Andrew Collins's Blog, page 24

March 26, 2013

I want to go to there

As a fan of both James Nesbitt and Ireland, I was always bound to kick off this week’s Telly Addict with James Nesbitt’s Ireland on ITV, although it wasn’t quite the paradise I’d hoped for. Also, although this isn’t a request show, I had the Wyoming-set cowboy detective series Longmire on TCM recommended me to me a couple of weeks ago, and I checked it out. In order to counterbalance last week’s BBC-only Telly Addict, I went to the new Boss on More4, in which Kelsey Grammer finally emerges from the shadow of Frasier by swearing and shouting and twisting a political opponent’s ear (see: clip); tapped a toe to the impenetrable return of Treme to Sky Atlantic; and loved the second ever live episode of the otherwise flagging-a-bit 30 Rock on Comedy Central. Next week, I promise to review Paul Hollywood’s Beard on BBC2.

As a fan of both James Nesbitt and Ireland, I was always bound to kick off this week’s Telly Addict with James Nesbitt’s Ireland on ITV, although it wasn’t quite the paradise I’d hoped for. Also, although this isn’t a request show, I had the Wyoming-set cowboy detective series Longmire on TCM recommended me to me a couple of weeks ago, and I checked it out. In order to counterbalance last week’s BBC-only Telly Addict, I went to the new Boss on More4, in which Kelsey Grammer finally emerges from the shadow of Frasier by swearing and shouting and twisting a political opponent’s ear (see: clip); tapped a toe to the impenetrable return of Treme to Sky Atlantic; and loved the second ever live episode of the otherwise flagging-a-bit 30 Rock on Comedy Central. Next week, I promise to review Paul Hollywood’s Beard on BBC2.

March 22, 2013

How does it feel to be the father of 172,907* dead?

Who’s old enough to remember the Falklands War? I know we’ve experienced some sabre-rattling about the Malvinas from the Argentine and British camps of late, but it seems unlikely that anybody would go to war over their sovereignty in 2013. I hope not, anyway. Having grown up under the long shadow of the Second World War (my parents were born during it, my grandparents lived through it, one of them fought in it; it influenced the films we watched, the toys we desired and the games we played), and, as a boy, having been fascinated by all aspects of the 1939-45 apocalypse, it was surreal in 1982 to live in a country that was at war, with our tank-straddling Prime Minister sending something called a “task force” to this contested 12,173 square kilometres of dry land in the South Atlantic to repel a South American invader.

There was a war! Alarmist rumours went around school that conscription might be introduced, and, as a paranoid 17-year-old, I had to process what that might mean – even though it was highly unlikely. Anyway, around 900 people died in that stupid war, hence the title of the subsequent 1983 single by anarcho-syndicalist squat-rockers Crass: How Does It Feel To Be The Mother Of 1000 Dead? In many ways, the title was enough, not that it would have robbed Margaret Thatcher of any minutes of sleep on her notoriously short nights.

I hadn’t even fully assimilated my politics at that point, and was still living under the long shadow of my Dad’s, but my eventual conversion to left-wing idealism was taking shape somewhere inside my brain, and it was the accumulation of persuasive signposts like the title of that Crass song – and the collage that packaged it – that helped to build it.

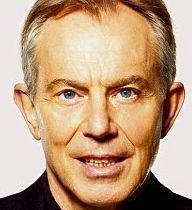

Since 1982, the country I live, pay tax and vote in has been involved in a number of other wars, invasions, air strikes and “humanitarian interventions”, notably the Gulf War of 1990, and the Iraq war, which began with the illegal invasion in 2003 and was never officially declared. We are currently “celebrating” its tenth anniversary, and this means that Tony Blair’s face is back in the news, albeit mostly in montages. In Iraq, which is pretty much universally acknowledged to be in a far worse state than it was before we invaded it, the anniversary was marked by bombs killing 56 people and injuring 200 in Shia areas.

I say “we invaded it” – I didn’t invade it. Irag was officially not invaded in my name, because I marched on February 15, 2003 to say so, along with millions of other sane souls around the world. Ours was the largest march in London’s history, even according to the police’s massaged-down figure. (I also marched against the invasion of Afghanistan two years earlier, on October 13, 2001.) When I look back, I feel proud that I cared enough to march, although it also makes me a little sad, as the marching spirit was beaten out of me by the feeling of democratic powerlessness I felt after Operation Iraqi Freedom (cheers) kicked off regardless at 5:34 am Baghdad time on 20 March, 2003 (9:34 pm, 19 March EST).

What optimism I must have had in 2001-2003. I did not decide to march; I had no choice. I love the foregone conclusion of the way I felt then. I dislike the lack of fight in me ten years later. But there is, at least, one man to blame. And I still hold him to account for what happened: the Christian sense of destiny behind his dead eyes as he told us that Saddam Hussein could attack us with only 45 minutes’ warning with weapons of mass destruction that he was definitely hiding in Iraq. I didn’t believe a word Tony Blair or George W Bush said. And although this might have been viewed as kneejerk leftist aversion, history tells us that I was right not to. That he continues to stand by his decision to follow Bush into Iraq to help assuage his Oedipus complex rankles with me. He always says he “regrets” the loss of life, but not the decision to do the thing that caused the loss of life.

* He may or may not be the father of 172,907 dead, as a definitive figure is impossible to put your finger on. It could be more, it could be less, but is probably more. This is the best current estimate of the Iraq Body Count project – and of course it’s recently shot up after the violent protests to mark the tenth anniversary – and it’ll have to do. You might say I’m being melodramatic dredging up the Crass lyric, but the whole sorry, disgraceful episode offends me, yeah? And the rich, tanned, our-man-in-the-Middle-East Tony Blair really needs to get out of my sight, please.

