Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 43

July 8, 2020

Time Scope

I very nobly gave a couple of things to Time Scope, a new unofficial and unauthorised anthology of Doctor Who stories, poetry and art - 100% of the money from which is going to the charity Scope. It's edited by Matthew Rimmer.Buy Time ScopeMy things are both off-cuts from my work for Big Finish Productions. First, there's Survivors, an initial sketch outline I wrote in December 2009 about what might happen next to companion Sara Kingdom (Jean Marsh) after the events of my trilogy of stories,

Home Truths

, The Drowned World and The Guardian of the Galaxy, including the incarnation of the Doctor I would have paired her up with.

I very nobly gave a couple of things to Time Scope, a new unofficial and unauthorised anthology of Doctor Who stories, poetry and art - 100% of the money from which is going to the charity Scope. It's edited by Matthew Rimmer.Buy Time ScopeMy things are both off-cuts from my work for Big Finish Productions. First, there's Survivors, an initial sketch outline I wrote in December 2009 about what might happen next to companion Sara Kingdom (Jean Marsh) after the events of my trilogy of stories,

Home Truths

, The Drowned World and The Guardian of the Galaxy, including the incarnation of the Doctor I would have paired her up with.Then there's the pre-title sequence I wrote for my first draft of The Mega, a six-episode story based on an original outline from 1970 by Bill Strutton (writer of 1965 TV story The Web Planet). At the time, the plan was to record The Mega using just three actors: Katy Manning (who played companion Jo Grant onTV), Richard Franklin (who played UNIT’s Captain Yates) and John Levene (UNIT’s Sergeant Benton). Around the time I was commissioned for this, news came of the sad death of Nicholas Courtney - who'd played UNIT's Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart on TV - and in my first audio play. I wanted to acknowledge his loss as well as set up the framing of the story, so wrote this opening scene. Then things changed and it no longer fitted.

Time Scope also includes contributions from both Katy Manning and Richard Franklin, as well as a number of other cast and crew from the various decades of Doctor Who.

Published on July 08, 2020 02:59

July 3, 2020

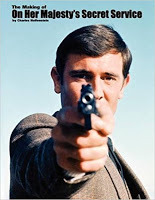

The Making of OHMSS, by Charles Helfenstein

I've long coveted this huge, exhaustive history of the James Bond film On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969), having first heard about it from my mate Samira Ahmed. Helfenstein details the history of the book, the drafts of the script, the day-by-day production on the movie (and pieces together some missing scenes), the release and legacy - including promotion and merchandise.

I've long coveted this huge, exhaustive history of the James Bond film On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969), having first heard about it from my mate Samira Ahmed. Helfenstein details the history of the book, the drafts of the script, the day-by-day production on the movie (and pieces together some missing scenes), the release and legacy - including promotion and merchandise.It is chock full of extraordinary images and insight. I shall be haunted by writer Richard Maibaum's obsession with scenes involving monkeys, which he tried to get into various Bond films and was thwarted each time. The material filming on 2 February 1969 of Lazenby chasing a villain down the Peter's Hill steps with the St Paul's Cathedral behind him echo the invasion by Cybermen, filmed on 8 September the previous year; the conclusion of the chase involving an underground train seem finally to have surfaced in Skyfall (2012).

My baby brother, who kindly bought this for my birthday, described it as the "Andrew Pixley of Bond", and I can think of no higher praise. I think the difference between Helfenstein and Pixley is that the latter rarely interviews cast and crew himself - thank heavens, as otherwise I'd never be asked to do anything. Helfenstein has endeavoured, over years, to speak to everyone involved and the book is a much a record of his friendships with key personnel such as director Peter Hunt. A last spread of images of the author with these people or visiting the locations shows how much this has been an epic labour of love.

If I don't share the author's passion for this particular movie, it's made me want to revisit it. I'm even more covetous of the follow-up volume on The Living Daylights and find myself picking over which title I'd want to subject to such study...

(Since you're asking, You Only Live Twice to cover Connery's dissatisfaction, the volcano-base set and all the stuff happening in '67, which would dovetail with my book on The Evil of the Daleks.)Me on the novel On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1963)

Published on July 03, 2020 07:15

July 2, 2020

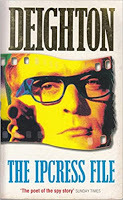

The Ipcress File, by Len Deighton

I'm immersed in the world of Harry Palmer at the moment for a thing I'm writing. That's included finally getting round to The Ipcress File (1962), the novel that inspired the brilliant film.

