Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 15

July 3, 2024

Swan Song, by Edmund Crispin

"There could be no doubt, thought Adam, that the death of Edwin Shorthouse was not much regretted by Peacock or anyone else connected with the production. Adam said as much to Fen.

'I know,' said Fen. 'It seems positively indelicate to be trying to discover his murderer.'" (p. 113)

After the events of The Moving Toyshop - or, chronologically, after the events of Holy Disorders since we're told on page 20 of this book that "the business about a toyshop" was "before the war" - the fourth Gervase Fen is another fast-moving, breezily witty adventure. This time, the mystery centres round a new performance of Wagner's Die Meistersinger, the first since the war and with a disquiet about staging work so beloved of the Nazis. We meet the various operatic characters involved in the opera. Then, just as in The Case of the Gilded Fly (where it was the company in a theatre), one of the most odious of this cast ends up dead.

This time, the death looks like suicide but Fen is not so sure, and the attempted rape of one woman, the attempted murder of another and the sudden death of a man are all tangled up in the case. I think it's all a lot better structured than previous instalments, not least in that Fen takes his time to puzzle out what's gone on rather than sussing it early and then declining to share his deductions.

There's some confounded cheating - on page 189, Fen causes quite a stir (for the characters and this reader) when he announces that one person killed both the dead men. That person doesn't immediately deny it and we're led to believe they are guilty, only for Fen to then unravel what really happened and how this person is in fact innocent.

There's also something uncomfortable in the treatment of young Judith Haynes, the victim of the attempted rape, both in the immediate aftermath of that and what happens later. I don't think it's very well handled, and it also doesn't sit well in what's otherwise a light, comic novel centred on an ingenious double-puzzle.

The adventure and comedy otherwise work very well. Wilkes the old rogue from The Moving Toyshop making a welcome return to further confound Fen's deductions just for the fun of it. And I loved the unnamed burglar who turns up at an opportune moment to help the sleuth break into a smart house.

"'Doesn't look to me,' said the little man disapprovingly, 'as if there's anything worth pinchin' 'ere. What we want is socialism, so as everyone'll 'ave somethink worth pinchin'." (p. 182)

June 29, 2024

Is that you, Maureen?, by Jeremy Swan

This is a sharp, funny memoir by someone behind a glut of much loved children's TV, including Jackanory, Rentaghost and Round the Twist. It's available for pre-order and published on 29 July but I got to read it early so as to compile the index.

This is a sharp, funny memoir by someone behind a glut of much loved children's TV, including Jackanory, Rentaghost and Round the Twist. It's available for pre-order and published on 29 July but I got to read it early so as to compile the index.Swan's life and career makes for an extraordinary, enjoyable read. How fantastic to learn that the producer of Galloping Galaxies also worked on The Spy Who Came in From the Cold. Working on this has been a pleasure; but the fact I worked on it excludes me from offering a review.

So, instead, an observation as a stable mate. I particularly enjoyed the way that, by chance, this new book overlaps with others already published by Ten Acre Films. Swan worked closely with Biddy Baxter and got sacked from his one day on early Doctor Who. He took the BBC's directing course and remained good friends with Andrew Morgan, who directed two of Sylvester McCoy's adventures in time. And he worked with several people who feature in my book on David Whitaker, such as producer Chloe Gibson.

You can buy Is that you, Maureen? from the Ten Acre Films website.June 21, 2024

The Life and Times of a Doctor Who Dummy, by Robin Squire

New David Whitaker related information!

New David Whitaker related information!This short memoir by Robin Squire was recommended to me by Doctor Who assistant location manager Alex Moore, who I quizzed for Doctor Who Magazine last year. I knew Squire's name as, in 1981 story Logopolis, he plays the technician at Jodrell Bank* too busy listening to music to notice a TARDIS materialise behind him. He's also credited for small roles in The Daemons (1971) and Full Circle (1980).

Before these credited roles, Squire spent some four months as a trainee script editor in the Doctor Who production office - and kept a diary. His book recounts the period 1965-69, beginning with his backpacking trip across France where he saw the Beatles play a gig in Nice on 30 June 1965. As he says, Beatles histories can tell us the set list played that night but he can add extra detail, such us what the warm-up acts were and how the audience responded (p. 36).

