Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 48

November 28, 2016

A Hrishikesh Mukherjee film festival

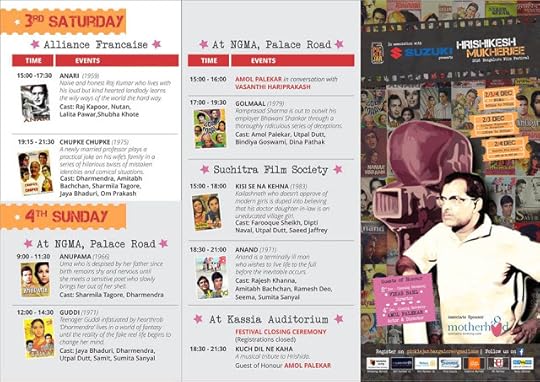

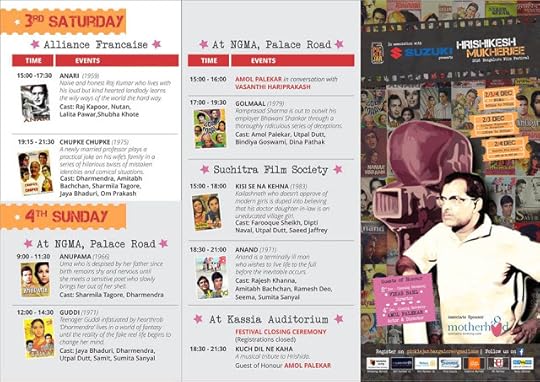

People in Bangalore, here's something you might be interested in - a three-day Hrishikesh Mukherjee film festival featuring 13 of his films (and including some of my personal favourites: Anuradha, Satyakam, Guddi, Gol Maal). The organisers, Pickle Jar, very kindly invited me to come across and maybe introduce a film or two, but I can't make it. It should be great though - do spread the word. See the images below for the schedule. And the Facebook link for the event is here.

Published on November 28, 2016 09:40

November 22, 2016

Anticipating Arrival (and a plug for Ted Chiang's "Story of Your Life")

I learnt only yesterday that the new sci-fi film Arrival is based on one of my very favourite novellas, Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life”. Judging by the Wikipedia entry for the film, the adaptation makes significant departures from the original, with a more action-driven narrative – which is fine; I look forward to seeing the film, sulking about some of the changes while also (hopefully) appreciating some of the others. But I thought I’d use this opportunity to point you to Chiang’s haunting story. I first read it in Brian Aldiss’s anthology A Science Fiction Omnibus (the revised and updated 2007 edition), and being unprepared as I was for what the story was about, the first few pages made for very strange reading.

To start with, the tenses seem all mixed up. You figure out soon enough that the narrator is a woman addressing her daughter, but it takes a while to understand at what point in their personal histories this narration occurs. The “present” seems to be the moment where the woman and her husband decide to have a baby (the story’s opening line is “Your father is about to ask me the question”), but does this mean she is telling the story to a child who does not yet exist? And is she speaking of future events as if they have already occurred? What’s with the many disorienting sentences like this one: “I remember what it will be like watching you when you’re a day old.” Or “I’d love to tell you the story of this evening, the night you’re conceived, but the right time to do that would be when you’re ready to have children of your own, and we’ll never get that chance.”

To start with, the tenses seem all mixed up. You figure out soon enough that the narrator is a woman addressing her daughter, but it takes a while to understand at what point in their personal histories this narration occurs. The “present” seems to be the moment where the woman and her husband decide to have a baby (the story’s opening line is “Your father is about to ask me the question”), but does this mean she is telling the story to a child who does not yet exist? And is she speaking of future events as if they have already occurred? What’s with the many disorienting sentences like this one: “I remember what it will be like watching you when you’re a day old.” Or “I’d love to tell you the story of this evening, the night you’re conceived, but the right time to do that would be when you’re ready to have children of your own, and we’ll never get that chance.”

Those of us who can read comfortably and fluidly in a language sometimes take the reading process for granted, but with this story I felt at times that (despite the conversational directness of the prose) knowing English wasn’t enough; the author had taken away some of the reader’s safety nets, our assumptions about how a story should be told. (During the first few minutes of my first read, I even wondered if there had been some copy-editing errors.)

But this is deliberate, and very much part of the point. “Story of Your Life” is about many things – parental love and grief, seven-limbed extraterrestrials, the illusion of free will, the nature of time – but it is also in an immediate sense about language and how it affects our experience of the world. (No spoiler alerts needed here – the story’s value lies in the way it is told, not on the plot points.) The narrator is a linguist whose attempt to understand the complex language (Heptapod B) used by visiting aliens eventually leads to her perceiving the events of her own life in simultaneous rather than sequential terms. This is the central premise of a story of tremendous emotional power, which is on one level about a specific person grappling with too much knowledge – and the joy and pain it brings – but also on another level about the difficulties of true communication and understanding. Highly recommended: read it before or after watching the film, or even if you don’t plan to watch the film at all.

(A sample passage: “Usually, Heptapod B affects just my memory: my consciousness crawls along as it did before, a glowing sliver crawling forward in time, the difference being that the ash of memory lies ahead as well as behind; there is no real combustion. But occasionally I have glimpses when Heptapod B truly reigns, and I experience past and future all at once; my consciousness becomes a half-century-long ember burning outside time. I perceive – during those glimpses – that entire epoch as a simultaneity. It’s a period encompassing the rest of my life, and the entirety of yours.”)

To start with, the tenses seem all mixed up. You figure out soon enough that the narrator is a woman addressing her daughter, but it takes a while to understand at what point in their personal histories this narration occurs. The “present” seems to be the moment where the woman and her husband decide to have a baby (the story’s opening line is “Your father is about to ask me the question”), but does this mean she is telling the story to a child who does not yet exist? And is she speaking of future events as if they have already occurred? What’s with the many disorienting sentences like this one: “I remember what it will be like watching you when you’re a day old.” Or “I’d love to tell you the story of this evening, the night you’re conceived, but the right time to do that would be when you’re ready to have children of your own, and we’ll never get that chance.”

To start with, the tenses seem all mixed up. You figure out soon enough that the narrator is a woman addressing her daughter, but it takes a while to understand at what point in their personal histories this narration occurs. The “present” seems to be the moment where the woman and her husband decide to have a baby (the story’s opening line is “Your father is about to ask me the question”), but does this mean she is telling the story to a child who does not yet exist? And is she speaking of future events as if they have already occurred? What’s with the many disorienting sentences like this one: “I remember what it will be like watching you when you’re a day old.” Or “I’d love to tell you the story of this evening, the night you’re conceived, but the right time to do that would be when you’re ready to have children of your own, and we’ll never get that chance.”Those of us who can read comfortably and fluidly in a language sometimes take the reading process for granted, but with this story I felt at times that (despite the conversational directness of the prose) knowing English wasn’t enough; the author had taken away some of the reader’s safety nets, our assumptions about how a story should be told. (During the first few minutes of my first read, I even wondered if there had been some copy-editing errors.)

But this is deliberate, and very much part of the point. “Story of Your Life” is about many things – parental love and grief, seven-limbed extraterrestrials, the illusion of free will, the nature of time – but it is also in an immediate sense about language and how it affects our experience of the world. (No spoiler alerts needed here – the story’s value lies in the way it is told, not on the plot points.) The narrator is a linguist whose attempt to understand the complex language (Heptapod B) used by visiting aliens eventually leads to her perceiving the events of her own life in simultaneous rather than sequential terms. This is the central premise of a story of tremendous emotional power, which is on one level about a specific person grappling with too much knowledge – and the joy and pain it brings – but also on another level about the difficulties of true communication and understanding. Highly recommended: read it before or after watching the film, or even if you don’t plan to watch the film at all.

(A sample passage: “Usually, Heptapod B affects just my memory: my consciousness crawls along as it did before, a glowing sliver crawling forward in time, the difference being that the ash of memory lies ahead as well as behind; there is no real combustion. But occasionally I have glimpses when Heptapod B truly reigns, and I experience past and future all at once; my consciousness becomes a half-century-long ember burning outside time. I perceive – during those glimpses – that entire epoch as a simultaneity. It’s a period encompassing the rest of my life, and the entirety of yours.”)

