Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 97

December 19, 2011

One man and his dog

Been a little busy, but on Friday I got two trips out. First, Scott Andrews took me to see Sherlock Holmes 2, which was whizzy and silly and fun. Then I made the epic trek to Chiswick to review Hogarth's house for something out next year (which I shall post about when it happens). What follows is stuff I didn't say in that.

Hogarth lived in Chiswick between 1749 and his death in 1764. Chiswick seems quite proud of the connection. His house was opened to the public in 1904, but re-opened in November after a fire in 2009. In 2001, a statue by Jim Mathieson of Hogarth and his pug-dog Trump was unveiled on Chiswick High Street. It was unveiled by Ian Hislop and David Hockney - I assume symbolic of his status as satirist and artist.

A picture by Hogarth shows the house surrounded by fields, but now it's right next to a busy road and roundabout (both named after Hogarth). You can see and hear the traffic grumping past as you poke round the displays. (I did not put in my review that Donna Noble realises her taxi driver is a robot on this very road.)

The house was built in what was once an orchard, and the mulberry tree that apparently still blossoms each year is thought to be older than the building. You can just about make out the tree in this picture.

Hogarth lived in Chiswick between 1749 and his death in 1764. Chiswick seems quite proud of the connection. His house was opened to the public in 1904, but re-opened in November after a fire in 2009. In 2001, a statue by Jim Mathieson of Hogarth and his pug-dog Trump was unveiled on Chiswick High Street. It was unveiled by Ian Hislop and David Hockney - I assume symbolic of his status as satirist and artist.

A picture by Hogarth shows the house surrounded by fields, but now it's right next to a busy road and roundabout (both named after Hogarth). You can see and hear the traffic grumping past as you poke round the displays. (I did not put in my review that Donna Noble realises her taxi driver is a robot on this very road.)

The house was built in what was once an orchard, and the mulberry tree that apparently still blossoms each year is thought to be older than the building. You can just about make out the tree in this picture.

Published on December 19, 2011 17:54

December 8, 2011

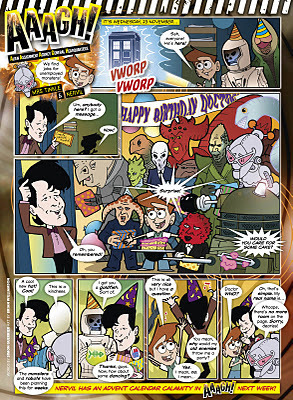

AAAGH! and the carol singers

Another festive AAAGH!, this one from

Doctor Who Adventures

#246 and owing a little to last year's Christmas special,

A Christmas Carol

, but with added monsters and tomfoolery. As ever, it's written by be, illustrated by Brian Williamson and edited by Paul Lang and Natalie Barnes - who also gave kind permission to post it here. You can read all my AAAGH!s.

Another festive AAAGH!, this one from

Doctor Who Adventures

#246 and owing a little to last year's Christmas special,

A Christmas Carol

, but with added monsters and tomfoolery. As ever, it's written by be, illustrated by Brian Williamson and edited by Paul Lang and Natalie Barnes - who also gave kind permission to post it here. You can read all my AAAGH!s.As an added treat, here's what Abigail is singing.

Published on December 08, 2011 13:31

December 6, 2011

Hundred year-old cat

The builder currently rebuilding our house made a cool discovery:

The house is at least 100 years old, possibly late 19th century. And there in the original brickwork are the paw prints of a cat. We're going to leave them on show.

The house is at least 100 years old, possibly late 19th century. And there in the original brickwork are the paw prints of a cat. We're going to leave them on show.

Published on December 06, 2011 13:54

December 1, 2011

AAAGH! and the Advent calendar

Another AAAGH!, this one marking the start of Advent. There's all sorts of Christmas festivities coming in Doctor Who Adventures in the next few weeks, as we approach the Christmas episode. As ever, the script for this silliness is by me, the art by Brian Williamson, and the strip was edited by Paul Lang and Natalie Barnes - who gave kind permission to post it here. You can also read all my AAAGH!s.

Published on December 01, 2011 09:39

November 24, 2011

First Wave interview

Daniel Tostevin interviewed me about my

Doctor Who

story

The First Wave

for the latest issue of Doctor Who Magazine. But I wittered on so much that he had bits of what I said left over. He has published my additional wittering on the official Daniel Tostevin website.

