Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 87

April 24, 2013

Doctor Who: 1972

Episode 330: The Three Doctors, episode 1

First broadcast: 5.50 pm, Saturday, 30 December 1972

<< back to 1971

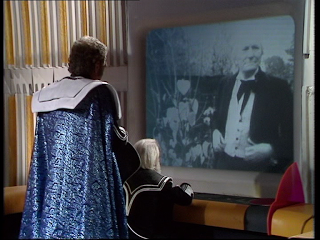

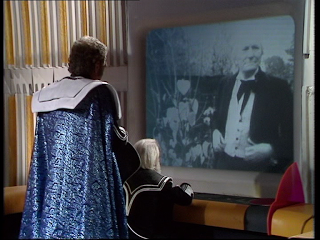

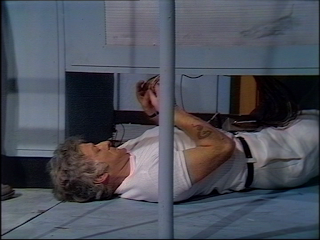

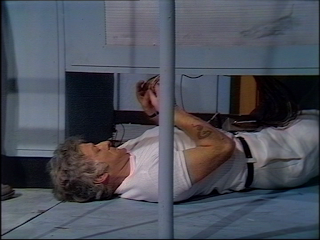

The Time Lords watch a new Second Doctor story.

The Time Lords watch a new Second Doctor story.

The Three Doctors, episode 1.First two items of trivia of no interest to anyone but me. The Three Doctors opened Doctor Who's 10th season but was shown closer to the ninth anniversary of the first episode being broadcast than it was the 10th. And when Patrick Troughton returned to the series, he'd been away for less time than David Tennant will have been when he comes back this November.

Anyway. I asked in my piece about 1970 how different Doctor Who's seventh season would have looked to viewers at the time. For all the Doctor might be stuck on Earth in an indeterminate near future, I argued that a lot of the show - the feel, the monsters, the quarries and corridors, the Radiophonic effects - were exactly the same. What changed was that we didn't see inside the TARDIS and the Doctor stopped being a reluctant hero and willingly sought out adventure. With 1971, I argued that Jo Grant made us wonder why we'd want adventures in space and time anyway.

By The Three Doctors, the Doctor had been stranded on Earth for three seasons, just three of the 13 stories allowing him to set foot on another world (four if you count wherever it is the TARDIS comes to rest in the last episode of The Time Monster). But of five stories in Season 9, two were about travelling in time on Earth and two were set in outer space. The production team have since said that the "exile" format was limiting and the show's original format had started to push through.

The Three Doctors, as well as bringing back the first two Doctors Who, also returns the show to the format as it was in their day: at the end, the Doctor can once more travel freely in time and space. (Jo doesn't seem all that thrilled by the prospect of the wonders to come: "I suppose you'll be rushing off, then," she sulks.)

But the story doesn't just free up the future of the series: it does the same for its past. In episode 1, the Time Lords must nab the Second Doctor from his timestream and plonk him into his own future. We glimpse on screen what he's up to just before they grab him.

The show has always hinted in dialogue at events we never saw - the First Doctor's time on Quinnis or with Henry VIII, the Second Doctor taking a medical degree under Lister, the Third Doctor knocking about with Chairman Mao and Napoleon. But here, on screen, we glimpse an adventure: the Second Doctor running from what might be an explosion or weird fog, then stopping to consider his next move.

It's not a clip from some old story: it's something new, presumably meant to fit unobtrusively among his original run of stories.

He's not alone. The First Doctor, too, is glimpsed in a new adventure with him pottering round a nice garden (which features again in The Five Doctors (1983)).

The Time Lords watch a new First Doctor story.

The Time Lords watch a new First Doctor story.

The Three Doctors, episode 1.And the Radio Times special released to mark the show's 10th anniversary also boasted a series of photos showing strange new adventures for the Doctor's former companions...

A new Cyberman adventure, with Ben and Polly.

A new Cyberman adventure, with Ben and Polly.

Radio Times Doctor Who 10th anniversary special / BBC.So I'm monstrously grateful to The Three Doctors. It didn't just set the series back on course. The books and CDs I now write for a living basically started here.

See also @theMindRobber's Twitter feed from 1972.

Next episode: 1973

First broadcast: 5.50 pm, Saturday, 30 December 1972

<< back to 1971

The Time Lords watch a new Second Doctor story.

The Time Lords watch a new Second Doctor story.The Three Doctors, episode 1.First two items of trivia of no interest to anyone but me. The Three Doctors opened Doctor Who's 10th season but was shown closer to the ninth anniversary of the first episode being broadcast than it was the 10th. And when Patrick Troughton returned to the series, he'd been away for less time than David Tennant will have been when he comes back this November.

Anyway. I asked in my piece about 1970 how different Doctor Who's seventh season would have looked to viewers at the time. For all the Doctor might be stuck on Earth in an indeterminate near future, I argued that a lot of the show - the feel, the monsters, the quarries and corridors, the Radiophonic effects - were exactly the same. What changed was that we didn't see inside the TARDIS and the Doctor stopped being a reluctant hero and willingly sought out adventure. With 1971, I argued that Jo Grant made us wonder why we'd want adventures in space and time anyway.

By The Three Doctors, the Doctor had been stranded on Earth for three seasons, just three of the 13 stories allowing him to set foot on another world (four if you count wherever it is the TARDIS comes to rest in the last episode of The Time Monster). But of five stories in Season 9, two were about travelling in time on Earth and two were set in outer space. The production team have since said that the "exile" format was limiting and the show's original format had started to push through.

The Three Doctors, as well as bringing back the first two Doctors Who, also returns the show to the format as it was in their day: at the end, the Doctor can once more travel freely in time and space. (Jo doesn't seem all that thrilled by the prospect of the wonders to come: "I suppose you'll be rushing off, then," she sulks.)

But the story doesn't just free up the future of the series: it does the same for its past. In episode 1, the Time Lords must nab the Second Doctor from his timestream and plonk him into his own future. We glimpse on screen what he's up to just before they grab him.

The show has always hinted in dialogue at events we never saw - the First Doctor's time on Quinnis or with Henry VIII, the Second Doctor taking a medical degree under Lister, the Third Doctor knocking about with Chairman Mao and Napoleon. But here, on screen, we glimpse an adventure: the Second Doctor running from what might be an explosion or weird fog, then stopping to consider his next move.

