Weston Cutter's Blog, page 4

February 25, 2015

Entering Ducornet’s Deep Zoo

Rikki Ducornet’s THE DEEP ZOO: ESSAYS

������ I���d love to see the world through Rikki Ducornet���s eyes, if only for a day. If only for an hour. If it���s anything like her newest collection of essays, The Deep Zoo, it���s an entirely magical, kaleidoscopic view.

������ I���d love to see the world through Rikki Ducornet���s eyes, if only for a day. If only for an hour. If it���s anything like her newest collection of essays, The Deep Zoo, it���s an entirely magical, kaleidoscopic view.

Even though the essays where written over journals, magazines and years, there���s a constant thread running through them all, the idea of that ���deep zoo,��� something Ducornet���s sees as the very essential pieces of an artist���s creative output; the themes they get stuck on and contemplate for life. The colors and emotions that stay present when you take away all the outer shapes and images of an artist���s work. The yearning present in a story���s conflict when you erase the circumstances. The mood and tones underlying every song on an artist���s LP.

In Ducornet���s eyes, everyone���s Deep Zoo is different. Based on this book, one can assume her own zoo holds the following: Animals, struggling through the world, dying naturally and beautifully. Ancient gods sharing their gifts, chief among them, Eros, god of love. Fairy tales, passed down through generations not because of their appealing lore, but their unapologetic truths.

Ducornet���s essays move all over the place, always trying to find the Deep Zoos of her subjects. And these folks themselves are fascinating. There are artists Margie McDonald, an experimental sculpture who creates a sea filled with creatures out of wires, aluminum, whatever she gets her hands on, and Linda Okazaki, whose paintings come alive with symbolism of animals as lovers (it should be little surprise that Ducornet herself is a painter, her understanding of art leaping across genres and materials).

There are discussions of literature. Ducornet calls on everyone from Kathryn Davis to Kant to measure the images she sees written on the pages of people such as Omensetter���s Luck, a novel published in the 1960s and lauded as a classic, or Sade���s 120 Days of Sodom. Obviously, the literature she finds fit to discuss in this collection finds no bounds.

There are looks into film ��� even the screen not too small or immature a platform for Ducornet���s concerning eye. Lost highway is scrutinized in comparison to Lynch���s other works and in comparison to myths of the Evil Eye.

But best of all are Ducornet���s look into mythology, the legends of Eros and of fairytales, and tied to this, her looks into her own work. Here we see her at her most vulnerable, trying to piece out the themes of her own work that she believes may yet endure, the aspects of her words and her earth she wishes the audience not soon forget.

A piece from one of the essays, ���The Practice of Obscurity,��� shows exactly the way Ducornet���s mind melts things together: ���For if Eve broke the rules, her other intention was to keep a garden. And if the apple is one she bakes into a pie, it is also the one that poisons Snow White and renders her comatose.���

Prepare to be smitten with allusion upon allusion upon illusion.

February 16, 2015

MAKING NICE by Matt Sumell: Best of 2015, Easy

�� �� �� �� �� �� I know I had a review copy of Matt Sumell’s Making Nice kicking around in the basement for awhile with me, and I’d try it occasionally, and for whatever reason it didn’t quite hang, and then finally one afternoon I dipped in+the thing transformatively took off in ways I’m embarrassed I somehow missed all those weeks and weeks I’d been trying but not catching it. The give on this is fairly direct: it’s a ‘linked’ or whatever collection of stories, all of which center around Alby, an early-30s guy whose voice is fervently alive, yes, but who’s also lost his mother to cancer and who has a father with whom he has a relationship that’s somehow not very warm and somewhat combative but also so deeply full of love it makes you fucking weep, plus there’s Alby’s sister Jackie, the sort of subject of the first story, “Punching Jackie,” which story’s about the rightness of Alby’s punch of his own sister, and like most of the stuff in Making Nice, you can’t read “Punching Jackie” without thinking 1) Alby’s sort of a dick, 2) he’s also almost entirely bullshitfree, meaning his calls and choices are almost never *wrong*, just sort of brutal and exposing, and 3) you can’t help but feel for Alby: he’s a mess but he’s so authentic in aiming for his own basically legit notion or idea of good that you can see, again and again, how he’s gonna get shafted by things, but then, each time he does, you still wince and feel for him.

�� �� �� �� �� �� I know I had a review copy of Matt Sumell’s Making Nice kicking around in the basement for awhile with me, and I’d try it occasionally, and for whatever reason it didn’t quite hang, and then finally one afternoon I dipped in+the thing transformatively took off in ways I’m embarrassed I somehow missed all those weeks and weeks I’d been trying but not catching it. The give on this is fairly direct: it’s a ‘linked’ or whatever collection of stories, all of which center around Alby, an early-30s guy whose voice is fervently alive, yes, but who’s also lost his mother to cancer and who has a father with whom he has a relationship that’s somehow not very warm and somewhat combative but also so deeply full of love it makes you fucking weep, plus there’s Alby’s sister Jackie, the sort of subject of the first story, “Punching Jackie,” which story’s about the rightness of Alby’s punch of his own sister, and like most of the stuff in Making Nice, you can’t read “Punching Jackie” without thinking 1) Alby’s sort of a dick, 2) he’s also almost entirely bullshitfree, meaning his calls and choices are almost never *wrong*, just sort of brutal and exposing, and 3) you can’t help but feel for Alby: he’s a mess but he’s so authentic in aiming for his own basically legit notion or idea of good that you can see, again and again, how he’s gonna get shafted by things, but then, each time he does, you still wince and feel for him.

