Weston Cutter's Blog, page 7

September 9, 2014

Learning to Build the Best Commune

LEARNING BY DOING AT THE FARM by Robert J. Kett and Anna Kryczka

LEARNING BY DOING AT THE FARM by Robert J. Kett and Anna Kryczka

1960’s. A mixed group of mostly young adults long for the areas of California not yet developed, plots of land never cemented over, fertile, and ready for plants to grow. They wish instead of being suited adults, to be craftsmen and women, to make their own goods, to live as sustainably as possible. They wish to learn about the earth, the cultures so far from their American upbringings, the ways to fight the horrors of modern life by simply not participating.

The difference with this group, the real-life characters of Soberscorve Press’s Learning by Doing at the Farm: Craft, Science, and Counterculture in Modern California, as opposed to the many “familes,” hippie communes and free-floaters is simple: they’re getting class credit for it all.

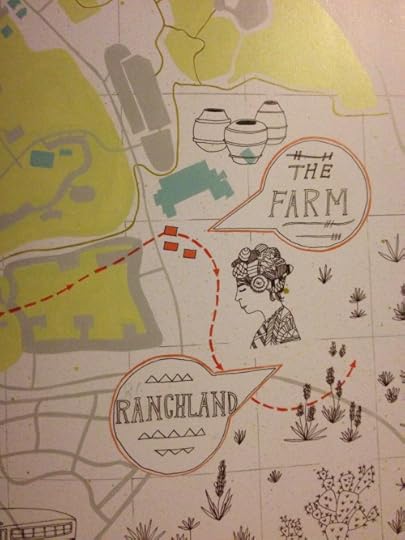

Starting in the early sixties, the University of California, Irvine, began to put together an experimental off-campus living space, a home on non-developed land owned but unused by the school. Their goal was to create a living, breathing farm space where students would learn from indigenous peoples who would visit/teach/live with the students; become familiar with the ways of life and the creation of goods before the modern-day consumerist culture took hold; and of course, to study the effects of alternate learning environments and techniques.

a map of the farm, as found in the book

In short, to so many dreamy 19-teen year olds of the 1960s, their school was working on creating a perfect counter-culture space for them to just be.

Learning by Doing is actually less of a book about that house, what went on in it and what the students learned than it is a collection of the documents, meeting minutes and photos archived from preparations for the house and planning going into the experiment, as well as photos from the day to day lives of the students lucky enough to get in during the short time the house functioned.

Well, I shouldn’t say there are no stories about day to day life. There’s amazing anecdotes about the students thrown in there, like this photo diary about some kid everyone called Frog who hardly wore shoes and wore his unbuttoned shirts so long they covered his shorts. In like 4 photos, I feel like I understand the story of this guy.

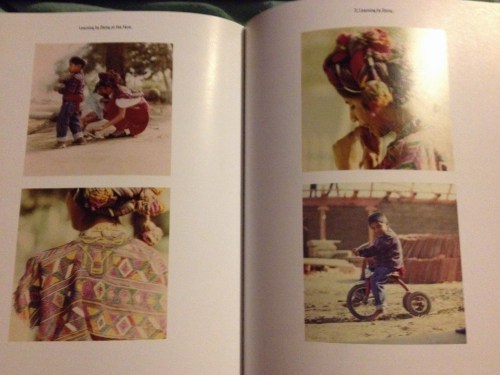

So much of the book explores the red tape you’d never even think about, though. Like, it sounds easy to just set up some simple structures on empty land. Still need permits, and when your with the school, funding forms, accounts, etc. It sounds so cool to hire craftspeople from Mexico, Samoa and Guatemala to teach the kids how to weave, make houses, throw pottery, but actually, the United States has miles of red tape keeping you from bringing in visitors for so-much time and how much exactly you’d have to pay them and how exactly you’d have to qualify their visit. This is kind of a bummer to free spirited hippie kids who’d much rather just do, in basically any sense besides doing paperwork.

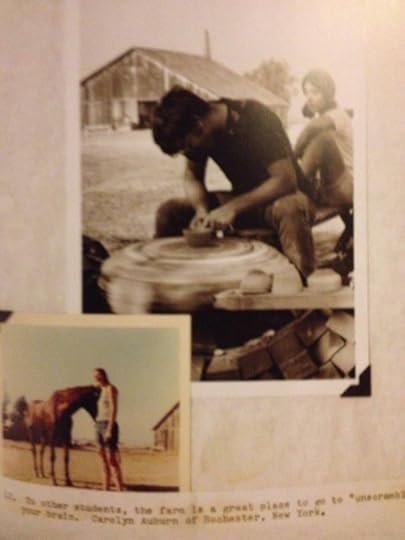

portraits of a weaver and her family living and working on the farm

It’s still such an interesting idea, though. Even though the class on the farm didn’t last long, as the evidence shows, it made a great impact. Is it just impossible to have alternative classrooms? Was this college just not properly invested to make the whole thing really work? Every hippie ounce of me hopes not.

scenes from life and learning on the farm

September 5, 2014

Now

The Luminol Reels by Laura Ellen Joyce

The Luminol Reels by Laura Ellen Joyce

Today’s fun definition, brought to you by Wikipedia: “Luminol (C8H7N3O2) is a versatile chemical that exhibits chemiluminescence, with a striking blue glow, when mixed with an appropriate oxidizing agent…Luminol is used by forensic investigators to detect trace amounts of blood left at crime scenes, as it reacts with iron found in hemoglobin.” You’re welcome.