It's not a clip from some old story: it's something new, presumably meant to fit unobtrusively among his original run of stories.

He's not alone. The First Doctor, too, is glimpsed in a new adventure with him pottering round a nice garden (which features again in The Five Doctors (1983)).

The Time Lords watch a new First Doctor story.

The Time Lords watch a new First Doctor story.The Three Doctors, episode 1.And the Radio Times special released to mark the show's 10th anniversary also boasted a series of photos showing strange new adventures for the Doctor's former companions...

A new Cyberman adventure, with Ben and Polly.

A new Cyberman adventure, with Ben and Polly.Radio Times Doctor Who 10th anniversary special / BBC.So I'm monstrously grateful to The Three Doctors. It didn't just set the series back on course. The books and CDs I now write for a living basically started here.

See also @theMindRobber's Twitter feed from 1972.

Next episode: 1973

Published on April 24, 2013 01:00

April 23, 2013

Freedom, dignity and drones

I've been reading BF Skinner's Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971), which argues for a "technology of behaviour" or "cultural engineering". That sounds like the sort of thing that might feature in a sci-fi dystopia - which is chiefly why I've been reading it.

In some ways, Skinner's book reads as a chillingly impersonal manifesto for more control by the state or scientific elite over how we're brought up, arguing that much of our behaviour is simply a response to the conditions around us. In the nature/nurture debate, such a hot topic at the time, it's firmly on the side of the nurture.

Yet it's less about what should actually be done than it is how we think about improving behaviour. If we can only get beyond outdated ideas such as "free will" and autonomy, Skinner argues, we might finally progress.

I've found it by turns fascinating and frustrating, and it's often hard to tell when Skinner's examples are the results of scientifically rigorous experiment or just things he thinks to be true. But every so often there's a passage that stands out, such as this on the conflict between dignity and freedom.

I'm not convinced but I find myself puzzling over that when I should be building my dystopia. As so often, I post it here to clear it out of my head.

In some ways, Skinner's book reads as a chillingly impersonal manifesto for more control by the state or scientific elite over how we're brought up, arguing that much of our behaviour is simply a response to the conditions around us. In the nature/nurture debate, such a hot topic at the time, it's firmly on the side of the nurture.

Yet it's less about what should actually be done than it is how we think about improving behaviour. If we can only get beyond outdated ideas such as "free will" and autonomy, Skinner argues, we might finally progress.

I've found it by turns fascinating and frustrating, and it's often hard to tell when Skinner's examples are the results of scientifically rigorous experiment or just things he thinks to be true. But every so often there's a passage that stands out, such as this on the conflict between dignity and freedom.

"From time to time, advances in physical and biological technology have seemed to threaten worth or dignity when Medical science has reduced the need to suffer in silence and the chance to be admired for doing so. Fireproof buildings leave no room for brave firemen, or safe ships for brave sailors, or safe airplanes for brave pilots. The modern dairy barn has no place for a Hercules. When exhausting and dangerous work is no longer required, those who are hard-working and brave seem merely foolish.I find myself instinctively wanting to counter this thesis. Yet surely that last point is at the heart of discussions about the morality of using the atomic bomb at the end of World World Two (see my post on Codename Downfall - The Secret Plan to Invade Japan). It might also help explain why the use of remote drones seems so particularly wrong. The argument is often used against them that they kill civilian women and children as much as they do enemy combatants, but that can also be true of using soldiers. Is the problem more that drones, by reducing risk to our soldiers, make it too distastefully easy?

The literature of dignity conflicts here with the literature of freedom, which favors a reduction in aversive features of daily life, as by making behavior less arduous, dangerous, or painful, but a concern for personal worth sometimes triumphs over freedom from aversive stimulation - for example, when, quite apart from medicinal issues, painless childbirth is not as readily accepted as painless dentistry. A military expert, J.F.C. Fuller, has written: 'The highest military rewards are given for bravery and not for intelligence, and the introduction of any novel weapon which detracts from individual prowess is met with opposition'."

BF Skinner, Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971), p. 56.

(Fuller is apparently from "an article on 'Tactics', Encyclopedia Britannica, 14th edn.")

I'm not convinced but I find myself puzzling over that when I should be building my dystopia. As so often, I post it here to clear it out of my head.

Published on April 23, 2013 09:06

April 22, 2013

Doctor Who: 1971

Episode 293: Colony in Space, episode 1

First broadcast: 6.10 pm, Saturday, 10 April 1971

<< back to 1970

Jo unimpressed by all of time and space.

Jo unimpressed by all of time and space.

Colony in Space, episode 1There now seems to be a format for introducing new companions into Doctor Who. First, there's an adventure set in the present day - where the proto-companion lives and works. The Doctor stumbles in and they glimpse a strange, madder, better universe of wonders than they'd ever dreamt of. How can they resist when the Doctor offers to show them more?

The next stop is an especially mad future followed by a trip to somewhere in Earth history (or the other way round and they visit Earth history first). In doing so, the Doctor sets out his stall for Clara, Amy, Donna, Martha and Rose - and reminds the viewer at home of the scope and scale of the series. We are likely to be just as wowed by the new girl at all the show can do.

But it was not always like that. In the Doctor Who of the last millennia, companions weren't always from Earth, let alone the present day. Some didn't even seem bothered about travelling in time and space.

On screen, Liz Shaw never got to leave contemporary Earth (though a 2010 episode of The Sarah Jane Adventures says she now works on the Moon). Jo Grant didn't take a trip in the TARDIS until her 15th episode in the show. And her response to her first sight of an alien world is quite striking:

Why would a production team make a companion not want to travel with the Doctor? In the case of Jo, I think it's an important cue to the audience. The Third Doctor is stranded on Earth, unable (mostly) to go anywhere or when else. He's really quite cross about it - sulking and muttering and behaving in a way that even he admits is "childish". He resents his exile. In some stories that's used to great effect because we're not sure if he'll betray Earth and his friends just to get the TARDIS working.

But isn't there a danger, then, that we in the audience will also resent his exile - and the smaller scale and scope of the stories? He is, after all, the character we take our cues from. Well, not if the new companion can embrace the new format. If she says, "I don't want to travel in time and space anyway", then neither do we.

Next episode: 1972.

First broadcast: 6.10 pm, Saturday, 10 April 1971

<< back to 1970

Jo unimpressed by all of time and space.

