literary works). All effects must have a cause and all causes eventually must have an effect (or a good explanation).

I know that in life random things happen and people die for no reason. While life often IS stranger than fiction, fiction ain’t life.

So if a character drops dead from a massive heart attack, that ‘seed’ needs to be planted ahead of time.

Villains don’t just have their heart explode because we need them to die so we can end our book. Our MC can’t suddenly discover a journal that EXPLAINS EVERYTHING in the middle of Act Two because we failed to properly plot an actual story and painted ourselves in a literary corner.

Even in memoir, there needs to be a sense of cause-effect-result or readers will struggle to not only follow along, but to “get” the point of what they’re reading.

Now, all these little causes and effects clump together to form the next two building blocks we’ll discuss—the scene & the sequel (per Jack Bickham’s Scene & Structure). Many times these will clump together to form your ‘chapters.’

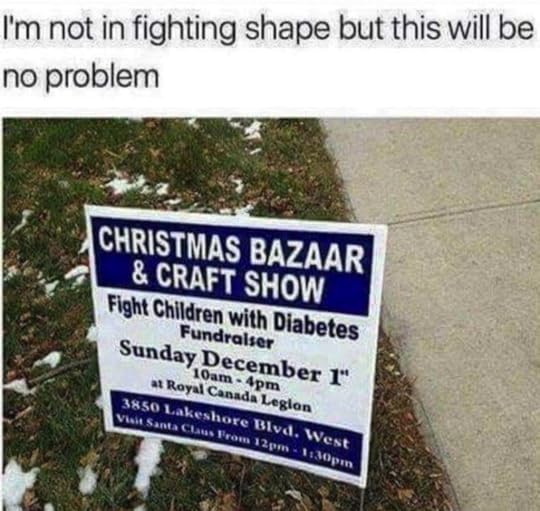

Order Matters: Scene & Sequel

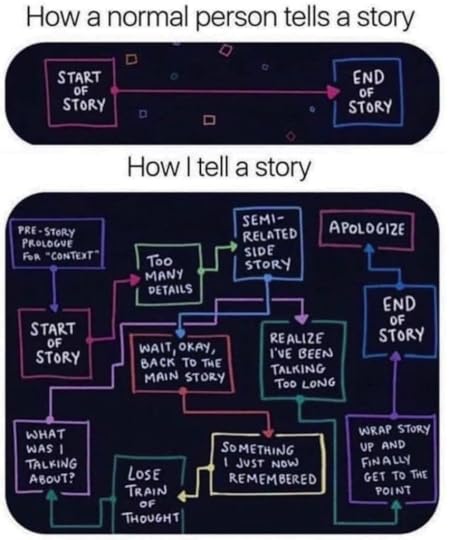

Word order matters, or we end up with confusion (refer to above image).

Structure’s two main components, as I said earlier, are the scene and the sequel.

The scene is a fundamental building block of fiction. It is physical. Something tangible is happening. The scene has three parts (again per Jack Bickham’s Scene & Structure, which I recommend every writer buy and read and study).

Statement of the goalIntroduction and development of conflictFailure of the character to reach his goal, a tactical disaster

Goal –> Conflict –> Disaster

The sequel is the other fundamental building block and is the emotional thread. The sequel often begins at the end of a scene when the viewpoint character has to process the unanticipated but logical disaster that happened at the end of your scene.

Emotion–> Thought–> Decision–> Action

Link scenes and sequels together and flesh over a narrative structure and you will have a novel readers will enjoy.

Oh but Kristen you are hedging me in to this formulaic writing and I want to be creative.

Understanding structure is not formulaic writing. It is a story delivery system that makes sense on a fundamental level.

Formulaic writing refers to the execution of story structure. It’s a reflection of skill, or rather, lack thereof. So relax, structure is your friend. It will make writing and finishing books easier, and it comes with the added bonus of not confusing the bejeezus out of the readers.

The Macro Scale of Story Structure

Yes, I know I began with the micro scale of stories. Why? Because I am being INTENTIONAL.

The macro scale (story structure) can take on a lot of different forms. With novels, we can use the tried-and-true Aristotelian three act structure, a four-act or five-act structure, parallel timeline structure, non-linear structure, looping timeline structure, etc., etc., etc.

The macro story structure we choose should be deliberate. For instance, most novels use traditional three-act structure. Beginning, middle, end. Bada bing, bada boom. Why?

Because it is what most readers are familiar with and it’s the easiest to read and also the easiest to write well.

Non-linear structure uses the flow of time as a literary device. It IS a cogent and deliberate design. What it IS NOT? A crap ton of flashbacks thrust into the story to EXPLAIN.

In fact, non-linear structure should do the exact opposite. Executed properly it should intensify conflict/tension instead of diffusing it.

For instance, non-linear timelines are fabulous when we want to employ an unreliable narrator.

Gone Girl , Girl on a Train, and Fight Club all shift back and forth in time, but every shift only serves to ratchet the tension higher, to generate even MORE questions. Over the course of the story, the writer might sprinkle in answers, but usually they’re incomplete.

And, every ‘answer’ usually sparks three new questions to take its place.

The reader has to KEEP reading to know WTH is going ON! With nonlinear structure, the story picture will only come into sharp relief in the final chapters of the story.

I LOVE non-linear structure, but it takes a lot of skill to write and, unlike traditional three-act structure, it has a comparably smaller fanbase.

Micro Meets Macro

Sorry, this just cracked me UP! Bwa ha ha ha ha ha ha!

Sorry, this just cracked me UP! Bwa ha ha ha ha ha ha!Why did I talk about the tiny bits of story first? Because regardless which narrative structure we choose for our novel, those micro story structure elements will remain the same.

We’ll still be using scenes and sequels.

Scene: Goal–>Conflict–>Setback/Disaster

Sequel: Emotion–> Thought–> Decision–> Action

These micro elements are what keep readers turning pages. Every sentence becomes a hook that propels the reader to the next sentence and the next. Every chapter should end in a way that compels the reader to keep plunging ahead to get the answers they seek.

What About Memoir?

Some memoirs, as I mentioned, are structured in ways that are very similar to a novel. Excellent memoirs adhere to the same principles that make for excellent novels.