Published on November 22, 2016 23:22

November 19, 2016

Some more thoughts on this currency/demonetisation mess...

... and on an empathy deficit that is now rivalling the shortfall in cash. I’ve been seeing and hearing a lot of the Mahatma Gandhi quote “Recall the face of the poorest and the weakest man whom you may have seen, and ask yourself if the step you contemplate is going to be of any use to him.” It’s a fine thought (and one that can be put to good ironic use these days, what with Gandhi’s face on currency notes smiling gently at – or, if you squint hard, mocking – poor people who can no longer use their cash), but it isn’t a practical one. Very few of us can pretend to be saints who adopt that stance in our daily lives – or even once in a while, when agonizing over major decisions.

Perhaps a more realistic talisman would go something like this: each time you feel tempted to comment on an issue that you have been directly affected by – but which you know is ALSO affecting the lives of people who are much less fortunate – in any such case, before you make that sweeping statement, please count to twenty quietly; introspect a little, allow yourself to consider the possibility that there are things you have been shielded from, that the worst of what you have personally gone through is not necessarily the worst that anyone else might experience.

If you have spent a tough few hours in a bank queue (perhaps made a little less tough by the entertaining conversations around you, or the weather being relatively pleasant, or the option of playing a game on your smart-phone) and felt the relief of having seen some money at the end of it, along with the satisfaction of having contributed to the grand National Cause in some yet-to-be-fully-perceived way – even in the self-congratulatory euphoria of this moment, give yourself some time to consider those who may be facing greater hardships, and much more serious repercussions when they leave their work for days on end to stand in lines.

Consider that if you’re reading this post, that in itself is a guarantee that you are immeasurably better off than a very large number of people in this country. That from the vantage point of some of these people, the difference between your lifestyle and Mukesh Ambani’s might be negligible.

A notable characteristic of our species is the inability of even generally well-meaning people to see how privileged or lucky they are compared to many others. And linked with this, a self-absorption that leads to the inference of general lessons from our own very specific experiences. These traits show up in many general contexts, of course. (Feminists have long been subjected to casual, irresponsible remarks about feminism being too shrill, angry or exaggerated because, you know, things aren’t as bad as they are made out to be – and such assertions come not just from men but also from privileged women who don’t recognize the long and complex history of the movement and how they have benefited from it.) But they seem to come snarling to the surface in extraordinary situations like the current one.

It’s too easy now to cross a line from being happy for ourselves to being unthinkingly callous about others. Take a tweet from a journalist-columnist a few days ago, about how the bank she happened to go to in a certain colony at a certain time was well-managed and her work got done quickly. Up to this point, no problem – she was simply sharing an experience – but this was then transformed into a general statement of How Things Are; “the crisis has passed”, she ended by saying. Well, no, it hasn’t for millions of people – and that’s the politest, mildest observation one can make at this point.

Yes, of course many of the severely affected people (definitely not all, but many) are finding ways of “getting by” for the time being: helping each other, extending credit, relying on trust and goodwill, using our ancient philosophy of jugaad. Many of them are also deeply conditioned with a fatalistic impulse that comes partly from religious faith, from ideas about today’s suffering being a necessary prelude to a better tomorrow (in this life or the next). But just because the worst-hit are putting on a brave face and using whatever tools are available to them doesn’t mean that others should pretend that “everything is okay” or that “these are only small sacrifices”, or that anyone who raises questions about the manner in which this whole thing has unfolded is a “Congress stooge” or a “presstitute”.

I’m not addressing the larger question of whether this was a good idea or not, and what it may or may not achieve for the country's long-term future – I’m no expert on the subject, and many people who are can’t seem to agree with each other about the details. (Plus, if I’m advocating introspection, I have to consider the possibility that my dislike for Modi and his party might taint my views on just about anything this government does.) But there have been all-too-clear problems with the implementation. Even in an age where anyone with a computer or a smart-phone can express an opinion hastily, and 50 times a day, it should be possible to stop and consider that there may be some truth in the constant stream of reports about people suffering; that the trials of the underprivileged aren’t just the private fantasies of change-resistant libtards.

Perhaps a more realistic talisman would go something like this: each time you feel tempted to comment on an issue that you have been directly affected by – but which you know is ALSO affecting the lives of people who are much less fortunate – in any such case, before you make that sweeping statement, please count to twenty quietly; introspect a little, allow yourself to consider the possibility that there are things you have been shielded from, that the worst of what you have personally gone through is not necessarily the worst that anyone else might experience.

If you have spent a tough few hours in a bank queue (perhaps made a little less tough by the entertaining conversations around you, or the weather being relatively pleasant, or the option of playing a game on your smart-phone) and felt the relief of having seen some money at the end of it, along with the satisfaction of having contributed to the grand National Cause in some yet-to-be-fully-perceived way – even in the self-congratulatory euphoria of this moment, give yourself some time to consider those who may be facing greater hardships, and much more serious repercussions when they leave their work for days on end to stand in lines.

Consider that if you’re reading this post, that in itself is a guarantee that you are immeasurably better off than a very large number of people in this country. That from the vantage point of some of these people, the difference between your lifestyle and Mukesh Ambani’s might be negligible.

A notable characteristic of our species is the inability of even generally well-meaning people to see how privileged or lucky they are compared to many others. And linked with this, a self-absorption that leads to the inference of general lessons from our own very specific experiences. These traits show up in many general contexts, of course. (Feminists have long been subjected to casual, irresponsible remarks about feminism being too shrill, angry or exaggerated because, you know, things aren’t as bad as they are made out to be – and such assertions come not just from men but also from privileged women who don’t recognize the long and complex history of the movement and how they have benefited from it.) But they seem to come snarling to the surface in extraordinary situations like the current one.

It’s too easy now to cross a line from being happy for ourselves to being unthinkingly callous about others. Take a tweet from a journalist-columnist a few days ago, about how the bank she happened to go to in a certain colony at a certain time was well-managed and her work got done quickly. Up to this point, no problem – she was simply sharing an experience – but this was then transformed into a general statement of How Things Are; “the crisis has passed”, she ended by saying. Well, no, it hasn’t for millions of people – and that’s the politest, mildest observation one can make at this point.

Yes, of course many of the severely affected people (definitely not all, but many) are finding ways of “getting by” for the time being: helping each other, extending credit, relying on trust and goodwill, using our ancient philosophy of jugaad. Many of them are also deeply conditioned with a fatalistic impulse that comes partly from religious faith, from ideas about today’s suffering being a necessary prelude to a better tomorrow (in this life or the next). But just because the worst-hit are putting on a brave face and using whatever tools are available to them doesn’t mean that others should pretend that “everything is okay” or that “these are only small sacrifices”, or that anyone who raises questions about the manner in which this whole thing has unfolded is a “Congress stooge” or a “presstitute”.

I’m not addressing the larger question of whether this was a good idea or not, and what it may or may not achieve for the country's long-term future – I’m no expert on the subject, and many people who are can’t seem to agree with each other about the details. (Plus, if I’m advocating introspection, I have to consider the possibility that my dislike for Modi and his party might taint my views on just about anything this government does.) But there have been all-too-clear problems with the implementation. Even in an age where anyone with a computer or a smart-phone can express an opinion hastily, and 50 times a day, it should be possible to stop and consider that there may be some truth in the constant stream of reports about people suffering; that the trials of the underprivileged aren’t just the private fantasies of change-resistant libtards.

Published on November 19, 2016 05:52

November 18, 2016

The Champion of the World

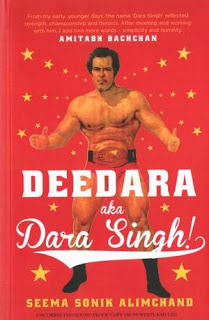

[Dara Singh's birth anniversary today. A little tribute in my latest Mint Lounge column]

---------------------

For the longest time, I didn’t know – or care – what his face looked like. All I saw was a pair of eyes rolling theatrically above a monkey snout.

