Andrew Collins's Blog, page 23

April 15, 2013

The needles and the damage done

I hope you are able to see The Place Beyond The Pines without finding out too much in advance about how the story plays out. I innocently read the review by the seasoned and should-know-better David Denby in the New Yorker and found out exactly what happens in it. (I’ve read long-form reviews in UK publications, such as Philip French’s in the Observer, where the writer has expertly skirted around one key issue, so it can be done with discretion.) To be honest, it’s still a fine film, in my opinion. But the less you know the better.

It’s a melodrama, and that’s not anything like a criticism. I would argue that the definitive films noirs are melodramas, and this third feature from writer-director Derek Cianfrance (I never saw his first, but my review of Blue Valentine is here) certainly fits into that approximate genre. It’s also a grand family saga. It has the feel of an old-fashioned American miniseries, something like Rich Man, Poor Man, which older readers may remember fondly.

Because it’s showing at the Curzon, which is a small arthouse chain of which I am an enthusiastic member, I have to put up with the same fairly narrow range of trailers on a loop each time I visit. The Place Beyond The Pines has a striking trailer, in which Ryan Gosling is revealed as a stunt motorcycle rider (as opposed to the stunt car driver in Drive) and the father of Eve Mendes’ baby son, which he wishes to support. The trailer also reveals that robbing a bank is what he does to raise some funds, and that Bradley Cooper’s cop in some way confounds this plan. I commented to my friend Lucy that it gives too much away, but, having seen it, she assured me that it doesn’t.

So … the bare bones of the film – sexy images, by and large, of the main protagonists – are all that we who have seen the trailer actually know about The Place Beyond The Pines. Unless we have read David Denby. I tell you this so that, if you intend to see it, you avoid reading any more reviews (although you’re safe to read on here). The trailer gives away only half the picture. It’s a very clever trailer.

And it’s a very ambitious film. Indie by nature, it ticks the credibility boxes by casting Gosling in the lead, but casting him opposite Bradley Cooper, who is a much more mainstream star, with cred of his own after Silver Linings Playbook. (Gosling started out as a cool actor in challenging stuff like The Believer and Half Nelson, but his commercial appeal grew, whereas Cooper hit big with broad-appeal movies like The A-Team and The Hangover and has been working hard to improve his licks, which is bearing fruit.) It’s a film about men, and these two are the men it’s mainly about, but not exclusively.

With its diners, carnivals, trailers, auto shops, car lots and 1st National banks, it’s almost a caricature of smalltown America as seen in the movies – as such it takes on mythic properties, and is lovingly shot by cinematographer Sean Bobbitt, whose beautiful work you’ve already seen in Hunger and Shame. Set and shot in and around the former Mohawk settlement Schenectady, it has a realism of place that’s hard to replicate, and despite the melodrama unfolding within it, it lends authenticity to the performances, which might otherwise tip into camp. (Many have likened Gosling’s brooding brute in a white t-shirt to Marlon Brando in his ape-like prime, and you can see where they’re heading.)

I think I bought into the film more than other critics, who’ve variously questioned the length (it’s two hours and 20 minutes, which is long for an indie), the third act (of which too much must not be spoken for fear of neutering its revelations), the paucity of anything much to do for the decent female actors (Rose Byrne is underused, too) and Cianfrance’s lack of control with the material as it expands outwards. I forgive it these sins. It’s bold, high-minded American cinema that isn’t afraid of having a character stop at a crossroads on his motorbike and fail to respond to a green light at the point when he is at a crossroads in his life. Neither is it afraid of visual rhymes – again, which should be savoured without me listing them here – or big themes like fatherhood and honour and, just maybe, the poisoning of the American dream.

Oh, and the music is superb. The score is by Mike Patton, formerly of Faith No More, and its haunting theme, The Snow Angel, pressed into effective service for the trailer, is a pre-existing tune written for a previous film, but no less fitting for it. There are also numbers by Bruce Springsteen, Suicide and Hall & Oates, and some passages by Arvo Part. It’s all put together with maximum care and attention. (And Hall & Oates’ Maneater has a hook in an earlier line of dialogue, it’s not just a hit song for its own sake.)

This and Compliance are my favourite American films of the post-Oscars year so far.

April 12, 2013

Leak ending

It wasn’t exactly the Battle of the Blackwater, but there was a brief exchange of fire below the line under this week’s Telly Addict, which was dominated, predictably, by my review of the opening of Season 3 of Game Of Thrones. Although I was careful not to give away any important plot details from Episode 1 in my review – nor to let anything slip in the clips I chose – I strayed, indirectly, into the minefield anyway. This was the pretty angry comment posted by a man called Richard Berry:

Why did the Guardian ensure this video gave a blatant spoiler, even for those who haven’t watched it?

The still image used to advertise the video on the Guardian HOME PAGE shows a character who is clearly alive in season three. The entire plot of series two is that a whole range of others are trying to kill him. Thanks for ruining it.

We don’t all have Sky, and I thought the Guardian would try to refrain from forcing their viewers into the embrace of Rupert Murdoch.

Note that he does not blame me, which is why stepping in may have been a mistake on my part, but it seemed unlikely, what with around 120 comments left under the review at that stage, that anybody involved in producing Telly Addict or responsible for choosing the still that accompanies each one on the page would be following the discussion as vigilantly as I do, so I responded. In my haste, I parried that the offending still was actually from the end of Season 2, which I believed it was. (It certainly features two characters who appear in Seasons 2 and 3, but I have been re-watching episodes from the first two seasons of late so I can’t be trusted!)

Anyway, it turned out to have been from Season 3 after all – from Episode One, in fact. Either way, Richard Berry felt that in revealing that two characters from Season 2 were even in Season 3 was, in and of itself, a spoiler. One of the characters is a principal. It is not out of the question that he might have been killed at the end of Season 2, as a principal was killed at the end of Season 1. However, Sky have been advertising Season 3 with huge billboards in the UK, and these feature the faces of the principal characters, one of whom is in the still the Guardian used. (Is all this obfuscation really necessary? I don’t know.)

Having myself recently re-watched the climax of Season 2 (which revolves around the Battle of the Blackwater), I know that the story does not hinge upon … actually, I now feel too paranoid about spoilers to even discuss it in vague non-detail. After all, not all GoT fans are Sky subscribers, HBO customers or illegal downloaders; although many will have read the books and will know exactly what happens throughout Season 3, and, I think, 4, maybe even 5. (I haven’t looked.)

I have some sympathy with Richard Berry, as he’s working his way through the box sets, as I have done with a number of US imports, notably Battlestar and Breaking Bad, in both cases behind the actual broadcasts and susceptible to spoilers. I’m currently watching the stirring and addictive Friday Night Lights, on Sky Atlantic, which started showing all five seasons after the fifth had aired and when the whole saga was in the public domain. I made the innocent mistake of looking up one of the lower-ranking actors during Season 1 and found out that he was in all five seasons, so I know he’s in for the duration – a spoiler of sorts, although nobody’s fault but my own, right?