I'm immersed in the world of Harry Palmer at the moment for a thing I'm writing. That's included finally getting round to The Ipcress File (1962), the novel that inspired the brilliant film.The book is surprisingly different, including trips to Beirut and a Pacific island to watch the testing of a nuclear bomb. Harry Palmer isn't even in it, as the anonymous narrator tells us on page 34:

"Now my name isn't Harry, but in this business it's hard to remember whether it ever had been."In the film, Palmer is played by Michael Caine, a Londoner born in 1933. Not-Harry in the book is from Burnley - completely changing how he'd sound - and perhaps a decade older, as we're told he was in the fifth form in 1939.

Despite the excursions abroad, the plot is basically the same, with the same mix of drab bureaucracy and imminent danger of death. There's the brilliant twist when the agent escapes from incarceration and discovers it's not been quite what it seems - which is so good I don't want to spoil it here, nearly 60 years after the book was first published.

But my general feeling is that the book is a poor relation to the film. The screenplay condenses the story, reducing the scale but making more focused, quicker-moving and sharper. Even minor characters in the movie are memorable - such as Tony Caunter's non-speaking American agent, a big guy with a distinctive glasses, a plaster over the bridge of the nose. The two men who stand out, I think, are the ones who are kind to our narrator in his hour of need. (He makes sure to pay them for their kindness.)

So I'm a bit surprised by the cover line on my battered second-hand copy of the book from 1995 the Sunday Times calling Deighton, "The poet of the spy story." Surely that's a better description of le Carre, whose prose is so much more beautiful than this clunky stuff. It's fine, it's fun enough, it's got some great moments... But the film is witty, stylish, and so classy that it holds its own against Bond.

Published on July 02, 2020 11:28

June 7, 2020

Peaks and Troughs, by Margery Mason

Subtitled "Never Quite Made It But What The Hell?", this is a memoir by Margery Mason (1913-2014), the actress I knew best for shouting "Boo!" in The Princess Bride, though the blurb makes a deal of her having been "trolley lady" in the Harry Potter film The Goblet of Fire.

Subtitled "Never Quite Made It But What The Hell?", this is a memoir by Margery Mason (1913-2014), the actress I knew best for shouting "Boo!" in The Princess Bride, though the blurb makes a deal of her having been "trolley lady" in the Harry Potter film The Goblet of Fire.Mason begins with her 90th birthday in 2003 - though a letter from 2005 pasted into my second-hand autographed copy says,

"In fact I wrote a lot of the book some ten years ago and then I looked at it last year and thought, no, it's too literary; I want it to sound as if I'm talking."It does. She's immediately engaging, bubbling with energy, enthusiasm and self-effacement, while keen for her next job. Mason, we're told, learned to scuba-dive in her 80s, and was competing in tennis matches until around the same time, while her anecdotes about performances all round the world are peppered with notes on the opportunities afforded in these far-flung locales to swim outdoors. She was also an active member of the Communist Party, an (she says herself) ineffective member of Equity, and wrote, directed and produced as well as acted.

Mason admits she's always keen on getting a laugh, and this fun, lively memoir often breezes over events that must have been hard at first-hand. There is a lot of casual groping in her early life - from an uncle, from a stranger on a train, from strangers when she's working for ENSA in Egypt, and from two successive therapists, one male and one female. She brushes over details of a rape during the Second World War, mentioning it only to mitigate her impatience years later when an assault means another actress misses some rehearsals. The sense is that his fun, funny woman was also ruthless and unrelenting to work with.

Of all the stories and revelations, I was most struck by the mention of Patrick Troughton, who played her husband in A Family at War between 1970 and 1971, the series recorded in Manchester.