They have a theme, are written for the readers (not the author). They’re structured in a way that ideally lulls readers into a flow state as quickly as possible. Strong memoirs have potent author voice that resonates with the readership. On and on.

This said?

There’s a LOT that goes into writing memoirs, so I’ve gathered a list of what I felt was the best information from those who have FAR more expertise than I do.

Types of Memoir Structure by Dave Hood

How to Structure Your Memoir via Episodia

How to Structure a Memoir That Works by Marion Roach Smith

How to Write a Memoir: 7 Creative Ways to Tell a Powerful Story by Brooke Warner at The Write Life

Literary Structure & Why It Matters to Your Memoir

How to Write Your Memoir With Fun Easy Lists over at my awesome pal Jane Friedman’s site

I could list a dozen more, but this is more than enough to get you started and keep you going for a while. There are plenty of sites out there that can help you learn more about memoir, and many offer templates, books and classes.

Take advantage!

In the end, structure isn’t sexy. You know what else isn’t sexy? Rebar. But without rebar, buildings, bridges and highways collapse. Lots of needless agony, screaming, and suffering…

Kind of like all those books we never could finish *wails*

Structure is that hidden element that holds everything together so our stories can SHINE. When we fully understand how all the pieces go together? THAT is when we can start doing some seriously creative and crazy stuff!

I LOVE HEARING FROM YOU!

I hope today’s lesson helped. I’d wanted to at least introduce y’all to the memoir, because it’s not only an increasingly popular genre, but many of you have stories that need to be preserved.

For the rest of us who don’t dare write a memoir until everyone we’d write about dies? We’ll just have to fictionalize them and put them in a novel

October 21, 2020

Narrative Style: The Heart of Storytelling & Why It Also Matters in Memoir

Narrative style is the beating heart of writing. While our voice might remain consistent from a blog to a non-fiction to a fiction, narrative style is what keeps our work fresh and makes it resonate.

Developing a strong narrative style is especially critical if we decide to write a memoir because the style will need to not only reflect the personality of the author-storyteller, but also hit that sweet spot in tone that is appropriate for the story.

But what IS IT?

Last post, I opened the discussion about memoirs. Memoirs are not only becoming increasingly popular, but with the implosion of traditional publishing, there’s good news. Anyone can write and publish a memoir. There’s also bad news…anyone can write and publish a memoir.

Before we talk about the various structures and types of memoirs, it’s a good idea to first discuss the broad concepts. Last time, I mentioned that superior memoirs frequently DO reflect The Hero’s Journey.

That was our first meta-concept, so to speak. The second meta-concept is narrative style. This aids us in connecting with audiences and generating long-lasting resonance.

Narrative style can be one of those amorphous concepts that’s tough to define directly. Sort of like black holes.

Scientists don’t per se observe a black hole directly, as much as they suspect they might have a black hole because of what’s going on around a certain area in space (the behavior of light and nearby planets, etc).

This said, all creators would be prudent to keep some core principles in mind when writing anything from a blog, to a non-fiction, to a memoir. These principles lay the foundation for what we think of when it comes to ‘narrative style.’

Narrative Style & The Essentials

It’s just wise to appreciate how the human mind works whenever we’re creating. There are certain aspects hard-coded into the brain. Thus, when we grasp the basics of what hooks readers and what shuts them down, it offers major advantages.

Whether writers want to admit this or not, we are creating a product we hope others will pay to consume. That they not only will consume the product, but then will recommend our product to others.

While developing then strengthening our own unique narrative style will certainly help, it will be simpler to explain the impact of narrative style with some context and basic psychology.

Essential #1: Order

Our brains desire order.

The human brain craves order to the extent it will manufacture order when no order exists.

Have you ever been driving and seen an outline on the road ahead? Your heart hitches because you’re certain some poor critter ended up under the wheels of a passing car.

Yet, when you get closer, you let out a sigh of relief because it’s just a rumpled pile of fabric. Someone lost a jacket. WHEW!

This is our brain seeing an outline and configuring the shape into something that makes sense given the context of dim lighting, road, and driving.

It’s also how people see pictures in clouds, whorls of wood, or how some see Jesus on a slice of toast.

MY Jesus is gluten-free

September 14, 2020

The Quest: “The Tip of the Spear” & The Hero’s Journey Meets Memoir

All great books are about the quest. What does the main character (MC) want? Desire is what propels the MC to step out of their comfort zone and dare to do something different.

If Frodo and Samwise didn’t long for adventure, then The Lord of the Rings wouldn’t exist…or would have been a vastly different book. Had Katniss Everdeen been content to allow her little sister to compete in The Hunger Games, odds are pretty good a) it would have been a very short and depressing tale and b) Panem’s Capitol would have been left to continue slaughter for entertainment.

The thing about the quest is that most people long for it. It’s wired into the construct of what it means to be human. Maybe we aren’t daring enough to set out on our own adventure, but we LOVE to experience adventure all the same.

Obviously, there are countless odysseys we can ONLY experience via story. The only way I can ever “live vicariously” as a spy, wizard, vampire, Navy SEAL, etc. is through the lens of others. I can’t travel in space or back through time (as tempting as that high school reboot might be).

Story, then, is my passport into experiences and places that would otherwise be off limits.

Last time, we talked about character development in my post, How Story Forges & Refines Characters. We can conjure a main character in our minds, but the story…the quest ultimately is what adds depth, dimension and resonance.

The Rise of Memoirs

Most of the time, I talk about fiction when it comes to craft. Yet, now that nontraditional publishing has imploded and taken the old business paradigm with it, memoirs are exploding in popularity.

First of all, I think it’s because we’re desperate for new stories and fresh voices and perspectives.

Yet, understand that, under the old business model, it was extremely difficult to publish a memoir unless one was a known celebrity or household name. Memoirs were for movie stars, models, athletes, politicians, or reality television personalities. Publishers wanted *shudders* A Shore Thing, or at least as close as they could get.

*cough* Snookie.

Nothing personal, only simple economics.

In the old days, publishers knew they could probably count on a book about Tori Spelling’s life selling enough copies to make it worth the gamble. Name recognition alone drove sales and still does to a certain degree.

Sadly, this meant a lot of fantastic stories were never put to the page for readers to discover and fall in love.

My Life Would Make a GREAT Book!

Yarmouk Camp. My “home” for a time when I interned in Damascus, Syria.