But a vanilla still of two characters, officially released by HBO and Sky, surely cannot be categorised as a “spoiler”. Richard will have to wait until Season 3 is out on box set – at the end of this year no doubt – before he can see it. In the meantime, I expect he’s diligently avoiding any internet sites related to GoT, including Wikipedia. He saw a photo on a newspaper’s website below a caption saying something like “The Week in TV”, assumed it to be from a future episode, and felt that it “spoiled” Season 2. Without going into any plot detail, it was impossible for me to explain to him why it wasn’t a spoiler, because you’re on thin ice the whole time when you’re ahead of someone.

The spoiler is well-named. “A person or thing that causes spoilage or corruption,” according to the dictionary, or else “a plunderer or robber”. Before the internet proliferated, its most contemporary setting might have been in print publishing, where newspapers still habitually print spoilers to undermine a competitor’s scoop, and entire magazines are launched to interfere with a rival’s plans. (OK! is just about the most successful spoiler title in publishing.)

I wrote about spoilers for the Observer in 1999, but the focus then was movies. I noted that the concept of spoilers was “an underground one”, which seems quaint now. “Nuggets of information made public with the sole intention of undermining the authority of a forthcoming cinema release” were, I wrote, “all the rage, thanks to the Internet, where knowledge truly is power. If you want to know what happens at the end of The Blair Witch Project, just key the title and the word ‘spoiler’ into your search engine, and you’ll soon find the goods.”

I had been commissioned to write the piece because of the forthcoming Sixth Sense, whose twist had the new-fangled Internet aflame. Its twist had, in fact, become a commercial issue, as patrons in America had already started buying a second ticket to re-view the film. “That’s a very important element,” said Dick Cook, chairman of Walt Disney, in between counting his takings. “People are going back to catch all those things you don’t pick up the first time.” The spoiling of twists is, of course, a one-time-only offer.

I did a roll-call of those 90s thrillers with a twist – The Usual Suspects, The Game, Scream, Primal Fear, Wild Things, Twelve Monkeys, Basic Instinct, Jagged Edge - and it did seem like an epidemic. I also observed that many actually fall to bits once you revisit them armed with the special knowledge gleaned at the end.

An article about The Sixth Sense in 1999 in American magazine Entertainment Weekly was stamped with a warning to readers: STORY CONTAINS KEY PLOT POINTS. This was an early example, I believe, of what we now know as the SPOILER ALERT. As a longtime subscriber to Sight & Sound, whose trademark synopses of new releases inevitably give away endings, I have grown used to the warning. I may as well also confess to being the type of person who reads on when advised not to.

I read the Entertainment Weekly piece right through, not having seen the film, and I went in to see The Sixth Sense knowing the wham-bang ending. I wrote, “As a result, barring amnesia brought on by a blow to the head, I will never be able to see The Sixth Sense the way it was intended.” This has remained true ever since. I am simply a sucker for reading synopses and long reviews, where twists are most likely to be revealed. The warning SPOILER ALERT is a welcome mat to me. (The recently deceased Roger Ebert, perhaps America’s most famous film critic after Pauline Kael, admitted to having been “blind-sided” by The Sixth Sense in the Chicago Sun-Times. Lucky him.)

When Neil Jordan’s The Crying Game came out in 1992, journalists and those attending preview screenings were asked not to give away the big twist. (If you’re still unaware of this one, it occurs long before the end and has an important bearing on the central relationship. It’s also one of the most beautifully-handled and powerful gasp-moments in modern cinema, the sort you envy someone not knowing.) Because The Crying Game had so many other merits as a moviegoing experience, most kept their mouths shut. Ebert, again, ended his review with the words, “See this film. Then shut up about it.”

Being asked to shut up about a hot new film sends out mixed messages: we, the paying public, are usually urged, “Tell your friends!” Because no matter how sophisticated and well-oiled the Hollywood publicity machine has become, word-of-mouth, and its successor word-of-Tweet, is the one marketing factor that’s truly out of The Man’s control. (Only this week, the new Tom Cruise sci-fi thriller Oblivion was screened to journalists the night before it went out on general release, but that was, I suspect, for a different reason of media control.)

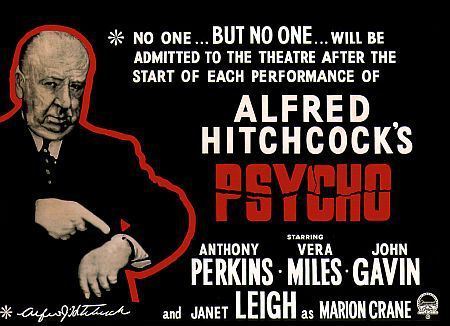

In 1960, Psycho was publicised with the memorably jolly tagline, “Don’t give away the ending – it’s the only one we have!” Hitchcock actually issued theatre-owners with a handbook, The Care And Handling of Psycho, with half-jokey notices for the foyer reading, “It is required that you see Psycho from the very beginning. The manager of this theatre has been instructed at the risk of his life not to admit any persons after the picture starts.” House lights had to remain down for 30 seconds after the end credits, to allow “the suspense of Psycho to be indelibly engraved in the minds of the audience.” Try maintaining that level of compliance in the iPhone age. (Although Steven Moffat and the Doctor Who team were able to pre-screen the first episode of last autumn’s new series to die-hard fans before transmission and successfully implored them not to electronically blab about the unscheduled appearance of the Doctor’s new assistant. Moffat effectively made it a trust issue.)

Back in August 1999, the Sun filled its front page with the headline, “OFFICIAL: BBC’S LOST THE PLOT”, claiming it had obtained “all the storylines of EastEnders for the next year”. However – and here’s the twist – the paper didn’t reveal a single detail. Readers were asked to vote by phone whether they wished to have their enjoyment scuppered or not. They did not. (I was writing for EastEnders at the time and felt very close to this passing scandal. When Phil Mitchell was shot, none of the writers knew who’d dunit. It was safer that way.)

All the Internet has done is made the sharing of information easier. For diehard fans of a franchise, whether it’s Doctor Who or Star Wars or Game Of Thrones or Twilight or Harry Potter, leaks and rumours and revelations feed their devotion. (I always felt luckier than everybody else in the cinema when I saw a Harry Potter, as I had no idea what was about to happen, not having read a word of the books; whereas the more devoted fans around me must have known every last detail.) Richard Berry and those like him who are one season behind on GoT and who have not devoured George R.R. Martin’s source novels, exist in a permanent time-delay: the story they are following is way ahead of them, and it’s out there, in the public domain, out of the bottle, airborne. They moan a lot in comments sections – a pretty risky place to dwell if you’re afraid of spoilers, in any case – but whose responsibility is it to protect them?