And this despite the fact that I had long heard stories about Dara Singh from my grandmother and her friends: about his legendary prowess as a wrestler, about how handsome, rugged and yet gentlemanly he was when encountered outside a film studio or at the racecourse in 1960s Bombay.

But I was growing up in the mid-1980s, watching Ramanand Sagar’s TV Ramayana, in which Singh, close to sixty at the time, played Hanuman. So all-pervasive was that show’s influence in the single-channel era, as a child one couldn’t picture its actors outside a mythological context. I had watched Subhash Ghai’s Karma and Manmohan Desai’s Mard around the same time – films in which Singh, wearing his own face, had decent-sized parts – but if I ever thought of him, it was as Hanuman; my mind refused to create an image of his real visage.

I am thinking of Dara Singh now for two immediate reasons: one, it’s his birth anniversary this Saturday; and two, I just read a new book about him, Seema Sonik Alimchand’s Deedara a.k.a. Dara Singh! . But there’s another, broader reason too, involving the growing nationalistic discourse we see around us today, and how that discourse has become closely tied to a Hindutva revival. Today the very name “Dara Singh” raises conflicting feelings in me. On one hand, I picture the gentle giant in likable supporting parts in films like Mera Naam Joker and Anand. On the other, there is the link with hardline religiosity – via the unquestioning devotion of Hanuman the ultimate bhakt, precursor of some of today’s tweeting hordes, tearing his chest asunder to reveal an image of his God residing in his heart.

I am thinking of Dara Singh now for two immediate reasons: one, it’s his birth anniversary this Saturday; and two, I just read a new book about him, Seema Sonik Alimchand’s Deedara a.k.a. Dara Singh! . But there’s another, broader reason too, involving the growing nationalistic discourse we see around us today, and how that discourse has become closely tied to a Hindutva revival. Today the very name “Dara Singh” raises conflicting feelings in me. On one hand, I picture the gentle giant in likable supporting parts in films like Mera Naam Joker and Anand. On the other, there is the link with hardline religiosity – via the unquestioning devotion of Hanuman the ultimate bhakt, precursor of some of today’s tweeting hordes, tearing his chest asunder to reveal an image of his God residing in his heart.

There are also associations with a certain sort of Jat machismo, which I became wary of early in my life, having seen a number of hearty Punjabi relatives: sweetly boisterous people in most everyday contexts but containing a capacity for anger and violence that came to the surface when, for instance, the subject of Partition arose and there were dark murmurings about “the Mohammedans”; or a wave of pride sweeping across a room when an ancient uncle boasted that in 1947 he had helped load three trains with Muslim corpses and send them to Pakistan.

How could one not feel ambivalent about Dara Singh, given that it is from these same admiring relatives that I used to hear stories about this “invincible” man and his undefeated record. One thinks then about the subtexts of those wrestling bouts of the 50s and 60s. In a wonderful fanboy piece about Singh, first published in the Hindustan Times Brunch, Vir Sanghvi noted that the wrestling matches he watched as a boy weren’t real sport so much as carefully scripted morality plays, “a sort of Ram Leela in swimming trunks” – and that Singh was the Indian superhero who was called on to defeat the evil, racist gora. It goes some way towards explaining the roles he would later play, first in B-movies as our Steve Reeves, then in mythologicals.

But this is also why reading the new book was a revelation in some ways. I don’t want to over-stress the merits of Deedara a.k.a. Dara Singh! – it is hagiographical in places; it was written not just with the cooperation and approval of Dara Singh’s family but draws strongly on his memoir Meri Aatmakatha; you don’t want to take everything in it at face value. For instance, the author is tactfully compliant and unquestioning when it comes to such subjects as the validity of Singh’s status as “world champion” in a sport that was never really regulated; she simply gushes on about his many victories over famous opponents like King Kong.

But there are interesting things in the book – among them, a sense of personal growth, which comes through best in the passages that don’t present Singh in the best light. A story about how a young Dara, finding himself in tough straits, tries his hand at petty theft, and even gets a sense of power and fulfilment from it, but repents after one of his victims gets into trouble. The long journey of a man who was once a benevolent paternalist, telling his new bride who wanted to continue her education, “No wife of mine will work”, but who decades later watched with a mix of pride and bemusement as his eldest daughter began working as a flight attendant with an American airline.

Here is the actor who specialized in playing mythological characters, symbols of pride and inspiration for a religion; and yet – I was startled to learn this – Singh was, according to his family, an agnostic who recognized the important role played by religion in Indian society but himself believed that “you have to do things yourself. There is no God up there who will do it for you”. I have a feeling he wouldn’t be pleased about some of the jingoism that passes in the name of religion these days.

Here is the actor who specialized in playing mythological characters, symbols of pride and inspiration for a religion; and yet – I was startled to learn this – Singh was, according to his family, an agnostic who recognized the important role played by religion in Indian society but himself believed that “you have to do things yourself. There is no God up there who will do it for you”. I have a feeling he wouldn’t be pleased about some of the jingoism that passes in the name of religion these days.

Those of us who are proud of having a liberal or progressive sensibility are sometimes too quick to congratulate ourselves: we overlook the ways in which our upbringing and circumstances were conducive to the early seeding of these qualities; and we undervalue the struggles of people who were born in more restrictive, conservative settings, and who had to feel their way around – make mistakes, then introspect – before grasping the real meaning of concepts like equality and freedom of expression. The Dara Singh story is about a man who grew to contain multitudes, which is more inspirational than any narrative about a beefy pehelwan proving Indian superiority by strong-arming international opponents in rigged matches.

---------------------

For the longest time, I didn’t know – or care – what his face looked like. All I saw was a pair of eyes rolling theatrically above a monkey snout.

And this despite the fact that I had long heard stories about Dara Singh from my grandmother and her friends: about his legendary prowess as a wrestler, about how handsome, rugged and yet gentlemanly he was when encountered outside a film studio or at the racecourse in 1960s Bombay.

But I was growing up in the mid-1980s, watching Ramanand Sagar’s TV Ramayana, in which Singh, close to sixty at the time, played Hanuman. So all-pervasive was that show’s influence in the single-channel era, as a child one couldn’t picture its actors outside a mythological context. I had watched Subhash Ghai’s Karma and Manmohan Desai’s Mard around the same time – films in which Singh, wearing his own face, had decent-sized parts – but if I ever thought of him, it was as Hanuman; my mind refused to create an image of his real visage.

I am thinking of Dara Singh now for two immediate reasons: one, it’s his birth anniversary this Saturday; and two, I just read a new book about him, Seema Sonik Alimchand’s Deedara a.k.a. Dara Singh! . But there’s another, broader reason too, involving the growing nationalistic discourse we see around us today, and how that discourse has become closely tied to a Hindutva revival. Today the very name “Dara Singh” raises conflicting feelings in me. On one hand, I picture the gentle giant in likable supporting parts in films like Mera Naam Joker and Anand. On the other, there is the link with hardline religiosity – via the unquestioning devotion of Hanuman the ultimate bhakt, precursor of some of today’s tweeting hordes, tearing his chest asunder to reveal an image of his God residing in his heart.

I am thinking of Dara Singh now for two immediate reasons: one, it’s his birth anniversary this Saturday; and two, I just read a new book about him, Seema Sonik Alimchand’s Deedara a.k.a. Dara Singh! . But there’s another, broader reason too, involving the growing nationalistic discourse we see around us today, and how that discourse has become closely tied to a Hindutva revival. Today the very name “Dara Singh” raises conflicting feelings in me. On one hand, I picture the gentle giant in likable supporting parts in films like Mera Naam Joker and Anand. On the other, there is the link with hardline religiosity – via the unquestioning devotion of Hanuman the ultimate bhakt, precursor of some of today’s tweeting hordes, tearing his chest asunder to reveal an image of his God residing in his heart. There are also associations with a certain sort of Jat machismo, which I became wary of early in my life, having seen a number of hearty Punjabi relatives: sweetly boisterous people in most everyday contexts but containing a capacity for anger and violence that came to the surface when, for instance, the subject of Partition arose and there were dark murmurings about “the Mohammedans”; or a wave of pride sweeping across a room when an ancient uncle boasted that in 1947 he had helped load three trains with Muslim corpses and send them to Pakistan.