What this book is is—and it’s so small, physically, you’ll be kicked several inches back to feel it—this incredibly dense, fragmentary list of atrocities or harms, basically, each of which is small (

But there’s something happening here that’s more than just a gross-out or brutalizing: Laura Ellen Joyce is trying to get the reader somewhere: we start at “Mothering,” in which the blood and ruptures of flesh are already (of course) present and we end on “Revelation,” which is as follows:

Oxidation of luminol is attended by a striking emission of blue-green light. An alkaline solution of the compound is allowed to reac with a muxture of hydrogen peroxide and potassium ferricyanide. The dianion (5) is oxidized to the triplet excited state (two unpaired electrons of like spin) (6) of the amino phthalate ion (Scheme 2). This slowly undergoes intersystem crossing to the singlet excited state (two unpaired electrons of opposite spin) (7), which decays to the ground state ion (8) with the emission of one quantum of light (a photon) per molecule.

Is it already obvious that the back of the book’s got an image of the Shroud of Turin? Or that the first-person-plural that feels weirdly exclusive at book’s start by the thing’s end feels radically, harrowingly inclusive? That the book reads like an assortment of the atrocities we visit on each other and that, because of the causelessness of the book—these things just happen, a priori, idiopathically, right from the book’s first entry—you’re left at book’s end suffering a raft of questions as applicable to your extra-book existence as they are to the text you’re just leaving?

This should all be obvious.

September 4, 2014

A Distant Father, Other Press Again.

Antonio Skarmeta’s A DISTANT FATHER

Antonio Skarmeta’s A DISTANT FATHER

Other Press again. This house just knows how to find stories people need to read, especially if it means they have to travel outside the U.S. to find them. I’m smitten.

Take A Distant Father. It’s tiny, easy to underestimate again. You almost have to call it a novella with it clocking in at about 100 palm-sized pages. Still, in such a short space, so much is said, so much pain and longing and emotion is felt.

The story revolves around Jacques, a Chilean schoolteacher in a small village. At 21, he’s hardly older than his students, hardly has any more life experience than the boys in his class. His days pass easily, automatically almost, like most people in their early twenties. Time is spent teaching literature, history and a couple other subjects Jacques does not like as much. As a second source of income, he works for a local paper translating stories and poetry into Spanish from the original French, the language of his father, a man who walked out on Jacques and his mother without warning.

Other than that, time is passed admiring the sisters of his student, two beautiful girls with a mysterious waywardness in their dress and attitude, the object of much speculation from the small town, and spending time with the town’s baker, a man that knew Jacques father maybe better than anyone else in the area.

It’s the simple question of the cost of a girl in the nearby city’s whorehouse asked by one of Jacques students that sets the story into motion. Immediately, Jacques replies it is not right for him to discuss such things with a student. In secret, he wonders himself. He’s never been to the whorehouse, maybe – although he never reveals it to us – he’s never even been with a woman before. And he wonders why not. And he plans his visit to the city of Angol, telling his mother and the rest of the curious in town that he’s going to the cinema, researching for a new translation he is working on.

Jacques finds his father in Angol, pushing a happy one-year-old boy in a stroller near the cinema house. Jacques and his mother had always imagined the man had gone back to France. Instead, he moved miles away, hiding himself in the dark projection rooms of the cinema, obtaining a new life and a new family.

Jacques does not express ill will towards the man. He thinks of his conversation with his father, the first one he has had in years, as similar to that of a friend. Still, the question as to why his father is there for that son, why he stayed with that mother and not with Jacques and his tears at the young man throughout the remainder of the novel.

I hate comparing books to other books with so much grandeur that when the new book doesn’t not become a classic or NY Times bestseller it looks like an inaccurate metaphor, but the only possible book for me to compare this to is Catcher in the Rye. It’s a boy – 21, not Holden Caulfield teen, yet a boy – growing up, dealing with his feelings of loneliness, going about his day in the best ways he knows how, just trying not to be too much of an asshole. More than that, though, A Distant Father zones in on the confusion of early adulthood, on the impossibility of knowing how to become a man when a role model was never there.