And, as previously declared, I am reading Jason Burke’s The 9/11 Wars, a pretty exhaustive account of the mistakes, assumptions and dangerous strategic miscalculations made by the invading forces in Afghanistan and Iraq (not to mentions the abuses and crimes committed). We’re just at the point in 2006 when the author declares “the beginning of the end” for bin Laden loyalist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s archaic “Al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia” network, whose worryingly broad stated aim was to “bring the rest of the Middle East and potentially the Islamic world within the boundaries of a new caliphate.” In November 2005, he claimed responsibility for suicide bombs that killed 60 people in three hotels in Amman in Jordan (including 38 members of a wedding party), after which opinion polls showed that Jordanians turned against the Iraqi insurgents, indicative of a wider rejection. If Burke’s book tells us anything it’s that the country, and the region, fell into factional chaos after the US/UK invasion, and took until 2006 before the death toll abated. Claiming strategic victory for the American “surge” strikes me as patting yourself on the back for removing some of a red wine stain you made by pouring white wine onto it.

So, you’ve got my kneejerk reaction, and you’ve got my well-read, analytical reaction. I’ll give the final words on this blood-stained anniversary to Crass.

Your arrogance has gutted these bodies of life

Your deceit fooled them that it was worth the sacrifice

Your lies persuaded people to accept the wasted blood

Your filthy pride cleansed you of the doubt you should have had

You smile in the face of death ‘cos you are so proud and vain

Your inhumanity stops you from realising the pain

March 19, 2013

Austerity measures

The vagaries of the release schedule and a low-key, post-Oscars weekend at the Curzon gave me two films in two days that depict life on the geographical margins of society. One is set in a remote region of Romania, the other in the Highlands of Scotland, both windswept and austere. Both films are compelling and make capital from the unremitting bleakness of their environment, physical and figurative. I like it when this happens.

Beyond The Hills is Cristian Mungiu’s belated follow-up to the internationally acclaimed 4 Months, 3 Weeks & 2 Days, which helped put Mungiu at the heart of “the Romanian New Wave”, a movement arguably kick-started by Cristi Puiu, whose The Death Of Mr Lazarescu won at Cannes in 1995 (as did 4 Months) and “put Romania on the map,” as they say. Puiu also made Aurora, which was one of my favourite films released here last year. Every Romanian film I’ve mentioned so far has been bleak, critical, illuminating and vital.

It’s hard to meaningfully sum up a national cinema without generalising wildly, but Romania’s emergence from life under a totalitarian Communist dictatorship clearly coloured its filmmakers’ individual visions, which understandably tend toward the bleak and the realist. The “shock doctrine” that shakes a society out of itself after a seismic change usually refers to a move into market capitalism, and this often looks better on paper to economists – and perhaps to freshly unyoked citizens – than it works out in practice. (Lazarescu and 4 Months were set at the time of the Ceausescu regime and served a cathartic purpose.)

Beyond The Hills, which won Mungiu another laurel at Cannes for his screenplay and for his two lead actors, is set after 1995, as the Euro is referenced, but – I gather – before 2007, when Romania entered the European Union. (One of the characters has just returned from the economically strong Germany, where she has been working, and where she wishes to lure her friend, while a more reactionary priest who has never left Romania denounces the licentious behaviour of “foreigners”.) Certainly, we are shown glimpses of a modern, or modernised, Romania – a smart cafe, a well-equipped hospital, the priest using a mobile phone for emergencies – but the meat of the story takes place in an Orthodox monastery with no electricity, heating or running water, which seems willingly marooned in the past.

Into this sealed world of prayer and candlelit plain living comes Alina (Cristina Flutur) in her conspicuously “outside world” outfit of blue tracksuit top, which sits in stark contrast to the chaste, all-black robes and headgear of the nuns, including Alina’s best friend Volchita (Cosmina Stratan), now a devout and humble novice. While Volchita seems at peace, Alina is at war, with herself perhaps, or her desires? She is not an immediately sympathetic character – demanding, selfish, hysterical, stubborn – but when pitched against the insular, controlling paranoia of the monastery, at times she feels like an avenging angel, albeit a flawed one. Flutur and Stratan deserved their Best Actress accolade at Cannes; they are utterly believable as friends.

The monastic mountain setting immediately recalls the equally austere and precise French film Of Gods And Men, one of my favourites of 2010, set in an Algerian monastery in 1996. It too dealt with a crisis, but one from the outside – Islamic militants. In Beyond The Hills, the crisis is within. It is Alina, who refuses to accept God and descends into selfish, petulant anger at the newly-found faith of her now-lost childhood friend – and, it is implied, lover. This is only a 12A, and nothing is shown, but when Alina first comes to visit Volchita, she asks her to soothe her back with rubbing alcohol, a medical treatment that clearly has sexual undertones, and the pair are shown sharing warmth in bed together. When Alina’s square-peg status erupts into something seemingly demonic, the film takes a dramatic turn, and I’ll reveal no further details.

Beyond The Hills is long (over two and a half hours), slow, and deliberate, and, to borrow Philip French’s astute description, “neutral”. As with Aurora, and 4 Months, when, say, a character leaves a room to fetch something, there is no edit: we wait for them to return. The way of the monastery means that “Papa” (Valeriu Andriutã), the dominant priest, is frequently asking one nun to go and fetch another, and we must wait in real time for that to happen.

You could edit this film down to 90 minutes without losing any of the story beats, but it would be less of a film in so many other ways. The unhurried pace simply points up the urgency of the mounting crisis, and the bungled way in which it is handled, not just by the priest and his nuns – who at one point become a comically incompetent gaggle – but by the hospital staff, and by Alina’s former foster parents. It’s not a film about religion; rather, the deficiencies of the system in Romania. The final shot, which again I won’t ruin, is utterly spellbinding; ingenious in its slow, symbolic minimalism.

Let’s make another visual rhyme out of these two films.

So, to Shell, which is the first feature of Scottish writer/director Scott Graham, who expanded it from a short of the same name. More hills. This time, the hardscrabble existence is not about tilling the recalcitrant land, nor drawing its water up a well, but serving the motorists who pass through a remote stretch of the Highlands. With fuel, essentially – Shell (another amazing performance, this time from newcomer Chloe Pirrie, who was in the most recent Black Mirror) and her epileptic father Pete (the always transfixing Joseph Mawle) live and work in this jerry-built petrol garage, where he also turns cars into scrap, and theirs is an existence just as sealed-off and meagre as the nuns’ in Beyond The Hills.

Again, in an unhurried, real-time fashion, we get a vivid picture of their life together, their daily routine punctuated with the occasional car or lorry, stopping to fill up, and, in the case of the regulars, to chat. Human contact seems vital to the teenage Shell, who is at ease with Michael Smiley’s stoic, smiley divorced dad, on his way to see his kids, and with Iain De Caestecker’s Adam, a potential suitor who works at a nearby sawmill. But her first loyalty is to her dad. We see her tenderly nurse and comfort him through an epileptic fit on the kitchen floor, immediately setting her up as the carer. She cannot escape because of his needs, and because of her loyalty. (We discover that he literally built the house, although as pointed out by another reviewer, the fading interior decor suggests it hasn’t been tended to much since his wife and her mother left.)

This is a slice of life, just as, say, Aurora was. Life is simply going on, before our voyeuristic eyes. Pete professionally butchers a deer killed by a couple’s car on the road, skinning it in the garage and chopping it up into cuts for the freezer. He seems a primal man, but he is rendered helpless by the regular seizures, about which you sense he feels embarrassed, as his dominance as a father and as a man is lessened by them. That he and Shell’s relationship borders on the incestuous is something that’s subtly and never melodramatically explored as the story unfolds, although “story” is laying too much responsibility as its feet. Drivers come and go, but Shell and Pete stay in place, fixed, pinned, incarcerated by their situation, stripping cars and skinning deer and reducing them to their component parts.

Although the glacial pace and minimalist narrative of Shell are persuasive, this is a much shorter film than Beyond The Hills, and, almost as if the budget ran out, it makes something of a mad dash to the denouement, which is disappointing because of the hurry with which it arrives. I could have watched for at least two hours. There’s also a misunderstanding that ignites the final dramatic twist, and it felt a bit underpowered when all before seemed so deliberate and realistic. Scott Graham is clearly a talent, and he frames the environment with an artist’s eye. You can hear the wind whistling through the drafty house throughout, and the sense of place is intensely affecting. Unlike the Romanian monastery, there is electricity, and it brings news of the outside world when Shell dances with abandon and joy to Walk Of Life by Dire Straits, making you wonder if the film’s set in the past. When Michael Smiley’s Hugh brings Shell back a pair of jeans from the city as a courtship gift disguised as something more paternal, it’s as if we’re in Soviet Russia.

Even though the ending is disappointing, Shell is well worth a look. It’s almost as if both filmmakers are trying to take us somewhere. They certainly both appreciate the dramatic and figurative power of inclement weather. One character says to Shell, by way of small talk, something like, “When’s this winter going to end?” In Beyond The Hills, snow falls and cuts the monastery off even more decisively from “civilisation”.

It was a wet weekend in London, and these films really suited my mood. It’s great to see a British film coming on all East European, though.

This is my quest

This week’s Telly Addict has been brought to you by Into The Woods, a bracing new book about screenwriting, with particular emphasis on the craft of storytelling for TV, by my former boss John Yorke, who produced Collins & Maconie’s first ever radio programme in 1993, Fantastic Voyage, and then became my executive producer on EastEnders some years later, and then Head of Drama at the BBC (he’s now hopped it to the private sector). Anyway, it’s published in April, I’ve been devouring a preview copy, and it currently infects the way I view TV. Henceforth, take copious notes as you view my analytical reviews of the monomythic Masterchef on BBC1; In The Flesh on BBC3; Prisoners’ Wives on BBC1; and It’s Kevin on BBC2. There is no masterplan here, they just happen to be all BBC shows. (I say there’s no masterplan, but as John’s book proves, all stories subconsciously adopt the same structure, so even Telly Addict has a quest, a midpoint, an inciting incident, a protagonist and antagonists, a prize, a resolution and a symmetry between beginning and end. Check it out.

This week’s Telly Addict has been brought to you by Into The Woods, a bracing new book about screenwriting, with particular emphasis on the craft of storytelling for TV, by my former boss John Yorke, who produced Collins & Maconie’s first ever radio programme in 1993, Fantastic Voyage, and then became my executive producer on EastEnders some years later, and then Head of Drama at the BBC (he’s now hopped it to the private sector). Anyway, it’s published in April, I’ve been devouring a preview copy, and it currently infects the way I view TV. Henceforth, take copious notes as you view my analytical reviews of the monomythic Masterchef on BBC1; In The Flesh on BBC3; Prisoners’ Wives on BBC1; and It’s Kevin on BBC2. There is no masterplan here, they just happen to be all BBC shows. (I say there’s no masterplan, but as John’s book proves, all stories subconsciously adopt the same structure, so even Telly Addict has a quest, a midpoint, an inciting incident, a protagonist and antagonists, a prize, a resolution and a symmetry between beginning and end. Check it out.