I fully intend to see the new Ryan Gosling film A Place Beyond The Pines at the cinema this weekend. David Denby revealed its surprise twist in his review in the New Yorker. I was initially as annoyed with Denby as Richard Berry was with the Guardian. And then I got over it. Not knowing something that happens isn’t the only enjoyment to be had. If something’s good, it won’t really matter.

It is not until the final frame of Citizen Kane that we learn who or what “Rosebud” is. As Kane’s effects are burned on a bonfire, the camera alights on the answer. Just as no-one heard him utter the word at the beginning, no-one notices the reveal at the end: the secret rests solely with us, the audience. Orson Welles, of course, thought it was a “hokey device”.

April 10, 2013

Tramp the dirt down

You may recall the Elvis Costello song from his 1989 album Spike. It began:

I saw a newspaper picture from the political campaign

A woman was kissing a child, who was obviously in pain

She spills with compassion, as that young child’s face in her hands she grips

Can you imagine all that greed and avarice coming down on that child’s lips?

In 1989, Margaret Thatcher had been in power for ten years. Still riding high and roughshod over the remnants of our society. Within the year, she would be driven, tearfully, down Downing Street and away to a well remunerated dotage ($250,000 a year for being a “geopolitical consultant” for tobacco giant Philip Morris, anyone?), only latterly diminished by senility and a series of strokes. For anyone who remembers the 1980s, she looms large. She was the leader who wrote the instruction booklet for what David Cameron and George Osbourne are trying to do now: that is, to squeeze public services and sell off as much silver as possible to the private sector until we have a shareholder-run state which answers only to the bottom line.

She is dead now. Death was explicitly wished upon her many times, and not just in protest song, and now those casualties on the road to serfdom have their wish. Her loss is lamented by those on the right who regard her as a figurehead, an achiever, an icon. Some on the left are organising street parties, which seems a bit harsh now that she’s actually died. I wonder if Elvis Costello is planning a trip to St Paul’s. Maybe he has mellowed since 1989. They do say you get more right wing as you get older. I find I get more left wing.

I would love to rewrite history and say that I despised her and her monetarist policies from the day she swept to power in 1979, but I was 14 at the time, and not politically educated. My politics, such as they might have been described, were simply handed down from my father, the sort of benign provincial Tory who put his working-class background firmly behind him, reads the Telegraph and believes in lower taxes, but who is anything but a foaming-at-the-mouth old colonel. I thought of him then, and think of him now, as a gentle, fair-minded soul. I did not feel indoctrinated by him. But I had to leave home and get to London before a more informed and passionate politics overtook me.

Educated by the NME – hard to credit that by looking at it now, but in the early-to mid-80s it was powerfully polemical and driven by Marxist doctrine, like much of the best music of the era – I read a book from the library by Jeremy Seabrook about the failure of the Labour movement called What Went Wrong? and it set me on the path I’m still on today. It was actually fashionable to be left wing in that decade, and I don’t mean to make voting Labour seem like a hollow lifestyle choice, it’s just that it meant something more profound and full-blooded than a party-political cross in a box. It was tied in with CND, and the GLC, and Red Wedge, and the NME, and Anti-Apartheid and, in Scotland, with the SNP.

The zeitgeist was embodied by the 1930s protest song Which Side Are You On?, powerfully covered by Glaswegian folk firebrand Dick Gaughan in 1985 for the miners’ strike. You were either with Thatcher, or against her. To be against her was, in my experience, to be alive.

I was a student between 1983 and 1987. As a constituency, we were hardwired to bristle at Tory policy. Listen to the contempt Thatcher has for students, as related in her second memoir, The Path To Power, (this comes from a chapter on her years in the Dept of Education, 1970-74): “This was the height of the period of ‘student revolution’ … it is extraordinary that so much notice should have been taken of the kindergarten Marxism and egocentric demands which characterised it … the young were regarded as a source of pure insight into the human condition. In response, many students accordingly expected their opinions to be treated with reverence.”

She idolised Macmillan-government ingenue and national curriculum cheerleader Keith Joseph – and later, of course, brought him into her cabinet, where his education policies were so punishing, my Dad wrote a letter to the local paper complaining about them – and, in The Path To Power, she defends Joseph against charges of being a “mad eugenicist” after an infamous speech in 1974 at Edgbaston where he said that “our human stock” was “threatened” by mothers “pregnant in adolescence in social classes 4 and 5.” As far as she was concerned, “the speech sent out powerful messages about the decline of the family, the subversion of moral values and the dangers of the permissive society.” That the permissive society was tied up with the liberation of women, and that the “decline” of the family was a coded Tory way of encouraging women back into the kitchen helps us to understand why Margaret Thatcher was no feminist.

In an article she wrote in the Telegraph in January 1975 when she was shadow Education Secretary but challenging Ted Heath for the leadership, she defended what she called “middle class values” as “the encouragement of variety and individual choice, the provision of fair incentives … for skill and hard work, the maintenance of effective barriers against the excessive power of the state and a belief in the wide distribution of individual private property.” She ranged these against “socialist mediocrity.” She won the leadership by appealing to the Tory party’s misty-eyed nostalgia for these values, which, when you break them down, are about looking after yourself: “individual choice … individual private property.” She was, if nothing else, consistent, right through her reign, which began here.

In reading her autobiography, which ends as she enters Downing Street, at which point the book turns into a sort of manifesto, I felt I understood a bit more about her character. She seemed interested only in politics and policy, from a very young age. There was little sense of a human being interested much in culture. (This probably explains why she cut arts spending.) She was, if nothing else, dedicated to her line of work, and to work in general, famously sleeping for four hours at night at her peak.

And she was confident that she was right. She treated the men around her in the cabinet as lower life forms, and forged on with what she felt she needed to do, and in the end, they turned on her, probably trying to claw back a bit of self-respect after years of emasculation around long tables. She believed in the individual over the state, in private over public, in self over society.

These tenets found purchase in a Britain previously beset by industrial unrest, which she attempted to wipe out by crushing the unions and literally removing the industries where they flourished. (If you read The Enemy Within by Seamus Milne, and it’s a set text as far as I’m concerned, you’ll see how Nicholas Ridley was charged with preparing for a showdown with the miners that would lead to the dismantling of the coal industry in order to give a boost to the British nuclear industry.)

All because she had read Hayek and Friedman and Walters, who warned against state intervention in economics (“central planning”), which Hayek claimed, in 1944, would lead to totalitarianism. He believed that the economy should be left “to the simple power of organic growth,” and it sounds so harmless in that phrase. But it’s the market we must bow to, and yet the market which has left this country in tatters – left, as it heinously was by New Labour, untrammeled on their watch – so that the current Tories can bulldoze their own ideological notions through the wreckage.