"Patrick and I used to share driving up and down [from London] on weekends and he seemed confident enough with me, perhaps because he was a bit of a speed merchant himself, never able to resist doing the ton on a certain bit of motorway. We were pulled over by the police once in my car, not for any offences but because they were doing some sort of check. The dodgy thing was that among the luggage I'd flung onto the back seat was a large transparent plastic bag of marijuana. Pat had asked me to get some for him and although I'd long given up any hope of having it work for me I could still get hold of it easily enough - well everybody could. Pat had forgotten it was there so was quite happy to respond to the officers' excited recognition of him as an ex-Doctor Who. 'Come on Pat, we're late already' I said, frantically looking round for something to throw over the bag. But they were still burbling on with 'Who was the chap who took over from you? The one with all the hair?' Finally I put the car in gear and we were nearly on our way when, 'Just a minute, just a minute.' (Oh God!) 'Did you say you came from London? Can I see your licence?' 'What? Why?' 'You're sure you're not from Luton?' 'Luton?' 'I live there. I'm sure I've seen you around.' 'I've never been to Luton in my life. I live in London. I'm an actress. I'm Mrs Porter, for God's sake!' 'Who?' 'Pat, tell him. We'll never get away. Tell him!' Pat did, but it so happened he didn't watch A Family at War so we left him only half-convinced I wasn't a secret denizen of Luton. He'd been a great Dr. Who fan though and thought Pat was the best of the lot, so one of us was happy and Pat later said he'd had quite a good time with the pot." (pp. 68-9).Mason then proceeds to regale us with anecdotes about her much more effective experimentation with LSD.

As with Yootha Joyce and David Whitaker, Mason was with the Harry Hanson Court Players - in her case, on and off for 10 years from. She speaks of Hanson's "fondness for 'Anyone for tennis?' type plays" (p. 32), but counters the idea that weekly rep taught bad habits because there was little time for background research or navel-gazing (something she has little patience for anyway).

Short of work, between 1947 and 1948, Mason wrote her own play. Because "one of the characters had lesbian leanings", she had to go for a meeting at the censor's office. However, club theatres were exempt from the censor, so her play was put on at Oldham - where she'd been in rep alongside a very young Bernard Cribbins. You can still feel her pride more than half a century on:

"Sitting in an audience and hearing your lines get the laughs you'd hoped for takes a lot of beating." (p. 51)Soon after this, Mason wrote and produced Babes in the Wood, a pantomime, and having made money from it dared to apply to run a summer season of rep in Bangor. This was just as her husband absconded with the money from their joint account, and she gives a good account of the struggles that followed.

"I put on the play Oldham had done, trusting the long arm of the censor didn't stretch to Ulster, and another one I'd hastily finished, happy, like Clem [her later mother, also an actress and sometime writer] in the past, to save on royalties [to other authors]." (p. 54)With the 10-week season a success, Mason then established the New Theatre in Bangor, and ran it for 15 months.

She says in the book that this time in Bangor was in the 1960s, but my other research says that the opening night of the New Theatre in Bangor was on 4 October 1954, with the comedy For Better or Worse about a newly married couple. Mason produced and also played the bride's mother. Her husband was played by 26 year-old David Whitaker, who'd been with the Harry Hanson Court Players himself since 1951.

In the six months or so that Whitaker was in Bangor with Mason, he also produced (that is, directed) three of the productions and seems also to worked in radio serials in Northern Ireland - his first broadcast work, as far as I can tell. The energetic, enthusiastic Mason may also have encouraged him to write as well - for one thing, he was in the cast of a remounted version of her Babes of the Wood.

Within a year of leaving Bangor, Whitaker was co-writing with his mum Helen, and she made first contact with the BBC to get their work on screen. The following year, in 1957, Whitaker was performing with the York Repertory Company, who also staged his play A Choice of Partners. A member of the BBC's script unit was in the audience and the play was subsequently adapted for TV. By the end of the year, he'd given up acting to join the script department for three months. He was still there in 1963 when the department was closed down - and he was moved on to Doctor Who.

Mason doesn't mention Whitaker or anyone else in the Bangor company by name. So my hopes that she would acknowledge her influence on him were disappointed. But I read her book in a single sitting, caught up in her vivacious, steely energy - so how could he have not been?

Published on June 07, 2020 10:19

June 6, 2020

Dear Yootha..., by Paul Curran

This is a 2014 biography of the actress Yootha Joyce (1927-80), best known as alpha-cougar Mildred Roper in the 1970s sitcoms Man About the House and spin-off George and Mildred. As a fan, Curran has sieved through a wealth of material and spoken to what feels like anyone who ever knew or worked with Joyce. The result is exhaustive.