March 12, 2013

In the same casual manner

Yesterday, this man was sentenced to eight months in prison for perverting the course of justice. He is Chris Huhne, one-time Liberal Democrat MEP, MP, Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change in the coalition government and something of a “star” of the party. (He ran Nick Clegg pretty close in the leadership battle in 2007, and, if you included postal ballots, which they didn’t, he would have won.) I think we’re all well aware of his crime: after being caught speeding in 2003, when he was a Member of the European Parliament, he convinced his then-wife, Vicky Pryce, also convicted yesterday, to “take” his points by claiming she was driving when the vehicle was photographed by a speed camera. (Ironically, he was banned from driving for three months in the same year for driving while using a mobile phone and she had to “drive him around”, the very inconvenience their deception was designed to prevent.)

Huhne, who pled “guilty” at the last minute, and Pryce, who pled “not guilty”, both received the same sentence. As we speak, they are being “processed” at Wandsworth Prison, which nobody says is going to be a lot of fun for either of them, but will then be moved to open prisons for something like six weeks, after which they will be released, but put on house arrest for the remainder of their sentence. He is no longer an MP, but, after legal costs, he will still own seven properties, and certainly went into prison with a fortune of around £3.5 million, much of that earned when he worked in the City, before entering politics. (When he was the Lib Dems’ environment spokesman, he was criticised for having shares in “unethical” companies.)

For better or for worse, I have a kneejerk reaction against the following types of people:

MPs and other elected representatives of either gender who lie

Men who abuse power (and it is so often men)

Men who leave their spouses and their families for a younger woman (essentially because it’s such a cliché, especially if the affair is conducted “at the office” – what is this, a 1970s sitcom?)

Male politicians who give the impression of being a “family man” in order to get elected – as Huhne did in Eastleigh with the family snapshots in election material (“Family matters to me so much – where would we be without them?”) and his public displays of unity at the ballot box with Pryce – when they are in fact conducting an affair in secret and plan on leaving their wife and children when they get in

Here’s where I stand:

I do not think putting Huhne, or Pryce, in prison, even for a couple of months, is a good use of taxpayer money. I stated this on Twitter and, as usual, enraged some who felt I was letting him off the hook. I mentioned “his sort” (which is kind of all of the above), which was misconstrued as “posh/rich/establishment” and taken to mean that this “sort” are “too good for prison”. Far from it. If I really thought that the £800 per week we’ll be paying to keep Huhne in an open prison would change him, I’d consider it. But to my mind – and this is a pure hypothetical as the sentence has been passed – community service would be a far better option. It would cost us less. It would – shall we say – inconvenience Huhne more. And it would put something back into the society he clearly felt he was above.

I state these facts only because, as usual, I felt I was struggling to make my views heard in the ridiculous medium of Twitter. I do not believe that the purpose of community service is “humiliation”. Although I do believe that picking up litter or washing police cars would be humiliating for an arrogant prick like Huhne. (I have never met him, but I know a lot more about him after the court case than I ever expected to know, and I don’t much like the sound of him. Do you?)

Had I been on the jury, I feel in my bones that I would have been less harsh on Pryce. She is, on paper and in a court of law, as guilty as him for the misappropriation of those speeding points, but it certainly sounded like she was “maritally coerced,” which was her defence. A couple of weeks fewer in prison, at least? She is anything but “the little wife”, and she certainly put all of this into motion by going to the press after she was dumped by Huhne, but she seemed at the time to me to be the injured party. It’s hard to know for sure, but that’s the impression I took away from what remains a sordid affair.

Chris Huhne is now hated by his ex-wife, and, presumably, by the three kids he had with her during their 26 years of marriage. That’s their private business. I only care about him because he is an elected official who asked the electorate to trust him and to represent them. Call me a dreamer and an idealist, but I expect Members of Parliament to be honest and to set a good example. I do not give a toss whether or not they are happily married, or have families, those trappings of apparent trustworthiness are not as important to me as they are to many other voters; I merely expect them to do their best, to be upfront with those who elected them, to put their constituencies first, and not to behave as if it’s one rule for them and another rule for the rest of us.

Much of my reaction to this story, which can go away now, is rooted in my own prejudice – and no doubt coloured by the disgust I feel for the Liberal Democrat party since they enabled the worst Tory government in history to take power, while abandoning all their promises – but I am being honest about that, and anyway, nobody elected me. Most people who drive have broken the speed limit. Many have points on their licence. Equally, for most people, a fine and a driving ban would be deterrent enough not to sail too close to the wind too often. When the offender is Chris Huhne, a man with a personal fortune and a property portfolio (two words that really shouldn’t go so casually together), a fine and a ban aren’t going to be enough. He needs to be made an example of, I agree, but sticking him in an open prison isn’t going to do the trick.

And we don’t put people in the stocks any more.

Police line

On this week’s Telly Addict, a clash of the Kudos-produced titans: the eight-part Broadchurch on ITV and the five-part Mayday on BBC1. It’s an unfair fight, as previously established, as I’m reviewing one episode of the former (I hadn’t seen the second when I filmed this, yesterday) and the entirety of the latter, but I hope I have given both a fair crack of the whip in difficult circumstances. Also, on a lighter note: bomb disposal in Afghanistan in new BBC3 comedy Bluestone 42. And, on an actually lighter note, local government in the where-have-you-been? US legend Parks & Recreation, finally arriving on BBC4 after four years on NBC and at least that long on the lips of international comedy aficionados with Region 1 players or no compunction about illegal filesharing. (I have a Region 2 player, a vastly reduced budget for DVDs in any case, and a total aversion to illegal downloading.)

On this week’s Telly Addict, a clash of the Kudos-produced titans: the eight-part Broadchurch on ITV and the five-part Mayday on BBC1. It’s an unfair fight, as previously established, as I’m reviewing one episode of the former (I hadn’t seen the second when I filmed this, yesterday) and the entirety of the latter, but I hope I have given both a fair crack of the whip in difficult circumstances. Also, on a lighter note: bomb disposal in Afghanistan in new BBC3 comedy Bluestone 42. And, on an actually lighter note, local government in the where-have-you-been? US legend Parks & Recreation, finally arriving on BBC4 after four years on NBC and at least that long on the lips of international comedy aficionados with Region 1 players or no compunction about illegal filesharing. (I have a Region 2 player, a vastly reduced budget for DVDs in any case, and a total aversion to illegal downloading.)

And if you missed my chin-stroking essay on Broadchurch, Mayday and the new film Broken, you may read it here. (There was a time when I was paid for writing such essays, but now I do them for free, which makes them purer, in some ways.)

March 11, 2013

There’s been a murder

This time last Monday, ITV premiered a major new drama, Broadchurch, the first of an eight-part whodunit set in a small, close-knit English community revolving around the death of a child. What I’m supposed to say now is that, on the same night, at the same time, in the same slot, ITV’s arch ratings rival BBC1 broadcast what was the second episode of a five-part whodunit set in a small, close-knit English community, Mayday (shot I believe in Dorking, but never specified as Surrey). Actually, it’s impossible not to the say all of that, because it is factually correct. If I add that both major new dramas were produced by Kudos, the production powerhouse whose reputation was built on Spooks, Hustle and Life On Mars (and with whom I have worked in my capacity as Q&A host and, once, as TV presenter), again you won’t need to hold the front page. These facts are now self-evident, and old news.

However, I’ve worked up some kind of unifying overview now. I watched Mayday through to its bitter end – it ran over five consecutive nights, which is always a risky strategy, as to exploit boxset-binge orthodoxy you’d better have the goods to back it up – and saw the new, award-winning British film Broken over the weekend, which isn’t about a child murder, but hinges on our grim fascination with children in peril.

Now, the murder mystery dates back to the 19th century in literary terms, with a boom in the whodunit in the first half of the 20th, and has been a fallback option in film since the silents. There is nothing new in a TV serial being predicated on a crime being solved. Indeed, take away the crime and police drama from contemporary and you’re left with a pretty patchy looking set of listings for the terrestrial channels, and a blank screen with a white dot in the middle on Alibi and ITV3.

The publicity for Broadchurch has been very effective, from hoarding to cinema advertising (a brave excursion into the dark for any TV show), making the most of its largely original setting, Dorset’s magnificent Jurassic Coast – which I know well from visits to Billy Bragg’s house and walks along the fossil-filled beach with his old dog, Buster. The limestone cliffs make a thrilling backdrop for David Tenant, Olivia Colman and the rest of the fine cast, plus some police tape. (We are also initially led to believe that the victim, 11-year-old Danny, fell to his death from the cliff.) Chris Chibnall, the writer, who was instrumental in Law & Order UK and wrote the superb single drama United, has lived in Bridport for ten years, which has acted as a template for Broadchurch itself (although filmed in Avon, not Dorset).

With Danny, and the pivotal disappearance of 14-year-old “May Queen” Hattie in Mayday, this was TV drama risking that all-too-common hazard: the news overtaking fiction. Had a boy or girl gone missing in similar circumstances, or been found murdered, it’s feasible that both “major dramas” would have been pulled from the primetime schedules for reasons of sensitivity, or over-sensitivity, arguably. (Ghoulishly, a 16-year-old girl, Christina Edkins, was stabbed on a bus in Birmingham, but this happened on the Thursday morning, and was clearly adjudged to be different enough from the more ethereal events in Mayday, where pagan ritual was certainly implied in the build-up to the reveal of the murderer.)

I guess that “every parent’s worst nightmare” is frequently used as a hook for popular drama because of the fact that children are all too often victims of violence or abuse or abduction. It seems to me – and I’m not an expert – that the “classic” literary whodunits generally involve the murder of an adult, and not a child. But there’s nothing more dramatic than an “innocent” in danger. Why else would the disappearance of Madeleine McCann capture the world’s imagination so? Why else would we all have heard of a place called Soham? Or named a law after Sarah? We live in a world where the spectre of school shootings in America are matched here only by an all-engulfing paranoia about marauding paedophiles, grounded or otherwise.

Broken, directed by Rufus Norris and written by Mark O’Rowe (Boy A, Perrier’s Bounty), hints at this, as a grown man with unspecified mental problems is – in the opening scene, and in the trailer, to be fair – attacked by a next-door neighbour while cleaning his car in the suburban London cul-de-sac the main characters share. This, to borrow a phrase from screenwriting manuals, is “the inciting incident” and it happens almost before anything else has been established, other than a young girl lives on the same street at the childlike man.

I won’t divulge any specifics, as Broken has only just been released, and it’s better if you don’t have too much foreknowledge. But the protagonist is a 14-year-old girl, Skunk, one seemingly much less “adult” than Hattie the May Queen in Mayday (who is played by a 20-year-old actress, and at no stage convinces as a 14-year-old – she plays her surviving twin sister, too). Skunk is played by the actually-14-year-old Eloise Laurence, a real find, and she conveys as much as anything else a sense of sensitive resilience, which is handy, as the street she lives on seethes with resentment and violence. Where Mayday revolves around a creepy forest (the screenwriting manual, or meta-manual, I am currently reading is called Into The Woods, after the Joseph Campbell mythic concept of the dramatic “journey”), where all manner of unsavoury events either occur, or are rumoured to occur – voyeurism, dogging, assault, murder – Skunk’s refuge is a vacant hulk of a caravan in the back of a breaker’s yard. No picturesque woodland or limestone cliffs for her, although this publicity shot suggests otherwise.

Because Mayday has finished, I will mention some of the specifics of its plot, so if you haven’t seen it, please look away now. Hattie disappears, and her body is not found until over halfway through – there’s a red-herring item of clothing in a lake, but that’s all it is – so the absence of a body absolves the writers of having to deal with the usual, formulaic procedural detail, and one assumes this was a deliberate de-cluttering of the form. It’s clever, as the mystery of abduction is in many ways more potent than the mystery of who murdered her. There’s also a red-herring “sighting” of her, alive, on the news, which again is a simple sleight of hand, and a bit of a swiz. There are plenty of false leads and loose threads in Mayday, which is a shame, as five nights of your life is a big commitment, as I’ve stated. Also, without a detective – except for Sophie Okonedo’s retired policewoman, who doesn’t really count – there’s no plodding investigator to tie up the leads.

Broadchurch, of which we’ve only seen one episode, looks far more conventional, and Chris Chibnall told me it was “aggressively plotted” to every ad-break, and it already shows. I’m guessing Mayday was commissioned as a five-night feast, as one-a-week series don’t usually get commissioned in fives, and it’s an unforgiving brief, as there’s no time for audiences to forget anything, hence higher expectation about continuity and pay-off. It had some really nice writing in it, not least the opening scene in which Lesley Manville’s developer’s wife found out that her husband, Peter Firth, wasn’t in fact walking their fat dog for two hours each night after the dog had been subjected to tests at the vet’s. What an original and clever way of her suspicions that he was “up to something” to be aroused.

Because we know that Danny in Broadchurch was out at night, on his skateboard, when he should have been tucked up in bed – or, at least, the police currently think he was – we don’t yet know what to think about his death. Forensics already shows that he didn’t fall at the point where he looked to have fallen from. So murder is suspected. (Unlike Madeleine, he wasn’t abducted from his bedroom window; we always think of Madeleine now.) In the unnamed village in Mayday, no reporters descend, and the police take a seemingly peripheral role, while the villagers search the woods and threaten lynch-mob justice. In Broadchurch, it’s already all about the media, local and national, and their muddying of the waters of truth.

We fear our children going into the woods, or out onto the cliffs, or, in the case or Broken, into derelict caravans in breaker’s yards. We are told we must always know where they are, but we don’t. Do we mollycoddle our kids and wrap them in cotton wool, and thus leave them unprepared for the big, bad world they will inevitably have to enter? (The symbolic “woods” we must all at some point have to enter, like Campbell’s mythic protagonist.) There are three sisters in Broken who are worldy and streetwise, and yet disruptive and abusive, and old before their time. They bully and they swear and they shout across the cul-de-sac. And yet, through the cleverness of the plot (which, by the way, is utterly depressing in its depiction of ordinary folk), we feel sympathy for them, and their violent dad (Rory Kinnear), as they have lost their mum.

The scene in episode one of Broadchurch where Andrew Buchan, the father, is called upon to identify the body of his son, Danny, is harrowing, and beautifully acted, and will haunt any parent watching. (“He’s only little,” he observes.) I’m not even a parent and I can see the hurt, so acutely is it written and played. We who are not parents are children, so it’s universal stuff.

Sometimes, I wonder if British drama, whether urban, suburban or rural, isn’t just a little bit depressing? Death is so often the driver of the narrative. Violence so often the inciting incident. If a TV series reliant on corpses turning up on a weekly basis, whether it’s the pitch-black Silent Witness, or the more bucolic Lewis, they only use a dead child as a real trump card. It’s obvious why. A dead adult is a tragedy, but at least they’ve lived some of their life. A child? So much life left to live. (How shocking was the beginning of Utopia when an innocent child in a comics shop was gassed to death by hitmen? A trump card played so early! It also had a school shooting that was one of the most shocking scenes I’ve seen on television for years – and stunning for all of that.)

The epic tragedy of Broadchurch. The concentrated, mystically informed tease of Mayday. The painfully raw reality of Broken. A small town, a close-knit community, a cul-de-sac, all “wrapped up in secrets” and bound in police tape. Don’t go into the woods. Don’t go into an alley. Don’t go near that cliff. Don’t go into that comics shop.

Don’t have nightmares.

March 7, 2013

Writer’s blog: Week 10

More solipsism, good idea. It’s Thursday and I took this picture last night, in the dressing room at the Roundhouse in Camden, North London. I was hosting the first of three previews and Q&As for the Guardian Edinburgh International Television Festival (formerly the Media Guardian Edinburgh International Television Festival). You may recall I did some intensive hosting at the Festival last August, and had a rare old, star-spangled time. I’m hoping to do the same again this year, hence my access to this glamorous dressing room last night. It wasn’t my dressing room, I was sharing it with at least four other people, possibly five, as it was also our green room.

Our first preview and Q&A was for The Incredible Mr Goodwin, a brand new vehicle for the swashbuckling talents of daredevil escape artist Jonathan Goodwin, whose amazing feats you may have seen on the likes of Dirty Tricks, or Death Wish Live, or The Indestructibles, or One Way Out, being buried alive, sticking needles through his hand, hanging from great heights, that sort of caper. This is the show that will, hopefully, put him up there with Derren Brown, Dynamo, and other hip performers who do astounding feats – although call Goodwin’s stunts “tricks” and you might feel the weight of his inflated upper arms!

There’s a teaser here, if you dig that sort of thing. It’s like an urbane, well-read Jackass with a wife and kids.

It’s on Watch, which is part of the UKTV “family” of channels, alongside Dave. It’s interesting that it’s on a boutique channel, but that’s a sign of the times. Watch, or UKTV, gave Goodwin and his producers at Objective the budget and freedom they needed to make what is a pretty glamorous, transatlantic “fuck-off moment” compendium (Goodwin’s description), and they’ve been marketing the hell out of it. (He hung from a burning rope off the London Eye on Tuesday, which proved an effective teaser stunt.) I hope the show draws a record audience to Watch, as they’ve taken quite a big punt on this, and as anyone who makes television will tell you, it’s no longer the case that the big terrestrial broadcasters hold all the money.

Anyway, I enjoyed meeting Jonathan – as affable and candid in real life as he seems onscreen (think: the medical opposite of David Blaine, who happens to among those whom Goodwin has advised in the past) – and his producer Matt, and the half-hour Q&A was easygoing and informative. We had some smart questions from the audience, too, which was made up of industry onlookers and paying punters, my favourite being: “Have you ever been psychoanalysed?” (He hasn’t.) Goodwin’s wife and baby appear in the show, to point up the humanity of a man who is prepared to be buried alive or to climb a skyscraper using only gloves and grippy trainers.

The bonus came at the end of our session, when the screen rolled up and Goodwin revealed a large bed of nails, which – surprise! – he didn’t lay down on. He plucked a woman from the audience and cajoled her into laying down on the nails, which turned out to be less painful than you might imagine, apparently. This is because the weight of the body is evenly distributed over the nails. Then came the reveal: his producers lifted the bed of nails, and left a lower bed bearing just the one six-inch nail. At which Goodwin stripped his t-shirt off and laid down on it. For the count of ten.

Whether or not the stunt is 100% honest and “real” or not, it bloody looked real from where I was sitting. And that’s the appeal. In the first show, he pushes a needle through his cheek and pulls it out of his mouth using pliers. He climbs beneath an SUV as it barrels down a runway. He monkeys up a building, past the window cleaner. He puts his hand in a bear trap. It’s entertaining stuff, and it was fun to sit next to Goodwin himself and watch the show on the big screen. He relished watching the reactions of the Roundhouse audience when, onscreen, he pushed the needle up his nose and out of his throat. These stunts require an audience, sometimes a close-up audience of a handful of “witnesses”, to make sense. I must admit, it’s not my usual cup of tea, but Goodwin won me over, with his affability and his apparent minimum of ego.

This made it a fairly unusual Wednesday. I’d spent the early part of it waiting in for a tradesman whose office called to say he wasn’t going to make it. As I think of myself as a tradesman, I was a bit pissed off, but they re-booked him for 8.30 this morning, and he was there, bright and early, and did the job brilliantly, so I’m not complaining. The work I do for people does not require them to “wait in” for me, as I am likely to be sending it by email at a designated time, not knocking on their front door. (Interestingly, on Tuesday afternoon, I was trying to arrange a way of taking efficient delivery of the DVDs I need for the next GEITF Q&A – ITV sitcom The Job Lot, for which I will be talking not just to the writers, but to stars Russell Tovey and Sarah Hadland! – and after a few emails, I decided to just walk to the production company’s office and pick it up myself. That’s the kind of hands-on guy I sometimes have to be. So much fannying around otherwise.)

I seem to be doing a lot of hosting these days. I am a host, just like Hannah’s friend on Girls is a hostess. This is not such a terrible rung to have reached in my 25th year in showbiz. As I always say to the people who employ me in this capacity, I have yet to grow blasé about meeting and talking to people who make telly programmes. Whether it’s a writer, or a producer, or an actor, or an escapologist, they are interesting to me per se. I met a lovely guy called Rich last night. He works for UKTV. When I first knew him, in 1997, he was a runner at the production company which made Collins & Maconie’s Movie Club for ITV. This is how TV works, or can do. Jonathan Goodwin used to be a stunt adviser; he trained to be an actor; now he’s got his own show as a bald nutcase with his name in the title. (Yeah, been there, done that, in 1997 – always be nice to people on the way up, as you’re bound to meet them again on the way down.)

I’m pretty sure they’re nearly sold out, but if you’re a Russell Tovey fan, or Olivia Colman fan (who isn’t?), the other surprisingly intimate GEITF screenings are bookable here. Thanks to Liz for setting it all up, and to that large bunch of young people I fell into enthusiastic nerdy conversation with at the Roundhouse bar afterwards about Breaking Bad, Black Mirror and Game Of Thrones. I didn’t catch everybody’s name. (One gentleman among them lamented the fact that I am no longer on the radio with Josie Long. There is, almost literally, always one, wherever I go.)

These are the cats on today’s calendar. I like them. And thereby hang two tails.

March 5, 2013

Bits of him are falling apart

I am of an age now, 48, where making a fuss about birthdays is for milestones only, and my next milestone occurs in two years’ time. (I’ll be making a right old fuss about that!) Until then, it’s just an annual day off in early March, as it was yesterday. I did no work. I had my phone off for most of the day. I went to the Roy Lichtenstein retrospective at the Tate Modern, and ate a long lunch in a favourite restaurant in the West End of London, then came home to doze off in front of Mayday. It was a most excellent day. But aging is a poisoned chalice.

I’ve not marked my birthdays much in this blog, largely because I’ve been in my forties ever since starting it, so there’s been little to string bunting up about. The long, hard trudge through your forties is, I have found, one fraught with dichotomies. I’m fundamentally enjoying being in my forties, but, as much as the mid-thirties are as packed with surprises as a suicide bomb-vest, your mid-forties also reveal darker secrets about the passage of time. In your forties, by the very nature of maths, you know more than you’ve ever known in your life, but you also start to forget things. Names, mostly, but it’s alarming to discover what Homer Simpson spotted: every time you learn something new, your brain squeezes out something old.