I don’t know how to pitch this book more highly, honestly. I fell into it through the story “I’m Your Man,” but it could’ve been any of them, plus there’s also this: you remember that feeling that comes from a book of fiction that’s actually got an emotional risk in play? Like: it’s not just language, and it’s not just ideas���you can feel a level of blood+guts? That’s Making Nice: I teared up at the end, for how desperately Sumell’s trying to get Alby where he needs to go, and for how rawly clear Sumell���in prose that’s hilarious and both tender and tough perfectly equally���paints everything. It’s a ferocious, glorious book, and the only downside is that the thing ends, and, from my vantage point, there’s not a single other writer doing stuff this alive and wild, meaning: we’re just gonna have to read the hell out of this till Mr. Sumell writes another thing.

Sumell was kind enough to answer some questions over email, the results of which are as follows.

In the broadest ways: what are your and/or the book’s ‘influences’? (At one point in the book you mention Alby being a lifelong baseball fan, and as much as this question’s obviously *about* books or whatever, if there are other things that influenced it���baseball on the radio, I suppose, or the feeling of being on boats, or whatever, I’d be excited to hear them.)

Oh man, there���s just too much to cover here, be it the bands I grew up listening to���like The Afghan Whigs, Faith No More, The Jesus Lizard, Ween���or my 30 years as a Stern fan. I take my comedy very seriously, go to shows at the Largo and Meltdown pretty regularly. Love Todd Barry, Natasha Leggero, Bill Burr, David Cross. There���s movies, or more specifically movies with a healthy amount of pointless aggression, like MacGruber, for example, like Hamlet 2. But maybe what I should speak to is the complexity of influence itself, how–when answering this question–most people tend to list off a string of favorites, like I just did, people and things they admire and hope they were influenced by. I���m not actually convinced it works like that, as I���d bet I���ve been influenced by a lot of things that are not only not my favorites, but in fact the opposite of my favorites. Check William Gass on this who, when asked why he wrote, responded: ���Because I hate. A lot. Hard.���

It���s almost too obvious to put in print, but what I hate most of all is losing people. Parents. Girlfriends. Friends. Pets. I���m just the worst at it, and as a writer who tries–as Geoffrey Wolff put it–���to use the good luck of bad luck, to use what hurts,��� well, that���s been a major theme for me. Loss. It���s something I circle around, as both a person in the world and as a writer. It���s certainly one of the things I have in common with Alby. We suck at grieving. And speaking of grief, I am, indeed, a Met fan. There���s a certain pain in that, too, although that���s more comedy than anything else at this point.

And you very smartly zeroed in on boats. I grew up on them, and there���s a certain lure there for me, a mysticism around which there���s a very specific culture that I can speak from. And believe me, this list could go on for pages about any one of these things���

Sorry if this is too stupid, but: how autobiographical is the book? Lots is made clear in the acknowledgements���your mom passing, a brother named AJ���but I’m just curious. Equally I’m curious about how anxious you are for how folks’ll read the book���as a young man’s working-through of sorrow, or as an actual, fictive thing. I don’t at all mean to be a dick, but in the rawest sense: how much are you Alby? Are you nervous or anxious or anything about how much the book feels like it’s exposing? (in fairness: maybe it’s exposing nada, and you’ve just made a phenomenally believable work of fiction, in which case: holy hell that’s some good tricking). I hope none of this comes across as anything other than the respectful/amazed qs of a guy who sort of can’t imagine opening up the way it sure seems as if you have.

Sorry if this is too stupid, but: how autobiographical is the book? Lots is made clear in the acknowledgements���your mom passing, a brother named AJ���but I’m just curious. Equally I’m curious about how anxious you are for how folks’ll read the book���as a young man’s working-through of sorrow, or as an actual, fictive thing. I don’t at all mean to be a dick, but in the rawest sense: how much are you Alby? Are you nervous or anxious or anything about how much the book feels like it’s exposing? (in fairness: maybe it’s exposing nada, and you’ve just made a phenomenally believable work of fiction, in which case: holy hell that’s some good tricking). I hope none of this comes across as anything other than the respectful/amazed qs of a guy who sort of can’t imagine opening up the way it sure seems as if you have.

Totally fine, man. It���s the question folks seem most interested in, and I get why they���re interested���I���m grateful for any interest. I���m just not sure how to answer it���53% in this story? 22% in that one? How one would even begin to calculate something like that I have no idea and besides, the book is a creation regardless of what I���ve taken from ���real life.��� I���ve selected things to include, meaning I���ve also selected things to not include���it���s not the whole truth but a distortion of it, a misrepresentation to suit the needs of the story. A misrepresentation of truth is a fiction. Plus, a lot of this thing is complete invention��� just made shit up, also to suit the needs of the story.

That said, I won���t deny that parts of it are deeply personal���that it was ���emotionally expensive��� for me to write. And while I certainly share some things with Alby���like being a shitty griever, for example, or being a Met fan���I���ve also allowed him to make worse choices than I would or could, simply on the idea that bad choices make for good stories.

If that���s not a satisfying answer, consider Hemingway���s take on it: ���The good parts of a book may be only something a writer is lucky enough to overhear or it may be the wreck of his whole damn life and one is as good as the other.��� So sure, some of this book is from���as in inspired by���the wrecks of my life, and some of it inspired by things I���ve overheard or invented. I���m just not all that interested in separating out for people which is which. I prefer to be judged on the work.

As someone who fled Minnesota for Virginia (tech) for grad school: why’d or how’d you end in California from NY? I don’t even know if that’s fair to ask. Maybe not.

Long story, of course, but the abbreviated version is that I graduated with degrees in English and Environmental Science from UNC Wilmington, which qualified me for exactly nothing except a thirty-nine-and-a-half hour work week in the garden department of a Home Depot in Patchogue, Long Island. Like most jobs I���ve had, it was fucking horrible. I mean, they had mandatory pep rally���s every Sunday morning where people chanted about having orange blood. I���m not even kidding, they did that. I lasted three months, if that, before I totally lost it, hung my apron on a rake and walked out.