Well I hope I don’t die too soon, I pray the Lord my soul to save

Yes, I’ll be a good boy, I’m trying so hard to behave

Because there’s one thing I know, I’d like to live long enough to savour

That’s when they finally put you in the ground

I’ll stand on your grave and tramp the dirt down

It’s difficult on the face of it – even mean – to celebrate the death of an 87-year-old woman with dementia, who hasn’t wielded political power since 1990. Except that her policies, pushed through with the trademark defiance and zeal that her admirers credit as her greatest qualities, linger on. Where were you when you heard that Thatcher had died? The same place as me: in her long shadow. She did change this country. Or at least, she saw its dark soul and changed the way we thought about ourselves. She championed Reaganomics before Reagan. She unleashed the selfish bastard within, and sold council houses and privatised utility shares to an electorate apparently desperate to improve their lot at any price. The price we paid was the loss of community, the loss of compassion, the loss of perspective.

When England was the whore of the world, Margaret was her madam

And the future looked as bright and as clear as the black tarmacadam

The blanket media blitz has been predictable. (It doesn’t take a newspaper insider to surmise that her obituaries have been “on file” for quite a few years.) The not-quite-state funeral next Wednesday – and oh how appropriate that it’s a public-private finance initiative – will hopefully draw a line under all the nostalgia. Blair was as much of a statesman as she was a stateswoman, and there my admiration for both ends. She was more honest than Blair, and more forthright than Cameron. She fed the satire industry while taking apart all the other ones, and comedians will never have it so good again.

I’ve heard miners on the radio and TV unabashed in declaring their hatred for a dead woman. You can easily understand why. But I think I would find it difficult to concentrate at a street party – or do a dance on the dirt – when her legacy is all around us, not least in the anecdotal and statistical evidence of a nation convinced by a right-wing press and a few scare stories that the welfare state is a bad idea. Beggar thy neighbour? It’s what she would have wanted.

I never thought for a moment that human life could be so cheap

But when they finally put you in the ground

They’ll stand there laughing and tramp the dirt down

April 9, 2013

He GoT Game

Finally, a review of the start of Season Three of Game Of Thrones, although this week’s Telly Addict will, of course, start looking old and off the ball again by Wednesday, when Mad Men returns to Sky Atlantic for Season Five. You’ll have to wait until next Tuesday morning for a pithy summation of that. I do recognise that not everybody had Sky Atlantic, whether for fiscal or ideological reasons, and I do my best to sidestep spoilers in my reviews of these imported classics that may not arrive on DVD for a year (and the same with the clips I choose). But it’s a cold, hard truth that we must all learn to work with: some of the best telly in the world is on Murdochvision. Also this week, on telly-for-everybody, The Great British Sewing Bee on BBC1; The Village on BBC1; and The Intern on C4. Hooray.

Finally, a review of the start of Season Three of Game Of Thrones, although this week’s Telly Addict will, of course, start looking old and off the ball again by Wednesday, when Mad Men returns to Sky Atlantic for Season Five. You’ll have to wait until next Tuesday morning for a pithy summation of that. I do recognise that not everybody had Sky Atlantic, whether for fiscal or ideological reasons, and I do my best to sidestep spoilers in my reviews of these imported classics that may not arrive on DVD for a year (and the same with the clips I choose). But it’s a cold, hard truth that we must all learn to work with: some of the best telly in the world is on Murdochvision. Also this week, on telly-for-everybody, The Great British Sewing Bee on BBC1; The Village on BBC1; and The Intern on C4. Hooray.

April 2, 2013

It’s no Game

Since Game Of Thrones – or GoT as all the uncool kids are calling it – is the most talked-about TV show of the moment, with catch-up guides in every newspaper for those losers who haven’t been watching it from the start (we’re at Season Three for heaven’s sake – do you really have to wait for the broadsheets’ permission?), I have to confess that I’m not reviewing Game Of Thrones on this week’s Telly Addict, because, when I wrote and filmed it yesterday afternoon, the first episode hadn’t aired. (I review, not preview, as previously established.) But we do have the jolly return of Doctor Who on BBC1; Paul Hollywood’s Beard/Bread on BBC2; the latest sci-fi saga from the JJ Abrams universe, Revolution on Sky 1; an update on Broadchurch on ITV; a warm welcome for the regeneration of Foyle’s War on ITV; and a sneak preview of The Village on BBC1.

Since Game Of Thrones – or GoT as all the uncool kids are calling it – is the most talked-about TV show of the moment, with catch-up guides in every newspaper for those losers who haven’t been watching it from the start (we’re at Season Three for heaven’s sake – do you really have to wait for the broadsheets’ permission?), I have to confess that I’m not reviewing Game Of Thrones on this week’s Telly Addict, because, when I wrote and filmed it yesterday afternoon, the first episode hadn’t aired. (I review, not preview, as previously established.) But we do have the jolly return of Doctor Who on BBC1; Paul Hollywood’s Beard/Bread on BBC2; the latest sci-fi saga from the JJ Abrams universe, Revolution on Sky 1; an update on Broadchurch on ITV; a warm welcome for the regeneration of Foyle’s War on ITV; and a sneak preview of The Village on BBC1.

I have now, of course, watched the first episode of GoT, and it really is not for the latecomer. That’s all I’ll say. Full review next week.

April 1, 2013

Fool Britannia

I’m alright, Jack. Most of the tax and welfare cuts in what today’s Guardian calls “a new social order” do not directly affect me. Hooray! The “bedroom tax”, introduced today, robs 14% of housing benefit from those in social housing with one spare room, and 25% for two or more spare rooms. Not me. Nor am I among the two-thirds of those hit by the tax who are disabled. I am not affected by the lowering of the household income cut-off for eligibility for Legal Aid. I do not claim Council Tax benefit, so will not be affected by the system that administers it being transferred from the Government to the already financially strapped local councils.

Not being disabled, I am not affected by the disability living allowance being scrapped next Monday, and nor will it affect me that written applications for the benefit are replaced by face-to-face interviews. As I am not currently receiving benefits, or tax credits, I will not notice when, next Monday, they do not rise in line with inflation for the first time in history. Nor do I live in the London boroughs that, from 15 April, will cap welfare benefit. (The other boroughs will follow in July and September, by which time I do not expect to be a welfare claimant, but you never know in this economy, do you?)

The changes to the regulation of the financial industry do not affect me directly today. Nor does today’s unpopular handing over of NHS budgets to “local commissioning groups” made up of doctors, nurses and other practitioners affect me directly today.

So, it would be easy for me to be smug – my life goes on as normal. But I’m not smug. I’m f—ing furious, and deeply worried. These latest changes, particularly to benefits, and much more broadly to the NHS, are on the face of it designed by the nasty ideologues in the Conservative government (I think we should stop calling it a Coalition) to save money. Simple as that. The “under-occupancy penalty” (the Bedroom Tax), which some are optimistically and wishfully calling this government’s Poll Tax, will – we’re told – save £465m a year. Even if this is true – and I tend to disbelieve anything that comes out of George Osbourne’s mouth – that doesn’t count the cost. The cost to lives, to dignity, to pride, to social cohesion, and, if I may be airy-fairy for a moment, to the general mood of the nation.