Published on November 24, 2011 14:11

November 23, 2011

Happy birthday Doctor Who, love AAAGH!

AAAGH! celebrate's Doctor Who's 48th birthday today in a bit of silliness written by me and illustrated by Brian Williamson.

Doctor Who Adventures

#244 is still in shops for another day, and includes a whole bunch of old-skool stuff, including mention of Koquillion.

AAAGH! celebrate's Doctor Who's 48th birthday today in a bit of silliness written by me and illustrated by Brian Williamson.

Doctor Who Adventures

#244 is still in shops for another day, and includes a whole bunch of old-skool stuff, including mention of Koquillion.As always, this AAAGH! was edited by Paul Lang and Natalie Barnes and posted here with their kind permission. You can also read all my AAAGH! s.

Published on November 23, 2011 11:50

November 21, 2011

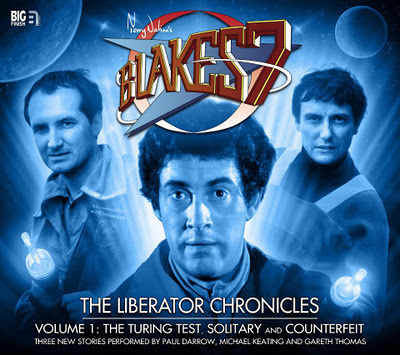

Blake box

For your delight and delectation, here is Anthony Lamb's cover for Blake's 7: The Liberator Chronicles , which includes The Turing Test - written by me and starring Paul Darrow as Avon and Michael Keating as Vila. It's out in February 2012.

Published on November 21, 2011 17:39

November 20, 2011

Ritzkrieg

Finished my chum Matthew Sweet's The West End Front this morning. It's a magnificent, funny and strange collection of stories about London's posh hotels during the Second World War (though he freely extends the scope when it means another good story). It was Book of the Week on Radio 4 last week - you've still a chance to hear Kenneth Cranham reading choice cuts on iPlayer.

Matthew has interviewed more than 100 people - those who were there at the time, or the families of those who have since died. The result is a gleefully gossipy account of some often shocking incidents, carefully backed up with solid documentary research.

The book undermines the sentimental view of the Second World War, the idea of a nation steadfastly keeping calm and carrying on, all stiff-upper lips and good humour. There's scandal and skulduggery, scoundrels, sex and death. Some of the events make for very uncomfortable reading. But really this is a testament to the strangeness of real life - in an extraordinary period of history and anyway. Matthew's got a good eye for the incongruous detail, the grotesque detail, that conjures the period vividly.

There's a wealth of top facts, too. Captain Leonard Plugge, Conservative MP for Chatham, gave his name to any "brazen commercialism in the media". Crooner Al Bowlly (whose work I adore) was killed by his own bedroom door. There's the extraordinary image of Winston Churchill, no longer Prime Minister and so no longer living at Downing Street, installed in the penthouse at Claridges because, his wife said, "We have nowhere to go". It is there, on a borrowed wireless, that he heard the news of Japanese surrender.

Matthew has interviewed more than 100 people - those who were there at the time, or the families of those who have since died. The result is a gleefully gossipy account of some often shocking incidents, carefully backed up with solid documentary research.

The book undermines the sentimental view of the Second World War, the idea of a nation steadfastly keeping calm and carrying on, all stiff-upper lips and good humour. There's scandal and skulduggery, scoundrels, sex and death. Some of the events make for very uncomfortable reading. But really this is a testament to the strangeness of real life - in an extraordinary period of history and anyway. Matthew's got a good eye for the incongruous detail, the grotesque detail, that conjures the period vividly.

There's a wealth of top facts, too. Captain Leonard Plugge, Conservative MP for Chatham, gave his name to any "brazen commercialism in the media". Crooner Al Bowlly (whose work I adore) was killed by his own bedroom door. There's the extraordinary image of Winston Churchill, no longer Prime Minister and so no longer living at Downing Street, installed in the penthouse at Claridges because, his wife said, "We have nowhere to go". It is there, on a borrowed wireless, that he heard the news of Japanese surrender.

"'Then he went out into the rain and there were three old ladies under an umbrella who had heard he was there and gave him a cheer.'"Many of the lively characters Matthew speaks of - and spoke to - have died, and as he argues the Second World War is now passing out of living memory. This chance to capture and record these fleeting ghosts before they are fully gone is utterly compelling.Philip Murphy, Alan Lennox-Boyd: A Biography (1999), quoted in Matthew Sweet, The West End Front, p. 286.