Next thing I knew I was at a Navy Recruiters in Sayville, got pretty far into the process of joining up���took the ASVAB, got the physical���but when I wasn���t committing fast enough they started applying the pressure. At some point someone got in my face and said I was an embarrassment to my recruiter, then he got on the phone and started yelling at me. I told him to fuck off and walked off the base. That was that.

Next was teaching English in Japan but that didn���t pan out, ended up on the road with a mobile marketing job���me and my best friend since kindergarten���setting up racing simulators in bars twice a week, all over the country. Three years later we washed up in San Diego. Been in Cali ever since.

Does this book and your writing overall have any, that you can feel, like, kinship with other writing being done at present? The book reads to me as totally 100% its own; if someone were to come to me and say she loved the book and wanted something else similar, I wouldn’t know where to point. This feels so totally of-itself it’s hard for me to even imagine anything like an artistic/literary lineage its taking part in (maybe Hannah). Do you feel it grounded in something? This might be too close to the influences question, and, of course, my apologies if so, but it’s exciting, too, that this thing’s got so little in common with what I at least see as other contemporary lit.

That���s a tough one. The comparisons have certainly been made���names like Hannah and Diaz, Denis Johnson���s Jesus��� Son���but I���m not comfortable making those comparisons, at all. I mean, while I���m tremendously flattered to even be mentioned along with writers of that caliber, have I really earned those comparisons? I���m not sure I have. Those guys are heroes of mine.

Besides, that���s for other people to decide.

Among the Great Glories of the book is of course Alby’s voice���assured and searching and elsewhering at all times: the number of times a paragraph’s start feels like it’s got almost nada to do with the para previous is astonishing (that’s me trying to say: congrats for the courage or whatever it was that allowed you to trust making such turns). I remember way far back JSFoer talking in some interview about the voice in Everything is Illuminated, how it took time to nail it down but how sure he was of it eventually. Did finding Alby’s voice take time? Was there any process to it, or did it just hit?

I think I had the voice fairly early on. And I had decent aim, too. But what I didn���t have are targets worth taking aim at���if that makes sense���and it took me a while to figure out that good writing is not standup. It���s much more than that. A lot of my early work just couldn���t be taken seriously, but luckily I had some great teachers over there at UC Irvine to put me on the right path. Geoffrey Wolff, Michelle Latiolais, and Mark Richard (who if you haven���t read, check out his collections Charity and the Ice at the Bottom of the World). At one point I straight up asked Mark what advice he had for me, and he said something like: ���It���s easy Matt, just make them laugh and break their fuckin��� hearts. Do those two things and you���re doing pretty good.��� I aim for that, mostly.

What’s the view out your window?��

I live on the corner of Sunset and Gardner, above a horn shop, half a block from a fire department. It���s loud. All night long it���s loud. Out one window is the brick of the building directly across the alley. Out another, across the street, is a grey where they used to host poker games on the second floor. For a while I was lock-picking my way onto my roof here to drink beers and watch the cast of characters play cards. It was fun, but didn���t last. Not sure what it is now. But my favorite window to stare out is the circular one in the upper, left corner of the apartment. It���s like the porthole of a ship, but larger. Out that window is nothing but blue.

February 14, 2015

Weisbard+van den Berg+Oswalt: Yes/Yes/Yes.

Top 40 Democracy

by Eric Weisbard

Top 40 Democracy

by Eric Weisbard

This is the book for all of us who are still hung up on the greatness of Something In The Air, Marc Fisher’s genius take on radio, and waiting for something as good to read on the subject. Weisbard’s doing something a good bit different from Fisher, though you’d be foolish to try to rank them: the question he’s crunching on might be something close to why do we sound like what we do, in terms of radio? Better, too: he doesn’t just do some broad-overview thing (though he certainly could: dudes chops are intensest fun to read, and best of luck setting the thing down once cracked in), instead examining the development of this radio format (which is so ubiquitous as to perhaps be invisible or feel like Just What Is, which is another reason the book’s magic) through a selection of artists���the Isley Brothers, Elton John, Dolly Parton���that Weisbard manages not just to make fascinating in their own right, as performers and musicians, but they work together to make his strange, awesome case for him. Sorry. That was a clunker of a sentence in which all I was trying to say is: Top 40 Democracy is not only smart and interesting and fun but insightful, and done in such a way that makes how much you learn from it feel as surprising as discovering Doritos-flavored broccoli.

I have and will contiue to read everything van den Berg writes, and I’ve yet to be let down by her, a sentiment it sure as hell seems I share with the overwhelming majority of folks I know who’ve read her work. Meaning: you should read this. It’s post-apocalyptic, it’s her first novel (after two insanely great collections of stories), and the writing’s the same gorgeous thing van den Berg’s been doing in her other stuff: it both draws you in but feels, to me anyway, almost hard. Sharp. There’s strong sentiment, certainly, but not once will you wonder if the work at hand prioritizes that sentiment: there’s a loneliness in all van den Berg’s stuff, a haunting (ghost is everywhere in this) that makes even the strongest emotional stuff come off as slightly terse. That sounds like criticism, but it’s not: the book’s profoundly emotional by the end���you feel a lot, as reader, even if the characters are perhaps a click or two cooler on the emotional thermostat. That said: yr a fool to miss them, this, all of it.

��

Silver Screen Fiend

by Patton Oswalt

Silver Screen Fiend

by Patton Oswalt

I thought Oswalt’s Zombie Spaceship Wasteland was just incredibly good: I like Oswalt as an actor and comedian, and his writing’s so good and alive it’s a little frustrating that it’s his at this point *third* career aspect. I was less sure about Silver Screen Fiend, at the start: who really wants to read about some dude watching movies? But of course while the book’s a lot of that, it’s much much bigger. Here’s what I mean: Kati��Heng wrote this thing on David Bowie, and one of the things I like so much about it is how it comes close to addressing the weird way we’re held in thrall to the art that opens us so up. We all have stories like this. I wrote letters to authors a decade+ back essentially asking how do you do it, and I spent tons of time just with their books open, around me, like they were incense or something, letting their essences��into the air near me.