Based on this gig and then a chance encounter with the former manager of a band, Squire wrote a novel about a band, Square One, published on 5 August 1968. At the time of publication, his wife had just given birth and Squire went for a pint with a neighbour whose wife was on the same labour ward. That neighbour was Terrance Dicks, who a few months later told Squire about a short-term trainee job going in his office at the BBC.

So, from the end of June to early November 1969, Squire was based at a desk in room 505 on the second floor of Union House, Shepherds Bush Green - and the home for nearly 27 years of the Doctor Who production office. Arriving for his first day at the “surprisingly late hour of 10 am”, Squire was met on the main door by a “uniformed commissionaire” (p. 71) and instructed to, “Take the lift to second floor. Third door on the left.”

There he found a, “small and dusty-seeming office,” with Dicks “behind a desk to the right, beside the window looking out over the Green ... To my right was an open door leading through to the producer’s office.” Peter Bryant shared that office with production secretary Sandra Brenholtz, whose job involved “all the correspondence” as well as “typing out scripts and production schedules and the Lord only knew what else on an electric typewriter” (p. 72). The producer’s desk was bigger than his secretary's and behind it was a “huge white plastic chart on which was written in black marker pen the forthcoming programmes, with studios times and dates, director, writer and so on” (pp. 72-3). Squire turned up for his first day in a suit; Dicks, in jeans and open-necked shirt, told him not to do that again.

Dicks then walked Squire round the corner to Lime Grove Studios - though Doctor Who was no longer made there (the last Doctor Who made there was the first episode of The Space Pirates, recorded in February). There they bumped into Patrick Troughton - even though, as Squire says, he'd recorded his last scenes as the Doctor a week or so previously. They also saw the TARDIS set, presumably in storage. Squire says it looked “tatty and worn ... Terrance said that on a black and white monitor the well-worn aspect didn’t show, but when transmission changed to colour early next year, it would.”

Soon enough, Squire attended filming on Spearhead from Space, the first Doctor Who to be made in colour. He was initially there as a spare body but got roped into playing an Auton and later worked as the unit driver, for which he had to take the BBC's own driving test. There's lots of detail here - dates he was and wasn't on location, the name of the hotel where the principal cast and crew were based and the names of its landlords, what was involved in shooting on location and what it felt like to be in that costume. We're told what he got up to on his day's off and what music was playing on the radio, which he still associates with that period.

This all helps conjure a richer, fuller picture of what went on than we get from the production paperwork in the BBC's written archive. Yes, I have alerted David Brunt about this for when he gets to the relative volume of his production diary.

On one occasion, script editor Derrick Sherwin showed Squire a script for something other than Doctor Who - probably Project Air One, on which he was working with Peter Bryant at the same time.

That meant he was there as writers came into the office to discuss their scripts for the 1970 series of Doctor Who. Squire recalls meeting Robert Holmes, going to the home of Malcolm Hulke and even devising the storyline given to Don Houghton to write up as Inferno. That leaves one other writer from that year; he mentions David Whitaker in passing on page 81.“But apart from that, and despite apparently being a trainee script editor, I received no training in script editing, but sat at a desk at the side of Terrance’s office where I was given the work of answering letters from fans and followers of the programme.” (p. 75)

“I never met him,” Squire told me yesterday but “there was still talk about David Whitaker.” This was because, as Squire told me unprompted, of David's mission to Moscow in July 1969 on behalf of the Writers' Guild to protest the treatment of Solzhenitsyn, and the storm that followed. As described in my book, David, his wife and colleagues were subjected to poison-pen letters and phonecalls. In 2017, I asked both Terrance Dicks and Derrick Sherwin about this and whether such letters have been received at Union House. Neither of them could remember - but then they'd not been the ones to deal with correspondence.

“At the time I was at the Doctor Who office,” Squire told me, unbidden, “angry messages were continuing to come in along the lines of 'David Whitaker, traitor', for not having spoken up.”