Published on November 20, 2011 16:02

November 19, 2011

Dream the myth onwards

Here's the introduction I wrote to the book of academic papers, The Mythological Dimensions of Doctor Who (2010) - available as a paperback and on Kindle and things.

Dream the myth onwardsThanks to editor Anthony S Burdge and Anne Petty at Kitsune Books for permission to post it here. I landed the Doctor in ancient Greece in my book, The Slitheen Excursion - where he met what might be the real people who inspired the myths of Athena, Noah and the Medusa, amongst others.

Simon Guerrier

Do stories matter if we know they're not true?

That seems to be central to the idea of myth. They are stories that matter. Ken Dowden, in his book The Uses of Greek Mythology, argues that "myths are believed, but not in the same way that history is"(1). If they were true they would be history. But stories still illuminate the truth.

The father of psychoanalysis certainly thought so. Sigmund Freud used the stories of ancient mythology to illuminate aspects of the human condition. Most famously, he named a group of unconscious and repressed desires after the mythical king of Thebes, Oedipus.

The story of Oedipus has been retold since at least the 5th Century BC. By linking to it, Freud suggested that the desires he'd uncovered were not new or localised. They were universal.

Freud was clearly fascinated by myth. His former home in London – now a museum – contains nearly 2,000 antiquities illustrating myths from the Near East, Egypt, Greece, Rome and China, many lined up on the desk where he worked. He argued that psychoanalysis could be applied to more than just a patient's dreams, but to "products of ethnic imagination such as myths and fairy tales" (2).

But, as Dowden points out, you can only psychoanalyse where there is a psyche. Who are we analysing when we probe ancient myths – which have been retold for thousands of years? Do we examine a myth as the dream of an original, single author, or of the culture that author belonged to? Dowden argues that "psychoanalytic interpretation of myth can only work if it reveals prevalent, or even universal, deep concerns of a larger cultural group"(3).

He also quotes Carl Jung, who developed the idea of the "collective unconscious", a series of archetypal images that we all share in the preconscious psyche and which, as a result, appear regularly in our myths. Jung warned against efforts to interpret the meanings of these images: "the most we can do is dream the myth onwards and give it a modern dress"(4).

That seems to me what Doctor Who does, retelling old stories in new ways, surprising us with the familiar. The archetypes of Doctor Who – the invasion, the base under siege, the person taken over by an alien force, regeneration – have been embedded for decades. Yet the series keeps finding new ways to present them, and new perspectives and insights along the way.

That's also true of this book, probing the Doctor's adventures for new perspectives and insights. The essays contained here don't take Doctor Who as the dream of one single author whose unconscious desires can now be exposed. Instead, it probes our shared mythology as Doctor Who fans – of which the TV show is just a part – to explore our own cultural unconscious.

"Myth" means many things in this book. It's any fiction with a ring of truth. It's any story with cultural of psychological value. It's any work with staying power, whose themes and ideas are still relevant generations after the first telling. It's the established, fictional history of characters and worlds, the "continuity" so often complex and contradictory. It's the moment at which a character becomes a hero or even a god. It's anything we want it to be.

And that is why it's so revealing.

(1) Dowden, Ken, The Uses of Greek Mythology, London: Routledge 2000 [1992], p. 3.

(2) Freud, Sigmund, Totem and Taboo, Leipzig and Vienna: 1913, English translation ed. J Strachey London 1955. Cited in Dowden, p. 30.

(3) Dowden, p. 31

(4) Jung, Carl and Kerényi, C, Science of Mythology: Essays on the myth of the divine child and the mysteries of Eleusis, 1949, English translation, cited in Dowden, p. 32

Published on November 19, 2011 10:13

November 18, 2011

Re: Re: The First Wave

[SPOILER WARNING!]

[SPOILER WARNING!]

[Whopping great spoilers for my recently released Doctor Who story, The First Wave, follow.]

[End of spoiler warning.]

Hello Rose

First I should thank you. Your post is full of nice things about my writing generally. You call me "educated and intelligent", which is not something I hear a lot. So thanks for those bits.

You clearly don't like The First Wave, and I don't intend to try to persuade you otherwise. But you make a number of claims that I don't think are fair. So I'll address those.

You make a lot of comments about Big Finish generally. I don't speak for Big Finish – what follows are my own opinions – and I'm not going to guess what producers or writers were thinking or trying to do. But there are openly gay and bisexual characters in several Big Finish Doctor Who stories, as well as in related ranges such as Bernice Summerfield and Graceless.

My own experience is that it's tricky writing an openly gay character in a Doctor Who audio story. There's already a lot to set up in a Doctor Who audio: a new location in time and space, created entirely from what characters tell us about it; a plot that hasn't been done before in all the hundreds of TV episodes, books, comics and other audios; an exciting monster and lots of jeopardy. Into that must go the Doctor and TV companion – and under the terms of Big Finish's licence with the BBC, they must be as they appeared on TV.

That doesn't leave a great deal of room for anyone else, so other characters tend to be sketched in lightly – character types that the listener can quickly visualise. I'd argue that we're rarely told the sexuality of any of the characters, heterosexual or otherwise.

Oliver Harper gets more depth than most because I created him as a new companion who'd appear in three stories. But his life and background are still quickly and lightly established. And that means it's tricky to avoid tokenism and cliché, to make him a character rather than a label or manifesto. You kindly praise my efforts in Oliver's previous two stories. Thank you.

But you don't like The First Wave specifically because I "stereotypically, pointlessly, offensively" killed off Oliver, who is gay. I'm sorry for causing any offence. You direct me to the TV tropes page on the "bury your gays" cliché. It's a good, fun piece that makes important points. But look again at what that page says:

Actor Peter Purves discusses how abruptly the cast were let go in this period on DVD documentaries on The Ark and The Gunfighters – both of which I worked on. The production team even tried to write out William Hartnell as the Doctor in The Celestial Toymaker, before doing so a few months later in The Tenth Planet. There's a sense in this season that no one is safe and no one gets a happy ending. Steven's own exit from the series in The Savages could have been happy – he goes off to be a king – but that's not how it's played. So what happens to Oliver is perfectly in keeping with the series at the time (something the terms of our licence with the BBC requires).

What's more, a new companion gives us a lot of freedom. Not only can I make him a stockbroker and gay, but I also don't have to return him safely at the end of a story to where he was at the start. That's something we have to do with the TV characters under the terms of our licence. So part of the appeal of creating a new companion is that the listener doesn't know how things will end – or if he will survive.

That's the central point of the three plays featuring Oliver: anyone can die, and the longer they stay with the Doctor, the more they're on borrowed time. The phrase "borrowed time" appears in all the stories, and The First Wave would have been called Borrowed Time had there not already been an Eleventh Doctor novel called that. From that starting point, I tried to write an adventure that was exciting and also moving. You're meant to like Oliver, and not like him dying.

You object to Oliver's "noble self-sacrificing death to save the main [i.e., heterosexual] characters"*. I don't think you're arguing that he should have died ignobly – perhaps screaming for mercy or siding with the villains. And I don't think you're arguing that I've killed him off because he's gay. I think you're arguing that because he's gay I should treat him differently from any other character. You want me to discriminate.

You praise my previous story, The Cold Equations, because Oliver's "sexuality wasn't constantly brought up, it was just a fact about him." But I'd argue that you've made his death – and the scene where he helps Steven dress up in The Perpetual Bond – all about his being gay.

I don't expect any of this to change your mind. But remember that I brought Sara Kingdom back from the dead. The return of Oliver Harper would be a cinch.

All the best,

Simon

(* I could also point out, pedantically, that the show offers little evidence that the Doctor or Steven are specially heterosexual. But anyway.)

[SPOILER WARNING!]

[Whopping great spoilers for my recently released Doctor Who story, The First Wave, follow.]

[End of spoiler warning.]

Hello Rose

First I should thank you. Your post is full of nice things about my writing generally. You call me "educated and intelligent", which is not something I hear a lot. So thanks for those bits.

You clearly don't like The First Wave, and I don't intend to try to persuade you otherwise. But you make a number of claims that I don't think are fair. So I'll address those.

You make a lot of comments about Big Finish generally. I don't speak for Big Finish – what follows are my own opinions – and I'm not going to guess what producers or writers were thinking or trying to do. But there are openly gay and bisexual characters in several Big Finish Doctor Who stories, as well as in related ranges such as Bernice Summerfield and Graceless.