This is a 2014 biography of the actress Yootha Joyce (1927-80), best known as alpha-cougar Mildred Roper in the 1970s sitcoms Man About the House and spin-off George and Mildred. As a fan, Curran has sieved through a wealth of material and spoken to what feels like anyone who ever knew or worked with Joyce. The result is exhaustive.I was especially interested in Joyce's early life and career to see if I could overlap anything with that of David Whitaker (1928-80) - writer and story editor of significant bits of 1960s Doctor Who, whose life I'm slowly piecing together. In a 1986 interview, Whitaker's first wife June Barry (who sadly died last month after long illness) claimed that Whitaker had been "almost engaged" to Joyce.

Joyce and Whitaker were born a year apart and both grew up in London - but she was in Hampstead, Clapham and then Croydon, while he was in Barnes and then Kensington. Joyce attended RADA (in the same class as Roger Moore), while Whitaker went into accountancy, where he did amateur dramatics through Sedos. In the early 1950s, Joyce and Whitaker were both in professional repertory with the Harry Hanson Court Players - but for different companies, in different parts of the country. Joyce met Glynn Edwards in the summer of 1955 and married him the following year, so if she and Whitaker were ever together it must have before then - but as Curran says in the book we don't know much about this time in her personal life. (He's also been kind enough to respond to my inquiries and say that nobody he's spoken to about Joyce ever mentioned Whitaker's name.)

Even if this connection remains a mystery, Curran is good on the kind of theatrical world Joyce and Whitaker were both part of at that time. There's the glamour of showbiz:

“Whatever their background, Harry Hanson was known to pressure his actors to always appear glamorous, on and off stage. This filtered through to the other associated Harry Hanson companies.” (p. 28)There's the pretensions of the material performed twice-nightly for six nights a week:

[From an interview with Dudley Sutton] “But up until [Joan] Littlewood’s appearance, the English theatre was completely middle-class. It was run by the officers, and when an ordinary man or woman come onto the stage, they’d always have to be stupid, comic or both." (p. 34)And all of this under the condescension of the state:

[From an interview with Glynn Edwards]: “Of course you had the Lord Chamberlain’s rulings, where you were only allowed to say ‘bloody’ twice.” (p. 30)There's a horrible irony in what follows. Joyce escaped this kind of safe, sentimental theatre for bolder, more experimental stuff that dared to base itself in lived experience and to get political and sexy. Curran underlines the breadth of the work she was doing in the 1960s, from Littlewood's abrasive theatre to episodes of The Avengers and The Saint. Indeed, Mildred Roper is a bold character for her time - sexually assertive, frustrated, real, and immediately connecting to the audience. But the role overshadowed her life, and limited her options in an age of type-casting.

The last section of the book, detailing her sudden decline and death from alcoholism at 53, is hard going not least because there's a sense that it's the success of Mildred that killed the woman who played her. But Curran is shrewd in closing with a poignant last appearance, on Max Bygraves' show Max, screened after her death, where Joyce performed a song that seems to reveal something of what she was feeling in those last days. As Curran says, that made an impression on Kenneth Williams, who was haunted by it ever after:

"Years later, on 9th April 1988, not long before his own death, he added [to his diary] 'can't get Yootha Joyce out of my head - and the time she sang 'For All We Know', there was almost a break in the voice when she got to [the line] tomorrow may never come, but she carried on. She died shortly after [recording it]. A lady who made so many people happy and a lady who never complained." (p. 164)It's as if, I thought, even after death she could produce the goods: a role that was moving, surprising and real.

(You might like to know that Joyce's co-star Brian Murphy was in a Doctor Who story I wrote, released last year.)

Published on June 06, 2020 11:14

June 3, 2020

Doctor Who: Lesser Evils

Big Finish have announced Lesser Evils, a short audio story written by me and performed by Jon Culshaw, which will be released for download in October. The artwork, right, is by the amazing Anthony Lamb.