For more details about and to order your own copy of The Life and Times of a Doctor Who Dummy, see Robin Squire's website.

* Yes, Jodrell Bank, as confirmed in Spyfall (2020).

June 20, 2024

Doctor Who Magazine #605

The new issue of the official Doctor Who Magazine is out today. Having hogged loads of the last issue, this time I've contributed one small-ish thing, a Who Crew interview with Sam Dinley, assistant to composer Murray Gold.

The new issue of the official Doctor Who Magazine is out today. Having hogged loads of the last issue, this time I've contributed one small-ish thing, a Who Crew interview with Sam Dinley, assistant to composer Murray Gold.(There was something else, too, but it's being held over...)

June 19, 2024

Follow Your Curiosity podcast #241

I'm interviewed by Nancy Norbeck on the latest episode of the Follow Your Curiosity podcast, which you can find on YouTube and all these podcasty places.

I'm interviewed by Nancy Norbeck on the latest episode of the Follow Your Curiosity podcast, which you can find on YouTube and all these podcasty places.Nancy says:

The Evolving Landscape of AI in the Arts

My guest this week is Simon Guerrier, a writer and producer who has written numerous books related to Doctor Who, produced five documentaries for BBC radio, and more than 70 audio plays for Big Finish Productions, as well as comics and short stories. He also chairs the Books Committee for the Writers' Guild of Great Britain. Simon talks with me about how he got his start in writing and producing—including just what a producer does—the value of negotiating arrangements that work in everyone’s best interest, the impact of new tools like ChatGPT on creative careers and the creative process, his new book about television pioneer David Whitaker, and more.

June 16, 2024

A Bit of Difference, by Sefi Atta

Deola Bello works for a company in London that audits charities and NGOs around the world. She arranges one assignment so that she'll be back in Nigeria in time for the fifth anniversary of the death of her father. But facing her extended family means a whole load of questions - about what she's doing with her life, what she wants and where she belongs...

Deola Bello works for a company in London that audits charities and NGOs around the world. She arranges one assignment so that she'll be back in Nigeria in time for the fifth anniversary of the death of her father. But facing her extended family means a whole load of questions - about what she's doing with her life, what she wants and where she belongs...

Yesterday, I interviewed author Sefi Atta about this 2013 novel for an online event hosted by Macfest. Sefi is a prolific author - of novels, short stories and plays (for both radio and the stage) - but chose this novel as the focus of our discussion.

She told me that she'd consciously endeavoured to avoid the cliches and stereotypes she'd observed at the time of writing, as expressed in the novel by Deola in a conversation with a writer friend.

"African novels are too exotic for her. Reading them, she often feels they are meant for Western readers, who are more likely to be impressed." (p. 190)

These readers seem to be drawn to tales of catastrophe, as the writer friend responds:

"The more death the better. It is like literary genocide. Kill off all your African characters and you're home and dry. They certainly don't want to hear from the likes of me, writing about trivialities like love." (p. 191).

Deola counters that,

"Love is not trivial. ... Love is epic." (p. 192)

For all we might hear, repeatedly, of the danger of "armed robbers" while Deola is in Nigeria, that threat never materialises. In fact, the only armed conflict here is the protests in London to the ongoing Gulf War (the novel set in 2003). There's corruption in Nigeria but that dovetails with the way Deola is treated, belittled and overlooked by her employers in London, who express disappointment that her report based on first-hand experience is not what they wanted to hear.

Instead, the focus here is on the personal: Deola's friendships, her family, a man she meets in Nigeria and what happens between them. In the course of all this, she's wrestling with her sense of self - her identity and future. For all the backdrop of Gulf War (in London) and poverty, AIDS crisis and corruption (in Nigeria), it's a warm, funny novel full of sharp observations because it's all told from Deola's perspective; her character, concerns and passions set the tone.