September 2, 2014

I’ve never ever understood what a “Post-Feminist” was anyway…

FEMINISM UNFINISHED: A SHORT, SURPRISING HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN WOMEN’S MOVEMENTS by Dorothy Sue Cobble, Linda Gordon and Astrid Henry

FEMINISM UNFINISHED: A SHORT, SURPRISING HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN WOMEN’S MOVEMENTS by Dorothy Sue Cobble, Linda Gordon and Astrid Henry

Of course I was going to read this book. Why wouldn’t I? It’s game plan is simply: to clearly and concisely trace the American feminist movement(s) throughout the last approximately 100 years – or from the moment women gained the right to vote until today’s women’s emphasis on “leaning-in.”

Of course I was going to read this. Although a feminist, I’m completely ashamed of just how little I know about feminist history (funny how this stuff never made it into my history classes. Actually, it’s not funny. My history classes taught me more about The Great Gatsby than they taught about early women’s labor movements). I’m ashamed that when non-white women speak about their discomfort with the way historically, the feminist movement did little to help women other than the upper-class whites, I had little idea what they were talking about. I’m ashamed that I could name hardly more than a few feminist leaders from before the 1960s. If you’re anything like me, Feminism Unfinished offers a great, three-hour alternative than taking a Women’s Studies 101 class at night school (which doesn’t sound bad. This book is also cheaper, though).

Broken into chapters by what society would group as the “waves” of the feminist movements in America, the book starts off with the story of the 1937 Woolworth’s strike throughout Detroit, a byproduct of those first-wavers fighting for women’s labor laws and work-place equality. It’s an interesting concept, since I’m so young I don’t even really think about it, but the book talks about how, often the first step in gaining women’s rights in the workplace was not to get the women into men’s roles – it was getting the “women’s roles” to be desegregated. Of course, this goes into the whole step-by-step achievement effect that we are still experiencing today – to get better rights for women, we should focus on those women in the lowest position catching up first, then advance from there, so on, so forth.

It’s entirely changed my perspective, given me a slap-in-the-face reminder that, more important (or at least, as equally) than getting a woman into the Oval Office in 2016, we should work to get women out of abusive situations, out of the worst of the worst. In feminism, it seems, there is little to no evidence of a “trickle-down” effect. More on this later.

Anyway, the first chapter continues on with the story of early women’s rights victories and leaders that helped achieve them. There’s exploration into the power of WWII propaganda such as “Rosie the Riveter,” as well as a look into how, ultimately, this was not a success for women, since after the war was over, women did not move up from their wartime roles, but often, straight into the home or their old jobs.

The second chapter (again, exploring the “second wave,”) focusing more on the 1960s and 1970s movements to achieve women’s liberation on all front. Think the progress of Roe vs. Wade (which has, since the ruling ever increasingly come under fire). Think the creation of a Miss America pageant contest that increased the sway of a woman’s intellect and heart on the judge’s decision. Think fights against gender stereotypes, against the idea that women in graduate school was still uncommon, that it was common to think of a woman’s salary as “pin money.” All the stuff my aunts fought for (therefore, find myself finding a little more footing in this chapter than the previous, which had just blown my mind open that I had no idea).

Finally, the last chapter explores the “third waves,” a term coined by Alice Walker’s daughter, Rebecca Walker, as she wrote in a 1992 essay. “I am not post-feminist,” she wrote, “I am the Third Wave.” These feminists desired both to distance themselves from the feminism of their mothers, feminists who saw a dichotomy between enjoying makeup and high-heels and views on gender equality. In the third wave, choices were purely an individual choice. Actually, much of the third wave seemed individual.

The book does a great job tracing the third wave al the way to today – answering, actually, another one of my questions (whether or not we have begun a fourth wave (in short: naw)). There’s a look at the rise of the internet on the community of feminism, the way the internet has helped feminist writers find a home for much writing that would have been passed by from traditional media outlets (thank you, The Internet!). There are looks into the riot grrrl movement and Kathleen Hanna’s brand of screaming feminist rock (which, in my personal opinion, there could have been like, 80 pages more of, but that’s coming from the number-one girl bummed to be born in 1991.) Of course, they didn’t have room to mention everyone my personal feminism has found influential (no Rookie??), but overall, it’s a great summary.

OH, and what I was saying earlier about the trickle-down effect being especially relevant today! I’ve never read Lean In. I don’t plan on it, either. It’s aimed at corporate, HIGH-level female CEOs. I am not high-level. I LOVED that this book pointed out the flaws in the lean-in pressure many women now face in the workplace – for one, leaning in to our jobs is not helping the feminist movement. One woman becoming the CEO does not help the ladies getting passed over in the lower offices because of their gender. Two, for women in those lower positions, there are rarely opportunities to lean in. This is by no means a focal point of the book, but it’s a good reminder: slaving at your job does not make you a feminist warrior (unless your job is like, a rape crisis center worker or being Ruth Bader Ginsburg, then by all means, GO FOR IT, FEMINIST WARRIOR!!)