Big Finish have announced Lesser Evils, a short audio story written by me and performed by Jon Culshaw, which will be released for download in October. The artwork, right, is by the amazing Anthony Lamb."The Kotturuh have arrived on the planet Alexis to distribute the gift of the death to its inhabitants. The only person standing in their way is a renegade Time Lord, who has sworn to protect the locals. A Time Lord called the Master..."The release is paired with Master Thief by Sophie Iles, who had to suffer me as editor, and it's all part of the Time Lord Victorious cross-platform extravaganza wossname.

The Short Trips range gave me my first professional gigs as a writer of fiction, way back in 2002. Here's a list of my previous Short Trips stories. My very first one, The Switching, also features the Master and is being included in the special edition Masterful in January 2021.

[image error]

Published on June 03, 2020 03:28

May 29, 2020

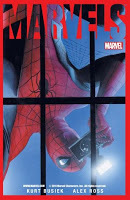

Marvels, by Kurt Busiek and Alex Ross

After my post on Kingdom Come, a shrewd friend recommended me Alex Ross's earlier work, Marvels, originally published as a four-part mini-series in 1994. Written by Kurt Busiek, Marvels revisits apparently well-known events from Marvel Comics storylines, but from the perspective of an ordinary human. Phil Sheldon is an ambitious news photographer, torn between wanting to be an active participant in history and the debilitating sense that superheroes leave the rest of us impotent.

After my post on Kingdom Come, a shrewd friend recommended me Alex Ross's earlier work, Marvels, originally published as a four-part mini-series in 1994. Written by Kurt Busiek, Marvels revisits apparently well-known events from Marvel Comics storylines, but from the perspective of an ordinary human. Phil Sheldon is an ambitious news photographer, torn between wanting to be an active participant in history and the debilitating sense that superheroes leave the rest of us impotent.It's a brilliant idea, beautifully presented with high quality painted artwork on high quality paper. The endnotes show how cleverly the plot weaves between events established in decades-worth of comics - though much of this stuff was new to me, a sporadic comics reader. More telling, I thought, was the way the story acknowledges the contradictions in the history: Human Torch and Sub-Mariner battle as mortal enemies, then are friends, then battle Nazis together, then battle one another again when Sub-Mariner for some reason turns on humanity... I guess readers - fans - familiar with the original stories would know what occasioned these abrupt switches of loyalty and motive, but Sheldon's distance from the heroes means it is here left unexplained.

Sheldon never gets close to his marvels - there's no exclusive access as when Lois Lane interviews Superman, or when Peter Parker tells us what Spider-Man is really like. The closest encounter, when Sheldon is near Spider-man at the time of Gwen Stacy's death, is still at a remove. The result is that for all the years he studies them, the heroes remain out of reach, aloof, and Sheldon can offer little insight or perspective.

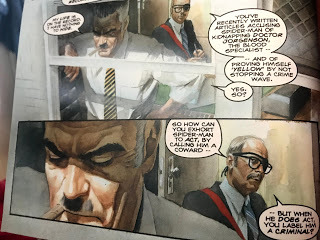

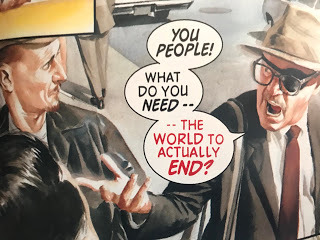

That is probably the point. At the human level, Sheldon can intercede, such as when he calls out the hypocrisy of the newspaper editor Jonah Jameson from the Spider-Man stories:

Or there's the moment he turns on the population of New York for their (and his own) fickleness, praying for salvation in times on crisis and then turning on the superheroes the moment danger has passed. What with everything at the moment, the following panel struck a chord:

That feels just as real and innovative for the medium as the extraordinary artwork, and I can understand the impact Marvels had on its original release. Stan Lee, no stranger to hyperbole, speaks in his foreword of it being, "a new plateau in the evolution of illustrated literature" - that last word a claim to respectability, high art, the canon.

Such pretensions are of their time. Marvels is solemn and portentous in that 1990s comics way. The engaging, playful wit of the Marvel movies is seriously lacking. It's an impressive, arresting accomplishment, but feels more DC than Marvel.