And so now there’s Oswalt’s Silver Screen Fiend which is, I think, among the real beauties as far as books-of-worship go. Dude loves movies, which is great, but it’s not just *that* he loves movies, it’s *why*: he wants something from them, wants to be saved by them, wants to transcend because of them. Maybe that’s overheated, but it doesn’t read that far off. And it’s his own earnestness about his affections that betray the bigger, radder, awesome thing he’s actually doing: he waxes for a good bit on the moment Clint Howard pauses in his delivery of a line in Apollo 13 at the start of a chapter about Down Periscope and Oswalt’s single line in it, and you see���again���how carefully the guy watches. He’s not just being entertained: if there’s gonna be a drum beat for the revelatory power of movies, the guy hitting the drum better be a guy able to convincingly find glory almost everywhere. And the guy does: the chapter in which Oswalt and Louis CK are in Amsterdam is as fucking moving as anything I’ve read. If you have ever been, or are, the sort of person who desperately wants to to do some practice but who feels like you’ve got to like earn or get there or whatever, this is the book for you. Just look, look how Oswalt writes this one thing: “I was traveling with Louis CK���a stand-up on his way to becoming a filmmaker by simply shooting a film. I’d probably watched three times the amount of films that guy had seen, so far, in his life. But I hadn’t shot one frame of celluloid.” You finish the book almost cheering, because the life Oswalt was hoping to get to sure seems like the one he’s not leading, and how you couldn’t be happy for him for that, after reading this, is beyond me.

February 11, 2015

Tales of the Father(land)

������FATHERLAND: A FAMILY HISTORY by Nina Bunjevac

������FATHERLAND: A FAMILY HISTORY by Nina Bunjevac

It���s been a minute, really in no thanks to Binary Star (see my last post). I freaking couldn���t read books after that ��� I think I started four and couldn���t finish them just because my expectations of literature were improbably high. Finally though, Nina Bunjevac���s Fatherland: A Family History was the thing to do the trick.

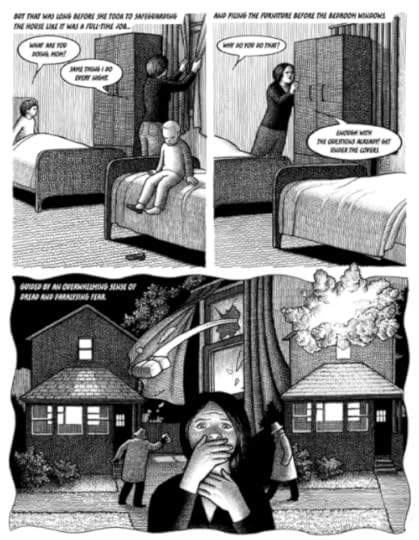

A graphic novel about her family history, especially the history of her father, we first met Peter Bunjevac, her dad, as he stalks down her and her mother, showing up at the doorstep of the apartment her mother had rented to hide from the man. He���s met as an intimidating figure, a looming and dangerous presence, an alcoholic, an abuser and, although it���s not quite clear in the beginning a rebel against the communist life the rest of her family is not seemingly suffering because of.

We met Nina when she���s very young; it���s when she reflects later in life, when she digs into her family history that we see another side of her father. We see the side of him, the Serbian boy displaced in the 1950s to Canada, that lost those he loved early. The side that was orphaned and troubled by the wars and uprisings surrounding his homeland. The side that fell in love with Nina���s mother simply from a photograph. We also see the scary side, the part of Peter that embraced a terrorist organization aimed at destroying the Yugoslav government and its supporters, especially those near him in Canada and the US.

We see the parallel life Nina led, one of relative ease in comparison to her father���s. Born in Canada, Nina���s mother stole her and her sister away under the guise of taking a visit to her parents, leaving their brother Petey at home with their father, staying in Yugoslavia permanently. Living with her mother���s parents, sympathizers for the Communist government, under whom they had never fared better, Nina grew up hearing the noise that her father was a terrorist, a no-good, a traitor while she and her sister thrived in a far more ordinary life than what one would except for a Cold War kid.

It���s a great dichotomy, the parts of this story. Nina���s own tale is simply told, an almost normal childhood, simple growing up with a mother and grandparents who love her, birthday presents, photos taken each season of her and her sister lined up next to each other; while her father���s is a history. We learn of the Serbian nationalist movement through the eyes of it���s displaced citizens, we learn not just Nina���s grandparent���s positive side of communism, but the side of which her father saw, bloody, war-torn, filled with death.

It���s amazing to wonder how Nina reconciles the pieces of her family. Much like this graphic novel, I imagine she must focus on two distinct parts; one that comes naturally and one grown on her through appreciation of her father���s hardships.

(a page from FATHERLAND)

February 3, 2015

Best Book for the Foreseeable Year :: Binary Star

God, is this book extraordinary.

Where do I even begin? The book���s plot revolves around two lovers, a young woman, our narrator, who struggles with bulimia and anorexia, who spins through tabloids and celebrity gossip, and her long-distance boyfriend John, an alcoholic who ignores his illness. Both are resigned to enduring their lovers and their own problems, linked together less by passion than loyalty, than the need to be loved and cared for by someone as fucked up themselves.

There���s SO MUCH in this book to use to declare Gerard the new alt-lit genius of modern times, but what drew me in most on a personal level is the way the girl can depict a woman with disordered eating and depict a strong, smart character in the same body. So many books, most with girls with eating disorders, show the woman obsessed only with vanity. She���s often average intelligence. She���s often anorexic for popularity���s sake only. She often knows exactly what���s she���s doing, seeing her disease as a means to an end like some kind of extreme diet the reader is supposed to use to connect to her with because we���ve all been on diets; this vapid character just takes it to the next level.