You also get tired earlier in the evening, so find yourself going to bed earlier, and thus your days get shorter. I’m a morning person, so I have no trouble leaping out of bed as early as 5.45am, and can be working 15 minutes later, but still, I’m not sure I’ve ever loved the feel of my pillow against the side of my face as much as I do now. When it’s just been washed: even more blissful. This is a positive development in sensory terms: I find myself more grateful about small sensations. You’ve heard older people sigh as they sit down. It’s gratitude for the sensation of not being on your feet. It’s a good sound. It’s rooted in the ageing of the bones, but it’s still a good sound. When you’re young, you appreciate nothing, and are constantly in search of kicks. You’ll be amazed how much more easily pleased you’ll be in your forties – and beyond, I’m assuming.

Since discovering a cut-price, no-frills gym last September I’ve been back on the machines, and I realise that doing 20 minutes on a treadmill at 6.40am, as is my preference (I’ve never fancied exercising after work) is almost entirely symbolic of the way that, in your forties, in terms of health, you must literally run to stand still. I’m quite addicted to cardio and resistance work again, as I was in my late thirties, when I first discovered that drinking lager, eating wheat and doing nothing makes you flabby and lethargic, and in my early forties, when I could afford to be in a posh gym. However, as pleased as I am to be exercising regularly, I’m more aware than ever that my body is at a point in its life where it breaks more easily. I put my knee out on the treadmill a few weeks back, and by the end of that day, it was literally painful to walk downstairs. (It clicked back overnight and I was normal again the next morning, but I read it as a warning sign: you’re not as young as you were.)

I read William Leith’s gripping and candid account of midlife decline, Bits Of Me Are Falling Apart, in 2009 when it was first published amid the expected deluge of broadsheet coverage. I have no idea whether it sold or fizzled, but I would recommend it as required reading for anyone, especially men, in their forties. In it – solipsistically but what other way is there? – he catalogues everything that’s going wrong with his body, and many things that aren’t, but which he suspects are on the verge of grinding to a halt or falling off. It’s grimly funny, but rings all too true. (He’d previously written about overeating in The Hungry Years, and seems to have treated his body badly, but even if you haven’t, you’ll see yourself in his paranoia.) In 2009, just four years ago, I felt almost smug, as I had my eating under control, had reduced my drinking to treats only and had perfect eyesight. Today, the first two remain true. I had my first ever eye test last week because an opticians was offering one for a fiver, and the prognosis was, if not grave, certainly worrying.

But hey, every adult I know wears glasses – I mean literally. I’ve got away with it for 48 years, and I look at a computer screen all day, five days a week. Those of us who do “close work” are all basically Donald Pleasance’s forger in The Great Escape waiting to happen. And there are plenty of things you can have wrong with you that I certainly appear not to have wrong with me yet. I’m an optimist by pathology, as you know, so I’m not one for worrying about things that might happen – unlike Leith, who seems predisposed to worry himself into an early grave – but it’s as well to be aware of your own mortality, I guess, and to look after yourself. I find myself holding the handrail when walking down steps at stations all of a sudden. There can be no harm in guarding against accidents.

The only birthdays I have recorded on this blog have been my 41st birthday in 2006, on which, for fun, I listed my birthday presents in homage to what I used to do in my childhood diaries:

A Seinfeld book

A book voucher

A Sideways DVD

A really nice black jumper

Two tickets to see Arctic Monkeys in April in Bournemouth

Two tickets to go and see Malcolm Gladwell live on the South Bank

I must admit, that seems like an indulgent haul, but it was 2006, before the financial crash, when money seemed to be for spending. (A faintly ludicrous, bourgeois concept now.) Another big difference that year: I went to work, on my birthday, even though it was a Saturday, because I used to present the Chart Show on 6 Music. (I find it almost inconceivable to think that I had my own weekly show on 6 Music just a few years ago. I used to have to commute in from outside the M25 in those days, too. What a slog that was.)

I also recorded my 43rd birthday in 2008. It says I had a quiet day, “and then watched both parts of ITV’s newest grisly detective drama, the wishy-washily-named Instinct, starring the bloke who played the policeman on Shameless, Anthony Flanagan. It was one of those with a serial killer who spent an awful lot of time and effort trying to put everyone off his scent. You get a lot of those in ITV dramas. Not so much in real life. Guess what? It was entertaining, but not as profound as it appeared. I’d quite like to write one of those, one day. Plenty of time.”

ITV are still making entertaining crime dramas. I’d still quite like to write one. It’s good to look forward and not back on the day after your birthday, even when bits of you are threatening to fall apart. Plenty of time.

Scenes of a sexist nature

Sorry for the paucity of blogs of late. As usual, it means I have been working. I’m still working. I recorded this week’s Telly Addict on Friday, as I had a backlog of TV shows to cover and I wanted to keep yesterday clear of work as it was my birthday. (So, yesterday, I wasn’t working.) And here it is, with belated coverage of Spartacus: War of The Damned on Sky1 (yes, I know I erroneously credit it to Sky Atlantic in the review – forgive me); a mid-season match report of The Walking Dead on Fox; the worst of The Oscars 2013 on Sky Living; Sue Perkins’ new BBC2 sitcom Heading Out; and ghost story Lightfields on ITV. I’m already lining up Broadchurch and Mayday for next week. It’s all go.

Sorry for the paucity of blogs of late. As usual, it means I have been working. I’m still working. I recorded this week’s Telly Addict on Friday, as I had a backlog of TV shows to cover and I wanted to keep yesterday clear of work as it was my birthday. (So, yesterday, I wasn’t working.) And here it is, with belated coverage of Spartacus: War of The Damned on Sky1 (yes, I know I erroneously credit it to Sky Atlantic in the review – forgive me); a mid-season match report of The Walking Dead on Fox; the worst of The Oscars 2013 on Sky Living; Sue Perkins’ new BBC2 sitcom Heading Out; and ghost story Lightfields on ITV. I’m already lining up Broadchurch and Mayday for next week. It’s all go.

Andrew Collins's Blog

- Andrew Collins's profile

- 8 followers