How could one not feel ambivalent about Dara Singh, given that it is from these same admiring relatives that I used to hear stories about this “invincible” man and his undefeated record. One thinks then about the subtexts of those wrestling bouts of the 50s and 60s. In a wonderful fanboy piece about Singh, first published in the Hindustan Times Brunch, Vir Sanghvi noted that the wrestling matches he watched as a boy weren’t real sport so much as carefully scripted morality plays, “a sort of Ram Leela in swimming trunks” – and that Singh was the Indian superhero who was called on to defeat the evil, racist gora. It goes some way towards explaining the roles he would later play, first in B-movies as our Steve Reeves, then in mythologicals.

But this is also why reading the new book was a revelation in some ways. I don’t want to over-stress the merits of Deedara a.k.a. Dara Singh! – it is hagiographical in places; it was written not just with the cooperation and approval of Dara Singh’s family but draws strongly on his memoir Meri Aatmakatha; you don’t want to take everything in it at face value. For instance, the author is tactfully compliant and unquestioning when it comes to such subjects as the validity of Singh’s status as “world champion” in a sport that was never really regulated; she simply gushes on about his many victories over famous opponents like King Kong.

But there are interesting things in the book – among them, a sense of personal growth, which comes through best in the passages that don’t present Singh in the best light. A story about how a young Dara, finding himself in tough straits, tries his hand at petty theft, and even gets a sense of power and fulfilment from it, but repents after one of his victims gets into trouble. The long journey of a man who was once a benevolent paternalist, telling his new bride who wanted to continue her education, “No wife of mine will work”, but who decades later watched with a mix of pride and bemusement as his eldest daughter began working as a flight attendant with an American airline.

Here is the actor who specialized in playing mythological characters, symbols of pride and inspiration for a religion; and yet – I was startled to learn this – Singh was, according to his family, an agnostic who recognized the important role played by religion in Indian society but himself believed that “you have to do things yourself. There is no God up there who will do it for you”. I have a feeling he wouldn’t be pleased about some of the jingoism that passes in the name of religion these days.

Here is the actor who specialized in playing mythological characters, symbols of pride and inspiration for a religion; and yet – I was startled to learn this – Singh was, according to his family, an agnostic who recognized the important role played by religion in Indian society but himself believed that “you have to do things yourself. There is no God up there who will do it for you”. I have a feeling he wouldn’t be pleased about some of the jingoism that passes in the name of religion these days. Those of us who are proud of having a liberal or progressive sensibility are sometimes too quick to congratulate ourselves: we overlook the ways in which our upbringing and circumstances were conducive to the early seeding of these qualities; and we undervalue the struggles of people who were born in more restrictive, conservative settings, and who had to feel their way around – make mistakes, then introspect – before grasping the real meaning of concepts like equality and freedom of expression. The Dara Singh story is about a man who grew to contain multitudes, which is more inspirational than any narrative about a beefy pehelwan proving Indian superiority by strong-arming international opponents in rigged matches.

Published on November 18, 2016 17:29

November 17, 2016

Report from outside a bank: 'achha din' for an 'achha aadmi'

One of many life lessons learnt in bank queues over the past few days: if you want your work done quickly, try wearing the mask of a Samaritan-activist. Outside Kotak Mahindra in Saket yesterday, after an hour and a half of waiting in a line that was cheekily moving BACKWARDS instead of in the direction of the bank entrance, realization dawned that some people had left their names and numbers with the guard and were now being admitted into the premises despite having just shown up and not having stood in line at all.

A gregarious middle-aged man decided enough was enough. He left our “official” line, pushed his way to the door and began an impassioned speech about the injustice being done to those of us who had been waiting for hours, especially – pointing at the women’s line – “yeh bechari ladies, jo kab se yahaan khadi hui hain”. Inviting the rest of us to join him in his tirade, emboldening even the quietest of the women to yell at the guards, he speculated that the people being let in were relatives of the bank staff; that he could see them having tea inside, chatting away and taking 20 minutes over what should have been a 5-minute transaction (this could well be true); that we should call “the media and 100”. He loudly and ostentatiously made a call to someone from a TV channel himself, then continued complaining for the next 10 minutes – never about his own predicament, only about how much the rest of us were suffering. And he banged on the shutters. A guard warned him that the bank officials would call the police and have him taken away. “Haan haan, bulaa do!” he shouted. “Jail mein daal do mujhe.”

After some more of this, the door opened slightly, a voice said “Uncle, aap andar aa jaayiye”, and that was the last we saw of Uncle until 10 minutes later when he emerged with a smile on his face and his bag looking much bulkier than it had earlier been. Some of the people around him made angry sounds about how he had got his own work done despite having been much further back in the line, and what about the rest of us, why didn’t he get the staff to let the ladies in as well etc. “Kya bol rahe hain aap log?” he said, making his way through the crowd and towards freedom, “If the police had come and arrested me, would all of you have followed me to jail as well?”

A gregarious middle-aged man decided enough was enough. He left our “official” line, pushed his way to the door and began an impassioned speech about the injustice being done to those of us who had been waiting for hours, especially – pointing at the women’s line – “yeh bechari ladies, jo kab se yahaan khadi hui hain”. Inviting the rest of us to join him in his tirade, emboldening even the quietest of the women to yell at the guards, he speculated that the people being let in were relatives of the bank staff; that he could see them having tea inside, chatting away and taking 20 minutes over what should have been a 5-minute transaction (this could well be true); that we should call “the media and 100”. He loudly and ostentatiously made a call to someone from a TV channel himself, then continued complaining for the next 10 minutes – never about his own predicament, only about how much the rest of us were suffering. And he banged on the shutters. A guard warned him that the bank officials would call the police and have him taken away. “Haan haan, bulaa do!” he shouted. “Jail mein daal do mujhe.”

After some more of this, the door opened slightly, a voice said “Uncle, aap andar aa jaayiye”, and that was the last we saw of Uncle until 10 minutes later when he emerged with a smile on his face and his bag looking much bulkier than it had earlier been. Some of the people around him made angry sounds about how he had got his own work done despite having been much further back in the line, and what about the rest of us, why didn’t he get the staff to let the ladies in as well etc. “Kya bol rahe hain aap log?” he said, making his way through the crowd and towards freedom, “If the police had come and arrested me, would all of you have followed me to jail as well?”

Published on November 17, 2016 23:12

November 15, 2016

The end of Federer-Nadal? Reflections on a golden age in men's tennis

[Did this summing-up piece for BusinessLine's BLink]

In the same way that many young film buffs are patronizing towards old movies – seeing them as creaky, mannered or generally incapable of matching the technical advancements and the edgier screenwriting of today – there is a species of sports fan who always trumpets the glories of the present over the past. Back in my cricket-watching days, when the Sachin Tendulkar-Don Bradman comparisons had just begun, a friend casually dismissed the idea that the Australian legend’s unbelievable batting average meant anything important. “The game was clubby and undemanding in Bradman’s time,” he said, with all the sagacity of someone who had studied cricketing history in depth (he hadn’t). Making vague sounds about the 1932 Bodyline attack “solving” Bradman, he neglected to acknowledge that the Don still averaged as much in that unsuccessful series as most top batsmen do overall, and that he faced the short-ball barrage without a helmet.

For such fans, modern athletes are by definition superior, and great contemporary matches are spectacles the likes of which have never before been seen. These perceptions are encouraged by a sports media that – faced with strong competition for eyeballs and click-throughs – never misses a chance to bulk up a current player’s or match’s credentials for “greatest of all time” (GOAT). In the process, while some statistics are overstated, some historical details are overlooked: for instance, that batsmen once played on uncovered, “sticky” wickets; or that tennis players had more demanding schedules 60 years ago, with far less cushy modes of travel and less time to get acclimatized to a variety of conditions.