Attacks on benefit claimants, the poor, the out of work, the disabled, the sick, are easy to tot up as net gains. But – and here’s where every single one of these cuts affects us all, even people who live in gated communities and have second homes in the country – I don’t personally want to live in a society where the worst-off are treated with corner-cutting contempt. This is the seventh richest nation in the world. In the world. And yet a report commissioned by the TUC predicted that by 2015, almost 7.1m of the nation’s 13m youngsters will be in “homes with incomes judged to be less than the minimum necessary for a decent standard of living”. This report by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation about poverty makes depressing reading, too.

The National Housing Federation – the independent body representing 1,200 English housing associations – calculates that the Bedroom Tax risks pushing up the £23bn annual housing benefit bill. Its chief executive said the tax would “harm the lives of hundreds of thousands of people.” (It will hit 660,000 households with each losing an estimated average of £14 a week. And if you think that £14 isn’t much, then you have no empathy, or have lived a charmed life. Hey, maybe you’re among the cherished 310,000 who will gain today because of the scrapping of the 50p tax rate.)

There are simple social equations here. Either you believe in society or you do not. Either you link the experience of the poor to the experience of everybody else, or you do not. If you do not live in one of the 3.7 million low-income households whose council tax benefit is cut as of today, then you do indeed seem to be alright, Jack. And if you can step back from the bigger picture – from “breadline Britain” as it’s been branded – and still not care, as it doesn’t affect you directly, then you are a better person than I am. I don’t want to live in a country where new food banks are being opened every week. Caroline Spelman, when she was Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, described food banks as an “excellent example” of active citizenship. I describe them as a crying shame.

The amazing Trussell Trust, the charity which runs the UK’s main food bank network, now have 325 running across Britain. They say that in 2011-12 food banks fed 128,687 people nationwide; n 2012-13 they anticipate that this number will rise to over 290,000. God bless them. But their good works should not be necessary. Charity should be a safety net, not part of our social infrastructure.

So, take a look around you, at your immediate circumstances, on this most unfunny of April Fools Days. If, like me, you are unaffected, directly, today, by the latest cuts, then slap yourself on the back, and hope that you are not affected by them, directly, tomorrow, or the next day.

Then walk out of your front door, and look down your street; look at the streets you walk past tomorrow on your way to work, if you have a job, and wonder about the people who live in the houses you pass. Are they affected, directly? Some of them will be. Even more of them will be affected indirectly. We are all affected indirectly, right now.

This government is run by people who do not think about or care about how other people are getting on. They truly believe, as if it were a religious creed, that if you fall by the wayside, it’s your own, lazy fault. If you’re not an “entrepreneur”, if you don’t do three jobs, if you haven’t saved, then you’re a shirker, or a sponger, or a waste of space. If you agree with this creed, sleep well. If you don’t, then you’re alright by me, Jack.

March 31, 2013

26 seconds of fame

I was, of course, flattered to be asked to contribute to BBC2’s Richard Briers: A Tribute. Having appeared on it, and seen it, I now I wish I hadn’t.

I was sad when he died, of emphysema, aged 79, last month, and although I’ve tended away from “talking head” work these past couple of years, I was caught unawares by the request and actually decided it would be nice to be able to pay tribute to one of my favourite sitcom actors. (At least it wasn’t a list show, and it was on BBC2 on Easter Saturday.)

I grew up with The Good Life, and still consider Ever Decreasing Circles to be one of the all-time best British sitcoms, and the producers of the tribute seemed keen to prime me to talk about some of Briers’ lesser-known work, which I was distantly au fait with, such as The Other One, the barely remembered sitcom he made after The Good Life with Michael Gambon in which he played a compulsive liar, and If You See God, Tell Him from 1993, darker still. As requested, I also did my homework about his films – Hamlet, Frankenstein – and refreshed my memory about Roobarb via YouTube.

On Tuesday 19 March, I duly turned up at the Gore Hotel in Kensington at 2.30 for filming, in a good black shirt and pinstriped jacket for the occasion, and was led to the basement bar, all leather armchairs, gilt, wood panels, stained-glass and oppressive furnishings, a not uncommon type of location for such jobs. Usual drill: bag down, mobile off, exchange greetings with the cameraman and soundman, ask for coffee, sit in the designated chair arranged at an angle from the camera line opposite the chair where the producer will sit and prompt with questions. I’ve done this a million times before.

Actually, not quite a million, but enough to have become a joke. In that first flush of clips shows, I never really minded being known for my “talking head” work. (It forms a chapter in my third book, That’s Me In The Corner, which begins with an audition I once had for some presenting work where the producer said to me, “I really like your talking head work”, a compliment I struggled to take seriously.) My old partner Stuart Maconie is the one who, along with Kate Thornton, became shorthand for “talking head”. The joke was: I did way more than he did, but he rose to prominence on I Love The 70s, which really relied on its “heads”, and because he was a natural at pithy reminiscence and witty soundbites, he made the edit more often than others.

I didn’t get the chance to pithily reminisce until I Love The 80s, and then only made the first three shows, after which I was not asked back. But I had my revenge by agreeing to every other “talking head” job thrown my way. They were fun, they were easy, they paid. And that’s it, really. If you check , under “Self – TV” (just scroll past the two erroneous entries for “Actor – TV”, which I’ve attempted to get removed to no avail), you’ll find 36 entries, most of which are “talking head” gigs. The first, according to the great oracle that is often wrong, was Solo Spice for C4 in 2001 – a colourful look at the Spice Girls’ solo work. I think my status as “former Q editor” qualified me. After this, and I Love The 80s, there was no stopping my head from talking.

The next few years – during which I was also an author, a 6 Music DJ, the writer of Grass and Not Going Out, and the host of Banter and The Day The Music Died on R2 and R4, all of which were way more important to me than my “talking head” work – were a blur of hotel bars and private clubs, talking at an angle to every TV producer and researcher in British television, and often meeting the same sound engineers and camera operators.

One job led to another. I turned a couple down – including one that appeared to be built around slagging off Noel Edmonds; I’ve always preferred to celebrate stuff – and there was one about the Muppets where I didn’t even make the edit once, which is an existentially challenging experience – but by and large, it was nice for my Mum and Dad to be able to see me on telly occasionally and I genuinely think it’s good to “keep your hand in”. If you talk as part of your job, it’s as well to practice.

I seem to have done around 40 list/clips/nostalgia/popular history shows over 13 years, but most of those before 2008, which seemed to act as kind of semi-retirement year. As I say, I’ve slowed down a lot. Maybe less clips shows are made. Maybe I don’t get asked. I surfed the wave for a while there. It’s fine. But the Briers show reminded me why I shouldn’t bother any more.