June 13, 2024

Yellowface, by RF Kuang

Bestselling author Athena Liu asks her friend June Hayward to look over a manuscript she's written using an old, manual typewriter - the only version of Liu's new novel. When Liu suddenly dies, Hayward must decide what to do with a book that no one else knows even exists. The draft isn't good enough in its current state, Hayward decides, so begins to revise it. Soon she's claimed the work as her own and things begin to snowball...

Bestselling author Athena Liu asks her friend June Hayward to look over a manuscript she's written using an old, manual typewriter - the only version of Liu's new novel. When Liu suddenly dies, Hayward must decide what to do with a book that no one else knows even exists. The draft isn't good enough in its current state, Hayward decides, so begins to revise it. Soon she's claimed the work as her own and things begin to snowball...This fast-moving satire of the issues of racial diversity in publishing and on social media kept me entertained as I drove to and from a work thing this week. It reminded me a bit of Patricia Highsmith, the narrator not so much unreliable as unobservant, failing to pick up on things that made me gasp or cringe, often because she's too eager to defend her own actions and motives. She details her own anxiety, triggered by hostile behaviour experienced in person or online, but often misses the impact of her own actions, such as in complaining about a junior member of publishing staff or harshly critiquing the work of a high school student.

Our narrator isn't the only character to behave badly; it's a world of self-interested, prickly people with fixes smiles (in that sense, the other thing it reminded me of was the recent Doctor Who episode, Dot and Bubble). I've seen a few reviews claim Yellowface is too on-the-nose or that June Hayward's character lacks depth - and then miss some elements that are not spelled out. Hayward's relationship with Liu is complex; Liu is complex and sometimes disquieting figure. It's continually, compellingly not straightforward.

June 9, 2024

The Moving Toyshop, by Edmund Crispin (again)

"'Let's go left,' Cadogan suggested. 'After all, Gollancz is publishing this book.'" (p. 87)

It's more than a decade since I first read The Moving Toyshop and, having really enjoyed it then, I'm surprised how little stuck in the memory. One thing was the basic wheeze: Richard Cadogan stumbling drunk into a toyshop to find a dead body, only to return with the police to find the body and the whole toyshop gone. To solve the mystery, he calls on his friend, the eccentric Oxford don Gervase Fen.

Then there's the thrilling final sequence on a merry-go-round, borrowed by Alfred Hitchcock for Strangers on a Train. But sadly, between these two brilliant bookends, there's a lot of running around and literary gags that - though enjoyable - lack the mad and visual heft to linger.

Reading it after the two preceding novels (The Case of the Gilded Fly and Holy Disorders), it's also notable that this third instalment isn't set during the war as they are. We're not actually told when events take place - though the next novel, Swan Song, will reveal that The Moving Toyshop took place before the war and so precedes those two earlier novels.

At one point, while incarcerated and with Cadogan unconscious, Fen amuses himself coming up with titles for further accounts of his adventures:

"'Fen steps in,' said Fen. 'The Return of Fen. A Don Dares Death (A Gervase Fen Story) ... Murder Stalks the University ... The Blood on the Mortarboard. Fen Strikes Back ... My dear fellow, are you all right? I was making up titles for Crispin.'" (p. 81)

Not even halfway through a third book and it's poking fun at the idea of this as a series; Fen established enough to be mocked just as much as anyone else in the literary world.

June 7, 2024

Doctor Who Magazine: Print the Legend

I've just received my contributor copy of the new Doctor Who Magazine special, Print the Legend, which tells the complete story of every Doctor Who novelisation - from Doctor Who in an Exciting Adventure with the Daleks by David Whitaker (1964) to The Church on Ruby Road by Esmie Jikiemi-Pearson (2024). Excitingly, each copy comes with a free Doctor Who audiobook on CD - I got Carnival of Monsters with mine. Result!