Jo unimpressed by all of time and space.Colony in Space, episode 1There now seems to be a format for introducing new companions into Doctor Who. First, there's an adventure set in the present day - where the proto-companion lives and works. The Doctor stumbles in and they glimpse a strange, madder, better universe of wonders than they'd ever dreamt of. How can they resist when the Doctor offers to show them more?

The next stop is an especially mad future followed by a trip to somewhere in Earth history (or the other way round and they visit Earth history first). In doing so, the Doctor sets out his stall for Clara, Amy, Donna, Martha and Rose - and reminds the viewer at home of the scope and scale of the series. We are likely to be just as wowed by the new girl at all the show can do.

But it was not always like that. In the Doctor Who of the last millennia, companions weren't always from Earth, let alone the present day. Some didn't even seem bothered about travelling in time and space.

On screen, Liz Shaw never got to leave contemporary Earth (though a 2010 episode of The Sarah Jane Adventures says she now works on the Moon). Jo Grant didn't take a trip in the TARDIS until her 15th episode in the show. And her response to her first sight of an alien world is quite striking:

JO:It's the same a year later in The Curse of Peladon - Jo would much rather go on a date with dashing Mike Yates than visit another world. I'll talk another time about Jo's reasons for leaving the Doctor but I think it's important to see how early it's established that all of time and space is simply not her thing.

Doctor!

DOCTOR:

That's an alien world out there, Jo. Think of it.

JO:

I don't want to think of it. I want to go back to Earth.

Why would a production team make a companion not want to travel with the Doctor? In the case of Jo, I think it's an important cue to the audience. The Third Doctor is stranded on Earth, unable (mostly) to go anywhere or when else. He's really quite cross about it - sulking and muttering and behaving in a way that even he admits is "childish". He resents his exile. In some stories that's used to great effect because we're not sure if he'll betray Earth and his friends just to get the TARDIS working.

But isn't there a danger, then, that we in the audience will also resent his exile - and the smaller scale and scope of the stories? He is, after all, the character we take our cues from. Well, not if the new companion can embrace the new format. If she says, "I don't want to travel in time and space anyway", then neither do we.

Next episode: 1972.

Published on April 22, 2013 06:36

April 21, 2013

L for Lloyd

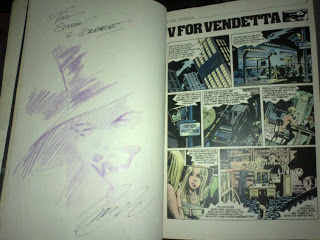

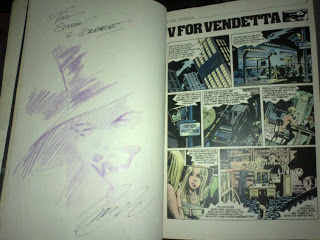

They say you shouldn't meet your heroes but yesterday at the splendid SWALC do run by Si Spencer, I got to meet David Lloyd - artist on V for Vendetta.

While he drew a portrait of V in my battered, beloved copy of the book that I bought when still at school, I told him that I'd once sat next to a pretty girl at a party who'd explained a point by saying, "It's a bit like in V for Vendetta". I few years later that pretty girl was my wife.

Gracious and engaging (I had to battle to buy him a pint), we also nattered a bit about politics and his new venture Aces Weekly , which is just £7 for a subscription and well worth your investment.

Artist David Lloyd kindly defacing

Artist David Lloyd kindly defacing

my copy of V for Vendetta My copy of V for Vendetta

My copy of V for Vendetta

kindly defaced by David LloydI also got to natter to Matthew Graham too, and compare notes on how cold it was at the filming of The Rebel Flesh and The Almost People. There were lots of other fine people, too. And ale. And sausage rolls.

Thanks to William Potter for suggesting such grand day out. Here's to the next one.

While he drew a portrait of V in my battered, beloved copy of the book that I bought when still at school, I told him that I'd once sat next to a pretty girl at a party who'd explained a point by saying, "It's a bit like in V for Vendetta". I few years later that pretty girl was my wife.

Gracious and engaging (I had to battle to buy him a pint), we also nattered a bit about politics and his new venture Aces Weekly , which is just £7 for a subscription and well worth your investment.

Artist David Lloyd kindly defacing

Artist David Lloyd kindly defacing my copy of V for Vendetta

My copy of V for Vendetta

My copy of V for Vendettakindly defaced by David LloydI also got to natter to Matthew Graham too, and compare notes on how cold it was at the filming of The Rebel Flesh and The Almost People. There were lots of other fine people, too. And ale. And sausage rolls.

Thanks to William Potter for suggesting such grand day out. Here's to the next one.

Published on April 21, 2013 03:55

April 20, 2013

Doctor Who: 1970

Episode 271: Doctor Who and the Silurians, episode 7

First broadcast: 5.15 pm, Saturday, 14 March 1970

<< back to 1969

The most un-Doctor Who that Doctor Who has ever been

The most un-Doctor Who that Doctor Who has ever been

Doctor Who and the Silurians, episode 7How different would Doctor Who’s seventh season have looked to viewers at the time?

The show was now in colour but most viewers were still watching in black and white. UNIT – the Doctor’s new employers – had been introduced the year before and his friend Lethbridge-Stewart even before that. New companion Liz Shaw is not all that different from Zoe from the previous year.

The look of the series was also familiar. Spearhead from Space was shot on film but then the series was back to being made in a TV studio, with the same fixed-camera look it would keep til the end of the 80s. The design, eerie music and men in rubber suits were all just as they had been.

But there are two major changes to the show. First, it’s all set in one place and time. We never even see inside the TARDIS – instead, the Doctor drives to his adventures in a funny yellow car.

Previous production teams had tried to make Doctor Who more contemporary and relevant. But Season 7 does not strand the Doctor in the (then) present day. Instead, the four stories are set a few years in the future – one with more stylised uniforms and where the space race has reached Mars. This allows the show a bit of freedom to play with new technologies and kill off half of London with a plague.

This near future is pretty bleak. Part of that bleakness is the way it wa shot. For example, on the gas towers in episodes two and three of Inferno, the location, acting, music and direction all make this ‘real’ world so distubring.

But this future Earth is also a serious, professional place. We never see the Brigadier or Liz Shaw’s home or friends, or get any sense of their lives outside their work. Each story is about large institutions: UNIT, a plastics factory, a mining operation, the space programme, another mining operation. When we do meet ordinary people, it’s just to see them scream before the monsters kill them.