Gerard���s character, is, above all else, smart. She���s a scholar of astronomy, filling her mind with the scientific characteristic, of Red Dwarfs and Black Holes and above all else, Binary Stars, ���a system containing two stars that orbit their common center of mass,��� (a worthy metaphor for John and her own life: two stars orbiting a common dream of perfection they���ll never reach.) Her eating disorders are nothing about feeling too fat, not really. They���re about the desire to inhabit less space in the world, to, by becoming so small she nearly disappears, become the biggest star (read: celebrity) of modern times.

She pours over pictures of Nicole Richie���s clothes hanging off her collar bones, She watches Miley Cyrus shake her ass without a speck of fat shifting places. She reads the pounds celebrities gain and lose with a collegiate attention to detail. She devours click-bait articles promising to help her drop pounds overnight with insatiable hunger.

It���s something I don���t talk about often, but undeniably, this book hit me so hard because Gerard has absolutely, head of the nail, hit on what my own year of disordered eating was like. I didn���t think anorexia would make me popular, or even care if it did. More than anything in the entire world, I wanted to take up less space. I hated the way my hips demanded 25 inches while I wasn���t sure I as a person deserved that much space in the world. It���s so eerie to read an author write down some of the messed up thoughts that swam around my own brain, to hear for the very first time, that I���m not the only girl who followed that line of thought.

Even if the whole eating-disorder plot isn���t such an instant turn-on and you���re questioning if you���re gonna connect so strong / enjoy this book so much if you can���t cling onto that thread, I promise you, Gerard���s prose is so entirely beautiful and heart-rendering, you will, like me, be left breathless until you finish the whole thing. Excuse me while I quote some monologue from the narrator making a mental list of wants at excessive length:

���I want to be envied.

���������������������� I want to give out advice.

���������������������� I want to have so many things to say, suddenly there is a book of them.

���������������������� I want to look at the sky and understand.

���������������������� I want to feel small.

���������������������� But important.

���������������������� Massive.

���������������������� But beautiful. ���

���������������������� When I die, I want to have been on the covers of magazines like Vogue and Esquire. I want to have my own sex tape. I want there to be a star named after me.

���������������������� I want to be Paris Hilton six years ago.

���������������������� I want to have pictures taken with telescopes. I want someone to think I���m smart.���

��

HOLY FUCK I can���t get over Gerard���s prose. Just retyping those words makes me envious with her command of the language, with the way she can capture HUGE HUGE emotions with little more than a 20 words.

Geez you guys. If that last quote didn���t make you want to find this book/devour immediately (Two Dollar Radio, again, get on it), stop reading my reviews because nothing I love about writing will be what you like about books, ever.

January 29, 2015

The Best Most Unlikely Trio since… Never

��LOST & FOUND by Brooke Davis

��LOST & FOUND by Brooke Davis

Books and movies that talk about two unlikely heroes that end up staring a hot boy from the wrong side of the tracks and a girl who���s rich but timid who team up and save the whatever or conquer whatever will from here on out definitely not cut it for me. Not after reading the triple-unlikely trio of heroes in Brooke Davis��� debut novel, Lost & Found.

���������������������� Never have the main group of protagonists been more human, more vulnerable and seemingly, the folks themselves that are in need of saving. And maybe the most compelling part of the whole novel is that there is absolutely no outside help, no mysterious kind-hearted being that saves the group at the precise turning point, a mystic guide along the way. These folks are entirely self-sufficient. Enough already, I need to introduce them:

We meet first Millie Bird, the 7-year-old little girl with bright red hair and rubber boots to match. Precocious little thing, Millie collects a ���Book of Dead Things��� chronicling all the dead things she finds in her life including spiders, birds, her dog, and her father. Morbidity aside, the girl knows one thing for sure: Everyone will die some day, even her, even the little babies pushed in strollers, even her best friends.

Next is Karl, the touch typist, as he is called. A quiet man, 80-something Karl prefers keyboards to spoken words, loves the way he can make sentences and voice his most meaningful thoughts by pressing a sequence of squares to form words. He draws keyboards on his table, imagines them on the legs of his wife, Evie, creates them in the air to express himself after Evie���s death. He���s lonely for sure, yet not ready for the assisted care he���s put in after a bout of grief makes him look almost insane, unable to care for himself anymore. He breaks out of the home, though, not ready to settle down and wait to be reunited with his wife.

Finally, there���s Agatha Pantha, Millie���s aged neighbor and the nonbeliever of the group. Agatha���s been holed up in her house since her husband���s death seven years ago, scared to reveal herself because she knows what society wants to do with ���crazy old widows��� like herself. Agatha keeps to a strict routine, waking up at a strict time, measuring new wrinkles on her body and recording them in her Book of Age, measuring the distances between belly button and breasts, other parts of the body, charting the differences over time. Her other time is spent staring out the window, earning her a reputation of a witch of sorts, the owner of the spooky old house the children keep away from.

The story starts with a character we never meet, Millie���s mother. Millie���s mother takes her shopping at the nearby department store, telling her to stay safely in the big ladies��� underwear department, and then leaves. What would a 7-year-old do? Millie waits patiently for her mother���s return. She makes friends with a mannequin. She hides from shop employees. She puts on all the pretty makeup from the perfume counters, trying to mimic the way her mom does it. She gets caught, some women in a stiff outfit comes to take her away, to find her a new mommy and daddy. At a crucial moment, there��� Karl, causing a distraction in which time Millie runs away from the department store, runs all the way home.

Agatha���s perfect routine is ruined by this little girl, Millie, who keeps knocking on her door, asking if she���s seen her mother, asking if she knows what some papers (her mother���s travel itinerary) mean, asking her questions about her life. Agatha puts it together what���s happened, refuses to let either Millie or herself be caught alone and decides she will take Millie to find her mother herself. Again, just in time, Karl finds the two before they board a train to Melbourne, himself haunted by the idea of helping a little girl escape social services only to leave her alone in the world.