I sat in that armchair for the best part of an hour, talking constantly about every aspect of Richard Briers’ career. I knew the show was geared around the people who knew him and worked with him, as it bloody should do, and I guessed my job was to add a critical eye. (I never met him, or worked with him.) When we reached the end of his career, we wrapped, I got up, collected my bag, shook hands and left. The thought of playing even a peripheral part in the BBC’s official memorial to a great actor was reward enough, although I got paid as well. (This is still quite handy when you do as much work on spec, for free, as I do. I’m doing a lot of that currently.)

So, I watched the finished show over Easter weekend on BBC2 and found out precisely how peripheral I was! The programme makers had done brilliantly with their star witnesses: Penelope Keith, Felicity Kendal, Kenneth Branagh, Penelope Wilton, Peter Egan, Nicholas Hytner, Sam West, Prunella Scales, Sheila Hancock … as a viewer, I was thrilled. As the token critic who’d taken part, my heart sank. About half an hour in, it was clear that my contribution was not required. To be honest, I have no idea why they even left in my sole contribution, but there it was, at 38.02.

During the section about Briers’ unexpected move into Shakespeare at a stage in his career when his national sitcom treasure status might have been a curse as much as a blessing, there I am, “writer and broadcaster”, saying the following two sentences:

Kenneth Branagh definitely changed Richard Briers’ life, by offering these, er, fantastic Shakespearean parts … It’s easy to overlook the skills of an actor in a sitcom – wrong to, but it’s easy to do it, because they make it look easy, they’re just there to be silly, and funny, a lot of the time. That takes a massive amount of acting.

At 38.28, cut to the much better placed actor Adrian Scarborough, “co-star and friend”, with a far more personal insight. I’m not saying it wasn’t worth me travelling to Kensington and walking from the Tube to the hotel and back (they offered cabs, but I nearly always refuse cabs, as I’d seriously rather use public transport and walk), I’m saying it wasn’t worth the BBC employing me to go all that way in order to say those two sentences. Hey, I know, that’s the way documentaries are made: shoot way more than you need and edit into shape. The writer Andrew Marshall was on quite a few times, and offered sound, firsthand testimony, as he’d co-written If You See God, Tell Him. But If You See God, Tell Him was never mentioned, thus muddying his authority to all but comedy students. The edit takes no prisoners!

The Briers tribute is a really nice programme, and it’s still on iPlayer. You should watch it – it’s my last “talking head” appearance*. I’m glad my shirt and jacket looked smart.

*It probably is, anyway.

March 29, 2013

Writer’s blog: Week 14, Good Friday

I am, unusually for a working day, sitting in my kitchen. It is Good Friday. The British Library is closed, which is fair enough, as Good Friday is a bank holiday. I have too much to do to contemplate a day off, but I’m not angling for sympathy. To everyone who does get the day off, on full pay, I wish you a most excellent day (and likewise on Monday, which is Easter Monday, when I will be writing and filming Telly Addict at the Guardian just like it was a normal Monday). At least at home, I can drink my own coffee, and not pay through the nose for it.

Actually, of late, and to beat the system, I have been taking a flask out with me, charged with homemade coffee, which I then decant into a paper Peyton & Byrne cup in the Library canteen. There are polite notices up stating that only food and drink purchased on the premises can be consumed there, but I don’t believe this has ever been aggressively policed – at least, Library users are exactly the type to bring in their own sandwiches. Tupperware tubs are prominent, and, frankly, as long as most diners pay through the nose for Peyton & Byrne’s expensive cakes, I feel sure that capitalism ticks over. I don’t flaunt my not-bought-on-the-premises food and hot drink, and if I’m meeting someone, I always buy Peyton & Byrne’s coffee, and if the person I’m meeting is paying, I always have an overpriced cake too!

Talking of food and drink, I’m hooked back into Masterchef. I usually favour the Celebrity version for reasons shallow, but I reviewed the first episode of the new series of the Civilian one for the Guardian and haven’t been able to tear myself away. It’s formulaic, but some of the most comforting telly is, and Gregg and John move ever further into self-parody, but, again, it isn’t broke, so why fix it? (The irony here is that Masterchef has repeatedly tried to fix itself when unbroken, but aside from the impossible new “palate test”, this series is relatively untinkered.)

I was given the basic Great British Bake Off Learn To Bake book for my birthday earlier in the month, and I’m also watching Paul Hollywood’s Beard on BBC2 and finding him a stout and reliable tutor, so cooking is back on the agenda. I made this marbled chocolate banana bread at the weekend, which was supposed to be baked in individual tiny cake cases but I chose to do it in a single loaf tin. The result is not “marbling” in the elegant Baroque sense. But it tastes bloody nice. (Someone on Twitter asked if it was gluten-free. I’m afraid not. I have tried baking with rice flour, and various ancient grains, none of which truly did the job. The gluten is the protein that binds dough, and without it, you’re on the back foot. I avoid wheat for reasons of waistline expansion and maintenance of general energy levels, but I am not allergic to it, so when it comes to cake, it’s gluten or the highway.)

I’d read that you can freeze individual slices of cake, but never tried it before, so – after a call-out for tips and advice on Twitter – I wrapped them in tin foil and put them in a sealable bag. Yesterday I took one out, and by the time I was ready to eat it, it was as good as new. (Typically of Twitter, someone re-Tweeted my call for advice to food writer and TV cook Nigel Slater himself, who said, “It should work, but I’m no expert.” I was happy to report back to him that it did work, which makes me an expert.) When you’re baking to save money on shop-bought cake and biscuits, you have to learn how to ration. There’s a war on.

I’d read that you can freeze individual slices of cake, but never tried it before, so – after a call-out for tips and advice on Twitter – I wrapped them in tin foil and put them in a sealable bag. Yesterday I took one out, and by the time I was ready to eat it, it was as good as new. (Typically of Twitter, someone re-Tweeted my call for advice to food writer and TV cook Nigel Slater himself, who said, “It should work, but I’m no expert.” I was happy to report back to him that it did work, which makes me an expert.) When you’re baking to save money on shop-bought cake and biscuits, you have to learn how to ration. There’s a war on.

I should, by rights, have been in Glasgow last night, attending the studio recording of the final episode of “the Pappy’s sitcom” for BBC3, which as you know I script-edited. (I think it’s still called Secret Dude Society, but that may not be fixed.) However, it was being filmed in BBC studios, and the wrap party was also being held on BBC premises, so I didn’t travel up for what would have been, for me, a massive jolly, as the NUJ and Bectu were on strike from midday, over redundancies and “bullying”, and it would, for me, have been inappropriate. (It’s an entirely personal matter, and I make no judgement on anyone else.)