The monsters this year – all new creations – are generally good. The Autons and Silurians both quickly returned to the series and still crop up in the series today. The Ambassadors are creepy but their story doesn’t really warrant a comeback (though baddies wearing space suits are cool), and the less said about the Primords the better.

But this season is less interested in monsters as our own bad behavior. More often than not stories turn on the greed, ambition and paranoia of ordinary humans.

There’s greedy poacher Sam Seeley in Spearhead and General Scobie’s pride over the waxwork of himself. In Doctor Who and the Silurians the Doctor is as much fighting the self-interest of Quinn, Masters and Lawrence as he is the creatures – who, just when he’s made peace, the Brigadier blows up. The Ambassadors of Death turn out to be quite friendly, the deaths the result of their misuse by nasty humans. In Inferno, Professor Stahlman refuses to heed health and safety warnings and nearly destroys the world. In the process, we glimpse another Earth where even the Doctor’s friends are baddies.

It’s no wonder the Doctor so resents being stuck on Earth – another reason this season seems so cold and hostile. It’s very different from his usual attitude, that humans are his favourite species, Earth his favourite planet.

That's the second thing that's changed. This Doctor is unlike anything we’ve seen before. It’s not just the incongruous sights of him naked in the shower or sporting a white tee-shirt and a prominent tattoo – the most un-Doctor Who that Doctor Who has ever been. Even when he wears old-fashioned clothes and has that same mix of brilliance and mischief, this is a different man from the first two Doctors. He’s not a reluctant hero but willingly seeks out adventure.

The Doctor’s new-found dynamism often drives the stories – he alone makes a deal with the Silurians, goes into space to rescue Mars Probe 7 and crosses over to the alternate Earth.

Until now, the Doctor always had a male companion to do the fights and stunts, but the Third Doctor is an expert in alien martial arts. The Brigadier – who could have been given all the action – is often more of a hindrance than a help. Meeting the evil Brigade-Leader doesn’t mellow the Doctor’s opinion of his boss. He storms off in protest at the end of the season, and then has to come crawling back when he needs the man’s help.

It’s this relationship that defines the season. Professional, cold and uneasy, Season 7 is a bold, grown-up take on Doctor Who.

(A version of the above appeared as "Countdown to 50: Season 7" in Doctor Who Magazine #436 in June 2011. Thanks to Tom Spilsbury for permission to reproduce it here.)

Next episode: 1971

First broadcast: 5.15 pm, Saturday, 14 March 1970

<< back to 1969

The most un-Doctor Who that Doctor Who has ever been

The most un-Doctor Who that Doctor Who has ever beenDoctor Who and the Silurians, episode 7How different would Doctor Who’s seventh season have looked to viewers at the time?

The show was now in colour but most viewers were still watching in black and white. UNIT – the Doctor’s new employers – had been introduced the year before and his friend Lethbridge-Stewart even before that. New companion Liz Shaw is not all that different from Zoe from the previous year.

The look of the series was also familiar. Spearhead from Space was shot on film but then the series was back to being made in a TV studio, with the same fixed-camera look it would keep til the end of the 80s. The design, eerie music and men in rubber suits were all just as they had been.

But there are two major changes to the show. First, it’s all set in one place and time. We never even see inside the TARDIS – instead, the Doctor drives to his adventures in a funny yellow car.

Previous production teams had tried to make Doctor Who more contemporary and relevant. But Season 7 does not strand the Doctor in the (then) present day. Instead, the four stories are set a few years in the future – one with more stylised uniforms and where the space race has reached Mars. This allows the show a bit of freedom to play with new technologies and kill off half of London with a plague.

This near future is pretty bleak. Part of that bleakness is the way it wa shot. For example, on the gas towers in episodes two and three of Inferno, the location, acting, music and direction all make this ‘real’ world so distubring.

But this future Earth is also a serious, professional place. We never see the Brigadier or Liz Shaw’s home or friends, or get any sense of their lives outside their work. Each story is about large institutions: UNIT, a plastics factory, a mining operation, the space programme, another mining operation. When we do meet ordinary people, it’s just to see them scream before the monsters kill them.

The monsters this year – all new creations – are generally good. The Autons and Silurians both quickly returned to the series and still crop up in the series today. The Ambassadors are creepy but their story doesn’t really warrant a comeback (though baddies wearing space suits are cool), and the less said about the Primords the better.

But this season is less interested in monsters as our own bad behavior. More often than not stories turn on the greed, ambition and paranoia of ordinary humans.

There’s greedy poacher Sam Seeley in Spearhead and General Scobie’s pride over the waxwork of himself. In Doctor Who and the Silurians the Doctor is as much fighting the self-interest of Quinn, Masters and Lawrence as he is the creatures – who, just when he’s made peace, the Brigadier blows up. The Ambassadors of Death turn out to be quite friendly, the deaths the result of their misuse by nasty humans. In Inferno, Professor Stahlman refuses to heed health and safety warnings and nearly destroys the world. In the process, we glimpse another Earth where even the Doctor’s friends are baddies.

It’s no wonder the Doctor so resents being stuck on Earth – another reason this season seems so cold and hostile. It’s very different from his usual attitude, that humans are his favourite species, Earth his favourite planet.

That's the second thing that's changed. This Doctor is unlike anything we’ve seen before. It’s not just the incongruous sights of him naked in the shower or sporting a white tee-shirt and a prominent tattoo – the most un-Doctor Who that Doctor Who has ever been. Even when he wears old-fashioned clothes and has that same mix of brilliance and mischief, this is a different man from the first two Doctors. He’s not a reluctant hero but willingly seeks out adventure.

The Doctor’s new-found dynamism often drives the stories – he alone makes a deal with the Silurians, goes into space to rescue Mars Probe 7 and crosses over to the alternate Earth.

Until now, the Doctor always had a male companion to do the fights and stunts, but the Third Doctor is an expert in alien martial arts. The Brigadier – who could have been given all the action – is often more of a hindrance than a help. Meeting the evil Brigade-Leader doesn’t mellow the Doctor’s opinion of his boss. He storms off in protest at the end of the season, and then has to come crawling back when he needs the man’s help.

It’s this relationship that defines the season. Professional, cold and uneasy, Season 7 is a bold, grown-up take on Doctor Who.