Basically, for any Women’s Study majors, this book may be more useful as a gift to give to people to help understand you. This may not teach you much about the movement, as it is a concise, like 250 page summary. However, if anything I’ve mentioned above doesn’t sound intimately familiar to you, this book will probably help you learn about the basics of our feminist history and is definitely worth your time. It was definitely worth mine.

August 30, 2014

Antonya Nelson Antonya Nelson Antonya Nelson

I realise by doing the following I’m precisely part of the problem and not the solution, but: holy hell does Antonya Nelson deserve more praise and attention. The claim she doesn’t have enough of both is, in fairness, somewhat hard to 100% support: stories from this collection have appeared in the very very best mags (most recently Harper’s), so it’s not like she’s some gooberish nobody, okay, fine, sure, but still: is there a phrase or term for the club of gathering of writers whose work should be much more read and appreciated (and, maybe, would be more read/appreciated if we didn’t like in such quick-quick-do-the-next-thing times? Obvious other candidate from this summer’s releases: Dybek), and then, once that club’s named and identified, can we all go to work getting that club disbanded through the best possible way, i.e. reading those folks?

Here’s why Antonya Nelson’s so great, by the way: her sentences are lithe and charming and conversational (opening at random, here’s page 6: “As was always the case when he and Bonita spoke to each other—neither remotely fluent in the other’s language—the information exchange was crude yet functional.” [there's also this, from later in the same story (which story's called "Literally" and opens the book): "This has been a terrible day," Danny said. "Even though nothing exactly bad happened."]), and so the joy’s linguistic, certainly, but the thing I get from Nelson in spades that almost everyone else doses out in crumbs is the overwhelming humanity of her stories. Maybe that sounds lame-o and blasé. I don’t know. I don’t think it’s a trait I cared as much about five years ago, but now, dead-center in my thirties, as someone both trying to make writerly stuff that’s got some humanity and as a reader who’s hankering for humanity in art increases on the daily, Nelson is just it, laying banality raw and gorgeous in her stories in ways I at least am astonished by the first three or four times I read them (truly: in quoting from “Literally” above, I got dragged back in, amazed by the story anew).

There’s a moment in “IFF,” maybe my favorite of the collection, in which the narrator’s mother-in-law (who lives with her [lots of crossed/blended families in here, though even just writing that I'm surprised to admit it, surprised that it even registers—it's not, like, a thing, but it's there]) says “‘It’s the only saving grace of not being a mother,’ she said to me once. ‘I have permission to kill myself. You don’t.'” Amazingly, the story is sort of about (or at least interested in) this mother-in-law’s eventual suicide (which the narrator accepts and understands and just writing this makes it sound weird—in Nelson’s hands the whole idea’s art) but not in some central way: the story’s overtly about a missing daughter in a neighborhood in the desert southwest, and, larger, about responsibilities we have to our families (both of blood and choice). “IFF”‘s a stunning story, of course, but that’s not even very fair because they’re all fucking stunning, they really are. That feeling you get reading, I don’t know, Munro (and Dybek, certainly)? Where basically every story just clicks along and both gives you something and knocks you sideways? Big ditto. Hard to imagine a list of writers whose work puts them deservedly on such a list getting to be longer than a dozen. Can’t be many. Nelson’s one of them. Do yourself the obvious favor here: read her.

August 28, 2014

Tour the World with Joanna Scott!

Joanna Scott’s DE POTTER’S GRAND TOUR

Apparently this week on Corduroy: Books that are revealed in pieces!! I mean, non-linear pieces. Technically every book is revealed page by page, but don’t be a jerk. After “The Lotus and the Storm,” I didn’t even make a point of reading another pseudo-mystery, read-on-to-fill-in-the-blanks, but then came De Potter’s Grand Tour.

The novel starts off around 1902, with the happy life and marriage of Armand de Potter (or, to put it fully, Pierre Louis Armand de Potter) and his young wife, Aimée (fashioned from her maiden name, Amy). The two appear to be the finest types of Americans – educated, proper, with the penchant for traveling in luxury. Of course, Armand makes the large sum of the family’s income from these travels, on which he escorts wealthy Americans and Brits around the world, taking in the sights and “doing the pryamids” and the like. His other source of income is destined to come from his collection, a trove of statues, treasures, figurines and native pieces he has expertly gathered from his adventures.

At least, this is the first glimpse we get of the couple. But life is hardly about the first impression alone.

While Aimée stays back in New York with their young son Victor, news arrives that her husband has been lost at see. Word gets around that he was last seen too close to the railing of a ship; a girl working aboard seems to have seen him fallen off over the edge. No one can say for sure if the man jumped or if the event was purely an accident. Either way, Armand has left Aimée alone with their son to carry on his adventures, requesting simply (although oddly) that should his body be lost and never given a proper burial, his wife should erect a monument in his honor.