Anyway, I got a lot more work done yesterday and this morning as a result. As usual with these writer’s blogs, I cannot give too much away, but I have three comedies in development, currently, all at varying stages. Of the two pilots script that I’ve written, one, with C4, is written and delivered, and has hit a stalemate, but it’s not over yet. The other, for the BBC, was delivered last year and sent back for a complete overhaul – it’s the one that gave me writer’s block – and I have finished the second draft, which I wrote again from scratch, a blank screen. It’s almost ready to go to the broadcaster. The third comedy has only just been green-lit for development, and I’m carefully constructing a story breakdown with a production company before launching into the script. In comedy terms, I have three plates spinning. It’s all about keeping them from crashing to the floor.

I’m printing this picture in memory of Richard Griffiths, who died yesterday but whose passing was announced today. I feel certain it was taken at the first Empire Awards, which were in 1996, although I can find no record of the event to confirm it. I was definitely at the first Empire Awards, and the second, as a chaperone, and I had a terrific time at both, with various approachable film people, so who knows? I seem to recall a whole load of people connected with Withnail, so was there a special award for that film, or for Bruce Robinson? Don’t look on Wikipedia, as it’s not there. If anyone can help, I’d be grateful. I certainly jumped at the chance to have my meeting with Richard Griffiths captured on camera, and it’s a treasured Polaroid in my archive. Someone on Twitter pointed out that he can only have been 48 at the time, as he was merely 65 when he died. I am 48 today. Mortality is a terrible c—, if you’ll pardon the apposite language.

Two further things before I sign off:

Went to the cinema this afternoon – awarding myself half a Bank Holiday, as I’d completed my main writing task of the day by getting up at 6.30am – and after the trailer for A Late Quartet, starring Christopher Walken, I heard an older gentleman in the row behind claim loudly to his wife, “That’s Angelina Jolie’s dad!” (I resisted the urge to turn round and say to her, “It’s not. Don’t listen to him.”)

Now that we’ve seen the David Bowie exhibition, with all of his costumes on display, seeing footage of him on TV has taken a new turn. Catching the end of another repeat of BBC4′s Ziggy Stardust documentary (the one narrated by Jarvis), we found ourselves going, “Ooh, we’ve seen that cape!” and “Ooh, we’ve seen that fishnet vest!” It reminded me of my own dear Nan, who used to love to point out places she and Pap had been on holiday if they ever turned up on television. “Ooh, we’ve been there, Reg!” she would shout, if they showed, say, Minehead.

Happy Easter.

March 28, 2013

You’ve been shamed

Wow, this is a film with a takeaway message. Compliance is an American. Sundance-stamped indie from writer-director Craig Zobel, who’s pretty new to feature films (and totally new to me), and it’s surely the talking-point movie of the year. I’m going to do everything in my power not to give too much of the story away, as the experience of watching it unfold is devastating, and all the more so for not knowing how far it’s going to go.

Based on true events, conflating a number of hoax calls to fast-food restaurants in America and one particular case at a McDonald’s in Kentucky that went to trial in 2004 (I knew nothing about these appalling “pranks”), it takes place over a day in the working life of an Ohio chain fast-food restaurant, fictionalised as ChickWich. Shot in a real restaurant, with fake livery, Compliance is a realist study in human nature, in particular the worst recesses of it. We begin the day with a meeting of the outlet’s small staff, led by middle-aged manager Sandra (a totally convincing Ann Dowd, who’s played “the mother” in so many films and TV shows you’ll feel you know her already). She’s not a jobsworth in the worst sense, but she’s a franchise boss, and as such exists in deference to a managerial supply chain that goes right up to “Corporate”. She’s already on the back foot for a batch of bacon that’s been spoiled due to a freezer not being closed properly, and she’s not about to break any protocols.

A call comes in, once the working day is underway (it’s a Friday, it’s a busy day, adding to the stress of Sandra’s lot), apparently from a police officer, Daniels, who claims he has the regional manager on the other line and a customer with him who swears she had money stolen from her purse by one of the counter staff. He describes her as young, female, blonde … and Sandra does the rest, offering up Becky (Dreama Walker – you may recognise her as Zach’s girlfriend from seasons one and two of The Good Wife). We’ve seen some tension between the older, unmarried manager and the young, sexually promiscuous server (Sandra boasted of her fiancé “sexting” her after Becky revealed she has three boyfriends on the go, and Becky and a workmate were overheard mocking her).

From here, the situation builds to a grim, depressing crescendo. (When Sandra reports the story back to anyone, she mistakenly says that Officer Daniels knew Becky’s name; we know that Sandra gave him the name.) Daniels remains on the line while Sandra is instructed to apprehend Becky and take her into a back room where she is to be held until the police arrive. Daniels, authoritative and gruff, flatters Sandra and imbues her with a sense of civic responsibility, as well as subtly filling her with fear: for her own job, for punishment from head office, and for the consequences of standing in the way of a broader police inquiry into Becky. Sandra becomes the willing accomplice in the caller’s crime. It is no spoiler to reveal that “Officer Daniels” may not be an officer at all, and as the “prank” (more of a sadistic social experiment, you surmise) escalates, along with the blameless and cowed Becky’s humiliation, we the audience becomes suspicious and eventually learn things that – in a skilfully constructed script – various characters are not party to.

The acting is naturalistic and all the more haunting for it. I must admit, I had my face in my hands at the more uncomfortable parts. It’s been a while since I was so glued to the screen and affected by what I was seeing. You buy into the fact that this is really happening. Sandra remains calm, and compliant, while other staff react in different ways to what Daniels requires of them, as the phone is passed around, and a busy Friday at ChickWich grinds on. Zobel seems to be offering a critique of fast-food and corporate culture in America, constantly cutting from the back room to actuality of the burgers being chomped down out of their waxed-paper wrappers and shakes being vacuumed up from brightly-decorated pails.

It may seem a soft target, junk food, but Zobel isn’t criticising the individuals who choose to put something called a “cookies and cream shake” into their fat faces, but the system that has mechanised our eating habits into one big battery farm, with ample car parking out front. The music, by Heather McIntosh, is stealthily built from deep, melancholy strings, lending a tragic inevitability to the events that occur, and a poignancy to Zobel’s regular, beautifully-framed stills of discarded cups in puddles, ploughed snow, bent drinking straws.

You won’t see what’s coming. And you won’t guess the way the denouement to the crisis plays out, but it’s not a thriller in the conventional sense. You’ll wish it was a fantasy, but, apparently, it’s not. Even if it was a pure fiction, and had never happened, you’d start to wonder if it could.