Published on May 29, 2020 03:36

May 24, 2020

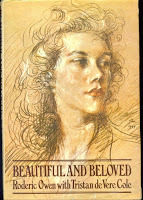

Beautiful and Beloved, by Roderic Owen and Tristan de Vere Cole

On twitter a few weeks ago, a friend mentioned that Tristan de Vere Cole, director of 1968 Doctor Who story The Wheel in Space, was not only the son of Mavis Mortimer Wheeler but also co-wrote a biography of her. I sought out the book.

On twitter a few weeks ago, a friend mentioned that Tristan de Vere Cole, director of 1968 Doctor Who story The Wheel in Space, was not only the son of Mavis Mortimer Wheeler but also co-wrote a biography of her. I sought out the book.Back in 2011 I was much struck by a sketch of Mavis in the National Museum of Wales by Augustus John - believed to be Tristan's father. At the time I saw the portrait, I was reading Michael Holroyd's exhaustive, 600-page biography of John, and followed that up with Mortimer Wheeler's autobiography Still Digging - though in that Wheeler makes no mention of his second wife at all - though it was over Mavis that John famously challenged Wheeler to a duel; Wheeler consented, suggesting they fight it out with field guns.

Things never got that far, the quarrel was settled, and John was best man to Wheeler when he married Mavis - a newsworthy event given that Mavis was sister-in-law to the Prime Minister (her late husband's sister was Mrs Neville Chamberlain):

Beautiful and Beloved certainly doesn't shy away from that mix of celebrity, sex and wild goings on. Much of the later part of the book details the events of 1954 when Mavis shot her lover, Lord Vivian. A range of sources are used to piece together the night of drinking that led up to the shooting, the shooting itself - as best it can be understood - and the subsequent trial. The authors are in no doubt of Mavis' innocence - yes, she shot Lord Vivian, but they're sure she didn't mean to hurt or kill him. Despite this, the four different versions of events given by Mavis that suggest she wasn't entirely honest about what happened. They seem surprised that she went to prison for it but I didn't think there was much reasonable doubt.

In fact, Mavis' different accounts of herself were nothing new. Born Mabel Winifred Mary Wright on 29 December 1908, Mavis kept reinventing herself, changing her name to Mavis and then Maris, with other names such as Faith and Xara along the way. She was also horrified that news reports of her trial gave her real age. That constant reinvention helped her escape her modest background - she was the daughter of a grocer's assistant, and worked as a scullery maid and waitress before she met and married society prankster Horace de Vere Cole. He was much older than her and had already lived quite a life: the book includes a photograph of a blacked-up Virginia Woolf alongside Horace as part of the notorious Dreadnought hoax in 1910 (when Mavis was aged just one). By the 1960s, Mavis has risen so high through the social ranks that she could accuse her daughter-in-law of being bourgeois - for not being classy enough.

The book shares details of Horace's other pranks, but doesn't tell us exactly which rude word he contrived to spell out in the audience of a theatre by buying tickets for a bald-headed men. That's not from prurience. For one thing, details are sparse for this particular legend: Wikipedia says it was either BOLLOCKS or SHIT but can't name the performance, either. For another, the book isn't shy of f-words and c-words when it quotes the endless, bad poetry Mavis inspired from her various lovers. Or there's this, about John in 1957:

"To Mavis he wrote about an exhibition of drawings he was thinking of having, drawings of what a convention of the day would have had him refer to , in print, as c--s; but such evasions were not for him. He warned her that he would shortly be calling on her to provide the crowning feature of the lot, and he sent love from himself and [his partner] Dodo for good measure.The book is strikingly candid, and includes one of the nude photographs she sent to John in the 1930s. In fact, she sent such photographs to at least one other of her lovers - and each time the photographs were returned with a horrified response. John wanted to know who had taken the pictures and how she'd got them developed, and the authors add a footnote about practicalities here:

He wasn't just being shocking, in the time-honoured, intimate manner. John was known to have made a number of studies of private parts. And since Mavis came so easily to hand he was bound to have used as a model, even after a lapse of so many years, the girl who'd won the competition at the old 'Eiffel Tower' [restaurant] for the finest concealed charms." (p. 257)