There’s a problem, though, when Aimée goes to withdraw funds from their account. It seems their money is gone, or there was never so much in the first place.

I forget exactly where it’s revealed, but of course, Armand is not completely the man he pretends to be. In fact, the man is an immigrant, an ambitious man who arrives in New York in the 1870s, finding his footing and paying the bills through a number of schemes. Over the years, the man de Potter reinvents himself as an aristocrat, a gentleman, a scholar, a collector of rare artifacts, and maybe even a member of the Belgian aristocracy. It’s this remarkable, supposedly world-renowned man that Amy falls in love with while he is working as a French professor in her girl’s school. It’s this man whom the wealthy trust to take them on tours of the world he has traveled in such detail.

Not only is the plot a completely fun, perfect end-of-summer travel and adventure tale, it’s got a rare finesse in the ease of its historical context. If you’ve read a bad historical novel, you’ll know what I mean by this – the author, so desperate to get you in the mindset “HEY THIS IS 19WHATEVER!!” will throw in miscellaneous details that no one cares about to make it seem like they are painting the imaginary world of that 19whatever, only to make you, the reader, so mortifyingly self-conscious to the fact that you are now outside not just the novel, but the author is also outside the novel, and neither of you can get into that time period, so the author desperately is throwing you ropes of events that were maybe very important around that time…. Is this just me? I don’t know, I struggle greatly with historical novels written in 2014. It’s hard for the author to actually convince me we are in that time. But Scott does it, effortlessly. The book flows so easily, you just know you’re in 1900s and she doesn’t have to slam you over the head with it. The work speaks for itself.

Anyway, to summarize after that monster of a ramble I just spewed: De Potter’s Grand Tour is a delightfully witty, clever, perhaps philosophical tale that I really really think you will enjoy.

August 26, 2014

Lotus, Storm, Saigon Falls

Lan Cao’s THE LOTUS AND THE STORM

Lan Cao’s THE LOTUS AND THE STORM

Set alternatively between a war-torn Vietnam and Virginia in the mid 2000’s, The Lotus and the Storm tells the delicate story of a family torn apart and bound together forever by the Vietnam War. Balancing between the voices of father and daughter, the family’s secrets, pains and truths too raw to speak of all come to light as they reflect on their homeland and the divided feelings they have about the country.

Growing up, young Mai is aware of the war if only distantly. It’s something her father Minh is heavily involved in as a commander of South Vietnamese troops, and the reason her American friend, a boy named James who introduces her to the music of Mick Jagger, has come to Cholon the sister city of Saigon. Only 9, Mai is hardly concerned with the realities of the war, simply tagging along with her older sister and best friend Khanh as she tries to listen in on her father’s communications.

Minh begins the story hopefully that the South can combat the trouble coming from North Vietnam. He’s even slow to see the signs of approaching disaster as the Americans begin to grow wary of their involvement in the land and more and more of his own neighbors join the Vietcong, a group Minh sees as traitors to the country.

War aside, Mai, her father, her mother and sister are a typically family at this point. There are aunts and uncles adding to the family drama; fights between Minh and an uncle who does not see help from the Americans in such a positive light. Their bonds keep them from each other’s throats, though. Until, Khanh is killed in a fluke by an errant bullet.

So soon after, the family and way of life Mai knows is irreversibly changed.

It’s as if a part of her own soul is buried with her sister. As her family says, Khanh was her first love, taken from her too soon. Mai goes quite, eventually ceasing to speak at all. People fear she has gone dumb; she’s simply given up words, finding nothing that needs to be said any longer.

As for Minh, there’s a haunting question of where the bullet came from. According to his wife, it must have been meant for him. His oldest daughter, instead, was the one buried. It’s a wrong she can never come to terms with. They separate, war and the hope of a peaceful Vietnam becoming Minh’s only obsession; his wife falls in love with an American military advisor, Cliff.

The focus shifts on America, even before all these details are revealed. There, in the mid-2000s, we see a sick and feeble Minh coming to terms with his own inability to care for himself much longer. We see Mai battles the storms inside her, alternating her time between the voices fighting inside her – Bao, the angry, quick to temper spirit that holds onto the hurt of the past and Cecile, a soft voice of a girl, playful, coaxed into speaking by birds. We see Mai fight to keep her family intact, help her aunt get the money she desperately needs, try to understand her uncle and accept the conditions upon which he left Vietnam.

Even though there have been chances, neither Minh or Mai have been back to Vietnam since the two of them fled by U.S. helicopter as Saigon fell.

The story slowly reveals itself piece by piece, never divulging too much too quickly. Why did Mai’s mother stay behind? What became of her? How did Mai, the mute child who refused to talk, grow into the role of a powerful, smart woman?