(A version of the above appeared as "Countdown to 50: Season 7" in Doctor Who Magazine #436 in June 2011. Thanks to Tom Spilsbury for permission to reproduce it here.)

Next episode: 1971

Published on April 20, 2013 01:00

April 19, 2013

Doctor Who: 1969

Episode 236: The Seeds of Death, episode 5

First broadcast: 5.15 pm, Saturday, 22 February 1969

<< back to 1968

"Patrick Troughton was very good at looking scared"

"Patrick Troughton was very good at looking scared"

The Seeds of Death, episode 5I love The Seeds of Death, and tried to match the tone and feel of it when I wrote my Second Doctor audio story Shadow of Death .

I also got to make a short documentary that went on the Seeds of Death DVD, "Monsters Who Came Back For More!", where wise Nicholas Briggs said:

Sadly, we'd didn't get commissioned for what may be my favourite thing we ever pitched:

Next episode: 1970

First broadcast: 5.15 pm, Saturday, 22 February 1969

<< back to 1968

"Patrick Troughton was very good at looking scared"

"Patrick Troughton was very good at looking scared"The Seeds of Death, episode 5I love The Seeds of Death, and tried to match the tone and feel of it when I wrote my Second Doctor audio story Shadow of Death .

I also got to make a short documentary that went on the Seeds of Death DVD, "Monsters Who Came Back For More!", where wise Nicholas Briggs said:

"One thing that used to scare me as a kid was seeing how scared the other characters were on television. Which is why [I remember] the Second Doctor stories ... with such fondness because Patrick Troughton was very good at looking scared. And that's what kids respond to. They respond to cues. You say to them "this is scary" by doing that and they believe it."That nicely follows on from what I said last time about Doctor Who's scariness being a big part of its appeal. We'll come back to the importance of cues to the audience another time...

Sadly, we'd didn't get commissioned for what may be my favourite thing we ever pitched:

"Attack of the Bubble MachineBut something a little like that worked really well when Dick and Dom discovered the genius of Delia Derbyshire (bother: it's just been removed from iPlayer).

CBBC’s Ed Petrie and Oucho recreate the cliffhanger of The Seeds of Death episode 5, showing us how it was done. First they build a giant bubble machine. But it’s not just the physics of how the machine operates, they also need the all-important sound effects (added later). Ed and Oucho create their own sound effects (perhaps with the help of Dick Mills). Then, the most important thing: the actor selling the effect with studied realism i.e. Ed trying to replicate Troughton larking about and corpsing in the bubbles. If budget allows, we have Ed being saved by Wendy Padbury, who explains she couldn't stop laughing last time."

Next episode: 1970

Published on April 19, 2013 01:00

April 18, 2013

Two comics with William Potter

A few years ago, I worked for William Potter on the esteemed journal SpongeBob SquarePants' Krusty Kards Collection and a Shrek sticker book. I have also bounced around to his band, CUD, more than once. But more recently, we've worked on some comics.

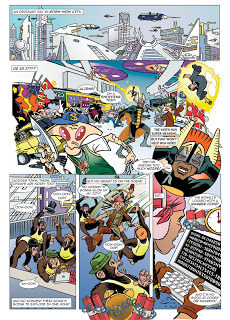

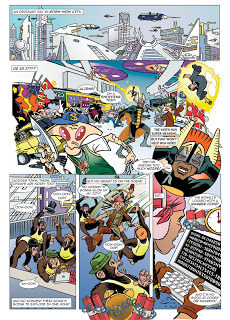

The 100% Awesomes was produced for the Autism Education Trust as part of a teaching pack to "promote awareness of difference and autism" among school children in years five to seven. Here is the first page:

The 100% Awesomes, page 1

The 100% Awesomes, page 1

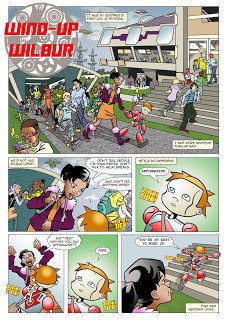

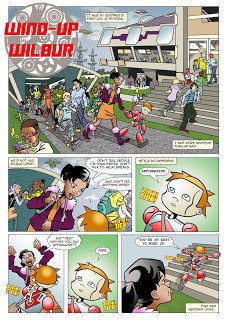

Art by William PotterWilliam and I then worked on a pitch for an original series, Wind-Up Wilbur, about a robot boy (sadly, the strip wasn't picked up). Here's the first page of that:

Wind-Up Wilbur, page 1

Wind-Up Wilbur, page 1

Art by William Potter

The 100% Awesomes was produced for the Autism Education Trust as part of a teaching pack to "promote awareness of difference and autism" among school children in years five to seven. Here is the first page:

The 100% Awesomes, page 1

The 100% Awesomes, page 1Art by William PotterWilliam and I then worked on a pitch for an original series, Wind-Up Wilbur, about a robot boy (sadly, the strip wasn't picked up). Here's the first page of that:

Wind-Up Wilbur, page 1

Wind-Up Wilbur, page 1Art by William Potter

Published on April 18, 2013 02:22

April 17, 2013

Doctor Who: 1968

Episode 152:

The Enemy of the World

, episode 6 - or rather, just after it

First broadcast: 5.46 pm, Saturday, 27 January 1968

<< back to 1967

I've chosen something a bit different this time: something that there aren't any images from and that wasn't even an episode. But TardisTimegirl has done an amazing job, animating the surviving soundtrack of a specially shot Doctor Who trailer. It was shown at the end of the final episode of The Enemy of the World to advertise the next story.

It's fun, the Doctor warning children that their parents might be scared of the next story. But it's also a bit cheeky. Not long before this trailer must have been written and filmed, the makers of Doctor Who were in trouble for making the series too gruesome.

On 23 September 1967, part four of The Tomb of the Cybermen included a scene of white goo foaming from a dead Cyberman's chest. That had generated some degree of complaint, and on 26 September co-writer Kit Pedler appeared on a new BBC programme, Talkback, to discuss whether the show was too violent for children.

The footage for that programme no longer exists, but the soundtrack survives - and an excerpt is included on the audiobook Doctor Who at the BBC volume 2 . Referring to the debate in the following programme (which does exist in the archive), presenter David Coleman joked of Doctor Who, "perhaps it's too scary for grown-ups"...

And that's what the trailer is playing on. It’s a fun gag, but it acknowledges something that was then quite new, something we almost take for granted now. Doctor Who is best when its scary; that's why children love it.