"It wasn't until August 1972 that the Boots chain consented to develop and print snapshots showing full frontal nudity. 'The interpretation of what is obscene has changed in the minds of juries and public opinion,' stated their spokesman, quoted in the Daily Telegraph. 'A normal naked woman is not obscene." (p. 78n)The obvious candidate for photographer is Bet, the "local and very Cornish woman" who looked after Doll Keiller's cottage at Woodstock St Hilary near Marazion in Cornwall, where Mavis stayed while pregnant with Tristan in December 1934. We know Bet was taken by Mavis on first sight:

"But rushed round to spread the news [of the arrival] to her neighbour, Mrs Allan. 'You wait 'til you see what's in my cottage,' she boasted. 'Six foot of beauty, that's what I've got.'She's back in Cornwall with Bet in 1958, though Doll had died three years before:

But even Bet was taken aback when Mrs de Vere Cole opened the door to her next morning, completely naked. 'Look here, Bet, you'll have to get used to this,' said Mavis. 'You'd better begin now.' Even in December, if she could remove her clothes, she would." (p. 72)

"They took photographs. On returning to London she [Mavis] prevailed upon a manager to co-operate. She wrote to Bet, 'I told him that some were taken unawares, when I was getting out of my bikini. "Oh," says he, "I'll attend to the matter myself and will get them through by Saturday morning." So--Bet--what fun!" (p. 260)For all the detail of the letter, the dates and the brazenness, for all the honesty of the book, I find myself wondering what her relationship was with Bet.

Yet given her vivacity, the image of Mavis that really struck is the one from the opening chapter: in the last year of her life, in 1970, venturing out each day into the streets around Sloane Square with her Yorkshire terrier in her shopping basket, to buy tins of cheap food and a half-bottle of either whisky or brandy (or, sometimes both). This daily intake procured, we follow her back to her home in Cadogan Estates, dirty and full of junk as well as a stack of valuable pictures by John, the plumbing not always working, a huge mirror by the bed. It's tragic but honest, and this version of herself is entirely her own creation.

Published on May 24, 2020 04:38

May 23, 2020

An Unearthly Child takes place on a Tuesday

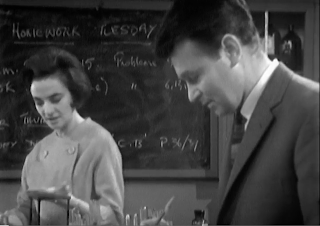

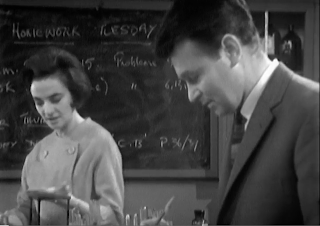

I've just rewatched An Unearthly Child, the very first episode of Doctor Who, and noticed something I don't think I've noticed before. On the blackboard in Ian Chesterton's room, it says "HOMEWORK TUESDAY".

Below this, in the bottom-right corner of the blackboard, it says "FOR THURSDAY":

So the homework has just been set, and the episode takes place on a Tuesday.

We can narrow things down a bit further. In the second episode of Doctor Who, Ian says that he and the others were just, "in a junkyard in London in England in the year 1963."

When in the year might this be? The episode was broadcast on Saturday 23 November 1963, and recorded in studio on Friday 18 October, but that doesn't necessarily tell us when the events depicted are set. But the daylight depicted - or not - in the episode can give us a clue.

In the first episode, it's dark by the time Susan reaches the junkyard after the end of her school day. It is dark enough inside the yard - which is open to the sky - that both Ian and the Doctor use torches. What time did it get dark?

Before leaving school, Susan tells her teachers, "I like walking through the dark," which implies it is already dark. The episode also begins with a policeman walking through the already dark lane outside the junkyard, picking out details with a torch; we then dissolve to the school just as the final bell rings. The implication is that the dissolve transports us in space but not in time - that it is already dark enough to need torchlight before the end of the school day.

But schools usually finish mid-afternoon and, as I know from collecting my own children, it's not dark at the end of the school day, even in the midst of winter. I checked at timeanddate.com, and the earliest sunset in London predicted for December 2020 is 15:51 - the sunset between 8 and 16 December.

The ringing of the school bell suggests that Susan hasn't stayed later than the end of the school day, for example at an after-school club. So if An Unearthly Child is set on a Tuesday in London 1963 where it's (almost) dark by 3.30, it must be 10 or 17 December.

In other words, the first episode of Doctor Who is set a little in the future.