In a way, the structure is remindful of Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things- there’s evidence of a great tragedy that has happened between the narrative, evidence the characters are seeking redemption and explanation, yet, hardly any evidence the end of the novel will bring them healing.

Plot and suspense drives the story more than anything, but there’s not enough praise to be given for Lan Cao’s prose. Simple details bring scenes to life, a piece in the village of Cholon comes to life in my imagination as simply as one from Virginia. Descriptions of the hearty pho, delicately wrapped meats in thin rice paper made me hungry enough to run to the Vietnamese corner of Chicago.

Ultimately though, no matter how beautiful you find the writing, it’s little match for the story. It’s heart breaking, tense, threatening to rip apart at every seem. But in the end, it’s a story of every family’s secrets, their pain and the things they do in an attempt to pull themselves together.

August 21, 2014

Michel Laub’s THE DIARY OF THE FALL :: Best of 2014, Probably

THE DIARY OF THE FALL by Michel Laub

THE DIARY OF THE FALL by Michel Laub

I hate handing out a title like “Best of 2014” so early in the year. I hate handing it out, in general, because now it seems like any of the other books I’ve written about from January to this point are explicitly not the best, but there is no getting around it: Diary of the Fall struck me like no other book has this year. In a just world, it will be studied in schools alongside Elie Wiesel’s Night and Camus. It will be brought up in philosophical debates, when questioning the meaning of human suffering and humanity’s existence. This is not hyperbole.

It’s easy to underestimate. The book is literally the same length as my hand, from wrist to fingertips, and about as wide as my fingers naturally sit. It is easy to mistake for a tabletop book. Please do not make this mistake. The way the story is divided with chapters only paragraphs in length, numbered in the middle of pages, may make you think this is flash, pieces unrelated to each other. Do not make this mistake, either – every piece of the entire story connects together, forming a whole.

The story starts with the story of João’s fall. A Catholic boy in a class filled with 13 to 14 year old Jewish boys, João is teased, told to eat sand, criticized and mocked as the other. His father works as hard as he can as a bus conductor, overtime selling cotton candy in the park to pay for his son’s tuitions, adamant that his son get the best education possible. The young boys do not connect the blue-collar father to the hatred of the son; they are simply, childishly filled with contempt for the boy.

It’s a popular tradition of the boys that, on a young man’s birthday, friends gather around, hoist the boy in the air and toss one two three, and catch him safely. But on João’s birthday, they let him drop.

The fall sets off a chain of events that forever change not just the life of João, but of one of the Jewish boys who was there, who let him fall, who years later, still struggles to make peace with the injustices he committed as a child.

Soon enough, the novel is no longer about this isolated case of prejudice, this case of spite and hate and pain. It evolves into a tale of the most horrifying pains in the world, the unhealing wounds, the cuts that refuse to scab over so easily.

The narrator of the story, an unnamed journalist now in his 40s, decided to switch schools at the end of the year, to join João at his new school, even though it means he will now be the only one who is Jewish. A catalyst is started, with the narrator learning more, becoming more aware of his heritage and what it means to be Jewish in modern times.

Digging into his past, the narrator learns about the obsessive writings of his grandfather, a man who unlike so many, survived the horrors of Auschwitz, who later in life, poured hours alone in his room writing in journals false memories about the way life should be rather than the truth. His family, all of whom died in concentration camps, the horrors of war, are never mentioned. Later, his own father succumbs to Alzheimer’s, his mind failing slowly. His father uses the time he has to record the copious details of his life, the truth he is desperate to pass onto his son, one section sent at a time.

Sorting through his forefather’s works, the narrator comes to terms with his own weaknesses, his own desires to hide the pain, his own need to record the truth, hurt as it may.

I couldn’t believe how knocked away and emotional this all was. It’s like 200 pages, and I feel like a meet an entire family, learned their secrets, cried for each as he suffered from war, from Alzheimer’s, from, as we learn later about the narrator, battles with alcoholism.

I can’t help you if you think World War II stories are overused at this point. It is a subject I will never be able to ‘get over,’ despite never having lost more than maybe a great-uncle to that war. Yet, even the narrator recognizes the exhaustion most people have to these narratives, to the accounts of atrocities suffered at camps, to the horrors humans were put through, worse than any horror film could imagine:

“Would it make any difference if the things I’m describing are still true more than half a century after Auschwitz, when no one can bear to hear about it anymore, when even to me it seems old-fashioned to write about it, or are those things only of importance to me because of the implications they had for the lives of all those around me?”

I understand the holocaust does not represent my pain. I lost no one to the camps. It’s larger, though. It’s a pain that shows just how god-awful humans can be to each other, how long the body can suffer before collapsing into dust, how cruel the world can be and how soon we can stop caring to you talk of your pain.

You might never connect the story of one little boy being dropped by his classmates to the horrors of Auschwitz. These are incomparable in terms of human suffering. Yet, in Michel Laub’s prose, all pain connects, feeds, and tries to understand each other.