Next episode: 1969

First broadcast: 5.46 pm, Saturday, 27 January 1968

<< back to 1967

I've chosen something a bit different this time: something that there aren't any images from and that wasn't even an episode. But TardisTimegirl has done an amazing job, animating the surviving soundtrack of a specially shot Doctor Who trailer. It was shown at the end of the final episode of The Enemy of the World to advertise the next story.

It's fun, the Doctor warning children that their parents might be scared of the next story. But it's also a bit cheeky. Not long before this trailer must have been written and filmed, the makers of Doctor Who were in trouble for making the series too gruesome.

On 23 September 1967, part four of The Tomb of the Cybermen included a scene of white goo foaming from a dead Cyberman's chest. That had generated some degree of complaint, and on 26 September co-writer Kit Pedler appeared on a new BBC programme, Talkback, to discuss whether the show was too violent for children.

The footage for that programme no longer exists, but the soundtrack survives - and an excerpt is included on the audiobook Doctor Who at the BBC volume 2 . Referring to the debate in the following programme (which does exist in the archive), presenter David Coleman joked of Doctor Who, "perhaps it's too scary for grown-ups"...

And that's what the trailer is playing on. It’s a fun gag, but it acknowledges something that was then quite new, something we almost take for granted now. Doctor Who is best when its scary; that's why children love it.

Next episode: 1969

Published on April 17, 2013 01:00

April 16, 2013

Crossing the Rubicon

On 10 January, 49 BC, Julius Caesar marched his army south over a small river called the Rubicon - and the world changed. It was not the size of the river that mattered but that it was a border. Caesar was breaking a sacred law by taking an army into Rome - that single act is often seen as the pivotal moment in the collapse of the Roman Republic.

Tom Holland's Rubicon (2003) is excellent at explaining why, and charting a hundred years of history to give us the full context. Comprehensive, insightful, dryly witty and full of telling detail, its an excellent book - I only wish I'd sooner heeded all those who told me to read it.

I already knew a lot of the story from studying Asterix books and Shakespeare's plays, and watching I, Claudius and Rome . More recently, I loved Imperium and Lustrum, Robert Harris' excellent Cicero novels, as told by his slave Tiro (who invented shorthand and in some ways the parliamentary reporting job I do now).

There's a reason the fall of the Republic is so well known. Partly, it's because so much of the legal and political systems of Western civilisation are based on those of Rome. That's why the books and TV dramas still resonate so strongly. Harris, for example, makes Cicero's political wheeler-dealing feel entirely modern.

But it's more than that. The fall of the Republic is a tragedy about a system established for the common good being undone by personal gain. It serves as a warning to the liberal minded and a benchmark for the greedy. It's almost too easy to link the fall of Caesar to that of the last of his namesakes, the Csars, in Russia less than a century ago; or to link the fall of the Republic to what happened in Germany in the 1930s. The Royal Shakespeare Company's current production of Julius Caesar "finds dark contemporary echoes in modern Africa". Or we might liken the fall of the Republic to what's happening now to the welfare state or NHS, or even press regulation - as the Prime Minister did.

Holland doesn't make those pat analogies, thank heavens, concentrating instead on the personalities and culture. He's especially good at conjuring the worldview of the time.

At one point, with the town starving, Vercingetorex sent the women and children out of the town, trusting that Caesar's army would not kill them. They did not; but nor did they let them pass, and the women and children were left to starve to death outside the town walls, Caesar shaming Vercingetorex in the most appalling way. Yet it's hard not to admire Caesar at this point.

Incidentally, I have a pet theory that Asterix's blacksmith, Fulliautomatix (Cétautomatix in the French original) is based on the famous sculpture "The Dying Gaul":

The Dying Gaul, photo by Jean-Christophe BenoistThe Dr tells me that nineteenth century classicists had much fun pointing out the likeness between the statue and the eminent archaeologist, Adolf Furtwängler...

The Dying Gaul, photo by Jean-Christophe BenoistThe Dr tells me that nineteenth century classicists had much fun pointing out the likeness between the statue and the eminent archaeologist, Adolf Furtwängler...

Anyhow, we were talking about Caesar. The one thing I'd never quite understood was why Caesar decided to break the rules of the Republic, so sacred for centuries, and make himself dictator - effectively a king. Holland shows how previous bully-boys such as Sulla ended up, and suggests that Caesar was more than merely yet another Roman gangster.

He also shows us how shrewd an operator and gambler Caesar could be, playing the system to advance to the top. And he suggests that Caesar's sex life was not wanting. In readings of Shakespeare, and in the series Rome, Egypt is the decadent fallen empire, the temptations depraved and libidinous. It had strategic value because it supplied grain to the Roman empire - so anyone who ruled Egypt had a leash round the throat of Rome. But for all that, I never quite got why Caesar fell for it so completely.

And then Holland opens a chapter with a glorious bit of scene-setting:

I've concentrated on Caesar here, but Holland's book is dense with characters, strangeness and wonder - a history to be savoured, then pored over again.

Tom Holland's Rubicon (2003) is excellent at explaining why, and charting a hundred years of history to give us the full context. Comprehensive, insightful, dryly witty and full of telling detail, its an excellent book - I only wish I'd sooner heeded all those who told me to read it.

I already knew a lot of the story from studying Asterix books and Shakespeare's plays, and watching I, Claudius and Rome . More recently, I loved Imperium and Lustrum, Robert Harris' excellent Cicero novels, as told by his slave Tiro (who invented shorthand and in some ways the parliamentary reporting job I do now).

There's a reason the fall of the Republic is so well known. Partly, it's because so much of the legal and political systems of Western civilisation are based on those of Rome. That's why the books and TV dramas still resonate so strongly. Harris, for example, makes Cicero's political wheeler-dealing feel entirely modern.

But it's more than that. The fall of the Republic is a tragedy about a system established for the common good being undone by personal gain. It serves as a warning to the liberal minded and a benchmark for the greedy. It's almost too easy to link the fall of Caesar to that of the last of his namesakes, the Csars, in Russia less than a century ago; or to link the fall of the Republic to what happened in Germany in the 1930s. The Royal Shakespeare Company's current production of Julius Caesar "finds dark contemporary echoes in modern Africa". Or we might liken the fall of the Republic to what's happening now to the welfare state or NHS, or even press regulation - as the Prime Minister did.

Holland doesn't make those pat analogies, thank heavens, concentrating instead on the personalities and culture. He's especially good at conjuring the worldview of the time.