My own experience is that it's tricky writing an openly gay character in a Doctor Who audio story. There's already a lot to set up in a Doctor Who audio: a new location in time and space, created entirely from what characters tell us about it; a plot that hasn't been done before in all the hundreds of TV episodes, books, comics and other audios; an exciting monster and lots of jeopardy. Into that must go the Doctor and TV companion – and under the terms of Big Finish's licence with the BBC, they must be as they appeared on TV.

That doesn't leave a great deal of room for anyone else, so other characters tend to be sketched in lightly – character types that the listener can quickly visualise. I'd argue that we're rarely told the sexuality of any of the characters, heterosexual or otherwise.

Oliver Harper gets more depth than most because I created him as a new companion who'd appear in three stories. But his life and background are still quickly and lightly established. And that means it's tricky to avoid tokenism and cliché, to make him a character rather than a label or manifesto. You kindly praise my efforts in Oliver's previous two stories. Thank you.

But you don't like The First Wave specifically because I "stereotypically, pointlessly, offensively" killed off Oliver, who is gay. I'm sorry for causing any offence. You direct me to the TV tropes page on the "bury your gays" cliché. It's a good, fun piece that makes important points. But look again at what that page says:

"Please note that sometimes gay characters die in fiction because in fiction sometimes people die (this is particularly true of soldiers at war, where Sitch Sexuality and Anyone Can Die are both common tropes); this isn't an if-then correlation, and it's not always meant to "teach us something" or indicative of some prejudice on the part of the creator - particularly if it was written after 1960. The problem isn't when gay characters are killed off: the problem is when gay characters are killed off far more often than straight characters, or when they're killed off because they are gay. This trope therefore won't apply to a series where anyone can die (and does).""Anyone can die (and does)" is a good summary of the era of Doctor Who in which The First Wave is set. By "era", I mean Season Three – not, as you argue, the First Doctor's adventures as a whole. In that season, Katarina and Sara die, Anne Chaplet (a sort-of companion in The Massacre) is apparently killed, Vicki is written out during a bloody battle that leaves Steven badly wounded, and Dodo vanishes off-screen having had her brain scrambled.

Actor Peter Purves discusses how abruptly the cast were let go in this period on DVD documentaries on The Ark and The Gunfighters – both of which I worked on. The production team even tried to write out William Hartnell as the Doctor in The Celestial Toymaker, before doing so a few months later in The Tenth Planet. There's a sense in this season that no one is safe and no one gets a happy ending. Steven's own exit from the series in The Savages could have been happy – he goes off to be a king – but that's not how it's played. So what happens to Oliver is perfectly in keeping with the series at the time (something the terms of our licence with the BBC requires).

What's more, a new companion gives us a lot of freedom. Not only can I make him a stockbroker and gay, but I also don't have to return him safely at the end of a story to where he was at the start. That's something we have to do with the TV characters under the terms of our licence. So part of the appeal of creating a new companion is that the listener doesn't know how things will end – or if he will survive.

That's the central point of the three plays featuring Oliver: anyone can die, and the longer they stay with the Doctor, the more they're on borrowed time. The phrase "borrowed time" appears in all the stories, and The First Wave would have been called Borrowed Time had there not already been an Eleventh Doctor novel called that. From that starting point, I tried to write an adventure that was exciting and also moving. You're meant to like Oliver, and not like him dying.

You object to Oliver's "noble self-sacrificing death to save the main [i.e., heterosexual] characters"*. I don't think you're arguing that he should have died ignobly – perhaps screaming for mercy or siding with the villains. And I don't think you're arguing that I've killed him off because he's gay. I think you're arguing that because he's gay I should treat him differently from any other character. You want me to discriminate.

You praise my previous story, The Cold Equations, because Oliver's "sexuality wasn't constantly brought up, it was just a fact about him." But I'd argue that you've made his death – and the scene where he helps Steven dress up in The Perpetual Bond – all about his being gay.

I don't expect any of this to change your mind. But remember that I brought Sara Kingdom back from the dead. The return of Oliver Harper would be a cinch.

All the best,

Simon

(* I could also point out, pedantically, that the show offers little evidence that the Doctor or Steven are specially heterosexual. But anyway.)

Published on November 18, 2011 11:42

Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers

Simon Guerrier isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.