TL;DR: Two eighty-year-olds who are both, along social standards, eligible for assisted living care, take it upon themselves to help a 7-year-old girl they���ve just met find her mother who has purposely ran away and abandoned her little girl. If that���s not a group of heroes and an adventure that you want to read, I guess I cant��� help you.

January 26, 2015

Clothes. Music. Boys.

Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. by Vivian Albertine

I didn���t know too much about Viv Albertine coming into this book. I knew she was in The Slits, that she was an icon for women rockers and riot grrrl bands, that she was into all-girl punk before most people were ready for it. I had no idea just how deep her roots into punk, the rise of the 1970���s British Punk Invasion, really ran.

Obvious from the cover, Viv���s some kind of 70���s icon, a Patti-Smith type, messy yet hot in the traditional sense. The books��� name comes from an expression Viv���s mother used all throughout the girl���s high school days: ���Clothes clothes clothes, music music music, boys boys boys ��� that���s all you ever think about!��� For the first 300 pages, it���s completely true. Wandering through school years, kissing boys before even hitting her preteens, going to art school before even discovering the type of art she was interested in (making her own clothing and textile design seemed, more than anything, her passion at the time), Viv was the type who���s energy would only really work for the good of society in something like a band.

Early days, before she learned the guitar (at least, according to her standards, well enough to play it onstage), are an especially fascinating read for artists like moi still struggling to figure out what junk they actually want to do. During art school, Viv meets the pre-famous Mick Jones (soon to be of The Clash), the two bum around town in an almost British replay of Patti Smith���s Just Kids (I swear, last time I compare her to Patti Smith for another 200 words), Viv���s there as Mick forms and breaks bands, desperately seeking people to take the music as seriously as he does. Watching a group onstage, Viv comes to the realization being in a band is what she is meant to do, buys a guitar and begins to teach herself to play.

Enter Sid Vicious, or well, Sid before he was known as Vicious. Sid agrees to form a band with Viv before even hearing the girl play, knowing he needs people in his band who have that perfect punk look, like the other two girls he���s recruited, a chick on the drums named Palmolive and on the bass, Tessa. So starts Viv���s first band, The Flowers of Romance.

If it feels like I���m just name dropping punk legends Viv hung out with, I promise the book does it so much more. No even name dropping for the sake of ���Look at all these famous people I met!!��� Viv Albertine was simply, truly in the inner circle of all things punk.

Time flies by, charted by the changing looks Vivian tries on: tee shirts with screen prints of breasts and nipples, outfits from a used costumes shop, booty shorts worn as pants, all things original, still pieces girls would fear wearing outside today. Soon enough, Viv has formed a band with a 14-year-old child prodigy of the punk world, Ari Up (as she calls herself, liking the way it comes out like ���Hurry Up��� from Brit���s mouths), and that same Tessa and Palmolive from her old band with Sid. The group is magic. The Slits are off and it suddenly clicks.

More than anything, the tales of her days as a working punk legend impress mainly because of how much restraint the girl shows through it all. The girl takes herion only once (with Johnny Thunder (name drop again #sorrynotsorry)); takes on the role of an almost manager, getting the girls up on time, making sure they���re all there at rehearsals, overseeing the band���s image in front of the corporates at record labels; takes care of wild and rebellious Ari in a big-sisterly fashion. For being a punk, Viv���s time in The Slits seems so much calmer than anytime before maybe her middle school days.

Second half of the book: The band is broken apart as almost all good bands are. Viv wanders through life briefly teaching Aerobics classes, listening only to talk radio, marrying a Biker and finding new meaning through the role of motherhood.

Wouldn���t you know it, being apart from music didn���t take.

While the first half of the book is a mouth-watering good look into the early formations of punk, what it was like to be at the Sex Pistol���s early shows, how a girl���s supposed to dress for the occasion, the second half explores a whole different kind of bravery: the courage it takes to overcome depressions, social expectations, to get out there and DO.

Much in the same way Carrie Brownstein summarized the experience of seeing Viv perform live in the late 2000s, I end with the question:

Read anything punk in a while?

January 22, 2015

I’m An Idiot: Don’t Fear Miranda July

���������������������� I think it’s mostly that I’m actually scared of Miranda July, frightened by her work, somehow. I’m not sure. Her story “Swim Team” was I think the first time I actually experienced actual work of hers instead of just getting second-hand commentary from friends, and that was January 2007, and that story still knocks me absolutely flat, is so gorgeous and sad and touching and sweet I feel silly every time I see it and realize I haven’t read it recently enough. This is all by the way me trying to process why it was I was so hesitant to read July’s The First Bad Man, her novel that’s just been released, and the truth is: I have no legitimate or good reason to be so hesitant. If you’re like me you likely have had more exposure to Miranda July the person than her actual work, which is too bad, just in that the signal:noise ratio’s all wacky when an artist’s work is grounded too much in Who the Artist Is. Plus I can at least admit this: Miranda July comes off as precious. There is���or seems, to this reader���an almost willful naievete and innocence to her that just makes my skin itch (this is me trying to admit to many levels of assholery; I’m not saying this stuff because any of these aspects of her are *true*).

���������������������� I think it’s mostly that I’m actually scared of Miranda July, frightened by her work, somehow. I’m not sure. Her story “Swim Team” was I think the first time I actually experienced actual work of hers instead of just getting second-hand commentary from friends, and that was January 2007, and that story still knocks me absolutely flat, is so gorgeous and sad and touching and sweet I feel silly every time I see it and realize I haven’t read it recently enough. This is all by the way me trying to process why it was I was so hesitant to read July’s The First Bad Man, her novel that’s just been released, and the truth is: I have no legitimate or good reason to be so hesitant. If you’re like me you likely have had more exposure to Miranda July the person than her actual work, which is too bad, just in that the signal:noise ratio’s all wacky when an artist’s work is grounded too much in Who the Artist Is. Plus I can at least admit this: Miranda July comes off as precious. There is���or seems, to this reader���an almost willful naievete and innocence to her that just makes my skin itch (this is me trying to admit to many levels of assholery; I’m not saying this stuff because any of these aspects of her are *true*).