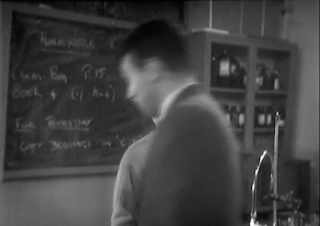

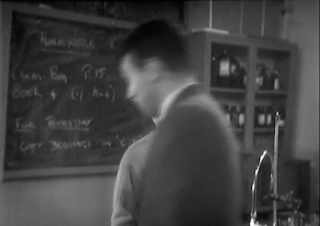

PS: the broadcast version of An Unearthly Child was not the first version made. The earlier, "pilot" episode, included on the DVD, was recorded on 27 September - and there the blackboard is blank:

PPS: 1988's Remembrance of the Daleks returns to the school and junkyard in 1963, and a calendar on the wall in the school says November - but its broad daylight at tea-time, which doesn't seem quite right. 2013's The Day of the Doctor suggests that Totters Lane and the junkyard are in the immediate vicinity of the school.

Below this, in the bottom-right corner of the blackboard, it says "FOR THURSDAY":

So the homework has just been set, and the episode takes place on a Tuesday.

We can narrow things down a bit further. In the second episode of Doctor Who, Ian says that he and the others were just, "in a junkyard in London in England in the year 1963."

When in the year might this be? The episode was broadcast on Saturday 23 November 1963, and recorded in studio on Friday 18 October, but that doesn't necessarily tell us when the events depicted are set. But the daylight depicted - or not - in the episode can give us a clue.

In the first episode, it's dark by the time Susan reaches the junkyard after the end of her school day. It is dark enough inside the yard - which is open to the sky - that both Ian and the Doctor use torches. What time did it get dark?

Before leaving school, Susan tells her teachers, "I like walking through the dark," which implies it is already dark. The episode also begins with a policeman walking through the already dark lane outside the junkyard, picking out details with a torch; we then dissolve to the school just as the final bell rings. The implication is that the dissolve transports us in space but not in time - that it is already dark enough to need torchlight before the end of the school day.

But schools usually finish mid-afternoon and, as I know from collecting my own children, it's not dark at the end of the school day, even in the midst of winter. I checked at timeanddate.com, and the earliest sunset in London predicted for December 2020 is 15:51 - the sunset between 8 and 16 December.

The ringing of the school bell suggests that Susan hasn't stayed later than the end of the school day, for example at an after-school club. So if An Unearthly Child is set on a Tuesday in London 1963 where it's (almost) dark by 3.30, it must be 10 or 17 December.

In other words, the first episode of Doctor Who is set a little in the future.

PS: the broadcast version of An Unearthly Child was not the first version made. The earlier, "pilot" episode, included on the DVD, was recorded on 27 September - and there the blackboard is blank:

PPS: 1988's Remembrance of the Daleks returns to the school and junkyard in 1963, and a calendar on the wall in the school says November - but its broad daylight at tea-time, which doesn't seem quite right. 2013's The Day of the Doctor suggests that Totters Lane and the junkyard are in the immediate vicinity of the school.

Published on May 23, 2020 06:44

May 21, 2020

Turned out nice again in the Lancet Psychiatry

The June issue of medical journal the Lancet Psychiatry includes my essay on David Storey's play Home. You need to pay to read the whole thing, but the first paragraph goes like this:

The June issue of medical journal the Lancet Psychiatry includes my essay on David Storey's play Home. You need to pay to read the whole thing, but the first paragraph goes like this:"50 years ago, on June 17, 1970, the Royal Court theatre in London (UK) debuted Home by David Storey. This “sad Wordsworthian elegy about the solitude and dislocation of madness and possibly about the decline of Britain itself” (according to the Guardian) won the Evening Standard Drama Award and, after transferring to Broadway, the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award for Best Play. In January, 1972, BBC One broadcast a version featuring the original cast, and there were soon productions in the Netherlands, Germany, and South Africa and it is still often revived—a huge success for a small-scale and understated drama..."Here's the BBC version with the original stage cast: Ralph Richardson, John Gielgud, Dandy Nichols, Mona Washbourne and Warren Clarke:

Published on May 21, 2020 02:03

Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers

Simon Guerrier isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.