This is one of the best books you can read this year, for many years, maybe.

August 19, 2014

Hair, Hair, Hair.

Michelle Lovric’s THE TRUE AND SPLENDID HISTORY OF THE HARRISTOWN SISTERS

Michelle Lovric’s THE TRUE AND SPLENDID HISTORY OF THE HARRISTOWN SISTERS

Darcy, Bernice, Edna, Manticory, Oona, Pertilly and Idna Swiney weren’t born into wealth, fame or good fortune. There was little of that to be found in Harristown, the small Irish hometown of the sisters. It’s the enterprising spirit of the eldest sister Darcy paired with the magical, flowing waist-length locks of hair, each a different shade from raven black to fairest blonde that pulls the girls out of their small-town, unknown existence. Combining magical realism, just a hint of fairy tale lore and the real real emotions of a group of sisters coming of age, Michelle Lovric’s The True and Splendid History of the Harristown Sisters is a delightful, if sometimes dark, tale of love, family and loyalties.

The story, always transcribed, recorded and told through the voice of middle sister, redheaded Manticory, the sister with the gift of words, starts with the girls as children and young teens, mostly concerned with petty rivalries between twins Bernice and Edna and teasing the runt of the town, Eileen O’Reilly. With only a mother around, their father either dead (Manticory suspects, at the hands of Darcy), a drifter, or as some around the town speculate, a whole collection of different men, it’s no secret that these girls fortunes may well lead to them falling victim to the potato famine sweeping the country. There’ve been too many hungry nights, too many cases of hair nites for these girls to expect much else.

That is, until Darcy comes up with a plan to reverse their meager circumstances. Gathering the sisters, Darcy stronghandedly instructs the girls in the ways of Irish dance, creating routines that focus less on the skills of the footwork than the great reveal when all seven sisters let down their long locks to the oohs and ahhs of the audience. It catches on like fire. Soon, the sisters leave Harristown behind, taking their act to larger stages in Dublin, Venice and beyond.

Soon, the girls align their fortunes with an entrepreneur, skeezy man Mr. Rainfleury, who concocts a worthless hair tonic, marketing it under the guise it will make anyone’s hair grow as long as the Swiney ‘Godivas.’ Then there is a line of dolls with the magical, lengthy hair, more serums, more shows, more more more profits and fame.

The girls grow older – Edna marries Mr. Rainfleury, Pertilly grows plump and plain, Darcy grows greedy and controlling of the sister’s profits, Manticory grows tired of following Darcy’s harsh rules and wasting her intelligence, Idna grows homesick for the comfort of her mother and Harristown and develops, much like a cat, a nervous habit of eating her own hair and spitting it up in clumps. As the sisters enter maturity, the benefits of the Swiney Godivas, the rivalries between the girls come into question, yet Darcy, Mr. Rainfleury and the other men taking stock into the girls refuse to let any of the seven give up the act.

It’s a funny fairy tale, with hints of Rushdie’s magic peeking through a mainly realistic prose and nods to the legacy and legend of Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. Although this novel doesn’t quite reach the level of the writing of either of the geniuses mentioned before (which, to be fair, is hard hard hard for any author or book to ever reach), there’s much to be hopefully for in anything forthcoming from Lovric, and, if nothing else, exemplifies the perfect way to mix fairy tales and lore with the harsh realities of a nation’s, family’s and culture’s truths.

August 14, 2014

Whiskey Tango Foxtrot=Damn Near Perfect

Reliable sources—Laura Miller, Garner the Great—have already heaped tremendous and due praise on David Shafer’s Whiskey Tango Foxtrot, so hopefully you’ve noted it and paid attention and done yourself the service of buying/reading the thing. If you haven’t, I can just say this: I read Shotgun Lovesongs in a sort of blissed fugue, unable to believe I’d read anything better this year, and certainly not a better debut novel, and yet here’s WTF, as dynamite a debut as one could hope for and as engaging and enjoyable a read as one could possibly demand, from anyone, anywhere, any time period.

Reliable sources—Laura Miller, Garner the Great—have already heaped tremendous and due praise on David Shafer’s Whiskey Tango Foxtrot, so hopefully you’ve noted it and paid attention and done yourself the service of buying/reading the thing. If you haven’t, I can just say this: I read Shotgun Lovesongs in a sort of blissed fugue, unable to believe I’d read anything better this year, and certainly not a better debut novel, and yet here’s WTF, as dynamite a debut as one could hope for and as engaging and enjoyable a read as one could possibly demand, from anyone, anywhere, any time period.