"As ever, [Caesar] loved to dazzle, to overawe. The building and levelling of a bridge across the Rhine had served only to whet his appetite for even more spectacular exploits. So it was that no sooner had Caesar crossed his men back into Gaul than he was marching northwards, towards the Channel coast and the the encircling Ocean.

Set within its icy waters waited the fabulous island of Britain. It was as drenched in mystery as in rain and fog. Back in Rome people doubted whether it existed at all. Even traders and merchants, Caesar's usual sources of information, could provide only the sketchiest details. Their resistance to travel widely through the island was hardly surprising. It was well known that barbarians became more savage the further north one travelled, indulging in any number of unspeakable habits, such as cannibalism, and even - repellently - the drinking of milk. To teach them respect for the name of the Republic would be an achievement of Homeric proportions. For Caesar, who never let anyone forget that he could trace his ancestry back to the time of the Trojan War, the temptation was irresistible.

... It was indeed to prove a journey back in time. Waiting for the invaders on the Kentish cliffs was a scene straight out of legend: warriors careering up and down in chariots, just as Hector and Achilles had done on the plain of Troy. To add to the exotic nature of it all, the Britons wore peculiar facial hair and were painted blue."As a result, we get a sense of why the Romans found Caesar so extraordinary. His "invasion" of Britain was hardly a success, and yet:

Tom Holland, Rubicon - The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic, pp. 274-5.

"Even the lack of plunder did little to dampen the general mood of wild enthusiasm ... In their impact on the waiting public Caesar's expeditions to Britain have been aptly compared to the moon landings: 'they were an imagination-defying epic, an achievement at once technical and straight out of an adventure story'."I had some sense of the brutal power of the Roman war machine having read Mortimer Wheeler's The Siege of Maiden Castle, England - read it; it's a brilliant reconstruction based on the archaeology, and informed by Wheeler's own hellish experience of World War One. With similar ghoulish delight, Holland describes over five pages (pp. 277-81) Caesar's siege of Alesia (near modern Paris), where he was vastly outnumbered and facing an implacable foe in the Gaulish leader Vercingetorex.

Ibid., p. 276 (the quotation from Goudineau, César, p. 335).

At one point, with the town starving, Vercingetorex sent the women and children out of the town, trusting that Caesar's army would not kill them. They did not; but nor did they let them pass, and the women and children were left to starve to death outside the town walls, Caesar shaming Vercingetorex in the most appalling way. Yet it's hard not to admire Caesar at this point.

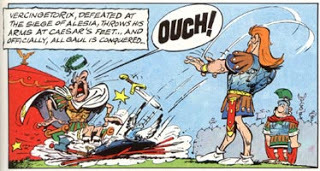

"Outnumbered by the army he was besieging, and vastly outnumbered by the army that had been besieging him in turn, Caesar defeated both. It was the greatest, most astonishing victory of his career."He ought to be a monster, and yet somehow he's a hero. Though that's not quite how the story was depicted in Asterix:

Ibid., p. 280.

Incidentally, I have a pet theory that Asterix's blacksmith, Fulliautomatix (Cétautomatix in the French original) is based on the famous sculpture "The Dying Gaul":

The Dying Gaul, photo by Jean-Christophe BenoistThe Dr tells me that nineteenth century classicists had much fun pointing out the likeness between the statue and the eminent archaeologist, Adolf Furtwängler...

The Dying Gaul, photo by Jean-Christophe BenoistThe Dr tells me that nineteenth century classicists had much fun pointing out the likeness between the statue and the eminent archaeologist, Adolf Furtwängler...Anyhow, we were talking about Caesar. The one thing I'd never quite understood was why Caesar decided to break the rules of the Republic, so sacred for centuries, and make himself dictator - effectively a king. Holland shows how previous bully-boys such as Sulla ended up, and suggests that Caesar was more than merely yet another Roman gangster.

He also shows us how shrewd an operator and gambler Caesar could be, playing the system to advance to the top. And he suggests that Caesar's sex life was not wanting. In readings of Shakespeare, and in the series Rome, Egypt is the decadent fallen empire, the temptations depraved and libidinous. It had strategic value because it supplied grain to the Roman empire - so anyone who ruled Egypt had a leash round the throat of Rome. But for all that, I never quite got why Caesar fell for it so completely.

And then Holland opens a chapter with a glorious bit of scene-setting:

"The coastline of the Nile Delta had always been treacherous. Low-lying and featureless, it offered nothing to help a sailor find his way. Even so, navigators who approached Egypt were not entirely bereft of guidance. At night, far distant from its shore, a dot of light flickered low in the southern sky. By day it could be seen for what it was: not a star, but a great lantern, set upon a tower, visible from miles out to sea. This was the Pharos, not only the tallest building ever built by the Greeks, but also, thanks to its endless recycling on tourist trinkets, the most instantly recognisable. A triumph of vision and engineering, the great lighthouse served as the perfect symbol for what it advertised: megalopolis - the most stupendous place on Earth.

Even Roman visitors had to acknowledge that Alexandria was something special. When Caesar, three days after Pompey's murder, sailed past the island on which the Pharos stood, he was arriving at a city larger, more cosmopolitan and certainly far more beautiful than his own. If Rome, shabby labyrinthine, stood as a monument to the rugged virtues of the Republic, then Alexandria bore witness to what a king could achieve."And it all clicked into place.

Ibid., p. 325.

I've concentrated on Caesar here, but Holland's book is dense with characters, strangeness and wonder - a history to be savoured, then pored over again.

Published on April 16, 2013 14:23

April 13, 2013

Doctor Who: 1967

Episode 141:

The Ice Warriors

, episode two

First broadcast: 5.25 pm, Saturday 18 November, 1967

<< back to 1966

Varga the Ice Warrior menaces Victoria

Varga the Ice Warrior menaces Victoria

The Ice Warriors , episode twoTonight, the Ice Warriors return to Doctor Who in Cold War - their fifth story, and their first since 1974. I've chosen a moment from their debut story to talk about something clever the show does to disguise its limited budget. It's something that also means it better gets into our heads...

Doctor Who has all sorts of tricks for making it seem more expensive than it really is. In reality, there are a limited number of sets, set-ups and actors, but the producers reuse sets and costumes, or film different episodes (set in different times, even different planets) in a single block, and use effects to fool us.

When the Ice Warriors made their first appearance in 1967, the clever producers had also established a formula that made the most of the limited studio space available to the show at the time. Almost every week, the Doctor would be trapped in a control room with a group of terrified humans while monsters tried to break down the door.

Yet, those adventures still suggested an extraordinary scale. The first episode of each story quickly sets up that we’re somewhere strikingly different, usually with location filming. In The Tomb of the Cybermen, we cut from the interior of the TARDIS (shot on film and looking amazing) to a multiracial expedition of archaeologists setting off explosives on an alien world. In the next story, we see Doctor Who’s first location filming in another country, as a Welsh valley doubles for Tibet. Then it’s The Ice Warriors, in which glaciers roll over Britain in the future. The next story begins with a helicopter chase on a beach in Australia, like something out of a Bond film. They’re all big, vivid worlds created very quickly (and economically) before we get locked in a control room.

We deal with big concepts, too: a world war that changes which nations are super powers or climate change run out of control. The Wheel in Space riffs off the near-future realism of 2001: A Space Odyssey - which had its premiere two weeks before the broadcast of episode one.

But these big images are grounded in simple, cost-effective reality. The Web of Fear manages to convince us that London is deserted by showing us a newspaper billboard and the power being off in the Tube.

This season is all about inexpensive tricks done with maximum effect, such as when the Doctor turns out to be the spitting image of the wicked Salamander. Previous stories had shown us doubles of the Doctor, but this is the best example yet. We’re not always sure who we’re watching – our hero or the villain – right up to the neat twist at the end where Salamander tries to steal the TARDIS.

Another neat trick is bringing young Professor Travers back two stories later but as an old man. And is it conscious that this season even plays with its own ‘base under siege’ format? In The Enemy of the World, the Doctor needs to rescue people from their underground base.

But the moment I've chosen from The Ice Warriors because of a line of dialogue. Often, the most vivid moments of Doctor Who are things we never see: the silent gas dirigibles of the Hoothi mentioned in The Brain of Morbius, World War Six as described in The Talons of Weng-Chiang, the Time War between the Doctor's people and the Daleks that has haunted the show since it came back in 2005...

It's not just big events, either. Varga the Ice Warrior threatens Victoria, but she doesn't recognise the device he's holding. "Sonic gun," Varga hisses - and we'll see it used to kill people in this and the Warrior's next three TV adventures (and perhaps tonight as well).

It's a pretty boring prop, just a tube with a light in the end when it's fired. There's then a wobbly effect over the person being killed and the actor cries out and falls to the floor. It's not much different from any other sci-fi killing, except that I find the deaths by sonic gun particularly vivid and horrible, because of a line of dialogue describing something we'll never see. I think it colours every future death inflicted by the Ice Warriors, and makes them a far more chilling monster.

Varga warns Victoria: "It will burst your brain with noise."

Next episode: 1968

First broadcast: 5.25 pm, Saturday 18 November, 1967

<< back to 1966

Varga the Ice Warrior menaces Victoria

Varga the Ice Warrior menaces VictoriaThe Ice Warriors , episode twoTonight, the Ice Warriors return to Doctor Who in Cold War - their fifth story, and their first since 1974. I've chosen a moment from their debut story to talk about something clever the show does to disguise its limited budget. It's something that also means it better gets into our heads...

Doctor Who has all sorts of tricks for making it seem more expensive than it really is. In reality, there are a limited number of sets, set-ups and actors, but the producers reuse sets and costumes, or film different episodes (set in different times, even different planets) in a single block, and use effects to fool us.

When the Ice Warriors made their first appearance in 1967, the clever producers had also established a formula that made the most of the limited studio space available to the show at the time. Almost every week, the Doctor would be trapped in a control room with a group of terrified humans while monsters tried to break down the door.

Yet, those adventures still suggested an extraordinary scale. The first episode of each story quickly sets up that we’re somewhere strikingly different, usually with location filming. In The Tomb of the Cybermen, we cut from the interior of the TARDIS (shot on film and looking amazing) to a multiracial expedition of archaeologists setting off explosives on an alien world. In the next story, we see Doctor Who’s first location filming in another country, as a Welsh valley doubles for Tibet. Then it’s The Ice Warriors, in which glaciers roll over Britain in the future. The next story begins with a helicopter chase on a beach in Australia, like something out of a Bond film. They’re all big, vivid worlds created very quickly (and economically) before we get locked in a control room.

We deal with big concepts, too: a world war that changes which nations are super powers or climate change run out of control. The Wheel in Space riffs off the near-future realism of 2001: A Space Odyssey - which had its premiere two weeks before the broadcast of episode one.

But these big images are grounded in simple, cost-effective reality. The Web of Fear manages to convince us that London is deserted by showing us a newspaper billboard and the power being off in the Tube.

This season is all about inexpensive tricks done with maximum effect, such as when the Doctor turns out to be the spitting image of the wicked Salamander. Previous stories had shown us doubles of the Doctor, but this is the best example yet. We’re not always sure who we’re watching – our hero or the villain – right up to the neat twist at the end where Salamander tries to steal the TARDIS.

Another neat trick is bringing young Professor Travers back two stories later but as an old man. And is it conscious that this season even plays with its own ‘base under siege’ format? In The Enemy of the World, the Doctor needs to rescue people from their underground base.

But the moment I've chosen from The Ice Warriors because of a line of dialogue. Often, the most vivid moments of Doctor Who are things we never see: the silent gas dirigibles of the Hoothi mentioned in The Brain of Morbius, World War Six as described in The Talons of Weng-Chiang, the Time War between the Doctor's people and the Daleks that has haunted the show since it came back in 2005...

It's not just big events, either. Varga the Ice Warrior threatens Victoria, but she doesn't recognise the device he's holding. "Sonic gun," Varga hisses - and we'll see it used to kill people in this and the Warrior's next three TV adventures (and perhaps tonight as well).

It's a pretty boring prop, just a tube with a light in the end when it's fired. There's then a wobbly effect over the person being killed and the actor cries out and falls to the floor. It's not much different from any other sci-fi killing, except that I find the deaths by sonic gun particularly vivid and horrible, because of a line of dialogue describing something we'll never see. I think it colours every future death inflicted by the Ice Warriors, and makes them a far more chilling monster.

Varga warns Victoria: "It will burst your brain with noise."

Next episode: 1968

Published on April 13, 2013 01:00

Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers

Simon Guerrier isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.