Which is a roundabout way of saying that even someone who has been enthralled by men’s tennis over the past decade should be a little wary of the more dramatic narratives surrounding it. And yes, this comes from a card-carrying fan: since early 2006, I have followed the sport week in and out, tracking even the first-round matches of ATP-500 tournaments. Being a Rafael Nadal KAD (Kool-Aid Drinker, a sometimes disparaging term used for a huge fan of a player or team) during this period hasn’t stopped me from admiring the achievements of Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic, Andy Murray and many others near the sport’s top tiers. There is little doubt that this era – which has also coincided with improvements in TV coverage and other viewing options, including sophisticated live streams – has been a stirring, special one.

Which is a roundabout way of saying that even someone who has been enthralled by men’s tennis over the past decade should be a little wary of the more dramatic narratives surrounding it. And yes, this comes from a card-carrying fan: since early 2006, I have followed the sport week in and out, tracking even the first-round matches of ATP-500 tournaments. Being a Rafael Nadal KAD (Kool-Aid Drinker, a sometimes disparaging term used for a huge fan of a player or team) during this period hasn’t stopped me from admiring the achievements of Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic, Andy Murray and many others near the sport’s top tiers. There is little doubt that this era – which has also coincided with improvements in TV coverage and other viewing options, including sophisticated live streams – has been a stirring, special one.

What I’m not so sure about is whether it is the Golden Age of Golden Ages that it is sometimes made out to be, by fans crowding tennis websites, as well as by journalists. That Federer, Nadal and Djokovic are great champions is indisputable; but it is not uncommon now to find arguments that they are THE best male players ever (the order varies, depending on who you ask), a position that casually undermines the achievements of past greats such as Pancho Gonzalez, Ken Rosewall, Rod Laver and Bjorn Borg. Here is current-day chauvinism hard at work.

Still, now is a good time to attempt a summing up: Federer and Nadal have both fallen out of the top 5 for the first time since June 2005, and given a combination of age, on-court mileage and injuries, there is no guarantee that either of them will return to the summit. Meanwhile, in another recent twist, Djokovic – who went from being solid supporting player to becoming an all-conquering champion in his own right – has shown low motivation and suffered a minor decline after completing his Career Slam at the French Open in June. Both he and Andy Murray – who has just reached the number one position for the first time, after years of playing in the shadow of the other three – will turn 30 next May; very few male players have won multiple Slams past that age. It certainly feels like the age of the Big Four is winding up.

******

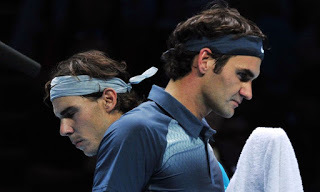

In discussing what was so special about the last 10 years, one has to begin with Federer-Nadal, their names now linked together for all time. It wasn’t a very close rivalry, especially after Rafa rose from being a clay-court giant to all-surface excellence by 2008-09: his left-handed, top-spin-heavy game being laboratory-made to break down Federer’s one-handed backhand, the head-to-head between them is 23-11 in Nadal’s favour (and an even more lopsided 9-2 in Grand Slam matches). But the duopoly exercised by these men between 2005-2010 – and the best of their matches, such as the 2006 Rome Masters final and the 2007 and 2008 Wimbledon finals – left a huge impact on the sport, improving TV ratings and motivating other players, Djokovic, Murray and Stan Wawrinka among them, to raise their own games.

Sports narratives have always thrived on contrast, and here was an irresistible one, even if it was founded on clichés about style and aesthetics. Federer-Nadal was seen as a face-off between an elegant, versatile, preternaturally gifted champion who was to the manor born versus a brutish young caveman who slogged his way to the top through sheer grit and a repetitive game. This was simplistic and unfair to both players, implying as it did that Federer didn’t work extremely hard to get where he did, and that Nadal didn’t have much natural talent; and also neglecting basic facts, such as that the Spanish “beast” comes from an old-rich background and lives a mollycoddled life in a family mansion. But the narrative made for exciting theatre and brought more viewers into the sport, both to watch and to have impassioned online arguments about the perceived characteristics of their favourite player vis-à-vis his nemesis.

Sports narratives have always thrived on contrast, and here was an irresistible one, even if it was founded on clichés about style and aesthetics. Federer-Nadal was seen as a face-off between an elegant, versatile, preternaturally gifted champion who was to the manor born versus a brutish young caveman who slogged his way to the top through sheer grit and a repetitive game. This was simplistic and unfair to both players, implying as it did that Federer didn’t work extremely hard to get where he did, and that Nadal didn’t have much natural talent; and also neglecting basic facts, such as that the Spanish “beast” comes from an old-rich background and lives a mollycoddled life in a family mansion. But the narrative made for exciting theatre and brought more viewers into the sport, both to watch and to have impassioned online arguments about the perceived characteristics of their favourite player vis-à-vis his nemesis.

The rivalry is still seen as the high point of men’s tennis over this period, even though it was followed by two others – between each of these players and the rapidly ascending Djokovic – that were more competitive. (The Djokovic-Federer head-to-head is currently 23-22, while Djokovic-Nadal is 26-23; in both cases, the younger man took the lead after trailing the more established player for years.) In fact, Djokovic and Nadal have played each other in the finals of all four Slams – something Federer and Nadal didn’t do – with more evenly matched results.

Part of the reason why the matches involving only Nadal, Djokovic and Murray didn’t capture the imagination in the same way as Federer-Nadal had was that there wasn’t enough variety involved. Unlike Federer – whose primary game was a crisp, attacking one aimed at finishing points quickly – the other three are all, to varying degrees, baseline players with extraordinary defence-to-offence skills. If the much-feted 2008 Wimbledon final between Federer and Nadal was hailed for its contrast in styles, the epic 2012 Australian Open final between Nadal and Djokovic was an intense, sometimes exhausting exercise in watching two players cut from the same cloth finding mad angles from every corner of the court.

This sort of play – often described by vexed Federer fans as boring and unappealing to the eye – has been on prominent display recently, in Slam finals between Djokovic and Murray. And to understand the nature of this game, and the era as a whole, one must factor in something that had a huge impact on the sport: the slowing down of playing surfaces around the world.

This sort of play – often described by vexed Federer fans as boring and unappealing to the eye – has been on prominent display recently, in Slam finals between Djokovic and Murray. And to understand the nature of this game, and the era as a whole, one must factor in something that had a huge impact on the sport: the slowing down of playing surfaces around the world.

Around a decade and a half ago, the International Tennis Federation (ITF) responded to the charge that too many matches were “serve-fests”, with not enough long rallies, by making changes to the faster courts: Wimbledon used a variety of rye-grass that made the surface dry (especially after the first few days of play) and caused the ball to bounce higher and slower than before; the US Open added more silica sand to its acrylic; other tournaments followed suit. Some of the most notable characteristics of the modern sport – including all those eye-popping rallies with seemingly impossible-to-retrieve balls being put back into play – have been a direct result of this slowing down.

This homogenization has also aided the all-surface success of the top players. Between 2009 and 2016, Federer, Nadal and Djokovic each completed the Career Slam – winning all four majors at least once – which used to be among the rarest of tennis’s achievements. Many excitable fans regard this as further proof that we are in an age of unparalleled riches; the more circumspect point out that when most surfaces play similarly it becomes easier for the leading players to do well round the year. When Bjorn Borg won Roland Garros and Wimbledon back to back thrice between 1978 and 1980, the two tournaments – one on slow clay, the other on genuinely fast-playing grass – involved very different skill-sets, and different sorts of players tended to excel at each; this was what made Borg’s achievement so remarkable, and it also helps explain why someone as good as Sampras reached the French Open semi-final only once, though he won Wimbledon seven times. When Federer and Nadal achieved this same “Channel Slam” in the 2000s, the surfaces were more similar. Even during one of his great career years, 2010, when he eventually won Wimbledon, Nadal struggled in the first week – when the grass is fresher, moister and plays more like it did in the past – being taken to five sets by the much lower-ranked opponents Robin Haase and Philipp Petzschner.

******

But every sport goes through cyclical phases; if the last decade was marked by slowing down, there is now, inevitably, talk of speeding up – and not necessarily by changing surfaces again. Recent exhibition matches, some featuring top players like Federer, Murray and Lleyton Hewitt, have experimented with new scoring systems, such as one where you need a minimum of four games (rather than six) to win a set, a tie-break is won by the player who reaches five points (instead of seven) with a difference of two, and there are no “advantage” points (at 40-40 or deuce, whoever wins the next point wins the game).