So: I was and am anxious about Miranda July, which is insane and stupid, because what happens when I read her is I just get wrecked and wish I had the audacity she does. I got her The First Bad Man maybe two weeks back and sort of like (even though I’d requested the book, seriously) snickered or something about it. I’d been planning on reading it to enjoy not liking it (a soul-calcifying experience, certainly, but not without its ugly joys), a schadenread. Whatever. I don’t know why I keep trying to explain it all away. Her stuff makes me jittery (I wish I had some legit reason to have felt this anxious toward her. I think part of it’s that her face is almost always totally lineless���no laughing, no squinting; her face is so wide open it makes me anxious, makes me long for some screen).

Anyway, what happened was I started reading The First Bad Man and when my wife asked later that night once the daughters were asleep what I was reading I explained what I could: that it was this book that I’d been expecting to hate but was now so caught up in and moved by I felt weird and weirdly trapped. What I was getting was the experience we all hope for from art, of course: some shift, a changing, but my own BS and neuroses about July (who, again, wrote one of the all-time best stories ever, and why that’s not enough for me to overlook her so-open face and her [to me] weird art pieces [but it’s not like I’ve ever been to any of her performances or seen anything other than the two Big Release movies]) had gotten so in the way. A big temptation in reviewing or talking about this book is just to post this link to Ms Lauren Groff’s NYTimes review of the book and say YES EXACTLY YES, but there’s more to it than that.

What The First Bad Man actually did, to me, was blast��me open astonishingly. It’s the story of Cheyl, an early-forties severely alone woman who works at Open Palm, a women’s self-defense center which now makes its money selling self-defense-as-exercise DVDs. Her life’s recognizable to anyone who’s lived alone by choice for awhile: she’s maybe unnaturally fond of her systems (for instance using only one set of dishes, ever, washing them out every time post-use), which systems, she admits, prevent her from going off the rails, peeing in cups, letting the dishes pile up. It’s early on that this aspect of Cheryl’s revealed, and it’s the book’s whole heart: when alone, it’s hard to know What To Live For. That sounds silly, but, at least for Cheryl, it’s true. She’s ‘in love’ with a guy twenty years her senior, Phillip, with whom she believes she’s had lots of experience in past lives, and she believes there’s be more ardor and connection between the two of them eventually, if not in this life than later, and so there’s this thing of like: well, what’s the point of this life, right now? What’s the point of waking up? That shouldn’t sound depressive or anything: it’s just a matter of clarity and purpose. Maybe the point of this life is to let Phillip explore other relationships, and for Cheryl to learn how to be more open to other people’s experiences.

What happens to Cheryl is an upside-downing in the form of her bosses’ daughter Clee, a busty blond who moves in, disrupts everything in Cheryl’s life, and who then���this is where the book gets weirdest and, I’d imagine, will be hit hardest by whimsy in reviews (or quirky, or any of those other backhands)���begins a relationship with Cheryl, a hugely strange and equally hugely satisfying relationship predicated on scenes of violence (they act out scenes from Open Palm DVDs) and then this whole other realm of Cheryl’s own internal fantasizing, about which the less said the better (not because it’s gross���fantasies don’t really stick to the metric of gross/not gross���but because explaining it makes it sound so silly [here: Cheryl begins to spend a ton of time masturbating as she imagines herself as various men having sex with Clee] whereas when you read it, in the book, the fantasizing feels and reads and sounds not just emotionally-logical but necessary, the exact sort of move you’d expect/need Cheryl to make). What happens, eventually, is something like love, and also Clee gets pregnant, and PS this whole time there’s this whole other thing happening throughout the story, and the thing is: Kubelko Bondy, which is the name of the ur-baby Cheryl’s always scanning other babies hoping to find (go with it for a minute: she believes there’s some True Connection she feels to a kid, and that the kid’s soul is flitting around, somehow, baby-to-baby, and she is intentional in seeking out the eyes of babies, seeing if they’re Kubelko, and as weird as it sounds written flatly like this know that it reads and feels in the novel totally legit. Strange, sure, but legit [quick: write down all the things you do that yr sure are totally normal and not strange, and then share the list with someone]). The plot though isn’t really what you’re reading this book for: you’re reading it to be in the presence of Cheryl, to experience and see with her, to be offered what feel like sudden blossoms of wisdom or beauty or connectedness from ingredients you likely wouldn’t (I at least didn’t) guess could combine into such. Cheryl’s not alone at the end, by the by, which matters just in that the book will make you perhaps sniffle or cry a little, and further: if you’re a recent parent (July is, as am I), there’s stuff in here that’s gonna rip you up in the good ways.

Anyway: plenty. Miranda July is the Real Thing, and I’m a fool for each anxious minute I spent unsure if I was willing to enter into her fearless, strange, humbling, powerful work. One of the things she does is she seems entirely judgeless: Cheryl in The First Bad Man would be among my greatest fears to have to deal with���endlessly annoying, silly, foolish, etc���and yet in the book she’s perfect, someone loved enough by her creator to have her flaws shown hugely. It’s an incredible thing. Read this book, please. Read The First Bad Man. It’s so beautiful. It’s so strong. It’s so, so good.