I defy you to see Compliance and not still be thinking about the what-ifs days later. It’s hard to watch at some points, but not because, like other films that seek to shock, it involves seeing somebody having their skull caved in – the fashionable money-shot of our times. The violence herein is not gory, or heightened, it is subtle, insidious, terrifying in its banality, disturbing because of the brightly strip-lit surroundings of a fast-food joint’s unlovely office, and all the more horrific for largely happening away from our prying eyes. Bravo to Walker for an uninhibited performance – this was a brave role to take, especially when one audience member at the Sundance Q&A seemed to imply that Zobel had effectively exploited her and another accused him of (beware spoilers in this link) “making violence against women entertaining.” He hasn’t. This is not “entertaining” in the traditional sense.

Some will say that Becky is weak. But she is young, and she is in fear for her job, and if you accept that she believes Officer Daniels is legit and that his threats are real, you have to wonder what you might do in the same ugly, disorienting circumstances. Go and see this film. It’s difficult to get too specific without spoiling it. (Incidentally, I’d read Hannah McGill’s long and thoughtful review in Sight & Sound - not available online – and knew the whole plot, but as I say, my heart was in my mouth nonetheless.)

Big Mac, lies to go.

March 27, 2013

The androgyny exhibition

I wonder if he’ll ever know he’s in a best-selling show? Of course he will, you idiot. Just because he preferred not to fly over to London to see the sell-out retrospective exhibition of his capes, heels and notepads, David Bowie Is at the V&A, curated by Victoria Broackes and Geoffrey Marsh, has the full blessing of the Dame Himself. How could it not? Most of the stuff here – and boy, there’s a lot of stuff, over 300 items – comes from Bowie’s own archive. I want to go to there. Until that happens, this will very much suffice.

For an artist so iconic, long-lived, prolific and spread enthusiastically across so much mixed media, David Bowie keeps himself relatively to himself. Since his heart attack in 2004, now 66, he’s kept travel and work to a minimum – guest appearances in the studio and onstage with the likes of TV On The Radio, Arcade Fire, Scarlett Johansson – and I for one had resigned myself to a future with no major new release, glad to have seen him at Wembley on the Reality tour which he had to cut short in 2004 after the chest pains.

Where Are We Now? and The Next Day came as pleasant, fanfareless surprises, but despite what Waldemar Januszczak implied in his snooty review in the Sunday Times, the V&A exhibition was not designed as a promotional blitz for the new record, as the new record had no release date when the archive was raided, nor did it feel like an advert. There are a couple of references to the new LP, but if anything, David Bowie Is feels like a memorial, or at least a testimonial. A full-blooded, high-flying, celebratory one, but a testimonial nonetheless. It’s fantastic that he’s been back in the studio, but he’s given us so much already over five decades, it seems greedy to expect more.

Having booked a 4pm slot at the V&A, we were unaware that this would mean being turfed out of the exhibition at 5.30pm, and there’s enough here to keep a Bowiephile engrossed and wide-eyed for at least two hours, if not three, as you move chronologically and occasionally thematically through his life, constantly distracted by words, music, stills, moving pictures and annexes. Although the vast collection seems to have dummied up pretty much every significant outfit Bowie ever wore onstage or in a video – and, as Peter Contrad observed in The Observer, in an otherwise incoherent review, the costumes operate like the skins he has constantly shed – it’s the details, and the smaller items, that demand your closer attention: a pencil sketch on an opened-out packet of Gitanes; a photo of Little Richard in a gilt frame he must have borrowed off his parents in the 50s that Bowie still apparently treasures; a xeroxed manifesto for the Beckenham Arts Lab which the young idealist hoped to get off the ground in his Kent hometown in the early 60s (and with which Alexis Petredis seemed particularly taken in his uniquely useful, adroit and witty Guardian review); the typed letter to his manager drily announcing the name-change to “Bowie” … there’s even a tissue he’s used to dab his lipstick, although that may have crossed the line from appreciation into idolatry.

I liked the items that aren’t his, but are displayed to add context and texture to his journey, like the pile of science fiction paperbacks, the poster for a Hendrix gig he attended, and the oddly moving cover of the Times in 1969 bearing the photograph of earth taken from space. Again, Januszczak was predictably sniffy about Bowie’s own art, but I loved his painted portrait of Japanese writer and ritual suicidist Yukio Mishima, which he had above his bed in Berlin (there’s a whole room dedicated to what the exhibition calls his “black and white period” in West Germany), and his line drawings of his Mum and Dad were, again, rather moving. More practically, his sketches for sleeves and stage sets, as well as costumes, all of which were realised by professional illustrators, designers and costumiers, showed just how clear his vision has always been. And how hands-on he was, and remains.

The people shuffling round around us were of “a certain age”, and clearly transfixed, as well as taken back to important moments in their own life soundtracked by Bowie. You are forced to wear headphones and to listen to an electronically-triggered soundtrack, but I took mine off (don’t try and tell me what to do, The Man!), as there’s enough sensory information without another layer. I liked that some people were possibly unwittingly singing along to the tunes in their ears.

There’s not much I can say about Bowie that hasn’t already been said a hundred thousand times. If you can take or leave him, or only know the hits, you may find David Bowie Is a bit much. If, however, you consider him the greatest and most diverse musical solo artist of the last century (and some of this one), this exhibition will thrill you constantly, in miniature, and in widescreen. The final room – a vast hall, really – has floor to ceiling film of Bowie live, projected onto a sort of thin netting that allows further dummies in costume to be illuminated through it. It’s a rock concert finale to a symphony of memory, allusion, art, ephemera, light, shade, tone and poetry that also tells you whose shirts he wears. Because of the venue, most publications have sent their art critics to review the show, and many have failed to take its pulse. It’s art, but not as they know it.

Me? I was excited enough to actually see an original 1975 pack of Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt’s famous Oblique Strategies cards, in a glass case, which influenced Bowie during his Burroughs cut-up stage.

This is what some of them suggest, in order to eliminate creative blockage:

Use an old idea.

Try faking it!

Work at a different speed.

Do the washing up.

Here’s the lyric from Blackout, which is displayed in the exhibition. You should try and see it, really.

Oh, you can buy a publicity shot for the Diamond Dogs album taken in London, 1974 by Terry O’Neill, from a limited edition of 50, for £4,800 from the gift shop, or walk away with a Bowie plectrum for 75p. There’s plenty of other gifts in between, too, many of them V&A exclusives (and you can order online, but I suspect you’d rather handle and inspect them first). I hope they take this show on the road so that you don’t have to come to London to see it between now and August 11 (and most of the tickets have been sold already; the fastest selling show in Victoria and Albert’s history).

This is a show for all – that is, all the tall-short-fat-skinny people with an ear for David Bowie, not just Metropolitan dandies and tourists. Again, Januszczak is plain wrong when he says that the V&A looks ridiculous trying to be “down with the kids”. It’s not really aimed at the kids, although the kids might learn something (that Lady Gaga didn’t think of this, for a start), and I was impressed to see a very young school party queuing up when we popped back for the shop this afternoon. What a cool school trip.

Are there sections? Consider transitions.

Andrew Collins's Blog

- Andrew Collins's profile

- 8 followers