If any of these ideas are implemented in official matches – and it will probably take a while for that to happen – we might, with hindsight, view the past decade as the final showcase for the truly epic match: the Slam final or semi-final that stretched over four or five hours. It would also be a reminder that tennis needs to be jazzed up for the young, impatient viewer. If some people viewed the Sampras-Ivanisevic serve-and-volley points of the 1990s as one-dimensional, then long-drawn-out battles of attrition can be just as dull; perhaps the sport needs a middle ground.

What else does the future have in store? If Djokovic and Murray start to wind down soon, we could be in for a cooling-off period where the next dominant champion is hard to identify – something like the sport saw in 2002-03, when the ball was in the air between Hewitt, Federer, Andy Roddick, Marat Safin, Juan Carlos Ferrero and the aging Andre Agassi.

Some young players who showed terrific promise a few years ago – Grigor Dimitrov, Kei Nishikori, Milos Raonic among them – haven’t quite been able to break the Big Four stranglehold. But there is a generation just behind them, which has made big strides this year. There is the Australian Nick Kyrgios, supremely talented but already with a well-earned reputation as a bad boy, churlish on the court, capable of tanking a match if he doesn’t feel too motivated on the day. There is the much steadier Austrian, Dominic Thiem, who has had a terrific 2016 – even making it to the prestigious year-end championships featuring the top eight players – but who may also have over-played and tired himself out. The German teenager Alexander Zverev, who already has some impressive wins against a number of top 10 players – including Federer – to his credit. The Frenchman Lucas Pouille who beat Nadal at the US Open this year, and shortly afterwards won his first ATP tournament in Metz.

It’s hard at the moment to imagine that any of these players could forge rivalries as dramatic as the ones involving Federer, Nadal and Djokovic, but sports-followers must always expect to be surprised. When Sampras retired with a record 14 Slams as recently as 2002, no one could have thought that three different players would overtake or threaten that record within the next 15 years. When Djokovic was world number one with a buffer of several thousand ranking points over his nearest competitor in June, it didn’t seem conceivable that he could lose the top position this year. Perhaps, a couple of years from now, we could see finals that are high-octane and intensely fought, but still take up only 80 minutes of our time and have scorecards that read 4-2, 4-2, 4-5(3), 4-2 – at which point even those who once complained about the length of Nadal-Djokovic matches might get dewy-eyed about the good old days.

[A few earlier tennis posts are here – among them, this long piece about narrative-making in sport]

In the same way that many young film buffs are patronizing towards old movies – seeing them as creaky, mannered or generally incapable of matching the technical advancements and the edgier screenwriting of today – there is a species of sports fan who always trumpets the glories of the present over the past. Back in my cricket-watching days, when the Sachin Tendulkar-Don Bradman comparisons had just begun, a friend casually dismissed the idea that the Australian legend’s unbelievable batting average meant anything important. “The game was clubby and undemanding in Bradman’s time,” he said, with all the sagacity of someone who had studied cricketing history in depth (he hadn’t). Making vague sounds about the 1932 Bodyline attack “solving” Bradman, he neglected to acknowledge that the Don still averaged as much in that unsuccessful series as most top batsmen do overall, and that he faced the short-ball barrage without a helmet.

For such fans, modern athletes are by definition superior, and great contemporary matches are spectacles the likes of which have never before been seen. These perceptions are encouraged by a sports media that – faced with strong competition for eyeballs and click-throughs – never misses a chance to bulk up a current player’s or match’s credentials for “greatest of all time” (GOAT). In the process, while some statistics are overstated, some historical details are overlooked: for instance, that batsmen once played on uncovered, “sticky” wickets; or that tennis players had more demanding schedules 60 years ago, with far less cushy modes of travel and less time to get acclimatized to a variety of conditions.

Which is a roundabout way of saying that even someone who has been enthralled by men’s tennis over the past decade should be a little wary of the more dramatic narratives surrounding it. And yes, this comes from a card-carrying fan: since early 2006, I have followed the sport week in and out, tracking even the first-round matches of ATP-500 tournaments. Being a Rafael Nadal KAD (Kool-Aid Drinker, a sometimes disparaging term used for a huge fan of a player or team) during this period hasn’t stopped me from admiring the achievements of Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic, Andy Murray and many others near the sport’s top tiers. There is little doubt that this era – which has also coincided with improvements in TV coverage and other viewing options, including sophisticated live streams – has been a stirring, special one.

Which is a roundabout way of saying that even someone who has been enthralled by men’s tennis over the past decade should be a little wary of the more dramatic narratives surrounding it. And yes, this comes from a card-carrying fan: since early 2006, I have followed the sport week in and out, tracking even the first-round matches of ATP-500 tournaments. Being a Rafael Nadal KAD (Kool-Aid Drinker, a sometimes disparaging term used for a huge fan of a player or team) during this period hasn’t stopped me from admiring the achievements of Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic, Andy Murray and many others near the sport’s top tiers. There is little doubt that this era – which has also coincided with improvements in TV coverage and other viewing options, including sophisticated live streams – has been a stirring, special one. What I’m not so sure about is whether it is the Golden Age of Golden Ages that it is sometimes made out to be, by fans crowding tennis websites, as well as by journalists. That Federer, Nadal and Djokovic are great champions is indisputable; but it is not uncommon now to find arguments that they are THE best male players ever (the order varies, depending on who you ask), a position that casually undermines the achievements of past greats such as Pancho Gonzalez, Ken Rosewall, Rod Laver and Bjorn Borg. Here is current-day chauvinism hard at work.

Still, now is a good time to attempt a summing up: Federer and Nadal have both fallen out of the top 5 for the first time since June 2005, and given a combination of age, on-court mileage and injuries, there is no guarantee that either of them will return to the summit. Meanwhile, in another recent twist, Djokovic – who went from being solid supporting player to becoming an all-conquering champion in his own right – has shown low motivation and suffered a minor decline after completing his Career Slam at the French Open in June. Both he and Andy Murray – who has just reached the number one position for the first time, after years of playing in the shadow of the other three – will turn 30 next May; very few male players have won multiple Slams past that age. It certainly feels like the age of the Big Four is winding up.

******

In discussing what was so special about the last 10 years, one has to begin with Federer-Nadal, their names now linked together for all time. It wasn’t a very close rivalry, especially after Rafa rose from being a clay-court giant to all-surface excellence by 2008-09: his left-handed, top-spin-heavy game being laboratory-made to break down Federer’s one-handed backhand, the head-to-head between them is 23-11 in Nadal’s favour (and an even more lopsided 9-2 in Grand Slam matches). But the duopoly exercised by these men between 2005-2010 – and the best of their matches, such as the 2006 Rome Masters final and the 2007 and 2008 Wimbledon finals – left a huge impact on the sport, improving TV ratings and motivating other players, Djokovic, Murray and Stan Wawrinka among them, to raise their own games.

Sports narratives have always thrived on contrast, and here was an irresistible one, even if it was founded on clichés about style and aesthetics. Federer-Nadal was seen as a face-off between an elegant, versatile, preternaturally gifted champion who was to the manor born versus a brutish young caveman who slogged his way to the top through sheer grit and a repetitive game. This was simplistic and unfair to both players, implying as it did that Federer didn’t work extremely hard to get where he did, and that Nadal didn’t have much natural talent; and also neglecting basic facts, such as that the Spanish “beast” comes from an old-rich background and lives a mollycoddled life in a family mansion. But the narrative made for exciting theatre and brought more viewers into the sport, both to watch and to have impassioned online arguments about the perceived characteristics of their favourite player vis-à-vis his nemesis.

Sports narratives have always thrived on contrast, and here was an irresistible one, even if it was founded on clichés about style and aesthetics. Federer-Nadal was seen as a face-off between an elegant, versatile, preternaturally gifted champion who was to the manor born versus a brutish young caveman who slogged his way to the top through sheer grit and a repetitive game. This was simplistic and unfair to both players, implying as it did that Federer didn’t work extremely hard to get where he did, and that Nadal didn’t have much natural talent; and also neglecting basic facts, such as that the Spanish “beast” comes from an old-rich background and lives a mollycoddled life in a family mansion. But the narrative made for exciting theatre and brought more viewers into the sport, both to watch and to have impassioned online arguments about the perceived characteristics of their favourite player vis-à-vis his nemesis. The rivalry is still seen as the high point of men’s tennis over this period, even though it was followed by two others – between each of these players and the rapidly ascending Djokovic – that were more competitive. (The Djokovic-Federer head-to-head is currently 23-22, while Djokovic-Nadal is 26-23; in both cases, the younger man took the lead after trailing the more established player for years.) In fact, Djokovic and Nadal have played each other in the finals of all four Slams – something Federer and Nadal didn’t do – with more evenly matched results.

Part of the reason why the matches involving only Nadal, Djokovic and Murray didn’t capture the imagination in the same way as Federer-Nadal had was that there wasn’t enough variety involved. Unlike Federer – whose primary game was a crisp, attacking one aimed at finishing points quickly – the other three are all, to varying degrees, baseline players with extraordinary defence-to-offence skills. If the much-feted 2008 Wimbledon final between Federer and Nadal was hailed for its contrast in styles, the epic 2012 Australian Open final between Nadal and Djokovic was an intense, sometimes exhausting exercise in watching two players cut from the same cloth finding mad angles from every corner of the court.

This sort of play – often described by vexed Federer fans as boring and unappealing to the eye – has been on prominent display recently, in Slam finals between Djokovic and Murray. And to understand the nature of this game, and the era as a whole, one must factor in something that had a huge impact on the sport: the slowing down of playing surfaces around the world.

This sort of play – often described by vexed Federer fans as boring and unappealing to the eye – has been on prominent display recently, in Slam finals between Djokovic and Murray. And to understand the nature of this game, and the era as a whole, one must factor in something that had a huge impact on the sport: the slowing down of playing surfaces around the world. Around a decade and a half ago, the International Tennis Federation (ITF) responded to the charge that too many matches were “serve-fests”, with not enough long rallies, by making changes to the faster courts: Wimbledon used a variety of rye-grass that made the surface dry (especially after the first few days of play) and caused the ball to bounce higher and slower than before; the US Open added more silica sand to its acrylic; other tournaments followed suit. Some of the most notable characteristics of the modern sport – including all those eye-popping rallies with seemingly impossible-to-retrieve balls being put back into play – have been a direct result of this slowing down.

This homogenization has also aided the all-surface success of the top players. Between 2009 and 2016, Federer, Nadal and Djokovic each completed the Career Slam – winning all four majors at least once – which used to be among the rarest of tennis’s achievements. Many excitable fans regard this as further proof that we are in an age of unparalleled riches; the more circumspect point out that when most surfaces play similarly it becomes easier for the leading players to do well round the year. When Bjorn Borg won Roland Garros and Wimbledon back to back thrice between 1978 and 1980, the two tournaments – one on slow clay, the other on genuinely fast-playing grass – involved very different skill-sets, and different sorts of players tended to excel at each; this was what made Borg’s achievement so remarkable, and it also helps explain why someone as good as Sampras reached the French Open semi-final only once, though he won Wimbledon seven times. When Federer and Nadal achieved this same “Channel Slam” in the 2000s, the surfaces were more similar. Even during one of his great career years, 2010, when he eventually won Wimbledon, Nadal struggled in the first week – when the grass is fresher, moister and plays more like it did in the past – being taken to five sets by the much lower-ranked opponents Robin Haase and Philipp Petzschner.

******

But every sport goes through cyclical phases; if the last decade was marked by slowing down, there is now, inevitably, talk of speeding up – and not necessarily by changing surfaces again. Recent exhibition matches, some featuring top players like Federer, Murray and Lleyton Hewitt, have experimented with new scoring systems, such as one where you need a minimum of four games (rather than six) to win a set, a tie-break is won by the player who reaches five points (instead of seven) with a difference of two, and there are no “advantage” points (at 40-40 or deuce, whoever wins the next point wins the game).

If any of these ideas are implemented in official matches – and it will probably take a while for that to happen – we might, with hindsight, view the past decade as the final showcase for the truly epic match: the Slam final or semi-final that stretched over four or five hours. It would also be a reminder that tennis needs to be jazzed up for the young, impatient viewer. If some people viewed the Sampras-Ivanisevic serve-and-volley points of the 1990s as one-dimensional, then long-drawn-out battles of attrition can be just as dull; perhaps the sport needs a middle ground.

What else does the future have in store? If Djokovic and Murray start to wind down soon, we could be in for a cooling-off period where the next dominant champion is hard to identify – something like the sport saw in 2002-03, when the ball was in the air between Hewitt, Federer, Andy Roddick, Marat Safin, Juan Carlos Ferrero and the aging Andre Agassi.

Some young players who showed terrific promise a few years ago – Grigor Dimitrov, Kei Nishikori, Milos Raonic among them – haven’t quite been able to break the Big Four stranglehold. But there is a generation just behind them, which has made big strides this year. There is the Australian Nick Kyrgios, supremely talented but already with a well-earned reputation as a bad boy, churlish on the court, capable of tanking a match if he doesn’t feel too motivated on the day. There is the much steadier Austrian, Dominic Thiem, who has had a terrific 2016 – even making it to the prestigious year-end championships featuring the top eight players – but who may also have over-played and tired himself out. The German teenager Alexander Zverev, who already has some impressive wins against a number of top 10 players – including Federer – to his credit. The Frenchman Lucas Pouille who beat Nadal at the US Open this year, and shortly afterwards won his first ATP tournament in Metz.

It’s hard at the moment to imagine that any of these players could forge rivalries as dramatic as the ones involving Federer, Nadal and Djokovic, but sports-followers must always expect to be surprised. When Sampras retired with a record 14 Slams as recently as 2002, no one could have thought that three different players would overtake or threaten that record within the next 15 years. When Djokovic was world number one with a buffer of several thousand ranking points over his nearest competitor in June, it didn’t seem conceivable that he could lose the top position this year. Perhaps, a couple of years from now, we could see finals that are high-octane and intensely fought, but still take up only 80 minutes of our time and have scorecards that read 4-2, 4-2, 4-5(3), 4-2 – at which point even those who once complained about the length of Nadal-Djokovic matches might get dewy-eyed about the good old days.

[A few earlier tennis posts are here – among them, this long piece about narrative-making in sport]

Published on November 15, 2016 18:28

November 14, 2016

The solitary and the communal viewer

[Did this piece for a Mint Lounge special about “120 years of watching movies in India”]

------------------------------

Two movie-watching vignettes, a decade and a half apart:

It’s 1990 or 1991, I’m a young teen standing a few feet outside the room where my mother and nani are watching a film on our video-cassette player; peering in unobtrusively so they don’t ask me to come in and sit down with them. This isn’t a single incident, it is a composite of many. It could be that I am embarrassed by the tackier scenes – or the raunchier ones like the Ajooba song where Amitabh Bachchan and Rishi Kapoor, shrunk to finger size, cavort inside the blouses of their girlfriends – or maybe I just want to watch the film “alone”. Though I don’t know it yet, my childhood love affair with Hindi cinema is about to end.

Cut to 2005, and I’m watching Rohan Sippy’s Bluffmaster in a Noida hall with a girlfriend, soon to be my wife, in whose company I am finding my way back to Hindi films. We have just had a fight and it looks like the next two hours will be strained – I won’t say a word unless she speaks first, I have told myself sulkily as the screening begins – but around 45 minutes in we are both sufficiently engaged by the film’s pace, music and the likable performances, to begin whispering to each other. Bluffmaster is hardly likely to be remembered as one of the seminal achievements of its time, but in that situation, with the right company, it works.

Now that this memory montage has begun, other incidents unspool non-chronologically through my mind. With three friends, I’m watching Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot le Fou at the rundown Paras hall in South Delhi during a film festival. Godard’s experiments with cinematic form have long been subjects of wonder for us, and so, when the image on the screen shakes wildly and loses focus for a few seconds, even though we know this is a technical problem (one frequently experienced at this venue), the joke is inevitable. “What was JLG trying to say here?” one of us goes in a faux-pedantic tone. We conjecture. We crack up. An avant-garde director has been out-avant-garded by faulty projection.

A few seconds of frivolity enhanced that viewing, but at other times laughter is sacrilegious. Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo is playing in a small hall at the PVR Saket multiplex, part of a half-hearted (and short-lived) effort by the theatre to screen “international classics” once a week. Right film, poor print, wrong crowd. The seats immediately around me are empty, I made sure of that, but from two rows ahead issue the groans of young plebs who clearly equate the director’s name with “murder mystery”. “Hitchcock has lost it, man,” someone says as if speaking of a school pal.

Chewing glumly on stale popcorn, I flashback to a few years earlier when I’m viewing a restored Vertigo print in my room, letting the languid visuals, punctuated by slow dissolves and Bernard Herrmann’s music, wash over me. The quality of that experience is inseparable from the fact that I am alone.

Harrowing and invigorating things may happen in the same venue. Watching The Tin Drum in Siri Fort Auditorium on an uncomfortable seat, and with the stench of sweat in the air (not to mention a whispered “iss film mein SCENES hain, na?” from a hopeful patron of B-porn), does nothing to help me engage. But years later, in this very hall, elderly viewers burst into cheers when the young Dev Anand makes his appearance in the 1951 classic Baazi, and I am swept along by the worshipful tide; somehow the creaking seats and the bad print don’t matter so much.

******

These and so many other experiences were defined by the company I kept, or didn’t keep, while watching a film – and some of them cast a long shadow. Take those adolescent, from-outside-the-room viewings. Mainstream Hindi cinema circa 1989-91 was more chaff than wheat, but I wanted the option of enjoying even mediocre films without hearing family members snort “Kya bakwaas hai!” This sheepishness helped birth my career as a Solitary Watcher, which dovetailed with a growing interest in old Hollywood and “world cinema” – new windows that I discovered on my own – and led to a phasing out of other people from my viewing life. Through the 1990s, I was almost always watching films alone, on cassettes hired from local parlours or Embassy libraries, or during occasional film-festival jaunts.

These and so many other experiences were defined by the company I kept, or didn’t keep, while watching a film – and some of them cast a long shadow. Take those adolescent, from-outside-the-room viewings. Mainstream Hindi cinema circa 1989-91 was more chaff than wheat, but I wanted the option of enjoying even mediocre films without hearing family members snort “Kya bakwaas hai!” This sheepishness helped birth my career as a Solitary Watcher, which dovetailed with a growing interest in old Hollywood and “world cinema” – new windows that I discovered on my own – and led to a phasing out of other people from my viewing life. Through the 1990s, I was almost always watching films alone, on cassettes hired from local parlours or Embassy libraries, or during occasional film-festival jaunts.

There were stray moments that don’t fit into this arc: such as allowing myself to be taken to a Dilwale Dulhaniya le Jaayenge screening in 1995, and enjoying the film hugely. But it was only in the 2000s that I properly returned to communal viewing – and, not coincidentally, to a renewed engagement with Hindi cinema – in the company of my wife, and a few other friends, who were egalitarian viewers, capable of watching and having intense conversations about anything.

The internal divide continues, of course: here is the solitude-loving nerd who still loves watching DVDs alone, replaying a scene endlessly or pausing a film to make notes, and here is the more social animal who is stimulated by seeing a film with someone else, discussing afterwards, refining his own thoughts through conversation.

Many years after that disastrous Vertigo viewing at PVR, I read a Jim Emerson piece titled “Movies too personal to share with an audience”, which suggests that some films (Vertigo among them) are best seen alone rather than with company. That sounds right, given my own experience, but I’m wary about such a clearly spelled-out thesis. There are other intersecting considerations: the type of company matters, as does the mood you’re in on the day. Are you a professional critic with an urgent deadline? Are you showing someone a film for the first time (and playing mentor) or watching with a friend who insists on complete silence throughout?

You could make this broad statement: a larger-than-life Hindi film full of seeti-bajao moments – say, a Salman Khan blockbuster – works best with a crowd, while a less showy film is best seen alone. But I have had both rewarding and disappointing experiences that contradict this idea. For instance, it is possible to watch a particular film by yourself, and later with an audience, and to enjoy it both times – but to be stimulated by different things on each occasion. Watching Anand alone, I was stirred by Bachchan’s understated performance as the cynical doctor, and annoyed by Rajesh Khanna’s mannerism-laden inspirational hero; watching it with an audience in a setting that lent itself to the grand theatrical gesture, I changed my mind and saw Khanna as the film’s true star and energy-dispenser.

And there are the serendipitous moments, which no amount of theorizing can prepare you for: when, for instance, a roomful of strangers unites in solidarity not over something cherished like Dev Anand (or Inspirational Anand), but something execrable. Watching Ram Gopal Varma ki Aag, a terrible Sholay remake, should have been among my worst hall experiences. Instead it was marked by a wave of bonhomie: audience members guffawed each time a scene desecrated an iconic moment from the original. “Khota film donon taraf se khota hota hai,” someone hollered at the screen, a riff on one of Sholay’s most famous lines (Khota sikka toh dono taraf se khota hota hai”), and we all applauded.

If a great film can be underwhelming in the wrong company, a terrible film can become enjoyable with the right crowd. Perhaps what finicky movie buffs need is permanent access to a private screening room along with programming software that gauges our personality, pulse rate and frame of mind on a particular day and tells us exactly who we should take along for the ride. Perhaps that will be the next revolution in film-viewing.

[A related piece here: notes from the centenary film festival]

------------------------------

Two movie-watching vignettes, a decade and a half apart:

It’s 1990 or 1991, I’m a young teen standing a few feet outside the room where my mother and nani are watching a film on our video-cassette player; peering in unobtrusively so they don’t ask me to come in and sit down with them. This isn’t a single incident, it is a composite of many. It could be that I am embarrassed by the tackier scenes – or the raunchier ones like the Ajooba song where Amitabh Bachchan and Rishi Kapoor, shrunk to finger size, cavort inside the blouses of their girlfriends – or maybe I just want to watch the film “alone”. Though I don’t know it yet, my childhood love affair with Hindi cinema is about to end.

Cut to 2005, and I’m watching Rohan Sippy’s Bluffmaster in a Noida hall with a girlfriend, soon to be my wife, in whose company I am finding my way back to Hindi films. We have just had a fight and it looks like the next two hours will be strained – I won’t say a word unless she speaks first, I have told myself sulkily as the screening begins – but around 45 minutes in we are both sufficiently engaged by the film’s pace, music and the likable performances, to begin whispering to each other. Bluffmaster is hardly likely to be remembered as one of the seminal achievements of its time, but in that situation, with the right company, it works.

Now that this memory montage has begun, other incidents unspool non-chronologically through my mind. With three friends, I’m watching Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot le Fou at the rundown Paras hall in South Delhi during a film festival. Godard’s experiments with cinematic form have long been subjects of wonder for us, and so, when the image on the screen shakes wildly and loses focus for a few seconds, even though we know this is a technical problem (one frequently experienced at this venue), the joke is inevitable. “What was JLG trying to say here?” one of us goes in a faux-pedantic tone. We conjecture. We crack up. An avant-garde director has been out-avant-garded by faulty projection.

A few seconds of frivolity enhanced that viewing, but at other times laughter is sacrilegious. Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo is playing in a small hall at the PVR Saket multiplex, part of a half-hearted (and short-lived) effort by the theatre to screen “international classics” once a week. Right film, poor print, wrong crowd. The seats immediately around me are empty, I made sure of that, but from two rows ahead issue the groans of young plebs who clearly equate the director’s name with “murder mystery”. “Hitchcock has lost it, man,” someone says as if speaking of a school pal.

Chewing glumly on stale popcorn, I flashback to a few years earlier when I’m viewing a restored Vertigo print in my room, letting the languid visuals, punctuated by slow dissolves and Bernard Herrmann’s music, wash over me. The quality of that experience is inseparable from the fact that I am alone.