January 18, 2015

Show Me Your Icon

Editor Amy Scholder, longtime editor of two of my favorite presses (Feminist Press and Seven Stories Press), invites us to take a look into the smarter side of celebrity obsession in her newest collection of essays, Icon. From the age of six, watching her mother cry over Judy Garland���s death, growing up with an obsession with the Manson family���s girls, talking to a friend and colleague about the women���s love of Amy Winehouse only to discover the person had only ever heard a single Winehouse song, Scholder says ���I���ve always thought that the weirdest thing about celebrity culture is the level of intimacy we feel with people we don���t know.���

Celebrity worship is something I���ve been struggling with a lot lately ��� not so much that I���m on the side of worship, but I���m in a place where I struggle to allow myself to admire people I���ve yet to met no matter how big a fan I am of their music or their writing or their social activism, etc. There���s something about creative output ��� it ultimately shows a person���s BEST. It���s easy to become obsessed with that best part of them and forget that surrounding it is this messy, slightly above average, human like the rest of us.

Luckily, the authors of Icon���s essays have moved beyond sophomoric love affairs with celebrities the way people grow out of creating Taylor Swift fan blogs or dedicating Twitter accounts to Kim Kardashian. Theirs is mainly an academic love; a love of the, importantly, output of the celebrities rather than a shameless obsession of the person themselves.

A short summary of the authors involved / the icons profiled: Mary Gaitskill waxes poetic on the mysterious Linda Lovelace, and herself is later admired by Zoe Pilger. Riot Grrrl Johanna Fateman of Le Tigre outlines her personal plans to write an entirely separate book about tough and gritty Andrea Dworkin. Jill Nelsons (author of Sexual Healing) reflects on her startings of sexual freedom as narrated through Aretha Franklin���s song ���Respect.��� Rick Moody, cited music laymen fanatic thanks to his book On Celestial Music, again takes an in depth look on Karen Dalton. Hanne Blank (A Girl���s Gotta Eat) wonders whether or not her icon MFK Fisher���s food writing and acclaim will ever be something she herself can achieve without Fisher���s thin privilege. Danielle Henderson (creator of Feminist Ryan Gosling) talks about the moment of reading bell hooks when feminism finally felt like a space open for her as well. Trans-author Justin Vivian Bond remembers how as a teen she would project herself and her own chances to create the beautiful life she craved onto Este Lauder model Karen Graham. Green Girl author Kate Zambreno wanders through New York, seeking for the Edie Sedgwicks running their nylons through the town, the Kathy Acker���s taking a stand.

What really makes Icon work is the way each author takes on explaining their icon, what they meant and how they���ll live on. Some authors, like Rick Moody and Mary Gaitskill, take a straight biographical look into their icons. Danielle Henderson and Zoe Pilger harldy look into the lives of their icons at all, focusing solely on the way their written words touched their lives. Johanna Fateman, Jill Nelson and Justin Vivian Bond trace the connections between themselves and their icons, where their stories connect and what their icons have taught them. Hanne Blank does almost the opposite, at first professing her love for MFK Fisher, then realizing the advantages given to Fisher because of her beauty are mountains she herself may never be able to overcome. Kate Zambreno, perhaps most uniquely of all, holds a written s��ance with Kathy Acker, attempting to talk to her icon, to learn how the women avoiding selling in to literary boredom and stale publishing.

Celebrity worship is messy. As many of the authors admit, even our greatest heroes say things and do things we can���t agree with. Even our icons let us down. The fact of the matter is, our heroes, whether they be the same icons represented here or even the authors of the essays themselves, are all messy people, only more accomplished than us.

January 7, 2015

What’s Up with Her???

Her starts with a flash of mystery, a dark sense something���s askew despite it���s calm and cool setting. Oddly enough, the first things I read about the book online told me this would be a tale of friendship and motherhood, which really, seems an odd way for whoever wrote that to frame the book. It soon becomes clear ��� one woman is seeking friendship, the other is out for revenge.

First, we meet Nina, an artist, mother of 17-year-old Sophie, a collected, put-together woman. Nina���s reached success selling her art to the rich folks sent to her gallery, generally has everything in her life perfectly together, including the perfect boyfriend, Charles and the effortlessly clean household.

And there���s Emma, the frazzled but beautiful mother of a little boy, pregnant with another on the way. Emma���s recently left a job in television to take care of her son, still trying to adjust to the fact that mother is her only job now. Her home is a mess, like any other mother without a nanny���s usually is, her husband is distant, unable to pick up on her signals that she���d like some help, and more than anything, she���s lonely, wanting some time spent in conversation with someone over the age of 5.

The two meet on, what it seems to Emma, a fortunate coincidence. Nina returns Emma���s lost wallet, delivering it directly to her home. Both women note how different they seem from one another ��� one dark in the places the other is light ��� yet both seem drawn to one another. Emma, obviously, in admiration of this woman with enough free time and enough heart to do kindnesses unto strangers. Nina is drawn for another reason, one we cannot quite figure out, but one we immediately sense, is not so noble.

Months later, their paths cross again. Now with a daughter in tow, Emma loses track of her son at the park. Swings the daughter for one minute, the boy���s out of sight. Within 50 minutes, she���s reconnected with him at the police station, brought there by none other than Nina, who found the boy out on her front step playing with the cat. Emma���s even more eternally grateful, insisting on meeting Nina again to express her gratitude.

Nina relishes in becoming a part of this woman���s life. The rest of their families ��� Emma���s husband, Nina���s boyfriend and daughter, don���t quite understand what draws Nina to Emma so, why this woman is suddenly babysitting the children, cleaning her house and inviting Emma���s family to her plush summer home.

Her works simply by the control in Lane���s words. Never spilling a secret too soon ��� I think we figure out just WHY Nina is so obsessed with Emma in the last 20 or 30 pages of the book ��� the story moves along quickly, thrillingly. Alternating chapters, we hear the side of Emma, falling into what seems the perfect friendship despite the burdens of young children. Then, we hear the side of Nina, her darker ulterior ways of ���helping��� Emma out.

Her is ���Mean Girls��� on a larger, darker scale, ���Heathers��� without the campy murders. It���s tense. You won���t be able to put it down for a minute until you figure out what Nina is plotting.