Some context: I’ve spent a good chunk of this year trying to understand what it is I want from books(/TV shows/movies), not because I’m unclear, but because, at 35, I’m now trying to have maybe a more adult understanding of the work and ingredients and gears at play in the cultural/artistic stuff I draw nourishment from. It may also be because I’m a dad, meaning I’m now keenly aware of the fact that I’m entering a phase during which there’s a slim but real chance I’ll be asked to explain or retaionalize my take on stuff, why something is thus and so and why I give any damns regarding such (I know: chances are maybe more than slim that questions like that’ll arise, but whatever). The obvious stuff—great characters, good conflict, insights offered into general Humanity stuff—is fair, sure, but I’ve been trying to get at more what it is I like. What are the ingredients in art that knock me to my knees? Why does Wallace floor me but not Vollmann? Jorie Graham but, less, Saskia Hamilton? The Replacements but not Husker Du? How come the Walkmen’s stuff is so amazing but Leithauser’s solo’s a groaner? None of this is rhetorical: it may just be the circumstances of my current existence, but it does seem like, at some point, one’s sort of wise to spend some time articulating as clearly as one can just what it is about the things that floor them floors them.

Which is a roundabout way of saying: Whiskey Tango Foxtrot lights my head up like fucking pinballs, enjoyment-wise. The Good Ingredients are out in full force: The three central characters are clear as hell, real and believable as a stubbed toe. There’s Leila Majnoun, a burning-out nonprofit worker on whom the book opens, in Myanmar, as she’s trying to get a flat of medical supplies through the red tape of a militarized dictatorship; Leo Crane, a sort of flailing and failing trust-funder who happens to be an addict of various indulgences and a paranoid-ish conspiracist; and Mark Deveraux, an earnest Harvard-on-scholarship kid (at which school he met and became great friends with Leo, though they’ve since fallen out) who, through strange kismet, has ended up in a life-coach/advisory role for the CEO of a company that’s basically Amazon+Google+Facebook, and ps Mark’s taken quite fondly to indulgences Leo’s trying to flee. The conflict—basically, the CEO’s company is trying to secure *all* experiences, digitize everything, then charge for access—is astonishing for the nooks+crannies it offers, and for how it—mercifully, wonderfully—doesn’t ever play dumb (an open request to people making any narrative art: trust the person reading/viewing to make the leaps with you. Regarding the stuff above, from paragraph 2, about trying to figure out what makes something [to me] enjoyable or good, nothing’s more astonishing than recognizing that there’s an almost inversely parabolic relationship between the work asked of the reader and the enjoyment offered—if no work’s demanded, the enjoyment’s so limited as to be overlookable). WTF also—again mercifully—pulls off one of the hardest tricks in the sci-fi-ish bag, which is it proposes something that’s a few steps removed from/ahead of current reality but feels so oh, right, sure that you’ll likely have a hard time reading any tech news in the weeks after finishing the book without going wait a second, wait just a second here…

But the Big Deal about Whiskey Tango Foxtrot is, to me, the insights. That’s not the right word. That feeling of reading, say, Wallace (or some Kelly Link, or some other folks I can’t think of off the top of my mid-week head [Jim Shepard for sure]), where this sort of to-the-side (~plot-insignificant) detail hits so true you’re spellbound? In Jest, that long thing early about the guy trying to quit smoking pot, and the page after page of how he throws everything away and starts all over again, and how if you’ve ever had an imbalanced relationship to any intoxicant you’re just going fuuuuuuuck? That’s what I mean. Here’s how neatly Shafer deploys it: Leo, at some point reminiscing about Mark, makes some mention (I didn’t mark the page, stupidly) about how overly puppy his old friend always was, and how he (Leo) wanted him to realize that the best girls like to work a little, too, they don’t just want to be fawned over? I’m mangling the fuck out of the whole notion and scene (which is, literally, a sentence), but there’s this just tremendously insightful grace Shafer offers, again and again, that’ll knock you sideways. I’ll have an interview with him up soon-ish, elsewhere, and in it I mentioned the first place this sort of thing transpires in the book (this sort of thing: perfect writing capturing an exact sensation in such an intuitive way you’ll likely start thinking in the author’s words), which is on page seven, and which goes: “The menace was present in everything here; it was like walking by a man holding a stick, the man silent, the stick raised above his head.” (describing Myanmar) There’s writing like that in heaps throughout WTF, a bounty of details nailed and sensations given damn near perfect articulation.

I don’t know. I don’t know how to hype this enough. Garner’s got it right: it’s easily the book of the summer, and it’s smart and funny and hilarious and I read it in two days and would’ve chomped it in one were I not a father and husband. If you’ve read reviews on here before, you know that, often, the books I like most are the ones that almost evade or trump any good review or criticism: they’re wholly themselves, same as any love’s wholly itself, and nitpicking seems as silly as a happy person coming up with something he’d like to go back and change about his life—change nothing. Whiskey Tango Foxtrot is a glorious read and deserves heaps of attention and praise, plenty of which has already come its way but plenty more of which is due. Do your part, pass it along: this is less a book that needs readers than a book that readers need.