Yarmouk Camp. My “home” for a time when I interned in Damascus, Syria.If I had a dollar for every time I heard this phrase when I tell people I’m an author. Funny thing is that it’s likely true. Many “everyday” people are anything but. They’ve seen or endured a life even the most creative novelist couldn’t make up.

In fact, their lives might almost be considered “unbelievable” if someone like me tried to put the same events in a novel.

Life really is stranger than fiction.

Today, I’d like to broaden our instruction because most of the elements necessary to create a novel that hooks readers and won’t let them go until THE END are the same for a great memoir.

Memoirs, like novels, are complex creatures, and I’ll be writing more posts on this topic. Yet, where to start? We’ll begin what I believe is a foundational ingredient necessary to write a riveting memoir.

The Quest is Key

Alfred Hitchcock once said, “Drama is life, with the dull bits cut out.” This applies to all stories, including memoirs.

Before we go further, memoir is NOT a synonym for autobiography. Unless we happen to be some super famous person, most folks outside of our family or friends aren’t interested in a detailed account about our lives.

And even then…

Excellent memoirs share two major connections with excellent novels in that a) the memoir is just as much, if not more, about the quest than the person and b) the memoir is for the readers not the author.

I believe Jerry Jenkins said it best in his post How to Write Your Memoir: A 5 Step Guide:

They (readers) care about themselves and what your book offers them. So your theme must be reader-oriented, offering universally true transferable principles that will help them.

So yes, while a memoir is, to an extent, biographical, these key “events” must then be fleshed over a narrative skeleton that offers the audience insight into their own lives and experiences.

The key to figuring out how to write your memoir is focus. What is the quest? Because the quest gives readers the takeaway. This then becomes the spine of your story, where everything else connects. It will help you know what to include and where.

No simple task.

Writing a memoir will demand we sort through a vast litany of experiences to see if they meet the requirement. Which stories are key to the journey, and which stories are simply fun, tragic, or interesting, etc.?

The Essence of Story

When it comes to a memoir (or novel), we’re wise to first ask, “What is the MC’s quest?” Often, we might think, “What is the goal?” Yet, as a stickler for language, I’d like to point our that there’s a distinctive difference between a goal and a quest.

A goal is defined as the object of a person’s ambition or effort; an aim or desired result.

Yet a quest is defined as a long or arduous search for something.

I believe the words long and arduous are what qualitatively distinguish the memoir as more than “non-fiction.” The very definition implies drama, thus delineating the memoir from simple non-fiction.

I’d also like to draw your attention to the word something. In fiction, as in memoirs, the main character of the story is frequently thrust into a decision—remain where you are OR step onto the unknown path.

Once the MC makes this decision, a simple expedition swiftly changes into a life-altering crucible. The journey supplies the heat and pressure required to fire away the dross and reveal the gold.

Memoirs, ideally, are a detailed account of what happened while in the crucible as well as how the author transformed as a result. Obviously, the harder the journey and the greater the change, the better the memoir.

The Quest for “Something”

If I think about my favorite stories, most of the time the MC begins the quest believing they’re in search of one thing, only to realize they’d failed to think big enough.

In Lord of the Rings, Frodo and Samwise certainly had no clue their quest would lead them to an unplanned outward destination, Mount Doom. They had zero concept their purpose in life would also change.

Destroying The Ring of Power was for warriors or wizards, not little nobodies.

Similarly, Samwise and Frodo had no possible way to appreciate how much they would change internally. Their home, The Shire—once a boring place to escape—eventually became the only cause worth dying for.

When it comes to memoirs that stand apart, we see a similar pattern. It isn’t enough to just tell about our lives without the spine. The narrative skeleton is essential for bringing all the parts together and creating something with LIFE!

Common Ground, Common Quest

I love great memoirs because, even if I don’t share anything (surface-wise) with the author, I can identify on deeper levels. Overcoming loss, triumph over adversity, rising above a tragedy, healing from abandonment, etc. are all themes most of us can relate to.

I’ll use one of my favorite memoirs as a good example.

Granted, Kevin Hart’s I Can’t Make This Up: Life Lessons is the life story of a world famous comedian and Hollywood box-office star. But, at the same time, Hart’s story is not only brilliantly funny, it’s also transparent, gritty and heartbreaking.

I might have nothing “in common” with Hart. I’m certainly no world famous comedian/actor. We’re also a different race, different gender, from different parts of the country, on and on.

Yet, in spite of all our “differences,” his memoir hit home. I can relate to being an outcast, the challenges of a dysfunctional family, and what it takes to really never give up on a dream.

I can almost hear y’all now, Kristen! But Kevin Hart is KEVIN HART! You said we didn’t have to be super famous!

Calm down.

The Tip of the Spear

Early in the summer, I discovered a TRUE reading treat, Tip of the Spear by Ryan Hendrickson.

The book is (partly) about Sergeant First Class (SFC) Ryan Hendrickson, a Green Beret tasked with clearing the way for his twelve-man team while conducting combat operations against the Taliban.

As the “tip of the spear,” his role was to clear any IEDs (improvised explosive devices) to make it safe for U.S. and Afghan troops to travel.

On one particular mission, Hendrickson attempted to rescue an Afghan soldier who’d strayed ahead of the group into uncleared territory. In doing so, Hendrickson stepped on an IED which blew off most of his lower right leg, leaving the foot barely attached.

The book details his miraculous recovery, as well as what he endured physically and emotionally while doctors worked tirelessly to save his leg. Hendrickson not only managed to walk again, but he eventually returned to active duty in Afghanistan with his fellow Green Berets.

This alone would have made the book a fascinating read.

The X Factor

SFC Ryan Hendrickson

SFC Ryan HendricksonTo be honest, I normally wouldn’t have gravitated to a military book or memoir. Many focus on an event or a world (e.g. the realm of the Navy SEALs) that I can’t relate to. We share no common ground.

While the stories might be exciting, informative, or interesting, they remain at that surface level because it’s difficult for me to find any takeaway.

Tip of the Spear, however, is more than the typical military memoir. I found it to be very much an intricate tapestry woven from very HUMAN experiences—family, loss, hope, failure, addiction, dreams, determination and triumph.

Hendrickson’s raw openness about his less than ideal childhood, his struggles, doubts, addictions, failures and personal demons supply a whole new level of depth to what easily could have been just another “entertaining” book.

Tip of the Spear has so many positive messages, namely…

It is OKAY to NOT BE Okay

The mark of strength is to admit when you’re drowning, when you simply can’t do it alone. Hendrickson’s story emphasizes how easy it is for pride or self-pity to swamp even the best of us. But, with the support of others, miracles happen every day.

Or maybe that was one of many messages I took away from the book.

Someone else might read and it and this story speak to some deep place vastly different.

THAT is the mark of a superlative memoir (just as it is for a superior novel).

Tip of the Spear stood apart. No chest-beating “lone warrior I did this all on my own” schtick. This is a very poignant, personal drama. There’s a myriad of themes woven into the story—throughout Hendrickson’s quest—that I believe can speak to very wide audience.

This is not just a military memoir but the memoir of a man who “happened to be in the military.”

So You Wanna Write a Memoir

This post is only the first step. To quote the spooky bridge keeper in The Holy Grail…

WHAT is your quest?

Some who set out to write a memoir are like the bold Sir Lancelot and stride confidently (and easily) across that bridge. They’re fully aware of who they are, where they desire to go and why.

Others of us? Yeah. Ask something as banal as our favorite color and that’s enough to catapult us off the path and into the foggy abyss.

In coming posts, we’ll talk more about different types of memoirs and elements like voice, style, organization (structure), characterization, dialogue, etc. Too many set out believing that the non-fiction aspect of a memoir gives an automatic pass on learning these critical storytelling skills used in the best novels.

Untrue.

Additionally, there are a variety of ways to present a life story whether you want to tell your own or tell the story of another (perhaps preserve the life story of a family member).

When it comes to the bits and bobs that might not fit into a narrative style memoir, what to do with those? I have good news there, too. Many forms of storytelling—that the corporate publishing model had pushed almost to extinction—are reemerging with new life and eager audiences.

What is Your Quest? I LOVE Hearing from You!

Have you ever wondered how to take your life and put it into a story form that others would want to read? To have a way to preserve your quest, leave a legacy? Maybe you’ve been through trials that aren’t only interesting, but maybe instructive or inspiring?

Do you have family stories that you’re eager (even desperate) to preserve? I know one of my main regrets was I lost my mentor and inspiration, my Great Aunt Iris (who lived almost to 100 years old) before I could get her to tell me in detail about her life.

She was born picking cotton in East Texas, yet was the first of the children to leave for college and earn a degree in a time women rarely gained higher education. My aunt started her life in a world with no airplanes, radios, or television, when they had to saddle horses and hitch up wagons to go anywhere.

She passed away in a world with space travel/exploration, the internet, cell phones, and female C.E.O.s. Now THAT is one heck of a quest!

I mourn the loss of her experiences, but maybe I can write about my own quest and adventures for my son and (hopefully) grandchildren. My goal with this series to to help you tell the best stories possible.

What are YOUR stories? WHAT is your QUEST?

September 3, 2020

Character Building: How Story Forges & Refines Characters

Image courtesy of Kevin Wood via Flickr Creative Commons

Character building is essential for telling stories that readers a) can’t put down and b) will never forget. Why am I now talking about character building, since I know I have a reputation for focusing a lot of blogs and classes on story structure?

Stories, like other complex creations, are comprised of multiple parts. If we build a car, the body of the actual vehicle is essential. Everything else will attach to that frame, either inside or outside.

Regardless how innovative and imaginative the frame, I’d argue the engine is a pretty big deal or we’re left with a very large and expensive paperweight, doorstop, or garden planter.

When it comes to designing a car, we won’t get too far without wheels, and brakes might be a good idea as well. Yet, choosing a leather interior or cloth or what color the car might be? Not high on the priorities about making the car actually WORK.

Structure is the delivery system/engine of story. If we keep starting, stopping, flashing back, including too many POVs that aren’t salient to the overall tale? The reader is likely to finally get frustrated and give up.

While structure might be the engine, is it driving anything (plot problem) or anyone (characters) interesting?

Study & Character Building

I put in a lot of work and study when it comes to honing my writing skills. This means I’m always searching for ways to become a stronger author and craft teacher.

Want to get better at anything? Look to those who are the best at what they do and pay close attention. The best way, and a requirement for anyone in the writing profession, is to read…a lot.

I read a ridiculous amount of fiction. Since I have little time to actually sit and read for long periods of time, I’ve had to retrain my brain for audiobooks. Audiobooks are a life-saver, since life didn’t decide to suddenly pause because I wanted to be a writer.

***My dishes and laundry are apparently in control of cloning-technology they refuse to share.

This said, however, I listen to an absurd amount of books in virtually all genres and use this as training. When I encounter a superlative character? I usually buy the paper version then—like the monster I am—dog-ear, highlight, and make notes.

Studying other works offers an excellent education about character building for those willing to pay attention.

When you encounter a character that resonates, then ask why? What intrigued you? What made this particular character stand out/memorable? How did the author manage to do the same but different?

Characters of Note

I tend to go through binges in genres, though I believe my go-to favorite are mysteries. For instance, Sherlock Holmes is a character that’s been reimagined countless times and in varying forms largely because he’s incredibly unique and possesses seemingly endless depths for new authors to plumb.

After eating through all the Sherlock Holmes stories, I began searching for other detectives set in late 19th century London.

I fell in LOVE with Will Thomas’s Barker & Llewelyn Series.

Not only are the mysteries masterfully crafted, but Thomas has created such an incredible cast of characters that it’s hard not to get sucked into the entire series.

While he could have gone with a Sherlock/Watson knock-off (and plenty have), he took the template and created a crime-solving duo that was wholly fresh and new.

Thomas equipped Barker and Llewelyn with such intricate and idiosyncratic backgrounds (much shrouded in secrecy) that he crafted two characters unlike any I’ve encountered.

It is their SECRETS that provide the fuel for story, tension, and resonance. I kept reading because I wanted to know WHY Barker wore dark glasses and refused to show his eyes. How did a Scotsman come to be fluent in Mandarin and the master of so many unique fighting styles?

Why was Llewelyn sent to prison when he was a student at Oxford? How did he become destitute? Not all my questions were answered in one book. I had to keep reading to get to know the characters that so fascinated me.

Characters sold the stories, and eventually the entire series. I’d venture to say it’s why readers fall in love with series. Series give them a chance to know the characters better, understand them, and bond in a way that makes the final book feel like a death.

Character Creation

I thought back over works I’d edited, earlier stories of my own and had a moment of revelation. Why were some characters so flat? As interesting as some form-molded widget from a factory?

Conversely, what made other characters almost come ALIVE?

What was the X-factor?

Now that I’ve noodled this, I’ve revised some of my thinking. Multi-dimensional characters are not something writers can directly create. Rather, these lifelike people are forged from the crucible of story.

Dramatic writing uses a core problem (fire). The core problem generates escalating problems (the hammer). The trials (increasing heat/hammering) reveal, refine, define, and ultimately transform the narrative actors into characters.

Story alone holds the power to bestow resonance.

Character Building: Dangers of ‘Fill-In-The-Blank’ People

Character profiles can end up a lot like dating profiles…and about as helpful.

Height, weight, build, nationality, attractiveness, education level, how many kids, previously married, hobbies, etc.

Dating profiles also provide blank spaces for additional ‘deep, character-revealing statements’ such as: I’m not a game-player, love Mexican food, and my favorite activities are cross-fit and hiking.

FYI: ALL of that is likely a lie (other than enjoying Mexican food). Anyone who starts with I am not a game-player is almost guaranteed to be a game-player. It’s Shakespeare’s Rules of Romance. Or, as I call it, ‘The Lady/Dude Doth Protest Too Much’ litmus.

Anyway…

No School Like Old School

….or not.

Do I create character profiles? Sure. I also put a lot of thought and research into what ‘people’ I want to cast in a given story. It’s a great activity, but be careful. We can’t camp there. Activity and productivity are not synonymous.

Ultimately, fictional characters reflect the real human experience in a distilled and intensified form. This, however, doesn’t give an automatic pass on authenticity.

Aristotle might be Old School, but his observations regarding drama resonate even into the 21st century. In Aristotle’s Poetics he asserts:

Since the objects of imitation are men in action, and these men must be either of a higher or a lower type (for moral character mainly answers to these divisions, goodness and badness being the distinguishing marks of moral differences), it follows that we must represent men either as better than in real life, or as worse, or as they are. ~Aristotle

This gives three schools: Polygnotus (more noble), Pauson (less noble), and Dionysius (real life).

Even today these three schools of story thought are alive and well. Marvel’s Captain America movies proffer the larger-than-life hero, the man better than real men (Polygnotus).

Westworld and Game of Thrones provide a vast assortment of villains who are worse-than-life, an exaggeration of evil (Pauson).

Then, movies like Training Day or Glengarry Glen Ross show men as they really are…flawed. They’re not entirely noble or ignoble (Dionysis).

Granted, this is a vast simplification, but we can see novels fall into these schools as well. Genre dictates a lot of this. Harry Potter, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, and A Man Called Ove could reasonably be placed in each category.

Character Building: Talk is Cheap

Why do I mention these ‘schools’ of story? Depending on genre, readers will have expectations when it comes to what they’ll find entertaining. As writers, our primary job is to entertain.

This said, stories are for the audience. This means we need to either serve them what they enjoy, or serve them what they don’t yet know they will enjoy

August 26, 2020

Finding Our Focus During Crazy Times: Only So Many Ducks to Give

Finding our focus has never been easy. Many of us have always lacked direction and fallen short on “clarity.” We’d multitasked ourselves into a daily fugue state long before COVID and quarantines and Zoom upended our lives.

Time somehow seeped through an unseen hole, leaking away one errand, email, trip, chore, or event at a time.

Ironically, I wrote a blog post Quiet: Have We Forgotten to Be Still in a World That Never Stops? back in February.

Um, so yeah. Oops. #CarefulWhatYouWishFor

Yet, to be blunt? At the time I wrote that blog, our Normal meant living life strapped to Hell’s Tilt-A-Whirl every…single…day. That is NOT healthy. We needed rest, quiet time and peace, yet we were threadbare and run ragged.

I apologize for not posting for a while. It’s been VERY odd, especially since I’ve posted religiously no matter what for almost fourteen years. Suffice to say, this year—which started with yet another death in the family—had me ground down and exhausted. I seriously needed a sabbatical to recharge.

Moving on…

Focus & The “New” Normal

Nah, let it starve…

Nah, let it starve…So maybe we’ve had enough “quiet time.” We miss getting out, socializing, and long for the days when shopping for groceries didn’t require sanitizer, gloves, face masks, eye-balling six feet for social distancing, and a canteen of holy water.

Alas, there are a handful of phases or words guaranteed to make me twitchy. One is this idea of a “new normal.” First of all, every day is a “new normal.” The entire GOAL of human civilization is to change, ideally for the better.

If we aren’t changing, we’re dying.

That aside? Normal doesn’t exist, other than as a setting on the dryer. And when I hear others (and myself) bemoaning all the changes and trials and wanting to “get back to normal,” I cringe. NO. I don’t want things back the way they used to be, namely because I believe we can do better.

COVID and everything that’s gone with it sure has been a trial. Some have suffered terrible losses, hardships and/or setbacks. But I refuse to endure these tests and tribulations only to go BACK.

Because what was BACK THERE wasn’t all that great.

Nostalgia can be misleading. It’s like that ex we keep returning to because we keep forgetting WHY we dumped the @$$hat in the first place.

Nostalgia can lure us to focus on only what was good, and forget what was broken. Nostalgia cajoles us into dismissing why we were burned out, stressed out and ready to crack.

Since we don’t have a time machine, we’re in this together.

If we focus on all “we’ve lost” then that’s wasted effort that only makes us feel crummy and powerless. We can’t undo what is done, but we can assess, adapt and overcome. THAT is active, offers us agency, and a reason to hope.

Where the Mind Goes, Man Follows

A look into where my mind has been. I MUST KNOW!

A look into where my mind has been. I MUST KNOW!When I first started toying with the idea of writing professionally, I had an idea for a book set in Monte Carlo, with the Formula 1 Monaco Grand Prix as a backdrop. Being bold and brassy, I somehow talked my way into some of the inner circles of Ferrari racing.

Though I never finished the book, I did have a great time and learned a lot of key lessons that would carry me through much of my professional life. One lesson in particular stands apart.

We go where we focus.

In professional racing, a lot of winning involves not crashing. Simple, right? If your car is a pile of wreckage, then chances of crossing that finish line go quickly to ZERO. High speed racing—particularly in places like Monte Carlo—are unusually challenging.

Why? Because it isn’t as much about driving faster than the competition, as it is about driving better than the competition. Monte Carlo is a maze of hairpin turns. Not only must a driver be mindful of the wall, but of other drivers as well.

What I learned was this: If you look at the wall, you’ll hit the wall.

The driver must always be keenly aware of where he has his focus, because focus on the wall? You’ll hit the wall. Focus on the other cars? You’ll hit the other cars. Focus on where you want to go? That’s where you’ll naturally drift.

It’s why it’s so crucial to phrase objectives in the positive. Remember you put your keys next to the door is much more effective than telling yourself Don’t forget that you put your keys near the door.

The human brain tends to only start listening at the first ACTIVE verb, and that’s where it will focus. If we say, Don’t forget to pick up cat food, our brain hears, Forget to pick up cat food.

Watching our words and how we speak can drastically improve focus for the better. POSITIVE goals! Instead of, I don’t want gain anymore weight, try, I want to be healthy and properly proportioned

July 9, 2020

Advice: The Great, the Bad & Good Intentions Turned Toxic Dogma

Advice floats around everywhere. We get it from friends, family, cutesy memes, gurus, life coaches, books, television, podcasts and…bloggers *giggles*. We’re subjected to advice, whether we want it or not.

Please, let me be clear. Wise counsel is a good thing. Definitely.

We certainly don’t want to try and do this “life thing” with zero guidance. But the influx of so many opinions can be confusing, maybe even make us a tad crazy.

But these days, advice has gotten out of hand. It’s even invaded fortune cookies. Our FORTUNE COOKIES! Yes, we’ve been ordering a lot of take-out recently.

Remember those who persist enjoy success.

Okay, I’m throwing a flag on the play. THAT???? Is NOT a fortune cookie. Fortune cookies don’t offer unsolicited advice. I have a mom for that (I love you, Mom).

A fortune cookie is FUN and something we know is probably bunk, but would be super cool if it were true.

You will soon have good fortune in your endeavors.

Granted, we have no idea WTH that means. Maybe it’s good fortune regarding our endeavors investing in the stock market. Or maybe it’s our endeavors finding the bottom of that master closet we’ve been promising to clean out for three years. That isn’t the point.

Fortune cookie? FUN. Lecture Cookie? NOT FUN.

Great Advice

Ah, who doesn’t love great advice? Granted, there are certain tenets that remain true no matter the time period we happen to be living in. Most of us don’t struggle in those areas. Like probably a good idea not to murder people or go around robbing banks.

We’re solid on those, hopefully.

Since I talk mostly about writing, publishing, and the processes and components of success on this blog, we’re going to narrow the scope a bit.

If you want to write professionally—or do anything at the professional level—then the greatest advice I’ve gathered, is to learn everything you can about what you’re doing.

#NoDuh

For novelists, we can’t break rules until we understand the rules. My advice is to read a TON of fiction—I recommend reading extensively inside as well as outside of the genre you wish to master. Add in reading craft books, blogs as well as taking classes. Then practice, practice, practice.

I learned all this the hard way, which is one of the main reasons that, even though I’m a recognized expert at branding and platform building, I still dedicate a lot of time and effort to teaching craft.

When we struggle? Then it’s time to seek out colleagues and professionals to teach us how to deal with specific issues. This advice is instructional, but still put a pin in this.

Back in the day when I was new? When it came to writing fiction, I had zero idea why my submissions kept getting rejected.

Professional Advice

After banging my head into a wall enough times, I finally reached out to an expert who did me the favor of telling me the truth. He gave excellent advice. I didn’t understand structure. My story was…all over.

That’s saying it nicely.

With this critical bit of insight, however, I could formulate a strategy. I went to everyone I respected to explain story structure and then I studied.

I read countless books, then broke those stories apart. Not only that, I made sure to do this in all genres, with every variety of structure.

I even applied what I was learning to movies and television series and dedicated countless hours until I turned what had once been my greatest weakness into one of my greatest strengths.

Sure, I continued to hone my other skills. But, I also understood that anyone considered “great” stood on the shoulders of those who’d come before.

Why reinvent the wheel? The wheel works!

Advice can be critical and can shorten the learning curve significantly. We can transition from neophyte to the artist we long to be in a MUCH shorter time frame if we’re humble enough to seek outside help.

The Art of Discernment

Immersion and mastery is critical. This is true in all professions, not just in writing.

But there is another benefit that comes from gathering all the guidance you can from those whom you respect, then giving their suggestions at least a try. You learn what works, what doesn’t, and what might need to be modified.

It also keeps us from falling into fads, and being tossed along on the tides of other people’s opinions.

We gain a sense of who we are and that, what might be a fantastic approach for one author (or entrepreneur, marathon runner, parent, etc.), might not be the best for us. Better still, we’re able to articulate WHY this or that tactic does or doesn’t work for us.

Bad Advice

This is where things might start to get a bit hazy, because in many instances, bad is subjective. Also bad advice and good advice are fluid.

Life isn’t static.

What worked great for me this time last year, certainly crumbled once my health collapsed this past winter with what was deemed a COVID-LIKE ILLNESS.

I can preach all day long about persistence and why emotions can’t dictate putting your @$$ in the chair and getting words on a page—and have—but when you can’t even make it out of bed?

That advice goes out the window…along with anyone giving it. KIDDING!

….I wouldn’t have been strong enough

June 16, 2020

The Johari Window: Understanding & Harnessing the Character Blind Spot

The Johari Window can be one of many powerful tools for crafting dimensional characters. It can also help creators develop layered stories (plots) that will resonate long after the audience reaches ‘The End.’ Why? Because great fiction is even better therapy.

Too many believe fiction to be a fluff, an escape, a fantasy getaway. Some fiction does this for sure. Yet, the stories that hit the market and continue to ripple for decades, centuries, or even for millennia share a common denominator.

They offer the audience deeper insights into themselves, their beliefs, and the world around them. Also, their messages are timeless. It’s why we can take a Shakespearian play and set it in modern times and the story and message are just as powerful.

The characters might wear modern clothing, fight with machine guns instead of swords, but we identify with their hopes, dreams, hurts, struggles and weaknesses just as much as the audiences from centuries ago.

What is the Johari Window?

American psychologists Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham developed this model in 1955 as a way to improve group dynamics. The Johari Window is a technique used to refine and boost feedback, prompt disclosure, and ultimately deepen self-awareness.

‘Johari Window’ derived its appellation using a combination of the two psychologists’ names.

The model is founded on two fundamental ideas.

First, that trust is earned when one reveals personal information to others.

Second, that this information then leads to feedback from others which can then give the person a more accurate ‘reality.’

Using feedback, we can become more self-aware and change accordingly.

The Johari Window Structure

Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.The Johari Window consists of four ‘panes.’ Two panes reflect the self and the other two represent blind spots and areas unknown to the self but visible to others.

The first pane is the most open. This is information a person knows that others know as well.

The second pane is the blind spot. Often this is what others can see, that the person (character) cannot.

The third pane is a hidden area containing information the person knows, but hides from others.

The fourth pane is the Unknown area, the place where all parties are completely in the dark.

Creating a Character

The blind spot is critical for creating a dimensional protagonist who can arc to becoming a hero. Ideally, we want to design a story problem that forces the MC (main character) to finally see their blind spot and how it’s negatively impacting their lives (and others).

The story problem is the crucible. If our MC had never encountered the story problem, they would have remained ignorant of a critical weakness.

Other characters in the story (mentors, allies, antagonists) represent the sounding board that drives that final self-awareness and group understanding.

Ideally, by the end of the story, the MC has dealt with the blind spot, and the Unknown quadrant will be markedly smaller.

Applying the Johari Window for Fiction

Now that I’ve explained what the Johari Window IS, how can we apply it practically if we don’t work in HR?

Instead of using a movie or book, I’ll riff a quick example. It’s rough and imperfect but most novels are in the beginning. The key is that we at least get off to a sound start with a solid story foundation.

Let’s say I want to write a Young Adult Urban Fantasy about a teenage girl, who, after a bad accident, starts having nightmarish hallucinations.

She’s unaware that she can actually see into the future.

Pane #1

This is information my character knows mixed with what others also know. This is usually very surface.

For instance, the character, her fellow students and teachers know her name is Sarah Smart, that she has lank dark hair and is spindly thin. She’s a sophomore at Small Town High who performs just well enough to pass her classes.

Sarah is a loner who sports combat boots, spiky jewelry, and concert shirts from various heavy metal bands.

She doesn’t have friends, lives in a rundown area of town, and rarely talks to anyone. Though she doesn’t cause trouble, she goes to great lengths to push people away. Perhaps she answers any questions with closed-ended, yes-no answers.

Maybe she cuts class, or retreats to the library whenever there’s a pep rally. She also constantly chews aspirin.

All this ‘information’ is obvious to Sarah and those around her.

Pane #2

This is Sarah’s blind spot. Others might see areas of the blind spot, but Sarah will be oblivious.

Sarah fails to see herself the way others do. In her mind, she’s not hurting anyone and wants to be left alone. Others, however, find her caustic, abrasive, stuck up, or just plain weird.

Sarah thinks she’s crazy, her headaches and visions a remnant from a head injury suffered in a bad car accident.

Pane #3

This is what Sarah knows that others do not.

Her mother who, after almost twenty years sober, now drinks every waking hour. Mom fell apart after her only son (Sarah’s brother) drove the family car headlong into a tree and *died.

The tox screen indicated he was well over the legal drinking limit. Also, witnesses claimed to have seen him swerving and driving erratically, thus the town rumor was that he was driving under the influence.

His body was so mangled, Sarah and her mom had to hold a closed casket funeral.

The town gossip grew so bad, Sarah and her mother had to move. No one in the new town or school knows about her brother, the accident, or her mother’s severe drinking problem.

Right after the hospital released Sarah, she suddenly started getting bad headaches coupled with terrible and confusing visions. She has no idea what’s happening and believes she might be going crazy.

Perhaps, she believes the headaches are from the accident, the visions are due to her guilt. Why did she let her brother drive? Why did she not see he was unfit to drive?

She hadn’t even seen him drinking. He hated alcohol because of what it had done to their parents. But the tox screens don’t lie, right?

His death is all her fault and these headaches and nightmarish visions are her punishment.

Pane #4

This is the information unknown to all parties involved (at least in the beginning). Sarah isn’t going crazy, she actually has the ability to see into the future.

Her brother wasn’t drunk at all. He, too, had the same gift—he could see into the future—and was hit with a vision while driving which caused him to lose control of the car.

This is also what will form the basis for the story problem (more on that in a moment).

Sarah actually wants friends, to be part of a community, but is too ashamed and afraid. The story problem will change this and shrink the Unknown for Sarah as well as those around her.

Story Problem

Using this quick exercise with the Johari Window, it’s now easier to construct a story that will force Sarah to face what she fears (that she’s going crazy) and to make peace with her inner demons (guilt about brother’s death).

Ideally, it will drive Sarah onto a path where she’ll gain mentors and allies. The more awareness she gains, the more information she shares, the closer relationships she will form.

Story Problem: What if Sarah’s brother actually is NOT dead?

If we take a page from to hit Netflix series Stranger Things, maybe some black bag government operation had been watching her brother.

He’d been in counseling, discussing his visions and someone with a lot of power realized they weren’t hallucinations at all. Rather, the young man could actually see future events.

At the time of the accident, this agency saw the perfect opportunity to abduct the brother. They substituted another (badly mangled) body, forged the tox screen and dental record match, then helped spread rumors the young man died drinking and driving.

This agency is now using him in some underground bunker to predict terrorist attacks.

Normal World

We get to know Sarah in her regular, but broken, world. See her picking up empty bottles of cheap vodka and putting her mom to bed before she heads off to school. Maybe she prizes a photograph of her ‘dead’ brother out of Mom’s hands as she tucks her in to sleep off the booze.

At school, Sarah sits on the sidelines wanting to be part of the group, but pushing away anyone who tries to be friendly. Maybe she runs into a new substitute teacher who sets off all her spidey senses, but she has no idea why (he’s an agent following to see if Sarah, too has the gift).

The substitute teacher is a proxy, and how we introduce the Big Boss Troublemaker—the black bag agency that has her brother hostage and wants her, too.

Sarah later talks to a teacher, only to have to cut the conversation short because of one of her headaches. In the bathroom she’s knocked to her knees with a vision of a fellow student run over by a jock speeding through the parking lot, but dismisses it.

Only a nightmare. A hallucination.

She firmly believes this until she’s leaving school and the leading action preceding up to the event plays out exactly as she’d seen it happen in her vision.

This time is different. She takes action.

Sarah dives after the kid, preventing them from being run over. The fellow student likely will be her first ally.

Yet, her direct intervention into a future event will also be the signal that lets the enemy know Sarah does have the gift they seek.

This is a turning point for the BBT—she’s like her brother and they want her, too. It’s also a turning point for Sarah—maybe she isn’t crazy after all.

Plotting from the

See how using the Johari Window we’ve created a dimensional character with a lot of baggage, issues and self-doubt? This knowledge also offered a clear way of seeing a solid story problem that would make Sarah grow.

What would she want more than anything? To have her brother back.

If she starts suspecting she isn’t crazy, this propels her on a search that will begin revealing that she actually does see the future, her brother had the same complaints, and if he had her gift? Maybe he isn’t dead.

She’s propelled down a path searching for answers, a road that will inevitably lead to finding out the truth.

We also have an accurate picture of her in her community in the beginning and a good map of where the story needs to go.

If it begins with Sarah as a loner, wracked with guilt and shame and alone?

Then it should end with the family restored and those responsible for taking her brother defeated.

She also won’t do this all alone because as she grows, gains feedback, and information flows freely, the Unknown—there is a secret agency that abducted her brother—shrinks significantly. Sarah, freed from false guilt and shame, should be a far different person at the end.

Also, those around her, will see her with different eyes.

Sarah isn’t some weirdo jerk with a chip on her shoulder. She’s their friend, ally and she has very special powers. The entire group has new knowledge, which creates a powerful and unique bond.

There really IS a world of black bag operations, underground bunkers and dangerous men in suits willing to do anything, even kill, in order to abduct teens with special abilities to use or weaponize.

Story as Therapy

Most good fiction is a journey to self awareness. We have a protagonist in his/her normal world. Everything is fine…but not really.

There is a critical missing piece keeping the protagonist from being self-actualized. This is plainer to see when we realize that most beginnings and endings of novels (and movies/series) are actually bookends.

Normal world is their world with the wound festering and hidden. The denouement? The world is restored but whole, wounds exposed to heal.

All of us have blind spots. If we didn’t, therapists would go bankrupt and have to get a ‘real job.’ Truth is, most therapists know exactly what our problem is the first day we sit in their office. Problem is there are all kinds of other emotions clouding our vision.

This is one of the reasons shrinks do a lot of listening, nodding and asking questions. And probably a lot of doodling and playing tic-tac-toe on their notepads to stave off the boredom while they wait for us to catch up to the obvious.

Our story problem in a sense is extreme therapy for the protagonist. Instead of our character spending years on a couch being probed with uncomfortable questions and given homework to write letters to her inner child?

She is thrust into a bank heist, an alien invasion…or her brother is abducted because he has visions of the future that others want to use for their own ends.

The ‘Johari Window’ as Writing Tool

There are countless methods for creating a cast of dimensional characters. But, when I recently taught my new class on the Unreliable Narrator (now available ON DEMAND), I mentioned the ‘Johari Window.’ Yes, it’s a therapy technique as well as a tool to improve communication.

But, I hope my example above showed you how you might employ the four panes to craft deeper, more layered characters. How it can also help us make sure we’re choosing the best story problem that will drive the most change.

What are your thoughts? I LOVE hearing from you?

Had you ever heard of the Johari Window? Are you eager to give it a try? I’d only tinkered with the concept mentally until I wrote this post, but I was able to create a character and a pretty decent plot problem in about an hour.

I’d love to hear from anyone who tries this and your results! Or if you’ve used it before and how it worked out. I know it’s a rather odd leap from a tool used by many companies as more of an HR tool, but writers are masters of repurposing

June 2, 2020

Wounds: Unforgettable Characters are Fashioned from Damaged Pieces

Wounds matter in life and in fiction. We’ve all been hurt in some way and to some degree. Just goes with being human.

Admitting weakness, failure, mistakes, and flaws isn’t always easy. In fact, it can be downright terrifying for even the ‘strongest’ of us. It’s an especially daunting task in a world that idolizes something none of us will ever be…perfect.

Wounds are part of the human experience. When we understand the nature of wounds, our fiction becomes all the richer just by adding in these layers.

All genres and all stories require wounds. No wound and no story. Even The Little Engine That Could had self-esteem issues and a confidence problem

May 26, 2020

Deception as a Storytelling Device: Introducing the Unreliable Narrator

Deception is a marvelous technique for the seasoned storyteller. Once one masters the basic skills (check out my new plotting class), this then frees the artist to begin honing more highly advanced techniques for beguiling audiences.

Of all storytelling techniques, I believe my favorite is the unreliable narrator. Deception is key in order to successfully pull off this charade. No duh, right?

Yes, but easier said than done.

The one advantage we authors have going for us is that trust is one factor audiences assume as a given from the beginning.

Silly Reader, Tricks are aren’t just for kids.

Deception generally isn’t something readers expect, because narrators act as our guide and filter for the story. If the narrator doesn’t know something or show us something, it’s hard work for us to maneuver the fictional world.

We trust the narrator to be our guide in a world that is formed in the imagination of the author. Also, I’d venture to say most audiences don’t expect the unreliable narrator, simply because this sort of literary guide, proportionally speaking, is rare.

There are a number of reasons for this.

First, the unreliable narrator takes skill, tenacity and a certain amount of bravado to write. The author must use deception much like a magician, knowing when to hold back and when to let the rabbit out of the hat.

Also, good authors, like skilled magicians, must master more than one illusion to keep audiences hungry for more.

Deception is Anathema

In polite society we trust. When we ask a person their name, we assume they are telling us the truth. We buy a can of corn and trust that the can does, in fact, contain corn.