I've just received my contributor copy of the new Doctor Who Magazine special, Print the Legend, which tells the complete story of every Doctor Who novelisation - from Doctor Who in an Exciting Adventure with the Daleks by David Whitaker (1964) to The Church on Ruby Road by Esmie Jikiemi-Pearson (2024). Excitingly, each copy comes with a free Doctor Who audiobook on CD - I got Carnival of Monsters with mine. Result!My two bits are:

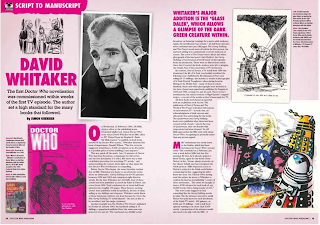

pp. 18-21 Script to Manuscript: David Whitaker

The influences on Whitaker that helps to ensure the Doctor Who novelisations began at such a high standard, with some stuff I've picked up from my research into Garry Halliday as well as a previously unpublished photograph of Whitaker with Vincent Price.

pp. 22-23 The Final Chapter

Details of the Doctor Who related paperwork loaned to me by Whitaker's niece Melanie, including - reproduced in full - the surviving first page of his unfinished novelisation of The Enemy of the World, with permission of Whitaker's estate.

See also my biography, David Whitaker in an Exciting Adventure with Television.

June 6, 2024

Making Sense of Suburbia through Popular Culture, by Rupa Huq

I read this on holiday as research for something I'm working on at the moment. Dr Rupa Huq, MP for Ealing Central and Acton, explores depictions of suburbs in novels, music, films and TV and then devotes a chapter each to woman in suburbia and mapping Asian London in pop culture.

I read this on holiday as research for something I'm working on at the moment. Dr Rupa Huq, MP for Ealing Central and Acton, explores depictions of suburbs in novels, music, films and TV and then devotes a chapter each to woman in suburbia and mapping Asian London in pop culture.“The suburbs are in many ways ordinary,” she tells us on page 13: “according to estimates some 80 per cent of Britons live in them.” (The figure comes from Paul Barker's 2009 book The Freedoms of Suburbia.) That makes them almost universal, and entirely relatable when we see them on screen.

Huq delineates two kinds of suburbia, I think. First there's that idea of crushing, bland ordinariness, a place to be escaped.

“Of recent UK offerings, The Sarah Jane Adventures, a spin-off from the long-running BBC science fiction series Doctor Who, was based in Ealing. Part of the show’s attraction was that such storylines of time travel and aliens could be unleashed in such an unlikely setting as a straight-laced, upstanding and ostensibly boring location.” (p. 130)

That Sarah Jane Smith hails from boring old Ealing (or, in The Hand of Fear, South Croydon) is juxtaposed against her adventures in all of time and space. It's a joke: after all her wild adventures, she ends up somewhere so ordinary.

Ealing is so ordinary and relatable that it could be anywhere - and indeed the Ealing scenes in The Five Doctors were actually filmed in Uxbridge, the Ealing scenes in The Sarah Jane Adventures were recorded in Penarth.

In the very first episode of Doctor Who, the mundane details of ordinary life - a policeman, a junkyard, a comprehensive school - create a credible, relatable frame for the sci-fi wonders that follow. Basically, the first half of the episode feels real so we buy the more outlandish stuff that follows. But again it's following that basic idea: we must leave the ordinary suburbs to go somewhere exciting.

And that's where the second kind of suburbia comes in. Huq quotes playwright Alan Ayckbourn on suburbia:

“It’s not what it seems, on the surface one thing but beneath the surface another thing. In the suburbs there is a very strict code, rules … eventually they drive you completely barmy.” Think of England: Dunroamin’ (BBC Two, 5 Nov 1991, dir. Ann Leslie)

The suburbs are a place on anxiety, the “suburban neurosis” outlined in the Lancet in 1938 by Stephen Taylor, senior resident medical officer at the Royal Free Hospital (and, er, my dad's godfather). Huq also charts similar ideas in Betty Friedan's influential The Feminine Mystique (1963). I can see these same ideas being explored in sitcoms of the 1970s, that sense of the suburb as a place of strangeness and secrets and danger.

In fact, I think The Sarah Jane Adventures and quite a lot of Doctor Who makes more use of this second kind of suburbia, where more is going on that meets the eye. With aliens and time travel and daft jokes aplenty, the whole point is that Ealing - or anywhere else - isn't boring. Which might be of some comfort to the local MP.

Anyway. More of this to come in the thing I'm working on...

Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers